Anthony Roney II

https://doi.org/10.21140/mcuj.20231402007

PRINTER FRIENDLY PDF

EPUB

AUDIOBOOK

Abstract: This article outlines the policy suggestion for Moldova and Ukraine to bilaterally invade the Pridnestrovian Moldavian Republic (PMR) to strengthen their respective national security interests. The article examines the historical background of Moldova and the PMR, otherwise known as Transnistria, to provide context for the relationship between the two actors. As the PMR has acted as a tool of covert foreign influence for Russia, it is recommended that Moldova and Ukraine act now to eliminate the risk of Russian influence and interference from posing a larger threat in the future for these states. This article conveys the reasons, risks, and benefits for a joint invasion of Transnistria. It details the justifications for such a proposed action, but it also outlines its possible consequences. The policy suggestion is further justified when viewed under the lens of defensive realism, contrasted with Russia’s aggressive expansionist actions under President Vladimir Putin. Finally, the article gives basic strategic and tactical suggestions on how to accomplish this task.

Keywords: Moldova, Ukraine, Transnistria, Russia, frozen conflicts, military operations, defensive realism, offensive realism, foreign influence

Since 24 February 2022, one thing has become abundantly clear within the geopolitical landscape: for whatever reason, Vladimir Putin’s Russia has confirmed a pattern of revanchist imperialism and aggression. This hostile behavior to physically interfere or reclaim the states that were once solely under the Russian sphere of influence has been fully demonstrated by the Russian invasion of Ukraine. With its seemingly fragile democracy and capacity for corruption, followed by a half-hearted protest by the West after Russia’s invasion of Ukrainian Crimea, the country had been deemed an attractive target. However, time was a larger factor than anyone could have guessed. From the moment of the invasion of Crimea to the attack on Kyiv, Ukraine had militarily prepared far better than most of the world had expected. Repelling Russian forces from the Ukrainian capital, in addition to successful counteroffensives taking swaths of Russian-occupied territory in the east, has put a halt to President Putin’s plan of reclamation. This failure has halted even further and far easier steps to this plan, the next being the subjugation of Moldova.

This article will assert the policy suggestion that Moldova and Ukraine should jointly invade Transnistria while Russia is waging its war against Ukraine. Providing an initial background, the article will convey the reasons why both Moldova and Ukraine would have sufficient justifications to gain control of the region. This claim will be analyzed from a practical standpoint and supplemented through a theoretical lens of defensive realism for both allied countries while being contrasted to the aggressive expansionist actions of the Russian Federation under President Vladimir Putin. The article will also state basic recommendations on how they could achieve this goal at the strategic and tactical levels. Counterpoints to explain why an invasion would be ill-advised at this moment will also be necessary to understand the related limits of such an operation with its aftermath and to properly weigh options.

Background

Moldova, a former Soviet republic and one of the poorest countries in Europe, has been at the forefront of Russian interference since its very existence. This is because of the presence of the internationally unrecognized (not even by Russia) breakaway state of fervent Russia supporters within its territory, Transnistria. This region, as with much of the surrounding area, was defined by empires and kingdoms changing hands over the centuries. Before 1792, modern-day Moldova—the regions of Bessarabia and Transnistria—had largely consisted of a Romanian-speaking population (with estimates being around 95 percent in 1810).1 Following the 1792 Treaty of Jassy, the Ottoman Empire ceded the area between the Dniester and Bug Rivers to the Russian Empire, while later expanding into Bessarabia in 1812.2 During this period, the Russian Empire consolidated political and resource control by enacting Russification policies while importing and colonizing Ukrainian and Russian immigrants, thereby diluting Romanian-speaking concentrations, especially in Transnistria.3

After the onset of the Russian Revolution in 1917, all Russian-controlled Bessarabian areas voted in favor for independence, which was subsequently unified with the Romanian Kingdom in 1918.4 Following this, Bolshevik officials declared the areas of Transnistria along with some areas of southwestern Ukraine to be the Moldavian Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic (MASSR) in 1924, an autonomous republic that acted as an oblast within the Ukrainian SSR.5

With the burgeoning of power in the Soviet Union and Nazi Germany, the two nations sought to delineate their respective interests in Europe and declare nonaggression with the procurement of the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact.6 In a secret additional protocol of the pact, the USSR claimed Bessarabia, which was agreed on by Nazi Germany.7 In doing so, Adolf Hitler effectively ceded Romanian territory, which was also a fascist nation, to Joseph Stalin for when the time came to invade their neighbors. This invasion came the following year in June 1940 along with the parallel invasions and occupations of the Baltic states by the Soviets. The subsequent emplacements of the various Soviet republics, including the Moldavian SSR, solidified a hegemonic influence for Russia within the region for the rest of the twentieth century. After acquiring the area from Romania, the Soviet Union realigned the territory to include a Russian-speaking Soviet population on the eastern side of the Dniester River (the former MASSR). This new influence helped assimilate the territory into Soviet uniformity via population restructuring and further Russification policies.8

Consequentially, however, the drastic instability and repressive policies within these areas, especially during and around World War II, led to war crimes, pogroms, and genocidal acts to become common occurrences. Nazis, Soviets, Romanians (all that led invasions through Moldova) and their respective sympathizers each committed atrocities to maintain control through fear and wipe out ideological or ethnic groups that were inimical to their own. Incidents like mass deportations and famines by Soviets against Romanians, massacres of Jews and Russian sympathizers by Axis soldiers in Transnistria, or the Jewish pogrom of 1903 in Chişinău during the Russian Empire era have likely led many Moldovan citizens to entrench their political identities with either a “safety from Russia” stance or “safety with Russia” stance.9

When perestroika began to take effect across the Soviet Union, nationalist movements began growing rapidly and Moldovans were no different.10 However, Transnistrians saw this as the writing on the wall for their separation from Russia, which led to major protests from Tiraspol, condemnation of independence movements, and minor military engagements.11 After the fall of the Soviet Union in 1991 and Moldova’s recognition by the United Nations in 1992, tensions between the Republic of Moldova and the already self-proclaimed Pridnestrovian Moldavian Republic (PMR) escalated to a brief war in March 1992.12 Hastily recruited forces from both sides fought over the region until Russian forces came to the assistance of the PMR to grant de facto autonomy to the breakaway state.13 Elements from the Russian 14th Army that arrived in Moldova to intervene would stay as peacekeepers for Transnistria.14

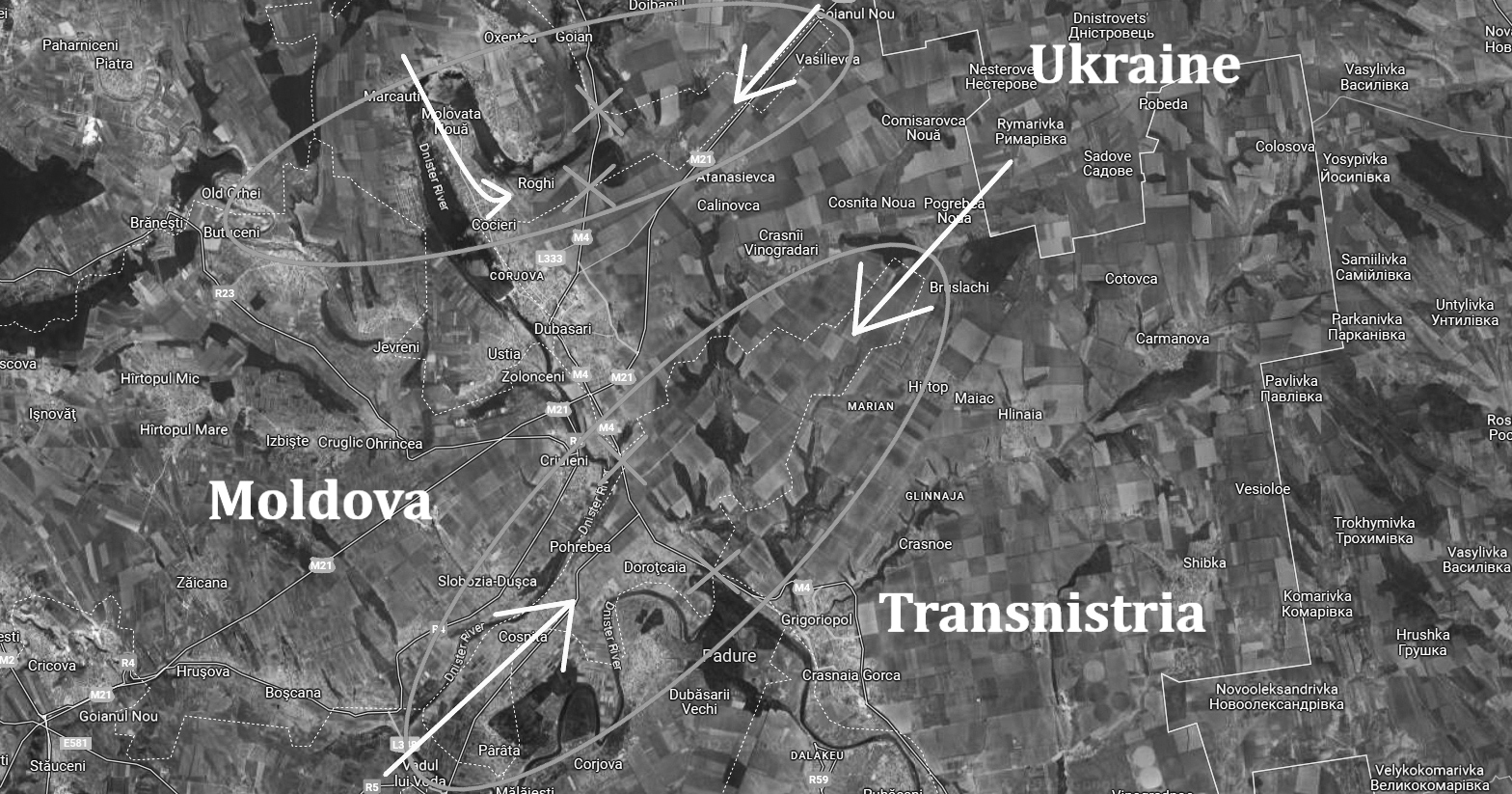

Map 1. De facto and de jure territorial control of Transnistria

Note: this map is from a non-English source; 1) part of the core of Moldova (area that is not disputed) is included by the Moldovan government into a common district (outside of the Transnistrian autonomous region) with some Transnistrian territories.

Source: Sidorov et al., Transnistria după Asybaris, adapted by MCUP.

From here, the situation between Transnistria and Moldova has been classified as a frozen conflict, where there is neither a hot war nor resolution between the two actors. Sentiments again solidified to the point of noncooperation. Relying on older methods for political coercion, Igor Smirnov, then president of Transnistria, had even referred to the government in Chișinău as a “fascist state” and “war criminals.”15 Furthermore, Russia’s involvement with the two actors has implicated its parallel foreign policy to other regional actors. Indeed, Russia does not recognize Transnistria as an independent nation, but it does treat it unofficially as a legitimate government, one that is entirely reliant on Russia. It even supplies the breakaway state with free natural gas (Russia still claims this as an accrued debt of the Chișinău government currently estimated at about $9.5 billion that will likely never be paid), where it is resold by the breakaway state’s power plant and steel plant to Chișinău to generate half of Tiraspol’s budget.16 To say that Transnistria is reliant on Russia for its existence would be a gross understatement. So, why would Russia be willing to do such business with a state it does not even recognize as actually existing? One word: interference.

Why Now for Moldova?

The Russian government sees Transnistria the same way as Stalin did so many years ago. The nonrecognition of the region exposes both Moldova and Ukraine to multiple vulnerabilities from Russian-aligned actors. First, the nonrecognition allows Russia to export influence onto the Moldovan government via numerous methods. Even in the course of writing this article, Russian interference has increased perceptively. Allegedly, the Russian Federal Security Service (FSB, an intelligence service) has been funding anti-Western Moldovan politicians to undermine the current pro-Western government.17 Further external pressures from Russia have imposed greater political corrosion within Moldova.

While both Moldovan and Transnistrian figures have publicly called for peace between the two during the war in Ukraine, Transnistrian authorities and their proxies have consistently challenged and sought for destabilization in Chişinău to gain a better foothold in national politics. In essence, they have acted as a tool for Russian interests. Transnistria’s de facto sovereignty acts as a cancer to Moldova’s prosperity and is a direct threat to their security.

If history is any indicator, without powerful friends, Moldova is a very vulnerable country. Moldova’s end goal should be to maximize their security with legitimate security guarantees and economic potential provided by the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) and the European Union (EU). The existence of the Pridnestrovian Moldavian Republic is the ultimate yet still conquerable hurdle to these goals. It should be noted that there is no immediate threat of invasion by Transnistrian or Russian forces from the PMR into Moldova or Ukraine. However, even if they fail entirely in their current invasion of Ukraine, the security threat of Russian interference, with time, would continue to grow with further embedding and actions taken by Russian actors under the protection and aid of Transnistrian figures. With a joint offensive into Transnistria, these problems can be mitigated before they even occur.

Energy Security

One of the more precarious vulnerabilities of Moldova is its energy dependence on the more industry-capable Transnistria and its natural gas dependency on Russia’s state-owned Gazprom. Though the Chişinău government has weaned off of liquid natural gas (LNG) directly from Russia, it still heavily relies on energy derived from Russian gas imports.18 Transnistria, which supplies the entire nation with 80 percent of its electricity, depends entirely on Russia for its liquid natural gas.19 After Moldova’s drastic shift from neutrality in favor of the West in 2022, Russia’s state-owned gas company, Gazprom, cut supply to Moldova and, consequentially, Transnistria. Russia’s energy blackmailing of Moldova has forced the country to resort to ad hoc more expensive methods of gas imports to wean off its once 100-percent reliance on Russian energy products.20 Such methods have included purchasing LNG supply from Romanian and Greek energy companies and storing winter gas reserves in Romania and Ukraine.21 Other alternative natural gas markets such as Azerbaijan or Turkey have either been solicited or just recently used via reverse-flowed pipelines like the Trans-Balkan Pipeline.22 Additionally, in recent years the construction and designated expansion of the Iaşi-Ungheni-Chişinău Interconnector Pipeline has allowed direct access to the Romanian natural gas supplies.23

However, even with the beginning of these changes, Moldova has still simply been at the mercy of Russia’s predatory energy blackmailing. Much of these mitigations require much more expensive transportation costs and require either modifications to current pipelines or entirely new infrastructure including power plants to be constructed.24 This also makes Moldova vulnerable to Transnistrian officials in the long term.

Energy security is one of the foremost problems facing Moldovan society. Though an offensive will likely risk losing the primary natural gas supplier to the country, Gazprom, it is argued that this will ultimately be more beneficial than remaining at the status quo. Without an intervention in Transnistria during the war in Ukraine, Moldova will continue to be subject to predatory blackmailing that will likely eventually destabilize the country enough to swing back into the Russian sphere of influence. Although there is a risk of facing an energy crisis caused by a natural gas embargo from Russia after an intervention in Transnistria, the negatives of this scenario would likely be mitigated with urgent EU and American assistance and cooperation, given their security interests in the area. If an intervention in the PMR is not undertaken, Western allies may view their future efforts to aid Moldova against Russian influence as a more exhaustive, never-ending option. Conversely, a one-time crisis that is more intense but shorter in duration may be a preferable alternative. Moldovan officials would be wise to choose the option that would give them more support from the West.

With full administrative control over Transnistria, contracts and agreements with predatory Russian energy companies would likely be either severely damaged or terminated entirely. Additionally, Russian ownership of energy companies like the dominant MoldovaGaz (Gazprom owns 50 percent) would likely also be nullified.25 This would highly destabilize the economy of Moldova, but it would allow for full autonomy in a short period of time. Leverage could be swung much more in favor of Moldova when new energy contracts are written once free from Russian ownership of companies. If the intervention takes place in the appropriate window of time, which will later be discussed, this could allow enough time for Moldova to prepare for an emergency energy crisis. Drastic as this would be, once the crisis has passed and security concerns have resided, it is highly likely that economic growth would rise to unprecedented levels with Moldova in full control of its own destiny.

Interference and Diplomatic Pressures

From these pressures, in conjunction with the Russian-caused energy crisis, the cost of living has increased significantly.26 This has led to pro-Russian constituents protesting and solely blaming the pro-European Moldovan government.27 However, allegedly, these protests have been accused of being organized and paid for by Russian-influenced politicians like Ilan Shor.28 Shor, a spearheading figure for Russian influence in Moldova, has been sanctioned by the United States and has been convicted and sentenced to 15 years in prison for fraud and money laundering amounting to approximately $1 billion.29

According to numerous officials, including Ukrainian president Volodymyr Zelenskyy and Moldovan president Maia Sandu, there is even a plot to overthrow the government in a coup in order to keep Moldova under the control of Russia.30 In March 2023, an FSB document was obtained and released to the public outlining a 10-year plan by the Kremlin to garner more influence within Moldova.31 It sought for the “creation of stable pro-Russian groups of influence in the Moldovan political and economic elites” as well as “the formation of a negative attitude towards NATO in Moldovan society.”32

Other grievances include Russian missiles flying through Moldovan air space or public threats from senior Russian officials calling them the “next Ukraine” or that attempting to join NATO “may lead to its destruction.”33 Even former Russian president Dmitry Medvedev said that Moldova did not exist as a country as “local leaders sold it to Romania,” among other threatening statements.34 It is clear here what designs Russia has for Moldova. Transnistria is its tool to fuel antidemocratic and anti-Western sentiments. Although Russia is often blamed for causing instability in Moldova, some actors accused of being under its influence point fingers at pro-Western officials and organizations. Given Transnistria’s role as an institutional bastion of Russian influence, it is crucial to eliminate such institutions that wreak havoc then manipulate Moldova’s citizens into thinking otherwise.

Organized Crime and Administrative Control

Transnistria is essentially a legal black hole that allows for organized criminal activities, supported by Russian corruption, to spread throughout neighboring countries and even neighboring continents. In 2004, Dr. Mark Galeotti summarized the Transnistrian criminal community as being “characterised by a distinctive and dangerous mix of old-style corruption and an entrepreneurial zeal to embrace the opportunities offered by today’s global underworld, the enclave therefore poses the outside world some serious criminal and security challenges.”35 He highlights that state organizations designed to combat criminal activities, like the Ministry of State Security (Ministerstvo Gosudarstvennoy Bezopasnosti or MGB), act as extensions and enforcers of organized crime groups or figures that often include national political leaders or businessmen.36 Numerous studies and government publications have indicated that these problems have continued into the present, with certain exceptions during the war in Ukraine.

The PMR has served not only as a source of corruption and illicit activities, items, or substances but also as an effective intermediary highway for these in multiple directions. Many Transnistrian criminals have developed extensive intertwined alliances with other Russian, Ukrainian, and Moldovan criminal groups to traffic their illegal products.37 There is a vast range of these products, as well. Traffickers from Transnistria, Russia, Moldova, and Ukraine have been arrested and convicted of making deals and smuggling uranium along with other radioactive materials capable of being weaponized.38 The Transnistrian gray area of smuggling has allowed the breakaway state to serve as a base for the entire region’s trafficking business.

Transnistria has been identified as a major source of weapons, arms, and ammunition for trafficking around the world, with the Cobasna ammunition depot serving as a significant hub for illegal trade.39 The breakaway state is also used as an exporting point for illicit arms to Africa and the Middle East.40 Notably, Viktor Bout, the infamous “merchant of death,” played a central role in the illicit arms business operating in Transnistria.41 These characters further exemplify the disruption Russia causes for Moldovan and Ukrainian efforts to maintain stability within their countries. Many of these criminals find refuge in Russia. While many of the key players originate from or find refuge in Russia, Kremlin authorities have consistently ignored or rejected international efforts to bring them to justice.42 These criminal organizations bring another facet of instability to target states that cannot be refused by the Russian government.

The PMR has also served as a major source and avenue for human trafficking.43 While the Republic of Moldova is also a source of human trafficking, there have been growing efforts to combat these crimes in recent reports from the U.S. State Department. While falling behind in some areas, the Moldovan government has taken measures such as convicting more traffickers, identifying significantly more victims, creating a national action plan with dedicated funding, providing protection programs, and participating in bilateral work agreements with EU counterparts against human trafficking.44

This is, again, in contrast to the PMR, outside of Moldovan administrative control, where victims from Eastern Europe (especially Ukrainians and Moldovans) are either exploited for sexual or working purposes.45 The U.S. State Department states that

the breakaway region of Transnistria remains outside the administrative control of the Government of the Republic of Moldova; therefore, Moldovan authorities are unable to conduct trafficking investigations or labor inspections, including for child labor and forced child labor, in the region. Furthermore, de facto authorities in Transnistria do not communicate their law enforcement efforts to authorities in Moldova.46

Again, due to corruption and cooperation from PMR officials, human trafficking will continue without taking control of administrative capabilities within Transnistria.

Conducting a coordinated offensive into Transnistria would immediately crack down on these smuggling and organized criminal operations based in Transnistria. By granting full prosecutorial jurisdiction to the legal Moldovan government and ousting PMR officials who protect or aid in these operations, law enforcement could gain a foothold and begin to grow over time. Even more so, it would allow European Union officials and nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) to penetrate the area in an unprecedented manner to assist in combating these criminal activities.

Given Moldovan and Ukrainian aspirations to join NATO and the EU, these criminal practices will continue to infect and likely spread to corrupt both countries’ officials in a way that would otherwise make it impossible to join said organizations. Without elimination of the base of operations and thoroughfare for illegal activities in Transnistria, their prospects and goals for legitimate accession and stability will continuously be forestalled without action.

Strategic Implications and Time

There are more immediate factors on why it is necessary to launch an offensive sooner rather than later. With the Russian military being wholly occupied in eastern Ukraine, the Russian response to an allied offensive into Transnistria would be quite limited in its capability. Not only are Russian military resources being spread thin, but they are also being reduced daily on the front in Ukraine. However, this is not even the most pressing issue for the Russians if they want to attempt a defense of Transnistria. First, they would have to effectively conduct either an amphibious assault landing in the Odesa Oblast (and most likely have to take the city in the process), then maintain a narrow ground line of communication through to Transnistria or conduct a far-reaching (approximately 563 kilometers) logistically sustained offensive through western Ukraine from Belarus. Both of these options, based on previous actions in the war in Ukraine, are extremely unviable for the Russian military, who consistently opt for attritional warfare with incremental gains rather than maneuver offensives and have had very little success in general.47 Ground warfare to relieve Transnistria is virtually impossible for the Russian military.

Essentially, the only way to respond to a seizure of Transnistria would be through long-range missile strikes, the same kind that are already seen in Ukrainian cities. While this would be devastating for many Moldovans, Russian resources and their targets are, as mentioned, already vastly dispersed. As Russians are targeting numerous civilian, governmental, and military infrastructural locations across every oblast of Ukraine, potential targets in Moldova would most likely have a similar or lesser level of intensity of missile strikes as western Ukrainian areas.

Moldova has significantly increased its military spending in recent years and is currently developing its military capabilities. This is presumably in response to Russian aggression in Ukraine. On multiple occasions, Moldovan officials have stated the imperativeness for air-defense systems to be the focus of these expenditures, undoubtedly in a response to Russian choices for offensive capabilities in Ukraine (air strikes).48 It should be noted, air-defense systems not only counter missiles but also military aircraft. However, even Moldovan authorities are skeptical at the effectiveness of the military, with Defense Minister Anatolie Nosatii saying in 2022 that 90 percent of the nation’s military equipment is outdated.49 Secretary of State for Defense Policy and National Army Reform Valeriu Mija stated that the military would require up to $275 million to modernize the Moldovan military.50 The Moldovan government is trying to resolve these issues with increased spending, conjunctive training efforts with Western militaries, and receiving newer Western military donations.51

However, this is not taking into account the air-defense systems and physical ground defenses the Ukrainian military has emplaced in oblasts surrounding Moldova, most significantly in Odesa, where the country’s most critical seaport is.52 Even more so, Moldova’s southern and western borders, as well as its access to the Black Sea via the Danube River, are shared with Romania, a full-fledged NATO and EU member state. This would assuredly be an effective deterrent of Russian missiles entering Moldovan air space through Romanian air space, albeit with limited effect given its border with Ukraine. This is not a hypothetical defense either. The Ukrainian government has recently stated its solidarity with Moldova and pledged its assistance to its neighbor, if needed.53

Moldova would also be able to capitalize on the financial aid packages provided by the United States, United Kingdom, and European Union being coupled in with Ukraine. For example, the United States has now pledged to donate $300 million to Moldova to assist in weaning the post-Soviet state completely off of Russian energy dependence including “$80 million in budget support to offset high electricity prices, $135 million for electric power generation projects and $85 million to improve its ability to obtain energy supplies from alternative sources.”54 This is part of the massive $45 billion aid package for Ukraine to help defend itself from Russian aggression.55 Due to the intensive coordinative efforts between the Ukrainian and Moldovan governments, lobbying to be attached to further funding (specifically defense funding) in the name of casting out Russian influence in Europe would likely be attractive for Western countries. This is especially likely considering that the United States has signaled numerous times that it would support Moldova’s democracy, if needed.56

Moldova would proportionally benefit the most from regaining control of Transnistria. As stated, it would allow for the government to stamp out major criminal activities and Russian interference. Giving the Moldovan central government full de facto sovereignty over its territory would consequentially propel the country into esteemed international organizations, increasing stability and development. Organizations like the European Union and NATO (arguably the two most paramount for Moldova) require candidate states to either be a stable democracy or have total control over their territory to proceed further in accession processes.57 For Moldova, joining NATO would be a very important step in assuring its survival as an independent state. This alliance security would not only prevent Moldova from being invaded by an aggressor state, but it would also allow for more resources in defending against hybrid aggression from Russia or pro-Russian actors. And indeed, this is what Moldovan leaders are striving for. Prime Minister Dorin Recean stated after being sworn into office that “we must not confuse defence with neutrality. Neutrality does not insure us in case of aggression.”58 To gain this security, both militarily and economically, it is maintained that Moldovan lawmakers must take the necessary steps to achieve the goal of full territorial integrity.

Potential Negative Consequences for Moldova

Western Support

It is asserted that a significant negative consequence, primarily for both Moldova and Ukraine, would be the reduction in Western nations’ popular support. The unsavory idea of a preemptive (debatably) invasion would certainly be seen to some as nonpeacekeeping. This point, however, will be argued against under the lens of defensive realism later. This would be especially contingent if there was a large resistance movement by insurgents in Transnistria. Yet, the narrative is important to control against Russia. Russia has already made attempts to negatively spin the narrative of a possible offensive into Transnistria by stating Ukrainian forces would conduct a false flag operation.59 Indeed, it is claimed an underhanded operation like this, such as the one the Russians had used in Crimea, would bring negative connotations to Ukraine and Moldova and, therefore, a reduction in support. Forthright public responsibility and transparency of both governments during the seizure would be key for more positive imaging.

Casualties

As previously stated, the consequences for Moldova would most likely be much simpler, but far deadlier. Russian responses to Moldova would be extremely limited militarily, except for long-range missile strikes. Most likely the whole country would be targeted, but particularly vulnerable would be critical areas like heavily populated areas, energy infrastructure, hospitals, and government buildings, as in Ukraine now.

Energy and Economic Crisis

Another major and expected retaliation of the Russians could be shutting off energy completely to Moldova. In the event of an invasion, Transnistrians would likely not discontinue energy production at the Cuciurgan power station to Moldova because that would mean their own people would also be left without energy. But, given Moldova’s sheer vulnerability in energy and Russia’s history of energy blackmail along with the destruction of infrastructure, Russian officials would most likely have no qualms in exposing both anti- and pro-Russian actors within Moldova to a complete embargo of natural gas.

This consequence is likely the most inevitable to destabilize the country that would already have a destabilized region from a military operation. If Moldova was to take the step to jointly take over Transnistria with Ukraine, then the Sandu government would need to overhaul its energy infrastructure by allocating donated Western aid money from “capacity building” to restructuring of the Moldovan energy market.60 Though accomplishing much progress in the area already, Moldova will need to accelerate the modification of Soviet-era laws or business practices to EU standards to attract more foreign direct investments.61 An example of this would be hastened unbundling of the dominant gas company MoldovaGaz into three separate companies to respectively purchase, transmit, and distribute natural gas.62 This would be done in conjunction with the fair promotion of alternative private energy companies to stake a claim in Moldova, which would provide more options in the energy sector.

Occupation, Repatriation, and Possible Insurgency

Politically, Moldova would face a major dilemma in occupying Transnistria. The region has genuine support for Russia, and many identify themselves as Russian nationals. It is a very similar situation to other illegitimate substates within the Russian sphere of influence.63 Though the population and area are not particularly large, approximately 465,000 people and 4,163 square kilometers, it is a fervently pro-Russian population.64 Reintegration into the Moldovan state would likely be difficult and costly for the poorer nation. In all probability, this would require a military occupation for an uncertain amount of time.

With that said, Moldova has already created somewhat of a road map for this issue with the Turkish-speaking regions of Gagauzia. This region, ethnically and linguistically distinct from the rest of Moldova, initially wanted to separate from the former Soviet state.65 In contrast to Transnistria though, the Moldovan government brokered a deal to fuse powers with Gagauzian figures and granted regional autonomy.66 However, again, attempts by Russian and pro-Russian actors to influence the region have led to an increase in opposition voices against the pro-Western government there.67 Indeed, even Shor party leaders in the region have called for actions that were planned in the aforementioned Kremlin document from March 2023, such as the opening of an envoy or consulate within Gagauzia.68

An armed insurgency could also be possible given the political ardor of the Transnistrian population. It would be a realistic threat facing both Moldovan government forces and Ukrainian border troops. However, if there was an insurrection consisting of guerrilla-type warfare, Transnistria, or the whole of Moldova, would not be areas that would be fruitful for this type of operation. First, the main resources of arms trading would be either neutralized or utilized by a policing military. With reduced access to resources and trade networks, now under the control of Moldovan and Ukrainian officials, there would likely be far less materials to wage an irregular conflict against authorities.

Second, though Transnistrians are currently heavily politically opposed to both Moldovan and Ukrainian sentiments (i.e., against Russian interests), all regions have similar or mixed elements of linguistic, religious, and cultural backgrounds. While this would not stop an insurgency, studies have indicated that it would likely reduce the amount and duration of participation, in contrast to countercultural insurgencies conducted by the United States in Iraq or Afghanistan or by Russia in Siberia.69

Finally, a strong facet indicating a failure for a post-intervention Transnistrian resistance would be the geographical limitations for the insurgents. Geography has been repeatedly named as a key factor in how successful an insurgency can be. If the terrain is rugged, mountainous, swampy, or in deep jungle, it becomes far more difficult to locate and eliminate insurgents waging a guerrilla war. This could also be witnessed in anti-insurgency operations in Vietnam, Afghanistan, or Liberia, among others.70 Neither Transnistria nor Moldova have these types of terrain in even a moderate amount. Residing on the western edge of the Eurasian Steppe, the country has vast expanses of pasture and farmland with comparatively very little forest cover or rough terrain. Additionally, if an insurgency were to take place just within Transnistria, the area of operations to quell this by Moldovan and/or Ukrainian officials would be a small and very narrow area. Rebels would essentially have much less areas to run or hide.

This begs the question, “What would be next in Moldova?” This is not an easy question to answer. If Moldovan officials intended to conduct this coordinated offensive, their economy would be on the verge of collapse, if not collapsed, given the amount of industry within the Transnistrian jurisdiction. Depending on the effects of the occupation and repatriation of Transnistrians, they could face anywhere from a smooth transition of authority to a fully armed insurrection. Most likely, Western officials would have to determine if Moldova would be worth supporting temporarily, which would be costly to say the least. Again, with security interests, it may just be required, though.

Why Now for Ukraine?

While Moldova’s reasoning to participate in an offensive into Transnistria would serve to benefit more in the long term rather than short term, it is asserted that the Ukrainian justifications and motivations are more urgent. Specifically, the benefits that would apply for Ukraine would primarily serve at the strategic level in the war against Russia. That being said, there are still long-term benefits in committing to an operation like this in their backyard.

Weak for Russia Now, Strong for Russia Later

First and foremost, the apprehension of Transnistria by the armed forces of Ukraine, undoubtedly the most qualified entity to do so at the moment, would neutralize a national security threat on the western border of the nation while it is weak. With a presence of approximately 1,500–2,000 Russian troops (with only 50–100 of these actually being native Russians and the rest being Transnistrians with Russian passports), Transnistria represents an unacceptable threat to Ukraine, especially with the highly critical seaport of Odesa being so close.71 However, it would be ignorant to just look at a shallow number of Russian soldiers and state that as the correct strength. To start, these troops are not entirely comprised of purely combat forces. They are divided between a smaller group of peacekeeping forces (officially no larger than 450 troops) and the larger Operational Group of Russian Forces, the latter being primarily charged to guard the Colbasna ammunition depot.72

This peacekeeping force has committed numerous aggressive actions against journalists and civilians, resulting in lethal situations.73 Both of these troop contingents must wait an extensive time to rotate from these posts, as Moldova and Ukraine have effectively banned official Russian military access since 2015.74 This lack of access has most likely led to a certain amount of corrosion within military resources and/or training. Also, one must take into the consideration that, before the full-scale invasion of Ukraine, Russian forces were highly esteemed and thought to be thoroughly trained until numerous, consistent failures revealed otherwise.

The armed forces of Transnistria, with approximately 4,000–7,500 active and 15,000 reserve personnel, are an additional factor.75 While the quality of this military force is questionable, one scholar assessed that the Transnistrian military consisted of “four motorized rifle brigades, a tank battalion, an artillery regiment, and an anti-aircraft artillery regiment,” including 18 tanks as of 2009, donated during the 1992 war.76 The assumption here is that the military equipment in Transnistria derives from pre-1992 Soviet stockpiles, significantly older than much of what is being used in the Ukrainian military now. To sum up, the Critical Threats Project described the situation by stating, “These troops engage in regular military exercises, but they are very poorly equipped. The poor performance level of Russian troops fighting in Ukraine suggests that the troops in Transnistria would perform poorly in combat.”77

With its eight years of NATO-grade coordinated training, current experience in combat against Russian forces, and its continuous massive donations of Western military equipment, the Ukrainian military would likely be able to conduct advanced maneuver warfare with efficacy in this narrow region, especially in coordination with Moldova. Donated tanks, armored fighting vehicles, and aircraft would most likely serve effectively when considering logistical supplies would be virtually on-site. While Moldova also suffers from a lack of modern equipment within its armed forces, a coordinated invasion from both borders of Transnistria would likely at least match or slightly overwhelm the limited force in Transnistria.78 However, Moldova’s intermediate level of recurring conjunctive training efforts with American and other Western militaries may allow for slightly more effective combat capabilities than expected.79

Considering Ukraine’s potential to overpower the much weaker PMR forces, it may be logical to leave these forces alone. However, a joint offensive now would be prudent as an investment move, rather than an immediate battlefield tactical move. Although Transnistrian and Russian forces in the PMR are currently unlikely to launch a military operation into Moldova or Ukraine, there is still significant potential for these forces to invade later with greater strength.

Whether or not Putin succeeds in his war in Ukraine, given a retention in power, Putin will still continue to employ interfering assets throughout Eurasia. Long after Western support and media coverage about Russian aggression has waned, Putin and his successors will use stealthy, underhanded tactics to cripple Russia’s neighbors’ development. This complacency is where Russia will thrive in rebuilding its assets in Transnistria. Though impossible now with border closures, the PMR could later be bolstered with regular Russian troops once these border policies are relaxed. Furthermore, these troops could funnel resources to and train PMR forces to legitimize a real security threat in Moldova on the border of Ukraine.

Given the pattern of the Russian Federation reinvading after an initial failure or mere minor victory (Crimea, Chechnya, and Donbas), it is realistic for Russian officials to do the same for Ukraine, once again. While it would take time to rebuild the Russian military, it could be done within a reasonable time frame. There would be a possibility of reinvasion in an attempt to finish the job, especially if in a frozen conflict. This is when the utilization of Transnistria as a disembarkation point would be highly likely to execute this task. With the unstable nature of Moldova’s political attitude toward Russia, just as there could be a pro-EU government that bans Russian soldiers from entering the country, there could also be a pro-Russian one that has a more lax view or neutral view of military forces flying to Chişinău, then traveling to Tiraspol. The long-term security of Ukraine would be further assured with a joint invasion into a hostile but still developing region that lines its western flank.

Resources

Another potential motivation to invade Transnistria would be for the aforementioned Colbasna ammunition depot. This infamous stockpile of Soviet-era ammunition is a prime target for Ukraine. Lying approximately 1.6 kilometers away from the Ukrainian border, this depot is the beating heart of the ammunition supply for the PMR. As of 2009, Russian data indicated that the depot consisted of “21,000 tons of equipment; about half of the 42,000 tons that existed in 1994,” which was donated by the Russian 14th Army during the war.80

However, Colbasna has been implicated as the primary source of illegal arms exportation from Transnistria, so this quantity has likely been reduced even further.81 While this ammunition could be seen as potential war booty to use against the Russian military in the eastern front, it is argued that such munitions would most likely be too unreliable for active military usage when considering age, known Russian storage mistakes, and Soviet ammunition quality, as has been evidenced in the current war.82 It may be more prudent to safely destroy the arms and ammunition within. However, utilized or not, the acquisition of arguably the largest ammunition stockpile in Southeast Europe would neutralize the tools for a major security threat.83

Organized Crime

As mentioned, crime groups consistently have exploited Ukrainian territories, citizens, and official channels to conduct illicit operations from Transnistria. Since the full-scale invasion by Russia in February 2022, Ukraine has severely limited border traffic and monitored the border with Transnistria.84 While this has temporarily cut down on illicit trade traffic going into Ukraine, it is very likely that without intervention from Ukraine in the PMR, this trafficking will resume to full levels once the war is over and the Ukrainian military eventually demobilizes.85 Essentially, these problems will remain a major thorn in the side of Ukrainian authorities unless preventative actions are taken. Additionally, by capturing the Colbasna ammunition depot, they would also halt a source of arms smuggling operations affecting Ukraine and Moldova.

Ukraine has almost as much to benefit from the neutralization of organized criminal activities in Transnistria as Moldova. Aiding the Moldovan government here with military assistance would neutralize an international problem and heavily assist in stifling blatant organized crime throughout Eastern Europe.

Nonrecognition

Transnistria’s peculiar status of recognition also allows Ukraine justification for an offensive with Moldova. As stated, the Ukrainian and Moldovan governments have vowed to work together to strengthen Moldova’s sovereignty and democracy. Ukraine, obviously, does not recognize Transnistria, and neither does the Russian Federation. In fact, all countries in the United Nations deem Transnistria as a part of Moldova’s sovereign territory and do not recognize it as a nation. While the Russian Ministry of Defence has recently announced that an attack on Transnistria would be treated as “an attack on the Russian Federation” and that Putin would no longer explicitly recognize Moldova as fully sovereign, this still opposes a whole 30 years of Russian foreign policy, including in Putin’s era.86 Legally, the Russian Federation still does not officially recognize, as of today, Transnistria as legitimate. This framing allows Ukraine to strike at a time when Russia’s diplomatic claim to retaliate in any sense, most notably nuclear, is limited. But none of this excludes a possibility where Putin sees the threat of existence to Transnistria as too large and annexes the territory as a piece of the Russian Federation. Overall, the suggestion for Ukraine comes down to one colloquial saying: strike while the iron is hot, and hot it is now.

Potential Negative Consequences for Ukraine

Tangible negative consequences for Ukraine to invade Transnistria during the war, either in coordination or by the explicit approval of the Moldovan government, are also limited. The reprisal by Russian forces would virtually be unseen in light of the total war being engaged entirely within Ukrainian territory. However, there are consequences that can applied to Ukraine’s military and overall funding with the war effort.

Casualties and Resources

The most direct consequences for Ukraine would be immediately on the battlefield. This consists of military casualties and a diversion of resources from other critical areas of the Ukrainian front lines. However, Russia simply does not have the military manpower or resources to respond to such a threat in the western sphere of Transnistria. Essentially, the response would be a similar level of civilian bombings (if not less with responding missile strikes in Moldova) and combat intensity as before.

Depending on the effectiveness and duration of other counteroffensive operations, military forces and equipment already may not so easily be spared for an operation that is more beneficial in the long run rather than in the short term. If an offensive into Transnistria were to take longer than expected, then these resources would be even further diverted and strained for longer than would be expected. Even more so, Ukrainian forces would likely have to serve as additional occupational troops if there was an extended armed insurgency.

In addition, if counteroffensive operations by Ukrainian forces entirely falter in Ukraine against Russia, then there are far larger issues to divert resources and manpower to. But the long-term benefits of greater security for both countries in conjunction with the opportune timing brought on by Russia’s preoccupation in Ukraine still outweigh the immediate physical negative consequences.

Occupational Hazards

As previously mentioned, Ukraine would likely be faced with a similar issue as Moldova in maintaining peace in Transnistria. Spillover of pro-Russian insurgents may occur at Ukrainian borders with irregular attacks. This would require a diversion of military resources that would last even longer. However, with the reasons given in the Moldovan section, discussing this insurgency would likely not be expansive or long-term in nature without institutional support from a pseudo-government type like Tiraspol now.

Western Support

Another risk shared by Ukraine with Moldova is, of course, the reduction in Western aid and support. If Western officials shied away from supporting Ukraine either in military aid or purely financial aid, it would be a devastating blow to the war effort. To reassert, it would be crucial to control the narrative and convey that this operation would be necessary in the fight against Russian aggression and expansionism on other sovereign states’ territories. Finally, this is not a guaranteed product of a joint invasion into Transnistria. It is possible that, given Western allies’ security interests in Eastern Europe and the Black Sea region, that Western military support could continue without skipping a beat.

Table 1. Consequences and benefits for Moldova and Ukraine

|

|

Potential consequences

|

Potential benefits

|

|

Moldova

|

• Energy/economic crisis

• Integration (lack thereof) of pro-Russian population

• Casualties

• Air-based Russian retaliation

• Decrease of Western support

|

• Long-term control of energy security

• Full sovereign control of territory

• Future Russian military intervention neutralized

• Severely reduced institutional Russian interference

• International organizational appeal

• Full prosecutorial control of crime/corruption

• Colbasna depot utilized and/or neutralized

|

|

Ukraine

|

• Diversion of resources

• Casualties

• Decrease of Western support

|

• Future Russian military intervention neutralized

• Colbasna depot utilized and/or neutralized

• International organizational appeal

• Crime/corruption source on border under government control

|

Source: compiled by the author.

The Defensive and Offensive Thoughts

For both Moldova and Ukraine, the aforementioned reasons in support of an invasion are entirely justified under a defensive realist lens in response to Vladimir Putin’s pattern of aggressive expansionist actions. Putin’s foreign policy has been centered around the maximization of power and maintaining hegemonic stature in Eurasia, specifically regarding former Soviet states. Moldova and Ukraine are both typical former Soviet states that Putin’s Russia has destabilized. Wielding power in the form of intimidation, nuclear arms, oil and natural gas blackmailing, and underhanded influence, post-2000 Russia has devoted its foreign policy to the undermining of delicate post-Soviet states to maintain power. In conjunction with these actions, Russia could support unrecognized breakaway regions that Russia claims to be legitimate in one way or another. These policies and actions undertaken by Putin suggest that he subscribes to geopolitical strategies consistent with aggressive offensive realism.

Putin’s Offensive Aggressive Pattern

Steven Lobell outlines that “for offensive realists, expansion entails aggressive foreign economic, political, and military policies to alter the balance of power; to take advantage of opportunities to gain more power; to gain power at the expense of other states; and to weaken potential challengers through preventive wars or ‘delaying tactics’ to slow their ascent.”87 This is the quintessential form of foreign policy wielded by Putin. However, one could argue that this view of Putin’s strategic philosophy could classify as classical realism: where leaders’ personal lust drives the state for more power and that weaker actors must endure.88 In contrast, offensive realism states that the anarchic international system and fear drives states to maximize power to increase the odds of survival.89 It is asserted that Russia’s twenty-first century invasions under Putin have a mixed characterization of both classical realism and offensive realism strategies, producing a unique strategy of “aggressive offensive realism.” It should be noted that this claim is not to convey an example of how the geopolitical system operates, but how Putin may see it himself and base his actions off of.

Following the dissolution of the Soviet Union, Russian figures found themselves in a desperate situation to maintain international power. In brutal fashion, they went on the offensive and supported separatist movements in Moldova and Georgia, while attempting to quell separatist movements within their own borders in Chechnya. However, these conflicts highlighted the weaknesses and insecurities within the new Russian Federation. The First Chechen War (1994–96) proved a humiliating disaster for the Russian Army. Even in their more successful endeavors, the military forces of the newly created countries of Moldova and Georgia were very weak and poorly trained. While Russia’s military was weak in the 1990s, they were simply not as weak as these smaller, fledgling independent nations attempting to organize stability.90 This is the argument of Russia’s offensive realism in maintaining power and stifling any challenges in their previous sphere of power.

However, once Vladimir Putin was elected as president, he capitalized on the damaged nationalism of the Russian people after the fall of the Soviet Union and increased the frequency and intensity of both military interventions and subversive influence. Similarities can be found between these actions taken against the regions of South Ossetia, Abkhazia, Crimea, and Donbas with Moldova, which highlight’s Putin’s aggressive offensive realist strategies.

Following his rise to power, Chechnya suffered and lost in a brutal war against Putin’s new regime. For Georgia, 2008 would bring a more substantial Russian invasion and occupation in their internationally recognized territory. Of course, after its public rejection of Russian influence with the Euromaidan Revolution, Ukraine would see the beginning of their war against Russia in 2014 with the invasions of Crimea and Donbas. In Moldova, there was a significant shift in policy when President Putin was initially elected. At the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE)-coordinated 1999 Istanbul Summit, the Russian government promised to withdraw all military presence from Moldova by the end of 2002.91 However, this agreement was clearly reneged on with Russian troops still residing in Transnistria. So, this could be the argument for a classical realist that Putin’s lust for power has caused this expansionism. However, the historical track record supports evidence for both: an absolute established pattern of aggression, expansion, and interference that has only increased under Putin.

Furthermore, as with Ukraine and Moldova, Vladimir Putin has primarily targeted areas with an underlying conflict that are weakened because of this. In a way, these tensions, consisting of ethnic, religious, linguistic, and/or political reasons, can be accelerated by Russian influence to maximize their power over the region. Additionally, influence can be far more than just economic or passively political. Prior to the 2022 war, Georgia, Ukraine, and Moldova had remarkable similarities in threats faced from Russia. Each had Russian troops within their borders that were residual from previous invasions. Even more, the Russian government had supplied and supported separatist groups in each region. This provided a security base for Russian or pro-Russian actors. Each country faced a set of economic challenges where their respective breakaway or invaded regions were either tied with Russian interests or entirely separated, losing valuable resources and capital.

A study on breakaway states found in a comparison to the situations in Donbas and Crimea that “Russian influence and intervention, as well as the relations between Russia and the West, certainly conditioned the outcome of the two Georgian secessionist conflicts [South Ossetia and Abkhazia] as well as the one in Moldova. Russian troops are on the ground in all three of these regions today . . . Russian financial support is vital to their survival.”92 Russia is fueling the same exact tensions with Moldova as it did in Georgia and Ukraine. The conclusions to those, albeit not finished, have proven a Russian invasion follows consistently with Georgia in 2008 and Ukraine in 2014 and 2022.

Required Defensive Realist Strategies from Moldova and Ukraine

Though defensive realism originated as an amalgamation of ideas from numerous authors, the theory can be traced to arguments from Kenneth Waltz’s Theory of International Politics from 1979. Waltz argues that states seek to balance power in the world by coalescing with other weaker states in order to survive and do not maximize power, as the larger hegemonic states they ally against are usually the actual threats to their survival.93 Waltz writes, “The first concern of states is not to maximize power but maintain their positions in the system.”94 This is the crucial motivation of states that practice defensive realism.

Lobell added that “defensive realists maintain that the international system encourages states to pursue moderate and restrained behavior to ensure their survival and safety, and provides incentives for expansion in only a few select instances.”95 In essence, defensive realism conveys that states should not seek to maximize power but maximize security on their scale. It also finds that conflict is sometime necessary in the face of a true security dilemma or aggressor state.96 Defensive realism also argues that there are indeed certain occasional incentives for states to expand their power, but that these upset the international system and balance of power.97 Essentially, defensive realism contends that while some states use anarchy to bolster their power to secure themselves, all other states will utilize the international system to secure themselves against these aggressive hegemons.98

It is argued that the absolute optimal way to counter this particular aggression, while the opportunity is present, is to treat this parallel threat in Transnistria and Russia in a defensive realist strategy. Defensive realist strategies would allow smaller states such as Moldova to maintain security in the chaotic environment produced by Russian aggression. An offensive into Transnistria could not be seen as a gratuitous move by either Ukraine or Moldova as neither has previously displayed overly aggressive behavior in the international system. While Moldova conducted offensives during the Transnistrian War, it was still in response to violation of territorial precedence during its time as a Soviet republic and clearly limited in number.99

To supplement, this does require a brief comparison to claims that Putin has acted as a defensive realist. Claims such as these usually outline the generality that Putin’s invasions are in response to an eastward encroachment by NATO. Additionally, Georgia, Ukraine, and Moldova are simply too close for comfort to be a part of this organization and that it is within Russia’s sphere of influence. However, the fact remains that defensive realism requires restrained or limited actions. In contrast, it usually punishes those who seek expansionism. While Moldova, Ukraine, and Georgia have all seen either invasions or occupations by hostile troops among numerous other hybrid threats, Putin’s Russia has portrayed itself as constantly being threatened by these smaller, far weaker countries. In actuality, it is a massive state with nuclear weapons domineering as a regional hegemon (at least for now) that simply bullies smaller countries. This is not consistent with defensive claims.

Balancing against these aggressive attempts at hegemonic power grabbing by Putin’s Russia is necessary for survival in both Moldova and Ukraine. This cooperation recently set goals for international organizations, and commitment to internal security highlights the mechanisms within the defensive realist theory. While conducting an offensive into Transnistria can be seen as provocative, it must also be asked: What is there to provoke? As stated, Putin recently signaled that Russia no longer respects the full sovereignty of Moldova. He even rescinded a decree confirming their sovereignty, clearly a threat to national security for Moldova.100 Ukraine is already in the middle of a war against Russia within its own territory. The illegal breakaway state of Transnistria is certainly a security threat considering that approximately 1,500–2,000 Russian soldiers are based there, which has been a violation of international law since 2002.101 Even more so, the very existence of the Russian-aligned Transnistrian armed forces, consisting of approximately 4,000–7,500 active personnel, is a threat to national security for Moldova.102 Additionally, Transnistrian authorities have made requests to Moscow for an increased number of Russian peacekeepers.103 For Ukraine, if Moldova were to completely fall under the influence of Russian will, which has been rumored multiple times, it would allow a base of operation for the Russian military in the western part of the country.104 Under defensive realism, neutralizing a security threat like Transnistria would bring stability to the region and support each nation’s national security interests.

While the call for an offensive by Moldova and Ukraine into Transnistria could be called preemptive, the reality of the situation is that Moldova would not be invading another recognized, sovereign country; they would be resolving a long-term security issue constrained to their own borders. Even with the invitation and bilateral cooperation of Ukraine (act of balancing), it would still be a reasonable and singular incident in an attempt to restore national security to internationally recognized officials for Moldova. This is consistent with defensive realist strategies.

The reader is reminded that the ultimate end goal of Moldova and Ukraine would be the accessions into a defensive alliance, NATO, that was originally designed to balance against the USSR and has again found itself doing the same against its successor state. Additionally, both countries aim to join the European Union, which is also designed to enhance the security of smaller states. It can be concluded that the appropriate reaction from Moldova and Ukraine regarding Russian aggression are these goals in order to tip the balance of power in favor of survival. Defensive realism dictates this is the appropriate method of dealing with this larger and mutual threat.105

When to Seize the Day?

The ideal timing for a proposed operation into Transnistria would have to fit a window suitable for both Ukraine and Moldova. The overall requirement would have to be during the current war against Russia. Mobilization of the Ukrainian military along with funding and aid from Western support will likely be never higher than now. As previously mentioned, it can also serve as an extension of offensive operations for Ukraine. However, the time to invade would also have to be sustainable for the whole frontline operations. This would likely be after primary counteroffensive operations, but, of course, it would be contingent on the successes of those.

For Moldova, there would need to be time to rapidly prepare for restructuring their gas and energy systems, which is not an easy thing to do. Similarly, the Moldovan military would need time to prepare and standardize their forces for relevant operations. The ideal window of opportunity would still be during the war against Russia by Ukraine. With the current nonrecognition status of the PMR, diversion of Russian equipment in Ukraine, and the assistance pledged by Ukraine, it would be likely this type of opportunity will not arise again once peace is made. It is wise to make the short-term sacrifice now, rather than the long-term sacrifice later.

Figure 1. Typical example of the geography of the Dniester River near Popencu, Moldova

Source: Alexey Averiyanov, Encyclopeadia Britannica, adapted by MCUP.

How to Seize the Day

Though the breakaway state is approximately 209 kilometers long, Transnistria has its greatest width at approximately 24 kilometers. Geographically, it is extremely vulnerable to a two-front offensive from Moldovan and Ukrainian directions and can be easily divided. However, it would be considerably more difficult for Moldovan forces to advance from the west as Transnistria’s western border largely consists of the Dniester River. There are seven river crossing structures over the Dniester consisting of road bridges, railroad bridges, and reservoir dams. These do not include roads leading into Tiraspol, crossings already under de facto Moldovan control, or river ferries. Indeed, the Moldovan armed forces do possess numerous types of amphibious armored vehicles (most of them being Soviet made), though the actual number of these are unclear and suitable landing zones for them would be limited with numerous marshes and large, sloping bluffs lining the river.106

Moreover, it should be noted that neither Moldova nor Ukraine could conduct this offensive unilaterally. If Moldova intended to conduct this type of operation on their own, this would be highly unlikely to succeed given the country’s shortcomings within their military. Not only would it fail, but it would also destabilize the country further and possibly give PMR forces reason to conduct a counteroffensive onto Chişinău. For Ukraine, while they would be the muscle of the operation, and would likely succeed, it would be a major violation of territorial integrity if they decided to invade without bilateral consent from Moldovan officials. The international consequences of this for Ukraine, which relies on Western aid, would be devastating.

Map 2. Possible areas for Moldovan and Ukrainian forces to advance within the Dubăsari District

Source: Roney, “Transnistrian Tactical Map,” Google Maps, adapted by MCUP.

But, as mentioned, the state of the Moldovan military could be described as developing, so an optimal role here would be to act more statically and divert Transnistrian and Russian firepower as near to the western border areas as possible, so Ukrainian forces can more easily move in from the east. The most fitting role for Moldovan forces would be to secure and blockade portions of the Moldovan M4 highway. Possibly the most ideal places to do this would be the two east-west land corridors of the Dubăsari District they partly control through Transnistria near Doroțcaia and Roghi. These proposed areas are optimal to advance on because Moldovan forces have control of villages on the east side of the river. Already there are effective bridgeheads (especially for the southern Doroțcaia area where control is much more substantial and there is an actual highway bridge crossing) that would allow for additional forces to cross the river.

The M4 highway passes through these land corridors (effectively serving as the de facto border of control in these areas) and virtually the entire length of Transnistria (see maps 1 and 2). Cutting off this route would divide and isolate Transnistrian forces into numerous areas, as well as secure control over the entire land corridors. Supplementation from the Ukrainian Army would be relatively unchallenging given that these land corridors almost touch the Ukrainian border within a mile and one runs parallel with the M21 highway. From these Moldovan-held corridors, Ukrainian forces would be able to attack PMR forces both from their eastern border, as well as within Transnistria, effectively defeating in detail these forces by dividing them. However, given the numerous potential objectives within the shallow depth of territory of Transnistria, any conquered area could also be utilized as an isthmus to attack from. Ukrainian forces themselves could also bisect thinner, vulnerable areas of Transnistria, and, by default, the M4 highway. A prime example would be cutting off the highway near Mihailovca where it is as little as 2.4 kilometers from the Ukrainian border to the western river border.

Map 3. Land isthmuses and vital areas attractive for initial advances in Transnistria

Source: Roney, “Transnistrian Strategic Map,” Mapcreator, adapted by MCUP.

The Ukrainian role in an offensive would be dynamic and paramount with its extensive and increasing access to Western equipment, vast armored resources, and overall tested quality. These capabilities would allow for Ukrainian forces to advance rapidly into an extremely thin enemy territory. A blitzing advance would be imperative to overwhelming a very possibly complacent, inexperienced, and resource limited Transnistrian and Russian security force excluding near the Colbasna ammunition depot.107 This brings the author to the two basic objectives to neutralizing Transnistria: Colbasna and Tiraspol. The reasons regarding Colbasna have already been stated. The depot, 1.6 kilometers away from Ukrainian territory, would be the top priority to severely limit any resupply to other troop concentrations in the region. However, given the high value of Colbasna, it would serve in the interests of a Ukrainian offensive to avoid where this strength is and attack where weaknesses or less effective troops are.

Tiraspol, being the capitol and largest city of Transnistria, would be absolutely essential in dismantling the region. Capturing the city would not only cut the breakaway state in two, but it would most likely lead to the capturing of prominent political figures within the Transnistrian government, pacifying the political stature within the breakaway state.

Finally, there are two important factors that must be heavily utilized during this offensive. First, controlling the narrative and reminding domestic and international audiences the threats to national security will be required to maintain popularity. The idea that this threat of thousands of enemy soldiers is either, for Moldova, in their sovereign territory, or for Ukraine, in their backyard at the border, is a frightening thought for populations that can maintain popular support. Allies like the United States or United Kingdom would provide crucial voices in maintaining international support, so their cooperation would be needed. Second, absolute communication and coordination between the Ukrainian and Moldovan militaries and governments will be imperative to effectively execute conjunctive operations and further strengthen diplomatic ties in a time of crisis. With the capturing of these essential objectives, it is asserted that the Moldovan government with the assistance of the Ukrainian military would obtain its full de facto sovereignty over its entire territory.

Conclusion

Ukraine opens a new front to the war; Moldova regains control over its territory; and Putin’s Russia falters in its offensive realist strategy to undermine its former allies and keep control. It is easy to see what positive outcomes may come out of an invasion of Transnistria. The target is vulnerable. However, it is also easy to forget that with these policy suggestions, consequences would be imminent. In a sense, though, Moldova is stuck between a rock and a hard place in their decision here. If a decision is taken to regain legitimate authority over Transnistria, Moldova will be faced with a national crisis of losing energy security and maintaining peace in a temporarily highly destabilized post-conflict state, however brief it is. However, both Moldova and Ukraine would find that the long-term security and stability benefits would outweigh the alternative of allowing the status quo of the gray zone of Transnistria to continue onward and regain the capacity of full interference in the region, whether it be in 10, 20, or more years. In the context of defensive realism, it becomes abundantly clear that for Moldova and Ukraine to survive and counter Vladimir Putin’s aggressive offensive expansionism, they must cooperate in dealing with this creeping, yet crucial threat. In this case, the seizure of Transnistria must take place in the right time to maintain stability in the long term. If left alone, not only will Ukraine and Moldova be at risk of future increased destabilization and corrosion but so will all of Eastern Europe.

Endnotes

- Natalia Cojocaru, “Nationalism and Identity in Transnistria,” Innovation: The European Journal of Social Science Research 19, nos. 3–4 (2006): 20, https://doi.org/10.1080/13511610601029813; and Stefan Ciobanu, Cultura românească în Basarabia sub stăpânirea rusă (Chișinău, Moldova: Associației uniunea culturală bisericească din Chișinău, 1923).

- Bruno Coppieters, “Moldova and the Transnistrian Conflict,” in Europeanization and Conflict Resolution: Case Studies from the European Periphery (Ghent, Belgium: Academia Press, 2004).

- Coppieters, “Moldova and the Transnistrian Conflict.”

- Coppieters, “Moldova and the Transnistrian Conflict.”

- Coppieters, “Moldova and the Transnistrian Conflict.”

- “Secret Additional Protocol,” Avalon Project, 23 August 1939.

- “Secret Additional Protocol.”

- Coppieters, “Moldova and the Transnistrian Conflict.”

- Diana Dumitru, The State, Antisemitism, and Collaboration in the Holocaust: The Borderlands of Romania and the Soviet Union (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2018), https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781316443699; Cașu Igor, “State Terror in Soviet Moldavia, 1940–1989: Categories of Victims, Repressive Methods and Punitive Institutions,” in New Perspectives in Transnational History of Communism in East Central Europe, ed. Krzysztof Brzechczyn (Berlin: Peter Lang GmbH. Lambroza, 2019); and Shlomo Lambroza, “The Tsarist Government and the Pogroms of 1903–06,” Modern Judaism 7, no. 3 (October 1987).

- Coppieters, “Moldova and the Transnistrian Conflict.”

- Coppieters, “Moldova and the Transnistrian Conflict.”

- Steven D. Roper, “Regionalism in Moldova: The Case of Transnistria and Gagauzia,” Regional & Federal Studies 11, no. 3 (2001): https://doi.org/10.1080/714004699.

- Roper, “Regionalism in Moldova.”

- Coppieters, “Moldova and the Transnistrian Conflict.”

- Coppieters, “Moldova and the Transnistrian Conflict.”

- “Статистика о Внешней Торговле ПМР,” Министерство экономического развития; “Transnistria’s Debt for Russian Gas Approaching $10 Billion,” Infotag, 14 June 2023; and Isabeau van Halm, “Moldova Faces Winter Darkness as Russia Weaponises Energy,” Power Technology, 17 November 2022.

- Madalin Necsutu, “Moldova to Investigate Russian Influence on Domestic Politics,” BalkanInsight, 1 November 2022.

- Galiya Ibragimova, “How Russia Torpedoed Its Own Influence in Moldova,” Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, 11 May 2023.

- Kamil Całus, “Moldova: Diversifying Supplies and Curbing Gazprom’s Influence,” Centre for Eastern Studies (OSW), 15 June 2023.

- Madalin Necsutu, “Moldova Makes Plans to Escape Russian Energy Dependence,” BalkanInsight, 20 April 2022; and Alexander St. Leger, “Russia’s Ukraine Invasion Is Fueling an Energy Crisis in Neighboring Moldova,” Atlantic Council, 5 December 2022.

- Całus, “Moldova.”

- Laman Zeynalova, “Moldova Imports Gas Through IGB, Interested in Further Purchases,” Trend News Agency, 29 June 2023; and Dimitar Bechev, “Sailing Through the Storm: Türkiye’s Black Sea Strategy amidst the Russian-Ukrainian War,” European Union Institute for Security Studies, Brief 1, February 2023.

- “Romania Will Collaborate with the Republic of Moldova to Continue the Implementation of the Projects Necessary to Interconnect the Natural Gas and Electricity Networks,” Ministry of Energy, 17 May 2023.

- Suriya Evans-Pritchard Jayanti, “Moldova Needs an Energy Overhaul,” Atlantic Council, 7 June 2023.

- Moldova Energy Profile (Paris, France: International Energy Agency, 2020).

- “Thousands of Protesters March in Moldova Demanding Help with the Cost of Living Crisis,” Euronews, 20 February 2023.

- “Thousands of Protesters March in Moldova Demanding Help with the Cost of Living Crisis.”

- “Thousands of Protesters March in Moldova Demanding Help with the Cost of Living Crisis.”

- “Oligarch Sentenced for Role in Stealing $1B from Moldovan Banks,” AP News, 14 April 2023.

- “Thousands of Protesters March in Moldova Demanding Help with the Cost of Living Crisis.”

- Holger Roonemaa, Delfi Estonia, and Anna Gielewska, “Secret Kremlin Document: How Russia Plans to Overturn Moldova,” VSquare, 14 March 2023.

- Roonemaa, Estonia, and Gielewska, “Secret Kremlin Document.”

- “Russian Foreign Minister Speaks of Moldova as the ‘Next Ukraine’,” Bne IntelliNews, 3 February 2023.

- “Medvedev: The Republic of Moldova Does Not Exist as a Country, It Was Sold to Romania,” Romania Journal, 23 April 2023.

- Mark Galeotti, “The Transdnistrian [sic] Connection: Big Problems from a Small Pseudo-State,” Global Crime 6, nos. 3–4 (2004): https://doi.org/10.1080/17440570500277359.

- Galeotti, “The Transdnistrian Connection.”

- Galeotti, “The Transdnistrian Connection.”

- Galeotti, “The Transdnistrian Connection”; Eliza Gheorghe, “After Crimea: Disarmament, Frozen Conflicts, and Illicit Trafficking Through Eastern Europe” (occasional paper, Judith Reppy Institute for Peace and Conflict Studies, Cornell University, 2016); and “Nuclear Smuggling Deals ‘Thwarted’ in Moldova,” BBC, October 2015.

- Daniela Peterka-Benton, “Arms Trafficking in Transnistria: A European Security Threat?,” Journal of Applied Security Research 7, no. 1 (2012): https://doi.org/10.1080/19361610.2012.631407.

- Gheorghe, “After Crimea.”

- Gheorghe, “After Crimea.”

- Gheorghe, “After Crimea.”

- Félix Buttin, “A Human Security Perspective on Transnistria: Reassessing the Situation within the ‘Black Hole of Europe’,” Human Security Journal, no. 3 (2007).

- “2022 Trafficking in Persons Report: Moldova,” Office to Monitor and Combat Trafficking in Persons, Department of State, accessed 17 July 2023.

- “2022 Trafficking in Persons Report: Moldova.”

- “2022 Trafficking in Persons Report: Moldova.”