PRINTER FRIENDLY PDF

EPUB

AUDIOBOOK

Abstract: To undermine U.S. military strength, state actors are increasingly operating in the ambiguous environment between peace and war known as the “gray zone.” These actions test U.S. response by exploiting the West’s rigid notion of conflict. Soviet actions toward the United States and other nations during the Cold War shared many similarities with contemporary Russian strategy. There is no current uniform definition of the gray zone, and the United States has not developed doctrine to address this challenge. Russia has adapted Soviet Cold War techniques for the digital and globalized age and effectively integrates instruments of power against the United States by targeting seams within culture, maintaining ambiguity, and controlling narratives. Countering these tactics requires that the United States modify its mindset toward conflict and improve integration of its own instruments of power.

Keywords: gray zone, Russia, Cold War, political warfare, active measures, hybrid warfare

Introduction

Subversion, utilization of unmarked military forces, foreign interference, and other methods designed to influence policy have long been tactics of many state actors. Russia has employed several iterations of these methods both during and after the Cold War to influence perception and undermine the strengths of adversarial governments. Since the conclusion of the Cold War, advances in technology, globalization, and other factors have contributed to a widening gap between war and peace. The speed at which information now moves limits decision space for leaders, resulting in inadequate responses that open new channels for adversaries looking to capitalize on diminished status while increasing their own influence. Intensified economic interdependence caused by globalization has created new competition for resources in markets where reputation is an increasingly important asset.

As the character of warfare continues to transform, the United States must formulate doctrine to counter these tactics and determine how success is measured. These tactics occur in what is currently known as the “gray zone,” the space on the spectrum of conflict between war and peace. By blurring the distinction between the two and fostering uncertainty, states can exploit the West’s concept of war and peace as mutually exclusive. Russia’s 2014 annexation of Crimea showcased how an irredentist power could manipulate this perceived distinction to its advantage, couple this manipulation with hybrid warfare, and create a pretense resulting in gained territory with few shots fired. Russia used similar tactics prior to its invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, blaming its western neighbor for increasing tensions via “Russophobia” and the need to “de-Nazify” as justification for action.

These actions continue to raise numerous questions concerning the nature of conflict. Is the gray zone concept worthy of its own place on the spectrum of conflict or merely a contrived term for a continuing evolution in strategy? How might the United States respond to these actions in the absence of current gray zone doctrine in an environment where elements of operational and strategic warfare are rapidly converging?

The Contemporary Gray Zone

Owing to the complexity, evolving characteristics, and nebulous nature of the gray zone, attempts to formulate both doctrine and potential countermeasures lack specificity and purpose. Some argue that America is organizationally and psychologically unprepared for unrestricted warfare and has a strategic culture that make it temperamentally unsuited to fighting gray zone conflicts.1 With adversaries using a wide-ranging array of tools to undermine governmental legitimacy, there is a tendency to view these actions as ad hoc rather than as individual elements of an overarching strategy.2 Many military strategists argue that this unconventional environment calls for an equally unconventional approach that maximizes strategic and operational flexibility across the spectrum of conflict.3 Indeed, a problem at the outset concerning potential responses is the continued view of the gray zone as an area of conflict. The gray zone should be categorized appropriately as an operational environment. The Department of Defense Dictionary of Military and Associated Terms, Joint Publication (JP) 1-02, definition of operational environment provides a useful framework for construction; it includes a composite of conditions, circumstances, and influences that affect the employment of capabilities.4 Treating the gray zone as an operational environment allows greater military flexibility for response while also shifting focus away from the military as the only suitable instrument of national power.

Some argue that the United States already has a marked advantage in mitigating gray zone competition based on four factors: constitutional tenets, the character of American civil society, alliances and partnerships, and the capacity of the U.S. government.5 Leveraging these assets with specificity, improving intelligence warning, and adopting a campaign mindset will help to proactively shape conditions in America’s favor.6

Recommendations concerning doctrine and responses to gray zone activities are often couched in generalities or address only the adversary’s tool kit. U.S. statecraft, economic policy, and information operations are rarely covered as options for both defense and counteraction. Additionally, success in the gray zone is undefined. Synthesizing current doctrinal recommendations will help to provide measures for success and better define winning.

Defining the Gray Zone

The scope of behaviors used to describe so-called gray zone activities is consistently becoming broader as the opportunities for exploitation and boundary testing by adversaries increase. New technology, changing leadership, and an ever-shrinking connected world ensure that defining the gray zone will remain a moving target. While analysts agree on general characteristics, such as aim and methods, none have provided a comprehensive comparative study to better shape a present-day definition.

Although the term did not become popular until 2015, the concept of the gray zone strategy has existed for centuries. Carl von Clausewitz identified in On War that conflict is complex and limitless in its variety.7 He also recognized a key challenge in what would become gray zone strategy in describing uncertainty regarding adversary intent.8 This element, often referred to as the “fog of war,” is easily applied to gray zone theory when those actions are viewed as part of a larger campaign.

George F. Kennan, in his most well-known 1948 memorandum, described Russia’s own form of gray zone strategy, “political warfare.”9 Kennan defined political warfare as “the employment of all the means at a nation’s command, short of war, to achieve its national objectives.”10 It included overt measures such as “white” (overt) propaganda, political alliances, and economic programs, to “such covert operations as clandestine support of ‘friendly’ foreign elements, ‘black’ psychological warfare, and even encouragement of underground resistance in hostile states.”11 Countering organized political warfare served as the basis for U.S. foreign policy during the Cold War years and continued for part of President Ronald Reagan’s tenure.12 U.S. Army general Joseph L. Votel would later bridge the parallels between current gray zone activities and Kennan’s political warfare of the Cold War era.13

Frank G. Hoffman, a retired Marine and research fellow at the Center for Emerging Threats and Opportunities and a prolific writer on national security strategy, recognized a trend in both state and nonstate actors of blending multiple forms of warfare in 2007.14 He coined the challenge presented by this convergence a hybrid threat, a term sometimes used synonymously with gray zone conflict today.15 Using Hezbollah as a model, Hoffman illustrated how nonstate actors can exploit Western weaknesses and how this strategy is being disseminated to other state and nonstate actors.16 Hoffman predicted that future opponents would set engagements away from the preferred U.S. fighting style, avoid predictability, and seek unexpected advantages to accomplish their objectives.17

The contemporary conceptualization of a gray zone arose in 2014 with Nadia Schadlow’s War on the Rocks article describing a space between peace and war on the spectrum of conflict.18 She characterized this space as churning with political, economic, and security competitions that require constant attention, while lamenting American reliance on the military as an instrument of first resort.19 She noted that policy considerations rarely made a military-political connection, and as a result, there was no U.S. presence in this space between.20 Schadlow presciently explained that because adversaries cannot match American military power, their operations would occur in other more permissible domains.21

The astonishing Russian annexation of Crimea and its actions in Ukraine in 2014 produced a torrent of analysis and opinion, most postulating that the world was experiencing a new form of warfare.22 Analysts further exacerbated this notion by unearthing a 2013 speech by Russian chief of general staff Valery Gerasimov. The speech, delivered at the Russian Military Academy of Sciences, published in an obscure Russian outlet and initially ignored by both the Kremlin and the U.S. intelligence community, provided validation to Russia watchers since it provided a salient link between emerging trends in modern conflicts and overall Russian strategy.23

The Gerasimov “Doctrine”

Gerasimov’s 2013 speech at the Russian Military Academy of Sciences was published in the Military-Industrial Courier, a relatively obscure publication with limited readership. The title of the article, “The Value of Science Is Foresight” is significant because in the Russian lexicon, “foresight” has a specific military contextual meaning that equates to future war. The circumstances surrounding Crimea’s annexation created a thirst for analysis and produced a flurry of commentary. One of these contributors was Mark Galeotti, an expert on Russian security affairs. He published a piece in his In Moscow’s Shadows blog titled, “The ‘Gerasimov Doctrine’,” which he would later explain was completely tongue-in-cheek. However, the timing and need to provide a connection between Crimea, the situation in the Donbas, and current military thought gave this “doctrine” momentum, which still unfortunately propels it through many analytical and media channels.24

The first official use of the term gray zone as an item of interest was during a 2015 House Armed Services Committee meeting in which General Joseph Votel, commander of U.S. Special Operations Command, characterized gray zone activities as designed to secure an objective while minimizing the scope and scale of actual fighting.25 Gray zone activities are “characterized by intense political, economic, informational, and military competition more fervent in nature than normal steady-state diplomacy, yet short of conventional war.”26 He posited that it was best employed where traditional statecraft was inadequate or ineffective and large-scale conventional military options are not suitable or deemed inappropriate for a variety of reasons.27

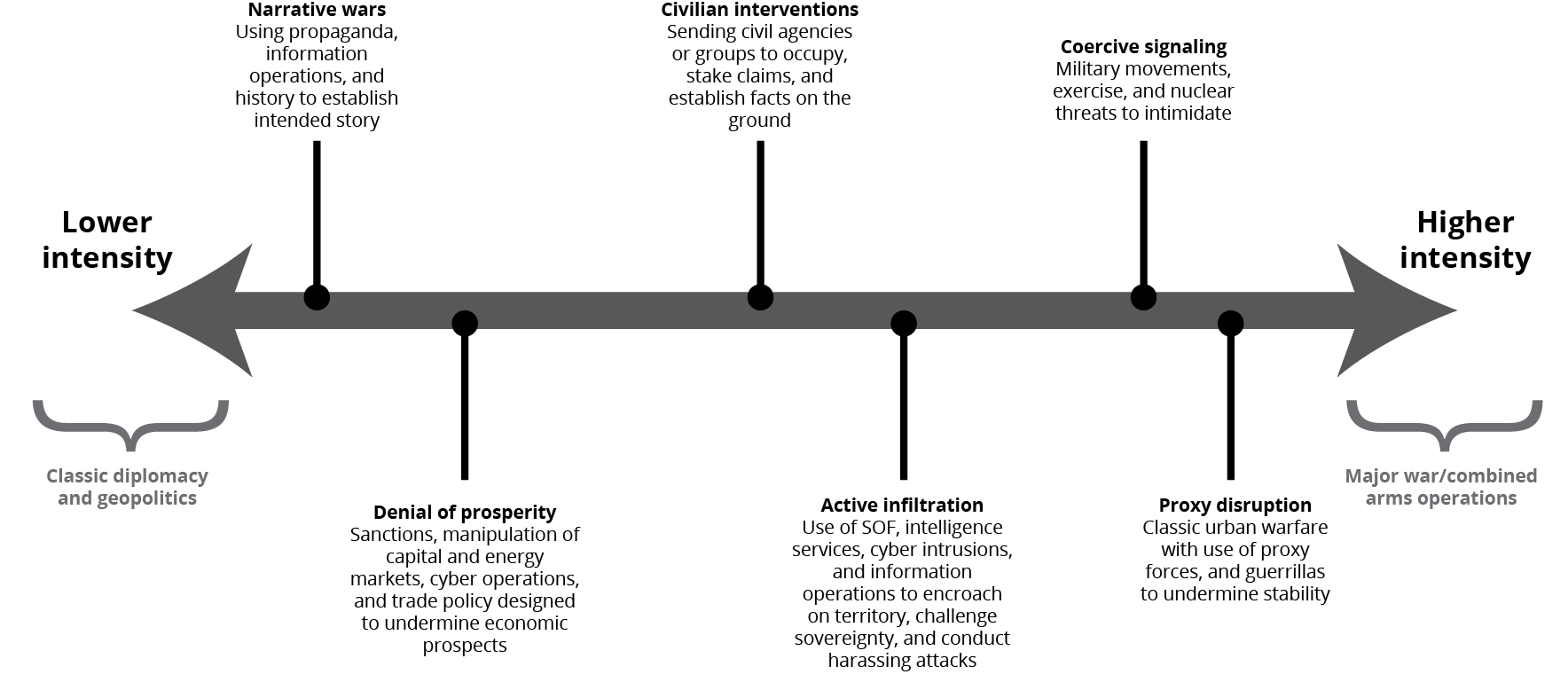

Michael J. Mazarr’s December 2015 Strategic Studies Institute report provides the most useful depiction of gray zone conflicts and the intent behind their use. In Mastering the Gray Zone, Mazarr performs a comparative analysis of past terminologies to include political, hybrid, and unconventional warfare.28 More importantly, Mazarr injects two additional characteristics for consideration: the revisionist tendencies of the actor (moderate but not radical) and the use of civilian instruments to achieve military objectives.29

Figure 1. Mazarr’s gray zone spectrum

Source: Michael Mazarr, Mastering the Gray Zone: Understanding a Changing Era of Conflict (Carlisle, PA: Strategic Studies Institute, U.S. Army War College, 2015), 60.

Adam Elkus presents another view of gray zone theory in his December 2015 critique.30 He argues that the terminology is incoherent in that it has been expanded to encapsulate too broad a range of activity.31 He contends that the gray zone is a new terminology for already existing military strategy and political science: limited wars and compellence, which have all unnecessarily been lumped together.32 He sees gray zone theory as a meaningless effort to identify a problem that has already been solved.33 Elkus’s take on the nature of the gray zone is highly constructive in that he has recognized the inconsistent nature of the concept in its relative infancy, and that if something means everything, it means nothing. However, Elkus’s critique misconstrues limited war by implying that anything less than total war is within the current confines of the mainline gray zone definition. Historically, limited war has meant a state using less than its total resources to achieve victory. The Falklands and Gulf Wars are examples of conflict that fit into this concept—certainly not within the confines of gray zone strategy.

Figure 2. Elkus’s view of the gray zone

Source: Adam Elkus, “Abandon All Hope, Ye Who Enter Here: You Cannot Save the Gray Zone Concept,” War on the Rocks, 30 December 2015.

The treatment of the gray zone as defined by the Department of Defense’s (DOD) Strategic Multilayer Assessment forum in 2016 as a “conceptual space” is helpful toward operationalizing the term as a battlespace or environment.34 However, there are two issues present when placed into the Russian context: First, large-scale military conflict is a relative term. Second, not all gray zone strategy threatens solely U.S. interests.

The Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) definition comprises many of the common elements put forward to this point but narrows the scope of actor objectives to those of security and therefore does not capture activity that may likely later be categorized within the gray zone.35 Additionally, the CSIS definition has no mention of ambiguity—a paramount characteristic here, referring only to avoidance of direct force. Like the DOD forum’s issue, the use of size is relative and may indicate a range of force structures.

In 2020, Donald Stoker and Craig Whiteside argued that the adoption of the gray zone and gray zone conflict represent a failure in American thinking.36 They contend outright that the gray zone and its related terms should be eliminated from our current glossary as they serve only to confuse an issue by muddying its parameters.37 To prevent the premature release of new terms, they suggest testing that term against history and existing theory to validate whether it is actually new and worthy of consideration.38 They identify four problems with the concept of the gray zone and hybrid war: first, that they are poorly constructed theories; second, that they distort or ignore history; third, that they feed a tendency to confuse war and peace; and fourth, that they undermine strategic thinking as foundations for new guidance.39

Common Ground and Valid Objections

How then should one proceed in defining gray zone strategy? Is it rightly classified as warfare? Are its myriad critiques justified? Which definition provides the most utility? Recent history has provided no shortage of material for consideration.

Hybrid warfare and hybrid threat are distinguishable from gray zone conflict. While gray zone activities may rely entirely upon unconventional or covert military techniques at all levels, hybrid warfare often contains a congruence with conventional military assets, is limited to only tactical and operational echelons, and is punctuated by explicitly sanctioned violent tactics.40 Operations, Army Doctrinal Publication 3-0, describes hybrid threat as

the diverse and dynamic combination of regular forces, irregular forces, terrorist forces, criminal elements, or a combination of these forces and elements all unified to achieve mutually benefitting effects. Hybrid threats combine traditional forces governed by law, military tradition, and custom with unregulated forces that act without constraints on the use of violence.41

Additionally, as Michael Mazarr argues, hybrid warfare is truly “war” in the Clausewitzian sense, whereas gray zone strategies are less violent and a looser form of conflict.42 Moreover, the term hybrid threat in this context does not align with military doctrinal understanding and serves only to further confuse since not all gray zone activity contain mixed forces. Finally, the hybrid characterization has limited analytical utility since it indicates a mix of elements and nothing more.43

To reduce confusion on the characterization of the gray zone and distance discussion from tactical concepts, its “warfare” surname should be dropped in favor of “conflict.” This better aligns with Hoffman’s argument on imprecision, since warfare typically connotes some type of targeted violence, a trait not always consistent within the gray zone. This will also help future proof against any arising redundancies or oxymorons.

The Department of Defense Dictionary of Military and Associated Terms defines an operational environment as a “composite of the conditions, circumstances, and influences that affect the employment of capabilities and bear on the decisions of the commander.”44 Operational Environment and Army Learning, Training Circular (TC) 7-102, further elaborates on complex operational environments and describes the interplay between expectations, perceptions, influences, and ambiguity.45 These drivers play directly into gray zone strategy, resulting in its characterization as an operational environment. Additionally, classification as an operational environment, as opposed to forcing it into irregular, hybrid, or unconventional terms will assist military planners in constructing estimates and forecasting effects at the strategic level. In that same vein, “multiple instruments of power” carries a strategic connotation, facilitating longer-range thought and consideration at higher echelons. Descriptors of increased fervency and staying short of the threshold of conventional war are retained as they represent the core attributes of gray zone conflict. Exploitation of ambiguity captures several domains (legal, geographical, intent, and attribution).

A Suggested Definition

The 10 leading definitions can be distilled into the following common elements:

- Uses nontraditional statecraft, unconventional methods, or multiple elements of power

- Remains below the threshold of conventional war

- More fervent than steady-state competition

- Ambiguous in intent or attributability

- Involve some form of coercion or aggression

- Pursues objectives

- Gradual

- Threatens U.S. interests by challenging, undermining, or violating international customs, norms, or laws

Regardless of the current critique of the gray zone as an in-vogue phrase, the term has positioned itself firmly within both the strategic and military lexicon and for the moment looks to be here to stay. The table below illustrates the several shared touchpoints among the varied definitions.

The gray zone should be defined as an operational environment in which actors use multiple instruments of power to pursue political-security objectives through graduated activities that are more fervent than steady-state competition, exploit ambiguity, and fall below the threshold of conventional war.

Which activities adequately fall within the gray zone as contrasted with historic versions of Soviet strategy? The overall aims, tactics, and outcomes of Soviet Cold War practices have arguably not changed significantly during the past 50 years. While subversion, misinformation, and its various other forms remain consistent, albeit enabled exponentially by technology, a few Russian actions stand as outliers when contrasted to the last half century. These anomalies may be better characterized as hybrid warfare rather than as gray zone strategy.

Table 1. Gray zone elements and variations

|

|

Hoffman

(2014)

|

Votel

(2015)

|

Barno & Bensahel

(2015)

|

Mazarr

(2015)

|

Kapusta

(2015)

|

Brands

(2016)

|

DOD

(2016)

|

NIC

(2016)

|

CSIS

(2017)

|

Rand

(2019)

|

|

Nontraditional statecraft/unconventional methods/multiple elements of power

|

X

|

X

|

X

|

X

|

|

|

X

|

X

|

|

|

|

Below threshold of conventional war

|

X

|

X

|

|

X

|

X

|

X

|

X

|

X

|

X

|

X

|

|

More fervent than steady-state competition

|

|

X

|

|

|

|

|

X

|

X

|

X

|

X

|

|

Ambiguous

|

|

|

X

|

|

X

|

X

|

X

|

|

|

X

|

|

Coercion/aggression

|

X

|

X

|

X

|

X

|

X

|

X

|

X

|

X

|

X

|

X

|

|

Pursues objectives

|

X

|

X

|

X

|

X

|

X

|

X

|

X

|

X

|

X

|

X

|

|

Gradual

|

X

|

|

|

X

|

|

X

|

|

|

|

|

|

Threatens U.S. interests by undermining international rules

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

X

|

|

|

|

Sources: Frank G. Hoffman, Conflict in the 21st Century: The Rise of Hybrid Wars (Arlington, VA: Potomac Institute for Policy Studies, 2007); Votel, “Statement before the House Armed Services Committee Subcommittee on Emerging Threats and Capabilities”; David Barno and Nora Bensahel, “Fighting and Winning in the ‘Gray Zone’,” War on the Rocks, 19 May 2015; Mazarr, Mastering the Gray Zone; Kapusta, The Gray Zone; Brands, “Paradoxes of the Gray Zone”; Popp and Canna, The Characterization and Conditions of the Gray Zone; “Foreign Approaches to Gray Zone Conflicts,” PowerPoint, National Intelligence Council, 2016; Green et al., Countering Coercion in Maritime Asia; and Morris et al., Gaining Competitive Advantage in the Gray Zone.

Russian Approaches Over Time

There is a tremendous cultural and historical gap between the USSR and the West. An analyst trying to understand the mentality of the Soviet leaders or their approach to or perception of problems is seriously handicapped without some background in Soviet history.

~ Robert Gates, 197646

Russia’s gray zone approach is based fundamentally on Soviet techniques.47 The approach used depends largely on the targeted adversary, but all approaches are typically rooted in a full-spectrum methodology.48 One of the most commonly applied practices against the United States during the Cold War and today is active measures, which finds its heritage in the Bolshevik October Revolution of 1917.49 Lenin’s fear of ideological subversion had an enormous impact on the way in which narratives were controlled to stabilize Communism.50 Soviet propagandist Ivan Philipovich Ivanov later confirmed that the 1930s variation on active measures was the best enabler for socialism and guaranteed against the restoration of capitalism.51 Seeing success in shaping internal influence and perceived protections via external projection, the Soviets imparted a holistic view and incorporated active measures into allied and foreign policy as well.52 The intelligence services that conduct these practices represent an integral function of Russian legislation and are based on a long tradition.53 Indeed, the Red Army’s Officer’s Handbook expressed concern over a weakening of socialist ideals via external anti-Communist propaganda.54 This policy continues today as Russia views itself as constantly beset by U.S. information warfare that threatens its ideology.55

Although technologies have evolved and globalization has curtailed the distance between the two countries, Russian meddling in U.S. affairs is not unusual or new.56 Russia’s talent for propaganda and disinformation have long been recognized and continue to improve, even after the Cold War. Russia regularly employs an integrated and seemingly whole-of-government approach to achieve its national objectives. In his 1948 cable, George Kennan noted that Lenin’s synthesis of the teachings of Karl Marx and Carl von Clausewitz have made Russia the most refined purveyor of political warfare in history.57

The term active measures encompasses a broad range of activities used by Russian intelligence agencies for a multitude of purposes.58 In the past, these activities have included disinformation operations, political influence efforts, and the activities of Soviet front groups and foreign Communist parties.59 Russia’s recent gray zone activities in Europe have consisted primarily of disinformation campaigns intended to undermine political institutions.60 They also include deception, espionage, destabilization, and sabotage. The end state of each effort is to bolster the image of the Russian government, tarnish the reputation of a foreign government, or sow discord among the populace of an adversary or between nations. The span of operations can be wide or narrow, solitary, or conducted under friendly pretense with other intelligence organizations.

Owing to its versatility, the definition of “active measures” has proven difficult to pin down; indeed, the term is merely the translation of a phrase borrowed from the Russian intelligence community.61 World War II psychological operations provide the closest parallel to today’s active measures. One former Committee for State Security (KGB) official’s description of active measures as the “heart and soul of Soviet intelligence” illustrates both the historic importance of and reliance on the tactic as well as reflecting Russia’s permanent wartime mentality and strategic culture.62 Active measure campaigns represent the gray area between military campaigns and white propaganda, key terrain in today’s information landscape.63

Disinformation was an essential part of the Kremlin’s non-nuclear arsenal against the West during the Cold War, with Soviet operatives spending at least one-quarter of their time employing active measures.64 The Soviet-East German Operation Infektion from 1983 to 1989 attempted to pin the origination and spread of HIV on the United States.65 Various media outlets tailored stories based on geographical or ethnic characteristics, and although now far-removed from recent memory, these narratives have had a lasting impact.66 In a 2013 study, almost 60 percent of African Americans surveyed subscribed to one of several conspiracy beliefs regarding origination of HIV, which included the targeting of Blacks.67 How much of that percentage was directly affected by the KGB and Hauptverwaltung für Aufklärung (HVA) may never be known, but as one researcher observed, conspiracy theories circulate geographically with astonishing ease, serving as templates readily adapted to the charged social divisions and power inequalities of their latest homes.68

Post–Cold War Evolution?

Various documents, doctrinal adoptions, and new leadership in the 1990s surprisingly provided consistency in Russian strategy rather than change. In 1995, instructors at the Russian General Staff Academy offered their definition of information warfare as

a means of resolving conflict between opposing sides. The goal is for one side to gain and hold information advantage over the other. This is achieved by exerting a specific information/psychological and information/technical influence on a nation’s decision-making system, as well as by defeating the enemy’s control system and his information resource structures with the help of additional means, such as nuclear assets, weapons, and electronic assets.69

After taking power in 2000, Vladimir Putin described the importance of a long-term strategy for development and combatting threats.70 This strategy partially coalesced in Russia’s 2000 National Security Concept, which underlined the importance of information as both a commodity and sphere.71 The security concept also echoed the Soviet-era informational threat of countries attempting to subvert Russian ideology.72 In April 2000, Putin broadened his definition of threats to states that infringed or ignored Russia’s interests in “resolving international security problems” or stymied Russian attempts to influence the world order.73 Later iterations have perpetuated this ideation, describing foreign media outlets’ inherent bias toward Russia, the use of psychological tools to destabilize internal political and social situations, and erode “traditional spiritual and moral values.”74 This continued narrative reinforces Russia’s worldview of persistent vulnerability and geopolitical insecurity as a driver for their actions.75

Events in 2007 marked a Russian attempt to reestablish itself as a regional influencer. In February, President Putin indicated during a speech in Munich that Russia would no longer accept the U.S.-led unipolar model of international relations and that Russia would implement its own independent foreign policy in pursuit of its geopolitical interests.76 Shortly after Munich, Putin appointed Anatoly Serdyukov as Russia’s minister of defence. Serdyukov, a former tax minister, was tasked with increasing efficiency in the Russian military. Overall forces were downsized, but Russia’s foreign intelligence services saw their funding restored to Cold War levels, signaling a shift in Russia’s offensive strategy and placing a higher emphasis on information operations.77 It also effectively indicated that active measures were being revived as a central component of Russian strategy.78

In April 2007, Russia began an information campaign intended to drive a wedge between the ethnic Russian population of former Soviet Bloc states and their governments.79 Social media efforts and cyberattacks allowed the Kremlin to leverage Russian-identifying populations and incite unrest.80 This campaign showcased a cost-effective method of near abroad influence and disruption, causing varying levels of unease in several Baltic and Slavic states.81

Russian military weaknesses were highlighted in its 2008 war with Georgia. Although it was able to take control of Abkhazia and South Ossetia, obsolete equipment, poor command, control, communications, computers, intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance and lack of diverse military capability instigated reforms that would take place into the mid-2010s.82 Russian military doctrine in 2010 described integrated military and nonmilitary means as a characteristic of modern military conflicts, creating an additional subset within the current understanding of gray zone conflict.83 Defence Minister Serduykov and his First Deputy Minister of Defence Nikolay Makarov were replaced by Sergei Shoigu and Valery Gerasimov, respectively. Gerasimov would later become the poster child of Russia’s alleged hybrid war approach.

In 2013, Shoigu opened recruiting to new “military science units” that emphasized cyber operations, electronic warfare, and signals intelligence.84 A new breed of hackers flowed into the GRU (formerly the Main Intelligence Directorate, the GRU is the foreign military intelligence agency of the General Staff of the Armed Forces of the Russian Federation), and the organization established itself as an aggressive and risk tolerant arm of Russian intelligence.85 Cyberattacks provided a new means for asymmetric tactics while updated communication technology offered a new venue for propaganda.86

The 2014 annexation of Crimea validated perceptions that Russia was using a new type of hybrid warfare utilizing multiple domains to impose its will. Russia’s extensive clandestine disinformation campaign discredited the Ukrainian government and provided a calculated pretense for employment of military forces. Outwardly, the Russian government framed the issue as one of reunification and magnanimous protectionism, garnering the support of many in Crimea. Simultaneously, Russia covertly undermined the government with disingenuous and inflammatory reporting. Both ultimately softened the blow of any perceived illegal activity in the region. The event also showcased the power of social media in controlling the narrative and a sinister progression from ambiguity to fait accompli. How can the West effectively disrupt these tactics?

Constructing Doctrine

There is no such thing as a former KGB man.

~ Vladimir Putin, 200687

The final report of the organization responsible for countering Soviet disinformation from 1981 to 1992 contained a pertinent admonishment to future analysts and policy makers. Initially established under the State Department and later falling under the United States Information Agency (USIA), the Active Measures Working Group (AMWG) warned that even though the Soviet Union had collapsed, active measures would still be a threat to U.S. interests due to various anti-American groups adopting their previous rival’s strategy.88 The group also initially identified that Russia had not discarded much of its Soviet gray zone approach, noting that many elements of their active measures apparatus continued to operate, just under new names.89

Many Russian leaders today were professionally trained by the Soviet state. President Putin has surrounded himself with like-minded individuals and there are few people at the top levels of Russian government that did not grow up in the Soviet intelligence apparatus.90 Contemporary Russian gray zone tactics against the West mix previous Soviet tactics with analysis of adversary strategy, enabling a tailored application of practices.91 The perception that this brand of conflict is new is a misstep that shows how successful these tactics are.92 A second misstep is the perception of activity as ad hoc rather than as part of a long-term strategy, with Russian actions tending to startle the West even after intentions have been made clear.93

Understanding Russian strategy drivers is essential to formulating gray zone policy. Since the early 2000s, Russia has perceived a growing instability in the world order favoring a shift from West to East.94 Moscow believes that competition for markets, trade routes and resources, and its reemergence as a world power will depend largely on global perception.95 This view, coupled with Russia’s fortification against Western ideology and a zero-sum mentality presents a complicated mosaic of motivations leaning toward a defense through offense bent. A blurring between offense and defensive actions will hinder U.S. deterrence as Moscow pursues external interests in the name of national security.96

Gray zone conflict also severely challenges America’s conventional military and analytical thinking in several ways. It relies on creating a narrative contrary to U.S. interests and demonstrates the ineffectiveness of existing tools by undermining traditional measures of conflict. The Western security construct on warfare is an inadequate framework for understanding Russian strategic thought.97 In hybrid warfare situations like Crimea, ideations of war and peace as mutually exclusive hinder the ability to respond and adapt to a decades-old strategy that uses ambiguity as a shield. Additionally, there are few international institutions that can effectively respond to gray zone conflict or low-intensity hybrid warfare.98 Take, for example, the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO), where every alliance member must agree to enact Article V protections in an environment that lends itself quite handily to deniability. There is no gray zone for Russia, since it considers itself in a constant state of conflict with no distinction between war and peace. Russia’s strength flows from its ability to integrate various instruments of power and its ability to effectively identify weaknesses in adversaries.

As CSIS observes, the United States is being confronted with the liabilities of its strengths.99 The U.S. tendency to see the military as the sole hammer of national power overshadows the potential of other tools, especially when every problem is viewed as a nail. A prime illustration of this mentality is displayed in the U.S. military’s doctrine as published in Doctrine for the Armed Forces of the United States, JP 1. Warfare is described as either traditional or irregular, and although the publication admits that it can be a combination of both, irregular warfare includes only those struggles that are “violent.”100 Nathan Freier notes that these actions serve as a “menace to convention” that achieve outcomes typically reserved for war.101

Similarly, Joint Planning, JP 5-0, provides a phasing construct that is inadequate for current issues. Of the six phases delineated in Joint planning doctrine, all are placed into stringent sequential categories that shackle planners by creating arbitrary parameters and blinders.102 Russian gray zone activities operate in a steady state and sometimes occur gradually with no clear delineation or attribution, resulting in a frustration of the planning process and desyncing expectation and response. This also presents a problem within the highest levels of U.S. policy. Steven Metz, professor of national security and strategy at the U.S. Army War College, believes that Washington’s tendency to compartmentalize elements of power and apply them in sequence shows our weaknesses toward ambiguity and inclination toward restricting conflict.103 Nowhere is this compartmentalization more apparent than in U.S dependence on the Special Operations Forces (SOF) community as a tool in irregular warfare. Caught between poor delineations of conflict and its historic role in nonpermissive environments, SOF consistently serves as default for any employments considered short of war. This, and other tendencies within U.S. strategic culture, display U.S. organizational and psychological unpreparedness to counter gray zone conflict.104

In the last few years, the United States has started to understand how gray zone competitors operate.105 Although the United States possesses near unlimited capability to compete in the gray zone, there is no plan to effectively integrate its capabilities to achieve its objectives.106 Its challenge will not lie in developing capability, but in developing a national security strategy appropriate to an era of mixed and paradoxical trends.107 Formulating strategies, options, and counters to gray zone activities will be crucial as they become more frequent and complex.108

In the information domain, the impacts of Russian disinformation campaigns on the U.S. intelligence community have been increased scrutiny, organizational and mission adjustments, and a new focus on cyber operations. Increased scrutiny has come as a by-product largely due to perceived Russian influence in the 2016 election and the U.S. intelligence community’s inability to prevent or counter the activity. The United States has improved the means of monitoring information but has developed no standard procedures for response. Complicating the situation, social media exists in a purgatory moving between platform and publisher and is not subject to the many regulations that outright media outlets must obey. Even so, popular social media outlets’ attempts to self-regulate are met with suspicion.109

Russian action has obliged organizational and mission adjustments as well as a new concentration on cyber operations in recent years. Russia is outpacing the United States by leveraging the information space to bolster its propaganda, messaging, and disinformation capabilities in support of geopolitical objectives.110 The U.S. intelligence community has had to reexamine potential threat avenues, increase defensive cyber capabilities, and work harder to ensure that the correct version of information is available.

Responses to disinformation necessitate a delicate balancing act. Should the intelligence community address applicable reporting as false and set the record straight—but at the same time risk dignifying a forgery—or do nothing and hope that the populace will critically view the information? Another dilemma in truthful reporting is exemplified by the Robert S. Mueller report and other redacted reports concerning Russian influence operations: confirm or deny involvement at the risk of revealing sources and methods or remain silent and again hope that the truth sorts itself out.111 Concerning response to disinformation, Charles Wick, director of the United States Information Agency, observed in 1988 that “the United States has the tremendous advantage that the truth is inherently more powerful than lies . . . [b]ut if the lies go unchallenged, then they can have a damaging effect.”112 While addressing gray zone challenges requires looking forward, it also requires looking back to a period where actions regularly fell under the traditional notion of war.113 During the final years of the Cold War, exposing acts of disinformation served as an extremely powerful tool in undermining Soviet strategy.114

The rapid and intensive release of U.S. intelligence during Russia’s military buildup along the Ukrainian border in late 2021 helped to shape the international narrative and frustrate Russian plans. This “prebunking,” or inoculating the public against disinformation by purposefully spreading intelligence, narrowed any potential avenues for denial on the part of the Russian government, expedited United Nations sanctions, and helped set conditions for a near global rally in Ukraine’s favor. Increased intelligence sharing has also worked to stymie false flag actions, most recently Shoigu’s November 2022 attempt to establish a pretext for escalation by implicating Ukraine in a dirty bomb scheme.115

Recommendations

The ambiguous nature of gray zone conflict presents the biggest challenge to the U.S. mindset. Hesitancy in attribution prevents any meaningful response, while misinformation runs nearly roughshod throughout social media and other outlets with no repercussion or appreciable cost to its fabricators. Russia watchers fixate on purported military doctrine while overlooking the importance of information in strategy.116 Understanding that the KGB stratagems in active measures still endure in today’s gray zone conflict is key in developing responses.117 The West has difficulty in identifying information-based stratagems due to our tendency to oversimplify Russian intentions as aggressive and only short term.118 The United States must reshape its intellectual, organizational, and institutional models to enable better understanding and response options to Russian gray zone activities.119 U.S. strategy must assume that there are no fixed rules in gray zone conflict and that actors will utilize a wide swath of activities to achieve their ends.120 Similarly, the United States must, as its Cold War counterparts did, make the expenditure of effort exceed the value of Russian political objectives.121

Seth G. Jones, director of Transnational Threats Project at the Center for Strategic and International Studies, argues that today’s Russia is much weaker than the Soviet state of the 1980s.122 He recommends modifying the U.S. Cold War playbook and developing an information campaign that can compete with Moscow.123 Along that same line, the fear of upsetting bilateral relations due to forceful responses should carry less weight today. The balance between cooperation and confrontation does not require the same careful consideration as it did almost half a century ago.

Former secretary of defense Robert M. Gates notes that since the abolition of the USIA, U.S. diplomacy is just a shadow of its Cold War self.124 Removal of one of the United States’ most effective tools in thwarting Russian gray zone activities is counter to the proposition that other instruments of national power need to take a more active role in enforcing U.S. foreign policy. Because gray zone tactics are not typically geared toward territorial gains and have long-term objectives, civil organizations are better positioned to counter gray zone tactics since these activities comprise many agencies’ core competencies.125

The U.S. intelligence community needs an apolitical tool along the lines of the AMWG that gives information the treatment it deserves as a critical domain. An organization that understands adversary strategy, narratives, and content and is geared to highlight and halt attempts at subversion would serve as a useful nexus between real and fake news. The establishment of the Bureau of International Information Programs (IIP) was a step in the right direction; however, it was not enough. In 2013, the IIP employed a paltry 458 employees (43 percent of which were contractors) and had a budget of $55 million. The IIP had significant structural problems and suffered from low morale.126 This is a far cry from the USIA, which even in its waning years employed more than 8,000 individuals and had an operating budget exceeding $1 billion.127

Current circumstances in U.S. society present an enhanced opportunity in combatting some gray zone activities. The coverage of the 2016 and 2020 elections has placed Russian interference at the forefront of many American minds. This increased awareness has likely elevated critical thinking about sources of information and offers U.S. agencies a wider and less rocky path in hardening the population against subversion.

The other side of this coin, however, is a highly polarized citizenry that is dismissive of any agency advisory or guidance that might be perceived as partisan. While serving in Congress, Newt Gingrich (R-GA), who had taken an interest in the success of the AMWG, seemingly took pains to ensure it remained firmly neutral.128 Gingrich apparently understood the importance of sources and perceived bias in 1985, years before the internet entered the mainstream. Given the speed of information, penchant for flavored commentary, and gravitation toward like-minded opinion, this concern is well-founded. Couching an updated AMWG or USIA within the context of intelligence will help mitigate concerns of politicization and bias since the U.S. intelligence community generally enjoys greater trust than other portions of government.129 Consider the recent debacle in creating a Disinformation Governance Board. Falling under the Department of Homeland Security and intended to focus on disinformation surrounding immigration and Russian threats to critical infrastructure, the organization’s perception as a political tool led to its swift demise.130

In August 2020, Representative Michael McCaul (R-TX) introduced the USIA for Strategic Competition Act, which would reconstitute the AMWG and create an information statecraft strategy for the United States. During five years, the revived AMWG would combat Chinese propaganda and disinformation.131 Although the resolution died during the legislative session, it serves as affirmation that some leaders in government recognize and are concerned about gray zone conflict. Regardless of what organization is tasked to address Russian influence operations, it must be able to identify and block propaganda, help build the resilience of the issue agnostic population, displace Russian narratives with alternative content, and do a better job at telling the American story.132 Above all, personnel must understand the specific motivations behind these actions to better anticipate future efforts.133

For gray zone tactics that rise above ideological subversion, several organizations have offered general strategy recommendations that utilize multiple instruments of power. A majority opinion recognizes the need for organizational and institutional paradigm shifts, especially concerning the Western view of conflict. Findings from most studies have common underlying elements and key in on central themes and approaches.

Although militaries are often essential in imposing a nation’s will, they should play a limited role in gray zone conflict. Gray zone conflict is specifically geared to circumvent traditional U.S. military power, and thrusting uniformed services into the mix risks escalation where none is warranted. Philip Kapusta suggests a benchmark for military intervention—when actions become transnational.134 He also suggests proactive deterrence rather than responding after a crisis erupts, since military intervention is often met with international criticism that might sway states toward adversaries.135 The military’s main strength in gray zone conflict is its ability to improve cyber defenses, enhance intelligence and counterintelligence capabilities, and build partner special forces capacity.136

For issues that do not obviate the need for military action, the State Department should be the central instrument of national security policy.137 The United States has lost many opportunities in strategic messaging and failed to appeal to the nationalist sentiment of other countries subjected to Russian influence operations.138 Statecraft is becoming a lost art that needs to be rediscovered and mastered.139

Russia’s desire to improve its regional and global image provides leverage and an opportunity for U.S. statecraft.140 Effectively attributing aggression and subversion to their source serves two purposes: First, increasing awareness among the international community and exposing Russian tactics will push fence-sitting states toward increased cooperation with the United States. Second, attribution exposes the ideological weaknesses inherent in Russian authoritarianism and will increase financial and security expenses while fostering the perception of a threatened legitimacy.

Conclusion

Gray zone conflict and the challenge it presents are here to stay. Novel technologies, ambiguity, and a shifting geopolitical environment present new opportunity for adversaries to exploit. However, these opportunities are not one-sided. By looking to the past, the United States may find effective strategies to counter activities designed to remain below military thresholds while avoiding escalation. U.S. Cold War tactics in combatting Soviet active measures successfully undermined adversary narratives and tipped the balance between cost and benefit against adversaries. These Cold War counters shared four characteristics: they were proactive, unambiguous, rapidly employed, and enjoyed wide dissemination.

Measures of effectiveness in the gray zone center wholly around influence, underscoring the need for effective communication outlets, transparency, and appropriate signaling. In 2016, U.S. Army Special Operations Command conducted Silent Quest 16-1, an exercise designed to test future operating concepts and define “winning” in the gray zone.141 Results emphasized the importance of the human domain and how information-focused campaigns grant leaders more decision space and greater opportunity to change the course of conflict.142 Maximizing effectiveness in influencing and creating new opportunity and space for the United States while denying adversary positional advantage requires that all instruments of national power are synchronized and firing on all cylinders.

The U.S. ability to move effectively in the gray zone will necessitate a change in temperament concerning war’s evolving analog nature. Realizing that activities are part of a long-term strategy and system rather than ad hoc events, and turning to economic, informational, and diplomatic statecraft rather than military means are the first steps toward success. Appreciating the reason adversaries turn to these tactics is close behind and will help the United States identify and capitalize on weaknesses that necessitated a gray zone approach in the first place.

Endnotes

- Michael J. Mazarr, Mastering the Gray Zone: Understanding a Changing Era of Conflict (Carlisle, PA: Army War College Press, 2015), 73.

- Thomas G. Mahnken, Ross Babbage and Toshi Yoshihara, Counter Comprehensive Coercion: Competitive Strategies Against Authoritarian Political Warfare (Washington, DC: CSBA, 2018), 1.

- Joseph Votel et al., “Unconventional Warfare in the Gray Zone,” Joint Forces Quarterly, no. 80 (January 2016): 101–9; Chad M. Pillai, “The Dark Arts: Application of Special Operations in Joint Strategic and Operational Plans,” Small Wars Journal, 7 June 2018; and Eric Olson, “America’s Not Ready for Today’s Gray Wars,” Defense One, 10 December 2015.

- Department of Defense Dictionary of Military and Associated Terms, Joint Publication 1-02 (Washington, DC: Joint Chiefs of Staff, 2010).

- Kathleen H. Hicks, “Russia in the Gray Zone,” Aspen Institute, 19 July 2019.

- Hicks, “Russia in the Gray Zone.”

- Sun-Tzu and Carl von Clausewitz, The Book of War: Sun-Tzu’s The Art of War & Karl Von Clausewitz’s On War (New York: Modern Library, 2000), 445–46.

- Sun-Tzu and von Clausewitz, The Book of War.

- George F. Kennan, “Policy Planning Staff Memorandum,” in Foreign Relations of the United States, 1945–1950, Emergence of the Intelligence Establishment, ed. C. Thomas Thorne Jr. and David S. Patterson (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1996), 1.

- Kennan, “Policy Planning Staff Memorandum.”

- Kennan, “Policy Planning Staff Memorandum.”

- See Massie, Suzanne, Trust but Verify: Reagan, Russia and Me (Blue Hill, ME: Hearttree Press, 2013), 23–37.

- Votel et al., “Unconventional Warfare in the Gray Zone,” 102.

- Frank G. Hoffman, Conflict in the 21st Century: The Rise of Hybrid Wars (Arlington, VA: Potomac Institute for Policy Studies, 2007), 28.

- Hoffman, Conflict in the 21st Century.

- Hoffman, Conflict in the 21st Century.

- Hoffman, Conflict in the 21st Century.

- Nadia Schadlow, “Peace and War: The Space Between,” War on the Rocks, 18 August 2014.

- Schadlow, “Peace and War.”

- Schadlow, “Peace and War.”

- Schadlow, “Peace and War.”

- See Sam Jones, “Ukraine: Russia’s New Art of War,” Financial Times, 28 August 2014.

- Valery Gerasimov, “Ценность науки в предвидении Новые вызовы требуют переосмыслить формы и способы” , Military Industrial Courier, 26 February 2013; see also Mark Galeotti, “The ‘Gerasimov Doctrine’ and Russian Non-Linear War,” In Moscow’s Shadows (blog), 6 July 2014.

- Gerasimov, “The Value of Science in Foresight”; and Galeotti, “The ‘Gerasimov Doctrine’ and Russian Non-Linear War.”

- Votel, “Statement before the House Armed Services Committee Subcommittee on Emerging Threats and Capabilities,” 18 March 2015, 1.

- Votel, “Statement before the House Armed Services Committee Subcommittee on Emerging Threats and Capabilities.”

- Votel et al., “Unconventional Warfare in the Gray Zone,” 101–9.

- Mazarr, Mastering the Gray Zone.

- Mazarr, Mastering the Gray Zone, 21, 62.

- Adam Elkus, “50 Shades of Gray: Why the Gray Wars Concept Lacks Strategic Sense,” War on the Rocks, 15 December 2015.

- Elkus, “50 Shades of Gray.”

- Elkus, “50 Shades of Gray.”

- Adam Elkus, “Abandon All Hope, Ye Who Enter Here: You Cannot Save the Gray Zone Concept,” War on the Rocks, 30 December 2015.

- See George Popp and Sarah Canna, The Characterization and Conditions of the Gray Zone (Boston, MA: NSI, 2016), 2. Emphasis added.

- Michael J. Green et al., Countering Coercion in Maritime Asia: The Theory and Practice of Gray Zone Deterrence (Washington, DC: Center for Strategic and International Studies, 2017).

- Donald Stoker and Craig Whiteside, “Blurred Lines: Gray Zone Conflict and Hybrid War—Two Failures of American Strategic Thinking,” Naval War College Review 73, no. 1 (Winter 2020): 12–48.

- Stoker and Whiteside, “Blurred Lines.”

- Stoker and Whiteside, “Blurred Lines,”16.

- Stoker and Whiteside, “Blurred Lines,” 14.

- David Carment and Dani Belo, War’s Future: The Risks and Rewards of Grey Zone Conflict and Hybrid Warfare (Calgary, Alberta: Canadian Global Affairs Institute, 2018), 2.

- Operations, Army Doctrine Publication 3-0 (Washington, DC: Department of the Army, 2019), 1-3.

- Mazarr, Mastering the Gray Zone, 47.

- Michael Kofman and Matthew Rojansky, “A Closer Look at Russia’s ‘Hybrid War’,” Kennan Cable, no. 4 (April 2015): 2.

- Department of Defense Dictionary of Military and Associated Terms.

- Operational Environment and Army Learning, Training Circular 7-102 (Washington, DC: Department of the Army, 2014).

- Robert M. Gates, The Prediction of Soviet Intentions (Langley, VA: Center for the Study of Intelligence, Central Intelligence Agency, 1976).

- Maria Snegovaya, Putin’s Information Warfare in Ukraine: Soviet Origins of Russia’s Hybrid Warfare (Washington, DC: Institute for the Study of War, 2015).

- Oscar Jonsson and Robert Seely, “Russian Full-Spectrum Conflict: An Appraisal after Ukraine,” Journal of Slavic Military Studies 1, no. 28 (2015): 1–22, https://doi.org/10.1080/13518046.2015.998118.

- David V. Gioe, Richard Lovering, and Tyler Pachesny, “The Soviet Legacy of Russian Active Measures: New Vodka from Old Stills?,” International Journal of Intelligence and Counterintelligence 33, no. 3 (Fall 2020): 514–39, https://doi.org/10.1080/08850607.2020.1725364.

- Gioe, Lovering, and Pachesny, “The Soviet Legacy of Russian Active Measures,” 523.

- Gioe, Lovering, and Pachesny, “The Soviet Legacy of Russian Active Measures,” 524.

- Gioe, Lovering, and Pachesny, “The Soviet Legacy of Russian Active Measures.”

- Ivo Juurve, The Resurrection of Active Measures: Intelligence Services as a Part of Russia’s Influencing Toolbox, Strategic Analysis 7 (Helsinki, Finland: Hybrid Center of Excellence, 2018), 2.

- S. N. Kaslov, ed., The Officer’s Handbook: A Soviet View (Washington, DC: U.S. Air Force, 1971), 32.

- Elkus, “Abandon All Hope.”

- Calder Walton, “Spies, Election Meddling, and Disinformation: Past and Present,” Brown Journal of World Affairs 26, no. 1 (Fall/Winter 2019): 107–24.

- George F. Kennan, “The Sources of Soviet Conduct,” Foreign Affairs 25, no. 4 (July 1947): 566–82.

- Some argue for adoption of the term support measures as a direct successor to active measures, noting the appearance of the abbreviation MS (meropriyativa sodeistviya [support measures]) in a 1992 document ostensibly written by former KGB officers describing offices so named within both the SVR and FSB. See Snegovaya, Putin’s Information Warfare in Ukraine, 2–3.

- Dennis Kux, “Soviet Active Measures and Disinformation: Overview and Assessment,” Parameters 15, no. 4. (2005): 19–28.

- Lyle J. Morris et al., Gaining Competitive Advantage in the Gray Zone: Response Options for Coercive Aggression Below the Threshold of Major War (Santa Monica, CA: Rand, 2019), https://doi.org/10.7249/RR2942.

- “активные мероприятия,” romanized as aktivnye meropriyatiya.

- See “Inside the KGB: An Interview with Maj. Gen. Oleg Kalugin,” CNN, January 1998; see also Christopher Andrew and Vasili Mitrokhin, The Mitrokhin Archive: The KGB in Europe and the West (New York: Penguin, 2000), 316.

- Steve Abrams, “Beyond Propaganda: Soviet Active Measures in Putin’s Russia,” Connections 15, no. 1 (Winter 2016): 5–31, http://dx.doi.org/10.11610/Connections.15.1.01.

- Abrams, “Beyond Propaganda.”

- Thomas Boghardt, “Soviet Bloc Intelligence and Its AIDS Disinformation Campaign,” Studies in Intelligence 53, no. 4 (December 2009): 8. Additionally, Operation Infektion was variously known as Vorwaerts II or Denver.

- Boghardt, “Soviet Bloc Intelligence and Its AIDS Disinformation Campaign.”

- Ryan P. Westergaard et al., “Racial/Ethnic Differences in Trust in Health Care: HIV Conspiracy Beliefs and Vaccine Research Participation,” Journal of General Internal Medicine, no. 29 (January 2014): 140–46, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-013-2554-6.

- Nicoli Nattrass, “Understanding the Origins and Prevalence of AIDS Conspiracy Beliefs in the United States and South Africa,” Sociology of Health & Illness 35, no. 1 (2013): 113–29, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9566.2012.01480.x.

- Timothy L. Thomas, “Information Warfare in the Second (1999–) Chechen War: Motivator for Military Reform?,” in Russian Military Reform, 1992–2002, ed. Anne C. Aldis and Roger N. McDermott (London: Routledge, 2003), 209–33. Note that the Russian terminology uses the literal term struggle (protivoborstvo) and not warfare (voyenoye delo or voyna), a term implying greater incessance.

- Andrew Monaghan, “Avoiding the Barracuda Effect,” in Russia’s Emerging Global Ambitions (Rome: NATO Defense College, 2020), 3–10.

- Doktrina informatsionnoy bezopasnosti Rossiyskoy Federatsii” [Doctrine of Information Security of the Russian Federation], Nezavisimaya Gazeta, 15 September 2000.

- “Doctrine of Information Security of the Russian Federation.”

- “Russia’s Military Doctrine,” Nezavisimaya Gazeta, 21 April 2000.

- Vladimir Putin, “Doctrine of Information Security of the Russian Federation,” Ministry of Foreign Affairs, 5 December 2016.

- Robert Person, “Four Myths about Russian Grand Strategy,” Center for Strategic and International Studies, 22 September 2020.

- Snegovaya, Putin’s Information Warfare in Ukraine, 9.

- Snegovaya, Putin’s Information Warfare in Ukraine; and Mark Galeotti, “Active Measures: Russia’s Covert Geopolitical Operations,” George C. Marshall European Center for Security Studies, June 2019.

- Galeotti, “Active Measures.”

- Todd C. Helmus et al., Russian Social Media Influence: Understanding Russian Propaganda in Eastern Europe (Santa Monica, CA: Rand, 2018), 7, https://doi.org/10.7249/RR2237.

- Helmus et al., Russian Social Media Influence, 10.

- Helmus et al., Russian Social Media Influence, 3.

- Snegovaya, Putin’s Information Warfare in Ukraine, 10; and Carolina Vendil Pallin and Fredrik Westerlund, “Russia’s War in Georgia: Lessons and Consequences,” Small Wars and Insurgencies 20, no. 2 (2009): 400–24, https://doi.org/10.1080/09592310902975539.

- Bilyana Lilly and Joe Cheravitch, “The Past, Present, and Future of Russia’s Cyber Strategy and Forces” (presentation, 12th International Conference on Cyber Conflict, 2020), 129–55.

- Lilly and Cheravitch, “The Past, Present, and Future of Russia’s Cyber Strategy and Force,” 140.

- Lilly and Cheravitch, “The Past, Present, and Future of Russia’s Cyber Strategy and Force,” 141.

- Lilly and Cheravitch, “The Past, Present, and Future of Russia’s Cyber Strategy and Force,” 143.

- Anna Nemtsova, “A Chill in the Moscow Air,” Newsweek, 5 February 2006.

- Soviet Active Measures in the “Post-Cold War” Era: 1988–1991 (Washington, DC: United States Information Agency, 1992).

- Soviet Active Measures in the “Post-Cold War” Era.

- John Arquilla et al., Russian Strategic Intentions (Monterey, CA: Naval Postgraduate School, 2019), 44.

- Snegovaya, Putin’s Information Warfare in Ukraine, 13.

- Snegovaya, Putin’s Information Warfare in Ukraine.

- Monaghan, “Avoiding the Barracuda Effect,” 4.

- Monaghan, “Avoiding the Barracuda Effect,” 6.

- Monaghan, “Avoiding the Barracuda Effect,” 7.

- Monaghan, “Avoiding the Barracuda Effect,” 8.

- Arquilla et al., “Russian Strategic Intentions,” 32.

- Dani Belo and David Carment, “Grey-Zone Conflict: Implications for Conflict Management,” Canadian Global Affairs Institute, December 2019, 4.

- Kathleen H. Hicks et al., By Other Means, pt. 1, Campaigning in the Gray Zone (Washington, DC: CSIS, 2019).

- Doctrine for the Armed Forces of the United States, JP 1 (Washington, DC: Joint Chiefs of Staff, 2017), I-5.

- Nathan Freier, “The Darker Shade of Gray: A New War Unlike Any Other,” Center for Strategic and International Studies, 27 July 2018.

- Paul Scharre, “American Strategy and the Six Phases of Grief,” War on the Rocks, 6 October 2016.

- Steven Metz, “In Ukraine, Russia Reveals Its Mastery of Unrestricted Warfare,” World Politics Review, 16 April 2014.

- Mazarr, Mastering the Gray Zone, 73.

- John Schaus and Michael Matlaga, “Competing in the Gray Zone,” Center for Strategic and International Studies, 24 October 2018.

- Schaus and Matlaga, “Competing in the Gray Zone.”

- Mazarr, Mastering the Gray Zone, 73.

- Nora Bensahel, “Darker Shades of Gray: Why Gray Zone Conflicts Will Become More Frequent and Complex,” Foreign Policy Research Institute,13 February 2017.

- “People Don’t Trust Social Media—That’s a Growing Problem for Businesses,” CBS News, 18 June 2018; and Roger McNamee and Maria Ressa, “Facebook’s ‘Oversight Board’ Is a Sham. The Answer to the Capitol Riot Is Regulating Social Media,” Time, 28 January 2021.

- Emilio J. Iasiello, “Russia’s Improved Information Operations: From Georgia to Crimea,” Parameters 47, no. 2 (Summer 2017): 51–64, https://doi.org/10.55540/0031-1723.2931.

- Robert S. Mueller III, Report on the Investigation into Russian Interference in the 2016 Presidential Election, 2 vols. (Washington, DC: Department of Justice, 2019).

- Soviet Active Measures in the Era of Glasnost (Washington, DC: United States Information Agency, 1988), 88.

- Hal Brands, “Paradoxes of the Gray Zone,” Foreign Policy Research Institute, 5 February 2016.

- Fletcher Schoen and Christopher J. Lamb, Deception, Disinformation, and Strategic Communications: How One Interagency Group Made a Major Difference, Strategic Perspectives 11 (Washington, DC: National Defense University Press, 2012), 63.

- “Deploying Reality Against Putin,” Economist, 26 February 2022.

- Schaus and Matlaga, “Competing the Gray Zone,” 12.

- See Snegovaya, Putin’s Information Warfare in Ukraine, quoting Ion Mihai Pacepa, former Soviet intelligence officer, 15. Campaigns always followed a three-pronged approach: deny direct involvement, minimize the damage, and when the truth comes out, insist that the enemy was at fault.

- Snegovaya, Putin’s Information Warfare in Ukraine, 520–21.

- Philip Kapusta, The Gray Zone (Tampa, FL: U.S. Special Operations Command, 2015).

- Anthony H. Cordesman and Grace Hwang, Chronology of Possible Russian Gray Area and Hybrid Warfare Operations (Washington, DC: Center for Strategic and International Studies, 2020).

- Matthew Jamison, “Clausewitz and the Strategic Deficit,” Wavell Room, 21 May 2021.

- Seth G. Jones, “Going on the Offensive: A U.S. Strategy to Combat Russian Information Warfare,” Center for Strategic and International Studies, 1 October 2018.

- Jones, “Going on the Offensive.”

- Robert M. Gates, “The Overmilitarization of American Foreign Policy: The United States Must Recover the Full Range of Its Power,” Foreign Affairs 99, no. 4 (July/August 2020).

- Stacie L. Pettyjohn and Becca Wasser, Competing in the Gray Zone: Russian Tactics and Western Responses (Santa Monica, CA: Rand, 2019), xi, https://doi.org/10.7249/RR2791.

- “Inspection of the Bureau of International Information Programs,” U.S. Department of State, May 2013.

- Nancy Snow, “United States Information Agency,” Foreign Policy in Focus, 1 August 1997.

- Schoen and Lamb, Deception, Disinformation, and Strategic Communication, 57.

- Steve Slick, Joshua Busy, and Kingsley Burns, “Annual Polling Confirms Sustained Public Confidence in U.S. Intelligence,” Lawfare (blog), 10 July 2019.

- Sean Lyngaas, Priscilla Alvarez, and Natasha Bertrand, “Expert Hired to Run DHS’ Newly Created Disinformation Board Resigns,” CNN, 18 May 2022.

- USIA for Strategic Competition Act, H.R. 7938, 116th Cong. (2020).

- Helmus et al., Russian Social Media Influence, 75.

- Lilly and Cheravitch, “The Past, Present, and Future of Russia’s Cyber Strategy and Forces,” 147.

- Kapusta, The Gray Zone, 6.

- Kapusta, The Gray Zone, 3.

- Pettyjohn and Wasser, Competing in the Gray Zone, 44.

- Gates, “The Overmilitarization of American Foreign Policy.”

- Gates, “The Overmilitarization of American Foreign Policy.”

- Max Boot and Michael Doran, “Political Warfare,” Council on Foreign Relations Policy Innovation Memorandum No. 33, 7 June 2013, 1–4.

- Morris et al., Gaining Competitive Advantage in the Gray Zone, 133.

- Expanding Maneuver in the Early 21st Century Security Environment (Tampa, FL: U.S. Army Special Operations Command, 2017).

- Expanding Maneuver in the Early 21st Century Security Environment, 8.