The Early Days

The Marine Corps Reserve Flying Corps (MCRFC) did not get off the ground rapidly after Congress authorized the Naval Appropriations Act of August 1916. At that time, aviation in the Marine Corps was still in its infancy, and the early leaders in Marine Corps aviation were fighting hard to gain men, equipment, and flying fields, working closely with the U.S. Navy. Oversight of Marine aviation came through a section at Headquarters Marine Corps, and little is known of the organization and administration of the budding MCRFC.1

In its youth at the beginning of World War I (WWI), Marine aviation can be traced back to the first Marine naval aviator, First Lieutenant Alfred A. Cunningham. He appeared on the rolls of the Naval Aviation School, U.S. Naval Academy, Annapolis, Maryland, as the “Only Marine Officer Present” in May 1912.2 By August 1912, he was the first qualified Marine naval aviator.3 Cunningham became known as the “Father of Marine Corps Aviation,” but not simply because he was the first aviator.4 He was a driving force in all early Marine aviation activities and particularly in readying the MCRFC for duty in the war.

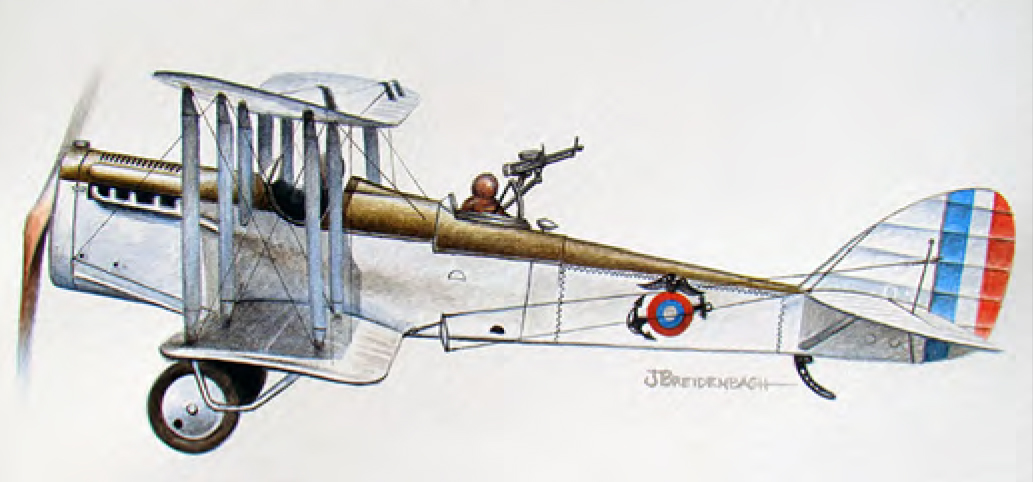

“The DH-4 and the Marines in World War I,” a watercolor by aviation artist Jason Breidenbach, shows the aircraft that Marines successfully flew in WWI. Courtesy of Leatherneck magazine

Bringing on the Marine Corps Reserve Flying Corps for War

When the United States entered WWI, the Marine Corps had six Marine officers classified as naval aviators; although none were identified as reservists.5 But the surge was on, and a large segment of the buildup in aviation manpower came via Marine Corps recruiting efforts, selecting highly qualified Marine enlisted men for aviation training and the Navy Reserve flying programs.

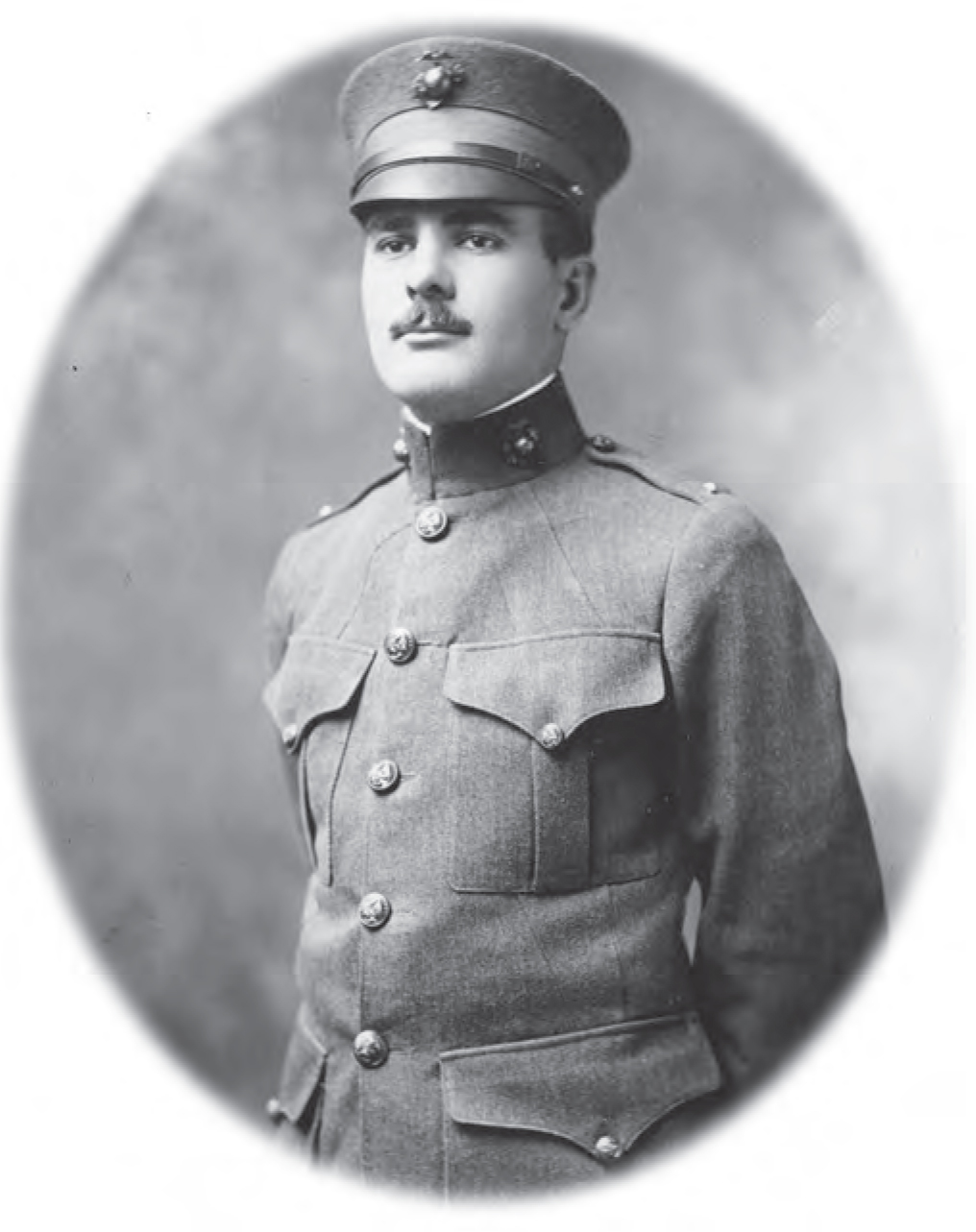

Quick to get into the action, the first Marine Corps Reserve officer reported for aviation duty less than a month after war was declared. Reserve Marine Second Lieutenant Edmund G. Chamberlain was listed as “on aviation duty” on the muster roll of the Aeronautic Company, Advanced Base Force, Philadelphia Navy Yard, Pennsylvania, from Houston, Texas, on 2 May 1917. Chamberlain earned his wings as Naval Aviator No. 96 ½ and remained in Marine Corps aviation during the war, but not as a reservist.6 He integrated into the Marine Corps on 6 September 1917, prior to earning his naval aviator designation. Chamberlain was followed by Second Lieutenant Marcus A. Jordan from Washington, DC, who was listed as “on aviation duty” on 18 May 1917.7 By early July 1917, Jordan was posted on the muster roll of the 7th Company, 5th Regiment, at the Philadelphia Navy Yard and dropped from aviation duty, but remained in the Marine Corps Reserve.8 Jordan never lost his love of aviation, and it eventually cost him his life. He deployed to France with his regiment and, on 16 October 1917, worked his way back into aviation through attachment to the Aviation Section, Signal Corps, U.S. Army, where he was ordered to the Aviation Training School in Foggia, Italy, for “instructions in flying.” Jordan took his first training flight on 28 October 1917.9 Advancing rapidly, he took his last training flight on 6 November and became an “Instructor of Cadets in Machine Gunnery.”10 While attached to the 8th Aviation Instruction Center in Foggia and still a second lieutenant in the Marine Corps Reserve, but not a designated naval aviator, he was killed on 27 March 1918 in a crash during a training flight near Foggia.11 To more effectively build and prepare a Marine Corps aviation organization for war, just three weeks after the U.S. declaration of war in April 1917, the relatively small Marine Aviation Section, U.S. Navy Air Station, Pensacola, Florida, was divided with some of the Marines forming the Marine Aeronautic Company, Advanced Base Force, Philadelphia Navy Yard, under the command of Cunningham. At Pensacola, the training had been focused on seaplanes. The new aviation unit at Philadelphia was to be a combination land and water unit with training in seaplanes, land aircraft, and observation balloons.12 On 12 October 1917, to refine aviation organization and focus flight skills, aircraft types, and missions, the Marine Aeronautic Company was split into two units: 1st Marine Aeronautic Company and 1st Aviation Squadron.13

Lt Edmund G. Chamberlain, as a Marine first lieutenant aviator during WWI. Courtesy of Leatherneck magazine

The 1st Marine Aeronautic Company, with 10 officers, only one who—Captain Francis T. Evans—was designated a naval aviator, and 96 enlisted men, emphasized seaplane operations and relocated to Naval Coastal Air Station Cape May, New Jersey. Among those officers arriving at Cape May on 14 October 1917 were two MCRFC officers who were not yet designated naval aviators: Second Lieutenants Alan H. Boynton and Amor L. Smith. Also on the initial muster roll of the 1st Marine Aeronautic Company was one Fleet Marine Corps Reserve sergeant and two privates in the National Naval Volunteers (NNV).14

Although deeply involved in training its potential Reserve pilots, the company immediately became operational, flying sea patrols from Cape May with its two Curtiss R-6 seaplanes.15 It became the first Marine Corps aviation unit to deploy in an operational mode for the war when, in January 1918, it arrived at Naval Base 13, Ponta Delgada, Azores, equipped and ready for sea patrols.16

The other unit formed from the Marine Aeronautic Company was 1st Aviation Squadron, commanded by Cunningham. The new unit, with 24 officers, including one Marine gunner, and 197 enlisted men, was moved a little later in October 1917 to an Army flying field, Hazelhurst Field, Mineola, Long Island, New York. Cunningham and the second senior officer, Captain Roy S. Geiger, spent a great deal of that month away from the unit, leaving Captain William M. McIlvain as the senior officer present in the new command. While none of the officers were noted as members of the Marine Corps Reserve on the muster roll, three sergeants and five privates were, along with three NNV.17 Of the initial 24 officers, only 3 were designated naval aviators: Cunningham, McIlvain, and Geiger.18

The Army’s Hazelhurst Field focused on training pilots for landplane flying.19 The Marines of 1st Aviation Squadron remembered Hazelhurst Field because of the intense cold and poor flying conditions.20 But the icy weather was not long endured as the Marine Corps’ search for an aviation training site in a more favorable climate paid off. On New Year’s Day 1918, the 1st Aviation Squadron, including 14 Reserve second lieutenants not yet designated Marine aviators,21 left Mineola for the more aviation-friendly weather of the Army’s Gerstner Field in Lake Charles, Louisiana.22

Marines in the newly formed 1st Aviation Squadron at the Philadelphia Navy Yard, prior to departing for Mineola, Long Island, NY, in October 1917. From the left: Sgt Ralph D. Henry, USMCR, clerk to the commanding officer; Capt Walter E. McCaughtry; 2dLt Walter H. Batts, USMCR; Capt Alfred A. Cunningham; 1stLt Edmund G. Chamberlain; and an unidentified Marine. Official U.S. Marine Corps photo 532357

Training and Qualifying Marine Corps Reserve Aviators

With Marine aviation training for landplanes now at Gerstner Field and seaplane operations at Cape May, another Marine aviation training site was being pursued by Geiger, who, with a small detachment including three MCRFC second lieutenants not yet designated naval aviators, moved south to Naval Air Station (NAS) Coconut Grove, Florida, in February 1918.23 Marine aviators, trained at this naval air station, earned their naval aviator designation flying seaplanes, but Geiger saw the need to get all the Corps’ early pilots, including the Marine reservists, to add the land dimension to their qualifications. He arranged for the Marines to use the old Curtiss Flying School strip near the Everglades. On 1 April 1918, the nomadic 1st Aviation Squadron arrived at its new home, the newly renamed Marine Flying Field Miami, Florida. With this move, Geiger and McIlvain’s units were combined and the 1st Marine Aviation Force (FMAF) was established.24 The training of pilots greatly expanded as the Navy permitted large-scale movement from its aviation units to the new Marine unit.25

Three of the Marine Reserve officers, who had been with the 1st Aviation Squadron from Philadelphia to Mineola and at the Marine Flying Field Miami with the recently activated FMAF, serve as good examples of the differing routes taken to become naval aviators in the MCRFC: William H. Derbyshire, Jesse A. Nelson, and Fred S. Robillard.

Second Lieutenant Derbyshire, Naval Aviator No. 533, was the first MCRFC officer to be designated a naval aviator.26 He did not enter via the U.S. Naval Reserve Flying Corps (USNRFC), as did most of the early Marine Reserve aviators, and was not former enlisted. He enrolled as a second lieutenant in the MCRFC at Marine Barracks Philadelphia on 26 September 1917 after graduating from Harvard and was assigned to 1st Aviation Squadron in Philadelphia.27 Second Lieutenants Boynton and Smith preceded Derbyshire’s enrollment in the MCRFC in September 1917 but were not designated naval aviators by the time Derbyshire qualified.28 Boynton, Naval Aviator No. 856, may well have been delayed in being designated a naval aviator because of the operational tempo of his unit, the 1st Marine Aeronautic Company, which began sea patrols off the East Coast followed quickly by deployment to the Azores. The reason for Smith’s precedence as Naval Aviator No. 2761 is less evident because he transferred from 1st Marine Aeronautic Company, Naval Coastal Air Station Cape May, on 5 November 1917 to join Marine Aviation Section, NAS Pensacola, where he remained until 12 January 1918 when he was transferred to Marine Barracks New York, and discharged in January 1918.29 He then joined the U.S. Army, commissioned a second lieutenant, and honorably discharged after the Armistice.30

Derbyshire trained at the Army flying field, Mineola, for landplane duty and qualified as a Reserve military aviator on 24 November 1917 and then moved with Geiger’s Aeronautic Detachment from Philadelphia to NAS Coconut Grove, where he was designated a naval aviator on 28 February 1918. He was injured in an aircraft accident in Miami on 12 March 1918 and remained on sick leave until September of that year. As a result of the accident, his designation as a naval aviator was revoked on 17 September 1918, and he was detached from aviation.31

The First 20 Marine Corps Reserve Naval Aviators

Naval aviator precedence numbers were used to identify the first Marine Corps Reserve Flying Corps (MCRFC) aviators. The first 20 Marine Corps Reserve naval aviators are listed below by name, naval aviator precedence number, and date of designation. All Marine Corps aviators listed here came via the U.S. Naval Reserve Flying Corps (USNRFC). Only 1 of these 20, Herman A. Peterson, entered the USNRFC via the National Naval Volunteers. Peterson enrolled in the New York Naval Militia on 2 March 1917 and was mustered into federal service at Bay Shore, New York, on 7 April 1917 and or- dered to Key West, Florida. He was assigned to 1st Marine Aviation Force (FMAF) at Marine Flying Field Miami, Florida, while still a lieutenant junior grade in the USNRFC. Peterson accepted an appointment as a first lieutenant in the MCRFC on 16 August 1918 while deployed with the FMAF in France.

Fractions in a naval aviator precedence number are the result of more than one aviator designated with that number. If the aviator originally enrolled as a Marine Corps Reserve officer but disenrolled from the Reserve and enrolled in the Marine Corps prior to being designated a naval aviator (e.g., Edmund G. Chamberlain), that Marine aviator is not listed.*

|

|

|

Name

|

Naval aviator number

|

Date designated

|

|

Bradford, Doyle**

|

111 ½

|

5 November 1917

|

|

Webster, Clifford L.

|

112 ½

|

5 November 1917

|

|

Wright, Arthur H.

|

148

|

6 December 1917

|

|

Peterson, Herman A.

|

163 ½

|

2 November 1917

|

|

Laughlin, George McC. III

|

165

|

12 December 1917

|

|

Ames, Charles B.

|

193

|

21 December 1917

|

|

Weaver, John H.

|

251

|

21 January 1918

|

|

Prichard, Alvin L.

|

279

|

21 January 1918

|

|

Willman, George C.

|

299

|

22 January 1918

|

|

Elvidge, Herbert D.

|

424

|

12 May 1918

|

|

Pratt, Hazen C.

|

426

|

8 March 1918

|

|

Clark, Sidney E.

|

442

|

8 March 1918

|

|

Schley, Fredrick C.***

|

443

|

8 March 1918

|

|

Needham, Charles A.

|

444

|

14 March 1918

|

|

Bates, John B.

|

449

|

25 March 1918

|

|

Talbot, Ralph

|

456

|

10 April 1918

|

|

Comstock, Thomas C.

|

473

|

26 March 1918

|

|

Clarkson, Francis O.

|

474

|

28 March 1918

|

|

Williamson, Guy M.

|

477

|

25 March 1918

|

|

Alder, Grover C.

|

479

|

25 March 1918

|

|

|

|

* The naval aviator precedence numbers and dates are from Kaufmann, 100 Years of Marine Corps Aviation, 314. Confirmation of the source of enrollment and status as a member of the Marine Corps Reserve, Class 5, is from “U.S. Marine Corps Muster Rolls, 1893–1958,” microfilm T977, 460 rolls, ARC ID: 922159, record group 127, Ancestry.com; and Reginald Wright Arthur, Contact! Careers of U.S. Naval Aviators Assigned Numbers 1 to 2000, Vol. 1 (Washington, DC: Naval Aviator Register, 1967).

** Civilian flight instructor with the U.S. Army prior to enrolling in USNRFC.

*** The spelling of his first name on muster rolls varies: Frederick, Frederic, and Fredrick. The muster roll of 4th Squadron, 1st Marine Aviation Force, Marine Flying Field Miami lists him as “disenrolled” on 17 August 1917.

|

|

Nelson’s Marine Corps service and ultimate qualification as a Marine Corps Reserve aviator began when he originally enlisted as a private on 27 June 1913. He reenlisted and, because of special skills, was appointed sergeant and assigned to the Aeronautic Company, Advanced Base Force, Philadelphia, in August 1917.32 Continuing to excel, Nelson was appointed Marine gunner in October 1917 while at Mineola and then commissioned a second lieutenant in the MCRFC on 21 December 1917. He relocated with the squadron to Gerstner Field in January 1918 and attained designation as Naval Aviator No. 589 while with the FMAF at Marine Flying Field Miami on 17 April 1918. He sailed for France with the FMAF in July 1918 and flew with the FMAF as part of the Day Wing, Northern Bombing Group, at La Fresne, France, until the end of the war. Nelson was among the few Reserve aviators who commissioned in the Marine Corps. He retired from the Corps be- cause of disability in December 1935.33

Robillard took a different route and served as another example of the MCRFC and its contributions to success in the Great War. He enrolled as a sergeant in the Marine Corps Reserve, Class 4c, on 30 June 1917 in Chicago. Initially sent to the Aeronautic Company, Advanced Base Force, Philadelphia, Robillard was on the roster when the company split, and he became an enlisted mechanic in 1st Aviation Squadron.34 He trailed along with the squadron to Mineola where he was appointed a second lieutenant, MCRFC, Class 5, then on to Gerstner Field with the 1st Aviation Squadron in early January 1918.35 Robillard then accompanied the squadron to join the FMAF at Marine Flying Field Miami, designated Naval Aviator No. 602 on 17 April 1918, and became a pilot in Squadron B, FMAF. He sailed with the FMAF to be initially assigned to Field “D” near Calais, France, for duty with the Day Wing, Northern Bombing Group, where he earned the Navy Cross for his actions alongside other Allied armies during operations along the Belgian front from September 1918 to the end of the war. He was released from active duty in 1919, but reentered the Marine Corps in 1921, and went on to a very distinguished career, retiring as a major general on 1 October 1952.36

The Marine Corps Reserve officer with the lowest precedence as a naval aviator, Herman A. Peterson, Naval Aviator No. 163 ½, entered the MCRFC through the U.S. Naval Reserve Force. Peterson had been a member of the New York Naval Militia, mustered into federal service with his Navy unit as a National Naval Volunteer on 7 April 1917 and designated a naval aviator on 2 November 1917.37 He is on the June 1918 FMAF muster roll; however, Peterson was still a lieutenant (junior grade).38 He was not discharged from the Navy Reserve to accept his appointment as a first lieutenant in the MCRFC until 16 August 1918 while in France.39 Peterson earned the Navy Cross “for distinguished and heroic service . . . while serving with the First Marine Aviation Force, attached to the Northern Bomb Group (USN), in active operation co-operating with the Allied Armies on the Belgian Front during September, October and November, 1918, bombing enemy bases, aerodromes, submarine bases, ammunition dumps, railroad junctions, etc.”40

Fred S. Robillard was enrolled as a sergeant in the Marine Corps Reserve in June 1917 due to his special skills as a mechanic. Commissioned in the USMCR on 17 December 1917, he later earned a Navy Cross in France. Official U.S. Marine Corps photo

The Marine Corps flew into a bit of friction with the Navy based on its rejection of a significant number, 17, of the USNRFC pilots who came to the FMAF from the Navy in late May and early June 1918.41 Cunningham was caught in the middle. Although listed on the FMAF muster roll in June 1918, Cunningham, now a captain, remained on temporary duty at Headquarters Marine Corps, leaving Geiger at Marine Flying Field Miami to evaluate the mix of officer and enlisted pilots arriving from the Navy in June.42 The course of instruction at Marine Flying Field Miami was very challenging. It included basic or preliminary flying; then advanced acrobatic and formation flying; and bombing, gunnery, and reconnaissance flights. The reconnaissance training included aerial photography.43

Despite being in Washington, DC, Cunningham, working for the Major General Commandant, continued his pursuit of additional aviation resources— people, aircraft, more airfields, etc.—while Geiger screened and trained would-be Marine aviators in Florida. On 11 June 1918, Cunningham wrote Geiger at Marine Flying Field Miami, “Note that the Board [run by Geiger] has turned down seventeen of the Navy pilots, and believe that they do not realize the conditions. As you know one-half of the pilots are nothing but machine gunners. The Navy have [sic] fallen down on us in the matter of giving more pilots.”44 At that time, early June 1918, the Reserves listed on the FMAF muster roll included 12 first lieutenants, 51 second lieutenants, 2 sergeants, 37 privates, 7 NNV and the muster roll listed as Navy, 2 assistant surgeons, 1 lieutenant (junior grade), 33 ensigns, and 1 seaman second class and 10 pharmacist mates.45

Training for aviators also was coordinated by the Navy at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), Boston, Massachusetts. Enlisted Marines selected as promising flyers were appointed temporary gunnery sergeants and ordered to a 10-week ground training course at MIT. After ground school graduation, they did their actual flying at Marine Flying Field Miami and, upon qualifying, commissioned second lieutenants in the MCRFC. The first class for enlisted Marines did not enter this program until 10 July 1918, so it did not have a significant impact on the number of qualified MCRFC pilots fighting in France.46

Captain Thomas R. Shearer: Texas Naval Militia Member, National Naval Volunteer, and Marine Corps Reserve Aviator

|

|

| |

Captain Thomas R. “Bull” Shearer was among the Marine Corps Reserve’s aviators who did not deploy to Europe during WWI but gained command stateside. Shearer began his journey to become a Reserve aviator via Company A, Texas National Naval Militia, Marine Corps Branch, in April 1917.1 Shearer is possibly the sole Marine aviator to gain wartime command with a career beginning in the Marine element of a state naval militia.

According to The Recruiters’ Bulletin of March 1917, Shearer “of Houston, Texas . . . organized and mustered into the state Service the first Marine Company in the Texas Naval Militia.” The 51-man company asked to be called “The McLemore Marines” in honor of Colonel Albert S. McLemore, the assistant adjutant and inspector of the Marine Corps, who headed Marine Corps recruiting.2

The Marine company was organized on 10 February 1917 with Shearer as its captain. On 6 April 1917, less than two months after the unit was created, the company was ordered to federal service, the day the United States declared war against Germany. 3 The same day, motivated Texans and their enthusiastic commander reported to the local rendezvous site in Houston. From there, the company members traveled to the federal rendezvous site in New Orleans, Louisiana, arriving on 12 April. There they were enrolled into the National Naval Volunteers (NNV).4

By late May, Shearer and his unit were stationed at Marine Barracks NAS Pensacola, Florida. In January 1918, while still a member of the NNV, Shearer was transferred to command the Marine Aviation Section at NAS Pensacola and began flight training to become a qualified seaplane pilot. 5 On 4 April 1918, he was designated Naval Aviator No. 559. Just one month later, as the commander, Shearer suspended himself from duty for five days for “flying in the fog.”6

On 1 July 1918, he transferred from the NNV, Marine Corps Branch, to the Marine Corps Reserve at the rank of captain. At that point, he became commander of the Marine Aviation Section, NAS Miami, and on 15 July 1918, he was placed in charge of all aerial patrols flying from the NAS. His unit flew the difficult air patrols in the Florida Straits until just after the Armistice.7

|

|

Official U.S. Marine Corps Photo

|

|

|

- Company A, Texas National Naval Militia, Marine Corps Branch, MRoll, 12–30 April 1917, Roll 0121. Ancestry.com.

- “Texas Marine Militia Company,” The Recruiters’ Bulletin, 3, no. 5 (March 1917): 29.

- Arthur, Contact!, 175.

- Company A, Texas National Naval Militia, Marine Corps Branch, MRol.

- Company A, NNV, Marine Barracks, Aeronautical Station, Pensacola, MRoll, 1–31 May 1917 and Marine Aviation Section, U.S. Naval Air Station, Pensacola, MRoll, 1–31 January 1918, Roll 0122, Ancestry.com.

- Arthur, Contact!, 175; and, Marine Aviation Section, U.S. Naval Air Station, Pensacola, MRoll, 1–31 May 1918, Roll 0139, Ancestry.com.

- Marine Aviation Section, U.S. Naval Air Station, Miami, MRoll, 1–31 July 1918, Roll 0143 and Marine Aviation Section, U.S. Naval Air Station, Miami, MRoll, 1–30 November 1918, Roll 0154, Ancestry.com.

|

|

|

|

However, the MIT program did provide pilots for the FMAF in France. One of the USNRFC officers who entered through the MIT program and later transferred to the MCRFC to serve with distinction in Europe was Ralph Talbot. In June 1917, Talbot left Yale University to join the DuPont Aviation School in Wilmington, Delaware. The war was on and he wanted to contribute. He enrolled as a seaman second class on 25 October 1917, completed the MIT ground training course, and was ordered to NAS Key West, Florida. There he was commissioned an ensign in the USNRFC on 8 April 1918 and then later designated Naval Aviator No. 456. Talbot took advantage of the Navy’s willingness to let its pilots transfer to the MCRFC at Marine Flying Field Miami and was commissioned a second lieutenant on 26 May 1918. In mid-July, Talbot deployed overseas with the FMAF and earned a unique place in Marine Corps history.47

A 1st Marine Aeronautic Company, 1st Marine Aviation Force Curtiss R-6 seaplane undergoes repairs at Naval Base 13, Ponta Delgada, Azores, in the fall of 1918. Extra wing crates and repair tents are in the background. Official U.S. Marine Corps photo 529928

Marine Corps Reserve Aviators Deploy to the Azores

The Germans had operated submarines in the Atlantic Ocean during the early years of the war, wreaking havoc on shipping, and there was concern that they might try to establish an advance base in Portugal’s Azores archipelago. The British had been watching the area and the U.S. Navy had used Ponta Delgada, São Miguel Island, Azores, for ship repairs. The U.S. Navy collier, USS Orion (AC 11) was in Ponta Delgada undergoing repairs when, early on the morning of 4 July 1917, German submarine U-155 began shelling the town. Orion returned fire, although her stern was out of the water, driving off the submarine.48 This helped make the decision to get Portuguese consent to establish a shore installation at Ponta Delgada.49

Bombing Mission in DeHavilland 9’S by John T. McCoy. Watercolor on paper. Art Collection, National Museum of the Marine Corps

On 7 December 1917, the 1st Marine Aeronautic Company—with its experience flying sea patrols from Cape May—was selected to deploy to the Azores and establish shore installation (Naval Base 13) at Ponta Delgada, and the company began flying antisubmarine patrols. The company arrived with 10 Curtiss R-6, 2 Curtiss N-9 seaplanes, and 6 Curtiss HS-L flying boats on 22 January 1918.50 Among the Marines arriving at Naval Base 13 in January were one MCRFC officer, Second Lieutenant Boynton, two Marine Corps Reserve privates, and four NNV privates.51

In the Azores, the Aeronautic Company Marines flew daily patrols out to a radius of 70 miles off the island, most often monotonous with little, if any, contact.52 The Marines were ordered back to the United States on 24 January 1919, arriving at Marine Flying Field Miami on 15 March 1919.53 The company strength for March (7 officers and 60 enlisted men) included 2 Marine Corps Reserve officers (Class 5 and Class 1) and 3 Marine Corps Reserve enlisted.54 Also deployed to Naval Base 13 in January 1918 was a Marine 7-inch naval gun unit, commanded by Captain Maurice G. Holmes.55 The unit, Foreign Expeditionary Detachment, Naval Base 13, and its 51-Marine detachment included six members of the Marine Corps Reserve, Class 4.56 Holmes commanded the detachment through the Armistice, departing on 22 November 1918.57 The guns were later turned over to the Portuguese rather than transported back to the United States.58

Marine Reserve Aviators in the War in Europe

Involvement of Marine Corps aviation in WWI came about through the initiatives of Cunningham, although it was supported by the Major General Commandant, other officers at Headquarters Marine Corps, and U.S. Navy leadership. The German submarine menace had to be curtailed; and bombing of the Belgian submarine shelters (or pens) in Zeebrugge, Ostend, and Bruges was a mission taken on by the U.S. Navy. The Navy dispatched a limited force to France in June 1917 to initiate the bombing but did not have enough air assets. Cunningham, during a visit to the front in late 1917, saw an opportunity for Marine aviation to get into the action by assisting the Navy. Cunningham asked for and received a Marine force of a headquarters and four squadrons in early 1918 and now, with the United States about a year into the war, Marine aviation had a combat assignment.59 The Marine Corps needed pilots to support the Navy’s mission, so the Navy permitted its pilots to transfer to the MCRFC in May and June 1918.

The FMAF—with its headquarters and Squadrons A, B, and C that arrived in Brest, France, on board the USS De Kalb (ID 3010) on 30 July 1918 to join the Day Wing, Northern Bombing Group—demonstrated the significance of the almost two-year-old Marine Corps Reserve.60 The FMAF included 272 members of the Marine Corps Reserve and six NNV out of a total of 787 men—35.3 percent were Marine Corps Reserve and NNV. The representation of the Marine Corps Reserve was dramatic among the officers: 12 of the 17 first lieutenants, or 71 percent; 71 of 77 second lieutenants, or 92 percent; and 11 of 11 Marine gunners, 100 percent.61

With Cunningham commanding FMAF, the flying squadrons were commanded by Captain Geiger, Squadron A; Captain McIlvain, Squadron B; and Captain Douglas B. Roben, Squadron C.62 These squadron commanders, plus the future commander of Squadron D, First Lieutenant Russell A. Presley, arrived in France as an advance party, coordinating with the Navy’s Northern Bombing Group, around mid-June 1918.63 Squadron D did not join the Day Wing until after landing in France on 5 October 1918. This squadron added 222 Marines and Navy men to the Day Wing, of which 102 were Marine Corps Reserves—34 of 39 officers were reservists.64 When the FMAF became the Marine Day Wing of the U.S. Navy Northern Bombing Group, the four Marine squadrons were redesignated the 7th, 8th, 9th, and 10th Squadrons, respectively.65

With a shortage of aircraft, Cunningham turned to the British Royal Air Force (RAF), with its numerous available aircraft and lack of fully trained pilots, for his FMAF pilots to gain flight time. Marine pilots and observers were assigned to RAF Squadrons 217 and 218 to fly combat missions over the German lines.66 One of these pilots, MCRFC Second Lieutenant Chapin C. Barr, flying with Squadron 218, died on 29 September 1918 of wounds received in a combat raid over enemy territory.67 Barr was awarded the Navy Cross for his actions in combat and was the first Marine aviator to die as a result of enemy action.68 Also, while flying with Squadron 218, Marine pilots participated in the first aerial resupply on 2 and 3 October when food was dropped to a surrounded French unit.69 One of the three Marine pilots participating in that food drop was MCRFC Second Lieutenant Frank Nelms Jr., who earned a Navy Distinguished Service Medal for his actions.70

The first Marine aircraft destroyed in air battle in WWI also resulted in the pilot, 2dLt Harvey C. Norman, MCRFC, and observer, 2dLt Caleb B. Taylor, MCRFC, above, Squadron C, FMAF, being killed in action. Their aircraft was attacked by seven enemy aircraft on 22 October 1918 over the Bruges-Ghent Canal, Belgium. Official U.S. Marine Corps photo 530634

The first all-Marine air combat operation was a raid carried out on the morning of 14 October by Squadron C (9th) from La Fresne flying field. The Marines attacked the German-held railway junction and yards at Thielt, Belgium, with a composite flight of five DH-4s and three DH-9As, led by Captain Robert S. Lytle.71 In those eight squadron aircrews, five pilots were Marine Corps reservists and one, Ensign Elmer B. Taylor, was a member of the USNRFC assigned to the squadron. Three of the eight observers/gunners in the aircraft rear seats were Marine Corps reservists.72

On the return flight, the Marine aircraft were intercepted by enemy aircraft; and a group of German Fokker fighter planes attacked Second Lieutenant Talbot and his observer, Corporal Robert G. Robinson, whose aircraft had separated from the flight due to engine trouble. Robinson, firing the rear-mounted machine gun, shot down one of the attacking aircraft, but in another onslaught, his left elbow was shattered. He continued firing until again wounded, this time in the abdomen and thigh, when he collapsed. Talbot attacked the Fokker with his front guns, shooting down one additional aircraft then with continuing engine problems, he dropped low, crossed the German lines, and landed at a Belgian airfield to obtain aid for Robinson.73 After dropping off Robinson, Talbot again lifted into the air, despite engine issues, returning to La Fresne flying field.74 Both Talbot and Robinson were awarded the Medal of Honor for “extraordinary heroism” for earlier operations and this raid, thus, earning the first two Medals of Honor awarded to members of Marine Corps aviation units, although Talbot’s was presented posthumously.75 Talbot was killed on 25 October 1918 when he crashed into a bomb dump at La Fresne during a maintenance test flight. He did not make it into the air, ripping off his landing gear as he tried to pass over the bomb dump embankment. He died in his burning aircraft.76 First Sergeant John K. McGraw, Fleet Marine Corps Reserve, Class B, earned the Navy Cross that day for “extraordinary heroism,” when he prevented a massive explosion of the bomb dump.77 When Talbot crashed, McGraw led the nearest men in moving burning bomb crates, rolling the bombs in mud, and extinguishing the fire.78 Talbot’s observer/gunner, Reserve Second Lieutenant Colgate W. Darden Jr., Class 5, flying in the rear seat was thrown clear of the aircraft and survived the accident. Darden later became a member of the General Assembly of the Commonwealth of Virginia, member of the U.S. House of Representatives from Virginia, governor of Virginia, and president of the University of Virginia.79

Raid on Thielt by James Butcher. The first all-Marine aviation raid was on Thielt, Belgium, on 14 October 1918 by 9th Squadron, 1st Marine Aviation Force. 2dLt Ralph Talbot, MCRFC, and Cpl Robert G. Robinson were awarded the Medal of Honor for their heroic actions in the raid. Art Collection, National Museum of the Marine Corps

In addition to the Marine aviators of FMAF in France, six Marine officers were detached and assigned to the Army Air Service, American Expeditionary Forces.80 At least one of the six, Second Lieutenant Marcus A. Jordan, was a member of the Marine Corps Reserve.81 Another enrollee in the MCRFC in 1917 already had combat experience in France. Russell F. Stearns had been a pilot, with the rank of corporal, in the Lafayette Flying Corps prior to America entering the war. Stearns had gone to France to serve in the American Ambulance Field Service in 1916, then enlisted in the Lafayette Flying Corps on 12 April 1917. He qualified as a pilot and was assigned to Escadrille Spad 150, piloting the French Spad biplane in combat during 27 December 1917–24 February 1918. He returned to the states on leave in February and, while home, applied for a discharge from the Lafayette Flying Corps and joined the Marine Corps Reserve. Unfortunately, general health issues followed him from France, and he did not qualify as a naval aviator and was disenrolled from the MCRFC on 30 July 1918.82

Examining the Marine Corps muster rolls of the FMAF, Naval Air Forces, France, American Expeditionary Forces, at the time of the Armistice in November 1918, reveals that 111 of 132 officers, or 84.1 percent were Marine Corps reservists; 15 of 15, or 100 percent of the warrant officers were reservists; and 228 of 783, or 29.2 percent of the enlisted men were Marine Corps reservists.83

The Day Wing, Northern Bombing Group, received orders to return to the United States and embarked at Saint-Nazaire, France, on 16 December 1918, arriving at Newport News, Virginia, five days later.84 Delivering supplies and the bombing raids by these early Marine aviators became routine missions in later wars and insurgencies. In its short time in existence, the MCRFC made its mark and helped ensure Marine Corps aviation continued to flourish.

2dLt Ralph Talbot entered the USMCR via the Naval Reserve Force, with ground training at MIT. Ralph Talbot Personal Papers, Marine Corps Archives and Special Collections, Marine Corps University

The port of Saint-Nazaire, France, December 1918. Ralph Talbot, Personal Papers, Marine Corps Archives and Special Collections, Marine Corps University

• 1775 •

Endnotes