The U.S. Marine Corps’ reputation as an elite outfit in the military served as the foundation of its World War II recruiting campaign. The looming manpower shortage sparked both the creation of women’s auxiliaries as well as massive recruiting drives for men and women. For the Marine Corps, recruiting women required a subtle, though significant, shift in both recruiting materials and strategy. Male recruits were encouraged to join an elite Service, to be among the first to the front, and to become “real men” in the process. Female recruits were presented with the same materials but with a vitally important difference. They were invited to join an elite Service with a grand tradition of excellence and to support the best fighters in the military, but they would remain “real women.” This subtle modification in the recruiting message drew highly sought-after women to the Marine Corps and, quite unexpectedly, helped reshape the rules of femininity in the United States.1

The foundation of Marine Corps recruiting was the belief that the Corps was the finest organization, only taking the best and making them better.2 Since World War I, Marine Corps recruiting campaigns emphasized the Corps’ elite status, “portray[ing]

Marines as the finest, toughest, most elite warriors in the U.S. military.”3 The World War I recruiting campaigns solidified a recognizable image of the type of men who chose to join the Corps, and World War II efforts were consciously based on these popular constructions.4

The real challenge for recruiters was finding a balance between the Marine Corps’ staffing requirements and the culturally accepted workplaces for women. Civilian administrative office work was largely done by women in the 1940s. The Marine Corps needed clerks, typists, stenographers, messengers, and other office workers to make their administrative structure function efficiently. The Marine Corps’ reputation as fighters and infantrymen—before anything else—made the concept of a woman Marine an incongruous idea with this perceived cultural reputation. The recruiting campaign had to attract unique women who still fell within the socially accepted parameters of womanhood. As a result, recruiting materials aimed at potential women Marines layered the idea of Marine elitism over existing structures of femininity to create the image of an ideal recruit. The recruiting posters were designed primarily to encourage viewers to join the Marine Corps, make more Marines, and win the war, not change the rules of gender or push the boundaries between men and women.

One of the foundational themes of the male recruiting posters was that the Marines would make real men out of recruits. For a number of reasons, including the obvious, recruiting posters directed at women could not take the same approach. While posters for male recruits promised a significant transformation, posters developed for female recruits argued that women would still be feminine even after becoming Marines. There was real concern, among southern congressmen specifically, that military service would draw women away from their traditional gender roles in the home, leading to a social collapse.5 For many in the military, even the thought of women in uniform pushed the boundaries of gender too far. Following the creation of the Women’s Army Auxiliary Corps (WAAC), soldiers wrote home with rumors that the women were prostitutes for soldiers. In some cases, concerned parents wrote to the WAAC leadership about their fears.6 For the Marine Corps specifically, the appearance of propriety and respectability was the most important factor in the design of its recruiting plan: “In all interpretations of activities . . . there must be the inference, through reflection, that the Women’s Reserve is possessed of a greater dignity and peopled by higher caliber personnel than any contemporary women’s force. Suggestions contained herein accept the foregoing as a primary dictate.”7 Because joining the military was a direct challenge to the traditional American strictures of femininity and respectable behavior, the women’s auxiliaries and the Marine Corps, in particular, emphasized that their recruits would remain respectable ladies even as they took on a variety of jobs outside the home that may have previously been reserved for men.

In the first half of the twentieth century, women moved into many formerly male-coded occupations. The needs of the country and the demands of war had created a massive increase in industrial production requirements that precipitated a labor shortage. Concurrently, the military’s manpower needs increased for both combat and support roles. During World War I, the military fielded approximately two combat soldiers for every support soldier. By World War II, the ratio had shifted to two combat soldiers for every three in support roles.8 Women filled the workforce gaps in industry, agriculture, and, ultimately, the military.9 Women also worked in offices as secretaries, stenographers, typists, and clerks and had served in the U.S. Army, Navy, and Marine Corps in World War I.10 On 30 July 1942, President Roosevelt signed the legislation authorizing enlistment and commissioning of women’s naval reserves.11 The WAAC,12 Women Accepted for Volunteer Emergency Service (WAVES),13 and the Coast Guard Women’s Reserve (SPAR)14 were instituted in the next few months and immediately began advertising for not just their particular branch but the idea of women serving in the military. Despite the traditional view of women as homebound nurturers, thousands of young women answered the call to arms and joined.15

Military leaders were reluctant to include women in their branches, but the Marine Corps in particular was vehemently opposed to the idea. Marine Corps Commandant Lieutenant General Thomas Holcomb was determined to maintain the elite status of his Service, which he believed was the result of its homogeneity: a service of white men. He believed that including women would “ruin” the Marine Corps, and said as much to Congressman Melvin J. Maas, who introduced the Women’s Reserve legislation.16 Obeying the presidential order to integrate, Holcomb implemented far more stringent requirements for women than those applied to men.17 The Marine Corps’ standards for men were higher than the other branches,18 and the additional hurdle winnowed the women applicants even further.

In the months between November 1942 and February 1943, the Women’s Reserve and the Procurement Division had to conceptualize, design, and execute multiple types of recruiting materials to attract the specific women they wanted.19 The first decision was “to influence the choice of women who have already, or who are in the process of making up their minds to don a uniform".20 As a result of their efforts, the division created recruiting brochures, window placards, and posters for display. Some of the materials were destined for national distribution while others were distributed regionally. For the most part, the women’s marketing campaign modeled the men’s campaign, selling the elite status and tough reputation of the Marines Corps. Despite the intent to discourage women from applying, the higher standards actually strengthened the elite reputation of the Marine Corps. Many high-quality female applicants were drawn by the Corps’ reputation, so much so that the Women’s Reserve met its recruitment goals (18,000 women by June 1944) six months ahead of schedule.21 The Marine Corps began structuring its Reserve in November 1942, searching for a woman to serve as director, for a small staff, and for space for training and housing, and for creating a regulatory structure. The new group was activated on Sunday, 13 February 1943 as the Marine Corps Women’s Reserve.22

The creators of the Women’s Reserve deconstructed the ideal of Marine-hood to a few fundamental components: tradition, being the first to fight, group membership and cohesion, and an elite status. All of these parts were combined to form the basic structure of Marine recruitment in World War II. The ideal changed from building men to building Marines. Recruiting materials emphasized that the female recruits would be equal with the men, with the same pay, same rank, same discipline, and the same name. The posters recast essential markers of femininity, such as clothing, makeup, and hairstyle, to emphasize belonging. A prominent example can be seen in the emphasis placed on women wearing feminine skirted uniforms that were still in colors unique to the Marine Corps. The advertisements accessed cultural constructions of gender, social expectation, and ideals of masculine and feminine performance to successfully draw both men and women into a gender-integrated Marine Corps.

In the 1940s, U.S. society was still attached to the Victorian ideals of separate spheres and proscribed places for men and women. Women worked in “respectable” fields, such as nursing, teaching, and office support staff. Yet women consistently pushed the boundaries of acceptability and respectability, sometimes due to financial necessity but often for personal fulfillment. For example, women aviators (or aviatrixes) not only flew their own planes, they also maintained them. Women worked the counters at their families’ shops, worked their families’ farms, and worked in factories to send money back to their struggling families. Women also owned their own businesses or worked in positions of power as stockbrokers, police officers, and manual laborers.23

As women advanced into male-dominated workspaces and took their place in the public sphere in the 1940s, they were faced with accusations of mannishness, both mental and physical. Despite the societal changes of the previous few decades, women still needed to be identified as such. With the start of World War II and the increased need for workers in all industries, women and the businesses and military branches recruiting them were faced with a unique opportunity that was fraught with challenge: how to convince women to perform nontraditional work while preserving the traditional gender binary.24 While it seems a small thing, the crucial aspect of the gender binary is the sexes’ legibility to other people; that is, it must be recognizable to others. Even as women took jobs as mechanics, drivers, logisticians, and factory workers, they were actively encouraged to maintain feminine appearances. Subtle cues in the Marine Corps WWII-era posters indicate that the women shown fulfilled the traditional feminine space with things like makeup, nail polish, and fashionably styled hair. The emphasis in Marine Corps recruiting on the uniforms and, later, cosmetics designed specifically for the Marine Corps Women’s Reserve are both ways women could achieve what Judith Halberstam calls “a cardinal rule of gender: one must be readable at a glance.”25

Dramatic changes in American society opened new opportunities to women across a wide swath of industries, yet the underlying implication of the advertising was that women’s work during the war would be temporary. Once the conflict ended and the men came home, the women would all return to the domestic sphere and welcome their returning soldiers. This assumption had been in place be- fore the war, as young single women were expected to work only until they married. The onset of combat required employers to hire married women and mothers of young children, despite the taboo against it. Enticing married women and homemakers to enter the workforce supported the connections between housework and industrial work, and women’s employment during World War II reinforced the gendered separation of labor.26

Another method used to draw women into the workforce was to feminize the tasks involved. No matter how heavily masculine the job had been prewar, when women were needed to take over vacant positions, the work was described as similar to housework, using the same terminology or making a direct comparison. Working a lathe was compared to an electric washing machine, welding to sewing, a drill press to a juicer. Further, newsreels and printed articles emphasized how pretty and feminine war workers remained despite their masculine-coded tasks: “As if calculated to assure women—and men—that war work need not involve a loss of femininity, depictions of women’s new work roles were overlaid with allusions to their stylish dress and attractive appearance.”27

While new workers were enticed into industry, the Marine Corps targeted the pool of women clerical workers. A radio announcement first made on 13 February 1943 clearly articulates the role women were expected to play in the Marine Corps.

The men of the Corps are traditionally famous for out-fighting the enemy anywhere on the globe . . . These stout-hearted men are now needed overseas. Your service will be important not only because of the military duty itself, but also because you will be unleashing another fighting Marine to advance against the enemies over there.28

Office work had become respectable work for women at all stages of life by this point, and professional competence was now a stoutly middle-class replacement for the refinement of an upper-class woman. Carole Srole argues that the shift in gendered office work occurred in the late nineteenth century, making it more acceptable for women to work as clerks and typists. At the height of the Industrial Revolution, women worked in factories and shops as domestic workers and teachers. With the advent of technology, such as typewriters, women flooded shorthand and typist positions, work previously done almost exclusively by men. The arrival of women into the workforce pushed both men and women to recreate their images as office workers and separate from other classes of laborers. Masculine and feminine traits were intermingled to create a new aesthetic of professionalism, one that was applicable to both sexes with only a few differences, including ambition, mental acumen, and independence.

Women still faced challenges, created by men who tried to cast all working women as immoral or incompetent, and created a new, respectable image of the professional businesswoman. The professional businesswoman had all the characteristics of the classic image of the middle-class businessman but also the empathy and caring nature of an upper-class “lady” without the hyperfeminine weaknesses. This woman stood in contrast to the “typewriter girl,” or the “gold-digger” of questionable morals who was only working long enough to catch a husband. The businesswoman became a respectable member of the middle class as both men and women created new, “professional” identities that were distinguishable from earlier models of both masculinity and femininity.29

Shifts in who did the work also precipitated changes in how the work was perceived. Reframing what work entailed recast the tasks as respectable for women, though the job itself was devalued in the process. For example, in the automobile and electrical manufacturing industries, women were assigned jobs that were considered “light work.” Even if men and women performed the same task, different wage rates meant the men were paid more for the same job. However, there was no continuity across industries or geography, indicating that descriptions of “women’s work” varied according to each employer’s preconceptions of propriety and ability.30

The shifts in workplace norms also pushed a change in gender itself. Gender is expressed through behaviors, which are codified through an agreed-upon performance of those behaviors. Judith Butler describes gender as “the repeated stylization of the body, a set of repeated acts within a highly rigid regulatory frame that congeal over time to produce the appearance of substance, of a natural sort of being.”31 Gender is created when socially agreed-upon behaviors are performed repeatedly for others and the self. As such, people perform behaviors they associate with their gender identities. According to Butler, there is no original gender, merely performances based on an individual’s perception of the socially described gender; it is socially created through unspoken conversations between members of a social group. That being said, this does not mean that gender is not real, rather, it means that no gendered behavior or practice is fixed, and that any gendered or ungendered behavior can be inscribed on a set of behaviors by common consensus.32

Recruiters for the Women’s Reserve had to convince women that they could join the Marine Corps without compromising either the women’s femininity or the Corps’ reputation as the toughest outfit in the U.S. Armed Services. Yet the core of the Marine Corps advertising for both men and women shifted away from the prewar campaign of “making men” to simply “making Marines.” USMC recruiting posters that targeted men and were focused on the Corps’ traditions and history. Some materials directly recalled historical events with images or direct references of the Marine Corps’ birthday of 10 November. Other materials showed Marines wearing the iconic blue dress uniform, inviting the viewer to join, or used the eagle, globe, and anchor emblem alone to identify the Marine Corps.

Many posters directed toward male recruits featured action, an allusion to the first to fight reputation of the Marine Corps. An early poster bluntly asks the viewer “Want Action? Join U.S. Marine Corps!”33 The Marine extends his hand forward toward the viewer, inviting him into the picture. A plane flies in the distance, above a series of ships, most likely troop transport ships. The Marine has a welcoming expression on his face, as if he is identifying the viewer as a man worthy of becoming a Marine. Instead of encouraging the viewer to do his part—to enlist, to answer the call to arms—the poster instead presumes the viewer is already planning to join the military and the only question is how much “action” the man would like to see. Here we see the presumption of service—the man viewing this poster has already decided to join and only needs to choose his branch of Service.

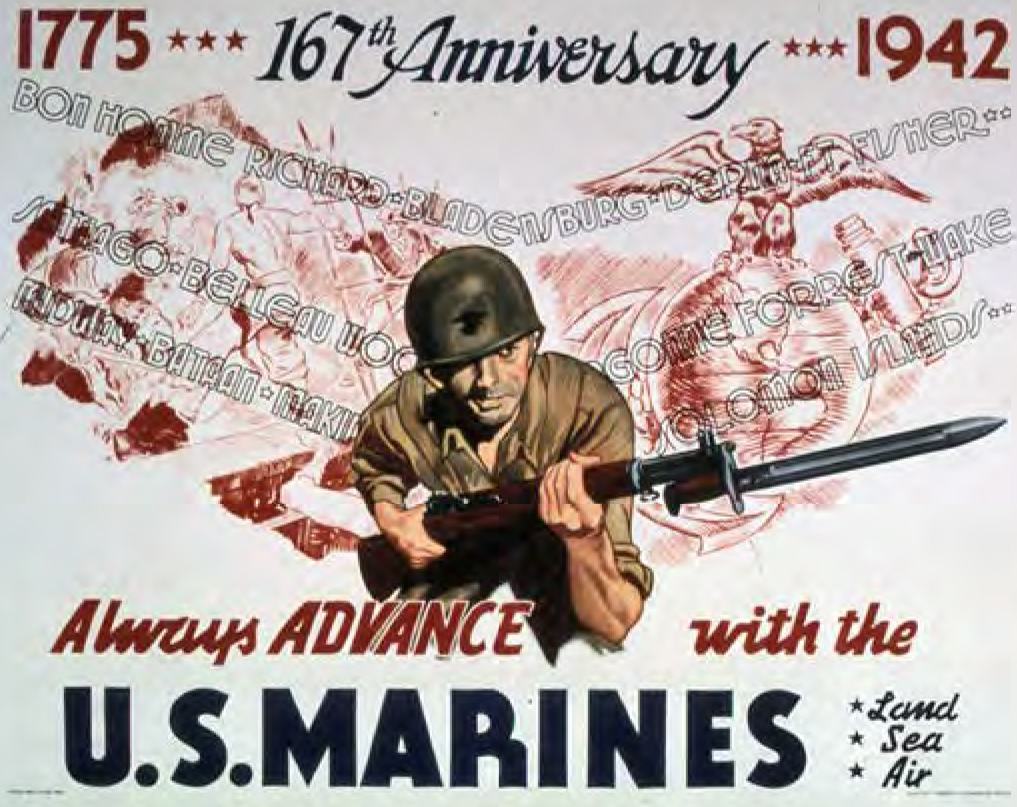

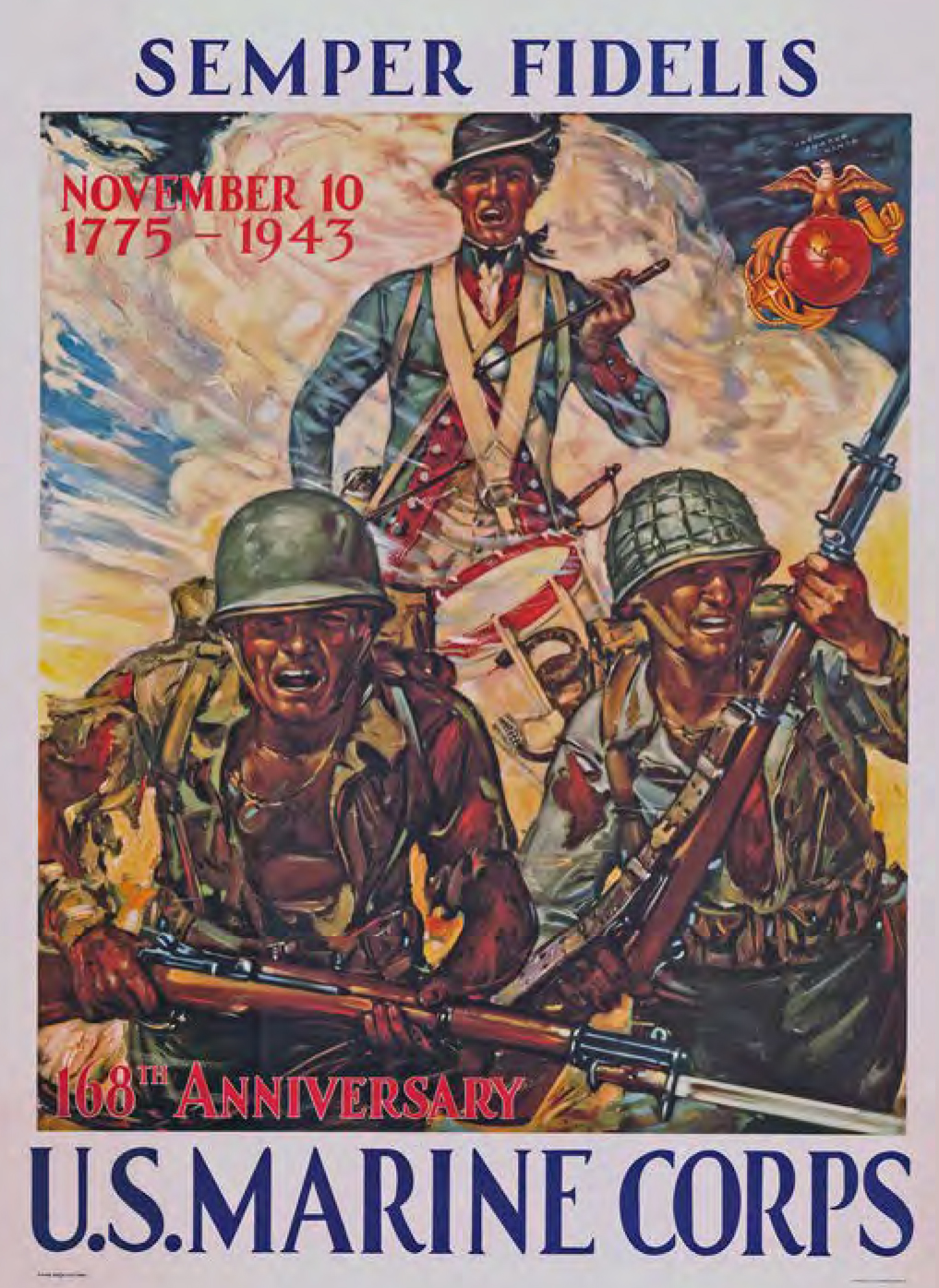

The most direct recruit advertising, used to push the Corps’ elite reputation and history, were produced in 1942 and 1943 to both commemorate the Marine Corps’ birthday and to recruit in honor of it. The 1942 poster follows the red, white, and blue color scheme found in other posters and uses a two-part background image: the Marine Corps emblem on the right and a shipboard battle scene on the left, with names of famous Marine battles overlaid. A contemporary Marine stands in the center, holding a rifle with bayonet fixed, staring at an enemy to the right of frame. The text, “Always Advance with the U.S. Marines,” plays into the Marine reputation as the outfit that sees the most action. The battle scene reminds the viewer that the Marines are soldiers of the sea, an amphibious force. The names of battles, up to and including recently won island battles, emphasize both the tradition and the reputation of the Marine Corps without explicitly stating either. The poster creates a powerful image, but the open composition and lack of visual context detaches it from reality.34 The 1943 poster provides more visual context and less cheerleading. The text is simple including the Marine Corps motto, “Semper Fidelis,” and the anniversary date and years, “November 10, 1775–1943.”

“Want Action.” A World War I-era U.S. Marine Corps recruiting poster for men. U.S. National Archives

“Always Advance with the U.S. Marines.” This 1942 Marine Corps recruiting poster was also used to mark the 167th anniversary of the Corps. U.S. National Archives

“Semper Fidelis.” In this 1943 Marine Corps anniversary poster, a Revolutionary War drummer exhorts Marines in battle. U.S. National Archives

Two Marines in jungle gear are charging ahead toward the viewer. The damage done to their uniforms indicates that they have been in battle and are continuing the fight. The background is a cloud, recalling the fog of war, and a Continental Marine-era drummer exhorts the Marines to further valor. The eagle, globe, and anchor emblem in the top right corner rests on a dark blue background rather than on the cloud. In this poster, the connection to tradition and history is most important. The Revolutionary-era Marine connects the modern Marines to the nation’s history, and the insignia and motto connect them to other Marines—a sign of group cohesion. The drummer is the driving force behind the two Marines. The poster illustrates the tradition and history driving the Marines, and it implies that the male recruit will be part of an organization with both a storied past as well as a powerful present and future.35

Other posters from the time focused on the present and future of the Marine Corps. Aviation was crucial to the war effort, especially in the Pacific theater, where vast distances complicated battle plans. With the Doolittle Raid36 and the success of Allied bombing campaigns in Europe, aviation quickly became a glamorous position, one that all branches advertised.

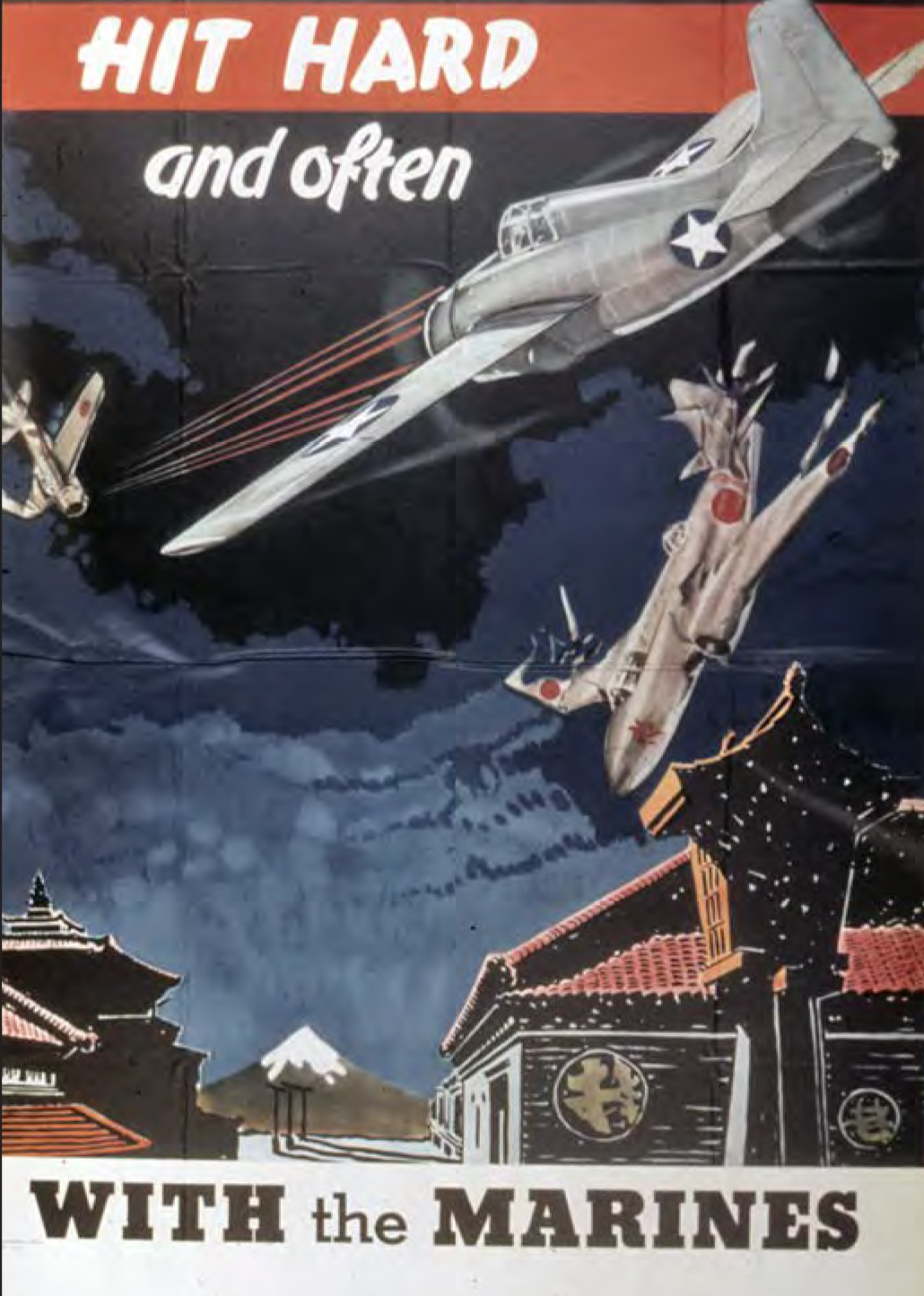

Here, too, the Marine Corps used its first to fight reputation in the aviation-specific recruiting material. In a departure from the generally minimalist posters discussed here, one aviation poster is a complex and vivid scene. A Marine aircraft hangs in the foreground, flying away from the viewer and firing on a Japanese fighter plane in the background, as a Japanese bomber falls in the middle range of the image. The scene is set over a Japanese village, with the iconic Mount Fuji in the distance. The buildings are traditional Japanese wooden residential structures. At the back of the village stands two simple Shinto gateways. The falling bomber appears to be about to crash into one of the houses. The poster invites the viewer to imagine himself as the aviator who takes the fight to the Japanese, reinforcing the Marine reputation as the first to fight. The text reads “HIT HARD and often WITH the MARINES”; this is the most direct reference to Japanese aerial attacks of all the posters.37

Part of the Corps’ elite status is also about looking the part. The iconic dress uniform is one of the Marine Corps’ most distinctive markers, and it was used as a marketing tool. The striking color scheme and expert use of simple design and tailoring techniques make it an almost universally flattering garment. The uniform sets the Marines apart from the other Services visually, making it clear that they are distinctive and separate.

Several posters show a Marine in his iconic dress uniform. A strikingly simple poster shows a Marine at parade rest against an off-white background in front of the word “READY” in red across the top. The remainder of the text falls below the uniform belt, reading “Join U.S. Marines/Land/Sea/Air.”38 The minimalist design lets the uniform do the work. The short, sharp phrasing emphasizes each word, making them stand out, and the red, white, and blue color scheme continues that of other posters. The dress uniform emphasizes the Marine Corps’ uniqueness and acknowledges that the uniform itself is desirable on an aesthetic level.39

“Hit hard and often.” A majority of Marine recruiting posters during World War II incorporated aviation themes, such as a Marine attack on a Japanese village as portrayed in this poster. U.S. National Archives

“READY.” The Marine uniform was a common element in both male and female recruiting posters during World War II as a way to distinguish the Corps from the other military branches also heavily recruiting at the time. U.S. National Archives

Another unique poster makes use of several of the methods discussed above, increasing the complexity of the composition. The poster depicts a night air raid. A spotlight picks out four aircraft silhouettes over a generalized city skyline. A Marine in dress uniform trousers and cover mans an antiaircraft gun in the foreground. The Marine is clearly firing upon the incoming aircraft. The text reads “Always on the Alert, at Sea, on Land, in the Air.” The generalized skyline could be any number of American cities, underscoring the fear that the U.S. mainland was as vulnerable to attack as Hawaii and Alaska had proven to be. This poster marks the individual as a Marine by his trousers, and implies that he was involved in a formal, noncombat event when the attack began. Because Marines are “always on the alert,” he was able to establish a defensive position in time to protect the city. Once again, this image reinforces the ideal of the Marines as elite and the first to fight. Instead of interacting with the viewer, the scene merely focuses on the individual. By telling a single Marine’s story, the poster reinforces Marine Corps values and invites the viewer to become a part of the storied Corps.40

“Always on the Alert.” In this WWII-era poster, promoters played on the Marine motto “first to fight” as a selling point for the elite nature of the Corps, focusing on a male Marine in dress uniform manning an antiaircraft position during an air raid. U.S. National Archives

These recruiting posters worked from a few basic assumptions. First, that the Marine Corps’ unique traditions were worth upholding, and that they were good ideals to add to one’s own. Second, that the viewer was already planning on joining the military, it was merely a matter of deciding where to go. Third, that the viewer considered himself worthy of the Marine Corps’ elite status. These posters imply that the viewer already sees Marine Corps’ virtues in himself, and only needs to join to bring those seeds to full flower. The concept was clearly carried over to the recruitment material directed toward women. Recruiting posters targeting women also invoked tradition, using images of male Marines fighting.41 Wartime costs limited the number of poster designs and the types of promotional materials that could be produced during the war years. Therefore, the Wom- en’s Reserve used other media along with posters, such as radio advertisements and sponsored spots, newspaper articles and fillers, and strategic use of posters, window signs, car placards, and booklets. The Women’s Reserve was also represented in the broader Office of War Information (OWI) campaign that introduced female recruits to all of the women’s Services.42 The Women Reserves’ main objective was to set it apart from the other women’s Service branches. The most obvious difference was the lack of an official nickname. In a 1944 interview with Life magazine, Holcomb, despite his own reservations, made it clear that the women were as much Marines as the men. “They are Marines. They don’t have a nickname and don’t need one. They get their basic training in a Marine atmosphere at a Marine post. They inherit the traditions of the Marines. They are Marines.”43 In that same spirit, the women’s recruiting material was based on the same premise as the men’s, particularly that the materials targeted women who had already decided to join the military and were still deciding which branch to join.44

A common image used in female recruiting during World War II was that of the first director of the MCWR, Major Ruth Cheney Streeter. In her mid-40s at the time, Streeter was a philanthropist and homemaker with sons in the military. Her biographical details were repeatedly emphasized in Marine Corps press releases along with her most striking accomplishment: she was an aviator with a commercial pilot’s license. She had applied to the Women’s Air Service Pilots (WASP) and was subsequently denied five times for being too old. She carried her passion for aviation with her to the Marine Corps.45 Despite her aviation credentials, Streeter’s main appeal as the director of the newly formed Reserve was her status as a mother, fulfilling the traditional role expected of women. Her entire family worked for the war effort, and her status as a blue-star mother made her more relatable to parents of potential reservists.46

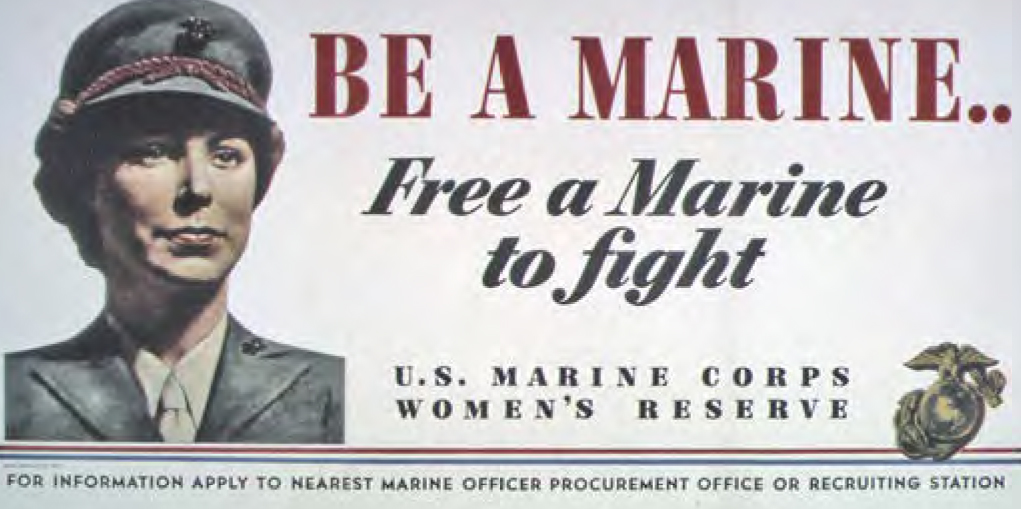

The image of Maj Ruth Cheney Streeter, the first director of the Women Reserves, was often used on recruiting posters for female Marines during WWII. Walter Clinton Jackson Library, University of North Carolina at Greensboro

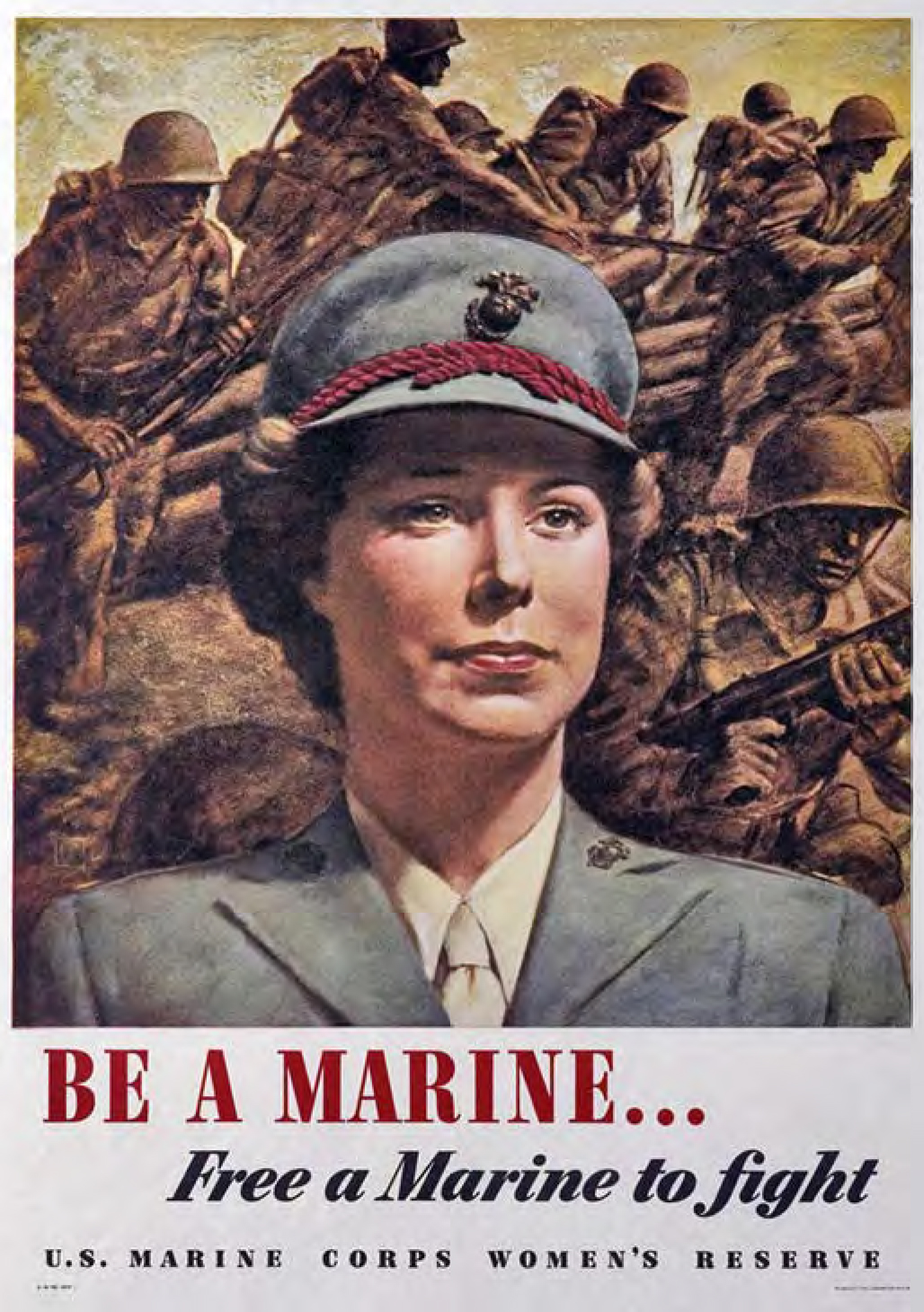

By using Major Streeter’s image, the Marine Corps headed off hints of impropriety and deviance about young women joining the military ranks. Her status as a mother combined with her professional competence made her an ideal leader—one to whom parents entrusted their daughters, and one that enlistees could respect as a leader. In recruiting posters, the contrast between her and male Marines is subtly emphasized. She wears the uniform with red highlights and, while the basis of the uniform is a man’s suit, she appears quite feminine. Streeter wears a fashionable but regulation hairstyle with understated yet appropriately feminine makeup. She looks to the horizon, over the right shoulder of the viewer. Her expression is resolute, showing strength without harshness. An easy confidence comes through, painting Streeter as a person comfortable with the conflicts inherent in her position.

One recruiting poster featuring Major Streeter has a background of Marines charging a beach. The text below the image reads “Be A Marine . . . Free a Marine to fight.” The billboard version shows Streeter on a white background with the same text in red and blue. These strikingly simple designs are a hallmark of many of the Marine Corps recruiting posters. Used within the first months of the female recruiting efforts, the focus on the director and the basic function of the Women’s Reserve transmitted the Corps’ female recruiting message clearly and quickly.

“Be a Marine.” Maj Streeter’s image was repeatedly used for female Marine recruiting as an indirect assurance to possible recruits and their families that the Marine Corps was a safe place to entrust their daughters for military service. U.S. National Archives

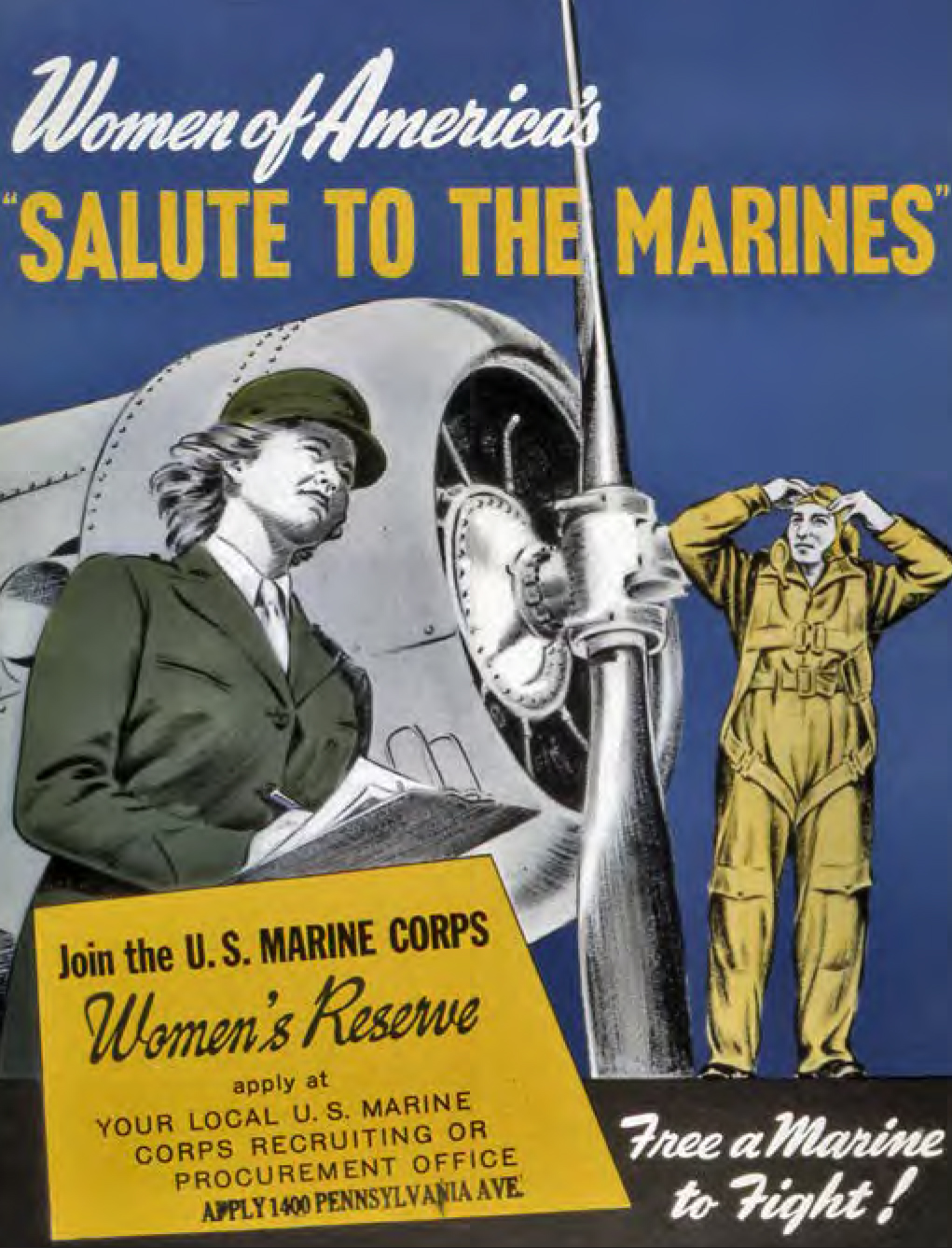

“Free a Marine to Fight.” The recruiting rhetoric behind this poster was similar to the “Be a stand-in for a hero” concept that encouraged women to take on jobs in the Marine Corps to free up their male counterparts for combat-related positions. U.S. National Archives

The short, concise slogans implied that the Marine Corps had no need to sell themselves. Rather, the Marines invited a select few to join them. As such, recruiting materials sold the Corps as an elite organization of singular individuals. By inviting viewers to see themselves through this lens, potential recruits could then take the short step to being Marines. Streeter further emphasized this message in 1943.

To those who have long wanted to be a Marine, I say: the door is now open. The next step is up to you. To those who have not yet found their post of greatest service, here is your opportunity.47

Women-focused recruiting efforts clearly emphasized aviation. Posters not featuring Streeter all focus on a woman in front of a plane. The women hold clipboards, obviously taking an active role in aviation administration during the war. In two of the three posters, the female Marine stands alone. In the third, however, a male aviator looks to the woman reservist for instruction. These women are strong, capable, and have authority that is respected and accepted by their brothers in Service. Showing the women independent from men provides legitimacy to their work, quietly underscoring that these women are different than most and that their ability and dedication are unquestioned.

These three images do more than emphasize aviation as a possible occupation. They also emphasize freedom, strength, ability, competence, and opportunity. The female reservists all look to the right of the frame, slightly upward in the same direction as those featuring Major Streeter. While images of people looking to the sky are common at an airfield, the consistency with Major Streeter’s portrait is significant. Each of these women seems to be looking to the future, but they understand that there is work to be done now, work that may lead to careers after the military.

The aviation posters all reflect the goals of the female recruiting program—being a Marine does not mean being less of a woman. The female Marines are conventionally pretty and sharply dressed in their uniforms. Their hair and makeup is both properly feminine and appropriately military. The women are competent and strong; they are doing important work to support the war effort, but they have not lost the characteristics that make them women. The women Marines are a part of the larger group, with as little differentiation as possible. For example, they wear the service uniform with a coat and the Marine Corps emblem. Their uniforms are well tailored and consistent with the men’s everyday uniforms. How- ever, even though they appear as similar to their male counterparts as possible, they are still clearly women, both feminine and attractive.

“So Proudly We Serve.” Aviation-themed recruiting posters were often used for female Marines during WWII as more than 50 percent of female reservists worked in aviation in some capacity during the war. Marine Corps History Division

“Salute to the Marines.” This Washington, DC, area Women’s Reserve recruiting poster includes several elements commonly used during WWII to attract female recruits, including an aviation theme and a women posed in a well-tailored Marine uniform. U.S. National Archives

The visuals for the window placards and car cards followed the same conventions as the posters. A window placard for display at each procurement office showed a gray scale sketch of a woman Marine on a white background. She is facing the viewer directly, calmly, and confidently. Above her head in bold red letters are the words “Enlist Now,” and below, in black text on a red block, “Inquire Here!” The positioning of the woman Marine in these materials is different, as she faces the viewer directly. This composition gives the viewer a sense that this image is not based on a portrait, but is instead an idealization of the woman looking at the poster, showing her a possible future as a female Marine. She is attractive, neat, fashionable, and sharp. The image starts at the neck, so the only part of the uniform shown is the headgear with the Marine Corps emblem and distinctive braid. Her gaze is almost challenging: “Are you coming?”48 Designed specifically to be displayed in a recruiting office window, the placard would have had a powerful impact. The placard follows the same lines as the “Want Action” and “READY” posters (see pp. 20 and 30) directed at male recruits. The Marine in the poster expects that the viewer has already decided to join the military, and is encouraging him or her to choose the Marines.

Having reached the maximum enlistment of 19,000 by December 1944, recruiting efforts were reduced to a maintenance level pace by the February 1945 birthday. A unique placard was created specifically for the MCWR’s second anniversary. The window placard featured a portrait of a woman reservist over a red, white, and blue background. The text reads, “Be a Stand-in for a Hero!” The slogan skips the subtext of earlier posters and immediately places the combat Marine at the top of the heap. He is a hero and, by implication, standing in for him in a noncombat job makes a woman a hero as well.49 The message again points to the elite status of the Marine and will transfer to the woman Marine.

The MCWR recruiting materials emphasized traditional markers of femininity and womanhood and tied them to the uniform. The women’s uniforms were a major selling point, one that was actively promoted.50 In a surprising connection of the commercial and military worlds, Elizabeth Arden Cosmetics was contracted to create a red nail lacquer, lipstick, and rouge to complement the Women’s Reserve uniform. Named “Montezuma Red,” it was the same distinctive shade of red as the military issue scarf and flashes on the uniform, and was quickly marketed to the MCWR and the nation as a properly patriotic form of makeup.51 Connecting high-end cosmetics to the Women’s Reserve told women already in the Reserve and those considering it that the women of the MCWR were quite feminine, enough so that they had their own unique cosmetic color.52

This female Marine recruiting window placard was used for display in Marine Corps procurement office windows across the nation to attract potential recruits. Marine Corps History Division

Cosmetic company Elizabeth Arden joined the ranks of business supporting the Marine Corps’ ability to recruit females with the release of lipstick and nail polish in “Montezuma Red” that was made specifically for women Marines, as shown in this magazine advertisement that ran in fashion magazines of the time. Marine Corps History Division

Even without the Elizabeth Arden connection, the female reservists understood the importance of maintaining their appearance. Wearing cosmetics meant they were still properly feminine, and still within the conventional bounds of respectability. Hairstyle was also important. Regulation hairstyles required that hair not fall beyond the collar, so shorter, fashionable styles were encouraged. Beauty parlors were added to military installations so the women could maintain fashionable and regulation-compliant hairstyles, which sometimes required chemical processing, a concession to different social rules for men and women in the Marine Corps, despite organizational efforts to make them as similar as possible.

While the Marine Corps’ internal struggles over presentation were not visible to the public, the results were clear in the recruiting materials. The women were all attractive, wore delicate makeup that looked lightly applied, and had painted nails where the hands were visible and short, practical hair that was still stylish. The models were typically pretty women in a time when “pretty” meant girly and petite. Because of this clearly marketed preference for delicacy, internal memos indicate that, despite the need for men in combat, some male Marines had to remain in stateside assignments to handle the heavy lifting for the women.53

While Marine Corps WWII recruiting materials were consciously based on the Marines’ reputation as an elite outfit in the military, which was clearly visible in the men’s recruitment material, the message subtly shifted when applied to female-focused materials. The Women’s Reserve made this conceptual leap less daunting by playing on both the extant Marine Corps reputation as an elite organization and appealing to the viewer’s self-image as an exceptional individual. Deceptively simple, this strategy required careful balancing of respectability, tradition, and innovation, moving from “You’ll become a man” to “You’ll still be a woman.” That simple change in recruiting strategy not only drew highly sought-after women to the Marine Corps, it also helped reshape societies’ views on femininity, the military, the workplace, and the woman’s place in the United States.

• 1775 •

Endnotes

- In the face of a looming manpower shortage, President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed an executive order in late 1942 requiring that all branches accept draftees ages 18–35 under the Selective Service Act. Because the Corps’ status as an all-volunteer organization was key to their image as elite, exceptional, and selective, this requirement presented a challenge for the Marine Corps. Therefore, they took a two-pronged approach to their recruiting strategies during the period. One method was to accept and recruit 17-year-old volunteers who had parental permission to join. The other was to post Marine liaisons at induction centers to convince draftees to name the Corps as their preferred Service. As a result, approximately 90 percent of male recruits for World War II selected the Corps, a fact that the Public Relations Division used to support the im- age of the Marine Corps as an elite organization of volunteers. See Aaron B. O’Connell, Underdogs: The Making of the Modern Marine Corps (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2012), 30.

- Ibid., 7.

- David J. Ulbrich, Preparing for Victory: Thomas Holcomb and the Making of the Modern Marine Corps, 1936—1943 (Annapolis, MD: U.S. Naval Institute, 2011), 159.

- O’Connell, Underdogs, 27–28.

- Judith A. Bellafaire, The Women’s Army Corps: A Commemoration of World War II Service, CMH Publication 72-15 (Washington, DC: U.S. Army Center of Military History, undated).

- Col Mary V. Stremlow, Free a Marine to Fight: Women Marines in World War II (Washington, DC: Marine Corps Historical Center, 1993), 7. For more on the rumor campaign, fears of lesbians in the auxiliaries, and the sexualized attacks on women in the Armed Services, see Allan Bérubé, Coming Out Under Fire: The History of Gay Men and Women in World War II (Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 2010); MajGen Jeanne Holm, Women in the Military: An Unfinished Revolution, rev. ed. (Novato, CA: Presidio Press, 1992); D’Ann Campbell, Women at War with America: Private Lives in a Patriotic Era (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1984); and Marilyn E. Hegarty, Victory Girls, Khaki-Wackies, and Patriotutes: The Regulation of Female Sexuality during World War II (New York: NYU Press, 2007).

- U.S. Marine Corps Public Relations Division, “Public Relations Plan” (Marine Corps History Division, Women Marines, Reserves 1 of 3, Subsection Articles, undated), hereafter “Public Relations Plan.”

- John J. McGrath, The Other End of the Spear: The Tooth-to-Tail Ratio (T3R) in Modern Military Operations (Fort Leavenworth, KS: Combat Studies Institute Press, 2007), 11–24.

- For more information on women’s work roles during World War II, see Campbell, Women at War with America; Doris Weatherford, American Women in World War II: An Encyclopedia (New York: Routledge, 2010); Susan M. Hartmann, The Home Front and Beyond: American Women in the 1940s (Woodbridge, CT: Twayne Publishers, 1982); and Emily Yellin, Our Mother’s War: American Women at Home and at the Front during World War II (New York: Free Press, 2004).

- For more information on the gender-based changes in office work, see Carole Srole, Transcribing Class and Gender: Masculinity and Feminin- ity in Nineteenth-Century Courts and Offices (Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press, 2009). For more information on the history of women in the Navy and Marine Corps during World War I, see Jean Ebbert and Marie-Beth Hall, The First, The Few, The Forgotten: Navy and Marine Corps Women in World War I (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 2002). For more information on the history of women in the Army in World War I (the Hello Girls of the Signal Corps), see Dorothy and Carl J. Schneider, Into the Breach: American Women Overseas in World War I (New York: Viking Books, 1991); and Lettie Gavin, American Women in World War I: They Also Served (Denver: University Press of Colorado, 1997). The last women serving with the Marine Corps and Navy left service in 1922.

- Roosevelt authorized the creation of the Army, Navy, and Coast Guard women’s auxiliary/reserves. The Army’s female auxiliary members become known as the WAACs; their Navy counterparts become known as the WAVEs. For more information, see the Web site for the Department of Defense, “National Women’s History Month,” http://www.defense.gov/home/features/2015/0315_womens-history/.

- The WAAC’s official birthday was 15 May 1942. It was converted to Regular Army status, becoming the Women’s Army Corps (WAC) on 3 July 1943. See Bellafaire, The Women’s Army Corps at http://www.history.army.mil/brochures/WAC/WAC.HTM.

- The WAVES official birthday is 30 July 1942. For more information, see Jessica Meyers, “The Navy’s History of Making WAVES,” 30 July 2013,http://www.navy.mil/submit/display.asp?story_id=75662.

- The SPAR’s official birthday is 23 November 1942. The abbreviation for their name comes from their motto, Semper Paretis, Always Ready. PA2 Robin J. Thomson, The Coast Guard & The Women’s Reserve in World War II (Washington, DC: Coast Guard Historian’s Office, 1992), http:// www.uscg.mil/history/articles/SPARS.pdf.

- Approximately 400,000 women enlisted to support the wartime effort. For more information, see http://chnm.gmu.edu/courses/rr/s01/cw/students/leeann/historyandcollections/history/lrnmrewwii.html.

- Ulbrich, Preparing for Victory, 164.

- Enlisted women requirements included: U.S. citizenship, not married to a Marine, no children younger than 18 years of age, height of not less than 60 inches, weight of not less than 95 pounds, good vision and teeth, age between 18 and 35 years of age, and at least two years of high school. Officer candidates’ age range was between 20 and 49 years of age, but they must be a college graduate or have a combination of two years of college and two years of work experience.

- To meet enlistment quotas, many of the Services reduced their male enlistment standards, particularly by lowering the physical requirements for admission. On 16 April 1942, recruiting officers could grant waivers for slight deviations with respect to age, height, weight, character dis- charge from previous Service, and police records. Additional modifications were made on 24 August 1942 when the maximum age for recruits was raised from 33 to 36. For more information, see RAdm Julius Augustus Furer, “The United States Marine Corps: Origin, Legal Status, and Mission,” in Administration of the Navy Department in World War II (Washington, DC: Navy Department, 1959).

- The Women’s Reserve was activated several months after the other women’s auxiliaries, and therefore needed to prioritize its time and budget for maximum efficiency.

- “Public Relations Plan.”

- Strength Reports, Women Marines, Reports 1 of 5 (Washington, DC: Marine Corps University, History Division).

- Stremlow, Free a Marine to Fight, 2.

- For further information on women’s professional lives between World War I and World War II, see Virginia Nicholson, Singled Out: How Two Million British Women Survived Without Men After the First World War (Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 2008). For more on American women’s professional activities in the early 1940s, see Weatherford, American Women and World War II.

- Gender binary is the artificial division of the world into things that are “masculine” or “for men” and things that are “feminine” or “for women.”

- Judith Halberstam, Female Masculinity (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 1998), 23. Halberstam is the director of the Center for Feminist Research at the University of Southern California.

- Ruth Milkman, Gender at Work: The Dynamics of Job Segregation by Sex during World War II (Champaign: University of Illinois Press, 1987), 61–64.

- Ibid., 61.

- “USMCWR Recruiting Copy,” Women Marines, General Information 1 of 2, Subsection Press Releases (Washington, DC: Marine Corps History Division, undated), 12–14.

- Srole, Transcribing Class and Gender, 11–12.

- Milkman, Gender at Work, 15–19.

- Judith Butler, Gender Trouble: Feminism and the Subversion of Identity (New York: Routledge, 1987, 2006), 45.

- Ibid., 34–45.

- “WANT ACTION? Join U.S. Marine Corps!,” National Archives and Records Administration, Record Group 44-PA-70, World War II Posters.

- “1775 . . . 167th Anniversary . . . 1992,” National Archives and Records Administration, Record Group 44-PA-336, World War II Posters.

- “Semper Fidelis. U.S. Marine Corps,” National Archives and Records Administration, Record Group 44-PA-243, World War II Posters.

- The 18 April 1942 Doolittle Raid, named for LtCol James H. Doolittle, USAAF, represented the first U.S. attack on the Japanese home islands. The attack came in retaliation for Pearl Harbor, and had little military but high psychological significance.

- “Hit Hard and Often with the Marines,” National Archives and Records Administration, Record Group 44-PA-995, World War II Posters.

- “READY. Join U.S. Marines,” National Archives and Records Administration, Record Group 44-PA-1618, World War II Posters.

- “This Device on Headgear or Uniform Means U.S. Marines,” National Archives and Records Administration, Record Group 44-PA-2025, World War II Posters.

- “Always on the Alert,” National Archives and Records Administration, Record Group 44-PA-339, World War II Posters.

- Note that, even though our focus here is on the visual recruiting materials, the same concepts were highlighted in other formats, such as radio spots. The elite status of the Marine Corps was implied in much of the written material. Radio spots and advertisements directly connected the Women’s Reserve to the assaults on Tarawa and Guadalcanal, arguing that the victories, however difficult and costly, would have been impossible without the women Marines. Each radio spot and advertisement clearly explained the enlistment requirements for women. They clearly explained the process of becoming a Marine and emphasized that being a Marine would be difficult but worth the effort. Radio spots also emphasized the more feminine aspects of life as a woman reservist, and in all cases rested on the assumption that the women wanted to be changed by their experience but did not want to change too much. For more, see “March of the Women Marines” radio advertisements, Marine Corps University History Division, Women Marines, Enlistment–Enlistment, Training–Specialist Schools, and Assignments–Miscellaneous.

- “Public Relations Plan.”

- “Women Marines,” Life, 27 March 1944, 81–84.

- A variety of public relations tools were used in addition to the posters. The few posters produced were placed prominently around town, just as were the men’s posters. The women’s procurement officers also provided car and window placards for display. Brochures were often distributed at meetings of local women’s groups and clubs. Procurement officers were guest speakers, though the preferred speaker was a local woman reservist. The meetings and recruitment events were announced and covered in local newspapers. Some women who attended the meetings were sworn in there, and the photos of their swearing-in became future promotional material for the area. See “Public Relations Plan.”

- Stremlow, Free a Marine to Fight, 3–4. Planes were often featured prominently in recruiting imagery, and ultimately, about 50 percent of women reservists worked in aviation in some capacity. This statistic came from an untitled radio address given by MajGen Field Harris, director of Marine Aviation, for the MCWR’s second anniversary in 1945.

- Streeter’s motherhood was both acknowledged and celebrated, and it was often presented as proof that the young women would be well cared for while in the Marines. The idea that the women would be properly chaperoned and their reputations would be untarnished by their service was important in the recruiting effort, and something that set the Women’s Reserve apart from both the men and the other women’s Services. Stremlow, Free a Marine to Fight, 7.

- USMCWR Recruiting Copy, 4.

- World War II Recruiting Center Window Placard, Women Marines Publications (3 of 3) (Quantico, VA: Marine Corps University, History Division, undated).

- Second Anniversary Recruiting Placard, Women Marines Publications (3 of 3) (Quantico, VA: Marine Corps University, History Division, undated). A photo is unavailable, as the original placard is damaged.

- The shoes were practical but still fashionable, the pocketbook came with a removable slipcover, and the flashes of red on the “forestry green” uniform were mentioned repeatedly in press releases and news articles. Wearing makeup, including nail polish, was encouraged as a method of feminine expression.

- See Stremlow, Free a Marine to Fight, 19; Lindy Woodhead, War Paint: Madame Helena Rubinstein & Miss Elizabeth Arden: Their Lives, Their Times, Their Rivalry (Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley and Sons, 2003), 287–88; and Elizabeth Arden advertisement, Women Marines–Wars (1 of 2), Subsection Articles (Quantico, VA: Marine Corps University, History Division, undated).

- Woodhead, War Paint, 287.

- Marine Corps Women’s Reserve General Policies, Women Marines–Wars (1 of 2), Subsection Regulations (Quantico, VA: Marine Corps University, History Division, 25 November 1943); and Monthly Report from Assistant for Women’s Reserve, Camp Lejeune, North Carolina, Survey of Distribution of MCWR Personnel, Camp Lejeune, as of 1 May 1944, Women Marines–Assignments, Subsection–Locations (Quantico, VA: Marine Corps University, History Division).