PRINTER FRIENDLY PDF

EPUB

AUDIOBOOK

Abstract: Russia’s experience in Ukraine highlights the importance of the human weapon system in next generation warfare. They show that despite technological superiority and investment in sophisticated weapons and equipment, such as hypersonic missiles, people are the core of a successful military strategy. While Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has resulted in kinetic and largely conventional warfare, the human weapon system is essential across the range of military operations, particularly in gray zone operations. There may be no place where the human weapon system is more important; strategic and meaningful management of the human weapon system for use in countering gray zone activities may prevent escalation into kinetic operations.

Keywords: hybrid warfare, gray zone, Russia, China, diversity, inclusion, human weapon system, strategic competition, military operations, Joint force, innovation, national security, personnel, talent, recruitment, retention, strategy, policy, workforce management, employment, armed forces, stereotypes, operational effectiveness, equity

At the onset of the conflict between Russia and Ukraine, Russia was (and one could argue still is) the technologically superior force with more than 4,000 military aircraft, 12,000 tanks, 605 naval vessels, 850,000 active duty troops, antisatellite weapons, the world’s widest inventory of ballistic and cruise missiles, nuclear forces, hypersonic technology, clandestine and proxy forces, and extensive cyber and information warfare operations.1 It had a sophisticated military apparatus, coupled with the power of nuclear deterrence. On paper, the invasion of Ukraine should have been a quick victory for Russia. Their military campaign, however, has been largely unsuccessful, and as of fall 2022, Ukraine has fought back and stunningly recovered territory throughout their country.2

Russia’s experience in Ukraine highlights the importance of the human weapon system in next generation warfare. By human weapon system, the authors are referring to the role that individuals play in operations. This includes how diversity, past lived experiences, and unique backgrounds are utilized. Russia’s experiences show that despite technological superiority and investment in sophisticated weapons and equipment, such as hypersonic missiles, people are the core of a successful military strategy. While Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has resulted in kinetic and largely conventional warfare, the human weapon system is essential across the range of military operations, particularly in gray zone operations. The gray zone refers to those activities that take place between peacetime and war. They may be conceived of as gradualist campaigns and employ nonmilitary and quasimilitary tactics that fall below the threshold of conflict. They may include both state and nonstate actors. There may be no place where the human weapon system is more important; strategic and meaningful management of the human weapon system for use in countering gray zone activities may prevent escalation into kinetic operations.

Indeed, Russia can serve as a case study for how poor management of the human weapon system can undermine technological advancements. Intercepted calls, former Russian officials, and social media accounts show the extent to which Russia’s human weapon system is in poor shape. “I don’t want to be here. I’m not a warrior. I wasn’t even f——g trained, to run away from the tanks, for f——k’s sake,” a disgruntled Russian soldier expressed to his mother over the phone.3 Another soldier described the deficiencies: “There is simply no discipline, and it will only get worse now that they have mobilized 300,000 people who will be barely trained. . . . The army doctrine is based on punishment, so soldiers get penalized if they mess up. . . . Screw-ups will happen until they change the whole philosophy.”4 A former Russian official shares these details about the state of Vladimir Putin’s military forces in the Ukraine war.

As the United States considers next generation warfare, particularly how it is going to shape the force to successfully compete in gray zone operations with Russia and the People’s Republic of China (PRC), management of the human weapon system must be a primary concern. As put forward in the National Security Strategy, outcompeting the PRC and containing Russia are key strategic priorities.5 The National Defense Strategy prioritizes deterring aggression from these countries and being prepared to prevail in armed conflict if necessary.6 There are certainly material solutions to addressing these challenges, including modernized combat systems, tactics, and technologies like long-range precision fires, hypersonic missiles, modernized bomber fleets, littoral combat operations, and other agile mission capabilities.7 Without a clear understanding of how to leverage the human weapon system, all technological, doctrinal, or strategic advancements are ineffective. In Force Design 2030, the Commandant of the Marine Corps further recognizes that while there are structural changes that need to be made, and technological investments (and divestments) to meet the pacing threats, investment in Marines is a linchpin to success in any changes that may occur.8 This people-focused approach is mirrored in all branches of the U.S. military. The Army 2030 initiative asserts that despite the need for technical advancements, people are the key advantage that the U.S. Army has over its adversaries.9 The Chief of Naval Operations’ Navigation Plan 2022 asserts that empowering our people is the key warfighting advantage that the Navy brings to the future fight.10 The chief of staff of the Air Force asserted that “we must empower our incredible airmen to solve any problem” as a key pillar of his Accelerate Change or Lose strategy.11 And the Space Force’s Campaign Support Plan emphasizes the importance that relationships play in the ability of the Service to fulfill its mission and contribute to national security.12 The Services clearly recognize that people play a key role in military operations. Continuing to highlight how people contribute to current and future operational needs will strengthen investment in our people and continue to give the United States a competitive edge.

In this article, the authors lay out the case for why management of the human weapon system must continue to be prioritized as a focus of competition in the gray zone. If the United States is going to succeed in outcompeting our near-peer adversaries, it begins with leveraging our people. The authors begin with a discussion of the human weapon system and its application in the military context, including the importance of human weapon systems management to understand internal military capabilities and the external environment in which a military is operating. The article then discusses how the human weapon system will give the United States an edge in gray zone competition. The authors conclude with a discussion of current challenges to human weapon system management and what the Department of Defense and military Services can do to mitigate them.

What Is the Human Weapon System?

The human weapon system refers to the role that people play in warfighting. While people have always been essential to warfighting, recent decades have seen a deliberate focus on developing the human weapon system and integrating a whole of person approach to optimizing military operational effectiveness. In 2006, the Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences hosted the first conference on “Human Performance Optimization.”13 The conference grew out of the realities on the battlefields of Iraq and Afghanistan. In the early years of the Global War on Terrorism, Special Operations Forces leadership declared that “humans are more important than hardware,” and in 2004 Deputy Secretary of Defense Paul D. Wolfowitz stated that we need to “develop the next generation of . . . programs designed to optimize human performance and maximize fighting strength.”14

Throughout the early and mid- 2000s, the Department of Defense (DOD) and military Services invested in modernizing human performance.15 They developed a capabilities-based model of understanding the performance requirements of the operational environment and revamped training, equipment, and standards to meet new needs.16 Physical performance labs studied the best ways to optimize training to meet the physical demands of military operations. Physical fitness assessments were updated to incorporate both functional movements and provide an overall assessment of individual health and well-being. Nutritionists have been hired to overhaul chow-hall food to ensure that servicemembers are receiving the optimal nutrition to meet physically demanding jobs.17 As technology rapidly advances, there are additional calls to continue to invest in understanding the human-technology interaction regarding human performance.18

While physical performance is one part of the human weapon system, managing the human weapon system is not only about physicality. Mental resilience is just as important as physicality to successful military operations.19 Developing programs that build mental resilience, investing in mental health care, and incorporating a range of practices to promote self-care, unit cohesion, and build trust are ways that mental resilience has been built into the human weapon system.20

Physical performance and mental resilience are aspects of the human weapon system that the military Services can develop within individuals. Fitness and resiliency are largely trainable traits; the Services invest in and customize training for their specific operational needs. Yet, there are untrainable and more intrinsic aspects of the human weapon system that are just as important. Optimizing the human weapon system focuses on ensuring that the United States has the most effective fighting force in the world. It includes both optimizing the physical and mental well-being of U.S. citizens so that they can perform at their best while leveraging the unique backgrounds of individuals to strengthen U.S. national security through employment of diverse skill sets, innovation, and talents.

The nearly two decades of conflict in Iraq and Afghanistan highlighted the importance of how diverse backgrounds were essential for military operations. Lioness teams and Female Engagement Teams were essential for combat operations.21 All-male infantry units, even with extensive training, could not have the same impact as women, who were able to engage in culturally sensitive and appropriate ways. Counterinsurgency, Joint Publication 3-24, codified the need to bring diverse backgrounds to the fight, discussing both the unique role that women play in these types of conflicts and the need for deliberate cultural understanding as part of the way the United States exploits its adversaries.22

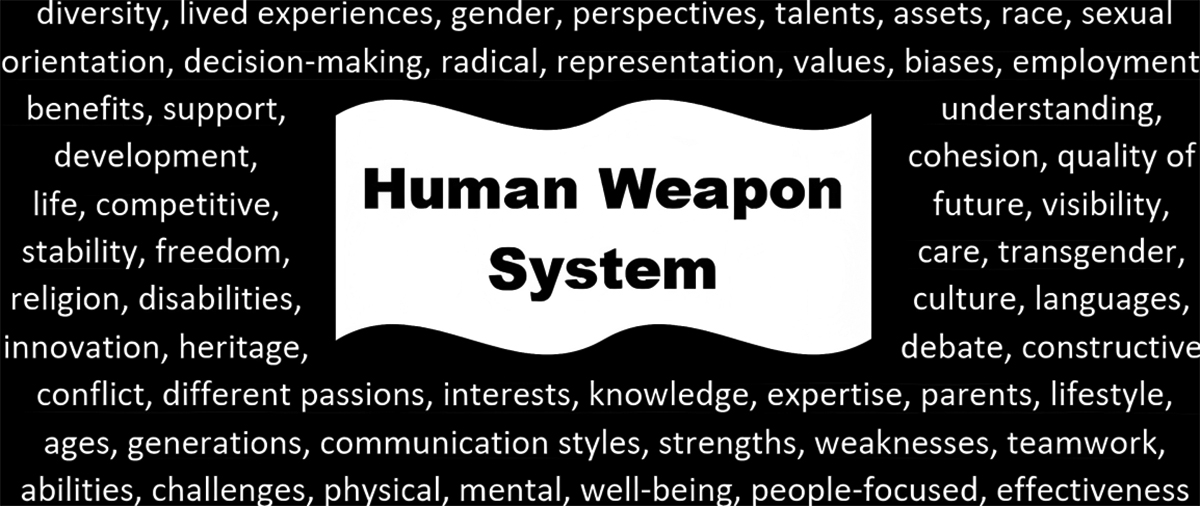

Figure 1. Examples of the various facets of the human weapon system

Source: Bonnie Rushing, 2022, adapted by MCUP.

Counterinsurgency provides a clear and obvious example of how the unique backgrounds of servicemembers can contribute to military operations. Now, the United States pivots to focus on strategic competition where it is just as critical to understand the importance of the human weapon system and leverage the unique and diverse talents of our servicemembers. Though technology continues to evolve and strategic competition is unfolding, the United States’ strength depends on the ability of the DOD to recruit and retain individuals with diverse skills and abilities to take on the country’s toughest security challenges.

Leveraging the diversity of our servicemembers is essential for the United States to be competitive across the range of potential military operations—from competition in the gray zone to kinetic combat operations. This idea is reinforced at the executive level. In a recent memorandum, “Memorandum on Revitalizing America’s Foreign Policy and National Security Workforce, Institutions, and Partnerships,” President Joseph R. Biden notes that diversifying the national security workforce—including the military—is essential for closing mission critical gaps in skills and perspectives.23 The White House’s National Security Strategy (NSS) further emphasizes the need to ensure the well-being of our military servicemembers and also to continue to diversify the force as essential components to achieving the United States’ strategic goals.24 As the United States competes against near-peer threats, diversity and innovation are critical. As the NSS states, the primary means by which our national security objectives will be obtained is by “strengthening the national security workforce by recruiting and retaining diverse, high-caliber talent.”25

The diversity of our workforce is particularly important as our primary adversaries—namely the People’s Republic of China and Russia—are engaging in training and recruiting efforts that narrow the opportunities for independent decision making, innovation, morale, and personnel development.26 Leveraging the human weapon system is thus a strategic asset that is required in today’s rapidly changing security environment.

Diversity is critical while considering all potential courses of action. Instead of operating in an echo chamber where a leader surrounds themselves with only like-minded team members that may simply agree on everything or generate similar ideas, diverse teams generate higher levels of innovation, creatively solving problems with higher success rates. Research shows that teams that are diverse consider more facts before deciding and are more likely to accurately interpret facts than homogeneous teams.27 Diverse teams also create more technologically innovative solutions and are more likely to come up with “radical” solutions that solve the root cause of problems.28

Proper management of the human weapon system has an internally and externally reinforcing function. Strategic leaders must understand the needs of their airmen, guardians, soldiers, Marines, and sailors (the internal aspect of the human terrain) while also understanding the ever-changing sociocultural environment (external) in which they operate. The Department of Defense’s Women, Peace, and Security Strategic Framework and Implementation Plan captures aspects of the reinforcing mechanisms between the internal and external aspects of the human terrain.29 The ordering of the three defense objectives provides a roadmap for how understanding the human weapon system can help the United States succeed in strategic competition.

Defense Objective 1. The Department of Defense exemplifies a diverse organization that allows for women’s meaningful participation across the development, management, and employment of the Joint Force.

Defense Objective 2. Women in partner nations meaningfully participate and serve at all ranks and in all occupations in defense and security sectors.

Defense Objective 3. Partner nation defense and security sectors ensure women and girls are safe and secure and that their human rights are protected, especially during conflict and crisis.

Defense objective 1 is the internal aspect of human terrain. As will be discussed below, it includes understanding how to create policies and pathways that allow for all to meaningfully participate in the institution. From defense objective 1 flows defense objective 2. Success in strategic competition hinges on the United States being a leader in the protection of democracy, human rights, and empowerment. To be an international partner of choice, the United States must model these actions internally. Objective 2 cannot be fully achieved without meaningful investment in objective 1. Finally, defense objective 3 is aimed at creating a more just and secure world. The protection and treatment of women is directly related to the security of states.30 As the article will show, the ability to have a meaningfully diverse force (objective 1) and build allies and partners around a shared sense of purpose (objective 2) will lead to a more holistic and meaningful understanding of the operational environment, including ensuring that women and girls are protected and empowered during crises.

The Human Weapon System in Gray Zone Competition with the PRC and Russia

The PRC and Russia currently challenge U.S. national security with advanced technology, weapons development, and ceaseless gray zone warfare tactics. Regardless of the ever-changing battlefield and technology environment, the human weapon system remains crucial for operational success, including effectively countering adversarial gray zone threats. Through proactive and positive management of the human weapon system, the United States can succeed in competition and potentially prevent gray zone competition from escalating into kinetic operations.

The National Defense Strategy defines these operations as “coercive approaches that may fall below perceived thresholds for U.S. military action and across areas of responsibility of different parts of the U.S. Government.”31 It calls out both the PRC and Russia (as well as other adversaries) for employing gray zone tactics as part of their overall strategies and asserts that campaigning in the gray zone must be a key part of the Joint force’s capability in the future threat environment.

The PRC views gray zone activities as a natural extension of how countries exercise power and uses it to build favorable geopolitical conditions without triggering major backlash.32 The People’s Republic of China particularly focused on using gray zone tactics against our allies and partners in the U.S. Indo-Pacific Command area of responsibility, targeting Japan, Vietnam, Taiwan, the Philippines, and India. Russia sees gray zone activities as a way to compete with the United States—and the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) more broadly—in unconventional ways that go predominantly uncontested because they fall below the threshold of what typically elicits a military response.33 Russia may also be using gray zone activities to actively shape their near environment to be more favorable for follow-on kinetic military operations (such as the invasion of Ukraine).34

Gray zone operations are difficult to counter because they are “gradualist campaigns,” combining a mix of traditional military activities with both nonmilitary state and nonstate actors.35

Table 1. Examples of gray zone activities

|

Tactic

|

Examples

|

|

Information operations

|

Disinformation campaigns in the media

Censorship of dissenting or antigovernment messages

|

|

Political coercion/disruption

|

Blocking of NATO expansion into Balkans Belt and Road Initiative

|

|

Economic coercion/disruption

|

Use of military vessels to intimidate or harass commercial shipping

Market dominance (i.e., Russia’s liquified natural gas energy market dominance)

|

|

Disruption of space operations

|

Jamming and spoofing of satellites

Testing offensive space weapons by the PRC and Russia

|

|

Proxy forces/paramilitary

|

Funding of “little green men” by Russia

China’s use of commercial fishing vessels to challenge international water access

Establishing dual-use bases or ports in contested areas

|

|

Military basing in disputed territories

|

Forward deployed troops or equipment in contested areas

Creation of artificial military bases in disputed sea territory

Conducting exercises in contested areas

|

|

Cyber operations

|

Breaches of election security systems

Hacking into financial systems

|

Source: courtesy of the authors.

As seen in table 1, gray zone operations include a wide range of activities. Military responses to these activities must walk a fine line. Conventional military responses can escalate gray zone activities and draw unwanted international attention, yet the military participates in responding to gray zone activities, and, in many ways, are the key actors responsible for ensuring that activities do not escalate.

The human weapon system is a key component of the military capability to appropriately respond to gray zone activities. Diversity in experiences and backgrounds is essential to countering mis- and disinformation. Diverse understanding of the cues and codes contained in images and language are essential for differentiating real from fake information and for providing important social context as to why certain populations are the targets of falsehoods.36

Members of the military are specifically targeted by mis- and disinformation campaigns.37 A more diverse force will help inoculate servicemembers from falling for this gray zone tactic both through a greater collective understanding of what mis- and disinformation is and through creating more creative solutions to countering fake information.38 These strategies can also be used to counter mis- and disinformation that appear more broadly in society.

A diverse force also offers our allies and partners a counter to China and Russia’s authoritarian politics. China’s Belt and Road Initiative not only brings economic impact to countries, but it also imposes China’s narrow political and social norms to trading partners. These include anti-LGBTQ policies, a male-sex preference in children, and single-party rule.39 Authoritarian regimes—or even authoritarian leaning factions among democracies—center many of their policies around misogyny.40 As a result, women and girls have been central in countering authoritarian regimes.41 The political and economic coercion by the PRC and Russia seek to undermine or destabilize democracy. As the United States engages with allies, partners, and potential partners around the world, it has an opportunity to model an alternative to these authoritarian policies. By embodying a diverse and cohesive force, the United States can counter efforts by China and Russia to deny diversity in society. The DOD’s implementation guidance to the Women, Peace, and Security Act of 2017 recognizes the importance of promoting diversity with our allies and partners. Meaningful management of the human weapon system will ensure the United States does.42

Additionally, proper management of a diverse human weapon system will help ensure that economic investments are meaningful and less prone to corruption. While the military is not the primary arm of economic investment, it works closely with organizations like the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) and other private entities to ensure overall security and stability. When women are involved in economic aid, the outcome results in more security and stability in the place where the aid was distributed.43 Similarly, when national economic growth is coupled with strategies that help women—such as access to child care, equality in education, and equitable health care benefits, women are able to take better advantage of such opportunities and the whole of society is strengthened.44 A diverse military will help to see where risks to an equitable distribution of economic opportunity may be, as well as key opportunities.

Finally, a diverse force is essential for countering military posturing—including adversarial basing and exercises. Much of the posturing done by our adversaries’ militaries is done to elicit a response from the United States as a means of escalating activity. Yet, rather than countering with direct military action, strategic engagement in military exercises can counter the impact of our adversaries in the region. For example, the U.S.-Australia joint exercise Talisman Saber both had the countries engaging with a near-peer competitor and worked to promote gender equality in vulnerable countries in the region.45 The Joint exercises Viking 18 and Viking 22 integrated gendered components to planning high-north exercises, and the result was an ability to counter Russia’s narrative about hard security outcomes.46

While the military alone is not responsible for responding to gray zone activities, it plays a significant role. U.S. forces are forward deployed throughout the world, at permanent bases, temporary assignments, and as part of force projection and quick response packages. As such, they are often the first to respond to a crisis. Additionally, forward deployment serves as a soft-power cultural exchange with allies and partners, which gives them key insights into the risks posed by gray zone activities.

Diversity Directives and Personnel Policies

To effectively manage the human weapon system through the recruitment and retention of a diverse force, the DOD and the Services publish directives and policies related to diversity, equity, and inclusion. Furthermore, Service branch leaders update and implement policies related to diversity initiatives to expand servicemember lifestyle options, quality of life, more inclusive dress and appearance, increased awareness and combat of biases, and care for victims of harassment and assault.

Directives on diversity at the federal level include: Executive Order 13583, Establishing a Coordinated Government-wide Initiative to Promote Diversity and Inclusion in the Federal Workforce; the Women, Peace, and Security Act of 2017; and the Department of Defense DEI Military Equal Opportunity Program.47 Collectively, these directives aim to advance equity, inclusion, civil rights, racial and gender rights, and equal opportunity at the highest levels of the country’s national security infrastructure. They cultivate diverse and dignified workforces, international security, peace, development and afford equitable opportunities in safe environments, free from prohibited discrimination, retaliation, and harassment.

At the Service levels, there are branch-specific policies and regulations related to diversity that mirror much of the federal-level guidance. Each Service branch of the military has similar regulations and goals: Diversity and Inclusion, Air Force Instruction 36-7001; the Army’s Army People Strategy: Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion Annex; the Navy’s “Diversity, Equity & Inclusion” objectives; and the Marine Corps’ Talent Management 2030.48 These directives tailor national guidance to Service-specific objectives.

They are intended to guide the Services’ recruitment and workforce management to attract, recruit, develop, and retain high quality, diverse personnel, with a culture of inclusion to leverage America’s talent pool and power of diversity for strategic advantages in the Joint force. This includes diversity of demographics (personal characteristics, age, race/ethnicity, religion, gender, socioeconomic status, family status, disability, sexuality, gender identity, and geographic origin), cognitive and behavioral diversity (neurodivergent individuals, differences in styles of work, thinking, learning, and personality), organizational and structural diversity (institutional background characteristics and experience), and global diversity (knowledge of and experience with foreign languages and cultures, inclusive of both citizens and noncitizens).49 Services similarly describe diversity as a critical way to enhance decision making, creativity, and the competitive edge to optimize operational effectiveness.50

There are additional policies that enable diversity in the military, including freedom of religion, sexual assault prevention and response (known as SAPR, including mandatory annual training to help shape healthy and safe climate and culture, victim care, and support) the repeal of the “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” policy against nonheterosexual servicemembers, and updated guidance welcoming transgender military personnel to serve openly.

Support policies can also indirectly increase diversity. For example, parental leave policies have expanded to include both caregivers, regardless of gender, lengthened in duration, and the inclusion same-sex couples and adoptions. Support is also provided for miscarriages and other fertility-related concerns. Pregnant personnel may continue to fly actively if they desire. New mothers also have a longer recovery time available prior to an official fitness test requirement.51

Dress and appearance regulations have been updated to include more hairstyles, such as ponytails, increased bun and bangs size, more options for women to wear trousers, jewelry, cell phone use, hands in pockets, and more. These changes consider different hair types, comfort, and quality of life while still upholding good order, discipline, and military effectiveness.52

Within different Services, physical fitness standards and programs are being updated to both reflect changes in the demographics of the force and the changing nature of military requirements. While not diversity policies directly, they recognize that outdated physical fitness norms may harm servicemembers.53 In the Air Force, the physical fitness test is now including alternative event choices, the ability to take a “diagnostic” physical fitness test and choose to save it as official afterward, special considerations for certain career fields where higher standards are required, and updated accounting for gender, age, climate acclimation, injuries, and test location altitude.54 The Marine Corps is updating its body composition standards, allowing for higher weights and body fat percentages to reflect the strength and body mass requirements of women in newly opened career fields.55

There are also efforts to improve diversity and remove potential bias from promotion and special assignment positions. Service directives have worked to eliminate references to race, gender, parental status, or religion from all promotion, award, and special assignment boards.56 While the intent is to remove conscious and unconscious biases that may be inhibiting diversity, it is a large undertaking to remove all identifying markers. In briefings about the updated process, the Services acknowledge that scrubbing records of all identifying information is not yet complete and identifying information is still a part of some records.57

The policy commitment to diversity is essential in setting top-down focus on human weapon system management. Yet, personnel-focused policy alone will not ensure U.S. success in gray zone competition. There are ongoing challenges to fully managing the human weapon system that must be addressed.

Challenges to Human Weapon System Management and Employment: Recruitment and Retention

While the United States is currently more successful than the PRC and Russia in managing the human weapon system, it still faces significant challenges, particularly with recruitment and retention of diverse servicemembers and national security professionals. The United States needs a qualified and diverse talent pool to counter adversary gray zone operations and to harness servicemember expertise and innovation for the next generation of warfare. This diversity is what sets America apart from its adversaries: “Indeed, pluralism, inclusion, and diversity are a source of national strength in a rapidly changing world.”58

The all-volunteer force presents challenges, in that diverse individuals must self-select into Service. Propensity to serve in the military for all young people continues to decline, and in fiscal year 2022 the Army missed its recruiting goal by approximately 15,000 soldiers, and while other Services met their goals, they had to rely on unplanned bonuses and financial incentives or changes to recruiting targets.59

Some demographics do not join or remain in the armed forces as often, for example, “military service still skews heavily towards men (4 out of 5 active duty enlistees are male)” and there is an overrepresentation of the Black American population in the military—specifically, about twice as many Black men serve in the U.S. military as their White male counterparts, numerically.60 This “can be seen as a double-edged sword. On the one hand, the military has served as an important means of economic mobility for many Black men. On the other hand, the dominance of Black Americans in military service—and therefore among these most likely to be put in harm’s way on behalf of the nation—is striking, especially in light of broader current conversations about race, justice and equity.”61

It is important for the military to represent the people it serves, and that starts at recruiting stations where there must be visibility on diverse personnel in the office, on the materials, and seen in marketing campaigns. Recruiters must enhance their current approaches by following social trends of America’s teenage population.62 Growing youth propensity to serve also requires engaging with youth in the means they are the most comfortable, including popular social media platforms, other information networks, and in trending applications.63 Distributing correct facts, debunking military stereotypes and myths, and wholly representing the talent pool is crucial for attracting talent of all demographics. Women and their families, for example, fear possible sexual assault in the military and may not join for this reason.64 Effective delivery of inclusive practices, accurate narratives, and employment of inclusion-focused recruiting not only builds diversity in our ranks, but it also builds trust with the American people and taxpayers who feel wholly represented by troops of every background.

In addition to recruiting diverse and effective talent, retaining talent is a challenge for the U.S. military. The Department of Defense Diversity, Equity, Inclusion, and Accessibility Strategic Plan: Fiscal Years 2022–2023 prioritizes objectives for career progression and retention. There must be opportunities for all demographics to be promoted and serve in key positions and gain career-enhancing education with selection transparency. Additionally, the roadmap prioritizes mentorship for underrepresented groups and elimination of work environment and policy barriers that inhibit equitable practices.65 Leaders must ensure all members have fair opportunities to develop and succeed. Furthermore, structural concerns may disproportionately impact certain demographics. Women are almost one-third more likely to leave the Service at any time than their male counterparts. Family concerns, including access to adequate and affordable housing, stability for children, family planning support, reliable and affordable childcare, and other quality of life factors are cited as top reasons women leave the Services.66 These issues are “inextricably linked” to military readiness.67 Addressing and rectifying these problems must be a priority to retain talented personnel.

The National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2023 (NDAA) addresses some of these issues. The Services and the Department of Defense are hiring more than 2,000 prevention professionals, aimed at changing the culture around sexual harassment and assault and other adverse behaviors that harm recruitment and retention efforts.68 The NDAA also called for studies to examine compensation models, barriers to home ownership, and promotion pathways for servicemembers.69 Other recent DOD actions may also address barriers. A recent memorandum on family planning by the secretary of defense seeks to address both privacy and access to care concerns that arose out of the Dobbs vs. Jackson Women’s Health Organization (2022) that overturned the provision of a constitutional right to an abortion.70 While it is too soon to determine the impact of these changes, they show an understanding of the requirement to meet the needs of servicemembers to recruit and retain a diverse force.

Challenges to Human Weapon System Management and Employment: Ties to Operational Effectiveness

Recruitment and retention are not the only challenges that the United States faces regarding the human weapon system. Most of the directives discussed are focused on personnel systems and policies. However, for the Services to fully embrace an action, there must be direct ties to operational effectiveness. The Independent Review Commission on Sexual Assault in the Military found that while personnel issues are frequently talked about as “readiness issues,” they are not measured or tracked as such, allowing them to become afterthoughts in the minds of operationally minded military leaders.71

Making the direct connections between personnel actions and operational effectiveness is a missing link for the effective management and employment of the human weapon system. Arguments about the “wokeness” of the military highlight that the operational link between a diverse force and operational necessity is not yet fully understood.72 To fully engage across gray zone activities, the Services need to incorporate the importance of diversity in their doctrine, planning, and professional military education processes.73

These actions have proven tactically, operationally, and strategically effective. Gender advisors and gender focal points at the combatant commands have strengthened the United States’ strategic partnerships in key contested regions and improved stability and security during humanitarian and disaster response operations.74 Additionally, they have proven successful in strengthening ties between the DOD and other government agencies, such as the Department of State and USAID.75 This whole-of-government approach is necessary for gray zone competition.

Building off the success of combatant commands, the DOD and military Services would benefit from standardizing aspects of the gender advisor workforce and integrating diverse perspectives throughout the operational planning process. Revising the planning process to consider all perspectives will signal to the force that addressing diversity initiatives is essential and leads to an inclusive culture where the safety and well-being of all members is seen as an essential part of security and military operations.76

Conclusion

Success in gray zone operations requires thoughtful management of the human weapon system. To do this, the United States must also leverage the diverse talents of its force and fully integrate diverse perspectives into operational planning and readiness. As our near-peer competitors are becoming increasingly narrow in their view of security, there is an opportunity to leverage diverse perspectives and be successful before competition escalates to conflict. While the United States has enacted various diversity initiatives in the past several years, the importance of personnel cannot be eclipsed by investments in technology. As the United States shifts focus on a new pacing threat, the human weapon system remains the linchpin of our success.

Endnotes

- “Global Firepower 2023,” Global Firepower, accessed 29 December 2022; Deganit Paikowsky, “Why Russia Tested Its Anti-Satellite Weapon,” Foreign Policy, 26 December 2021; and Ian Williams, “Missiles of Russia,” Missile Threat, 10 August 2021.

- Gian Gentile, Raphael S. Cohen, and Dara Massicot, “Ukraine’s 1777 Moment,” Rand (blog), 19 September 2022.

- Gerrard Kaonga, “Furious Russian Soldier Complains to Mom after Fleeing Ukrainian Offensive,” Newsweek, 25 November 2022.

- Daniel Boffey and Pjotr Sauer, “ ‘We Were Allowed to be Slaughtered’: Calls by Russian Forces Intercepted,” Guardian, 20 December 2022.

- National Security Strategy (Washington, DC: White House, 2022).

- 2022 National Defense Strategy of the United States of America (Washington, DC: Department of Defense, 2022).

- Andrew Feickert, U.S. Army Long-Range Precision Fires: Background and Issues for Congress (Washington, DC: Congressional Research Service, 2021); “B-21 Raider Makes Public Debut: Will Become Backbone of the Air Force’s Bomber Fleet,” U.S. Air Force, 2 December 2022; and “Littoral Combat Regiment,” Marines.mil, 2 August 2021.

- Gen David H. Berger, Force Design 2030 (Washington, DC: Headquarters Marine Corps, 2020).

- “Army of 2030,” Army.mil, 5 October 2022.

- Chief of Naval Operations Navigation Plan 2022 (Washington, DC: U.S. Navy, 2022).

- Gen Charles Q. Brown Jr., Accelerate Change or Lose (Washington, DC: U.S. Air Force, 2020).

- “2021 USSF Campaign Support Plan,” Spaceforce.mil, 6 December 2021.

- Patricia A. Deuster et al., “Human Performance Optimization: An Evolving Charge to the Department of Defense,” Military Medicine 172, no. 11 (November 2007): 1133–37, https://doi.org/10.7205/MILMED.172.11.1133.

- A. P. Tvaryana et al., “Managing the Human Weapon System: A Vision for an Air Force Human-Performance Doctrine,” Air & Space Power Journal 23, no. 2 (2009).

- “Human Performance,” AFRL, accessed 8 May 2023.

- Tvaryana et al., “Managing the Human Weapon System,” 34–41.

- Gina Harkins, “The Military is Overhauling Troops’ Chow as Obesity Rates Soar,” Military Times, 19 August 2018.

- Daniel C. Billing, “The Implications of Emerging Technology on Military Human Performance Research Priorities,” Journal of Science and Medicine in Sport 24, no. 10 (2021): 947–53, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsams.2020.10.007.

- Jill R. Scheckel, “Preparing the Human Weapon System: Promoting Warrior Resiliency” (research paper, Air War College, Air University, 2010.

- “Integrated Resilience,” U.S. Air Force, 31 December 2022.

- Ginger E. Beals, “Women Marines in Counterinsurgency Operations: Lioness and Female Engagement Teams” (master’s thesis, Marine Corps Command and Staff College, Marine Corps University, Quantico, VA, 2010).

- Counterinsurgency, Joint Publication 3-24 (Washington, DC: Department of Defense, 25 April 2018).

- “Memorandum on Revitalizing America’s Foreign Policy and National Security Workforce, Institutions, and Partnerships,” White House, 4 February 2021.

- National Security Strategy (Washington, DC: White House, 2022).

- National Security Strategy.

- Eric Danko, “Officer and Enlisted Quality Comparison in the U.S. and the PLA,” WildBlue Yonder, 13 May 2022.

- Katherine W. Phillips, Katie A Liljenquist, and Margaret A. Neale, “Is the Pain Worth the Gain?: The Advantages and Liabilities of Agreeing with Socially Distinct Newcomers,” Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin 35, no. 3, 336–50, https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167208328062; and Sheen S. Levine, “Ethnic Diversity Deflates Price Bubbles,” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 111, no. 52 (2014): 18,524–29, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1407301111.

- Cristina Díaz-García, Angela González-Moreno, and Francisco Jose Sáez-Martínez, “Gender Diversity within R&D Teams: Its Impact on Radicalness of Innovation,” Innovation 15, no. 2 (2013): 149–60.

- Women, Peace, and Security Strategic Framework and Implementation Plan (Washington, DC: Department of Defense, 2020).

- Valerie M. Hudson et al., Sex and World Peace (New York: Columbia University Press, 2012).

- National Defense Strategy, 6.

- Bonny Lin et al., Competition in the Gray Zone: Countering China’s Coercion Against U.S. Allies and Partners in the Indo-Pacific (Santa Monica, CA: Rand, 2022), https://doi.org/10.7249/RRA594-1.

- Anthony H. Cordesman and Grace Hwang, Chronology of Possible Russian Gray Area and Hybrid Warfare Operations (Washington, DC: Center for Strategic and International Studies, 2020).

- “Today’s Wars Are Fought in the Gray Zone: Here Is Everything You Need to Know About It,” Atlantic Council, updated 23 February 2022.

- Cordesman and Hwong, Chronology of Possible Russian Gray Area and Hybrid Warfare Operations.

- Peng Qi et al., “Improving Fake News Detection by Using an Entity-Enhanced Framework to Fuse Diverse Multimodal Clues,” in MM ‘21: Proceedings of the 29th ACM International Conference on Multimedia (New York: Association for Computing Machinery, 2021).

- Peter W. Singer and Eric B. Johnson, “The Need to Inoculate Military Servicemembers Against Information Threats: The Case for Digital Literacy Training for the Force,” War on the Rocks, 1 February 2021; and Kristofer Goldsmith, An Investigation into Foreign Entities Who Are Targeting Troops and Veterans Online (Culpeper, VA: Vietnam Veterans of America, 2019).

- Sonner Kehrt, “Troops, Veterans Are Targets in the Disinformation War Even If They Don’t Know It Yet,” Warhorse, 1 September 2022.

- Min Ye, “Fragmented Motives and Policies: The Belt and Road Initiative in China,” Journal of East Asian Studies 21, no. 2 (2021): 193–217, https://doi.org/ 10.1017/jea.2021.15.

- Nitasha Kaul, “The Misogyny of Authoritarians in Contemporary Democracies,” International Studies Review 23, no. 4 (December 2021): 1619–45, https://doi.org/10.1093/isr/viab028.

- Kathleen McInnis, Benjamin Jensen, and Jaron Wharton, “Why Dictators Are Afraid of Girls: Rethinking Gender and National Security,” War on the Rocks, 7 November 2022; and Erica Chenoweth and Zoe Marks “Revenge of the Patriarchs: Why Autocrats Fear Women,” Foreign Affairs, March/April 2022.

- Women, Peace, and Security Strategic Framework and Implementation Plan.

- Andrew Beath, Fotini Christia, and Ruben Enikolopov, “Empowering Women through Development Aid: Evidence from a Field Experiment in Afghanistan,” American Political Science Review 107, no. 3 (2013): 540–57.

- Mayra Buvinić and Rebecca Furst-Nichols, “Promoting Women’s Economic Empowerment: What Works?,” World Bank Research Observer 31, no. 1 (2016): 59–101.

- Stéfanie von Hlatky and Andréanne Lacoursière, Why Gender Matters in the Military and for Its Operations (Montreal: Centre for International and Defence Policy, 2019).

- Lisa Sharland and Genevieve Feely, eds., “Women, Peace and Security: Defending Progress and Responding to Emerging Challenges,” Strategic Insights ASPI, June 2019.

- “FACT SHEET: U.S. Government Women Peace and Security Report to Congress,” statement, White House, 18 July 2022.

- Diversity and Inclusion, Air Force Instruction 36-7001 (Washington, DC: U.S. Air Force); Army People Strategy: Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion Annex (Washington, DC: U.S. Army, 2020); “Diversity, Equity & Inclusion,” U.S. Navy, updated 3 April 2023; and Talent Management 2030 (Washington, DC: Headquarters Marine Corps, 2021).

- Diversity and Inclusion.

- “Diversity, Equity & Inclusion.”

- “Military Parental Leave Program (MPLP),” U.S. Army, accessed 8 May 2023.

- “Department of the Air Force Guidance Memorandum to DAFI 36-2903, Dress and Personal Appearance of United States Air Force and United States Space Force,” memorandum, U.S. Air Force, 31 March 2023.

- Jeannette Gaudry Haynie et al., Impacts of Marine Corps Body Composition and Military Appearance Program (BCMAP) Standards on Individual Outcomes and Talent Management (Santa Monica, CA: Rand, 2022), https://doi.org/10.7249/RRA1189-1; and “Physical Fitness,” in Defense Advisory Committee on Women in the Services: 2019 Annual Report (Washington, DC: Department of Defense, 2019).

- Department of the Air Force Physical Fitness Program, Department of the Air Force Manual 36-2905 (Washington, DC: Department of the Air Force, 2022).

- “Marine Corps Study on Body Composition Leads to Change,” Marines.mil, 22 August 2022.

- Lolita Baldor, “Esper Order Aims to Expand Diversity, Skirts Major Decisions,” Washington Post, 15 July 2020.

- DACOWITS December 2022 briefing.

- National Security Strategy.

- “Fall 2021 Propensity Update,” Office of People Analytics, 9 August 2022; and Hearing to Receive Testimony on the Status of Recruiting and Retention Efforts Across the Department of Defense, 118th Cong. (21 September 2022).

- Isabel V. Sawhill and Larry Checco, “Black Americans Are Much More Likely to Serve the Nation, in Military and Civilian Roles,” Brookings Institution, 27 August 2020.

- Sawhill and Checco, “Black Americans Are Much More Likely to Serve the Nation, in Military and Civilian Roles.”

- Douglas Yeung et al., Recruiting Policies and Practices for Women in the Military: Views from the Field (Santa Monica, CA: Rand, 2017), https://doi.org/10.7249/RR1538.

- Yeung et al., Recruiting Policies and Practices for Women in the Military.

- Yeung et al., Recruiting Policies and Practices for Women in the Military.

- Department of Defense Diversity, Equity, Inclusion, and Accessibility Strategic Plan: Fiscal Years 2022–2023 (Washington, DC: Office for Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion, Department of Defense, 2022).

- Female Active-Duty Personnel: Guidance and Plans Needed for Recruitment and Retention Efforts (Washington, DC: Government Accountability Office, 2020).

- “CMSAF Wright Testifies before Congress on Air Force Quality of Life,” news, Joint Base San Antonio, 12 February 2019.

- “DOD Begins Hiring Prevention Workforce,” DOD News, 30 November 2022.

- Providing for the Concurrence by the House in the Senate Amendment to H. Res. 7776, 117th Cong. (2022).

- “Ensuring Access to Reproductive Healthcare,” Department of Defense, 20 October 2022; and Kyleanne M. Hunter et al., How the Dobbs Decision Could Affect U.S. National Security (Santa Monica, CA: Rand, 2022), https://doi.org/10.7249/PEA2227-1.

- Hard Truths and the Duty to Change (Washington, DC: Independent Review Commission on Military Sexual Assault, 2021).

- Thomas Spoer, “The Rise of Wokeness in the Military,” Heritage Foundation, 9 September 2022.

- Hard Truths and the Duty to Change. See recommendation 3.4.

- Jim Garamone, “Women, Security, Peace Initiative Militarily Effective,” DOD News, 5 November 2020.

- “Gender Advisors Key to Effective Policy,” Council on Foreign Relations, 14 September 2020.

- Hard Truths and the Duty to Change, recommendation 3.4.