PRINTER FRIENDLY PDF

EPUB

AUDIOBOOK

United States Marines’ actions during the Nicaraguan Campaign (1927–33) underscored the significance for fighting as a Marine air-ground task force (MAGTF) in future wars. Marines were deployed and tasked to protect national interests abroad on more than 20 occasions before the Nicaraguan Campaign, and once more, Marines and sailors would be called upon to stabilize Nicaragua and protect U.S. business interests in the Central American region.1 By training and employing the Guardia Nacional, deliberately incorporating and integrating Marine aviation, and utilizing the synergistic effects of the MAGTF concept (in a modern sense), Marines effectively countered General Augusto Sandino’s insurgency and delayed a Nicaraguan civil war. Marine operations within an integrated combined-arms team ultimately proved the worth of the MAGTF concept and laid the foundation for future conflicts. The annexation of California and subsequent discovery of gold prompted the United States to create a transisthmus supply line linking the American Pacific Coast regions and Southeast Asia to Atlantic Ocean areas. Transit across the Central American isthmus was a faster route to the West and lessened the dangers posed by moving supplies across the continental United States or around the Cape Horn of South America.2 However, increasing instability in Central America and the potential for a “European intervention” on the isthmus threatened American financial and subsequent political interests in the future construction of a transisthmus canal system.3 The security of the American population and growing U.S. financial investments, particularly in Nicaragua, seemed to rest on “stability throughout the [Central American] isthmus.”4

Historically, Nicaragua suffered “under the lash of rebellion” due to ongoing clashes between conservative and liberal parties and localismo: a “fierce civic pride, which magnified economic jealousy and enabled petty leaders to raise armies [and] overthrow the national government.”5 The inability to align politics in Nicaragua after the disestablishment of the Federal Republic of Central American in 1839 served as the greatest destabilizing factor for Nicaragua far into the 1920s.6 However, the combination of these two phenomena was only increased by the continual battle for economic power within Nicaragua as each new leader struggled to maintain peace in the country. Over time, diplomatic and economic efforts of the United States produced only minimal stabilizing gains in Nicaragua, ultimately resulting in the U.S. administration’s decision to declare “the supremacy of the power of the United States in Central America.”7

Map adapted by W. Stephen Hill

U.S. interventions in the Central American region had produced little stability in Nicaragua by the end of 1926. President Theodore Roosevelt negotiated a peace treaty among the Central American nations in 1907, preventing the unification of Central America under a liberal Nicaraguan influence. President William H. Taft, Roosevelt’s successor, implemented the Dollar Diplomacy that, one year later, extended U.S. commercial and financial interests to foreign governments, including Nicaragua, and supported increased international domestic growth. By 1909, the mishandling of Nicaraguan governmental affairs and economy by liberal President José Santos Zeyala spawned a civil war that lasted throughout much of the next 16–17 years. Increasing political and domestic instability amplified the rising threat to American political and economic interests, unfortunately, climaxing with the death of an American citizen in December 1926.8 The “total disregard for American lives and property” left President Calvin Coolidge no choice but to “do everything in his power to protect American interests in Nicaragua,” and send in the Marines.9

The Nicaraguan Campaign (1927–33) utilized diplomatic and military powers to disarm Nicaraguan factions, maintain regional security, and increase the legitimacy of Nicaragua, while protecting U.S. business and economic interests. Henry L. Stimson, emissary of the United States, worked with the Nicaraguan government to broker the disarmament of Nicaraguan factions. Alongside disarmament efforts, the 2d Brigade, led by Brigadier General Logan Feland, formed the basis of a MAGTF in the early part of 1928, which included six scout bomber aircraft that supported his infantry and logistics units. General Feland’s intent was not to campaign in Nicaragua but to pursue Sandino offensively using combined air and ground forces to force Sandino to flee the country.10 As Sandino’s forces resisted, U.S. Marines and sailors began occupying and patrolling the land and sky in the west and central regions of Nicaragua to bring order to the countryside and disrupt the operations of Sandino’s forces. Concomitant with offensive combat operations, Marines also set out to rebuild and legitimize an indigenous guard force capable of assuming national security responsibilities in the future.11 By the end of the campaign in January 1933, the Marines and sailors had not only disrupted Sandino’s rebels and reinvigorated a competent national guard, but also increased combat capability as “Marine aviators and infantrymen” began functioning as an air-ground team.12

BGen Logan Feland. Official U.S. Marine Corps photo

Major Ross E. Rowell possessed extensive experience in Marine aviation and commanded the first squadron of de Havilland DH-4 aircraft that supported 2d Brigade. He, along with other Marine aviators, like Alfred A. Cunningham, believed that Marine aviation’s primary role was supporting the Marines on the ground. The character of aviation operations supporting the Marine maneuver elements aligned around “the functions of observation aviation, of ground attack aviation and another which may be referred to as air transport service.”13 Major Rowell worked with ground commanders and the brigade commander to conduct observation of the enemy, close air support, and air transport of Marines and logistics in support of operations on the ground. Major Rowell commented in his report that the “trust and consideration enjoyed at the hands of the Brigade and Area Commanders has resulted in a splendid esprit among the officers and men of the air units.” This esprit de corps carried forward not only shattered the cohesiveness and morale of Sandino’s insurgency, but also laid the foundation for further combined-arms integration.14

Transport plane flying over the Nicaraguan coast. Official U.S. Marine Corps photo

Maj Ross E. Rowell was a strong believer in the value of aircraft support for ground troops. Official U.S. Marine Corps photo

Deliberate campaigning executed by Marines and sailors occurred generally from January 1927 until the spring of 1929. During these two years, the 2d Brigade “launched three major offensives against the Sandinistas” to purge the rebel forces from Nicaragua.15 From July 1927 to the end of 1928, Marines and sailors on the ground and from the air conducted western and eastern offensives, forcing Sandino’s rebels on the defensive. Marine aviation supported both offensives by delivering supplies and messages to and from the field, providing aerial reconnaissance, and attacking hostile ground forces (modern day close air support). Additionally, Marines provided security for the 1928 Nicaraguan elections and oversaw the training and integration of an indigenous guard force, the Guardia Nacional.

Brigadier General Feland phased ashore more than 2,000 Marines and sailors in the initial stage and “launched a desultory campaign into Nueva Segovia to disperse Sandino’s ever-growing band” of rebels to stop the bleeding.16 The brigade’s offensives during the summer of 1927 and into the spring of 1929 concentrated the bulk of the force to defeat Sandino forces in the Nuevo Segovia and Jinotega regions and along the Coco River from the east. By the summer of 1928, more than 5,000 Marines and sailors secured population centers and established combat outposts in the northwest and north-central regions of Nicaragua, namely Quilalí, Ocotal, El Chipote, and Poteca.17 Marines and sailors, once established, conducted security patrols to keep Sandino’s rebels from interfering with overlapping efforts to integrate Guardia Nacional troops and ensure security for the impending governmental elections in 1928.18

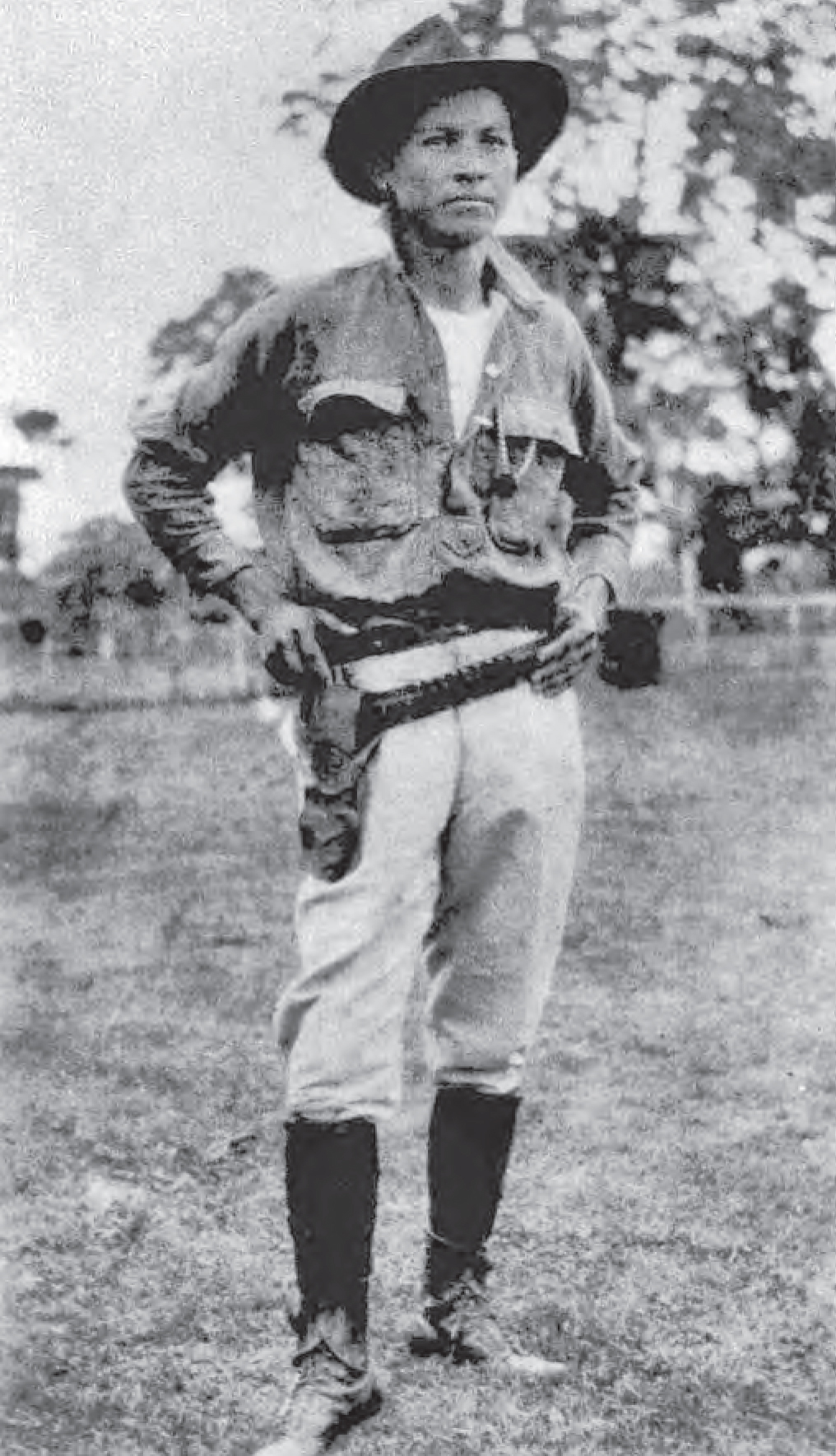

Purported picture of Augusto Sandino. Official U.S. Marine Corps photo

U.S. Marines and the Guardia Nacional

The Guardia Nacional was officially reconstituted at the request of Nicaraguan President Adolfo Diaz in May 1927. The Guardia’s first director, Lieutenant Colonel Robert Y. Rhea, focused throughout much of 1927 and 1928 on recruiting, training, and retaining an all-volunteer, nonpartisan force led by Marine commissioned and noncommissioned officers. By the start of 1929, the Guardia Nacional began assuming responsibilities for much of the patrolling in the sectors of Nicaragua and was integrated into offensive operations. Three years later, the men of the Guardia Nacional manned the majority of the combat outposts and operated with Marine forces, serving primarily as the ready reserve with minimal assistance from Marine mentors.19

In 1927, the Guardia Nacional was envisioned to be a nonpartisan force, loyal to the Nicaraguan leadership and capable of defending the government against further rebellion. The responsibility for organizing, training, and employing the Guardia Nacional was initially tasked to the Marine Corps, and the Marines and sailors selected to carry out this mission did so until the end of the campaign in 1933. Organizationally, the general headquarters of the Guardia Nacional reported directly to the president of Nicaragua and was commanded initially by Lieutenant Colonel Rhea in May 1927, succeeded in August of that same year by Brigadier General Elias R. Beadle.20 The Guardia Nacional was structured into four regional combat divisions and contained separate companies that supported the headquarters, recruiting, and replacement functions.21 The responsibility for the training and employment of the Guardia Nacional, however, fell primarily on junior Marine and Navy commissioned and noncommissioned officers selected and assigned to lead this all-volunteer force.

Marines shown with Guardia Nacional troops. Official U.S. Marine Corps photo

Training the Guardia Nacional was not as organized or developed as the structuring of the force seemed to be. First, Marine and Navy commissioned and noncommissioned officers lacked formal training in the “social, cultural, and value systems of the native Nicaraguan.”22 The lack of cultural training was problematic throughout the campaign because some Nicaraguans did not respond favorably to an American style of discipline—one that collided with Nicaraguan sensitivities and resulted in several mutinies.23 Second, Guardia Nacional basic and combat skill training lacked standardization, and its execution was primarily delegated to the local area commanders. Guardia Nacional enlistees, usually spending about a month in basic training, were sent to field units where they learned basic academic and soldiery skills “on the job.” As Brent Gravatt noted, “. . . if the recruit lived long enough . . . he became a competent soldier by practice.”24 Third, formal military training for junior and senior native officers emerged too late in the campaign. The Guardia Nacional lacked the requisite amount of combat-experienced officers to lead the force by the departure of the Marines in 1933.25

Despite perceived shortcomings in organization and training, the Guardia Nacional developed into a competent fighting force by the end of the campaign in 1933 due to the efforts of Marines and sailors. For the first couple of years of the campaign, the Guardia Nacional was employed to man outposts and conduct patrols and limited offensive operations under the supervision of and alongside Marines and sailors. From 1929 to 1932, the Guardia Nacional troop counts and combat effectiveness increased, enabling them to accept all patrol duties and locally lead in many campaign operations that followed.26 The organization, training, and employment of the Guardia Nacional by the Marines and sailors during the course of the campaign provided Nicaragua with a legitimate, competent guard force able to fully support its developing government.

Group shot of a Marine leader in front of two rows of Guardia Nacional troops. Official U.S. Marine Corps photo

The responsibility of “Middle Stage: Inpatient Care—Recovery” rested on the shoulders of the newly elected government and the Guardia Nacional around the spring of 1929.27 Operationally, the Guardia Nacional, comprised of about 2,000 soldiers, integrated into the northern and western regions of Nicaragua and became the main force to occupy combat outposts and conduct security patrols alongside and in place of Marines and sailors. The strategy to establish an active defense concentrated the preponderance of the Guardia Nacional forces in the heart of insurgent country and incorporated offensive search-and-destroy missions that minimized the threats posed by Sandino’s rebels (akin to modern day operations conducted by U.S. forces in Afghanistan and Iraq).28 That same summer in 1929, Sandino departed Nicaragua for Mexico to request assistance for the insurgency. Unfortunately, when Sandino returned one year later, rebel forces faced a competent and experienced Guardia Nacional force that ably disrupted his operations during the next stage of the campaign.29

The 2d Brigade force retrogrades and the transfer of authority of Nicaraguan regions to the Guardia Nacional in 1929 marked the overlap of the “Middle Stage: Inpatient Care—Recovery” and the “Last Stage: Outpatient Care—Movement to Self-Sufficiency.”30 The integration of Guardia Nacional forces into the operations of the campaign subsequently allowed the number of Marines and sailors required in Nicaragua to be decreased. Specifically, from February to December 1929, the 2d Brigade’s total strength was reduced by almost two-thirds.31 The Guardia Nacional, by the summer of 1930, conducted the majority of security and stability operations as Marines and sailors provided transition assistance and served as the “ready reserve” force.32

By the end of 1932, the Guardia Nacional assumed all responsibilities for maintaining security and stability in Nicaragua, and on 2 January 1933, the Nicaraguan Campaign ended as the last of the Marines and sailors departed Nicaragua for the United States.33 Military operations subsequently waned in attractiveness leading up to the 1932 elections that brought conservative party leader, Juan B. Sacasa, back to the head of government as the Nicaraguan Campaign ended.34

Testing the MAGTF: Combined-Arms Operations and the Single Battle

Up to this point in history, the Marine Corps had not been able to leverage the full energy of the MAGTF as Marine aviation had been in its infancy. The series of operations that consumed the preponderance of the Nicaraguan Campaign demonstrated the effectiveness of the “air-ground team,” linking aviation operations to the ground scheme of maneuver and coupled with supporting logistical sustainment. The Marine air squadron, commanded by Major Rowell, combined aerial observation, ground attack, and air transport aviation operations to increase the combat power of the Marine ground elements in squashing Sandino’s insurgency.35

Supporting the ground commander with infantry liaison (communications relay) and visual reconnaissance (intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance) missions consumed the majority of the sorties flown during the campaign. Ground commanders were enabled by Marine aviation to communicate with combat outposts and patrols that “penetrated far into the heavily forested mountains and remote jungles of [Nicaragua].”36 Infantry liaison missions essentially linked field commanders with the outlying patrols, providing the means for passing patrol reports and communicating routine and emergency support requests. Visual reconnaissance flights, usually conducted in conjunction with infantry liaison, augmented ground intelligence mechanisms and assisted in providing the field commanders with information beyond what was discernible from the ground. The two combined missions dramatically increased the field commander’s situational awareness beyond what he could see and his ability to command and control subordinate elements from a distance.37

Marines are loading an Atlantic-Fokker C-2 transport plane with supplies for Marine ground troops. The tractor and trailer were used to carry equipment and supplies overland. Official U.S. Marine Corps photo

Aerial observation (modern day forms of close air support and armed reconnaissance) combined the “use of aircraft in organized warfare” to attack hostile ground forces and augment ground maneuver and surface fires (modern day combined-arms operations).38 Marine aviators routinely conducted ground attack in advance of deliberate operations (the deep fight) or when Sandino’s forces presented themselves as targets of opportunities, attacking insurgent strongholds and maneuver columns inflicting many casualties and “severely [punishing]” large enemy forces in places such as El Chipote and Murra.39 Marine aviators also attacked targets in close proximity and direct support of security patrols and combat outposts ably defeating and dispersing Sandino’s forces—notably, at Ocotal in 1927 and Sapotillal Ridge in 1928.40 Aerial observation and fires, augmenting ground maneuvers, and surface based fires minimized Sandino’s ability to mass and organize his forces and provided the ground combat elements with a distinct combat advantage on the battlefield.

Transporting supplies and personnel using Marine aviation “broadened and increased” the 2d Brigade’s operating zone and efficiency. According to Major Rowell, “there is not a military situation on record where the air transport service has had such a valuable and important part.”41 The introduction and use of the Atlantic-Fokker C-2 transport aircraft gave the 2d Brigade a distinct logistical advantage over Sandino’s rebels in many aspects:

Entire garrisons in the most remote localities [depended] wholly on the transports for supply, an entire regimental headquarters was transported to the front, minor troop movements [were] effected, the sick and wounded [were] evacuated, casual officer and enlisted [were] carried, the mail [was] delivered and emergency articles and materials of every conceivable nature [were] delivered with the greatest speed and safety.42

Additionally, in contrast with mule trains that spent 10 days to three months delivering personnel and supplies to combat outposts, Marine aviation delivered “2,000 pounds of cargo or eight fully equipped Marines per flight” in about “one hour and 40 minutes.”43 By the end of the campaign, Marine aviation had made contact with the enemy 300 times and transported 20,749 passengers and 6.5 million pounds of cargo in 31,296 sorties in support of the 2d Brigade and Guardia Nacional operations on the ground.44

The effective use of aerial observation, ground attack, and air transport operations reinforced the 2d Brigade’s capabilities to rapidly locate and strike Sandino’s forces with a relative combat power advantage at the times and places of the Marines’ choosing. The combined effects of aviation and ground combat forces not only successfully outpaced Sandino’s insurgency and proved the worth of functioning as a capable air-ground team, but the synergy gained in this new concept, the MAGTF, proved its worth for future Marine Corps’ operating concepts.

The 2d Brigade executed a successful campaign in Nicaragua by not only employing the Guardia Nacional and conducting offensive operations to frustrate Sandino’s rebellion but also by incorporating its new air-ground team in combat operations. The operations of the six-year campaign ably displaced Sandino’s rebels from the populated areas of Nicaragua “to achieve [a] stable and secure environment needed for effective governance, essential services, and economic development.”45 Historic parallels are easily made between the Nicaraguan Campaign and the campaigns conducted in Iraq and Afghanistan. The lessons herein derived are enduring and necessary for similar types of campaigns to be fought in the future. First, the “foreign face,” American in this case, often present initially in an occupation can socially impair the views of the indigenous populace.46 Nicaraguan officials, as well as their U.S. counterparts, were eager to establish a nonpartisan, indigenous national guard force capable of providing local and regional security during government development. Rapidly placing national and regional matters back into the hands of the Nicaraguans was integral to not only assisting the United States in drawing down its forces in Nicaragua, but also to legitimizing Nicaraguan sovereignty.

Second, Marine aviation was indispensable, expanded ground-based operations, and formed a premier fight force—the MAGTF. Combining aerial reconnaissance, ground attack, and air transport operations with the ground scheme of maneuver proved that, by integrating ground and air operations, Marines were more effective in locating, disrupting, and defeating Sandino’s rebels—more effective than the conduct of each element operating separately.47 All in all, the functions of Marine aviation in Nicaragua were of primary importance to operations where delivering reinforcing troops, supplies, and fires more quickly than could be accomplished in movements over the land, proving the worth of not only Marine aviation but the relevance and power of the MAGTF in combat.

Though the campaign conducted in Nicaragua from 1927 to 1933 failed to bring lasting peace to Nicaragua, the Marines and sailors successfully prevented a civil war and provided a stable environment by which the Nicaraguan government grew its military and economy. For the Marine Corps, the campaign proved that “Marine aviators and infantrymen [could function] smoothly as a unified team.”48 Thus, the MAGTF was conceived and the resulting synergistic mechanisms of the new air-ground team provided the basis for how the MAGTF would fight in future wars.

• 1775 •

Endnotes

- Richard F. Grimmett, Instances of Use of United States Armed Forces Abroad, 1798–2009 (Washington, DC: Congressional Research Service, January 2010), 2–10.

- Bernard C. Nalty, The United States Marines in Nicaragua (Washington, DC: Historical Branch, G-3 Division, Headquarters Marine Corps, 1968), 1–4.

- Ibid., 4, 34.

- Lester D. Langley, The Banana Wars: An Inner History of American Empire, 1900–1934 (Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 1983), 53.

- Nalty, United State Marines in Nicaragua, 1; and Neill W. Macaulay, “Sandino and the Marines: Guerrilla Warfare in Nicaragua, 1927–1933” (dissertation, University of Texas, 1965), 1.

- Federal Republic of Central America consisted of present-day states of Nicaragua, Guatemala, Honduras, El Salvador, and Costa Rica. See Nalty, United States Marines in Nicaragua, 1.

- Bryce Wood, The Making of the Good Neighbor Policy (New York: Columbia University Press, 1961), 15; and Macaulay, “Sandino and the Marines,” 10.

- Nalty, United States Marines in Nicaragua, 3–5.

- Ibid., 13–14.

- Maj Taylor White, “U.S. Marine Corps Operations in Nicaragua from 1927 to 1933” (dissertation, Marine Corps University, Command and Staff College, 2011), 7.

- Ibid., 14–16.

- Ibid., 34.

- Ross E. Rowell, “Annual Report of Aircraft Squadrons, Second Brigade, U.S. Marine Corps, July 1, 1927 to June 20, 1928,” Marine Corps Gazette 13, no. 4 (December 1928): 248.

- Ibid., 252–56.

- Brent Leigh Gravatt, “The Marines and the Guardia Nacional de Nicaragua: 1927–1932” (dissertation, Duke University, 1973), 79.

- Langley, Banana Wars, 195; and Counterinsurgency, FM 3-24/MCWP 3-33.5 (Washington, DC: Department of the Army, January 2006), 5-4.

- LtCol Charles Neimeyer, USMC (Ret), “Combat in Nicaragua,” Marine Corps Gazette 92, no. 4 (April 2008): 74. The 11th Marine Regiment arrived in January 1928.

- Gravatt, “The Marines and the Guardia Nacional de Nicaragua,” 79–81.

- Ibid., 86–101.

- Dana Gardner Munro, The United States and the Caribbean Republics: 1921–1933 (New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 1974), 227.

- Gravatt, “The Marines and the Guardia Nacional de Nicaragua,” 60–63. The Guardia Nacional de Nicaragua soldiers volunteered for three-year enlistments. During the period from October 1927 to September 1932, the Guardia Nacional enlisted on average about 1,000 Nicaraguans per year as the enlisted force level rose from 1,633 enlisted men to almost 2,300 near the end of the campaign. See table 12 in Gravatt, 109.

- Ibid., 106.

- Ibid., 107.

- Ibid., 111–12.

- Maj Julian C. Smith et al., A Review of the Organization and Operations of the Guardia National de Nicaragua (Washington, DC: Headquarters Marine Corps, 1933), 103–6.

- Gravatt, Marines and the Guardia Nacional de Nicaragua, 83–92.

- Counterinsurgency, 5-5.

- Gravatt, “The Marines and the Guardia Nacional de Nicaragua,” 83.

- Ibid., 91–92.

- Counterinsurgency, 5-5, 5-6.

- Gravatt, “The Marines and the Guardia Nacional de Nicaragua,” 86.

- Ibid., 91.

- Nalty, United States Marines in Nicaragua, 34.

- Ibid.

- Rowell, “Annual Report of Aircraft Squadrons,” 248.

- Ibid., 249.

- Ibid., 249–50.

- Ibid., 252.

- Lt Col Edward C. Johnson, Marine Corps Aviation: The Early Years, 1912–1940 (Washington, DC: History and Museums Division, Headquarters Marine Corps, 1977), 57.

- Capt G. D. Hatfield, “Attack on Ocotal,” The Sandino Rebellion, Patrol and Combat Reports, July 1927, 3, http://www.sandinorebellion.com/pc- docs/1927/PC270716-Hatfield.html. “The air attack was the deciding factor in our favor, for almost immediately the firing slackened and troops began to withdraw.” See Rowell, “Annual Report of Aircraft Squadrons,” 254–55.

- Rowell, “Annual Report of Aircraft Squadrons,” 252.

- Ibid.

- Johnson, Marine Corps Aviation, 57.

- Headquarters, United States Marine Corps, “Nicaraguan Aviation Report: Brief History of the Aircraft Squadrons, 2d Brigade, Marines Nicaragua” (1 March 1927–10 December 1932).

- Counterinsurgency, 5-3.

- Smith, A Review of the Organization and Operations of the Guardia National de Nicaragua, 50.

- Rowell, “Annual Report of Aircraft Squadrons,” 248.

- Nalty, United States Marines in Nicaragua, 34.