PRINTER FRIENDLY PDF

EPUB

AUDIOBOOK

In the contest for American votes, a candidate’s bluster on the campaign trail can have unintended, yet far-reaching consequences. Franklin D. Roosevelt learned this lesson the hard way during the 1920 presidential campaign, when his remarks about the “little republics” of Central America and the Caribbean raised public furor over the U.S. intervention and Marine Corps misconduct in Santo Domingo (now Dominican Republic) and Haiti. Touting his experience as assistant secretary of the Navy, the Democratic vice presidential nominee boasted before a group of Montana voters: “You know I have had something to do with the running of a couple of little republics. The facts are that I wrote Haiti’s Constitution myself, and, if I do say it, I think it’s a pretty good Constitution.”1 Roosevelt further fanned the flames of opposition when he insinuated that President Woodrow Wilson’s administration could compel several Latin American republics to support U.S. initiatives in the newly formed League of Nations. “We are in the very true sense the big brother of these little republics,” he explained. “Does anyone suppose that the vote of Cuba, Haiti, San Domingo [sic], Nicaragua and of the other Central American states would be cast differently from the vote of the United States?”2

Popular outcry was both swift and strong. Roosevelt’s comments elicited caustic responses from both liberal advocates for national self-determination and conservative opponents of Wilsonian internationalism. Senator Warren G. Harding, the Republican nominee for president, capitalized on the growing furor by staking his own foreign policy in Dominican soil. Speaking before an Indiana delegation of voters in late August 1920, Harding condemned current U.S. military actions in the Caribbean as “unwarranted interference” that had not only “made enemies of those who should be our friends, but have rightfully discredited our country as a trusted neighbor.” If elected president, he promised “not [to] empower an assistant secretary of the navy to draft a constitution for helpless neighbors in the West Indies and jam it down their throats at the point of bayonets borne by the United States marines.”3

In denouncing the Wilson administration’s Caribbean policy and the activities of Roosevelt, in particular, Harding effectively pledged to bring an end to the military occupation in the Dominican Republic.4 It would take nearly four years to fulfill this promise. Harding’s victory in the general election signaled the final phase of the American intervention, which involved intense public scrutiny, difficult treaty negotiations, and sweeping internal reforms. In view of this contentious resolution, the original rationale and aims of the U.S. intervention remain essential to understanding how the military occupation in the Dominican Republic evolved from a celebrated campaign, demonstrating the tactical efficiency of the U.S. Marine Corps and producing three Medal of Honor recipients, to a misguided counterinsurgency operation and military regime embodying imperialist overreach in U.S. foreign affairs. To be sure, the 1920 presidential election reflected a pronounced shift in American public opinion since the first Marines landed in the Dominican Republic four years earlier. The campaign also demonstrated shifting political terrain—both internationally and locally within the Dominican Republic—that gave rise to increasingly harsh Marine Corps enforcement of U.S. authority against nationalist resistance. Tracking the diplomatic motivation, military invasion, and counterinsurgency efforts of Marines in the Dominican Republic elucidates the changing circumstances that not only shaped public perception of the Marine Corps throughout the occupation but also compelled reform measures in both training and operations to facilitate a peaceful and effective withdrawal.

Protecting “America’s Lake”

In the years leading up to World War I, the financial insolvency and political disorder in Central America and the Caribbean appeared dangerous to U.S. national security. Although the United States had been active in Caribbean affairs throughout the nineteenth century, the emergence of navalism, a policy which emphasized territorial and naval expansion as being indispensable to national defense, spurred U.S. officials to direct substantial attention and resources to the region in the first decades of the twentieth century.5 As naval historian Alfred Thayer Mahan argued in his seminal book The Influence of Sea Power upon History: 1660–1783 (1890), success in naval warfare required a large fleet of warships ready for rapid deployment in fighting decisive battles. The completion of the Panama Canal in 1914 endowed the U.S. Navy with a strategic advantage over other naval fleets, since the United States could quickly transfer ships between the Pacific and Atlantic Oceans and between the West and East Coasts. The desire to protect the isthmian canal, as well as the sea-lanes around it, renewed U.S. interest in the Monroe Doctrine and occasioned frequent and more intensive military interventions in the name of national defense.

The Venezuelan Claims Crisis of 1902–3 distilled American fears about European intervention in the Western Hemisphere. Over the previous century, European investors had made substantial loans to various Latin American republics. Although the national governments receiving these loans were notoriously unstable and often borrowed funds for the explicit purpose of defeating revolution, common practice dictated that each regime must honor the debts of its predecessors. Venezuelan President Cipriano Castro, however, refused to make payments following a civil war. In retaliation, Germany, Great Britain, and Italy initiated a punitive blockade at Caracas, shelled a coastal fort, and threatened seizure of Venezuelan customs houses. Alarmed by European aggression near the Canal Zone, President Theodore Roosevelt sent about 50 ships—a large portion of the U.S. Navy at that time—to perform “training maneuvers” in the southern Caribbean. This transparent show of strength reinforced U.S. demands that the dispute be settled through international arbitration. Although The Hague would later rule in favor of the European powers, Roosevelt made clear U.S. intolerance for foreign interference in the American republics.6

The threat of a similar crisis in the Dominican Republic prompted Roosevelt to formalize U.S. foreign policy in hemispheric affairs.7 On 6 December 1904, the president unveiled a policy that has since become known as the “Roosevelt Corollary to the Monroe Doctrine.” Arguing that European efforts to enforce Latin American debt repayment necessarily violated the Monroe Doctrine, he announced that the United States would need to ensure the political and financial stability of its sister republics. The president and other American policymakers believed Latin Americans were incapable of preserving law and order and that the United States, a more “civilized” power, must impose financial oversight to guarantee timely remittance and to protect foreign lives and property.8

With transatlantic tensions hanging in the balance, the Dominican Republic served as a testing ground for the first practical application of the Roosevelt Corollary. As Roosevelt brashly proclaimed, “I have about the same desire to annex it as a gorged boa constrictor might have to swallow a porcupine wrong-end-to.”9 Nevertheless, the perceived critical importance of the island to American national security necessitated U.S. involvement to preserve order and reduce foreign debts, both objectives deemed essential in preventing European military presence in the region. In 1905, the U.S. State Department worked out a series of agreements that placed the Dominican customs service under American management. Although the U.S. Senate would delay ratifying the treaty until 1907, Roosevelt implemented the customs receivership immediately by executive fiat.10 The initial results of the U.S.-imposed customs receivership in the Dominican Republic were encouraging. Financial experts arranged for new loans with American lenders for debt consolidation and a lower interest rate, and U.S. officials took charge of customs revenues, collecting duties at Dominican ports and dividing the proceeds between foreign bondholders and the incumbent regime. Furthermore, the popularity and stability of the new Dominican president, Ramón Cáceres, permitted the administration to direct attention toward modernization and economic development in the country, which State Department officials attributed to the beneficial influence of U.S. oversight. Consequently, the Dominican customs receivership served as the cornerstone of President William H. Taft’s foreign relations policy. Known popularly as “dollar diplomacy,” Taft emphasized economic influence as a paramount consideration in diplomatic affairs and pledged to use bankers rather than battleships to influence international stability.11 Nevertheless, when such efforts failed to secure desired results, both Taft and his successor, President Woodrow Wilson, resorted to threats of military force, or as historian Max Boot has described it, “the brass knuckles hidden beneath the velvet glove.”12

Disorder and Diplomacy, 1911–16

The assassination of President Cáceres in November 1911 shattered the relative peace and economic prosperity of the Dominican Republic and ushered in a new era of transitory regimes and revolutionary violence. The near-constant disorder reflected a longstanding political feud between horacistas, followers of General Horacio Vásquez, and jimenistas, partisans of Juan Isidro Jiménez, as well as the growing strength of such regional leaders as General Desiderio Arias of Santiago. Without a dependable army or police force to buttress the central government, Dominican presidents remained chronically vulnerable to coups and civil wars.

Between 1911 and 1916, U.S. officials intervened in Dominican affairs with increasing frequency to compel reform measures that would ostensibly establish a stable, freely elected, and pro-American government. Employing both diplomatic pressure and military might, the United States regularly sent warships to observe or make shows of force against the Dominican government, to threaten revolutionaries, or to protect the lives and property of American citizens. Despite such heavy-handed tactics on the part of the United States, domestic political turmoil persisted in the Dominican Republic, resulting in eight separate administrations in Santo Domingo in less than five years. Rebellion flourished especially in the interior valleys, north coast, and rugged frontiers where local dictators, or caudillos, held sway. The warring political factions quickly exhausted the national treasury, and the country assumed additional debt trying to suppress rebellion, circumstances the United States considered in direct violation of its 1907 treaty with the republic. Moreover, this relapse into political volatility and financial insolvency inflamed U.S. fears of European intervention. German designs on the Americas, in particular, seemed to pose a very real threat. The German Navy, under the command of Admiral Alfred von Tirpitz, schemed to acquire land and establish military bases in the Caribbean, Central America, and Mexico in an effort to disrupt American use of the Panama Canal and potentially stage a direct strike against the United States. Furthermore, German influence and manipulation of revolutionary unrest, especially in Mexico, aimed to divert U.S. attention and resources in a protracted and costly conflict far from Europe.13 These efforts culminated in the infamous Zimmerman Telegram, which outlined a plot to produce a German-Mexican-Japanese alliance and helped draw the United States into World War I.

The State Department, which had become increasingly hostile in its interactions with the Dominican government, began to consider seriously the possibility of full-scale military intervention and the imposition of U.S. demands—a solution it had already implemented in Haiti starting in the summer of 1915. In November, William W. Russell, the newly appointed American minister and longtime advocate of intervention, arrived in Santo Domingo with an ultimatum. Under the terms of this agreement, the Dominican Republic would be obligated to accept the appointment of U.S. financial advisors and the formation of U.S.-controlled constabularies. The current president, Juan Isidro Jiménez, refused the proposed treaty, which would have severely curtailed Dominican sovereignty. Even so, his political enemies pointed to American overtures to damage his prestige and bolster support for their revolutionary efforts.

Civil war again erupted in the Dominican Republic following a misguided attempt by Jiménez to disenfranchise his political rivals. In April 1916, the president ordered the arrest of several insubordinate officers, chief among them his minister of war, General Desiderio Arias. Tall, thin, and of mixed-race heritage, Arias was a powerful, charismatic caudillo with a large following in the northwestern province of Monte Cristi near the Haitian border. He represented the most infertile and impoverished region in the country but, unlike other caudillos, banned his troops from stealing food from the poor. Rising from humble origins himself, Arias attracted a devoted following among darker-skinned peasants, soldiers, and the urban poor. By early May, the popular and politically influential leader had persuaded the Dominican congress to begin impeachment proceedings against Jiménez. Arias then seized control of the capital and declared open revolt. With this action, the United States sent Marines to Santo Domingo to protect the American legation and to assist the Jiménez regime.

Armed Intervention

On 2 May 1916, two warships carrying a small force of Marines arrived in the Dominican Republic.14 In the eyes of Washington politicians, Arias had raised a rebellion against a properly elected president. In addition, U.S. policymakers viewed Arias as being pro-German and a conduit of arms to Haitian cacos, or guerrilla fighters, then resisting American military rule on the other side of the island.15 Humanitarian paternalism and racism further informed the State Department’s decision to intervene militarily in the Dominican Republic. Ill-informed on political and social conditions in the republic, American officials incorrectly attributed the endemic violence and debt to corrupt local leadership.16 The State Department thus aimed to stabilize events in the Dominican Republic by preserving the incumbent administration against attempts to usurp power by force.

The United States concluded that Jiménez could not dislodge Arias from the capital without American assistance. The rebel leader had marshaled hundreds of civilian irregulars, armed with rifles from government arsenals and around 250 Dominican soldiers who had defected to his side. Captain Frederic M. Wise, who commanded the provisional battalion of Marines in Santo Domingo, described the situation, “every male in town even boys were armed easily making over a thousand rifles, with five (5) gatlings, unlimited ammunition . . . plenty of [artillery]” and “gunners who knew how to use it.”17 Jiménez’s small army, by contrast, numbered around 800 soldiers and had very little ammunition, fewer than 20 rounds per person. Minister Russell pressured Jiménez to request a landing of U.S. Marines. Exiled from the capital, the president first accepted but later rejected American assistance, explaining that his authority would diminish if “regained with foreign bullets.”18 As an alternative to U.S. armed intervention, Jiménez asked Russell and Wise to meet with Arias and negotiate a peaceful surrender. The Americans agreed on the condition that, if Arias refused, Jiménez would consent to a combined assault with Dominican and U.S. forces to regain the capital.

Arias and his followers rejected the deposed president’s détente. Wise returned to camp and began making preparations to disarm the rebels by force, but Jiménez balked at the attack. “I can never consent to attacking my own people,” he declared.19 Wise, incensed by this response, told the Dominican president that American prestige was on the line and that if he did not want U.S. military aid he should resign his office. After some vacillation, Jiménez agreed. A secretary drew up the paperwork, and the president resigned on the spot.

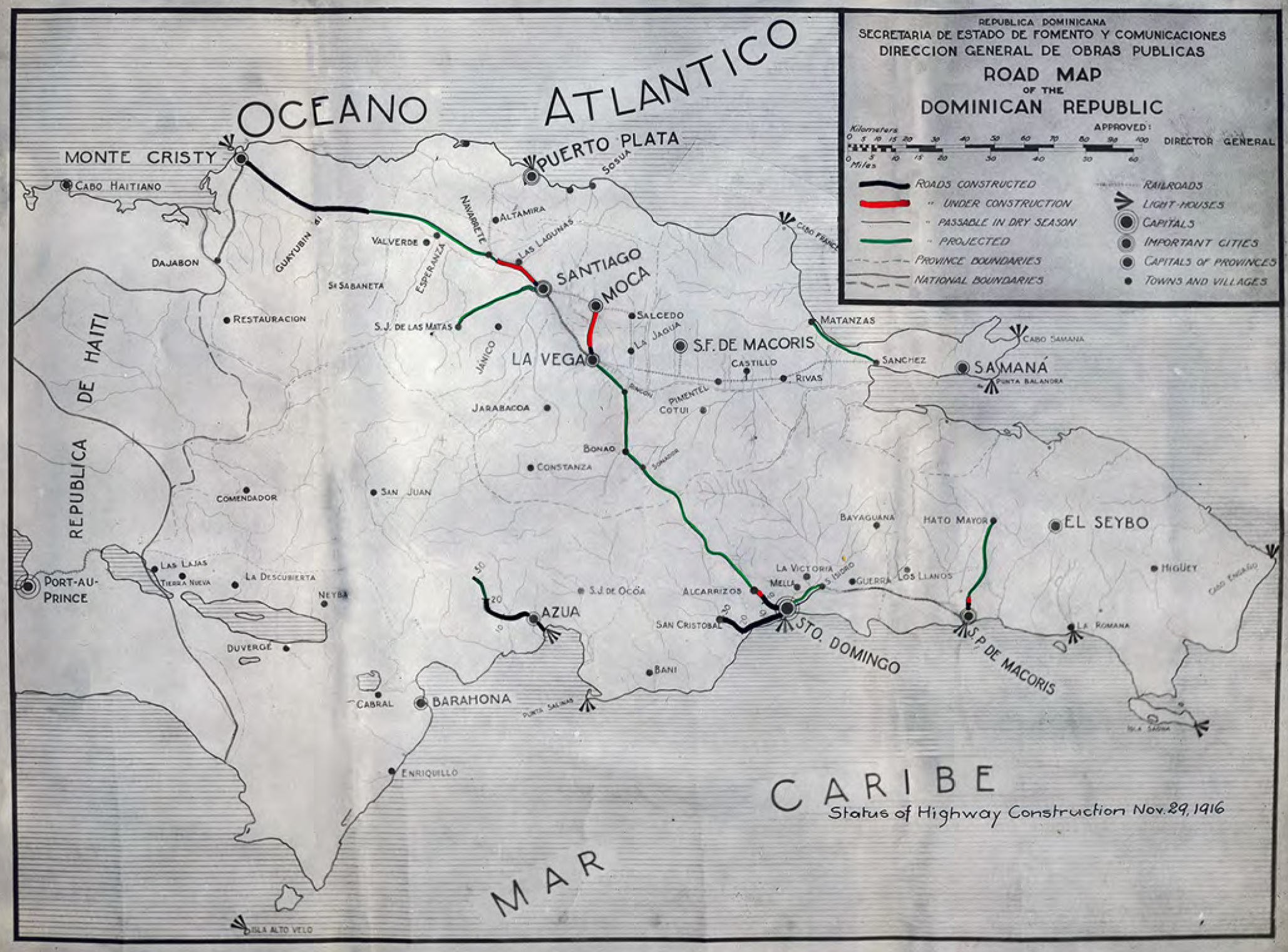

Map of Dominican Republic, November 1916. Dominican Republic Papers, HIRB, MCHD

Now in the position of trying to uphold an administration that had ceased to exist, the United States was nevertheless determined to quash the revolution and reinstate a constitutional government. On 13 May, Rear Admiral William B. Caperton, commander of the U.S. Navy’s Cruiser Squadron, Atlantic Fleet, issued an ultimatum signed by himself and Russell demanding that Arias disband the rebel army by 0600 on 15 May or face a full-scale American attack. As the U.S. officers awaited an answer, Arias defiantly hoisted Dominican flags rather than white flags as anticipated for surrender. Captain Wise and Major Newt H. Hall, commander of the 4th and 5th Companies recently arrived from Haiti and a detachment of the 24th Company from Guantánamo Bay, made plans for the forcible disarmament of the revolutionaries, while U.S. warships proceeded to San Pedro de Macorís, Sánchez, Puerto Plata, and other important Dominican ports.20 On the appointed date, the Marines marched on the rebel-held capital city. Anticipating armed resistance on every block, they instead discovered that Arias had evaded military confrontation by evacuating his troops under the cover of night.

The Marine Corps took control of Santo Domingo and made the city its base of operations ashore.21 Outside the capital, authority remained in the hands of local governors and military chieftains who operated independently of the central government. In addition, Arias claimed to still hold the legitimate power of congress. Having reestablished headquarters at Santiago, he refuted the partisan revolutionary title assigned to him by Jiménez and the United States. His flag belonged to the Dominican people, he proclaimed.22 Russell refused to recognize Arias as the rightful executive chief and instead elevated Jiménez’s remaining four cabinet members to the status of an interim “Council of Ministers” to carry on the business of state. Worried that Arias or one of his followers would be elected to the presidency if the Dominican congress were allowed a vote, Russell worked closely with Caperton to block congressional action while seeking a suitable alternative.23 While this strategy had worked in Haiti, Dominican politicians refused to give advance assurances of U.S. cooperation. “I have never seen such hatred displayed by one people for another as I notice and feel here,” Caperton confessed. “We positively have not a friend in the land.”24 Encountering near-universal hostility to U.S. governance, the commander feared a national uprising and called for reinforcements to secure the country’s main coastal towns and disperse Arias’s army in the Cibao Valley.25

The March on Santiago

Arias had retreated 85 miles inland to Santiago de los Caballeros (Santiago), located in the northern agricultural valley of Cibao, where the distance to the sea precluded bombardment by a man-of-war or amphibious landing force.26 RAdm Caperton ordered Colonel Joseph H. Pendleton, the commanding officer of the 4th Regiment affectionately known as “Uncle Joe,” to proceed against Arias’s stronghold in the northern interior. Pendleton devised a plan in which two columns of Marines would converge on Santiago from ports on the northern coast, since the country contained no roads that could accommodate large attack forces moving from the south. One column, commanded by Captain Eugene P. Fortson and subsequently Major Hiram I. Bearss, would follow a railroad inland from Puerto Plata, while the other, led by Pendleton, would march by road from Monte Cristi. The two forces would convene in Navarette, a village located 18 miles south of Santiago, for a full-scale drive on the objective.

Before the operation began, Pendleton defined the Marines’ mission in the Dominican Republic and established guidelines for appropriate troop conduct. “[O]ur work in this country is not one of invasion,” he announced to his men. Clarifying that their aim was to restore order, protect life and property, and support the constitutional government, he exhorted his fellow officers and enlisted men to “realize that we are not in an enemy’s country, though many of the inhabitants may be inimical to us.” Pendleton instructed his audience to treat the Dominican people with courtesy and dignity so as “to inspire confidence among the people in the honesty of our intentions” and to avoid generating antagonism and perceptions of an armed invasion.27

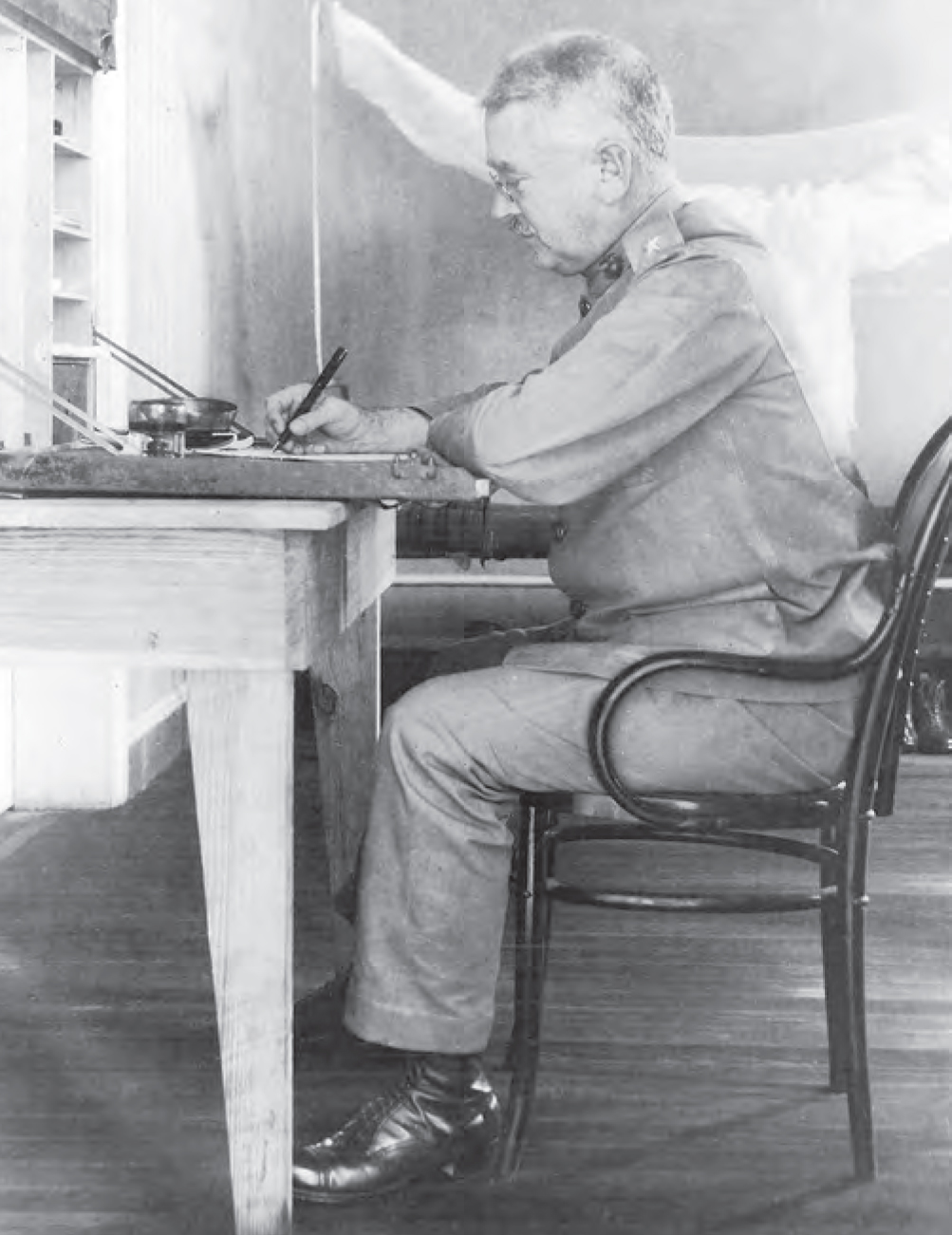

Col Joseph Pendleton seated at his desk in Santiago, Dominican Republic, 1916. Dominican Republic photo, HIRB, MCHD

In the early morning hours of 26 June 1916, Pendleton’s column embarked on its 75-mile journey inland. The Monte Cristi force, consisting of the 4th Regiment and some artillery, had a greater distance to travel and would operate as a “flying column” without communications or supplies once it passed the midpoint of its assigned route. Consequently, a two-mile-long supply train of trucks, automobiles, mule carts, pack mules, and a caterpillar tractor followed in the wake of the main column. As Sergeant Major Thomas F. Carney recalled, “no stranger array ever moved at the command of one man.”28 The column proceeded slowly along the main road. The Dominican insurgents had sabotaged bridges and railroad tracks on their retreat to impede the Americans’ progress toward Santiago. The column’s extensive supply included construction materials, so the Marines made repairs as necessary. At one ravine, the Dominicans had destroyed a 300-foot bridge, so the Marines crossed the ravine using an improvised trestle. Although constructed in just three hours, the makeshift bridge permitted the column to transport heavy guns and trucks across the ravine “in perfect safety.”29 The resourceful troops nevertheless confronted an array of obstacles as they trudged across the rough terrain. Forcing the Marines to walk secured tactical advantages for the insurgents by delaying the troops’ advance and leaving them vulnerable to Dominican attack.

The northern resistance began at Las Trencheras, a defensive outcropping where insurgents had built a defensive network of trenches. The widely known site had long been held by revolutionary armies; because government troops had never successfully captured the ridge, Dominicans considered it impenetrable.30 As Pendleton’s column approached, Marine officers watched the armed insurgents’ movements through their field glasses and judged artillery to be the best means to counterattack the entrenched position. The next morning, Captain Chandler Campbell’s 13th and 29th Companies hauled the battery into position on a ridge overlooking the road. The artillery fired 40 rounds while Captain Arthur T. Marix’s 1st Battalion, supported by Major Melville J. Shaw’s 2d Battalion, advanced slowly through the jungle foliage. The insurgents, impervious to the artillery barrage, concentrated heavy fire on the closing ranks.31 Sergeant Major Carney reported that “the whole hillside was enshrouded in a pall of smoke through which the flashes of rifles constantly stabbed like light[n]ing through a cloud.”32 Suddenly, he perceived through the smoke a long line of bayonets gleaming in the morning sun. Pendleton’s chief of staff, Major Robert H. Dunlap, sounded his whistle, and with a wild cheer the Marine infantry units charged up the slope. The supporting artillery and machine gun platoon continued to suppress enemy fire, allowing the Marines to perform quick rushes and rout the insurgents from the trenches. Within 45 minutes, they had seized the dominating ridge and driven the rebels into retreat.33

13th Company, 4th Regiment, traveling with Pendleton’s column on the road from Monte Cristi to Santiago, 26 June–6 July 1916. Dominican Republic photo 521541, HIRB, MCHD

On 3 July 1916, Pendleton’s column again encountered resistance at Guayacanas, where 80 Dominicans had dug defensive trenches and constructed a roadblock of felled trees. Camouflaged by the removal of excavated earth, the enemy’s position was so well concealed that the Marines had difficulty locating it; however, Marine patrols had earlier captured a prisoner who provided accurate information about terrain and size of the Dominican force. Artillery proved ineffective, because Marine gunners could not find an adequate position to stage their weapons. In addition, the ground in front of the defensive line had been cleared of all vegetation, providing the enemy an unobstructed line of fire.34 Without any tactical alternative, Marines of the machine-gun platoon carried their Benet-Mercier light machine guns within a few hundred yards of the trenches and opened fire. The insurgents countered the automatic weapons with single-shot rifle fire, yet the assault was so intense that several men were shot and killed at their guns within minutes.35 Pendleton, disregarding the advice of his chief of staff to remain with the artillery, advanced to the firing line. He calmly surveyed the enemy’s position and issued instructions for an enveloping movement. Although a direct frontal attack would almost certainly fail, he correctly predicted that small parties from the 1st and 2d Battalions could approach through the jungle on the right and left sides and thereby secure a protected position from which to enfilade the enemy. Amidst the din of automatic weapons, the Marines charged from their flanked positions. In the center of the Marine advance, where action was thickest, First Sergeant Roswell Winans was working a jam-prone M1895 Colt-Browning machine gun from an exposed position. “They seemed to be just missing me,” he recalled. “I don’t know how the other men felt, but I expected to be shot any minute and just wanted to do as much damage as possible to the enemy before cashing in.”36 When the last round jammed in his weapon, Winans calmly inspected the gun, returned it to working order, and resumed firing for the remainder of the engagement.37 Meanwhile, Corporal Joseph A. Glowin set up his Benet-Mercier behind a fallen log and began firing on the enemy. Although he was wounded twice, he continued his assault until other Marines forcibly dragged him from the front line to safety. For these exploits, Winans and Glowin became the first men in the 4th Regiment to receive Medals of Honor.

Three-inch field piece in full recoil at Santiago, 1916 Dominican Republic photo 521542, HIRB, MCHD

Having successfully forced the entrenched snipers to retreat, the Marines loaded their wounded into the wagon train and resumed the drive toward Navarette, where the column joined the smaller Puerto Plata contingent, consisting of the 4th and 9th Companies as well as Marine detachments from the battleships USS Rhode Island (BB 17) and USS New Jersey (BB 16).38 Under Pendleton’s orders, the force had proceeded from Puerto Plata, a town about 80 miles east of Monte Cristi on the north coast. Although the Marines had traversed a shorter distance than Pendleton’s crew, the column followed a destroyed railroad course that was inaccessible to a supply train. Tasked with securing and reopening the railroad, thereby reconnecting Santiago with the port city and establishing a line of supply for the combined attack force, the Marines traveled as far as they could in a train of four boxcars pulled by a dilapidated locomotive, which pushed a flatcar carrying a three-inch artillery piece.39 On 29 June, Bearss’s contingent encountered a Dominican force at La Cumbre, a critical position near Alta Mira where the railroad track passed through a 300-yard tunnel. The 4th Company scaled a nearby mountain trail and signaled the enemy presence approximately 3,000 yards away. Captain Fortson unloaded his 3-inch gun and began shelling a shack overlooking the rebel lines. On the ground, a combination of frontal and flank attacks forced the insurgents to retreat. When the Dominicans quit their position and ran for the tunnel, Bearss gave chase with a detachment of 60 men. The major, furiously pumping a handcar, rushed into the dark tunnel entrance despite the possibility of ambush or worse. Bearss and his men emerged safely from the railroad corridor to watch the rebels hasten toward Santiago.40

The reunion of the columns at Navarette set up the Marines for the final stage of the campaign: the capture of Santiago. Before the troops even made camp at the rendezvous point, a delegation approached and requested an audience with the American commander to negotiate peace terms. Pendleton, seated on an upturned bucket, met with the Dominicans in the shade of a mango tree.41 With the insurgents decimated and demoralized following three decisive but lopsided battles, they assured Pendleton that the revolutionaries’ desire for war was gone. The peace commission negotiated terms for surrender, including a pardon for their leader, Arias. The agreement took effect on 5 July 1916, and the 4th Regiment peacefully entered the city of Santiago the following day.

With 2,000 troops in the field, Caperton had reasonably firm control of the nation. This military success did not resolve the State Department’s desire for a pro-American successor regime, however. Russell used financial leverage and threatened further military action to dissuade the Dominican congress from electing anyone unwilling to support U.S. demands. On 25 July, the Dominicans thwarted Russell’s coercive maneuvers and elected Dr. Francisco Henríquez y Carvajal as provisional president. When Henríquez arrived in the capital, the American minister refused to recognize the election as valid until he submitted to U.S. conditions. Henríquez defended the Dominican right to manage its own affairs, so Russell impounded all government funds. The ensuing political stalemate lasted until November, when the State Department declared the establishment of a military government in the Dominican Republic.42 Over the next eight years, the Marine Corps acted as an army of occupation supporting a variable and sometimes oppressive American regime.

The Army of Occupation, 1917–20

In the United States, press coverage of events in the Dominican Republic touted American military operations for restoring peace on the troubled island. Despite the challenges of unmapped terrain, and sabotaged roads and railroads, the Marines had demonstrated tactical skill and professional discipline. On 5 November 1916, the Washington Post announced that First Sergeant Winans and Corporal Glowin had been awarded the Medal of Honor for “extraordinary valor” shown during the battle at Guayacanas.43 Furthermore, the efficiency and flexibility with which the force had subdued the Dominican Republic helped to demonstrate the usefulness of the Marine Corps as an elite fighting force ready for deployment on behalf of American foreign affairs. Walker W. Vick, the former receiver general for Dominican customs, told the New York Times that he regretted only that the United States had not intervened sooner.44 This high regard represented a welcome change for the Marine Corps, whose very existence had come under attack in the U.S. Congress less than a decade before.

In the Dominican Republic, by contrast, public opinion of the Marine Corps deteriorated rapidly. The Marines’ mission, so clearly defined by Pendleton during the initial campaign, grew murky after the capture of Santiago and declaration of military government. Whereas U.S. Marines and sailors initially had performed brief land excursions to quell the revolution, their operations in the Dominican Republic evolved to encompass long-term occupation and the management of internal political affairs. Consequently, the rules of engagement changed as well. The initial battles in the Dominican Republic had established a tactical pattern of attack-and-response that would continue to characterize much of the fighting in the coming years; however, several factors distinguished the drive against Santiago and later counterinsurgency efforts. First, the campaign had primarily involved conventional warfare. Although the Marines encountered repeated assaults from Dominicans in entrenched positions, American commanders employed established battle tactics, such as advance reconnaissance, supporting artillery fire, frontal and flank advances, and quick rushes to rout the enemy’s defensive line. The establishment of an American military government in November 1916 effectively converted the Marine Corps to an occupying police force, directed toward the enforcement of official decrees.45 Tasked with maintaining order, the troops engaged in counterinsurgency operations for which they were neither prepared nor trained to handle. Second, frequent personnel changes at all command levels, particularly after U.S. entry in World War I, exacerbated the situation by introducing variable methods, interpretations, and codes of conduct. Finally, the long duration and lack of measurable progress in pacifying an increasingly hostile population resulted, for many Marines, in a breakdown in the distinctions separating civilians from enemy insurgents.

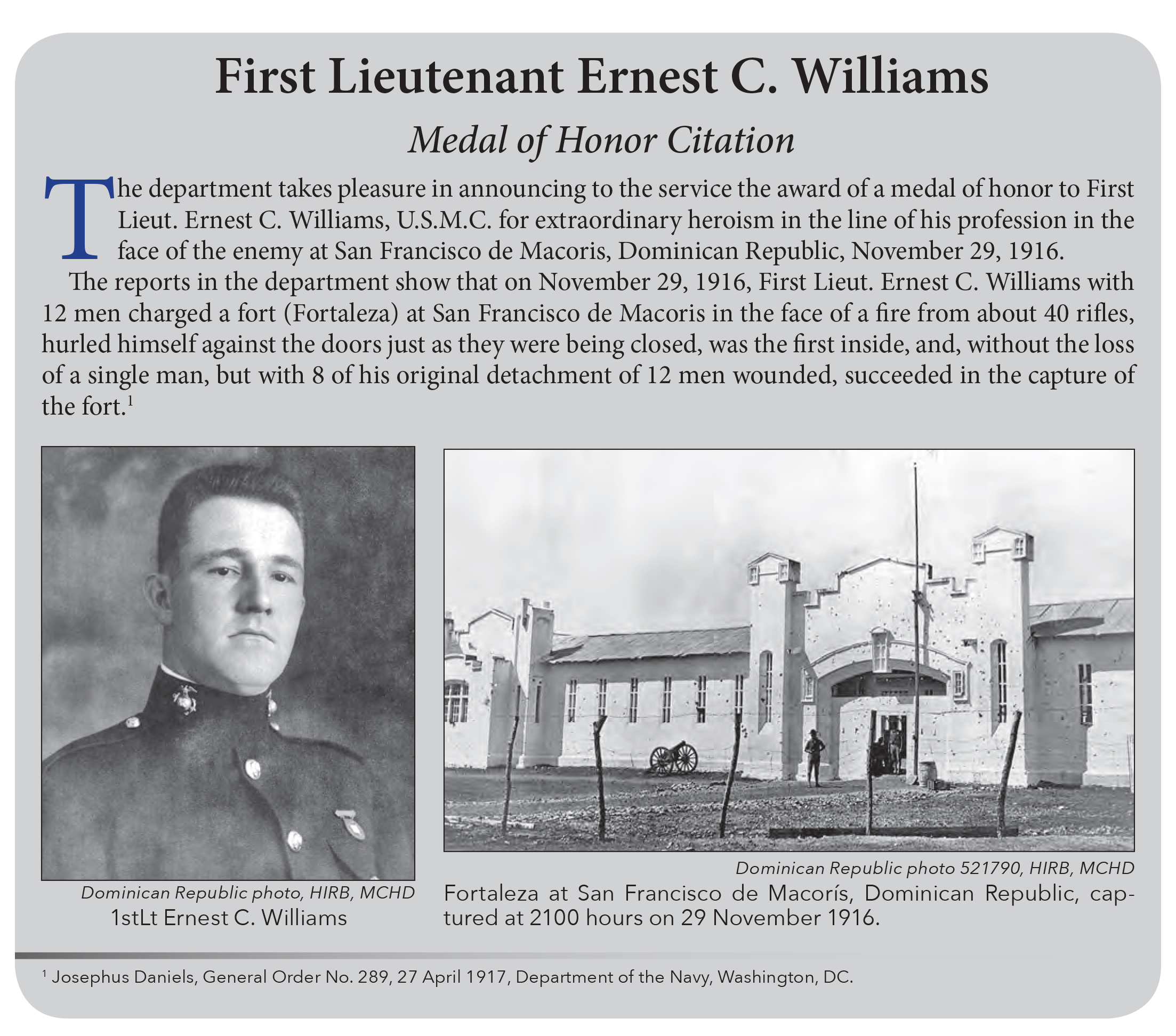

Many Dominicans opposed the American occupation from the start. On the same day that Capt Harry S. Knapp, USN, declared the U.S. military government, First Lieutenant Ernest C. Williams led an assault on the fortaleza at San Francisco de Macorís where Juan Perez, a local governor and supporter of Arias, and his followers had taken a stand and refused to surrender their weapons. As district commander, Williams initially dispatched a message to the governor demanding that he abandon the fort and release his prisoners, but the Dominican allegedly scrawled “Come and get me!” across the ultimatum in reply. In plotting a course of action, Williams conferred with other Marines who argued that the fort would require at least an infantry battalion and artillery battery to take. The district commander, however, determined an alternate course of action. Early the following evening, he led a detachment of 12 Marines from the 31st and 47th Companies in a surprise attack on the fort. Williams and his crew rushed the gate, and a brief but intense battle ensued. Within minutes, the detachment of 13 Marines, 8 of them wounded, had gained control of the fort as well as 100 prisoners confined therein.46 Williams received a Medal of Honor for his actions.

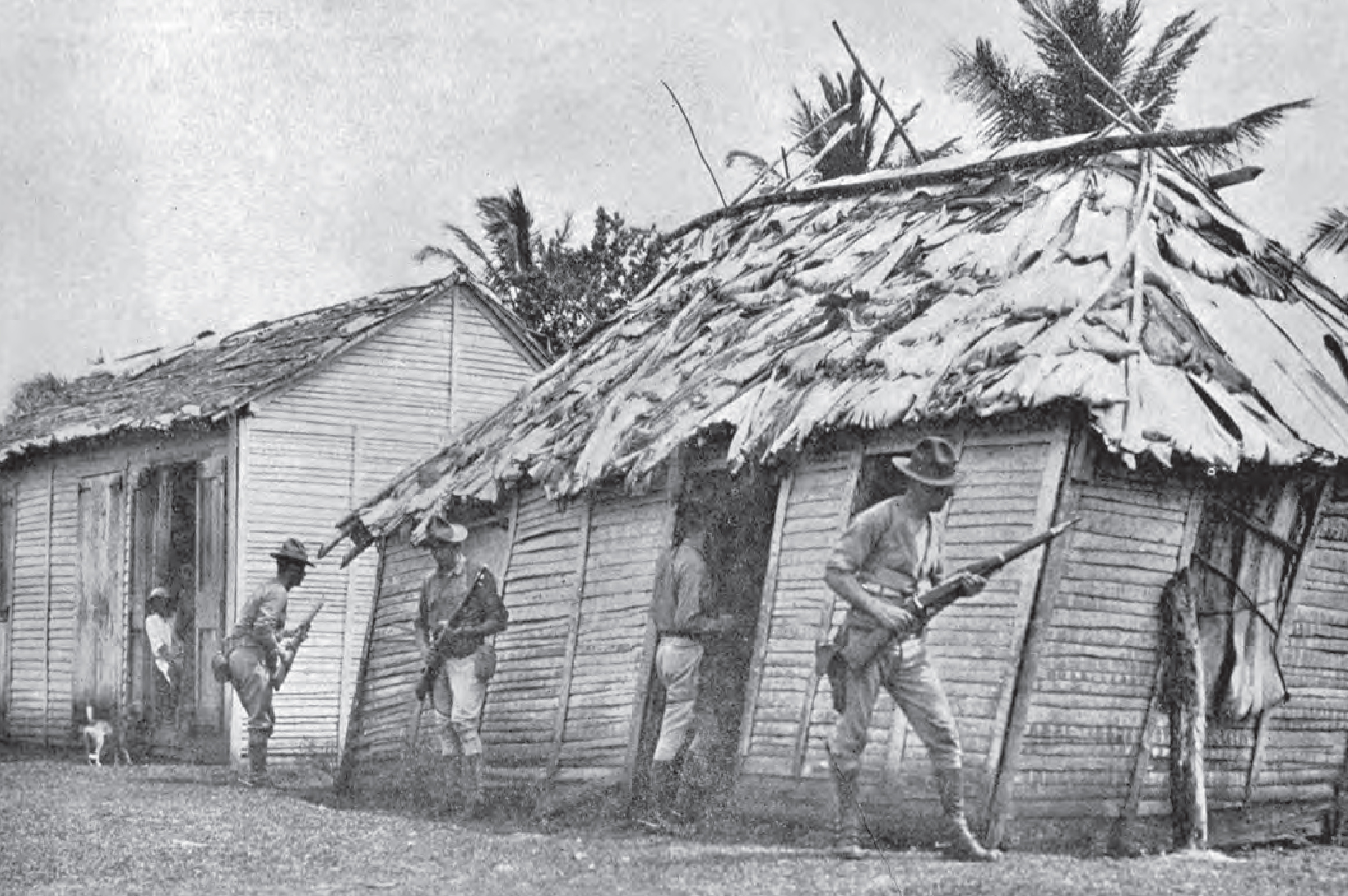

Williams’s successful operation proved the exception rather than the rule in the Dominican campaign. Under the military government, Marine officers acted as district commanders to make sure that martial law was obeyed. Initially, they focused on establishing garrisons in major cities, disarming the civilian population, and defeating known insurgent leaders, whose capture American commanders believed would curtail rebellion; however, the confiscation of weapons and ammunition proved to be a poor measure of Marine effectiveness in stemming the insurgency in a society that placed a high social value on gun ownership.47 Neither officers nor enlisted Marines understood Dominican culture. Few could speak Spanish, and most held then-prevailing racist views that upheld whiteness as the epitome of cultural and intellectual achievement. With a patronizing sense of superiority, many Marines approached their service in the Dominican Republic, a country whose populations Knapp characterized as being “almost all touched with the tarbrush,” as an extended colonialist endeavor to “civilize” the natives.48 Marines habitually employed derogatory slang, referring to Dominicans as “spigs” and “niggers” both in their everyday speech and in their letters and publications.49

U.S. Marines searching Dominican homes for weapons. Dominican Republic photo 5012, HIRB, MCHD

In April 1917, the military government established a local constabulary to assist with the counterinsurgency campaign. The Guardia Nacional Dominicana struggled due to lack of funds and a shortage of competent officers and recruits. As with cabinet positions in the military government, no members of the Dominican elite would submit to a commissioned post in the Guardia Nacional. Consequently, many recruits came from the lower classes. The brigade commander looked to Marines to organize and officer the Guardia until such time as Dominicans could be trained and found competent to fulfill leadership positions, but only 1 of the first 13 American officers was a commissioned Marine officer. Unlike in Haiti, American officers in the Guardia did not draw double pay, making it difficult to attract even noncommissioned officers to the organization. Both neglected by the military government and despised by Dominican residents, who considered Guardia members traitors to the nationalist cause, the constabulary force was neither large enough nor well enough trained to effectively assist the Marines in policing the country.50

Early in the campaign, Marine operational reports indicated that captains or lieutenants usually led combat patrols of 40–50 men in response to collected intelligence. After the first year, operations transitioned to smaller patrols spread thinly across the countryside. In many areas, the rainforest underbrush was so thick that Marine patrols limited their searches to established trails. Commanded by noncommissioned officers, these detachments consisted of 10–15 Marines marching single file along narrow footpaths, which baited the guerrilla fighters into battle. Marines sometimes avoided ambush by conducting reconnaissance by fire. When approaching terrain ideal for an attack, the patrol point guard would shoot into the jungle, tricking guerrillas into returning fire and giving away their position before the Marines had fully entered the trap.51 This practice was not without its dangers, however. In August 1918, insurgents ambushed a patrol of four Marines as they were rounding the turn of a trail and crossing a stream. Only Private Thomas J. Rushforth survived the attack. Bleeding from more than six wounds, including a severed right hand by a machete blow, Rushforth managed to mount a horse and escape amid enemy gunfire. Despite being gravely wounded, the Marine returned to camp, reported the skirmish, and asked to lead a rescue party back to the scene of the attack.52

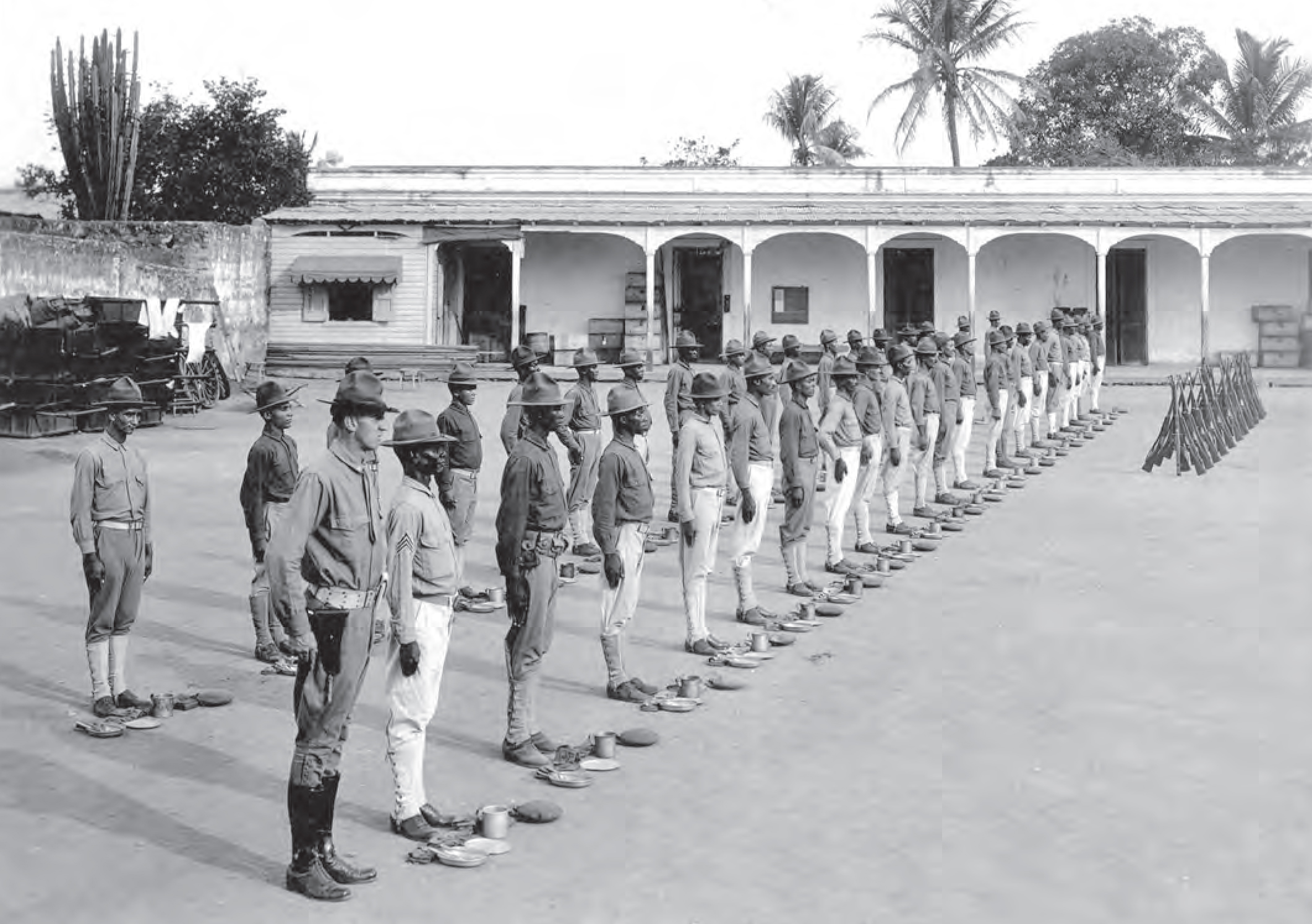

Equipment inspection, Guardia Nacional Dominicana. Dominican Republic photo, HIRB, MCHD

As the occupation dragged on, the military forces grew increasingly edgy and frustrated. The expansion of the Marine Corps into Europe during World War I siphoned many of the best officers from the Caribbean, and those remaining or newly deployed to the Dominican Republic were inadequately trained and ill-prepared for the difficult task of carrying out counterinsurgency operations. In addition, many Marines resented what they perceived as a slight in their service record and a hindrance to their potential for career advancement.53 The enemy remained elusive, and Marines began to regard all Dominicans with suspicion. Throughout the occupation, Marine leaders asserted that their primary goal was to protect a law-abiding majority against a minority of insurgents. Marines deliberately labeled opponents “bandits” to emphasize this distinction and to uphold the righteous aims of American efforts; but, when women and children began accompanying guerrilla bands in 1918, the American troops found it extremely challenging to distinguish guerrillas from refugees and other ordinary inhabitants in rural precincts.54 Many Marines turned against the population they were assigned to protect, meting out gratuitous punishment regardless of an individual’s guerrilla involvement. Complaints against Marine conduct surged as it became common for patrols to burn rural homesteads and personal possessions. If the inhabitants fled, Marines often fired at them. The rationale for this practice, as Captain William C. Harlee explained, was the incorrect assumption that “People who are not bandits do not flee the approach of Marines.”55 Not surprisingly, such brutal treatment created more insurgents and guerrilla supporters among previously uninvolved Dominicans. As one prominent Dominican explained, “When someone . . . was killed, his brothers joined the gavilleros [bandits], to get revenge on the Marines . . . Some joined the ranks inspired by patriotism, but most of them joined the ranks inspired by hate, fear or revenge.”56

Cartoon of a gavillero, or bandit, by Mattingly. Courtesy of Leatherneck, 1919

Popular Protest in the United States

U.S. entry into World War I had pushed Marine actions in the Caribbean into the background, but with the declaration of Armistice in 1918, Germany no longer represented an imminent threat to U.S. national security. Accusations of Marine atrocities, which peaked during this period, further discredited the American occupation. While most of the Marines and Guardia conducted themselves in a creditable manner, reports of abuse and cruelty reached the United States and shocked public opinion. Peasants charged the occupying forces with committing atrocities, such as rape, torture, imprisonment, and even death. Among the most egregious culprits of Marine misconduct was Captain Charles F. Merkel, who in 1918 faced a military tribunal for allegedly beating and disfiguring one Dominican prisoner and ordering four others shot during patrol operations near Hato Mayor. Reported to the authorities by his own men, Merkel committed suicide while awaiting trial in Marine custody.57 Organized opposition to the American occupation grew rapidly in response. Government representatives from Brazil, Uruguay, Colombia, and Spain condemned the intervention and advised the United States to end the occupation, while Latin American newspapers launched a determined campaign against the U.S. intervention in the Dominican Republic.58 In the United States, articles on the occupation appeared regularly in The Nation, Journal of International Relations, and Reforma Social, a New York-based publication distributed throughout Latin America. This groundswell of anti-imperialist agitation erupted in popular backlash against American foreign policy during the 1920 presidential campaign.

By highlighting the role of the Marine Corps in enforcing U.S. occupation in Hispaniola, Senator Warren G. Harding followed the lead of outspoken editorials in The Nation. As early as 1917, the leftist weekly magazine had pronounced the United States guilty of “[i]mperialism of the rankest kind” for imposing foreign rule in the West Indies by force of arms.59 The periodical devoted increasing attention to the topic after World War I, when critical essays by Oswald Garrison Villard, founder of the Anti-Imperialist League and editor of The Nation from 1918 to 1932; James Weldon Johnson, president of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People; and foreign affairs journalists Lewis S. Gannett and Kincheloe Robbins censured the U.S. military government in Santo Domingo for its oppressive treatment of local residents. Harding thus evoked a spate of evidence when, quoting nearly verbatim from The Nation, he called his opponent’s utterances “the first official admission of the rape of Haiti and Santo Domingo by the present Administration.”60

Raising the Dominican flag at Fort Ozama, Santo Domingo, on the occasion of Dominican President Horacio Vásquez’s inauguration, July 1924. Dominican Republic photo, HIRB, MCHD

The provost counts and censorship of the press prompted the strongest outcry among citizens of the United States and the other American republics. In July 1920, Otto Schoenrich, a North American writer, reported that the provosts courts, “with their arbitrary and overbearing methods, their refusal to permit accused persons to be defended by counsel, and their foreign judges, foreign language and foreign procedure, are galling to the Dominicans, who regard them with aversion and terror.”61 Throughout the occupation, all insurgent-related crimes funneled through the military courts, where the Marine Corps exercised wide powers of arrest as provost marshals. Many captains and lieutenants serving in this capacity did not speak Spanish and had received no special training, yet still wielded the authority to detain and sentence suspected enemies. Prisoners were occasionally shot without trial or killed while trying to escape, prompting military authorities in Santo Domingo to admonish Marines in the field to secure prisoners more carefully so as not to raise suspicion of judicial misconduct.62 Even with efforts to ensure due process, military records indicate that court officials did little to hide their derision for Dominican defendants and complainants, favoring instead the word of their American compatriots as a matter of course.63 The case of Captain Charles R. Buckalew spurred intense criticism of the military courts in the Dominican press, inciting outrage and leading some social clubs to close in response to rising U.S.-Dominican tensions. In 1920, Dominican lawyer Pelegrín Castillo accused constabulary Captain Buckalew of murdering four Dominican prisoners and committing other atrocities, such as crushing the testicles of a suspected guerilla with a stone. When all of the prosecution’s witnesses suddenly “voluntarily recanted and acknowledged that they falsely testified,” the provost court ruled that these circumstances made it “impossible to establish the truth of the accusations made against Charles R. Buckalew” and dismissed the charges due to unreliable evidence.64 For his part Castillo faced a military tribunal for apparently making false accusations. The provost court eventually exonerated him, and mounting evidence against Buckalew compelled the military court to bring the Marine officer to trial. Despite strong indications of guilt—including a partial confession—American officials again acquitted the Marine captain on technical grounds. Furthermore, as historian Bruce Calder has observed, the defendant’s statement largely corroborated Castillo’s earlier charges, suggesting that the witnesses may have recanted their testimonies under duress.65

Press censorship also emerged as a flashpoint of controversy in the summer of 1920, when the trial of Dominican poet Fabio Fiallo incited indignation and criticism throughout Latin America and the United States. Under American occupation, Dominican newspapers could not legally publish commentary on military government actions nor could they print evocative concepts, such as “national,” “freedom of thought,” “freedom of speech,” or “General” as a title for Dominican leaders.66 Infractions landed offenders in the American provost courts, which had a reputation among Dominicans of being unjust and cruel. In July 1920, Dominican newspapers published several stridently hostile articles and speeches that leaders had delivered during a “patriotic week,” an event held to raise funds for their oppositional movement. Several individuals, including Fiallo, landed in jail and were convicted by a military commission. Their sentences initially remained a secret, and rumors swirled that they had been condemned to death. The story spread throughout Latin America, and news of the injustice reached Washington by way of Mexico City and Uruguay. Although the verdict had been exaggerated, Fiallo’s sentence remained extreme. The poet not only began serving a three-year term of imprisonment with hard labor, but also was levied a $5,000 fine. The State Department endeavored to arrange Fiallo’s release, but he remained imprisoned for several weeks and was subsequently freed under the condition of military surveillance.67

The following month, Harding’s vehement campaign rhetoric thrust Dominican allegations of Marine brutality and oppressive military governance into the political limelight. He intended the charges to reflect poorly on the Wilson administration, especially Franklin D. Roosevelt and his superior, Secretary of the Navy Josephus Daniels. The strategy worked. Almost immediately newspapers and publications that had previously supported the occupation or failed to report on it assumed a more critical stance. Then, in the closing weeks of the national election, a private letter written by Brigadier General George Barnett, Commandant of the Marine Corps, leaked to the press. The missive, directed to the commander of Marine forces in Haiti, seemed to corroborate the worst charges of troop misconduct. Referring to the proceedings of a recent court-martial, Barnett expressed shock and dismay over what he believed to be the “indiscriminate killing of natives” in Hispaniola.68 Journalists clamored for an official investigation and immediate withdrawal of U.S. troops. Daniels responded to the negative publicity by ordering an internal investigation, but the findings failed to quell public protest. Even the New York Times, which a few months earlier had printed a front-page editorial against Harding’s nomination, issued regular updates on the Republican candidate’s charges, Roosevelt’s campaign rebuttals, and the Wilson administration’s formal inquiry into the matter.69 Harding won the presidential election in a landslide victory.70

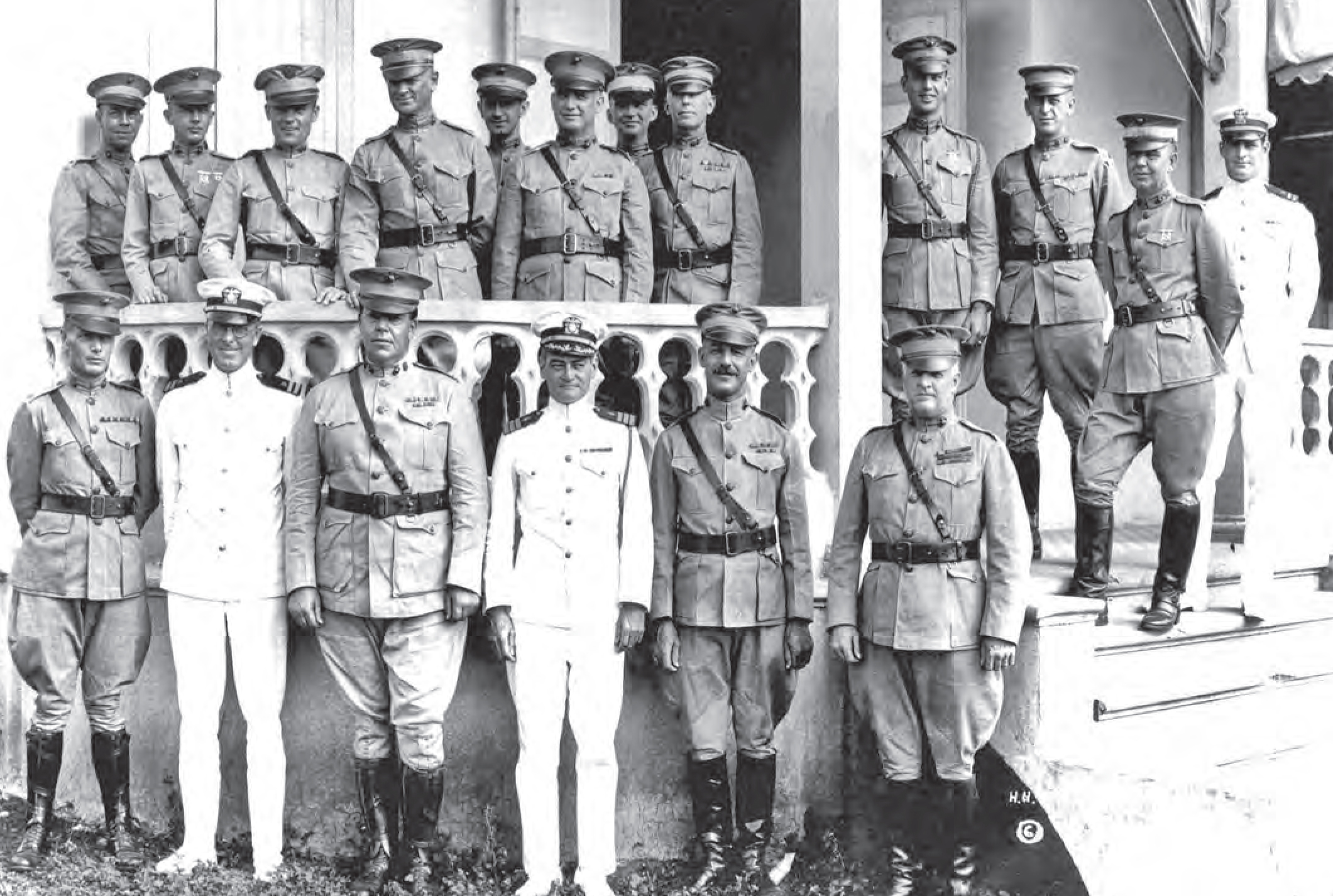

Acting military governor, BGen Harry Lee, USMC (first row, far right), with military staff. Dominican Republic photo 530542, HIRB, MCHD

Receiving nearly twice the popular vote as the Democratic ticket, he appealed to war-weary Americans who craved a “return to normalcy” or reorientation toward peace and domestic prosperity in the aftermath of the Great War. Exposing the failures and vulnerabilities of military occupation, the election marked a turning point in U.S. military action in Hispaniola. The persistence of armed rebellion four years after the initial intervention and reports of oppressive American governance spurred opposition to the military occupation, while charges of Marine atrocities further hardened popular opinion and damaged the reputation of the U.S. Marine Corps. The impact was far greater in the Dominican Republic than in Haiti, where U.S. troops would remain until 1932. Efforts toward U.S. withdrawal from the Dominican Republic began immediately; the outgoing Wilson administration submitted a proposal for U.S. departure before the end of the year. Although the initial plan was unsuccessful, Harding’s administration resumed negotiations with Dominican leaders the following spring and enacted a complete transfer of power by September 1924.

Baseball in the Dominican Republic.

Smedley D. Butler Papers, Alfred M. Gray Marine Corps Research Center, Marine Corps University

Withdrawal

Harding’s secretary of state, Charles Evans Hughes, entered into protracted negotiations with Dominican representatives over the terms of U.S. withdrawal. The State Department encountered resistance from both the Dominicans and from the military government until Brigadier General Henry Harry Lee, a veteran with 24 years of service in the Marine Corps, replaced the much-maligned Navy Rear Admiral Thomas Snowden and his successor Rear Admiral Samuel S. Robison as military governor.71 Acting as brigade commander as well as military governor, Lee oversaw the military provisions of withdrawal. He formulated a plan that would lay the groundwork for a peaceful transition of power. He reduced and concentrated the 2d Brigade garrisons of the northern and southern districts to the capital and other principal cities. He also dedicated significant resources toward improving the Guardia Nacional Dominicana as the primary peacekeeper in anticipation of U.S. withdrawal.

The centerpiece of his plan was the reorganization of policia training to reform the Guardia Nacional. Lee aimed to replace the remaining 44 American officers, sufficiently train an enlisted force of 1,200, and assign Dominican forces to all Marine outposts by the close of 1922. To this end, he planned to bring in 24 Dominican officers and all enlisted men for formal training at Haina, a new officer candidate school established in 1921. Buenaventura Cabral, a regional governor, assumed command of the constabulary, although Marine officers remained charged with the accelerated training program. Americans selected Dominican recruits carefully, preferring to train Guardia members who had previously suffered at the hands of insurgents. Under the new system, all officers and enlisted men would complete six months of training at Haina and an additional six months of supervised fieldwork before advancing from probationary status. With instruction in counterinsurgency tactics, the Dominican constabulary organized elite antiguerrilla outfits and began conducting successful patrols. In time, these paramilitary auxiliaries, renamed the Policía Nacional Dominicana, would take over Marine outposts, thereby allowing the American troops to garrison in principal cities.72

Lee announced a more benevolent policy toward the Dominican civilian population as well. He curbed the excesses of the provost courts, investigated charges of Marine misconduct, and ordered culprits to trial. He made the guards subject to civilian law. He also began an intensive indoctrination program for the troops. His primary purpose was to convince the Marines that the Dominicans were not the enemy and that their mission was to make the U.S. withdrawal a success:

The Forces of the United States did not enter this Republic to make war on the Dominican people. Far from it! . . . The object of the United States as explained in the beginning has never changed. It has been throughout the occupation to this time of returning the government to the Dominican people an unselfish object, looking only toward the betterment of the Dominican people and at great expense to the United States. Now ask yourself if your conduct in your attitude toward the Dominican people is as worthy as that of your country, and bear in mind that your conduct represents the United States in the eyes of the Dominican people.73

Lee ensured that subordinate commanders followed his rigorous training plan. Weekly reports from these years include program summaries and preliminary self-assessments for the indoctrination of enlisted Marines. Film screenings and sports, especially baseball, eased troop boredom and contributed to more harmonious Marine-civilian cooperation.74 Such measures not only worked to contain the civilian population’s disaffection but also helped to soothe the many grievances Dominicans had harbored against the occupying forces since their arrival in 1916.

In the United States, formal investigations launched in response to public outcry, one by a naval court of inquiry and one by a special committee of the U.S. Senate, could not substantiate charges of abuse. The public testimony of Dominicans before the Select Committee on Haiti and Santo Domingo between 1921 and 1922 gave vivid detail to a litany of stories involving Marine misconduct. Public scrutiny as a result of the senatorial hearings did result in some immediate modifications to occupation policy. The 15th Regiment, for instance, ceased its practice of patrolling under junior officers. Until the end of the occupation, Marine officers sent the entire regiment into the field. The new field organization, unlike previous patrols, operated under the command of senior officers and carried previously defined objectives to be achieved. Although the senatorial committee ultimately concluded that the initial military intervention had been justified, it declared that the American administration had been ineffective. Professor Carl Kelsey, whom the American Academy of Political and Social Science sent to Hispaniola to conduct an independent study of the occupation, concurred: “The Marine Corps is intended to be a fighting body and we should not ask it to assume all sorts of civil and political responsibilities unless we develop within it a group of especially trained men.”75

The guerrilla conflict ended in the spring of 1922, after the United States and Dominican Republic signed an agreement terminating the military occupation. This definite plan for withdrawal no doubt hastened the drawdown. Equally important was the internal evaluation of the operational effectiveness and subsequent recalibration of Marine policy and tactical procedure. One notable example of this shift is the analytical writing of Lieutenant Colonel Charles J. Miller, chief of staff of the 2d Brigade during the final years of occupation, who identified five separate groups within the Dominican resistance: professional highwaymen or gavilleros; discontented politicians who used crime to advance their personal ambitions; unemployed laborers driven by poverty; peasants recruited under duress; and ordinary criminals. The self-reflective impulse after 1920 generated invaluable insights into the personal motivations of guerrilla fighters, which in turn inspired novel responses and solutions on the part of the military government. Most of the insurgents Miller had identified, for example, surrendered to American forces in exchange for near-total amnesty.

The knowledge and experience gained in the Dominican Republic further permitted the Marine Corps to implement improved air-ground counter-insurgency operations in Haiti (1915–34) and Nicaragua (1926–32). Because of the novelty of aviation, airplanes in the Dominican Republic primarily performed logistical duties, such as mail delivery, aerial photographic surveying and mapping, and shuttling officers between Marine outposts and the capital; however, commanders began to perceive the utility of aviation for air-ground combat maneuvers.76 Air- craft initially supported ground operations by providing aerial reconnaissance, but communication methods hindered coordination.77 Even so, Colonel James C. Breckinridge, commander of the 15th Regiment, reported that the airplanes had been equipped with machine guns and would “play a conspicuous part in the hunting out of the bandits lurking in the jungles.”78 Experimenting with aerial attacks against Dominican insurgents in the San Pedro de Macorís district, ground patrols discovered it was far more beneficial to signal insurgent locations to pilots, who would then attack guerrilla forces directly.79

De Havilland DH-4B, one of five stationed at Santo Domingo with a Lewis .30-caliber machine gun on the scarf mount, 1919. Gen Christian F. Schilt, USMC, Dominican Republic photo, HIRB, MCHD

In the process of developing counterinsurgency tactics in the Dominican Republic, the Marine Corps also committed—and learned from—its mistakes. When it became evident in 1921 that the United States planned to dismantle the military government, the administration authorized one final campaign to eliminate guerrilla insurgency in the Eastern District. Over the course of five months, the 15th Regiment skillfully executed nine cordon operations. Assisted by biplanes spotting suspicious activity from the air, the Marines would patrol in gradually constricting circles to seal off and screen entire village populations for insurgents. Every male Dominican between the ages of 10 and 60 would be arrested, taken into a floodlit detention center, and identified by witnesses concealed behind canvas screens. Although some 600 “bandits” had been captured in the sweeps, the Marine commander abruptly dropped the method due to widespread complaints.80

Conclusion

In the immediate aftermath of World War I, American society had shifted its moral orientation to a more negative opinion of imperialism, patently rejecting military invention as a justifiable course of diplomatic action. As the most visible imprint of U.S. presence in the island republics, the Marine Corps came under intense scrutiny for its apparent lack of discipline and forthright leadership. In the end, the stalemate of guerrilla warfare, oppressive policies of press censorship, and sensational reports surrounding Marine abuses overshadowed its efficiency and success in the early phase of the intervention and produced conditions in which military occupation was no longer tenable. The process of reflecting on Marine experiences in the Dominican Republic to precipitate U.S. withdrawal laid the groundwork for the development of small wars doctrine. Before the Marine Corps departed Santo Domingo, Major Samuel M. Harrington had published “The Strategy and Tactics of the Small Wars,” an operational prescription for six steps in conducting a small war.81 This and other doctrinal writings benefited from the collection and evaluation of tactical and strategic data from the occupation in the immediate post-Dominican years. Mandatory lectures at both the field and company officers’ schools included some of the first attempts to incorporate small wars lessons into the curriculum at the new Marine Corps Schools at Quantico. Although small wars training did not expand beyond these tentative steps until the Nicaraguan intervention, the lessons of the Dominican experience—both successes and failures—contributed significantly to the formation of the Small Wars Manual more than a decade later. Today, as irregular warfare increasingly becomes the standard pattern of engagement, the military insights gained through these early counterinsurgency operations serve as a stark reminder of the need for constant evaluation and adaption in tactical procedure and of the lessons that can be gleaned thereof.

• 1775 •

Endnotes

- Although Roosevelt’s reputation in U.S.-Latin American affairs today rests largely with the Good Neighbor Policy, a foreign policy initiative that pledged nonintervention and equitable trade agreements in the 1930s and 1940s, the future president did not always espouse such progressive thinking with regard to hemispheric relations. According to biographer Frank Freidel, Roosevelt had nothing to do with the drafting of the Haitian Constitution. See Graham Cross, The Diplomatic Education of Franklin D. Roosevelt, 1882–1933 (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2012), 104; and Frank Freidel, Franklin D. Roosevelt: The Apprenticeship (Boston, MA: Little, Brown and Co., 1952).

- Franklin D. Roosevelt, campaign speech dated 18 August 1920, quoted in Cross, The Diplomatic Education of Franklin D. Roosevelt, 104.

- Warren G. Harding, “A Speech by Senator Warren G. Harding to Delegation of Indiana Citizens, Marion, Ohio, 28 August 1920,” in Speeches of Senator Warren G. Harding of Ohio, Republican Candidate for President (New York: Republican National Committee, 1920), 91.

- Contemporary audiences understood that the assistant secretary of the Navy referred to in Harding’s speech was Franklin D. Roosevelt, the Democratic vice presidential nominee.

- The U.S government had long expressed interest in the Dominican Republic. President Ulysses S. Grant entertained the prospect of annexing the island nation, but the U.S. Senate defeated the measure in 1871. Subsequent American victory in the Spanish-American War (1898) furnished the United States with territorial possession of Puerto Rico and Cuba, but the U.S. Navy expressed a keen interest in acquiring naval bases in Hispaniola as well.

- Maj Bruce Gudmundsson, USMCR (Ret), “The First of the Banana Wars: U.S. Marines in Nicaragua 1909–12,” in Counterinsurgency in Modern Warfare, ed. Daniel Marston and Carter Malkasian (Oxford, UK: Osprey Publishing, 2008), 60.

- In 1903, the new Dominican government under Gen Carlos F. Morales stopped paying its foreign debt with the aim of negotiating more favorable terms.

- Theodore Roosevelt, “The Roosevelt Corollary to the Monroe Doctrine,” in Robert H. Holden and Eric Zolovs, ed., Latin America and the United States: A Documentary History (Cary, NY: Oxford University Press, 2000), 100–2.

- Theodore Roosevelt, “The Dominican Republic Challenge,” in Holden and Zolovs, Latin America and the United States, 103–4.

- Max Boot, The Savage Wars of Peace: Small Wars and the Rise of American Power (New York: Basic Books, 2003), 137. Following ratification of the agreement by the U.S. Senate, President Roosevelt issued a proclamation enacting the Convention between the United States of America and the Dominican Republic Providing for the Assistance of the United States in the Collection and Application of the Customs Revenues of the Dominican Republic on 25 July 1907.

- Emily S. Rosenberg, “The Invisible Protectorate: The United States, Liberia, and the Evolution of Neocolonialism, 1909–40,” Diplomatic History 9, no. 3 (July 1985): 193.

- Boot, The Savage Wars of Peace, 129.

- For more on Germany’s “secret war” in the Americas, see Michael C. Desch, When the Third World Matters: Latin America and United States Grand Strategy (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1993); Friedrich E. Schuler, Secret Wars and Secret Policies in the Americas, 1842– 1929 (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 2010); and David Healy, Drive to Hegemony: The United States in the Caribbean, 1898– 1917 (Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1988), 72–76.

- The USS Castine (PG 6) brought 300 Marines and 130 sailors to Santo Domingo to guard the American legation. The USS Prairie (AD 5) transported approximately 150 Marines; the 6th Company, commanded by Capt Frederic M. Wise, was an infantry unit, and the 9th Company, under the command of Capt Eugene P. Fortson, was a field artillery unit with four 3-inch guns. Wise had overall command of the force, which was designated a provisional battalion.

- Boot, The Savage Wars of Peace, 168. During October and November 1915, Marines engaged in considerable fighting with cacos in northern Haiti, where insurgents were thought to be receiving arms from Arias, then-minister of war, at Santo Domingo.

- Referring to all of Latin America, President Wilson once confided to a visiting British statesman: “I am going to teach the South American republics to elect good men!” See Burton J. Hendrick, Life and Letters of Walter H. Page (Garden City, NY: Doubleday, Page and Co., 1922), I: 204.

- Frederic M. Wise to George Barnett, 24 May 1916, Dominican Republic Subject Files, Historical Inquiries and Reference Branch (HIRB), Marine Corps History Division (MCHD), Quantico, VA; and Frederic M. Wise and Meigs O. Frost, A Marine Tells It to You (New York: J. H. Sears & Company, Inc., 1929), 141.

- Max Henriquez Ureña, Los Yanquis en Santo Domingo: La Verdad de los Hechos Comprobada por Datos y Documentos Oficiales (Madrid: M. Aguilar, 1931), 87–88.

- Wise and Frost, A Marine Tells It to You, 143.

- Keith B. Bickle, Mars Learning: The Marine Corps’ Development of Small Wars Doctrine, 1915–1940 (Boulder, CO: Westview Press, 2002), 108. On 12 May, the USS Dolphin (PG 24) and the USS Culgoa (AF 3) arrived with RAdm Caperton, Maj Newt Hall, and the 4th and 5th Companies on board. The USS Hector (AR 7) brought the 24th Company to the Dominican Republic the following day.

- Col Theodore P. Kane arrived in Santo Domingo on board the USS Panther (1889) with the headquarters of the 2d Regiment and three infantry companies on 23 May. He took command of all Marines on shore in the Dominican Republic and set up a temporary headquarters in the U.S. consulate building. The USS Sacramento (PG 19) awaited orders off shore near Puerto Plata while the Panther and USS Lamson (DD 18) patrolled the waters near Monte Cristi. By the end of the month, Marine strength in the country totaled 11 companies, drawn mostly from the 1st and 2d Regiments.

- Bruce J. Calder, The Impact of Intervention: The Dominican Republic during the U.S. Occupation of 1916–1924 (Austin: University of Texas Press, 1984), 8.

- Healy, Drive to Hegemony, 196–97.

- William S. Caperton to William S. Benson, 15 June 1916, William S. Caperton Papers, Library of Congress, Washington, DC.

- On 4 June, RAdm Caperton requested the U.S. Navy to send more Marines, and MajGen Commandant George Barnett ordered the entire 4th Regiment to proceed from San Diego, CA, to the Dominican Republic. The USS Hancock (AP 3) delivered the 4th Regiment to Monte Cristi on 21 June. With 828 men, this was the largest reinforcement to date.

- Thomas P. Carney, “Adventures of ‘San Diego’s Own’ Fighting through Santo Domingo” (unpublished manuscript, Gordon L. Pruner Papers, Collection 463, Alfred M. Gray Marine Corps Research Center [GRC], Marine Corps University [MCU], Quantico, VA).

- Joseph H. Pendleton, “Instructions to All Officers of the Forces,” 24 June 1916, Joseph H. Pendleton Papers, Collection 402, GRC, MCU, Quantico, VA.

- The main column consisted of 34 officers and 803 enlisted men. Carney, “Adventures.”

- Ibid.

- Alan McPherson, The Invaded: How Latin Americans and Their Allies Fought and Ended U.S. Occupation (Cary, NC: Oxford University Press, 2014), 41.

- Ivan Musicant, Banana Wars: A History of United States Military Intervention in Latin America from the Spanish-American War to the Invasion of Panama (London: Macmillan, 1990), 255. Equipped only with shrapnel charges, the artillery dispensed no high-explosive rounds in the caissons and so caused little physical destruction to the battlefield.

- Carney, “Adventures.”

- Ibid. The Marines could not pursue the insurgents due to the mountainous and overgrown terrain.

- Musicant, Banana Wars, 258.

- Carney, “Adventures.”

- “Two Marines Win Medal of Honor,” New York Times, 18 March 1917.

- Carney, “Adventures.”

- The detachments from the USS Rhode Island and USS New Jersey originally consisted of five officers and 128 enlisted men. Charles B. Hatch to George Barnett, 29 May 1916, Dominican Republic Subject Files, HIRB, MCHD, Quantico, VA.

- After a skirmish at Llanos Perez, the column halted at Lajas, where Bearss arrived with a detachment from the USS New Jersey. The major assumed command, and the troops continued on foot.

- Hiram I. Bearss to Joseph H. Pendleton, 13 July 1916, Dominican Republic Subject Files, HIRB, MCHD, Quantico, VA.

- Carney, “Adventures.”

- The United States justified military intervention in the Dominican Republic based on a perceived breach in the 1907 customs receivership treaty.

- “Marines Are Rewarded: ‘Noncoms’ Win Medals and Cash for Valor in Fighting Dominicans,” Washington Post, 5 November 1916.

- “Sees Us at Fault in Santo Domingo,” New York Times, 10 June 1916, 1.

- Richard Millett and G. Dale Gaddy, “Administering the Protectorates: The U.S. Occupation of Haiti and the Dominican Republic,” in U.S. Marines and Irregular Warfare, 1898–2007: Anthology and Selected Bibliography, ed. Col Stephen S. Evans (Quantico, VA: MCU Press, 2008), 108. Operating without clear guidelines from Washington, Capt Harry S. Knapp, USN, repeatedly expanded administrative authority into new areas and undertook an ambitious public works program to “remake Dominican society.” His earliest legislative action included a ban on firearms and the censorship of press, mail, and telegraph messages, which he believed could be used to incite insurrection. Oppressive conditions worsened after Knapp’s departure from office in mid-1918, when subsequent military governors tightened existing regulations and pursued additional, nonessential reforms, such as a proposal to change the nation’s name to Hispaniola and the elimination of cockfighting and prostitution.

- Bob Considine, “The Marines Have Landed,” Washington Post, 5 October 1958. Perez retreated, stealing a train for his getaway. Rapidly con- verging detachments of the 4th Regiment intercepted and captured him, and Perez was sentenced by a U.S. military court.

- Bickle, Mars Learning, 124–25. By October 1917, the military government had amassed nearly 30,000 pistols, 10,000 rifles, 2,000 shotguns, 200,000 cartridges, and thousands of machetes and knives.

- Bruce J. Calder, “Caudillos and Gavilleros versus the United States Marines: Guerrilla Insurgency during the Dominican Intervention, 1916– 1924,” Hispanic American Historical Review, 8, no. 4 (November 1978): 664.

- See, for example, Santo Domingo Leatherneck 1, no. 1 (1919): 12, 19, 26.

- The situation improved only slightly when U.S. entry into World War I necessitated the rapid expansion of this force. As late as 1920, more than half of the Guardia Nacional Dominicana officers were Marine officers and noncommissioned officers who had accepted Dominican commissions once dual pay had been instituted.

- Bickle, Mars Learning, 121.

- “The Sole Survivor,” Log of the U.S. Marines, Dominican Republic Articles and Newspaper Clippings, HIRB, MCHD, Quantico, VA. Rushforth received ample praise from his superiors, including the secretary of the Navy; however, he was not eligible for a Medal of Honor because there were no witnesses to confirm his actions.

- Millett and Gaddy, “Administering the Protectorates,” 109.

- Graham A. Cosmas, “Cacos and Caudillos: Marines and Counterinsurgency in Hispaniola, 1915–1924,” in U.S. Marines and Irregular Warfare, 137; and Calder, “Caudillos and Gavilleros,” 667.

- William C. Harlee, Eastern District Commander, to Commanding General, 25 January 1922, quoted in Calder, “Caudillos and Gavilleros,” 667. Marine command tried to curtail both of these measures, since senior officers hoped that remote homesteads would serve as gathering places where patrols might easily locate guerrilla fighters in the future. Headquarters also admonished Marine patrols to exercise caution when firing on fleeing civilians, especially women and children.

- Julio Peynado to Horace G. Knowles, 22 April 1922, quoted in Calder, “Caudillos and Gavilleros,” 669.

- Mark Folse produced a detailed study of Capt Merkel’s activities in the Dominican Republic and Marine Corps response. See Mark Folse, “The Tiger of Seibo: Charles F. Merkel, George C. Thorpe, and the Dark Side of Marine Corps History,” Marine Corps History 1, no. 2 (2016): 4–18.

- See, for example, “Asks U.S. to Quit Santo Domingo,” Washington Post, 11 September 1919. From his position of exile in Cuba, Dominican President Henríquez urged Dominicans to form patriotic juntas and solicited contributions to support the resistance campaign in Havana, where Dominican nationalists disseminated a steady stream of information to sympathetic journalists, press associations, and governments in Latin America and Europe. In the United States, the Haiti-Santo Domingo Independence Society gained support of prominent progressives, including Eugene O’Neill, H. L. Mencken, and Samuel Gompers.

- “Editorial,” The Nation, 1917, 153.

- “Constitution or League—Harding,” New York Times, 18 September 1920. In the same speech, Harding again implicated the Marine Corps: “. . . many of our gallant men have sacrificed their lives for the benefit of an executive department in order to establish laws drafted by an Assistant Secretary of the Navy to secure a vote in the League, and to continue at the point of the bayonet, a military domination.”

- Otto Schoenrich, “The Present American Intervention in Santo Domingo and Haiti,” Journal of International Relations 11, no. 1 (July 1920): 51.

- Calder, “Caudillos and Gavilleros,” 668–69.

- Calder, The Impact of Intervention, 128–29.

- Capt Buckalew also faced separate allegations of torture, which were later proven false but stoked Dominican opposition and outrage toward American forces. According to Leocadio Báez, a Dominican peasant from Salcedo, occupation forces kidnapped him when he was only 16 years old and forced him to act as a guide against Dominican insurgents. When the Americans suspected the teenager of knowing the location of an arms cache, Buckalew allegedly ordered a combined U.S. and Dominican contingent to torture him as well as 16 other victims. Báez, the sole survivor, suffered severe burns from a red-hot machete and could no longer walk. During the Marine investigation, Báez confessed under oath that his torturer was Ramón Ulises Escobosa, a Dominican who had not taken orders from U.S. officers and who did not deny the accusations. The military occupation exonerated the accused Marine officer, but popular opinion was not swayed. For decades thereafter, Dominicans considered Báez a cause célebre of Marine abuse. See McPherson, The Invaded, 96, 136–37.

- Calder, “Caudillos and Gavilleros,” 667.

- Dana G. Munro, Intervention and Dollar Diplomacy in the Caribbean, 1900–1921 (New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 1964), 321.

- The Nation, October 1920.

- Ibid.

- Amid the growing furor, Roosevelt reevaluated his position with regard to other nations in the Western Hemisphere, but the damage had already been done. See Cross, The Diplomatic Education of Franklin D. Roosevelt, 85–107.

- Democrat James M. Cox failed to earn a single electoral college vote in any of the 18 Western states and only secured 127 to Harding’s 404 in total. In the popular vote, Harding’s 16,181,750 votes dominated Cox’s 8,141,750.

- omitted

- The Marines remained on call to reinforce the policía if serious outbreaks of violence occurred.

- Harry Lee, “Indoctrination in Proper Attitude of Forces of Occupation toward Dominican Government and People,” in Rufus H. Lane, Santo Domingo (n.p.: 1922), 6–7.

- Harry Lee to John A. Lejeune, Special Reports, 1923–1924, U.S. Marine Corps 2d Brigade Diary, Dominican Republic Subject Files, HIRB, MCHD, Quantico, VA.

- Carl Kelsey, The American Intervention in Haiti and the Dominican Republic (Philadelphia, PA: American Academy of Political and Social Science, 1922), 198.

- Commanded by Capt Walter E. McCaughtry, the 1st Air Squadron began operations from an airstrip carved out of the jungle near Consuelo, a town 12 miles from San Pedro de Macorís. The squadron had 35 trained pilots and mechanics. In 1920, the air unit moved to an improvised airfield near Santo Domingo.

- Since radios were too large to fit in the cockpit, field units had to recover written messages dropped from the air.

- “Marines Use Airplanes to Fight Bandits,” Recruiters’ Bulletin, May 1919, Dominican Republic Articles and Newspaper Clippings, HIRB, MCHD, Quantico, VA.

- Langley, Banana Wars, 154.

- Ibid

- Maj Samuel M. Harrington, “The Strategy and Tactics of the Small Wars,” Marine Corps Gazette 6, no. 4 (December 1921): 474–91; and 7, no. 1 (March 1922): 84–93.