PRINTER FRIENDLY PDF

EPUB

AUDIOBOOK

“Classes will be conducted not at the school blackboard, but right in the family parlor.”

~Henry Salomon, screenwriter2

Movies, like their television counterparts, serve not only to educate but also to inform the populace of the historical events of the past. As was noted in Robert A. Rosenstone’s book History on Film, Film on History, historically based films can serve as a way to preserve the past; however, if the images and story are compelling enough, the history takes on its own life.3 Often, events can be more “real” in a visual form than a history book can portray. Cable television company Home Box Office (HBO) delved into this field early on and has created several mini-series that attempt to honor the actions of World War II combatants from specific units. What started with the miniseries Band of Brothers, about Easy Company of the U.S. Army’s 506th Parachute Infantry Regiment, 101st Airborne Division, was continued with the series that told of the struggles endured by the U.S. Marines of the 1st Division in the Pacific theatre, entitled The Pacific.4 The stories of the men in the miniseries were woven through the history of fighting in the Pacific theatre from Guadalcanal to Okinawa and finally acclimatization into the civilian world.

This second series was an attempt from executive producers Steven Spielberg and Tom Hanks not merely to show the conflict that has been a part of many other programs, but also to break the myth of the war in terms often depicted in such films as Sands of Iwo Jima (1949).5 The Pacific showed the violence and anguish that the Marines faced while on islands no one had ever heard of, fighting not only a fanatical enemy but the very terrain and elements as well. While the series attempted to break the stereotypes of an honorable and sterile war—especially in an era of drone strikes, urban enemy combatants, and two of the longest wars in American history where few understood the goals to be achieved—The Pacific resonated with some viewers as a way to describe the parallels to combat in the twenty-first century.

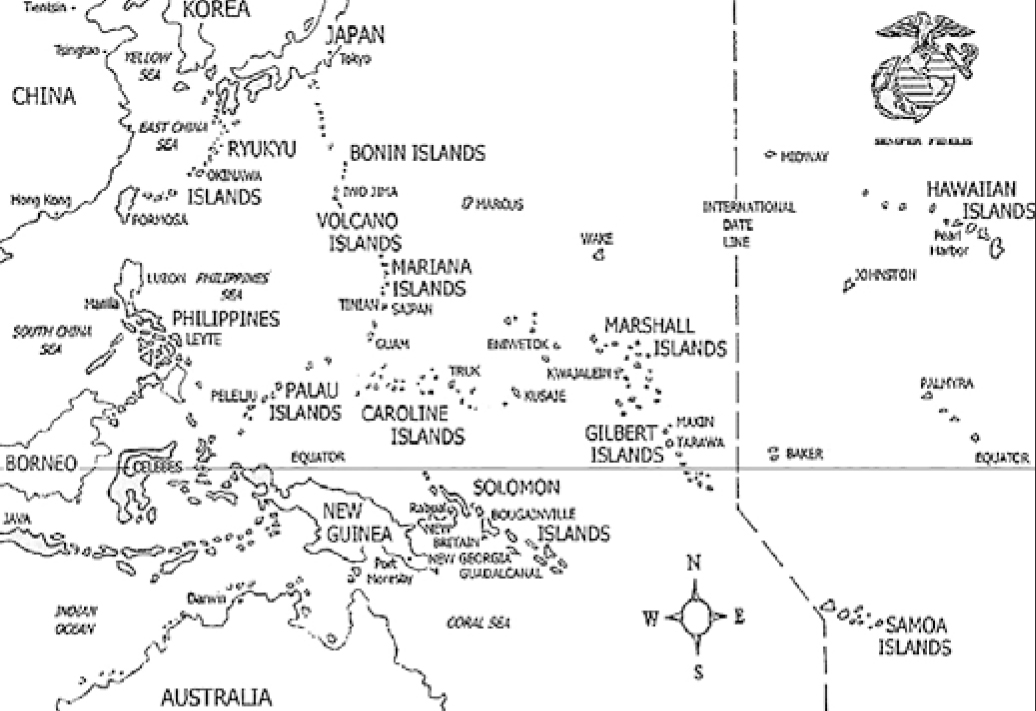

U.S. Marine Corps activities in the Pacific. Adapted by History Division

One of the biggest issues with this depiction is how the public has come to form its popular image of the Marines, the conditions in which they fought, and the fighting itself during World War II. While many historians note that visual media, such as television shows or movies, can never truly capture the brutal realities of combat, the consensus is that some movies have clearly come closer than others in terms of the historical accuracy of equipment, tactics, and events. This concept is not without controversy however. This article addresses the public perceptions versus the documented conditions portrayed in the HBO miniseries The Pacific, particularly regarding how the academic community tries to rectify the public’s conception of the Marine Corps’ heroic persona in WWII against the historical record. For some viewers, and possibly the military Services as well, perception has often taken a form that cannot be reconciled with the record.

Timeframe of The Pacific

When The Pacific series was in development, the United States was in the middle of both the Iraq and Afghanistan wars. At the time of production, the “surge” was ebbing in Iraq, and II Marine Expeditionary Force (II MEF) was in Iraq, while 2d Marine Expeditionary Brigade was in Afghanistan. As if holding a mirror to the American conscience, the television series was meant to show the sacrifices of U.S. servicemen in the Pacific as well as give people a better sense of the overall brutality of the Second World War, specifically, and of war, in general. The series also made it easy to draw comparisons between events depicted by the cast and those being reported on during the time the series aired; for example, many Americans saw the Taliban or the Iraqi combatants carrying out acts of terror against U.S. servicemembers and civilians.

The budget and production values for The Pacific were substantial by Hollywood standards. The production companies included DreamWorks SKG Television (Spielberg’s company), Playtone (Hanks and Goetzman’s company), and HBO. The estimated cost of the miniseries came in at $120 million, which rivals any mainstream movie currently produced.6 As with Band of Brothers, several directors were tasked with specific episodes. The directors for The Pacific included a mix of American and Canadian perspectives: Tim Van Patten, David Nutter, Jeremy Podeswa, Graham Yost, Carl Franklin, and Tony To.7 Unlike the original book written by Stephen E. Ambrose for the miniseries Band of Brothers, The Pacific miniseries was based on several sources as well as the companion book, The Pacific: Hell Was an Ocean Away, by Hugh Ambrose.8 These books were quite divergent in their attitudes toward the war. Marine Private Robert Leckie’s Helmet for My Pillow covered the early part of the war; Private Eugene B. Sledge’s memoir, With the Old Breed at Peleliu and Okinawa, covered the later part of the fighting between 1944 and 1945; and Private First Class Charles W. “Chuck” Tatum’s Red Blood, Black Sand focused on the fighting of the Marines on Iwo Jima where John Basilone was killed.9 Another manuscript that became linked to the series was Sidney Phillip’s memoirs, You’ll Be Sor-ree!: A Guadalcanal Marine Remembers the Pacific War. Phillips was recognized as the connecting character that linked the main characters in the television miniseries during the three years the show encompasses.10 To coincide with the miniseries, Sergeant Romus V. Burgin, who was featured in the later episodes of the series, published his memoirs, Islands of the Damned, to build further off of first-person accounts of the battles on Peleliu and Okinawa. Burgin served as the squad leader for Sledge’s mortar team.11

The companion piece—The Pacific—was written by Hugh Ambrose, Stephen’s son. While the last book was meant to be an additional work to supplement the television show, it was often compared to, and misinterpreted as, the book upon which the series was based.12 As opposed to the companion book, the former titles by Marines were all memoirs of combat rather than a strategic overview of the Pacific theatre of war. While showing the reality of combat on the Marines, the series also looked at the racism prevalent at the time of the war and how demonizing the enemy was commonplace.

Given that the series was produced by HBO, the producers were able to budget effects and writers to make a high-budget series in a short, primetime format, and given the fact that HBO relies on subscriptions, increasing interest in the series meant they had to craft a final product that would retain audiences. To attain even more interest for residuals, the producers relied on what Jonathan Grey referred to as overflow; or in this case, the additional materials such as maps, statistics, personal stories, and stock footage needed to keep viewers interested in the story. However, excess information, be it in books or other media, can be vexing to story continuity, as well as viewer comprehension. This confusion seemed to occur at least occasionally for viewers of the show.13 The creation of the series also renewed criticisms that Hollywood dramatizes the actions of the stereotypical hero—white, middle class, male—while ignoring the actions of anyone not of that type.14 The Marines did experience breakdowns, suffer debilitating maladies, and broke the Hollywood ideal of the soldier, appearing more like combatants with a lack of basic supplies.15

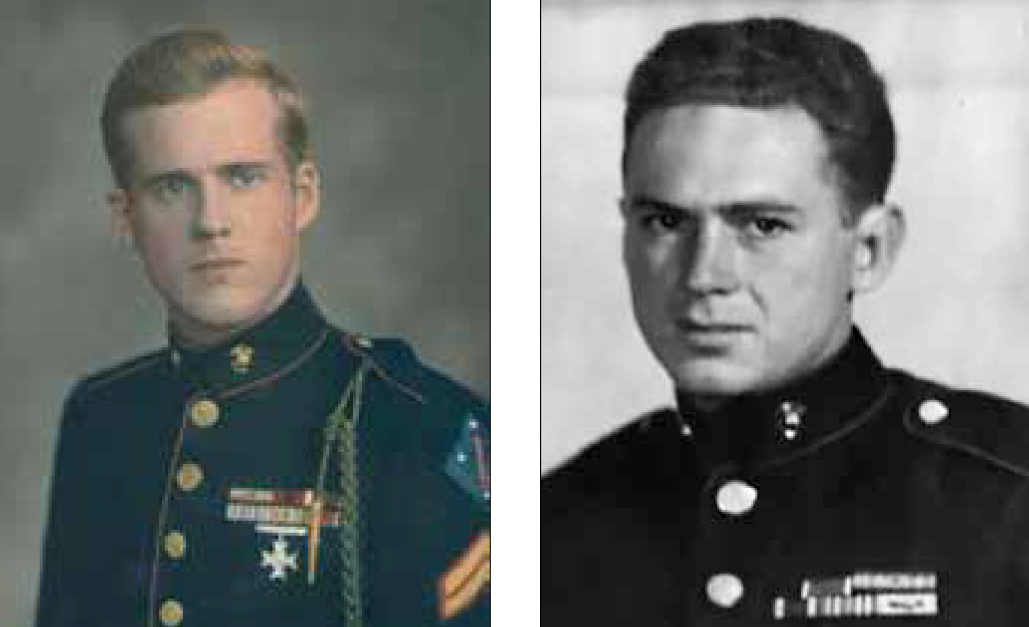

Pvt Eugene B. Sledge (left) and Pvt Robert Leckie (right) wrote of their time in the Marine Corps, contributing to the public perception of the war. Official U.S. Marine Corps photos

The series also was criticized for the brutal acts of desecration to enemy troops by Marines. While viewers see this as shocking and un-American, saying as much on various comment boards on HBO, the reality was noted in several sources, particularly Sledge’s memoir. Racism permeated many aspects of the war in the Pacific, as John W. Dower noted in War without Mercy, and the producers reiterated this aspect of the conflict in the extra features found on disc 6 of the box set.16 This aspect of warfare made the series difficult for some Americans to watch, while others considered it an appropriate homage to those who fought.

American Attitudes toward the Pacific War

One of the most significant aspects of memory and remembrance of World War II is the difference between the two main theaters of war. While the Nazi menace was considered more dangerous and was given top priority by the Franklin D. Roosevelt administration, the war with the Japanese Empire was far more brutal; its brutality could not always be understood by Americans who had not served in the military, let alone in combat. Race, among other factors, played a significant role in that confusion. The Germans had an appearance that made them “like us,” or at least like white Americans. Some Americans came from a generation or two removed from Germany, so there was a connection to the old country. While the Nazis might be despicable, the Germans conducted warfare with a semblance of rules as they fought the Western Allies, while conducting a brutal war without limits against the Soviets.17

.

.

Frontline warning sign using a Japanese soldier's skull. National Archives

The Japanese, however, were depicted by the U.S. government and the popular American media as barbarians from the outset of the war.18 During the 1937 Nanjing Massacre, the Japanese Imperial Army brutalized the population of Nanjing, China, and behaved brutally toward anyone who did not fight in the ways of a warrior, or Bushido, believing them not worthy of honorable treatment. The Allied troops who surrendered to the Japanese during the war were not offered any honor. Because the war in the Pacific was so markedly different from that of Europe, viewers who watched The Pacific were shocked to see U.S. Marines committing acts of violence that might now be seen as ghoulish or uncivilized, such as taking gold teeth from dead Japanese soldiers or the use of skulls to decorate American camps.19 Taking war souvenirs, and to a lesser extent the desecration of bodies, occurred on both sides during the war, as was mentioned in books from the fighting in the Pacific during World War II.

This behavior was not easily accepted by the average American viewer, who looked—and still looks— upon American servicemen as always doing the right thing. WWII veterans seem to be held to a higher standard than current troops by many in the media or in society, as they are part of the “good war” as described by author Studs Terkel, in which the enemies of America were readily identified.20 Neither of these opinions is necessarily right or wrong. However, it must be acknowledged that combat is brutal and atrocities are common, but not always presented realistically in film or television. Racism occurred throughout the United States during the war, and combined with the perceptions about Japanese-Americans interned for their perceived loyalties to Japan, attitudes toward the enemy were strong, stereotypical, and often wrong.

Viewers who watched The Pacific expected the series to be a counterpart to Band of Brothers, which in some ways it was. However, the series had some distinct differences. The extremes of jungle fighting made attrition common and many Marines left the theater of combat after a time, so there was no unit cohesion. The 1st Marine Division was the focal point of The Pacific, which eliminated a considerable number of the battles in the Pacific, such as Tarawa, Saipan, Tinian, and New Guinea. More importantly, the series did not show the contributions of the U.S. Army, Air Corps, Navy, or Coast Guard to any extent.

Creation of The Pacific Miniseries from Historical Documentaries

The origins of The Pacific miniseries go back to two specific television series from the 1950s. Crusade in the Pacific, a 24-part series, was done in the typical documentary fashion of the era, and covered all U.S. Services in the theater. Using newsreel footage, as well as maps, the narrator explains the specific battle or timeframe for the episode and how it influenced the overall war. Crusade in the Pacific focuses on strategic issues: troop movement, battle plans, fighting conditions, and the strategic outcome of the battle. The use of the maps in this original series influenced and inspired the producers of The Pacific, even to the point of using an Imperial Japanese battle flag to illustrate the areas of control. The other direct aspect was the diagram that showed the tunnel system on Peleliu from the episode titled “Palau,” and how that was used by the producers of The Pacific to guide a direct scene-by-scene shot in the historical section for episode 6 on the Peleliu hills titled “Peleliu Airfield.”21

The other influence for the series came from Victory at Sea, a 26-part documentary series meant to show how extensively the U.S. armed forces worked to confront enemies during World War II and how that collaboration allowed the Allied forces to defeat the Axis nations. However, Victory at Sea was produced more like propaganda, similar to Frank Capra’s Why We Fight. Its top-down history did not deal with the memories of the average foot soldier or the minutiae of the battles.22

Even more telling was that the viewers expected The Pacific miniseries to be historically accurate, more akin to a documentary than an entertainment or information-based video series. The factual basis was important, but many viewers expected the stories to follow history exactly, which they did not for a variety of reasons. For example, in episode 9, “Okinawa,” the action begins in May 1945, when the 1st Marine Division had already cleared the northern part of the island, but with minimal contact with the enemy as opposed to the vicious fighting farther south. The episode opens with the division shifting to the south to replace the U.S. Army units who were being taken offline, and the 1st Marine Division being put into ever- more-brutal fighting near the Shuri line.23 At times in the episode, it seems clear that certain events were merged to create a better flow for the story line, and several actions were attributed to the different characters in the show. The most apparent issue in regard to compressing time came in the last episode, “Home,” when Private Sledge has seemingly gone from Okinawa to the United States. In fact, he and his unit were sent to China for a year. This pertinent fact was overlooked for the miniseries.

The last disc of the series offers additional historical background and insight into what the directors and producers were trying to achieve. Director Tim Van Patten notes that they did a significant amount of historical research to find the proper look for the actors and the shots of the battles. The directors were quite aware that there would be some historical comparisons taking place, especially by those who were there. As with any television series, even documentaries, viewers will constantly critique what is included, excluded, and how it is edited. No matter what is presented, there will still be some human predilection toward events and historical presentation, be it their own biases, previous understanding of material, or personal recollections from friends or family.24

The Pacific: The Series,the “Fixes,” and Its Reception

At the time of the release of the miniseries, Hugh Ambrose published the official companion piece, The Pacific. Ambrose wrote in the introduction that this book had been initially meant as a joint project between him and his father, historian Stephen Ambrose, who died in 2002. Later, the book was continued, but the pressure to finish the project, its massive scope, and the deadlines for additional marketing made any mistakes that much more noticeable. Ambrose made two key points in the book: first, it was not meant to be a complete overview, since there were so many stories that could not be told in the book; second, it was not meant to serve as a follow-along book, such as Band of Brothers or Generation Kill, another HBO combat miniseries based on the experiences of Marines during the first 40 days of the war in Iraq.25 While both series followed their respective books well, The Pacific book was meant to tell augmented stories to tie it all together. The book focused on some of the characters from the series—Sid Phillips represents the key link, and his You’ll Be Sorree! had not yet been widely distributed—but primarily focused on two officers: Navy pilot Captain Vernon L. Micheel and Marine Lieutenant Austin C. Shofner.

The speculation from many viewers was that, if the officers had been more significantly noted in the series, the show might have had greater impact with them. Understandably, the story of Shofner was compelling: stationed in the Philippines at the start of the war, a prisoner of war for a year, and then a guerrilla fighter for six months more. Shofner was in charge of 3d Battalion, 5th Marines, in which Eugene Sledge fought during Peleliu. Shofner then went back to the Philippines, and later on to Okinawa. Shofner’s combat record might have complemented the series well. The concept of the series, however, was to focus the story lines on the fighting man instead of the operational history that is more common in military histories.

In all, the book remains a considerable attempt to concentrate the myriad stories into one cohesive format, as well as fill in what seemed to be gaps left by the miniseries. This idea of telling individual stories rather than the big picture of the overall timeline of the war, or of the generals and admirals who make the strategic decisions, has become more prominent in recent years. Unlike Victory at Sea, the voices of the individual Marine, soldier, and sailor were heard in The Pacific, but in a more condensed role. Ambrose’s book left a considerable void to fill. Many felt that Hugh Ambrose was not the historian or storyteller that his father was, while others believed the book was done slapdash and edited poorly, such as the mislabeling of the Battle of Midway, which led to problems of credibility. However, the book, when taken in context of the series, did what it was supposed to do: tie in the stories presented in the miniseries to those of both Navy and Marine Corps officers who saw a different part of the war, and leave the strategic role to other more academic tomes.

The show’s predecessor, Band of Brothers, was similarly refuted by some historians who felt that the senior Ambrose had been sloppy in his work. Some of the characters in that series who died were later noted as alive (e.g., Army Private Albert Blithe). Again, the line between documentary versus historical drama was blurred.26 In this age of instant access and sweeping television offerings, the two concepts are often fuzzy and occasionally to the detriment of both the producer and the viewer.

Sex, Violence, and Audience Reception

Complaints about the series were often vented on HBO message boards as well as other sites. The mixed reactions stem from several issues. First, The Pacific was compiled from three different memoirs, as noted earlier. Second, the series was told from the point of view of a larger body of Marine combatants. For Band of Brothers, the series focused on a company of paratroopers from the 101st Airborne of approximately 230 soldiers, depending on units, and their replacements. The viewer watched how they trained, fought, and depended on each other throughout the war in Europe. Again, this was an entirely different aspect of the perception of the theaters of war. For the European theater, men were kept in the same unit for the duration unless wounded. Americans at home following the war in the newspapers could easily find locations in Europe noted in the articles.

For The Pacific, as with the actual campaign of WWII, the islands were often unknown, hard to locate on maps, and the maps did not show the terrain and weather conditions American combatants fought against. The Pacific series dealt with enlisted men—not readily identified officers such as Band of Brothers’ Major Richard Winters, Captain Lewis Nixon, or Captain Ronald Spears—from the 1st Marine Division, which had a nominal strength of 16,000 Marines. Because the three main characters in The Pacific came from different regiments (4,000 servicemen in average regiment), there is far less continuity. Considering the physically and geographically diverse areas, intense battles, and lack of unit cohesion, the writers worked admirably to find commonalities; and the writers and producers did try to give an overview as well as an intimate look at small unit warfare in the Pacific theater. The link must be then-Private Sidney Phillips from Company H, 2d Battalion, 1st Marines, who served with Private Robert Leckie at Guadalcanal and Cape Gloucester and was friends with Private Eugene Sledge from Company K, 3d Battalion, 5th Marines, who fought later in the same division but at Peleliu and Okinawa. Complaints on the message boards came from different perspectives as well. In addition to the criticisms about not understanding characters, other viewers complained about the pacing, expecting the constant action found in Band of Brothers, or the difficulty of watching the night battle sequences. Given the terrain and conditions, it would have been less likely to see a lot of “typical war movie” battle sequences in urban or farm areas, where the enemy could be easily seen (or filmed for that matter) and engaged.

A more specific complaint generated by the series involved gratuitous sex, and to a lesser extent, gratuitously brutal violence. If one reads any Marine memoir, the desire for sex when not in combat is noted extensively. Leckie made considerable mention of this in his biography Helmet for My Pillow, when the Marines were in Australia, as did Phillips in his memoirs. The idea of Americans being squeamish about sex, while violence is perfectly acceptable, has also been discussed at length in psychology books as a variation of sublimation.27 The Marines considered the issue of sex to be of such significance that a segment on the necessity of condom usage was part of a restricted comic book published by the Marines Corps entitled Tokyo Straight Ahead. The desire for sex, especially young men who were virile and in harm’s way, drove many.28 The idea that a revered generation would consider thoughts attributed to a more modern generation is sometimes difficult for viewers to accept.

The series was derided for these depictions of sex, especially in episodes “Melbourne” and “Basilone.”29 The reality of the time was that Western women were not accessible to troops in the Pacific theater. There was the possibility of fraternization with local women in Europe, but any female U.S. personnel stationed in Europe during the war were under constant guard against the threat of sexual assault from male personnel. Historian Peter Schrijvers described the conditions on one particular island, where the women’s quarters were surrounded by concertina wire; and further, even when out on dates, their male escorts carried a sidearm.30 In the series, Gene Sledge made two comments on women in this regard: they did not need to be nor should they be in a combat zone. Note that one of these comments ostensibly occurred after alighting from a ship back to Pavuvu, Solomon Islands, in October 1944, and the other occurred when he was chatting with his brother about the lack of women and sex in the Pacific in which he concurred with the U.S. Army on their synopsis of the Pacific War.31 The concept of sex and romance is further clouded when one considers the idea of sex and military personnel. In Band of Brothers, a sex scene was included, but it was not necessary for character development. In The Pacific, the sex was part of a wider pattern showing emotional connection, both with the characters and their fears and desires as citizen soldiers, as well as combatants who wished to feel some sort of emotional connection to something other than killing and violence. While the inclusion made the episodes seem slow, the need for sex has been duly noted in several of the primary sources. For example, Leckie became more interested in what he referred to as “the chase” for willing female partners, rather than romance as was depicted in the series.32

Concerns about the desecration of enemy bodies and the shooting of civilians also came across in the message boards. Viewers were disturbed by a scene in which a Marine idly dropped rocks into the skull pan of a Japanese soldier, while another noted that it was gratuitous and unrealistic for Marines to pry out gold teeth from Japanese soldiers.33 The events in question were taken directly from Sledge’s book and have been noted in several other sources, including Schrijvers, Leckie, Dower, and Stephen Ambrose.34 Even in Band of Brothers, a certain amount of souvenir taking among American soldiers took place. The idea of a morality in war, from Thermopylae to now, is a myth. For today’s servicemembers, the episodes contained elements that seemed familiar to modern combat operations in Iraq and Afghanistan. In one scene in the episode during the Okinawa campaign, the Japanese use civilians as human shields and draw on American compassion. A woman tries to hand off her child to a Marine. When her jacket opens, the viewer sees she has explosives strapped to her chest, which detonates, killing or wounding all around her. The Marines later commented on the barbaric nature of their enemy to use such horrific tactics.35 This type of combat tactic was common in Iraq and Afghanistan, where jihadists disguised as civilians walked into U.S. lines and detonated explosives. Whether they were lured, coerced, or did so voluntarily is a matter of opinion, but the results were the same. The scenario of civilians and combatants dying on the battlefield took viewers away from the Hollywood version of a “clean war” and gave people the uncomfortable perspective of seeing civilians die as they either were in the way or served a purpose against a determined enemy.

Combat, Racism, and Time Compression

Viewers of The Pacific also complained that the battles were often difficult to follow by the lay audience. During the first two episodes, which dealt with the battle on Guadalcanal, viewers were not given proper cues to determine what major battle they were watching. Some depictions, such as the location of Alligator Creek, were noted but not consistent; when combined with an incoherent battle sequence or the lack of location, the significance of the battle was often undercut. The book offered the viewers a way to connect the events but did not succeed, as the battles were not necessarily noted for their significance.

When one hears of veterans and the treatment of enemy soldiers in what might be considered war crimes, WWII is not invoked but Vietnam typically is. Racism was a powerful force during WWII, and when combined with the stereotypes of the Japanese (and the Japanese stereotypes of Americans), the war in the Pacific introduced depictions of the Japanese as having buckteeth, Coke-bottle glasses, and a cartoonish demeanor. The series, however, would often counter this reality. For example, one episode depicts Tatum and members of Company C, 1st Battalion, 5th Marines, commenting on their desire to “slap a Jap.” Gunny Sergeant Basilone confronts them, saying that whatever the men’s opinion based on Hollywood or pop culture depictions of Japanese soldiers, the real Japanese soldier deserved respect as a crafty, battle-tested soldier who was willing to die for his emperor. The Marines were told to never underestimate the enemy, nor should they be given a break; but it was also not going to be an easy battle against a caricature enemy. Tatum notes in his book that Basilone, in fact, did not utter this speech, but another sergeant did.36

Comic strips at the time featured the story of GySgt John Basilone that also was used in the series The Pacific. Dell Comics publication War Heroes issue no. 6, October–December 1943

Another criticism made by viewers, as well as those who served in support units from World War II, is that many units or groups are ignored in the story lines or that the cast is not diverse enough. Both issues are important to note, given that the U.S. Armed Services were segregated at the time. While there were important contributions by servicemen of color, the stories most often told are of the units that saw extensive combat; and the majority of those units in the segregated U.S. military of World War II were in fact white. Spike Lee further argued this point when Flags of Our Fathers came out, noting the fact that 900 African Americans fought during the conflict but were not depicted in the movie.37 Since the film centered on the men who raised the flag, including everyone was not realistic, but then neither would the inclusion of specific ships, aircraft, or Army units. Hollywood still needs to sell the most appealing story, and this is why even Spielberg would be hard-pressed to make a movie that centered on his father’s service in the military, flying “the Hump” with the China-India-Burma units of the U.S. Air Corps. They did serve a vital part of the war, but it was not glamorous.

This preconceived notion that all who served in World War II were combat veterans has also been reevaluated. Many Service personnel did not serve in combat units, but were instead in some form of support. They did not see combat, but were just as responsible for the war effort by making the machinery run, arming and repairing weaponry, and keeping combatants fed. These stories, while important, often do not excite Hollywood moviemakers, nor do they resonate with viewers. So, in this regard, the films still convey what both the creators and viewers want— action. The reality is often different, and the criticisms perhaps unwarranted.

The Concept of PTSD

One of the most mistaken aspects of World War II in commemoration is that of post-traumatic stress and how it affected the combatants. Movies and documentaries from the World War II era or early Cold War often avoided such issues or illustrated them in limited form. Both Band of Brothers and The Pacific took the concept of post-traumatic stress and visually demonstrated events that may have contributed to the malady.

In Band of Brothers, there were issues of combat stress or some sort of mental break, especially during episode 6, “Bastogne,” but on the whole there were far more cases of combat fatigue in the Pacific theatre, specifically the southwest Pacific where most of the island fighting took place.38 Whether it was Sergeant Basilone’s lamentation for his friend Sergeant Manny Rodriguez who was killed or the guilt of not returning to fight, his emotional distress has similarly been echoed by current recipients of the Medal of Honor. Leckie suffered combat fatigue, which led to his hospitalization on Banika, near Pavuvu. In episode 4 of The Pacific, Leckie notes his breakdown in detail. He also mentions in the book and the series a fellow Marine who strangled a Japanese soldier with his bare hands and later broke down.39 Some viewers commented that Leckie was a coward for his constant disobedience to the chain of command and orders (something he readily admitted in the book), but again this was part of a wider perception of WWII veterans—that they did not suffer from mental issues—more typically seen as a Vietnam War malady. Ironically, both wars had similar situations and combat conditions, and so it is just as likely to have happened. The image of the “good war” where enemies are clearly defined and goals marked (e.g., the unconditional surrender of an enemy) is that such incidents are more of a modern creation, and not as simple as first conceived. Despite what some may see as modern weakness, other historians such as Lawrence Tritle, have noted that aspects of PTSD go back as far as ancient Greece.40

The stress of Marines seeing civilian casualties also was explored in episode 9, “Okinawa,” where the native Okinawans were used as human shields by the Japanese against U.S. movements. Civilian losses often made coping even more difficult. Seeing a female Okinawan with a bomb strapped to her must have had some sort of impact on veterans of Iraq and Afghanistan, where suicide bombers are common.

The impact of nightmares and post-traumatic stress was also noted by Sledge. And while the last episode dealt with his reacclimatization to the United States, the reality was that he did not come back to the states until almost 1947, after an additional tour in China. He still had recurring nightmares of the war, which he mentions in the book. One viewer of the series said that he “hated Sledge’s emo character,” as if this were an effect created by the actor or the director. Again, the events that caused him trauma in the film were noted in detail in his book.41

What is also prevalent in the series, as in many wartime memoirs, is gallows humor. The need for lightheartedness to break the tension was a key part of the series. For example, the scene where a Marine is chased from a cave after trying to defecate led to his near demise. The Japanese soldier is killed, but the others make fun of the Marine (who did in fact soil his pants) by saying he looked like he had won a sack race.42

Supplemental Information

One of the modern aspects of The Pacific, as compared to Victory at Sea or Crusade in the Pacific, is that the modern series offers supplemental online information through HBO’s website. One section displays the battle map, which offers interactive views of the major battles shown by specific episode. The maps are detailed and show specific battles and layouts of units during the fight, where certain characters were located during the attacks, as well as animated aspects of aerial attacks and ship movements.

The second section, “Interact with History,” allows the viewer to read more about the facts that no series, regardless of how extensively done, could ever cover. For example, in the first episode, a Marine lieutenant is shown with an M50 Riesling submachine gun. Many of these weapons proved to be inadequate in the jungle, but the producers made it a point of historical accuracy to show these weapons along with the M1903 Springfield rifles instead of the M1 Garand rifles, which were used by the U.S. Army by that time. The Victory at Sea episode on Guadalcanal did not use accurate footage of the battle and often Marines are shown with the Garand rifles.

The final section, “Witness the Conflict,” gives access to subscribers to watch the episodes. The interactive features of the website, combined with the comment boards, the historical markers and maps, and the various stories of tribute to those who fought in the Pacific theater made, and continue to make, for a collaborative process that allows the series to morph and change with time. In testament to the efforts made, The Pacific was awarded two Emmys for the series, whereas Band of Brothers won seven, and comments on the internet, as well as the sales of the series, continue to this day.

Conclusions

While the series The Pacific had its detractors, it did garner considerable viewership for HBO, as well as greater recognition for the Marines who later wrote of the exploits of their units. And as with any series, especially one done primarily for entertainment purposes, and one based on memoirs as source material, the flow of scenery and historical alteration often made fodder for critique. For many viewers, Band of Brothers serves as a benchmark for this type of miniseries on several levels. One reason for this is the familiarity of the battles and the idea of the “good war”: one in which the combatants know what they are fighting for and are fighting within the seeming grounds of respect for their enemy as fellow humans. For Marine Corps veterans of the Pacific campaigns, the war could not have been any more different from that taking place in Europe. In a scene from the last episode, “Home,” Sledge discusses his war versus that of his older brother Ed, who fought with the U.S. Army in Europe. When it was revealed in the film that Eugene Sledge did not have the opportunity to fraternize with women or enjoy any of the other aspects of life in the European theater, his brother responded with a look of both shock and sadness.43 The idea of the war in the Pacific not being familiar—geographically, climatologically, culturally, or militarily—with any preconceived expectations, or for that matter too many expectations, as Eugene had mentioned prior to his first battle, came as a surprise.44

For viewers of The Pacific, the disappointment of expectations was varied, understandable to an extent, but their complaints were not entirely accurate. Commenters on the board noted that one should watch the series a couple of times; and it becomes much stronger when the books, the supplemental information, and the series all coincide. At the same time, whenever HBO or some other large production company authorizes a series to visually tell the story of a unit from World War II, the other Services want their due, be they the Navy, the Seabees, or the Army paratroopers in the Philippines.

Preservation of history is critical, and documentaries and even historical dramas serve a role, but it must be augmented by other sources to take in the events so that one can determine what is real and what appears contrived by Hollywood. The combat memoirs from Leckie, Sledge, Phillips, and Tatum serve that purpose and were transferred, at least superficially, to the visual medium. However, in today’s instant world, we focus more on the here and now and what fits in our collective ideas of what history should be. Anything else is a disappointment.

•1775•

Endnotes

- Cord Scott holds a PhD in American history from Loyola University, Chicago. He has taught on a variety of aspects concerning American culture. He is currently a history instructor for University of Maryland, University College-Asia in the greater Tokyo area. His previous assignments for UMUC have been on Okinawa and in South Korea.

- A reporter concludes that this is how a teacher of history would teach a student body, based on Salomon’s comments on his series Victory at Sea, which served as a model for the later television miniseries The Pacific. Gary R. Edgerton and Peter C. Rollins, eds., Television Histories: Shaping Collective Memory in the Media Age (Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 2001), 107.

- Robert A. Rosenstone, History on Film, Film on History (London: Longman, 2006).

- Band of Brothers, produced by Steven Spielberg and Tom Hanks, various directors (New York: HBO, Time Warner, 2001), cable miniseries; and The Pacific, produced by Steven Spielberg, Tom Hanks, and Gary Goetzman (New York: HBO, Time Warner, 2010), cable miniseries.

- Sands of Iwo Jima, produced by Edmund Grainger, directed by Allan Dwan, starring John Wayne (Los Angeles: Republic Pictures, 1949), feature film, 100 minutes.

- Alex Ben Block, “How HBO Spent $200 Million on ‘The Pacific’,” Hollywood Reporter, 26 August 2010.

- The Pacific; Van Patten directed episodes 3, 8, and 10; Nutter directed episodes 2 and 8; Podeswa directed episodes 3, 8, and 10; Yost directed episode 4; Franklin directed episode 5; and To directed episode 6.

- Stephen E. Ambrose, Band of Brothers: E Company, 506th Regiment, 101st Airborne from Normandy to Hitler’s Eagle’s Nest (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1992).

- Robert Leckie, Helmet for My Pillow: From Parris Island to the Pacific (New York: Bantam, 1957); E. B. Sledge, With the Old Breed at Peleliu and Okinawa (Novato, CA: Presidio Press, 1981); and Chuck Tatum, Red Blood, Black Sand: Fighting Alongside John Basi- lone from Boot Camp to Iwo Jima (New York: Berkley, 2012).

- Sid Phillips, You’ll Be Sor-ree!: A Guadalcanal Marine Remembers the Pacific War (New York: Berkley, 2010), ii.

- R. V. Burgin with Bill Marvel, Islands of the Damned: A Marine at War in the Pacific (New York: NAL Caliber, 2010).

- Hugh Ambrose, The Pacific: Hell Was an Ocean Away (New York: NAL Caliber, 2010).

- Jonathan Gray, Television Entertainment (New York: Routledge, 2008), 89–92.

- Larry May, “Making the American Consensus: The Narrative of Conversion and Subversion in World War II Films,” in The War in American Culture: Society and Consciousness during World War II, ed. Lewis A. Erenberg and Susan E. Hirsch (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1996), 76.

- Susan Jeffords, Hard Bodies: Hollywood Masculinity in the Reagan Era (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1994), 176.

- The Pacific, disc 6, “Anatomy of the Pacific War,” 2011.

- John Keegan, The Second World War (New York: Viking Penguin, 1990), 175.

- John W. Dower, War without Mercy: Race and Power in the Pacific War (New York: Pantheon Books, 1986), 8.

- See, for example, the Japanese skull and the sign reminding U.S. Marines to take their Atribine to counter malaria in the series, which was based on actual pictures. Another showed an image of a Japanese skull as decoration. Ben Cosgrove, “Portrait from the Brutal Pacific: ‘Skull on a Tank,’ Guadalcanal, 1942,” Time, 19 February 2014; and Kaite Serena, “Skulls, Ears, Noses, and Other Morbid ‘Trophies’ Americans Took from Dead Japanese in WWII,” All that Is Interesting (blog), 13 November 2017.

- Studs Terkel, “The Good War”: An Oral History of World War Two (New York: Pantheon Books, 1984).

- Crusade in the Pacific, episode 7, “Guadalcanal: America’s First Offensive”; episode 17, “Palau: The Fight for Bloody Nose Ridge”; and episode 25, “At Japan’s Doorstep: Okinawa,” directed by Arthur B. Tourtellot, written by Fred Feldkamp (New York: Time, 1951). See also the historical notes to The Pacific, episode 6, “Peleliu Airfield.”

- Victory at Sea, directed by M. Clay Adams (New York: NBC, 1952–53); and Why We Fight: A Prelude to War, directed by Frank Capra (Washington, DC: U.S. Department of War, 1942).

- The Shuri line was the main line of Japanese resistance running from coast to coast across Okinawa and roughly in line with Shuri castle.

- The author served as a historical consultant for Inside World War II, produced by Jonathan Towers, aired 12 August 2012, National Geographic. One of the complaints made by viewers was that the colors were wrong for the Nazi aircraft, and that the series did not delve deep enough into the events. The producers explained to the author during review that the series was intended for younger audiences that may not be aware of the human element of the war, and that it was a starting point for further discussion.

- Generation Kill, directed by Susanna White and Simon Cellan Jones (New York: HBO, 2008). The series covers the activities of a Rolling Stone reporter who is embedded with 1st Reconnaissance Marines during the first wave of the American-led assault on Baghdad in 2003. It is based on the book by Evan Wright, Generation Kill: Devil Dogs, Iceman, Captain America, and the New Face of American War (New York: Penguin, 2005).

- In this regard, a documentary is as factual as possible, while the historical drama, though based on the facts of the event, often includes fictionalized characters or merged events. This is done more for the purpose of storytelling rather than accuracy.

- Leckie, Helmet for My Pillow, 116; Phillips, You’ll Be Sor-ree!, 120; and Steven Mintz, Randy W. Roberts, and David Welky, eds., Hollywood’s America: Understanding History through Film (Oxford: Wiley, 2016), 83.

- “Don’t Take a Fling, if You Ain’t Got that Thing,” in Tokyo Straight Ahead: Guam, Peleliu, Saipan, Tarawa, and Guadalcanal (Camp Pendleton, CA: Reproduction Section, Camp Pendleton, 1945).

- The Pacific, episode 3, “Melbourne,” directed by Jeremy Podeswa, aired 28 March 2010, HBO; and The Pacific, episode 2, “Basilone,” directed by David Nutter, aired 21 March 2010, HBO.

- Peter Schrijvers, GI War against Japan: American Soldiers in Asia and the Pacific during World War II (New York: New York University Press, 2002), 150.

- The Pacific, episode 10, “Home,” directed by Jeremy Podeswa, aired 16 May 2010, HBO; Emily Yellin, Our Mothers’ War: American Women at Home and at the Front during World War II (New York:Free Press, 2004), 128; and Mattie E. Treadwell, The Women’s Army Corps, U.S. Army in World War II, Special Studies (Washington, DC: Center of Military History, 1991), 425–26, 450. Note that, in a 1939 Army staff study addressing the probability of women serving in the Army, a male officer stated: “Women’s probable jobs would include those of hostess, librarians, canteen clerks, cooks and waitresses, chauffeurs, messengers, and strolling minstrels.” The report failed to discuss the highly skilled office jobs that most of the women held, because many doubted women were capable of handling jobs of any significant responsibility.

- Leckie, Helmet for my Pillow, 149.

- The Pacific, episode 7, “Peleliu Airfield.”

- Schrijvers, GI War against Japan, 209–10; Leckie, Helmet for My Pillow, 116–17; Dower, War without Mercy, 61–66; and Ambrose, Band of Brothers, 260–61.

- The Pacific, episode 9, “Okinawa,” directed by Timothy Van Patten, aired 9 May 2010, HBO.

- Tatum, Red Blood, Black Sand, 86–87.

- Alex Altman, “Were African-Americans at Iwo Jima?,” Time, 9 June 2008.

- Schrijvers, The GI War against Japan, 197.

- The Pacific, episode 4, “Gloucester/Pavuvu/Banika,” directed by Graham Yost, aired 4 April 2010, HBO; and Leckie, Helmet for My Pillow, 266.

- Lawrence A. Tritle, From Melos to My Lai: War and Survival (London: Routledge, 2000).

- “A Review of HBO’s ‘The Pacific’,” On Violence (blog), accessed 1 December 2017.

- The Pacific, episode 9, “Okinawa.”

- E. B. Sledge, China Marine (Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 2002), 124–29.

- Sledge, With the Old Breed, 55–59.