The uniforms for Reserve female Marines were designed by the Marine Corps Quartermaster’s Office and tailored for each woman from material similar to the men’s uniforms. The issued items, described in the May 1936 article by former Corporal Lillian C. O’Malley, included “a specially designed skirt and coat, overcoat, chambray shirt, regulation tie, overseas cap, and campaign hat. The overseas cap, both in winter field and khaki, was the preferred head gear and the one usually worn by all women in uniform.”5 Initially, each female reservist was issued one green wool jacket and skirt for the coming winter. The standard issue later became two winter and three summer khaki uniforms. The uniform issue consisted of jackets and skirts, six shirts, one overcoat, two neckties, and a pair of brown high-topped shoes for winter wear and low-cut oxfords for the summer khaki uniform. There was no dress uniform, and raincoats, gloves, and purses were not issued. The Marine Corps emblem and appropriate chevrons were also issued. The female Marines were noted to be “very impressive with their ‘trim and snappy appearance’.”6

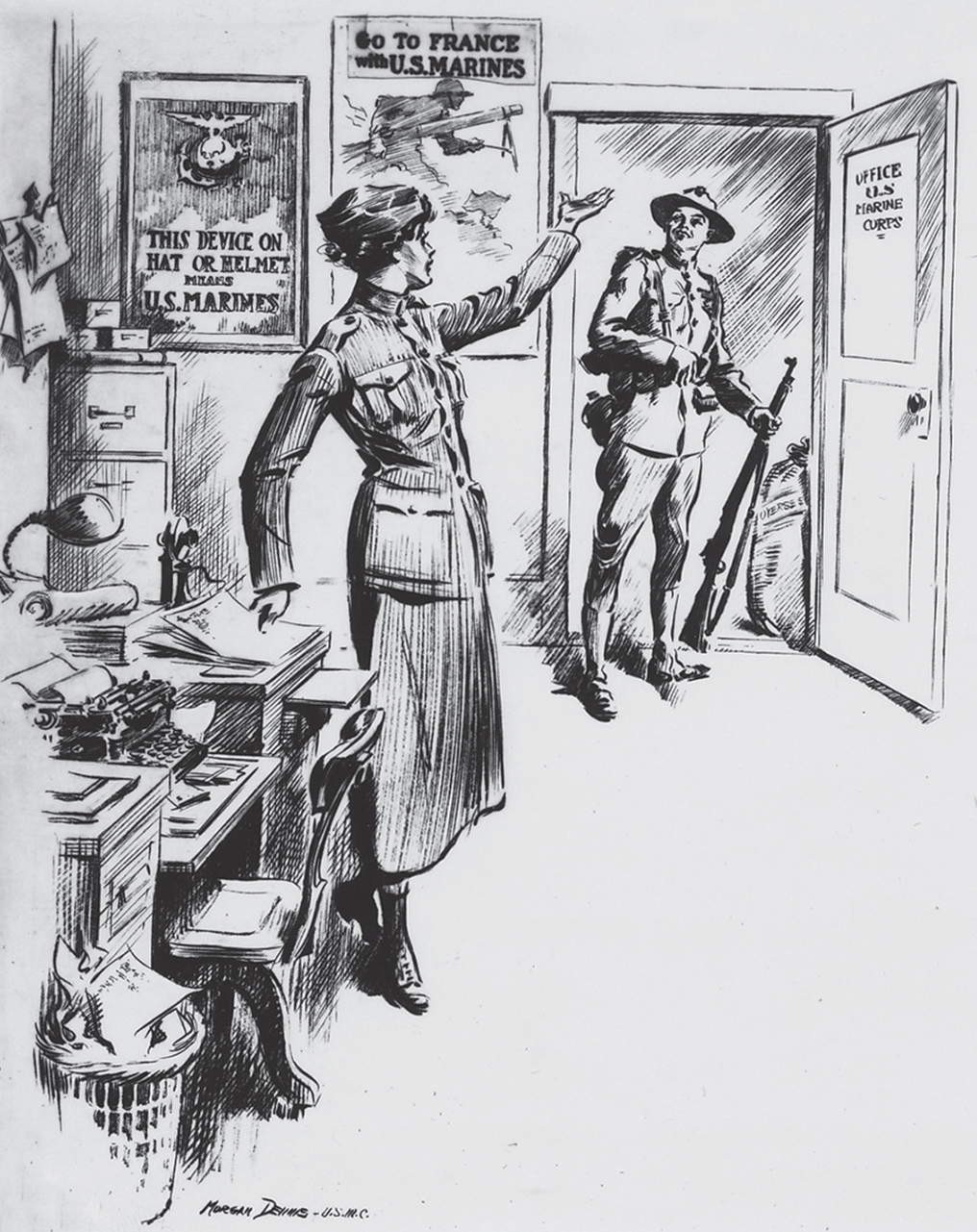

Marine Corps artist Morgan Dennis depicts a female Marine replacing a Marine clerk for duty in the operating forces. National Archives, Record Group 127G, photo 528855

There was no boot camp or recruit training for these new female Marines, who were called “Marinettes” in both civilian and War Department news releases and in photograph captions. However, officials at Headquarters Marine Corps disapproved of the nickname, as did many of the female reservists who preferred to be called simply “Marine.”7 Training for the female reservists consisted of clerical work and close order drill. The drill, conducted by experienced male Marine noncommissioned officers (NCOs), took place in Potomac Park on the White House Ellipse. The new Marines, under the tutelage of the demanding male NCOs, became sufficiently proficient to be included in numerous parades and ceremonies in Washington, DC.8 The Major General Commandant reviewed them on parade at the Ellipse on 3 February 1919, and the “entire unit was included in the guard of honor, facing the Presidential Reviewing Stand at the White House, for a parade of troops just returned from the front,” in early summer 1919.9

Women Reservists by the Numbers

Thousands of women stepped forward to be screened for enlistment in the Marine Corps Reserve in those first weeks after its authorization. In New York City, 2,000 women lined up at the recruiting office to be screened. After dictation and typing tests winnowed the line somewhat, interviews were conducted and only five were chosen.10

Faced with the challenge of all the enlisted women entering at the rank of private, some more mature women received early appointment to a higher rank. The September muster roll for Headquarters Marine Corps indicates that, on 11 September 1918, with just less than one month on active duty, Opha M. Johnson was appointed to sergeant, making her not only the first female reservist but the Corps’ first female NCO.11

Florence Gertler, one of the five applicants from New York City, was enrolled as a private on 3 September 1918 and assigned to Headquarters Marine Corps. She rose in rank quickly: promoted to private first class in November, corporal in February 1919, and sergeant in April 1919.12 Also promoted to sergeant in April 1919 were Violet Van Wagner and Florence M. Weidinger (enlisted 17 August 1918), Helen M. Mull (enlisted 29 August 1918), and Margaret L. Powers (enlisted 19 September 1918).13

Another female enrollee, Sophia J. Lammers, enlisted on 4 November 1918 and reported for active duty at Headquarters on 9 November 1918.14 She had the distinction of being immediately appointed to sergeant due to her qualifications: a 1911 University of Nebraska graduate, former reference librarian for the university, and a reference librarian at the Library of Congress when in the Marine Corps Reserve (F), listing source materials for a history of the Marine Corps. As such, this previous education, training, and work experience made her highly qualified to research and assist in writing Marine Corps history.15

Another female accepted for enlistment was Martha L. Wilchinski. In August 1918, the Marine Corps Recruiting Publicity Bureau in New York City enrolled Wilchinski as a private.16 With a degree in journalism from New York University, she was well prepared for service in the Publicity Bureau. During her active duty, several of her articles about service in the Corps were published in various newspapers and magazines, and she frequently appeared in publicity photographs. Wilchinski went on to become the editor of Variety magazine.17

Wilchinski rose to the rank of sergeant by July 1919 and was transferred to the Assistant Adjutant and Inspector Office, San Francisco, California, that month.18 There, Wilchinski was discharged from active duty, but remained as an Inactive Reserve until her enlistment obligation was completed in August 1922.19

Women applicants surged into the New York recruiting office when the announcement was made that the Marine Corps was enrolling qualified women for clerical work as members of the Marine Corps Reserve. National Archives, War Department photo 165-WW-598A-12

Another impressive female enlistee who attained the rank of sergeant outside of Headquarters was Lela E. Leibrand. She enlisted on 31 October 1918 at the recruiting station in New York City and began her service as a clerk in the Adjutant and Inspector Office on 8 November.20 Muster rolls show her on “Special Temporary Duty” with the Publicity Bureau in New York City, during 11–17 March 1919 and again in 17–21 May 1919.21 She then transferred to the Central Recruiting District, Kansas City, Missouri, on 25 May 1919.22 Leibrand continued on the inactive Reserve list until discharged at the rank of sergeant in December 1922.23

While assigned to the Marine Corps Publicity Bureau, Leibrand did routine office work but also produced articles published in the Recruiters’ Bulletin, Leatherneck newspaper (it later became Leatherneck magazine) and The Marines Magazine. She had been a Hollywood scriptwriter in 1916 prior to entering the Marine Corps. Her talents, honed in the burgeoning movie business prior to active duty, proved very useful for the Marines. Among her credits as a Marine is one of the first training films, “All in a Day’s Work.”24

While with the Publicity Bureau, Leibrand’s articles provided insight into life as a female reservist at Headquarters. Her article, “The Girl Marines,” tells of the Navy Department taking over the Vendome Hotel in downtown Washington to house the women away from the men. She describes drill, beginning early in the morning on the Ellipse behind the White House, with each female company having a Marine NCO in charge. She recorded the names of these early drill instructors for the female leathernecks: Sergeant Arthur G. Hamilton, Corporal Edward E. Lockout, Corporal Guy C. Williams, and Private Herbert S. Fitzgerald.25

Leibrand returned to the film industry after the war, first working at Fox Studios in New York City, but eventually making a name for herself and promoting her daughter’s career. Although married more than once, she was well known by the last name: Rogers. Her daughter, Ginger Rogers, gained fame in the movie and entertainment industry.26

Cpl Martha L. Wilchinski, assigned to the Recruiting Publicity Bureau in New York City, marches alongside USS Arizona (BB 39) seagoing Marines when the ship was anchored in the North River (south end of the Hudson River) in late 1918. Defense Department (Marine Corps) 518891

With assignments restricted to clerical-type duties, even with the expanding need for manpower, the numbers of Marine female reservists were small. By 1 September 1918, there were 31 women enlisted; as of 1 October there were 145; and by 1 November, there were 240 female reservists. In July 1919, when disenrollment from active duty began, there were 226 reservists.27 At its greatest strength, the Marine Corps Reserve (F) numbered only 305.28

While the numbers were few, the impact was significant. As early as mid-September 1918, the Major General Commandant was able to authorize the transfer of men “at Marine Corps Headquarters in staff offices, and in recruiting offices, employed on clerical or other routine duty and who were classified under selective service regulations, provided, of course, their service could be spared without detriment to the government service and the women clerks available were competent to fill their places.”29

With the majority of the female Reserve billets at Headquarters by January 1919, there were 88 female reservists assigned to the Adjutant and Inspector’s Office, 53 in the Quartermaster’s Office, and another 28 in the Paymaster’s Office.30

Marines participate in a 1919 parade in Philadelphia commemorating Marine Corps expeditionary service. Courtesy of former Capt Linda L. Hewitt Seagraves, USMCR

Release From Active Duty

On 11 November 1918, when the Armistice began, there were 277 women in the Marine Corps Reserve (F).31 With the war over, Sergeant Opha M. Johnson, the first female to enlist in the Marine Corps Reserve (F) and the Corps’ first female NCO, was discharged on 28 February 1919.32 She had etched her name solidly into Marine Corps history. However, the need for additional administrative support was not over. The clerical demands of bringing the Marines home, ensuring the accuracy of pay records, and accounting for the supplies while drawing down the force required the skills of the women reservists for several additional months. The Naval Appropriations Act for the fiscal year beginning 1 July 1919 called for “placing on inactive duty within 30 days of all female members of the Marine Corps Reserve, but also provided for the retention of such that were necessary and whose service was satisfactory, in the capacity of temporary civil service appointments, and about 75 percent were retained under this arrangement.”33

By July 1919, the urgent need for experienced clerical staff had diminished, in spite of the fact that most of the Marine ground forces would not return until August 1919.34 So, in July, to comply with the congressional direction, the Major General Commandant ordered “all reservists on clerical duty at Headquarters . . . to inactive status prior to 11 August 1919.”35

As is traditional in the Marine Corps, a farewell ceremony, including speeches from the Major General Commandant and secretary of the Navy, was conducted in honor of the female reservists departing active duty. The grand event, recognizing the service of the women Marine Reserves in time of great need, was held on the White House lawn. Both the Major General Commandant and the secretary applauded their commitment and performance.36

Based on their service, the female reservists earned several lifelong benefits. In addition to the option of burial in a national cemetery, these included:

- Eligibility for government insurance.

- $60 bonus on discharge and World War Adjusted Compensation at the rate of $1.00 a day for home service performed during the period from April 5, 1917, to July 1, 1919. Some states also provided a bonus for legal residents.

- Medical treatment and hospitalization under the regulations of the Veterans Administration for service connected disability.

- Five percent added to earned rating in examinations for entrance to classified service under Civil Service Regulations.37

The women who remained in the Reserves in an inactive status, serving out their enlistment, received a $1 monthly retainer pay until discharged at the end of their four-year enlistment. In addition, they were awarded a Good Conduct Medal and World War I Victory Medal when they were discharged from the Inactive Reserves.38

Once a Marine

The saying “Once a Marine, Always a Marine” was certainly ascribed to by female reservists. Although no longer a part of the uniformed Marine Corps, some women remained in government service working for the Marine Corps. One was Jennie F. Van Edsinga. Van Edsinga joined in September 1918 and was released from active duty to complete her enlistment as a corporal in the Inactive Reserve on 31 July 1919.39 Corporal Van Edsinga changed her name to Jane F. Blakeney in 1921 after marrying Arthur Blakeney, a fellow Marine, while she was still in the Inactive Reserve.40 Before retiring from civil service, Jane Blakeney rose to head the Marine Corps’ Decorations and Medals Branch at Headquarters Marine Corps.41

Blakeney’s reference book, Heroes, first published in 1957 and dedicated to her late husband Major Arthur Blakeney, remains a significant source of information on Marines earning medals for valor from the Civil War era to 1955 and includes histories and facts about the highest military medals awarded by our country.42 With this book, her contributions to Marines, their families, and historians, which began in 1918, continue through today.

Another of the original female reservists who remained with the Marine Corps was Private Alma Swope. She worked in the Supply Department for more than 44 years. She was the last female reservist from World War I who worked in the civil service to retire. When she retired in 1963, General David M. Shoup, Commandant of the Marine Corps, personally congratulated Swope on her service to Corps and country.43

Two of the World War I female reservists, Lillian O’Malley Daly and Martrese Thek Ferguson, came back into the Corps for World War II.44 One of these two, Martrese Thek Ferguson, ordered to the Division of Reserve, Headquarters Marine Corps, in April 1952 for training, extended her active service into the Korean War era.45

Lillian O’Malley Daly, then Lillian C. O’Malley, enlisted in the Marine Corps Reserve (F) in November 1918, moved to an Inactive Reserve status as a corporal on 31 July 1919, and remained in the Inactive Reserve until her four-year enlistment period was complete. She was discharged on 8 November 1922.46 Later married, she came back into the Marine Corps as a reservist with a direct commission to captain, one of only eight women who entered the recently authorized Marine Corps Women’s Reserve (MCWR) as an officer in early 1943, straight from life as a civilian. Daly was assigned as the West Coast liaison officer for the MCWR.47

Marine Corps Reserve (Female) and U.S. Navy Reserve (Yeomen) march in one of the numerous wartime pa- rades in Washington, DC, in 1918–19. Defense Department (Marine Corps) 521222

LtCol Martrese Thek Ferguson served on active duty in the Marine Corps Reserve during three wars: WWI, WWII, and on active duty for training at Headquarters Marine Corps during the Korean War. Official U.S. Marine Corps photo A412893

As the West Coast liaison officer, Daly represented the Marines at various civilian functions.48 By January 1944, she was the adjutant for the Women Reserve Battalion, Headquarters, Fleet Marine Force, San Diego area.49 She transferred to the East Coast as a major in January 1945, assigned to the Women’s Reserve Battalion at Marine Corps Base Camp Lejeune, North Carolina.50 The end of World War II found her assigned to 3d Reserve District, Marine Barracks, Navy Yard, New York.51 Daly was listed in the Officers Volunteer Reserve, 4th Marine Corps Reserve District, as a major in 1952, promoted to lieutenant colonel on the Inactive Status Personnel list in October 1952, and last noted on the October 1957 roll “Inactive Status List, Officer Volunteer Reserve, 4th Marine Corps Reserve and Recruiting District, Philadelphia,” while a lieutenant colonel.52 There was no indication she served in an active-duty status during the Korean War-era, although she was carried on the Reserve rolls in an inactive status.

Martrese Thek enlisted in the Marine Corps Reserve (F) on 7 September 1918 in New York City and was assigned to Headquarters Marine Corps.53 When released from active duty, she returned to civilian life, married, and as Martrese Thek Ferguson, reentered the Corps as a cadet in the newly formed MCWR in April 1943.54 That same month, she graduated first in the initial women officers’ course conducted at Mount Holyoke College, Massachusetts.55 By the end of the war, she was a major and commanding 2d Headquarters Battalion, Headquarters Marine Corps, Henderson Hall, Virginia.56 In March 1952, Lieutenant Colonel Ferguson was again on the Marine Corps’ muster rolls, now called the Unit Diary (UD), as a reservist in Company C, Headquarters Battalion, Headquarters Marine Corps, Henderson Hall, Virginia, in the Office of the Division of Reserve.57 She was transferred to the “Inactive Status List” in 1956.58

Assistant Secretary of the Navy Franklin D. Roosevelt, fourth from the left, with the Secretary of the Navy Josephus Daniels standing to his left, join USMCR(F) Marines and Navy Yeomen (F) at their final review in Washington, DC on 30 July 1919. National Archives, Record Group 127G, photo 530164A

Making Their Mark

While the active duty for those women who labored so intently to serve the Marine Corps and the nation in time of war was limited to not quite one year, it was impactful. In his annual report to the secretary of the Navy, prepared for Congress in 1919, the Major General Commandant noted, “The termination of hostilities on Nov. 11, 1918, precluded the practical working out of the principal idea in enrolling women in the Marine Corps Reserve for clerical duty, namely, that of releasing for active service in the field practically all the enlisted men who had been and were being utilized in the performance of such duties. However, the majority of the women so enrolled rendered capable and efficient service, and about 75 percent of them have elected to remain on in a temporary civil status as provided by the Act of July 11, 1919, so that the working efficiency of those headquarters and the staff and recruiting offices outside of headquarters at which women were stationed has not been interfered with by the sudden demobilization of the female reserve.”59

It would be 24 years and another great world war before the Marine Corps once again turned to women to meet wartime manpower needs.

• 1775 •

Endnotes

*This article, one in a series devoted to U.S. Marines in the First World War, is published for the education and training of Marines by the History Division, Marine Corps University, Quantico, VA, as part of the Marine Corps’ observance of the centennial anniversary of that war. Editorial costs have been defrayed in part by contributions from members of the Marine Corps Heritage Foundation.