Abstract: This article uses a comprehensive examination of Emirati strategic culture and its national role conception to examine the likelihood that the United Arab Emirates would pursue the possession of a nuclear weapons program. The article concludes that the UAE is predisposed to reject the pursuit and possession of nuclear weapons due to its dominant national role as a regional and global collaborator; the high value it places in its conventional military capabilities and alliance with the United States; Emirati identity as a regional leader in social and technological innovation with the intent to elevate the country beyond regional stereotypes of violence, repudiation of progress, and political Islam; and its unique perceptual lens on productive strategies for operating within Iran’s sphere of influence. Continued rejection of a nuclear weapons program hinges on U.S. engagement in the region, where the United States has a willing and like-minded ally.

Keywords: strategic culture, perceptual lens, identity, national role conception, United Arab Emirates, UAE

Introduction

In August 2020, the Barakah Nuclear Energy Plant went online, making the United Arab Emirates (UAE) the first Arab nation to construct and operate a nuclear power plant. The UAE is aggressively preparing for a post-carbon world and Barakah is expected to provide 25 percent of the nation’s power as the state transitions away from fossil fuels. The UAE’s nascent nuclear energy program has raised fears that it may represent a gateway to greater nuclear proliferation throughout the Arab Gulf region. No Gulf state, outside of the UAE, has had the expertise to develop its own nuclear (civil or military) programs, but that is changing. The UAE is determined to develop an entire industry of native nuclear experts and has already begun to export its expertise to Saudi Arabia.1 If this trend continues, and there is nothing to suggest that it will not, the region will experience a surge in nuclear expertise, infrastructure, and raw material, lowering the breakout time for procurement of a nuclear weapon. Current concerns are exacerbated by the UAE’s past as a hub for the AQ (Abdul Qadeer) Khan network, a black market proliferation organization believed to have sold Iran and North Korea centrifuges and blueprints for centrifuges, the hardware necessary to enrich uranium to the degree required for nuclear weapons, significantly advancing each states’ weapons program.2 Some claim this makes the UAE particularly unsuitable to be a guardian of sensitive nuclear technology, and it is with these concerns in mind that Emirati leadership, under the strict diktat of Mohamed bin Zayed, the crown prince of Abu Dhabi and acting head of state, has gone to great lengths to assure the international community—through profuse statements and concrete commitments—that it will act to safeguard nuclear nonproliferation.3 For example, the Emirati state is freely forgoing its right to domestic uranium enrichment and to reprocessing spent fuel, two processes necessary to create the fissile material for a nuclear weapon, as a demonstration of good faith in building a bulwark against regional proliferation.4 This article engages in a multifaceted examination of the strategic culture shared by the intimate collective of individuals that holds power within the UAE to better assess the sincerity of their nonproliferation intent and thereby gauge the likelihood that the Emirati state would pursue the possession of nuclear weapons or enable its pursuit by others. These moves would create a potentially disastrous chain reaction throughout a region already rife with volatility. Ultimately this article argues that the Emirati nuclear energy program is likely to remain a civilian energy program and will not trigger a wave of nuclear weapons acquisition as long as certain conditions are met. These conditions are reflective of influential elements within Emirati strategic culture and include robust U.S. engagement in the region, particularly through strong conventional military cooperation; upholding the Emirati-set nuclear energy “gold standard”; and strong security guarantees to the UAE and its neighbors.

Research and Analytical Methodologies

The research findings within this article were produced through a merger of two methodologies that weigh the effects of cultural factors in the arena of international security and executive decision making in foreign affairs: national role conception and the Cultural Topography Framework.

National Role Conception

The author’s research employed a method for assessing national role conception (NRC) to examine how the internally constructed identity role of a state manifests externally. Advocates of the national role conception approach argue that states identify with particular roles and tend to behave consistently within them. NRC impacts nuclear decision making because actors making foreign policy decisions do so based on their perceptions of their own intended international role and the behaviors associated with that role.5 NRC is especially useful in the examination of proliferation trends, because international roles, reflective of internal culture, do not typically change rapidly and drastically, and therefore provide a relatively stable and predictable method of forecasting nuclear strategy.

For this article, the author followed the adaptation of Glenn Chafetz, Hillel Abramson, and Suzette Grillot using 13 national role conceptions (table 1) tailored specifically to the subject of nuclear proliferation. In doing so, they assigned each role to one of three categories: roles that tend to move a state toward proliferation, roles that tend to move a state away from proliferation, and roles that move neither toward nor away from proliferation.

Table 1. National roles and their major functions

| Role type |

Function |

Tendency toward nuclear status (Y/N)

|

| Regional leader |

Provides leadership to limited geographical or functional area |

Yes |

| Global system leader |

Lead states in maintaining global order |

Yes |

| Regional protector |

Provide protection in the region |

Yes |

| Anti-imperialist |

Act as agent of struggle against imperial threat |

Yes |

| Mediator-integrator |

Undertake special tasks to reconcile conflicts between other states or groups of states |

No |

| Example |

Promote prestige and influence by domestic or international policies |

No |

| Protectee |

Affirm the responsibility of other states to defend it |

No |

| Regional subsystem collaborator |

Undertake far-reaching commitments to cooperate with other states to build wider communities |

No |

| Global system collaborator |

Undertake far-reaching commitments to cooperate with other states to support the emerging global order |

No |

| Bridge |

Convey messages between peoples and states |

No |

| Internal developer |

Direct efforts of own and other government to internal problems |

No |

| Active independent |

Shun permanent commitments; cultivate good relations with as many states as possible |

No |

| Independent |

Act for one’s own narrowly defined interests |

No |

Source: adapted from Chaffetz, Abrahmson, and Grillot, Culture and Foreign Policy.

Cultural Topography Framework

The Cultural Topography Framework engages in a thorough dissection of an actor’s identity, values, norms, and perceptual lens to better understand the actor’s perspective, motivation, and likely behavior on a specified intelligence issue—insights that allow policy makers to effectively tailor U.S. policy to address a specific threat. The majority of the findings produced for this article focus on identity: how a state perceives and portrays itself, what traits it designates as primary to its identity, and the reputation that it pursues.6 The exploration of identity offered through the Cultural Topography Framework expands on that provided by national role conception and adds further nuance and context. Of the four cultural factors associated with the Cultural Topography Framework, identity tends to be the anchor, influencing key values, the impetus for norms, and how the outside world is perceived. The values category within this framework examines material goods or ideational factors that confer enhanced status within the group; norms are expected and accepted behaviors and defined taboos; and perceptual lens is how the actor perceives “facts” in the universe of available data and how it shapes perceptions of others. All of these domains will be discussed in greater depth throughout this article.

Actors and Source Material

The research that informs the designation of national role conceptions in this article categorized nearly 100 public remarks and statements from three influential Emirati leaders into the role types adopted from the work of Glenn Chaffetz, Hillel Abramson, and Suzette Grillot.7 National role conceptions are determined by identifying role statements denoting a vision of status and action. The author’s evaluation of UAE role conception included statements from Mohamed bin Zayed, crown prince of Abu Dhabi, deputy supreme commander of the armed forces, and de facto head of state; Abdullah bin Zayed, Mohamed’s brother, and minister of foreign affairs and international cooperation; and Ambassador Yousef Al Otaiba. Each were selected as subjects due either to their authority or their close proximity to authority. Mohamed bin Zayed holds decision-making authority almost exclusively. The two additional figures are individuals he trusts to act as his mouthpiece; they enable and explain Mohamed bin Zayed’s vision and authority. The policy remarks collected and evaluated spanned a range of subjects and catered to diverse audiences including the Emirati general population, the American public and its policy makers, and forums across international institutions. Role conception findings are more robust when found to be largely consistent across speakers, audience, and subject matter in conveying strongly constructed national role conceptions. In addition to official remarks from the three Emirati officials, which were used to determine the state’s national role conceptions, the author also engaged secondary sources to provide context and further analysis of both national role conceptions and the Cultural Topography Framework. These secondary sources comprised of published works from regional and military experts, individuals with personal relationships with Emirati leadership featured in this article, and local publications.

Clear patterns emerged from the data set indicating one dominant and two auxiliary role conceptions for the UAE. The dominant national role that emerged for the UAE is that of regional and global collaborator, with the secondary roles of example and protectee. These, according to Chaffetz, Abramson, and Grillot’s NRC categories, indicate that the Emirati state is predisposed to reject the pursuit of a nuclear weapons program.

One national role conception emerged from the data set that, according to Chaffetz, Abramson, and Grillot, could prompt a state to pursue nuclear weapons. Regional leader and global system leader role types include great power aspirations and defiance against subordinate roles, and while a number of Emirati statements indicated aspirations of leadership, they did so in narrow corridors in fields related to advanced innovation, renewable energy, and human rights. Overall, Emirati leadership is careful and constrained in assuming a leadership mantle and in making role statements that would confer an identity of leadership, especially in the realm of international security.

Were the UAE to embrace a regional leadership role, competing with its Arab neighbors for influence and power, concerns of Emirati disregard for international norms, including the pursuit of nuclear weapons, would be well-founded. If the Emirati state continues instead to embrace a collaborator role, as this research has found, then it is more likely that strong bilateral and multilateral pressure to refrain from weapons pursuits will remain a salient disincentive to pursue proliferation or enable it anywhere in the region.

The combined findings from cultural research conducted through the Cultural Topography Framework and an evaluation of national role conception delivered four primary takeaways that reinforce the UAE’s likely commitment to nuclear nonproliferation: an identity rooted in regional and global collaboration; the profound value Emirati leadership places in its conventional military forces and partnership with the United States; Emirati identity as a leader in innovative policies; and UAE’s unique perceptual lens regarding the threat Iran embodies.

UAE as a Regional and Global Collaborator In Chief

Several Emirati national role conceptions were reflected in the data set; the strongest, overwhelmingly so, was that of regional and international collaborator. As defined by K. J. Holsti, the original architect of NRC, states with a collaborator role conception undertake wide-ranging commitments to collaborate with regional and international states and contribute to stronger communities and international order. Collaborators see themselves as responsible stewards of their region; they seek arbitration for disputes and conflicts in regional and international institutions, comply with international norms and rules, and generally seek to be good neighbors.8 Chaffetz, Abramson, and Grillot add that states with robust collaborative national roles are concerned with being good neighbors and global citizens and comply with internationally established rules, including nonproliferation statutes. Emirati role statements that indicate strong tendencies to collaborate include direct reference to its regional and global community, its partnerships with many nations, and a desire for international cooperation in the face of challenges.9

Collaboration is more than just a role; it is a behavioral norm and a cultural variable that assists in forecasting a state’s willingness to engage with partners and allies. The UAE’s strong narrative of collaboration was reinforced by action early on in its nuclear journey. In 2008, well before any agreements had been signed, Emirati leadership sought out widespread collaborations on its nuclear designs. Acutely attuned to the realities of its position in a volatile region, the UAE solicited input from a wide variety of actors to stem the flow of spreading concern. Collaboration included the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA), the United States, the United Kingdom, France, South Korea, Germany, Japan, China, and Russia.10 In a state where authority remains in exclusive hands, this was a notably diffuse and inclusive process.

The UAE continued its path to nuclear energy through an overtly collaborative approach. The Arab Gulf region is reaching a watershed moment. Production and consumption of fossil fuels is becoming less acceptable as the damaging effects on the climate become increasingly severe. States reliant on oil production for survival, like the Arab Gulf states, face a harsh ultimatum: adapt or fail. The UAE is adapting, and its path to nuclear energy was relatively painless due in large part to its overt signaling of collaborative intent.

The UAE has gone to extended lengths to display an ironclad commitment to nonproliferation. Before even signing the 123 Agreement with the United States, which facilitates bilateral cooperation between the United States and signatories in developing peaceful nuclear energy programs, the UAE waived its right to domestic uranium enrichment and the reprocessing of spent fuel, which provide fuel and fissile material for nuclear weapons production.11 Instead, the UAE committed to purchasing its fuel from commercial partners and sending its spent fuel to a current nuclear power to be reprocessed. These obligations were self-imposed and went beyond the strict measures of the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT) and U.S. laws.12 The agreement explicitly states that

The United Arab Emirates shall not possess sensitive nuclear facilities within its territory or otherwise engage in activities within its territory for, or relating to, the enrichment or reprocessing of material, or alteration in form or content (except by irradiation or further irradiation or, if agreed to by the parties, post-irradiation examination) of plutonium, uranium 233, high enriched uranium, or, if agreed to by the parties, irradiated source or special fissionable material.13

Abdullah bin Zayed Al Nahyan, UAE minister of foreign affairs and international cooperation, has stated that “the UAE’s interest in nuclear energy stems exclusively from a desire to meet growing domestic energy demands in a commercially and environmentally responsible manner.”14 The voluntary relinquishment of enrichment and reprocessing rights was an international first—no state before, or since, has agreed to give up these rights. Following the signing of the 123 Agreement in 2009, the UAE promptly signed the Additional Protocol, granting the IAEA wider inspection authority, as well as the IAEA Convention on Nuclear Safety and all other required and optional protocols aimed at enhancing transparency and security.15

Both American and Emirati officials have referred to the UAE agreement as a “gold standard” for treaties going forward, establishing new norms for future bilateral nuclear pursuits. The UAE has stated that this is by Emirati design, expressing hope that the Emirati program will be a “model” for fellow non-nuclear states interested in pursuing peaceful nuclear energy.16 The UAE, however, intends for its nuclear program to go beyond soft-power modeling. By agreeing to such stringent measures, it is hitching its nuclear agreement to its strategy of containing future nuclear deals with Iran. The UAE agreement with the United States benefits from a “favored nation” clause, guaranteeing that the United States will not enter a peaceful nuclear energy agreement with another state in the region with terms more favorable than those in the U.S.– UAE agreement.17

Other states in the region have seen the Emirati “model” succeed in developing an alternative energy source and will likely follow suit if they wish to remain a viable state in a post-oil world. If collaboration is essentially a commitment to create strong communities and international order, the UAE’s abstention of uranium enrichment is a convincing commitment to ensuring stability and order in a region that could very well see itself inundated with nuclear know-how.

The UAE’s main regional adversary is Iran, a neighbor whom it perceives to be determined to obtain nuclear weapons to elevate its bargaining leverage. In the face of that security threat, the UAE has opted for a strategy of containment and collaboration—by voluntarily restraining its own enrichment and reprocessing abilities and seeking widespread international consensus it hopes to strengthen regional norms in a similar direction. The UAE recognizes that if it were to now demand and act on the enrichment rights allowed within the NPT it would set a dangerously destabilizing precedent in the region that could see highly enriched uranium become a common commodity. As a state consumed with concerns about domestic and regional stability, the UAE would produce the ironic counter-effect of an unacceptably unstable environment.18 Instead, the UAE has opted for a collaborator role alongside the United States and many other nations in the development of its nuclear program, flipping the “if they can do it, we can do it” argument on its head. Their hope is that this effort will result in collective entitlement being replaced by collective prohibition. By agreeing to such stringent nonproliferation commitments and achieving the favored nation clause, the UAE hopes that it has succeeded in placing restraints against any future Iranian nuclear agreement and holding the United States to its commitments. Ambassador Al Otaiba stated that Emirati voluntary commitments exceeded commitments secured from Iran in the JCPOA, and that if Iran is serious about its non-nuclear intentions, as its leadership has declared on multiple occasions, then “signing onto the same voluntary commitments as the UAE” would be the clearest signal of its intentions.19 The likelihood of an Iran nuclear agreement unfolding in this manner is slim, but the UAE does retain the right to renegotiate its deal if the United States strikes a better one with another state. It is in the United States’ best interest to honor its commitments to the UAE, or risk opening a Pandora’s box of pushing nuclear boundaries. The UAE was not just benevolent in its disavowal of enrichment and reprocessing rights but also shrewd.

Since signing these nuclear agreements, Emirati leadership has continued to pursue behavioral norms consistent with its image as a collaborator. For instance, it has regularly called on international institutions as an arbiter in resolving conflicts and disputes. At the 2014 Nuclear Security Summit, Mohamed bin Zayed stated that international institutions must be empowered by the international community to reduce the number of nuclear weapons. He called for “international cooperation on nuclear security” to “develop the required infrastructure and human resources so as to guarantee the highest nuclear security in all countries.”20 The UAE sees itself as an active member of a regional and larger global community and declared that the country must not “exclude ourselves from the rest of the world with its concerns and issues but rather we must interact with it, share its concerns and help develop solutions and strategies.”21

The UAE considers itself a dynamic regional and international collaborator and has sought outside council and approval of its nuclear energy program from the very early stages. Committed to regional security, the UAE is aware that its program is setting a regional and international precedent, and in so doing it has sought to normalize the intentional omission of a weapons component to future nuclear energy programs, enhancing the security and stability in the region.

UAE and the United States: Conventional Military Collaboration and Interoperation

In the Cultural Topography Framework, value is defined as something that elevates the status of group members. Valued items can be ideational or material. In this section, we will focus on ideational value that the Emirati state places on its conventional military forces and the ability of the Emirati military to interoperate with the U.S. military. The particular domain of the Cultural Topography Framework—the high value placed on conventional military capabilities— is especially visible though the Emirati national role of collaborator.

The value the UAE places in its conventional military forces and in its military partnership with the United States serves as a fundamental pillar of its security and foreign policy. The UAE’s proficient conventional military forces enhance its security status globally and aid in displacing the perceived need for a nuclear weapons program. Emirati leadership employs full confidence in its armed forces to secure the state, absent the supplement of nuclear weapons, and its standing has been enhanced worldwide due to its potent proficiency. Mohamed bin Zayed has boasted “limitless” faith and confidence in UAE’s armed forces, describing them as the “cornerstone” in his strategic vision for the next 50 years, and referring to them as “the shield of our nation and source of its pride.”22 U.S. military officials and policy analysts have echoed this esteem: U.S. Marine Corps general and former U.S. secretary of defense James N. Mattis dubbed them “Little Sparta” and regional military expert Kenneth M. Pollack described them as the “most capable in the Arab world.”23 One study from 2020 claimed that the amphibious landing and subsequent counterinsurgency operations conducted by UAE forces in Yemen exhibited aptitude surpassing many North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) nations.24 The high esteem for the UAE military is the result of collaborative combat operations in Bosnia, Afghanistan, Syria, and Yemen. In Syria, UAE pilots were second only to the United States in the number of sorties flown against Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (ISIS) targets and in Afghanistan it flew close air support for U.S. ground units—one of only two non-NATO forces trusted to do so.25 The UAE armed forces would not have achieved the current level of battlefield success without substantive interoperational experiences with more advanced militaries. As the UAE pursues the reputation of an undeniable military power, it has regularly sought opportunities to interoperate with key partners, filling critical roles in NATO missions in Afghanistan and against ISIS in Syria. UAE armed forces have been party to six military operations alongside the United States, with members of bin Zayed’s Presidential Guards—its most elite fighting force built on the model of the Marine Corps—deployed for 12 years on the ground and in the skies over Afghanistan.26 Interoperation is further facilitated by the presence of U.S. military forces on Emirati soil. Al Dhafra Air Base in Abu Dhabi has been home to more than 5,000 U.S. military personnel, and Jebel Ali free trade zone in Dubai is the most frequently called on port for U.S. Navy forces outside of the United States.27 The two countries take part in joint military exercises annually and further formalized cooperation under the Defense Cooperation Agreement (DCA) in 2017, designed to enhance military interoperability and security in the region. A founding pillar of the DCA is to deter Iranian aggression and nuclear proliferation.28 The linchpin to UAE interoperation with the U.S. military is achieving proficiency on the most advanced military hardware in the U.S. military kit. Technological superiority is a principle that the Emirati armed forces were built on and remains necessary for the efficient projection of force outside Emirati borders.29 In 2021, the UAE inked an arms deal for 50 Lockheed Martin F-35 Lightning II fighter jets and 18 General Atomics MQ-9 Reaper drones, worth $23 billion USD.30 Possession of advanced weaponry is insufficient to deter aggression and secure stability. Emirati armed forces train and master proficiency on this equipment to such an extent that would allow confident interoperation in combat operations. The UAE perceives an engaged United States as essential for regional stability and considers itself a guardian of that sustained engagement.31 The U.S.– UAE military cooperation has acted as the vehicle for further collaboration. Strong military ties are not the by-product of close collaboration but the impetus for it. This collaboration reflects three elements of Emirati strategic culture that deter it from nuclear acquisition or proliferation, two of which have been discussed: the value of conventional military forces that offsets perceived needs of a nuclear weapon and the valuing of interoperability with U.S. military forces as an enhancement to Emirati status globally and a deterrent in its own right. The third is UAE’s perception of its inclusion within U.S. extended deterrence, neutralizing the need to pursue its own weapon. The United States has not issued the UAE specific security guarantees in the form of official treaties, and it has not conferred on the UAE the status of major non-NATO ally, which grants exclusive military considerations for states outside of NATO. But it has called the Emirati state a “major security partner” and gone lengths to both reassure the UAE and dissuade potential adversaries through extended deterrence, specifically an enduring local military presence, significant military sales, and joint military operations.32 U.S. extended deterrence conveys to an adversarial country that the costs of striking a U.S. ally would be untenably high and elicit a severe response. Extended deterrence encompasses a spectrum of arrangements, from declarations of protection to the placement of nuclear weapons within the borders of an allied country.33 Conventional forces do not in and of themselves carry the same weight as a nuclear deterrent, but the caliber of the U.S.-UAE military alliance acts as a deterring force in the region. The confluence of U.S. military presence, substantial military sales, the UAE’s demonstrated skill in operating and deploying purchased weaponry, regular joint military exercises, and formal military agreements falls on the deterrence spectrum. Ambassador Al Otaiba expressed these sentiments when he stated that the F-35 Joint Strike Fighter sale went beyond an arms deal, that at its core it was a “deterrent against aggression” and would enhance U.S. and Emirati interoperation.34 A highly skilled, battle-tested, well-armed American ally on the Arabian Peninsula is a redoubtable counterweight to Iran. General Kenneth F. McKenzie Jr., Marine Corps commander of U.S. Central Command, stated as much in testimony to the House Armed Services Committee, testifying that providing our allies with “the best capability we can afford to give them” is a key tenant in the deterrence of Iran.35 The sweeping commitments the UAE has made to regional stability would be irrelevant if the Emirati state calculated it necessary to pursue a nuclear weapon as a means of defending itself. Coverage under an iteration of extended U.S. deterrence goes a long way in safeguarding this calculus.

Emirati Leadership: Innovation, Not Proliferation

The UAE considers itself a regional and even global leader in technological innovation and social progress.36 According to NRC theory, national leader roles, both regional and global, have a tendency to gravitate toward nuclear proliferation because “most states perceive nuclear weapons to be a symbol of leadership based on the model of legal nuclear weapons states,” and regional and global leaders may also believe nuclear weapons are necessary to protect their region.37 In the UAE’s case, however, pursuit of a military component to its civil energy program would create regional instability and would undermine the progress and stability Emiratis are aiming for in seeking regional leadership. The UAE has achieved several Arab firsts, the latest of which was sending a space probe to Mars. Addressing the successful entrance of the Hope probe into the Martian atmosphere, Mohamed bin Zayed said, “the UAE of the future will lead the region’s scientific and knowledge development. Our institutions are open for youth across the Arab world to be part of this journey.”38 The mission to Mars was more than 10 years in the making and intended as a mechanism to empower Emirati people and establish indigenous capabilities to succeed in leading the Arab state to the most elevated levels of scientific and technical achievement.39

The UAE also prides itself on being the regional leader in tolerance, declaring 2019 as the “Year of Tolerance,” which saw the first visit of a Vatican pope to an Arab state. In hosting Pope Francis, the UAE intended to showcase its impressive diversity credentials, signaling to the world that the UAE is a safe destination for peoples of all races and religions. This was more than a gesture of goodwill to the Christians in the region and the globe; it was also a bold rebuttal to extremism.40 Emirati leadership takes pride in promoting a moderate version of Islam that champions the inclusion of women, promotes innovation, encourages engagement, and respects all faiths.41

As noted at the beginning of this article, identity within the Cultural Topography Framework is self-ascribed, celebrating traits that the group assigns itself. The UAE’s self conception of being inclusive to people of diverse backgrounds is relative to the region in which it resides and illustrates the Emirati narrative of self, exhibiting some genuine reforms, while also falling well below Western standards of tolerance and inclusion of minority groups. While efforts have been made to accommodate members of a wider spread of religions, only 10 percent of the population of the Emirati state holds citizenship and its associated privileges. Migrant workers, who make up roughly 90 percent of the Emirati population, cannot quit or change positions without the permission of their employer, are not allowed to join labor unions, and are not guaranteed a minimum pay rate.42

An Emirati norm that is crucial to its own stability, as well as regional stability, is providing an alternative Islamic vision for and investment in its youth population. This new vision of Islam revises Islamic teachings in schools, retrains imams (Islamic leader), and updates Quranic commentaries to reflect a modern, future-oriented religion. The UAE goes so far as to license its imams, comparing the practice to a mechanism for safety, similar to the licensing of pilots. The UAE has established professional institutions that combat extremist recruitment and propaganda, providing communities with the tools to counter radicalization. Illustrating its commitments to enhancing regional stability, the UAE has exported these skill sets throughout the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region to include Afghanistan, Pakistan, and Nigeria.43

The UAE considers itself a leader in the field of gender equality, embracing norms that reinforce this image. Emirati women are granted equal rights under the law, access to education, claim to titles, and the right to inheritances. In the UAE, women hold two-thirds of government jobs, 36 percent of the Emirati cabinet, own 10 percent of the private wealth, and account for 70 percent of university graduates.44 Women serve in the armed forces, and the first Emirati military strikes on ISIS targets were led by Major Mariam al Mansouri, the first female to join the Emirati Air Force.45

Emirati leadership hails these leading innovations as “road maps,” “beacons of stability,” “hope,” and a bridge to other regions.46 These leadership identity markers in innovation and social progress act as additional deterrents rather than accelerants of potential nuclear proliferation. Stability, not turbulence, will allow the United Arab Emirates to continue to make strides in its innovative efforts. The nonproliferation lengths the UAE has taken will cultivate an environment that will facilitate its technological progress and attract collaboration from influential partners. If the UAE were to be the state to introduce proliferation as a norm in the Gulf region, it is unlikely that it would continue to attract the alliances and dynamic collaborations that have allowed it to flex its regional leadership credentials. The areas in which the UAE exerts regional leadership— in the science and technology sectors and the promotion of religious tolerance—sync with its ambition to become a leader in nuclear energy, but not in nuclear proliferation.

The UAE and Iran: Collaborate to Deescalate

The perceptual lens through which Emirati leadership assesses the threat posed by Iran leads it to value both collaborative and conventional strategies to contain Iranian ambitions, rather than a strategy that might involve nuclear weapons acquisition. A crucial distinction to be made in analyzing Emirati threat perception of Iran is its view that Iran’s destabilizing conduct and swelling hegemonic status throughout the Arab world, is of much greater threat to the Emirati state and Gulf region than its nuclear weapons program.47 The rise of Iranian influence throughout the region has typically drawn a harsh rebuke from the UAE, which perceives Iran and its brand of Shia Islam as an existential threat to the security of the state.48

The UAE has decried Iran’s “flagrant meddling,” “blatant interference,” and intent to sow sedition and malcontent throughout the Arabian Peninsula as a means of expanding its revolutionary brand of Shia Islam beyond its borders.49 Ambassador Al Otaiba lamented, “In Palestine, in Iraq, and in almost every country in the region, Iran is funding, arming, and enabling radical, violent, and subversive cells.”50 The UAE was a vocal critic of the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA)—the nuclear agreement aimed at dismantling Iran’s nuclear weapons program—declaring itself overall disappointed with the agreement, and described Iran as “hostile, expansionist, violent . . . and as dangerous as ever” one year after its signing. It was only one of four countries to support the U.S. withdrawal from the JCPOA, calling President Donald J. Trump’s decision “the correct one” and urging the international community to support the American president in his efforts to enhance the security of the Middle East.51

Tehran’s practice of backing minority Shia uprisings throughout the region is especially alarming to the UAE, which is home to roughly 600,000 Iranians, more than 6 percent of the entire population of the Emirati state.52 UAE leadership has raised concerns that adherents of Shia Islam are more loyal to Iran than their home states due to Shia “veneration of religious figures.”53

Geographical proximity, U.S. military presence on Emirati soil, along with the substantial Shia population prompts Emirati leadership to consider itself the “most vulnerable” state to an Iranian threat. Ambassador Al Otaiba expanded on this sentiment:

Our military, who has existed for the past 40 years, wake up, dream, breathe, eat, sleep the Iranian threat. It’s the only conventional military threat our military plans for, trains for, equips for, that’s it, there’s no other threat, there’s no country in the region that is a threat to the U.A.E., it’s only Iran.54

Despite these serious accusations and seemingly fundamental differences in acceptable behaviors, the UAE has flexed it credentials as a collaborator, even with Iran.

The Emirati approach to countering Iran is typically a measured one. Public remarks illustrate the Emirati preference to collaborate when confronting Iran.55 This is reflective of a realistic reading of the region; Iran is not an enemy to defeat but a rival state that must somehow fill a role and function within the region, and international consensus and pressure aids in enhancing the chances of Iranian receptivity to abiding by international norms. While the UAE has employed a historically hard-line approach on Iran and has demonstrated its willingness to engage in armed conflict against Iranian proxies, it has never called for military strikes against Iran on Iranian soil, despite Iranian occupation of three Emirati islands during the past 50 years. In fact, it has cautioned against military strikes, instead defaulting to influence and collaboration through and with allies and institutions. In 2019, when the Saudi Arabian Oil Company (Aramco) facilities in Abqaiq was the target of a sophisticated drone attack, ultimately attributed to Iran, the UAE collaborated with three European nations, the United Kingdom, France, and Germany, in lowering tensions and preventing further military escalation in the region, stating that “at every turn the UAE has avoided conflict with Iran.”56

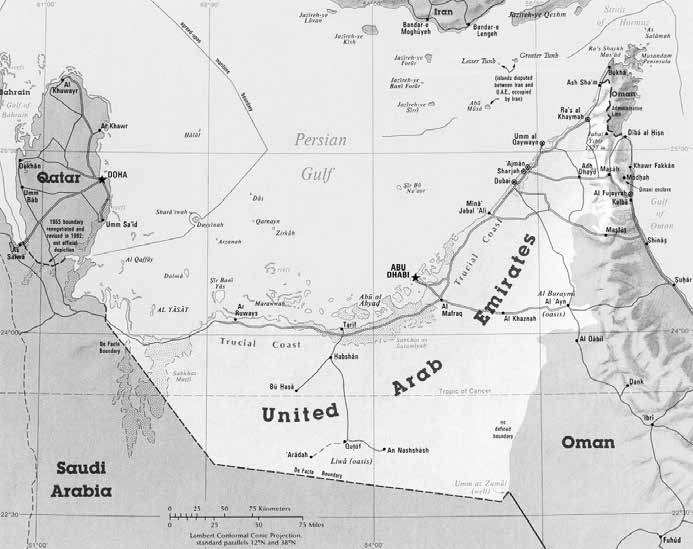

Map 1. Map of the Persian Gulf region, illustrating the geographic proximity between the UAE and Iran, as well as the three disputed islands: Lesser Tunb, Greater Tunb, and Abu Musa

Source: courtesy of the author, adapted by MCUP.

During the last year and a half, the UAE has perceived the coronavirus climate as a way to balance its aggressive approach with a more pragmatic one. The UAE delivered 56 tons of medical supplies to Iran, as well as chartering flights for medical personnel to assist in Iran’s coronavirus crisis when Iran was record-ing the seventh highest number of cases globally. The UAE called the cooperation between the two countries “a privilege.”57 UAE foreign minister Abdullah bin Zayed and his Iranian counterpart Mohammad Javad Zarif met by video conference to discuss effective responses to the coronavirus—a rare display of normalized bilateral discussions. The leaders vowed to continue discussions on “tough challenges and tougher choices ahead,” possibly referring to the break-down of the JCPOA and Iran’s uranium enrichment program.58 Emirati efforts to engage with Iran on coronavirus assistance were received well by Iran and went beyond the strict parameters of humanitarian aid, with Zarif admitting that the UAE and Iran’s relationship had developed “more reason and logic.”59

The coronavirus pandemic prompted the UAE to collaborate directly with Iran in assisting the state as it struggled to meet the needs of its population. The only action the UAE has taken to address the half-century occupation of three of its islands—Abu Musa and the Greater and Less Tunbs—has been to call on the United Nations (UN) to facilitate dialogue. When U.S. airstrikes led to the death of Quds Force commander General Qassem Soleimani, Emirati officials called for de-escalation, urging each side to exercise wisdom and political solutions rather than military confrontation.60 Emirati statements and behavior indicate that its perception of Iran and the best means for managing it as a threat is pragmatic and flexible. While the UAE considers Iran’s interference in sovereign affairs throughout the region as a major threat to regional and Emirati security, a rigid and singular approach is weighted with just as much risk.

Instead, the UAE has endeavored to maintain a functional relationship with Iran, such as the cooperation they have exhibited during the Covid-19 pandemic, advocating for reasoned responses to Iranian aggression, while still maintaining close ties with the United States and displaying its conventional military capabilities through interoperation with the U.S. military. This multi-pronged approach to countering Iranian hegemony, coupled with heavy U.S. engagement, currently satisfies Emirati security needs in terms of its ability to deter Iranian aggression, in lieu of nuclear weapons. Essential to maintaining this precariously balanced status quo is an engaged U.S. government and military. Disengaging with this particular ally and failing to hold subsequent nu-clear agreements to the same standards could shift the security paradigm to the extent that conventional military means and measured responses to Iranian aggression are not satisfactory security guarantees.

Conclusion

Matthew Berrett, a former assistant director of the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) and one of the architects of the Cultural Topography Framework meth-od, points out that U.S. policy makers rarely ask a critical question: whether U.S. foreign policy successes would require fundamental cultural change in a partner or adversarial nation, and if that answer is yes—as it so often is—what resources, if any, would be sufficient to spur the cultural transformation. This article concludes that in terms of containing nuclear proliferation, U.S. non-proliferation goals in the region would not require cultural conversion within the UAE. The national role conception and strategic culture of the UAE steer it away from nuclear acquisition for its own reasons. That said, continuing U.S. engagement with the UAE and the Middle East region is key to the Emirati strategic calculus. Emirati leadership has stressed the importance of U.S. collaboration in a multitude of interviews, discussions, and speeches. It considers U.S. engagement as a necessary powerful pillar of stability. In the UAE, the United States has a willing and culturally aligned partner. The United Arab Emirates considers itself an effective collaborator, committed to creating strong communities that reject extremist ideologies, regional interference, and nuclear proliferation. Through intentional and culturally informed engagement, the United States can channel these Emirati cultural markers into effective policy for security; disengagement risks alienating one of its most stable partners in the region and upsetting a calculus that currently acts to inhibit proliferation.

Endnotes

- “Statement by HH Sheikh Mohamed bin Zayed al Nahyan, Crown Prince of Abu Dhabi and Deputy Supreme Commander of the UAE Armed Forces, on the 40th Anniversary of the Unification of the UAE Armed Forces” (speech, Crown Prince Court, UAE, 5 May 2016); “Statement by Mohamed bin Zayed on the Occasion of the 43rd Anniversary of UAE National Day” (speech, Crown Prince Court, UAE, 1 December 2014), hereafter bin Zayed 43rd Anniversary statement; and “UAE, Saudi Nuclear Regulators Strengthen Cooperation,” World Nuclear News, 16 November 2020.

- Michael Laufer, “AQ Khan Nuclear Chronology,” Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, 7 September 2005.

- Ed Markey, “Markey: UAE Nuclear Agreement a Bad Deal for the US,” press release, United States Senator for Massachusetts, 8 July 2009.

- “Nuclear Fuel Assemblies for the UAE,” Emirates Nuclear Energy Corporation, accessed 5 December 2021

- Glenn Chaffetz, Hillel Abramson, and Suzette Grillot, Culture and Foreign Policy, ed. Valerie Hudson (London: Lynn Reinner Publishers, 1997), 174.

- Matthew T. Barrett and Jeannie L. Johnson, “Cultural Topography: A New Research Tool for Intelligence Analysis,” Studies in Intelligence 55, no. 2 (June 2011): 6.

- Sources for this article were largely evaluated in translated Arabic rather than native Arabic. The remarks covered in the data set are the words, ideas, and perceptions of Emirati leaders; they are not neutral comments but vocal reflections of an actor’s identity containing their own personal biases.

- Chaffetz, Abramson, and Grillot, Culture and Foreign Policy, 175.

- “UAE Well Positioned to Build Knowledge-Based Economy: Mohammed bin Zayed,” Crown Prince Court, accessed 3 April 2021; “Abdullah bin Zayed Meets with US Administration Officials in Washington DC,” Embassy of the United Arab Emirates, accessed 2 April 2021; and “UAE Ambassador Yousef Al Otaiba Visits Cleveland to Highlight Ohio-UAE Ties,” Embassy of the United Arab Emirates, 21 June 2018.

- “UAE Government Releases Comprehensive Policy White Paper on the Evaluation and Potential Development of Peaceful Nuclear Energy,” Embassy of the United Arab Emirates, 20 April 2008, hereafter “UAE White Paper.”

- The U.S.-UAE 123 Agreement is so named based on Section 123 of the U.S. Atomic Energy Act. “U.S.-UAE Agreement for Peaceful Nuclear Cooperation (123 Agreement),” press release, State Department, 15 January 2009.

- “Berman Introduces Resolution Approving U.S.-UAE Civilian Nuclear Cooperation,” press release, United States House of Representatives Committee on Foreign Affairs, House Committee on Foreign Affairs, 14 July 2009.

- Agreement for Cooperation Between the Government of the United States and the Government of the United Arab Emirates, 111th Cong. (21 May 2009).

- “UAE White Paper.”

- Protocol Additional to the Agreement between the United Arab Emirates and the International Atomic Energy Agency for the Application of Safeguards in Connection with the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons, INFCIRC/622/Add.1 (Vienna Austria: IAEA, 2011).

- “UAE White Paper.”

- Fred McGoldrick, The U.S.–UAE Peaceful Nuclear Cooperation Agreement: Gold Standard or Fools Gold? (Washington, DC: Center for Strategic and International Studies, 2010).

- David D. Kirkpatrick, “The Most Powerful Arab Ruler Isn’t M.B.S. It’s M.B.Z.,” New York Times, 2 June 2019.

- Yousef Al Otaiba, “A Successful Mideast Peace Deal,” Wall Street Journal, 4 March 2020.

- “Mohamed bin Zayed Meets Barack Obama,” Emirates 24/7, 25 March 2014.

- bin Zayed 43rd Anniversary statement.

- For the purpose of this article, conventional military power is classified as combat actions carried out by Emirati ground, air, and amphibious forces in direct engagement with a well-defined enemy. The Emirati state has used conventional forces in unconventional classifications of war, such as in the counterinsurgency in Yemen, but still relied heavily on its traditional infantry, armor, and air combat roles. “Our Armed Forces will be Cornerstone of UAE’s Strategic Plans for 50 Years, Says Mohamed bin Zayed on 44th Unification Day,” Emirates News Agency, 5 May 2020.

- “The Gulf’s ‘Little Sparta’: The Ambitious United Arab Emirates,” Economist, 8 April 2017; and Kenneth M. Pollack, Sizing up Little Sparta: Understanding UAE Military Effectiveness (Washington, DC: American Enterprise Institute, 2020).

- David B. Roberts, “Bucking the Trend: The UAE and the Development of Military Capabilities in the Arab World,” Security Studies 29, no. 2 (February 2020): 301–44, https://doi.org/10.1080/09636412.2020.1722852.

- Roberts, “Bucking the Trend.” The other non-NATO military was Australia.

- “UAE-U.S. Security Relationship,” Embassy of the United Arab Emirates, Washington, DC, accessed 28 July 2021.

- Kenneth Katzman, The United Arab Emirates (UAE): Issues for US Policy (Washington, DC: Congressional Research Service, 2021).

- Katzman, The United Arab Emirates (UAE), 14–17.

- “Mohamed bin Zayed: Our Armed Forces Will Steadily Progress to be an Extraordinary Force Able to Face All Threats,” Emirates News Agency, 5 May 2016.

- Mike Stone, “UAE Signs Deal with U.S. to Buy 50 F-35 Jets and Up to 18 Drones: Sources,” Reuters, 20 January 2021.

- Yousef Al Otaiba, “The Asia Pivot Needs a Firm Footing in the Middle East,” Foreign Policy, 26 March 2014.

- Jon Gambrell, “US Calls Bahrain, UAE ‘Major Security Partners’,” Associated Press, 16 January 2021.

- Bruno Tertrais, “Security Guarantees and Extended Deterrence in the Gulf Region: A European Perspective,” Strategic Insights 8, no. 5 (Winter 2009).

- “The UAE and the F-35: Frontline Defense for the UAE, US and Partners,” Embassy of the United Arab Emirates, accessed 7 December 2021.

- “The UAE and the F-35.”

- “Commemoration Day: UAE Leaders Pay Tribute to Nation’s Martyrs,” Khaleej Times (Dubai), 28 November 2020.

- Chaffetz, Abramson, and Grillot, Culture and Foreign Policy, 175.

- Angel Tesorero, “Watch: UAE Leaders Honor Hope Probe Team During Ministerial Retreat,” Gulf News (Dubai), 23 February 2021.

- “Video: UAE Leaders Honour the Hope Probe Team,” Gulf Today (Dubai), 24 February 2021.

- Yousef Al Otaiba, “Why We Invited the Pope to the Arabian Peninsula,” Politico, 2 February 2019.

- Yousef Al Otaiba, “A New Middle East: Rhodes Scholars, Not Radicals,” Rand (blog), 2 June 2016; and Yousef Al Otaiba, “A Vision for a Moderate, Modern Muslim World,” Foreign Policy, 2 December 2015.

- “International Migrant Stock, Total,” World Bank, accessed 8 December 2021; and Kali Robinson, “What Is the Kafala System,” Council on Foreign Relations, 23 March 2021.

- Yousef Al Otaiba, “A Positive Agenda for the Middle East,” Center for Strategic and International Studies, accessed 3 April 2021; and Kathy Gilsinan and Jeffrey Goldberg, “Emirati Ambassador: Qatar Is a Destructive Force in the Region,” Atlantic, 28 August 2017

- “Women in the UAE,” United Arab Emirates Embassy, Washington, DC, accessed 10 April 2021.

- Susanna Kim, “Meet the Female Pilot Who Led Airstrike on ISIS,” ABC News, 25 September 2014.

- “Commemoration Day.”

- Al Otaiba, “A Positive Agenda.”

- Peter Salisbury, Risk Perception and Appetite in UAE Foreign Policy and National Security (London: Chatham House, 2020).

- “Statement by His Highness Sheikh Abdullah bin Zayed Al Nahyan Minister of Foreign Affairs Before the General Debate of the 75th Session of the United Nations General Assembly” (speech, UAE Ministry of Foreign Affairs and International Cooperation, New York, 29 September 2020).

- Al Otaiba, “A Positive Agenda.”

- Yousef Al Otaiba, “One Year after the Iran Nuclear Deal,” Wall Street Journal, 3 April 2016. The four countries to support withdrawal from the JCPOA were Israel, Saudi Arabia, Bahrain, and the UAE.

- Salisbury, “Risk Perception and Appetite”; and Adam Taylor, “The Once Flourishing Iranian Community in Dubai Faces Pressure Amid Persian Gulf Tensions,” Washington Post, 13 August 2019.

- “General Abizaid Meeting with Abu Dhabi Crown Prince and Dubai Crown Prince,” Wikileaks, 2 January 2006.

- Jeffrey Goldberg, “UAE’s Ambassador Endorses an American Strike on Iran,” Atlantic, 6 July 2010.

- Yousef Al Otabia, “UAE Statement on Iran New Iran Sanctions,” United Arab Emirates Embassy, Washington, DC, 4 November 2018; and “UAE Says It’s Committed to Working with US to Reduce Regional Tensions—State News Agency,” Reuters, 6 February 2021.

- “H.E. Dr. Anwar Gargash Op-Ed: How to Reduce Gulf Tensions with Iran,” Embassy of the United Arab Emirates, 29 September 2019.

- “UAE Sends Supplies to Aid Iran in Coronavirus Fight,” Arab News, 17 March 2020; “UAE Sends Additional Aid to Iran in Fight Against Covid-19,” press release, Unit-ed Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs, 17 June 2020; and “Video: UAE Delivers 7.5 Tonnes of Aid to Iran to Fight Covid-19,” Gulf News (Dubai), 2 March 2020.

- Georgio Cafiero and Sina Azodi, “The United Arab Emirate’s Flexible Approach to Iran,” Center for Iranian Studies in Ankara, 10 September 2020; and “In Rare Talks, Iran and UAE Foreign Ministers Discuss Covid-19,” Al Jazeera, 2 August 2020.

- Golnar Movevalli and Arsalan Shahla, “Iran Says Virus Coordination Has Improved Its Ties with the UAE,” Bloomberg, 6 April 2020.

- “UAE Calls for Wisdom to Avert Confrontation, After Iranian Commander Killed,” Reuters, 3 January 2020.