Adam Christopher Nettles

https://doi.org/10.21140/mcuj.20221302006

PRINTER FRIENDLY PDF

EPUB

AUDIOBOOK

Abstract: This article outlines the evolving geopolitical situation in the Black Sea in the context of Russia’s recent invasion of Ukraine. It establishes a historically rooted pattern in Russian strategy tied to the region that runs through most recent acts of Russian aggression against its neighbors. It illustrates how after each Russian conflict with its neighbors in the last 20 years Russia has gained more physical coastline on the Black Sea. It roots this behavior in a centuries-long pattern of Russian behavior grounded in practical and ideational motivations. Accordingly, it establishes that Russian aggression in the Black Sea is likely to be a persistent fixture of global great power competition for the near future. The author then proposes a sustainable solution to counter Russian aggression in the theater through U.S. support of the current trend toward increased European “strategic autonomy” within the bounds of the NATO alliance.

Keywords: Ukraine invasion, Black Sea security, European security, transatlantic policy, NATO, strategic autonomy, Russian strategy, naval strategy, European integration

Part 1: The Black Sea Thread

Persistent Great Power Competition

As the Russians moved toward Kyiv in the first weeks of Russia’s 2022 invasion of Ukraine, a host of different theories as to Vladimir Putin’s objectives flooded the discourse. The simple reality, though, is that no one can be completely certain what Putin’s objectives were in Ukraine at the onset, save the man himself. Some months into the war, however, we can now observe how the Russian military has prosecuted the conflict thus far. What can be seen is a Russian willingness to endure and inflict enormous costs in the south and east of Ukraine. Russia has shown a tenaciousness that was lacking in its attempts to capture the capital or Ukraine’s second city, Kharkiv.1 That is, in areas in Ukraine’s south, including along the Black Sea coast, Russian forces have accepted huge human and material costs for their slow but consistent gains.2 Though reports vary and are still subject to change, it would seem that in the Black Sea port of Mariupol alone Russia was willing to sustain somewhere between 4,000 and 6,000 fatal casualties capturing the city.3 For comparison, in the entire war in Iraq, the Defense Department numbers put equivalent American casualties at 4,431 during a period of eight years.4 Though reliable casualty counts in this conflict likely will not be compiled for some time, even this rough number illustrates that the cost Russia was willing to pay for the port city of Mariupol was a high one. This would suggest the area around the Black Sea is of critical importance to Russian strategists. When faced with mounting losses in the north by contrast, the Russians simply chose to withdraw and redeploy. These actions fit with what is posited here as a common thread tying the most recent acts of Russian aggression against Georgia in 2008, occupying Crimea in Ukraine in 2014, and the current invasion of Ukraine. When this pattern is taken as a whole, it suggests a strong Black Sea-centric focus in Putin’s long-term strategic calculations, which needs to be better explored in the context of Russian aggressive actions under Vladimir Putin.

The importance to Russia of the Black Sea is not a new phenomenon. Putin’s current policy making and military strategy would likely be recognizable to generations of Russian leaders, both imperial and Soviet.5 Russia has shown over generations that it is more than willing to make great sacrifices to control this critical naval theater. Put in solely geographic terms, it is important to note the Black Sea is closer to Moscow than the Gulf of Mexico is to Washington, DC.6 When this physical importance is paired with the deep historical and psychological meaning Russia attaches to the region, it is safe to conclude the area will remain a persistent and core interest to a resurgent Russia. This work will accordingly explore the ideational and geographic realities upon which this Black Sea thread rests. It will then outline how it ties recent acts of Russian aggression against its neighbors together and will conclude with recommendations for U.S. policy makers to best respond to this persistent geopolitical reality.

History Driving Policy

Given Russia’s increased use of history in justifying its political actions, seemingly distant historical realities now can have profound and clearly observable policy implications in Russian strategy. Goretti contends that Putin is “returning to the 19th century,” when referring to Putin’s statements in recent years on Russia’s imperial period.7 If one goes back further in Putin’s statements, however, it can be observed that Putin’s use of history in making Russian policy relies also on far more ancient events. There is an abundance of analysis lamenting Putin’s use of history, which he weaponizes to further his strategic goals and worldview.8 In Foreign Affairs, for example, Kolesnikov laments that Putin has committed crimes against history and Russia itself. He states that “trying to impose his version of the nation’s history, he deprived it (Russia) of its history. And by depriving it of history, he amputated the future. Russia is now at a dead end, a historical dead end.”9 It is fundamental to note, though, the core historical events on which Russia justifies its aggression are generally not invented. Putin’s interpretation of such events tends to be self-serving. Yet, the man is not reasoning on complete fiction when it comes to his use of history. This means that there is value in studying and understanding the complex recent and more ancient history of Russia if one wishes to explain these acts of aggression. Taken further, instead of lamenting this rhetorical pattern, Putin’s use of history provides Western decision makers with an excellent tool and an opportunity to better predict future Russian behavior. In Putin’s words, “To have a better understanding of the present and look into the future, we need to turn to history.”10 In this case, the West needs to look at and take seriously the man’s understanding of history to understand his behavior and to both prevent and respond to future acts of aggression. Perhaps the most blatant example of this telegraphing of future aggression can be seen in the cited article on Ukraine penned by Putin himself. In it, he outlines how Ukrainians and Russians are “one people” artificially divided by unjust borders following the fall of the Soviet Union. The piece reads like a history essay despite being a statement by an acting political leader. In the work, he all but telegraphed the invasion to correct the outlined historical wrongs eight months before it began. Accordingly, the first section of this piece will look at the previously mentioned Black Sea thread from a historical lens. It rests on the fact that Putin’s use of history gives such events causal relevance in explaining modern Russian acts of aggression.

Medieval Russia: Born on Black Sea Shores

Much analysis of Russia in the Black Sea sources the importance of the region to the seventeenth or eighteenth centuries, tying it to the rise of the Russian Empire. However, its profound psychological importance to the Russian historical memory goes back much further to the foundation of the Russian state.11 Putin said following Russia’s 2014 annexation of Crimea that “everything in Crimea speaks of our shared history and pride. This is the location of ancient Khersones, where Prince Vladimir was baptized.”12 As Putin emphasized here, Russia’s origins as a distinct state can indeed be rooted to events on Black Sea shores. The first distinctly Russian state in history, that of the Kievan Rus, adopted Orthodox Christianity roughly a century after its foundation in 988. Prince Vladimir, with whom Putin shares a first name, had for most of his life followed a local pagan faith. He then famously tested the major monotheistic options available to him before converting his kingdom. He considered Catholicism, Islam, and Orthodoxy, settling on the Greek choice in no small part because of the might and pomp of the Byzantine Empire just across the Black Sea.13 The formal act of this adoption was seen in the baptism of Prince Vladimir, the first Orthodox king of a Russian state. He was subsequently granted sainthood. As outlined, this occurred on the shores of the Black Sea near Sevastopol in Crimea. Even the Russian script can be traced to connections with the Byzantine Empire, as it was its missionaries in Saints Cyril (from whose name derives the term Cyrillic) and Methodius who provided the people of Rus and the East Slavs more generally with their first written language.14 The two are accordingly referred to as the “Apostles to the Slavs.”15 Therefore, the cultural and spiritual font of the Russian identity can be traced directly to Crimea, and by extension to sources along the shore of the Black Sea.

Some centuries following Prince Vladimir’s choice in the late medieval period, a geopolitical seismic shift occurred in the region that would have profound consequences on Russia’s relationship with the theater. With the fall of Constantinople and with it the Byzantine Empire to the Ottomans in 1453, the seeds of Russia’s understanding of itself as a divinely sanctified imperial power were planted. Some Russian theologians, politicians, and intellectuals began to understand Russia as what is referred to as the “Third Rome.” The first articulation of the concept can be traced to a Russian monk named Philotheus of Pskov who had regular contact with the Russian tsar at the time. The key passage he penned that first made the Third Rome concept explicit is the following:

I would like to say a few words about the existing Orthodox empire of our most illustrious, exalted ruler. He is the only emperor on all the earth over the Christians, the governor of the holy, divine throne of the holy, ecumenical, apostolic church which in place of the churches of Rome and Constantinople is in the city of Moscow. . . . It alone shines over all the earth more radiantly than the sun. For know well, those who love Christ and those who love God, that all Christian empires will perish and give way to the one kingdom of our ruler, in accord with the books of the prophet, which is the Russian empire. For two Romes have fallen, but the third stands, and there will never be a fourth.16

This concept framed Russia as heir to an imperial mantle founded in Rome, which subsequently moved to Constantinople on Rome’s collapse. Once Constantinople then fell to the Islamic empire of the Turks, Russian elites then posited that the natural heir to this legacy was Moscow, the only major Orthodox capital with the necessary imperial credentials to justify such a claim. It was resting on this concept in 1547 that what was previously the Grand Duchy of Muscovy rebranded itself as the Tsardom of Russia.17 Tsar, the title taken by the Russian king, accordingly derived from the Russian adaptation of the Roman title “Caesar.”

It is from this point that Russian control of the Black Sea became a core component of Russian policy in the area. The importance of this control though was not given to the Black Sea per se, but instead to the access it provided to the wider Mediterranean world, and with it the holy sites of Christianity. This access was tied strongly to a psychological understanding of Russia not merely as a state but as a divinely sanctioned empire and heir to Rome. As an isolated continental power, domination of the Black Sea, therefore, meant direct access to the captured heart of Orthodoxy in Constantinople, the straits of Marmara, and, ultimately, the Holy Land in the Eastern Mediterranean. Accordingly, it became a fixture of Russian foreign policy for, as current events would indicate, the subsequent four centuries.

Imperial Period: The Third Rome Applied

“It is a Matter no longer to be doubted, that the attainment of the absolute sovereignty over the Black Sea is one of the motives whereby the Empress of Russia is induced to hostility against the Turks.”18 This article was written in 1783 just 7 years after American independence from Great Britain and 200 years after the creation of the tsardom of Russia. It was a British publication in an Oxford newspaper discussing the actions of Catherine the Great in Crimea. At the time, she was in the process of invading Ukraine on behalf of Russia. In this case, much as in the Russian attack on Ukraine in 2014, the strategic objective was the Crimean Peninsula. In Catherine’s time, the proximate goal of its annexation was the creation of a potent Russian Navy with warm water ports capable of projecting power outside of Russia’s continental position in Eurasia. Ultimately, the goals of the invasion were the use of the naval bases of Crimea to reconquer Constantinople and the Turkish Straits from the Ottoman Empire. Known as “The Greek Project,” Catherine the Great advocated for the partition of the Ottoman Empire and the restoration of the Eastern Roman Empire under Moscow.19 This would have opened the Eastern Mediterranean and Africa to Russian power projection and potential exploitation. Such a project fundamentally rested on the complete domination of the Black Sea by Russia.

During the nineteenth century, Russia pushed this strategy even further. In its self-proclaimed role as protector of Eastern Christians, Western powers viewed the decline of the Ottoman Empire in that century with increasing alarm. Both Russia and France declared themselves as rightful protectors of the Holy Land in Palestine and the Levant, each holding imperial designs on the decaying Ottomans. In keeping with the fundamental strategic importance of the Black Sea as Russia’s only window to project power in the Eastern Mediterranean, Russia found itself in open conflict with Britain, France, and the Ottoman Empire in the Crimean War, which it lost.20 This put a halt to Russian hopes of expanding into the Ottoman Empire for the remainder of the nineteenth century. However, even as recently as the twentieth century, the last Russian tsar, Nicholas II, was still following a similar policy tied to Third Rome thinking. During the First World War, the Russian Empire wished to annex Istanbul in the final partition of the Ottoman Empire, restoring the ancient seat of Orthodox Christianity. This desire was so advanced that it was formalized in a secret agreement known as the Constantinople Agreement signed during the war. In this text, the Allies agreed to give the Russian Empire Constantinople and other Turkish lands in the event of victory.21 Of course, these plans, in addition to the tsardom of Russian itself, came to an abrupt halt following the Russian Revolution and the subsequent creation of the Soviet Union.

Cold War: A Frozen Balance of Power

The Communist and officially atheist Soviet state and the Cold War in which it found itself changed the language by which Russia spoke of the Black Sea. There was a marked shift away from such lofty historical justifications toward a cleaner and more modern logic tied to the balance of power. Most observers accordingly did not deem the previously mentioned historical concepts particularly relevant, though it is important to note that the concept still was discussed in academic circles on Soviet studies.22

During the Cold War, a favorable balance of power for the Soviets was reached following a brief scare in 1946 during the Turkish Straits crises. In this crisis, Joseph Stalin demanded Turkey allow Soviet ships to pass through the Turkish Straits, threatening war if the Turks refused.23 Turkey acquiesced, allowing Soviet ships to pass. Just some years afterward, however, it joined the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) alliance to guarantee its territorial integrity and to avoid being strong-armed by the Soviets in the future.24 Regardless of this highly risky event, throughout the Cold War Turkey continued to control the southern coast of the Black Sea and the Turkish Straits as it had for six centuries. The Soviet Union and its satellite states controlled quite literally the rest of the coast. This meant, fundamentally, that there were only two actors deciding strategic policy in the region. By virtue of the collapse of the Ottoman Empire and Turkey’s reduced military relevance, the United States became the de facto alternative actor opposite the Soviet Union. The Soviet Union maintained an acceptable level of naval supremacy in the area and had access to the Eastern Mediterranean, a situation that resulted in relative stability in the theater throughout the Cold War. Through control of the Black Sea, the Soviet Union also had access to the rest of the world during this period from its south. To illustrate just how pivotal this control was to Soviet global power projection, the missiles the Soviets shipped to Cuba that precipitated the Cuban missile crisis were loaded onto ships in Crimea. They were then shipped through the Black Sea all the way to Cuba and, at least temporarily, allowed the Soviet Union to directly menace the U.S. heartland with medium-range nuclear weapons.25 Given the nuclear reality of that period, this meant that the potential for a localized conflict in the Black Sea was lower by virtue of mutually assured destruction. This balance was a stable one and the region saw no hot conflicts during the Cold War period. The bipolar nature of the conflict meant that unlike today, there was simply far less room to maneuver in the Black Sea or elsewhere.

Map 1. Map showing national alignment during the Cold War, 1987

Source: courtesy of the author, adapted by MCUP.

The Present: A Return to an Imperial Mindset

With the fall of the Soviet Union and the end of the Cold War, the stable balance of power given by the bipolar world in the Black Sea was shattered. Where previously two actors determined the strategic situation in the region, there were now six outright state actors. Russia kept a coastline on the Black Sea, but no longer dominated the region by any means.26 Thirty years following the end of the Cold War, the world has observed the evolution of an unstable balance of power, punctuated by multiple continuing armed conflicts. To further add fuel to this flame, Putin and Russia in the post-Soviet period have also seemingly returned to the use of lofty imperial imagery and notions in their creation of modern Russian statehood. When discussing his current invasion of Ukraine, Putin directly compared himself to Peter the Great, stating, “Peter the Great waged the Great Northern War for 21 years. It would seem that when he was at war with Sweden, he took something from them. He did not take anything from them, he simply returned what was Russia’s.”27 He made these comments while discussing the annexation of Ukrainian territory along the Black Sea. This combination of power imbalances paired with historically rooted revanchism has resulted in a series of conflicts since his accession to power 22 years ago. A key factor that is often underobserved in these conflicts is that each has enhanced Russia’s physical position and control of the Black Sea as the following two figures indicate.

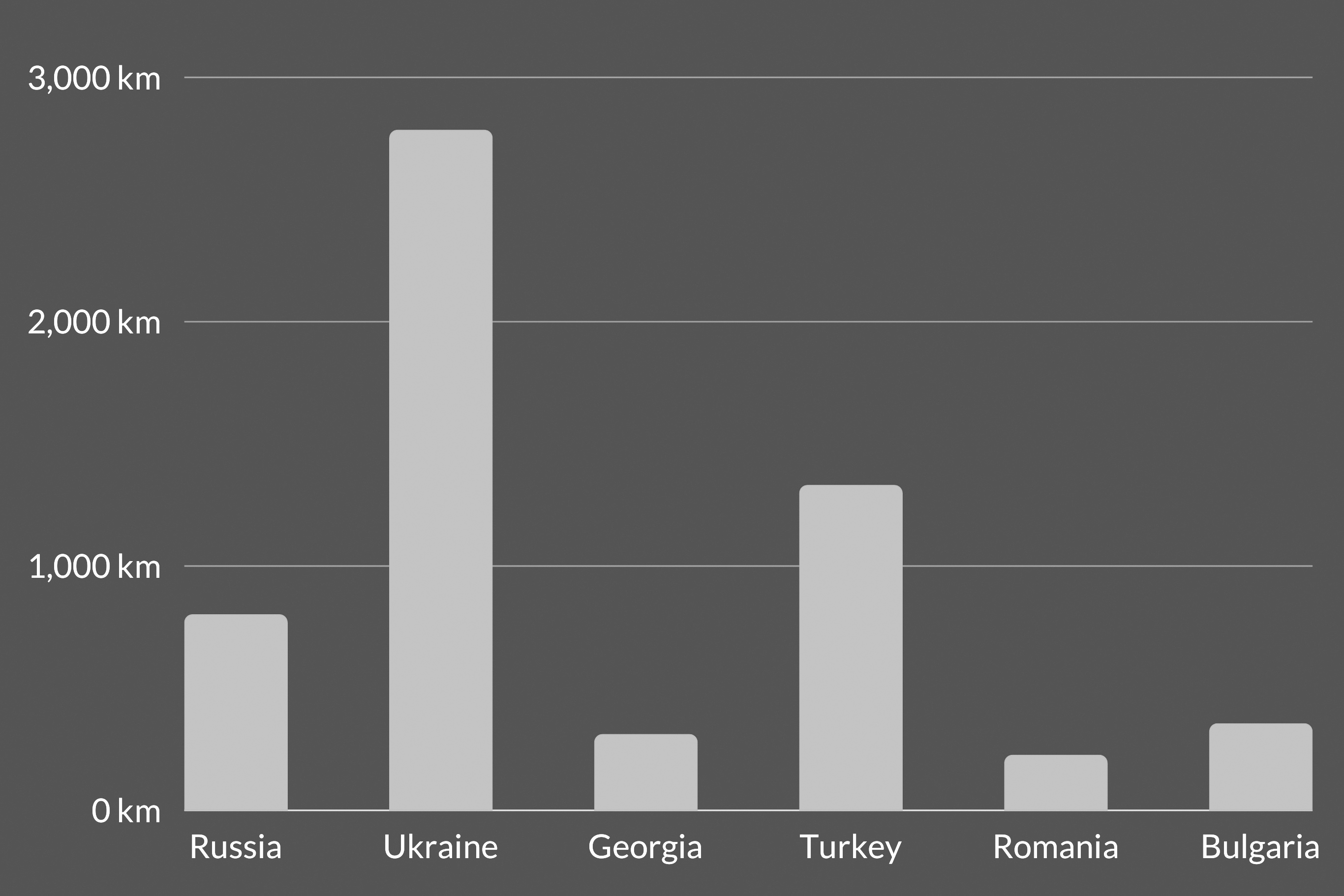

Figure 1. Share of the Black Sea coastline, 2000

Source: data compiled by the author, adapted by MCUP.

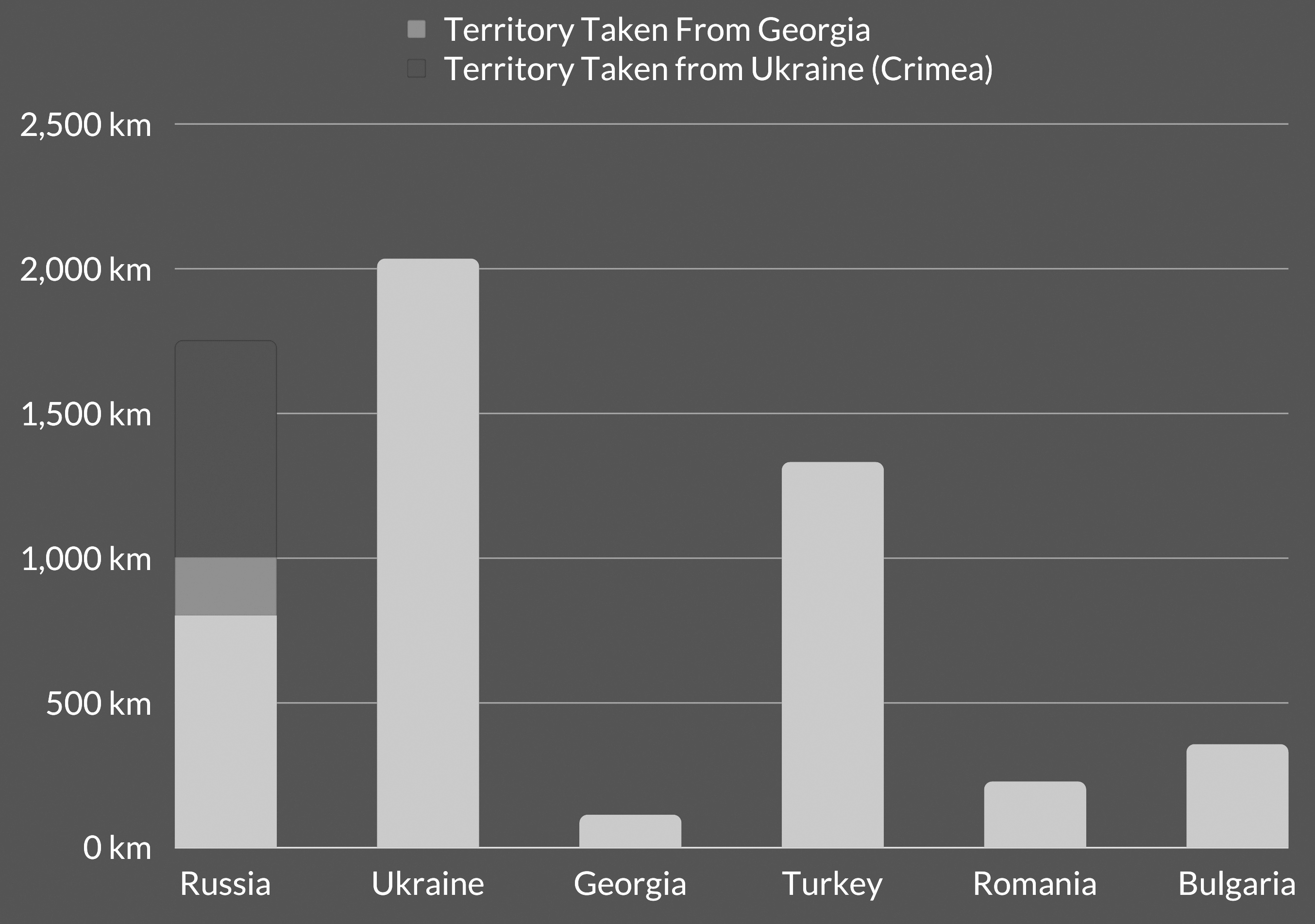

Figure 2. Control of the Black Sea coastline following attack on Georgia and annexation of Crimea

Source: data compiled by the author, adapted by MCUP.

Taken together, it is not difficult to observe that Russia has been astonishingly successful at taking Black Sea coastline in a relatively short period of time as the above charts indicate. It is also important to note that the final 750 km of coastline as indicated in dark gray on the second figure is also the most important section of coastline, at least in part, strategically in the Black Sea. It represents the Crimean Peninsula, which offers the nation that controls it enormous advantages for naval deployments and power projection throughout the theater.28 It also satisfies the previously mentioned historical desires of Putin to reconquer the root of Russian identity and faith. The peninsula juts out into the middle of the sea, giving excellent positions for the deployment of missile batteries and the docking of ships. As the current invasion stands in Ukraine, Russia also appears set to further expand this advantage in any final settlement. The final portion of this section will now shift to discussing the ongoing invasion and its potential effects on the situation in the Black Sea in more detail.

The Ukraine Invasion of 2022

With the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine proper, it is not clear how much more Black Sea coastline Russia is looking to take. However, its previously mentioned willingness to sustain and inflict enormous casualties in battles for coastal cities such as Mariupol and its insistence on consolidating regions along the Black Sea coast suggest this war is yet another Russian attempt to control the Black Sea. Unsanctioned comments by Russian generals outright stated that the objective of the war was the occupation of southern Ukraine.29 Such annexation would give Russia a land bridge not only to Crimea but potentially also allow Russia to access the breakaway Moldovan province of Transnistria, where Russian troops are currently based. It would also further reinforce Putin’s historical credentials as a leader in the company of the likes of Peter or Catherine, who each successfully brought these areas into the Russian state.

Notwithstanding Russia’s lackluster military performance, it is likely that more of southern Ukraine will come under the control of Russia or states loyal to it when the war is over. As the months drag on, Russia has made agonizingly costly yet consistent advances in the regions along the coast of Ukraine and in the east, having abandoned its assault on the north of the country. If one understands the conflict in terms of a consistent effort to conquer more Black Sea territory for both practical and historical reasons, the following figure would suggest why such a strategy is logical for Russia.

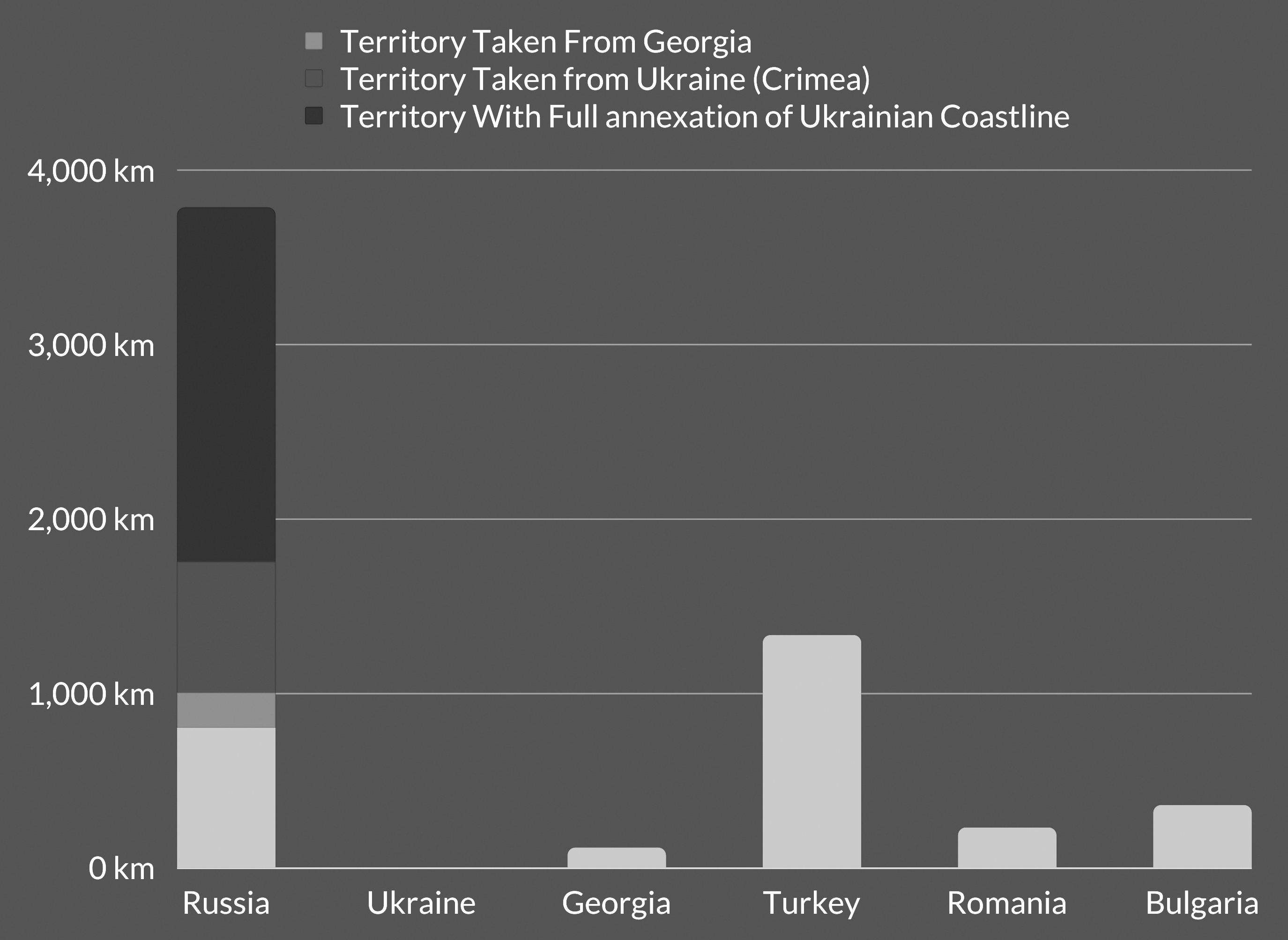

Figure 3. Potential postwar settlement involving annexation of Ukraine’s coastline

Source: data compiled by the author, adapted by MCUP.

Though completely landlocking Ukraine would be an incredibly bold step, it is not one that is out of the realm of possibility. In such an event, Russia would then have substantially more direct control of the Black Sea proper than even Turkey. Even were it to allow Ukraine a nominal portion of its coastal territory in a final settlement, Russia is poised to become the dominant holder of Black Sea coastline in the region. It also shows in simple terms that, far from being part of irrational lapses of judgment with each of Russia’s series of invasions and military actions of the last 20 years, Russia has successfully gone from a somewhat average position on the Black Sea to a dominant one in a relatively short period of time. This has been done through a methodical series of attacks on its neighbors following clear, historically based strategic thinking.

Finally, it must be reiterated that the Black Sea’s true strategic value is not in its domination per se, but the access Russia gains to the Mediterranean and through that ultimately the rest of the globe. Just as it was in the past, the Black Sea is fundamental for powers on its shores to act as serious players outside of their continental boundaries if they wish to. Russian actions in Syria and increasingly in North Africa are likely part of this larger strategy and depend on sufficient control of the Black Sea to make such operations feasible as Russia attempts to reassert itself as a proper great power and seemingly reimmerses itself in the imperial thinking of its past.30

Valiant resistance from the Ukrainian people and human costs notwithstanding, Russia is currently in control of the bulk of the Ukrainian Black Sea coast. Given the sheer asymmetry that existed militarily between Russian and Ukrainian armed forces, in addition to Russia’s annexing of strategically important Crimea, it has been something of a surprise Ukraine has resisted so firmly. Regardless, Russia has successfully launched a naval invasion near Mariupol, and after fierce resistance now occupies the city in its entirety.31 In addition, there is a fleet off the coast of Odessa that many analysts expect could be used to launch another naval invasion in the western part of the country if deemed necessary.32 Russia also has maintained a full blockade of Ukrainian ports for the duration of the war, a choice that has had a profound global impact on the global food supply.33 Though Russia has retreated from the Ukrainian capital and second city, the possibility for another offensive in the area is likely placing enormous pressure on Ukraine to focus on defending them at the expense of the south. Russia’s superiority in the sea and air (even if its use of its air advantage has been bafflingly subpar at best) has provided it with relative success in the south of the country.34

Though it is always risky to predict the future, this article will go with the working assumption that the final settlement in Ukraine will be in Russia’s favor, at a minimum allowing it to maintain control of the territory it currently occupies. It does so from a simple balance of power calculus and in recognition of the fact that Russia already exerts control over much of the territory strategically relevant to naval issues in the Black Sea. This would include Ukrainian naval facilities and naval manufacturing capacities, which are not negligible, particularly when paired with Russian technical capacity and military objectives.

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine will likely result in Russia acquiring a substantial and currently underutilized shipbuilding capacity in Ukraine.35 There are 10 shipbuilding and repair yards in Ukraine that Russia could potentially gain control of in the event of annexation or subjugation of Ukraine. For comparison, Russia currently only maintains six shipyards and repair facilities in its internationally recognized southern territory plus Crimea.36 Three of these were gained in the annexation of Crimea. This would mean that Russia theoretically would have the ability to double its shipbuilding capacity in its southern region if it is victorious against Ukraine. Therefore, it might further develop the captured facilities and capacities of Ukraine. This is a substantial prospect to be considered when one looks at the future trajectory of Russia’s naval capacities in the region and highlights the importance of challenging Russia’s ability to consolidate control over Ukraine as a result of this invasion.37 Already in Kherson by mid-June 2022, there are reports that Russia is doing just this and beginning to use the Kherson shipyards for the production and maintenance of Russia’s Black Sea Fleet.38 In Kherson alone, there are three of these previously mentioned shipyards.

Summary

In summation, there are profoundly important practical and ideational motivations behind Russia’s interest in the Black Sea. Accordingly, a common Black Sea thread can be seen weaving its way through Russian acts of aggression under Putin going back at least to Russia’s war in Georgia in 2008. Motivated by both, Russia has physically annexed territory along its coast in all of its recent acts of aggression against its neighbors. As the invasion of Ukraine of 2022 shifts to the south and east, it would seem Russia’s most recent actions are no exception to this pattern of behavior and will likely result in Russia again expanding its power in the theater.

Part 2: U.S. Interests and Recommendations

All evidence previously cited suggest that Russia is acting to further expand its control in the Black Sea, even at substantial political and material cost. This presents the United States with something of a predicament. By most measures, the United States does not maintain direct strategic interests in the Black Sea. Regardless, its NATO allies in Turkey, Romania, and Bulgaria do. Accordingly, the United States must find a way to navigate this reality in response to the changing security environment of the Russian-Ukraine war theater. However, it is not useful to focus on the region without considering U.S. strategy in Europe as a whole. The Black Sea represents a space where the United States can and should seriously consider delegating responsibility for the region to competent allies as part of a larger European strategy to contain Russia. This is in no small part because any U.S. interests in the Black Sea derive directly from those of these allies themselves. Accordingly, the following discussion outlines broad U.S. interests and offers both a short- and a long-term solution to Russian aggression in the Black Sea. These are designed to satisfy as best as possible what are understood here to be the two broad camps in the currently quite vibrant and contentious U.S. foreign policy discourse. For the purposes here these are divided simply between those who would advocate an increased role of the United States in global security affairs versus those who suggest a less heavy U.S. security footprint in regions such as the Black Sea, though it is recognized there are a plethora of variations in U.S. foreign policy perspectives.

U.S. Interests and an Evolving Public Discourse

They say, “Trump said Putin’s smart.” I mean, he’s taking over a country for two dollars’ worth of sanctions. . . . “I’d say that’s pretty smart. He’s taking over a country—really a vast, vast location, a great piece of land with a lot of people, and just walking right in.”39

This is a quotation from former President Donald J. Trump in February 2022, shortly after the invasion of Ukraine began. This stands in contrast to the official statement by President Joseph R. Biden 10 days before:

The prayers of the entire world are with the people of Ukraine tonight as they suffer an unprovoked and unjustified attack by Russian military forces. President Putin has chosen a premeditated war that will bring a catastrophic loss of life and human suffering. Russia alone is responsible for the death and destruction this attack will bring, and the United States and its Allies and partners will respond in a united and decisive way. The world will hold Russia accountable.40

The disconnect between the two de facto leaders of America’s political parties highlights the previously mentioned gulf between political camps as to how issues such as Russian expansionism in the Black Sea ought to be dealt with. Though it is still too early to start speculating as to what the next presidential election holds, former President Trump is a serious contender for the next Republican nominee for president.41 Though the Republican Party has notable internal differences when it comes to NATO and foreign policy more generally, the simple reality is that what constitutes “U.S. interests” is no longer nearly as standardized as it was even a decade ago, with a substantial element of the Republican Party advocating for a more transactional form of American foreign policy. Challenges on the more progressive wing of the left also advocate for fundamental changes in U.S. foreign policy, holding a far more skeptical view toward U.S. participation in global security commitments. Foreign policy has therefore proved to be susceptible to recent trends of political polarization along party lines in the United States.42 In addition to positions on Putin personally and his actions, a substantial wing of the Republican Party also has openly questioned the utility of NATO, including former President Trump on multiple occasions.43 The concept of international cooperation more broadly has also been substantially criticized, embodied perhaps most clearly by the United States exiting the World Health Organization during the COVID-19 pandemic.44 This challenge has also come from the more progressive wing of the American left, with former Democratic candidate Bernie Sanders strongly opposing U.S. participation in international trade agreements.45 The progressive wing of the Democratic Party is also generally skeptical of U.S. military interventions and its role as a global security provider. Even a president expected to be a consummate foreign policy traditionalist in President Biden decided to respect President Trump’s agreement to withdraw U.S. troops from Afghanistan. Despite claiming to embody the more traditional American commitment to international cooperation with its allies, the president chose to do this unilaterally with minimal consultation of international allies ending abruptly 20 years of U.S. involvement in Afghanistan.46 This illustrates that even in what would be considered the traditional political establishment, clarity as to what constitutes “U.S. interests” is in a state of flux on both sides of the political aisle.

This piece does not look at all to offer a normative assessment of these positions but instead tries to present what it considers to be objective interests for the United States regardless of political orientation. Accordingly, it rests on the following assumptions:

A stable security situation in Europe is of interest to the United States, with or without a substantial U.S. presence. If the United States wishes to scale back its security commitments, it needs to do so in a way that limits disruption to global peace and stability. The main international relations challenge for the United States in this century will be in how it manages the rise of China, not how it responds to a declining Russia.

Interests

With these assumptions, the consolidated interests are as follows.

Peace on the European Continent

As the invasion of Ukraine has shown, Russia is more than willing to violate the territorial integrity of neighboring states if it deems this is in its interests. Regardless of one’s perspective on U.S. foreign policy, it is generally accepted that peace on the European continent is in the interests of the United States. Destructive war in Europe drug the United States into brutal conflicts twice in the twentieth century. In current times, the risks entailed by the use of weapons of mass destruction raise the risks of war between great powers to existential levels. In Europe’s east, there are borders that are subject to contestation along the same lines as those in Ukraine. Most alarmingly, these include the Baltic states, NATO members who were also a part of the Soviet Union. Therefore, regardless of whether one finds themselves in the more traditional or more reformist camp on U.S. policy, it can be agreed that peace in Europe is a net benefit to the United States.

Free Hands to Shift Attention to Asia

Despite peace on the continent being important to the United States, to put it bluntly and simply, Europe’s importance to American foreign policy simply is not what it once was. Regardless of Russia’s attempt to destabilize the security environment in Europe, the fact is that the United States faces a rising superpower, China, in Asia and a continuously declining rival in Russia.47 Though it is likely to remain a persistent military rival and relevant regional power, Russia’s staggeringly poor military performance in Ukraine thus far reinforces the state of decline of Russia as a credible rival to the United States on a global scale.

Though the United States maintains regional interests in Europe, it cannot be forgotten that the United States’ primary objective navally and otherwise ought to be contesting the rise of the genuine superpower in China and the Pacific. The bulk of present and future industrial output, general economic growth, and future population lies in Asia.48 Europe, though of course still important strategically and economically, simply is not projected to be of primary strategic importance to the United States in the coming decades as it has been in decades past. If anything, it is projected to relatively decline more starkly than the United States when it comes to the new distribution of power if it remains in its current institutional form.49 By contrast, it is also well documented that China is set to be a competitive superpower in coming years. Accordingly, it has begun to flex its new muscles with persistent regularity. To effectively counter Chinese aggression, the United States is going to need the bulk of its naval forces, attention, and strategy making focused on the Pacific if it wishes to provide a credible deterrent to China in the future. As it stands, the Pacific fleet would have a difficult time fighting China in its home waters and preventing a Chinese takeover of Taiwan, for example, according to some analysts.50 In the future, this difficulty is set to only increase as China expands its naval capacities. Whether one wishes for a more or less involved United States in global security issues, the United States will be a Pacific power regardless of one’s political persuasion. From the state of Hawaii to the territories of Guam and American Samoa, the United States has borders near China. This, therefore, means the United States does not have the luxury to delegate responsibility for peace in the region to the same extent that it could in Europe to deal with a Russia bent on domination in the Black Sea.

Recommendations

Short-Term Solution: Increased NATO Priority to the Black Sea

The North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) is of course still the core of the U.S. security apparatus in Europe and the Black Sea. For now, U.S. policy making simply must continue to function within the bounds of NATO to maintain peace on the European continent in the face of Russian aggression. In recent years, NATO has lowered its priority in the Black Sea. In the moment Russia invaded Ukraine in 2022, there were no NATO vessels in the Black Sea at all.51 This has been explained primarily because of disagreements among NATO members, in particular Turkey, which has attempted to not provoke Russia by patrolling the area with its own fleets. This situation is simply not a sustainable one so long as Russia continues to attack its neighbors in the theater, destabilizing the security situation in Europe. Accordingly, the United States and NATO ought to respond.

Ideal Solution: Set up a Permanent NATO Black Sea Patrol Mission

This piece echoes a slightly modified but simple recommendation to improve deterrence in the Black Sea provided by the Center for European Policy Analysis.52 A full-time NATO patrol mission, based in either Romania, Bulgaria, or Turkey ought to be present in the Black Sea at all times. If there is any lesson to be garnered from Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, it is that preventing provocation by avoiding the Black Sea has not been successful in countering Russian ambitions in the area.

Though it is a simple solution to propose, it must be noted that Turkey can provide a substantial stumbling block to such a strategy. Even as early as 2016, Turkey’s position on Russia has given NATO strategists persistent and well-

justified concern. 53 Though the short-term solution is simple on its surface, Turkey’s willingness to threaten vetoes of Finland and Sweden’s accession to NATO have shown that Turkey’s reliability as a NATO partner is likely to be dubious at best when countering Russian aggression. What this means in practice is that the best solution for the United States, increasing NATO’s presence in the Black Sea, is one that seems all but doomed to failure. Without Turkey as a reliable ally, NATO and the United States’ ability to counter Russia in the Black Sea through such a patrol is substantially limited. Ultimately, so long as Turkey remains committed to healthy relations with Moscow, NATO-based solutions will be subject to a Turkish veto when it comes to actions in the Black Sea.

Long-Term Solution: Supporting European Strategic Autonomy

The longer-term solution could potentially fill in the gaps where NATO’s weaknesses have become clear. In addition, it also offers a rare area where more interventionist and more isolationist advocates of U.S. foreign policy can find some common ground. With an empowered and allied European Union, the United States may be able to avoid the Turkish spoiler found in NATO without having to substantially increase its presence in the area. European fleets, sailing under a European flag, would at least theoretically constitute a riparian state under the terms of the Montreux Convention governing the Turkish Straits. What this would mean is that, regardless of Turkey’s position, Europe as an actor would have the legal right to enter and remain in the sea. This would be because the European Union has two member states in Bulgaria and Romania, which have coastlines on the Black Sea. This would also mean they would be allowed to station fleets in the theater longer than the 21-day limit, which currently governs most NATO members.54

The Current State of the European Union as a Security Provider

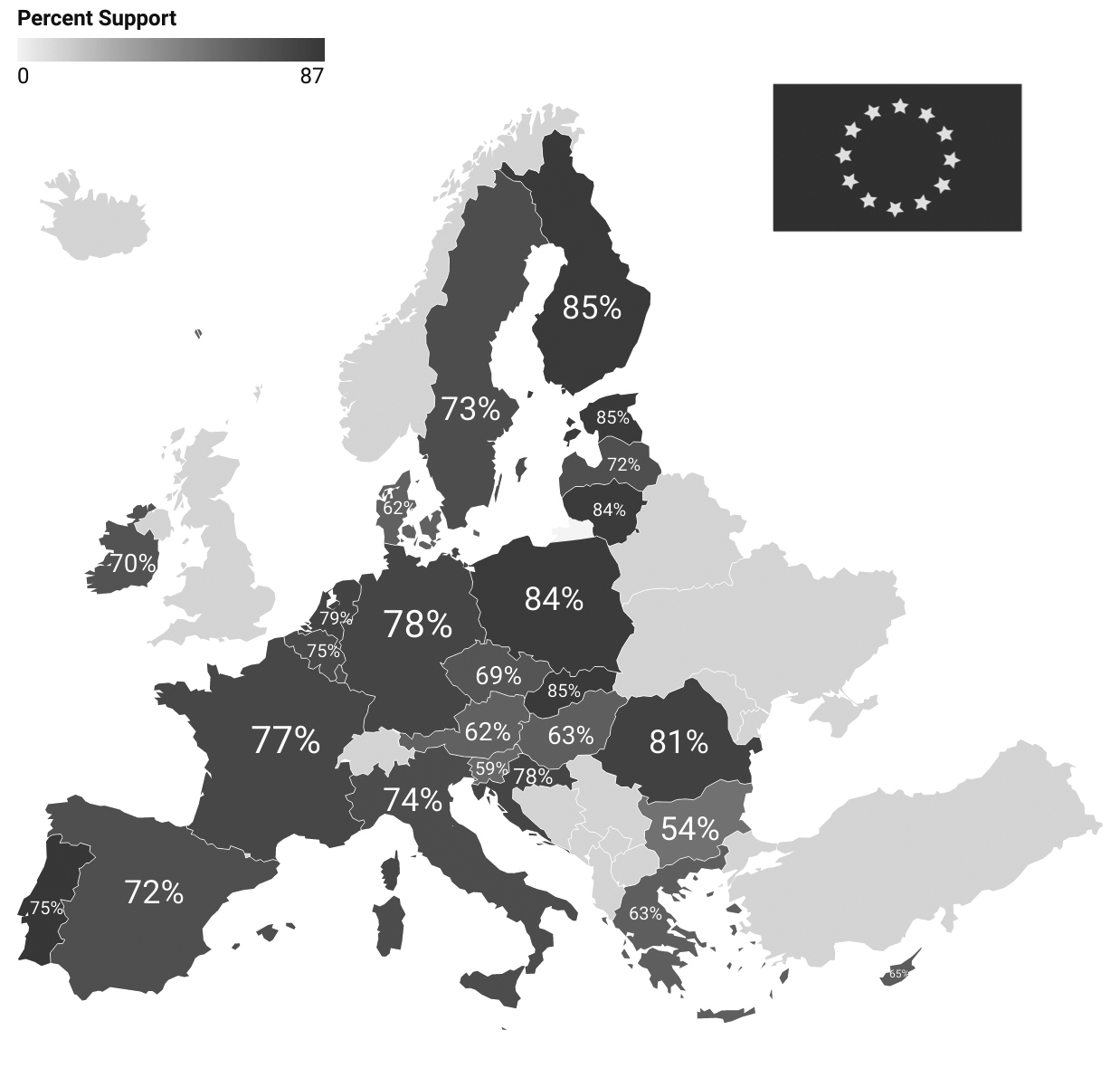

In 2017, 55 percent of Europeans stated they supported the creation of European army.55 This was the last poll done by Eurobarometer on the issue. However, subsequent polls would suggest support has only increased for such a proposal. A flash Eurobarometer poll in 2022 following the invasion of Ukraine showed a remarkable 75 percent of Europeans supported the open statement, “We need greater military cooperation within the EU,” though questions on a European army have not been asked by the pollster since 2017.56 Given just the exit of the UK, where only 39 percent supported such a prospect, it is likely that support for such a proposal has only increased since 2017.

Map 2. Support for a European Army in 2017

Note the support for Britain is not shown (39 percent).

Source: data compiled by the author, adapted by MCUP.

Regardless of whether this support for a different security arrangement in Europe implies support for an outright European army, what is clear is that support for change in the way security is managed in Europe constitutes nothing short of a political mandate. Despite this, it is important to remember the European Union (EU) does nothing quickly. Its incredibly bureaucratic nature also makes it difficult to pinpoint when and where political shifts occur for outside observers. This is not so much a bug but a feature of this distinct political institution. Regardless, it is now safe to say that the last seven years have witnessed a shift in the EU’s security ambitions and institutional landscape, one which has only accelerated because of Russian aggression in Ukraine.

Framed as “strategic autonomy” in EU discourse, the European Union and its key players have initiated transforming the EU from an exclusively economic and civilian institution to one which plays a genuine security function.57 The exit of the United Kingdom from the bloc, traditionally a veto player when it came to an increased security role of the EU, has opened the door for increased security integration driven by activist and Europhile governments in Emmanuel Macron’s France and Olaf Scholz’s Germany. Such grand initiatives tied to the European Union tend to be met with healthy skepticism in both English and American policy circles. However, recent recommendations by Chatham House have cautioned British policy makers in dismissing this new phenomenon as merely another chapter in Europe’s checkered history of security integration stating:

It would be premature for London to dismiss strategic autonomy because the key drivers of a greater European capacity for thinking and acting more autonomously on security and defense—above all the realization that the long-term commitment of the United States to European security is changing as Washington increasingly focuses on the Indo-Pacific, a diagnosis London largely shares—have not altered.58

The same warning holds for U.S. strategists. The change in rhetoric in the EU has also been backed up by policy changes. In 2015, Europe quietly created its first true uniformed service when it expanded Frontex’s mandate in response to the migration crises. Frontex stated on Twitter, speaking of the decision, “For the first time, the European Union has its own uniformed service—the European Border and Coast Guard standing corps.”59 Though modest, it does indeed represent the first armed, uniformed service under the control of the European Union. As it stands, Frontex’s mandate tasks it with protecting both the land and sea borders of the entire European Union. Its sea element would be comparable to the U.S. Coast Guard in its mission while its land element is more akin to U.S. Customs and Border Protection. On top of this, the creation of a European defense fund, the creation of the Permanent Structured Cooperation mechanism, and the development of a more robust European Foreign Service all are symptomatic of the increasing pace of this evolution. However, most importantly, in 2020 serious proposals for the creation of a European Rapid Response force to address global crises were taken up by the European Commission with support from the continent’s main military players. Now in March 2022, European leaders have officially agreed to set up such a force, starting out very small at just five thousand troops. Regardless of its small size, however, the institutional implications of this action are of course profound for security in Europe in the longer term.60

Though it is bureaucratic and slow-moving, the evolution of the EU in this direction is something that forward-thinking U.S. policy makers need to take seriously, though not necessarily with immediate concern. Naturally, the idea of Europe beginning to take responsibility for its own defense tends to raise alarm bells in many U.S. policy making circles as fundamentally eroding U.S. influence. On the contrary, this article advocates viewing it as a change worth supporting where possible as a cost-effective solution to the Russia problem. As it stands, the United States bears the brunt of the responsibility for the defense of Europe against Russian aggression, both militarily and politically. The current arrangement seems to have far more costs than benefits. A splintered Europe, even with the higher national defense spending states have promised, simply is not capable of seriously defending itself under its current institutional structure. European states are simply too small, with each announced spending increase being designed to defend individual states and not continent as a whole. Instead of weakening the U.S. position, a Europe that is self-sufficient militarily and economically presents the United States with a series of opportunities to ultimately strengthen the transatlantic alliance while at the same time allowing itself more space to focus on Asia and theaters where more critical interests are at stake. Max Bergmann even makes the case in Foreign Affairs that without substantial change, the transatlantic alliance’s fundamental integrity is at risk. In the event of the rise of a truly anti-transatlanticist administration in the United States, the lack of U.S. interest in defending Europe could quickly devolve into a situation of “every nation for itself” on issues of security in Europe if it maintains its current institutional structure. If the lessons of the World Wars of the twentieth century are any testament, this is clearly a geopolitical nightmare that even the most isolationist policy maker would wish to avoid. Critically as well, it is in Asia where a genuine superpower is rising as opposed to Europe where a collapsed one is desperately attempting to disrupt an established order with diminished resources. Managed properly, this shift toward increased European “strategic autonomy,” therefore, could offer a cost-effective and permanent solution to Russia’s disruptive actions.

Suggested U.S. Policy

A Naval Element in the European Rapid Response Force

As previously mentioned, the European Union has officially stated its intention to create a nascent armed force under European control. It is designed to be under the control of the European Union, not the member states, meaning the organization is on its way to formally being a military player. This force is set to be operational by 2025 with Germany providing the core personnel for the unit.61 The objective the United States ought to support would be, within the creation of such a force, the inclusion of a European naval structure with a fleet designated to challenge Russia in the Black Sea. As it stands, no such element is projected to be included. This could act as a permanent patrol group in the likely event that NATO cannot accomplish such an objective.

The ability for Europe to credibly counter Russia would be all but guaranteed if the development of such a force is taken seriously, even if Russia is able to assimilate the bulk of Ukraine’s shipbuilding capacity. This is in part due to Europe’s enormous shipbuilding capacity and technical abilities as a collective. In the European Union, there are 150 large shipyards. Forty of these are capable of making large seagoing commercial vessels.62 By contrast, Russia has 11 total shipyards, 3 of which are exclusively for repairs. Even if Russia were able to absorb the Ukrainian shipbuilding industry in its entirety, this would only bring its total shipyard count to 13, as the bulk of Ukraine’s shipyards have already been captured in the annexation of Crimea.63 Clearly, this is paltry in comparison to a more united Europe. The limits of such a force would be all but limited to solely the level of ambition taken at the European level. This new actor in Europe would have economic clout paired with a well-developed arms industry that Russia simply could not match. In addition, simple geographic proximity to the theaters would make this actor far better placed to keep the peace and counter Russia than the United States across the Atlantic. Europe’s previously mentioned riparian status on the Black Sea would also open their ability to participate in naval buildups in the sea using ports and facilities on its coast.

Though the legal details would likely have to be worked out given these European fleets’ peculiar supra-state status under the governing regime for the Turkish Straits, the ability to challenge Russia directly in the Black Sea would likely immediately change.64 Europe could deploy fleets through the straits at will as part of a naval rapid reaction force, so long as those fleets are based in the Black Sea in either Bulgaria or Romania, two European Union members who have Black Sea coastlines. Following the necessary construction of more extensive port facilities, the feasibility of Europe maintaining a Black Sea fleet substantially larger and more advanced than Russia, is something that would be more than achievable. The Black Sea would quickly cease to be a Russian lake and become a European one, allied to the United States yet not formally bound by the inefficiencies of the NATO framework.65

How to Get There: The Carrot, Not the Stick

Of course, as the creation of such a force is an internal issue that would need to be taken up by European member states, the United States’ role will have to be supplementary in such an endeavor. Such a shift also is not expected to be fast. However, the United States maintains a powerful position in discussions of security on the continent, which should not be underestimated. For 70 years, Western Europeans have depended on the United States almost entirely for their practical security while many Eastern Europeans dreamed of joining in that system. As a result, the United States maintains a very strong practical and ideational position in Europe, which allows it to alter discussions and calculations of not only European elites but average Europeans through its diplomatic actions and statements. Were the United States to make it clear that it would support the previously mentioned reforms, worries about the United States’ response to the creation of a new security entity alongside NATO would not necessarily evaporate, but it would certainly be far less potent than it has been in recent years. Over the last few decades, the United States has taken an unclear stance on the development of capacities such as those mentioned in this article, occasionally supporting them and at other times expressing alarm at the prospect of a genuine supra-national actor in Europe. Even in the last two American administrations, commitment to European security and the United States’ view on Europe’s role as a strategic actor have shifted enormously simply by a change in presidential administration. Regardless of political position, an EU with a naval capacity would be a useful deterrent to Russia’s destabilization efforts and would be a net benefit to U.S. interests. Europe consists of well-established democracies with shared values to the United States, not to mention a shared cultural and political history. As powers rise in other parts of the world that do not share these traits, the importance of reliable and powerful allies who share liberal conceptions of the world will only increase.

Openness and clarity with European allies, particularly highlighting the less than rosy reality that Asia will be of primary strategic importance in the next century, can go a long way in encouraging Europe to continue to accelerate on its path toward strategic autonomy. This will hopefully result in it taking increasingly ambitious decisions to counter Russian aggression both in the Black Sea and other theaters such as Libya and Syria, with U.S. support. Clear dialogue, not blindsiding actions such as the rapid withdrawal of Afghanistan without consultation, the undermining of European interests in the Pacific in favor of the now isolated British, or the outright hostile rhetoric employed by the previous administration regarding the EU is the path forward to gain a useful, reformed European partner aligned with broad U.S. interests. Uncooperative actions such as those previously mentioned will not likely stop security reform. Instead, they risk causing the reform to come primarily from a place of concern and mistrust as opposed to one of support and cooperation as proposed in this article. The objective of U.S. policy therefore should not be the creation of a geostrategically relevant Europe per se, but a capable Europe that is still a firm and cooperative ally with the United States. This requires a degree of acting in good faith, which has been perceived in Europe as missing in the previous two administrations.

Conclusions

The Black Sea’s importance to Russia is a pattern that can be traced back for more than one thousand years. In the last four centuries, an imperial logic tied to a Third Rome mentality has made the Black Sea even more fundamental to Russian policy makers and increased Russia’s willingness to use force in the area. Though the pattern seemingly paused during the Cold War, Russia’s most recent conflicts fit in with this longer historical trend and its new imperial understanding of itself. All its recent conflicts with its neighbors have resulted in Russia gaining more physical control over the Black Sea, and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine is likely to be yet another chapter in that story.

The United States should respond to this trend by broadly supporting Europe’s stated desire for strategic autonomy. The United States should do so by supporting the inclusion of a naval element to the European Rapid Response Force created by the European Union in March 2022. Because of its allied status and enormous latent naval force capacity, a reformed Europe with a credible military element could counter Russia in the Black Sea without the need for substantial fleet deployment increases on the part of the United States. Fundamentally, this would also allow for countering Russia with or without needing to worry about a Turkish veto in the NATO alliance. The best way to accomplish this is through open and honest diplomacy with Europe and the avoidance of further actions that undermine the United States’ perceived reliability as a partner.

Endnotes

- Peter Dickinson, “Putin’s Imperial War: Russia Unveils Plans to Annex Southern Ukraine,” Atlantic Council, 12 May 2022.

- Jen Kirby, “100 Days In, Russia’s War Is Now a Brutal Offensive in Eastern Ukraine,” Vox, 3 June 2022.

- “Azov Officer: Russian Forces Lost about 6,000 Troops in Mariupol,” Kyiv Independent, 14 May 2022.

- “Casualty Status,” U.S. Department of Defense, accessed 15 August 2022.

- “The Geostrategic Importance of the Black Sea Region: A Brief History,” Center for Strategic and International Studies, 2 February 2017.

- Moscow is 932 km from Mariupol on the Black Sea; Washington, DC, is roughly 1,200 km from the nearest coast of the Gulf of Mexico in Florida. Found using “Distance Calculator | Erasmus+,” Erasmus-Plus.ec.europa.eu, accessed 26 June 2022.

- Leo Goretti, “Putin’s Use and Abuse of History: Back to the 19th Century?,” IAI Istituto Affari Internazionali, 1 March 2022.

- Bohdan Vitvitsky, “Disarming Putin’s History Weapon,” Atlantic Council, 23 January 2022.

- Andrei Kolesnikov, “Putin Against History,” Foreign Affairs, 14 June 2022.

- Vladimir Putin, “Article by Vladimir Putin ‘on the Historical Unity of Russians and Ukrainians’,” Boris Yeltsin Presidential Library, accessed 15 August 2022.

- John P. LeDonne, “Geopolitics, Logistics, and Grain: Russia’s Ambitions in the Black Sea Basin, 1737–1834,” International History Review 28, no. 1 (March 2006): 1–41, https://doi.org/10.1080/07075332.2006.9641086; and Paul Stronski, “What Is Russia Doing in the Black Sea?,” Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, 20 May 2021.

- “Address by President of the Russian Federation,” Office of the President of Russia, 18 March 2014.

- Ihor Sevcenko, “The Christianization of Kievan Rus’,” Polish Review 5, no. 4 (Autumn 1960): 29–35.

- “Saints Cyril and Methodius: Christian Theologians,” Encyclopædia Britannica.

- John Paul II, “Slavorum apostoli,” Vatican, accessed 29 August 2022.

- Michael Bourdeaux, review of Holy Russia and Christian Europe. East and West in the Religious Ideology of Russia, by Wil van Den Bercken, trans. by John Bowden, Journal of Ecclesiastical History 51, no. 4 (2000): 771–818, https://doi.org/10.1017/S00 22046900325659.

- Robert Lee Wolff, “The Three Romes: The Migration of an Ideology and the Making of an Autocrat,” Daedalus 88, no. 2 (Spring 1959): 291–311.

- “Saturday’s Post,” Jackson’s Oxford Journal, 5 September 1783.

- Hugh Ragsdale, “Evaluating the Traditions of Russian Aggression: Catherine II and the Greek Project,” Slavonic and East European Review 66, no. 1 (January 1988): 91–117.

- Orlando Figes, The Crimean War: A History (New York: Picador, 2012).

- “Constantinople Agreement: World War I,” Encyclopedia Britannica, accessed 16 August 2022.

- Wolff, “The Three Romes,” 291–311.

- Jamil Hasanli, Stalin and the Turkish Crisis of the Cold War, 1945–1953 (Lanham, MD: Lexington Books, 2011).

- George G. McGhee, “Turkey Joins the West,” Foreign Affairs, July 1954.

- Iftikhar Gilani, “Analysis—Redux of 1962 Cuban Missile Crisis in Ukraine,” Anadolu Agency, 28 January 2022.

- Sergiu Selac, Alessandra Di Benedetto, and Alexandru Purcarus, “Militarization of the Black Sea and Eastern Mediterranean Theatres. A New Challenge to NATO,” Centro Studi Internazionali, January 2019.

- “Hailing Peter the Great, Putin Draws Parallel with Mission to ‘Return’ Russian Lands,” Reuters, 9 June 2022.

- Andrew Schwarz, “Crimea’s Strategic Value to Russia,” Post-Soviet Post (blog), Center for Strategic and International Studies, 18 March 2014.

- Andrew Roth, “Russian Commander Suggests Plan Is for Permanent Occupation of South Ukraine,” Guardian, 22 April 2022.

- Frederic Wehrey and Andrew S. Weiss, “Reassessing Russian Capabilities in the Levant and North Africa,” Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, 31 August 2021.

- Leo Sands, “Mariupol: Russia Declares Complete Victory at Azovstal Plant,” BBC News, 20 May 2022.

- H. I. Sutton, “Russian Navy Landing Ships Seen Approaching Ukrainian Coast Near Odessa,” Naval News, 15 March 2022.

- Kaamil Ahmed et al., “The Black Sea Blockade: Mapping the Impact of War in Ukraine on the World’s Food Supply—Interactive,” Guardian, 9 June 2022.

- “The Curious Case of Russia’s Missing Air Force,” Economist, 8 March 2022.

- As recently as 2020, Ukraine was posited to be using only 20–30 percent of its shipbuilding capacity. With Russian injections of know-how and capital, it is expected that this latent shipbuilding industry could increase substantially, particularly in the context of the building of new warships. Maryna Venneri, “The Significance of Ukraine’s Maritime Industry for the Black Sea, and Beyond,” Middle East Institute, 4 November 2020.

- “Worldwide Directory of Shipyards/Shipbuilders,” TrustedDocks, accessed 16 August 2022.

- “Worldwide Directory of Shipyards/Shipbuilders.”

- Michael Starr, “Russian Occupied Kherson to Build Warships for Russia—Report,” Jerusalem Post, 17 June 2022.

- Chris Cillizza, “Analysis: Donald Trump Calling Vladimir Putin a ‘Genius’ Was No Mistake,” CNN, 3 March 2022.

- “Statement by President Biden on Russia’s Unprovoked and Unjustified Attack on Ukraine,” White House, 24 February 2022.

- Dominick Mastrangelo, “Romney: Trump ‘Very Likely’ to Be 2024 Republican Nominee If He Runs Again,” Hill, 5 May 2022.

- Gordon M. Friedrichs and Jordan Tama, “Polarization and US Foreign Policy: Key Debates and New Findings,” International Politics (2022): https://doi.org/10.1057/s41311-022-00381-0.

- “The Latest: Trump Questions Value of NATO, Slams Germany,” AP News, 11 July 2021.

- “Trump Moves to Pull US out of WHO amid Pandemic,” BBC News, 7 July 2020.

- Christina Wilkie, “Biden and Sanders’ Fight over Trade Is a War for the Future of the Democratic Party,” CNBC, 10 March 2020.

- Anthony Zurcher, “Afghanistan: Joe Biden Defends US Pull-out as Taliban Claim Victory,” BBC News, 1 September 2021.

- Cyrielle Cabot, “Population Decline in Russia: ‘Putin Has No Choice but to Win’ in Ukraine,” France 24, 24 May 2022.

- This interview gives a good general overview of reasons why Asia’s relevance will continue to increase in the following decades: Parag Khanna, “Why the Future Is Asian,” interview, McKinsey, 24 May 2019.

- Arnau Guardia, “Europe on the Wane,” Politico, 26 December 2019.

- Oriana Skylar Mastro, “The Taiwan Temptation: Why Beijing Might Resort to Force,” Foreign Affairs, 3 June 2021.

- John Irish, Robin Emmott, and Jonathan Saul, “NATO Leaves Black Sea Exposed as Russia Invades Ukraine,” Reuters, 24 February 2022.

- Laura Speranza and Ben Hodges, “10 Ways to Boost NATO’s Black Sea Defenses,” Cepa.org, 5 April 2022.

- Steven A. Cook, “Turkey Is No Longer a Reliable Ally,” Council on Foreign Relations, 12 August 2016.

- “Implementation of the Montreux Convention,” Republic of Turkey Ministry of Foreign Affairs, accessed 15 August 2022.

- Niall McCarthy, “Where Support Is Highest for an EU Army,” Statista, 24 January 2019.

- “Eurobarometer: Europeans Approve EU’s Response to the War in Ukraine,” press release, European Commission, 5 May 2022.

- Nathalie Tocci, European Strategic Autonomy: What It Is, Why We Need It, How to Achieve It (Rome, Italy: Istituto Affari Internazionali, 2021).

- Alice Billon-Galland, Hans Kundnai, and Richard G. Whitman, “The UK Must Not Dismiss European ‘Strategic Autonomy’,” Chatham House, 2 February 2022.

- “Frontex,” Twitter, 11 January 2021.

- “EU to Establish Rapid Reaction Force with up to 5,000 Troops,” Reuters, 21 March 2022.

- “EU Approves Security Policy for Rapid Reaction Force,” DW, 21 March 2022.

- “Shipbuilding Sector,” European Commission, accessed 29 August 2022.

- “All shipyards, Shipbuilders & Docks in Ukraine,” trusteddocks.com, accessed 29 August 2022.

- In this scenario, it is not clear if Europe would constitute a state or an international organization. It would be an unprecedented political entity that would then imply the need for legal interpretation of the convention.

- “EU to Establish Rapid Reaction Force with up to 5,000 Troops.”