Michael Cserkits, PhD

https://doi.org/10.21140/mcuj.20211201008

PRINTER FRIENDLY PDF

EPUB

AUDIOBOOK

Abstract: In this article, the author will examine the representation of armed forces in cinematic productions and anime, with case studies of the United States and Japan. The sample will consist of a movie that has a clear involvement of the United States armed forces and of an anime series that was cofinanced by the Japanese Self-Defense Forces. The analytical method used will be textual analysis, in combination with videography, a method that supports interaction analysis of moving images. In comparing those two different approaches of the armed forces of Japan and the U.S. military, the author hopes to shed light on not simply the representation of the groups but also desired self-identification of the respective armed forces.

Keywords: propaganda, cinema, videography, Japan, U.S. military

Introduction

The scope of this article is to present selected case examples of representations of different armed forces. The examples differ not only from their modus operandi—as on the U.S.-North American side the material analyzed will be a mainstream cinematic movie (Transformers 4: Age of Extinction), and on the Japanese side an animated series (Gate: Thus the JSDF Fought There!)—but also on the historical background of these two opposite cases. The reason for choosing such different examples lies in the same logic that they use, as this article will illustrate during the analysis. The United States, as one of the victors of World War II and as a still uncontested military power in the globalized world, has developed an impressive industrial-cinematic complex with a startling—and sometimes even tense—history of cooperation, which will be shortly explained in the subsequent section. This complex will be compared with Japan, which can be seen as its counterpart when it comes to military history. After being on the losing side of World War II, Japan has developed its own unique way of distributing and presenting the Japanese Self-Defense Forces (JSDF) in a civilian context, with the use of anime movies and series.

Both sides, as this article argues, have different ways in presenting their armed forces to a civilian audience. But even though there are so many differences in culture, language, and presentation style, they are both trying to reach the same goal: gain popular domestic support and backup for their soldiers, regardless of their tasks or missions.

The Japanese Side

On the Japanese side, Christopher Hughes argues that the JSDF have become more popular and fashionable through their “manga-ization,” especially in recruitment materials.1 The JSDF have also managed to mediate security threads for Japan through a narrative in special anime, such as Kantai Korekushon (Japanese: 艦隊これくしょん; English: Kantai Collection) with a focus on the maritime dimension of the JSDF, which aired in 2015.2 Takayoshi Yamamura has traced the cooperation between the JSDF and anime producers back to the 1980s, beginning with a call for more realism in anime, but “it was not until the year 2000 that JSDF began publicly collaborating with the production of anime, and JSDF began actively collaborating with televised anime from around 2003 to 2004.”3 After several attempts and series, which all created only a low level of feedback, the series Gāruzuando Pantsā (Japanese: ガールズ & パンツァー; English: Girls and Panzer) was the first hit that brought a shift in the image of the JSDF in 2012 to a more popular and sophisticated image, immediately followed by Gate: Jieitai Kano Chi nite, Kaku Tatakaeri (Japanese: ゲート自衛隊彼の地にて、斯く戦え; English: Gate: Thus the Japanese Self-Defense Force Fought There!) in 2015 and Haisukūru Furīto (Japanese: ハイスクール・フリート; English: High School Fleet) in 2016, the latter providing immense public relations support for the Japanese Maritime Self-Defense Forces (JMSDF).4 Even if the highly sexualized representation of younger girls in such productions has been subject to academic critique, the current literature shows no traceable negative consequences for the JSDF as whole.5

At most, the aim seems to be to gain topicality and to enhance the popularity of JSDF. In other words, the campaigns act as nothing more than another avenue for publicity in order to get the attention of younger generations and instill in them a sense of familiarity towards JSDF.6

This approach by Japan is a clever use of smart power (an attempt that combines soft and hard power in an innovative way), where Japan ranks eighth in the world and the United States fifth, a term first introduced by Hillary R. Clinton in 2009 during her nomination hearing to be secretary of state.7 As Yee-Kuang Heng has noted, smart power is seen in Japan not only as a tool for the state, used in an integrated or comprehensive approach led by the national grand strategy, but rather a tool that is used by the JSDF, contributing to promoting a helpful and friendly image around the world.8 As missions abroad are not the primary tasks for the JSDF (contrary to the distinct expeditionary character of the U.S. forces), those smart power strategies are not as well documented as the domestic communication regimes that are dominating contemporary Japan. Following the study of Sabine Frühstück, where she stated that the Japanese Ministry of Defense had first “symbolically ‘disarmed’ the Self-Defense Forces; normalized and domesticated the military to look like other (formerly) state-run service organizations such as the railways and postal systems” back in the 1970s, the current shift to a remilitarization of the Japanese Self-Defense Forces has clear strategic impacts due to the position of Japan, bordering a revitalized Russia in the north and a rising China in the west, not to mention a still unpredictable North Korea in its immediate neighborhood.9 Although a distinct militarization and rework of war memories has not fully encompassed the whole of society, JSDF has “benefitted from the utilization of popular culture, which enhances intimacy towards JSDF, particularly among young people.”10 This intimacy nurtures nationalism, as it reshapes images and symbols from their original historical context and replace it in a more suitable discursive way.11 This practice is known as invented tradition, a term introduced by the historians Eric Hobsbawn and Terence Ranger:

“Invented tradition” is taken to mean a set of practices, normally governed by overtly or tacitly accepted rules and of a ritual or symbolic nature, which seek to inculcate certain values and norms of behavior by repetition, which automatically implies continuity with the past. In fact, where possible, they normally attempt to establish continuity with a suitable historic past.12

By creating a connection between certain aspects of the historic past and explicitly concealing other aspects of this epoch, continuity is produced to be used or even abused.

As previously mentioned, the examined anime series will be Gate: Jieitai Kano Chi nite, Kaku Tatakaeri as it clearly depicts the above-mentioned trends as well as several attempts to reshape the Japanese past when talking about its armed forces. Its unique selling point, which makes it so interesting, is that it solely deals with the JSDF, its tactics, techniques, and procedures as well as a scripted picture of everyday life as a soldier. Contrary to High School Fleet, Arpeggio of Blue Steel, Kantai Collection, or others, the main character of the series is not a young girl or a group of young girls, but a fully grown officer in his mid-30s in the JSDF with a credible background story and social life as well. Notably, Paul Martin has also analyzed the same anime, but with a clear focus on the connection between the series and Japan’s rising nationalism.13

The United States’ Side

The intense bond between the military and the U.S. industrial complex was first built during World War I, when private firms were contracted to design the first aircraft.14 Although the aspect of the closer cooperation between the cinematic complex and the Department of Defense (DOD) is a topic worth exploring, there already exists a vast literature about this theme, and it would be beyond the scope of this article. After the end of World War II, concerns about Communist filmmakers in Hollywood led to a quarrel between those two components, which lasted until the first high-budget production was released with support from the Pentagon with Top Gun in 1986.15 Since then, there has been a shift in the military-cinematic-industrial complex. Additionally, the target audience changed during the last 60 years, from a diversified mission in the beginning, such as military documentaries for educating specific audiences or movies produced in foreign-occupied territories to promote American values and ideas, to a straightforward target audience committed to the use of military means as legitimate and necessary, strengthening the reputation of the armed forces and helping to recruit new soldiers.16 With the blockbuster Transformers in 2007, the cooperation between DOD, Hollywood, and the merchandising industry reached a new level.

For critical literature regarding the Transformers movie, several authors had already stated their concern that since the first cooperation in 2007 between the Pentagon and the movie industry in Hollywood, an effective but dubious collaboration emerged: “The synergies of the Paramount-Pentagon partnership were simple but powerful—free high-tech stage props in exchange for a two-hour recruitment advertisement for the military.”17 This partnership proved useful, as Transformers was just one of a series of civil-military movie cooperations that would occupy the big screens of cinemas all over the world, starting with Iron Man to GI Joe and several others. This symbiotic relationship would not stop at the screen but rather reach much deeper into society, as William Hamilton has pointed out clearly: “Today’s troops effectively received basic training as children.”18 Apart from making young teenagers familiar with the military and its capability, since the deepening of the cooperation between Hollywood and the Pentagon, controversial political messages are no longer welcome and might even be cut out of the script.19

But does this political agenda apply to the whole Transformers series? Tanner Mirrlees had analyzed the first two movies, Transformers and Transformers: Revenge of the Fallen, where she comes to the conclusion that the main profiteer of these two action movies was the DOD, as installations (e.g., Air Force bases) worked as shooting scenes and backgrounds, and almost all modest-to-middling characters (e.g., tourists, soldiers, or guards) were played by real soldiers or ex-military personnel.20 However, not only did the DOD gain positive feedback out of the cooperation, it could also present its newest technological advances, declare the ongoing wars as Joint operations (as the Navy and Air Force support the troops on the ground in exotic places), and further boost recruitment activity. As for Transformers: Age of Extinction, it was the first movie where the Chinese Movie Channel had invested lots of effort (and money) in it to secure its success on mainland China, despite heavy critique from the United States due to the growing Chinese influence in the plot and some semipolitical messages, which presented the Chinese officials as brave and benevolent.21

Another aspect of the movie in the recent literature are the characters, Autobots and Decepticons, themselves. Harlon D. Wilson assumes that the robotic violence in the movie is a vehicle for sexuality, where “transformers collectively function as a channel for technomasculine desire and American sociocultural production.”22

Methodology

The methodological approach will be presented via an audiovisual research agenda. As Hubert Knoblauch et al. point out, “video has become a medium that pervades our everyday life.”23 On the one hand, the way of producing the situational arrangements that the producer wants us to see has a huge impact on the message that is transported via synchronic elements of vision and sound. On the other hand, editing is also a very important method for further analysis. Knoblauch et al. call this “recipient design.”24 Therefore, this article considers that it is analyzing edited cinematic products and will first classify them as highly selected and as very reactive, as it is unlikely that situations in the films happened exactly in the presented time frame.

To handle these fundamental elements, which are embedded in the nature of video, Knoblauch and Bernt Schnettler invented a method for video analysis, which they call videography.25 Videography consists of three main elements, though for this analysis only the first two steps are relevant: first, a descriptive approach that considers all visible elements seen in the video as well as the modes of production, at least those that can be reconstructed. This comes closest to the mode of a close reading or textual analysis when compared to written material. In this first step, a detailed transcription of the respective scene is produced, giving special emphasis on cut scenes, background music, and the arrangement of the actors. Second, the focus of the analysis switches to the “interaction taking place in a certain social situation.”26 The content may be fictional, but to be understood by the audience, the editors and producers have to rely on replicable social interactions that are nonfictional, with the possibility of creating new belief systems or myths. As the figure and uniform of a soldier may vary in degrees between Japanese and American points of view, both audiences have certain expectations about their behavior, their role in society, and the purpose of serving their country. In varying these expectations to different degrees, the producer can build a role model from scratch and highlight socially expected or anticipated behavior, while neglecting other (but nevertheless given) parts. The comparison with a ray of light may be useful to describe this method: As light consists of different colors, the animation or cinematic context works as a prism, filtering special colors out while reinforcing others. Features (sound, picture, speech) of videos, movies, and anime appear simultaneously, so a descriptive approach is necessary to gather as much information as possible to create a dense description of what is seen by the viewer. As for the constraints of this approach, the analyzed source is already edited, shaped, and formed, and is respectively fictional, especially for the animated part of the material. Videography is therefore applicable, as although the protagonists are not real, their messages are, and they are embodied in the editing process, which will be traced and examined.

Analysis of Gate

As for a short synopsis of Gate, the main plot deals with a mystical portal (the Gate), which opens in the middle of Tokyo. Soon after this interdimensional tunnel had opened, a mystical and medieval equipped army attacks Japan, but it is shortly defeated when the JSDF launched its counterattack. After establishing a forward operational base, which will later be a city called Alnus Hill, the Japanese government named the fairy world the “Special Region.” The series revolves around the main character, Yōji Itami, a first lieutenant who will lead a reconnaissance team to the Special Region.

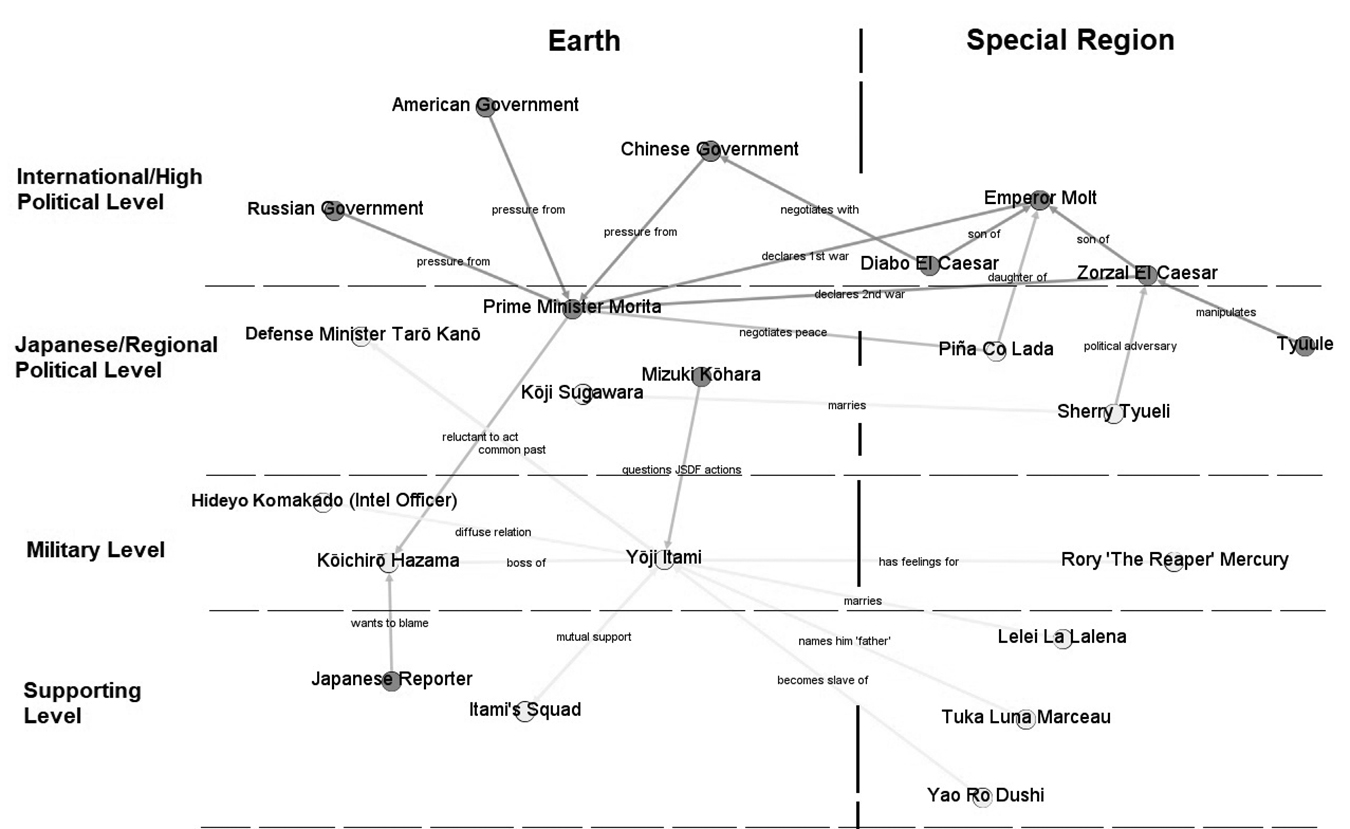

Regardless of the plot or even the fictional character of the series, figure 1 already shows the main narrative that is deeply rooted within the show. As shown, most adversaries or evil characters are located above the military level. In this case, the only political players that remain trustworthy during the show are the minister of defense and the special representative of Japan located in the Special Region, a young diplomat named Kōji Sugawara, who puts his life in danger when giving political asylum to one of Zorza El Caesar’s (son of the emperor and later the emperor) political adversaries. There are no malcontents in the supporting or civilian level and all their intentions are clearly outspoken with no hidden agenda, making them the perfect population for civil-military cooperation (CIMIC), quickly repairing all of the damage that has been done during the first counterattack of the JSDF.27 For example, after Itami and his squad are trapped in a city near Alnus Hill, which is under siege of local bandits, they order an air strike. However, to prevent casualties, the JSDF just send a Bell AH-1 Cobra attack helicopter, which wipes out the enemy. After arriving over the sky of the besieged city, the following dialogue occurs:

(12:47) Hamilton Uno Ror: “It’s a monster.” [“Ride of the Valkyrie” music starts]

Piña Co Lada: “A flying horse of steel? How can this even exist? No soldier or army can match such a level of force! How it can eradicate everything. No pride, no glory, nothing left in its wake.” [Helicopter begins to shoot down people]

Lelei La Lelena: “The battle is over.”

Tuka Luna Marceau: “It got every last one of them?”

Piña Co Lada: “Does the goddess really think this low of us? Are we really so small? So insignificant?”

JSDF-soldier 1 (ropes down from another helicopter): “Go, go, go. Clear the staging area for the [prisoners of war] POW. And another one for the survivors.”

JSDF-soldier 2: “Hey, Serge. I found one.”

JSDF-soldier 3: “Colonel. Yoga here. No more enemies on sight. Looks like we got a clean sweep. I’m out.”

Colonel: “All right.”

Itami: “Looks like we’re done.”

Citizen: “Thank you, we are all safe thanks to you. The men in green.” [“Ride of the Valkyrie” song slowly ends] “But I must ask, who are you, where are you from?”

JSDF-soldier 3: “We are from Japan.” [Catches breath and waits a second] “The Self-Defense Force.” (13:56)28

Figure 1. Relationships in Gate, illustrated with Network-Analysis (light gray=partner; dark gray=adversary)

Source: Courtesy of author, adapted by MCUP.

Several elements are cleverly intertwined within this scene that deals with the concepts of help and strength. First, the propagandistic element, which is double-sided. One effect is presented toward the audience, in reference to the “Ride of the Valkyries” scene from the 1979 film Apocalypse Now. The second one is a cinematic element within the series, as the overwhelming combination of a helicopter attacking with famous background music (at least for people who have already engaged in movies dealing with the military) would clearly demoralize the enemy; at least, that is the scripted intent the author presumes is the effect of this scene. Given the similarity of the pictures between the helicopter formation flying to end the siege and the original composition of helicopters in Apocalypse Now, a reframing took place that positively underscores the power of Army aviation instead of branding it as platform of war crimes (e.g., Francis Ford Coppola’s movie). Beside the propaganda element, the national pride can be traced, as it is indirectly expressed from outsiders (Princess Co Lada and her assistance), who ambivalently watch the scene with a mixture of pure angst and despair, as they now realize that they have chosen to fight such a capable adversary. Immediately after this scene, Co Lada tries to negotiate peace and convinces her father to stop the bloodshed. The third element is the CIMIC component to show the audience that the second the fighting ends, measures are taken to support the civilian population as well as the wounded enemies, just like the internationally recognized Hague Conference on Private International Law would demand. Fourth, the self-perception of the JSDF is presented through the last dialogue between a citizen and the JSDF soldier, who are referred to as “men in green.” With no hesitation, even after a fight and surrounded by dead and wounded people, the soldier just states who they are, with a strong impression and stable voice.

There is no literature that describes how a modern, high-technology army would behave if they met a medieval opponent, with no offensive capabilities, vast lands, and possible resources and raw materials that are unexplored and unknown to their inhabitants. But history has shown that when two unevenly military powers collide, the stronger had no hesitation in taking advantage, no matter if it was during the scramble for Africa or the Second World War. In picturing a possible alternative, the series and its coproducer, the JSDF, wanted to give the audience an impression that the National Armed Forces are distinctively not an expeditionary or even colonial force (even if this creates a little friction, as Alnus Hill is per se a military base within extraterritorial borders). This nonexpansionistic touch can be seen as a direct approach to rewrite the very aggressive approach of Japan before and during the Second World War, suggesting that this would never happen again.

Contrary to the civilian and supporting level, the JSDF stationed in the Special Region has to frequently deal with political influence, both from the real world and the Special Region. Not only does the (reluctantly portrayed) Japanese prime minister have problems with the (belligerent) American, Russian, and Chinese presidents, these international counterparts also interfere in domestic affairs. In a trial to refurbish the first gate incident, several members of the Special Region are visiting Japan, but American, Russian, and Chinese Special Operation Forces (SOF) tried to kidnap some members of the delegation to further subdue the already-weak prime minister. Even after these SOF were all killed by Rory Mercury (a fierce 961-year-old demigoddess and apostle of Emroy, the God of Darkness, Death, War and Violence), the Japanese domestic politicians did not sympathize with the efforts of the JSDF, as the following dynamic dialogue, where Rory Mercury shall give testimony to the defeat of a Fire Dragon, who killed civilians, will show:

(11:25) Mizuko Kōhara [interrupting Tuka Luna, raises tone of voice]: “According to the report, when the dragon attacked, it killed one hundred and fifty people fleeing the village. But not a single soldier was killed or injured during that engagement.” [camera starts spinning around her]. “The Self-Defense Force is supposed to risk their lives and fight for those in danger. But here, they chose to run from that fight and it costs people their lives!” [Camera switches back to Rory, who frowns, then immediately switches back to Mizuko, she screams] “SO YOU NEED TO TELL US EVERYTHING. Tell us what you saw, tell us what they did! Tell us the truth!”

Rory Mercury [camera switching back to Rory, she takes a big breath and screams]: “ARE YOU A GOD DAMN IDIOT?” [People holding their ears]

Mizuko Kōhara: “Huh? Excuse me?”

Rory Mercury: “I believe you heard my question. You are probably asked that a lot. Little Miss Thing.” [smiles]

Mizuko Kōhara: “You speak Japanese?”

Rory Mercury: “Well, look who just caught up. I assume what you really want to know is how Itami and his people fought against the dragon, am I right?” [Cutback of the events] “They did everything they could, and then, so, they did not hide in their carriages nor behind any civilian. I tell you they did nothing of this sort.” [Mizuko gasps] “Let’s get to the point, shall we? There are times when a soldier must protect their own life, but you sit here safe and comfortable, and accuse others of being cowards.” [Camera switches toward other Parliament members who are sweating] “If you ask me, you are the coward, Little Miss Thing.”

Mizuko Kōhara: “What did you call me?”

Rory Mercury: “They faced a Flame Dragon and lived to tell the tales. So, you should offer them praise for pulling off such a feat, you demonstrate a rather creative way of manipulating numbers to look a certain way, don’t you? Your Self-Defense Force saved four hundred and fifty people.” [Camera switching out toward livestream on Tokyo main place; cutback of the events] “I can only imagine the problems that the soldiers in this country face if THIS is how they are treated.” [switchback to Rory] “Itami and his team accomplished something no one has ever done. And that is my answer to that stupid question of yours. Is that true enough for you, Little Miss Thing?” [Scene is cut by the visions of the American, Russian, and Chinese presidents who follow the trial via livestream] (23:42)29

Mizuko, a member of the Japanese Parliament, is the archetype of politician in Gate. Even if she has never been to the Special Region, she holds a deep grudge against the military and is willing to blame them every chance she gets. She embodies a pacifist who is so eroded by hate against the military that she can no longer act with patience and is instead accusing the JSDF of acting cowardly. The element that is implemented in this scene is the paradoxical situation that Rory Mercury, a member of the Special Region with absolutely no affiliation to the JSDF, has to defend their actions and put them into the true light. Due to the series, she is portrayed as an angel of death, a servant to the Death God, so she has strong attachments and emotions regarding the fate of soldiers, which underlines an external flattery for the JSDF. The second element is the notion of deep distrust against official numbers, as she emphasizes the fact that even if people died, others had been rescued. The third element is the global perspective, where again the belligerent opponents of Japan’s government had to indirectly face the accusation of Rory, which is in a broader sense directed to all politicians who have no sense of the reality of war but are eager to let others bear the costs of it.

Altogether, Gate offers a great variety of scenes where those two key messages are being transmitted: first, the JSDF accomplishes tremendous achievements even in the face of the greatest danger, no matter the cost. The reason for those accomplishments is up-to-date technologies and a tight and disciplined military organization, which is oriented to defending Japan and its citizens, while having no expansionistic ambitions. Second, politicians cannot be trusted (except the minister of defense, as he is portrayed as a semisoldier), no matter if they are Japanese or foreign, as they will do anything that suits their personal interest. The contrasting juxtaposition of values (soldiers with common goals and politicians with selfish, individualistic goals) is a very concerning element in the series, as it opens a possible path to undermine a democratic core institution. It casts aspersions at politicians as a whole but presents the Army as the last democratic resort free from corruption, and a distorted picture of the reality is presented. Another minor issue is how the JSDF presents themselves as a cultural ambassador. In doing so, the armed forces make the people of the Special Region accustomed to Japanese values, tradition, and food, and even including local citizens in the military police—a fact that is absolutely contrary to the ongoing high racial discrimination in contemporary Japan.30 In exaggerating specific personal values and characteristics toward the audience, this series can serve as a prime example for a one-sided perception of cultural heritage and organizational values.

Analysis of Transformers 4: Age of Extinction

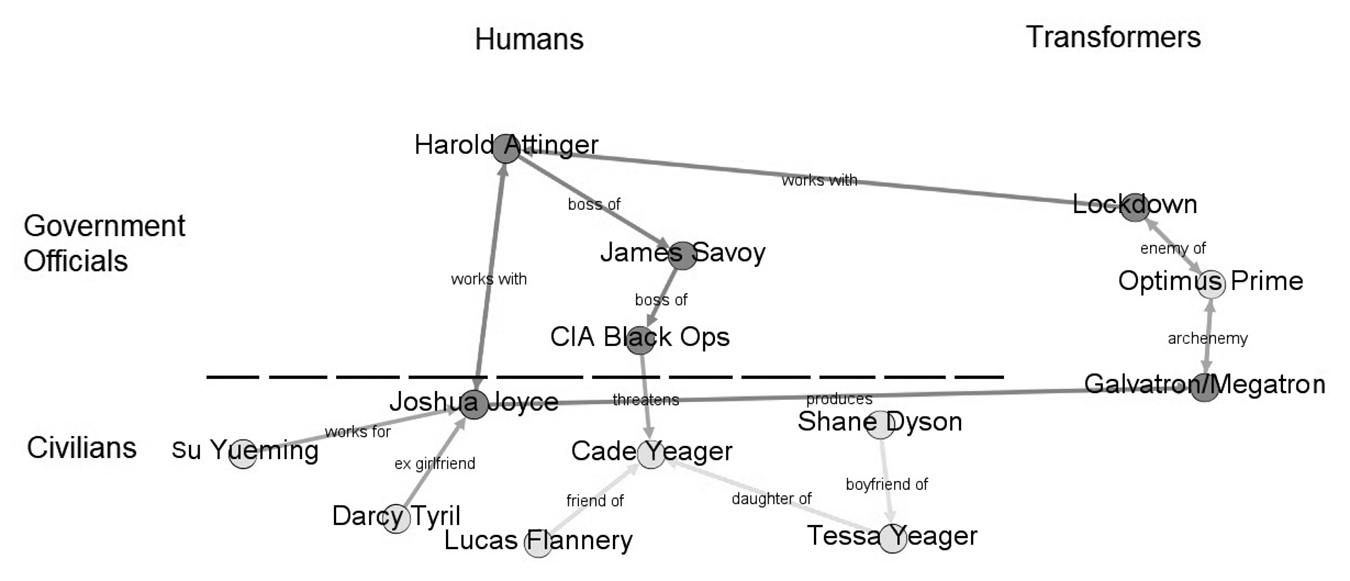

Contrary to Gate, Transformers: Age of Extinction (TF4) is a movie and therefore cannot offer the introduction of that many characters, plots, ploys, and intrigues. But out of the point of view of the author, it serves as another good example in dealing with propagandistic issues. As already mentioned, TF4 is a type of rogue movie (a kind of production that is per se critical to the government but not explicitly to the military) in the Transformers series, as it was the first who introduced a new human main character, but it is still relying on old Transformers, such as Megatron or Optimus Prime. Figure 2 briefly shows the relationships between the main actors of the movie. Initially, we can see a similar picture to the Japanese case example, as again from the civilian level no real threat (with the exemption of the corrupt designer Joshua Joyce) emerges.

Figure 2. Relationships in Transformers 4: Age of Extinction, illustrated with Network-Analysis (light gray=supporting main character; dark gray=adversaries to main character)

Source: Courtesy of author, adapted by MCUP.

The main synopsis of TF4 deals with where the plot of Transformers 3 left off, where an alien invasion almost destroyed the United States. Since then, Transformers are no longer welcome in the United States and face a deadly hunt against them by a Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) black ops team (which is already corrupted and has hijacked parts of the military; even if they do not represent the armed forces, they use them and therefore make them visible as an uncorrupted counterexample) while also being hunted by an adversary Transformer from outer space (Lockdown). The main human protagonist, Cade Yeager, stumbles accidentally into this twisted constellation and is then labeled persona non grata and has to confront himself with an ongoing conspiracy. Confronted with the already mentioned heavy Chinese influence in the movie, TF4 presents a semiofficial CIA unit called Cemetery Winds, which is an archetype of loyal, anonymous bureaucrats, putting the mission above all moral and legal aspects:

(37:09) James Savoy: “Mister Yeager. Excuse me.” [Takes off his black sunglasses] “You just said ‘him’.” [Looks directly into Yeager’s face] “Take him down!”

Cade Yeager: “What?” [Desperate music begins to play]

Tessa Yeager: “Let me go! Au!” [is being pulled off by CIA member]

Cade Yeager: “They don’t know about the truck. I know! Just let her go!”

James Savoy: “What kind of man betrays his brothers in flesh and blood and favors something in metal? Get this guy out of my sight!” (37:30)31

Savoy, portrayed as handmaiden of a higher authority (as he receives his orders via earplug from his boss Harold Attinger, the head of the CIA black ops), is, as are his fellows, completely dressed in black, symbolizing an anonymous, semifascist force that could have emerged from George Orwell’s masterpiece 1984. His loyalty to his superior has blinded him for reason and empathy, strictly carrying out commands he will obey without a doubt:

(1:11:19) Cade Yeager: “Look, I want a lawyer, the Justice Department, somebody I can really trust. I’m just trying to protect my family. Not from your company. From the government.” [Harold Attinger enters the room]

Harold Attinger: “Mister Yeager. Who do you think I work for?” [smiles] [Yeager stares at him] “You are trying to protect your family. That’s admirable. I’m trying to defend the nation. From alien war. We had a taste on how it looks like and we are not going to tolerate another.” [sits down in front of Yeager] (1:11:39)32

In portraying semiofficials like Attinger or Savoy as hypocrites (both have deals with Joyce’s company to retire and gain as much money out of his products as possible), they are immediately dismantled of their superior moral arguments that they are carrying like torchlights in front of them.

Important to note is the fact that the “official” military that shows up in the movie is never acting on its own but always under the auspices of Attinger or one of his subordinates (like at 1:15:03, when Attinger declares the Autobot intrusion a “CIA-military operation”). In doing so, the audience gets the impression that an already corrupt, cancer-like subdepartment is using the loyal military assets to carry out selfish tasks and is therefore neither to blame nor can it be accused of collaboration, as it was obviously betrayed during the chain of command. Again, as a rogue movie it has several aspects that declare it from the beginning as critical toward the official government, but even in such a precarious context the military remains free of any deliberately bad intentions and serves as a positive counterexample toward a corrupt and selfish secret organization that has always been suspicious by itself. A common notion of shadiness can be found in both case examples, as both—CIA and the Intelligence Officer Hideyo Komakado—are portrayed in a distrustful and creepy way.

Conclusion: Trust Politicians Only if You Must?

But what can be learned out of those case examples? As a matter of fact, both the series and TF4 have so much additional material that could be analyzed that it would fill a whole book. In this article, the main goal was to look beyond the presented fictional character and the scenes and try to figure out the main messages and ideas that are linked to cinematic products that have been produced under the eyes of the respective national militaries. Whereas Gate clearly serves a propagandistic aim to further boost the popularity of the JSDF, TF4 has been located in the category of rogue movies, a kind of production that is critical to the government, but not explicitly to the military, as it functions as an uncorrupted pure counterexample.

Both case studies have different cultural backgrounds and even their producing countries vary vastly, with the United States as a clear winner of the Second World War and currently a global power, while Japan lost the Second World War and suffered a national trauma with two atomic bomb attacks on Hiroshima and Nagasaki. But even if their history is incredibly contrary, their avenues of approaching cinematic productions are not. Both case studies clearly have shown that the primary threat to the military is not another armed force (as the JSDF could easily wipe out the whole Special Region and the Autobots had the Decepticons still under control), but merely domestic politicians opposing the armed forces, or rogue intelligence units that manipulate democratic institutions. Whether it was a cynical member of the Japanese Parliament who wanted to blame the JSDF at all cost, or an independent CIA unit that betrays the military and deliberately harms civilians alike, the threat never came out of the population or even from peers. Both productions used the scripted reality for creating a positive picture of the soldiers, its ethos, and duty toward the country, even if some of the protagonists had the chance for malpractice (e.g., Itami when a slave girl submitted herself to him). In portraying an admirable, trustworthy but somehow still down-to-earth picture of the national soldier, both productions gain support and backup for their soldiers, regardless of their tasks or missions.

National defense departments do not engage in cinematic production and sponsor them with generous grants, knowledge, and access to military installations without having an agenda: boosting the acceptance of their target audience. In both cases, this is done via different approaches; in the Japanese case, with a propagandistic one, in the American case, with a counterexample. Despite all the differences, efforts, and even outcomes of those two productions, they still remain at their core what they are created for: positive representations of the armed forces.

Endnotes

- Christopher Hughes, “The Erosion of Japan’s Anti-militaristic Principles,” Adelphi Papers 48, no. 403 (2008): 99–138, https://doi.org/10.1080/05679320902955278.

- The narration of security threats to Japan was part of the Japanese white paper to make defense policy more intelligible to a broader audience. Manga and anime productions were just one part of the communication strategy. Japanese Ministry of Defense, Defense of Japan (Tokyo: Japanese Ministry of Defense, 2019), 453; and Hughes, “The Erosion of Japan’s Anti-militaristic Principles,” 128.

- Takayoshi Yamamura, “Cooperation between Anime Producers and the Japan Self-Defense Force: Creating Fantasy and/or Propaganda?,” Journal of War & Culture Studies 12, no. 1 (2019): 8–23, https://doi.org/10.1080/17526272.2017.1396077.

- Kiyoshi Sugiyama, “Jieitai to Ōaraimachi, sonopaipuyaku to shite,” in Garupan shu zaihan, ed. Garupan no himitsu (Tokyo: Kosaido Shinsho, 2014), 30–41. High School Fleet’s reception was overwhelming, even in the Western Hemisphere. A fan website for American followers was started and computer games implemented the characters in their story, with the most prominent example World of Warships (a free-to-play massive multiplayer online game from Belarus with an estimated 1 million players).

- Akiko Sugawa-Shimada, “Girls with Arms and Girls as Arms in Anime: The Use of Girls for ‘Soft’ Militarism,” in The Routledge Companion to Gender and Japanese Culture, ed. Jennifer Coates, Lucy Fraser, and Mark Pendleton (London: Routledge, 2019), 391–98.

- Yamamura, “Cooperation between Anime Producers and the Japan Self-Defense Force,” 17.

- Jonathan McClory, The Soft Power 30. A Global Ranking of Soft Power (Portland, OR: Portland Communications, 2019); and Testimony, Hillary Rodham Clinton, Secretary of State, Secretary of State Statement before the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, 111th Cong. (13 January 2009) (nomination for secretary of state).

- Yee-Kuang Heng, “Smart Power and Japan’s Self-Defense Forces,” Journal of Strategic Studies 38, no. 3 (2015): 282–308, https://doi.org/10.1080/01402390.2014.100291. An example may show the creativity of the JSDF: “MOFA cooperated with the Japan Foundation and Anime International Middle East to cover the costs of airing Captain Tsubasa, a popular Japanese anime cartoon series, in Iraq. Captain Tsubasa featured the travails of a Japanese football team and its leader. Adjusting the program for different geographical and cultural contexts, the anime screened in Iraq was dubbed in Arabic and renamed Captain Majed.” Heng, “Smart Power,” 294.

- Sabine Frühstück, Uneasy Warriors: Gender, Memory, and Popular Culture in the Japanese Army (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2007); and Frühstück, “Uneasy Warriors,” 117.

- Akiko Sugawa-Shimada, “Playing with Militarism in/with Arpeggio and Kantai Collection: Effects of shōjo Images in War-related Contents Tourism in Japan,” Journal of War & Culture Studies 12, no. 1 (2019): 53–66, https://doi.org/10.1080/17526272.2018.1427014.

- Rumi Sakamoto, “Will You Go to War? Or Will You Stop Being Japanese? Nationalism and History in Kobayashi Yoshinori’s Sensoron,” in China-Japan Relations in the Twenty-First Century: Creating a Future Past?, ed. Michael Heazle and Nick Knight (Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar, 2008), 75–92.

- Eric Hobsbawm and Terence Ranger, The Invention of Tradition (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2010), https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781107295636.

- Paul Martin, “The Contradictions of Pop Nationalism in the Manga Gate: Thus the JSDF Fought There!,” Journal of Graphic Novels and Comics 11, no. 2 (2020): 167–81, https://doi.org/10.1080/21504857.2018.1540439.

- John A. Alic, “The Origin and Nature of the US ‘Military-Industrial Complex’,” Vulcan: Journal of the Social History of Military Technology, no. 2 (2014): 63–97, https://doi.org/10.1163/22134603-00201003.

- Matthew Alford, Reel Power: Hollywood Cinema and American Supremacy (London: Pluto Press, 2010).

- Sueyoung Park-Primiano, “Occupation, Diplomacy, and the Moving Image: The US Army as Cultural Interlocutor in Korea, 1945–1948,” in Cinema’s Military Industrial Complex, ed. Haidee Wasson and Lee Grieveson (Oakland: University of California Press, 2018), 227–40, https://doi.org/10.1525/9780520965263-015; and Alford, “Reel Power,” 83.

- Roberto J. González, “Introduction: Militarizing Culture,” in Militarizing Culture: Essays on the Warfare State (New York: Left Coast Press, 2010), 13–32, https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315424699.

- William Hamilton, “Toying with War,” Age, 4 May 2003.

- Alford, “Reel Power,” 82.

- Tanner Mirrlees, “Transforming Transformers into Militainment: Interrogating the DoD-Hollywood Complex,” American Journal of Economics and Sociology 76, no. 2 (2017): 405–34, https://doi.org/10.1111/ajes.12181.

- Kimberley Owczarski, “ ‘A Very Significant Chinese Component’: Securing the Success of Transformers: Age of Extinction in China,” Journal of Popular Culture 50, no. 3 (2017): 490–513, https://doi.org/10.1111/jpcu.12554.

- Harlan D. Wilson, “Technomasculine Bodies and Vehicles of Desire: The Erotic Delirium of Michael Bay’s Transformers,” Extrapolation 53, no. 3 (2012): 347–64, https://doi.org/10.3828/extr.2012.19.

- Hubert Knoblauch, Bernt Schnettler, and Jürgen Raab, “Video-Analysis: Methodological Aspects of Interpretative Audiovisual Analysis in Social Research,” in Video Analysis: Methodology and Methods. Qualitative Audiovisual Data Analysis in Sociology, ed. Hubert Knoblauch (Frankfurt am Main, Germany: Peter Lang Verlag, 2006), 9–28, https://doi.org/10.3726/978-3-653-02667-2.

- Knoblauch, Schnettler, and Raab, “Video Analysis,” 12.

- Hubert Knoblauch and Bernt Schnettler, “Videography: Analysing Video Data as a ‘Focused’ Ethnographic and Hermeneutical Exercise,” Qualitative Research 12, no. 3 (2012): 334–56, https://doi.org/10.1177/1468794111436147.

- Knoblauch and Schnettler, “Videography,” 335.

- The only exception is the case of Delilah, a barmaid and former assassin in the local restaurant of Alnus Hill. But even she was betrayed by Tyuule (political level) who gave her a fake order to kill a local Japanese citizen. After being stopped by the military police, she fell in love with a Japanese officer and finds a happy ending.

- Gate: Jieita iKanochinite, Kaku Tatakaeri (Dub), season 1, episode 6, “Ride of the Valkyries.”

- Gate: Jieita iKanochinite, Kaku Tatakaeri (Dub), season 1, episode 8, “Japan, Beyond the Gate,” Takahiko Kyōgoku.

- Minami Funakoshi, “Foreigners in Japan Face Significant Levels of Discrimination, Survey Shows,” Reuters, 31 March 2017.

- Transformers: Age of Extinction, directed by Michael Bay (Hong Kong: Paramount Pictures, 2014).

- Transformers.