Major Evan Phillips, USMC

https://doi.org/10.21140/mcuj.20221302003

PRINTER FRIENDLY PDF

EPUB

AUDIOBOOK

Abstract: The Andaman and Nicobar Islands (ANI) are some of the most neglected maritime terrain in the world despite their proximity to one of the busiest maritime chokepoints on Earth. Strategic competition in the Bay of Bengal and around the Strait of Malacca necessitates that U.S. strategy carefully considers the implications of having a U.S. presence on the ANI. The United States has the capacity to assist in international law enforcement of illegal, unreported, unregulated (IUU) fishing and piracy as well as ensure the security of international shipping through the Strait of Malacca. The possibility of bilateral exercises that introduce concepts such as expeditionary advanced base operations (EABO) and the use of the U.S. Coast Guard in multiple capacities are real possibilities as well. Perhaps most importantly, the United States can partner with India to leverage China’s Malacca Dilemma and constantly threaten a blockade of Chinese shipping through the Strait of Malacca in a potential conflict. China also aspires to alleviate its Malacca Dilemma.

Keywords: Andaman and Nicobar Islands, ANI, Andaman and Nicobar Islands Command, strategic competition, Quadrilateral Security Dialogue, QSD, Quad, Quad plus, ASEAN, Hindu nationalism, Strait of Malacca

Historical Context and Introduction

Understanding the complexities of the ANI begins with their history. The ANI had been home to indigenous people called the Andamese, which inhabited the islands as much as 30,000 years ago.1 There are still tribes on the island that are considered isolated, including the Shompen People who may be one of the last purely isolated tribes in the world.2 The islands lie in close maritime proximity to Myanmar, Thailand, and the mouth of the Strait of Malacca. Of the 573 islands that make up the territory, only 38 are inhabited. Besides fishing, the islands have abundant natural resources, with some of the most lucrative being rubber and red oil as well as a wide variety of crops. Forest covers the majority of the islands, and the central administrative center is Port Blair. Advancements in naval technology and navigation have yet to fully take advantage of the ANI maritime strategic potential. However, once the islands were populated with nonindigenous peoples from aspiring empires, the importance of the islands as essential regional maritime terrain would not be forgotten.3

The first significant ruling authority over the islands was the Chola Empire, which existed from 300 BCE to 1279 ACE, making it one of the world’s longest surviving empires.4 One of the most significant rulers of the Chola Empire was Rajendra Chola I or Rajendra the Great, who reigned from 1014 to 1044 ACE.5 Rajendra Chola I may have been the first to understand the ANI maritime importance. Due to the advancements in naval shipping and navigation and the emerging concept of globalization and internationalization, an advanced naval base was established on the ANI by the Chola Empire. This base’s primary purpose was to serve as a strategic launch point for further expeditions. However, this also set the stage for future military uses of the islands and the prospect that the islands could be of great benefit in controlling major trade routes near the region’s significant chokepoints and essential trade routes in the Indian and Pacific oceans. While the Chola Empire may have been the first to use the islands to expand their empire, they would not be the last. The Maratha Empire established an advanced naval base on the islands within the next hundred years before European colonial powers would overthrow them.6

The importance of global trade routes would be of significant concern to future empires as the art of empire building became perfected. Several empires attempted to maximize the use of the ANI. The British and the Dutch recognized the importance of the ANI as they colonized around the world. The Dutch were the first European nation to establish a colony on the ANI. In 1755, the Dutch East India Company officially made the ANI a settlement and renamed it New Denmark.7 However, the Danes would abandon the islands due to disease several years later. The problem of malaria pandemics would be a common theme for European colonists during the early European colonialization period. Austria would claim the islands that were thought to be abandoned by the Dutch and rename them the Theresa Islands. However, after a minor colony was established, like the Dutch, the Austrians would leave the islands in 1784.8

The next empire to establish a colony on the islands were the British who would initially establish a penal colony in 1789, but the British abandoned the colony in 1796 due to an outbreak of disease; they returned nearly 60 years later to establish a penal colony on the islands again and make a permanent settlement at what is now present-day Port Blair. During European colonial powers’ continuous reclaiming of the ANI, the Dutch still had a sovereign claim. The rights to the islands were initially sold in 1868, and the ANI officially became part of the British Empire belonging to British India.9 The British would retain the islands for the better part of the next century. However, as the British Empire declined, so did its holdings worldwide.

World War II (WWII) would have powerful influences on the ANI. The rapid decline of the once-mighty British Empire, along with the swift rise and fall of the Japanese Empire during the early 1940s, left the future of the ANI in question. However, India’s independence from British rule in 1947 determined that the ANI were formally part of India instead of the British Empire. The British recognized how vital the islands were and attempted to establish a sovereign puppet state made of Anglo Indians and Anglo Myanmar peoples before their departure from the Indian subcontinent. This last-ditch effort to colonize was fruitless, and the islands remained a part of India until the present day.10

The Strait of Malacca looms large in a discussion of global geopolitics and commerce. All observers recognize the importance of the three littoral states: Indonesia, Malaysia, and Singapore. Far too few have noticed that India is effectively a fourth littoral state because it controls the ANI. Located some 1,078 kilometers northwest of the western exit from the strait, the ANI gives India the capability to control Strait of Malacca traffic. If the United States can take advantage of its developing strategic partnership with India and the use of the ANI, it would gain significant leverage in the continuing strategic competition with China. Surprisingly, no state in the modern era has taken advantage of the ANI’s geopolitical position. The islands are part of Indian sovereign territory but would be most valuable in the context of a broad coalition in defense of the maritime commons. The intensifying strategic competition in the Indo-Pacific will draw the attention of all parties to the archipelagoes. Whoever holds the ANI can effectively control access to the Strait of Malacca and gain a significant advantage in any future maritime conflict. To that end, the United States must find a way to leverage the strategic benefits of the islands to counter a rising Chinese maritime threat. Leveraging strategic benefits can be accomplished by engaging in bilateral security and diplomatic efforts that also foster increased U.S. and Indian military cooperation. The mere perception of cooperation between India and the United States can itself be a powerful strategic deterrent to potential adversaries such as China. The world may never know a purely regional conflict again due to advancements in technology, global mutual economic dependence, and ultra-globalization. These concepts have created constantly changing diplomatic, informational, military, and economic variables. Strategic competitors have begun to develop and institute revolutionary new ideas to adapt to these changes, such as EABO, sea basing, as well as ways and means to project power and influence the global maritime commons while using new domains of war including cyber and space. These perceived adaptations are a result of a changed character of war necessitating changes in the way nations conduct future warfare and highlight the continued importance of strategic maritime terrain such as the ANI, regardless of its location on the globe.

The strategic weight of the ANI adds significantly to the importance of the U.S. strategic partnership with India. The United States must overcome political obstacles that hinder its relations with India. Despite considerable improvement since the Cold War era, the relationship between the United States and India remains complex and challenging. The Hindu nationalist ideology of the Bharatiya Janata Party, which has dominated Indian politics since 2014, clashes with the U.S. concept of democracy. Such a division might hinder security cooperation, especially if the U.S. public becomes strongly opposed to Hindu nationalism, although there have never been any indications of that occurring. A more significant obstacle is India’s firm stance on not becoming part of an alliance system, which it has recently reaffirmed.11 India’s strategic weight may be too great for the United States to permit any significant division whatever the circumstance. The United States must understand and manage challenges including India’s ideology and diplomatic positions to achieve an enduring partnership in the region. There may be other disputes among states with vital interests in the region. The United States must build further relationships with countries like Singapore, Malaysia, Indonesia, and Thailand, to name a few. These countries already have internal agreements and possibly some lingering distrust of Western powers and past colonialist nations, making building and maintaining relationships potentially sensitive for Western powers.

Improving U.S. relations with India enough to permit U.S. forces to operate in the ANI will be challenging but possible. The growing Chinese presence in the region and the threat the ANI poses to Chinese maritime commerce through the Strait of Malacca make the ANI and the Bay of Bengal of increasing interest to strategic competitors. In addition to the potential difficulty in managing an enhanced U.S. and Indian partnership, the United States must be prepared to cope with a possible Chinese response. The possibility of conflict with China would vary depending on if the United States could interfere with traffic through the Strait of Malacca. These are just a few possible implications that could arise due to the United States gaining access to the ANI and advancing its relationship with India and others in the region. The ANI will have a crucial role in future maritime security, so the United States needs military access. The reality of this occurring in the next decade may depend on variables that have not yet been decided. The value of understanding the historical context of how the ANI was used over the last several centuries is of vital importance to any future endeavors of the United States to establish a presence on the islands. Whatever the history of the islands themselves, the overall legacy of colonialism and India’s hesitation for a superpower like the United States to be on its most strategically important islands may continue to make an outside presence on the ANI unwelcome. However, if there were multiple variables at play, such as a significant conflict in which the United States was deemed essential for the survival of Indian interests in the region, or a robust diplomatic effort was put forth to negotiate mutually beneficial terms in which the United States could work with India, then perhaps the situation would change. The United States has entered many partnerships, including the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue (QSD, a.k.a. the Quad) and Quad plus, to show that it desires to work with countries in the region and is not another colonial power with aspirations of domination. Assisting and partnering with nations in a wide range of security cooperation efforts such as disaster relief and foreign aid ensure that the United States is headed in the right direction. The importance of these efforts is further intensified by China’s encroachment on the ANI in recent years, particularly Chinese submarine and survey vessels executing reconnaissance and survey operations within India’s exclusive economic zone (EEZ).12

Geography and Strategic Importance

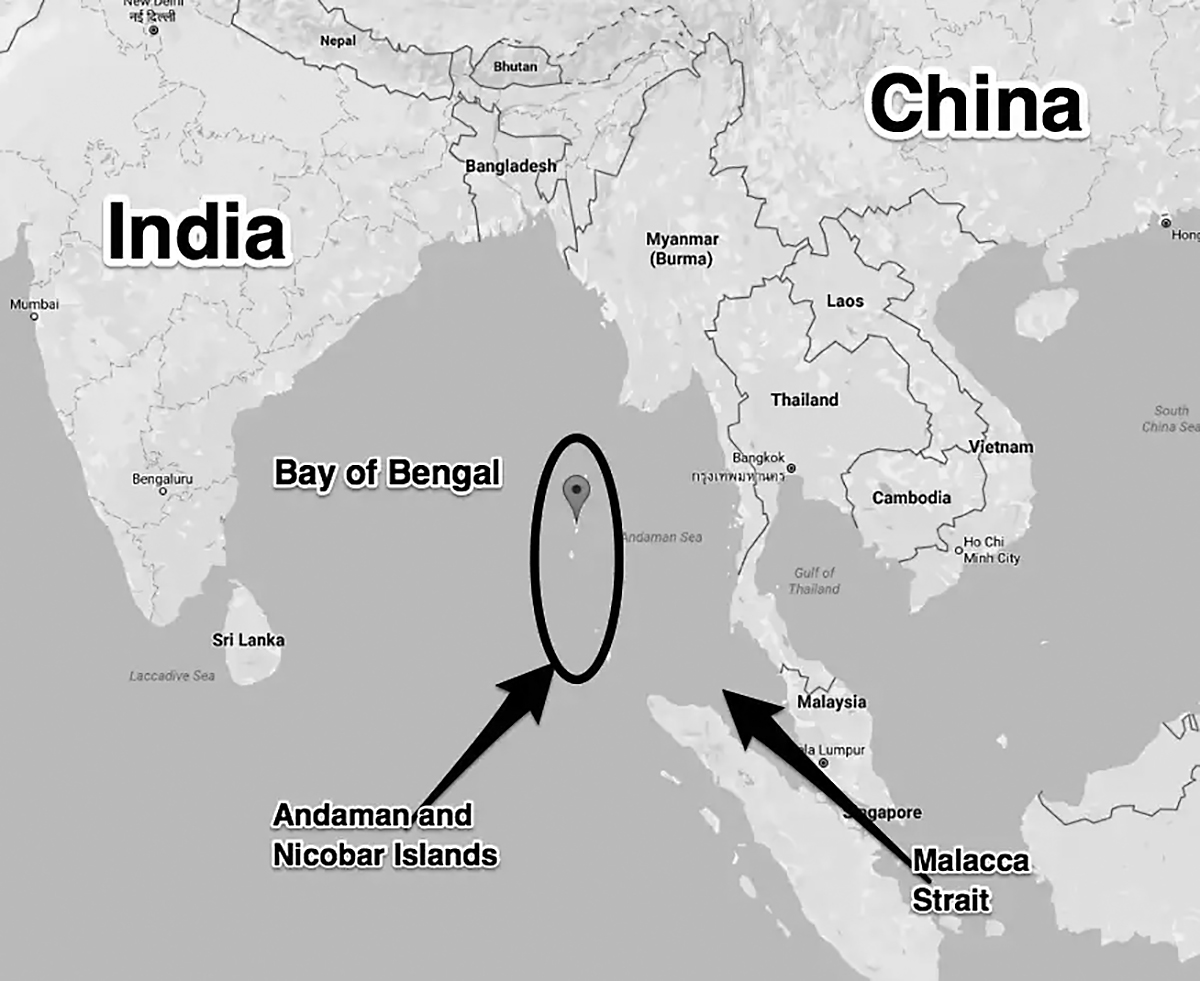

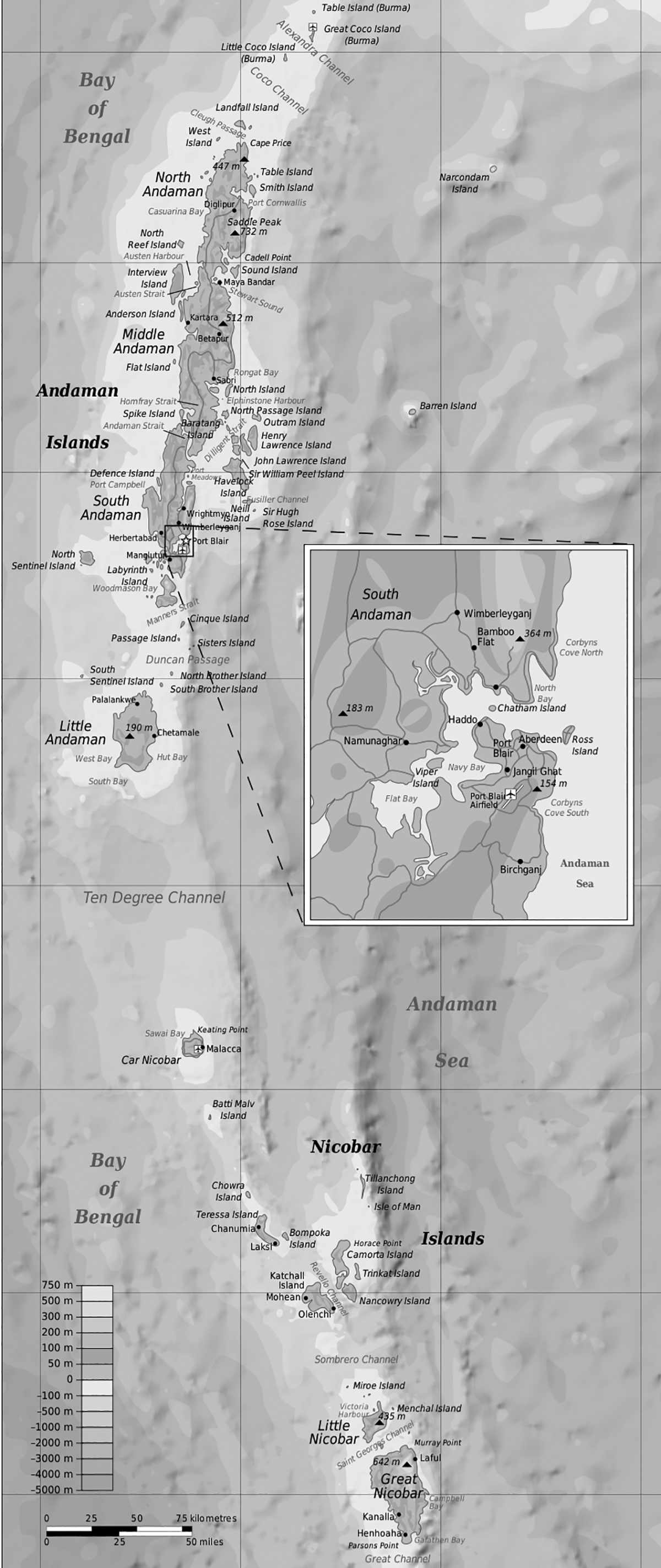

The geographic understanding and analysis of the ANI are essential to any discussion regarding maritime strategy in the Bay of Bengal and the Strait of Malacca. There is a need for a reassessment of the habitable islands within the ANI chain and their suitability for major infrastructure on land and sea. In addition, the location of the ANI in proximity to other countries and, most importantly, the Strait of Malacca are essential for any nation to understand if they want to exploit the ANI for strategic maritime purposes.13 The ANI are 573 islands, with the Andaman group having 325 islands while the Nicobar group has 247 islands. The northern islands are approximately 274 kilometers from Myanmar, the southern islands are about 193 kilometers away from Indonesia, and around 1,078 kilometers from the Strait of Malacca (map 1).14 Another aspect of the islands’ geography is the Ten Degree Channel between the ANI chain (map 2). The channel derives its name from the 10 degrees latitudinal it overlays. The Ten Degree Channel is approximately 150 kilometers wide and 10 kilometers long.15 This channel has significant military and economic importance as control of the channel would isolate the islands from each other and restrict movement. An enemy maritime seizure of the Ten Degree Channel would be devastating for lines of communication and freedom of navigation and would be essential to retain in any conflict.

Map 1. The proximity of the Andaman and Nicobar Islands to the Strait of Malacca

Source: OpIndia, 2022.

Map 2. Ten Degree Channel

Source: based on the CIA Indian Ocean Atlas.

Another consideration of the island’s geography is the significant difference between the ANI people and the people of mainland India. The island’s isolation from the mainland and millennia’s worth of different empires intermingling has created a mixed population descended from former empires’ convicts, settlers, and indigenous people. The island’s people have been traditionally slow to accept and implement mainland Indian policies. This has been evident in the past decade as Hindu nationalism has not spread as it did on the mainland. A potential fear that may arise in India is that rival nations may easily influence the islands and, in a worst-case scenario, the ANI would rebel or declare independence if another world power like China backed the ANI inhabitants. A loss of the islands would be a strategic disaster if a scenario such as this were realized.

The Indian government has seen fit to deploy a brigade command with two and a half battalions, an airfield capable of operating heavy transport and bomber aircraft, and robust logistics and maintenance facilities on the south ANI. In addition, forward naval and coast guard bases with protected harbors complement the naval and air defenses.16 Establishing deepwater ports on the Great Nicobar Island is also possible. These interests fall under an Indian joint unified command called the ANI Command.17 The significance of this command is that it shows India’s assertion in the region and the willingness and ability to act in ensuring the safety of commerce flowing in and out of the Strait of Malacca. Furthermore, the command shows the ability of India and its allies to project power to directly influence or even to blockade the Strait of Malacca. The United States could make the case that strategic position, the need for cooperation to deal with nontraditional security issues, the wide variety of small islands, narrow and shallow waters, and the sheer size of the territory necessitates a joint forces approach.18 Perhaps most important is the need for the United States to have regional support, not just from India, for a presence in the region in any sizable capacity.

Regional Relationships

One of the most critical recent partnerships in the INDOPACOM may be the Quad. The Quad was loosely formed in 2004 as part of the humanitarian response that followed a devastating tsunami that occurred in the region that year. The Quad was formally instituted in 2007 between Australia, India, Japan, and the United States, which conducted joint naval exercises the following year. The group was expected to discuss countering Chinese hostility in the Indo-Pacific and the reestablishment of a rules-based international order.19 The implementation of the Quad partnership was also an essential step in bringing India closer to the United States and would further establish India’s role as a significant power. Furthermore, a series of aggressive encounters with China have necessitated an expanded partnership that would come along with the Quad plus partnership.20 India now has good reason to fear both Chinese encirclement and Chinese domination of the waterways on which India increasingly relies. This means India now has excellent reasons to invest considerably more in developing the capabilities to secure its trade routes and sustain the regional balance of power with China.21

The United States and India may regard the ability to use the ANI to control traffic through the Strait of Malacca as an opportunity. Still, the Malacca littoral states, the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), and the regional bloc to which they belong, may regard it with suspicion.22 They may fear that outside powers and coalitions like the Quad and the Australia–United Kingdom–United States Partnership (AUKUS) will force them to choose between aligning with the West or with China.23 ASEAN was formed in 1967 in Bangkok and originally consisted of Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, Singapore, and Thailand. Burma, Brunei, Cambodia, Laos, and Vietnam have since joined. ASEAN is not a military alliance but a consultative organization that pursues common political and economic interests, acting only by consensus. It has developed a variety of regional conferences to which the United States, India, and China belong. Perhaps ASEAN’s approach to the strategic competition between the United States and China seeks to weave the great powers into a web of interests that conflict would disrupt. Establishing a significant military base, especially if the United States engaged in the ANI, would probably cause extreme concern for the ASEAN members, especially the Malacca littoral states. An essential player in ASEAN is Singapore due to its geographic location.

The geopolitical aspect of India-Singapore bilateral relations improved tremendously from the Cold War period to the post-1997 period. This is partly because of the convergence of the ideas and interests of political leaders such as Narasimha Rao, Atal Bihari Vajpayee, and Goh Chok Tong. Significantly, Rao and Vajpayee valued the benefits of India’s increased presence in Southeast Asia to avoid being isolated from the region and losing international relevance.24 A shared experience of colonial roots and postcolonial expansion has unified countries along the Strait of Malacca. The fundamentals of India-Indonesia relations have been formed by their shared colonial experiences, anticolonial struggles, and shared worldviews.25 The same could be said of Malaysia. India views its ties with Malaysia as a core element of its Act East Policy. Both nations firmly commit to multiculturalism, pluralism, and inclusive development.26 However, India’s governmental support of Hindu nationalism may bring India’s commitments into question.

Economic Potential

In 2004, the third largest recorded earthquake in history created a tsunami that severely affected many of the islands in the ANI chain and caused hundreds of deaths. The suitability for sustaining large infrastructure on the islands came into question as the ANI’s precarious position along one of the world’s major fault lines may make it prone to similar natural disasters in the future. Furthermore, the island’s geographic isolation, climate, and heavy forestation have made building large infrastructure difficult.27 However, within the last decade, the Indian government has transformed the ANI to support substantial economic growth. This includes building a railway connecting Diglipur in the north to the central city of Port Blair in the south and upgrading roadways. This provides access to ports via ground transportation on a scale that has not been possible. Furthermore, resort development is occurring on a large scale, which has the tourism industry projected to boom over the next decade. The resort development includes the creation of commercial seaplane base hubs for the use of seaplanes, which have proved highly successful in tourism areas such as the Maldives. Another vital aspect is upgrading the Veer Savarkar International Airport and creating multiple regional commercial airports on ideally located islands. Perhaps the most intriguing part of the massive infrastructure upgrade on the ANI is a proposed billion-dollar deepwater port with corresponding logistical support on Great Nicobar Island.28

The implications of large-scale development on the ANI can drastically improve India’s economy. The islands will become more accessible, but they will also potentially become a significant hub along long-established sea lines of communication. The vast amount of untapped natural resources in the region that could now be harvested, including oil, natural gas, essential minerals, and the exclusive right to fish inside one of the last areas where fish stocks are relatively untouched, are eye watering to most economists and are well within India’s EEZ purview.29 China has also shown interest in these areas and has been consistently observed within the ANI EEZ in the last several years. While encroachment into a country’s EEZ is not necessarily a threat to a nation’s sovereignty, it may be seen as a lesser type of intrusion—and one India should be wary of.

The United States, Quad, and ASEAN members could assist the economic development of the ANI with investment and expertise. ASEAN member economic involvement may make the establishment of military facilities more palatable as well. However, ASEAN members may incite China by doing so, which is a risk they will need to calculate. The growing economic importance of the ANI to India further highlights the need for security. Suppose the ANI could be one of the major hubs along multiple sea lines of communication (SLOC) in the future. In that case, the attention will necessitate and welcome additional involvement from the international community. Theoretically, if the infrastructure is present to support a drastic increase of inhabitants on the island, it would be beneficial to economic interests to welcome a dramatic rise in the ANI population to progress the region’s economic output. Furthermore, the disruption of native people on the ANI due to encroachment may further complicate an already complex situation. The next decade may bring a tremendous amount of change to the islands. The United States and the international community should be ready to develop, secure, and partner with India to support mutually held interests. Of course, China has recognized India’s development of the ANI and appears to have implemented countering moves in the region.

Chinese Power Projection

China has emerged as a rising power globally with aspirations of global influence that rival its two most formidable opponents, India and the United States. This international power orientation has set the stage for multiple shows of force and some confrontations along India’s frontier borders, with Taiwan and potentially other allies in the Pacific region including the Philippines and Japan. China and India have had a long history of clashes on India’s frontier land along the Himalayan Mountains. India performed poorly in initial conflicts on its frontier during the Sino-Chinese War in 1962.30 However, the Indian military fared much better during the Nathu La and Cho La Clashes of 1967. Hundreds of Indian and Chinese soldiers were killed in a two-week confrontation centered on strategic pass locations along the Chumbi Valley during these clashes.31 In 2020, skirmishes flared up again along the disputed boundary, causing significant casualties on both sides. This resurgence of combat after nearly 50 years contributed to the growing concern about China’s aggressive actions.32

In the Western Pacific, tensions between the United States and China have increased steadily for more than a decade. Taiwan is the most important point of contention. China’s growing power and increasing concern over Taiwan’s preference for independence make a Chinese invasion more likely. The United States has asserted its commitment to Taiwan’s autonomy. China regarded the humiliating U.S. withdrawal from Afghanistan in August 2021 as an opportunity to gain an advantage by ramping up rhetoric and making large-scale military demonstrations aimed at Taiwan and intended to challenge the U.S. position. Many observers fear that China now has the confidence and capability to invade Taiwan.33

The ANI are far from Taiwan, but the strategic distance is less than the physical distance. The United States can enhance its deterrent posture in the East China Sea by taking advantage of strategic terrain elsewhere. However, with Indian attention focused on the Himalayan frontier and U.S. attention on Taiwan, both powers are neglecting the opportunities that the ANI offers. China has challenged India’s sovereignty of the ANI in recent years and has sent multiple incursions into Indian waters to directly challenge the ability of the Indian military to defend the ANI in a future conflict. China has already increased its submarine incursions, and in 2020 executed the use of unmanned underwater drones to map the ocean floor around the ANI in the same manner that they have done in the Pacific.34 These incursions into the ANI EEZ may be part of a Chinese plan to create a “new normal” within the region. However, most alarming to the U.S. and India is the alleged Chinese lease of the Coco Islands, a Burmese possession northwest of the ANI, not to be confused with the Australian Cocos or Keeling Islands to the southeast, and the central Sri Lankan maritime port at Hambantota, which was also leased to China from the Sri Lankan government. A close eye should be kept on the countries surrounding the Bay of Bengal and what agreements those countries have made with the Chinese government. In theory, a buildup of Chinese forces within striking distance would not be difficult. Furthermore, with advancements in surveillance technology and cyber warfare, maritime commerce, military operations, and the ability to influence public opinion on the ANI are certainly within the realm of possibility for the Chinese military. The Indian military has countered Chinese activity by increasing the robust nature of its ANI command to one of the most elite commands in the Indian military. Furthermore, the nearly monthly Chinese submarine incursions into the area have made the Indian navy hyperaware of Chinese activities within the ANI EEZ, and it is prepared to detect and interdict these vessels if a threat is perceived.35

Similarly, there are Chinese ports funded on the Pakistani and Myanmar coasts, which is also a strategic cause for concern.36 If these ports become bases, they will allow China to interfere with maritime trade throughout the Indian Ocean. This is part of China’s String of Pearls strategy. The String of Pearl’s theory was noticed in a Western article on future energy in Asia in 2004 but was not formalized nor was the phrase ever used by the Chinese.37 China is perceived to use the String of Pearls strategy worldwide to directly answer China’s critical vulnerabilities of not controlling key choke points and trade routes in the world.38 This inability to maintain control puts China at an impasse on taking further action. The phrases the Strait of Hormuz Dilemma and the Malacca Dilemma have become common among military circles to describe China’s vulnerable strategic problem.

The Malacca Dilemma denotes China’s dependence on the Strait of Malacca and inability to secure traffic through the strait. Specifically, China is most concerned about its reliance on energy imports. According to the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) calculations, about 20 percent of global maritime trade and 60 percent of China’s trade flows are moved through the strait and the South China Sea, making it the most crucial SLOC for the Chinese economy. Nearly 70 percent of China’s petroleum imports pass through the Strait of Malacca, making the Strait of Malacca essential to China’s energy security.39

The Malacca Dilemma puts the ANI firmly in the crosshairs of the Chinese. The importance of the Indian ANI command comes into full view with Chinese incursion into the region. Besides having a force that necessitates nine flag officers with a lieutenant general in command, the ANI command has some of the best military equipment in the Indian Armed Forces. The naval component includes missile corvettes, tank landing ships, fast attack craft, amphibious warfare ships, and a coast guard squadron.40 There is a brigade from the Indian Army, including an elite Bihar battalion, a reserve regiment, and an Indian Air Wing with advanced Sukhoi Su-30MKI fighters that can operate over the Strait of Malacca. The ANI can also facilitate medium- and long-range surface-to-air missiles (SAMs) and additional airfields.41

With such a powerful force, the question arises if there is a need for the United States to cooperate with India to strategically leverage the ANI and provide an additional presence in the region. As India moves away from an ANI isolation policy and begins to leverage the military and economic potential of the ANI, there must be implications from the Quad that will necessitate joint involvement regarding the ANI and the Strait of Malacca. Among these partners, the United States, Australia, and Japan may be the most beneficial partners to have in the region. They may be willing to put forth considerable efforts and resources to secure mutual interests in the region. However, an increased multinational presence may exacerbate the Malacca Dilemma and cause China to increase its assertiveness and bolster its String of Pearls strategy. This may include the implementation of significant military forces not just around the ANI but in disputed areas around the world, forming new agreements with neighboring countries to militarize strategic locations and using anti-piracy operations as an alibi for an increased presence in contested areas. Increased incursions on land and sea into the Strait of Malacca and the ANI EEZ may become more prevalent.

In recent years India has appeared to shed some of its deep-rooted anti-imperialism mentalities and in the future may be more open to robust joint relationships with regional and Western powers as indicated by the success of the Quad and mutual security concerns with Western powers. In addition, tourism and agricultural output have grown steadily along with the increasing presence of Indian military forces on the ANI.42 Many allied nations have shown the desire to increase port calls and exercises as well as engage in joint surveillance of key maritime choke points, including the Malacca, Sunda, Lombok, and Wetar straits. This could be done through the collaborative use of sovereign islands such as the Cocos (Keeling Islands) that belong to Australia and are near many of the same maritime choke points that India is concerned with in addition to the ANI.43

The United States would theoretically be the ablest partner for security and potential economic to the ANI, offsetting the Chinese threat in the region. No U.S. naval ship or aircraft has been given access to the ANI. In contrast, Japanese, French, and British naval vessels have visited the ANI, albeit low-key, without much publicity. Indian reluctance reflects past geopolitical tendencies to allow the United States access to the islands that reignite past geopolitical situations between the United States and India, including perceived imperialist fears, Cold War tensions, and, most troubling to India, the support of the United States for Pakistan.44

India has other significant fear regarding allowing other countries access to the ANI, particularly the United States and Australia. India has strong feelings that any increased interaction with the United States would almost certainly result in three distinct challenges:

- The presence of the United States in any form on the ANI would permanently foul chances of cooperation with China in the region and almost certainly escalate tensions about China’s Malacca Dilemma.

- Once an agreement is made to have a U.S. military presence on the ANI, there would be a quid pro quo expectation from the United States that India does not want to be involved.

- There would be an increased expectation for joint exercises and joint deployments between the United States and India and the possibility of India being caught in a collaborative framework between the United States and its allies, which are not within India’s strategic framework.45

In any case, the certainty of increased Chinese activity in the Indian Ocean is apparent. China has already had joint exercises with Pakistan and Russia. China has strategically engaged with Myanmar, Bangladesh, and Thailand, which has increased significantly in recent years. In addition, the success of the Quad and Quad plus indicates that mutually beneficial partnerships between India and Western powers are occurring without a threat of imperialistic encroachment. Furthermore, the United States possesses considerably advanced military technology and assets usually only shared with certain allies. Still, in the case of India, the United States may want to make an exception, given the current geopolitical climate.46 The collaboration in the Western Pacific between the United States and Japan is another indicator of the potential benefits of increased cooperation between the United States and India regarding the ANI and the Strait of Malacca. Lastly, the Cocos, also known as the Keeling Islands, could be beneficial to the United States, India, and Australia by providing the initial opportunity for a joint command separate from the ANI that could demonstrate the benefits of the joint command construct, which could be transferred in some capacity to the ANI at an agreed-on time. As India continues to grow as a world power and China continues to exert its influence in the region, the benefits of having a more robust partnership with the United States in which joint operations and commands are created may significantly outweigh any fears that still exist within the Indian military and government.

Bilateral EABO Possibilities

The U.S. regional partners and allies like Japan and Australia have developed and strengthened international military alliances that have incorporated mutually supporting efforts in the region, such as cooperation in humanitarian crises, natural disasters and maritime security. In addition, the U.S. “pivot to the Pacific” has demonstrated the United States’ commitment to stabilizing and combating an emerging Chinese threat. One of the United States’ developing military concepts is EABO. EABO is a future naval operational concept that meets the resiliency and forward presence requirements of the next U.S. joint expeditionary operations paradigm. The EABO concept plans to rapidly deploy friendly forces, seize key terrain in and around the maritime domain, and establish strong points that deny the enemy the ability to move forces. The outcome of this concept is that any enemy force will be presented with an anti-access scenario that leaves few courses of action for them. The concept is adversary-based, cost-informed, and advantage-focused.47 Although this concept is still being developed, there are multiple locations where it could be theoretically employed to significant effect. The ANI would be ideal for EABO and mutually beneficial for countries like India and the United States. Furthermore, additional opportunities could be pursued as a result of EABO, such as seaplane basing.

The United States must have close allies and partners fully invested in this concept. This would be especially important for a future partnership with India to employ U.S. forces on the ANI. Beyond the need for a strong association between the United States and India to be used effectively, the EABO concept must have sound logistical lines in an expeditionary environment, have a low signature not easily observed in an antiaccess/area-denial (A2/D2) environment, and may need to stockpile massive amounts of weapons.48 Any agreement to employ forces to execute EABO operations would be a huge strategic and diplomatic victory for the United States and make the defenses around the ANI even more formidable. However, for this to be a reality it may be imperative that the EABO concept be proven as effective and a necessity for future war.

One of the most significant difficulties military thinkers throughout history have tried to solve is determining how the character of war has changed and anticipating what is required to be successful in future conflicts. The ANI holds great potential for multiple nations to collaborate in understanding and revolutionizing warfare with technological advancement, innovative concepts of warfare from the tactical to a strategic level, multination warfare doctrine, and international law enforcement practices. Ideas include EABO, seaplane employment, the employment of the U.S. Marine Corps concept of the littoral combat regiment, and interdiction of piracy and IUU fishing interdiction can all be greatly enhanced in a collaborative effort with the ANI as the key maritime terrain.

EABO is an evolving concept that is rapidly picking up speed as a primary means of employing tactical level units in an A2/AD battlefield as stand-in forces. As technology advances, the reality of how warfare will be conducted in the future changes. The primary mission of EABO is to support sea control operations; work sea denial operations within the littorals; contribute to maritime domain awareness; provide forward command, control, communications, computers and combat systems, intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance (C5ISR); targeting, and counter targeting capability; as well as forward sustainment.49 The EABO concept is tested and modified by the U.S. Marine Corps in the Western Pacific through collaborative efforts with Japan and could also be done in the same manner with India.

A roadblock in testing and approving the EABO concept is the availability of willing allies and partners to develop the idea. In addition, the reality of using the EABO concept must be realistic, meaning that the geographic landscape must be ideally suited for the employment of the concept. The ANI’s proximity to the Strait of Malacca and the fact that more than five hundred islands lie within the ANI, as well as the availability of multiple islands immediately outside the ANI archipelago make the EABO possibilities extremely relevant to this region. Furthermore, the opportunity for the U.S. Marine Corps to jointly develop a concept with another elite unit in the Bihar Regiment is a real possibility. This would appear to be a mutually beneficial proposal for India to consider. Along with proving the concepts within EABO itself, the ability to engage in weapons deals, share technology, and eventually implement a series of joint strong points in the region as a deterrent to outside aggression may be strategically appealing to India.

Within the EABO concept, the primary tactical unit should be a littoral combat regiment with a permanent residence within the islands as part of the joint construct. Another option in the region would be the Australian Cocos Islands to the south. Of course, the U.S. and Indian governments may be years away from an agreement that would entail a sizable force of the U.S. Marine Corps stationed on sovereign Indian land. To further develop this possibility, the United States could also send advisory forces or observers to the disputed Himalayan region as a first step in building a collaborative relationship. The reality of high-level cooperation between the Indian military is mainly dependent on China’s continued aggression and the perceived need by India to have the United States supplement their forces in some capacity to deter Chinese aggression. Another possibility for expedited progression would be a change in Indian government leadership, although that may also be worse for the United States depending on the outcome. It would be prudent for the U.S. Navy to strongly consider implementing the EABO concept in any future exercise with the Indian military and, most importantly, confirm EABO doctrine as much as possible with the U.S. Marine Corps. This is a challenging task in that new military concepts are never fully proven until a war occurs, and in most cases, the concept needs modification after the first battle. The best example of this truth may be the failed Gallipoli campaign of World War I (WWI) or the U.S. Marine Corps modification of their WWII amphibious doctrine after the Battle of Tarawa. From the EABO discussion come other possibilities such as seaplane employment and joint maritime enforcement possibilities.

Sea Plane Employment

Nearly 60 years after the U.S. Navy retired its last seaplane, the EABO concept has led to a resurgence of interest in marine aircraft. Expeditionary advanced bases will rarely have runways. During WWII, both flying boats, operating from the sea or, if amphibious, from land bases, and floatplanes had a significant role in all naval theaters. Their roles included maritime patrol, antisubmarine warfare, logistics, and air/sea rescue. The Navy kept maritime patrol flying boats in service for two decades after the war. In the 1950s, it envisioned a new generation of marine aircraft, including the Martin P6M SeaMaster, essentially a flying boat equivalent to the Boeing B-52 Stratofortress. The program did not survive technical challenges and, more importantly, competition for funds from ballistic missiles, submarines, and carrier aviation. The ability of seaplanes to fly farther and faster than rotary-wing aircraft and land without runways has led to a resurgence of interest. The most apparent missions are logistical support for advanced bases and long-range air-sea rescue, but a new generation of flying boats could also perform combat missions.50 The ANI has numerous locations for seaplane bases.

International Maritime Enforcement

The international community has vast interests in the Strait of Malacca for maritime economic reasons as do other strategic competitors. The potential for the ANI to be a significant international hub from which IUU interdiction and antipiracy efforts could be launched is considerable. Many countries along the Strait of Malacca and Southeast Asia depend on fishing as their primary source of protein and a primary driver for their economies. Furthermore, antipiracy efforts are an essential element of security efforts in and around the Strait of Malacca. Nearly 120,000 vessels travel through the Strait of Malacca a year, about one-quarter of the world’s yearly shipping commerce.51 The piracy problem in the Strait of Malacca dates to 1511 when the Portuguese first took the Strait of Malacca and attempted to institute antipiracy efforts on a large scale.52 The problem has waxed and waned but never completely solved, mainly due to the 933-kilometer length of the Strait of Malacca.53

The United States could also establish a presence in the ANI with the Coast Guard. The United States has made significant efforts in counterpiracy operations around the world. The U.S. Counter Piracy and Maritime Security Action Plan of 2014 commits the United States to use all appropriate instruments of national power to repress piracy and related maritime crime, strengthen regional governance and the rule of law, maintain the safety of mariners, preserve freedom of the seas, and promote the free flow of commerce.54 The United States already has multiple partnerships with other nations, and a Coast Guard presence in the ANI could support India and the ASEAN states in both counterpiracy and the enforcement of IUU fishing. The U.S. Coast Guard is in a prime position to function as an international enforcement element easily able to partner in bilateral enforcement operations. Furthermore, the vast potential of the Quad plus members to execute antipiracy interdiction at the western exit point of the Strait of Malacca and across the Indian Ocean is immense. Based on a collaborative effort from the ANI, the combined naval resources of the United States, India, Australia, and Japan could permanently stop piracy around the Strait of Malacca and be a useful diplomatic tool.

Furthermore, the nature of IUU fishing and piracy is an easily agreeable and mutually beneficial set of problems to cooperate on and can be countered in bilateral operations. The win-win scenario appears to be an excellent way to improve relationships and use the ANI for a collaborative effort for the United States and India and potentially for all Quad members. The U.S. Coast Guard should be leveraged as much as possible to facilitate international cooperation and secure mutually beneficial strategic objectives in the Bay of Bengal, the Strait of Malacca, and the Indian Ocean. The United States is in the best position to make bilateral operations a reality by instituting additional agreements such as other defense and arms agreements, trade deals, and technology sharing. The international community’s best interests will only benefit those acting in the world’s best interests. International maritime enforcement is a set of problems that will draw support, improve economic interest and cooperation, and further existing partnerships such as the Quad.

In the case of the ANI, it is hard to argue with millennia-old truths regarding maritime terrain and the advantages of controlling one of the world’s most traveled maritime choke points in the Strait of Malacca. The challenge for the United States and India is to find common ground on which to align their security efforts in the Bay of Bengal and Strait of Malacca that will necessitate the use of the ANI. Enduring international problems such as IUU fishing and piracy provide increasing opportunities to engage in bilateral operations that align regional, global security, and economic interests for members of the Quad and most of the international community. The additional option of using the U.S. Coast Guard that can be employed as a global maritime police force instead of an overwhelming militaristic naval force like the U.S. Navy has favorable political and diplomatic appeal to both India and the United States.

However, if the escalation of a Chinese presence in the Bay of Bengal, Strait of Malacca, and the Indian Ocean continue, members of the Quad will be forced to look at how a war in the region may play out. It would be prudent for Quad members to explore concepts like bilateral EABO employment and seaplane basing in and around the ANI. This exploration would advance potential future employment of strategic ideas and capabilities and allow for a unified effort in deterring Chinese actions in the region. The decision to start engaging in exploratory military concepts may need to be made sooner than later as the strategic stakes of jeopardizing the Strait of Malacca and crucial SLOCs in the Indian and Pacific Oceans are colossal.

The U.S. Coast Guard has the unique potential to accomplish strategic maritime goals, including international enforcement of illegal maritime activities, while also being a softer option for bilateral collaboration. The ANI are ideally suited for a U.S. Coast Guard presence. The U.S. Department of Homeland Security International Port Security Program (IPSP) is ideally suited to support host nation countries and is proven effective worldwide. The U.S. Coast Guard is the lead agency for the IPSP. It is employed in a quasimilitary capacity that is ideally suited for governments seeking to avoid the attention a significant U.S. military presence would bring. The program allows sharing of the best port security practices and collaborative efforts to address international maritime issues such as IUU fishing and piracy.55 The IPSP is much less intrusive to the Indian government, facilitates bilateral collaboration in maritime security, bolsters the Indian military’s capabilities, and allows the United States to have a presence on the ANI. Implementing IPSP as part of a packaged security agreement could be a significant first step for the Indian and U.S. relationship regarding the ANI. Due to the robust nature of the U.S. Coast Guard, port visits, joint maritime patrols, and eventually permanently based aircraft, small craft, and ships could all be possibilities.

Another role that the U.S. Coast Guard could take is reviving the U.S. seaplane program. Like the Coast Guard mission of rescue operations, a turboprop class seaplane could be immediately introduced to overseas areas where the Coast Guard has a presence, including the ANI. A collaborative development effort between the U.S. Navy, U.S. Coast Guard, and the Indian Navy has the potential to eventually create a strategic seaplane fleet based out of the ANI that was of benefit to the international community and versatile enough to be employed in a combat environment if the need arose. A partnership relationship in which the U.S. Coast Guard could be based on the ANI may be more feasible and practical in the India–U.S. relationship. A potential concern among the many variables that surround a U.S. and India partnership in the ANI are different ideologies that exist between the United States and India.

Ideological Concerns

There may be a future concern residing with the United States over the growing ideological differences between the United States and India. While India is considered a democracy, it is a very different democracy than that of the United States with a classical history of a caste system in which the treatment of the lower class of India’s society has drawn criticism and negative attention from the world. Almost immediately after India declared its independence from Great Britain, India was abruptly confronted with Cold War realities when the United States formed an alliance with Pakistan in 1954.56 The sitting Indian prime minister, Jawaharlal Nehru, further strained the relationship by taking a stance of neutrality in the Cold War, neither favoring the Soviet Bloc nor the United States. This was the determining factor in the refusal of the United States to stake its regional aspirations on an alliance with India and instead chose to align closely with Pakistan.57 The alliance between the United States and Pakistan would inflict damage on the U.S. and India relationship for decades and create a considerable distrust from India toward the United States. Deep historical and religious rifts between Pakistan and India have manifested the India-Pakistan border into one of the most volatile regions in the world. In addition, historical foreign policy decisions from the United States regarding India, including large weapons deals with the Pakistani government have been detrimental to the U.S. and India relationship.

Despite the tumultuous Cold War relationship, the U.S. and India relationship improved during the latter half of the Cold War and after the fall of the Soviet Union. The relationship reached a high point during the President George W. Bush era in the early 2000s as common ground was reached on terrorism, including mutually supporting efforts and collaboration in many areas.58 However, in 2014 with the election of Narendra Modi, considerable challenges arose, primarily from the ideological approach of Modi. A known right-wing Hindu nationalist, Modi’s approach to democracy in India is a dramatic shift from what the United States would traditionally view as a pure democracy and may even be called a conservative authoritarian government.59 Furthermore, under Modi, weapons purchases from Russia during the President Donald J. Trump administration further strained the relationship, nearly resulting in sanctions being imposed on India. However, this was averted after diplomatic efforts.

The hope that the President Joseph R. Biden administration will improve the relationship further between the U.S. and India is shared by both countries. The Biden administration has put forth the effort to make India a significant partner in its security cooperation efforts on overall strategy to counter China. In terms of trade deals, defense agreements, and information sharing, the United States and India are on track to remain major defense partners for the foreseeable future. The United States is India’s largest trading partner, with more than $152 billion in trade a year.60 As the threat of Chinese influence in the ANI and Strait of Malacca region increases and China continues its aggressive posture along the northern Indian border, the opportunity for the United States and India to dramatically improve cooperation efforts is more of a reality than in decades before. The fact that U.S. forces may have a presence on the ANI despite ideological differences and past relationship woes between India and the United States is promising. However, strategic competition is always full of power plays by other major world powers. China, Russia, Pakistan, and regional authorities have a vote and will all factor into the future of the United States, India, and the ANI.

The implications of strategic competition may be the most critical set of factors that will determine the future of the ANI and how they will be used. The United States and India have many differences regarding overall goals securing and maintaining SLOCs, choke points, and a dominating military presence in the Bay of Bengal, the Indian Ocean, and the Strait of Malacca. The circumstances in the region surrounding the Strait of Malacca will most certainly change in the next decade, and indications point toward an increased Chinese presence at multiple strategic points that would threaten the ANI with strategic encirclement. This should not be allowed to occur by India, the United States, or regional powers.

The necessity for India to increase its cooperation and collaborative efforts with Western nations, including the United States, cannot be ignored. The United States has made considerable efforts to improve its relationship with India on multiple fronts. It has shown its willingness to overlook some ideological differences and past slights to maintain and grow a relationship on much better ground than in the past. The same could be said of India, which is now at a crossroads on what should be done to counter a growing Chinese threat and ensure the security of its increasingly threatened frontier lands, the least of which is the ANI. Perhaps most importantly is the opportunity for India to increase its global standing by being the nation that is willing to partner with others in the world to ensure the security and economic integrity of one of the world’s foremost maritime choke points.

Conclusion

Regarding U.S. strategic considerations, the importance of the ANI as a crucial piece of maritime terrain in the first island chain continues to be neglected, and its importance will continue to grow. Military professionals need to understand the ANI implications and role in future conflict scenarios. India has undertaken considerable efforts to enable the ANI to support a significant economic and military presence. India seems to be gradually heading in the right direction to use the islands for its strategic gain while remaining aware of any environmental ramifications. The ANI are a unique point of convergence between geography, security, and economics that India must further develop and capitalize upon. The United States may be uniquely positioned to partner with India and regional allies in various security, economic, technological, and military capacities.

China has established its strategic ports and airfields in India’s immediate neighborhood, especially Sri Lanka, Bangladesh, and Pakistan.61 While China pursues its interests in the region to counter the strategic significance of the ANI, the United States may want to reevaluate how vital the islands are and what is needed to ensure their use favors U.S. interests. The United States may have to take drastic measures to build a relationship that would allow access to the ANI. While the academic literature on U.S. strategic possibilities surrounding the use of the ANI is somewhat sparse, the island’s importance remains.

The United States must explore opportunities to take diplomatic, informational, military, and economic courses of action to create an enhanced partnership with India that includes access to the ANI.62 The capability of the United States to convince India that a U.S. military presence in the ANI would be beneficial for both nations and the region is unclear. Nevertheless, seemingly small cooperative events such as dignitary visits, small-scale exercises, or brief port visits by the U.S. Coast Guard would be beneficial in accomplishing strategic goals and strengthening relationships. Further exploration in these areas would significantly enhance the academic debate and potentially draw the United States, India, and regional partners and allies toward a mutually beneficial outcome regarding the ANI that promotes global security and international economic prosperity.

Endnotes

- Phillip Endicott et al., “The Genetic Origins of the Andaman and Nicobar Islands,” American Journal of Human Genetics 72, no. 1 (January 2003): https://doi.org/10.1086/345487.

- Rajni Trivedi et al., “Molecular Insights into the Origins of the Shompen, a Declining Population of the Nicobar Archipelago,” Journal of Human Genetics, no. 51 (2006): https://doi.org/10.1007/s10038-005-0349-2.

- Deryck Lodrick, “Andaman and Nicobar Islands,” Encyclopædia Britannica.

- Pran Nath Chopra, T. K. Ravindran, and N. Subrahmanian, History of South India: (Ancient, Medieval and Modern) (New Delhi, India: S. Chand, 2003).

- Sailendra Nath Sen, An Advanced History of Modern India (New Delhi, India: Macmillan India, 2010).

- Dhiraj Kukreja Kukreja, “Andaman and Nicobar Islands: A Security Challenge for India,” Indian Defence Review 28, no. 1 (January–March 2013).

- L. P. Mathur, “A Historical Study of Euro-Asian Interest in the Andaman and Nicobar Islands,” Proceedings of the Indian History Congress 29, no. 2 (1967): 56–61.

- Karl Ritter Von Scherzer, Narrative of the Circumnavigation of the Globe by the Austrian Frigate Novara (Commodore B. Von Wullerstorf-Urbair), Undertaken by Order of the Imperial Government, in the Years 1857, 1858, & 1859, under the Immediate Auspices of His I. and R. Highness, vol. 2 (Vienna, Austria: Austrian Empire, 1859), 68.

- Romila Thapar, The Penguin History of Early India: From the Origins to AD1300 (New Delhi, India: Penguin Books, 2015), 364–65.

- Kukreja, “Andaman and Nicobar Islands,” 1–3.

- “India Will Never Be a Part of an Alliance System, Says External Affairs Minister Jaishankar,” Hindu, 21 July 2020.

- Jamie Seidal, “ ‘Right on Our Doorstep’: Secret Sub Reveals China’s Chilling Plan,” news.com.au, 24 December 2019.

- Geoffrey F. Gresh, “The Indian Ocean as Arena,” in To Rule Eurasia’s Waves: The New Great Power Competition at Sea (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2021).

- “Andaman & Nicobar Islands,” mapsofindia.com, accessed 29 July 2022.

- Jayanta Gupta, “Chinese Naval Ships Detected Near Andamans,” Times of India, 4 September 2015, 2.

- Pushpita Das, “Securing the Andaman and Nicobar Islands,” Strategic Analysis 35, no. 3 (May 2011): 465–78, https://doi.org/10.1080/09700161.2011.559988.

- “More Muscle for India’s Andaman and Nicobar Defence Posts to Counter Hawkish China,” Hindustan Times, 26 August 2017.

- Patrick Bratton, “The Creation of Indian Integrated Commands: Organizational Learning and the Andaman and Nicobar Command,” Strategic Analysis 36, no. 3 (2012): 440–60, https://doi.org/10.1080/09700161.2012.670540.

- Mattias Cruz Cano, “Strengthening of the ‘Quad’ Could Heighten Trade Tensions with China,” International Tax Review, 25 November 2020, 1–3.

- Thorsten Wojczewski, “China’s Rise as a Strategic Challenge and Opportunity: India’s China Discourse and Strategy,” India Review 15, no. 1 (February 2016): 22–60, https://doi.org/10.1080/14736489.2015.1092748.

- “America’s Quadrilateral Antidote to China,” Trends Magazine 19, no. 4 (April 2021): 38–44.

- Ajaya Kumar Das, “India’s Defense-Related Agreements with ASEAN States: A Timeline,” India Review 12, no. 3 (2013): 130–33, https://doi.org/10.1080/14736489.2013.821319.

- Jena Devasmita, “International Trade, Structural Transformation, and Economic Catch-Up: An Analysis of the ASEAN Experiences,” Journal of Economic Development 46, no. 3 (September 2021): 133–53.

- Yogaananthan Theva and Rahul Mukherji, “India-Singapore Bilateral Relations (1965–2012): The Role of Geo-Politics, Ideas, Interests, and Political Will,” India Review 14, no. 4 (February 2015): 419–39, https://doi.org/10.1080/14736489.2015.1092745.

- Vibhanshu Shekhar, “India and Indonesia: Reliable Partners in an Uncertain Asia,” Asia-Pacific Review 17, no. 2 (2010): 76–98, https://doi.org/10.1080/13439006.2010.531114.

- Rajiv Bhatia, “India-Malaysia Partnership in the Pink,” Gateway House, Indian Council on Global Relations, 24 May 2017.

- D. K. Paul, Yogendra Singh, and R. N. Dubey, “Damage to Andaman & Nicobar Islands Due to Earthquake and Tsunami of Dec. 26, 2004,” SET Golden Jubilee Symposium, 21 October 2012.

- Surya Kanegoakar, “The Andaman and Nicobar Islands Offer an Ocean of Opportunities,” India Global Business, 13 July 2020.

- “The Andaman and Nicobar Islands Offer an Ocean of Opportunities,” 2.

- Neville Maxwell, “The Border War,” part 4, in India’s China War (Harmondsworth, UK: Penguin Books, 1972), 360–400.

- Probal DasGupta, Watershed 1967: India’s Forgotten Victory over China (New Delhi, India: Juggernaut, 2020).

- Snehesh Alex Philip, “Chinese Troops Challenge India at Multiple Locations in Eastern Ladakh, Standoff Continues,” Print, 24 May 2020.

- Chris Buckley and Steven Lee Myers, “ ‘Starting a Fire’: U.S. and China Enter Dangerous Territory over Taiwan,” New York Times, 9 October 2021.

- “India, Australia Could Sign Pact for a Military Base in Andaman’s and Cocos Islands—Experts,” Eurasian Times, 23 May 2020.

- Seidel, “ ‘Right on Our Doorstep’.”

- Sidra Tariq, “Sino-Indian Security Dilemma in the Indian Ocean Revisiting the String of Pearls Strategy,” Spotlight on Regional Affairs 35, no. 6 (2016): 1–30.

- Virginia Marantidou, “Revisiting China’s ‘String of Pearls’ Strategy: Places ‘with Chinese Characteristics’ and Their Security Implications,” Pacific Forum CSIS: Issues and Insights 14, no. 7 (June 2014): 1–3.

- David Brewster, “Beyond the ‘String of Pearls’: Is There Really a Sino-Indian Security Dilemma in the Indian Ocean?,” Journal of the Indian Ocean Region 10, no. 2 (2014): 133–49, https://doi.org/10.1080/19480881.2014.922350.

- Pawel Paszak, “China and the ‘Malacca Dilemma’,” Warsaw Institute, 28 February 2020.

- Rajat Pandit, “India to Slowly but Steadily Boost Military Presence in Andaman and Nicobar Islands,” Times of India, 7 May 2015.

- N. C. Bipindra and Devirupa Mitra, “Tiger Outsmarts Dragon in Andaman Waters,” New Indian Express, 23 March 2014.

- Sujan R. Chinoy, “Time to Leverage the Strategic Potential of Andaman & Nicobar Islands,” Parrikar Institute for Defense Studies and Analyses, 26 June 2020.

- Chinoy, “Time to Leverage the Strategic Potential of Andaman and Nicobar Islands,” 3.

- Chinoy, “Time to Leverage the Strategic Potential of Andaman and Nicobar Islands,” 4.

- Chinoy, “Time to Leverage the Strategic Potential of Andaman and Nicobar Islands,” 4–5.

- Chinoy, “Time to Leverage the Strategic Potential of Andaman and Nicobar Islands,” 6.

- Tentative Manual for Expeditionary Advanced Base Operations (Washington, DC: Headquarters, Marine Corps, 2021), 3.

- Ho Beng and Wan Ben, “Shortfalls in the Marine Corps’ EABO Concept: Expeditionary Advanced Basing Would Be Problematic on Both Strategic and Operational Levels,” U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings 146, no. 7 (July 2020): 30–34.

- Tentative Manual for Expeditionary Advanced Base Operations, 1-4.

- William F. Trimble, “Seamaster,” in Attack from the Sea: A History of the U.S. Navy’s Striking Force (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 2016), 81–92.

- Dmitry Bokarev, “Piracy in the Strait of Malacca: An Age-Old Problem Whose Future Is Unclear,” New Eastern Outlook, 22 September 2020.

- Bokarev, “Piracy in the Strait of Malacca,” 2.

- “Strait of Malacca Is World’s New Piracy Hotspot,” NBCNews.com, 27 March 2014.

- U.S. Counter Piracy and Maritime Security Action Plan (Washington, DC: U.S. Department of State, 2014).

- “Operations Home,” U.S. Coast Guard (USCG), accessed 2 August 2022.

- S. D. Muni, “India and the Post–Cold War World: Opportunities and Challenges,” Asian Survey 31, no. 9 (1991): 862–74, https://doi.org/10.2307/2645300.

- Judith E. Walsh, A Brief History of India (New York: Checkmark Books/Infobase, 2007), 188–95.

- Satu P. Limaye, “U.S.-India Relations: Visible to the Naked Eye,” Asia-Pacific Center for Security Studies, 2013, 1–12.

- Iza Ding and Dan Slater, “Democratic Decoupling,” Democratization 28, no. 1 (2020): 63–80, https://doi.org/10.1080/13510347.2020.1842361.

- Aparne Pande, “Challenges Notwithstanding, Why US Wants ‘Partnership of the 21st Century’ to Blossom with India,” Outlook India, 1 October 2021.

- “Strategic Salience of Andaman and Nicobar Islands: Economic and Military Dimensions,” National Maritime Foundation, 3 August 2017.

- Balwinder Signh, “India-China Relations: Conflict and Cooperation in Indo-Pacific Region,” Journal of Political Studies 25, no. 2 (December 2018): 91–104.