Elizabeth G. Boulton, PhD

To apply “mesh interventions,” whereby small actions undertaken by billions of people contribute to the mass and speed of the hyper-response, major research and development support could be invested in the household and community spheres. While it is acknowledged that much work has already occurred and is progressing in such areas as sustainability, eco-design, zero-carbon planning, transition towns, garden cities, garden suburbs, permaculture, urban farming, off-grid living, community gardens, and energy efficiency, the “home force” concept aims to resource and expand such innovation at scale and integrate threat logic.

This approach rests on the idea of building new forms of security from the ground up. It considers affective security, psychological safety, and physical human security as well as off-grid ecosolutions. It dares to ask, how can the full range of human security problems—including mental illness, obesity, drug abuse, domestic abuse, and more—be approached considering the task to concurrently “design” the hyperthreat out of existence? How are people protected if critical infrastructure such as water, sewerage, energy, or fuel supply is abrupted halted? Some ideas follow.

- Home force specialists. Considering the many benefits to the hyper-response of increased home- or community-based food growing; home cooking; local repair of clothes or other equipment; coordination of circular economy and recycling functions; disaster mitigation work; care for children, the elderly, and other vulnerable people; benefits associated with happy, thriving families and communities; local sports and exercise groups; and the workload associated with such tasks, there is an argument in favor of creating new forms of “home force specialist” employment. There are many ways that this could occur. For example, a suburban block may have one dedicated gardener who assists all homes to develop productive food gardens and upkeeps food plots on nature strips or nearby allotments. As another, more general example, households may nominate individuals to undertake such tasks, who would be paid in proportion to the functions they take on.

- Ecotransition coaches and transition support teams. Skilled coaches and support staff can be assigned to communities and conduct regular training and mentoring activities for community members, tailored to suit age groups, professions, and skill levels. This may demand four to eight hours of work per week, and for consistency, it could occur on the same day each week (e.g., Friday). Consequently, it would be understood across communities throughout the world that the specific day selected is devoted to Earth care and transition and resilience activities.

- Urban and city farming. The aim to grow as much food locally as possible, already being progressed under an assortment of initiatives across the world, can also be approached in a more strategic and deliberate way in collaboration with supermarkets, retailers, and existing circular economy expertise.

- Leverage existing successful initiatives. To achieve economy of effort and speed of response in the first year of PLAN E, one option is to provide a seismic funding boost to existing and successful “transition town”-type initiatives to quickly leverage existing expertise.

- Tradespeople leadership, close security, and mutual support. Tradespeople, such as electricians, plumbers, arborers, telecommunications specialists, painters, carpenters, and mechanics, will have an enormous job of retrofitting homes, communities, and vehicles. While it may seem obvious that these professionals should be involved in designing systems for this to best occur, in practice they are often excluded from ecovisioning and planning activities as well as government policymaking. Tradespeople, who often work independently, must be funded to participate in planning the hyper-response, since taking time away from their businesses leads to loss of income. Tradespeople need to be given paid leadership and planning roles to facilitate the vast mobilization and training of tradespeople and the development of the best ways for them to support the hyper-response. While bottom-up and context-specific solutions will be needed, some concepts to aid this exploration are offered here:

- Close protection. Tradespeople need to be understood as providing “close protection” to communities from the hyperthreat. They provide an inner layer of security through supporting household and community resilience, while in times of extreme weather events their skills are vital for repair and rebuilding. They can be conceived as being a type of latent army in possession of the exact skill sets needed to counter the hyperthreat.

- Mutual support. In the way that military units provide mutual support to one another in battlefield situations, agreements could be made whereby tradespeople from one region are allocated in support to those in a neighboring region during times of hyperthreat attack. These would be mutual support arrangements. Tradespeople and ecomultilateralism. Tradespeople can also be considered as national assets that can be used more widely in the fight against the hyperthreat. For example, deployable tradespeople are required for “ecorebuild squads.” Additionally, tradespeople will be vital for training the larger hyper-response force, specifically the millions of Earth citizens.

- Man caves and she sheds. These have been formed as places for people to connect while often undertaking carpentry or minor construction projects for their communities. Because they contain personnel and skills useful for countering the hyperthreat, they could also be invited to become part of the hyper-response or form a basis for a capability that could be expanded.

Communities, Design Thinking, and Research and Development

To reduce stress on both humans and the planet, various aspects of daily household and community activities can be redesigned. Multidisciplinary teams involving parents, caregivers, and experts in urban design, tradespeople, preventative health, psychology, education, child development, artificial intelligence, information technology, circular economy, and sustainable supply chains could undertake formal research and development work to develop new approaches. What is different here from current practice is the transdisciplinary nature of design teams, the involvement of the community in research and development, a different understanding of expertise, and the scale of innovation resourcing directed toward homes and communities. For example, parents’ groups might lead a design effort with design-thinking specialists, product designers, urban designers, and eco-specialists supporting them.

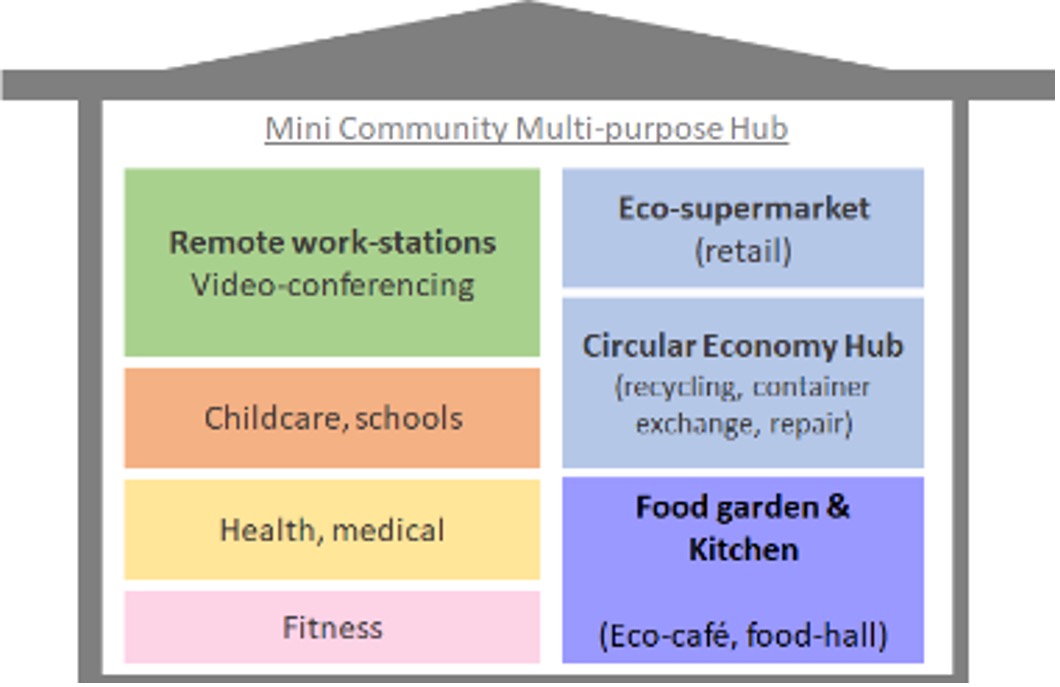

One example of how household, family, and community activities could be redesigned is the “minicommunity multipurpose hub,” or “minimulti” idea (figure F-1). To reduce commuting burdens, smaller schooling facilities could be colocated with remote work office spaces and other facilities needed for daily living, especially circular economy innovations. To picture it, a parent no longer has to drive their children and themselves long distances to get to school and work. A school running track may meander through local urban food gardens, which could also be used within the school’s ecology curriculum. To purchase pasta at the ecosupermarket, the parent returns the reusable pasta container they used last time. At lunchtime, everyone uses the multimini food garden and kitchen, which employs skilled nutrition-oriented cooks. Meals could be centrally prepared, if desired. A parent can go to an exercise class while dropping their child at childcare.

Figure F-1. Minicommunity multipurpose hub (minimulti)

Source: courtesy of the author, adapted by MCUP.