Tommy Jamison, PhD

https://doi.org/10.21140/mcuj.20221302004

PRINTER FRIENDLY PDF

EPUB

AUDIOBOOK

Abstract: The War of the Pacific (1879–84) showcases the development of amphibious warfare during a period of industrialization and technological flux. Historians have traditionally framed Chilean victory in the war as a function of seapower: naval superiority from which victory on land followed as a result. This view underestimates the complex and reciprocal interplay of amphibious and naval operations throughout the conflict. The war can be better understood as a campaign of port hopping, enabled by maritime capacity and naval power, but reliant on amphibious elements to achieve political results and sustain Chilean sea control. In exploring the relationship(s) between amphibious and naval operations in the War of the Pacific, this article historicizes the emergence of modern amphibious warfare as a component of seapower in the industrial era.

Keywords: amphibious warfare, War of the Pacific, technology, nineteenth century

The War of the Pacific (1879–84) is one of many milestones in global military history too often lost in the no-man’s-land between the U.S. Civil War and World War I.1 Fought over the territorial frontiers of Chile, Bolivia, and Peru, it remade the political geography of South America. From a historical perspective, it also offers a valuable data point in the evolution of modern industrial warfare. Using then state-of-the-art technologies, Chile defeated the Andean allies, Peru and Bolivia, at sea in the opening months of the war. After a series of amphibious landings up the Peruvian coast in 1880, the Chilean army occupied the capital, Lima, Peru, in January 1881. Punitive peace treaties signed thereafter ceded a belt of nitrate-rich Peruvian and Bolivian territory to Santiago—including Bolivia’s only seaport, Antofagasta. Irredentist grievances bubbled up in the twentieth century, making the Peruvian-Bolivian-Chilean frontier what the U.S. State Department in 1919 called “America’s Alsace-Lorraine.”2

Alongside political frontiers, the war smashed technological boundaries as well. It featured a burst of developing industrial weapons: the machine gun, armored warships, electrically detonated mines, and locomotive torpedoes—to name just a few. Experts and amateurs from around the world sifted through technical evidence for insights into the future of industrial war.3 The tactics and strategies best suited new technical advancements were hotly debated. In the absence of evidence from great power wars, the War of the Pacific took on an outsized significance.

Operationally, the War of the Pacific was equally suggestive of a coming era of joint assaults from the sea.4 Because the belligerents’ desert frontiers were largely impassable to armies traveling by foot or hoof, Chile’s success hinged on the movement of thousands of men and animals up the coast by sea, defeating the “tyranny of distance” by securing intermediate waypoints (and with them valuable sites of future resource exploitation).5 This port-hopping campaign took place in four phases during roughly 18 months.6 The first was a purely naval contest with Peru for regional sea control. Chilean naval preponderance (assured after October 1879) then enabled three port hops north toward the Peruvian capital: 1) the invasion of Pisagua and Iquique; 2) the Tacna and Arica Campaign; and finally; 3) the landings against Lima. All the while, Peruvian inventors and officials attempted to interrupt Chilean sea lines of communication (SLOCs) with cruisers, torpedoes, and other subterfuges.7 Taken together, the War of the Pacific speaks to the enduring reciprocity between naval and amphibious operations as well as the challenges of joint cooperation, ship-to-shore troop movements, and the vulnerability of sustainment-by-sea to cheap asymmetric weapons. The upshot: coincident with the advent of industrial war at sea came a campaign of amphibious port hopping that both promoted sea control and translated naval victories into results on land.

The Battlespace: Desert, Sea, and the Imperative of Amphibious Operations

The geography of the Atacama Desert was central to the origins and conduct of the war. The actual desert stretches 966 kilometers along the coast of what is today northern Chile, but it shapes the region more broadly. The discovery of nitrate salts (salitre) in the 1840s—used globally in the production of fertilizer and gunpowder—led to a mining boom. Resource exploitation generated revenue and with it interstate frictions between Peru, Chile, and Bolivia. Eventually, in 1879, disputes about taxation—along with other factors—precipitated the War of the Pacific: what was commonly referred to at the time as the Guerra de Salitre or Ten Cents War in reference to the Atacama’s resources and the taxes levied on them, respectively.8

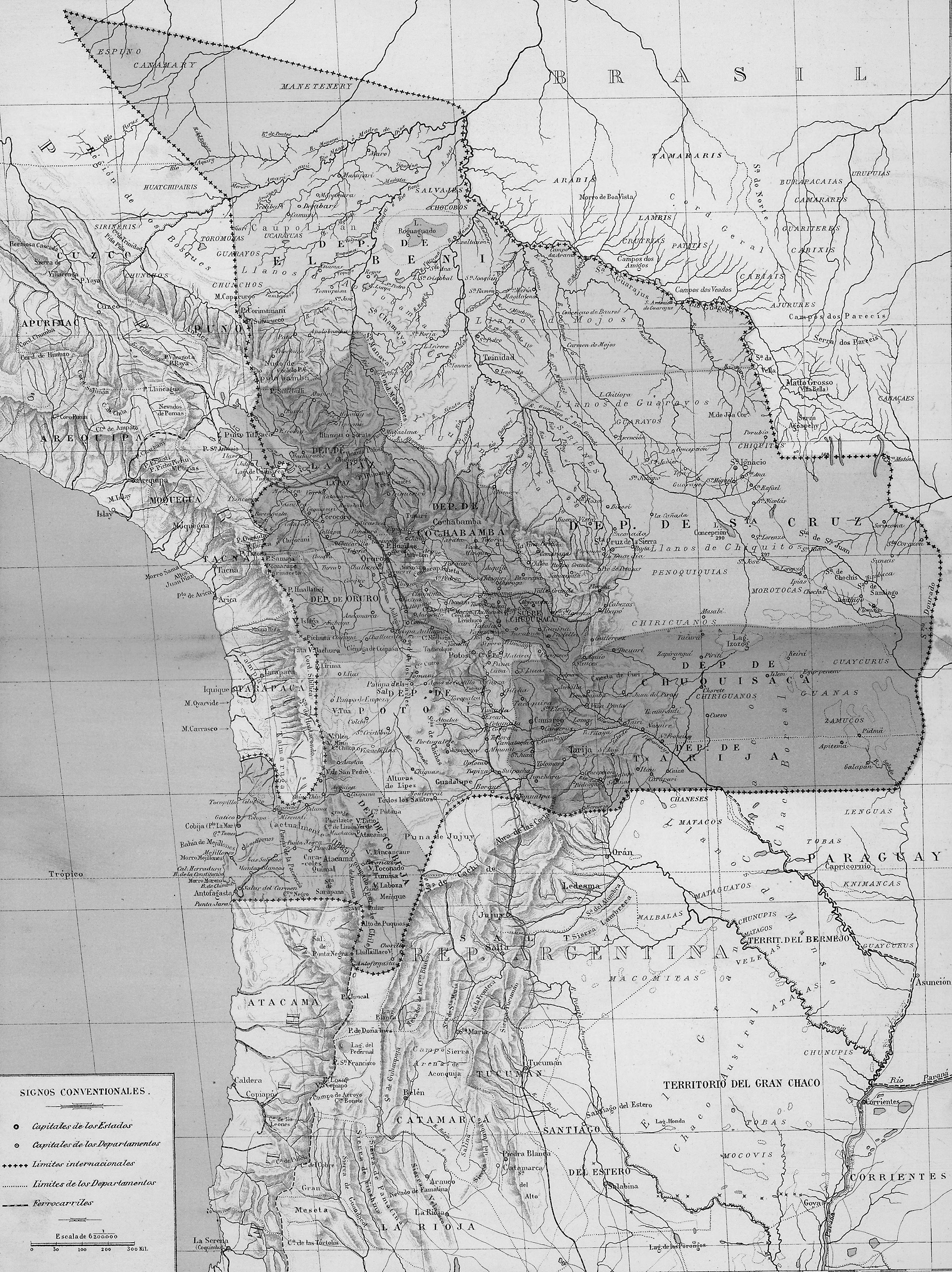

Map 1. Bolivia and the Peru-Bolivia-Chile frontier, 1885

Note: this map shows prewar political boundaries. Both Peru and Bolivia lost coastline in the war to Chile.

Source: Nicolas Estevanez, Bolivia (Paris: Garnier Hermanos, 1885), courtesy of the David Rumsey Historical Map Collection.

But for all its natural wealth, surviving—let alone sustaining major combat operations—in Atacama and the nearby Tarapacá Desert was (and is) a constant challenge. Much of the region is an almost literal Marscape: a surreal expanse where the National Aeronautics and Space Administration tests its rovers and astrobiologists consider the possibilities of extraterrestrial life.9 How to supply and wage an industrial war—complete with thousands of animals—in this space was an open question.10 North-to-south road routes were rudimentary. The handful of existing railroad tracks almost always ran east-west connecting inland mining centers with seaports.11

The difficulty of campaigning across the Atacama made the sea an essential theater of the continental war.12 Divining lessons from the conflict, in 1896, the British historian Herbert Wilson went so far as to assert that because almost all communication along the Pacific slope was carried over water, “whichever power then commanded the sea must inevitably reduce the other to submission.”13 This Mahanian conviction overstated the point, but the war does provide an example of naval power and its advantages for continental campaigns: whether it is the movement of troops and animals, blockades of ports, naval gunfire support, or even the supply of potable water from shipborne condensers.14 Indeed, 10 years before Mahan coined the phrase “sea power,” the inaugural edition of Chile’s Revista de Marina looked back on the war, declaring with serene confidence, “he who controls the sea, dominates the land. . . . The army is a powerful auxiliary . . . but the navy is indispensable.”15

All that said, navalist determinism (often explicit in assessments written by naval officers after the fact) should be viewed with skepticism. Seapower was not and is not a sufficient explanation of Chilean victory in the War of the Pacific. Naval assets could neither dislodge Peruvian garrisons from the provinces of Tacna and Arica, nor force Peruvian leaders in Lima to the negotiating table. Even after achieving command of the sea, the operational challenges of amphibious operations remained dramas of great power and contingency for all involved. Just how and why the Chilean Navy and Army cooperated in the amphibious drive up the Peruvian coast follows below, offering both generalizable lessons about and historical precedents in the evolution of modern amphibious operations.

Phase I: The War for Sea Control as the Precondition of Amphibious Operations

The war’s first phase was a naval one, designed to achieve preponderance at sea, and with it maritime lines of communication around and/or across the desert. In 1911, the British naval theorist Julian S. Corbett noted, “the object of naval warfare must always be directly or indirectly either to secure the command of the sea or to deny the enemy from securing it.”16 Only then could armies and goods move effectively over water. That logic certainly applied to the War of the Pacific.

Ostensibly responding to a tax dispute, in February 1879 Chilean forces occupied Antofagasta—Bolivia’s main port and a key shipping point of the nitrate industry. Peru came to Bolivia’s defense per the terms of the two nations’ defensive alliance. As armies mobilized, both the Peruvian and Chilean fleets—headlined by European-built armored warships—prepared to seek out and destroy the enemy (table 1).

Table 1. Approximate strength of Peruvian and Chilean naval forces, 1879

Naval order of battle of Peru and Chile, ca. 1879

|

|

Chile

|

Notes

|

Peru

|

Notes

|

|

Armored

warships

|

Blanco Encalda, Cochrane

|

2 x 3,500-ton armored frigates

|

Huáscar, Independencia

|

1 x 1,80-ton

turreted monitor; 1 x 2,000-ton armored frigate

|

|

Coastal

defense

|

Torpedo boats

|

11 x 35–70-ton torpedo-boats

|

Atahualpa, Manco Capac;

Torpedo boats

|

2 x 1,000-ton coastal defense monitors; 2 x spar-torpedo boats

|

|

Wooden

cruisers,

corvettes, etc.

|

Abtao, Chacabuco, Covadonga, Esmeralda, Magallanes, O’Higgins, Amazonas, Angamos, Tolten

|

10,000 tons of wooden warships

|

Pilcomayo, Unión, Limeña, Oroya, Chalaco, Talismán, Mayro

|

6,000 tons

of wooden warships

|

|

Total

|

22

|

21,000 tons

|

13

|

12,000 tons

|

Source: Sater, Andean Tragedy, 113–15; La Marina en la Historia de Chile, Tomo I, 438; and Historia Marítima del Perú, Tomo X, 783–84.

The first test of those naval assets came soon enough. In a quixotic attempt to snatch victory through sea power alone, the Chilean admiral Juan Williams Rebolledo deployed the majority of his fleet north to Lima’s contiguous port Callao.17 Modeled on the sort of gunboat diplomacy common in the late-nineteenth century, this effort had the counterproductive effect of opening Chile’s supply lines and depots to raids by the Peruvian fleet. Seizing the opportunity, Peru’s two oceangoing armored warships, the Huáscar (1865) and Independencia (1865), slipped passed the main Chilean force, sailing south unopposed. On 21 May, these ships surprised and engaged the wooden Chilean vessels Esmeralda (1855) and Covadonga (1859) at the small port of Iquique, in what is today northern Chile. Despite a heroic (nigh suicidal) defense by its captain, Arturo Prat, the turreted monitor Huáscar rammed and sank the Chilean corvette Esmeralda.18 Nearby—and less happily for Peru—the ironclad Independencia ran aground in pursuit of the Chilean Covadonga—a catastrophic self-inflicted wound for which the Independencia’s skipper was court-martialed.19

The loss of the Independencia left the Peruvian Navy at a critical disadvantage. Chile now had two seagoing 3,500-ton ironclads at sea against the 1,800-ton Huáscar. That capability gap forced a strategic adjustment. Under the command of Miguel Grau, Peru’s remaining armored combatant, the Huáscar and the wooden corvette Unión (1865), embarked on guerre de course—a war of raids against shipping—as a matter of necessity.20 Complete with radically new technologies like automobile torpedoes, Grau’s attacks might well be seen as a test-in-advance of the principles advocated by the French “young school” in the 1880s (a reaction to asymmetries vis-à-vis Britain).21

Grau’s campaign did not want for drama. The U.S. Navy officer and author James Wilson King reckoned that the “havoc” inflicted by the Huáscar on the Chilean merchant marine gave it “a notoriety second only to that of the [Confederate cruiser] Alabama.”22 King’s was a high, if dubious, compliment. Just as Confederate raiders like the CSS Alabama (1862) had avoided direct conflict with U.S. Navy forces during the Civil War, so too did Grau skirt around the Chilean fleet, preferring instead to raid civil shipping and port infrastructure with sensational effects. Grau racked up a record, seizing, Revista de Marina bitterly recalled, “merchant ships and troop transports, money and important correspondence.”23 Much as the Alabama had for the Union Navy before it, defending against Grau’s raids tied down a disproportionate number of Chilean warships, forcing them to patrol vast expanses of ocean in search of the Huáscar. Grau’s most notable success came with the capture of the Chilean steamer Rimac (1872) on 23 July 1879: a transport carrying cannon and 300 cavalry.24 Defenseless and without enough lifeboats to scuttle the ship, the Rimac’s captain surrendered, though not before the Chilean soldiers reportedly finished off the alcohol onboard.25 Beyond its immediate material effects, the incident dramatized the vulnerability of Chilean sea lines of communication to Peruvian raids. As the contemporary observer Clements Markham noted, as long as Grau “kept his ship on the seas under the Peruvian flag the Chilians [sic] did not dare to undertake any important expedition.”26

Back in Santiago, the loss of the Rimac (or else the failure to impede the Huáscar) was such a scandal that it prompted the removal of Admiral Juan Williams Rebolledo and the appointment of Rafael Sotomayor as minister of war in the field to oversee the military’s efforts.27 Capturing or destroying the Huáscar now became the organizing principle of Chilean naval operations.28 Luckily for Santiago, the Huáscar’s months at sea began to wear on the ship. Fouling (the growth of marine life on the ship’s hull) decreased its top speed—in the end fatally. Sighted on 8 October 1879 and unable to outrun its pursuers, the Chilean ironclads Blanco Encalada (1875) and Cochrane (1875) engaged with and captured the Peruvian Huáscar at the Battle of Angamos, killing Grau in the process.29

The battle marked a pivot in the nature of the war. As was now obvious, Santiago enjoyed, the French legation cabled home, “preponderance over the waters of the Southern Pacific Ocean.”30 That seapower, while impressive, was not an end in and of itself, but rather a means to control communications and safeguard the movement of troops and supplies north to Peru. Rather than a Mahanian triumph for Chile, victory at Angamos only opened a new phase of the war: one of amphibious operations against a still numerically superior adversary alliance. As Sotomayor pondered the situation in October 1879, he came to appreciate that the conclusion of the war as a matter of pure naval strategy came as a prologue for major amphibious operations.

Phase II and III: Chilean Amphibious Operations in the Desert Borderlands

With the threat from the Huáscar eliminated, the Chilean military turned to two missions: the blockade of the enemy coast and the transport of the army north toward the frontier regions and eventually Lima.31 Given the distance, that effort hinged on port hops: the seizure of intermediate waypoints or as the Chilean Revista de Marina described it in 1885, a “step by step, victory by victory” advance “until the triumphant entrance into Lima.”32 Swapping Tokyo for Lima and the “stepping-stone bases which must be seized by amphibious operation” to reach it, makes for a passible description of “island hopping” during WWII.33 Overcoming the distances of the Atacama Desert or the Pacific Ocean would be untenable without supporting bases forcibly taken along the advance. In the same way that in 1921 Marine Corps major Earl H. Ellis contemplated “the reduction and occupation of [islands in Micronesia] and the establishment of the necessary bases therein, as a preliminary phase of hostilities” against Japan, so too did Sotomayor propose hopping up the coast, amphibiously seizing port bases along the way.34 In both cases, the challenge of distance could be met by amphibious operations enabled by and reciprocally supporting naval power. The first of these hops was Antofagasta, seized by Chilean forces in the opening days of the war.35 Where to strike next—how far up the coast to reach and what to risk in doing so—was a hotly contested question.

Phase II: Iquique and Pisagua

There were many possibilities. Pondering various landing sites, Chilean leaders eventually agreed on the mineral-rich Tarapacá province and its port Iquique: a city defended in a manner proportionate to its strategic and economic importance as a center of the nitrate industry.36 Opting to avoid a frontal attack, Sotomayor instead insisted on two landings to the north of the city at Junin Bay and Pisagua (though specific disembarkation plans were not finalized until the invasion force was at sea).37 From there an army of nearly 10,000 troops would linkup and march on Iquique. Faced with an attacking army and invested by the Chilean Navy—the theory went—Iquique’s defenders would have little choice but to evacuate the port.

It was an elegant plan—one leveraging the advantages of maneuver and joint army-navy cooperation—but frictions soon emerged. The first trial in this “Desert Campaign” was simply to amass the necessary transports to move 9,500 troops and nearly 1,000 animals. Naval forces had secured sea control at Angamos, but—as these preparations demonstrated—the ability to use the sea hinged on a broader set of maritime assets: troopships, coaling vessels, and landing craft, often hastily adapted from the commercial purposes that underwrote Chilean economic prosperity in peacetime.38 None were purpose built for amphibious operations, necessitating adaptations on the fly. The bulk of Chile’s navy would escort the nine steam transports earmarked for the invasion; no doubt with the Rimac fiasco in mind.39

This force assembled off of Pisagua on 1 November 1879, where matters got off to a bad start. Due to navigational errors, the fleet rendezvoused at the wrong point and had to steam back toward the assault beaches. Once in position, and already hours behind schedule, the assault confronted a bay defended by two forts and 1,200 dug-in Bolivian troops. Some Chilean officials protested that the landing would be impossible given enemy preparations, rough seas, and narrow beaches.40 Objections noted, on the morning of 2 November, the attack went ahead. The initial Chilean landing force of 450 made its final approach in open rowboats under heavy fire.41 Once ashore and constrained by bottlenecks on the beach, it took what must have been an unbearably long hour for the second Chilean wave to arrive. Despite these shortcomings, the allies—now under naval gunfire and a disciplined Chilean assault—broke and retreated toward high ground.42 A third Chilean wave disembarked in the early afternoon as the advance continued into the hills above Pisagua, completing a rout of the allied defenders.43 One Bolivian battalion lost 298 of its 498 personnel, well in excess of the total casualties suffered by the invading Chileans (though an untold number of the Bolivian losses were desertions).44

In comparison to the action at Pisagua, the landings at Junin with a smaller force of 2,100 troops went smoothly. Apparently, the allies fled in response to preparatory naval shelling.45 More challenging were environmental factors: friction affects amphibious operations in peculiar ways even in the absence of the enemy’s will. Heavy surf and rocky disembarkation points meant that by the time the attacking Chileans had moved ashore at Junin, the fighting at Pisagua had concluded.46 So much for a coordinated assault.

Despite the challenges, Chilean forces now had a beachhead in Tarapacá Province. But that position was a tenuous one. As Chilean forces consolidated in Pisagua, Iquique remained in Peruvian hands while thousands of Bolivian and Peruvian troops mobilized farther north. Exacerbating matters, water supplies in Pisagua were insufficient to support the armed forces and civilian inhabitants, even when supplemented by the flotilla’s ship-borne water condensers.47 A lack of medical staff ashore (a critical oversight in planning by the army commander Erasmo Escala) was another challenge, only adding to the insecurity of the Chilean position and the misery of the men clinging to it.48

The Andean allies responded to the invasion with (on paper) overwhelming force. Attempting to counterattack against the Chilean beachhead, Bolivia’s military dictator, Hilarión Daza, brought thousands of troops down from the Bolivian highlands to the coast. Flogging (sometimes literally) his forces on, the Bolivians’ final push through the arid wastes of Tarapacá Province was woefully undersupplied. After marching south for three days, Daza gave up and returned north to the Peruvian port of Arica. When Chilean and allied forces eventually met at the Battle of Dolores (or the Battle of San Francisco) on 19 November, 7,200 allied troops charged Chilean forces dug in on high ground and supported by artillery. Results were predictable and as the official history has it, “the Chilean triumph was unquestionable.”49 Soon after, Peruvian defenders abandoned Iquique and retreated into the desert.50 Now unopposed, Chilean troops disembarked and occupied the port of Iquique proper on 23 November 1879.51

Taken together, Chilean victory in the campaign for Iquique illustrated the advantages and difficulties of sea power projected ashore. The Chilean army was able to move along the desert in ways that were difficult (and often fatal) for the numerically superior Andean allies to attempt overland. The occupation of Pisagua and Iquique offered the Chilean military its first foothold in the campaign north toward Lima. It also denied the Peruvian government access to nitrates revenues from Tarapacá—crucial assets to finance the war and a core aim of Chilean territorial aggrandizement. That said, success could not obscure glaring weaknesses in Sotomayor and Escala’s planning and execution: for example, insufficient water supplies and poor beach selection. Still greater tests loomed ahead in the next phase of the amphibious campaign.

Phase III: Tacna and Arica

The fall of Iquique was a strategic and political disaster for the Andean allies. The Bolivian leader Daza lost power in a coup and fled to Europe. Facing growing political opposition, Peru’s president Mariano Ignacio Prado followed suit (ostensibly on a mission to procure warships to replace the Huáscar). In Lima, Nicolás de Piérola took Prado’s place, promising to mobilize Peru’s remaining reserves of men and materiel against the Chilean advance, which gathered apace.

The second phase of Chile’s port hopping began in earnest in February 1880, targeting the allied garrisons at Arica and the inland city of Tacna.52 Some in Chile argued for proceeding directly against Callao from Iquique, but Chilean political leaders cautioned against leapfrogging Peru’s armies in the south.53 Not only would these bypassed garrisons endanger the rear of a Chilean offensive, but Tacna Province also offered the best water and forage for pack animals; once again the Pacific Slope’s climate shaped the scope of possible operations.

The port of Arica was heavily fortified, creating tactical challenges for a direct attack by sea. Above the city, the 700-foot cliff El Morro sprouted artillery as Peruvians hastily improved the city’s defenses. Below, a U.S. Civil War-era ironclad monitor patrolled the harbor, an antiquated but still credible threat (as harassing Chilean ships learned the hard way in February 1880).54 In March 1880, the Peruvian Unión even made an intrepid resupply run into Arica, darting under the nose of the Chilean blockade to deliver Gatling guns and a small torpedo boat.55

As at Iquique, the solution to Arica’s defensive preparations was to land in a flanking position at the enemy’s rear—not unlike the U.S.–United Nations landings at Inchon during the Korean War. In this case it was the small port of Ilo, 322 kilometer north of the Chilean base at Pisagua and 113 kilometers north of Arica. By mid-February, Chilean forces had mustered four divisions of troops at Pisagua, along with 19 ships and hastily finished barges to transport the landing force.56 Sotomayor and Escala had learned lessons from the Iquique operation. Chilean advanced units provided close reconnaissance of the beaches ahead of the attack and some thought was given on how to better move troops from ship-to-shore on purpose-built landing craft.57 Most importantly, unlike at Pisagua, Ilo was undefended. Most units arrived on the docks with dry feet and moved to occupy the nearby city of Pacocha, consolidating their hold on the area by the end of February 1880.

From there, however, difficulties multiplied. Huddled beneath the fleet’s guns and hesitant to venture into the desert interior, Chilean forces attempted to lure the Peruvian Army of the South into counter attacking across the arid landscape.58 Chilean raids escalated steadily, hoping to provoke a response. In early March, a small Chilean amphibious landing against the nearby port of Mollendo broke down into looting and riots. Reports of that attack generated outrage in Peru, but little concrete retaliation from the allies.59

Later that same month, slow progress (and simmering political feuds with Sotomayor) led to the replacement of General Escala by Manuel Baquedano as commander in the field.60 Baquedano moved with new, but not always wise, purpose against the Peruvian garrisons. His target was the town of Tacna, a 129-kilometer march inland from the beachhead.61 Venturing overland against the allied forces meant crossing a hostile space about which the Chileans knew little—despite some unhappy cavalry forays into the desert.62 Baquedano’s troops paid a high price for that ignorance. Ravaged by mosquitoes, diseases reduced the army’s effective numbers by nearly 20 percent.63 Sotomayor—the man who had done more than anyone to organize the amphibious campaign—died of a stroke in a desert encampment on 20 May 1880.64

Despite exhaustion and disease, a week later, on 26 May 1880, 14,000 Chileans engaged and defeated a comparable force of allied troops at Alto de la Alianza.65 Making a direct frontal attack in the heat of the afternoon against a prepared allied defense, Chilean forces managed to carry the ground at bayonet point.66 While Chilean casualties were heavy, the allied army more or less disintegrated; handfuls of Peruvian and Bolivian troops broke for Arica or the foothills of the Andes. Thereafter, thousands of wounded soldiers of all nationalities faced infection and death in unsanitary battlefield hospitals, or else a protracted and miserable journey to Valparaiso (via the Chilean Navy) or Callao (via the Red Cross).67

Tacna in hand, the road opened south to Arica: an essential waypoint for an advance north on Lima as well as the last point of Peruvian resistance that could conceivably arrest the Chilean offensive.68 The defenses here—as noted above—were substantial; certainly more formidable than those that had nearly scuttled Chilean amphibious operations at Pisagua. In addition to fortifications and warships, the Peruvian inventor Teodoro Elmore deployed electrically and pressure-detonated land mines. Unluckily for the Peruvians, advanced units of the Chilean army captured Elmore and forced him to divulge the locations of his minefields.69

Marching south along the rail and road network linking Tacna to Arica, the advancing Chileans cooperated with the fleet in several respects before storming the city. In advance of the ground assault, the Chilean navy also bombarded the port, trading fire with coastal batteries for hours in a fantastic display that nonetheless failed to coerce the Peruvians into surrender.70 A land attack followed the next day. Despite heroic and sometimes tragicomic acts of resistance by the Arica’s defenders, Chilean forces carried the forts. Famously, the Peruvian officer Alfonso Ugarte wrapped himself in the national colors and spurred his horse off the side of El Morro rather than surrender.71 More practically, the crew of the Manco Capac (1865) scuttled the ship to avoid capture, completing the defeat.72

Together, the campaigns against Iquique and Arica secured likely embarkation points for a campaign against Lima while also denying Peru the nitrate wealth needed to fund its war effort.73 The Chilean victory at Tacna, furthermore, had the effect of knocking Bolivia out of the war for all practical intents and purposes.74 For Chilean naval forces, victory at Arica freed naval assets to tighten the blockade at Callao, bottling up Peruvian cruisers and preventing resupply operations to garrisons south of Lima.75 On the one hand, naval forces helped secure bases for future “hops” north, while on the other amphibious landings captured ports to support future naval operations. Peru now faced invasion alone and isolated; a position of desperation that prompted new and innovative methods of littoral defense in the hopes of disrupting the SLOCs on which the Chilean amphibious advance now depended.

Peruvian Littoral Defense: Technologies and Tactics of Asymmetric Resistance

While the army campaigned against Tacna and Arica, the Chilean admiral Galvarino Riveros deployed his forces to blockade Callao and harass Peruvian coastal settlements. The capture of the Rimac and the Unión raid around the blockade at Arica loomed as cautionary examples of the potential of Peru’s cruiser war.76 This effort was largely successful. In March 1880, the Peruvian Oroya (1873) left Callao to harass Chilean SLOCs, but failed to do meaningful damage as the Peruvian guerre de course came to a close, the Peruvian navy well and truly driven from the sea.77

For Riveros, Lima’s adoption and deployment of torpedoes and torpedo boats was a still more worrying development: unproven but potentially devastating technologies capable of upsetting Chilean investments in heavy, oceangoing armored ships.78 Ambitions for these new weapons were high if not always realistic. After the loss of the Huáscar, the Unión was fitted out with such a variety of torpedoes that the Ministry of the Navy lost count.79 Incredibly enough, the Peruvian inventor Federico Blume even built a functional submarine. He hoped the vessel could attack the Chilean ironclads—but it never got the chance.80 Proposals from overseas promised still more fantastic results from submarine weapons and warships.81 On the ground, and in contrast to these vaulting expectations, the torpedo’s teething pains were starkly apparent to the men trying to employ them.82 No Chilean ships were sunk by automobile torpedoes during the war owing to technical difficulties and integration challenges. The first successful use of a torpedo to sink an ironclad vessel—fittingly enough given all this practical exposure—came 10 years later during the Chilean Civil War (1891).83

At the time, failure to challenge Chilean naval supremacy with imported weapons led to still more inventive (if low-tech) schemes. Twice in the course of the war, improvised explosive devices (barcas-trampa) detonated alongside Chilean warships, sinking them at great human cost.84 The Loa (1854) fell victim to a launch carrying fresh fruit and a large explosive. The Covadonga was taken in by a similar subterfuge—much to the outrage of the Chilean press and high command.85 The destruction of the Loa and the Covadonga spread a numbing dread about torpedoes across the Chilean fleet: an epidemic of “topeditis” quipped one observer at the time.86 Responding to the attacks, Chilean warships shelled unfortified ports in Peru, to little effect other than to generate misery for the inhabitants.87

For all the ingenuity of the Peruvian assymetric effort, Chilean SLOCs remained intact, ready to sustain the next hop north. Failure, however, should not imply that the Peruvian innovations were inconsequential. In fact, by leveraging new technologies and even expanding the dimensions of industrial war to the undersea environment, Peruvian forces showed a path toward the twentieth century. Cheap, asymmetric weapons deployed by the Peruvians had as much in common with Confederate mines (or as Farragut called them torpedoes) and semisubmersible warships as they did submarine warfare in the World Wars. In both cases the defeat or suppression of asymmetric threats to sea communications was a prerequisite for larger amphibious invasions. As a matter of technological development, the Peruvian efforts to harass the Chilean lines of communication were the most innovative achievements of the war and a persistent problem of amphibious operations down to the present day.

Phase IV: To Lima

All of this—the campaigns at Iquique, Tacna, Arica, and the blockade of Callao—was preparation for the ultimate goal of the war: an advance on Lima that would force Peruvian leaders to the peace table and legitimate the Chilean annexation of territory.88 Pure sea power was insufficient to achieve this result in the near or intermediate term. Major combat operations through amphibious action—or else a successful diplomatic intervention by an interested third party—remained necessary to bring the war to a conclusion.89

A test case for the invasion came in the form of still more amphibious raids, now by Patricio Lynch against the plantation estates of northern Peru in September 1880.90 Supported by two armed transports and the warships Chacabuco (1866) and O’Higgins (1866), Lynch landed with more than 2,000 troops near Chimbote, some 322 kilometers north of Lima, bypassing the garrisons there and, as General Douglas MacArthur might have put it, “hitting them where they ain’t.” From there, Lynch marched inland, declaring a war tax on local haciendas. When Peruvian landowners refused to pay, the Chileans destroyed property, tore up railroads, and liberated Chinese “coolies” impressed under truly dire conditions. The redheaded Lynch gained the sobriquet “Red Prince”—Principe Rojo—from the Chinese he won over to his campaign.91 Marching inland, Lynch made Peru howl “systematically and without pity.”92 Satisfied (or perhaps because he faced growing criticism from foreign diplomats), Lynch re-embarked in November 1880, sailing south after two months of campaigning.

Lynch’s expedition occupied attentions and honed skills as the Chilean army proper prepared for the offensive on Lima. Baquedano divided forces into three groups with the aim of reducing strains on Chilean maritime transport capabilities. This—the greatest logistical challenge of the war—involved the movement of 24,000 troops and many thousands of pack animals, all consuming well more than a quarter-million liters of water per day.93 Alongside rented steamships, the Chileans also mustered 35 sailing boats and specially designed launches to ferry personnel and artillery to shore—absorbing lessons from the frictions of the landings at Junin and Pisagua. The logistics of the operation were further complicated by the need to move troops and supplies from Valparaiso to Arica and then onto Lima’s environs in a two-phase process; in this case less of a hop and more of a triple jump up the coast.

Moving from Arica, the 1st Division landed near Pisco on 19 November 1880. The garrison there surrendered after naval shelling.94 A second wave of troops and animals left Arica on 27 November, arriving in Pisco in 2 December 1880, bringing troop numbers there to 12,000. Two weeks later, a final wave consisting of 14,000 fighters in 28 transports brought the bulk of the army north, via a stop in Pisco to re-embark troops there.95 While these forces organized, a party onboard the Cochrane took the small port city of Chilca, only 64 kilometers south of Callao, cutting its telegraph lines and reconnoitering the route north.96 The Chilean main force made land on 22 and 23 December, occupying Lurin, within striking distance along the road to Lima.97 Marching overland, Lynch’s division—along with what the official Chilean military history calls the “Chinese slaves” he liberated—and Baquedano’s main force rallied on 26 December 1880.98 At sea, warships not dedicated to escorting convoys maintained the blockade of Callao. The Angamos even managed to use the range of its guns to harass Peruvian fortifications.

As Chilean forces edged north, Piérola goaded Lima’s citizens into defensive preparations. Peru’s best armies may have been defeated at Arica and Tacna, but the population under arms still made for a credible defense: the people in mass responding to the emergency of foreign invasion. Piérola managed to muster more than 29,000 troops (of mixed quality) into the armed forces to defend Lima, reinforced with weapons from Europe and the United States.99

Quantity may have a quality all its own, but their inexperience told dearly. These hastily raised units failed against the battle-tested Chilean army, recently arrived by sea. At Chorrillos (13 January 1881) and Miraflores (15 January 1881), Chilean forces defeated what remained of the organized Peruvian resistance on the outskirts of Lima.100 Naval gunfire proved useful in these engagements, but as at Arica, the key role of the navy was to move the army into position. Lima and Callao fell on 17 January 1881. The first Chilean naval officer to enter Callao—Lieutenant Silva Palma—did so on horseback, leading a detachment of cavalry.101 Peruvian naval units scuttled their remaining assets, sinking the ironclad monitor Atahualpa (1864) with a torpedo.102 After receiving communications from the shore, the torpedo boat Fresia (1881) raced to be the first Chilean ship to enter the harbor, using its speed in an act of sport more than military proficiency.103

In all, it was a remarkable display of amphibious power against considerable obstacles. Chilean officials remembered fighting “on the sea and in the desert, combat[ing] the enemy, the climate and the thousand natural obstacles in a strange and unknown country.”104 Lima was the crowning achievement of that campaign. Contrary to Chilean expectations, however, Lima’s capture did not bring an end to the war. Peruvian factions retreated to the Andes where they would wage a running guerrilla war for months.105 As a result, even after major combat operations had ceased, the supply of the several thousand troops in the occupation army remained closely linked to the sea. As a fitting end to this continental war waged from the sea, the naval officer Patricio Lynch took on duties as the de facto last viceroy of Peru, overseeing the Chilean occupation from Lima.106

Conclusion: Applying Sea Power Ashore in the Industrial Age

Chilean victory in the War of the Pacific hinged on what might be called applied seapower: the ability to translate naval and maritime strength into concrete strategic and political results on land via an amphibious campaign. Perhaps it was no coincidence that Alfred T. Mahan (no less) was on station in the South American Pacific in 1884 to observe the results of Chilean victory. In fact, he did the basic research for The Influence of Sea Power upon History in one of Lima’s libraries.107 Just one year later—shortly after the end of guerrilla resistance in the highlands of Peru—the U.S. Navy and Marine Corps conducted their most ambitious amphibious operation in a generation: occupying Panama during a period of revolutionary unrest.108

On a longer timeline, the War of the Pacific was a precedent for the imperial wars of the late-nineteenth and twentieth centuries. In its impassable deserts overcome by joint amphibious operations, it shares familiar themes with the Italian invasion of Libya in the Italo-Turkish War (1911–12) and the British campaign against German South West Africa (1914–15).109 As a case study of hostile shores seized by landing forces, students of the Japanese blitz against the Philippines, the Marine Corps’ island-hopping campaign across the South West Pacific, or the landings at Inchon during the Korean War will likewise find familiar echoes in the War of the Pacific. Generalizable trends across these examples suggest lessons about the nature of amphibious operations and maritime warfare.

Seapower, broadly conceived, supported continental operations on two levels during the War of the Pacific. First, naval preponderance was a precondition for the movement of troops and materiel along the desert coast. Quoting from Sir Francis Bacon, Corbett observed in 1911 that “he that commands the sea is at great liberty and may take as much or as little of the war as he will whereas those that be strongest by land are many times nevertheless in great straits.”110 True enough for the Spanish Armada and Wellington’s Peninsular Army, and true enough during the War of the Pacific. Picking its battles, the numerically inferior Chilean army notched a string of victories against Peru and Bolivia. Movement by sea allowed Sotomayor to bypass strong points and strike where he pleased up the Peruvian coast. That same naval preponderance also allowed for blockades that degraded the allies’ military capabilities over time; not least by forcing marches across impassable deserts. Second, seapower in the form of the Chilean merchant marine enabled the movement of troops and materiel 2,414 kilometers north from Valparaiso to the seat of the war. During the war, the Compania Sudamericana de Vapores and Compania Explotadora de Lota y Coronel moved tens of thousands of personnel and animals, alongside an amount of coal and water that would have been difficult to fathom a generation earlier.111 Less tangibly, many Chileans believed that the strength of the Chilean navy staved off external (notably U.S.) intervention in the conflict on behalf of Peru; yet another respect in which control of the sea enabled operations on land.112

All that said, naval force was not determinative and any argument that suggests as much underestimates the contingency and reciprocity of the amphibious campaign. Seapower was not enough. In the same way that the Confederate defenders of Charleston Harbor only succumbed to General William T. Sherman’s overland army in 1865 after years of pressure from the sea, so too did Callao resist pure naval power throughout the war. Likewise, Chilean attempts at terror shelling did little to weaken Peruvian resistance. A blockade of the coast may have toppled Peru’s government eventually, but for the time Peru retained its army in the field. Most of Chilean territorial aggrandizement occurred in the seizure of Tacna and Arica in the first months of the war, but compelling Peru to a peace settlement was another matter. The core issue remained to be settled by major combat in the environs of Lima and ultimately a vicious assault against the rump Peruvian government sheltering in the Andes. Seapower was a necessary but insufficient cause of Chilean victory.

Moreover, operations on land were not simply downstream effects of sea control. Rather, many continental operations reinforced Chilean naval efficacy. Amphibious operations supported sea power as much as sea power enabled amphibious operations. Earl Ellis would make a similar observation in the interwar period as he considered the future role(s) of the Marine Corps as an auxiliary of fleet operations against the Imperial Japanese Navy.113 Naval gunfire and medical services supported army operations ashore, but the army also seized ports and supply depots on the Pacific slope to sustain naval operations. Overland attacks at Arica reduced coastal defense fortifications that the Chilean navy was otherwise powerless to dislodge, providing safe anchor and denying the ports to Peruvian raiders. The relationship between sea and land was, as such, a reciprocal one.

That reciprocity, however, created as many challenges as opportunities for Chilean officials. Getting units off ships and onto shore was a constant and often deadly fiasco. Bureaucratically, debates between civilian, military, and naval leaders were another key drama of the war. The challenge of joint interoperability is an old one. Navy officials resisted cooperation with the army. Army leaders never fully trusted the navy. Such squabbles reflected the complexity of amphibious operations alongside their advantages in the formative years of modern-industrial war.

In all these respects, the War of the Pacific pointed the way forward to the twentieth century and perhaps beyond. There are few (if any) causal links between the War of the Pacific and interwar U.S. war planning, though the war was well-known to the growing U.S. intelligence apparatus. The parallels between the War of the Pacific and major amphibious operations in World War II are telling, nonetheless. Interwar thinkers engineered their way to defeating the distance of the Atlantic and Pacific oceans, responding to the geostrategic position of the United States with the technologies and tactics of amphibious operations.114 These thinkers responded to the same stimuli as Chilean forces under Sotomayor, who articulated the strategy of the “port-hopping war” as a matter of exigent necessity. The basic process, winning command of the sea and then deploying amphibious forces “step-by-step” as a reciprocal tool of sea power, was as relevant to the War of the Pacific as it was the coming Pacific War in 1941. Whether one emphasizes the challenges overcome by Chilean leaders to engage in successful amphibious operations, or the ingenuity of Peruvian engineers attempting to defend against them, the War of the Pacific offers lessons from the past that are unmistakable in the present.

Endnotes

- For surveys, see William F. Sater, Andean Tragedy: Fighting the War of the Pacific, 1879–1884 (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2007); Carlos López Urrutia, La Guerra del Pacífico (Madrid, Spain: Ristre Media, 2003); Bruce W. Farcau, The Ten Cents War: Chile, Peru, and Bolivia in the War of the Pacific, 1879–1884 (Westport, CT: Praeger, 2000); Roberto Querejazu Calvo, Guano, Salitre, Sangre: Historia de la Guerra del Pacifico (La Paz, Bolivia: Editorial Los Amigos del Libro, 1979); and Jacinto López, Historia de la Guerra del Guano y el Salitre (Lima, Peru: Editorial Universo, 1980). For naval combat, see Carlos López Urrutia, Historia de la Marina de Chile (Santiago, Chile: Andrés Bello, 1969); and Jorge Ortiz Sotelo, La Armada en la Guerra del Pacífico Aproximación Estratégica-Operacional (Lima, Peru: Asociación de Historia Marítima y Naval Iberoamericana, 2017). Official studies include Comisión para Escribir la Historia Marítima del Perú, Historia Marítima del Perú, Tomo X (Lima, Peru: Instituto de Estudios Histórico-Marítimos del Perú, 1988); Patricia Arancibia Clavel, Isabel Jara Hinojosa, and Andrea Novoa Mackenna, La Marina en la Historia de Chile, Tomo I (Santiago, Chile: Sudeamericana, 2005); and Virgilio Espinoza Palma, Historia del Ejército de Chile, Tomo V (Santiago, Chile: Estado Mayor General del Ejército, 1980).

- The Question of the Pacific (Washington, DC: U.S. Department of State, 1919). See also William Jefferson Dennis, Tacna and Arica: An Account of the Chile-Peru Boundary Dispute and of the Arbitrations by the United States (New York: Archon Books, 1967); and Evan Fernandez, “Pan-Americanism and the Definition of the Peruvian-Chilean Border, 1883–1929,” Diplomatic History 46, no. 2 (April 2022): 292–319, https://doi.org/10.1093/dh/dhab090.

- Jeffrey M. Dorwart, The Office of Naval Intelligence: The Birth of America’s First Intelligence Agency, 1865–1918 (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 1979), 9.

- Though it escapes mention in Assault from the Sea: Essays on the History of Amphibious Warfare, ed. LtCol Merrill L. Bartlett, USMC (Ret) (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 1983).

- Used in this sense by Paul Kennedy, Engineers of Victory: The Problem Solvers Who Turned the Tide in the Second World War (New York: Random House, 2013), 283.

- As to the analogy of port hopping versus island hopping, it is absolutely true that the island-hopping campaign had more intellectual coherence, the result of years of planning dating at least to Earl H. Ellis in 1921. However, the improvisational nature of the port-hopping campaign is quite revealing. Without a record of war in the industrial era on which to base assumptions, port hopping emerged as an organic response to defeat the tyranny of distance. The U.S. Marine Corps’ island hopping during the period is not a unique insight, but it reflects the basic nature of distance and logistics under the conditions of industrial warfare.

- Arne Roksund, The Jeune Ecole: The Strategy of the Weak (Boston, MA: Brill, 2007); and Theodore Ropp, The Development of a Modern Navy: French Naval Policy, 1871–1904, ed. Stephen Roberts (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 1987).

- Benjamin Vicuña Mackenna, Historia de la Campaña de Tarapacá Desde la Ocupacion de Antofagasta Hasta Proclamacion de la Dictadura en el Perú (Santiago, Chile: Pedro Cadot, 1880), 259. Domestic political pressure, expansionism, and “national honor” played roles as well. See Sater, Andean Tragedy, 13–19, 37–40.

- JoAnna Klein, “If Algae Clings to Snow on this Volcano, Can It Grow in Other Desolate Worlds?,” New York Times, 15 July 2019.

- The Coasts of Chile, Bolivia, and Peru (Washington, DC: U.S. Hydrographic Office, 1876), 265.

- Clements R. Markham, War between Perú and Chile, 1879–1882 (London, UK: Sampson Low, Marston, 1883), 93.

- T. B. M. Mason, The War on the Pacific Coast of South America Between Chile and the Allied Republics of Peru and Bolivia, 1879–81 (Washington DC: Government Printing Office, 1885), 13.

- Herbert Wilson, Ironclads in Action: A Sketch of Naval Warfare from 1855 to 1895, vol. 1 (Boston, MA: Little, Brown, 1896), 314; and La Guerra Del Pacífico, 15.

- Alfred Thayer Mahan, The Influence of Sea Power upon History (Boston, MA: Little, Brown, 1890).

- E. Chouteau, “Introducción,” Revista de la Marina, no. 1 (July 1885): 6–7, emphasis in original; and Robert B. Seager II, “Ten Years Before Mahan: The Unofficial Case for the New Navy, 1880–1890,” Mississippi Valley Historical Review 40, no. 3 (1953): 491–512.

- Julian S. Corbett, Some Principles of Maritime Strategy (London: Longmans, Green, 1918), 77–78.

- La Marina en la Historia de Chile Tomo I, 445–46; and Ortiz, La Armada en la Guerra del Pacífico, 43.

- López, La Guerra del Pacífico, 44.

- Sater, Andean Tragedy, 133.

- Ortiz, La Armada en la Guerra del Pacífico, 43.

- Ropp, The Development of a Modern Navy. The French “Young School” consisted of a group of naval officers who sought to use cruisers and torpedo boats to compete asymmetrically with the Royal Navy in the late-nineteenth century.

- J. W. King, Warships and Navies of the World (Boston, MA: Williams, 1881), 439–41.

- “Composición de Nuestro Material Naval,” Revista de Marina, no. 76 (September 1892): 76.

- López, La Guerra del Pacífico, 52.

- Sater, Andean Tragedy, 146–48.

- Markham, War between Perú and Chile, 115.

- La Marina en la Historia de Chile, Tomo I, 453.

- López, La Guerra del Pacífico, 52; and La Marina en la Historia de Chile, 451.

- López, La Guerra del Pacífico, 56.

- French Legación, “Octubre 29, 1897,” in Informes Inéditos (Santiago: Andrés Bello, 1980), 270.

- López, Historia de la Marina de Chile, 279; and La Marina en la Historia de Chile, 461.

- “El Rol de los Vapores Mercantes Nacionales,” Revista de Marina, no. 6 (December 1885): 657.

- Robert Albion, Makers of Naval Policy, 1798–1947 (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 1980), 574.

- Maj Earl H. Ellis, Advanced Base Operations in Micronesia, Fleet Marine Force Reference Publication 12-46 (Washington, DC: Headquarters Marine Corps, 1992), 9.

- La Marina en la Historia de Chile, 440.

- Sater, Andean Tragedy, 171; and Benjamin Vicuña Mackenna, Historia de la Campana de Tarapacá (Santiago, Chile: Imprenta Cervantes, 1880).

- Nicanor Molinare, Asalto y Toma de Pisagua: 2 de Noviembre de 1879 (Santiago, Chile: Imprenta Cervantes, 1912), 82–83; and Sotelo, La Armada en la Guerra del Pacífico, 98.

- “El Rol de los Vapores Mercantes,” 657.

- La Marina en la Historia de Chile, 444.

- Mackenna, Historia de la Campana de Tarapacá, 788.

- Historia del Ejercito de Chile, Tomo V (Santiago, Chile: Estado Mayor General Del Ejercito, 1980), 174; and Molinare, Asalto y Toma de Pisagua, 101.

- Mackenna, Historia de la Campana de Tarapacá, 788.

- Historia del Ejercito de Chile, Tomo V, 227; and López, La Guerra del Pacífico, 70.

- Sater, Andean Tragedy, 175–76.

- Historia del Ejército de Chile, Tomo V, 228; and Molinare, Asalto y Toma de Pisagua, 145.

- López, Historia de la Marina de Chile, 283.

- López, La Guerra del Pacífico, 71; and Historia del Ejército de Chile, Tomo V, 241.

- Sater, Andean Tragedy, 176.

- Historia del Ejército de Chile, Tomo V, 265.

- López, La Guerra del Pacífico, 74; and Historia del Ejército de Chile, Tomo V, 270, 301.

- La Marina en la Historia de Chile, 463.

- López, Historia de la Marina de Chile, 297.

- López, La Guerra del Pacífico, 77; and Sater, Andean Tragedy, 213.

- La Marina en la Historia de Chile, 465; and Historia del Ejército de Chile, Tomo VI, 115.

- López, Historia de la Marina de Chile, 290.

- Sater, Andean Tragedy, 217. López’s numbers vary. López, La Guerra del Pacífico, 84.

- Historia del Ejército de Chile, Tomo VI, 48; and Sater, Andean Tragedy, 217.

- Historia del Ejército de Chile, Tomo VI, 50.

- López, La Guerra del Pacífico, 84; and Historia del Ejército de Chile, Tomo VI, 55.

- Historia del Ejército de Chile, Tomo VI, 74.

- Sater, Andean Tragedy, 225.

- Historia del Ejército de Chile, Tomo VI, 93.

- Sater, Andean Tragedy, 227; and Historia del Ejército de Chile, Tomo VI, 97.

- Benjamín Vicuña Mackenna, Historia de la Campana de Tacna y Arica, 1879–1880 (Santiago, Chile: Rafael Jover, 1881), 217, 886–88; and Historia del Ejército de Chile, Tomo VI, 97.

- Sater, Andean Tragedy, 227; and López, La Guerra del Pacífico, 77.

- Historia del Ejército de Chile, Tomo VI, 111–12; and López, La Guerra del Pacífico, 92.

- Sater, Andean Tragedy, 245.

- Ortiz, La Armada en la Guerra del Pacífico, 140.

- Sater, Andean Tragedy, 250; and Mackenna, Historia de la Campana de Tacna y Arica, 1118–19.

- López, La Guerra del Pacífico, 95.

- Sater, Andean Tragedy, 253. Perhaps he was attempting to descend, but the melodrama makes for better retelling. Mackenna, Historia de la Campana de Tacna y Arica, 1149–50.

- Historia del Ejército de Chile, Tomo VI, 123.

- La Marina en la Historia de Chile, Tomo I, 466.

- Historia del Ejército de Chile, Tomo VI, 114.

- López, Historia de la Marina de Chile, 287. For the blockade of Arica, see López, Historia de la Marina de Chile, 288–89. For the blockade of Callao, see López, Historia de la Marina de Chile, 292.

- La Marina en la Historia de Chile, Tomo I, 465.

- López, Historia de la Marina de Chile, 291.

- While it is true that the technologies to which Peruvian officers turned as a matter of necessity in 1880 (and beyond) failed to alter the strategic outcome of the war, they had the effect of complicating Chilean operations. Things can be relevant and not strategically determinative.

- Portal, “November 29, 1879,” in Diario a bordo de la Corbeta Unión: Guerra del Pacífico: Testimonios Inéditos, ed. Hernán Garrido-Lecca (Lima, Peru: La Casa Del Libro Viejo, 2008), 130.

- Robert Scheina, Latin America: A Naval History, 1810–1987 (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 1987), 36; Watt Stewart, “Federico Blume’s Peruvian Submarine,” Hispanic American Historical Review 28, no. 3 (August 1948): 468–78, https://doi.org/10.1215/00182168-28.3.468; and Jorge Ortiz Sotelo, Apuntes para la Historia de los Submarinos Peruanos (Lima, Peru: Biblioteca Nacional del Perú, 2001), 26–32.

- For example, “Ericsson’s New Torpedo,” New York Times, 1 September 1880.

- “Grau to Director de Marina, August 31, 1879,” in Diario a Bordo del Huáscar, ed. Robert Hunter (Buenos Aires, Argentina: Francisco De Aguirre, 1977), 138–39; and “Portal to Mayor del Departamento, November 29, 1879,” in Diario a Bordo de la Corbeta Unión, 130.

- “Sunk by Torpedoes,” New York Times, 28 April 1891.

- La Marina en la Historia de Chile, Tomo I, 468.

- López, Historia de la Marina de Chile, 298–99.

- Sater, Andean Tragedy, 167; and López, Historia de la Marina de Chile, 298.

- López, Historia de la Marina de Chile, 300.

- López, Historia de la Marina de Chile, 303.

- Historia del Ejército de Chile, Tomo VI, 153.

- López, La Guerra del Pacífico, 106.

- For “Red Prince,” see B. V. Mackenna, El Álbum de la Gloria de Chile, El Álbum de la Gloria de Chile, vol. 1 (Santiago, Chile: Imprenta Cervantes, 1883), 12.

- López, Historia de la Marina de Chile, 300; and Sater, Andean Tragedy, 259–62.

- Sater, Andean Tragedy, 264. And this is only a fraction of the 24,000 troops in the expeditionary army. See López, La Guerra del Pacífico, 112.

- Sater, Andean Tragedy, 265; and López, La Guerra del Pacífico, 116.

- López, Historia de la Marina de Chile, 303; and Sater, Andean Tragedy, 268.

- López, Historia de la Marina de Chile, 303.

- Sater, Andean Tragedy, 269.

- López, La Guerra del Pacífico, 117; and Historia del Ejército de Chile, Tomo VI, 191.

- Historia del Ejército de Chile, Tomo VI, 174.

- Historia del Ejército de Chile, Tomo VI, 203–16; and López, La Guerra del Pacífico, 119–40.

- López, Historia de la Marina de Chile, 306.

- Sater, Andean Tragedy, 296.

- López, Historia de la Marina de Chile, 307.

- “Defensa de Nuestro Litoral,” Revista de la Marina (August 1885).

- Sater, Andean Tragedy, 301; and Historia del Ejército de Chile, Tomo VI, 229.

- La Marina en la Historia de Chile, 471; and Patricio Lynch, Memoria de Operaciones en el Norte del Perú (Lima, Peru: Imprenta Calle 7, 1882).

- Larrie D. Ferreiro, “Mahan and the ‘English Club’ of Lima, Peru: The Genesis of The Influence of Sea Power upon History,” Journal of Military History 3, no. 72 (July 2008): 901–6, https://doi.org/10.1353/jmh.0.0046.

- LtCol Merrill L. Bartlett, USMC (Ret), ed., Assault from the Sea: Essays on the History of Amphibious Warfare (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 1985), 107.

- Edward Paice, World War I: The African Front: An Imperial War on the African Continent (New York: Pegasus Books, 2008); and “The Navy of the Kingdom of Italy,” in The Oxford Encyclopedia of Maritime History, vol. 2, ed. John B. Hattendorf (Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 2007), 716.

- Corbett, Some Principles of Naval Strategy, 48.

- López, Historia de la Marina de Chile, 307–8; and “El Rol de los Vapores Mercantes Nacionales en la Pasada Guerra del Pacífico,” Revista de Marina, no. 6 (December 1885): 657.

- William Sater, Chile and the United States: Empires in Conflict (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1990); and Stephen Brown, “The Power of Influence in United States-Chilean Relations” (PhD diss., University of Wisconsin-Madison, 1983).

- Ellis, Advanced Base Operations in Micronesia, 29.

- John T. Kuehn, Agents of Innovation: The General Board and the Design of the Fleet that Defeated the Japanese Navy (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 2008); and David Nasca, The Emergence of American Amphibious Warfare, 1898–1945 (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 2020).