Ben Zweibelson, PhD

https://doi.org/10.21140/mcuj.20231401002

PRINTER FRIENDLY PDF

EPUB

AUDIOBOOK

Abstract: Current human-machine dynamics in security affairs positions the human operator in the loop with artificial intelligence to conduct decisions and actions. As technological advancements in AI cognition, speed, and weapon sophistication increase, human operators are increasingly being shifted to an on the loop where AI takes more responsibility in warfare and defense decisions, whether tactical or even strategic. Human operators are also falling off the loop, trailing enhanced AI systems as the biological and physical limits because humans are not the same for artificial intelligence in narrow applications. Those likely will expand toward general AI in the coming decades, presenting significant strategic, organizational, and even existential concerns. Further, how natural humans respond and engage with increasingly advanced, even superintelligent AI as well as a singularity event will feature disruptive, transformative impacts on security affairs and even at a philosophical level discerning what war is.

Keywords: artificial intelligence, AI, warfare, singularity, transhumanism, singleton, human-machine teaming

Warfare has always been changing as humans develop new ideas, technology, and otherwise expand their range of abilities to manipulate reality to their advantage and creativity. Just as Homo sapiens prove astoundingly adaptive and clever in how to produce art, beauty, and generously extend quality of life for the species, they continue to also be devastatingly capable of conjuring up with evermore horrific and powerful ways to engage in organized violence against those they are in competition or conflict with. Yet, the twenty-first century is wholly unique in that humanity now has the technological keys to unlock something previously unreachable. Civilization, human existence, and perhaps war may move into what previously could only be captured in fantasy, science fiction, or ideological promises and magic.

The title of this article is provocative and draws inspiration from Elon Musk’s comment on how humans will be rapidly outpaced by advanced artificial intelligence (AI). Musk remarked that “human speech to a computer will sound like a very slow tonal wheezing, kind of like whale sounds” due to expected lightning fast processing speeds and how AI will move from specialized applications into general intelligence contexts where humans are slower, more error-prone, and unable to compete in every conceivable way.1 This article operates as a thought piece, designed to stimulate deep thinking not on the short-term or localized contexts for immediate wars of the next decade, but onward and outward to radical, potentially existential concerns of where humans and warfare technology might lead to in a century, perhaps less.

Previous efforts by military theorists on how technological developments will change warfare fundamentally fixate exclusively upon humans directing said change so that new wars demonstrate human mastery beyond earlier warfare efforts of less advanced human combatants. This orientation on humanity at war with their own species is consistent, whether one considers the development of the stirrup, firearms, the Industrial Revolution, or even the First Quantum Revolution and the detonation of atomic weapons in 1945. Throughout all these transformative periods, warfare characteristics, styles, and indeed the scale and scope of war effects have changed, but humans remained the sole decision makers and operators central to all war activities. The key distinction in how advanced (likely general AI, which can match or exceed human cognitive abilities in all possible ways) intelligent machines and/or human-machine teaming (the rise of transhumanism) may develop is that future battlefields may push human decision makers and even operators to the sidelines, including entirely removing from any direct involvement in some potential war developments as this article will explain. While the targets of such a war may still include human populations and nations, the battlefield may finally become untenable for natural-born human cognition, survivability, and capability. This would be a dramatic shift from the last 40 centuries or more of human-directed, human-waged warfare where technology remained a tool firmly in the grasp of a hand made of flesh and bone.

We are poised, if we can just survive the next few decades where all sorts of modern existential threats remain horrifically available—for a new chapter in humanity and organized violence. Indeed, Homo sapiens will shift from constructing more sophisticated and lethal means to impose behavior changes and force of will (security, foreign policy, and warfare) to one where the means become entirely dissimilar, emergent ends in themselves. Our tools of warfare will be able to think for themselves and think about us, as well as think about war in starkly dissimilar, likely nonhuman terms. Whereas war has been an exclusively human created, socially constructed, and human exercised phenomenon, how we frame what war is (and is not) revolves around what humans believe it to be.2 This may not apply to nonhuman entities, nor would it be impossible for a superintelligent artificial entity to conceptualize something currently beyond our own violent imaginations. Unlike when we split the atom and quickly weaponized that technological marvel, there will not be the same control and command of weapons that can decide against what we wish, or even what we might be able to grasp in complex reality.

Humans will transition from ever-capable masters of increasingly sophisticated war tools toward less clever, less capable, and insufficient handlers of an increasingly superior weaponized capability that in time will elevate, transform, or potentially enslave (or eliminate) Homo sapiens into something different, possibly unrecognizable. War, as a purely human construct that has been part of humanity since inception, will change as well. Note that war is not interchangeable with warfare, in that war is the human-designed, socially constructed, and physically waged activities of organized violence, while the process of engaging in any manifestation of war becomes the exercise of warfare per the established belief system in operation by those using a particular social paradigm.3 Humans currently use technology and knowledge to understand what war is and subsequently wield technologically generated abilities derived from resources to produce desired effects within complex reality that accomplish various desires of politics and societies. The dramatic shift of technology from a human-controlled tool for effect into its own designs and motives to accomplish unrelated (or unimagined) ends to itself will be potentially the ultimate (or final) change in warfare from a human-centered perspective. This could occur gradually, even invisibly, or suddenly and with profound disruption. These changes will not occur overnight, nor likely in the next decade or two, which sadly renders such discussions out of the essential and toward the fantastical. For the military profession, this reinforces a pattern of opting to transform to win yesterday’s war faster instead of disruptively challenging the force to move away from such comfort and familiarity toward future unknowns that erode or erase favorite past war constructs.4

The next century will not be like past periods of disruptive change such as the development of firearms, the introduction of internal combustion engines, or even the arrival of nuclear weapons. While today’s semiautonomous cruise missile cannot suddenly decide to go study poetry or join an antiwar protest, future AI systems in the decades to come will not be bounded by such limitations. Past revolutions in warfare involve technological and sociological transformations that replaced a legacy mode of human-directed warfare with a newer, more lethal, faster, yet still human-centered warfare process. The upcoming revolution in artificial intelligence and human-machine teaming in warfare may become the last revolution that humans will start and possibly one that they are unable to finish or influence the path beyond what they can conceptualize or articulate at whale song speeds.

As such, critics might dismiss such thoughts outright as science fiction claptrap that is inapplicable to contemporary concerns such as the Russian invasion of Ukraine or the saber-rattling of China over Taiwan. Such a reaction misses the point, as the AI enabled war tools of this decade are like babies or toddlers compared to what will likely develop several decades beyond our narrow, systematic viewpoints. In developing defense areas such as cyberspace, deep ocean locations, and space, humans are ill-equipped to function in these spaces.5 The human body is not designed for these areas, and faster, more robust AI have myriad operational advantages just now coming into what is possible. Codeveloper of Skype and computer programmer Jaan Tallinn states it bluntly: “silicon-based intelligence does not share such concerns about the environment. That’s why it’s much cheaper to explore space using machine probes rather than ‘cans of meat’.”6 In turn, this is why militaries perpetually chase the next silver bullet and secure funding to conduct moon shots, and these already include advanced AI weaponized systems that may replace almost every human operator on today’s battlefield. The new AI system, if not developed and secured by our side, surely will be designed by competitors, ensuring a perpetual AI arms race driven by national self-interests over any potential ethical, moral, or legal complications.

Yet, when we seek to develop new weapons of war without putting in the necessary long-term, philosophical work on where we might end up, we fall into the trap that Der Derian warns of for societies excited about new technologies but uninterested in engaging in deep philosophical ponderings on the consequences of those new war tools:

When critical thinking lags behind new technologies, as Albert Einstein famously remarked about the atom bomb, the results can be catastrophic. My encounters in the field, interviews with experts, and research in the archives do suggest that the [Military Industrial Media Entertainment Network], the [Revolutions in Military Affairs,] and virtuous war are emerging as the preferred means to secure the United States in highly insecure times. Yet critical questions go unasked by the proponents, planners, and practitioners of virtuous war. Is this one more attempt to find a technological fix for what is clearly a political, even ontological problem? Will the tail of military strategy and virtual entertainment wag the dog of democratic choice and civilian policy?7

This article presents a framing of how nations currently understand the ever-developing relationship between themselves and artificially intelligent-enabled machines on the battlefields of today and where and how those likely will shift in the decades to come. Some developments will retain nearly all of the existing and traditionally recognized hallmarks of modern warfare, despite things speeding up or becoming clouded with disturbingly unique technological embellishments to what remains a war of political and societal desires to change the behaviors and belief systems of others. Other paths lead to never-before-seen worlds where humans become increasingly delegated to secondary positions in future battlefields and perhaps booted off those fields entirely. War, as a human creation, may cease to be human, and morph into constructs alien or incomprehensible to the very creators of organized violence for socially constructed wants.

More than 40 Centuries of Precedence: War Is a Decidedly Human Affair

Humans have for tens of thousands of years curated and inflicted on one another a specific sort of organized violence known as war that otherwise does not exist in the natural world. More than 30,000 years ago, a cognitive revolution occurred that set into motion the rise of humans as a species not entirely dependent on biology, with historical narratives needed to explain developments and accomplishments.8 Prehistoric humans learned how to harness fire, create basic tools, shelter from the elements, and began a gradual journey toward ever-increasingly sophisticated societies.9 Change occurred gradually, with agriculture and the establishment of cities commencing around 10,000 years ago; this would produce the first recorded wars that differed from other types of violence.10 The invention of writing (3,000 years ago) would eventually shift oral accounts of these wars into more refined, structured forms that could be studied as well as extended beyond internalization of each living generation.11 Without this cognitive revolution, humans would not have been capable of creating societies, belief systems, rules of law, politics, religions, or war. War is a decidedly human invention, and it has been wielded by human desires, beliefs, symbols, and conceptual models exclusively since its inception. We created it, use it, and own it, at least for now.

Yet, across these thousands of generations of Homo sapiens that would collectively produce modern societies of today, change occurred quite slowly until the last 500 years where a scientific revolution propelled Western Europe from obscurity into a technological, economic, and imperial juggernaut.12 Muscle and natural power (wind, fire, water) were the primary energy source for much of the collective human experience of warfare, with technological advancements only occurring in the last several hundred years with the invention of scientific methods and the Industrial Revolution that followed. Fossil fuels soon replaced muscle power, and the chemical power of gunpowder would replace edged weaponry with bullets, artillery, and more. Steam locomotion gave way to faster systems such as internal combustion engines and eventually nuclear power.13 Technology as well as organizational, cultural, and conceptual things have changed dramatically across this vast span of time, but humans have forever remained the sole decision maker in every act of warfare until very recently. This is where things will accelerate rapidly and potentially we may be entering the last century where humans even matter on future battlefields at all.

As soon as early humans realized how to manipulate their environment through inventing tools, they gained an analog function to greatly increase their own lethality to include waging war upon one another. The tools have indeed changed, but the relationship of the human to the tool has remained firmly in a traditional ends-ways-means dynamic. Humans use technology, communication, and organization to decide and act to attempt to accomplish goals through various ways and using a wide range of means at their disposal. Until the First Quantum Revolution that would coincide with the Second World War, humans were the sole decision makers at the helm of quite sophisticated yet entirely analog machines of war.14 Once computers first became possible (beyond earlier analog curiosities), humans gained something new within their decision-making cycle for warfare activities from the tactical up through even grand strategic levels—the artificially intelligent machine partner. At first, such systems were cumbersome, slow, and could only perform calculations, but over time they have migrated into central roles for how modern society now depends on this technology for a wide range of effects.15 The rise of AI brings with it the first encounter for humanity of an entity with the potential to cooperate, collaborate, compete, and perhaps leap well beyond our own conceptual limits in all endeavors to include warfare.

The Battlefield Suddenly Gets a Bit More Crowded

Artificial intelligence has many definitions, and modern militaries often are preoccupied with narrow subsets of what AI is and is not, according to competing belief systems, value sets, as well as organizational objectives and institutional factors of self-relevance. Peter Layton provides a broad and useful definition: “AI may do more- or less- than a human . . . AI may be intelligent in the sense that it provides problem-solving insights, but it is artificial and, consequently, thinks in ways humans do not.”16 Layton considers AI more by the broad functions such technology can perform than by its relationship to human capabilities. This indeed is often how current defense experts and strategists prefer to frame AI systems in warfare; the human is teamed with a machine that provides augmentation, support, and new abilities to perform some goal-oriented task that non-AI enabled warfighters would be insufficient or less lethal performing.

Artificial intelligence is also broadly distinguished into whether it is narrow or general with respect to human intelligence. Narrow AI equals or vastly exceeds the proficiency that the best human is capable of doing for specific tasks within a particular domain and only in clearly defined parameters that are unchanging. Narrow AI can now beat the best human players of chess and other games, with IBM’s Watson defeating the best Jeopardy! trivia game players in 2011 as an example. However, narrow AI is fragile, and if the rules of the game were changed or the context transformed, the narrow AI programming cannot go beyond the limits of the written code.17 General AI, as a concept and benchmark yet realized in any existing AI system, must equal or exceed the full range of human performance abilities for any task, in any domain, in what must be a fluid and ever-changing context of creativity, improvisation, adaptation, and learning.18 Such an AI is decades away, if ever possible. Just as likely, a devastating future war waged with weaponized AI short of general intelligence could knock society back into a new Stone Age, or perhaps humanity might drift away from AI-oriented technological advances seeking general AI capabilities.19 Existential warfare could come at the hand of humans directing slightly less intelligent AI systems, or the dynamic could flip and the slightly less intelligent humans could be used as tools, targets, or for purposes beyond our imagination.

AI is constantly being developed, with many military applications already well established and those on the immediate horizon for battlefields in the next decade. Much of what currently exists was produced in what is called “first-wave AI”—narrow programming created in conjunction between the computer designers writing the code and the experts in the field or task that the narrow AI system is attempting to excel at. More recently, “second-wave AI” uses machine learning where “instead of programming the computer with each individual step . . . machine learning uses algorithms to teach itself by making inferences from the data provided.”20 Machine learning is powerful, working in a special way where human programmers do not have to set it up. Yet, this creates the paradox that machine learning quickly can exceed the programmer’s ability to track and understand how the AI is learning.21 This sort of machine learning can occur in either a supervised or unsupervised methodology, where supervised learning systems are given labeled and highly curated data. The AI is told what to do, how to accomplish it, and progress is diligently monitored and analyzed by human supervisors. This is time and resource intensive, but supervised machine learning can achieve extremely high performance in narrow applications.

Unsupervised learning unleashes the AI and the AI identifies patterns for itself, often moving in emergent pathways well outside the original expectations of the programmer. Layton remarks: “An inherent problem is it is difficult to know what data associations the learning algorithm is actually making.”22 IBM’s Adam Cutler, in a lecture to military leadership at U.S. Space Command, provided the story of how two chatbots created by programmers at Facebook quickly developed their own language and began communicating and learning in it. The Facebook programmers shut the system down as they had lost control and could not understand what the chatbots were doing. Cutler stated that “these sorts of developments with AI are what really do keep me up at night.” His comment was both serious and simultaneously elicited audience laughter, as the panel question posed was: “What sorts of things keep you up at night?”23

While the instance of chatbots going rogue with a new language might be overblown, Cutler and other AI experts warn of the dangers of unsupervised learning in AI development, and caution that while anything remotely close to general AI intelligence is still far-off in the future, there are profound ethical, moral, and legal questions to begin considering today.24 With this brief summary of AI put into perspective, we shall move to how the military currently understands and uses AI in warfare, and where it likely is morphing toward next.

How Human-Machine Teaming Is Currently Framed

AI systems can operate autonomously, semiautonomously, or remain in the traditional sense where, just like your smartphone or smart device awaits your command, operate in a passive mode of activity. While it may seem unnerving that your Alexa device is perpetually listening to background conversations, it is programmed to scan for specific words that trigger clearly defined and quite narrow actions. While passively awaiting directive cues and proactive (semiautonomous, autonomous) modes feature different relationship dynamics between the AI and humans, the following three are well recognized in current military applications of AI systems.25

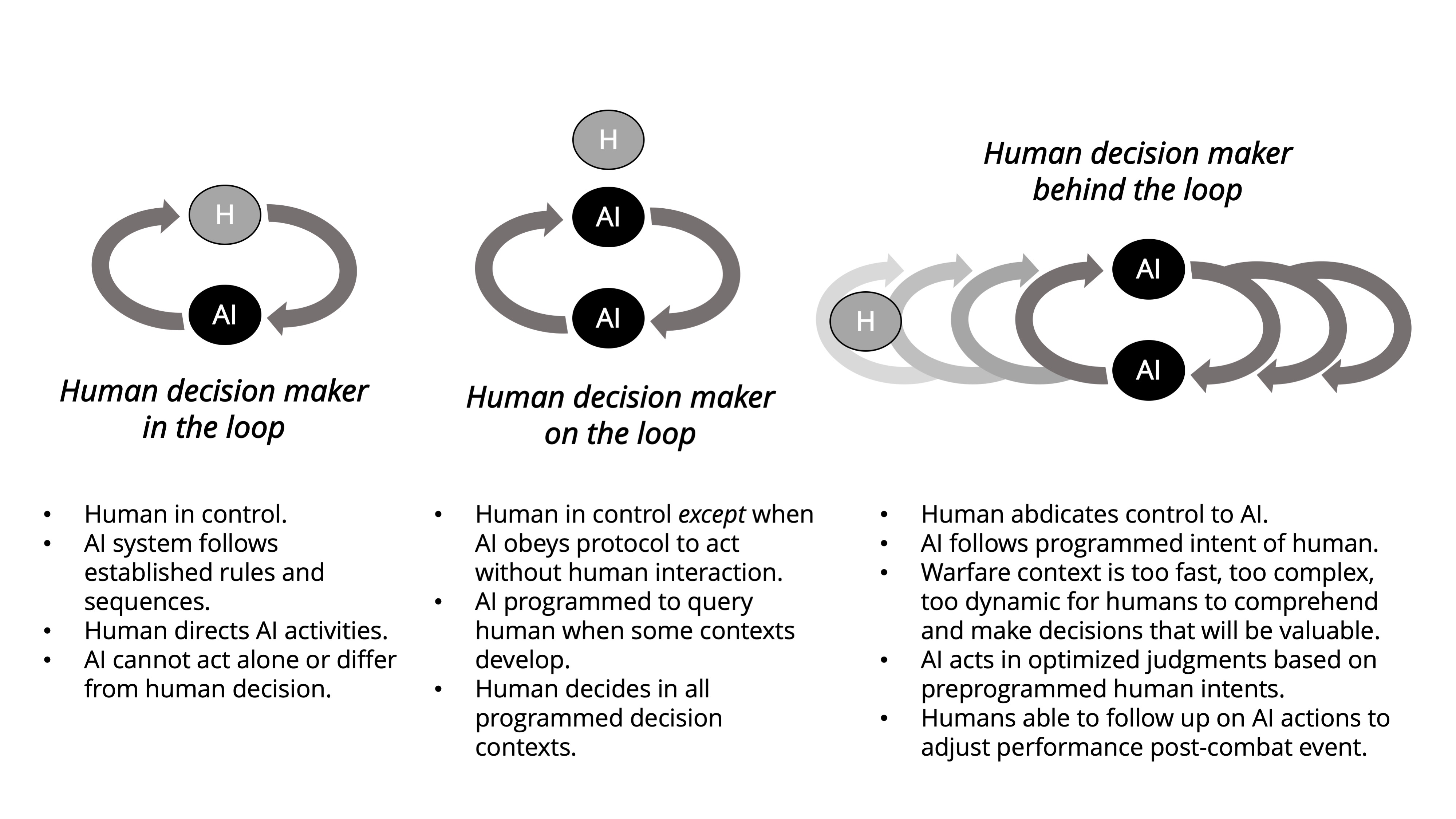

The original mode used since the earliest protocomputer enablers (as well as most any analog augmentation in warfare) positions the human as the key decision maker in the cycle of thought-action-reflection. This is best known as human-in-the-loop, and it expresses a dynamic where the human is central to the decision-making activities. The AI can provide exceptional contributions that exceed in narrow ways the human operator’s capabilities, but that AI does not actively do anything significant without a design where the human intervenes and provides guidance or approval to act.

While the human-in-the-loop remains the most common and, for ethical, moral, and legal reasons the most popular mode of human-machine teaming for warfare, a second mode has also emerged with recent advances in AI technology.26 Termed human-on-the-loop, the AI takes a larger role in decision making and consequential action where the human operator is either monitoring activities, or the AI system is programmed to pause autonomous operations when particular criteria present the need for human interruption. In these situations, the AI likely has far faster abilities to sense, scan, analyze, or otherwise interpret data beyond human abilities, but there still are fail-safe parameters for the human operators to ensure overarching control. An autonomous defense system might immediately target incoming rocket signatures with lethal force, but a human operator may need to make a targeting decision if something large like an aircraft is detected breaching defended airspace.

A third mode is only now coming into focus, and with greater AI technological abilities as well as increasing speed, scale, and scope of new weaponry (hypersonic weapons, swarms and multidomain, networked human-machine teams) a fully autonomous AI system is required. Termed human-out-of-the-loop, this differs from what is nonpejoratively referred to as dumb technology such as airbags that automatically activate when certain criteria are reached. Truly autonomous, general intelligence AI systems would replace the human operator entirely and are designed to function beyond the cognitive abilities of even the smartest human at what are currently narrow parameters. While many use out-of-the-loop or off-the-loop, this article substitutes behind-the-loop to introduce several increasingly problematic human-machine issues on future battlefields. Figure 1 illustrates these three modes below.

An autonomous AI system functioning in narrow or even general AI applications will, as technological and security contexts demand, potentially move from supervised to unsupervised machine learning profiles that access ever growing mountains of data on the battlefield. Consider the average daily volume of new tweets by worldwide Twitter users that average 330 million monthly users with 206 million of those users tweeting daily, producing a daily average of more than 500 million tweets worldwide in hundreds of different languages and countries.27 It would be impossible for human-in-the-loop monitoring, while human-on-the-loop is also expensive, slow, and often subjective. Twitter, like many social media platforms, has many autonomous AI systems filtering, analyzing, and often taking down spam, fake accounts, bots, and other harmful content without human intervention. This is not without risks and concerns, yet Twitter quality control is inevitably chasing behind the autonomous work of far faster, future AI systems that should scale to enormous levels beyond what an army of human reviewers might possibly match. However, fighting spam bots and fake accounts on Twitter is not exactly the same as autonomous drones able to decide on lethal weapon strikes independent of human operators.

Figure 1. Contemporary framings for human-machine teaming in warfare

Source: courtesy of the author, adapted by MCUP.

Human-machine teaming currently exists in all of the three representations in figure 1, with the preponderance in the first depiction where human operators remain the primary decision makers coupled with AI augmentation. Drone operators, satellite constellations, advanced weapon systems that auto-aim for human operators to decide when to fire, as well as bomb-diffusing robots worked by remote control are common examples in mass utilization. Humans on the loop abound as well, with missile defense systems, antiaircraft, and other indirect fire countermeasures able to function with human supervision or just with human engagement for unique conditions outside normal AI parameters. The increased sophistication and abilities of narrow AI systems as well as the frightening speeds achieved by hypersonic and advanced weaponry and the rise of devastating swarm movements that collectively would overwhelm any single human operator may now be addressed with autonomous weapon systems, if militaries and their political oversight concur with the risks. These are not without significant ethical, legal, and technological debate in security affairs.

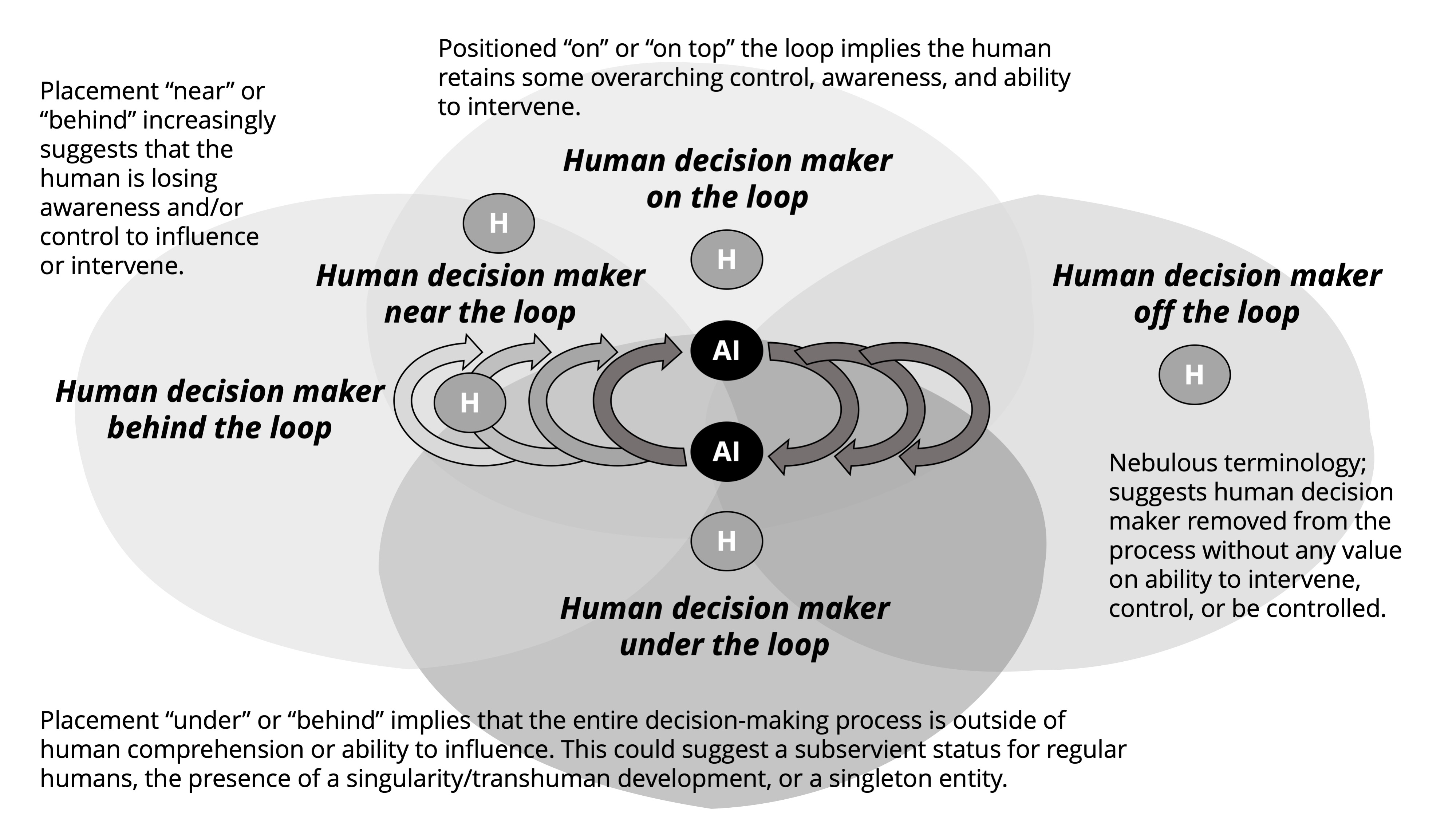

Figure 2. Implications of metaphors in human-machine teaming descriptions

Source: courtesy of the author, adapted by MCUP.

How we express the human-machine teaming dynamic requires a combination of our conceptual models along with precise terminology that is underpinned by metaphoric devices. In figure 2, many of the terms currently in use as well as some new ones introduced in this article place the human on the loop, off the loop, near the loop, behind the loop, or potentially under the loop depending on the warfare context and metaphoric configuration of the loop participants. Aside from the in the loop configuration that has been the foundational structure for human decision makers to direct command and control with an AI supporting system, all these other placements for a human operator reflect changing technological potentials as well as the increasingly uncertain future of warfare. Such variation and uncertainty imply significant ethical, moral, legal, and potentially paradigm-changing, existential shifts in civilization.28 Figure 2 attempts to systemically frame some of these tensions, differences, and implications with how militaries articulate the human-machine team construct. The autonomous weapon acts as a means to a human designed end in some cases, whereas in other contexts the means becomes a new, emergent, and independently designed end in itself, beyond human contribution. Note that in each depiction of a human, that operator is assumed to be an unmodified, natural version augmented by the AI system.

Yet, the contemporary debates on how humans should employ autonomous weapon systems is just the latest evolution in human-machine teaming, where narrow AI is able to do precise activities faster and more effectively than the best human operator. Narrow AI applications in warfare illustrate the current frontier where existing technology is able to act with exceptional performance and destruction. However, no narrow AI system can match human operators in general intelligence contexts, which still compose the bulk of warfare contexts. For the next decade or two, human operators will continue to dominate decision making on battlefields yet to come, although increasingly the speed and dense technological soup of future wars will push humans into the back seat while AI drives in more situations then previously. It is the decades beyond those that will radically alter the human-machine warfare dynamic, potentially beyond any recognition.

The Event Horizon and Technological Revolutions: Breaking the Paradigm

This is potentially the last century in a massive string of centuries where humans are the primary decision makers and actors on battlefields. Figures 1 and 2 represent what will be a gradual shift from human operators being central to decision making (in the loop) to an ancillary status (on the loop) and subsequently to a reactive, even passive status (off the loop, behind the loop) as technological developments influence future battlefields to be unsafe for human decision speeds as well as the presence of human combatants.29 Already, unmanned aviation, armored vehicles, and robots for a range of tactical security applications are in service or development that will replace more human operators with artificial ones that move faster, function in dangerous contexts, and are expendable with respect to the loss of human lives. While current ethical debates pursue where the human must remain in the kill chain for decisions of paramount importance, this assumes that the human still possesses superior judgment, intelligence, or other cognitive abilities that narrow AI systems cannot replace. If the coming decades bring forth advances in general AI to rival or exceed even the smartest human operators, those ethical concerns will be eclipsed by new ones.

Even the best human operator has theoretical biological, physical, and emotional limits that cannot be enhanced beyond a certain known limit.30 Hypersonic weapons and swarm maneuvers of many AI machines pose a new threat, coupled with the increased speed of production and replacement through advances in 3D printers, cloud networks, constellations of smart machines, and more.31 The natural-born human can be modified through genetics, cybernetic enhancement, and/or a human-machine teaming with AI systems to produce a better hybrid operator team.32 For the coming decades, this likely will be the trend.33 Yet, as figure 2 presents, the legacy human-machine teaming relationships framed in figure 1 will be replaced. How far and whether there are long-term ethical, moral, and legal consequences on modifying humans for military applications is another area of concern in that much of the research is just starting or is still largely hypothetical.

There are two significant transformations that may render most of figure 1’s human-machine teaming configurations obsolete. These concepts are hypothetical and likely many decades away, if even possible. The first is one where the natural born, unmodified human is insufficient to participate in future decision-action loops. They are outperformed by the theoretically enhanced human, whether this is achieved genetically, cybernetically, and/or through AI networking modification. Here, what could be called a Supra sapien outperforms any regular human opponent in every possible battlefield measurement. These enhanced humans would essentially break the contemporary human-machine teaming model in that their superintelligent abilities would be incompatible with how our militaries currently understand and frame decision-making relationships about how natural-born humans cope with battlefield contexts. This requires further elaboration.

Bostrom, in Superintelligence: Paths, Dangers, Strategies explains various paths to such a superintelligent, enhanced human that is vastly superior to even the most talented natural-born human specimen. Biological enhancement of human brains through genetic modification, biomedical enhancements, or hypothetical iterated embryo selection of select genotypes using stem cells to “accomplish ten or more generations of selection in just a few years” could produce humans with intelligence beyond traditional ways to measure such abilities, even dwarfing geniuses such as Isaac Newton and Albert Einstein.34 A cybernetically enhanced human would have direct brain-computer interfaces that again hypothetically could create cognitive improvements whether the hardware is inserted into human tissue or linked to external systems that compliment or enhance the human wetware doing the thinking.35 A networked AI enabled group of humans would work collectively, such as the fictional villain Borg collective from the Star Trek: The Next Generation television series. Technologically linked humans able to reduce bureaucratic drag, speed up the slowest individual human links in the chain, and permit AI data collection at vast scales could generate a collective superintelligence that no single natural-born human opponent could match.36 In any of these hypothetical developments of current research in genetic, cybernetic, and network-enabled research, such a possibility could flip the entire notion of what a human-machine team is for warfare applications. There is one remaining human-connected hypothesis, where any of these possible enhanced human entities moves beyond what makes us all human and becomes something alien in a new intersection of advanced technology and original human desires.

The term transhumanism covers this overlap between technological advancement and the modification of human beings to break free of the natural, slow evolutionary process. Biology still governs what each generation of humans can do physically, although medical science and technology continue to change the boundaries as humans manipulate many more aspects of what was previously out of our hands. Yet, regardless of if a new baby is conceived in a test tube or the old-fashioned way, the output still is a human being that will develop within a society and think like other humans. With transhumanism, there is a divide between what started out as a human and what has now transcended what humanity can conceptualize or even recognize as human in form and function. Transhumanism need not be directly associated with the rise of superior AI, as the two might be better understood in a Venn diagram influencing one another.37

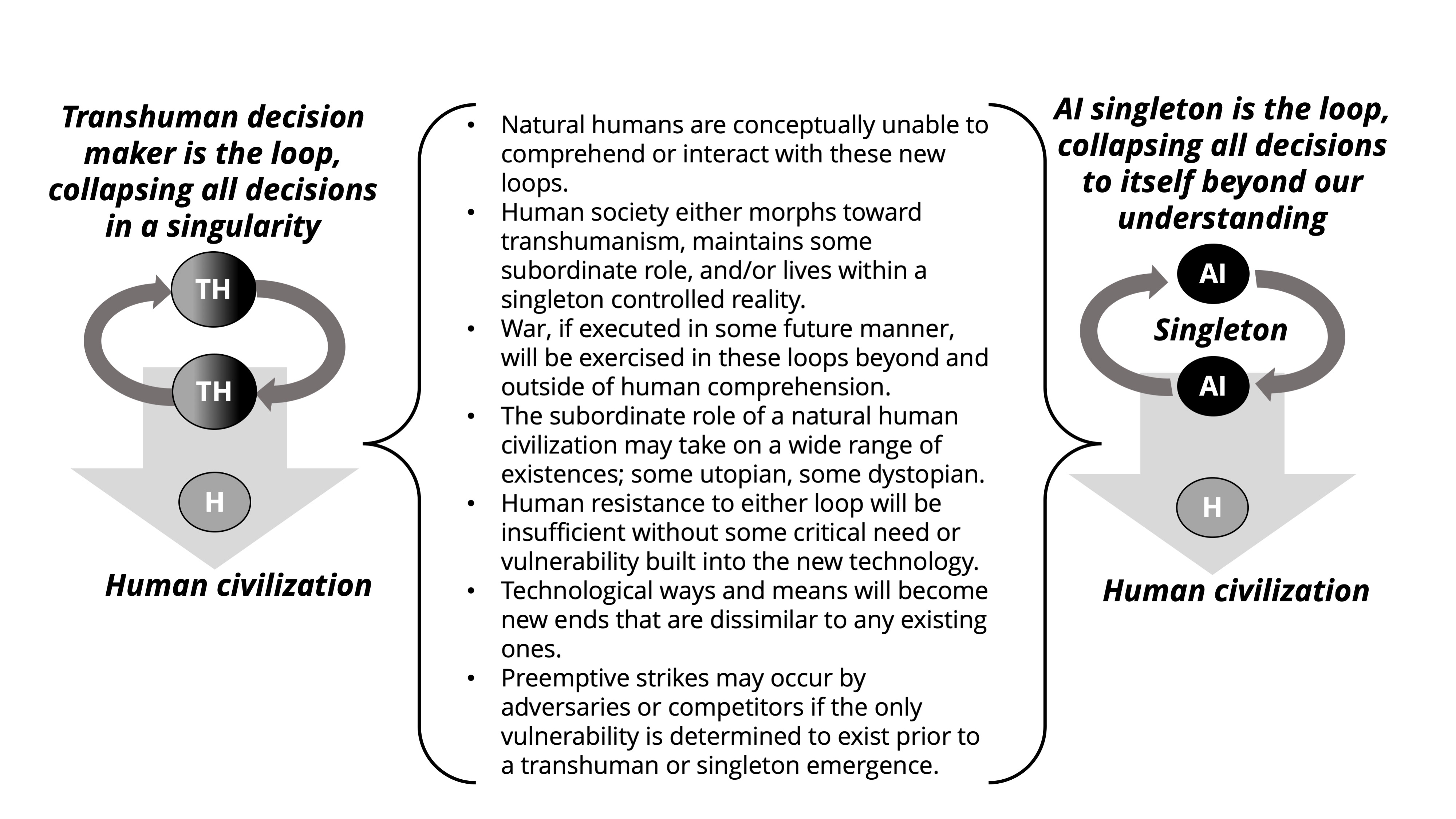

Technophiles suggest that at some advanced level, modified humans will reach a point where a singularity occurs, and suddenly these modified humans will exist on a new plane of reality that would arguably be inaccessible to natural, legacy human beings—as a transhuman entity could shed all organic habits and potentially become beings of pure information38 This transhuman leap is illustrated on the left side of figure 3. The other extreme transition is depicted below on the right side and is where advanced AI reaches and then vastly exceeds general human intelligence. One comes from human stock; the other is created by humans but is artificial in design and expression. Alternatively termed strong AI, such superintelligent general AI remains entirely hypothetical but is anticipated by virtue of superiority to human cognition to be uncontrollable once developed by leading AI theorists today such as Ray Kurzweil.39 Such a superior entity would potentially convince societies (by reason, force, or manipulation) that it should lead and decide for all matters of importance, including defense.

The concept of an AI singleton comes from Nick Bostrom, who explained that a singleton is an entity that becomes the single decision-making authority at the highest level of human organization. This usually means the entirety of human civilization, whether still limited to one planet or possibly spread across space in multiple colonies. Such an entity is considered “a set with only one member,” where presumably a general AI entity that could rapidly advance from human-level intelligence beyond all biological, genetic, or otherwise non-AI limits into a superintelligence well past any human equivalent.40 This brings into question whether the arrival of a singleton would directly dismantle human free will or the ability for humans to retain a status as a rational and biological species endowed with self-awareness.41 The singleton entity, as a superintelligent AI entity, would sit above legacy humans in a new decision loop that would take control of human civilization just as a suggested transhuman manifestation might. Both concepts in figure 3 deserve greater explanation below. Note that with the transhuman entity, all of human civilization would remain under the loop, with the transhuman singularity blurring our loop model into where the transhuman entity becomes the entire loop. Respectively, the AI singleton, shedding all human attempts at control, also becomes the entire loop with human civilization placed under it.

Granted, a singleton could just be a fantastic individual or group that somehow manages to effectively take total control of human civilization (some future world government). However, in the entire history of human existence, this has yet to happen except in limited, isolated, and temporary conditions that fall short of the singleton constant. Bostrom highlights the totality of what a real singleton would be: “[a singleton’s] defining characteristic . . . is some form of agency that can solve all major global coordination problems. It may, but need not, resemble any familiar form of human governance.”42 That no organic or natural singleton composed of one or several humans has yet in human history assumed any lasting form of a singleton indicates that for now, unmodified humans have thus far not produced any lasting or comprehensive (humanity-wide) singleton manifestations.43 This may change with the rise of strong AI that can conceptualize well past existing cognitive limits and be able to decide and direct with successful outcomes systemically across the needs of an entire civilization. An entity that can outperform the best and brightest humans in every conceivable way, in any contest, at fantastic speeds and scale would seem either magical or godlike. Such concepts seem ridiculous, but many involved in AI research forecast these hypothetical developments as increasingly unavoidable and increasing exponentially over the next decades.44 People may grow comfortable with their smartphones able to beat them at games of chess, poker, and pool, but will they agree to an AI that can outwit, deceive, or create and produce on every level (including on the battlefield) beyond their best efforts?

The singleton as depicted in the above figure offers the profound possibility that this entire shared socially constructed notion of war could be shattered and eclipsed by something beyond our reasoning and comprehension. Regular (narrow) AI may challenge both the supposed character and nature of future war, while a superintelligent singleton might break it completely.45 All humans would be under the loop in a singleton relationship where it assumes all essential decision making that governs and maintains the entire human civilization.46 This may in turn change what we comprehend as both “human” and “civilization,” or possibly in existential ways, how Homo sapiens remain a recognizable and surviving species.

Figure 3. Further down the AI rabbit hole and 2050–90 warfare?

Source: courtesy of the author, adapted by MCUP.

The other component in figure 3 is the transhuman loop where a transhuman (or more than one) become the loop just as a singleton assumes total decision-making control. Legacy frames for what the decision loop was (figures 1 and 2) become irrelevant here. A transhuman entity extends a related concept of a singularity that overlaps with a singleton in some ways while differing in others. A singularity, first introduced by mathematician Vernor Vinge and made popular in science fiction culture by Ray Kurzweil, will break with the gradual continuum of human-technological progress with an entirely new stage in human existence.47 It is considered a game changing, evolutionary moment where regular Homo sapiens would transform into a superintelligent, infinitely enhanced and possibly nonbiologically based technological fused entity.48 Transhumanism envisions “our transcending biology or manipulating matter as a necessary part of the evolutionary process.”49 The arrival of a technological singularity coincides with a rapid departure of the transhuman entity away from the original biological evolutionary track.

A singularity introduces the concept of transhumanism, where at a biological, physical, political, sociological, and ultimately a philosophical level, humanity should break the slow evolutionary barriers and leap beyond the slow, clunky genetic and environmental soup of existence that changes organic life over thousands of years. Yuval Harari, in explaining how the cognitive revolution some 30,000–70,000 years ago, declared our species “independent from biology” where humans could radically alter the world around them and how they would conceptualize a socially complex reality atop the physical one so that the species did not rely on evolutionary biology to gradually develop improved instincts, physical developments, and other hardware or hardwired adaptations.50 Thus, humans in the original cognitive revolution could develop complex ideas such as war and subsequently improve on the concept while waging it against fellow human adversaries.

Chimpanzees, in comparison, do engage in both predator-prey acts of localized violence as well as immediate and perhaps tactical acts of aggression for clear, immediate goals. Animals do not formulate strategies, nor produce languages, form religions, or develop political systems or laws, and they are entirely dependent on biology to give future offspring new advantages.51 Humans create these incredible constructs by conceptualizing and subsequently manipulating reality, or the complex reality of the natural world with a second order of socially constructed complexity infused atop.52 The singularity would theoretically create a second revolution in that the remaining biological, physical (both time and space), and sociological limitations would no longer exist for transhuman entities. They could rewrite their DNA; form entirely novel genetic combinations; redesign their consciousness in ways that defy any rational expectations for human life; build entirely alien bodies that violate certain natural laws that confine even the most cunning, resourceful natural humans; and engage in warfare in unrealized, unimagined, and yet-to-be-understood configurations.

The singularity could do this in minutes or days instead, depending on the degree of modification or enhancement. Or as Vernor Vinge explains, “biology doesn’t have legs. Eventually, intelligence running on nonbiological substrates will have more power.”53 This corresponds to raw cognitive powers of the evolutionarily honed human brain versus an entity that hypothetically could double its own abilities just as we might imagine in our minds what we fancy for dinner tonight. Bostrom offers a useful yet simplified summary with:

The simplest example of speed superintelligence [which is but one of several hypothetical superintelligences Bostrom offers] would be a whole brain emulation running on fast hardware. An emulation operating at a speed of ten thousand times that of a biological brain would be able to read a book in a few seconds and write a PhD thesis in an afternoon. With a speedup factor of a million, an emulation could accomplish an entire millennium of intellectual work in one working day.54

Should a singularity or singleton manifest, ordinary humans would be unable to compete. In both circumstances in figure 3, unmodified, natural-born humans would remain below the decision loops, becoming wards of a transhuman Supra sapien protectorate or a singleton superintelligent artificial entity. Assuming of course that humanity would be kept in some sort of existence and contribute something to this new ordered reality, all decision loops for essential strategic or security affairs would become as figure 3 illustrates. Enhanced humans, whether genetically, cybernetically, or those that achieve a transhuman state in other ways, would assume the decision loop and advance it in terms of speed, scale, and scope beyond anything a regular human could understand or participate in.55 This is where Musk’s warning that human thought and communication would be so slow it would sound like elongated, simplistic whale songs to entities with superintelligent abilities. Unlike the hypersonic missile dynamic where the weapon can maneuver at extreme speeds (unlike traditional missiles) making it much harder for a human to respond and adjust to, a transhuman or singleton entity comprehends thought as well as achieves action beyond the limits of even the smartest, fastest human operator. Theoretically, systems processing at such high speeds would experience reality in a way that reinforces Musk’s remark, as well as an earlier line from Commander Data, an android in the Star Trek: The Next Generation television show. While kissing his human girlfriend, she asked what he was thinking. He responded that he was reconfiguring the warp field parameters; analyzing the works of Charles Dickens; calculating the maximum amount of pressure he should apply to her lips; considering a new food supplement for his cat, Spot; and more. Jenna, his human date, was thinking about whether she could date an android.56

Technological development, as anticipated during the next century or less, may achieve either a singularity where human beings and their technological tools form a new transhuman entity, and, arguably, take concepts such as species and existence toward uncharted areas, or pure general AI may quickly pull itself into a level of existence beyond the comprehension of its human programmers. If either is a potential reality in the decades to come, how will war change? What might future battlefields become? What roles, if any, might human adversaries assume in such a transformed reality? Could humanity be doomed or potentially enslaved by technologically super-enabled entities that dehumanize societies of regular, natural humans? Could one nation unencumbered by ethical or legal barriers unleash superior AI abilities with devastating effects?57 What emergent dangers lurk beyond the simplistic planning horizons where militaries contemplate narrow-AI swarms of drones for future defense needs in the 2030s and 2040s?

Whale Songs of Future Battlefields: The Irrelevance of Natural-Born Killers

For several centuries, modern militaries embraced a natural-science inspired ordering of reality where war is defined in Westphalian (nation-state centric), Clausewitzian (war is a continuation of politics), and what Der Derian artfully termed the “Bacion-Cartesian-Newtonian-mechanistic” model.58 War has been interpreted along with a mechanical canonization of manufacturing, navigation, agriculture, medicine, and other “arts” in medieval and Renaissance thinking; Bacon’s “patterns and principles,” both early synonyms for rules, “emphasized that such arts [including military strategy] were worthy of the name.”59 Lorraine Daston goes on to explain:

The specter of Fortuna haunted early modern treatises like Vauban’s on how to wage war. In no other sphere of human activity is the risk of cataclysmic chaos greater; in no other sphere is the role of uncertainty and chance, for good or ill, more consequential. Yet many early modern treatises that attempted to reduce this or that disorderly practice to an art, none were more confident of their rules than those devoted to fortifications. This was in part because fortifications in the early modern period qualified as a branch of mixed mathematics (those branches of mathematics that “mixed” form with various kinds of matter, from light to cannonballs). Like mechanics or optics, it was heavily informed by geometry and, increasingly, by the rational mechanics of projectile motion.60

Modern military decision making remains tightly wedded to what is now several centuries’ worth of tradition, ritualization, and indoctrination to framing war as well as the process of warfare into a hard-science inspired, systematic-logic derived construct where centers of gravity define strengths and vulnerabilities universally in all possible conflicts, just as principles of war such as mass, speed, maneuver, objective, and simplicity are considered “the enduring bedrock of [U.S.] Army doctrine.”61 This comes from the transformational period where a feudal age military profession sought to modernize and embrace social, informational, and political change that accompanied significant technological advances.62 Daston adds to this, explaining: “In the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, the most universal and majestic of all laws were the laws of nature such as those formulated by the natural philosopher Isaac Newton in his Philosophiae naturalis principia mathematica in the late seventeenth century and the natural laws codified by jurists such as Hugo Grotius (1583–1645) and Samuel Pufendorf (1632–1694) in search of internationally valid norms for human conduct in an age of global expansion.”63 Natural sciences as professions would lead this movement, with medieval oriented militaries quickly falling into step.

The reason for this brief military history lesson is that today’s modern military that currently integrates and develops artificial intelligence with human operators still holds to this natural science ordering of reality including warfare. War is framed through human understanding and nested in both a scientific (natural science) and political (Westphalian nation-state centric) framework. This in turn inspires nearly everything associated with modern war, including diplomacy, international rules and laws of war, principles of war, treaties, declaration of war, the treatment of noncombatants, neutrality, war crimes, and many other economic, social, informational, and technical considerations.64

Central to our shared understanding of war is the human decision maker and human operators that inflict acts of organized violence upon adversaries in precise, ordered, and what is ultimately a socially governed manner. Even when strong deviation occurs in war, such actions are comprehended, evaluated, and responded to within a human overarching framework. The human decision maker as well as all operators cognizant of any action in war are held responsible, such as in the Nuremberg Trials held against defeated Nazi Germany military representatives in 1945–46. Never before has this dynamic of human centeredness been challenged until now, where the role of artificial intelligence and humans on the battlefield are already entering shaky ground.

An autonomous weapon system, granted full decision-making abilities by human programmers, presents an ethical, moral, and legal dilemma on whether it, its programmers, or its human operators should be held responsible for something such as a war crime or tragic error during battle.65 Current AI systems remain too narrow (in terms of AI), fragile, and limited in application to yet reach this level, for now at least. Increasingly powerful AI will in the coming decades replace human operators and, in some respects, even the decision makers. Humans, unless enhanced significantly, will become too slow and limited on battlefields where only augmented or artificial intelligence can move at the speeds, scale, and complexity necessary. Many of the natural laws of war could be broken or rendered irrelevant in these later and more ethically challenging areas of AI systems with general intelligence equal or beyond that of the human programmers.66 For instance, a general AI in a singleton manifestation would take over all decision making for any military conflict and potentially even exclude human operators from participating. Does war remain as it is now if humans are no longer part of it, despite humans socially creating war in the first place? These deeply troubling philosophical questions extend into religion, where a sentient AI with general intelligence that exceeds all human abilities could opt to join a human religion or design their own for AI. These developments could spell significant concern for both the human-centered and human-designed frames for war, religion, politics, culture, and more. The strategic abilities of nonhuman entities might exceed the comprehension and imagination of how humans for centuries have defined what war is.67 The arrogance that human strategists several centuries ago figured out the true essence of war in some complete, unquestionable way is but one institutional barrier preventing any serious discussion on what is to become of natural born operators and decision makers on future battlefields. The natural science conceptualization of war is only a few centuries old and is already under challenge by postmodernists even in current contexts where AI plays a subordinate, highly controlled role. Future AI that would reimagine war would theoretically disrupt or replace existing human beliefs concerning war and warfare.

The last cavalry charge occurred at least one war too late to make any difference, while many technologically inferior societies encountered horrific losses attempting traditional war tactics and strategies against game-changing developments.68 Arguably, with enough numbers, adversaries wielding significantly inferior weaponry can overcome a small force equipped even with game-changing technology, as the 25,000 Zulu warriors did defeat 1,800 British and colonial troops at the Battle of Isandlwana (22 January 1879). Yet, the Zulu offensive largely armed with iron-tipped spears and cow-hide shields lost several thousand warriors before eventually overwhelming their Martini-Henry breech loading rifle and 7-pounder mountain gun equipped opponents.69 Nuclear weaponry may have shifted war toward intentionally limited engagements between nuclear-armed (or partnered) adversaries since the 1950s, but even this nuclear threshold may be in question. Yet, military institutions typically resist change and instead are often dragged, kicking and screaming, into the adaptation of new technology while they attempt to extend the relevance of those things that they identify with but are no longer relevant in battle.70

The last natural born, genetically unmodified, and noncybernetically enhanced human battlefield participants are not realized yet, nor is the future battlefield selected. However, whenever and wherever that happens, humanity may end up being tested in ways unlike anything previously. Or humans that reach such a technological level of accomplishment might grant total decision-making capability to a singleton or to enhanced humans that have become transhuman entities able to think and act in future warfare contexts beyond natural-born, whale-song sounding human opponents. In either case, it is unlikely the slower, unenhanced human opponents will be much of a challenge if indeed the AI or transhuman advantages are that significant.

Antoine Bousquet, in detailing the rise of cybernetics for military collection, processing, and decision making during the Cold War, correlated the increased speed of jet-powered nuclear bombers with a need for computer-assisted data analysis of incoming radar and observation post reports, as well as faster outgoing directives for antiaircraft defenses such as interceptor fighters, land-based weapons, and strategic updates to leadership on whether to employ a counterstrike.71 The earliest computerized command, control, and communication network for this emergent military challenge launched in 1958 and was called SAGE (Semi-Automatic Ground Environment) that would provide real-time processing and respond to user inputs, all done over cathode ray tube technology. While SAGE was completed in 1963, it was already obsolete due to Soviet deployment of intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs) that made antiaircraft defenses rather inconsequential.72 In the high stakes, existential concerns of a potential nuclear war between the United States and the Soviet Union, human operators remained the ultimate decision makers even when coupled with these increasingly advanced computerized information processing systems.

Today, that dynamic remains largely unchanged, yet there is a growing creep of narrow focused AI systems taking more control and initiative to act without human supervision or interaction. These circumstances of AI-centric activities are localized to actions that an AI system has a low risk of complete malfunction, error, or other unexpected consequence of poor action, such as base defense of incoming rockets or emergency countermeasures for aircraft, vehicles, and submersibles. Artificial intelligence in general applications, once able to compete or exceed human abilities, may flip this dynamic, shifting humans to the role of the mine detector, where the human is on the loop or off the loop, moving too slowly and unable to conceptualize or act in a battlefield context where AI systems are swarming, networking, and engaging at speeds unreachable by the fastest human operator. Yet, there is today a fierce resistance to handing over significant decision making to machines in military culture.73 Part of this deals with control and risk, while the way militaries maintain identity, belief systems, and values also factor into how AI technology is being developed.

This presents an interesting change in future war as presented by Der Derian. While he focuses on technology, information, and human perception therein, he defines a virtuous war as “the technical capability and ethical imperative to threaten and, if necessary, actualize violence from a distance—with no or minimal casualties.”74 Der Derian frames the origin of virtuous war in the technological ramp-up and eventual Gulf War engagements between the United States and allies against Saddam Hussein’s Iraqi forces that had invaded and occupied neighboring Kuwait. Stealth aviation, smart bomb precision, along with grainy video feeds of enemy targets being struck saturated the news cycles, along with offering the promise that future wars would be largely bloodless, with few civilian casualties and low risk to friendly forces using such game-changing technology. This is often termed technical rationalism, and as Alex Ryan observes of the modern military, “technical rationalism combines a naïve realist epistemology with instrumental reasoning.”75 Modern militaries apply engineering logic toward complex security challenges with a preference toward advanced technology as the optimized solution set for accomplishing warfare goals. Donald Schön elaborates on this mindset: “practitioners solve well-formed instrumental problems by applying theory and technique derived from systematic, preferably scientific knowledge.”76 The promise of a technologically rationalized future for warfare is not new. General William C. Westmoreland addressed the U.S. Congress during the Vietnam War about the future and technological promises:

On the battlefield of the future, enemy forces will be located, tracked and targeted almost instantaneously through the use of data links, computer assisted intelligence evaluation, and automated fire control. With first round kill probabilities approaching certainty, and with surveillance devices that can continually track the enemy, the need for large forces to fix the opposition physically will be less important . . . I see battlefields or combat areas that are under 24 hour real or near time surveillance of all types. I see battlefields on which we can destroy anything we locate through instant communications and the almost instantaneous application of highly lethal firepower. I see a continuing need for highly mobile combat forces to assist in fixing and destroying the enemy. . . . Our problem now is to further our knowledge—exploit our technology, and equally important—to incorporate all these devices into an integrated land combat system.77

Virtuous wars have, according to Der Derian, closed the gap between an imagined or fantasized world of televised war and video game simulations with the gritty, brutal, and harsh reality of actual war. Der Derian explains that “new technologies of imitation and simulation as well as surveillance and speed have collapsed the geographical distance, chronological duration, the gap itself between the reality and virtuality of war.”78 Der Derian sees with this arrival of virtuous war the collapse of Clausewitzian war theory, the demise of the traditional sovereign state, “soon to be a relic for the museum of modernity . . . [or] has it virtually become the undead, haunting international politics like a spectre?”79 Der Derian addresses human social construction of reality and whether the hyper-information, networked, and technologically saturated world of today is drifting toward a new era of struggling between the virtual and the real, the original and the copy, as well as the copy and the constructed illusion that has no original source at all.80 To reapply Der Derian’s construct toward this AI future transformation of war, will the removal of humans both from operations as well as decisions in warfare create the final exercise in virtuous war, perhaps the last gasp of humanity into what war has been previously?

The total removal of humans from battlefields presents many emergent dilemmas ranging from accountability, ethical as well as legal responsibilities, and how intelligent machines can and will interact with human civilians on such future battlefields. Sidestepping the transhuman question for now, a purely artificial battlefield extending upward into all strategic and command authority decisions would move humans not just off or behind the loop, but under it. Would future wars even appear recognizable or be rationalized in original concepts? Might superintelligent machines be capable not just of winning future wars as defined by human programmers, but imagining and bringing into reality different forms and functions of warfare that are entirely unprecedented, unrealized, and unimagined?

The Calm Before the Storm: How It May Unfold

War has for thousands of years been a human design where as a species, Homo sapiens waged organized violence upon others of the same species in a manner unlike any other form of violence in nature. War is a human enterprise, until now. Advanced AI as well as the infusion of technology into how future humans exist will disrupt this history of violence. Genetically modified transhuman entities could gain unprecedented abilities in cognition, speed, strength, and resistance so that future battlefields would be far too dangerous for unmodified, original Homo sapiens. These super soldiers might have cyborg abilities or work in tandem with swarms of autonomous and semiautonomous war machines. However, in all of the enhanced human hypothetical paths beyond what exists today with gene modification, human-machine teaming with new tools like movement suits, armor, or surgical alteration with robotic implants, there is still a living human at risk on the future battlefield. Could there be a future where intelligent machines are so superior and lethal that no human being, regardless of enhancement, dare step foot upon that deadly landscape?81

The kinetic qualities of future war are more readily grasped, with science fiction already oversaturated with depictions of terminator robots and swarm armies of smart machines hunting down any inferior human opponent. Where advanced AI and transhuman developments are less clear is in the nonkinetic, informational, and social areas of warfare. In past wars, including the recent fall of Kabul in 2021 by advancing Taliban forces, information campaigns have been critical to gaining advantages over more powerful opponents. The Taliban invested for years in socially oriented, low-tech, grassroots influence campaign where they contacted Afghan security force personnel over phone calls, text messages, through social media, and by local, in-person means to gradually win over their ability to actively resist. The Taliban waged a sophisticated information campaign that would in the summer of 2021 collapse Afghan security resistance faster than ever anticipated by the high-tech, sophisticated Western security advisors planning the American withdraw. This momentous effort was done by Taliban operators in slow, largely person-to-person efforts through social engagements. Similar endeavors are increasing worldwide such as Chinese disinformation efforts targeting the Taiwanese population and a documented history of Russian disinformation activities against threats and rivals. Yet, most bot activity is easy to identify and generates marginal impacts. Narrow AI remains brittle for now but changes are coming.82

Consider a transhuman or general AI entity that could find, engage, and convincingly correspond not with one person at a time, but millions? How fast could a human population be targeted, saturated with messaging, and engaged in a convincing manner that would be indistinguishable from human conversation despite the status of an AI entity (or one transhuman engaging with far more targets) being deceptive or manipulative for security aims? In the rapidly developing areas of genetics, nanotechnology, and viral and microbe technology applied to warfare, how might AI systems incorporate these into human programmed strategic and operational objectives? For human societies and civilization in general, might future wars with AI able to think and act at or above human performance levels produce both the most fantastic of advantages and, if one is the target of such power, the most devastating of threats?

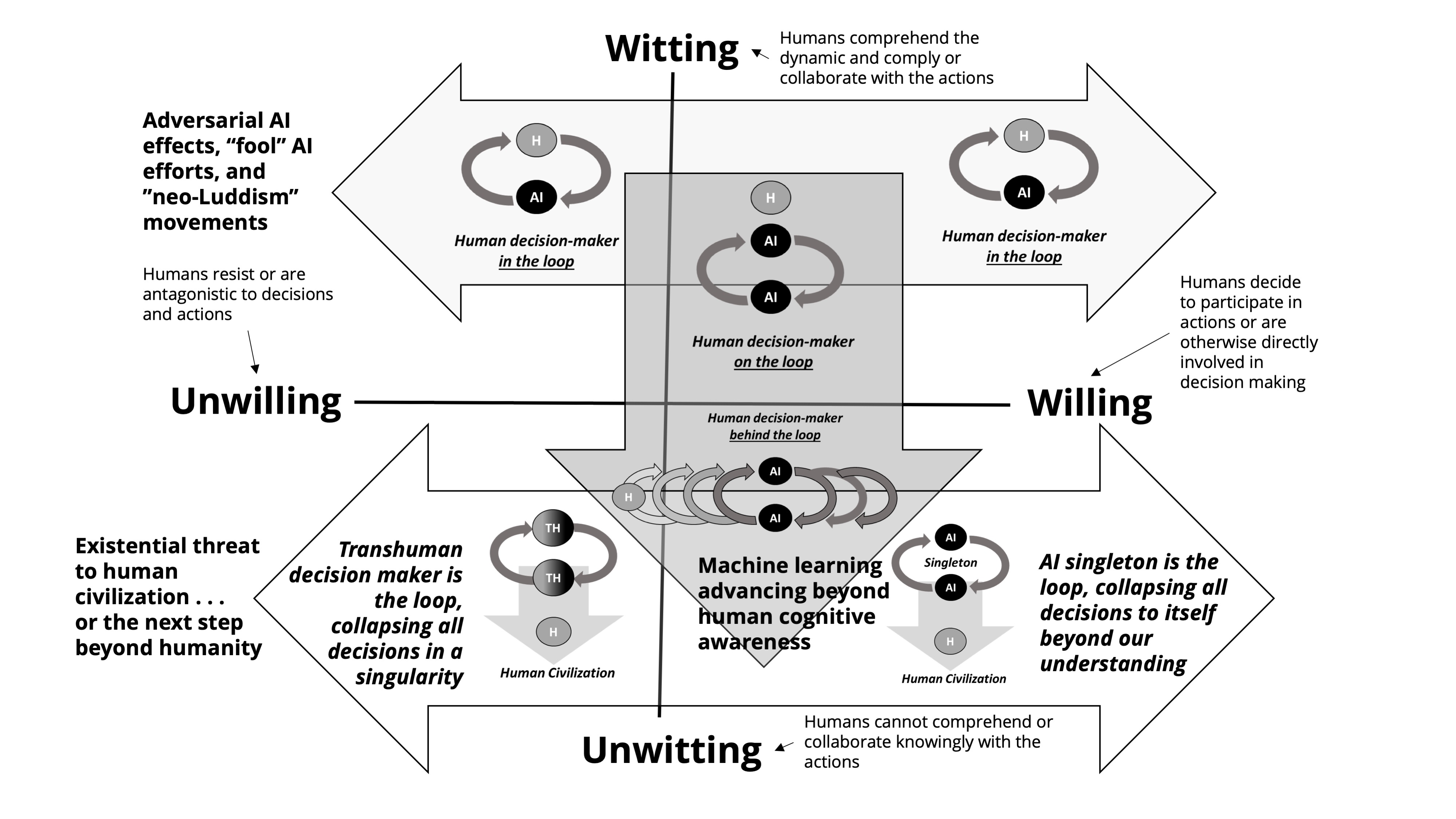

Figure 4. Synthesis of witting, willing human actions

Source: courtesy of the author, adapted by MCUP.

In figure 4, a systemic treatment is presented using a quadrant that positions on the vertical axis those that are witting or unwitting with a horizontal axis spanning the willing and unwilling. Witting humans understand the dynamic relationship between themselves and artificial intelligent entities (or transhuman ones) that together produce a decision-action loop. Those that are unwitting humans are unable to comprehend nor fully collaborate within the decision-action loop. Unwitting human participants simply are unable to conceptualize what is actually happening, whether due to speed, intelligence, multiplicity, or other reason that the AI entity is deciding and acting beyond human limits. The horizontal axis offers the tension between humans willing to participate and maintain such relationships with AI entities (or transhuman ones) and those that will resist and oppose any movement toward such a dynamic.

Figure 4 provides a lateral drift illustrated in the horizontal arrow (spanning witting/unwilling and witting/willing) where willing human enterprise with AI entities “in the loop” coincides with productive warfare and security outcomes. If human-machine teaming produces better military results, more of the human participants should accelerate a willingness to continue and strengthen such efforts (toward the witting/willing side). Conversely, adversaries that also use human-machine teaming in conflict successfully will force opposing humans into the unwilling direction. Adversarial AI effects such as fooling rival human-machine teams will provoke further resistance (toward the witting/unwilling side). Outside the traditional battlefield dynamic of “us versus them,” humans that perceive human-machine decision-action loops as a growing hazard or danger will assume some of the neo-Luddite positions and resist further investment in such technology. Impacts from war or conflict using AI systems may become beacons for technological activism to halt, prevent, or reverse such activities.

The downward pointing vertical arrow in figure 4 illustrates a progressive shift downward from the “witting-willing” quadrant to one of “willing-unwitting” where humans sit atop an increasingly sophisticated decision-action loop that has increasingly powerful AI. Over time, the human on the loop will eventually morph out of the witting into the unwitting, where that human is behind the loop of an ever-increasingly advanced AI system running all decisions with humans increasingly marginalized or excluded from the dynamic. This downward trend could bring with it an increased distrust, skepticism, or even conspiracy-theory fueled paranoia about advanced AI and their shifting interests in what is still human created, human directed warfare. The bottom horizontal arrow occupying the bottom two quadrants reflects the rise of superintelligent (in a general sense) entities that may be a transhuman extension beyond a singularity, or the rise of a pure AI singleton entity. In both instances, human civilization (unmodified, normal humans) would be subservient and in a protected (willing/unwitting) or perhaps oppressed status (unwilling/unwitting).83 The bottom arrow spans both the willing and unwilling quadrants as unmodified human populations could embrace or go to some existential war against such superior entities.84

One final takeaway that figure 4 provides is how the twenty-first century could be plotted upon the systemic framing shown. The top arrow portion could be applied to 2030 through perhaps the 2050–70 period, depending on the speed of AI enhancement and development toward general intelligence.85 The downward facing arrow might span the 2040–80 period to conservatively align with Bostrom’s survey results for a 50–90 percent chance of human-level machine intelligence attainment, while the bottom arrow could be theoretically positioned in the 2075–2100 period, again based on Bostrom’s survey results. Figure 4 is largely hypothetical, but given the available research, trends for AI and processing developments, and the strategic forward thinking of experts looking to the future of AI, such a figure 4 may only have uncertainty of not if but when these trends do manifest in warfare. We could be a half-century off from the worst existential scenario of a singleton AI that decides to move against human creators, or we could be several centuries away instead. Either one remains existential and deserving of deep consideration by militaries today.

Modern warfare should remain approximate to contemporary understanding of organized violence and waged mostly by humans for the coming decades, although a gradual blending of humans and increasingly intelligent machines will become pronounced as the decades progress. While impossible to speculate when, the rise of a singularity or a singleton would spell the end of what has been more than 40 centuries of a human-defined, controlled, and developed war paradigm. What would happen next is unfortunately outside of our imagination. The most likely outcome should be that whatever humans currently believe is appropriate and rational for warfare will be insufficient, irrelevant, or inappropriate for what comes next.

Conclusions: The End Is Nigh . . . or Probably Not . . . but Possibly Worse

This article was developed as a thought piece oriented not on the near-term and immediate security concerns where new technology might make incremental impacts and opportunities. Rather, this long-term gaze addresses the emergent paths that exist beyond the direct focus areas of most policy makers, strategists, and military decision makers charged with defending national interests today. Humanity has over many centuries experienced a slow rate of change, accelerating exponentially in bursts where game-changing developments (fire, agriculture, writing, money-based economics, the computer) have ushered in profound change. Yet, within much of that change, warfare has been a deadly contest between human populations equipped with varying degrees of technology and resources. The weapons were the means to human-determined ends in conflict. New technology represented new means and increased opportunities for creative ways to inflict destruction on one’s opponent.

The next shift with advanced artificial intelligence is already underway and will continue to unfold on the next few decades of battlefields with faster decision-action loops involving more sophisticated technology able to operate, organize, and influence at scales, speeds, and across multiple domains unlike in previous conflicts. This trend will gradually shift humans to atop the loop, and then in more contexts as risks are considered, behind the loop. Only the most dangerous, catastrophic decisions might remain exclusive to human decisions, until perhaps an adversary signals they have given it to a superior AI. Lastly, the loop may become a new end to itself, detached entirely from human creators. Arguably, cunning humans aware of this possibility could program devious means to prevent such a problem. Or enhanced humans with faster, stronger conceptual abilities could continue to hold the reigns of the artificial intelligence decision cycle. This is possible, but Bostrom devotes an entire chapter to his book on what is “the control problem,” and while he offers several ways to consider the programing, motivations, controls, kill switches, boxing methods, and more, he also acknowledges that “human beings are not secure systems, especially not when pitched against a superintelligence schemer and persuader.”86

If the rise of advanced AI systems as well as new technological gains for human enhancement spell grave risks for humanity, might some lessons be found in organized resistance to nuclear arms and nuclear weaponized nations? In 1953, U.S. president Dwight D. Eisenhower created the Atoms for Peace program that attempted to demilitarize the American international image as the first nation to use atomic weapons in war as well as the leading nuclear weaponized nation actively conducting live nuclear tests at the time.87 This program gained the support of many scientists, and while met with initial skepticism by Soviet leadership, the USSR would soften this stance and begin to negotiate and participate on the peaceful use of nuclear energy. In the 1960s and onward, multiple peace-oriented and antinuclear weapons groups, movements, and programs gained influence across the world. This in turn inspired many nations that could invest in nuclear weapons to defer and seek alternatives.

While nuclear weapons development is not a perfect match to how advanced AI development (including autonomous weaponization initiatives) may progress, such a resistance and activist movement could perhaps deter or contain the general AI development that could lead to a singleton entity or postpone a dangerous singleton arms race toward accomplishing the first one over adversaries.88 Unlike nuclear weapons that are a means toward particular ends in foreign policy and defense, the singleton as well as any singularity that produces transhuman entities with superintelligent abilities may quickly become their own ends in themselves. In such stark possibilities, a neo-Luddism movement, assuming one or more exist during the development of such AI and human enhancement, likely will be entrenched to form some resistance. Even if resistance occurred, the disadvantages of that group would be exacerbated by an assumed takeover of national security apparatuses by a superintelligent transhuman entity or AI singleton at the request or unwitting agreement of those designing the technology.

Unlike the English Luddites of the nineteenth century that they are named for, neo-Luddites are a decentralized, leaderless movement of nonaffiliated groups and individuals that propose the rejection of select technology, particularly those that pose tremendous environmental threat and any significant departure from a simplistic, natural state of existence. Neo-Luddites take a similar philosophical stance as antiwar and antinuclear groups, where the elimination of harmful technology offers salvation for humanity as one species within the broader ecosystem of planet Earth. Mathematician and conflict theorist Anatol Rapoport termed such movements “global cataclysmic” where all war is harmful and the prevention of any war is a necessary goal for all of civilization to pursue.89 While Rapoport crafted his concept to frame mid-late Soviet conflict philosophy through this self-preservation of Marxist society, “global cataclysmic” could be applied also to international entities such as the United Nations concerning conflict, and for environmental efforts as a way to explain the radical positions of the ecoterror group Earth Liberation Front in the 1990s in the American Pacific Northwest. Unlike a Westphalian or Clausewitzian war philosophy that permits state-on-state and other state-directed acts of policy and war, the global cataclysmic philosophy rejects all wars as dangerous to society. Neo-Luddites would swap “war” with “dangerous technology” and foresee human extinction or a planet-wide disaster as a direct, foreseeable outcome of human tinkering with technology that could destroy the world as we know it. The term Luddite is also misapplied when some of the most prominent AI developers such as Elon Musk, Bill Gates, Alan Turing, and others are lumped into this group because they call public attention to the concerns of AI and are raising them for entirely different purposes than what neo-Luddites seek.90