PRINTER FRIENDLY PDF

EPUB

AUDIOBOOK

Abstract: The Marine occupation of Haiti from 1915 to 1934 presented unique challenges due to social, political, economic, and religious factors. All these threads came together in the Marines’ attempts to curtail the practice of Voodoo. The religion’s hold on Haitians proved to be so strong that no analysis of the Marine occupation can be thorough without paying careful attention to Voodoo. Institutional histories of the Marine Corps and studies of the Marine occupation of Haiti tend to sidestep analyzing Voodoo in detail or to misconstrue its significance. Conversely, cultural histories of Haiti rarely incorporate sufficient explanations of the operational aspects of the occupations, nor do they dig deeply into the Corps’ archival sources. This article helps to fill the void by using the Marine activities and the Voodoo trials in the late 1920s as touchstones, analyzing several criminal prosecutions against Haitians for allegedly practicing Voodoo in that period. These cases underscore the rationale behind the Marines’ attempts to “stamp out” this religion as part of their mission to transform Haiti into a modern, democratic, civilized nation and illustrate how Marines too often failed to grasp that Voodoo could support stability rather than rallying the Haitian people against the American presence and disrupting the modernization process.

Keywords: Voodoo, Vaudou, Vodoun, Vodou, Voudu, Vaudoux, Voodoo trials, Haiti, Banana Wars, small wars, nation building, modernization, Haitian occupation, American intervention, Marines in Haiti, Dollar Diplomacy, Monroe Doctrine, Roosevelt Corollary, corvée system, Aux Cayes Massacre

Between 1898 and 1934, thousands of U.S. Marines deployed to several nations in Latin America and the Caribbean Sea in efforts to stabilize the region by military force. The Marines tried to create democratic institutions, bolster indigenous military forces, protect American investments, deter European intrusions, and quell indigenous rebellions. These interventions and ongoing occupations were grafted onto the Marine Corps’ institutional identity in what became known officially as small wars or more colloquially as Banana Wars. Among the deployments in the region, the occupation of Haiti from 1915 to 1934 presented unique challenges because of social, political, economic, and religious factors. All these threads came together in the Marines’ attempts to curtail the practice of Voodoo (Vodou in Creole).1 The religion’s hold on Haitians proved to be so strong that no analysis of the Marine occupation can be considered thorough without paying careful attention to Voodoo.

Institutional histories of the Marine Corps and studies of the Marine occupation of Haiti tend to sidestep analyzing Voodoo in detail or to misconstrue its significance. Conversely, cultural histories of Haiti rarely incorporate sufficient explanations of the operational aspects of the occupations, nor do they dig deeply into the Corps’ archival sources. Even in Hispanic history journals, few scholarly articles have focused on the Marine occupation. The same can be said of diplomatic histories of Haiti that offer relevant analyses of policies yet set aside the operations in the conflict.2

This article helps to fill the void by using the Marine activities and the Voodoo trials in the late 1920s as touchstones. After briefly surveying the history of Haiti between 1492 and 1915, this article turns to the circumstances that spurred the Marine occupation of Haiti. Next, an explanation of the intertwined violence, corruption, and exploitation in Haitian society provides context for Voodoo’s integral role in the Haitian way of life. This article then analyzes several criminal prosecutions against Haitians for allegedly practicing Voodoo in the late 1920s. These cases underscore the rationale behind the Marines’ attempts to “stamp out” this religion as part of their mission to transform Haiti into a modern, democratic, civilized nation.3 The conclusion reveals that the Marines too often failed to grasp that Voodoo could support stability rather than rallying the Haitian people against the American presence and disrupting the modernization process.

Haitian History and Voodoo Practices, 1492-18984

When Christopher Columbus made landfall on Hispaniola in 1492, he found a large tropical island lying to the east of Cuba in the Caribbean Sea. The nation of Haiti eventually comprised the western one-third of the Hispaniola. In the three centuries that followed, the Spanish and—after 1697—the French empires subjugated the indigenous peoples by force and imported hundreds of thousands of enslaved people from Africa to work on plantations growing the area’s primary cash crop, sugarcane. Lives were cheap in Haiti: slaves worked until they died, and then the Spanish or French purchased more to replace them.

Enslaved Africans brought several religions with them from Africa to Haiti, including Voodoo. This religion’s followers believed in unity of all creation and served their chosen loa (spirits) who, while not deities themselves, served the powerful god Bondye.5 Rituals and ceremonies included combinations of prayers, songs, banging drums, animal sacrifices, ancestor veneration, and spiritual possessions. In the last of these, people induced a trance state, as if possessed by the loa, who spoke and acted through them. The Haitians hoped their faith would attract loa, who in turn would bestow success on them. Voodoo remains important within Haitian culture into the twenty-first century. The religion helped the enslaved peoples to cope with their plights in life and galvanized their resistance against the Spanish, French, and eventually American Marines.6

Haiti underwent a major shift in 1789. Waves of bloody revolutions in France sent tremors throughout the French colonies. Meanwhile, Haiti’s already unstable society fractured along class, racial, political, religious, and occupational fault lines. The Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen roused free black and mixed-race Haitians to assert claims of equality with French citizens, regardless of race.7 Although these two groups represented a small fraction of the Haitian population, they owned much of the land and most of the slaves. Then in 1791, when rumors circulated that French King Louis XVI wanted to free slaves, a priestess (mambo) led a ceremony in which she called on enslaved Haitians to revolt, claiming this mandate came from Ogun, the Voodoo god of war. She stated that Ogun “orders revenge! He will direct our hands; he will aid us.” Then she added that slaves should “listen to the voice of liberty that speaks in the heart of all of us.”8

In recent years, scholars have noted a connection between practicing religious beliefs and fomenting political action. Religion professor Leslie G. Desmangles observes that Voodoo’s “rituals provided the spirit of kinship that fueled the slaves’ revolts against their masters.”9 Elsewhere, black studies scholar Claudine Michel argues that Voodoo provided a “unifying force” and a “catalyst for the revolutionary accomplishments for which Haiti is known.”10 Those beliefs translated into a violent insurgency against the French colonial government. Haitian slaves, according to historian Philippe Girard, joined the revolt and fought the French by “relying on the support of sympathetic locals; making the best of a rugged terrain; and refusing pitched battles with a superior enemy.” Girard then avows that “centuries before Che Guevara and Ho Chi Minh, Haiti’s black rebels had perfected all the principles of modern guerrilla warfare.”11 The fighting lasted until 1803 when the Haitians finally defeated French colonial forces. In 1804, the Haitians declared their independence from France, claimed to be the sovereign Empire of Haiti, and thus followed the United States of America as only the second colony in the Western Hemisphere to throw off European colonial rule. Despite high hopes for freedom, the two centuries since Haiti won its independence never saw real democracy or equality develop. Instead, for the next century, revolutions and anarchy reigned when despots did not.

American Interventions in Latin America,1898–1935, and Haiti, 1915–34

A victory against Spain in 1898 enabled the United States to absorb the Spanish Empire’s territories, thereby asserting hegemony over nations in Latin America and the Caribbean. Suddenly, the United States joined the European nations as one of the great powers with colonies around the globe. Closer to home, Americans claimed the role of protector of the Western Hemisphere when President Theodore Roosevelt articulated an updated corollary to the Monroe Doctrine of 1823. This term doctrine is not used in a military sense, but rather denotes a set of diplomatic policies. President James Monroe’s original doctrine forbade Europeans from colonizing or interfering in the Western Hemisphere because he claimed this region as part of the American sphere of influence. Nearly a century later, Roosevelt’s Corollary in 1904 gave the United States the auspices to expand commercial interests in Latin America and protect those interests by force against indigenous or European threats. As Roosevelt’s successor from 1909 to 1913, President William Howard Taft continued the Corollary in Latin America and gave it the moniker: “Dollar Diplomacy.”12

Next came President Woodrow Wilson, who stated in 1913, “I am going to teach the South American republics to elect good men!” Although he ostensibly referred to Mexico, the statement applied throughout Latin America and the Caribbean.13 Always the idealist and progressive, Wilson believed that the United States could export democracy, freedom, and civilization to other nations overseas. If taught American virtues, then the people of Latin America would embrace American institutions. Prosperity for the indigenous populations and American businesses would follow as byproducts of Wilson’s decisions. If necessary, the use of military force could be one means to attain Wilson’s progressive vision in Latin America. During the years, several scholars, including the eminent historian William E. Leuchtenburg, equated progressivism with imperialism. Leuchtenburg argued that “imperialism and progressivism flourished together because they were both expressions of the same philosophy of government, a tendency to judge any action not by the means employed but by the results achieved . . . and almost religious faith in the democratic mission of America.”14

The Gendarmerie d’Haiti (later Garde d’Haiti) headquarters at Saint-Louis-du-Sud, Haiti, after a hurricane, August 1928. Official U.S. Marine Corps photo, Historical Reference Branch, Marine Corps History Division

Haiti, October 1933. Iron bridge across the LaQuinte River, about 3 km from the town of Gonaives, Haiti, one of the many bridges constructed in Haiti with an assist by U.S. Marine Corps forces and the Marine-trained Garde d’Haiti. Official U.S. Marine Corps photo 51627, by 1stLt L. N. Bertol, Historical Reference Branch, Marine Corps History Division

Apart from systemic political unrest and economic instability in Latin America, the strategic imperatives play significant roles in the American inventions. After decades of seemingly endless construction efforts, the opening of the Panama Canal in August 1914 solidified the strategic American interest of maintaining sea lanes in the Caribbean. In that same month, the outbreak of war in Europe further heightened the geopolitical importance of the region. The United States could not tolerate Europeans extending their conflict into the Western Hemisphere. Haiti’s government slipped into debt to the United States, Germany, and other nations, making it more vulnerable to foreign influences. Civil strife was also a constant: six Haitian presidents were overthrown and replaced in rapid succession between 1911 and 1915. When these factors are contextualized, Democratic and Republican American presidents alike felt justified in sending U.S. Marines to the region.15 President Woodrow Wilson recognized that a stable Haiti helped ensure a peaceful Caribbean. Wilson remarked to his acting secretary of state Robert Lansing that “there is nothing to do but take the bull by the horns and restore order.”16 Wilson ordered 340 Marines and sailors to land in Port-au-Prince and restore order on 28 July 1915. The term invade more accurately described their arrival. Several thousand Marines did tours in Haiti during the next two decades. Making the connections between order and peace pointed to the bigger American objective: establishing hegemony in the region. The choice of terms and tones pointed to an imperial effort. Indeed, the Marines can be seen as agents of imperialism.17 In his role as the first American naval commanding officer, Rear Admiral William B. Caperton declared martial law, disbanded the Haitian Army, and took control of Haiti’s customs houses. The latter move gave the United States control of the nation’s revenue.18 Looking back from 1934 to his occupation duties, Marine veteran Captain John H. Craige wrote candidly, if not also cynically, “I blush at the transparent maneuvers to which we resorted to make it appear that the Haitians were accomplishing their own regeneration in accordance with democratic principles as understood in the United States.”19 The Haitians found themselves compelled to accept an unpopular president named Philippe Sudré Dartiguenave, yet it was clear to the people that the Marines ran the government. The Haitians found the corvée system to be the most vexing American policy. This system mandated that peasants paid taxes or worked in kind to maintain roadways. Impoverished laborers could not pay, so they worked—sometimes compelled by violence or threats from the Marines. The resulting problems exacerbated the suffering of Haitians living at subsistence levels. Indeed, for some Haitians, the Marine occupation represented a return to race-based slavery. The corvée system likely aggravated the tense situation in Haiti and fed the insurgent violence against the Marines and their puppet government.20 In practice, neither the Americans nor their client rulers exerted power in the countryside as long as bandits, mercenaries, and revolutionaries (known as cacos) obstructed attempts by the Haitian government and Marines to establish law and order. As many as 15,000 cacos achieved some success as insurgents when led by charismatic leaders like Charlemagne M. Péralte in 1918. He used guerrilla tactics to ambush gendarme (police) units in rural areas or conducted hit-and-run attacks against small outposts. The cacos then melted back into the civilian populace. They also intimidated and terrorized the peasants living there who might assist the Americans. Combating these insurgents proved to be no simple task. In one key measure in 1916, the Marines formed Gendarmerie d’Haiti, a constabulary force with mostly Marine officers and Haitian enlisted personnel. Within their areas of operations, the Marine officers controlled military, police, and judicial actions. The cacos’s insurgency finally ended after Marines killed Péralte in 1919.21 Haiti achieved relative stability in 1922 under the government of American-backed president Louis Borno, but the real power lay in the hands of John H. Russell, a Marine Corps brigadier general and the American high commissioner with the rank of ambassador extraordinary. His eight-year tenure until 1930 provided some continuity in Haiti during this period. The number of hospitals and other public buildings multiplied. Russell’s initiatives made drinking water safer and improved sanitary conditions in Haitian cities. Infrastructure made marked gains, including the construction of 1,609 km of new roads and some 200 new bridges. Improvements to harbor facilities helped spur Haiti’s economic growth, including increasing exports of sugar, cotton, and coffee. However, the labor came from peasants working without pay in the corvée system, and most of the new revenue funded Haiti’s national debt or covered costs of the Marine occupation. Additionally, Russell’s attempts to establish democratic institutions such as free elections failed to live up to idealized American expectations.22 The Marine occupation shifted in mission after 1929 because falling prices and increasing taxation caused an economic downturn that led to strikes among Haitian workers and violence in the streets. One incident in particular became the symbol of Marine failures. In December 1929, while patrolling the coastal city of Aux Cayes, a small detachment of Marines encountered several hundred Haitian rioters who surrounded and pelted them with rocks. The Marines reacted and fired into the crowd, killing or wounding several dozen Haitians.23 In the wake of this tragedy known as the AuxCayes Massacre, President Herbert Hoover ordered an investigation of the incident and the Marine occupation as a whole. The findings recommended that Marines leave Haiti. Consequently, Hoover began shifting away from the interventionism of Dollar Diplomacy toward a new Good Neighbor foreign policy. As the purportedly benevolent neighbor to the north, Americans hoped to create reciprocal commercial and political relationships with the peoples of Latin America. Finally, after taking office in 1933, President Franklin D. Roosevelt ordered the Marines to withdraw from Nicaragua that same year and from Haiti in 1934.24

Haiti's Social Structure and Voodoo Practices

When the Marines first landed in Haiti in 1915, they found race-based and religious caste systems. The wealthiest 10 percent of Haiti’s population oppressed the remaining people. The ruling elite minority was comprised of mixed-race Haitians who spoke French, professed Catholicism, lived in urban areas, and found work in the government or with banks or corporations. Many of them owed their status directly or indirectly to American commercial activities. This elite class tended to ignore or antagonize their fellow Haitians who believed in Voodoo. Among the 90 percent, the impoverished and illiterate Haitian peasant majority, known as noirs, were of purer African ancestry. They spoke Creole, practiced Voodoo, and survived as subsistence farmers.25

As Marines spent more time in Haiti, they came to dislike the Haitian elite. Some Marines sympathized with the poor Haitian peasants in rural areas, Voodoo practices and racial prejudice notwithstanding. In a report from the early 1930s, one Marine remarked

No matter what crimes [Marines] might count against the better class of Haitian (I refer to the peasants, those without benefit of education) such crimes could not conceivably equal in effect and in their atrocious nature the crimes that have been committed against [the peasants] by the lower class—the professional Haitian politician.26

The sarcastic term lower class referenced mixed-race politicians. Decades later in 1969 after he retired, Merwin H. Silverthorn recalled his service as a captain in the 1st Marine Regiment, having briefly served as the unit’s commander on two occasions in 1926.27 In his oral history interview, he recalled the same two-class system in Haiti.

The peasants were hard-working people. They would till plots of ground on the side of the mountain or along a riverbed somewhere with primitive tools, transport them long distances to market. They lived on very meager income, but they were very solid, reliable people. They were pleasant to be with.28

Silverthorn later criticized the wealthy Haitian as an “educated man” who was a “schemer” and “lives off the product of his less fortunate people.”29 Even so, most American Marines deployed to Haiti between 1915 and 1934 were firmly instilled with Protestant, Caucasian, and Anglo-Saxon mores. These factors informed their attitudes about the Haitians.

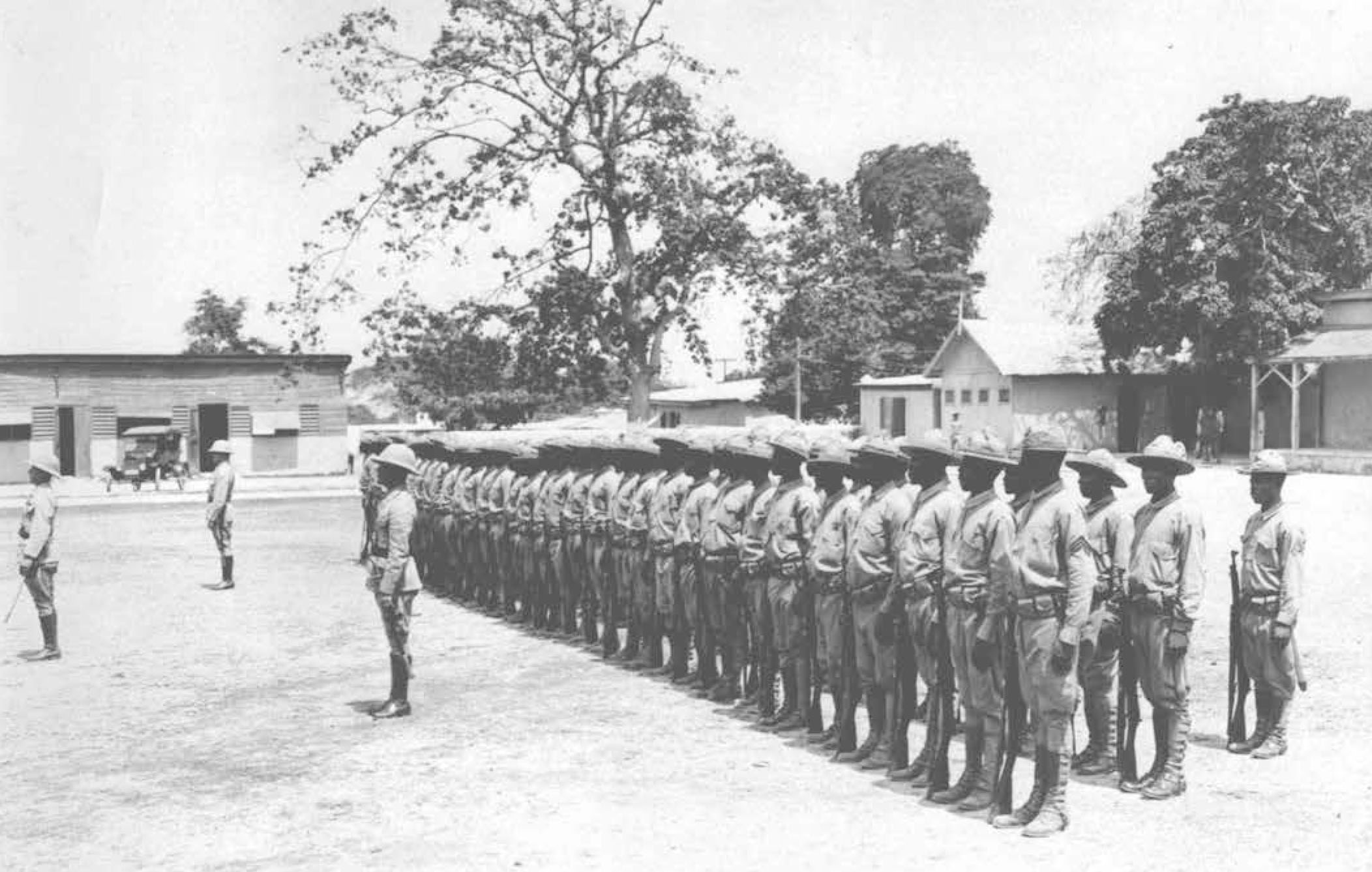

Trained and commanded by U.S. Marine Corps officers and noncommissioned officers, this is a typical company of the Gendarmerie d’Haiti (later Garde d’Haiti) that played an important part in bringing law and order to the Republic of Haiti, April 1927. Official U.S. Marine Corps photo, Historical Reference Branch, Marine Corps History Division

Because some of the Marine officers had Protestant upbringings, they also conflated Voodooism with Catholicism as twin blights on Haitian culture, both in need of reform.30 Voodoo in fact blends West African religious traditions with Catholicism. In the Haitian peasant’s eyes, lighting candles and the scents and bells used during Catholic mass resembled Voodoo ritual. They saw some similarities between venerated Catholic figures such as the Virgin Mary and Saint George with Voodoo figures such as Ezili, the loa of maternal and physical love, and Ogun, the loa of war. This fusion of the two religions is called syncretism by scholars. The Haitian peasants were far more likely to combine Voodooism with Catholicism than to accept the Protestant Christianity espoused by most American Marines.31

Racial attitudes cannot be ignored. Back in the United States, Jim Crow laws still repressed African Americans, and lynchings of blacks occurred in rural areas. Racist sentiments ran up and down the ranks of the Marine Corps.32 In the 1920s, when one enlisted Marine learned that he would be stationed in Haiti, he reacted with disgust in a letter that he did not believe “any white man should be killed to save a few ignorant n——s, without whom the world would be much better off.”33 Among the officers, approximately 50 percent of the white Marine officers hailed from former slave-holding states, whereas the white male population of those states amounted to 15 percent of their demographic in the United States in the 1920s.34 The prejudice was not limited to those officers from the southern states, but also extended to northerners. Pennsylvanian Brigadier General Smedley D. Butler commented in the 1920s on commanding the Garde d’Haiti, “I am reduced to a very humiliating position” as the “chief of a n——r police force.”35 Later, after he took command of the gendarmerie, Butler called the Haitians “chocolate soldiers.” This label may not have matched the vitriol of Butler’s earlier comments, but it was no less prejudiced. When enlisted Marines revealed their attitudes in personal letters, they might be limited only to themselves and the recipient of their letters. However, a senior leader expressing views such as Butler’s indicated a very real possibility that the organizational culture was infected with those attitudes.36

Riflemen of the Haitian gendarmerie. Official U.S. Marine Corps photo 3167, Historical Reference Branch, Marine Corps History Division

In similar ways, American and Marine prejudices depicted Voodoo and its practitioners in pejorative ways. Some Haitians practiced polygamy, promiscuity, or cannibalism, all of which the Marines found to be immoral and often illegal. It is easy to see why Marines were inclined to equate the religion with Christian notions of witchcraft and identify its Haitian followers as superstitious peasants at best or self-professed witch doctors or sorcerers at worst.

An incident in 1928 illustrated how Haitians might take Voodoo’s medical treatments for granted, while Marines took a more skeptical view. A memorandum related that a Haitian man named Emmanuel Philinmon complained that someone or something mysteriously hit his stomach despite claiming no one entered his room. Then, according to his relatives, he “became insane and incoherent” two days later, and they stated that Philinmon “was possessed of the devil.” They claimed that he spoke these words: “I do not want to leave Philinmon. I was ordered and sent to take you with me . . . and I tell you that I am a relative of Lucifer.” The relatives then treated him with “native leaves and roots only in the form of liquid.” When the madness gripped Philinmon again, they bound his hands to prevent injury. After about 10 days, he died. His family did not ask for conventional medical treatment or medicines. Thus, the cause of death could not be confirmed. The Marine writing the report concluded, “I myself belief that [Philinmon’s] mental affliction is probably due to the fever and also this history of the devil is due to the ignorance of these people.”37 The Marine’s investigation uncovered other details that painted a more disturbing picture of Philinmon’s death.

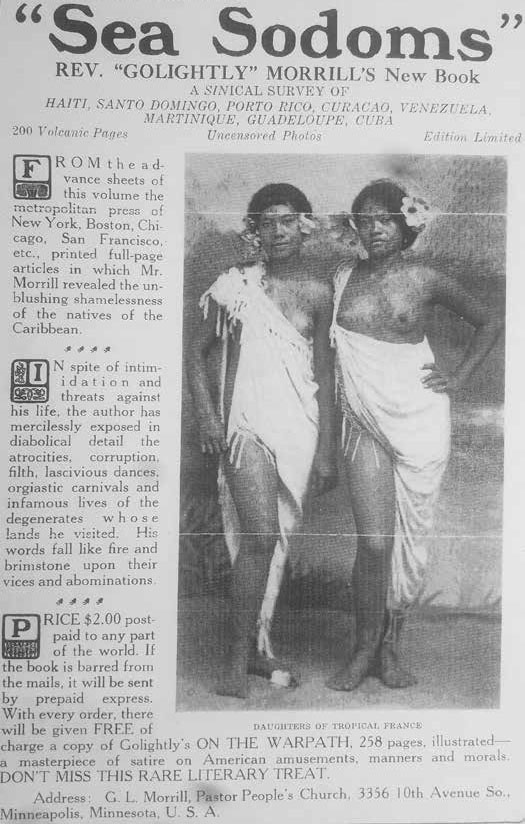

Advertisement for the Reverend G. L. Morrill’s provocative book published in the United States in 1921. The advertisement played on and contributed to Americans’ racial, sexual, and religious assumptions. John H. Russell Papers, box 2, folder 18, Archives Branch, Marine Corps History Division

Marine Attempts to "Stamp Out" Voodoo

The Marines tried to “tame” Haiti, to use the words of historian Mary A. Renda in 2001. Uplifting the “inferior” Haitian people involved what could be considered to be an Americanized process of the French colonial term mission civilisatrice. Renda also finds that the Marines attempted to “modernize and rationalize Haitian society” and thus exhibited “paternalism.”38 Looking back from the 1960s to his time as a junior Marine officer serving in Haiti, retired General Alexander A. Vandegrift remarked, “In a sense our task formed a civil counterpart to the work of Christian missionaries who were devoting their lives to these people.”39 Renda’s observation and Vandegrift’s reflection were consistent with the progressive goals that President Wilson espoused when he ordered the Marines into Haiti in 1915.

Like race and caste, Voodooism emerged as a major obstacle to the Marines’ modernization and rationalization of Haiti. The religious practices served as modes of disruption and means of resistance that undermined the Marines’ efforts to install stability, as evinced in a Marine Corps report on illegal Voodoo rituals in Haiti, which noted that “arrests have been made for superstitious practices, which have created disorder, fear and crime since March 1924.” The words disorder, fear, and crime must be emphasized because they represented everything that the Marines hoped to avoid in Haiti.40

Article 409 in Haiti’s Code Penal mandated that “makers of ouangas [talisman], practitioners of Voodoo, macandalisme” and “all dances and other practices calculated to foster fetishism and superstition shall be deemed witchcraft and punished accordingly.”41 At any given time, Marines banned Voodoo ceremonies, raided places of worships (called hounforts), or confiscated drums and other religious objects utilized in rituals.42 In the Dominican Republic as in Haiti, the Marine-controlled governments banned Voodoo in what, according to Latin American military historian Ellen Tillman, “was a direct attack on integral cultural practice.”43

The Marines also found a corrupt Haitian legal system that needed reform. For the Marines, herein lay one of the most effective ways to achieve American goals. Aside from being susceptible to bribery, the Haitian courts could be swayed by Voodooism. Haitian juries, for example, acquitted their countrymen of murder charges if the victims were supposed werewolves (loup-garou), dangerous or evil beings in Voodoo.44

To eliminate what the Marines saw as injustices, they established provost courts under the auspices of declaring martial law in 1915. Composed of one or three Marines serving as judges, these military tribunals heard cases involving the most violent Haitian offenders.45 Over time, fewer and fewer provost courts were called and, by 1927, none at all. At the behest of his superiors in Washington, High Commissioner John Russell increasingly turned over judicial functions to the Haitians, so long as they dispensed justice fairly. The Marines nevertheless kept records of Voodoo cases to ensure that justice was served.46

These legal reports referenced two types of prosecutions against Voodoo-related criminal offenses. The first type entailed prosecuting Haitians for Voo- doo practices and rituals. Such offenses could be relatively benign in that no one was necessarily killed or seriously injured. In cases following arrests “made for superstitious practices which have created disorder, fear and crime,” Haitians found guilty received fines and jail sentences, but these penalties were not so severe because some offenses were considered misdemeanors in nature.47 The crimes always disrupted stability because the laws prohibiting Voodoo required enforcement, or order would dissolve into anarchy. A sampling of the arrests made for the religious practices and sentences imposed during the late 1920s can be seen in the following report.

Dec. 13, 1926—

Edouard Lazarre [and others] were arrested for a Vaudou dance. The testimony stated that this dance was made for the Saints. They were each sentenced to serve 4 months in prison and pay a fine of 60 gourdes by the [Haitian Justice of the Peace in Mom- bin Crochu].48

The testimony cited in the 13 December summary demonstrated, according to the Marines’ perspective, how Haitians blended Voodooism and Catholicism. Nevertheless, this allusion to Catholicism did not necessarily equate to sufficient grounds for acquittal by the court as seen several weeks later.

Jan. 11, 1927—

Eltrevil Saintilmon [and others] were arrested for cooking “Manger pour les Saints”. They were each sentenced to serve 3 months in prison and pay a fine of 60 gourdes by the [Haitian Justice of the Peace in Vallieres].49

The criminal act in the 11 January summary entailed leaving food for the Voodoo spirits. It did not matter that the term saints was used by the defendants.

Sometimes the accused would be released by the Haitian courts because their potions had been used to heal sick children.

Jan. 16, 1927—

Charlestin Charles [and others] were arrested for “Ouanga.” They were sentenced to serve 3 months in prison and pay a fine of 60 gourdes by [Haitian Justice of the Peace in Vallieres].50

In Voodoo, ouanga were talisman or spells that could be cast to protect oneself and one’s family, or they could inflict some harm on people. One example of ouanga is the Voodoo doll.51 Some ouangas might be used to ward off zombies (sometimes rendered zambie) or to direct zombies to kill enemies. As far as the Marines were concerned, turning a person into a zombie represented one of most odious of Voodoo practices because, as one scholar observes, a zombie was “a person whose soul has been captured by a sorcerer, leaving the individual without a will of their own.”52 The Haitians’ beliefs made zombification antithetical to the American Marines’ sense of individual autonomy and reinforced their assumptions of Haitian superstitions.53 The 16 January 1927 summary was not clear about the purpose of the spell that was cast; however, if found guilty, Haitians so accused of “making ouanga” faced similar fines and prison terms.54

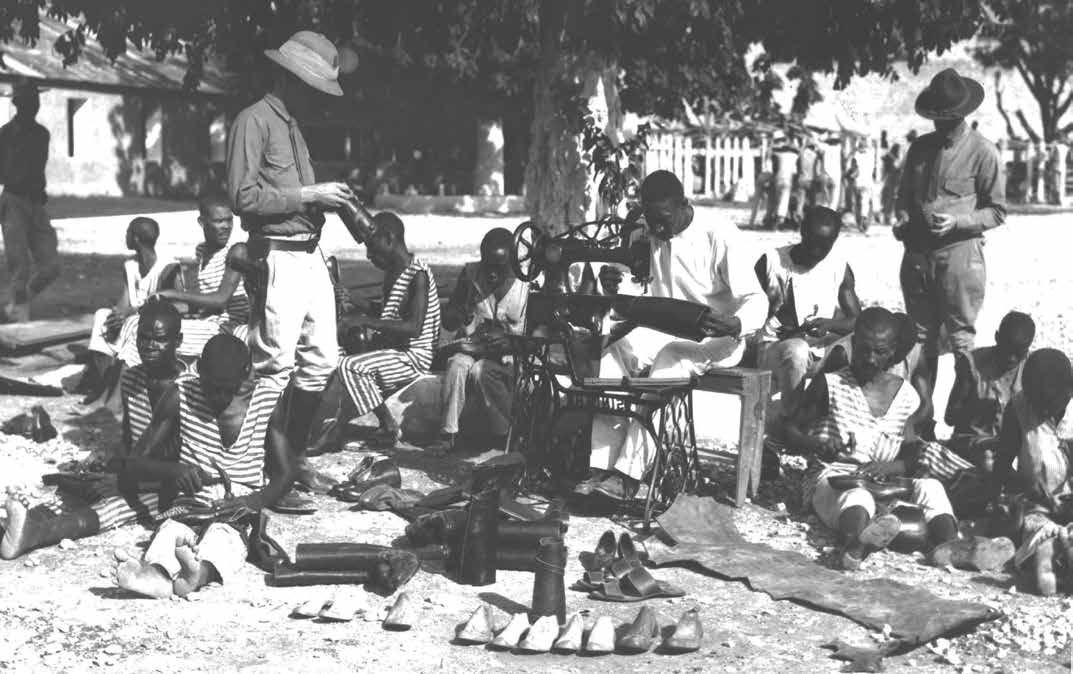

Haitian prisoners making shoes at the National Penitentiary at Port-au-Prince, Haiti, ca. 1919. Official U.S. Marine Corps photo 519856, Historical Reference Branch, Marine Corps History Division

The second type of Voodoo prosecution involved criminal activities in which Voodoo was allegedly employed to harm others, either financially or physically. Offenses included extortion, blackmail, assault, and murder. Although the existing archival evidence does not include the final verdicts set down by Haitian courts, the following accusations, testimonies, and reports of these cases illustrated the attitudes among Marines about the illegitimacy of Voodooism as well as the disruption caused when its practices were used as a justification for what the Marines deemed to be criminal activities.55

In one report to the commandant of the Garde d’Haiti in 1929, the subject read as “Swindling by means of witchcraft.”56 The complainant, a woman named Vallerie Laville, claimed her family member

had been victimized to the extent of thousands of dollars by persons who had, by means of drugs, sorcery and certain acts of alleged witchcraft, intimidated [the Laville family] into paying stupendous amounts of money which was in turn to be paid over the certain evil spirits in order to combat other spirits who were supposed to hold the lives of the Laville family in their hands and who lusted for their blood.57

A four-page statement by Laville was appended that laid out her grievances and demonstrated her desire for justice. Near the end of this report, those accused of extortion and swindling included one woman who, according to the Marines’ subsequent investigations, was a “known sorceress and artistic witchcraft expert” who had “many politicians and private citizens under her thumb.”58 A second alleged accomplice was “noted as a rounder.”59 They were, to use today’s terminology, scam artists. No final verdict existed in the archival records.60 However, the language herein indicated that the exploitation of Haitian peasants’ beliefs fit into Marines’ skeptical view of Voodoo’s legitimacy as a religion.

Voodoo also played roles in investigations of violent crimes as evinced in an “instance where superstitious practices have led to murder.”61 This quote from the first lines of the Marines’ report makes the verdict a foregone conclusion. The report included statements made by the defendant, St-Ilmar Jean, during an interrogation about her role in her mother’s death in 1927. When asked whether she “really caused the death” of her mother, St-Ilmar Jean confessed, “Yes, Judge. It is really I who had my mother killed.”62 Because she believed her mother, Christine Crispin, had cursed her children and caused their deaths, St-Ilmar Jean decided to conspire with two relatives to kill her mother. St-Ilmar justified this action “the only way I could get rid of her My mother really was a detestable ‘loup-garou’.”63 St-Ilmar Jean’s relatives subsequently killed her mother with machetes. Here again, Haitian peasants believed this gruesome violence was permissible because the daughter believed her mother to be a werewolf, and her own words revealed no re- morse about her part in the murder conspiracy. The end of the report stated that St-Ilmar Jean’s case went to a Haitian criminal court, but no verdict had been rendered even after several months.64 From the Marines’ perspective, this could have been considered an easy conviction. However, as seen already, the Haitian judiciary could be moved by Voodooism to make acquittals.

In other murder cases, even when evidence pointed toward a guilty verdict, the Haitian courts could be swayed by Voodooism. Two examples represented what could best be termed justifiable homicide. An accused Haitian man testified that he killed a woman because she was a werewolf that had allegedly caused the death of his child. Another case included testimony by several Haitians that they killed a man “because he has been eating their children.” Cannibalism of humans could not be considered to be the proper practice of Voodoo. The fact that both were examples of self-defense and thus permitted by Voodoo notions of morality contributed to the Haitian courts’ decisions to acquit the defendants of murder charges.65 Latin American historian Alan McPherson offers useful interpretations of the courts’ decisions. He argues that they represented one means to resist the Marine occupation in Haiti: “Resistance through courts consisted of efforts to side with non-insurrectionists and non-activists who simply engaged in cultural and economic activities that were banned by the occupation forces.” The Haitian courts’ goal in these acquittals, writes McPherson, “was not to harm the occupation but to continue living as in pre-occupation days.”66

The acquittals in the Haitian court system frustrated the Marines as they attempted to impose order. In a letter written in 1927, a Marine major named John R. Henley complained “that our intelligence files for the last year contain several cases of crimes (murder) committed for purposes of eliminating ‘loup garou’ from the scene of action. You have copies of these reports sent to Hqers. [headquarters] in connection with this miscarriage of justice.”67 These last words— miscarriage of justice—need to be highlighted because Henley believed that Voodoo could not be used as an excuse to undermine law and order.

More insightful analysis can be drawn from another part of Henley’s letter. He possessed a sophisticated and nuanced view of Voodoo and its place in Haitian culture and life, when he conceded, “I have made very careful inquiries of all my officers and others and I can find no single case where the alleged vodoo [sic] dances have led to disorderliness etc or directly to other crimes.” He observed substantive distinctions between uses of Voodoo, differentiating between the relatively benign practice of rituals and the practice to justify criminal behavior. Henley’s comments should be contextualized as the commander of the Department of the North in Haiti. In this position, he received reports regarding the investigation of the death of Emmanuel Philinmon later in 1928. Henley’s observation is as applicable (as is this entire article) to American occupations of culturally diverse nations in the twenty-first century as it was in 1927.68

In addition to Henley, other Marines maneuvered within Haitian social and religious contexts. Marine Sergeant Faustin E. Wirkus gained notoriety for his tolerance of Haitians and their religion while he served on the island of La Gonâve along the coast near Port-au-Prince. He tried to dispense justice in court cases quickly and fairly. The Haitians supposedly crowned Wirkus “king” of the island.69 Another Marine officer, Merwin Silverthorn, asserted that “out in the country voodooism was a form of entertainment.”70 He thus shared a less negative attitude about the Haitians’ religion.

Epilogue and Conclusions: The Small Wars Manual and Beyond

During the occupation from 1915 to 1934, the U.S. Marines achieved some successes in Haiti including establishing and training the Gendarmerie d’Haiti and later the Garde d’Haiti. The Marines directed the construction of roads, hospitals, and other public buildings in hopes of modernizing Haiti’s virtually nonexistent infrastructure. They tried to decrease, but never did eliminate, the rampant corruption in Haiti’s political and judicial systems. All these activities laid a foundation for what they hoped would remain a democratic and free Haiti. These hopes came to nothing because of the occupation’s wasted opportunities or short-term successes. The “Haitianization” of government, judicial, and military functions could not provide a viable foundation.71 In terms of politics, the Marines had created a government structure in Haiti that remained dependent on their ongoing support, yet that same structure also aroused the ire of Haitians and thus could barely function even when propped up by the Marines. The combination of mutual conflict and mutual dependence created a catch-22 for the Marines in Haiti. Just as happened in other Latin Ameri- can nations after American occupations ended in the early twentieth century, so too did the structures in Haiti collapse when the Marines departed. The nation plunged once again into alternating periods of dictatorship or anarchy in the subsequent decades.72

In addition to political and economic missteps, the Marine occupation in Haiti can be seen in some ways as a cautionary tale of cultural misunderstandings. Too few Marines appreciated the religious and cultural factors at play in Haiti, such as—most notably for purposes of this article—the practice of Voodoo. To read Brigadier General John H. Russell’s evaluations during his tenure as high commissioner in the 1920s, Haiti went from a nation where “Vaudoism was rife and Human sacrifice was not uncommon” to a nation that benefited from “the introduction of the tenets of modern civilization” that “has done much to stamp out this Horrible Practice.”73 Reality proved to be different, however. The Marines failed to suppress Voodoo; instead, they alienated many otherwise dis- passionate Haitians. The Marines rarely grasped how or why this religion was so central to Haitian life. Such confusions in turn restricted and ultimately negated the occupation’s effectiveness in achieving the mission of modernizing and democratizing the nation.

In analyzing the occupations of Haiti and other Latin American nations, historian Ellen Tillman asserts that “the exportation of the U.S. institutions through the use of the military” were “experiments.”74 The term experiments is key to understanding the Marine occupations in the region. No doctrines existed for achieving grand political and economic objectives in Haiti. Moreover, no careful consideration went into understanding cultural features such as Voodoo-ism. Instead, many Marines dismissed the religion as immoral and superstitious at best, or unlawful and dangerous at worst. In almost all cases, they tried to suppress Voodoo practices through civil and criminal legal channels. There is no denying that suppression failed due in part to the prejudices held by so many Marines and other Americans. Yet, on another level, Tillman’s term experiment is critical to include in this discussion because it points to another institutional reason for failure, or perhaps more accurately, another reason success was impeded. Without the self-reflection ideally yielded by doctrines, the Marines had to make up the occupation process, including their attempt to stamp out Voodoo, as they went along. With the occupations ending in the early 1930s, the Marines could step back and assess the successes and failures in Haiti and other nations in Latin America. This process took place at the Marine Corps Schools in Quantico, Virginia, in the 1934–35 academic year when Marine students and faculty captured lessons and codified doctrines in the Small Wars Manual of 1935, designated Navy and Marine Corps 2890 (NAVMC 2890), and subsequently in the revised edition of 1940. The term small wars differentiates military occupations such as the one in Haiti from those military operations in formally declared conflicts such as the First World War. The 1940 edition offers this clarification:

Small Wars vary in degrees from simple demonstrative operations to military intervention in the fullest sense, short of war. They are not limited in their size, in the extent of their theater of operations nor their cost in property, money, or lives. The essence of a small war is its purpose and the circumstances surrounding its inception and conduct, the character of either one or all of the opposing forces, and the nature of the operations themselves.75

In twenty-first century parlance, the small wars concept equates to counterinsurgencies. As part of culling useful lessons from the occupation, the Marine Corps Schools sent surveys to officers who served in Latin America during the preceding de- cades. Those Marines spending time in Nicaragua, for example, received surveys with 40 questions dealing with tactical, operational, and logistical aspects. One asked, “What do you think of the suitability of the Browning Machine Gun, 30 calibre, for use on combat patrols? Of the 3 [inch] Trench Mortar? The Rifle Grenade? The Hand Grenade?” Another queried, “Do you think that a training center, and an Infantry- weapons School should have been established in Managua?” And yet another asked, “Do you prefer horses or mules, and why?” The self-reflective, self-critical answers yielded ample evidence to fill the Small War Manual’s 15 chapters covering logistics, combat operations, military governments, monitoring elections, and the arming and disarming of “native” groups, among other topics.76

In addition to these functional aspects, the manual also devotes space to less tangible cultural factors. The Marines did not use the word culture, but the terms they did employ fit under the concept of culture.77

Many decades later, the Corps’ efforts in Haiti resemble the American counterinsurgency in Operations Iraqi Freedom and Enduring Freedom. Indeed, the similarities between American operations in Haiti and those in Iraq and Afghanistan are striking. The 1940 edition of the Small Wars Manual like-wise served as a doctrinal foundation for Counterinsurgency, Field Manual 3-24/Marine Corps Warfighting Publication 3-33.5, completed by the U.S. Army and the Marine Corps in 2006.78

•1775•

Endnotes

- Other spellings include Voudu in French, as well as Vaudou, Vodoun, and Vaudoux. See Harold Courlander, “The Word Voodoo,” African Arts 21, no. 2 (February 1988): 88, https://doi.org/10.2307/3336535.

- For example, although Allan R. Millett devotes part of one chapter to the occupation of Haiti in his seminal survey Semper Fidelis: The History of the United States Marine Corps, rev. ed. (New York: Free Press, 1991), he does not deal with the influence of Voodoo. The same can be said of James H. McCrocklin’s compilation Garde D’Haiti, 1915–1934: Twenty Years of Organization and Training by the United States Marines (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 1956); Hans Schmidt, Maverick Marine: General Smedley D. Butler and the Contradictions of American Military History (Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 1987); and Keith B. Bickel’s sociological study Mars Learning: The Marine Corps’ Development of Small Wars Doctrine, 1915–1940 (Boulder, CO: Westview Press, 2001). Mary A. Renda deals in detail with Voodooism, racism, and paternalism in her landmark book Taking Haiti: Military Occupation and the Culture of U.S. Imperialism, 1915–1940 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2001). However, Renda did not fully comprehend the operational contexts of the Marines in Haiti. Of the books on Marine Corps history used for this article, only Robert Debs Heinl and Nancy Gordon Heinl’s Written in Blood: The Story of the Haitian People, 1492–1971 (Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin, 1978) examines Voodoo in Haiti during the occupation. The Heinls, however, were likely not privy to the primary source documentation referred to in this article. Between 1949 and 2015, only 48 articles focused on the Marine occupation of Haiti out of 355 articles published in scholarly journals on Haiti, the Caribbean, Postcolonialism, or Latin American Studies. The vast majority of the remaining articles concentrated on the revolutionary period of 1793–1804. See Raphael Dalleo, American Imperialism’s Undead: The Occupation of Haiti and the Rise of Caribbean Anticolonialism (Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2016), 10–13.

- John H. Russell applied the term stamp out (seen here, the article’s title, and elsewhere in this article) to Voodoo in Haiti. See John H. Russell, Some Truths about Haiti, John H. Russell Papers, box 3, folder, Archives Branch, Marine Corps History Division, Quantico, VA.

- Much of the material in this section on Haitian history is drawn from Philippe Girard, Haiti: The Tumultuous History—From Pearl of the Caribbean to Broken Nation (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 2010), 1–80; and Leon D. Pamphile, Contrary Destinies: A Century of America’s Occupation, Deoccupation, and Reoccupation of Haiti (Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 2015), 1–17.

- The term Bondye is derived from the French term bon Dieu, meaning “good God.”

- Anthony B. Pinn, Varieties of African American Religious Experience: Toward a Comparative Black Theology, 20th anniv. ed. (Minneapolis, MN: Fortress Press, 2017), 3–10; and Claudine Michel, “Of Worlds Seen and Unseen: The Educational Character of Haitian Vodou,” Comparative Education Review 40, no. 3 (August 1996): 280–94, https://doi.org/10.1086/447386.

- Throughout the periods of Haiti’s history discussed in this article, individuals with one white parent and one black parent were referred to as mulâtres or mulattos, and their social status often was determined by such racial castes/categories. For the remainder of this article, the term mixed-race will be used in place of the term mulatto except in directly quoted material.

- Laurent Dubois, Avengers of the New World: The Story of the Haitian Revolution (Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press, Harvard University Press, 2004), as cited in Girard, Haiti, 40.

- Leslie G. Desmangles, The Faces of the Gods: Vodou and Roman Catholicism in Haiti (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1992), 6.

- Claudine Michel, “Vodou in Haiti: Way of Life and Mode of Survival,” in Claudine Michel and Patrick Bellegarde-Smith, eds., Invisible Powers: Vodou in Haitian Life and Culture (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2006), 32. See also Alfred Métraux, Voodoo in Haiti, trans. Hugo Charteris (New York: Schocken Books, 1972), 41, as cited in Abel A. Alves, “Voodoo Syncretism in Haiti and New Orleans” (class presentation, History 468, Witchcraft, Magic, and Science in the Early Modern World, 1492–1859, Ball State University, April 2008).

- Girard, Haiti, 28–29.

- For a recent book that not only analyzes Dollar Diplomacy but also serves as a model for blending military and cultural history, see Ellen D. Tillman, Dollar Diplomacy by Force: Nation-Building and Resistance in the Dominican Republic (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2016), 1–10, 53–77.

- Woodrow Wilson, statement to British envoy William Tyrrell, ca. November 1913, as cited in Benjamin T. Harrison, “Woodrow Wilson and Nicaragua,” Caribbean Quarterly 51, no. 1 (March 2005): 26, https://doi.org/10.1080/00086495.2005.11672257.

- William E. Leuchtenburg, “Progressivism and Imperialism: The Progressive Movement and American Foreign Policy, 1898–1916,” Journal of American History 39, no. 3 (December 1952): 500, https://doi.org/10.2307/1895006. For other historians with varying ideologies but similar conclusions, see Walter LaFeber, Inevitable Revolutions: The United States in Central America, 2d ed. (New York: W. W. Norton, 1993), 31– 78; Alan McPherson, The Invaded: How Latin Americans and Their Allies Fought and Ended U.S. Occupations (New York: Oxford University Press, 2014), 1–9; Pamphile, Contrary Destinies, 17–18; and Matthew S. Muehlbauer and David J. Ulbrich, Ways of War: American Military History from the Colonial Era to the Twenty-First Century, 2d ed. (New York: Routledge, 2017), 267–75, 319–21.

- See LaFeber, Inevitable Revolutions; and McPherson, The Invaded.

- Cited in Max Boot, The Savage Wars of Peace: Small Wars and the Rise of American Power (New York: Basic Books, 2002), 161.

- For more analysis, see D’Arcy Morgan Brissman, “Interpreting Ameri- can Hegemony: Civil Military Relations during the U.S. Marine Corps’ Occupation of Haiti, 1915–1934” (PhD diss., Duke University, 2001).

- See Edward Latimer Beach, “Admiral Caperton in Haiti,” [ca. 1915], 1–5, Naval History and Heritage Command, accessed 13 May 2019; and Boot, The Savage Wars of Peace, 159–66.

- John Houston Craige, Cannibal Cousins (New York: Minton, Balch, 1934), 60, as cited in Boot, The Savage Wars of Peace, 167.

- Dalleo, American Imperialism’s Undead, 10–13; and Renda, Taking Haiti, 10–11, 53, 139–49. The author is grateful to the anonymous peer reviewer for offering key clarifications in this paragraph.

- Girard, Haiti, 85–88; Hans Schmidt, The United States Occupation of Haiti, 1915–1934 (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1995), 85–90; and Alan McPherson, A Short History of U.S. Interventions in Latin America and the Caribbean (Malden, MA: John Wiley and Sons, 2016), 78–81, 102–5.

- Pamphile, Contrary Destinies, 28–34. For extensive commentary by a Marine serving in Haiti during the 1920s, see Merwin Silverthorn, interview with Benis Frank, 28 February 1969, transcript (Oral History Section, Marine Corps History Division, Quantico, VA), 138–76, hereafter Silverthorn oral history interview transcript.

- Alan McPherson, “The Irony of Legal Pluralism in U.S. Occupations,” American Historical Review 117, no. 4 (October 2012): 1160, https://doi.org/10.1093/ahr/117.4.1149.

- For recent scholarship, see McPherson, A Short History of U.S. Interventions in Latin America and the Caribbean, 124–27; and Girard, Haiti, 94–97. For an older, yet still relevant and balanced, study, see Bickel, Mars Learning, 71–105; and for an explicit neoconservative and American Exceptionalist interpretation, see Boot, The Savage Wars of Peace, 156–82.

- “Haiti–Reports and Inquiries Regarding Conditions and Conduct of Marines,” report by H. S. Knapp, 14 October 1920, Haiti–History file, Historical Reference Branch, Marine Corps History Division; BGen John H. Russell, “The Development of Haiti during the Last Fiscal Year,” Marine Corps Gazette 15, no. 2 (June 1930): 83–85; Gen A. A. Vandegrift as told by Robert B. Asprey, Once a Marine: The Memoirs of General A. A. Vandegrift (New York: Norton, 1964), 57; McCrocklin, Garde d’Haiti, 139; Millett, Semper Fidelis, 178–79; Heinl and Heinl, Written in Blood, 2–5; Patrick Bellegarde-Smith, “Resisting Freedom: Cultural Factors in Democracy—The Case of Haiti,” in Michel and Bellgarde-Smith, Invisible Powers, 107; Desmangles, The Faces of the Gods, 2–3, 8–10, 50; and Renda, Tak- ing Haiti, 19, 274–75. For more analysis of the Haitian elite, see Magdaline W. Shannon,Jean Price-Mars, the Haitian Elite, and the American Occupation, 1915–1935 (New York: St. Martin’s, 1996), https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-349-24964-0.

- “Haiti-History,” report by an anonymous author, [ca. 1930], Haiti file, Historical Reference Branch, Marine Corps History Division. For similarly disdainful attitudes among Marines regarding Haitian elite, see also John H. Russell, “A Laboratory of Government,” Russell Papers, box 3, folder 6, Archives Branch, Marine Corps History Division; Millett, Semper Fidelis, 187; and Schmidt, Maverick Marine, 88–89.

- Danny J. Crawford, et al., The 1st Marine Division and Its Regiments (Washington, DC: History and Museums Division, Headquarters Marine Corps, 1999), 3–24.

- Silverthorn, oral history interview transcript, 153.

- Silverthorn, oral history interview transcript, 165.

- See also Carl Kelsey, Address on the Republic of Haiti Today. Delivered before the Society of Sons of the Revolution on April 29, 1922 (Washington, DC: Society of the Sons of the Revolution, 1922), 23; Michel, “Voodoo in Haiti,” 27; Desmangles, The Faces of the Gods, 1–3; and Renda, Taking Haiti, 45–52.

- Desmangles, The Faces of the Gods, 5–10, 27, 50, 132, 177; and Girard, Haiti, 30–31.

- For an example of disturbing white supremacist biases regarding Haiti, see Stuart Omer Landry, The Cult of Equality: A Study of the Race Problem, 2d ed. (New Orleans, LA: Pelican, 1945), 108–15, 136. For a more critical analysis of race, American foreign policy, and Haiti, see Michael H. Hunt, Ideology and U.S. Foreign Policy (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1988), 58–68, 99–103, 126–31; and Pamphile, Contrary Destines, 32–34. For the cultural contexts of racial theories and racism in the early twentieth century, see Wintermute and Ulbrich, Race and Gender in Modern Western Warfare, 3–12, 45–49, 80–89; and C. Loring Brace, “Race” Is a Four-Lettered Word: The Genesis of the Concept (New York: Oxford University Press, 2005), 5–42.

- Emil Porter, letter, March 1928, Emil Porter Personal Paper Collection, Robert E. and Jean R. Mahn Center for Archives and Special Collections, Ohio University, Athens, OH.

- See Heather Pace Marshall, “Crucible of Colonial Service: The Warrior Brotherhood and the Mythos of the Modern Marine Corps, 1898–1934” (master’s thesis, University of Hawaii, 2003); and Schmidt, Occupation of Haiti, 142–44.

- Cited in Robert L. Scheina, Latin America’s Wars: The Age of the Professional Soldier, 1900–2001, vol. 2 (Dulles, VA: Brassey’s, 2003), 47. For similar quotes by Butler and other Marines, see Schmidt, Maverick Marine, 75–76, 82–84.

- For an example in the U.S. Navy, see Harry Knapp to Secretary of the Navy, 13 January 1921, box 632, RG 45, WA-7, NARA, as cited in Pamphile, Contrary Destinies, 31. For more on American attitudes during occupation of the Dominican Republic, see Tillman, Dollar Diplomacy by Force, 80–81, 130.

- The District Commander, Cerca La Source, memorandum for the Department Commander, Subject: Report on Death of Emmanuel Philin- mon, 25 July 1928, Seldon Kennedy file no. 3248, Historical Reference Branch, Marine Corps History Division.

- Renda, Taking Haiti, 46, 45–52, 114–15, 212, 238. See also Desmangles, The Faces of the Gods, 31–37, 177; and Hunt, Ideology and U.S. Foreign Policy, 128–32. For a military analysis, see David Keithly and Paul Melshen, “Past as Prologue: USMC Small War Doctrine,” Small Wars and Insurgencies 8, no. 2 (Autumn 1997): 93–96, https://doi.org/10.1080/09592319708423175.

- Vandegrift, Once a Marine, 57–58. See also Schmidt, Maverick Marine, 91.

- C. H. Gray, memo for Department Commander, Department of the North, 17 October 1927, “Voodoo and Witchcraft Cases (14 September 1927 to 19 December 1930),” box 20, Records of the Gendarmerie d’Haiti, RG 127, A1, entry 21, NARA, hereafter Gray memo. Special thanks should go to Mr. Trevor Plante, an archivist in Old Military Records at the National Archives in Washington, DC, for helping the author to locate this file.

- As cited in Heinl and Heinl, Written in Blood, 484n59. The term macandalisme came from the name of an Arabic-speaking slave, Macandal, from West Africa who was burned at the stake after being convicted of attempting to poison whites and spreading that knowledge.

- Renda, Taking Haiti, 212–13.

- Tillman, Dollar Diplomacy by Force, 110.

- For particular cases whether accused murders were released because they had killed supposed werewolves or people similar possessed by evil spirits, see Harry Watkins, memo for Department Commander, Department of the North, 14 September 1927; and Gray memo. See also Mc- Crocklin, Garde d’Haiti, 131–32; and Heinl and Heinl, Written in Blood, 417, 456.

- General Order No. 6 issued by HQ District Commander, 9 September 1915, and General Order No. 8 issued by District Commander’s Office, 14 September 1915, both in “Haiti Occupation 1915–1934 Organization,” Historical Reference Branch, Marine Corps History Division; John H. Russell to the U.S. Secretary of State, 1 January 1923, Russell Papers, folder 18, box 2, Archives Branch, Marine Corps History Division; LtCol Charles J. Miller, “Diplomatic Spurs: Our Experiences in Santo Domingo,” Marine Corps Gazette 19, no. 3 (August 1935): 41–42; Heinl and Heinl, Written in Blood, 417, 456; Schmidt, United States Occupation of Haiti, 74–75; and Millett, Semper Fidelis, 199, 204.

- Heinl and Heinl, Written in Blood, 456–58, 464–67, 501–6; and Millett, Semper Fidelis, 208–10. The acquittals of those Haitians suspected of murdering werewolves is corroborated in McPherson, “The Irony of Legal Pluralism,” 1157–59.

- Gray memo.

- Gray memo. Current conversions show that 60 gourdes equal approximately $.62 (U.S. 2019).

- Gray memo.

- Gray memo.

- Heinl and Heinl, Written in Blood, 784–85.

- Carrol F. Coates, “Vodou in Haitian Literature,” in Invisible Powers, 193.

- Renda, Taking Haiti, 223–27.

- Gray memo.

- Silverthorn, oral history interview transcript, 160.

- C. I. Murray, memo to Commandant of the Garde d’Haiti, 25 January 1929, “Voodoo and Witchcraft Cases,” RG 127, A1, entry 21, NARA, 1, hereafter Murray memo.

- Murray memo, 1.

- Murray memo, 5.

- Murray memo, 5.

- Sometimes criminal cases were not pursued because of a lack of evidence, as seen in these two documents: District Commander, memo for the Department Commander, District of the Center, 25 July 1928; and Department Commander, District of the Center, memo for the Chief of the Gendarmerie, 27 July 1928, both in Sheldon Kennedy Personal Papers Collection, file 3248, Archives Branch, Marine Corps History Division, Quantico, VA.

- Harry Watkins, memo for Department Commander, Department of the North, 14 September 1927, “Voodoo and Witchcraft Cases,” RG 127, A1, entry 21, NARA, hereafter Watkins memo.

- Watkins memo.

- Watkins memo.

- Watkins memo.

- Gray memo; and Karen McCarthy Brown, “Afro-Caribbean Spirituality: A Haitian Case Study,” in Michel and Bellegarde-Smith, Invisible Powers, 1–26

- McPherson, “The Irony of Legal Pluralism,” 1159–60.

- The subsequent document of 1 October 1927 does not give Henley’s rant, but the rank of major is given in Navy Directory: Officers of the United States Navy and Marine Corps, October 1, 1928 (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1928), 38. See also John R. Henley to [?] Bevau, 1 October 1927, “Voodoo and Witchcraft Cases,” RG 127, A1, entry 21, NARA.

- See Enclosure to the District Commander, Cerca La Source, memorandum for the Department Commander, Subject: Report on Death of Emmanuel Philinmon, 25 July 1928, Seldon Kennedy File 3248, Historical Reference Branch, Marine Corps History Division, Quantico, VA.

- Review of The White King of La Gonave, Marine Corps Gazette 15, no. 5 (May 1931): 15; and Francis J. Jancius, “The Sergeant Wore a Crown,” Marian (October 1953): 5–6, in “Haiti” file, Historical Reference Branch, Marine Corps History Division, Quantico, VA. See also Faustin Wirkus and Taney Dudley, The White King of La Gonave (Garden City, NY: Doubleday, Doran, 1931). For another embellished work that helped to shape American consciousness of the Marines, Haiti, and Voodoo, see W. B. Seabrook, The Magic Island (New York: Harcourt Brace, 1929).

- Silverthorn, oral history interview transcript, 160.

- The word Haitianization is used in proper historical context of the early 1930s, as seen in “Agreement between the United States and Haiti for Haitianization of the Treaty Services, Signed August 5, 1931,” in Joseph V. Fuller, ed., Papers Relating to the Foreign Relations of the United States, 1931, vol. 2 (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1946), 403–6, on Office of the Historian, Department of State (website), accessed 20 December 2019.

- Pamphile, Contrary Destinies, 28–44. For overviews of the Marines’ withdrawal, see Vandegrift, Once a Marine, 58; McCrocklin, Garde d’Haiti, 1, 186; Scheina, Latin America’s Wars, 45–46; and Renda, Taking Haiti, 36.

- John H. Russell, “A Marine Looks Back on Haiti,” [ca. 1930s], Russell Papers, folder 6, box 3, Archives Branch, Marine Corps History Division, Quantico, VA, 35; and Russell, “Some Truths about Haiti,” [ca. 1930s], Russell Papers, folder 2, box 3, Archives Branch, Marine Corps History Division, Quantico, VA.

- Tillman, Dollar Diplomacy by Force, 81–82.

- Small Wars Manual, NAVMC 2890 (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1940), 1.

- Vernon Megee, letter to E. B. Miller, 24 April 1933, box 1, Vernon Megee Papers, Dwight D. Eisenhower Library, Abilene, KS. See also Da- vid J. Ulbrich, “Revisiting Small Wars: A 1933 Questionnaire, Vernon E. Megee, and the Small Wars Manual,” Marine Corps Gazette 90, no. 11 (November 2006): 74–75.

- Again, the author is grateful to the anonymous peer reviewers for suggesting integrating Small Wars Manual into this article.

- Counterinsurgency, FM 3-24/MCWP 3-33.5 (Washington, DC: Headquarters, Department of the Army, 2006).