Andrew Rhodes

https://doi.org/10.21140/mcuj.20201102002

PRINTER FRIENDLY PDF

EPUB

AUDIOBOOK

Abstract: American officers considering the role of the sea Services in a future war must understand the history and organizational culture of the Chinese military and consider how these factors shape the Chinese approach to naval strategy and operations. The Sino-Japanese War of 1894–95 remains a cautionary tale full of salient lessons for future conflict. A review of recent Chinese publications highlights several consistent themes that underpin Chinese thinking about naval strategy. Chinese authors assess that the future requires that China inculcate an awareness of the maritime domain in its people, that it build institutions that can sustain seapower, and that, at the operational level, it actively seeks to contest and gain sea control far from shore. Careful consideration of the Sino-Japanese War can support two priority focus areas from the Commandant’s Planning Guidance: “warfighting” and “education and training.”

Keywords: Sino-Japanese War (1894–1895), China, seapower, naval history, naval strategy, People’s Liberation Army, Qing Dynasty

Few Americans reflect on the operational and strategic lessons of the Sino-Japanese War of 1894–95, despite that it marks the “birth of the modern international order of the Far East.”1 For Chinese strategists and historians, this first Sino-Japanese War remains a major focus of study and a source of cautionary tales about contending for regional power and employing a navy. Indeed, 1894 was the last time China had a world-class navy: now that the People’s Liberation Army Navy (PLAN) has gained international prominence, Chinese navalists have justifiably given new attention to this chapter in China’s naval history. Every nation and military Service has its own strategic culture that shapes the way contemporary issues are analyzed through historical analogy. Some of these strategic narratives are a deliberate effort to fit history conveniently to current issues, but the prevailing narrative, whatever its origins, still shapes decision making. Technological change is a major aspect of changes in the character of future naval warfare, but equally important are the stories that a Service tells itself, for these help determine choices on force design and the development of operational concepts.

This article will begin with a brief review of the maritime aspects of the 1894–95 conflict, followed by a summary of the initial conclusions that American naval officers drew from the conflict at the time, reminding American readers that this should not be an obscure conflict for the sea Services. The following section will seek to broaden American understanding of the importance of the Sino-Japanese War by reviewing recent Chinese naval and academic writing on the conflict that have not previously been translated or widely studied in the United States. Finally, the article will offer some conclusions about the key themes that emerge after studying some examples from this body of Chinese-language literature. These writings indicate that, for Chinese strategists and naval officers, the Sino-Japanese War remains an important and salient case study for thinking about the role of seapower in peacetime and in war. The Commandant’s Planning Guidance calls for correcting insufficient “discussions on naval concepts, naval programs, or naval warfare” and strengthening the presence of a “thinking enemy” in wargaming.2 The sea Services’ planners and educators should devote further study to the Sino-Japanese War and, most critically, how this history might shape future Chinese decisions.

A Brief Review of the Sino-Japanese War of 1894–95: The Naval Campaigns

The Sino-Japanese War of 1894–95 (also known as the “Jiawu War” in China, the “Japan-Qing War” in Japan, or the “First Sino-Japanese War”) was much more than a victory of modernizing Japan over declining China. The war is best remembered for the naval battles in which the new Imperial Japanese Navy destroyed China’s naval forces, which proved much less effective than most observers had anticipated. To appreciate the influence of this conflict on Chinese naval thinking today, it is important to put the conflict in a broader context than the tactical and operational explanations of Japan’s superiority at sea.

The war began as a contest for control of the Korean Peninsula, where China had long been the dominant player. The unrest brought about by the 1894 Tonghak Uprising prompted Japan to challenge China’s sphere of influence. Both China and Japan landed troops and sought to use their navies to secure harbors on the west coast of Korea and control the sea lanes through the Yellow Sea. China had invested substantial resources in modernizing its naval forces during the decade leading up to the war and was eager to erase the shame of its naval defeat in the 1884 Sino-French War. However, on the eve of the conflict in Korea, China really had four navies without unified control: the force operating in northern Chinese waters, the Beiyang Fleet (northern ocean fleet), was not only the most modern of China’s squadrons, but it was among the most powerful fleets in the world. It had a number of modern warships recently built in European shipyards, and their Chinese crews had impressed foreign observers during maneuvers.3 The Beiyang Fleet fell under the direct control of Viceroy Li Hongzhang, a senior Qing official and one of the leading figures supporting modernization in the late Qing period, who also controlled some of the key land forces in northeastern China. The other Qing fleets, and the diverse array of mismatched units that made up China’s Army, were manned, trained, and equipped separately and beyond the control of Li Hongzhang. This arrangement was typical of the multiethnic Qing state, in which an ethnic Manchu ruling dynasty administered a vast empire gained by conquest through an array of separate local forces.

The first naval battle of the war took place in the summer of 1894 near Pungdo Island (a.k.a. Feng Island) in the approaches to the Korean port of Asan. Japanese forces had taken control of the port at Incheon (Chemulpo) and occupied Seoul, demanding the withdrawal of a Chinese army encamped to the south at Asan. War had not yet been declared when Chinese ships with reinforcements approached Asan on 25 July 1894 and the Japanese fleet attacked, sinking a critical transport and damaging multiple combatants. The Japanese Army then defeated the unreinforced Chinese troops several days later and marched north to Pyongyang. After the Battle of Pungdo Island and the defeat at Asan, the Qing court demoted Li Hongzhang and issued strict orders to the Beiyang Fleet not to sail east of the tip of the Shandong Peninsula. In September, Japan won undisputed control over Korea, defeating the Chinese on land at Pyongyang and on sea at the mouth of the Yalu River.

The 17 September 1894 Battle of the Yalu (also known as the Battle of the Yellow Sea) was the pivotal naval engagement of the war and remains a salient example for Chinese authors on naval issues. The battle also put the world on notice that Japan had emerged as a naval power. Foreign observers at the time wrote extensively about the tactical and operational aspects of the battle between two heterogeneous fleets: 12 Chinese ships against 11 Japanese.4 Each side had its strengths and weaknesses, and it was not clear at the time which was the favorite.

Subsequent historians have debated the specifics of how the faster Japanese fleet prevailed over the heavier Chinese ships, despite having smaller ships with less armor, by maneuvering in well-coordinated columns and devastating its enemy with sustained, well-aimed fire.5 The battle also highlighted many tactical deficiencies on the Chinese side, including inferior formations, breakdowns in command and control, poor-quality munitions, and inadequate damage control.6 This last point was particularly damning, as the Japanese ships’ key advantage over the Chinese was in quick-firing guns that killed crews and started fires without necessarily dealing the devastating blows of the heavier battleship guns. China’s battleships—the Dingyuan (1881) and the Zhenyuan (1882)—were larger and more heavily armed than any of the Japanese ships but had been unable to bring their heavy guns to bear on the enemy. The two battleships escaped to Port Arthur, but the Japanese destroyed five ships of the Beiyang Fleet while losing none of their own.

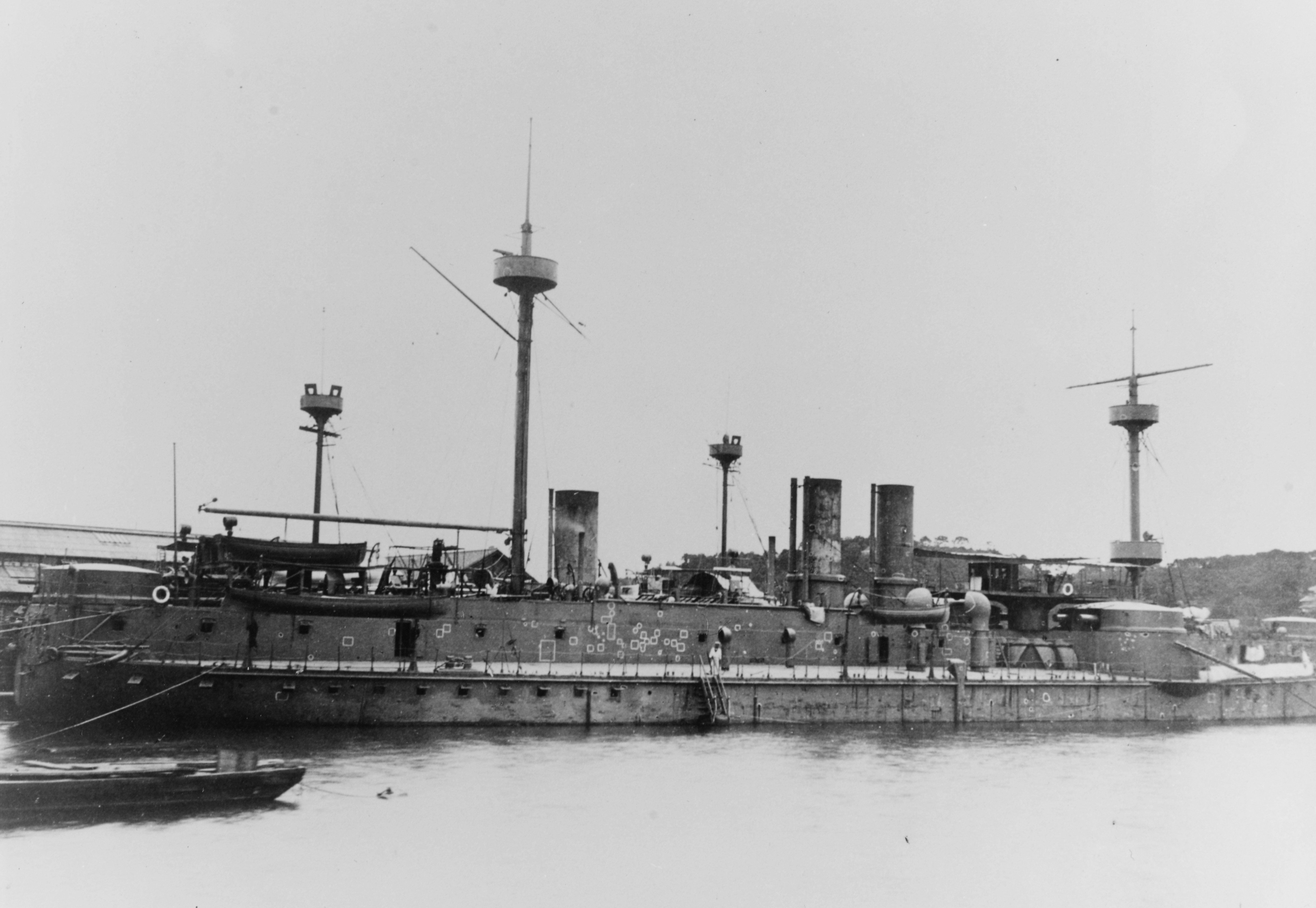

Figure 1. The Dingyuan, the pride of the Beiyang Fleet, was built in Germany in the 1880s

This predreadnought battleship was larger (more than 7,000 tons), more heavily armored, and mounted heavier armament (two turrets of twin 12-inch guns) than any ship in the Japanese Navy when war broke out. A replica of the Dingyuan, built in 2003, is one of main attractions at a museum in Weihai that commemorates the Beiyang Fleet and the Sino-Japanese War.

Source: Naval History and Heritage Command, NH 1926.

After the Battle of the Yalu, the remnants of the Beiyang Fleet remained at Port Arthur, giving Japan a free hand for amphibious landings on the Liaodong Peninsula in support of Japanese forces invading Manchuria from Korea. The day before the Battle of the Yalu, the Japanese Army defeated Chinese forces at Pyongyang and marched north to cross the Yalu and drove the Chinese Army back toward the Qing ancestral city of Mukden (Shenyang). The isolation or final destruction of China’s remaining naval forces would further allow the Japanese to sail unopposed into the Bohai Gulf and put amphibious forces ashore near Tianjin or Shanhaiguan for a short march to Beijing. Japanese ships landed on the Liaodong Peninsula at the end of October and within weeks enveloped Port Arthur, China’s most important naval base and shipyard, from the landward side. The diminished and defenseless Beiyang Fleet then fled south to Weihai on the Shandong Peninsula.

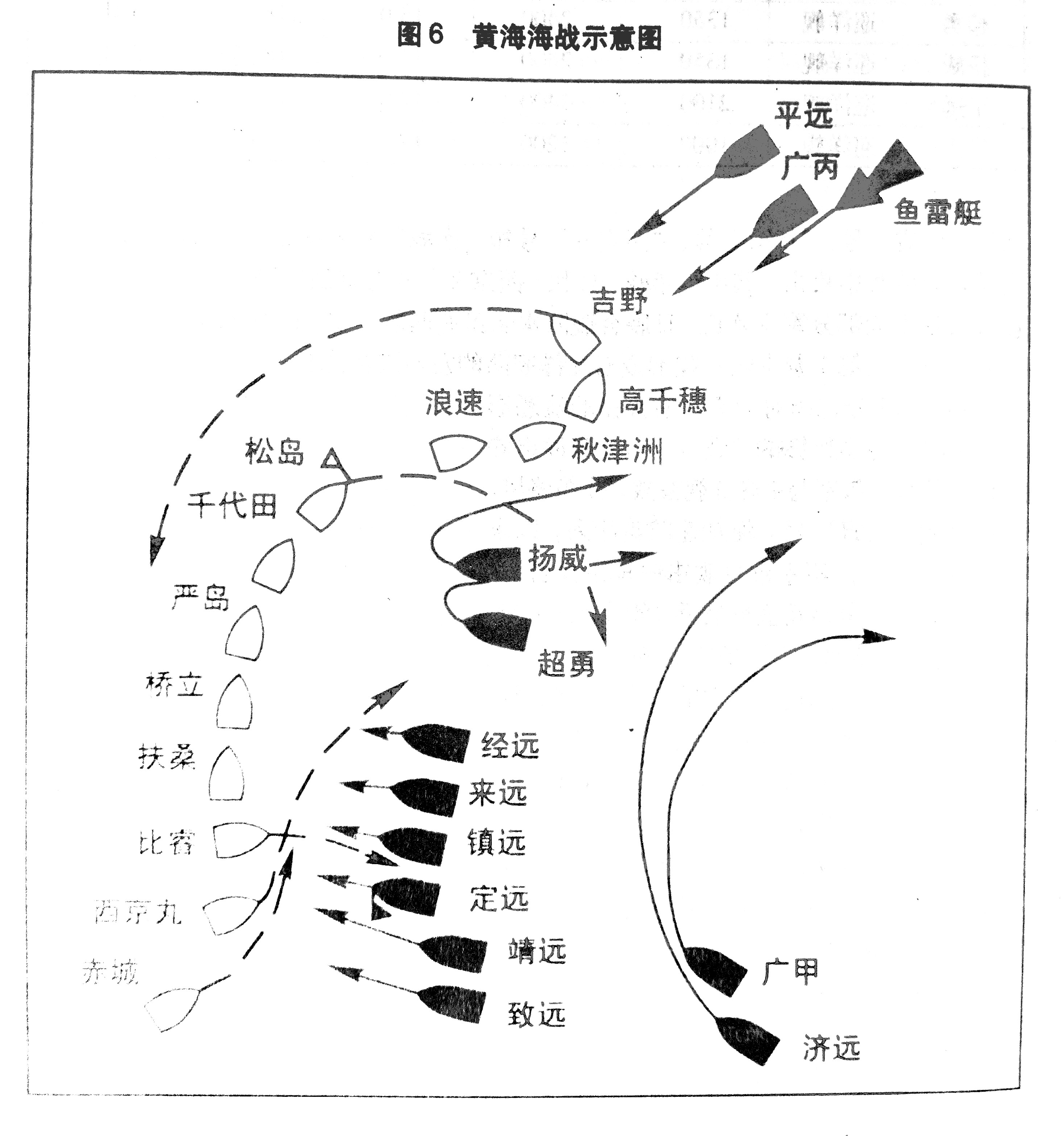

Map 1. Diagram of the Battle of the Yalu

This diagram of the battle came from a 2009 PLA-published military history textbook. Chinese officers study the strategic as well as operational lessons of the Sino-

Japanese War.

Source: Courtesy of the author, adapted by MCUP.

The Japanese now enjoyed uncontested control of the Yellow Sea and were able to divide the army in Manchuria, embark an amphibious force at Dalian, and land it in Shandong. The Japanese fleet made a diversion to the west of Yantai, patrolled the coast, and placed mines to keep Chinese warships inside the Weihai harbor. The Japanese Army went ashore without resistance in late January 1895 on the tip of the Shandong Peninsula and marched west through the snow to encircle Weihai. Within two weeks, the defenses of Weihai crumbled under the combined attack of the Japanese Army and Navy: the city fell on 12 February 1895, and the Japanese captured or destroyed the remaining ships of the Beiyang Fleet in the harbor.7 The flagship, Dingyuan, was scuttled, while the Zhenyuan became part of the Imperial Japanese Navy for the next two decades and fought at the Battle of Tsushima in 1905.

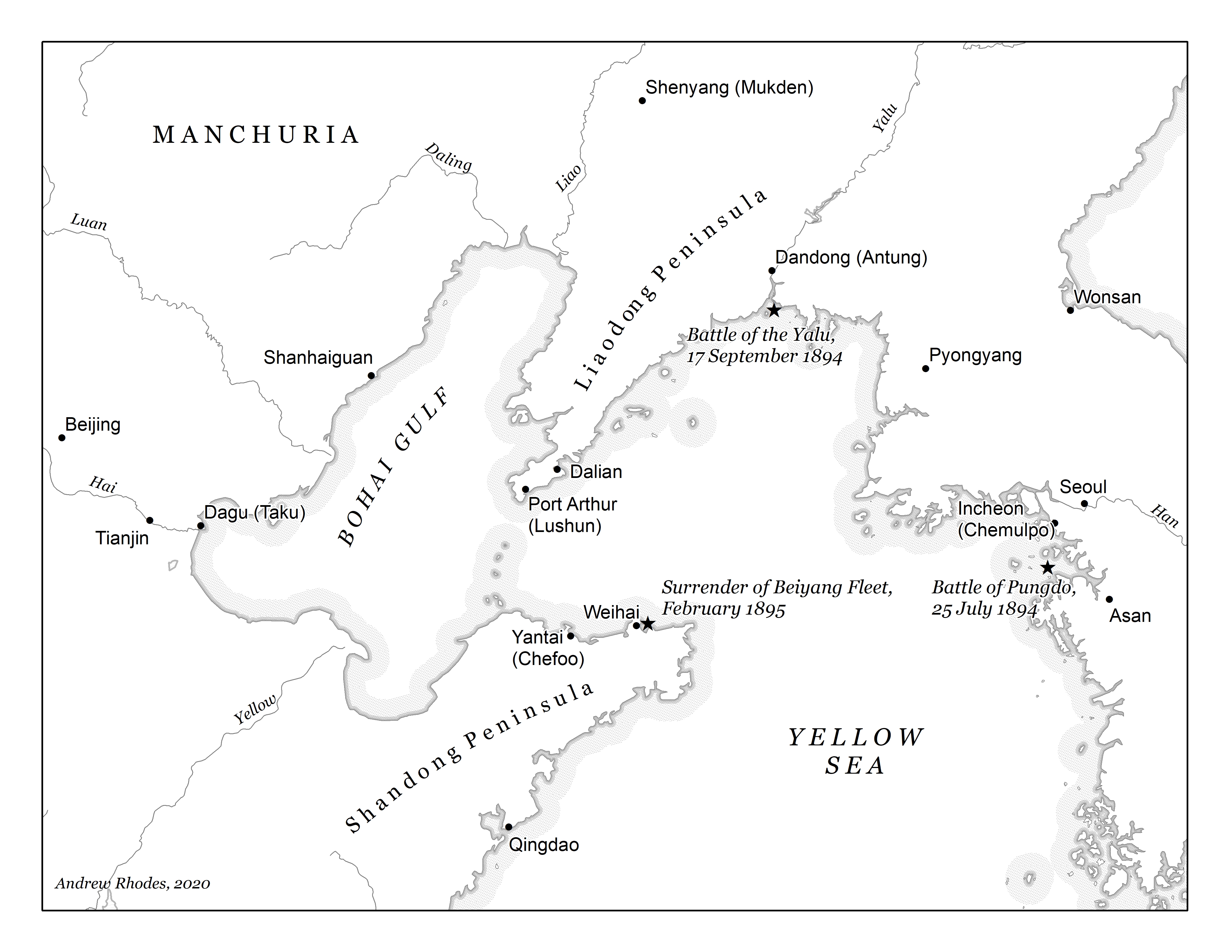

Map 2. Key locations in the Sino-Japanese War of 1894–95

Source: Created by the author.

Now utterly defenseless, the Qing court entered peace negotiations at the Japanese town of Shimonoseki and agreed to a treaty of massive concessions, including Japanese control over Korea, a major financial indemnity, new commercial rights for Japanese business, and the cession to Japan of the Liaodong Peninsula, the island of Taiwan, and the nearby Penghu Islands. Japan’s lopsided victories and the terms of the Treaty of Shimonoseki confirmed Japanese ascendance in East Asia for a global audience and set the stage for the Russo-Japanese War (1904–5), the next in a series of contests for regional dominance.

Forgotten American Perspectives on a Forgotten War

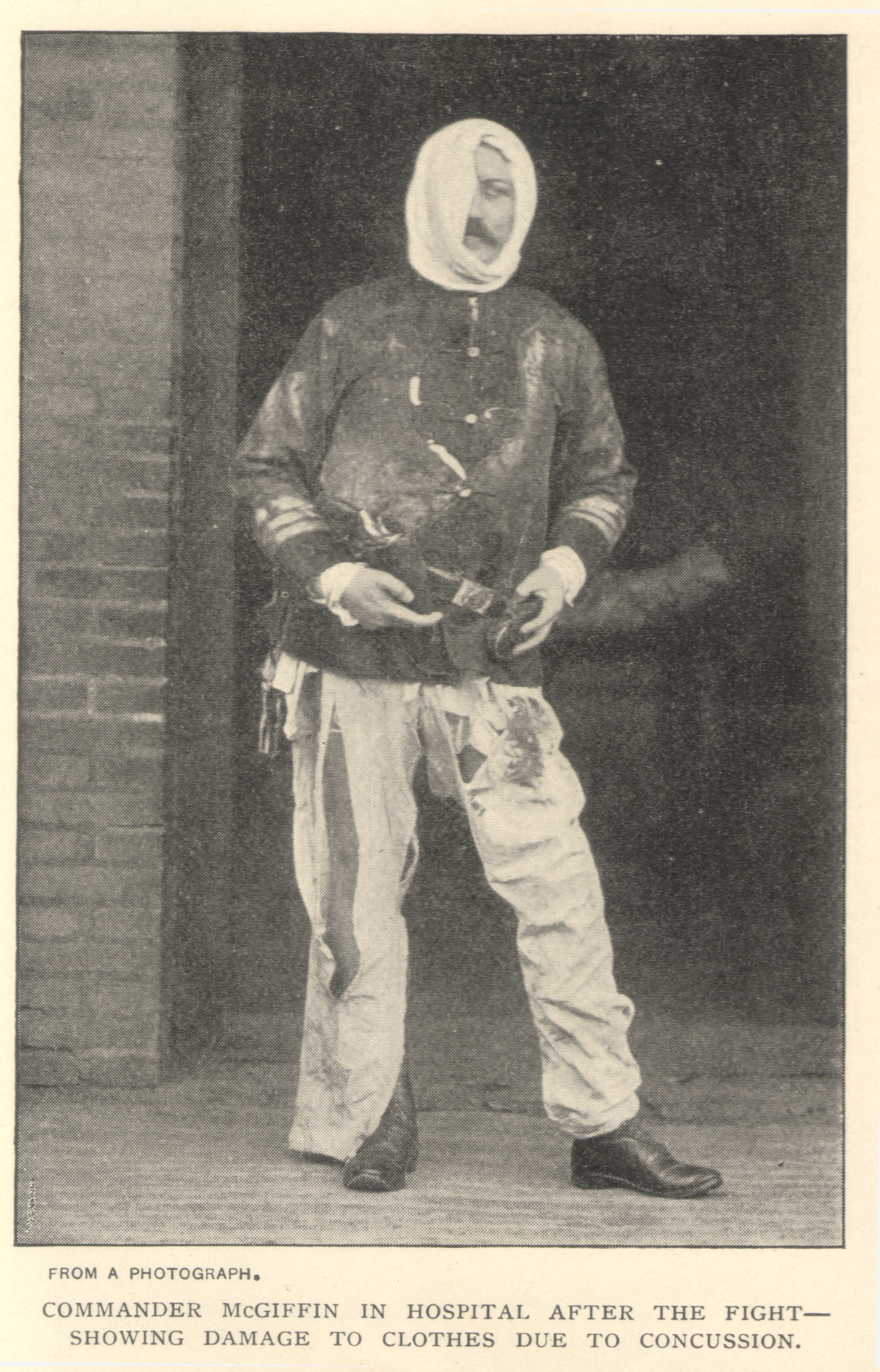

The naval battles of 1894–95 may seem obscure to Americans today, but they were carefully analyzed by American naval officers just after the war. Few American strategists or military officers studied Chinese institutions, culture, and language at the time, and these studies tended to fixate on the tactical and operational implications of the conflict, in part, because American perspectives on the naval conflict were initially shaped by the dramatic eyewitness accounts of foreign observers like Philo N. McGiffin, a legendary Annapolis graduate serving several years as an advisor in the Beiyang Fleet. When the commanding officer of the Zhenyuan was incapacitated at the Battle of the Yalu, McGiffin took command of the battleship through the thick of the fighting, becoming badly wounded himself.8 In 1895, the U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings published an analytical article on the battles by Ensign Frank Marble, drawing on the published accounts of McGiffin and a few European observers.9

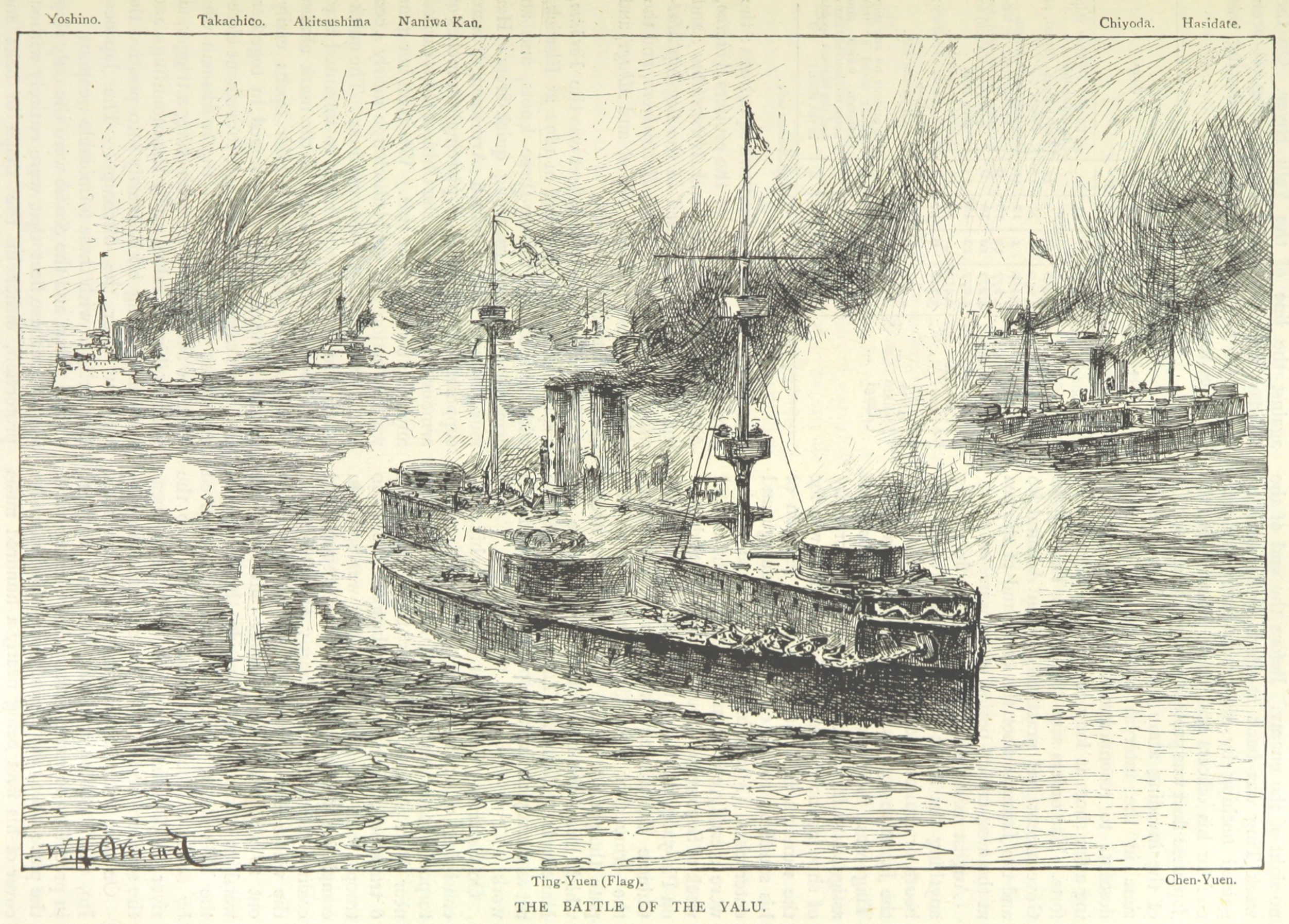

Figure 2. Engraving of the Battle of the Yalu

Source: Courtesy of the British Library.

Figure 3. American officer Philo N. McGiffin after the battle

Source: Published in McGiffin’s 1895 article in Century Illustrated.

Marble’s article prompted several officers to respond in Proceedings, including Lieutenant William F. Halsey Sr., who added several points in support of Marble based on his own experience in the Asiatic Fleet. Halsey noted that “the usual dash and nerve, so characteristic of the Japanese nation, was apparent everywhere,” and presumably inculcated the same respect for the Japanese in his son, Admiral Halsey. McGiffin’s articles published in the United States and England provided the first draft of English language history of the battle and prompted Alfred Thayer Mahan to publish a commentary of McGiffin’s account.10 Mahan’s 1895 analysis of the battle considered the experience of Beiyang Fleet commander Ding Ruchang as “one of the commonest and most deplorable experiences of a war—the hands of a commander-in-chief, present on the scene of operations, tied by the positive instructions of a man, or set of men, at a distance.”11 Secretary of the Navy Hilary A. Herbert agreed, noting that “China should have brought on a battle at her own time and in her own way.”12

Notwithstanding the operational commentary of these senior U.S. officials, Ensign Marble ended his analysis with a more strategic argument that remains highly salient today. Marble’s concluding paragraph includes a note of caution for Western analysts who tended to dismiss the fighting qualities of Asian navies, credited European-produced arms with decisive advantages, or believed in their superiority over the still-young Chinese and Japanese naval Services. Marble rebuked such analyses as “ludicrous,” recalling centuries of military tradition in Japan, noting that Westerners should acknowledge that Asian officers could also be “masters of their art” and reminding readers that the art of war belongs “not to one nation nor to one age.”13

As Sally Paine points out, scholarship of the war in English since these initial accounts has been sparse and told mainly from a Japanese perspective, as the victorious Japanese wrote much of the history, and the failing Qing state was not eager to publicize its shame. As an event in naval history, the naval war was soon eclipsed internationally by the Russo-Japanese War and the Battle of Tsushima.14 Paine filled a major void in 2003 with her book, the first history of the war in English making use of original archival material in Chinese, Japanese, and Russian. James Holmes, Paine’s colleague at the Naval War College and a noted author on Chinese naval thought, has also written several recent articles about the conflict, calling for Americans to remember McGiffin’s legacy and pay greater attention to a conflict that is well-remembered by Chinese strategists.15

Current Chinese Perspectives on a Newly Relevant War

The PLAN does not trace its origins to the Qing Navy or the Beiyang Fleet; the PLAN is the naval arm of the PLA, and therefore the navy of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP). The PLAN is not China’s national navy, with no direct tie to the navy of a feudal monarchy. The Qing Dynasty represented a pinnacle of corrupt feudalism and foreign domination that the CCP has sought to eradicate. Given the history of the late Qing period and the outcome of the war, it is in many ways remarkable that the PLAN would memorialize the navy of the vilified Qing Dynasty and a disastrous naval defeat. However, the Sino-Japanese War is a key part of the CCP’s narrative of grievance about a “century of humiliation” and the party leadership does draw, when convenient, on historical episodes that highlight the greatness of China’s ancient civilization. In addition to promoting the CCP’s version of modern Chinese foreign relations, elaborating the CCP’s version of Qing history helps to justify the party’s claim to have inherited sovereignty over regions that the pluralistic Qing empire actually won through conquest, not through cultural coherence.16

The resurgence in Chinese study of the Sino-Japanese War is owed, in part, to a variety of commemorative activities surrounding the 120th anniversary of the conflict in 2014. The PLA leadership held a major event at Weihai in August 2014, including speeches reflecting on the war by two members of the Central Military Commission.17 Scholars held conferences and published their papers in collections of the conference proceedings, although few of these papers have circulated outside of China or translated into English. Outside of military and academic settings, the anniversary was also set up by a 2012 mass-market film, The Sino-Japanese War at Sea 1894, which recreated the battles with sympathetic depictions of the Chinese naval officers who had studied abroad, built up the Beiyang Fleet, and did their best to fight the Japanese despite the failures of the Qing court. China’s leading scholar of the Sino-Japanese War, Qi Qizhang, served as a historical advisor during filming. The film won some awards at the Shanghai International Film Festival, though the acting and special effects are unremarkable.18

One of the most important commentaries on the 120th anniversary—and one of the few that has been translated—was that of Admiral Wu Shengli, the PLAN commander at the time and a major driver of naval modernization during his decade overseeing the force. In a 2014 article in a PLA professional journal, Wu called on his officers to study the lessons of the Sino-Japanese War as a conflict “in which both sides’ navies were central, and in which victory was won through naval battles.”19 American officers would also benefit from following Wu’s advice. Several previously untranslated writings by current PLAN officers and Chinese historians echo the same lessons that Wu emphasized. In particular, they highlight: the pitfalls of “weak ocean consciousness,” the importance of building institutions to support a navy, and the imperative to employ the navy actively and aggressively in combat.20

Recent Chinese writings examined for this article emphasize the importance of “sea consciousness” (haiyang yishi, 베捏雷街) or “awareness of seapower” (haiquan yiyi, 베홈雷街) among the population as a critical aspect of the nation’s maritime power.21 The contemporary Chinese Communist narrative of Qing seapower argues that, on top of other failings of the corrupt dynasty, society under the Qing had no connection to the sea, leaving it unable to recognize China’s maritime interests and the critical linkage between seapower and great power status. Qing China lacked a merchant class who relied on overseas trade and would represent these interests before the imperial court: even in authoritarian systems like Qing China, the case must be made to the people that the government must use its workforce and resources for something as ambiguous as “maritime rights and interests.” Gong Yun and Yang Yurong, from the Naval Engineering University, pointed out in 2014 out that the Qing “had no interest in the maritime economy due to their stable income from the land . . . and were short-sighted and conservative in naval construction.”22 Three PLAN officers in 2016 argued that China still lacks sufficient “maritime consciousness” and lags behind Japan in this area 120 years after the defeat of the Beiyang Fleet. They note by contrast that Japan makes “Ocean Day” a national holiday and national education policy inculcates children from kindergarten on the importance of the sea to the nation.23 The CCP leadership’s commitment to maritime power has been highly evident in the last decade, although CCP hardliners and civil society alike have sought to enhance the maritime character of China since the 1980s.24 Calls for China to turn its back on the Yellow River culture and engage in the international maritime economy were widespread in the period of openness before the 1989 Tiananmen Square Massacre, but such arguments now appear in authoritative CCP documents.25 As Wu wrote in 2014, the Qing were defeated because “they still clung to the traditional thinking of valuing the land and neglecting the sea.”26

The second key lesson highlighted in recent Chinese articles is the importance of peacetime institutions who undertake the work of building up a powerful navy “commensurate with the status of a maritime power.”27 Contemporary China is obviously more powerful and unified than under the inchoate and divided Qing, and modern China’s level of institutionalization has allowed it to pursue the buildup of a world-class fleet on a far more stable footing than the Qing enjoyed. Several recent Chinese authors explicitly identify as a decisive advantage the institutional support for the Imperial Japanese Navy after the Meiji Restoration. By contrast, they note the naval investments of the Qing were fractured, inefficient, and hidebound.28 At the most basic level, the PLAN has benefited from stable finances and substantial budget growth since the 1980s: indeed, China’s defense white papers more than 15 years ago called for an explicit bias in budgetary support for the navy.29 More recently, the 2015 China’s Military Strategy, a defense white paper, called for China to abandon the “traditional mentality that land outweighs sea.”30 This balance is exactly the opposite of the Qing’s commitment to its various Manchu and Han armies over naval forces like the Beiyang Fleet. Institutionalization has also given the PLAN a solid foundation for training, education, and acquisition. In stark contrast to the 1890s, and in some ways in contrast to the 1990s, today’s PLAN does not rely on foreign technology or expertise: it can train its own personnel, educate its own officers, and build its own ships and state-of-the-art weapons. But contemporary authors do not just indict the Qing for misallocating resources; they label Qing finances as “corruption,” the most grievous crime for Chinese officials in the Xi Jinping era. Much of this corruption discussion was de rigueur for any senior PLA official in 2014. Fan Changlong’s speech at the August 2014 commemorative conference included obligatory warnings about the Xu Caihou and Gu Junshan corruption cases. Nevertheless, the resonant narrative for today’s Chinese officers is that their predecessors perished in 1894 because of malfeasance in Beijing, not just their performance at sea.

The third salient lesson in these articles is the importance of employing the navy actively and aggressively in wartime. This lesson is particularly important for some American planners or commanders who tend to think of the military challenge from today’s China as primarily a question of sea denial. While there can be no doubt that the PLA fields some of the most sophisticated sea-denial capabilities in history, Chinese planners are not bounded by a defensive sea-denial approach to future naval warfare. Chinese writers are remarkably consistent in stating that the Beiyang Fleet was too passive and stayed too close to shore: by failing to challenge the Japanese fleet for sea control they ceded the initiative. A military history textbook published by the PLA in 2009 (in which map 1 appears) noted that the major strategic failing of the Qing was pursuing a policy of passive defense (xiaoji fangyu, 句섐렝徒) in which it failed to “actively open up the maritime battlefield” and contest Japanese landings.31 Wu Shengli’s 2014 article argued that the Qing “thoughtlessly and passively [sought to] ‘protect their ships and restrain the enemy,’ emphasizing defense of seaports,” while the Japanese “placed emphasis on offensive combat at sea, using all their power to seize command of the sea, and taking the initiative in wartime.”32 The analysis of two officers from the PLAN Submarine Academy regrets that the Qing policy of “war avoidance (bizhanzibao, 긁濫菱괏) restricted the Beiyang Fleet from coming out, and ceded control of the Yellow Sea and the Bohai Sea.”33

Recent Chinese authors appear unanimous that Chinese ships in 1894 should have been allowed to take the fight to the enemy, despite Japanese advantages in areas like quick-firing guns. Liu Jin, a Chinese naval historian, wrote in 2017 on the importance of Julian Corbett’s works on naval strategy and reiterated the example of Qing passivity in the Sino-Japanese War. Liu argues that the restrictions dictated by the Qing court were simply passive and cannot be justified as an example of a “fleet in being” (cunzai jiandui, 닸瞳숱뚠) strategy.34 Such a strategy seeks the preservation of core naval force from attack but still retains an offensive object: some historians have cited the restrained Beiyang Fleet as an example. Liu further argues that an accurate interpretation of historical battles, including the Sino-Japanese War, is necessary for the correct employment of a “fleet in being,” which Liu assesses could be an appropriate strategy for the Chinese fleet to employ against the more powerful United States today.35

Conclusion

These lessons, drawn by Chinese authors about a conflict in Chinese waters more than a century ago, have relevance for American officers and strategists today. Military history is best used not as a source for answers for future conflict but as a means to ask better questions about the role of the sea Services and how to handle uncertainty in preparing for the future.36 In keeping with the Commandant’s Planning Guidance, American planners will find value in considering the historical analogies their Chinese counterparts use in discussing force design and operational concepts to prepare in peacetime for a “thinking enemy.” Neither the objective facts of the Sino-Japanese War, nor the subjective stories that the PLAN tells itself about that conflict, provide direct causal explanations for the naval programs the PLAN has pursued, nor can they reliably predict how the PLAN will behave in future conflicts. Nevertheless, the consistent narrative the PLAN tells itself about the Sino-Japanese War is an essential part of the story for those seeking to understand the modern Chinese perspective of China’s future as a maritime nation and a first-rate naval power.

Force design is a product of the military, government, and (in China’s case) party institutions that evaluate requirements and shape force development decisions. The expansion and modernization of the PLAN in recent decades indicates these institutions are dramatically different than those that produced the Beiyang Fleet in the waning days of the Qing Dynasty. The narrative outlined here on the Sino-Japanese War would reject a fleet architecture designed only for defense in the littorals, even in the age of long-range, shore-based antiship missiles. China began important steps toward a true oceangoing navy in the 1980s, and its commitment to developing a fleet with world-class, blue water combat capability has only deepened since the high command marked the 120th anniversary of the Sino-Japanese War. As the 2020 Department of Defense report to Congress on Chinese military power makes clear, the PLAN is already the world’s largest navy, surpassing the U.S. battle force in size, and has become a naval peer in many key capability areas.37 The naval competition of the early 1890s quickly breaks down as an analogy for the current competition, but it does bear remembering that the two newly built fleets that fought at the Battle of the Yalu were considered evenly matched until one greatly exceeded expectations while the other proved a great disappointment.

Like the Beiyang Fleet, today’s PLAN is a source of pride for the Chinese people and the CCP leadership, and the PLAN’s capital ships are symbols of service and national prestige. But neither the PLAN, nor the Beiyang Fleet, were built only for show, and the prevailing historical lens suggests that in a future conflict Chinese naval commanders should sail the fleet—including prized capital ships such as aircraft carriers—into harm’s way. Chinese leaders can argue, with some justification, that they have assimilated the war’s lessons on maritime consciousness and naval institutions, but the twenty-first century PLAN has not yet had the opportunity to demonstrate how it has assimilated the third of the salient lessons highlighted above: the active employment of the fleet. This third lesson on active defense in combat is perhaps the most intriguing, since it remains untested in practice. The consensus of the authors cited here suggests that, if they were in command in a future conflict, they would not restrain the fleet behind a geographic line, such as an island chain or an arbitrary meridian. As PLAN officers Liu Lijiao and Chen Wenhua wrote in 2018, “in the future . . . military operations will not be confined to the waters of the near seas . . . the strategic forward area must be pushed outward to defend against the enemy as far away as possible.”38 Further, if they were to apply the lessons of 1894–95 as laid out in these recent articles, they would seek to sail the fleet far from shore to take the fight to a superior adversary and contest control of the sea early in a conflict.

Chinese writings make clear that they still see the United States as a superior power and a likely future adversary. Commanders and planners on the side of that assessed adversary will have better options available to counter such a sortie in the future if they attain the “positional advantage,” “persistent forward presence,” and “long-range precision fire” called for in the Commandant’s Planning Guidance. But crafting the operational concepts for such a counter are unlikely to succeed unless they include a “thinking adversary” and consider all of the lenses through which that adversary views an operational problem, including the historic lens. The American sea Services would benefit from greater inclusion of these historical lenses, especially that of the Sino-Japanese War, in analyzing Sino-U.S. competition, educating officers, and crafting training scenarios. The PLAN of 2020 is better built, equipped, and manned than the Beiyang Fleet of 1894, but it remains an open question whether the PLAN would live up to high international expectations or, like the Beiyang Fleet, prove a grave disappointment when meeting a peer competitor in combat.

Figure 4. The Zhenyuan after the Battle of the Yalu

Source: Naval History and Heritage Command, NH 88889.

Endnotes

- S. C. M. Paine, The Sino-Japanese War of 1894–1895: Perceptions, Power, and Primacy (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2003), 9, https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511550188.

- Commandant’s Planning Guidance: 38th Commandant of the Marine Corps (Washington, DC: Headquarters Marine Corps, 2019).

- Paine, The Sino-Japanese War of 1894–1895, 154.

- Ens Frank Marble, “The Battle of the Yalu,” U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings 21, no. 3 (July 1895).

- David C. Evans and Mark R. Peattie, Kaigun: Strategy, Tactics, and Technology in the Imperial Japanese Navy, 1887–1941 (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 1997), 48.

- Paine, The Sino-Japanese War of 1894–1895, 181; Marble, “The Battle of the Yalu”; and Hilary A. Herbert, “Military Lessons of the Chino-Japanese War,” North American Review 160, no. 463 (June 1895): 692–93.

- Paine, The Sino-Japanese War of 1894–1895, 226–28.

- Philo N. McGiffin, “The Battle of the Yalu: Personal Recollections by the Commander of the Chinese Ironclad ‘Chen Yuen’,” Century Illustrated 50, no. 74 (July 1895): 585–604; and Alfred T. Story, “Captain McGiffin—Commander of the ‘Chen Yuen’ at the Battle of the Yalu River,” Strand Magazine, July 1895, 616–24.

- Marble, “The Battle of the Yalu.”

- Alfred Thayer Mahan, “Lessons from the Yalu Fight: Comments on Commander McGiffin’s Article,” Century Illustrated 50, no. 74 (July 1895): 629–32.

- Mahan, “Lessons from the Yalu Fight,” 629.

- Herbert, “Military Lessons of the Chino-Japanese War,” 690.

- Marble, “The Battle of the Yalu.”

- Paine, The Sino-Japanese War of 1894–1895, 372.

- James Holmes, “China and Japan Went to War 125 Years Ago (Beijing Is Still Trying to Reverse the Results),” National Interest, 28 November 2019; James Holmes, “What History Says about China’s Chances in a War with America,” National Interest, 5 August 2014; and James R. Holmes, “A Conflict for the Ages: The First Sino-Japanese War,” Real Clear Defense, 14 April 2015.

- James A. Millward, “We Need a New Approach to Teaching Modern Chinese History: We Have Lazily Repeated False Narratives for Too Long,” review of Klaus Mühlhahn, Making China Modern: From the Great Qing to Xi Jinping, Medium, 8 October 2020.

- “Taking History as a Mirror, Knowing Shame, Forging Ahead and Fulfilling the Chinese Dream,” trans. Andrew Rhodes, People’s Navy (Renmin Haijun, 훙췽베엊), 29 August 2014.

- “Shanghai International Film Festival: Best Feature,” China Movie Channel Media Award (2012), IMDB.

- Wu Shengli (喬價적), “Learn Profound Historical Lessons from the Sino-Japanese War of 1894–1895 and Unswervingly Take the Path of Planning and Managing Maritime Affairs, Safeguarding Maritime Rights and Interests, and Building a Powerful Navy,” trans. China Maritime Studies Institute, U.S. Naval War College, China Military Science (Junshi Kexue, 櫓벌엊慤옰欺), August 2014, 1–4.

- Wu, “Learn Profound Historical Lessons.”

- Gong Yun (묠旽) and Yang Yurong (煖圖휠), “Research on the Root of Defeat of Sino-Japanese War of 1894–1895 from an International Perspective,” trans. Andrew Rhodes, Journal of the Naval University of Engineering (베엊묏넋댕欺欺괩) 11, no. 3 (December 2014); and “Taking History as a Mirror.” For a nonmilitary and slightly older Chinese perspective, see Ma Zhirong (쯩羚휠), “Reconstructing Maritime Consciousness: Contemporary Thoughts on China’s Lost Sea Power (베捏雷街路居:櫓벌베홈촬呵돨君덜鋼옘),” trans. China Maritime Studies Institute, U.S. Naval War College, Journal of Ocean University of China (櫓벌베捏댕欺欺괩), no. 3 (2007).

- Gong and Yang, “Research on the Root of Defeat.”

- Sun Xianhong (建鉤븐), Liu Junling (증에 줬), and Li Haili (쟀베접), “Reflections on the Formation and Development of China’s Sea Power from the Sino-Japanese War,” trans. Andrew Rhodes, Peers (谿契), no. 3 (2016). The article notes the authors are assigned to the Naval Submarine Academy.

- Liza Tobin, “Underway—Beijing’s Strategy to Build China into a Maritime Great Power,” Naval War College Review 71, no. 2 (Spring 2018).

- Su Xiaokang and Wang Luxiang, eds., Deathsong of the River: A Reader’s Guide to the Chinese TV Series Heshang, trans. by Richard W. Bodman and Pin P. Wan (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1991).

- Wu, “Learn Profound Historical Lessons.”

- “Taking History as a Mirror.”

- Gong and Yang, “Research on the Root of Defeat”; and Sun, Liu, and Li, “Reflections on the Formation.” See also Wang Hongguang (珙븅밟), ed., Analyses of Classical Battles (Beijing: Military Science Press, 2009).

- China’s National Defense in 2004 (Beijing: State Council Information Office of the People’s Republic of China, 2004).

- China’s Military Strategy (Beijing: State Council Information Office of the People’s Republic of China, 2015).

- Wang, Analyses of Classical Battles, 984.

- Wu, “Learn Profound Historical Lessons.” Similar language on Li Hongzhang’s policy of protecting ships (baochuanzhidi, 괏눋齡둔) appears in Gong and Yun’s article, published some months after Wu’s speech.

- Sun, Liu, and Li, “Reflections on the Formation.”

- Liu Jin (증쐈), “Back to Julian Corbett: A Re-interpretation of the Fleet in Being Strategy,” Pacific Journal (格틱捏欺괩) 25, no. 2 (February 2017).

- Liu, “Back to Julian Corbett.”

- Geoffrey Till, “History, Truth Decay, and the Naval Profession,” Naval War College Review 72, no. 4 (Winter 2019).

- Military and Security Developments Involving the People’s Republic of China, 2020: Annual Report to Congress (Washington, DC: Office of the Secretary of Defense, 2020), ii.

- Liu Lijiao (증쟝슴) and Chen Wenhua (냈匡빽), “Theoretical Development of Naval Strategy since Reform and Opening Up and Implications for Today (맣몌역렴鹿윱베엊濫쫠잿쬠돨랙嵐섟쒔駱폘刻),” trans. by Ryan Martinson and Conor Kennedy at the China Maritime Studies Institute, U.S. Naval War College, China Military Science (櫓벌엊慤옰欺), no. 6 (2018): 59–65.