Jonathan Robinson

13 April 2022

https://doi.org/10.36304/ExpwMCUP.2022.05

PRINTER FRIENDLY PDF

EPUB

AUDIOBOOK

Abstract: This article explores trends in Russian foreign humanitarian assistance (FHA) during the past 15 years by using open-source data from 40 Russian entities that have reported delivering aid 5,014 times to Georgia, Ukraine, Syria, and Nagorno-Karabakh. From this data, five key findings about Russia’s FHA capabilities emerge, showing that Russian aid is heavily influenced by the state, is symbolic, and is urban-focused; that Russia is unable to conduct more than one significant country response at a time; and that Russia’s FHA model is influenced by the context to which Russia is responding.

Keywords: aid delivery, foreign humanitarian assistance, humanitarian aid, humanitarian response, Russia, Georgia, Ukraine, Syria, Nagorno-Karabakh, soft power

Russia’s 2022 invasion of Ukraine, its second in less than a decade, has created a significant humanitarian crisis in Europe.1 Russia’s actions will likely deprive hundreds of thousands of civilians of essential services, despite the presence of the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) and other experienced humanitarian agencies that are providing collaborative, principled, and people-focused support to the people of Ukraine.2 Yet, there are signs that Russia’s aid apparatus is spinning into gear and preparing to respond to the crisis.3 If deployed, this would mark the fifth time that Russia has provided foreign humanitarian assistance (FHA) to a complex emergency in 15 years. Russia conducted FHA operations in the Georgian regions of Abkhazia and South Ossetia after its 2008 invasion of Georgia; in the Ukrainian regions of Donetsk, Luhansk, and Crimea after its first invasion of Ukraine in 2014; in Syria after its official intervention in the Syrian Civil War in late 2015; and most recently in the Nagorno-Karabakh region that is disputed between Armenia and Azerbaijan after conflict erupted there in 2020.

Until now, knowledge about Russia’s FHA has been woefully out of date. The most recent U.S. Law Library of Congress report detailing how Russia conducts FHA is from 2011, while the latest publication from the European Union (EU) is from 2016.4 This article will update these studies and explore current trends in Russia’s FHA by using open-source data detailing 5,014 aid deliveries by 40 Russian entities to Georgia, Syria, Ukraine, and Nagorno-Karabakh during the past 15 years. As a result of this research, it is hoped that scholars and practitioners who are focused on Russia will be better informed about the current capabilities of Russia’s FHA, especially in relation to any potential future Russian humanitarian response in Ukraine.

Key Sources for Russian Views on Aid

Several types of sources highlight how Russia thinks about and conducts foreign aid. First and foremost are its international development assistance concepts from 2007 and 2014, two key policy documents from the Ministry of Finance (MOF) and Ministry of Foreign Affairs (MOFA) that detail how Russia considers and prioritizes its foreign humanitarian and development activity.5 Subsequent MOFA updates in 2016 and 2021 also dedicate sections to FHA that largely align to the 2014 concept.6

Public statements made by key figures in Russia’s humanitarian ecosystem can also be used to gain knowledge on the projected intent of Russian aid. Notable figures in this ecosystem include Yevgeny Primakov Jr., current head of Rossotrudnichestvo (the Federal Agency for the Commonwealth of Independent States Affairs, Compatriots Living Abroad, and International Humanitarian Cooperation); Dmitry Sablin, a member of the Russian State Duma and deputy chairman of the Russian Combat Brotherhood Veterans Organization; Reverend Hieromonk Stefan Igumnov, head of the Interreligious Working Group and in charge of the Russian Orthodox Church’s humanitarian activities in the Middle East and North Africa; and Sergei Shoigu, the current Russian minister of defense and a former minister for emergency situations.7

Finally, there is a wide array of publicly available information about Russian humanitarian aid deliveries that can be gleaned from the websites and social media pages of Russian entities that have reported distributing aid in Georgia, Ukraine, Syria, and Nagorno-Karabakh. Records of 5,014 individual aid deliveries from 40 such entities covering a 15-year period for Georgia, a 9-year period for Syria, a 7-year period for Ukraine, and a 1-year period for Nagorno-Karabakh have been collected and analyzed by the author for the purpose of this study.8

As a caveat, the author recognizes that significant bias is present in all the sources used in this study, which could limit its findings. For example, the information reported by the Russian entities referenced herein could be skewed toward how each entity wants to craft its public image. Using open-source data may also miss unreported actions by these entities. Despite these limitations, the data is still useful because it provides a window into how Russia wants the world to see its aid efforts, in effect allowing readers to view Russia’s foreign humanitarian activity through its own eyes.

How Russia Uses Foreign Humanitarian Assistance

Before the findings of this study are presented, it is important to frame Russia’s notion of FHA, as its interpretation is markedly different from the rest of the Western humanitarian community.

In Russia, the notion of humanitarian assistance, or what it terms humanitarian cooperation, is more expansive than in the West. Not only does the Russian definition encompass development activity, disaster relief, and humanitarian aid as the West recognizes it, but it also includes cultural diplomacy and peacekeeping.9 Rather than separating out these categories as distinct activities in their own right, they are all viewed as part of humanitarian cooperation, meaning that a cultural diplomacy activity is seen in the same way as a delivery of food and water. Indeed, Yevgeny Primakov Jr., current head of Rossotrudnichestvo, acknowledged this misalignment with the West in a media interview in 2019, noting that perceptions of humanitarian assistance in Russia are “strikingly different from what is commonly understood by rest of the world” and are often more “associated with the sphere of culture.”10

Furthermore, when looking at Russia’s interpretation of FHA in its 2014 international development assistance policy, it is clear that Russia defines FHA as a much broader concept than does the United Nations (UN)-led international humanitarian community, which narrowly frames FHA though activities that save lives and alleviate suffering.11 Russia defined FHA as revolving around nine overarching goals, just two of which were linked to humanitarian action as the West could recognize it: aim to “eliminate poverty” and address “the consequences of humanitarian, natural, environmental, and industrial disasters and other emergencies.”12 The remaining seven goals focus on international development activities, international cooperation, and improving Russia’s global image.13

Russia’s notion and definition of humanitarian cooperation makes no mention of the four humanitarian principles of humanity, impartiality, neutrality, and independence. These key principles are important mechanisms for humanitarians to ensure the safety of humanitarian workers and those whom they serve by prioritizing the needs of vulnerable people based on their needs alone, responding to human suffering wherever it is found, and separating humanitarian action from political or military objectives.14 The erosion of these principles can lead to a fatal reduction in trust in the wider aid system by armed actors and those that receive aid alike, as examples in Afghanistan and other countries have shown.15 A MOFA policy update from 2016 showed that Russia does not view humanitarian aid as neutral or independent at all, with the policy update stating that humanitarian aid is an “integral part of [Russia’s] efforts to achieve foreign policy objectives.”16

There is a lack of alignment between Russia’s broader notions, definitions, and goals of its form of FHA (humanitarian cooperation) and the narrower, more principled focus of humanitarian assistance in the wider, UN-led humanitarian system. Such disconnects could arguably lead to significant misunderstandings between the two sides, which is something that has already been seen in some prominent Western commentators’ discussions about Russia’s humanitarian actions in Syria.17

How Aid Reinforces Russian Soft-Power Efforts

While Western countries use FHA to promote their own narratives, there is typically a degree of separation between state power and humanitarian efforts. For example, the United States uses a centralized agency, USAID, to support hundreds of intergovernmental and nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) rather than directly distribute aid by itself or through other state institution.18 In turn, these nonstate entities are accountable to their own boards and monitoring and evaluation procedures, as well as other government donor requirements if they receive funding elsewhere. They also collaborate with the UN’s cluster system.19 USAID and other Western government aid donors have also signed up to the principles of the Good Humanitarian Donorship initiative, a framework that supports effective funding of FHA.20 All these factors go some way in diluting state influence in the foreign aid system.

In contrast, Russia does not have a centralized agency coordinating its aid, nor has it signed up to the Good Humanitarian Donorship principles.21 Instead, a number of state institutions frame, fund, and facilitate Russia’s official FHA, including the MOFA, the MOF, the Ministry of Defence (MOD), the Ministry of Emergency Situations (EMERCOM), the Federal Agency of State Reserves (Rosrezerv), and the Russian Orthodox Church.22 Despite this lack of formal centralization, it is clear from Russia’s own reported data that two state institutions in particular, MOD and EMERCOM, lead the nation’s aid efforts on the ground.23

A small part of Russia’s foreign aid in Georgia, Ukraine, Syria, and Nagorno-Karabakh has also been delivered by several secular or religiously orientated NGOs. However, the apparent separation of state control from these NGOs is merely an illusion. Further investigation of these entities show that many are informally accountable to the Russian state through their leaders, who often work for or advise Russian state leadership, including the president’s office.24 Further reinforcing this masked state influence is that these quasi-autonomous NGOs (QANGOs) also rarely integrate into UN-led humanitarian coordination systems.25 When looking at the reported data about QANGO aid deliveries in the contexts analyzed for this study, the author found that many QANGOs conduct joint missions with Russian state institutions rather than independently in their own capacity. In effect, this reliance on the state makes these QANGOS masked implementing partners of Russia.

This design ensures that state control not only continues to be exerted across the whole of Russia’s humanitarian ecosystem but also that Russia’s soft power efforts in its FHA are self-sufficient. In effect, Russia creates the impression that it has a diverse aid system in the countries in which it operates. Truthfully, however, Russia’s aid system is one that the state can control and which provides the state a degree of finesse in its FHA efforts, as it can tailor the type of entity responding to a specific community.26 In Syria, for example, the Chechen-based Akhmad Kadyrov Foundation has supported Sunni Muslim communities, the Russian Orthodox Church has supported Christian communities, and the MOD’s Center for Reconciliation of Conflicting Sides has delivered aid to communities near high-risk frontlines.

Russia has also shown that it can translate the actions of its humanitarian ecosystem into strategic-level gains. A clear example of this can be found in Russia’s response to the Ebola epidemic in Guinea in late 2014. After initially providing a mobile medical team and laboratory, medical resources, and two field hospitals, Russia soon capitalized on the momentum of good will that it garnered from these activities.27 Within two years, Russia had signed a series of long-term agreements with Guinea’s ministries of health and education; received public praise as a key partner at an international conference in Brussels, Belgium, by the president of Guinea, Alpha Condé; and saw the MOD and several Russian academic institutions and private-sector companies make inroads into the country.28 Essentially, Russia’s humanitarian support was used as a vehicle to build stronger ties with Guinea, much more so than in previous years which had only seen a handful of token food aid deliveries.29

Description of Data Used in This Study

To assist with exploring trends in Russia’s FHA in Georgia, Ukraine, Syria, and Nagorno-Karabakh, a data set was created by this author. This data set used publicly available English- and Russian-language information from the websites and social media pages of Russian entities that reported delivering aid to the four abovementioned contexts during the past 15 years. Information was collected from 40 Russian entities, including 17 Russian state organizations and 23 QANGOs. These entities are listed in the following tables:

Table 1. Russian state entities used in this study

| No. |

State entity |

Website |

Comments |

| 1 |

Akhmet Kadyrov Foundation |

https://fondkadyrova.net/ |

|

| 2 |

Federal Agency for State Reserves (Rosrezerv) |

https://rosrezerv.gov.ru/ |

|

| 3 |

Federal Service for Surveillance on Consumer Rights Protection and Human Wellbeing (Rospotrebnadzor) |

https://www.rospotrebnadzor.ru/ |

|

| 4 |

Federal Agency for the Commonwealth of Independent States Affairs, Compatriots Living Abroad, and International Humanitarian Cooperation (Rossotrudnichestvo) |

https://russianassistance.ru/en/ |

A public dashboard managed by Rossotrudnichestvo |

| 5 |

Ingushetia Regional Government |

N/A |

Found from reporting by the Russian Syrian-Business Council QANGO |

| 6 |

Ministry of Defence (Center for Reconciliation and Conflicting Sides) |

http://syria.mil.ru/peacemaking_en/ |

For Syria |

| 7 |

Ministry of Emergency Situations (EMERCOM) |

https://en.mchs.gov.ru/ |

|

| 8 |

Ministry of Foreign Affairs |

https://www.mid.ru/en/foreign_policy/humanitarian_cooperation |

|

| 9 |

Ministry of Health |

https://minzdrav.gov.ru/ |

|

| 10 |

Moscow Municipal Government |

https://www.mos.ru/en/news/ |

|

| 11 |

Russian Chamber of Commerce |

https://tpprf.ru/en/news/ |

|

| 12 |

Russian Orthodox Church |

http://www.patriarchia.ru/ |

|

| 13 |

Russian State Humanitarian University |

https://www.rsuh.ru/en/ |

|

| 14 |

Russian State Medical University |

https://www.russiansmu.com/ |

|

| 15 |

Russian State University |

N/A |

Found from reporting by the Russian Humanitarian Mission QANGO |

| 16 |

Ugra Region Government |

https://ugra-aif-ru/ |

|

| 17 |

United Russia Party |

https://er.ru/ |

|

Source: courtesy of the author.

Table 2. Russian QANGOs used in this study

| No. |

QANGO entity |

Website |

Comments |

| 1 |

Arab Diaspora NGO |

N/A |

Found from reporting by the Russian Orthodox Church |

| 2 |

Children of Russia: The Future of the World Foundation |

https://bf-detirossii.ru/ |

|

| 3 |

Citizenship and Membership Movement |

N/A |

Found from reporting by the Ministry of Defense in Syria |

| 4 |

Combat Brotherhood Veterans Association |

https://bbratstvo.com/ |

|

| 5 |

Eurasian People’s Union |

N/A |

Found from reporting by the Russian Orthodox Church |

| 6 |

Fair Aid Foundation |

https://doctorliza.ru/ |

|

| 7 |

Forty Forties Foundation |

https://soroksorokov.ru/posts/ |

|

| 8 |

Hayat Foundation |

https://hayatfund.ru/ |

|

| 9 |

Hurry to Good Foundation |

https://www.facebook.com/speshikdobru |

|

| 10 |

Imperial Orthodox Palestine Society |

https://www.ippo.ru/humanitarian/ |

|

| 11 |

Public Diplomacy Fund |

https://gorchakovfund.ru/en/ |

|

| 12 |

RUSSAR |

https://www.frussar.com/ |

|

| 13 |

Russian Armenian Humanitarian Center |

http://www.rachr.ru/en/arhiv/ |

|

| 14 |

Russian Humanitarian Mission |

https://rhm.agency/ |

|

| 15 |

Russia Humanitarian Volunteer Corps |

https://vk.com/gumkorpus |

|

| 16 |

Russian Serbian Humanitarian Center |

http://ru.ihc.rs |

|

| 17 |

Russian-Syrian Business Council |

https://www.russia-syria.ru/ |

|

| 18 |

Russian Union of Rescuers (Rossoyuzspas) |

https://ruor.org/ |

|

| 19 |

St. Andrew’s the First Foundation |

https://fap.ru/ |

|

| 20 |

St. Paul the Apostle Foundation |

http://www.pavelfond.ru/ |

|

| 21 |

We Public Organization |

N/A |

Found from reporting by the United Russia Party |

| 22 |

Yelitsa Orthodox Social Network |

https://elitsy.ru/posts/ |

|

| 23 |

Znanie Russian Regional Charity |

http://fond-znanie.com/ |

|

Source: courtesy of the author.

A total of 5,014 aid deliveries by 40 Russian entities covering a time period between November 2006 and November 2021 could be found and collated by the author. Exploring this data further, Syria saw the most reporting about Russian aid delivery at 76 percent (3,819 reports), followed by Ukraine, at 12 percent (589 reports); Nagorno-Karabakh, at 6.5 percent (328 reports); and the Georgian regions of Abkhazia and South Ossetia, at 5.5 percent (278 reports). The following table offers more detail:

Table 3. Reported aid deliveries by context used in this study

| Context |

Number of reports |

Time period |

| Georgia |

278 |

November 2006–November 2021 |

| Syria |

3,819 |

March 2012–November 2021 |

| Ukraine |

589 |

March 2014–November 2021 |

| Nagorno-Karabakh |

328 |

November 2020–November 2021 |

| TOTAL |

5,014 |

individual aid deliveries from 40 Russian entities between November 2006 to November 2022 |

Source: courtesy of the author.

To help draw comparisons, the collected data on Russian aid deliveries was then categorized into four broad themes: 1) how much aid each entity reported delivering in each context; 2) the types of aid reported being delivered in each context; 3) the locations and frequency of reported aid delivered in each context; and 4) the duration of reported aid in each context (tables 4 and 5).

Table 4. Proportions of aid delivered in each context by each Russian entity

| Entity |

Georgia (278 deliveries) |

Ukraine (589 deliveries) |

Syria (3,819 deliveries) |

Nagorno-Karabakh (328 deliveries) |

| Ministry of Defence |

2.52% |

0.00% |

86.83% |

92.00% |

| Akhmet Kadyrov Foundation |

0.00% |

0.85% |

6.44% |

0.00% |

| Joint Missions between Multiple Entities |

1.08% |

2.21% |

4.32% |

5.00% |

| Armenian Russian Humanitarian Center |

0.00% |

0.00% |

0.00% |

1.50% |

| Ministry of Emergency Situations (EMERCOM) |

78.06% |

45.84% |

0.18% |

0.60% |

| Russian Humanitarian Mission |

0.00% |

0.34% |

0.45% |

0.60% |

| Federal Agency for State Reserves (Rosrezerv) |

0.00% |

0.00% |

0.03% |

0.30% |

| Combat Brotherhood Veterans Association |

0.72% |

11.71% |

0.45% |

0.00% |

| Russian Orthodox Church |

11.15% |

25.47% |

0.37% |

0.00% |

| Imperial Orthodox Palestine Society |

0.00% |

2.04% |

0.26% |

0.00% |

| RUSSAR |

0.00% |

0.00% |

0.16% |

0.00% |

| St. Paul the Apostle Foundation |

0.00% |

0.00% |

0.16% |

0.00% |

| Federal Agency for the Commonwealth of Independent States Affairs, Compatriots Living Abroad, and International Humanitarian Cooperation (Rossotrudnichestvo) |

0.00% |

0.00% |

0.08% |

0.00% |

| Federal Agency for Surveillance on Consumer Rights Protection and Human Wellbeing (Rospotrebnadzor) |

2.88% |

0.34% |

0.05% |

0.00% |

| Public Diplomacy Fund |

0.00% |

0.00% |

0.05% |

0.00% |

| Russian Humanitarian Volunteer Corps |

0.00% |

0.00% |

0.05% |

0.00% |

| Ministry of Foreign Affairs |

1.44% |

0.00% |

0.03% |

0.00% |

| Ministry of Health |

0.00% |

0.00% |

0.03% |

0.00% |

| Ugra State Government |

0.00% |

0.00% |

0.03% |

0.00% |

| Fair Aid Foundation |

0.00% |

2.72% |

0.03% |

0.00% |

| Hayat Foundation |

0.00% |

0.34% |

0.03% |

0.00% |

| Children of Russia |

1.44% |

3.90% |

0.00% |

0.00% |

| Moscow Municipal Government |

0.36% |

0.00% |

0.00% |

0.00% |

| St. Andrew’s the First Foundation |

0.36% |

0.34% |

0.00% |

0.00% |

| Unidentified Russian state entity |

0.00% |

0.34% |

0.00% |

0.00% |

| United Party Russia |

0.00% |

2.72% |

0.00% |

0.00% |

| Russian Union of Rescuers (Rossoyuzspas) |

0.00% |

0.85% |

0.00% |

0.00% |

Source: courtesy of the author.

Table 5. Proportions of the types of aid delivered in each context

| Aid type |

Georgia (278 deliveries) |

Ukraine (589 deliveries) |

Syria (3,819 deliveries) |

Nagorno-Karabakh (328 deliveries) |

| Demining |

8% |

3% |

1% |

28% |

| Health |

18% |

6% |

20% |

21% |

| Construction |

32% |

1.5% |

1% |

15% |

| Multiple types of aid delivered in a single action |

4% |

10% |

16% |

12% |

| Area security |

0% |

0% |

0% |

12% |

| Education |

5% |

3% |

1% |

3% |

| Unknown |

5% |

44% |

9% |

3% |

| Food/water |

13% |

22% |

49% |

2% |

| Nonfood items |

1% |

4% |

2% |

2% |

| Search and rescue |

2% |

0.3% |

0% |

2% |

| Cash |

2% |

1% |

0% |

0% |

| Firefighting equipment |

2% |

3% |

0% |

0% |

| Power |

2% |

1% |

0% |

0% |

| Shelter |

6% |

0.2% |

0% |

0% |

Source: courtesy of the author.

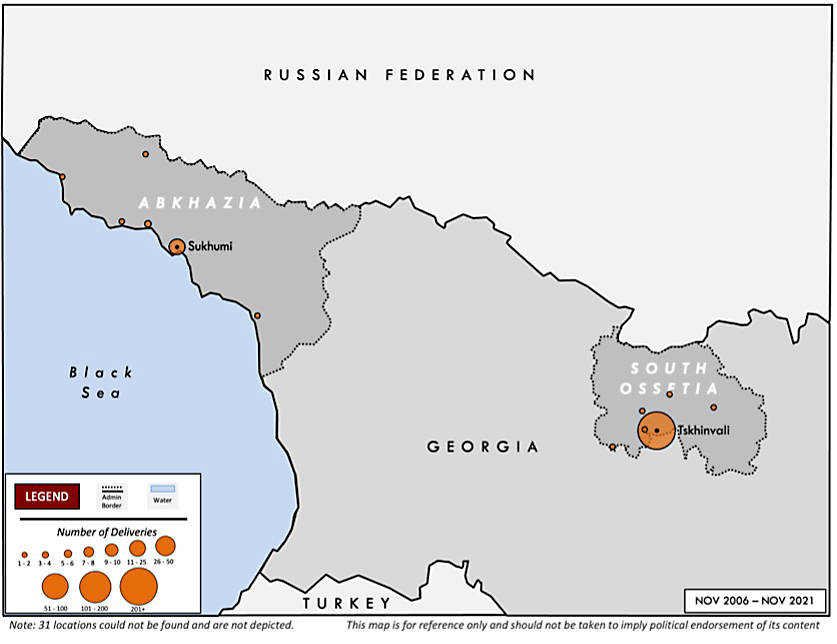

Figure 1. Locations of reported Russian aid deliveries in Abkhazia/South Ossetia used in this study

Source: courtesy of the author.

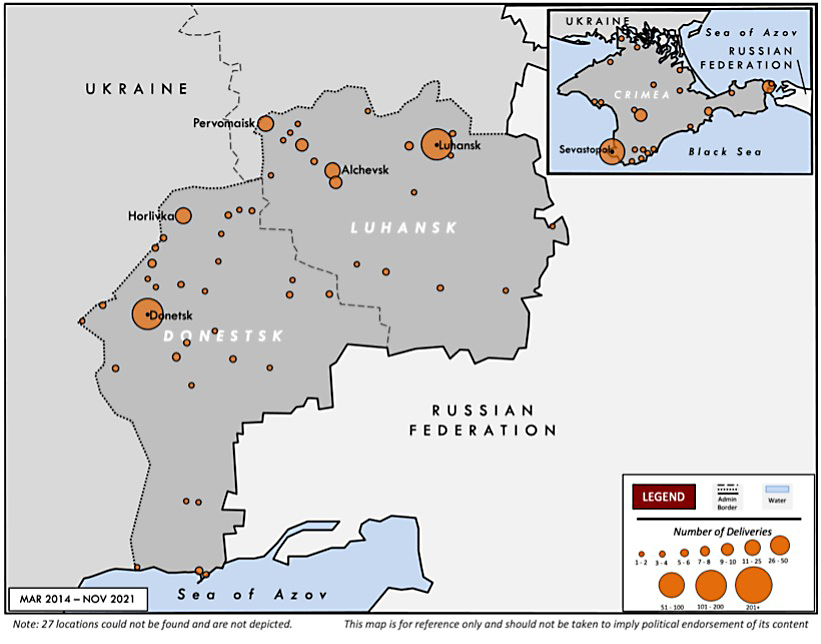

Figure 2. Locations of reported Russian aid deliveries in Ukraine used in this study

Source: courtesy of the author.

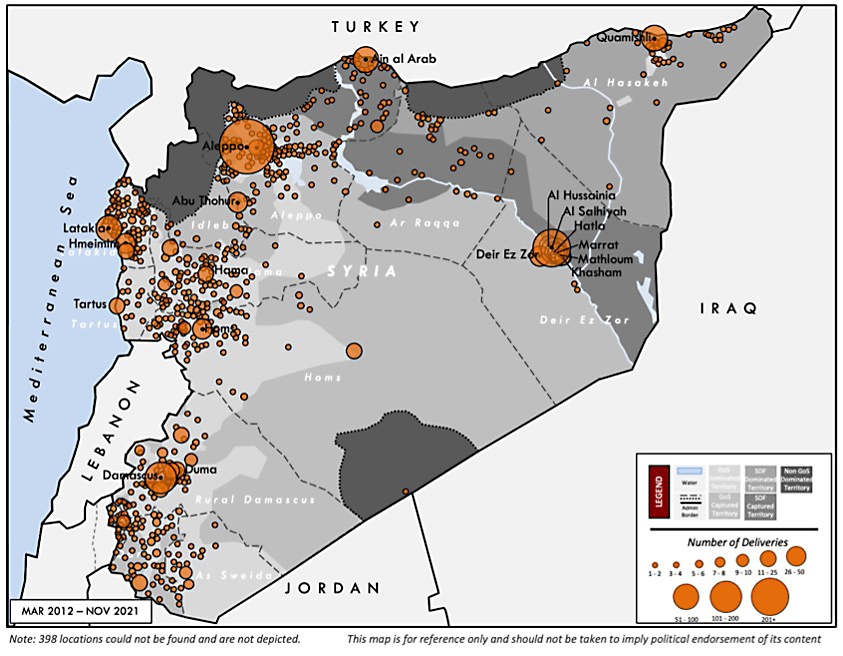

Figure 3. Locations of reported Russian aid deliveries in Syria used in this study

Source: courtesy of the author.

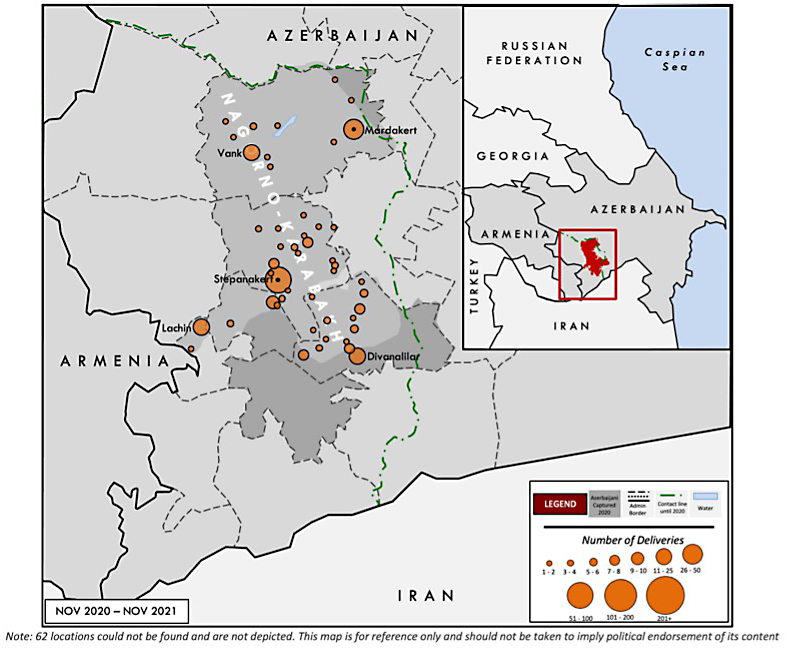

Figure 4. Locations of reported Russian aid deliveries in Nagorno-Karabakh used in this study

Source: courtesy of the author.

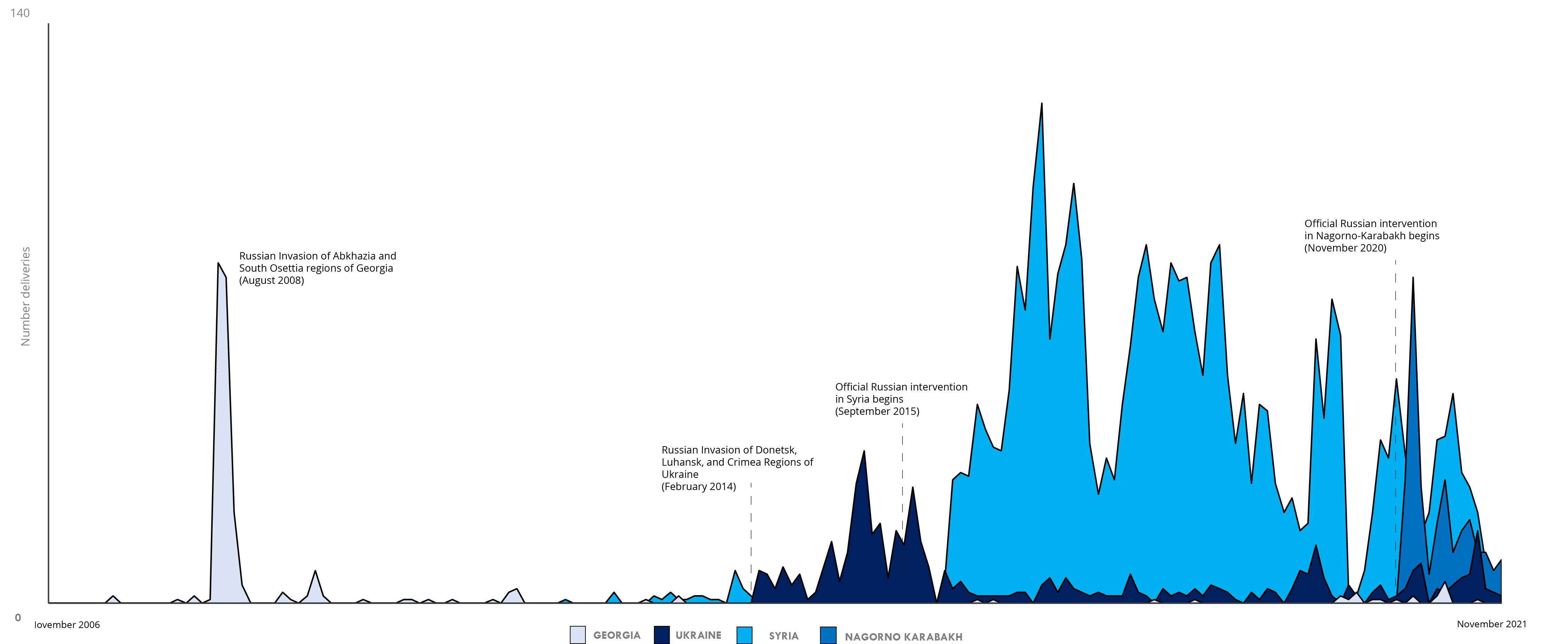

Figure 5. Timeline of monthly reported Russian aid deliveries in Abkhazia/South Ossetia, Ukraine, Syria, and Nagorno-Karabakh from November 2006 to November 2021 used in this study

Source: courtesy of the author.

Trends in Russia’s Foreign Humanitarian Assistance from Its Actions on the Ground

Leveraging the dataset of 5,014 aid deliveries by 40 Russian entities in Abkhazia/South Ossetia, Ukraine, Syria, and Nagorno-Karabakh between 2006 and 2021, five key trends emerge about Russia’s FHA activity. These can be summarized as follows:

- context influences Russia’s aid provision model;

- Russian aid is shallow and symbolic, focusing on supply rather than impact;

- Russian aid is predominantly delivered to urban nodes and key frontiers;

- Russia appears to have limited capacity to mount more than one significant country response at a time; and

- state influence is growing in Russia’s aid provision, especially in its QANGO sector. Each of these trends is described in more detail in the following sections.

Context Influences How Russia Responds

It appears that the context in which Russian humanitarian assistance is given can influence which entity primarily leads the response, from where the response is conducted, what type of aid is delivered, and how transparent Russia is in reporting its aid provision. During Russia’s earliest two interventions in Georgia and Ukraine, EMERCOM facilitated the majority of aid from outside the two countries (56 percent, or 487 of 867 aid deliveries), while in Russia’s more recent interventions in Syria and Nagorno-Karabakh, two MOD specialized humanitarian centers delivered most of Russia’s aid from within the two countries (87 percent, or 3,613 of 4,147 aid deliveries).30

This pattern could be related to how Russia views the four contexts, with Georgia and Ukraine being seen within Russia’s sphere of influence and Syria and Nagorno-Karabakh being seen as more external to Russia.31 This could explain why aid provision in the former two areas comes under the jurisdiction of EMERCOM, Russia’s internal disaster management service, and in the latter two contexts comes under the externally focused MOD. It may also provide a rationale for why Abkhazia/South Ossetia and Ukraine see more Russian secondary aid (which is focused on restoring normal life through such activities as explosive ordnance disposal and construction) following initial food, water, and medical provision, while in Syria and Nagorno-Karabakh there was less transparency in the reporting of secondary types of aid. Indeed, one-fifth of all aid deliveries analyzed for this study either did not specify what type of aid was delivered (13 percent) or did not mention where the aid was delivered (7 percent). Ironically, Russia recently pushed the UN to be more transparent with its aid provision in Syria during negotiations over the renewal of the cross-border aid delivery mechanism in 2020, clearly deflecting attention away from its own shortcomings.32

Notably, there is also a correlation between the switch from EMERCOM as the lead aid provider in Georgia and Ukraine to the MOD in Syria and Nagorno-Karabakh and the promotion of Sergei Shoygu from the minister of EMERCOM to the minister of defense in late 2012. This correlation could suggest that Shoygu is a key actor in Russia’s humanitarian foreign policy.33

Russia’s Aid Is Shallow and Symbolic

It is evident from this data that Russian aid deliveries are focused more on supply than on impact. Of the 842 communities that could be identified as having Russian aid delivered to them in the past 15 years, 821 (97.5 percent) were symbolically served by limited aid deliveries.34 These were either one-off visits (485 communities) or a series of visits numbering fewer than 20 (336 communities). Just 21 locations (2.5 percent) could be described as seeing notable levels of aid, with 30 visits or more:

- Aleppo, Syria (1,033 deliveries)

- Al-Salihiyah, Deir ez-Zor Governorate, Syria (304 deliveries)

- Tskhinvali, South Ossetia (224 deliveries)

- Donetsk, Ukraine (153 deliveries)

- Luhansk, Ukraine (136 deliveries)

- Damascus, Syria (102 deliveries)

- Qamishli, Syria (79 deliveries)

- Ayn al-Arab, Syria (69 deliveries)

- Latakia, Syria (60 deliveries)

- Stepanakert, Nagorno-Karabakh (56 deliveries)

- Hmeimim, Syria (55 deliveries)

- Sevastopol, Ukraine (55 deliveries)

- Marrat, Syria (54 deliveries)

- Khasham, Syria (46 deliveries)

- Mathloum, Syria (45 deliveries)

- Al-Hussainia, Syria (41 deliveries)

- Hatla, Syria (39 deliveries)

- Abu Thohur, Syria (38 deliveries)

- Mardakert, Nagorno-Karabakh (31 deliveries)

- Deir ez-Zor, Syria (30 deliveries)

Russian Aid Is Predominantly Delivered to Urban Nodes and Key Frontiers

When viewing these top 21 locations where 53 percent of Russian aid was delivered, it becomes clear that the majority were urban areas and/or located on key frontiers between fighting sides. Examples of these nodes include Aleppo and Deir ez-Zor in Syria, Donetsk and Luhansk in Ukraine, Tskhinvali in Georgia, and Stepanakert in Nagorno-Karabakh. As the world becomes more urbanized, understanding how to operate efficiently and respond to populations in cities will be a key feature to FHA in any future context.35 During the past 15 years, Russia has gained considerable but underappreciated experience in conducting its form of urban humanitarian operations in these types of specialized environments.36 This, in turn, has been used to complement and diversify Russia’s military and political actions in a given context.37

Russian aid also been used to showcase its soft power at the expense of the U.S. military, especially in Syria. For example, Al-Salihiyah, Deir ez-Zor Governorate, is both an urban node and on a key frontier. Its population of around 47,000 (according to Russian sources) received nearly 10 percent of all Russian aid in Syria despite accounting for less than 0.5 percent of Syria’s estimated 11.1 million people in need in 2019.38 While these actions arguably could have been in response to the significant needs of the area after the city of Deir ez-Zor was besieged by ISIS (Islamic State) for more than three years between 2014 and 2017, the district is also located at a key crossing point between territory controlled by the U.S.-backed Syrian Democratic Forces and areas under the influence of the government of Syria.39

As such, Russia’s actions in Al-Salhiyah could be viewed as an opportunity for it to showcase its soft power at the expense of the U.S. military, which had been conducting limited humanitarian efforts in the same area.40 Russia also appeared to use its experience in urban areas and frontiers to inform its strategic-level thinking in mid-2021, when it pushed for a replacement of the cross-border aid mechanism to northwest Syria to become a cross-line aid mechanism by 2022.41 If this change happens, aid in Syria will be controlled from the city of Damascus and be delivered through key nodes along front lines.

Russia Appears to Have Limited Capacity to Mount More than One Significant Country Response at a Time

The reported data from the ground shows that Russia’s aid provision lacks commitment in the long term. There is a general trend of decline in Russia’s aid deliveries over time in all four contexts analyzed in this report. When taking an even wider view, there is significant correlation between reductions in aid deliveries in one context and the start of a new humanitarian operation in another, especially between Ukraine and Syria.

State Influence Is Growing in Russia’s Aid Provision, Especially in the QANGO Sector

While the majority of Russia’s reported 5,014 aid deliveries in Georgia, Ukraine, Syria, and Nagorno Karabakh have been conducted by state entities (83 percent), notable developments have also occurred in Russia’s fledgling QANGO sector. Despite nearly tripling in size during the past 15 years (75 percent of the 23 QANGO entities outlined earlier were established since 2008), the Russian QANGO sector is growing increasingly reliant on the state to deliver in complex emergencies in joint missions.

Table 6. Timeline of when most of the Russian QANGOs in this report were established, compared to when the top 20 most-funded U.S. NGOs were established

| Year of establishment |

Name of entity |

Nationality of NGO |

| 1932 |

Save the Children USA |

U.S. |

| 1933 |

International Rescue Committee |

U.S. |

| 1939 |

Plan International USA |

U.S. |

| 1943 |

Catholic Relief Services |

U.S. |

| 1945 |

CARE USA |

U.S. |

| 1947 |

Lutheran World Federation |

U.S. |

| 1950 |

World Vision |

U.S. |

| 1952 |

CHF International (Global Communities) |

U.S. |

| 1956 |

Adventist Development and Relief Agency (ADRA) |

U.S. |

| 1970 |

Samaritan's Purse |

U.S. |

| 1970 |

Oxfam USA |

U.S. |

| 1971 |

Medicines Sans Frontier |

U.S. |

| 1972 |

Concern USA |

U.S. |

| 1976 |

Habitat for Humanity |

U.S. |

| 1979 |

Action Against Hunger |

U.S. |

| 1979 |

Americares |

U.S. |

| 1979 |

Mercy Corps |

U.S. |

| 1984 |

International Medical Corps |

U.S. |

| 1987 |

Partners in Health |

U.S. |

| 1990 |

Relief International |

U.S. |

| 1992 |

St. Andrew's the First Foundation |

Russian |

| 1997 |

Combat Brotherhood Veterans Association |

Russian |

| 2003 |

Imperial Orthodox Palestine Society (NGO registration) |

Russian |

| 2003 |

St. Paul the Apostle Foundation |

Russian |

| 2004 |

Children of Russia: The Future of the World Foundation |

Russian |

| 2005 |

Fair Aid Foundation |

Russian |

| 2008 |

Public Diplomacy Fund |

Russian |

| 2008 |

Russian Union of Rescuers |

Russian |

| 2010 |

Russian Humanitarian Mission |

Russian |

| 2011 |

Arab Diaspora NGO |

Russian |

| 2012 |

Russian Serbian Humanitarian Center |

Russian |

| 2013 |

Eurasian People's Union |

Russian |

| 2013 |

Hayat Foundation |

Russian |

| 2014 |

RUSSAR |

Russian |

| 2014 |

Yelitsa Orthodox Social Network |

Russian |

| 2015 |

Russian Armenian Humanitarian Center |

Russian |

| 2015 |

Forty Forties Foundation |

Russian |

| 2016 |

Hurry to Good Foundation |

Russian |

| 2018 |

Znanie Russian Regional Charity |

Russian |

| 2019 |

Russian Humanitarian Volunteer Corps |

Russian |

Information taken from the websites and social media pages of the entities depicted.

Source: courtesy of the author.

The data collection for this study shows that with the exception of Ukraine, where independent Russian QANGO aid deliveries made up just more than one-fifth of all aid operations (22 percent), the recipients of Russian FHA identified here saw a constrained QANGO sector that made up on average about 2 percent of aid delivery. Moreover, at least nine Russian QANGOs exclusively rely on state institutions to conduct joint aid operations abroad, further underscoring the reliance of the QANGO sector on the state.

The inexperience of Russian QANGOs in different complex emergencies likely contributes to their limited capacity and reliance on state institutions. The fact that many QANGOs are heavily influenced by the state through their leadership, who are often close to or within the Russian government, is also likely a factor as well. Although it is unclear why Russian QANGOs are able to operate more freely in Ukraine than the other three contexts, it does show that when given a chance, the QANGO sector can fill an important gap in a Russian humanitarian response.

Conclusion

Through analyzing quantitative open-source data from 40 Russian entities who have delivered aid 5,014 times to Georgia, Ukraine, Syria, and Nagorno-Karabakh during the past 15 years, this study provides scholars and practitioners a window into Russia’s current FHA activities. Indeed, five key nuances about Russia’s FHA capability have been revealed that show that Russian aid is heavily influenced by the state, is symbolic, and is urban focused; has limited capacity to conduct more than one significant country response at a time; and is influenced by the context to which Russia is responding.

As this study has a relatively narrow focus on just four contexts, widening its focus in the future could provide even more valuable information about Russia’s FHA. Further research could include collecting open-source data about Russia’s FHA actions in other complex emergencies around the world and comparing those findings with Russia’s actions in Georgia, Ukraine, Syria, and Nagorno-Karabakh. Likewise, collecting open-source data about Russia’s foreign disaster relief (FDR) activities could bring to light useful distinctions between Russia’s FHA and FDR capabilities. Comparing Russia’s FHA and FDR activities to those of the United States and other countries could also prove worthwhile, especially as the world moves into an era of strategic competition that could see the humanitarian sector become a frontier of any future contest.42

It is still too early to tell how Russia’s latest invasion of Ukraine and the strong international reaction toward it may affect Russia’s FHA capacity in the future. However, measures such as international sanctions against Russia as well as Russia’s growing political isolation are unlikely to moderate the heavy state influence in Russia’s shallow aid provision and may in fact contribute to a further strengthening of these traits in Russian FHA moving forward. These actions may also cause Russia’s FHA to transform away from the two configurations outlined in this study to a more muted, resource-limited response.43 If this happens, the wider UN-led humanitarian community’s collaborative, principled, and people-focused approach will be even more important to support.

Endnotes

- “Ukraine Conflict Updates,” Institute for the Study of War, accessed 28 March 2022.

- “Roundup: What Ukraine’s Humanitarian Crisis Looked Like before the Russian Invasion,” New Humanitarian, 24 February 2022; “Ukraine,” U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID), accessed 28 March 2022; and “The United States Announces Additional Humanitarian Assistance to Ukraine,” USAID, 27 February 2022.

- “Priests to Establish Duty at Temporary Accommodation Centers for IDPs from Ukraine,” Russian Orthodox Church, 19 February 2022.

- Peter Roudik and Nerses Isajanyan, “Russian Federation: Regulation of Foreign Aid,” in Regulation of Foreign Aid in Selected Countries (Washington, DC: Law Library of Congress, 2012), 205–17; and Martin Russell, Russia’s Humanitarian Aid Policy (Strasbourg, France: European Parliamentary Research Service, 2016).

- Russia’s Participation in International Development Assistance: Concept (Moscow: Ministry of Finance of the Russian Federation, 2007); and Concept of the Russian Federation’s State Policy in the Area of International Development Assistance (Moscow: Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Russian Federation, 2014).

- Foreign Policy Concept of the Russian Federation (Moscow: Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Russian Federation, 2016); and Foreign Policy Activity State Programme (Moscow: Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Russian Federation, 2021).

- “Primakov Evgeny,” Rossotrudnichestvo, accessed 15 November 2021; “Dmitry Vadimovich Sablin,” Russian Combat Brotherhood Veterans Organization, accessed 15 November 2021; “Very Reverend Hieromonk Stefan Igumnov,” Kaiccid Dialogue Center, accessed 15 November 2021; and “Sergey Kuzhugetovich Shoigu,” Ministry of Defense of the Russian Federation, accessed 15 November 2021. Rossotrudnichestvo is an agency within the Russian Ministry of Foreign Affairs and is officially known as the Federal Agency for the Commonwealth of Independent States Affairs, Compatriots Living Abroad, and International Humanitarian Cooperation. Despite its name, Rossotrudnichestvo is largely engaged in building cultural relations and promoting Russian language learning rather than delivering humanitarian assistance as the West would recognize it. Rossotrudnichestvo is akin to the United Kingdom’s British Council. The Interreligious Working Group is coalition of Russian religious associations that have formed a council to cooperate on delivering humanitarian aid around the world. It is chaired by the Office of the President of the Russian Federation. The Ministry of Emergency Situations of the Russian Federation (EMERCOM) is officially known as the Ministry of Civil Defense, Emergencies, and the Elimination of Consequences of National Disasters of the Russian Federation. EMERCOM is akin to a combination of the United States’ Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) and U.S. National Guard units that respond to natural disasters.

- The data collection period for the Georgian regions of Abkhazia and South Ossetia begins in November 2006, which is when the first reported Russian aid delivery in this study was identified and which is almost two years prior to Russia’s invasion of Georgia (August 2008). The data collection period for Ukraine begins in March 2014, which is when the first reported Russian aid delivery in this study was identified and which is one month after Russia’s invasion of Crimea (February 2014) and one month before the Donetsk and Luhansk regions declared independence from Ukraine (April 2014). The data collection period for Syria began in March 2012, which is when the first reported Russian aid delivery in this study was identified and which is about three and a half years prior to when Russia officially intervened in the Syrian Civil War (September 2015). The data collection period for Nagorno-Karabakh begins in November 2020, which is when the first reported Russian aid delivery in this study was identified and which is the same month that Russia brokered a ceasefire between Azerbaijan and Armenia. The data collection period for all four contexts ends in November 2021.

- Russia’s Participation in International Development Assistance; Gerda Asmus, Andreas Fuchs, and Angelika Müller, “Russia’s Foreign Aid Re-emerges,” AidData, 9 April 2018; “Russian Emergencies Ministry Team Continues Rescue Operations in Nepal,” Ministry of Emergency Situations of the Russian Federation, 30 April 2015; and “Russian Emergencies Ministry’s Jet Delivers More Relief Goods in Yemen,” Ministry of Emergency Situations of the Russian Federation, 24 July 2017. Cultural diplomacy in Russia involves using academic, artistic, and language exchanges to build positive views of Russia. For more about Russian views on cultural diplomacy, see “Yevgeny Primakov: ‘Enough Strings for Us in Humanitarian Policy!’,” New News, 8 April 2019; and Andrew D’Anieri, “Peace at Last?: Assessing the Ceasefire in Nagorno-Karabakh,” New Atlanticist (blog), Atlantic Council, 13 November 2020. Although Russian involvement in international peacekeeping missions date back to the 1960s, it was not until the establishment of specialized MOD humanitarian centers in Syria and Nagorno-Karabakh in 2016 and 2020, respectively, that the notion of peacekeeping become clearly incorporated with Russia’s concept of humanitarian cooperation rather than as a separate activity.

- “Yevgeny Primakov: ‘Enough Strings for Us in Humanitarian Policy!’.”

- Concept of the Russian Federation’s State Policy in the Area of International Development Assistance. The following definitions are from the UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (UNOCHA) and USAID, two of the world’s premier aid agencies. UNOCHA defines humanitarian assistance as “seek[ing] to save lives and alleviate suffering of people affected by a crisis, be it a natural disaster or conflict. It focuses on short-term emergency relief, to provide basic life-saving services that are disrupted due to the crisis. Humanitarian assistance is needs-based, with the sole purpose to save lives and reduce human suffering that originated from a crisis. This is distinct from development programmes, which focus on a long-term improvement of the social and economic situation and work primarily through the means of capacity building within a country.” See United Nations Humanitarian Civil-Military Coordination: Guide for the Military, 2.0 (New York: UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs [UNOCHA], 2017), 7. USAID defines humanitarian assistance as “saving lives, alleviating human suffering, and mitigating the economic and social impact of disasters. It recognizes the links between independent humanitarian action and broader aid policies. In the context of this policy, humanitarian action includes protection and disaster assistance, disaster risk reduction, and efforts to build resilience.” See Office of U.S. Foreign Disaster Assistance Policy for Humanitarian Action (Washington, DC: USAID, 2015), 2.

- Concept of the Russian Federation’s State Policy in the Area of International Development Assistance, 3.

- The remining seven goals of the 2014 concept involved 1) “influencing global processes in order to form a stable and just world order based on universally recognized rules of international law and partnership relations among States”; 2) “providing support for international efforts and initiatives to improve the transparency, quality and effectiveness of international development assistance, and active participation in the development of common approaches to the implementation of agreed decisions in that area”; 3) “strengthening a positive image of the Russian Federation and its cultural and humanitarian influence in the world”; 4) “establishing good-neighbourly relations with neighbouring States, contributing to the elimination of existing and potential hotbeds of tension and conflict, sources of illegal drug trafficking, international terrorism and organized crime, especially in the regions neighboring the Russian Federation, and preventing their occurrence”; 5) “facilitating integration processes in the space of the Commonwealth of Independent States”; 6) “promoting good governance based on the principles of the rule of law and respect for human rights in recipient States and encouraging self-reliance of the governments of those States in addressing emerging problems, provided they comply with the international legal principle of States’ responsibility for the internal and external policy they pursue towards both their citizens and the international community”; and 7) “facilitating the development of trade and economic cooperation.” See Concept of the Russian Federation’s State Policy in the Area of International Development Assistance, 3–4.

- OCHA on Message: Humanitarian Principles (New York: UNOCHA, 2012).

- Antonio Donini, NGOs and Humanitarian Reform: Mapping Study Afghanistan Report (London: Department for International Development, 2009, 1; and Mary B. Anderson, Dayna Brown, and Isabella Jean, Time to Listen: Hearing People on the Receiving End of International Aid (Cambridge, MA: CDA Collaborative Learning Projects, 2012), 51.

- Foreign Policy Concept of the Russian Federation, 4.

- For example, in a 2021 Politico Magazine article, it is suggested to hold Arria formula meetings at the UN that “would allow the United States to give a platform to vital evidence of the importance of humanitarian deliveries” as a way to leverage against Russia’s actions. However, this suggestion does not take into account the way Russia broadly conceives and defines FHA, which does not prioritize how aid can save lives and alleviate suffering. See Charles Lister and Jeffrey Feltman “How Putin Is Starving Syria—and What Biden Can Do,” Politico Magazine, 24 March 2021.

- A visual example of this support from USAID can be found at “Ongoing USG Humanitarian Assistance: Syria—Complex Emergency,” USAID, accessed 15 November 2021.

- “What Is the Cluster Approach?,” UNOCHA, 31 March 2020.

- “Good Humanitarian Donorship Initiative,” GHDInitiative.org, accessed 15 November 2021.

- Jonathan Robinson, “Russian Aid in Syria: An Underestimated Instrument of Soft Power,” MENASource (blog), Atlantic Council, 14 December 2020.

- Gerda Asmus, Andreas Fuchs, and Angelika Müller, BRICS and Foreign Aid, Working Paper no. 43 (Williamsburg, VA: AidData, 2017), https://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3027620.

- EMERCOM and MOD entities have delivered 82 percent of Russia’s reported aid in Georgia, Ukraine, Syria, and Nagorno-Karabakh, totaling 4,116 out of 5,014 deliveries.

- Ruslan Trad, “In Its Battle for Influence, Russia’s Soft Power Strategy Seeks to Reshape Syria’s Future,” New Arab, 15 April 2021.

- Marika Sosnowski and Paul Hastings, “Exploring Russia’s Humanitarian Intervention in Syria,” Fikra Forum (blog), Washington Institute for Near East Policy, 25 July 2019.

- Jonathan Robinson, “Five Years of Russian Aid in Syria Proves Moscow Is an Unreliable Partner,” MENASource (blog), Atlantic Council, 8 June 2021.

- “Russian Emergencies Ministry Plane to Airlift Medical and Biological Laboratory to Guinea,” Ministry of Emergency Situations of the Russian Federation, 21 August 2014; “On the Meeting of the President of the Republic of Guinea Alpha Conde with the Specialists of Rospotrebnadzor,” Federal Service for Surveillance on Consumer Rights Protection and Human Wellbeing, 17 October 2014; and “Meeting with President of the Republic of Guinea Alpha Conde,” Federal Service for Surveillance on Consumer Rights Protection and Human Wellbeing, 5 March 2015.

- “On Signing Memorandums with the Republic of Guinea,” Federal Service for Surveillance on Consumer Rights Protection and Human Wellbeing, 5 November 5, 2015; “Meeting with President of the Republic of Guinea Alpha Conde”; “On the Work of Rospotrebnadzor Specialists in the Republic of Guinea,” Federal Service for Surveillance on Consumer Rights Protection and Human Wellbeing, 15 April 2015; “Head of Rospotrebnadzor Anna Popova Opened Advanced Training Courses for Specialists of the Republic of Guinea at Pasteur Research Institute,” Federal Service for Surveillance on Consumer Rights Protection and Human Wellbeing, 7 December 2015; and “On Russian-Guinean Cooperation in the Fight against Infectious Diseases,” Federal Service for Surveillance on Consumer Rights Protection and Human Wellbeing, 14 January 2016.

- “Since the Beginning of the Year 2009, the EMERCOM of Russia Carried out 14 Humanitarian Operations,” Ministry of Emergency Situations of the Russian Federation, 3 June 2009.

- The remaining portions of aid delivery in Georgia and Ukraine were conducted by 10 other state actors and 11 QANGOs, which delivered the remaining 26 percent (226 deliveries) and 16 percent (138 deliveries), respectively. A further 2 percent (16 deliveries) of activity were joint missions between state actors and QANGOs. The remaining portions of aid delivery in Syria and Nagorno-Karabakh were conducted by 12 other state actors and 10 QANGOs, which delivered the remaining 7 percent (285 deliveries) and 2 percent (65 deliveries) of aid, respectively.30 A further 4 percent (184 deliveries) were joint missions between state actors and QANGOs.

- For an example of how Russia views Ukraine, see Valery Konyshev and Alexander Sergunin, “Russian Views on the [Ukraine] Crisis,” Valdai Discussion Club, 11 November 2014.

- Andrey Kortunov and Julien Barnes-Dacey, “First Aid: How Russia and the West Can Help Syrians in Idlib,” Russian International Affairs Council, 14 April 2021.

- It is recognized that EMERCOM’s position as lead responder in Ukraine in 2014 comes after Shoigu was promoted to minister of defense in 2012, which largely discounts this theory. However, in addition to the geographical sensitivity of intervening in eastern Ukraine, another potential explanation as to why the MOD was not involved as the lead aid agency in Ukraine was that Shoigu may have been otherwise engaged in implementing a transformation of the Russian military and doctrine in 2013 and 2014 during the lead-up to Russia’s invasion of eastern Ukraine.

- A further 518 locations could not be geolocated and were not counted in the total number of communities or depicted on maps in this report.

- Jerome J. Lademan and J. Alexander Thew, “Objective Metropolis: The Future of Dense Urban Operational Environments,” Modern War Institute at West Point, 2 June 2017.

- Diane Archer, “The Future of Humanitarian Crises is Urban,” International Institute for Environment and Development, 16 November 2017.

- Robinson, “Russian Aid in Syria.”

- “Bulletin for Centre for the Reception, Allocation and Accommodation of Refugees,” Ministry of Defense of the Russian Federation, 12 July 2018; and “About OCHA Syria,” UNOCHA, accessed 15 November 2021.

- “Syria: United Nations Aid Supplies Arrive in Besieged Areas of Deir-ez-Zor City,” UNOCHA, 15 September 2017.

- “Middle Euphrates River Valley, Syria,” International Crisis Group, 12 November 2021.

- Kortunov and Barnes-Dacey, “First Aid.”

- “RAND Strategic Competition Initiative,” Rand National Security Research Division, accessed 28 March 2022.

- One response model is that which is led by EMERCOM with QANGO support, as has been seen in Georgia and Ukraine. Another response configuration that which is led by Russia’s MOD through specialized centers, as has been applied in Syria and Nagorno-Karabakh.