The nineteenth century surged to a close on a wave of technological advances. “When we take into account the marvelous products of inventive genius with which the present century abounds . . . we can hardly find it rational to doubt the possibility of anything,” proclaims a 1 April 1898 Atlanta Constitution article discussing the possibility of a transatlantic telephone cable. The article asserts that “[s]cience within the century now drawing to a close has converted the world into one vast neighborhood.”2 Nowhere was this more apparent than in the press. The late nineteenth century saw the rise of popular newswire services, such as the Associated Press (AP), Reuters, and Agence France-Presse, and the advent of a “journalism of information,” which focuses on facts and a reporting style that “engages to convince readers of the authenticity of such ‘facts’.”3 With the expansion of the telegraph system, the relative ease and speed of steamship travel, and the laying of underwater cables, news was no longer local but global.4

These technological advances along with the rise of the global press proved to be fortuitous developments for the Marine Corps. While most historians agree that the seeds of the Corps’ modern expeditionary mission were planted during the Spanish-American War, few have analyzed how press coverage of Marine exploits during the war pulled the Corps out of the shadow of the U.S. Navy and established it as an independent player on the world military stage. An examination of press coverage of three events around the turn of the century—the attempt to disband the Corps in 1894, Marine actions in the war with Spain in 1898, and President Theodore Roosevelt’s Executive Order 969 that removed Marines from ships in 1908—shows a marked change in attitude about the Marine Corps. Press coverage of the Marine Corps during the war helped America develop an appreciation for the Corps, and aided in its evolution into an independently recognized and respected institution.

To understand the Marine Corps’ precarious position in the late nineteenth century, it is necessary first to examine the dynamic changes taking place within the Navy at the time. With an unprecedented increase in funding, the Navy began rapidly replacing aged wooden ships with modern battleships, cruisers, torpedo boats, and other steam-powered vessels. Having a modern, untried fleet encouraged the Navy to reexamine the business of war.5 Toward that end, in October 1884, the secretary of the Navy established the Naval War College in Newport, Rhode Island, and soon a crop of energetic young officers were envisioning a brilliant future for the Navy—a vision that saw no place for the traditional role of Marines on board ships.6

In contrast, the Marine Corps was desperately trying to survive. As historian Robert D. Heinl Jr. notes, the Marine Corps has always had “one foot in the sea, one foot on land, and its head perpetually under the sword of Damocles.”7 This was particularly true in the closing years of the nineteenth century. The Corps’ performance during the American Civil War had been lackluster. In 1864 and again in 1867, the Marine Corps faced abolishment or absorption into the Army. Both times, Navy leaders stepped in to save the Marine Corps. However, as the Navy transitioned to modern ships and ship-to-ship fighting became obsolete, Navy officials no longer saw a need for the traditional policing and boarding party duties the Marines had always performed. With increasingly specialized and skilled personnel on board its ships, the Navy found the likelihood of mutiny and general disgruntlement greatly diminished. Consequently, when the Corps’ existence was challenged again in 1894, the previously stalwart support of Navy leadership waivered.8

An article from 6 February 1894 reports on the proposed reorganization of the U.S. Navy, which lists the abolition of the U.S. Marine Corps as a minor part of planned changes. Photo courtesy of the Washington Post

On 5 February 1894, a bill to reorganize and increase the efficiency of the personnel of the Navy and Marine Corps was referred to a joint congressional subcommittee on naval affairs.9 Though the bill called for the eventual dissolution of the Marine Corps and its partial absorption by the Army, the American press paid little attention to the possible disbanding of the Corps. On 6 February, the Washington Post reported on page six a list of proposed changes to the rank structure, organization, and size of specific corps within the Navy. Midway down the column, the Post mentioned that the rank of colonel commandant would be terminated after the incumbent officer vacated the position and no further officer commissions or enlistments into the ranks of the Marine Corps would occur.10 The New York Times, like the Post, listed the Corps’ fate in the middle of a summary of the bill that also appeared on page six. The Navy’s loss of the rank of commodore and placement of limits on its list of active officers overshadowed the demise of the Corps.11 The Sun (Baltimore) ran an article on page two highlighting what “officers found objectionable” in the bill. The article included the planned dissolution by attrition of the Marine Corps but gave little emphasis to the issue.12

In a follow-up Post article, published 10 days later and appearing on page seven, the first hint of pushback against the Corps’ proposed demise surfaced. Senator Eugene Hale, the bill’s sponsor, noted that the proposed reorganization was “to avoid doing any injustice to any individual or corps . . . and to remove, as far as possible, all causes of contention among the several corps.”13 The New York Times reported on page four that “excitement and protest have been stirred up by the bill” and that it “antagonizes the staff corps and the Marine Corps by cutting down the former and abolishing the later.”14 The press was duly, if somewhat unenthusiastically, taking note of events taking place behind the scenes. In mid-April 1894, the Marine Corps’ first public statement ran in the papers, at which time the Post, on page 14, quoted a “prominent marine officer” as stating that the bill’s framers had forgotten that Marines were “the fighting men on board ships today” and that “in time of action it is the marine who can be called upon for everything.”15

Secretary of the Navy H. A. Herbert suspected that junior officers were behind petitions demanding the removal of Marines from Navy ships. Herbert’s circular warned that any naval officers found to be involved “would be visited unhesitatingly with the severe condemnation of the Department [of the Navy].” Congressional Record of Special Circular No. 16, 53 Cong. (9 August 1894)

Press coverage, though not blatantly supportive of the Marine Corps, still had a powerful impact on the future of the Corps. On 31 July 1894, Secretary of the Navy Hilary A. Herbert issued Navy Department Special Circular No. 16 to all U.S. naval commanders. Herbert stated he had received a petition from petty officers and men of a Navy vessel requesting Marines be removed from their ship. “This petition,” he stated, “contains an argument and is fortified by extracts from newspapers and periodicals, the circulation of which among the sailors is calculated to breed discord between them and the marines and their officers.” Herbert believed the inflammatory material was be- ing handed around “at the instigation, or at least with the knowledge and approbation, of certain commissioned officers of the Navy.” As required, Herbert forwarded the petition to Congress but clearly was not pleased. In a firm rebuke to his troublemaking junior officers, he stated that the Navy Department, “after maturely considering the subject” and “in view of the honorable record made by the United States Marine Corps,” was convinced Marines had a place on board Navy ships.16 The press picked up the circular’s theme. On 2 August, the Sun included a lengthy article on page two under the headline, “Defends the Marines.” The article related the contents of Herbert’s circular and voiced the criticism, “For a number of years, and especially since the completion of the first ships of the new navy, there has been an attempt made to prejudice the service against the marines.” The article put the blame for the petition firmly on the shoulders of Navy officers, and quoted Herbert as stating, “The government has not anywhere in its service a more faithful or efficient body of men than the United States Marine Corps.”17 Lacking a consensus, Congress eventually tabled the matter, and the Marine Corps survived the attempt to have it evicted from warships. Unfortunately, Congress failed to address the core question of the Marines’ role in the modern fleet, but the growing influence of the press, even a relatively disinterested press, was nonetheless becoming evident.

Press coverage of a relatively insignificant incident on 14 July 1894 illustrates the growing reach of the American media. While Congress and the Department of the Navy were still debating the fate of the Corps, the U.S. military was called to arms in Sacramento, California, which was in the throes of a railroad strike. The Army attempted to clear striking rail workers from the tracks to allow a train to pass. The situation deteriorated and shots were fired. The commander of the Marines at the nearby depot sent troops to help clear the streets. Marching with fixed bayonets, the Marines swept protestors before them as the Army cavalry rushed the crowd, a U.S. marshal leading the charge. Martial law was declared, and a restive calm returned to the city. News of the incident appeared in diverse publications, including the Los Angeles Times and the Chicago Daily Tribune, on the same day thanks to the AP.18 News of conflicts at home and abroad was common in the years leading up to the Spanish-American War, and the Marine Corps was consistently reported in the midst of them. More frequently, Marines would also find an intrepid reporter nearby, feeding stories of danger and heroism to an eager public.

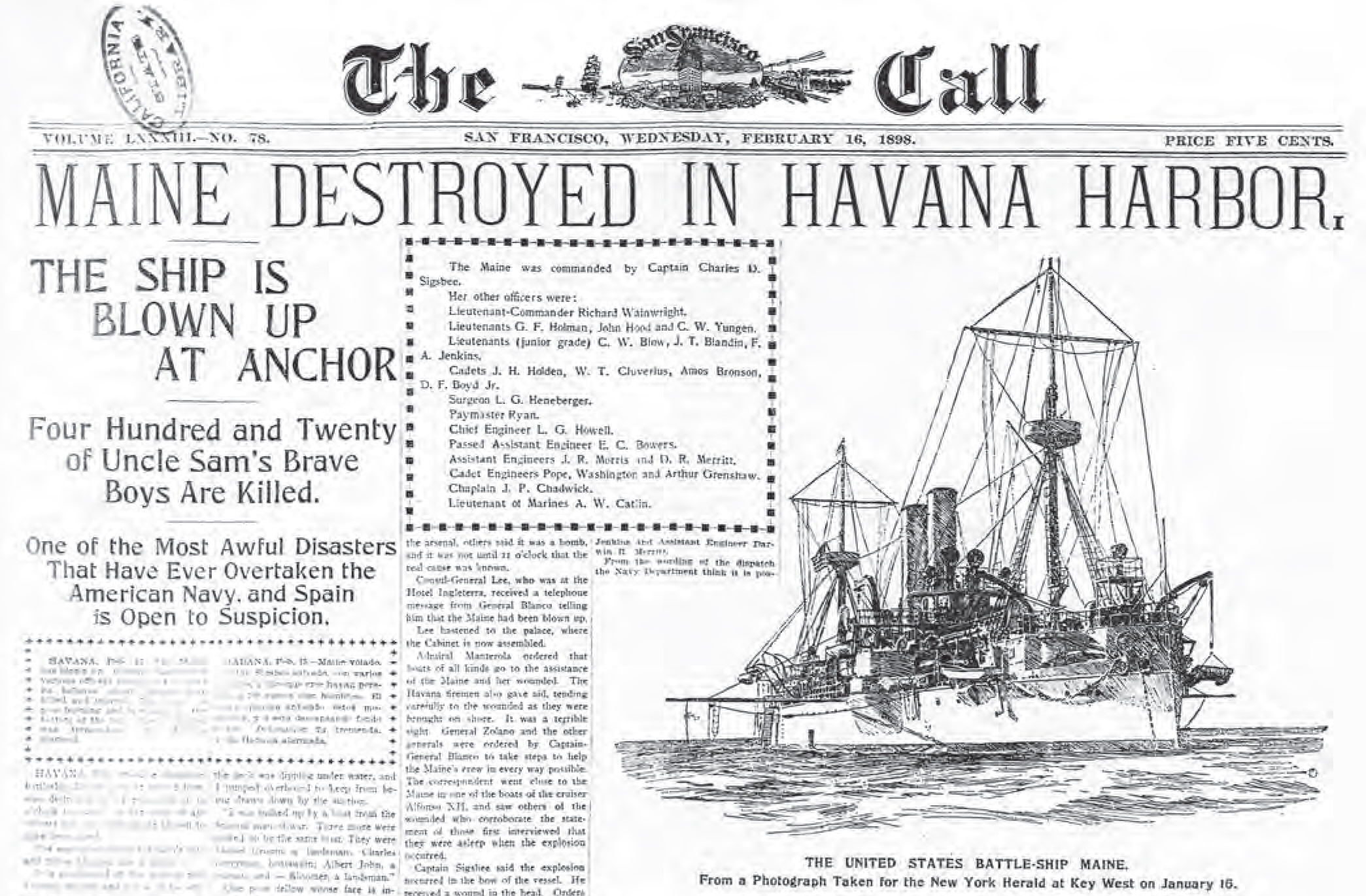

By the end of 1895, America was focused on a probable war with Spain. In Political Science Quarterly, an article on political events for the year noted that “the only topic of importance” was the United States’ attitude toward Spain regarding Cuban insurgents. “Many manifestations of sympathy with the insurgents,” the journal warned, “have appeared in all parts of the United States, and the so-called ‘Jingo’ press has advocated governmental action in their support.”19 In a 3 September 1895 speech to the Social Science Association, Commander Caspar F. Goodrich said that the Navy deprecated war but was “full of energetic officers who would quickly profit by any offered chance to distinguish themselves through valorous acts of seamanship and tactics. It is our business and our duty to our country and our flag, to contrive and to study, that we may be ready when the call sounds.”20 The Navy had a modern fleet that had never been tried in war, and its leadership was focused on a perceived “inevitable” war with Spain. No nation, according to Admiral Stephen B. Luce, could avoid war forever.21 The sinking of the USS Maine (ACR 1) by a mysterious explosion in Cuba’s Havana Harbor on 15 February 1898 spurred U.S. media headlines decrying treachery.22 Newspapers dispatched correspondents.

The sinking of the USS Maine (ACR 1) in Havana Harbor, Cuba, was the catalyst for the Spanish-American War and also caused American news correspondents to scurry to Cuba. Library of Congress, Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers

In the following days, U.S. newspapers speculated on Spain’s treacherous role in the disaster and demanded retribution. The U.S. military prepared for war, and the press covered every detail. Articles from across the country described men flocking to enlist, and many articles advised interested enlistees where recruiting stations could be found.23 The East Coast Navy yards experienced an influx of men ready to join. One recruitment story at the time illustrated the difference in relative status between the Navy and the Marine Corps. Charles B. Hobbs, who arrived at the Philadelphia Navy Yard in late April 1898, wanted to enlist in the Navy. Because he and a friend were neither seamen nor machinists, the Navy turned both away. The men then decided to “tackle the Marine Corps.” After enlisting and being sworn in, Hobbs and a fellow recruit donned their uniforms and headed into town. The local boys greeted the Marine recruits with shouts of “Halleuah” and “Amen, brother.” The Marines soon realized they were being mistaken for members of the Salvation Army.24 Despite articles that detailed Ma- rines at the Charlestown Navy Yard in Boston, Massachusetts, preparing to “maintain the record of the Corps,” the public and press seemed to have a vague understanding of the Marine Corps’ relationship to the Navy.25 Articles about “Brave Bill Anthony” the “Hero of the Maine” exemplified the apparent confusion. Private William “Bill” Anthony was a Marine orderly on the Maine when it exploded in Havana Harbor. Meeting Captain Charles D. Sigsbee in the smoke-filled corridor outside of his quarters, Anthony calmly stated, “Excuse me, sir, but I have to inform you that the ship is blown up and sinking.”26 Almost identical versions of Anthony’s heroism appeared in newspapers in Holbrook, Arizona; Shiner, Texas; and Chicago, Illinois, among others. Each article clearly identifies Anthony as a Marine but states that he spent 10 years in the Army before enlisting in the Navy, “and there he has since remained.”27 Before the Spanish-American War, this treatment of Marines as a mere corps in the Navy was common in the press and led to a somewhat muddled identity among the populace.

As the nation mobilized troops and massed an army of invasion in Tampa, Florida, press coverage of the war began to change. Many newspapers had correspondents in Cuba, but not all did. Those without access to overseas correspondents relied on traditional stateside sources. The “old-fashioned” articles speculated on events and couched their stories in terms of the broader concerns of their sources. Newspapers with deployed correspondents or access to AP reports filled their pages with eyewitness ac- counts, which relied on technology to get the story home to the states. As a result, newspapers became increasingly interested in the military’s control over the flow of information. Newspaper articles decried the lack of information available about ship and troop movements, both in the United States and Spain.28 Members of the press speculated that, despite being a signatory of an international convention against “interference with cables,” the United States had cut the telegraph cable from Key West, Florida, to Cuba.29 These were not baseless concerns or complaints. In fact, as soon as it arrived in Cuba, the U.S. Navy asked for volunteers to cut the cables in Havana Harbor. Though members of the press chafed at the military’s limitations on the flow of information, they still reported the cutting of the Havana-Santiago cable in heroic terms.30 The eyewitness accounts of events abroad changed the nature of newspaper articles.

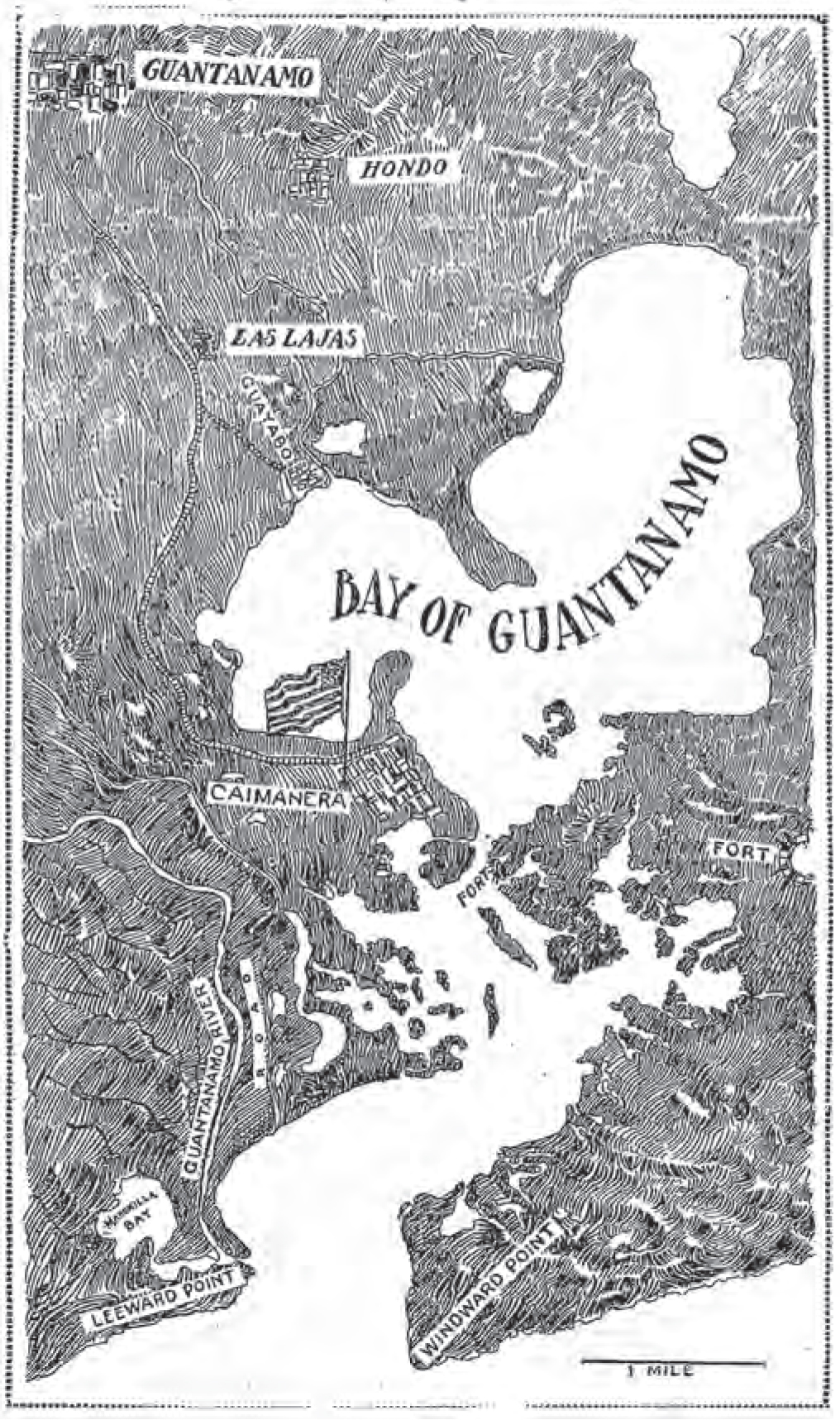

Differing coverage of the landing of Marines at Guantánamo Bay, Cuba, in June 1898 is an example of this change. A front-page article in the Boston Daily Globe on 12 June declared: “Navy Wins: Guantanamo Seized by Uncle Sam’s Sea Soldiers.” The article’s subhead admonished the Army to hurry as the “Sailors Have Taken the Bloom Off the Peach.” Similar to coverage of the 1894 bill to disband the Marine Corps, the article only mentions Marines in passing and depicts the “race for glory” as one between the Army and the Navy.31 In contrast, the Chicago Daily Tribune ran an article the same day that gives an eyewitness account of the action and includes a sketch of Guantánamo Bay, complete with a waving U.S. flag. The correspondent describes Lieutenant Colonel Robert W. Huntington as “a handsome and soldierly man, with prominent, clear cut features” who was “considered one of the best officers in the service.” The article also notes that “Color Sergeant Silvey and Private Bill Anthony, late of the Maine, are warm friends, having been messmates for fifteen years.”32 The personal details and the sketch of the bay created a memorable account of events and personalized the war for readers back home. And that article was just a foreshadowing of the personalized articles on the Marines that would come out of the war.

Library of Congress, Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers

As the war began with only the Navy and Marine Corps participating, vivid and detailed stories of the fighting filled the newspapers. An AP article in the Wheeling Daily Intelligencer described how a battalion of Marines landed from the transport ship USS Panther (AD 6) under the command of Lieutenant Colonel Huntington and had “been engaged in beating off a bush attack by Spanish guerrillas and regulars since 3 o’clock Saturday afternoon.” The reporter relates the tragic death of Army surgeon John B. Gibbs in a way that makes readers feel they are personally witnessing the scene: “He was shot in the head in front of his own tent, the farthest point of the attack. He fell into the arms of Private Sullivan and both dropped. A second bullet threw dust in their faces. Surgeon Gibbs lived ten minutes, but did not regain consciousness.”33 The difference between the vivid eyewitness accounts in the Tribune and Intelligencer and the traditional style used in the Globe article is apparent, illustrating the power the war correspondent had to personalize the war for the stateside reader. The old style of citing an unnamed special correspondent to give a partisan view of events became overshadowed by the gripping personal drama depicted in the stories of the embedded reporter. In addition, on-scene reporters understood the distinction between the Marine Corps and the Navy, and carefully reported who took part in what action, unlike the Boston Daily Globe’s special correspondent who framed his story in vague terms of the “glory” of one Service over another.

Reporters such as Stephen Crane, Silvester Scovel, Charles Thrall, Alex Kenealy, and Hayden Jones took great personal risk to get their information, and were often given credit for their stories by name, which was unusual at that time. Thrall and Jones were even arrested, jailed in Cuba, and held for two weeks before U.S. troops arrived and ransomed them.34 Crane, who was part of “the first American Newspaper to open a headquarters on Cuban Soil,” was a special correspondent for the New York World.35 He covered every moment of the Cuban campaign, often following troops into combat, and even served as an aide for Captain George F. Elliott during the battle for Cuzco well. The Marine Corps especially benefited from Crane’s reporting. Crane was with the Marines for the landing at Guantánamo Bay, their three days of continuous fighting, and the taking of the freshwater well at Cuzco, which finally secured the bay as a safe harbor for the Navy.36 Some of Crane’s most vivid stories were depictions of messages being signaled, or wigwagged, from shore to ship. Crane—whose stories often referenced the courage a signalman needed to expose himself to the enemy in order to relay his message—had great admiration for the signalmen. One of Crane’s stories tells of Huntington coming to the signalmen one night to send a message. “So the colonel and the private stood side to side and took the heavy fire without either moving a muscle,” Crane wrote. According to Crane, one officer was so concerned for Huntington’s safety that he asked the colonel to step down. “ ‘Why, I guess, not,’ said the grey old veteran in his slow, sad, always gentle way. ‘I am in no more danger than the man’, ” Crane wrote.37 Crane’s vibrant and intimate details revealed the character of the men he wrote about and personalized the war for readers back in the states.

While embedded with the Marines at Guantanamo Bay, American writer Stephen Crane wrote accounts of the heroic actions he witnessed. Special Collections Research Center, Syracuse University Libraries

Perhaps the most influential story Crane wrote was that of Sergeant John H. Quick during the battle for control of the well at Cuzco. The crew of the USS Dolphin (PG 24), which was providing gunfire support, was unaware that a Marine company had moved to flank the enemy. When the ship’s guns unwittingly fired on the Marines’ position, Captain Elliott, the ranking Marine present, called for a signalman. Crane related the events that followed:

Sergeant Quick arose and announced that he was a signalman. He produced from some- where a blue polka-dot neckerchief as large as a quilt. He tied it on a long, crooked stick. Then he went to the top of the ridge and, turning his back to the Spanish fire, began to signal to the Dolphin To deliberately stand up and turn your back to a battle and hear immediate evidences of the boundless enthusiasm with which a large company of the enemy shoot at you from an adjacent thicket is, to my mind at least, a very great feat. I saw Quick betray only one sign of emotion. As he swung his clumsy flag to and fro, an end of it once caught on a cactus pillar, and he looked sharply over his shoulder to see what had it. He gave the flag an impatient jerk. He looked annoyed.38

For his actions, Quick received the Medal of Honor. After the initial run, Crane’s story was reprinted in McClure’s Magazine and in a book of war stories Crane published after the war.39

While Crane was perhaps the most famous war correspondent at the time, he was not the only correspondent. First-person accounts of the war by AP reporters, for example, filled the pages of newspapers in such places as Los Angeles, California; Anaconda, Montana; Sacramento, California; Wheeling, West Virginia; and Willmar, Minnesota, and helped put a personal face on the war.40 War reporting had become big business.

In fact, after the war, McClure’s Magazine printed a five-page article titled “How the News of the War is Reported,” that discussed the high cost newspapers had incurred to get the story, including paying correspondents and insuring and supplying dispatch boats to ferry stories to Key West, Florida. According to the article, after the sinking of the Maine, “half a hundred great newspapers began to fill with news and pictures.” Reporters had nearly unlimited access. Many U.S. Navy warships, including Admiral William T. Sampson’s flagship the USS New York (ACR 2), had correspondents on board. Onshore correspondents like Crane used complex systems to meet dispatch ships and transmit news.41 This well-funded and well-organized system allowed for more intimate coverage of the war than the public had experienced during previous conflicts. While it is impossible to specifically gauge whether Crane’s vivid stories of Marines in Guantánamo influenced Americans’ attitudes toward the Corps, the Spanish-American War undoubtedly brought the Marine Corps into the national spotlight.

That spotlight did not fade with the war. Soon, Marines were on the ground in the Philippines, China, and Guam, and stories of their exploits appeared regularly in U.S. newspapers.42 But despite the coverage, trouble was stirring once again for the Corps. Even as Congress voted to improve pay for Marines and to increase their numbers, a new attempt to disband the Corps was brewing. This time, however, when the news hit the papers, the press was anything but disinterested.

On 10 December 1906, Chief of the Bureau of Navigation Rear Admiral George A. Converse testified before the House Committee on Naval Affairs that the Marine Corps belonged onshore—emphasizing that the Corps was an expeditionary force not a police force.43 Four months later, after much debate, Navy Secretary Victor H. Metcalf tabled the matter, stating that the issue of Marines serving on ships had already been decided. Unfortunately for the Marine Corps, the debate did not end there. President Theodore Roosevelt agreed with Admiral Converse that the Marine Corps should be an overseas expeditionary force and a domestic garrison. Roosevelt, a close friend of Army General Leonard Wood, also believed the Corps could better perform those duties as part of the Army.44 On 12 November 1908, Roosevelt issued Executive Order 969, which defined the duties of the United States Marine Corps.45 Metcalf resigned due to ill health, and on 18 November, Truman H. Newberry, acting Navy secretary, on mandate from Roosevelt, ordered Marine detachments off Navy warships.46

President Theodore Roosevelt’s Executive Order 969 regarding the duties of Marines caused a firestorm in the press and launched congressional investigations into the status of the Marine Corps and the power of the president. National Portrait Gallery, NPG.68.28

The executive order evoked an immediate response in the newspapers. The New York Times ran a front-page article stating that the president “promulgated the order on the recommendation of a number of line officers of the navy” and that the order resulted in “deep and grievous grumbling within the Marine Corps.”47 A similar page-one article in the Sun (Baltimore) stated, “As a result of the efforts of navy officers to relegate the Marine Corps, the President today issued an executive order removing the marine detachments from all men-of-war.”48 News articles celebrating the Corps’ proud history began appearing in newspapers across the country. The Boston Daily Globe published a poem titled “Semper Fidelis” that opens with a lament about the Marine Corps being pushed out to “temper the spleen of the sailor man.” It lists past glories of the Corps and acknowledges that in peacetime the country could survive without the Marines, but warns of a time when America would “want the brawn of the ‘Leathernecks’ ” but “the want may be in vain.”49 An article in the Youth’s Companion explains the presidential order, gives a brief history of the Corps, and concludes that Marines “performed deeds which have made them respected by the other branches of the service, and loved by all the people.”50 Whether the other Services respected the Marines was debatable; however, no reason existed to doubt the affection the American people now felt for the Marine Corps.

Unlike previous attempts, the president’s order did not specifically threaten to abolish the Marine Corps—it merely delineated the Corps’ duties and serving on ships was no longer among those duties.51 The public was outraged. One day after the executive order was signed, an article in the Chicago Daily Tribune speculated that, since the president was “depriving” the Marines of sea duty, the Army would eventually absorb the Corps.52 By December 1908, a move was afoot in Congress to counter the order. On 12 December, the Sun reported that some congressmen wanted to overturn the president’s order; a “prominent member of the House” warned that “if the Naval Committee did not take some step to defend the Marine Corps, a provision would be offered on the floor of the House expressing disapproval of the President’s policy.”53 The Senate also took action. On 17 December, it passed a resolution questioning the president’s authority to remove Marines from ships and referred the matter to the Senate Committee on Military Affairs.54 The House acted first. On 7 January 1909, the House Subcommittee on Naval Academy and Marine Corps began questioning Navy officers to “elicit information as to the present and prospective status of the Marine Corps.”55

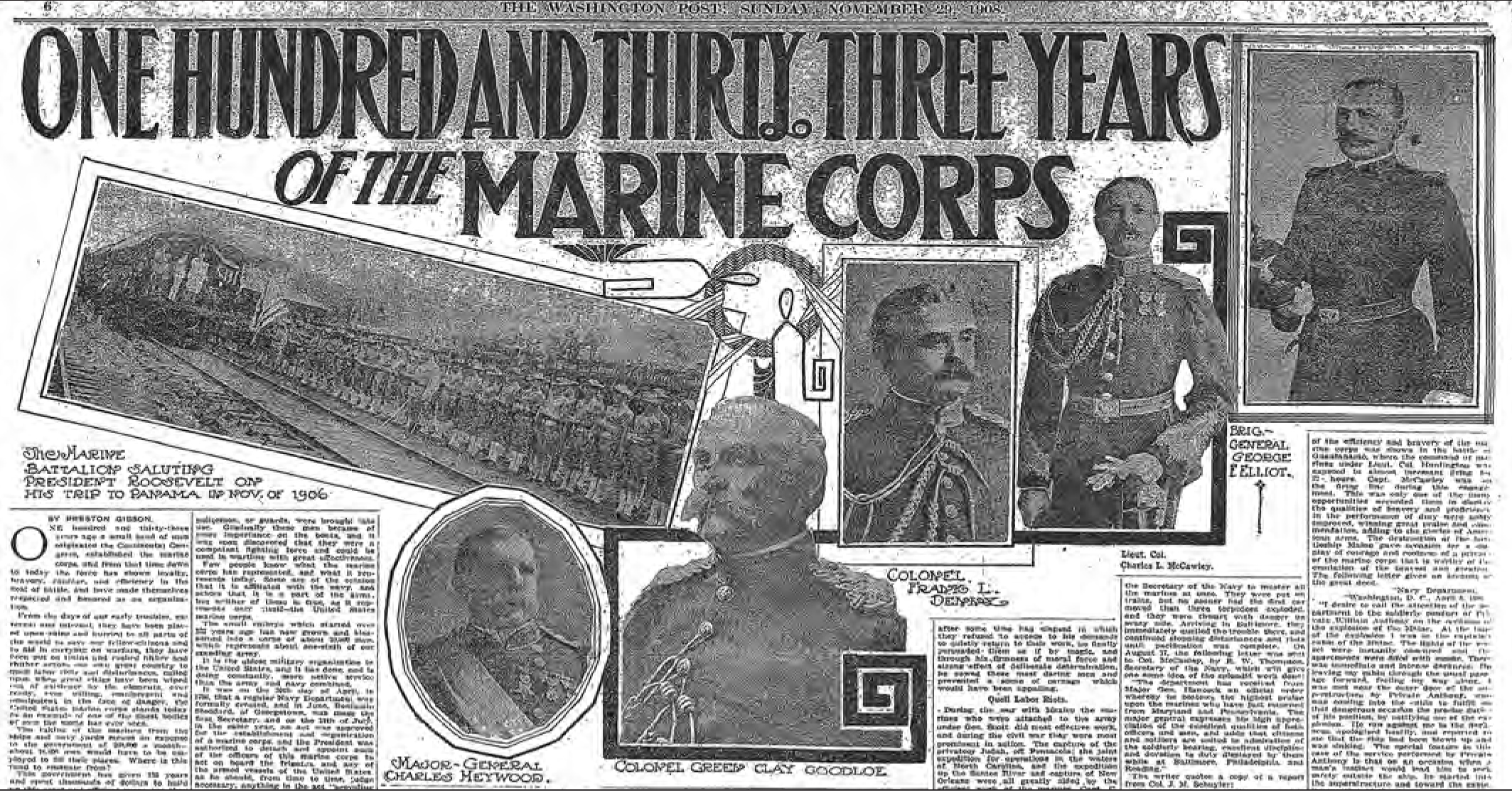

A full-page article in the 29 November 1908 Washington Post was just one of several that appeared in newspapers across the United States in response to Executive Order 969. Unlike in 1894, the press extensively covered this threat to the Marine Corps. Photo courtesy of the Washington Post

A parade of Navy officers testified. The majority of those officers stated they favored the removal of Marines from ships but preferred to retain the Marines rather than lose them to the Army. Meanwhile, newspapers churned out stories. The Washington Post editorialized that Marines were removed from Navy ships because they “irritated” sailors. “To set against the splendid service of marines aboard ship . . . the mere fact that they irritate the sailor, which has not been proved,” the editor argued, was no reason to deny Marines their traditional role.56 Articles in support of Marines appeared in the Atlanta Constitution, Boston Daily Globe, New York Times, Christian Science Monitor, and Outlook weekly magazine, among others.57

The prevalent news coverage of the Marine Corps was even introduced into the Congressional Record. Testimony revealed that Commander William Fullam was behind the 1894 movement to remove Marines from Navy ships and that he had written the letter to Secretary Herbert in 1906 that instigated the situation Congress was currently investigating. Fullam was ordered to appear before the committee.58 When he finally took the stand, Fullam engaged in combative exchanges with the board. Confronted with testimony from the head of the Navy’s Bureau of Navigation that “bluejackets” (sailors) had never complained about Marines being on ships, Fullam contended that the Marines were untouchable and that complaining was pointless because the Corps’ “influence” was too strong to fight. Queried for details, Fullam replied that sailors saw statements “all through the newspapers” that Marines must be kept on board ships to control them. He introduced articles from the Greenville News (North Carolina), a Dallas, Texas, paper, and the New Orleans Picayune to support his point. “The mere fact that such things are published abroad, broadcast over this country,” Fullam argued, “is reason enough for withdrawing the cause of it.”59 Building on those statements, he reasoned that this public attitude influenced junior officers, who, as a result, learned not to trust their men. In short, Fullam maintained that the superiority of the Marines, as perpetuated by the press, kept the Navy from reaching its full potential. Additionally, he claimed that press coverage “seriously injures the reputation of the blue jacket among the people at large, and affects the recruiting, and affects respect for his [the sailor’s] uniform.” Fullam also added that having Marines on ships “creates a privileged military class, subordinating the blue jacket to a man who is in no respect his [the sailor’s] superior and is, in many respects his inferior.”60

Predictably, the Commandant of the Marine Corps, then Brigadier General George F. Elliott (and coincidentally the officer in Crane’s wig-wag flag account at Cuzco well), took offense and interrupted the proceedings. Fullam refused to back down, asserting that Marines were “looked up to as the élite corps aboard ship . . . that they have insisted on their being the élite corps.”61 Fullam’s hostile attitude brought a series of rebuttals from the Marine Corps and from the congressmen present. The board dismissed Fullam’s arguments as unfounded. The subcommittee determined that the president had insufficient reasons for removing the Marines, and also found that the cost of removal would be more than if Marines simply returned to shipboard duty. Congress then made the Naval Appropriations Act of 1910 contingent upon Marines serving on board Navy ships.62

RAdm William F. Fullam was behind the 1894 and 1909 attempts to remove Marines from U.S. Navy ships. Fullam believed that Marines should be an expeditionary force—a position the Marine Corps later embraced. Library of Congress, LC-DIG-ggbain-19371

Heinl argues in his article “The Cat with More than Nine Lives” that practicality saved the Corps in the days between the Civil War and World War I. While true, practicality was not the Corps’ only saving grace. In “Evolution of the U.S. Marine Corps as a Military Elite,” Dennis Showalter writes, “The change of the Marine Corps’ status is inseparable from the emergence of the modern war correspondent.”63 Undeniably, the growing power of the press played a part in maintaining the status of the Corps. In fact, most historians of the Spanish-American War mention the influence of the press in some way. Piero Gleijeses focuses on the power of the press in his 2003 article, “1898: The Opposition to the Spanish-American War.”64 John A. Corry contends in 1898: Prelude to a Century that yellow journalism and the “heat of public opinion” forced America into war with Spain. In support, he quotes a Maine congressman as saying, “Every Congressman had two or three newspapers in his district . . . shouting for blood.”65 If the press had the power to nudge a nation toward war, it certainly had the power to save a long-standing branch of the armed forces. While no evidence conclusively shows that newspapers and public sentiment swayed Congress to save the Marine Corps in 1909, it is clear that the attitudes of the press and the public toward the Corps distinctly changed between 1894 and 1909. The press, like the country, was just finding its footing and flexing its muscles at the turn of the century. Newspapers and, by extension, the American people began looking at the Marine Corps with new interest and affection. Heinl writes that the modern Marine Corps has become a “unique, vital, and colorful part of the American scene.”66 If that statement is accurate, that process began in Cuba with men like Sergeant Quick and his wig-wag flag and Stephen Crane and his pen.

• 1775 •

Endnotes