Michael P. Ferguson

14 August 2023

https://doi.org/10.36304/ExpwMCUP.2023.07

PRINTER FRIENDLY PDF

EPUB

AUDIOBOOK

Abstract: This article examines the means through which disinformation made its way into major media outlets and the U.S. intelligence community in the months preceding the 2003 United States-led invasion of Iraq. Most of the relevant literature tends to frame this period in terms of failure, directed at either intelligence producers or consumers. Instead, this study approaches the issue from a perspective of success—namely that of a foreign disinformation campaign—which may reveal instructive lessons overlooked in previous research. Despite its role in launching the Iraq War (2003–11), disinformation remained ill-defined and shallowly analyzed in the public sphere in the years between the end of the Cold War in 1991 and Russia’s interference in the 2016 U.S. presidential election. As international tensions rise and the U.S. Joint force leans more heavily on open-source information in its operations, it is imperative that the American people, intelligence analysts, and policymakers understand how the environment has been exploited to build false consensus during periods of heightened political instability.

Keywords: Iraq, disinformation, intelligence, open-source intelligence, OSINT, Operation Iraqi Freedom, OIF, misinformation

Introduction

Despite the prominent role it played in launching the 2003 United States-led invasion of Iraq, the word disinformation did not appear once in the 2015 National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA). However, the 2023 NDAA mentioned the term 10 times, in addition to similar concepts such as misinformation and propaganda.1 These ideas, once consigned to Cold War history books, now flood the current conversation on national security. From manufactured images of Russian president Vladimir Putin in prison to simulated war footage with lifelike realism, the power for information to deceive has taken a turn for the worse in recent years.2 Meanwhile, exploitation of open-source intelligence (OSINT) has become the skill du jour of the Ukrainian Army since Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in February 2022. This form of tradecraft has consequently garnered more attention from the U.S. defense enterprise as well.3 Considering that this year marks the twentieth anniversary of the Iraq War (2003–11), efforts to combat more recent trends of deception must take into consideration the role that disinformation played in fueling that war.

The public case for Operation Iraqi Freedom (OIF), not in full but certainly in part, grew from an elaborate but still enigmatic foreign disinformation campaign designed to build international consensus for the removal of Iraqi president Saddam Hussein by military force. Although the infamous source known as “Curveball” has deservedly absorbed most of the attention in this regard, there were other forces at work with a unified objective.4 This process of persuasion began with breaking news from trusted U.S. media sources only months after al-Qaeda’s 11 September 2001 (9/11) terrorist attacks on the United States. Citing Iraqi exiles with alleged insider knowledge, these reports claimed that Hussein’s regime had close ties to al-Qaeda and was running dozens of weapons of mass destruction (WMD) facilities throughout the country.5

What was the genesis of such reports? Why were they so appealing? What are the lessons for intelligence analysts and strategists charged with anticipating threats for combatant commanders and decision makers today? The answers to these questions are essential to understanding the role of disinformation in modern defense, but they are unclearly defined and inadequately explored in open-source analysis of the misconceptions that led to the Iraq War. This article offers a brief review of disinformation research in historical context before defining the etymological divides between misinformation and disinformation. After establishing this foundation, the article examines how flawed information spread through trusted public sources after the 9/11 attacks, tracks the evolution of the invasion consensus through the Iraqi exile network, and explores implications for U.S. decision makers and the analytical profession.

The State of the Art

Terms such as disinformation, active measures, and perception management were commonly heard during the Cold War, as the Soviet Union employed them liberally via its intelligence networks and globally dispersed Communist International (Comintern).6 The Kremlin even had a directorate on the general staff dedicated exclusively to active measures that worked to shape the mass consciousness of various societies.7 Western universities and think tanks flourished with research on these topics as the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) aimed to soften the blow of Communist disinformation in the Western world. But an abrupt end to the Cold War in 1991 brought about a false sense of security as the specter of worldwide Communism faded from public view.

Mark M. Lowenthal, former U.S. assistant director of central intelligence for analysis and production, witnessed U.S. strategic intelligence dwindle after 1991 through a process that was “somewhat unsettling for the intelligence community as it attempted to find new focus.”8 The WMD controversy of 2003 did more to promote reflection on internal U.S. political dysfunction than the intrigues of external actors who exploited that environment.9 Even throughout the Global War on Terrorism, public discussions in the United States had little to say about coordinated disinformation campaigns and instead focused only marginally on how violent extremist organizations used the internet to recruit lone-wolf terrorists.10

That all changed with the 2016 U.S. presidential election. Russia’s campaign to influence American public opinion during this period, no matter how ineffective, caught the Western world’s attention, particularly because it came only two years after Russia’s shocking annexation of neighboring Crimea.11 This spawned a litany of research on state propaganda and the implications of social media misinformation.12 In other words, the Western world had some catching up to do.

Some of the most notable updates to the literature came from Thomas Rid, Peter Pomerantsev, Cailin O’Connor, James O. Weatherall, Moisés Naím, Natalie Grant, and Donald A. Barclay.13 Meanwhile, educational institutions investigated the impact of disinformation on society. Some even erected centers or launched journals designed to explore the subject, such as Harvard University’s Misinformation Review. A January 2023 study from the University of Southern California (USC) found that social media platforms contribute to the problem of disinformation by “rewarding users for habitually sharing information,” a finding that supports calls for governments to impose stricter controls on media giants.14 Existing and emergent outlets generated insightful primers on the supposed “post-truth” era as well.15 Established in 2001, The Journal of Information Warfare has been an authority on the subject, but as the USC study indicates, cybersecurity and social media research have cast a long shadow over the study of information operations.16 This places the more exquisite aspects of high-profile misinformation by human proxy into a somewhat niche category, considering that many post-Iraq War studies focused on internal U.S. government failure as opposed to the process of its exploitation by external forces.17

Few have explored how and why disinformation played a role in molding policy through trusted sources because it undercuts the very elixir that so many prescribe for combating disinformation—that is, putting faith in certain information sources or individuals who can “spot” inaccuracies.18 The precarious nature of studying disinformation—a process of separating the wheat from the chaff—demands that one approach such work assuming one has the capacity to identify the difference between the two. A well-crafted disinformation campaign, however, is designed to make this complicated. This is doubly true when a narrative originates from the enemy of one’s enemy, as was the case in 2002. Indeed, some who challenged the WMD evidence were ridiculed, such as Mohamed ElBaradei, the then-director general of the International Atomic Energy Agency who later won the Nobel Peace Prize.19 Had social media been as prevalent then as it is now, ElBaradei’s claims would likely have been branded with “missing context” warning labels if not altogether censored.20

The advent of social media, and more recently—and perhaps notably—the introduction of open-source generative artificial intelligence (AI) platforms such as ChatGPT, have only exacerbated issues associated with clarity in the information environment.21 Unfortunately, social media executives and even governments trying to improve the veracity of their platforms do not have all the answers. Such developments warrant further analysis of the campaigns that penetrated Western society’s best defenses against malign fictions. Because disinformation draws much of its power from ambiguity, a clear understanding of the terminology is essential to combating its harmful effects.

Intent + Power = Disinformation

Before examining how a distorted reality ushered the United States to war in 2003, it is necessary to first define key terms used in this article. The terms disinformation and misinformation remain undefined in NDAAs and ill-defined in the broader national discussion despite mounting fascination with them.22 As a result, they are often used interchangeably, which ironically laces the conversation on disinformation with misinformation because it is not rooted in uniform terminology.23 Disinformation is a deliberately constructed narrative intended to deceive, while the well-meaning carriers of that information who believe it to be true transform it into misinformation. One way to illustrate this relationship conclusively involves U.S. Supreme Court precedent for libel and defamation cases.

In New York Times Co. v. Sullivan (1964), the police commissioner of Montgomery, Alabama, L. B. Sullivan, sued The New York Times for publishing false information about the city’s treatment of civil rights protestors. The court ruled unanimously in favor of The New York Times, writing that a charge of libel required Sullivan to prove that the newspaper published the information with “actual malice” and “with knowledge that it was false or with reckless disregard for the truth.”24 In other words, the plaintiff must prove that the defendant spread disinformation intentionally and not simply because they were misinformed. This ruling is codified in 18 U.S. Code § 35 under “imparting or conveying false information.”25 Several countries have explored the idea of criminalizing the sharing of online misinformation, but such litigation would not likely survive in U.S. courts, which makes the fight against disinformation as much of an individual responsibility as it is a matter of policy.26

Since Russia’s attempts to influence the 2016 U.S. presidential election, open-source research on disinformation has focused overwhelmingly on foreign social media bots and online troll factories.27 But, like the civil rights activists before they wrote for The New York Times in 1964, fringe social media accounts lack the power and therefore the credibility to establish a narrative with enough influence to plant the seeds that grow into a broader field of misinformation.

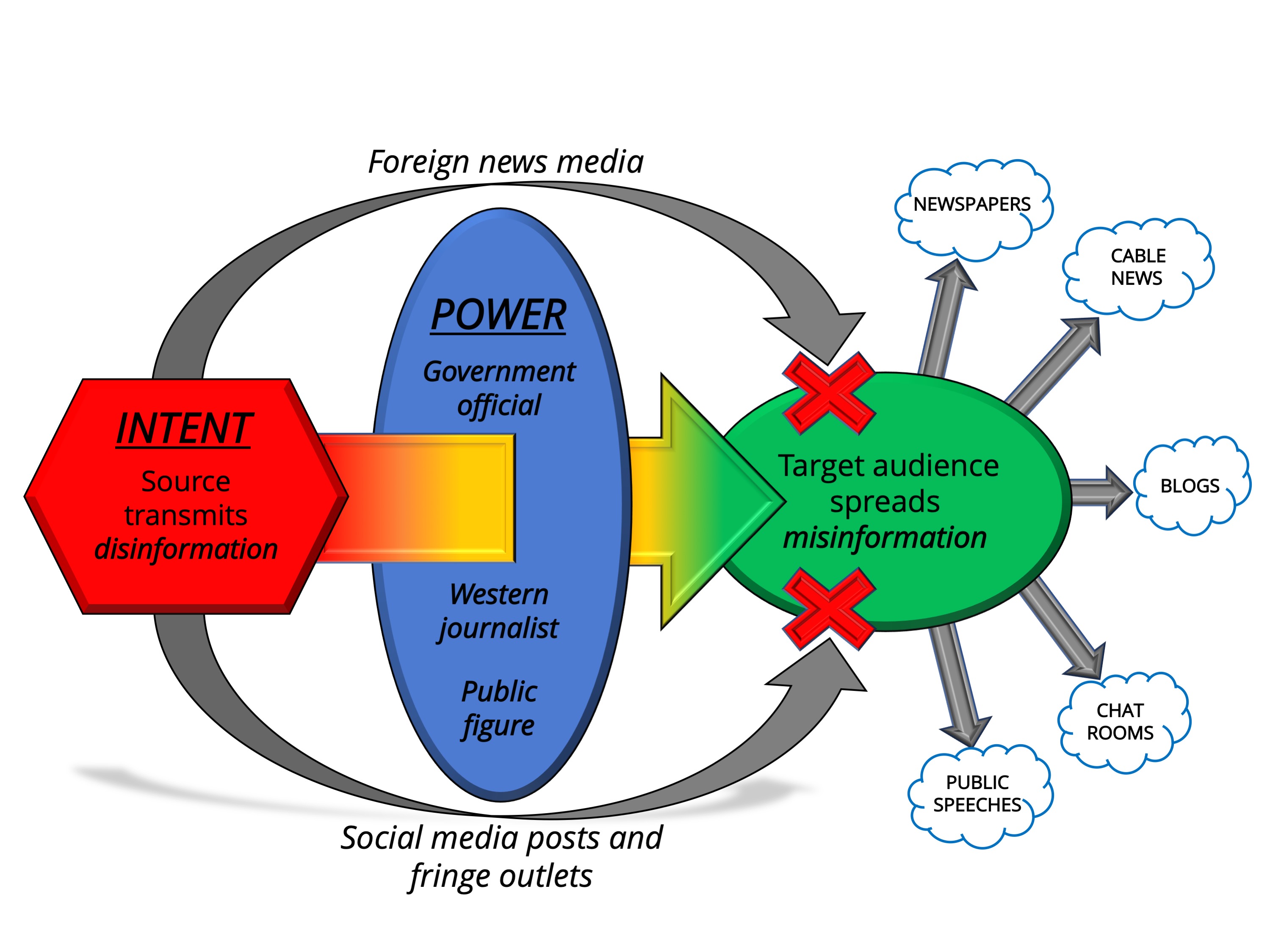

Figure 1. The process of turning disinformation into misinformation

The exploitation of trusted sources gives disinformation’s intent to deceive the power to do so.

Source: courtesy of the author, adapted by MCUP.

Disinformation, therefore, cannot become misinformation without a trusted source to serve as its unwitting carrier, which gives the false narrative its power (see figure 1). Knowing one’s audience is key to this process because trusted sources differ based on the target. For the purposes of this article, the term trusted sources refers to U.S. federal agencies and open sources commonly cited by reputable news publications, scholarly journals, and government entities because the disinformation surrounding Iraq’s WMD programs was designed to influence U.S. policy. In sum, the American public was misinformed by journalists and public officials who were the targets of a foreign disinformation campaign. This process began almost immediately after al-Qaeda’s 9/11 attacks on the Twin Towers of the World Trade Center in New York City and the Pentagon outside Washington, DC.

Building the Invasion Consensus

One of the first mentions of Iraq after the 9/11 attacks came from U.S. deputy secretary of defense Paul D. Wolfowitz during a meeting at Camp David, Maryland, just days after the Twin Towers fell.28 According to U.S. national security advisor Condoleezza Rice, his proposal was a nonstarter among White House officials at the time.29 The idea gained traction throughout 2002 after a slew of public reports and intelligence assessments propped up theories that Saddam Hussein had active and maturing WMD programs in Iraq. A heavily redacted 2004 report by the U.S. Senate Select Committee on Intelligence later disclosed the shaky foundations of this intelligence by revealing that the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) was “never able to gain direct access to Iraq’s WMD programs” because the agency “did not have any WMD sources in Iraq after 1998.”30

Certain Shia Iraqi exiles—some with ties to Iran—provided a convenient solution to this intelligence gap, and their testimonies often reinforced the WMD narrative.31 During a 20 September 2001 speech, one such exile named Ahmad Chalabi urged the U.S. Defense Policy Board Advisory Committee to stay the hand against Afghanistan and instead focus on Iraq.32 As various “anti-Saddam organizations began serious jockeying for U.S. favor” once regime change entered the public discussion in the spring of 2002, Chalabi’s longstanding goal of removing Saddam from power came into alignment with U.S. policy.33 In the following months, Chalabi and others he escorted around Washington, DC, matured the embryonic contention that Iraq was a threat that the United States could not afford to ignore. While Chalabi’s associates worked to grow support for this yarn in the open, other exiles such as “Curveball” built consensus secretly within Western intelligence agencies.

Professor James J. F. Forest of the University of Massachusetts provides a useful framework for understanding how and why these ideas took hold so effectively. In his research on political warfare and propaganda, he outlined a series of information requirements that the hosts of a disinformation campaign might ask during their target research: [1] What do they already believe about their world and/or their place in it? [2] What do they think they know, and what are they uncertain about? What assumptions, suspicions, prejudices, and biases might they have? [3] What challenges and grievances . . . seem to provoke the most emotional responses from them?34

First, U.S. policy toward the Middle East after 9/11 became rooted in the belief that the region needed democracy and that the United States was the only country powerful enough to deliver it to them. This mandate was evident in numerous public statements made by officials in the administration of U.S. president George W. Bush between September 2001 and March 2003, but it featured perhaps most prominently during the president’s 2002 commencement speech at the U.S. Military Academy at West Point, New York.35

Second, U.S. officials knew that Saddam Hussein was a bad actor who murdered his own people and violated United Nations (UN) treaties. He had also attempted to have U.S. president George H. W. Bush assassinated during his April 1993 trip to Kuwait, purportedly as revenge for the Gulf War (1990–91).36 The U.S. intelligence community was uncertain, however, if Hussein posed a clear enough threat to the United States to warrant forcible regime change through direct U.S. military intervention.

Third, in 2002 the United States was understandably experiencing one of the most emotional moments in its history. Establishing deeper ties between Hussein and al-Qaeda, the organization responsible for taking nearly 3,000 American lives on 9/11, only intensified those emotions. Flawed information furnished by Iraqi exiles to various Western officials in the coming months fulfilled each of these information requirements.37

Albert Weeks, a professor of international affairs at New York University, wrote in 2010 that Chalabi’s closest ties in the U.S. government were to Paul Wolfowitz and Richard N. Perle, chairman of the Defense Policy Board Advisory Committee—both of whom, coincidentally, were also some of the earliest advocates for military force against Iraq after 9/11.38 Their views were initially fringe, but they became mainstream based on the developments to which this article now turns.

The Externals

Ahmad Chalabi was a Massachusetts Institute of Technology- and University of Chicago-educated mathematician who left Iraq as a teenager in 1958, about a decade before Hussein’s rise to power.39 He headed a London-based opposition group known as the Iraqi National Congress (INC), which, comprised mainly of exiles, sought to reform Iraqi politics and increase Shia representation in Sunni-run Baghdad.40 The INC rose to prominence after U.S. president William J. “Bill” Clinton signed into law the Iraq Liberation Act of 1998, which established as U.S. policy the intent to remove Saddam Hussein from power—legislation for which Chalabi lobbied heavily.41 The act declared the following: It should be the policy of the United States to support efforts to remove the regime headed by Saddam Hussein from power in Iraq and to promote the emergence of a democratic government to replace that regime. . . . [The] President shall designate one or more Iraqi democratic opposition organizations that the President determines satisfy the criteria set forth in subsection (c) as eligible to receive assistance under section 4.42

Chalabi’s INC received that designation from Clinton.43 There was undeniable tension between officials in the U.S. Department of Defense (DOD) on one hand and those in the CIA and the U.S. Department of State on the other regarding externals, a term used to identify exiles and defectors outside the Iraqi government. It is well known that the CIA and Defense Intelligence Agency (DIA) used externals as sources during this period, but the CIA on average expressed greater suspicion in dealing with them.44 The relevant 2004 report by the Senate Select Committee on Intelligence exposed a wealth of dissonance between CIA and DIA assessments.

One DIA analyst detailed to the Office of the Under Secretary of Defense for Policy in 2002 even suggested that CIA analysis of links between Iraq and al-Qaeda “should be read for content only—and CIA’s interpretation ought to be ignored.”45 This friction is most evident when juxtaposing the memoirs of two contrasting players in this story: U.S. director of central intelligence George J. Tenet and U.S. undersecretary of defense for policy Douglas J. Feith. Feith mentions Chalabi no less than 40 times in his memoir, is effusive in his praise for the exiled Iraqi, and all but accuses the CIA and Department of State of conspiring against Chalabi for political reasons.46 Feith even goes so far as to blame failures in Iraq on other U.S. agencies’ suspicions toward Chalabi.47

Tenet, on the other hand, was suspect of Chalabi from the outset. Factored into his reasoning was Chalabi’s longstanding ties to Iran and his history of duplicitous and even illegal activities. In 1995, Chalabi led a failed effort to overthrow or assassinate Saddam Hussein, which was backed by an aggressive CIA officer whose operation was eventually shut down. The following year, Hussein’s army captured, tortured, and executed some 150 members of the INC in response.48 The CIA discovered that Chalabi or someone in his orbit had forged a document claiming that the U.S. National Security Council sponsored the coup attempt, and he showed this document to Iranian officials to elicit their support.49 Chalabi’s antipathy for Hussein’s regime brought Iran’s interests into Iraq up to and after the United States-led invasion, which culminated in one of the war’s most disastrous policies.

In his memoirs, President George W. Bush expressed regret for the now-infamous de-Ba‘athification policy that banned tens of thousands of Iraqis from employment: “Overseen by longtime exile Ahmad Chalabi, the de-Ba‘athification program turned out to cut much deeper than we expected, including mid-level party members like teachers.”50 Still, Chalabi wound up seated next to U.S. first lady Laura L. Bush at the 2004 State of the Union Address, and one senior U.S. official reportedly considered him “the Michael Jordan of Iraqi politics,” further demonstrating the influence that externals had on U.S. policy toward Iraq at the time.51 Former vice chairman of the U.S. National Intelligence Council Gregory F. Treverton considered Chalabi and his INC key contributors of “rotten” intelligence during the period.52

Robert U. “Bob” Woodward’s 2004 book Plan of Attack provided deeper insight into the INC’s sway over U.S. politics, but at the time of publication very little was known of the group’s role as a source for prominent American journalists. In June of that year, The New Yorker chief Washington correspondent Jane M. Mayer published a meticulously detailed investigation of Chalabi entitled “The Manipulator,” which shed new light on the role that externals played in building the invasion consensus through Western government officials and news media. Author Thomas E. Ricks parsed through some of this information and revealed the INC’s additional connections to journalists two years later in his history of the Iraq War, Fiasco: The American Military Adventure in Iraq. Notably, a core theme of Ricks’ book was the disproportionate influence that U.S. media reports had on political assumptions in Washington.53 His point has merit. To convey the sense of urgency to deal with Iraq in 2002, Doug Feith begins the chapter in his memoir entitled “Why Iraq” by citing a slew of news articles covering the growing public mandate to disarm Saddam Hussein.54

The Pitch

After 9/11, journalists and U.S. officials received a stream of false information from Iraqi exiles offering to fill the intelligence void regarding Hussein’s WMD aspirations and connections to al-Qaeda. Some even confessed to fabricating information based on what they saw in Western news reports.55 Perhaps the most well-known Iraqi defector, Rafid Ahmed Alwan al-Janabi, who went by the code name “Curveball,” proved to be a source of disinformation, but only after his testimony wound up in U.S. secretary of state Colin L. Powell’s 5 February 2003 speech to the UN Security Council in which he sold the case for taking military action against Hussein.56

Alwan was an Iraqi chemical engineer and German Federal Intelligence Service (BND) asset who began leaking information around the same time that the Clinton administration passed the Iraq Liberation Act in 1998. He provided what seemed like plausible intelligence regarding mobile biological weapons facilities in Iraq, but the BND eventually labeled him an insane “fabricator.”57 The Los Angeles Times later reported that Alwan was a brother to one of Chalabi’s top aides, which underscores the INC network’s role as intelligence broker leading up to 2003.58 Some have since downplayed this connection, but George Tenet admitted that the CIA depended “heavily” on Alwan’s information.59 A former CIA officer affirmed the INC-Alwan connection, telling The New Yorker in 2004 that he was “positive” the INC introduced Alwan to the German intelligence community.60 Moreover, one of the earliest public mentions of Iraq’s WMD threat came from a Chalabi acquaintance only three months after the 9/11 attacks.

In a New York Times article published on 20 December 2001, Judith Miller cited Iraqi defector Adnan Ihsan Saeed al-Haideri, who claimed that he had personally worked on “secret facilities for biological, chemical and nuclear weapons [in Iraq]” and had visited at least 20 such sites personally.61 The fact that this testimony was completely false did not stop articles like this from inspiring at least one Iraqi general to tell U.S. officials what he thought they wanted to hear regarding Saddam’s supposed nuclear program.62

Chalabi admitted to serving as al-Haideri’s handler and introducing him to U.S. government officials and journalists at The New York Times and The Washington Post in December 2001.63 Throughout that year, major Western news outlets continued a pattern of citing Iraqi defectors and anonymous U.S. officials who doubled down on reports of a sophisticated WMD architecture in Iraq.64 Chalabi connected U.S. officials to prominent Iraqi defectors when human intelligence was severely lacking.

In 1998, Hussein had kicked UN weapons inspectors out of Iraq, removing the CIA’s WMD sources and leaving them blind in Baghdad. Coincidentally, that same year Alwan began leaking fictional intelligence to the BND. This made Chalabi and Alwan’s supposed insider access indispensable because it satisfied an intelligence deficit through the tyranny of supply and demand for information related to Hussein’s activities.65 As a result, U.S. vice president Richard B. “Dick” Cheney and U.S. secretary of defense Donald H. Rumsfeld publicly declared their certainty that Hussein had WMDs and intended to share them with terrorists.66

Later histories of the road to the Iraq War, such as Tom Basile’s Tough Sell: Fighting the Media War in Iraq, mention the INC only sparingly but highlight that Chalabi played a role in convincing the Bush administration that Iraq was primed for a “new, secular, democratic” future once Hussein had been removed.67 This fit the Bush administration’s well-known doctrine of democratizing the Middle East perfectly. Colin Powell’s February 2003 speech at the UN Security Council, which presented evidence of Iraq’s biological warfare units, provided the last nudge needed to bring doubters over to the invasion camp.68 To his credit, Powell was skeptical. He insisted that WMD intelligence from Chalabi or the INC be removed from his speech, but the INC’s net was so wide that this became all but impossible.69 The 2004 report by the Senate Select Committee on Intelligence identified four human intelligence sources who the U.S. intelligence community relied on to draw the conclusions included in Powell’s speech. Two of the sources were redacted; the other two were Alwan and an unnamed INC source.70

Mission Accomplished

Admittedly, every false statement from externals was not necessarily linked to a broader, calculated plan to deceive U.S. officials. Some informants may have been desperate for extrication from Iraq or for leniency from the United States after the invasion began and therefore echoed to their handlers what they read in the news and likely heard from other exiles. That said, it seems highly unlikely that Alwan and Chalabi, with no external coordination or sources of information, could have stitched together a narrative so convincing that it deceived multiple Western intelligence agencies, especially considering the degree of specificity included in some of their allegations.71 One DIA officer who debriefed an INC source in March 2002 believed that “the source had been coached on what information to provide.”72 By May, the U.S. intelligence community flagged the source as unreliable, yet his testimony still appeared in the July 2002 National Intelligence Estimate and in Powell’s speech the following year.73

The precise threshold that swayed the final decision to invade Iraq is hard to pinpoint, and it certainly was not George Tenet’s December 2002 “slam dunk” comment made in the Oval Office that appeared out of context in Bob Woodward’s 2004 book and ultimately prompted the CIA director to resign.74 As for the claims by Alwan and al-Haideri, Tenet appointed former UN weapons inspector David A. Kay to investigate the presence of WMD in Iraq after the invasion. Kay discovered several facilities designed for chemical and biological research that clearly violated UN Security Council Resolution 1441, but no active programs nor weapons.75 Abandoned Cold War stockpiles of chemical munitions that U.S. servicemembers encountered in Iraq were made public in 2014, but they did little to vindicate the intelligence used to support the invasion.76 Former CIA officer Vincent Cannistraro put it bluntly in 2004: “With Chalabi, we paid to fool ourselves.”77

For some reason, Alwan agreed to reveal his identity during a 60 Minutes interview with television correspondent Robert D. “Bob” Simon in 2011—the same year the United States halted combat operations in Iraq. During the exchange, Alwan admitted to fabricating everything he told the BND. When Simon asked Alwan if he was motivated by the idea of destroying Saddam Hussein, Alwan responded with one word: “Exactly.”78

Is the West Primed for Another “Curveball”?

The gift of hindsight is a welcome privilege, but it is one not afforded to today’s analysts as they toil to extract clarity from an increasingly broad but shallow information environment. An October 2022 Pew Research Center survey revealed that trust in social media information among adults under 30 years of age was at its highest level yet, but trust in national news media within the same demographic was at its lowest.79 Disturbingly, the number of young Americans who get their news from the Chinese-owned TikTok application tripled from 3 percent in 2020 to 10 percent in 2022.80 The explosion of unrefereed blogs and other online sites posing as venues of scholarly inquiry during the last decade contributed to this phenomenon, but newspapers are not without fault.

Adolf Hitler, Benito Mussolini, and more recently, Sirajuddin Haqqani, one of the world’s most wanted terrorists, all penned essays in the opinion pages of major U.S. newspapers at pivotal moments in history.81 Haqqani, who is now a senior official in Afghanistan’s Taliban-run government, wrote a 2020 editorial for The New York Times that was laden with disinformation intended to soften international resistance to Taliban rule in Afghanistan. Perhaps most ironically, Hitler’s 1941 editorial in The New York Times was titled “The Art of Propaganda.”82 Ubiquitous smart devices now supercharge these trends with perpetual information dumps curated to please one’s existing biases instead of challenging one’s thinking.83 Deepfake videos and synthetic voice audio have become so realistic that a well-timed release of fake news using such technologies could lead to vast social destabilization before governments or OSINT analysts can confirm its veracity.84 In such an environment, being first has surpassed the need to be right.

Meanwhile, OSINT is rightfully becoming more relevant to the global intelligence community.85 From initiatives such as the OSINT Foundation to the Ukrainian Army’s lethal exploitation of the trade against Russia, governments are realizing that a sensor-drenched world provides endless opportunities for OSINT practitioners.86 Open-source research groups and companies such as the Institute for the Study of War, Bellingcat, and CrowdStrike have provided some of the most groundbreaking analysis on topics ranging from alleged war crimes in Ukraine to foreign espionage in the United States.87 The 2023 NDAA authorized numerous OSINT directives, including a director of national intelligence-led pilot program for screening foreign investments and an intelligence community working group that reports on China’s “economic and technological activities” using OSINT.88

One of the more prominent recent examples of the value of OSINT was the U.S. intelligence community’s role in raising awareness vis a vis Russia’s military aggression toward Ukraine in 2021–22. As a preemptive strike against potential Russian disinformation in the weeks leading up to the February 2022 invasion, the U.S. government rapidly declassified intelligence related to Vladimir Putin’s intent to invade Ukraine. These declassifications understandably consumed trusted media headlines and the analysis of foreign policy experts.89 While this approach proved somewhat effective in this case, critics such as Thomas Rid of Johns Hopkins University highlighted the associated risk of exaggerating the impact of disinformation through overly aggressive intelligence declassification.90 After all, injecting developing or incomplete intelligence into the public sphere is precisely what built a false consensus around invading Iraq in 2003. Accuracy and patience, therefore, are key to deterring the next “Curveball” and protecting the United States against the growing threat of foreign disinformation.

Distilling the Problem: A Way Forward

The irony of this article is that it highlights the risk of open-source reports while citing them as supporting evidence. This is inevitable because the use of publicly available information to promote understanding is a necessary function of a free society. Unfortunately, after 2016 the disinformation conversation in the United States has been politicized at a time when it is most critical that free societies band together in resistance to coordinated lies.91 This makes it much harder for those studying, or tasked with countering, disinformation to broach the topic with all strata of society without invoking what might resemble polemically charged rhetoric.

Even so, the U.S. intelligence community and DOD could certainly do a better job of using existing mechanisms within the U.S. education system and news media to encourage critical thought related to information sourcing and consumption. Such initiatives might yield greater returns on investment than new federal bureaucracies to serve as arbiters of truth, such as the U.S. Department of Homeland Security’s short-lived Disinformation Governance Board.92 The core issues driving the challenges examined in this article, however, stem from the relationship between intelligence collection, analysis, and consumption.

After 9/11 and the WMD fiasco, the intelligence community became a convenient punching bag for other agencies and officials looking to avoid blame. Debate continues about whether the 2003 invasion of Iraq was a policy vice intelligence failure, but there is no doubt that the intelligence community erred regarding WMDs, a fault to which George Tenet conceded.93 The 2004 report by the Senate Select Committee on Intelligence criticized groupthink in the analytical profession, which gave rise to soul searching regarding best practices.94 While such criticism is fair, the problems identified in this article are more complex than simply improving structured analytic techniques.95

The lack of intelligence collection in Iraq after 9/11—specifically regarding Saddam Hussein’s WMD programs—created a house-of-mirrors effect in which Western media and intelligence inadvertently corroborated and amplified information related to those gaps. Iraqi externals understandably exploited that shortfall. Analysts can only process what has been collected, and if collecting against certain requirements in Iraq was not possible or not a priority before 9/11, the intelligence community could hardly establish the complex framework necessary to collect decisively against such emerging requirements afterward. This speaks to the importance of a robust presence of human sensors in peacetime—such as special operations forces and military advisors—to maintain critical human networks and set conditions for contingencies.96

Admittedly, improving the scope of intelligence collection and developing superior analysts who are unmoved by headlines is not enough because, as research analyst Peter Mattis observed in 2016, “intelligence is not about its producers but rather its users.”97 Much has been written about the need to divorce politics from intelligence, but this is a pipe dream.98 If Prussian military theorist Carl von Clausewitz was correct in his observation that war is a continuation of policy by other means, so too is intelligence. Whether viewed through the lens of Samuel P. Huntington’s subjective or objective control mechanisms, civil-military relations in the United States are founded in civilian control of the nation’s military and intelligence apparatuses.99 Gregory Treverton’s 2008 prognosis still rings true: “intelligence will become more political even if it is not more politicized” because U.S. presidential administrations require security estimates to legitimize their policies.100

This places the burden of prudence on the consumers of intelligence as much as the producers. In the wake of 9/11, there was immense pressure to produce suitable assessments based on the policy convictions of the current administration—an enduring challenge that intelligence scholars have toiled over for the last 20 years.101 Emerging technologies will make confirmation bias even more appealing in the coming years, as the resources available to those directing collection requirements expands. Intelligence officers owe their principals candid or even blunt counsel regarding the limitations of intelligence, and those principals must be willing to challenge the assumptions buttressing their policies in response. Further even, leaders should seek out such limitations from their intelligence advisors vigorously.

In a world where societies are having a harder time discerning fact from fiction, the danger of malign actors helping Western officials find what they are looking for even though it might not be true is worth deeper reflection. As war rages in Europe and tensions rise in Asia, it is crucial to remember that nations, groups, and individuals have unique interests that might conflict with those of the United States’ adversaries but not necessarily coincide with the strategic interests of the United States. While the U.S. Joint force continues to seek partners in support of Ukraine’s defense and to compete with the Chinese Communist Party, it must be cautious to avoid falling into similar groupthink sinkholes by recognizing that the enemy of one’s enemy is not always one’s friend.102

Conclusion

The United States’ WMD controversy was a crisis of its own making that was rooted as much in policies that preceded 9/11 as those that followed. Al-Qaeda’s attacks on the United States merely gave enterprising actors an opportunity to accelerate the timeline for Saddam Hussein’s removal from power, which began with the founding of the INC in 1992 and continued with the Iraq Liberation Act of 1998 codifying regime change in Baghdad into public law. Intelligence scarcities surrounding Iraq’s WMD program sparked the curiosity of journalists and public officials, which in turn caused Iraqi exiles to exploit this vulnerability in pursuit of a shared objective: the overthrow of Hussein. The Senate Select Committee on Intelligence found that justification for the Iraq War was based on incomplete or false intelligence, and President Bush admitted the same in 2005.103 All of these faults did not originate from the camp of externals, but some certainly did, and they made their way into official reports and trusted newspapers that shaped policy.

This assessment is a sobering reminder that disinformation from foreign media outlets and internet bots is not the only threat to understanding in the Information Age. Misleading narratives might not appear in a way that can be easily verified by trusted public sources or identified by the public. Recognizing this is not akin to casting judgment on those burdened with reporting and making policy decisions in the shadow of 9/11—an unprecedented moment in history—but it should serve as a reminder of truth’s complexity even before the age of supercharged disinformation.104

The modern information environment is now characterized by an increased reliance on social media news, less deep reading, faster information consumption, sophisticated deepfakes, and lifelike simulation, all while OSINT becomes more important to how the public sees the world and how the U.S. Joint force competes with adversaries and wages war. As the pace of information and warfare increase concomitantly, OSINT will become more important because it has the potential to flatten lines of communication between friendly nations in peace and war.105 This revolution carries inherent risk that leaders must manage, as this article indicates.

Promoting awareness of disinformation’s intricacy in academia and Western news media could help build resiliency and encourage greater critical thought within American society. Continuing to refine collection methods and priorities and improve analytical methodologies are also worthy endeavors. Most importantly, intelligence consumers must resist the urge to stretch intelligence in support of their policies instead of crafting policies supported by the intelligence. As OSINT becomes more prevalent and the information environment evolves into an increasingly opaque battlefield, those entrusted with the nation’s secrets must keep the lessons of Iraq in the forefront of their minds. Indeed, lives depend on them doing so.

Endnotes

- National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2015, Pub. L. No. 113-291 (2014).

- Arijeta Lajka and Philip Marcelo, “Fake AI Images of Putin, Trump Being Arrested Spread Online,” PBS, 23 March 2023; and “Fact Check: Videogame Footage Superimposed with News Banner on Russia-Ukraine Tensions,” Reuters, 17 February 2022. The sophistication of video game footage that some mistook for Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in February 2022 pales in comparison to the near-lifelike realism of processing software such as Epic Games’ Unreal Engine 5.2.

- OSINT was critical to Ukraine’s battlefield success in 2022, a point not lost on Western military institutions. Yagil Henkin, “The ‘Big Three’ Revisited: Initial Lessons from 200 Days of War in Ukraine,” Expeditions with MCUP (1 November 2022), https://doi.org/10.36304/ExpwMCUP.2022.13; and Peter W. Singer, “One Year In: What Are the Lessons from Ukraine for the Future of War?,” Defense One, 22 February 2023.

- Bob Drogin, Curveball: Spies, Lies, and the Con Man Who Caused a War (New York: Random House, 2007).

- Joshua Kameel, “The Iraq War,” American Intelligence Journal 32, no. 1 (2015): 79–86.

- Calder Walton, “What’s Old Is New Again: Cold War Lessons for Countering Disinformation,” Texas National Security Review 5, no. 4 (Fall 2022): 49–72, http://dx.doi.org/10.26153/tsw/43940; and Adam B. Ulam, Expansion and Coexistence: Soviet Foreign Policy, 1917–1973, 2d ed. (New York: Praeger, 1974), 111–25.

- This directorate began as a department in the 1950s before it was upgraded to a service and placed under a KGB general in the 1970s with the title of first chief directorate, service A (for active measures). This is the equivalent of the United States appointing a military Service-level chief of staff of deception. Dennis Kux, “Soviet Active Measures and Disinformation: Overview and Assessment,” Parameters 15, no. 1 (1985): 19–28, https://doi.org/10.55540/0031-1723.1388.

- Mark M. Lowenthal, “Intelligence in Transition: Analysis after September 11 and Iraq,” in Analyzing Intelligence: Origins, Obstacles, and Innovations, ed. Roger Z. George and James B. Bruce (Washington, DC: Georgetown University Press, 2008), 227.

- Russ Hoyle, Going to War: How Misinformation, Disinformation, and Arrogance Led America into Iraq (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 2008).

- Abdel Bari Atwan, Islamic State: The Digital Caliphate (Oakland: University of California Press, 2015); and 1stLt Michael P. Ferguson, USA, “The Mission Command of Islamic State: Deconstructing the Myth of Lone Wolves in the Deep Fight,” Military Review (September–October 2017): 68–77.

- Alexander Lanoszka, “Disinformation in International Politics,” European Journal of International Security 4, no. 2 (2019): 227–48, https://doi.org/10.1017/eis.2019.6. 1

- Brian G. Southwell, Emily A. Thorson, and Laura Sheble, eds., Misinformation and Mass Audiences (Austin: University of Texas Press, 2018), https://doi.org/10.7560/314555.

- Thomas Rid, Active Measures: The Secret History of Disinformation and Political Warfare (New York: Picador, 2020); Peter Pomerantsev, This Is Not Propaganda: Adventures in the War against Reality (New York: Public Affairs, 2019); Cailin O’Connor and James Owen Weatherall, The Misinformation Age: How False Beliefs Spread (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2019); Moisés Naím, The Revenge of Power: How Autocrats Are Reinventing Politics for the 21st Century (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 2022); Natalie Grant, Disinformation: Soviet Political Warfare, 1917–1992 (Washington, DC: Leopolis Press, 2020); and Donald A. Barclay, Disinformation: The Nature of Facts and Lies in the Post-Truth Era (London: Rowman & Littlefield, 2022).

- Pamela Madrid, “USC Study Reveals the Key Reason Why Fake News Spreads on Social Media,” USC News, 17 January 2023.

- Samantha Bradshaw and Philip N. Howard, The Global Disinformation Disorder: 2019 Global Inventory of Organised Social Media Manipulation (Oxford, UK: Computational Propaganda Project, Oxford Internet Institute, University of Oxford, 2019).

- Lev Topor and Alexander Tabachnik, “Russian Cyber Information Warfare: International Distribution and Domestic Control,” Journal of Advanced Military Studies 12, no. 1 (Spring 2021): 112–27, https://doi.org/10.21140/mcuj.20211201005.

- David L. Altheide and Jennifer N. Grimes, “War Programming: The Propaganda Project and the Iraq War,” Sociological Quarterly 46, no. 4 (Autumn 2005): 617–43.

- Gregory Asmolov is one exception. He provides a fascinating analysis of the potential for digital antidisinformation campaigns to be abused by governments. Gregory Asmolov, “The Disconnective Power of Disinformation Campaigns,” Journal of International Affairs 71, no. 1.5 (2018): 69–76. For analysis of the role that U.S. news media played in fueling the Iraq War, see Danny Hayes, “Whose Views Made the News?: Media Coverage and the March to War in Iraq,” Political Communication 27, no. 1 (2010): 59–87, https://doi.org/10.1080/10584600903502615.

- Mohamed ElBaradei dismissed U.S. secretary of state Colin Powell’s 2003 claims made to the UN security council. Thomas E. Ricks, Fiasco: The American Military Adventure in Iraq (New York: Penguin, 2006), 407; and Hoyle, Going to War, 310.

- Peter Dizikes, “The Catch to Putting Warning Labels on Fake News,” MIT News, 2 March 2020.

- Jonathan Haidt and Eric Schmidt, “AI is About to Make Social Media (Much) More Toxic,” Atlantic, 5 May 2023.

- Brian J. Murphy, “In Defense of Disinformation,” Journal of Homeland Security and Emergency Management 20, no. 3 (2023), https://doi.org/10.1515/jhsem-2022-0045.

- Michael P. Ferguson, “Welcome to the Disinformation Game—You’re Late,” Strategy Bridge, 29 August 2018; and Michael P. Ferguson, “The Evolution of Disinformation: How Public Opinion Became Proxy,” Strategy Bridge, 14 January 2020.

- New York Times Co. v. Sullivan, 376 U.S. 254 (1964).

- Imparting or Conveying False Information, 18 U.S. Code § 35 (1956).

- A Human Rights Approach to Tackle Disinformation (London: Amnesty International, 2022), 4–10.

- Numerous studies have concluded that Russia’s efforts did not have a measurable impact on election results. For example, see Alan I. Abramowitz, “Did Russian Interference Affect the 2016 Election Results?,” Center for Politics, University of Virginia, 8 August 2019.

- The Camp David meeting took place on 15 September 2001. Condoleezza Rice, No Higher Honor: A Memoir of My Years in Washington (New York: Crown Publishers, 2011), 86–87.

- Michael R. Gordon and Bernard E. Trainor, The Endgame: The Inside Story of the Struggle for Iraq, from George W. Bush to Barrack Obama (New York: Vintage Books, 2012), 29.

- Select Committee on Intelligence, “Report on the U.S. Intelligence Community’s Prewar Intelligence Assessments on Iraq,” S. Rep. No. 108-301 (2004), hereafter Select Committee on Intelligence report (2004).

- Ricks, Fiasco, 56.

- The Defense Policy Board advised U.S. secretary of defense Donald Rumsfeld and was chaired by Richard N. Perle. Jane Mayer, “The Manipulator,” New Yorker, 30 May 2004.

- Douglas J. Feith, War and Decision: Inside the Pentagon at the Dawn of the War on Terrorism (New York: HarperCollins, 2008), 243.

- James J. F. Forest, “Political Warfare and Propaganda: An Introduction,” Journal of Advanced Military Studies 12, no. 1 (Spring 2021): 20, https://doi.org/10.21140/mcuj.20211201001.

- George W. Bush, “President Bush Delivers Graduation Speech at West Point,” White House Archives, 1 June 2002.

- “The Bush Assassination Attempt: FBI Labs Report,” U.S. Department of Justice, accessed 9 April 2023.

- The April 2001 meeting between 9/11 hijacker Mohamed Atta and Iraqi intelligence chief Ahmad Samir al-Ani in Prague, Czech Republic, was a key piece of intelligence used to prop up this assessment. A string of reports from years prior outlining Iraq’s intentions to strike U.S. targets in the region supported the theory. Still, the U.S. intelligence community had no “credible information that Baghdad had foreknowledge of the 11 September attacks or any other al-Qaida strike.” Saddam Hussein executed both Shia and Sunni extremists and reports suggested his regime discouraged Iraqi youth from joining al-Qaeda. Select Committee on Intelligence report (2004), 309–18, 321–30.

- Perle was an influential advisor to U.S. secretary of defense Donald Rumsfeld and chairman of the Defense Policy Board from 2001 to 2003. Albert L. Weeks, The Choice of War: The Iraq War and the “Just War” Tradition (Santa Barbara, CA: Praeger Security International, 2010), 47.

- Gordon and Trainor, The Endgame, 78.

- The CIA helped develop the INC in 1992 but ultimately found Chalabi to be an “unreliable partner.” George Tenet, At the Center of the Storm: My Years at the CIA (New York: HarperCollins, 2007), 397.

- This began with the threat of force, continued with the possibility of destroying “suspected sites,” and ended in a near decade-long war. Feith, War and Decision, 181–82.

- Iraq Liberation Act of 1998, Pub. L. No. 105-338, 112 Stat. 2151 (1998).

- Daniel Byman, “After the Storm: U.S. Policy toward Iraq since 1991,” Political Science Quarterly 115, no. 4 (Winter 2000–1): 493–516, https://doi.org/10.2307/2657607.

- The Senate report found that the “raw intelligence reporting from the CIA detailed the questionable nature of reporting by countries or groups that clearly opposed the Iraqi regime.” Select Committee on Intelligence report (2004), 326. See also Ronald Kessler, The CIA at War: Inside the Secret Campaign against Terror (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 2003), 294.

- Select Committee on Intelligence report (2004), 308.

- Despite his vociferous praise for Chalabi and insistence that he played an essential role in the invasion of Iraq and subsequent war, Feith maintains that Chalabi never “shaped” U.S. policy. Feith, War and Decision, 190, 197, 243, 487–88. Chalabi, however, saw things differently, as quoted in Mayer, “The Manipulator.”

- Feith believed that the CIA disliked Chalabi because they could not control him. Feith, War and Decision, 190–91.

- This CIA officer’s name was Robert Baer. Kessler, CIA at War, 266–69; and Mayer, “The Manipulator.”

- Kessler, CIA at War, 268.

- George W. Bush, Decision Points (New York: Crown, 2010), 259.

- Gordon and Trainor, The Endgame, 47. Feith attributed the Michael Jordan quote to deputy U.S. national security advisor Robert D. Blackwill. Feith, War and Decision, 487.

- According to Treverton, externals created opportunities to “cherry-pick” intelligence related to Iraq’s WMD program. Gregory F. Treverton, “Intelligence Analysis: Between ‘Politicization’ and Irrelevance,” in Analyzing Intelligence: Origins, Obstacles, and Innovations, ed. Roger Z. George and James B. Bruce (Washington, DC: Georgetown University Press, 2008), 95–96.

- Ricks described how media reports influenced the thinking of mid-level and even senior intelligence officials because they often claimed to reflect the candid views of those in higher levels of authority. Ricks, Fiasco, 91–92.

- Feith, War and Decision, 182–83. In addition to Feith’s take, a 10 February 2003 Congressional Research Service report on U.S. regime change policy toward Iraq was littered with references to major news outlets. Chalabi and the INC take up several pages of the document. See Kenneth Katzman, Iraq: U.S. Regime Change Efforts and Post-Saddam Governance (Washington, DC: Congressional Research Service, 2003).

- For example, Iraqi nuclear scientist Khidir Hamza trumped up Iraq’s nuclear programs throughout the 1990s. Between November 2001 and February 2002, defected Iraqi intelligence officer Abu Zeinab al-Qurairy and Khalifa Khodada al-Lami falsely connected Iraq to al-Qaeda and 9/11 through the Salman Pak terrorist camp and meetings between 9/11 planner Mohamed Atta and Iraqi intelligence officers. The INC supposedly handled al-Qurairy. See David Rose, “Inside Saddam’s Terror Regime,” Vanity Fair, February 2002, 122–23, 135–38; Mayer, “The Manipulator”; Weeks, The Choice of War, 59; and Select Committee on Intelligence report (2004), 330.

- Tenet, Center of the Storm, 373–80; and Weeks, The Choice of War, 67, 72–73.

- Kessler, CIA at War, 295–96; and Tenet, Center of the Storm, 377.

- Ricks, Fiasco, 91.

- Tenet, Center of the Storm, 380.

- This quote is attributed to Vincent Cannistraro. Mayer, “The Manipulator.”

- Judith Miller, “A Nation Challenged: Secret Sites; Iraqi Tells of Renovations at Sites for Chemical and Nuclear Arms,” New York Times, 20 December 2001. See also Ricks, Fiasco, 35.

- Samuel Helfont, “The Iraq War’s Intelligence Failures Are Still Misunderstood,” War on the Rocks, 28 March 2023.

- Ricks, Fiasco, 56.

- Among these stories was the controversy over Iraq’s intended acquisition of yellow cake from Africa, a substance used in the uranium enrichment process. Although the CIA saw this intelligence as incomplete, it found its way into the news, and Tenet had to later remove yellow cake references from Powell’s 2003 speech to the United Nations. Walter H. Pincus of The Washington Post won a Pulitzer Prize for his reporting on the issue. Dana Priest, “Uranium Claim Was Known for Months to Be Weak,” Washington Post, 20 July 2003; and Tenet, Center of the Storm, 373–74, 453–55.

- Tommy Franks, American Soldier (New York: HarperCollins, 2004), 421.

- Ricks, Fiasco, 49–51.

- Tom Basile, Tough Sell: Fighting the Media War in Iraq (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2017), 212.

- “Secretary Powell at the UN: Iraq’s Failure to Disarm,” U.S. Department of State Archive, 5 February 2003. Powell later expressed regret for this speech. Ricks, Fiasco, 93–94, 407.

- Hoyle, Going to War, 324–25.

- Select Committee on Intelligence report (2004), 149, 152.

- Such allegations include, for example, the name of an Iraqi scientist who Alwan falsely claimed ran a biological weapons site and the locations and composition of certain facilities in Iraq. Alwan said a friend loaned him money to travel and solicit this information. See Bob Simon, “ ‘Curve Ball’ Speaks out,” CBS News, 13 March 2011, YouTube video, 2:40.

- Select Committee on Intelligence report (2004), 160.

- Select Committee on Intelligence report (2004), 161.

- Bipartisan support for the use of military force against Hussein existed before this comment, with some public officials, such as then-Senator Joseph R. Biden Jr., even calling for unilateral action. Tenet, Center of the Storm, 361–65.

- UN Security Council, Resolution 1441, The Situation between Iraq and Kuwait, S/RES/1441 (8 November 2002); and Kessler, CIA at War, 331–33. In addition, the presidential panel tasked with looking into Iraq intelligence failures known as the 2005 Silberman-Robb Commission declared information from Alwan unreliable.

- After all, the world knew that Saddam Hussein had chemical weapons because he used them on his own people. See C. J. Chivers, “The Secret Casualties of Iraq’s Abandoned Chemical Weapons,” New York Times, 14 October 2014.

- Mayer, “The Manipulator.”

- Simon asked if the story Alwan sold about Iraq’s weapons program was true, and Alwan responded, “No, not at all.” When pressed to divulge if someone put him up to the plot, Alwan walked out of the interview. Simon, “ ‘Curve Ball’ Speaks Out,” 1:40.

- Jacob Liedke and Jeffrey Gottfried, “U.S. Adults under 30 Now Trust Information from Social Media Almost as Much as from National News Outlets,” Pew Research Center, 27 October 2022. See also Megan Brenan, “Americans’ Trust in Media Remains Near Record Low,” Gallup, 18 October 2022.

- Katerina Eva Matsa, “More Americans Are Getting News on TikTok, Bucking the Trend on Other Social Media Sites,” Pew Research Center, 21 October 2022. 8

- Haqqani’s opinion piece aimed to convince the world that the Taliban had adopted a more moderate version of its draconian political system that oppressed women. It had not. See Sirajuddin Haqqani, “What We, the Taliban, Want,” New York Times, 20 February 2020. For a counterpoint, see Michael P. Ferguson, “The Taliban Didn’t Change—It Adapted to the (Dis)information Age,” Hill, 27 September 2021.

- Adolf Hitler, “The Art of Propaganda,” New York Times, 22 June 1941.

- For more on the origins of this phenomenon, see Eli Pariser, The Filter Bubble: How the New Personalized Web Is Changing What We Read and How We Think (New York: Penguin Books, 2012); and Nicholas Carr, The Shallows: What the Internet Is Doing to Our Brains (New York: W. W. Norton, 2010).

- Artificial intelligence can generate podcasts that are indiscernible from a real show. The potential for such technology to deceive, especially in communities with limited access to credible sources of information, is profound. See “Watch: Completely AI-Generated Joe Rogan Podcast with OpenAI CEO Sam Altman,” Yahoo News, 12 April 2023.

- Byron Tau and Dustin Volz, “Defense Intelligence Agency Expected to Lead Military’s Use of ‘Open Source’ Data,” Wall Street Journal, 10 December 2021.

- Vanessa Roberts, ed., Executive Survey: The Growing Role of Open Source Intelligence in National Security Strategy (Washington, DC: Federal News Network, 2022).

- Eliot Higgins, “How Open Source Evidence Was Upheld in a Human Rights Court,” Bellingcat, 28 March 2023.

- National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2023, Pub. L. No 117-263, 136 Stat. 2395 (2022).

- Huw Dylan and Thomas J. Maguire, “Secret Intelligence and Public Diplomacy in the Ukraine War,” Survival 64, no. 4 (2022): 33–74, https://doi.org/10.1080/00396338.2022.2103257.

- Philip Elliott, “Why the CIA Director Is Declassifying Material on Russia’s Ukraine Plot,” Time, 16 February 2022.

- Oliver Boyd-Barrett, “Fake News and ‘RussiaGate’ Discourses: Propaganda in the Post-Truth Era,” Journalism 20, no. 1 (2019): 87–91, https://doi.org/10.1177/1464884918806735.

- “Following HSAC Recommendation, DHS Terminates Disinformation Governance Board,” U.S. Department of Homeland Security, 24 August 2022.

- Scott Lucas, “Recognising Politicization: The CIA and the Path to the 2003 War in Iraq,” Intelligence and National Security 26, no. 2-3 (2011): 203–27, https://doi.org/10.1080/02684527.2011.559141.

- Mark M. Lowenthal, Intelligence: From Secrets to Policy, 4th ed. (Washington, DC: CQ Press, 2009), 125.

- Welton Chang et al., “Restructuring Structured Analytic Techniques in Intelligence,” Intelligence and National Security 33, no. 3 (2018): 337–56, https://doi.org/10.1080/02684527.2017.1400230.

- Maintaining such a global footprint would also support the vision outlined in the U.S. Defense Department’s new Joint Concept for Competing. See Joint Concept for Competing (Washington, DC: Joint Chiefs of Staff, 2023).

- Peter Mattis, “Why Tradecraft Will Not Save Intelligence Analysis,” War on the Rocks, 17 June 2016.

- See, for instance, Treverton, “Intelligence Analysis,” 91–104.

- Samuel P. Huntington, The Soldier and the State: The Theory and Politics of Civil-Military Relations (Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press, an imprint of Harvard University Press, 1957), 80–97.

- Treverton, “Intelligence Analysis,” 92.

- Lowenthal, “Intelligence in Transition,” 235; and John C. Gannon, “Managing Analysis in the Information Age,” in Analyzing Intelligence: Origins, Obstacles, and Innovations, ed. Roger Z. George and James B. Bruce (Washington, DC: Georgetown University Press, 2008), 220–21.

- This proposal challenges elements of realist international relations theory. Zeev Maoz et al., “What Is the Enemy of My Enemy?: Causes and Consequences of Imbalanced International Relations, 1816–2001,” Journal of Politics 69, no. 1 (2007): 100–15, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2508.2007.00497.x.

- Weeks, The Choice of War, 59.

- Josh A. Goldstein and Girish Sastry, “The Coming Age of AI-Powered Propaganda: How to Defend Against Supercharged Disinformation,” Foreign Affairs, 7 April 2023.

- Irene Loewenson, “Over-Classified Information Hampers Work with Allies, Top Marines Say,” Marine Corps Times, 5 April 2023.