Abstract: Japan’s national security identity and its elite strategic culture are at odds with each other, with the former moored to deep-rooted historical legacies and the latter yearning to adapt to contemporary imperatives, including the need to more actively cooperate with the United States in maintaining peace and stability in Asia. How can this tension be overcome? How do defense planners attempt to shape public perceptions of the military’s changing roles in society? And what might their efforts to do so teach us about how they view the desired identity, norms, and values of Japan’s military in relation to the use of force in international disputes?

Keywords: Japan, culture, military, propaganda, manga, militarism, pacifism, identity, security

In the postwar period, Japan’s Self-Defense Force (JSDF) has never engaged in combat operations or been used in coercive dispute settlement abroad, despite the ability and frequent opportunities to do so, and as some argue, the need to. JSDF personnel have therefore never been asked to fight in defense of their country or in the aid of an ally, nor has the Japanese public’s tolerance of combat costs and casualties been tested. Indeed, the Japanese public likes it so and has remained stubbornly opposed to the development of a more “normalized” military characterized by offensive capabilities and the projection of hard power beyond its borders.

At the same time, however, defense planners in Tokyo perceive an increasingly severe security environment facing the nation, with rising regional threats on the one hand and strained strategic alliances on the other.1 In turn, JSDF official missions and mandates have evolved considerably since the end of the Cold War, and most prominently since the Shinzo Abe administration’s doctrine of “proactive peace” beginning in 2012. Yet, the pace of change is slow, especially considering the many attributes enjoyed by Abe that are ostensibly conducive to the rapid development of new security policies.2

Thus, what the Japanese public wants of its defense is not necessarily what the defense establishment thinks is needed in the current security environment. That is, Japan’s national security identity and its elite strategic culture are at odds with each other, with the former moored to deep-rooted historical legacies and the latter yearning to adapt to contemporary imperatives, including the need to more actively cooperate with the United States in maintaining peace and stability in Asia.

How can this tension be overcome? How do defense planners attempt to shape public perceptions of the military’s changing roles in society? And what might their efforts to do so teach us about how they view the desired identity, norms, and values of the JSDF in relation to the use of force?

In this article, we borrow from Jeannie L. Johnson and Matthew T. Berrett’s Cultural Topography Framework to provide insight into the enduring and complex relationship between Japan’s national and strategic cultures. In particular, we analyze how the Ministry of Defense (MOD) uses cultural production in public promotion of the JSDF’s most important yet most elusive task: the use of force in military contingencies.3 These propaganda materials are the marketing performances, practices, and techniques that governments employ in a “one-way monologue” with domestic and international audiences.4 As Johnson and Berrett suggest, such “state propaganda illuminates the identity, norms, and values that the state hopes to achieve, as well as the narrative it hopes will dominate popular perception.”5

In Japan, such materials have been used since the 1990s to communicate to the Japanese public across socioeconomic groups the culture of their military, imbuing the citizenry’s mind with what Sabine Frühstück describes as “a series of civilianizing, familiarizing, trivializing, and spectacularizing messages about the military’s capabilities, roles, and character.”6 And while these promotional materials may at first view appear contradictory, naive, and even childish or kawaii, the stories they tell are serious ones about power, security, and enemies that threaten the Japanese way of life. As such, a great deal about Japan’s national and strategic cultures can be gleaned from examination of such materials, which are culturally and historically specific.

We focus our study on the government’s strategic deployment of manga (graphic novels) in the public representation of JSDF’s identity, norms, values, and perceptual lens as they relate to the use of military force. To do so, we draw on the Cultural Topography Framework in illustrating how the MOD frames the use of military force through the deployment of popular culture cartoons, a medium of communication deeply familiar to the Japanese public. The authors do so through a systematic review of official propaganda materials published by the MOD between 2006 and 2019. The authors choose this period of analysis because it enables them to explore cultural material as produced by the MOD under different government coalitions (the Democratic Party of Japan, 2009–12; Liberal Democratic Party plus Komeito before and thereafter), and under different legal interpretations about Japan’s use of force, as the cabinet made a momentous decision in 2014 to officially reinterpret the constitution to allow Japan to participate in limited collective self-defense such as aiding U.S. forces in combat.7

This article begins with a brief review of the international relations scholarship on Japan’s national security identity and strategic culture, as well as how popular culture has been used in the past as an instrument to communicate narratives about Japan’s military. The third section describes the data and methods and the fourth presents the results of the analysis. The fifth and final section discusses the implications of the results and suggests directions for future avenues of research.

Literature Review

As an economic juggernaut without commensurate defense capabilities, Japan’s postwar security behavior has long puzzled international relations theorists and military scholars.8 The Realist tradition has had a difficult time explaining Japan’s unwillingness to use its military abroad despite intense regional and global security concerns.9 Liberalism, too, has struggled to explain the glacial pace of change in Japan’s security behavior despite considerable change to its political and economic institutions and policies.10 While power and institutions fail to provide sufficient understanding of Japanese postwar security behavior, Constructivist scholars have shed a great deal of light on the topic through examining ideational and cultural forces that imbue and shape Japanese society.11 These forces have been studied primarily at two levels of analysis: the general public’s national security identity and the elites’ strategic culture. Andrew L. Oros describes the difference succinctly within the literature on Japan: while strategic culture seeks to explain the beliefs and behaviors of political leaders, government bureaucrats, and military officers, a national culture or “security identity” is “not limited to strategy developed by political elites but rather is a resilient identity that is politically negotiated and comprises a widely accepted set of principles on the acceptable scope of state practices in the realm of national security.”12 Thus, a security identity enjoys broad legitimacy at the level of the general public while strategic culture is shaped by societal elites. It is difficult if not impossible to understand strategic culture without considering the national culture in which it is embedded, and post–World War II Japan is perhaps the quintessential example of such a case, with large sections of Japanese society staunchly averse to the use of force as a tool of statecraft, while certain segments of elites have long yearned for a more active and powerful military. Some scholars highlight the process by which security identity is interpreted by policy elites, informing and constraining it in democratic societies; this article focuses on the process by which defense planners and government public relations experts seek to catalyze change in Japan’s national identity through the strategic deployment of culture.13 In this formulation, one must bear in mind the broad contours of the state’s security identity in order to understand its strategic culture and how the government goes about negotiating equivalence between the two.

Japan's Security Identity

Thomas U. Berger has argued that Japan’s choice not to pursue military power despite its ability to do so is due to the nation’s culture of “anti-militarism” after World War II.14 Peter J. Katzenstein has shown how Japan’s normative context and comprehensive definitions of security provide important insight into why the country refuses its right to use force in dispute settlement, while Stephanie Lawson and Seiko Tannaka have pointed to Japan’s historical memory of its violent past to explain why the country does not return to a normal military posture, characterized by offensive capabilities and the projection of hard power beyond its borders.15 In Normalizing Japan, Andrew Oros provides a compelling explanation for why Japanese security policy has evolved—or not evolved—due to its “reluctant” security identity, delving into the critical cases of the ban on arms exports, the militarization of outer space, and missile defense cooperation with the United States.16 And, a long list of scholars have argued that Japan’s identity as a “peace state” or “civilian power” describes well the subdued nature and particular formulations of its security policies and military practice, from the Gulf War to international humanitarian assistance and beyond.17 Bhubhindar Singh notes that Japan’s security identity as a peace state has been transitioning to one of an “international state.” This transition is a contested one and is the “ideational battleground” between Japan’s broad public security identity and narrow, elite strategic culture.18

Japan's Strategic Culture

Oros has argued that Japan has had three distinct strategic cultures in the modern era: isolationist (mid-nineteenth century to the late-nineteenth century), imperialist (late-nineteenth century to the mid-twentieth century) and a post– World War II nonmilitarist strategic culture characterized by reluctance to use military power abroad, even in collective self-defense.19 In this third period, Japanese planners developed a “comprehensive” approach to security (sōgō anzen hoshō) that wed defense imperatives with access to resources and markets, but in an entirely different formulation to the strategic culture that had led Japan to acquire such resources through military imperialism.20 It is this most modern iteration of Japan’s strategic culture that is facing pressure to adapt to changing international security realities and domestic political environments.

These pressures have been mounting since the end of the Cold War and have expanded significantly during the past decade. What began as piecemeal changes in response to particular security events in the 1990s, such as the dispatch of minesweepers to the Persian Gulf in 1991 and the deployment to aid the United Nations (UN) peacekeeping mission in Cambodia in 1992, has grown to a much grander debate in Japan about its future security strategy and policies in the twenty-first century.21 This debate has coincided with considerable shifts in the institutions, policies, mission, and mandates of the JSDF. For example, the deployment of approximately 600 JSDF personnel to southern Iraq from 2004 to 2006 was by far the largest and most risky overseas mission for the JSDF in the postwar era, even though the soldiers were in nonconflict zones and under the protection of Dutch and Australian armies.22 Since the Iraq mission, there have been an increasing number of international ventures, including deployment of naval vessels to participate in antipiracy convoy duties off the coast of Somalia beginning in 2009. The adoption of a formal national security strategy in 2013, establishment of a National Security Council (NSC) in 2014, and adoption of new alliance guidelines with the United States in 2015 under the newly established legal right to collective self-defense, all under Prime Minister Shinzo Abe, have intensified interest in the future direction of Japan’s security policy and whether these recent changes indicate a shift in Japan’s strategic culture.23 During the Cold War era, many believed that the actual use of the JSDF for defense purposes was unlikely.24 And although Japan’s security culture will likely continue to show a reluctance to use or develop military power beyond very limited scenarios, as Sado Akihiro has argued, “The JSDF today is at a major turning point . . . undergoing a conversion from an organization founded on the premise that it would not be used to an organization operating on the assumption that it will actually be used.”25 That is, Japan may well be in the midst of a transition from nonmilitarism to a “fourth modern incarnation” of Japan’s strategic culture.26

Popular Culture Deployment as Strategy

To mediate the tension between a nonthreatening yet highly capable and more proactive JSDF, important both in terms of domestic politics and international diplomacy, the Japanese government has and will continue to use a web of affective cultural and entertainment resources—the Creative Industrial Complex (CIC)—to influence public perceptions of Japan’s military establishment.27 The CIC has produced a stunning amount of film, anime, theater, literature, fashion, and other expressive media designed to generate affinity toward the nation’s growing hard power identity and burgeoning military industrial base. Manga, perhaps chief among them and a multibillion-dollar publishing marvel, is an artistic iconography developed in Japan during the nineteenth century and long used by Japan’s political and government establishments as a potent marketing and communication tool.28

Beginning in the early 1970s, state agencies, recognizing the strong commercial success of manga both at home and abroad, collaborated with private firms to produce manga that communicated political, business, literary, and educational information to the public. With this move toward culturally specific communication came a correlative change in how the Japanese citizenry digested their official information. By the mid-1980s, the use of manga as an official communication medium had thoroughly permeated nearly all state-sponsored institutions in Japan, save one—the Self-Defense Forces.29

Long shy of engaging with a critical citizenry and suffering from a negative international public image, Japan’s military had preferred to remained isolated, purposefully slow in employing modern and nontraditional communication techniques. However, as economic hardship in the 1990s reduced Japan’s relative power and influence, and a host of emergent international threats reduced Japan’s sense of security, it became clear to elites in the JSDF and MOD that answers to many important questions facing the nation would need to be answered with a more proactive defense establishment.30

Thus, and as the Cold War theater came to an end, the JSDF and MOD sought to employ private sector creative industries to build avenues of information and knowledge flow to, from, and between the Japanese people and international community toward what Takayoshi Yamamura has described as a strategy to entice “consumption of the military.”31 With the launch of Prince Pickles in 2007, a cartoon and comic series that sought to describe the ideal “journey to peace,” and an MOD initiative to publish official defense white papers in manga format for general consumption, Japan’s military has slowly moved from a position of self-imposed isolation to one of active public engagement. Strategically using the then well-established and normalized popular culture of manga in government propaganda, the JSDF and MOD began to incorporate these cartoons in its recruiting and public relations campaigns in what Sabine Frühstück has described as a two-track effort to pacify and negate its violent war-waging past and potential while also selling its role as a competent protector of Japan.32 While most academic studies have focused on Japan’s popular culture as a strategic instrument of statecraft in relation to soft power, such as initiatives of “Japan Cool,” and on private sector popular culture depictions of the JSDF, relatively little research has been done focusing specifically on government-produced propaganda.33 A valuable exception has been Frühstück’s research program, which has described in great detail manga material in MOD and JSDF promotional campaigns. She observes that these manga constitute “a set of recurring images that dominate public relations material and attempts at self-valorization” and collectively imply that the JSDF is “necessary for everybody’s safety and security; that they are ordinary men and women capable of extraordinary acts; that they are both powerful and carefully tamed; and that they can militarily defend Japan if they absolutely must.”34 She also contends that the trend of an increasingly intimate relationship between the JSDF and popular culture constitutes a type of militarization, but “it is a militarization that already has internalized the multifaceted character of the military as a group capable of caring, rescuing, and building,” in addition to the more ephemeral possibility of one that would use force in dispute settlement or go to war.35 To conclude, then, since the end of the Cold War, the MOD and SDF have used public relations materials in ways that symbolically “disarmed” themselves and shown their military prowess and capability to protect; individuated and personalized servicemembers as ordinary people capable of extraordinary acts; and glamorized their image and sought to align themselves with other state-run agencies (e.g., the police and post office) and globally active armed forces.36

Data and Methodology

This article follows Jeannie L. Johnson’s iteration of the Cultural Topography Framework as a tool for examining what MOD’s use of popular culture propaganda in mediating contestation between the national security identity and elite strategic culture tells us about the government’s changing perceptions of the military’s identity, norms, values, and perceptual lens.37 The scope of analysis is narrowed to a critical issue of strategic interest to policy makers in Japan, the United States, and around the world: Japan’s use of military force in international affairs. The article’s aim is not to offer predictions about how Japan is likely to behave in various contingencies, but instead to better understand how Japanese defense planners seek to portray Japan’s use of force to current and future generations at home and abroad. Based on the Cultural Topography Framework, the following four analytical categories are used as a starting point for analysis of Japan’s use of military force in MOD-produced manga:

1. Identity: the character traits the group assigns to itself and the reputation it pursues.

2. Norms: expected, accepted, and preferred modes of behavior and shared understanding concerning taboos.

3. Values: material or ideational goods that are honored and confer increased status to members (within the group).

4. Perceptual lens: the filter through which this group views the world; the default assumptions that inform its opinion and ideas about specific others.

Importantly, while these four categories represent core features of a particular group, they are not necessarily mutually exhaustive. Indeed, as Johnson points out, “it is the overlap between categories—a cultural trait manifesting itself in multiple ways, as both an aspect of identity and an attendant norm, for instance—that acts as a signal of robustness and helps the researcher narrow down the most salient traits for examination.”38 This article collects and analyzes the MOD official promotional material published on an annual basis since 2006.39 These publications accompany the annual security white paper Defense of Japan (bōei hakusho).40 The official manga covers a breadth of themes, including concrete missions (e.g., protecting Japan from ballistic missiles) and mandates (e.g., peacekeeping operations in Haiti) to policies (e.g., new Japan–U.S. guidelines) and bureaucratic reforms (e.g., the 2016 establishment of the Acquisition, Technology, and Logistics Agency). Common to all the themes identified in the manga is their strong relevance to contemporary developments, either in the security environment or in Japan’s security apparatus. Thus, for example, the 2007 edition focused on Japan’s ballistic missile defense (BMD) system in the aftermath of North Korea’s 2006 missile launches, and the 2015 edition focused on the revision of the U.S.– Japan guidelines and Japan’s role in collective self-defense.41

To address the authors’ research question, a two-step mixed-methods research design is used in analyzing the data. First, the authors used Nvivo’s cluster analysis tool to calculate text similarity by year. The analysis based on the level of textual similarity—the Pearson correlation coefficient—is used to gauge how similar the annual publications are, thus revealing patterns of continuity and change across annual editions. Since all manga publications were roughly similar in length (about 65 pages each), the corpora size variation is controlled. The authors also employ Nvivo’s word frequency query of official manga publications to identify the most frequent words used in the entire text corpora. This enables for the identification of key terms that MOD communicates to the public. The authors then follow with word frequency analysis for selected key words by annual publication in order to identify whether certain words were emphasized while others were not, and if so, when. Second, because cluster analysis and word frequency do not provide context of usage or content description, the authors draw on the Cultural Topography Model in performing document analysis of each publication so as to gain an understanding of how the MOD frames the use of force, as well as the identity, norms, values, and perceptual lens of the JSDF as they relate to the use of force. Below is a list of 12 questions that guided the authors’ analysis. In choosing the relevant questions from Johnson and Berrett’s extensive list, the authors selected those that can shed light on the use of force, defined as using physical strength or capabilities to solve a problem, as well as on the JSDF organizational culture. The authors have revised some of the questions to reflect these points and to cater to the specific Japanese cultural and historical context. For each annual manga publication, the authors considered these 12 questions and recorded the answers in a database for meta-analysis.

Use of Force:

1. Do the JSDF contemplate or use force in the story?

2. If the answer to the previous question was “yes,” what kind of force is contemplated/used?

3. Under what scenarios/against whom does the JSDF contemplate/use military force?

Identity:

4. What character traits are assigned to the JSDF in relation to the use of force?

5. What reputation is assigned to the JSDF in relation to the use of force?

Norms:

6. What are the accepted and expected modes of organizational behavior/ societal behavior in relation to the use of force?

7. What defines victory for this group in a potential or actual conflict or problem?

8. Are allies viewed as reliable or treacherous or in some other fashion?

Values:

9. What is considered honorable behavior in the context of the JSDF’s use of force?

10. What organizational and societal values in relation to the use of force are rewarded as character traits or are considered naive, juvenile, and possibly dangerous? Which character qualities are consistently praised?

Perceptual Lens:

11. How is the threat environment Japan faces depicted?

12. How is the potential or actual enemy’s character depicted?

Findings

Step 1: Cluster Analysis and Word Frequency

Clear patterns of similarity were found between the annual publication of Manga-Style Defense of Japan, with strong correlations (above 0.70) obtained for editions published during the period between 2012 and 2017. Simply put, editions between 2012 and 2017 had a high degree of similarity, yet not so with pre-2012 editions.42 This suggests that between 2012 and 2017 (“Abe years”), the content of manga editions was relatively consistent and differed considerably from content in the 2006–11 years.

Using Nvivo’s word frequency query, the authors first sampled the entire text corpora. The most frequently mentioned word in the text was “defense” (防衛, boei) with its associated terms (protect, guard, defend, and so on), with a weighted percentage of 0.76. The second most frequently mentioned word in the text was “JSDF” with a weighted percentage of 0.52. The third and fourth words were “to conduct” (行う, okonau) and “activities” (活動, katsudou), with weighted percentages of 0.41 for both categories. Other frequently mentioned terms were “air” (航空, 0.31), “support” (支援, 0.28), “duty” (任務, 0.25), and “security” (安全, 0.23).

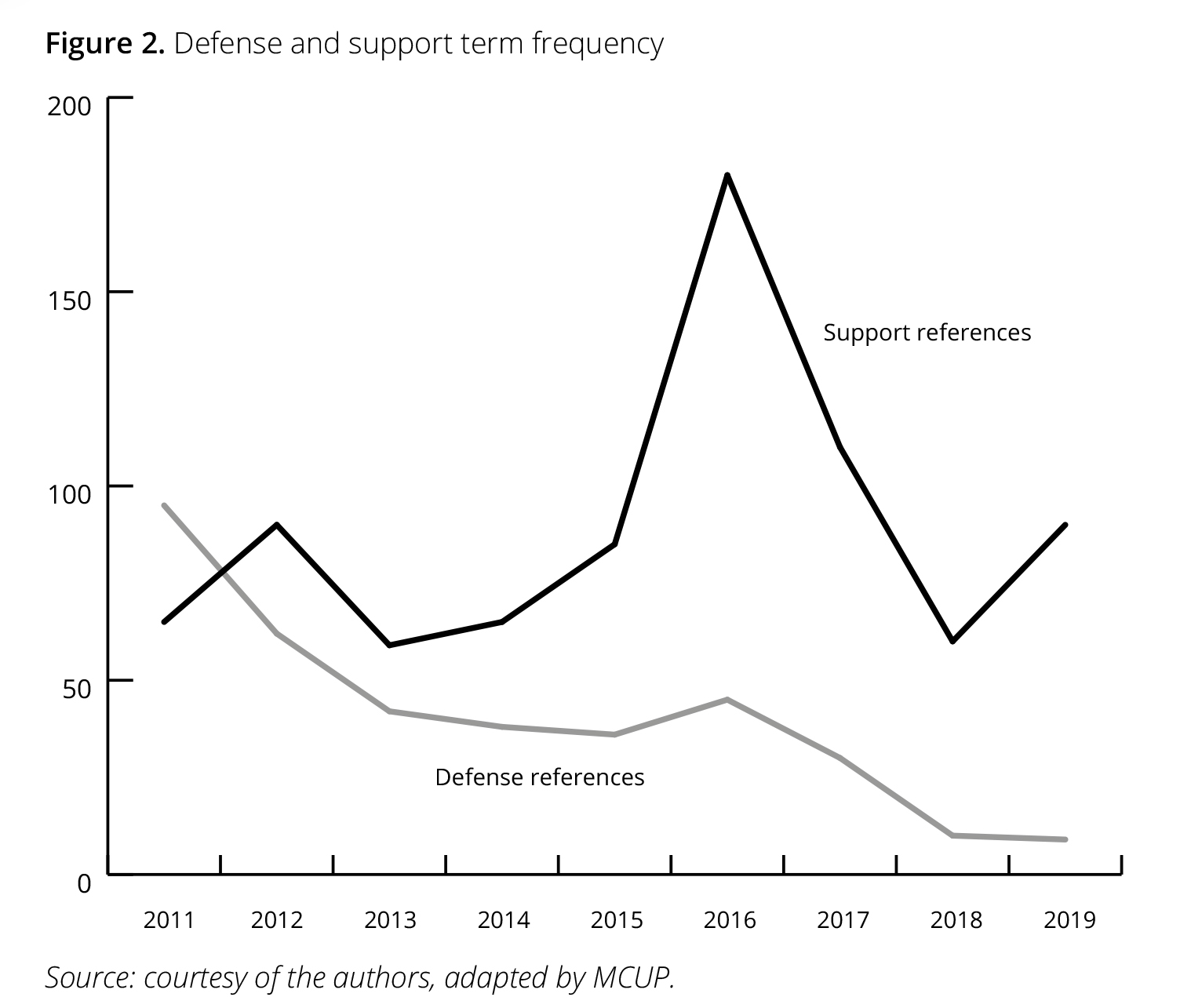

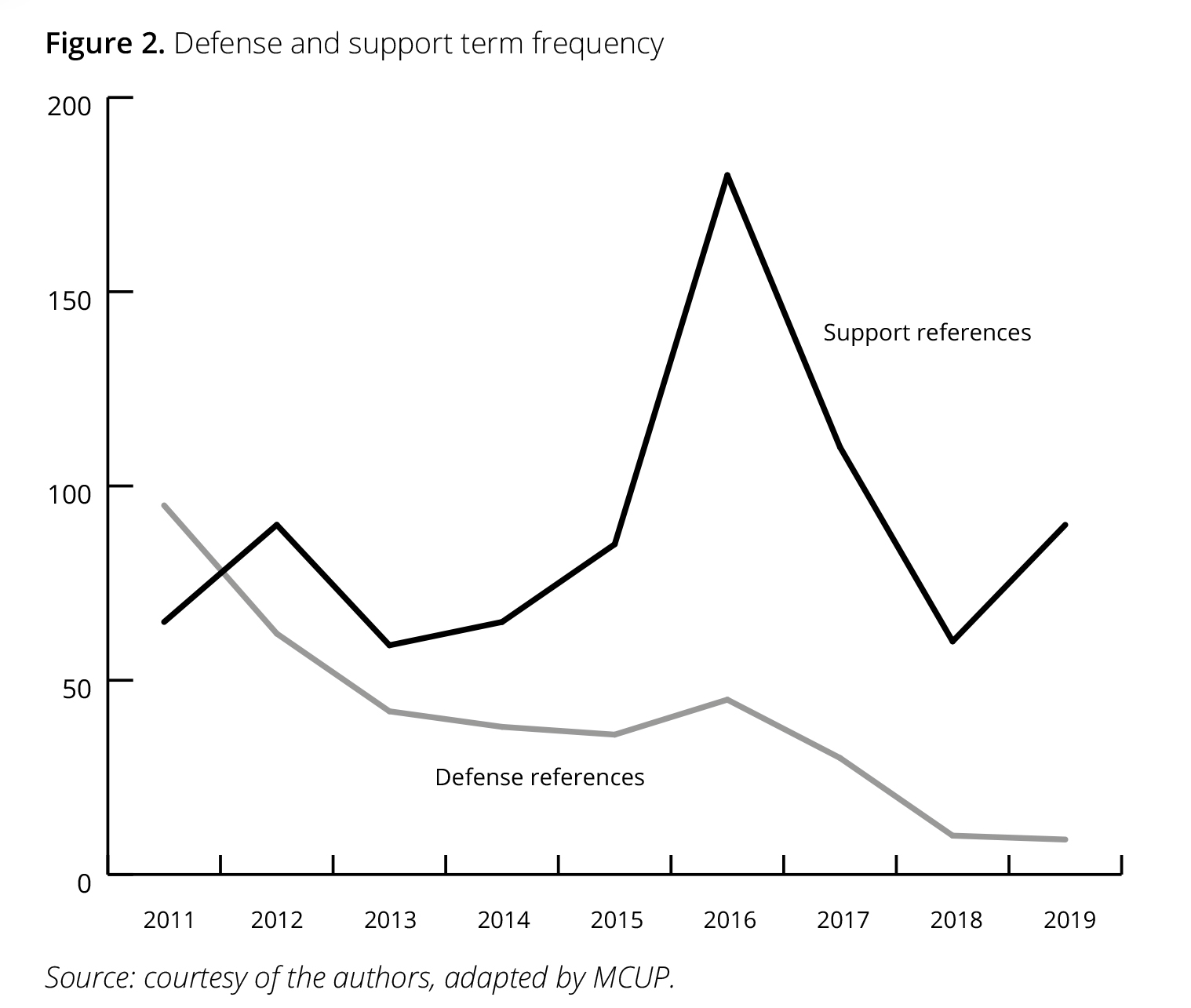

The authors then follow with word frequency analysis for selected key terms by annual publication. While words closely related to the use of force such as “war,” “attack,” “fight,” and “battle” are relatively infrequent in the corpora, there is an identifiable increasing trend in words associated with the use of force during the Abe administration (2012–19), including reference terms for “fighting” and “attacking.” At the same time, certain constellations of terms show a decreasing trend during the same period, such as those associated with “support” (figure 1). This suggests a shift in the function of the JSDF in society: away from a support organization and toward a fighting force. With the exception of 2011, the year of the great east Japan earthquake, all the editions emphasized “defense” related words over “support” related words (figure 2).43 Interestingly, all the editions published during the Abe years saw especially strong emphasis on defense.

Step 2: Document Analysis

Use of Force

The use of force featured in all of the manga editions except for three: 2008, 2010, and 2011. Most prominently, references to the use of force can be characterized in line with individual self-defense: intercepting or thwarting an armed attack against Japan (e.g., a ballistic missile attack) or Japanese assets overseas (pirates attacking a Japanese merchant ship sailing through the Gulf of Aden, for example). While scenarios in which the JSDF participate in or even contemplate the collective use of force (aiding another country under armed attack) are rare, they are mentioned in the 2015 version as detailed below.

Most often, the use of force for individual self-defense purposes is not directly contemplated or undertaken by the JSDF as part of the story line, but it is framed instead as new knowledge, as when characters learn from other characters in the story about the JSDF capability to intercept incoming ballistic missiles or about the JSDF duty to protect Japan’s small islands or territorial waters from foreign intrusion.44 At other times, the use of force directly features as part of the story line but is framed through an analogy, as when the protagonist’s soccer team overcomes the challenge of intercepting “long kicks” from the rival team by implementing JSDF-led BMD activities to win the match.45 In the 2015 edition, the use of force takes on a collective self-defense character for the first time. In reporting about the new U.S.–Japan guidelines, this edition mentions the possibility that the JSDF will engage in concert operations (作戦, sakusen) with the United States in responding to attacks against third-party countries in situations that threaten Japan’s “continued existence” (figure 3).46 Here, too, the scenario is framed as new knowledge to be obtained by the main characters rather than part of the story line.

Figure 3. Japan and the United States engage in concert operations against a mutual adversary

Source: Manga-Style Defense of Japan (2015), 35

Identity

In terms of character traits, consecutive editions portray the JSDF as protective and reliable (disciplined, vigilant, and professional). The 2009 edition, for example, ascribes the JSDF with a protective character. The JSDF protects both Japanese and foreign ships against “scary” pirate attacks against the shipping lanes.47 The presence of the JSDF in the Gulf of Aden and its ability to cope with the danger means, in practice, that the protagonist of the story “needn’t worry” about their father’s boat being targeted by pirates.

Closely linked to the protectiveness trait of the organization itself is the theme of civilians realizing that the JSDF is protecting them. Thus, for example, having learned about the JSDF BMD system, a young character in the 2018 edition proclaims that “the SDF is protecting us!”48 Having returned from an open day at JSDF base with their family, the character’s father similarly says, “I came here today and realized what they do for us. The reason we can live peacefully is because the SDF protects us every day.”49

Members of the JSDF are also reliable in the sense that they are disciplined, professional, and vigilant: despite the many looming threats, the public can thus rest assured, comforted in knowing that the military is dependable. For example, in the 2009 edition, the character of Hatsushima—a member of the Maritime Self-Defense Force (MSDF)—is described at the outset as one of a “reliable” senior (tayoreru oonisan), or somebody you can count on.50 Later in the story, members of other JSDF branches are engaged in antipiracy operations near Somalia. The crew of the reconnaissance aircraft Lockheed P-3C Orion first detect an unidentified vessel: they immediately report to the MSDF destroyer, who then sends a helicopter and operates long-range acoustic device (LRAD), only to see that the unidentified vessel continues its rapid approach toward the Japanese merchant vessel on which the protagonist’s dad is deployed. As the helicopter approaches the boat, the five people on the small, unidentified vessel begin throwing some articles into the sea: an MSDF personnel announces that “there is no risk of attack against our party” and the helicopter returns to the ship. The scene ends as the destroyer’s commander orders their crew “do not lose focus!” Although the danger of attack had subsided as a result of its professional conduct, members of the JSDF remain vigilant, clear-eyed, and reliable under pressure.

In addition to organizational traits, certain character traits of Japanese youth are rewarded and others are looked at as juvenile. Across the years, manga reward youth that are curious, have a strong sense of justice, and are willing to protect others. On the other hand, ignorance and lack of love for one’s family or nation are considered to be juvenile traits and are present in many of the editions. For example, when asked by a JSDF member how much they knew about the Japan–U.S. relationship, Japanese protagonist Kento confesses that “actually . . . I do not know anything.”51 Through the stories and their encounter with knowledge and experiences, the young characters leave the juvenile traits behind as they move to take on positive traits in their stead. That is, the protagonist and the reader mature together with the manga.

In terms of organizational reputation, the JSDF is depicted as defense-oriented, high-tech, and as a desirable organization. For example, the 2007 comic imputes Japan’s security apparatus with a reputation that is defensive in nature (with 28 references to “defense” [bōei]) and one that uses advanced technology (13 references for gijutsu): its weapon systems are aligned with this reputation, and Mr. Groovy, the teacher-like character in the story, repeatedly emphasizes these reputational elements. Mr. Groovy asserts that the BMD system is not an offensive weapon system and is only designed to intercept incoming missiles, adding, “That’s why Japan imported it.”52 Later, when he explains in detail about how the different components of the BMD system work, Mr. Groovy asserts that AEGIS enjoys high-tech capabilities, which makes it an “invincible shield” (muteki no tate sa) that can protect most of Japan with only 2–3 vessels.53 Therefore, the manga imputes the JSDF with a reputation that is both defensive and technologically advanced.

Consecutive mangas also depict the JSDF as a desirable organization. In the 2018 edition, young characters tell one another that they would like to join it in the future, either because they were once “saved” by it during a natural disaster, or because they like video games with weapons. In addition to the desirability of the JSDF as a workplace, the JSDF servicemembers and weapon systems are often described as desirable. Thus, JSDF servicemember Yoshida is “cool” and “big” in the 2015 edition and the 2017 edition features young characters who wish to become JSDF members like their friend’s dad.54 The 2018 edition features a destroyer described by the civilians in the story as “awesome,” “huge,” “powerful,” and “very impressive,” an MSDF captain that is “so cool,” and the Japan Air Self Defense Force (JASDF) Blue Impulse Team that is depicted as “incredible” and “amazing.”55

Norms

In terms of expected behavior in relation to the use of force, there is strong emphasis on cooperating with the United States and in an increasingly wider geographical scope. In 2007, the expected cooperation was in protection of Japan and the Far East. Later in 2015, the expected cooperation with the United States was described as crucial not only in securing Japan but also in maintaining the peace of “Asia as a whole.”56 In addition to the enhanced geographical scope of cooperation with the United States, the relationship between the two countries is described in increasingly positive terms. The United States, for example, is described in 2015 as Japan’s most reliable ally, a “friend with which one can talk about anything.”57

The manga included reference to terms of accepted behavior in relation to the use of force. For example, Oosumi-san, a female MSDF member, explains to the protagonist of the 2009 edition that depending on the circumstance, the JSDF might determine to resort to the use of weapons to thwart pirates attacks.58 Yet, while the story line involves a band of pirates approaching a Japanese merchant ship, the JSDF does not resort to the use violence; indeed, there is no need to do so, as the pirates simply appear to be discarding goods into the ocean instead of attempting an attack on the merchant ship. In this situation, the application of violence is avoided, while the narrative of use of force as acceptable behavior is delivered.

In terms of what defines victory (or preferred outcome) for MOD planners in a potential or actual conflict or problem, it becomes clear that protecting the lives of Japanese and preventing harm are defined as preferred outcomes. The inability to intercept an incoming ballistic missile, for example, is considered unacceptable.

Finally, regarding societal norms—what defense planners would like to see in the broader society—there are at least two key messages: willingness to defend and appreciation. The first societal norm consecutive editions emphasized is that of the willingness to defend Japan: “We must protect this [Japan’s] peace with our hands.” The second societal norm highlighted in consecutive editions is for civilians to show appreciation to JSDF members for protecting them.

Values

In terms of values, the authors found that the participation in JSDF activities, whether at home or abroad, some of which involve the use of force, is often framed as ideationally good and leading to enhanced social status, because by participating in these activities, JSDF members contribute to the peace and security of Japan and the world. For example, the core value in the 2009 edition is that of contributing to international society in tackling an important global challenge of increased piracy. Because Japan is a member of international society and piracy is a crucial global threat and directly impacts the peace and security of Japan, the JSDF must engage with antipiracy missions. As such, the JSDF participation in these activities is deemed as essential and the act of contributing to international society is considered as honorable behavior.

When it comes to rewarded traits of Japanese youth, resilience comes high. For instance, having overcome the challenge in the story, the protagonist’s father encourages them to “stand-up strong to the crisis!” and “be of use to world peace . . . be a man!”59 Moreover, manga editions reward youth who are curious, have a strong sense of justice, and are willing to protect others. On the other hand, in terms of naive or juvenile traits, ignorance and lack of love for one’s family or nation are discouraged. For instance, the 2007 protagonist’s father helps sharpen the message: “And this is what it means to be a grown up: protecting what you love: loved ones, family, work, region, nation. And the world.”60 Through the stories and their encounters with knowledge and experiences, the young characters leave the juvenile traits behind as they move to take on positive traits of willingness to defend Japan and love of their country.

Figure 4. “The threat looming over Japan is becoming more and more serious.”

Source: Manga-Style Defense of Japan (2016), 45.

Perceptual Lens

Throughout the period of analysis, Japan’s threat environment is depicted as increasingly diverse, complex, and hostile.61 As figure 4 taken from the 2016 edition demonstrates, the military threat to Japan is real and significant. Fighter jets, missiles, ships, and submarines appear to be attacking Japan, while the JSDF member asserts that “the threat looming over Japan is becoming more and more serious.”62

In consecutive editions, the JSDF/Japan’s security apparatus protects the nation against violations of airspace and territorial waters, ballistic missiles, piracy, natural disasters, international terrorism, cyberattacks, conflict in space, conflicts in the Middle East, attacks on remote islands, protection and transportation of Japanese residents abroad, and electromagnetic wave attacks, or any combination of the above.

Usually, references to national security threats will not be associated directly with foreign countries—either verbally or visually—and the actor performing the attack often remains unidentified. Thus, for example, the 2007 edition begins with a missile attack against Japan, but the source is unclear.63 It is only after reading the remainder of the manga that one can deduce that North Korea might be behind such an attack, as the reader learns that countries such as North Korea are engaged in missile development and export.64 The rendering of nonstate actors such as pirates and hackers is visually clearer, as figure 5, taken from the 2017 edition, demonstrates. Here are ballistic missiles launching (source unclear) and a hacker implementing a cyberattack. The MSDF member asserts that “nuclear development, ballistic missile problem, and the problem of the Senkakus. [And] the threat of cyber-attacks grows by the year.”65

There are, however, exceptions to this trend: several editions do associate dangerous scenarios with state actors, including the firing of a ballistic missile by North Korea (2012, 2013), the intrusion of Chinese nuclear submarines (2006), and the intrusion of Chinese ships on the territorial waters around the Senkaku Islands in Okinawa Prefecture (2016).66 This trend is especially prevalent between the years 2015–17. For example, taken from the 2016 edition, figure 6 was the only time in the entire corpora in which Chinese boats carrying red flags appear visually as a threat-actor intruding on Japan’s territorial waters around the Senkaku Islands. The protagonist recalls hearing about these incidents in the news.

As for references to the adversary’s character, these are relatively rare. North Korea is described as difficult to understand (2006), and as playing “rough” and “unfair” (2007), while China is cast as a “big country” that is not “observing the rules” (2017).67

Figure 6. “Ah! You mean Chinese boats intruding?!”

Source: Manga-Style Defense of Japan (2016), 43.

Discussion

This article sought to better understand what Japanese defense planners’ efforts to align national and strategic cultures through Manga-Style Defense of Japan (2006–19) tell us about Japan’s use of military force, as advocated by the MOD. The findings of the two-step research design yield at least six conclusions.

First, defense planners seek to close the gap between national and strategic cultures using various means and methods, including the deployment of public relations propaganda in the form of familiarized manga. If in the past these efforts portrayed the JSDF as an organization that can, if it absolutely must, militarily defend Japan, this article’s analysis has shown that today the JSDF must absolutely defend Japan against a plethora of regional and global threats, some of which are only growing more severe by the year.68

While the JSDF must protect Japan against a wide range of security threats and must resort to the use of force to do so, the actual use of weapons by the JSDF is not featured as part of the story line in consecutive mangas and instead is often framed as new knowledge that the main characters come to acquire or via analogies such as competitive sporting matches.69 While the use of force is ubiquitous in the stories, the actual application of violence remains in the realm of the possible, not the actual.

Second, this article identified a high degree of similarity between 2012 and 2017, suggesting that content of manga-style editions during this period were relatively consistent. This finding is consistent with previous research about Japan’s official threat assessment as manifested across government documents, which have registered increased similarity during this period.70 Moreover, an increased emphasis on combat scenarios and activities in a wider geographical scope during the Abe years (since 2012) was identified, as was an important first reference to collective self-defense in the 2015 manga edition. This suggests that while they avoid incorporating the actual use of violence into the narrative of JSDF missions and mandates, defense planners have recently begun priming the Japanese public for scenarios that require the use of force, not only against armed attacks directed at Japan but also against other countries as well, especially Japan’s most important strategic ally, the United States.

Third, the analysis based on the cultural topography model indicates several cultural traits manifesting themselves in multiple ways. Across the model’s four categories, the JSDF is framed as a protective/defensive force that makes crucial contributions to the security and peace of Japan, the region, and the world as a reliable/professional organization and as a benign/desirable entity. One aspect of identity that is most certainly being overemphasized in the manga, presumably because it is being threatened or diminished: the desirability of the JSDF as a place of work. While the JSDF enjoys high levels of trust from the Japanese public, it has struggled for decades to fill its recruitment quotas. The problem has become more acute in recent years, as birth rates in the early 2000s were especially low, leading to a narrow pool of potential young recruits today, and because some of the more recent threats—such as cyber—require the JSDF to attract well-educated personnel. In the most recent editions (2018 and 2019), MOD planners have therefore emphasized the desirability of the JSDF as a workplace in the context of cyber defense, trying to appeal to youth who are interested in and capable with “IT-related stuff ” and foreign languages.71

Fourth, while earlier manga editions tend to avoid clearly associating foreign countries with threatening scenarios—such as missile attacks and territorial violations—later editions do so. Such a trend is especially prevalent during the second Abe administration years but is not linear: while some manga editions (e.g., 2016) single out Chinese vessels as threatening, others (e.g., 2018) do not.72 This suggests that while public relations experts are less hesitant to communicate Japan’s security threats that had been the case in the past, they are still somewhat cautious about securitizing foreign countries.

Fifth, manga produced by the MOD can teach us not only about the JSDF’s identity, norms, and values but also about the MOD’s ideal image of Japanese society in relation to the use of force. Manga editions have sought to instill in the Japanese youth certain norms and values, including the willingness to defend their country, love for the motherland, and resilience in the face of threats to their way of life. While the first two patriotic themes are by no means new, as government-produced manga have been emphasizing the need to defend Japan with Japanese hands since the early 1990s, the third theme of resilience is. The introduction of resilience to the repertoire of JSDF’s character and conduct again indicates that responding to combat and crisis are indeed high on the communication agenda. This stands in contrast to previous research that has argued JSDF public relations efforts up to 2007 characterized the possibility of the organization fighting a war to be only “remote.”73

Sixth, just as important as what made it into the manga is what did not. Missing from the manga editions are references to Japan’s pre-1945 imperial armed forces: these militaristic legacies are nonexistent in the text. The most important historical reference to the pre-1945 period was made in the 2015 manga edition in which the historical background of Japan’s relationship with the United States is explained to the young characters at length. Both the Japanese and American protagonists, Kento and Lucy, were surprised to learn that Japan and the United States had once fought a war (figure 7).74 On learning of their children’s ignorance, Lucy’s father—a U.S. citizen working for the Department of Defense and deployed to Japan and a friend of Kento’s dad—asserts that, “More than 70 years ago, unfortunately, the US and Japan were mutual enemies.” Like Japan and the United States, both fathers became friends after they were rivals: they first met one another having competed in a wrestling match to commemorate the 50th anniversary of the end of the war. Commenting on their friendship, Lucy’s dad described his friendship with Kento’s dad as “his pride.”75 Later on, the two kids learn more about Japan’s history during a visit to MOD, including that it surrendered unconditionally and how it decided to become a “peace state” by adopting its constitution, that both countries signed the security alliance in 1951, and that the rationale behind it was to help Japan protect itself in case it was attacked.76 That is, while the manga educates the readers about the history of the relationship between Japan and the United States, going back to 1941, the narrative is a simple one, lacking explanation of Japan’s military expansion in Asia and of the history of Japan’s Imperial Army and Navy. Indeed, the lack of historical references in MOD-sanctioned manga contradicts the efforts of some leading members of the MSDF to connect imperial naval traditions to contemporary public relations campaigns.77

Figure 7. “Japan and the US fought a war?!”

Source: Manga-Style Defense of Japan (2015), 9.

Conclusion

In their attempt to align Japan’s national and strategic culture and educate youth about national security and defense issues, MOD planners and government public relations experts reveal much about their approach to Japan’s use of military force, with its growing geographical scope and close cooperation with the United States.78 The use of force is framed by public relations experts in consecutive manga editions in a subtle yet permeating manner. Conversely, the use of force is ubiquitous across most annual publications of Manga-Style Defense of Japan, as the characters in the stories learn about the various ways with which the JSDF must defend Japan against the many security threats the country faces and how soldiers train to fulfill this duty. The actual application of violence in the stories is avoided and remains out of sight, however. For example, instead of reading and seeing the JSDF using their weapons to thwart pirates or incoming North Korean missiles in the graphic novels, young readers only learn about the potential use of violence through the knowledge imparted to them by various teacher-like characters and through the use of analogies. By using these techniques, MOD planners reverse the old adage of “show, don’t tell”: while telling the readers that violence is indeed possible, they do not show it to them.

One possible reason for this choice is the very nature of the manga. Since manga-style editions accompany the official defense white papers published annually by MOD, these stories are likely to be scrutinized by both domestic and foreign audiences as political documents.79 Had they featured JSDF personnel applying violence against Chinese boats, for example, manga editions could generate considerable negative publicity and alienate those sections of the public still largely resistant to the use of military force in international disputes. How do MOD planners seek to close the gap between strategic and national cultures then? By using subtle messaging techniques and avoiding the show of violence.

While this article has focused on the MOD’s use of manga, future studies may examine other mediums of strategic cultural communication, including film and anime as well as other government and military agencies’ use of such materials in bridging the gap between national and strategic cultures. Likewise, the various mediums by which these materials are presented to domestic and international audiences should also be carefully considered, especially the use of social media such as Twitter, Facebook, and YouTube.80

Future studies should also focus on the JSDF’s military culture, as it may well be distinct in important ways than what the MOD would like it to be as represented in government propaganda materials. Additionally, the JSDF may not have a unitary culture, but rather several, perhaps competing strategic subcultures, both between military agencies and among them.81 As Japanese pacifism continues to come under reconsideration by policy elites, what identifiable differences in identity, norms, and values can be found across Japan’s ground, maritime, and air forces? These important questions remain unanswered, offering promising future directions for research.

Endnotes

- For an analysis of Japan’s changing security threats and alliance relations in the postwar period, see Nicholas D. Anderson, “Anarchic Threats and Hegemonic Assurances: Japan’s Security Production in the Postwar Era,” International Relations of the Asia-Pacific 17, no. 1 (January 2017): 101–35, https://doi.org/10.1093/irap/lcw005. For analyses of Japan’s changing threat perceptions in the postwar period, see Eitan Oren, “Japan’s Evolving Threat Perception: Data from Diet Deliberations, 1946–2017,” International Relations of the Asia-Pacific 20, no. 3 (September 2020): 477–510, https:// doi.org/10.1093/irap/lcz016; and Eitan Oren and Matthew Brummer, “Reexamining Threat Perception in Early Cold War Japan,” Journal of Cold War Studies 22, no. 4 (Fall 2020): 71–112, https://doi.org/10.1162/jcws_a_00948.

- Including a strongly conservative and internationalist foreign policy ideology, generally high popular opinion ratings, majority control of both houses of parliament, a more assertive Chinese rival under President Xi Jinping, and a less reliable American ally under President Donald J. Trump.

- As opposed to “public contests,” which concern the struggle between domestic political actors in shaping public policy. See Jan Melissen., ed., The New Public Diplomacy: Soft Power in International Relations (New York: Palgrave, 2005), https://doi .org/10.1057/9780230554931.

- For a recent empirical example on Japan, see Wrenn Yennie Lindgren, “WIN-WIN! with ODA-Man: Legitimizing Development Assistance Policy in Japan,” Pacific Review 34, no. 4 (2021): 633–63, https://doi.org/10.1080/09512748.2020.1727552.

- Jeannie L Johnson and Matthew T. Berrett, “Cultural Topography: A New Research Tool for Intelligence Analysis,” Studies in Intelligence 55, no. 2 (2011): 11–12, https:// doi.org/10.1037/e741172011-002.

- Sabine Frühstück, Uneasy Warriors: Gender, Memory, and Popular Culture in the Japanese Army (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2007), 146.

- For analysis of this reinterpretation, see Adam P. Liff, “Policy by Other Means: Collective Self-Defense and the Politics of Japan’s Postwar Constitutional Reinterpretations,” Asia Policy, no. 24 (July 2017): 139–72. For historical context, see Akihiko Tanaka, Japan in Asia: Post-Cold-War Diplomacy (Tokyo: Japan Publishing Industry Foundation for Culture, 2017); Matthew Brummer, “Bridges over Troubled History: Japan’s Foreign Policy in Asia,” International Studies Review 21, no. 1 (March 2019): 172–74, https://doi.org/10.1093/isr/viy058; and Andrea Pressello, “Japanese Peace Diplomacy on Cambodia and the Okinawa Reversion Issue, 1970,” Japan Forum (2021): https:// doi.org/10.1080/09555803.2020.1863446.

- For example, Japan possesses no nuclear weapons, strategic bombers, ballistic missiles, or ships purposely built as aircraft carriers. Yet, it has the resources to develop all of these capabilities.

- For example, see scholarship on Japan as a “buck-passing”: Jennifer Lind, “Pacifism or Passing the Buck?: Testing Theories of Japanese Security Policy,” International Security 29, no. 1 (Summer 2004): 92–121; “reluctant,” Michael J. Green, Japan’s Reluctant Realism: Foreign Policy Challenges in an Era of Uncertain Power (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2001), https://doi.org/10.1057/9780312299804; “post-classical,” Tsuyoshi Kawasaki, “Postclassical Realism and Japanese Security Policy,” Pacific Review 14, no. 2 (2001): 221–40, https://doi.org/10.1080/09512740110037361; or “mercantile,” Eric Heginbotham and Richard J. Samuels, “Mercantile Realism and Japanese Foreign Policy,” International Security 22, no. 4 (Spring 1998):171–203, https://doi.org /10.2307/2539243.

- For example, see scholarship on Japan’s constitution in Wada Shuichi, “Article Nine of the Japanese Constitution and Security Policy: Realism versus Idealism in Japan since the Second World War,” Japan Forum 22, nos. 3–4 (2019): 405–31, https://doi.org /10.1080/09555803.2010.533477; for the electoral system, see Tomohito Shinoda, “Japan’s Parliamentary Confrontation on the Post–Cold War National Security Policies,” Japanese Journal of Political Science 10, no. 3 (December 2009): 267–87, https:// doi.org/10.1017/S146810990999003X; and for role of the prime minister, see Christopher W. Hughes and Ellis S. Krauss, “Japan’s New Security Agenda,” Survival 49, no. 2 (2007): 157–76, https://doi.org/10.1080/00396330701437850.

- Wrenn Yennie Lindgren and Petter Y. Lindgren, “Identity Politics and the East China Sea: China as Japan’s ‘Other’,” Asian Politics & Policy 9, no. 3 (2017): 378–401, https://doi.org/10.1111/aspp.12332.

- Andrew L. Oros, “Japan’s Strategic Culture: Security Identity in a Fourth Modern Incarnation?,” Contemporary Security Policy 35, no. 2 (2014): 229, https://doi.org/10 .1080/13523260.2014.928070. In this article, and in line with the authors’ goal to shed light on the specific issue of use of force, the authors opt for a narrow definition of Japan’s strategic culture as the “beliefs and values related to the use of its military power.” See Oros, “Japan’s Strategic Culture,” 229.

- Oros, “Japan’s Strategic Culture.”

- Thomas U. Berger, “From Sword to Chrysanthemum: Japan’s Culture of Antimilitarism,” International Security 17, no. 4 (Spring 1993): 119–50, https://doi.org /10.2307/2539024.

- Peter J. Katzenstein, Cultural Norms and National Security: Police and Military in Postwar Japan (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1996); and Stephanie Lawson and Seiko Tannaka, “War Memories and Japan’s ‘Normalization’ as an International Actor: A Critical Analysis,” European Journal of International Relations 17, no. 3 (2011): 405–28, https://doi.org/10.1177/1354066110365972.

- Andrew L. Oros, Normalizing Japan: Politics, Identity, and the Evolution of Security Practice (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2008).

- Amy Catalinac, “Identity Theory and Foreign Policy: Explaining Japan’s Responses to the 1991 Gulf War and the 2003 U.S. War in Iraq,” Politics & Policy 35, no. 1 (March 2007): 58–100, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1747-1346.2007.00049.x; Glenn D. Hook and Key-Young Son, “Transposition in Japanese State Identities: Overseas Troop Dispatches and the Emergence of a Humanitarian Power?,” Australian Journal of International Affairs 67, no.1 (2013): 35–54, https://doi.org/10.1080/10357718.2013.7482 74; and Linus Hagström and Karl Gustafsson, “Japan and Identity Change: Why It Matters in International Relations,” Pacific Review 28, no. 1 (2015): 1–22, https://doi .org/10.1080/09512748.2014.969298.

- Bhubhindar Singh, Japan’s Security Identity: From a Peace-State to an International-State (London: Routledge, 2013).

- Oros, “Japan’s Strategic Culture,” 231–32.

- Oros, “Japan’s Strategic Culture,” 232.

- Sheila A. Smith, Japan Rearmed: The Politics of Military Power (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2019).

- Jeffrey J. Hall, “Towards an Unrestrained Military: Manga Narratives of the Self-Defense Forces,” in The Representation of Japanese Politics in Manga: The Visual Literacy of Statecraft, ed. Roman Rosenbaum (London: Routledge, 2020), 123–24.

- Oros, “Japan’s Strategic Culture,” 228.

- Takako Hikotani, “Japan’s Changing Civil-Military Relations: From Containment to Re-engagement?,” Global Asia 4, no. 1 (March 2009): 20–24.

- Sado Akihiro, The Self-Defense Forces and Postwar Politics in Japan, trans. Noda Makito (Tokyo: Japan Publishing Industry Foundation for Culture, 2017), 101.

- Oros, “Japan’s Strategic Culture,” 243.

- Matthew Brummer, “Japan: The Manga Military,” Diplomat, 19 January 2016.

- Patrick Galbraith, The Moe Manifesto: An Insider’s Look at the Worlds of Manga, Anime, and Gaming (Clarendon, VT: Tuttle Publishing, 2014).

- Brummer, “Japan.”

- Brummer, “Japan.”

- Takayoshi Yamamura, “Cooperation Between Anime Producers and the Japan SelfDefense Force: Creating Fantasy and/or Propaganda?,” Journal of War & Culture Studies 12, no. 1 (2019): 8–23, https://doi.org/10.1080/17526272.2017.1396077.

- Frühstück, Uneasy Warriors.

- For example, see Koichi Iwabuchi, “Pop-Culture Diplomacy in Japan: Soft power, Nation Branding and the Question of ‘International Cultural Exchange’,” International Journal of Cultural Policy 21, no. 4 (2015): 419–32, https://doi.org/10.1080/102866 32.2015.1042469; and Akos Kopper, “Pirates, Justice and Global Order in the Anime ‘One Piece’,” Global Affairs 6, nos. 4–5 (2020): 503–17, https://doi.org/10.1080/2334 0460.2020.1797521. For example, see Hall, “Towards an Unrestrained Military”; and Jeffrey J. Hall, “Japan’s Anti-Kaiju Fighting Force: Normalizing Japan’s Self-Defense Forces through Postwar Monster Films,” Giant Creatures in Our World: Essays on Kaiju and American Popular Culture, ed. Camille D. G. Mustachio and Jason Barr (Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 2017): 138–60.

- Frühstück, Uneasy Warriors, 2–3.

- Frühstück, Uneasy Warriors, 148.

- Frühstück, Uneasy Warriors, 2.

- Jeannie L. Johnson, Strategic Culture: Refining the Theoretical Construct (Fort Belvoir, VA: Defense Threat Reduction Agency Advanced Systems and Concepts Office, 2006), 17; and Jeannie L. Johnson, The Marines, Counterinsurgency, and Strategic Culture: Lessons Learned and Lost in America’s Wars (Washington, DC: Georgetown University Press, 2018), chap. 1.

- Johnson, The Marines, Counterinsurgency, and Strategic Culture, 7.

- All the official manga can be accessed at the Japanese MOD website: www.mod.go.jp /j/kids/comic/index.html.

- The Defense of Japan is an annual white paper published since 1970 by the Japan Defense Agency within the Ministry of Defense (MOD). The publication consists of a detailed overview of developments in Japan’s defense policy within the context of the U.S.–Japan alliance, as well as analysis of the defense policies of other key players in the security environment surrounding Japan. See Eitan Oren and Matthew Brummer, “Threat Perception, Government Centralization, and Political Instrumentality in Abe Shinzo’s Japan,” Australian Journal of International Affairs 74, no. 6 (2020): 25, https:// doi.org/10.1080/10357718.2020.1782345.

- See Manga-Style Defense of Japan (Tokyo: Ministry of Defense, 2006); Manga-Style Defense of Japan (2007); and Manga-Style Defense of Japan (2015).

- The highest correlation between any two editions was obtained for the years 2012 and 2013, with a 0.83 Pearson correlation coefficient, followed by 2013/2014 (0.77), 2014/2017 (0.76), 2013/2016 (0.76), 2012/2014 (0.76), 2014/2015 (0.75), 2016/2017 (0.73), and 2012/2016 (0.71). The lowest correlations between any two editions were obtained for the years 2009 and 2010 (0.07), 2007/2009 (0.12), and 2007/2010 (0.15).

- Japanese words related to “support” query: サポート, 助ける, 味方, 増援, 手助け, 掩護, 援助, 支える, 支援, 救助, 救援, 用途, 補佐, 補助, 資す. For “defense”:ディフ ェンス, 備え, 守り, 守る, 守備, 掩護, 監視, 見る, 見守る, 見張る, 視る, 警備, 警 戒, 警護, 護衛, 避難, 防ぐ, 防備, 防御, 防衛, 防護.

- See, for example, Manga-Style Defense of Japan (2006), 12, 19–20; Manga-Style Defense of Japan (2012), 9; and Manga-Style Defense of Japan (2016), 43.

- Manga-Style Defense of Japan (2007).

- Manga-Style Defense of Japan (2015), 34–35.

- Manga-Style Defense of Japan (2009), 26, 28.

- Manga-Style Defense of Japan (2018), 13.

- Manga-Style Defense of Japan (2018), 15.

- Similarly, having learned that in addition to the MSDF activities in missile defense, the service also patrols Japan’s oceans 24/7, a young character in the 2018 edition exclaims: “The SDF sounds so reliable!” See Manga-Style Defense of Japan (2018), 13.

- Manga-Style Defense of Japan (2015), 14.

- Manga-Style Defense of Japan (2007), 36.

- Manga-Style Defense of Japan (2007), 44.

- Manga-Style Defense of Japan (2015), 13; and Manga-Style Defense of Japan (2017), 32.

- Manga-Style Defense of Japan (2018), 5, 6, 24.

- Manga-Style Defense of Japan (2015), 16.

- Manga-Style Defense of Japan (2015), 31.

- Manga-Style Defense of Japan (2009), 31.

- Manga-Style Defense of Japan (2009), 61.

- Manga-Style Defense of Japan (2009), 60.

- The only time a document acknowledged that a certain threat is diminishing was the 2006 edition, when the threat of a full-scale land invasion of Japan was deemed less likely. See Manga-Style Defense of Japan (2006), 22.

- Manga-Style Defense of Japan (2016), 45.

- Manga-Style Defense of Japan (2007), 2.

- Manga-Style Defense of Japan (2007), 26.

- Since the late 2000s, cyberattacks have become the most frequently mentioned threat in the Japanese Diet. See Oren, “Japan’s Evolving Threat Perception,” 25.

- Manga-Style Defense of Japan (2006). See Manga-Style Defense of Japan (2012–13); and Manga-Style Defense of Japan (2016).

- Manga-Style Defense of Japan (2007); Manga-Style Defense of Japan (2006); and MangaStyle Defense of Japan (2017).

- Sabine Frühstück, “ ‘To Protect Japan’s Peace We Need Guns and Rockets’: The Military Uses of Popular Culture in Current-day Japan,” Asia Pacific Journal 7, no. 34 (2009): 3.

- As distinct from the use of force. To recall, this article defined the use of force as using physical strength or capabilities to solve a military problem.

- Oren and Brummer, “Threat Perception, Government Centralization, and Political Instrumentality in Abe Shinzo’s Japan,” 721–45.

- Manga-Style Defense of Japan (2019), 25, 27.

- See Manga-Style Defense of Japan (2016); and Manga-Style Defense of Japan (2018). 73.

- Frühstück, Uneasy Warriors, 148.

- Manga-Style Defense of Japan (2015), 9.

- Manga-Style Defense of Japan (2015), 10.

- Manga-Style Defense of Japan (2015), 19.

- Alessio Patalano, Post-war Japan as a Sea Power: Imperial Legacy, Wartime Experience and the Making of a Navy (London: Bloomsbury Publishing, 2015), 84–87.

- For historical description of Japan’s changing foreign and security policy, see Tanaka, Japan in Asia; and Brummer, “Bridges over Troubled History,” 172–74.

- Eitan Oren and Matthew Brummer, “How Japan Talks About Security Threats,” Diplomat, 14 August 2020.

- The mediums themselves may be an important part of the message. See Marshall McLuhan, Understanding Media: The Extensions of Man (New York: Penguin, 1964).

- For strategic subcultures, see for example, Alan Bloomfield, “Time to Move On: Reconceptualizing the Strategic Culture Debate,” Contemporary Security Policy 33, no. 3 (2012): 437–61, https://doi.org/10.1080/13523260.2012.727679; and Oros, “Japan’s Strategic Culture.”