PRINTER FRIENDLY PDF

EPUB

AUDIOBOOK

Politics aside, the Vietnam War differed from other American conflicts through the juxtaposition and immediacy of television and communication satellites. As young men fought and died half a world away, U.S. civilians could experience scenes of this conflict within hours from the serenity of their living rooms. Through the eye of the combat photographer, the ugly visage of battle could be tempered with the beauty of nature, cultural exchange, and innocence of youth. Sharing many of the same hardships as the fighters, the combat photographer’s battle is to understand the situation and their subject matter, all to better capture in still or moving images a moment of clarity, compassion, valor, or humanity.

One young American in uniform, Corporal William T. Perkins Jr., represented a typical 20-year-old Marine in Vietnam. However, whereas most carried a rifle into battle, Perkins deployed to Vietnam as a combat photographer armed with a Bell and Howell 16mm Filmo motion picture camera and his personal 35mm camera to record his fellow Marines’ efforts to support and defend the South Vietnamese people against the Communist Viet Cong and North Vietnamese forces. His photography, though, is perhaps less notable compared with Perkins’s heroic actions, which made him a posthumous recipient of the Medal of Honor; he is the only combat photographer ever so honored. Even less well known is the man himself, and the transformation he made from a spirited Southern California youth into a committed photographer and loyal Marine. Through his letters and personal photographs from the war, this article gives voice to a young Marine’s actions on the 50th anniversary of his death. Perkins’s own writings provide a critical opportunity to observe his transformation into a Marine and a photographer, but also to perhaps understand the reasoning behind his images and frame his ultimate act of selflessness.

Official portrait of Cpl William T. Perkins Jr., ca. 1966. Official U.S. Marine Corps photo

Early Life and Impact of Family

The driving force behind Perkins’s military service and pursuit of photography stems from the men in his life. Born in Rochester, New York, on 10 August 1947 to William and Marilane (née O’Leary) Perkins, young William, or “Butch” to his family, grew up with his younger brother Robert (19 May 1953–27 November 1978) hearing richly detailed stories of their great grandfather, grandfather, and father’s military service in the Civil War and in Europe and the Pacific during World War II.2 Their maternal great grandfather, Private John O’Leary, served with Battery L of the 1st New York Light Artillery from 31 December 1861 to 31 December 1864, participating in the battles of Antietam and Gettysburg.3 The boys’ grandfather, Captain Henry T. Perkins, commanded a U.S. Army special projects group of the Chemical Warfare Service in Guadalcanal, while their father, then-First Lieutenant William T. Perkins, flew 33 missions as a Consolidated B-24 Liberator bomber pilot with the Fifteenth Air Force stationed in Italy. During his fourth mission over Vienna, Austria, his aircraft lost two of four engines to flak and was forced down in German-occupied Yugoslavia. The young lieutenant and his crew spent the ensuing three weeks evading capture and managing to return to base.4

In 1960, the Perkins family crossed the country and moved to the suburb of Sepulveda (present-day North Hills) in Los Angeles, California. Although born in upstate New York, the teenage Perkins quickly acclimated to the temperate environs of Southern California. While attending James Monroe High School, he enthusiastically embraced new hobbies, such as snow skiing, swimming, skin and scuba diving, acting, and photography. He drew acclaim from fellow students for his performances in The Mouse that Roared and A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum. Undoubtedly, his comedic chops grew through countless moments shared with his good friend, James R. Priddy, mimicking the routines of Groucho Marx, Jonathan Winters, Lenny Bruce, and Bob Newhart in and out of class. After expressing an interest in photography, the senior Perkins bought his son a Kodak camera that he used to learn everything about the hobby while a member of the high school photography club.5

Boot Camp to Film School

After graduation in June 1965, Perkins enrolled at Los Angeles Pierce College to study photography. He continued refining his acting skills, apprenticing with the Valley Music Theatre and performing at the Century City Playhouse.6 Perhaps seeking to blend his love of acting and photography, Perkins applied to the University of California, Los Angeles, and received acceptance into its cinematography program, although, he was waitlisted for a year.7 For Perkins, a year seemed like an eternity. Shortly thereafter, on 27 April 1966, Perkins and Priddy—also enrolled at Pierce College— skipped class to drive to the beach. While on their drive, they spied a recruiting billboard featuring a copy of James Montgomery Flagg’s famous Uncle Sam painting pointing a finger at the men from a recruitment ad. Priddy broke the silence and said, “Let’s go join the Marine Corps!” That afternoon, both Perkins and Priddy enlisted in the Marine Corps Reserve, entering under the Marine Corps’ “Buddy Program,” whereby a recruit could enlist with a friend and attend boot camp in the same training platoon. In short order, Perkins and Priddy joined other young men from the San Fernando Valley in the Devil Dog Platoon on their way to basic recruit training with the 2d Recruit Training Battalion, Marine Corps Recruit Depot San Diego. On 6 July, the men were sworn into the Regular Marine Corps.8

The following day, 7 July, Perkins wrote home to his parents and younger brother. With youthful vigor and military innocence, he remarked,

Everything’s ok and we think we’re all going to make it ok. We’re waiting to be issued the rest of our utility uniforms. Jim and I are in separate huts right across from each other The food’s fine—always too much to eat, never not enough. You ought to see my haircut! Haven’t really done much except get bedding and learn how to make our racks (beds). They taught us how to salute and march a bit.9

Additional letters during the course of boot camp touched on the drill instructors’ mannerisms and Perkins and Priddy’s disposition to crack jokes:

Well, I guess the hardest thing yet is standing at attention for long periods of time which seem like eons sometimes—but we all get a chance to stretch our legs—march here—there—to mess etc.—runs to get in formation, to the head and back—also a lot of yelling—“aye aye, Sir,” Yes Sir, No Sir, and all that good stuff. We always have to repeat all orders and then say “aye aye, Sir.” We just had to stand and salute the flag. We just sat down and had to jump up and snap to for a lieutenant who roves around all the time with his .45 [pistol]—think he’d like to shoot or something—as Jim calls it “gunplay.” We were issued rifles the other day and Jim said, “When are we going to have a little gunplay.” HA! We got out a chuckle or two and had to all shut up.10

Note that what was obviously missing from his letters home are any repercussions for joking around; but fun aside, Perkins remained upbeat amid the mundane details of basic training.

Photography remained on Perkins’s mind as he continued training. On 13 July, Perkins and his platoon took a series of tests for intelligence and various areas of aptitude to screen the abilities of each recruit, a process changed after introduction of the Armed Services Vocational Aptitude Battery (ASVAB) in 1968. Perkins and Priddy scored well on their tests and each received an interview by a noncommissioned officer to help determine the potential career path of each recruit within the needs of the Corps. Perkins wrote of the experience to his family:

Then they took us for an interview, then some of us went for another interview (me). I told them I wanted to be a photographer and told them I had experience in school and on my own. A sergeant interviewed me and asked me a bunch of questions and then got specific and asked about photographic developing and printing—I answered 7 out of 8 right.

Well I guess he thought that was OK. He said he doesn’t guarantee anything but I “probably will get assigned as a photographer.” Well, that sure made me happy. But, I’m trying not to get my hopes up about it because it’s only one guy’s say so and he said probably and didn’t guarantee anything. Well, I hope I’ve got some good luck with me so I can get that job.11

Based on his other letters home during basic, Perkins apparently never heard any more about his desired career in the Service, but photography remained foremost on his mind. He mailed home several postcards from the post exchange to provide his family with a figurative snapshot of his training experience. In a letter on 3 August, he asked his mother if she ever developed some of his film and requested the prints “to find out if the time exposure of the moon came out, since I guessed at the exposure settings.”12

Perkins boards the bus that will take him to Marine Corps Recruit Depot San Diego, CA, and basic training, ca. July 1966. Jacobson Collection, photo courtesy of William T. Perkins Sr.

After additional training at Camp Pendleton, Perkins and his platoon graduated in early September. After 20 days leave, he shipped out for individual combat training with the 3d Battalion, 2d Infantry Training Regiment, Camp Pendleton, and received follow-on orders as a photographer with the Headquarters Battalion, Marine Corps Supply Center, Barstow, California.13 As a still photographer, Perkins found the work dull and unfulfilling. “All I do is take photos of the general in parades,” he told his family. At some point in the fall of 1966, Perkins requested assignment to the U.S. Army Signal Center and School at Fort Monmouth, New Jersey, to receive training in motion picture photography. His headquarters responded favorably to his request, but with a caveat: Perkins could attend the school, however, his follow-on assignment would likely include service in the Republic of Vietnam.14

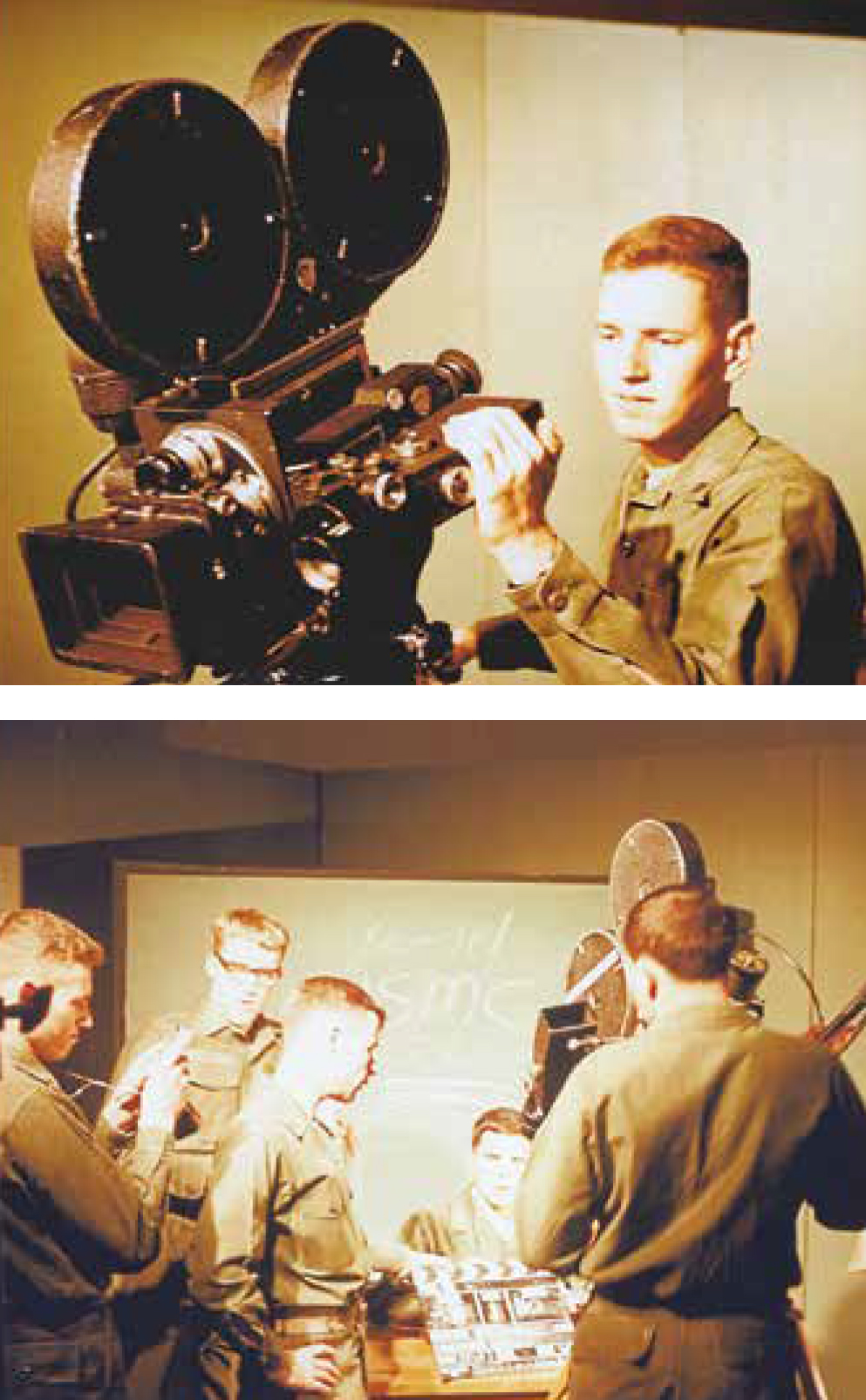

Undeterred, newly promoted Lance Corporal Perkins crossed the country and found himself immersed in the finer points of motion picture photography. Writing home on 26 January 1967, Perkins described the program’s first weeks:

Well, school is really pretty good. We’ve been awful busy. For the last 3 days, we started filming at 9:30 AM and wound it up at 3:00 PM. We shoot 300’ [of film]. We just had a phase test—there are 6 phases. It’s in two parts: the written and the practical. The written is self-explanatory—but I don’t like the way they try to trick you and are so petty on things which really don’t matter to any extent at all. This is the only thing I have against the school. The practical is where you get 100’ of 16 MM B&W [black and white] and go film specific things and sequences on a script.

We have whole movie scripts of acting out situations—just like a play or drama. We all have become actors. We screen the finished product—sometimes I watch my acting and forget I’m supposed to be watching the camera technique. HAH!

Although the course is very interesting and a lot of fun—It’s no snap. There’s so much to know about optics, camera technique, exposure, filters, framing, composition, and all the special effects, which make a motion picture look even half way realistic.

It’s really great to know all these techniques I’ve seen and now I’m using them—and on an almost, or I guess you could say professional level. I can’t believe how lucky I am to be doing exactly what [I want] to be doing—well that’s enough of my enthrallment!15

Coupled with his film education, Perkins found time to enjoy his hobby of scuba diving. In February, he joined a scuba club at the base and became an instructor, though a bit amused by the fact that he was a lance corporal issuing commands to several officers; by March, Perkins finished instruction of a scuba course for 50 Marines.16

“I’m in Vietnam Now”

Upon graduation from the motion picture photography school in April, Perkins returned to Barstow before shipping out to Vietnam. Arriving in Da Nang on 17 July 1967, he finally broke the news to his family of his whereabouts:

Dear Mom, Dad, and Bob—

I know this is going to probably be quite a shock to you, and I probably should have told you sooner, but I’m in Vietnam now. I could have told you sooner, but I just couldn’t stand all the tears and everyone moping around like it was the end of the world. Everyone thinks it’s such a big deal over here—like you’re supposed to get shot at getting off the plane—humbug. That just shows how the papers play it up big and how ignorant the public is. I’m going to be in the 3rd Marine Division Photo Lab in Phu Bai. We’ll stay here in Da Nang for the night and move out tomorrow by [Lockheed] C-130 [Hercules transport] or helicopter.

You probably heard the Da Nang Air Strip got mortared Friday. We heard the same thing in Okinawa and expected to see the place demolished—humbug—you can’t even see any evidence of it except for an Air Force ammo dump, which was hit on the perimeter. I don’t want to make it sound all rosy over here because it isn’t. It’s just that you don’t have to worry in a large compound like Chu Lai, Da Nang, Phu Bai, Hue, or Saigon because it’s so well protected. Hardly anyone carries weapons around the base except for guys who are just coming off missions—so it’s pretty secure. The worst thing about this place isn’t the V. C. [Viet Cong] but the heat!—Wow. You sweat 24 hrs. a day—just like Okinawa. In fact, Okinawa seems more humid than here.

Speaking of Okinawa, I found Jim [Priddy] and we went out to town Friday night and had the greatest time I think I ever had. Jim really has it nice over there as far as liberty goes.

Since I haven’t gotten to my unit yet, I can’t tell you my address. I’ll still mail this right away so you aren’t wondering where I am. I guess me being here is going to take some getting used to for all of us—but don’t worry about me—as long as it doesn’t get over 130° I’ll be fine—ha! (Well, maybe not 130°).

Well, I’d better go to chow now. I put an address on the envelope, but don’t send me a letter till you get my complete address. I’m sure you all have a million questions, so write ’em down and I’ll answer them.

Love, Butch

P.S. Again, I’m sorry I didn’t tell you sooner, but I really thought I’d be in Okinawa at least 2 or 3 wks.17

Perkins arrived in Phu Bai the following day, assigned as a photographer with Service Company, Headquarters Battalion, 3d Marine Division (Reinforced). Meeting up with fellow Marines from Barstow and Pendleton, he familiarized himself with the base and the surrounding areas in I Corps, documenting Marine activities.18 Initial assignments took Perkins to Dong Ha, Cam Lo, and Hue, but also required additional duties, including working in the photography lab developing still prints. In a letter from 27 July, Perkins explained his job:

We get a lot of work in because we have 9 still photographers whose film we develop and only 5 motion picture (including me) people. All our motion picture [film] is 16MM Ektachrome color and is sent to Washington [DC] to be developed. They send a print back so you can see your footage. All still stuff is developed here (B&W and color slides). B&W cameras are mostly 35MM and then some 2¼ x 2¼ and 4 x 5 (speed graphic). Our biggest developing and printing is aerial photography, which we rarely shoot, but is always sent to us for processing. I’m the one who prints most of it. One good thing—our print room is in a portable van and is air conditioned!19

Headquarters issued Perkins a Bell and Howell 16mm Filmo motion picture camera along with a.45-caliber automatic pistol. While the latter frequently remained holstered, the Bell and Howell proved Perkins’s primary weapon in the field.

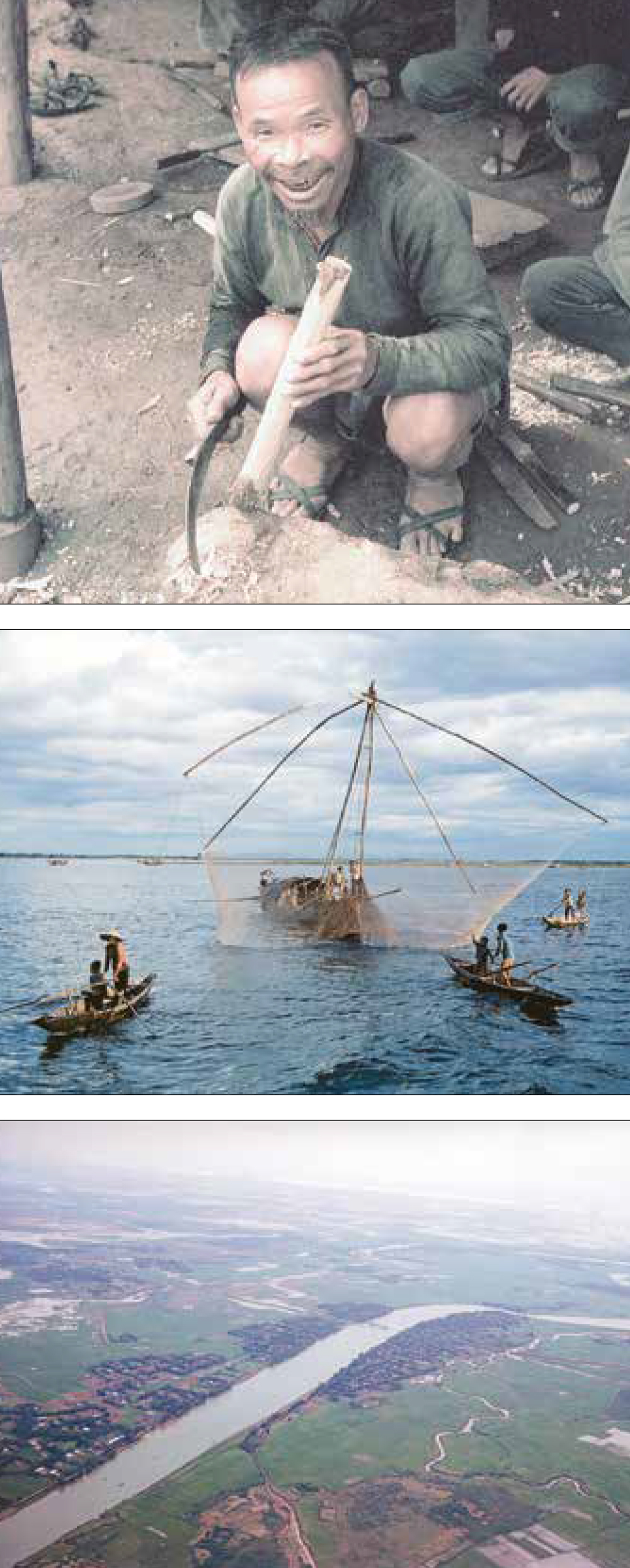

In addition to his Bell and Howell motion picture camera, Perkins also carried his own personal 35mm still camera. He came to Vietnam with the Kodak his father had given him many years before. After receiving a promotion to corporal on 1 August, Perkins bought a new Canon single lens reflex camera. He later purchased a second Canon, which he gave to his father as a thank you present, aided, in part, by the low prices at the post exchange.20 With his Canon, Perkins began taking photographs of the Vietnamese people, the countryside, and his fellow Marines. He mailed his exposed film back to California, “because I don’t have enough time to do my own [developing] and they frown on you using government material.”21 In his successive letters home, Perkins mailed rolls of black-and-white and color film with specific instructions on where to develop the film and to protect his slides from dust and moisture.22

Perkins on 26 January 1967: “Although the course is very interesting and a lot of fun—it’s no snap. There’s so much to know about optics, camera technique, exposure, filters, framing, composition, and all the special effects which make a motion picture look even half way realistic.” As a student in the motion picture photography school, U.S. Army Signal Center and School, Fort Monmouth, NJ, Perkins works with a Mitchell 35mm motion picture camera as he and fellow students practice making a reenlistment film. Jacobson Collection

These still photos increasingly became a focus for Perkins’s letters home. These letters clearly demonstrate the growing pride in his budding identity as a professional photographer:

12 September 1967: P. S. I’m expecting my prints and slides in the mail (Hint! Hint!)23

15 September 1967: Excuse me, but I’d like to correct you on something. You call my photos “snaps” or “snapshots.” I cringe every time I hear that. It’s like calling a rifle a gun, if you know what I mean. Snapshots are taken with a little brownie box camera.24

21 September 1967: I’ve just been shooting still photography around the base here at Dong Ha. I’m going nuts waiting for you to send me my photos and slides! Please send them to me. I don’t plan to keep them here because of the moisture, etc., and I will send them right back. I just want to see if they’re any good. I’ve been waiting for weeks now— PLEASE SEND THEM!25

2 October 1967: Make sure you’re keeping my negatives in a dust free place and not getting handled. When I get home, I plan to have enlargements made of some—that’s why I sound so particular.26

7 October 1967: Hate to keep talking about my photos all the time, it probably bores you all. But—I did like some of my slides and think they ought to give you a good idea of the country side [sic] and people. Just keep all slides and negatives dust free and out of the dampness. I don’t care too much about the B&W prints because I can always print more from the negatives.27

Perkins on 3 September 1967: “I caught a flight up here to Dong Ha today and wasn’t here more than an hour and we caught incoming mor- tars and rockets. I guess you probably heard about it on the news be- cause they blew up the ammo dump. I had my new Canon out there and got quite a few color photos, and let my buddy take a couple of me with explosions in the background and the whole bit.” Jacobson Collection

Perhaps truly understanding Perkins’s concern for his photography revolves around the Marine subjects within his films and still photographs. His mother, Marilane, volunteered in California as a charter member of the San Fernando Valley Chapter of the Mothers of Marines (MOMS) that mailed care packages to the Marines in Vietnam.28 Perkins recommended that his mother’s group send packages to “a group of grunts—infantrymen. You can’t imagine how lousy they have it. They live and eat as well as pigs but are the greatest bunch of guys over here.”29 One particularly moving assignment on 20–21 September 1967 evoked a greater request for aid:

I was out at Con Thien yesterday and today. All it is is a slight hill about 2,500 yards from the DMZ [demilitarized zone] and all mud. I have never been in such a terrible place in my life. It was really a hell hole [sic]. We took in over 200 artillery rounds in the compound inside of 15 minutes. About every 25’ there is a bomb crater. They didn’t know what it was going to be like when they sent us there. It was impossible to take pictures because of the artillery and the rain, so the other photographer and I stayed in a bunker most of the time and left as soon as possible by chopper. Luckily the mud prevented the rounds from exploding as much as they should and threw more mud than anything. The artillery wasn’t the bad thing though. The worst thing was the way these guys lived, covered from head to toe with mud without washing for weeks at a time. They had no tents, only holes with ammo boxes filled with mud around the holes. The lucky people had a top or roof. They had water flown in everyday, but not much. They lived only on C rations. Now, if your organization, MOMS, is going to send anything to anyone—it should be these guys. Believe me that place was unbelievable. Dong Ha is like the City Park compared to Con Thien. After that experience, they decided not to send anyone up there for a good while.30

How Con Thien changed or reinforced Perkins’s thinking of his own mortality is unknown, but the experience undoubtedly reinforced his commitment to support his fellow Marines.

Perkins on 23 August 1967: “I’m going from Phu Bai to Dong Ha to pick up a camera and then come back. I’ve almost finished a roll of color slides, which I will send home to be developed. I think the slides are of the people and the countryside. A few I shot from a helicopter.” Jacobson Collection

Perkins on 12 September 1967: “I’m up at the mouth of the Cua Viet River with the Swift Boat patrol to shoot another story. We plan to shove off at 7:30 AM tomorrow and patrol south of the Cua Viet [river] on the South China Sea inspecting sampans, junks, etc. that may be carrying Communist weapons.” Jacobson Collection

Operation Medina

Three weeks after visiting Con Thien, Perkins received an assignment to film Marine forces in the field. For months, the 3d Marine Division lacked sufficient forces to find, fix, and destroy enemy base areas that threatened positions at Con Thien, Khe Sanh, Dong Hai, and Phu Bai. The area of concern the enemy knew as Base Area 101, supporting the 5th and 6th North Vietnamese Army (NVA) Regiments, located in the Hai Lang National Forest south of Quang Tri. In early October 1967, the 1st Marine Regiment’s 1st and 2d Battalions came under the 3d Marine Division’s operational control. These forces, reinforced with the 1st Battalion of the 3d Marine Regiment and two battalions of the 1st Division of the Army of the Republic of Vietnam (ARVN), would destroy any and all enemy forces in the forest. The operation would involve the 1st and 2d Battalions of the 1st Marine Regiment sweeping through the forest, pushing the enemy into a blocking force from the 1st Battalion of the 3d Marine Regiment.31

Perkins on 7 October 1967: “I’ve done a lot of medevac photography— sometime they may tell me not to shoot so much.” Perkins (second from left) films a medevac on the afternoon of 12 October 1967 during Operation Medina, two hours before he is killed in battle. Defense Department photo (Marine Corps), courtesy of Leatherneck

On 11 October, the men of the 1st Battalion, 1st Marine Regiment, commenced the operation. Perkins, Leatherneck magazine correspondent Staff Sergeant Bruce Martin, and Marine correspondent Staff Sergeant Philip F. Hartranft Jr. accompanied the men of Charlie Company of the 1st Battalion, 1st Marines. Perkins and Hartranft paired up, the former filming operations with the latter providing print coverage. While waiting for a Marine Sikorsky UH-34 Choctaw helicopter to airlift the men into the forest, Perkins asked Hartranft about life back in the United States, while in turn sharing information with the older correspondent about things to look out for in the field.32 Early in the afternoon, the company landed at Landing Zone (LZ) Dove, secured the perimeter, regrouped, and moved out toward its first objective. Loaded with extra weapons and supplies, the men marched slowly and methodically, using machetes to hack trails through thick, razor-sharp elephant grass, tangled vines, and vegetation before entering the triple-canopy forest. After several hours, the column came to a small river and, after one Marine swam across and secured a rope, the remainder of the men moved hand over hand to complete the crossing. All during the trail and river crossings, Perkins moved around the Marine column, filming their movements from various angles.33

On the afternoon of 12 October, NVA forces ambushed the lead element of 3d Platoon on a jungle trail in a shower of grenades, machine-gun, and sniper fire. Enemy fire dropped several of the Marines at the front of the column. As the ambush intensified, 1st Platoon established a defensive perimeter behind 2d and 3d Platoons on the higher ground of a knoll adjacent to a trail, where they cleared fields of fire. Marines used explosives and chainsaws to clear an opening in the jungle for an LZ to medevac the wounded. Perkins meanwhile took up position by a log on the edge of the new LZ perimeter with three men of 3d Platoon: Corporal Frederick A. Boxill and Lance Corporals Michael P. Cole and Dennis J. Antal. As the four Marines peered into the foreboding forest for signs of the enemy, Antal struck up a conversation with Perkins about California life, perhaps to break the tension of the moment.34

The UH-34 medevac helicopters arrived to fly out the 11 wounded and one killed from the initial ambush.35 Perkins filmed the entire operation as those able loaded the wounded on stretchers and placed them aboard the helicopters. Just as the last medevac chopper departed the clearing in the dusk’s fading light, all hell broke loose. Charlie Company found itself under assault by three NVA companies on two sides. Enemy concussion and fragmentation grenades rained down on the Marines from NVA soldiers who were tied high up in the trees on the perimeter’s edge. Green tracers of the enemy weapons slashed across the American lines as friendly red tracers answered back, the roar of battle punctuated by screams of the wounded. Enveloped by darkness, Antal, Boxill, Cole, and Perkins returned enemy fire into the forest from their position by the log at the south side of the perimeter. Incoming enemy fire flew over their heads as 3d Platoon continued to sustain casualties, holding off the brunt of the enemy attack.36

As the NVA pressed the attack, increasing Marine casualties opened gaps in the defensive perimeter, particularly between 2d and 3d Platoons. Captain William D. Major, Charlie Company commander, ordered First Lieutenant Jack A. Ruffer, commanding 1st Platoon, to plug the gap. Under fire from three sides, Charlie Company faced a dire situation. Ruffer, order in hand, cried out above the roar of battle, “Let’s go get some!,” then unleashed the Marine Hymn at the top of his lungs. Other Marines joined with Ruffer and, brandishing his pistol, the lieutenant hollered, “Let’s go Charlie!,” and charged down a trail separating the platoons. Marines rose up from their fighting positions and followed suit, including Perkins with his pistol. Staggered and perhaps shocked at the Marines’ élan, the enemy forces pulled back as Ruffer’s men regrouped and charged a second time, pushing the NVA out of the Marine lines at the LZ perimeter. With the Marine position strengthened, enemy fire dissipated, allowing a medevac helicopter to bring out several of the wounded.37

After Ruffer’s charge, Perkins made his way back to the log on the LZ perimeter, accompanied by Boxill and Antal. Cole was located about 10 feet behind the three men, higher up the knoll’s slope. Nearby in the darkness, Ruffer could clearly see the glow from the face of Perkins’s Zodiac Sea Wolf dive watch. Enemy grenades began to roll from the top of the knoll down toward Cole’s position. A blast from one concussion grenade threw him down the hill. Suddenly, an enemy grenade appeared in the air, silhouetted against the flash of another explosion. Antal saw the grenade falling, as did Perkins. Propping himself up on his arms, Perkins cried out, “Incoming grenade!,” as the explosive landed behind the log, three feet from Antal, Boxill, and Private First Class Horace M. Roberts. Perkins dove at the grenade, kicking Antal in the process, and tucked it securely beneath his chest. In an instant, the grenade exploded, lifting Antal in the air as shrapnel wounded both him and Boxill. As a fellow Marine treated the two wounded men, a corpsman arrived to check on Perkins. When Antal asked, “Is he all right?,” the corpsman shook his head.38

This Bell and Howell 16mm Filmo motion picture camera was carried by Cpl Perkins when he smothered a grenade during Operation Medina on 12 October 1967. The damage from the grenade shrapnel to the camera is evident in the photo. The camera is now in the collection of the National Museum of the Marine Corps. Jacobson Collection

Charlie Company continued to hold out against fierce enemy fire for the remainder of the night. Between 2100 and 2200 hours, Delta Company pushed forward to reinforce Charlie Company, and together the companies pushed back the NVA assault after four uninterrupted hours of combat. Under the protective glow of a quarter moon, the enemy and incoming fire faded away as the Marines secured the perimeter and the corpsmen ministered to the wounded and the dying. When dawn broke on 13 October 1967, 8 Marines—including Perkins—lay dead, 39 men were wounded, and 40 of the enemy lay dead scattered in and around the LZ perimeter. That morning, a Marine helicopter flew Perkins’s body from the battlefield. A Marine also located Perkins’s Bell and Howell camera, riddled with shrapnel, and handed it to Hartranft with news that the combat photographer had died. The following day, the Marines policed up the LZ and prepared to destroy any unusable equipment, piling everything into a heap and wiring it with C-4 explosives. Just prior to detonation, combat artist Major A. Michael Leahy, who arrived at the battlefield the day before, spied a green corpsman’s bag on the pile that seemed out of place. Upon inspection, he found that the bag belonged to Perkins and it held his undeveloped film. Leahy returned the film to Marine headquarters back in Phu Bai, ensuring the preservation of Perkins’s footage of Charlie Company’s actions prior to the battle on 11–12 October.39

Medal of Honor

Charlie Company did not forget the selfless sacrifice made by Perkins, but having only just joined the company as a photographer, not a regular member, his identity initially remained unknown. His actions saved the lives of Antal, Boxill, Roberts, and possibly Ruffer; however, none of the men knew Perkins since he was officially assigned to Service Company, Headquarters Battalion, 3d Marine Division. As news of his death reached Perkins’s hometown of Rochester, New York, Charlie Company’s commander, Captain Major, was gathering evidence of Perkins’s actions from survivors of the battle. Several eyewitness accounts provided convincing circumstantial evidence that Perkins was the Marine who smothered the grenade with his own body. Perhaps the key detail for a positive identification was his dive watch, whose highly illuminated face had stood out in the darkness of the LZ perimeter.40

On 27 November 1967, Major submitted an award recommendation for the Navy Cross on Perkins’s behalf. Without eyewitness statements definitively identifying the Marine, Major could not submit Perkins for the Medal of Honor. After a review of his case at 3d Marine Division headquarters, the Navy Cross recommendation moved up the chain of command until reaching the desk of Lieutenant General Frank C. Tharin, acting commanding general, Fleet Marine Forces, Pacific. General Tharin, after reviewing the recommendation, noted that “Corporal Perkins’ actions may meet the eligibility requirement for the Medal of Honor.”41 He therefore requested an additional investigation into Perkins’s actions. Two weeks later, Headquarters, 3d Marine Division photographic officer, First Lieutenant James E. Tyler, provided key corroborating evidence to the 3d Marine Division’s awards officer, specifically that Perkins had been assigned a pistol and typically wore a Zodiac watch, which was recovered from his body and returned to his family.42 In light of the new information, General Robert E. Cushman Jr., commanding general, III Marine Amphibious Force, recommended to Secretary of the Navy Paul R. Ignatius that Perkins be awarded the Medal of Honor.43

In a private ceremony at the White House on 20 June 1969, President Richard M. Nixon presented Corporal Perkins’s posthumous Medal of Honor to William and Marilane Perkins. The citation accompanying the decoration proclaimed:

For conspicuous gallantry and intrepidity at the risk of his life above and beyond the call of duty while serving as a combat photographer attached to Company C. During Operation Medina, a major reconnaissance-in-force southwest of Quang Tri, Company C made heavy combat contact with a numerically superior North Vietnamese Army force estimated at from two to three companies. The focal point of the intense fighting was a helicopter landing zone which was also serving as the Command Post of Company C. In the course of a strong hostile attack, an enemy grenade landed in the immediate area occupied by Corporal Per- kins and three other marines. Realizing the inherent danger, he shouted the warning, “Incoming Grenade” to his fellow marines, and in a valiant act of heroism, hurled himself upon the grenade absorbing the impact of the explosion with his own body, thereby saving the lives of his comrades at the cost of his own. Through his exceptional courage and inspiring valor in the face of certain death, Corporal Perkins reflected great credit upon himself and the Marine Corps and upheld the highest traditions of the United States Naval Service. He gallantly gave his life for his country.44

As part of the ceremonies, Major Leahy also presented the family with a painting, Medina Photographer, depicting Perkins fording the small stream on the way to the eventual landing zone and the actions that would mean his death.45

The Medal of Honor presentation for Cpl William T. Perkins Jr. at the White House on 20 June 1969. From left: William T. Perkins Sr., Marilane Perkins, Senator George Murphy (R-CA), President Richard M. Nixon, and Representative Barry Goldwater Jr. (R-CA). Mrs. Perkins holds her son’s Medal of Honor. Jacobson Collection

Fifty years after his heroic sacrifice, Perkins’s actions continue to inspire Marine Corps combat photographers. On 11 April 1972, the Marine Corps again honored Perkins by dedicating the 2d Marine Division Photographic Laboratory at Camp Lejeune, North Carolina, in his honor.46 In 1970, the U.S. Marine Corps Combat Correspondents Association created the Corporal William T. Perkins Jr. Memorial Chapter, and in 2005, established the Corporal William T. Perkins Award for Combat Cameraman of the Year, featuring a statuette of Perkins kneeling with his Bell and Howell camera.47

Perkins’s camera, bearing the scars of an enemy grenade and dirt from the Hai Lang forest, is preserved in the collection of the National Museum of the Marine Corps. In the Medal of Honor section of the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History exhibition The Price of Freedom: Americans at War, visitors can view Perkins’s Medal of Honor and Purple Heart. These decorations accompany Perkins’s Bell and Howell camera on loan, the first time Perkins’s camera and Medal of Honor have ever been presented together. Perkins’s films from his time in Vietnam re- main available for viewing at the National Archives in College Park, Maryland. His footage captures the faces and actions of the Marines of I Corps; images preserved by a selfless young man whose love of country and photography made him a national hero.

Medina Photographer by Maj A. Micheal Leahy. Art Collection, National Museum of the Marine Corps

•1775•

Endnotes

- Frank A. Blazich Jr. is currently a curator of modern military history in the Division of Armed Forces History at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History. He earned a doctorate in modern American history from the Ohio State University in 2013 and worked for Naval History and Heritage Command prior to joining the Smithsonian.

- “Born to Mr. and Mrs.,” Democrat and Chronicle (Rochester, NY), 24 May 1953, 22.

- “Battery L (Reynolds), 1st New York Light Artillery, Oration of Gen. John A. Reynolds,” 17 September 1889, Marilane Jacobson Collection, Division of Armed Forces History, National Museum of American History (NMAH), Smithsonian Institution, hereafter Jacobson Collection.

- Doyle D. Glass, Lions of Medina (Louisville, KY: Coleche Press, 2007), 3; “Biographical Data for Corporal William T. Perkins, Jr., USMC (Deceased),” Historical Reference Branch, Marine Corps History Division, Quantico, VA, hereafter Perkins Biographical Data; and “Flyer, Captain Father Meet at Home on Army Leave,” Democrat and Chronicle (Rochester, NY), 28 June 1945, 12.

- Glass, Lions of Medina, 3, 60; “President Awards Medal of Honor to Valley Marine,” Van Nuys (CA) News, 22 June 1969, 18; and “Local Marine Wins Medal of Honor,” news clipping, file labeled “Published Material, Perkins, William T., Jr., Cpl, USMC, MOH,” hereafter Perkins published materials, Historical Reference Branch, Marine Corps History Division, Quantico, VA.

- “Local Marine Wins Medal of Honor”; and “President Awards Medal of Honor to Valley Marine,” 18.

- Glass, Lions of Medina, 10.

- Glass, Lions of Medina, 10–11; Perkins Biographical Data; “President Awards Medal of Honor to Valley Marine,” 18; and “Marine Buddy Program,” Cardunal Free Press (Carpentersville, IL), 23 December 1968, 30.

- William T. Perkins Jr. to William Sr., Marilane, and Robert Per- kins, 7 July 1966, Jacobson Collection.

- William T. Perkins Jr. to William Sr., Marilane, and Robert Perkins, 10 July 1966, Jacobson Collection.

- William T. Perkins Jr. to William Sr., Marilane, and Robert Perkins, 13 July 1966, Jacobson Collection. Emphasis in original is underlined.

- William T. Perkins Jr. to William Sr., Marilane, and Robert Perkins, 3 August 1966, Jacobson Collection.

- Perkins Biographical Data.

- Glass, Lions of Medina, 37.

- William T. Perkins Jr. to William Sr., Marilane, and Robert Per- kins, 26 January 1967, Jacobson Collection. Emphasis in original is underlined.

- William T. Perkins Jr. to William Sr., Marilane, and Robert Perkins, 7 February 1967; William T. Perkins Jr. to William Sr., Marilane, and Robert Perkins, 29 March 1967, Jacobson Collection; and “President Awards Medal of Honor to Valley Marine,” 18.

- William T. Perkins Jr. to William Sr., Marilane, and Robert Perkins, 16 July 1967, Jacobson Collection; “News Release No. KTW-101-69,” 20 June 1969, Perkins published materials, Histori- cal Reference Branch, Marine Corps History Division, Quantico, VA. The letter is dated 16 July, as Perkins had crossed the International Date Line, ergo he arrived in Vietnam on what would be 17 July in the United States. Emphasis in original is underlined.

- Perkins Biographical Data; and William T. Perkins Jr. to William Sr., Marilane, and Robert Perkins, 17 July 1967, Jacobson Collection.

- William T. Perkins Jr. to William Sr., Marilane, and Robert Perkins, 27 July 1967, Jacobson Collection. Emphasis in original is underlined.

- Perkins Biographical Data; William T. Perkins Jr. to William Sr., Marilane, and Robert Perkins, 30 September 1967, Jacobson Collection, hereafter Perkins 30 September letter; William T. Perkins Jr. to William Sr., Marilane, and Robert Perkins, 9 September 1967, Jacobson Collection; and Glass, Lions in Medina, 60. In his letter on 19 August 1967, Perkins mentions that he saw his Canon “at Hopper Camera Shop for $286 and [it] cost me $94 [at the Post Exchange]—it’s a real gem. Ha!” See William T. Perkins Jr. to William Sr., Marilane, and Robert Perkins, 19 August 1967, Jacobson Collection, hereafter Perkins 19 August letter.

- William T. Perkins Jr. to William Sr., Marilane, and Robert Perkins, 9 August 1967; Perkins 19 August letter; and Perkins Biographical Data.

- William T. Perkins Jr. to William Sr., Marilane, and Robert Perkins, 23 August 1967, Jacobson Collection; William T. Perkins Jr. to William Sr., Marilane, and Robert Perkins, 24 August 1967, Jacobson Collection; and Perkins 30 September letter.

- William T. Perkins Jr. to William Sr., Marilane, and Robert Perkins, 12 September 1967, Jacobson Collection.

- William T. Perkins Jr. to William Sr., Marilane, and Robert Perkins, 15 September 1967, Jacobson Collection, hereafter Perkins 15 September letter.

- William T. Perkins Jr. to William Sr., Marilane, and Robert Per- kins, 21 September 1967, Jacobson Collection, hereafter Perkins 21 September letter. Emphasis in original is actually underlined.

- William T. Perkins Jr. to William Sr., Marilane, and Robert Perkins, 2 October 1967, Jacobson Collection.

- William T. Perkins Jr. to William Sr., Marilane, and Robert Perkins, 7 October 1967, Jacobson Collection.

- “President Awards Medal of Honor to Valley Marine,” 18.

- Perkins 15 September letter.

- Perkins 21 September letter.

- Gary L. Telfer, Lane Rogers, and V. Keith Fleming Jr., U.S. Marines in Vietnam: Fighting the North Vietnamese, 1967 (Washington, DC: History and Museums Division, Headquarters Marine Corps, 1984), 139; and Glass, Lions of Medina, 123–25.

- Glass, Lions of Medina, 127–28.

- Glass, Lions of Medina, 133–35.

- Glass, Lions of Medina, 152–58.

- Bruce Martin, “ ‘Let’s Go Charlie!’,” Leatherneck 51, no. 2, February 1968, 31–32.

- Glass, Lions of Medina, 164–76; and Martin, “ ‘Let’s Go Charlie!’,” 32–34.

- Glass, Lions of Medina, 178–79, 185–95; and Martin, “ ‘Let’s Go Charlie!’,” 34

- Glass, Lions of Medina, 198–200; and Statements of Cpl Larry J. Dalrymple, Sgt Harry W. Poole, LCpl Fredrick A. Boxill, LCpl D. J. Antal, PFC H. M. Roberts, attachments to memo from CaptW. D. Major to Commanding Officer, Service Company, Headquarters Battalion, 3d Marine Division (Rein), FMF, on “Navy Cross Medal; recommendation for; case of Corporal William T. Perkins, USMC,” 27 November 1967, file labeled “Perkins, William T., Jr., Cpl USMC MOH Award Recommendation,” hereafter Perkins MOH file, Historical Reference Branch, Marine Corps History Division, Quantico, VA, hereafter Major memo.

- Glass, Lions of Medina, 223–33; Martin, “ ‘Let’s Go Charlie!’,” 34–35; and Telfer, Rogers, and Fleming, U.S. Marines in Vietnam,141. Glass’s description of the cameras appears to be in error. He mentions that someone handed Perkins’s still camera (most likely his Canon) to Hartranft and that Leahy found a movie camera in the bag. The Bell and Howell camera Perkins had on his per- son, riddled with shrapnel, is on display at the National Museum of the Marine Corps (NMMC) in Quantico, VA. Given the nature of the event, it is doubtful that someone would have known to pick up this camera and place it back inside the camera bag, while handing Hartranft Perkins’s presumably undamaged still camera. Leahy kept it and Perkins’s camera bag, before returning it to Perkins’s father, who in turn donated it to the museum. See Michael Leahy letter to Judy and William Perkins, 19 May 2005, accession file for camera bag, Cpl William T. Perkins Jr., NMMC.

- Statements of Cpl Larry J. Dalrymple, LCpl D. J. Antal, PFC H. M. Roberts, attachments to Major memo; and “Marine Dies in Vietnam of Wounds,” Democrat and Chronicle (Rochester, NY), 24 October 1967, 18.

- Memo from Commanding General, Fleet Marine Forces, Pacific to Commanding General, III Marine Amphibious Force (III MAF), “Navy Cross; posthumous recommendation for, case of Cpl William T. Perkins, USMC,” 5 February 1968, Perkins MOH file, Historical Reference Branch, Marine Corps History Division, Quantico, VA, hereafter CG MOH memo.

- Major memo; CG MOH memo; and memo from J. E. Tyler to Awards Officer, III MAF, “Information concerning Cpl William T. Perkins, USMC,” 19 February 1968, Perkins MOH file, Historical Reference Branch, Marine Corps History Division, Quantico, VA.

- CG MOH memo.

- Office of Assistant Secretary of Defense (Public Affairs), “Medal of Honor Citation for William T. Perkins, Jr., Corporal, USMC, Posthumously,” press release, 20 June 1969, Perkins published material, Marine Corps History Division, Quantico, VA.

- “President Awards Medal of Honor to Valley Marine,” 1. Special thanks to Erik Koglin of Murfreesboro, TN, for his digital restoration of the watercolor. Exposure to ultraviolet light caused the blacks to fade. This image merges the current color artwork with a 1967 black-and-white photo of the original.

- Joint Public Affairs Office, Camp Lejeune, NC, “Dedication, Perkins’ Memorial,” press release, 21 April 1972, Perkins published material, Marine Corps History Division, Quantico, VA.

- “Charter certificate for United States Marine Corps Combat Correspondents Association Corporal William T. Perkins, Jr. Memorial Chapter,” 26 July 1970, Jacobson Collection; “Perkins Award Presented,” USMCCCA.org, 7 February 2015; Thomas Brennan, “Lejeune Videographer to Receive Coveted Award,” Daily News (Jacksonville, NC), 23 July 2013; and Jack T. Paxton, telephone intvw with author, 4 August 2017. The award is presented annually to the best combat cameraman in the Marine Corps as judged by their peers.