PRINTER FRIENDLY PDF

EPUB

AUDIOBOOK

The origins of the U.S. Marine Corps’ initial involvement in the Vietnam War is a little-known part of the conflict’s historiography.2 In the nearly 50 years since the first combat unit arrived in the Republic of Vietnam (RVN), or South Vietnam, military historians have yet to explore why it was U.S. Marines landing, as opposed to the Army, and why of all places in the RVN they landed at Da Nang on 8 March 1965. Underscoring this apparent oversight in the collective history of the conflict is the broad acceptance of the idea of a hastily planned landing and subsequent counterinsurgency campaign championed by the Marines. However, a thorough analysis of the volumes of documents pertaining to the planning for intervention in the RVN proves this to be a flawed characterization of the tasks assigned to the Marines in contingency plans drafted nearly a decade earlier.

What was the Marines’ role in Da Nang and in larger contingency plans? The absence of a comprehensive study to answer these questions adds to an already inaccurate and misleading historiographical account of the planning origins and how Marines came to be so deeply involved. The purpose of this article is to address these historiographical oversights by explaining the Marines’ conceptual roles in contingency plans developed between 1951 and 1965. This affords the opportunity to correct a grave misinterpretation perpetuated by historians lacking a clear understanding of the war and military planning for intervention before 1965.

Nearly every study of America’s military intervention in Vietnam begins with the description of this “hasty” landing in the wake of an increase in in- surgent activity around Da Nang and elsewhere in the country. The controversial Pentagon Papers describes it as a watershed event in the history of the war presenting a “major decision made without much fanfare—and without much planning. Whereas the decision to begin bombing North Vietnam [the Democratic Republic of Vietnam (DRV)] was the product of a year’s discussion, debate, and a lot of paper, and whereas the consideration of pacification policies reached talmudic [sic] proportions over the years, this decision created less than a ripple.”3 This rather common depiction of the landing could not be further from the truth.

Even before the 8 March landing, planners considered the Marines essential to an array of contingencies for defending the south. Senior U.S. military officials would see to it that civilian officials followed these plans, though some were more difficult to convince than others. On the eve of the landing, Assistant Secretary of Defense John T. McNaughton proposed to Secretary of Defense Robert S. McNamara and the Joint Chiefs of Staff that the Army’s 173d Airborne Brigade should take on the security mission at the airfield and other key facilities and installations instead of the 9th Marine Expeditionary Brigade (MEB). His sole reasoning was that any American military action had to be inconspicuous so as not to attract attention for fear of further destabilizing the situation there. In McNaughton’s view, the image of Marines equipped with tanks and artillery pieces storming ashore from amphibious ships could do further damage. Conversely, he judged that Army airborne forces signaled a “limited, temporary nature of the U.S. troop deployment” since they carry less equipment and “look less formidable” than a Marine amphibious force.4

McNaughton’s proposal received strong opposition from the former chairman of the Joint Chiefs and U.S. ambassador to the RVN, Maxwell D. Taylor, as well as from General William Westmoreland and Admiral Ulysses S. Grant Sharp, the commander of all U.S. forces in the Pacific, including South Vietnam. Admiral Sharp justified his rejection of McNaughton’s last-minute proposal by referencing the seven active contingency plans governing American military intervention in Indochina that explicitly assigned Marines to Da Nang. Sharp insisted that, because “the situation in Southeast Asia has now reached a point where the soundness of our contingency planning may be about to be tested,” there was neither the time nor the need to make changes to previously approved plans even if the political and military objectives were slightly different.5 In addition, he argued that, from a planning and preparation perspective,

since the origination of OPLAN 32 in 1959, the Marines have been scheduled for de- ployment to Da Nang . . . contingency plans and a myriad of supporting plans at lower echelons reflect this same deployment. As a result, there has been extensive planning, reconnaissance, and logistics preparation over the years. . . . I recommend that the MEB be landed at Da Nang as previously planned.6

Sharp deemed McNaughton’s request to replace the 9th MEB with the 173d Airborne Brigade “imprudent,” particularly since military planners determined this region of the country required a lighter, mobile, and more self-sustaining force.7 Like Sharp, Westmoreland also argued in favor of deploying Marines to Da Nang:

Almost all contingency plans developed through the years for Southeast Asia involved marines in the northern provinces of South Vietnam, and if one of the contingencies should come about, I wanted to go with the plan. In view of a lack of logistical installations or support troops, a marine force trained and equipped to supply itself over the beach was preferable to an air-borne force lacking logistical capabilities.8

President Lyndon B. Johnson and McNamara agreed, ending McNaughton’s proposal. The 9th MEB proceeded to Da Nang as planners intended. In the early years of potential direct U.S. military involvement, from 1959 to 1962, amphibious ships of the U.S. Seventh Fleet carrying the 9th MEB responded repeatedly to Communist advances in Indochina. On each occasion, the Seventh Fleet acted according to contingency plans developed years earlier to counter aggression in the region. Determined to prevent America’s regional allies from falling to Communism, President John F. Kennedy kept close watch over Indochina and pledged to intervene, militarily, if necessary. During the Laos crisis of 1962, however, President Kennedy told his senior White House aide, Walt Whitman Rostow, that if he committed U.S. military forces to prevent Indochina from becoming a collection of Chinese satellite states he would do so in Vietnam, not in Laos. According to Rostow, Kennedy’s rationale that southern Vietnam was the more logical choice was, among other reasons, because of its “direct access to the sea” and geography that “permitted American air and naval power to be more easily brought to bear.”9 That same year, the Geneva Accords of 1962 (or Declaration of the Neutrality of Laos) prohibited all parties involved in the conflict from basing military forces and equipment there and shifted the U.S. military’s attention back to the RVN, making the South China Sea an important part of planning. Less than three years later, the 9th MEB waded ashore at Da Nang.

Southeast Asia and the Western Pacific theater. Marine Corps History Division

Indochina and the Ho Chi Minh trail network. Marine Corps History Division

Long before Kennedy’s edict, discussions among U.S. military planners on the prospects of military intervention in Indochina included some of the same rationalizations on sea power, Marines, and, among other key locations, Da Nang. Whether blunting a North Korean-style invasion of Indochina and, later, the RVN by Chinese and DRV forces, or curtailing an insurgency threatening to overtake all of Southeast Asia, Marines were sure to play a role based in part on the reasons Kennedy highlighted and the Ma- rine Corps’ mission, functions, and doctrine of the time.10 By the time the conflict reached the point of full American military intervention under President Johnson, contingency plans provided for a significant Marine contribution to defend the country’s five northern provinces.

The relationship between the Marines and the conflict in South Vietnam dates as far back as the First Indochina War between the Viet Minh independence movement and the combined French colonial forces, including those from Laos, Cambodia, and Vietnam. The Viet Minh offensive of 1954, featuring Chinese-made tanks and artillery, ended with several captured or abandoned French outposts north of Hanoi and a high command pulling its combat units closer to the capital to prevent its capture. After nearly eight years of fighting, France saw the war as unwinnable unless the United States and Britain provided direct military assistance. One such French request included “twenty thousand Marines” to seize the seaport at Haiphong before opening an escape route between Hanoi and the port for safe passage of French forces to Da Nang.11 With the exception of the size of the Marine contingent, the request mirrored a study presented to the French three years prior in 1951.12 President Dwight D. Eisenhower concluded in both instances that, without concurrences from Congress or the support of U.S. allies, intervention was not in America’s best interest.13

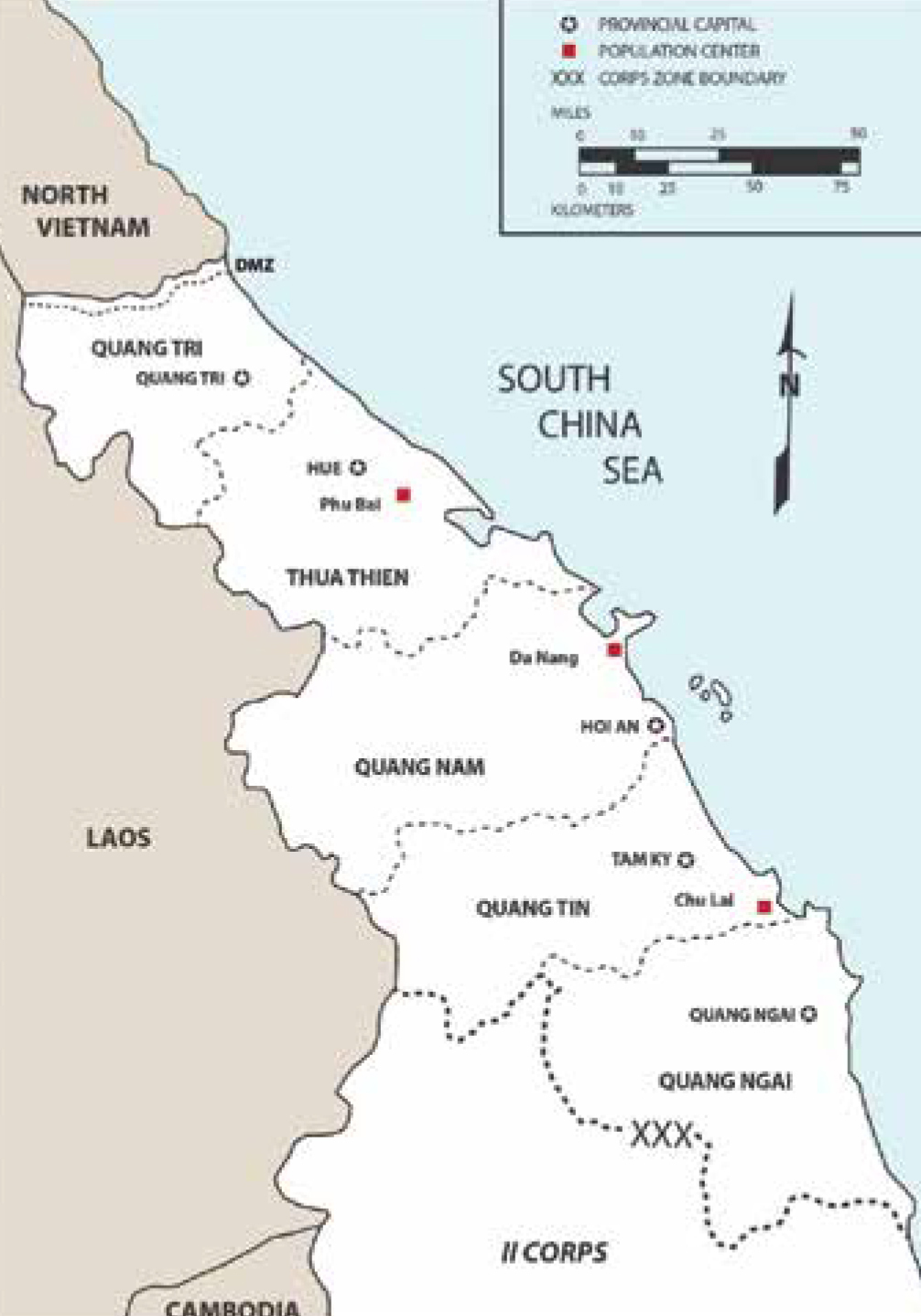

I Corps Tactical Zone and northern provinces. Marine Corps History Division

The 1954 Geneva Accords officially ended the war and partitioned Vietnam into two countries. The war’s end also marked the beginning of America’s deliberate planning to defend the RVN from an invasion by the DRV and China. Early plans for the commitment of U.S. forces entailed substantial Marine involvement. Like plans for contingencies elsewhere in the world, the Marine Corps tied its doctrine, operating concepts, equipment acquisitions, officer education, and unit training to what it anticipated to be its role in the south. By 1962, the Marines were focusing on a conventional scenario, even though military planners on the Joint Chiefs’ staff shifted their attention to a Communist-inspired insurgency and U.S. support for a national pacification effort. Although combating guerrilla forces and pacifying the population consumed a great deal of the Marine Corps’ attention, the Service envisioned that it would still deploy combat units to repel a ground invasion and for sustained conventional military operations. Civilian and military officials debated committing U.S. combat forces to end the stalemate and reunify the two Vietnams. Foremost on the minds of military planners was the potential for a North Korean-style invasion to seize the south’s major cities and seaports and the capital in Saigon. Agreements coming out of Geneva to hold national elections likely prevented an invasion, though few in President Eisenhower’s cabinet expected the north to remain idle. Anticipating Communist aggression, Eisenhower’s national security team began work in 1955 on a security policy vis-à-vis an American military response. The result was National Security Council Memorandum 5602/1 and a U.S. Department of Defense initiative to develop contingency plans for direct military involvement.14 A planning cell under the supervision of the Joint Chiefs explored several scenarios requiring a direct U.S. military response. The cell formalized its findings in June 1956 with Limited War Plan– Indochina.15 Aimed at repulsing “overt aggression” by China and the DRV, the plan outlined the American military response in two distinct phases: a massive allied air bombardment of invading formations, including the potential use of nuclear weapons, and the introduction of U.S. and allied ground forces to seize select military objectives in the south and the north.16 Critical to the success of the opening phase was a South Vietnamese “delaying action from the 17th parallel to the hill mass around Tourane” to buy time for U.S. forces to arrive and form the counterattack.17 Three U.S. Army regimental combat teams and two Marine regimental landing teams served as the vanguard of an American-led campaign estimated to take between 9 and 12 months to complete. The mission was to seize and defend the seaports and airbases at Da Nang, Cam Ranh Bay, and Saigon, where additional forces and supplies were to arrive before counter-attacking Viet Minh forces (and potentially Chinese) south of the 17th parallel.18 Their objective was to destroy or push all Communist forces north of the 17th parallel and reestablish the demarcation line.

That same year, the Army conducted its own study of the situation in Indochina. Campaign Plan–North Vietnam, like Limited War Plan–Indochina, highlighted many of the same points and offered a few changes. In its plan, an Army division would lead the counterattack north of Da Nang in conjunction with amphibious landings by Marines in the DRV to cut off Viet Minh escape routes and to seize key military bases on the coast.19 Afterward, the Marines would join the Army for a follow-on attack against the port at Haiphong before moving west along the Red River valley and seizing Hanoi.20 The end state was a reunified Vietnam under control of the RVN’s government, thereby ending the conflict entirely and halting China’s advances in Indochina and Southeast Asia. Planners estimated the counteroffensive alone to take three months to complete with another eight months to clear and secure Viet Minh base areas in the mountains north of Hanoi.21

The headquarters for all American military forces in the Pacific produced its own blueprint for conflict in Indochina, which was identical to the Army’s Campaign Plan–North Vietnam, but with one major difference whereby amphibious landings north of the 17th parallel were contingent upon the intensity of the resistance at Da Nang and the high probability of success. Confident that a framework for American military action was in place, the Joint Chiefs delegated sole detailed planning and coordination responsibilities to the Pacific Command’s multi-Service planning cell.22

With ownership of detailed planning and coordination, the senior joint U.S. military command in the Pacific theater began work on Operations Plan (OPLAN) 46-56.23 Defeating a ground invasion by a combined Chinese-DRV force or by North Vietnamese forces acting alone was still the primary concern as was the timely arrival of U.S. forces and RVN hold- ing actions between Da Nang and the demilitarized zone. Two major changes surfaced as a result of the Pacific Command’s more detailed planning effort. The first was that OPLAN 46-56, unlike its predecessors, restricted the use of nuclear weapons. The second was the realization of a more complex Communist ground invasion scheme.

Based on their study of the terrain and geography, planners did not foresee the Communists limiting their invasion to one axis of advance, particularly if there was the potential for direct U.S. ground and air involvement. Instead, planners believed the Communists would rely on as many as three attack routes. The first and most direct route took invasion forces south across the demilitarized zone along National Highway 1 (the only north-south road in Indochina) to capture the major cities of Hue, Da Nang, Qui Nhon, Tuy Hoa, Nha Trang, and Phan Thiet.24 Communist forces also might attack via the Lao panhandle along the Ho Chi Minh Trail network. With this particular route, invading forces could move south before turning east into South Vietnam at the central highlands and capturing the border towns of Kon Tum, Pleiku, and Ban Me Thuot straddling National Highway 14. Planners assessed that the Communists’ goal was to cut the country in half.25 The third route planners considered began in northern Laos and traversed the full length of the Ho Chi Minh Trail through the central and southern part of the country and into eastern Cambodia along the Mekong River, putting invading forces within easy striking distance of Saigon.26 Most expected enemy forces to use a combination of the three routes to deceive and overwhelm American and RVN command-and-control and defenses.

The opening phase of any combined American-RVN military response to the most simple or complex invasion was to keep the Communists north of Da Nang and to use ground forces and supplies for both land- and sea-based counteroffensives. Several coastal points were vitally important since, according to Vietnam War historian Dr. Alexander S. Cochran Jr., planners expected U.S. forces would deploy to “Vietnam by sea and a few by air” and be “resupplied through coastal ports.”27 As detailed planning continued, the Joint Chiefs approved a list of ground and aviation commands for the military response. Planners ear-marked the 3d Marine Division and 1st Marine Aircraft Wing, both in Japan, for operations to seize the Hai Van Pass just north of Da Nang where National Highway 1 traversed the Truong Son mountain range and emptied into the enclave.28 Optimistic that the Marines could slow the pace of invading forces with a hasty defensive line and buy time for additional American and allied forces to counter the offensive, planners wanted an additional Marine contingent to remain at sea for use in amphibious landings at various points on the southern and northern Vietnamese coasts.29

When planners surmised that the Communists might consider alternate and multiple invasion routes, they realized Saigon might not be the only seat of government at risk. The Thai capital at Bangkok and the Laotian capital of Vientiane also were at risk of becoming Communist targets.30 Their theory prompted senior military officials to consider drafting a more expansive plan and to include Thailand and Laos as part of their overall Indochina defense strategy. Events internal to South Vietnam and the greater Indochina region compelled Pacific Command to more critically assess North Vietnam’s intentions, as well as those of China, and the means by which the Communists might overcome the advantages the U.S. military held in technology and firepower.

The rationale behind American plans centered on the type of conflict into which the Joint Chiefs believed U.S. forces were entering. In 1959, the Communists started to view reunification in terms of years and not as a result of a single overt military invasion. Graham Cosmas wrote in MACV: The Joint Command in the Years of Escalation that the DRV recognized that a conventional invasion, with or without China, would not achieve reunification. Instead, it would have to combine “large-scale military campaigns with widespread popular uprisings” to realize this goal.31 Getting the support of the people would take time. Cognizant of America’s pledge to protect the south from invasion and of its advantages in military technology and firepower, the north decided instead to present numerous conventional and unconventional challenges to RVN officials and U.S. officials and their allies to resolve. Beginning first with the rise of the Communist Pathet Lao insurgency in Laos in 1957, the north put pressure on the south by creating instability on its borders. Then, in 1960, the DRV set conditions for war in the RVN when it revised its 1946 constitution. In it, the ruling Lao Dong (Vietnamese Workers) Party drafted a proclamation directing its forces to prepare to defend the north and liberate the south. The same decree gave formal rise to the southern branch of the Lao Dong, known formally as the People’s Revolutionary Party (PRP), with the mission of undermining the RVN government and stirring resentment among the southern people toward their government and military.32

Recognizing the United States was likely to suspect DRV involvement in violating the Geneva Accords by undermining the RVN government, Communist officials attempted to conceal their actions by encouraging nationalists and other non-Communist organizations to participate in reunification efforts. These groups formed the National Liberation Front (NLF) in December 1960, the majority of which was Communist.33 The growth of the movement prompted the Lao Dong to form the Central Office for South Vietnam (COSVN) to coordinate all political and military activities south of the demilitarized zone. Under COSVN’s direction, the NLF carried out day-to-day guerrilla actions in the south. Similar to Mao’s people’s war in China, the NLF’s strategy consisted of military operations at the regional, provincial/district, and village levels to wage a guerrilla campaign to gain the support of the population and control the countryside before “consolidating and expanding the base areas” and to strengthen “the people’s forces in all respects. . . in order to advance to building a large, strong armed force which can, along with all the people, defeat the enemy troops and win ultimate victory.”34 The result was a massive expansion of the NLF in slightly more than two years. According to Cosmas’s estimates, the NLF grew “from about 4,000 full-time fighters in early 1960 to over 20,000,” with as many as “20 battalions, 80 separate companies, and perhaps 100 platoons of widely varying personnel strength,” the bulk of which COSVN deployed in and around Saigon.35 The NLF formed battalion-size units specifically to conduct conventional operations in the central highlands and northern provinces.36

The NLF adhered to the same tactics the Viet Minh used against the French. Fighting units consist- ed of three elements: main forces, provincial or district units, and local guerrilla forces. The uniformed and well-armed, organized, and equipped main forces consisted of battalion- and regimental-size units who took their orders directly from the COSVN and subordinate regional headquarters. These main forces were for major operations and attacks against large French (and later American) formations only. The provincial and district units were a composite of guerrilla and main force units operating at the company and battalion levels. Although equipped and organized similar to the main forces, these units were not nearly as capable. Their primary role was small-scale raids and other offensive actions.

The least capable armed component outside the “estimated 20,000 combat troops counted by the allies” was the village-level local guerrillas.37 Formed into platoons or smaller units, guerrillas received their orders from district and village officials. Ill-equipped and untrained, guerrillas lived among the people and harassed South Vietnamese, French, and American units as they moved through or near villages. Their greatest attribute was conducting reconnaissance for the main forces as well as providing logistics support and partially trained replacements.38 All levels of the Communist armed division relied upon the villages for food, clothing, recruits, labor, and medical supplies. Most of their weapons and ammunition, however, came from the DRV or were fabrications. As early as 1962, the NLF built base areas in the rural areas and outside the RVN government’s sphere of control and influence. The Marines’ long-term plan in the northern provinces was to retake these areas, along with the enclaves, one at a time.

Successful incursions into Laos and inconspicuous interference in the south’s deteriorating domestic affairs shifted the momentum in favor of the Communists. Instability in the south increased as the Communists’ political cadres, educated and trained in the north just after the partitioning of Vietnam, returned to their hamlets and villages to play on the fear and anger of disenfranchised farmers and to challenge the legitimacy of the RVN government.39 Promising sweeping land reforms in exchange for their loyal support—and punishment for their betrayal—the initial wave of political cadres made immediate gains among the people living in the rural areas and away from the large and more prosperous cities. At the same time, Chinese and North Vietnamese Army (NVA) advisors and equipment outfitted district and main force units. To ensure an endless flow of weapons and ammunition, the NVA carved out new infiltration routes leading to and from South Vietnam and expanded existing pathways.

The Pacific Command’s responsibility to plan for military action brought about a less centralized and unconventional way of thinking as well as a broader perspective emphasizing greater awareness of the regional situation and not one focused solely on the RVN. The principal issue prompting planners to revisit their earlier planning considerations was the potential for invading forces to use new and multiple routes. Since two of the three anticipated routes crossed through neighboring Laos and Cambodia, the security and stability of those countries were important to the South Vietnamese government. Border control, therefore, was important. Due to the RVN’s geographic disposition and the presence of Communist forces in Laos and Cambodia, planners saw value in developing more inclusive U.S. action.

The conditions in Laos, more so than in Cambodia and the RVN, convinced planners that a new and comprehensive series of plans reflecting simultaneous actions in different parts of Indochina was necessary. Known as Operations Plan 32: Defense of Indochina (OPLAN 32), the successor to OPLAN 46-56 was American’s first real attempt to bring together military forces from throughout Southeast Asia to contain Communism and, specifically, to prevent the fall of Indochina entirely.40 The series of plans consisted of actions in the RVN to counter both a conventional ground invasion and an insurgency, as well as actions to defeat DRV-backed insurgencies threatening Laos and Thailand. Actions specific to South Vietnam fell under OPLAN 32-59.

OPLAN 32 consisted of four distinct phases to counter or combat Communist aggression: Phase I- Alert; Phase II-Counterinsurgency; Phase III-Direct North Vietnamese attack; and Phase IV-Direct Chinese attack. In Phase I, U.S. forces were to assemble and to make preparations to respond to deployment orders regarding either or both scenarios. Phase II “extended from the time the United States decided to take military action against a Communist insurgency until the friendly government regained control or the conflict escalated into a full-scale local war.”41 Although Phase III put American forces in action against the DRV specifically, Phase IV dealt with actions against China in the event of its direct involvement in any ground invasion.42 Concerning the Marines, Phase II entailed a “scaled-down version of the Phase III deployment, with a portion of the Marine force going to Da Nang and two Army brigades to the Saigon area.”43 In Phases III and IV, a full Marine Expeditionary Force (MEF) would deploy to Da Nang, with an Army division deploying to Qui Nhon and the central highlands and an Army airborne brigade to Saigon.44 These forces were to assist RVN forces in blocking the Communist attack down the coast and against Saigon. Their principal mission was to defend the developed coastal areas, thereby freeing RVN units to take the offensive.

OPLAN 32 architects, unlike those of previous plans, conceded to the idea that an insurgency was likely and that by inciting instability in a neighboring country the Communists were attempting to divert U.S. attention and, if possible, military resources away from South Vietnam. The final draft of OPLAN 32 left open the possibility for American ground forces to “engage in unspecified counter-guerrilla activities” after turning back the anticipated ground invasion.45 In the event of calling on U.S. forces to counter an insurgency, planners decided the same enclaves used as part of the defensive and counterattack against the ground invasion would still serve as bases of operations.

The presence of Communist forces in Laos that had remained in place by the Geneva Accords left the Royal Lao Government (an ally to the United States) and neighboring Thailand vulnerable to influence and attack. As the situation in Laos intensified, planners focused on developing a Lao-specific branch plan. With this in mind, the Pacific Command added OPLAN 32-59 (L) in June 1959 to prepare for unilateral U.S. military action to restore “stability and friendly control of Laos in the event it was threatened by Communist insurgency.”46 A theme common to all of the operation plans for Indochina was the rapid deployment of conventional military forces. OPLAN 32 (L) was no different, but this time America’s quick response was for securing airfields and the Mekong River crossing points connecting Seno and Vientiane, Laos, to Thailand. Those actions included a sizeable Marine air-ground commitment.

President Kennedy’s election in 1960 brought with it several dramatic changes to U.S. military policy toward Indochina. It also impacted joint military planning and the Marine Corps’ potential role in the war there. The first change came with President Kennedy’s pledge to rebuild the U.S. Armed Services. Allan R. Millett explained in Semper Fidelis: The History of the United States Marine Corps that under Kennedy, the Marine Corps “began a five-year surge in readiness that brought it to its highest level of peacetime effectiveness by the eve of the Vietnam War.”47 Kennedy’s rationale for restoring traditional military capabilities was to ensure that the United States possessed both feasible and credible counters to Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev’s encroachment into Western Europe. The most significant change, however, would be Kennedy’s pledge to counter Khrushchev’s declaration to support unconditionally wars of national liberation around the world. Indigenous rebellions and popular insurgencies in Cuba, the Dominican Republic, and in other parts of Central America, Africa, and Indo- china were but a few examples.48

Countering Soviet support for wars of national liberation was one of Kennedy’s first directives to the Joint Chiefs. He tasked the Service chiefs with developing and including special warfare and counterinsurgency doctrine in Service training and professional military education. At the same time, Kennedy increased defense spending to prepare the Services to fight conventional wars. The Services responded to Kennedy’s Flexible Response policy by overhauling Service-specific roles and responsibilities to meet his mandate for providing courses of action other than the nuclear option championed by President Eisenhower in his New Look initiative beginning in 1953.49 Despite Kennedy’s interest in special/counterinsurgency warfare, he and Secretary McNamara wanted a Marine Corps “capable of sustained combat” against a peer competitor and on land.50 The Marine Corps was already moving in that direction. A decade earlier, the 19th Commandant, General Clifton B. Cates, stressed that the Service build a “solid foundation of competence in conventional land warfare,” adding that “if the occasion demands it” Marine forces will be “capable of moving in and fighting side by side with Army divisions.”51

In 1951, Marine Corps doctrine writers began emphasizing a quick-strike capability as opposed to the Army’s heavier and more deliberate land warfighting doctrine focusing on both offensive and defensive thinking. Service doctrine under General Cates centered on creating a force capable of seizing and holding objectives, such as seaports and airfields, to support the arrival of a larger Marine and Army force. Under Flexible Response, however, the Marines would not return immediately to amphibious ships waiting offshore. Instead, they would continue limited offensive and defensive operations to support the larger ground campaign as well as keeping lines of communication and resupply routes open for Army forces fighting farther inland. Rather than operating from ships, base areas similar to the beachheads of the Second World War would provide the Marines with intermediate logistics support, artillery emplacements, and shore-based command-and-control nodes. With additional capabilities, the Marine force could extend or duplicate their beachheads farther inland, if necessary.52

While the Marine Corps improved its warfighting capacity, Pacific Command planners considered with great certainty that a DRV-sponsored insurgency was now the most likely threat to the RVN and that the long-anticipated conventional invasion was less likely. Counterinsurgency warfare and military support to political, social, and economic concepts received greater attention. Up to this point, U.S. advisors concentrated on preparing RVN forces to repel a conventional ground invasion. After conventionally organized and equipped NLF battalions routed Army, Republic of Vietnam (ARVN), units in 1961, President Kennedy sent his chairman of the Joint Chiefs, General Maxwell Taylor, to South Vietnam to assess the situation and recommend a way forward. Taylor’s trip led to the establishment of a new command structure, the U.S. Military Assistance Command, Vietnam (USMACV), and the quadrupling of American personnel supporting its mission. He brought back a profound understanding of the conflict and a cautious tone concerning America’s direct military involvement in the fighting.53

Unlike Taylor, the Joint Chiefs resisted widening America’s advisory-and-assistance role. Although Commandant General David M. Shoup had a close professional relationship with Kennedy, it did not prevent him from being one of the more vocal opponents of America’s and the Marine Corps’ potential involvement in the conflict, particularly in a counter-insurgency role.54 Shoup did just enough to convince Kennedy that the Marine Corps followed his directive to incorporate counterinsurgency warfare into its doctrine and training. Historian Howard Jablon observed in an article on General Shoup that, despite Shoup’s many accomplishments, he failed to convince Kennedy that “counterinsurgency warfare was unrealistic” and that the Marines were not suited for nation-building.55 Given the option, Shoup wanted to keep from involving Marines in these types of conflicts.

The Pacific Command offered few deviations to their theories on both an overt and covert Communist takeover of the RVN. With President Kennedy’s deep interest and concern that wars of the future would be both conventional and involve the people and guerrilla elements (as witnessed in Cuba, French Indochina and Algeria, and China), planners wanted to produce options in the event U.S. forces had to confront either or both. To be able to fight an insurgency, while at the same time having the resources in place to counter a conventional invasion, planners identified locations along the Mekong River stretching from Thailand across Laos and the RVN to the Tonkin Gulf and other positions south near the Cambodia-RVN border.56 This main line of resistance, supported by the other allied nations making up the Southeast Asia Treaty Organization (SEATO) included armor and infantry forces as part of an anti-infiltration scheme designed to halt the flood of Communist advisors and equipment entering the country from North Vietnam.57 These were the same locations planners considered to be potential border crossing points for the conventional ground attack, if it materialized.

In either instance, Marines would play a much larger and preemptive role than Pacific Command planners had conceived and studied with the idea of deploying U.S. ground forces in advance of an invasion and before the insurgency grew out of control. One plan called for a MEB to establish “secure base areas” at Da Nang and other coastal locations.58 They also envisioned that a separate and larger MEF would either pass through Da Nang to carry out operations against the insurgency or stay “anchored on the coast to preserve additional amphibious option.”59 Meanwhile, a second MEF (minus the brigade at Da Nang) would remain at sea “to quarantine South Vietnam to degree necessary to significantly reduce Viet Cong sea infiltration.”60 They continued stressing the importance of amphibious operations against the DRV to draw Communist forces away from the demilitarized zone and Laos-Cambodia-RVN triborder region. Roughly 205,000 U.S. combat and support personnel (six divisions) were to support this plan, including nearly 85,000 Marines.61

To prepare the Marine Corps for the range of potential tasks, General Shoup directed the Landing Force Development Center at Quantico to develop a classified advanced base staff exercise centered on the volatile security situation in and around Da Nang. The goal was to orient officers to the conflict and enhance their understanding of the Marine Corps’ prospective area of operations. He also wanted to glean ideas and concepts from their planning to improve Service-level thinking on the conflict and how the military command in South Vietnam could best deploy and employ Marine forces. All Marine officers assigned as students at both the Amphibious Warfare School and Command and Staff College in Quantico between 1963 and 1965 participated in a planning exercise titled Operation Cormorant. The scenario involved the deployment of a reinforced MEF at Da Nang in an effort to stabilize and defend the enclave in the face of a growing insurgency and looming Communist ground invasion.62

Given the security situation, a common trend Shoup noted was that students saw pacification of the populated areas as a critical task and that it would require a significant number of Marines to secure and hold pacified rear areas. No less important was their regard for conventional military operations. When the 9th MEB landed at Da Nang in 1965, a large number of the Marine officers assigned to the command were uniquely familiar with the security situation in Da Nang and the tasks assigned to them as a result of their Operation Cormorant planning experiences.63 Regardless, Shoup was no more willing to get Marines involved in a purely counterinsurgency role. Instead, he stressed the Marine Corps’ neutrality: “We do not claim to be experts in the entire scope of actions required in counterinsurgency operations. We do stand ready to carry out the military portions of such operations and to contribute to such other aspects of the counterinsurgency effort as may be appropriate.”64

In the aftermath of widespread civilian unrest brought on by the insurgency, religious indifferences, repeated changes in the RVN government and military leadership, and ongoing pleas for land and social reforms, U.S. planners replaced OPLAN 32-59 with OPLAN 32-64 in early 1964.65 The central theme of planning shifted from defending the south from an outside threat to stabilizing the country in spite of several internal threats. At the same time, to increase pressure on the north to cease its support for the NLF, the Joint Chiefs recommended an air campaign featuring a highly scrutinized list of 94 industrial and military targets to cripple the country’s economy and ability to provide the necessary warfighting materials and resources to sustain the war.66 Some of the perspectives from previous plans gained new life. In OPLAN 32-64, planners reintroduced three invasion routes that were identified in earlier plans, only this time they looked to these locations as crossing points for insurgents and NVA forces slipping into the south from the north, Laos, and Cambodia.67 The plan established border control points to monitor these areas specifically. OPLAN 32-64 called attention to several major sea and coastal infiltration points as well.

Pressure to involve American ground forces accelerated in 1964 after a series of ARVN battlefield setbacks convinced U.S. political and military officials that the South Vietnamese government could not win the war. A once-cautious General Westmoreland, who assumed command of USMACV in June, con- templated implementing the defensive line outlined in OPLAN 32-59. In his proposal to the Joint Chiefs to consider the measure, he suggested deploying mobile light infantry units near the demilitarized zone to both delay invading forces and clear and hold guerrilla base areas and surrounding Saigon with an elaborate system of defenses formed around air cavalry units and mechanized and armor divisions extending north and west of the capital city.68 In keeping with the plan, Ma- rine forces would operate in the northern provinces, where they were to establish beachheads adjacent to the largest enclaves and where any number of beaches could be used for landing Marines and resupplies.69 If the Communist ground invasion never materialized, the role of U.S. ground forces was to advise and build the RVN’s military’s fighting capacity in conjunction with support for national pacification programs to reinforce the population’s confidence in the government. OPLAN 32-64 represented more than just a new plan; it reflected the way the United States viewed the evolving situation in South Vietnam.

The Johnson administration considered the NLF closer to overthrowing the RVN government than at any time in the past decade, reigniting both private and public debates over America’s direct intervention. With each passing day, Communist political cadres and guerrilla forces seemingly increased in numbers, popularity, and overall strength. Hanoi viewed the NLF’s gains as an opportunity to increase pressure in the demilitarized region, infiltrating more than 12,000 soldiers in 1964 as compared to the 7,900 in 1963.70 In the northern provinces, the Marine Corps watched closely as the contact between the ARVN and the main forces and NVA increased in frequency and lethality. In areas where NVA units were purportedly infiltrating, Chinese and Soviet weapons and ammunition surfaced in large quantities, as did reports of soldiers in uniforms and equipment typically worn by the Chinese military.71 Official intelligence reports described the once relatively quiet northern provinces as a flashpoint. Main force attacks there, compared with the rest of the country, increased from 6 percent in 1963 to 13 percent in 1964.72 Although the total number of enemy killed country-wide decreased from 20,573 in 1963 to 16,785 in 1964, the number killed in the northern provinces tripled from 664 to 1,887.73 During 1963, 10 percent of the ARVN soldiers killed came as a result of fighting there, an increase of nearly 25 percent.74

In light of the increase in NVA activity, Johnson approved intelligence collection operations off North Vietnam, over the demilitarized zone, and along the Ho Chi Minh trail. He also encouraged the RVN government and military to go on the offensive against the NLF. The results of the latter, however, were not what Johnson expected. American military advisors reported wholesale corruption and incompetence at the highest levels of the military and low morale in the ranks as the primary reason for the ARVN’s failures. Johnson sought a wider role for U.S. forces, and the Tonkin Gulf incidents in August 1964 gave him the justification he needed to “take all necessary measures to repel any armed attack against the forces of the United States and to prevent further aggression.”75 By the end of 1964, the South Vietnamese population’s diminished confidence in their government and the ARVN was impacting the country’s daily affairs. The ever-present fear of yet another military coup, coupled with the continuing trend of battlefield defeats, threatened the decades-old American effort to build a strong central government and national military in South Vietnam. The consensus was that the country was sure to collapse if the RVN government, with the assistance of the United States, did not reverse the “losing trend.”76 During an official visit in January 1965, one of President Johnson’s top national security advisors, McGeorge Bundy, remarked that “the situation in Vietnam is deteriorating and without new US action, defeat appears inevitable—probably not in a matter of weeks or even months, but within the next year or so. There is still time to turn it around, but not much.”77

Still at an impasse as to the depth and degree of direct U.S. military involvement, Johnson was nonetheless resolute in keeping the south free from Communism despite the desperate political and military situations. He believed he was doing as much as he could politically. Militarily, however, Johnson acknowledged that there was still more the United States could, and would likely have to, do. He reached a decision point when the NLF attacked U.S. forces based at Pleiku and Qui Nhon on 7 and 10 February 1965, killing a combined total of 33 servicemembers and destroying or damaging 52 aircraft.78 Similar to the attack against the RVN-U.S. airbase at Bien Hoa outside Saigon on 1 November 1964, NLF guerrillas infiltrated multiple layers of security with relative ease before attacking aircraft revetments and personnel billeting. Unlike in the days following the events at Bien Hoa, however, Johnson responded to the Pleiku and Qui Nhon attacks with Operations Flaming Dart I and II. For the next three weeks, U.S. aircraft struck an NVA compound located at the port city of Dong Hoi in southern DRV and infiltration routes leading into the RVN from across the demilitarized zone and from Laos. Johnson and senior members of his cabinet viewed the air strikes as retaliatory actions and the first steps in pressuring North Vietnam to end its support of the NLF.79

Following a mid-February 1965 inspection tour of the military bases supporting the Flaming Dart airstrikes, General Westmoreland’s deputy commander, Army general John L. Throckmorton, voiced his concerns about the security of these installations as well as the protection of U.S. servicemembers and aircraft, citing the attacks at Bien Hoa, Pleiku, and Qui Nhon as evidence to back his concerns.80 Troubled by his deputy commander’s assessment, Westmoreland sought permission from Admiral Sharp to employ the 9th MEB, afloat in the South China Sea since January, to secure the Da Nang airbase.81 Westmoreland’s request for Marines—the second such request in three months (the first came after the Bien Hoa attack)—renewed the debate between civilian and military officials regarding the use of U.S. ground forces and the capacity in which they were to be employed.

The arrival of the 9th MEB marked the end of the advisory-and-assistance era and opened a new phase of American involvement. The absence of any study on the Marines’ arrival from the historiography of the Vietnam War leads many to view the Da Nang landing as hasty, though long before the landing the Marine Corps already owned a vital part of the plan for combating Communist ground forces and stabilizing Indochina and the RVN from the start. Multiple plans directing military intervention during the later stages of the First Indochina War put Marines as the vanguard of any U.S. force committed to the region.

Although the circumstances prompting the landing at Da Nang were different than planners originally anticipated, the idea that it would be Marines landing there and operating beyond Da Nang was anything but hastily decided or new. Even after securing Da Nang, there was still a predetermined plan for what the Marines would do next; yet for reasons unknown, historians tend to overlook the central purpose of both, lessening the meaning and significance of the Marine commitment to the RVN and perpetuating a misleading view of their intended role.

•1775•

Endnotes

- The quote in this piece’s title is from LtCol Ernst Otto, German Army (Ret), “The Battles for the Possession of Belleau Woods, June 1918,” Proceedings (U.S. Naval Institute Press) 54, no. 11 (November 1928): 941. Maj Gary Wayne Cozzens, USMCR, passed away on 31 July 2018. Major assistance for this article was provided by the late George B. Clark, Col Walt Ford (Ret), LtCol Pete Owen (Ret), and Angela Anderson. For more about Cozzens, see p. 75.

- Elton E. Mackin, Suddenly We Didn’t Want to Die: Memoirs of a World War I Marine (Novato, CA; Presidio Press, 1993), 17; Dick Camp, The Devil Dogs at Belleau Wood: U.S. Marines in World War I (Minneapolis, MN: Zenith Press, 2008), 75; and George B. Clark, Devil Dogs: Fighting Marines of World War I (Novato, CA: Presidio Press, 1999), 102. Clark’s Devil Dogs is considered by many to be the best single-volume history of the Marines in World War I.

- Otto, “The Battles for the Possession of Belleau Woods, June 1918,” 941.

- David C. Homsher, “Securing the Flanks,” Marine Corps Gazette 90, no. 11 (November 2006): 82.

- Capt John W. Thomason Jr., Fix Bayonets! (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1926), x–xiii. This book is considered by many to be the finest fictional book written about the Marines in World War I. Though classified as fiction, it is thinly veiled fiction and, in many cases, Thomason uses actual names of the Marines of the 49th Company. The first chapter, “Battle-Sight,” is the story of the attack on Hill 142. Thomason was not an original member of the 49th Company that began the assault on 6 June. Research by the late George B. Clark indicates that Thomason arrived with replacement troops on 7 June. See John W. Thomason Jr., The United States Army Second Division Northwest of Chateau Thierry in World War I, ed. George B. Clark (Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 2006); and John W. Thomason Jr., “Second Division Northwest of Chateau Thierry, June 1–July 10, 1918,” unpublished manuscript, 1928, Personal Papers, 1918–1950, Dolph Briscoe Center for American History, University of Texas at Austin, 223n807. The former is perhaps the most accurate book written about the battle of Belleau Wood, yet it was not published until 2006. Thomason wrote the report in the 1920s, but quit in frustration after several of the high-ranking officers involved in the battle tried to sanitize his account.

- Hulbert was later killed in action at Blanc Mont on 4 October 1918.

- Cukela later received the Medal of Honor for actions at Sois- sons on 18 July 1918.

- George B. Clark, The Fourth Marine Brigade in World War I: Bat- talion Histories Based on Official Documents (Jefferson, NC: McFar- land, 2015), 26–28, 32.

- Clark, The Fourth Marine Brigade in World War I, 30–32.

- Thomason, The United States Army Second Division Northwest of Chateau Thierry in World War I, 81–82.

- Thomason, The United States Army Second Division Northwest of Chateau Thierry in World War I, 74.

- Homsher, “Securing the Flanks,” 88.

- Otto, “The Battles for the Possession of Belleau Woods, June 1918,” 943; and Thomason, The United States Army Second Division Northwest of Chateau Thierry in World War I, 89–90.

- Thomason, The United States Army Second Division Northwest of Chateau Thierry in World War I, 74.

- Thomason, The United States Army Second Division Northwest of Chateau Thierry in World War I, 76.

- Clark, Devil Dogs, 102. The self-powered, water-cooled machine gun was designed by American inventor Hiram S. Maxim in 1884; it fired at a rate of up to 600 rounds per minute. In 1887, it was introduced to the German Army, which quickly developed its own version of the Maxim machine gun and manufactured 12,000 of them by the beginning of World War I in August 1914. “How the Machine Gun Changed Combat during World War I,” Norwich University online, accessed 19 November 2018; and Paul Cornish, “Machine Gun,” International Encyclopedia of the First World War, accessed 19 November 2018.

- Col John W. Thomason Jr., . . . and a Few Marines (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1943), 475. Though a fictional short story, Thomason describes the attack on Hill 142. The actual German defenders might not have been Prussian. Swank is defined as ostentation or arrogance of dress or manner; swagger.

- Thomason, The United States Army Second Division Northwest of Chateau Thierry in World War I, 84; and Otto, “The Battles for the Possession of Belleau Woods, June 1918,” 944.

- Times are confusing, even in source documents. Located in northern France, the sun would rise on Hill 142 at about 0348. See National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration Sunrise/ Sunset Calculator, accessed 28 December 2017. The Allies used Western European Time, while the Germans used Central Euro- pean Time, which was one hour ahead of the Allies. Both sides used daylight savings time. Otto, “The Battles for the Possession of Belleau Woods, June 1918,” 942.

- Capt George W. Hamilton letter to Commandant of the Marine Corps, 19 November 1919, quoted in Mark Mortensen, George W. Hamilton, USMC: America’s Greatest World War I Hero (Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 2011), 210.

- The map used by U.S. forces in this attack was Chateau-Thierry Sector, June 6–July 16, 1918, at 1/20,000 scale. Summary of Operations in the World War (Washington, DC: U.S. Army Map Service, 1944).

- Field Orders No. 1, 4th Brigade, June 5, 10:25 p.m., as cited in 2d Division, Summary of Operations in the World War (Washington, DC: American Battle Monuments Commission, 1944), 11, 102.

- The map referred to was the old Meaux-50,000 hachured map produced by Depot de la Guerre in 1832 and corrected in 1912. It was almost worthless. Hachure refers to the short lines used for shading and showing surfaces in relief and in the direction of the slope. Thomason, The United States Army Second Division North- west of Chateau Thierry in World War I, 81.

- Mortensen, George W. Hamilton, USMC, 210; and Clark, The Fourth Marine Brigade in World War I, 32.

- Clark, The Fourth Marine Brigade in World War I, 218.

- Mortensen, George W. Hamilton, USMC, 210.

- Galliford was temporarily attached to the 66th Company from the 17th Company from 1 to 9 June as commanding officer and returned to the 17th Company on 10 June. The actual commanding officer of the 66th Company was Capt Raymond F. Dirksen, who was sick in the hospital. U.S. Marine Corps Muster Rolls, 1893–1958, microfilm publication T977, 460 rolls, Record Group (RG) 127, ARC identifier 922159, National Archives and Records Administration (NARA), Washington, DC; Thomason, The United States Army Second Division Northwest of Chateau Thierry, 83–84; and Clark, The Fourth Marine Brigade in World War I, 32–33.

- Thomason, The United States Army Second Division Northwest of Chateau Thierry, 83–84.

- The “square woods” was not shown on the Marines’ maps. It would cause problems later in the day when Hamilton would misinterpret his objective and extend too far forward, eventually withdrawing back to his objective on the forward slope of Hill 142. Thomason, The United States Army Second Division Northwest of Chateau Thierry, 84.

- Thomason, The United States Army Second Division Northwest of Chateau Thierry, 85.

- Mortensen, George W. Hamilton, USMC, 211–12.

- Kemper F. Cowling, comp., and Courtney R. Cooper, ed. “Dear Folks at Home - - -”: The Glorious Story of United States Marines in France as Told by Their Letters from the Battlefield (Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin, 1919), 126.

- Capt Jonas Platt, “Holding Back the Marines: They Would Go to Germany and Bag the German Army,” Ladies Home Journal, September 1919, 114. Boche or bosche was pejorative slang used by French and American soldiers to refer to German soldiers.

- Cowling and Cooper, “Dear Folks at Home - - -,” 87–88.

- Keller Rockey commanded the 67th Company earlier. He would later command the 5th Marine Division on Iwo Jima dur- ing World War II and retired as a lieutenant general in 1950. Thomason, The United States Army Second Division Northwest of Chateau Thierry, 83, 87; and Clark, Devil Dogs, 100.

- Clark, The Fourth Marine Brigade in World War I, 36.

- George B. Clark, Citations and Awards to Members of the 4th Marine Brigade (Pike, NH: Brass Hat, 1993), 18. Original awards were the Army Distinguished Service Cross (DSC) and Silver Star Citation. See also George B. Clark, A List of Officers of the 4th Marine Brigade (Pike, NH: Brass Hat, 1995), 3–20; Clark, Cita- tions and Awards to Members of the 4th Marine Brigade, 2–52; and Jane Blakeney, Heroes: U.S. Marine Corps, 1861–1955: Armed Forces Awards, Flags (Washington, DC: Guthrie Lithograph, 1957).

- Mackin, Suddenly We Didn’t Want to Die, 17–18.

- Clark, Citations and Awards to Members of the 4th Marine Brigade, 25; Clark, The Fourth Marine Brigade in World War I, 35; and Camp, The Devil Dogs at Belleau Wood, 75–77.

- Mortensen, George W. Hamilton, USMC, 78.

- Clark, Citations and Awards to Members of the 4th Marine Brigade,13.

- Clark, Citations and Awards to Members of the 4th Marine Brigade,18. Because the muster rolls indicate only “wounded,” not the na- ture of the wounds, it is has not been possible to identify the Marine who lost his hand nor the specific injury that resulted in him losing his hand; however, since he grabbed the gun’s muzzle, his hand may have been shot off.

- Thomason, The United States Army Second Division Northwest of Chateau Thierry, 89.

- Thomason, The United States Army Second Division Northwest of Chateau Thierry, 86–87.

- Thomason, The United States Army Second Division Northwest of Chateau Thierry, 90.

- Mortensen, George W. Hamilton, USMC, 212.

- George B. Clark, ed., Devil Dog Chronicle: Voices of the 4th Marine Brigade in World War I (Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 2013), 163.

- Maj Littleton W. T. Waller Jr., Final Report of the 6th Machine Gun Battalion (Pike, NH: Brass Hat), 15; and LtCol Frank E. Ev- ans, “Demobilizing the Brigades,” Marine Corps Gazette 4, no. 4 (December 1919): 303–14.

- Cowling and Cooper, “Dear Folks at Home - - -,” 127.

- Clark, Devil Dogs, 210n41.

- Platt, “Holding Back the Marines,” 114.

- See Robert Asprey, At Belleau Wood (New York: G. P. Putnam’s Sons, 1965), 151. Hunter also was known as “Beau.”

- Platt, “Holding Back the Marines,” 114.

- Clark, Citations and Awards to Members of the 4th Marine Brigade, 25; Clark, The Fourth Marine Brigade in World War I, 35; and Camp, The Devil Dogs at Belleau Wood, 75–77.

- Mortensen, George W. Hamilton, USMC, 212–13.

- Clark, Citations and Awards to Members of the 4th Marine Brigade, 38.

- Cowling and Cooper, “Dear Folks at Home - - -,” 127–28.

- Clark, Devil Dogs, 105–6.

- 2d Division, Summary of Operations in the World War, 10, 11; and Clark, Devil Dogs, 106.

- Clark, Devil Dogs, 110.

- Thomason, The United States Army Second Division Northwest of Chateau Thierry, 88.

- Thomason, The United States Army Second Division Northwest of Chateau Thierry, 89.

- Otto, “The Battles for the Possession of Belleau Woods, June 1918,” 944.

- Maj Edwin N. McClellan, “Capture of Hill 142, Battle of Belleau Wood, and Capture of Bouresches,” Marine Corps Gazette 5, no. 3 (September 1920): 284.

- Clark, The Fourth Marine Brigade in World War I, 38.

- Clark, Citations and Awards to Members of the 4th Marine Brigade, 20–21.

- Clark, Devil Dogs, 104–5.

- Thomason, The United States Army Second Division Northwest of Chateau Thierry, 90.

- Cowling and Cooper, “Dear Folks at Home - - -,” 128.

- Cowling and Cooper, “Dear Folks at Home - - -,” 128; and Clark, Citations and Awards to Members of the 4th Marine Brigade, 23. Born Ernest August Janson on 17 August 1878, Janson spent 10 years in the Army before he enlisted in the Marine Corps at Marine Barracks Bremerton, WA, under the name of Charles F. Hoff- man. On 3 January 1921, he submitted a letter to Headquarters Marine Corps requesting that his record be corrected to reflect his given name (Ernest August Janson). According to the letter, Janson enlisted in the U.S. Army in late 1899 but deserted about July 1900. On 10 November 1900, Janson reenlisted in the Army as Charles Hoffman. He honorably served in the Army under the name Hoffman before enlisting in the Marine Corps on 14 June 1910 under the same name. Headquarters accepted the request in late January 1921 and corrected all of Hoffman’s service records to the name of Janson. Janson retired from the Marine Corps as a sergeant major on 30 September 1926.

- Clark, Devil Dogs, 107.

- Thomason, The United States Army Second Division Northwest of Chateau Thierry, 91; Clark, The Fourth Marine Brigade in World War I, 39; and, Otto, “The Battles for the Possession of Belleau Woods, June 1918,” 945.

- Cowling and Cooper, “Dear Folks at Home - - -,” 129.

- Clark, Citations and Awards to Members of the 4th Marine Brigade, 47.

- Clark, Citations and Awards to Members of the 4th Marine Brigade, 40.

- Clark, Devil Dogs, 109–10.

- Clark, The Fourth Marine Brigade in World War I, 39.

- Thomason, The United States Army Second Division Northwest of Chateau Thierry, 91.

- Clark, Devil Dogs, 101, 128.

- Clark, Devil Dogs, 207.

- Clark, Devil Dogs, 202.

- Clark, Devil Dogs, 112–13.

- Otto, “The Battles for the Possession of Belleau Woods, June 1918,” 962.

- Clark, The Fourth Marine Brigade in World War I, 39.

- Clark, The Fourth Marine Brigade in World War I, 39.

- Mackin, Suddenly We Didn’t Want to Die, 44.

- Mackin, Suddenly We Didn’t Want to Die, viii.