Abstract: This article examines the early foundations of the strategic culture of the Pakistan Army. By exploring the impact of the partition of British India in 1947 and the First Kashmir War of 1947–48, the article identifies the pivotal factors in the development of strategic culture of Pakistan. In also examining Pakistani fears of a “vengeful” Hindu India and a persistence in the belief of discredited martial race theories as well as the idea of a Muslim military exceptionalism, the article concludes that the foundation of this culture remains evident while it is also malleable to contemporaneous events.

Keywords: Pakistan Army, martial race, Kashmir, partition, Mohammed Ali Jinnah, Mohammed Ayub Khan, British Indian Army, Punjabi, Pakhtun/Pashtun, Islamic martial myths, irredentist, Islam in danger, India, Afghanistan

The professional soldier in a Muslim army, pursuing the goals of a Muslim state, CANNOT become “professional” if in all his activities he does not take on“the color of Allah.”

~ General Mohammed Zia ul-Haq1

Introduction

This article examines the causational factors that contributed to the early establishment of a Pakistani strategic culture. Given that Pakistan is a new postcolonial nation-state not yet 75 years old, the focus of this article is on the important formative period of Pakistan in which the contours of this strategic culture were established. The focus is on the Pakistan Army as it has been arguably the preeminent military and political actor since the state’s formation in 1947. The article argues that this strategic culture arose out of three initial pivotal influences in 1947–48, followed by other key events that include significantly the “strategic shock” suffered by Pakistan in 1971 when the state was divided into two, and followed soon after by the impact of Islamization of the military.2 The foundational influences of a Pakistani strategic culture were first the traumatic impact of partition, second the perpetuation of beliefs in an Islamic military exceptionalism drawing on discredited theories of martial race, and third the impact of the 1947–48 First Kashmir War and the notion of “Islam in danger.”3 The convergence of these three elements were the foundations of a Pakistan strategic culture with the Pakistan Army Officer Corps, its primary initiator. Closely aligned to this and a key pillar of the strategic culture of Pakistan is the idea of a vengeful and irredentist India, the need for strategic depth and its concomitant need for a pliant Afghanistan, and an agile adoption of political realism from the state’s very beginning. This realism in seeking any leverage or advantage over its existential rival, India, which saw Pakistan’s early alliance to the United States during the Cold War, its courting of China even when Pakistan was a member of the Southeast Asia Treaty Organization (SEATO) pact, and the strategic shock of the loss of East Pakistan and the significant cultural change it inspired in the army. It is important to note that the Pakistan Army from its outset has consistently conflated notions of the discredited martial race theory, which posits that certain races such as the Punjabi Muslim and Pashtun Muslim and other designated ethnicities and groups are more effective in the military than others. The Pakistan Army have consistently drawn from admixtures of martial race and Islam as the basis of the army’s superiority in comparison to other armies—most notably the Indian Army. Apart from the relationship between martial race and Islam, the article also draws links between Islam and several other significant influences on the army. Strategic culture is an appropriate prism in which to understand the security features of Pakistan. Strategic culture theory highlights the relevance of an organization’s history, myths, and development and therefore this article’s focus looks to the beginnings of the postcolonial state and the formative influences and inheritances that had an impact on the dominant institution of that state— the army. Together these are of importance in the establishment and evolution of the strategic culture of Pakistan, where the tumultuous nature of its establishment and formation in 1947 left a pivotal and enduring legacy on Pakistan. Strategic culture theory argues the importance of major strategic shocks and disasters on an organization. In this way, the article argues that the trials and tribulations of partition and the First Kashmir War, the Second Kashmir War of 1965, and above all the strategic shock suffered in the Pakistan Army’s humiliating defeat to India in 1971 to the present post–Global War on Terrorism age were influential in shaping an army strategic culture with specific attributes, some static and others evolving.

What is Strategic Culture?

Strategic culture has experienced several developments since its first iteration. A strategic culture can be defined as a theory that argues that there are distinctive national styles in security and military affairs. There have been studies on a number of strategic cultures, for example, Israel, Iran, and France.4 The provenance of strategic culture effectively begins in the 1930s with B. H. Liddell-Hart’s theorizing of a traditional British way of warfare, while Ken Booth appealed in the late 1970s for strategists to be more conscious of their cultural context in their thinking.5 The term strategic culture dates back to the 1970s in Jack Snyder’s explanation of Soviet strategy.6 Strategic styles are rooted in historical experience and influenced by the nature of the nation or organization’s history, which has been involved in the state’s defense and are influenced by major disruptions or disasters that occur to the state, society, or organization.7 Booth’s definition of strategic culture is helpful:

A nation’s traditions, values, attitudes, patterns of behaviour, habits, customs, achievement and particular ways of adapting to the environment and solving problems with respect to the threat or use of force.8

The article considers these elements in how the army’s strategic culture is rooted in historical experience in a state with even a relatively short modern history. This article will illustrate how events such as the formation of the army from the Muslim elements of the British Indian Army, the First Kashmir War, the Second Kashmir War, the Indo-Pakistani War, and the formation of Bangladesh (formerly East Pakistan), as well as other major events such as the Russian invasion of Afghanistan and the impact of the 11 September 2001 terrorist attacks in the United States have influenced the role of Islam in the Pakistan Army. The contours of Pakistani strategic culture have been described previously by Feroz Hasan Khan and Peter R. Lavoy, though these scholars’ purpose was not to provide a sustained analysis of Islam or its role in Pakistan’s strategic culture over the course of its history as this article seeks to perform, while Hasan Askari Rizvi importantly recognizes the impact of realism.9

Historical experiences, perceptions of the adversary and a conception of self—the determinants of strategic culture—are relatively permanent, but each crisis may be totally or partly different . . . at times, the strategic cultural perspective and the dictates of realism may lead to the same or similar policy measures.10

The dictates of realism have been a pivotal influence on a Pakistani strategic culture that has embraced entities such as the Taliban to pursue their interest and then putatively rejected them to fulfill new directions with the United States and the West. Lawrence Sondhaus argued that the role of supranational forces, such as Islamic fundamentalism, had influenced Arab and other Muslim states such as Pakistan and Iran. Sondhaus believes Islamic fundamentalism to have influenced these countries to behave in a manner contrary to their national interest, and in this he sees the influence of culture.11 This article also notes the influence of Islam on the army and its influence in seemingly irrational operations such as Operation Gibraltar, which inexorably led to the 1965 war with India as well as other flawed and outwardly counterintuitive operations such as the conflict that occurred in Kargil and clear evidence of support for terrorist entities.

National identities are forged out of adversity and the impact of the events of partition and the First Kashmir War acted powerfully on Pakistan in this way to establish an identity and strategic culture attached to Islam. The tragedies during this period established national myths and creation stories in which the army as a defender of Islam featured prominently.12 This was the case with Pakistan where the varied threats both real and imagined to the new nation’s existence were buried deep in the psyche of the first generation of Pakistan Army officers. These beliefs were transmitted to succeeding generations of officers.

Pakistan: Traumatic Beginnings and an Irredentist India?

Pakistan was created by Muhammed Ali Jinnah and the Muslim League’s efforts against the Indian National Congress and British opposition to create a Muslim homeland in the subcontinent. Pakistan consisted of two wings separated by more than a thousand miles of Indian territory and 356 million Indians.13 The new country of approximately 75 million people established its capital in Karachi in the western wing of the country.14 East Pakistan, the numerically greater of the two wings, consisted of 42 million people with a distinct cultural, linguistic, and demographic outlook that included a much larger percentage of non-Muslims than the Western wing.15 The new country with no authentic claims to a past history was immediately beset with internal and external problems ranging from the tensions inherent in its disparate ethnic, religious, and geographical divides to the geostrategic conundrums of being faced by a hostile India in the east, a hostile Afghanistan in the west, and an army initially still under the control of British commanders.

Though the Muslim League’s objective for Pakistan was achieved against significant obstacles, paradoxically on its achievement many Pakistanis believed their objective had not been fully realized. Many believed Pakistan to be partially fulfilled and that they had received far less than a Muslim homeland for the subcontinent’s Muslims with many Muslims still situated in what would be the new dominion of India. Pakistani’s referred to this as having received a “moth eaten” version of Pakistan. Pakistan, they believed, had been spoiled by alleged Indian recalcitrance, interference, and the failure to provide Pakistan its full territorial inheritance, which included parts of the Punjab, Kashmir, and some other areas.16 Because of this, an irredentist Hindu India bent on extinguishing the new state and its reabsorption into mother India was established as truth, at least in the beliefs of the political and military elite of Pakistan.17 The army believed India to be the core threat to the new Muslim state’s existence. This belief continues up to this third decade of the new millennium.

In this manner, the story and legends of the new army from its beginning focused on its Muslim character and its heroic achievements in overcoming the tribulations believed by the Pakistanis to have been thrust on it in these early years by a hostile, irredentist Hindu India. The exhilaration of Pakistan’s independence was further tempered by its tenuous claims to existence as a nation both contemporaneously and historically with its claims to be South Asia’s Muslim homeland belied by the fact that 35 million Muslims had remained in India. Indian diplomats astutely made it a point to remind others of India’s own Muslim heritage.18 The army, the most organized state entity with its claims to have defended the Muslim homeland against alleged Indian aggression in Kashmir, quickly established itself as the paramount institution of the new state and author of the context of its strategic culture.

This first generation of officers were trained and indoctrinated by the British within the multiethnic and religiously diverse British Indian Army. The Pakistan Army shed this diversity almost from its very beginning, despite Jinnah’s early desire for Pakistan’s national institutions to be representative of its minorities. The communal fears involved in partition acted on those Hindu officers in the army to seek their careers and security in India.19 The army quickly became an army of Muslims assured of their heritage as the “sword arm” of the Raj consisting largely of Muslim martial race soldiers from the Punjab and the at that time North-West Frontier Province (NWFP). The martial races thought of themselves as the “sword arm” of the Raj as they constituted nearly the entirety of the post-1857 British Indian Army, whereas many other Indian ethnicities, especially those from the south of India and East Pakistan, were considered by martial race theorists as not fit for military service.

Pakistan had become independent on 14 August 1947 amid tumultuous violence, territorial dispute, and recrimination with India about possession of capital assets and supplies left by the British.20 Born out of the exhaustion of Britain after World War II, which had at various times cajoled, threatened, and made promises of independence to India during the war, the two new states of Pakistan and India were born in an era of decolonization, nationalism, and the burgeoning Cold War environment. The success of Muhammad Ali Jinnah’s Muslim League in prevailing and obtaining independence on the basis of the two-nation theory of a homeland for the subcontinent’s Muslims was soured by disputes with India about the accession of a number of the princely states who were required to devolve their power to either Pakistan or India. The accession of Kashmir to India was met with outrage in Pakistan, which had expected to receive the territory of this Muslim majority state and Pakistan refused to recognize Kashmir’s accession and remains a lightning rod of grievance and a pillar of Pakistan’s strategic culture interests manipulated by military and political actors since this time.21

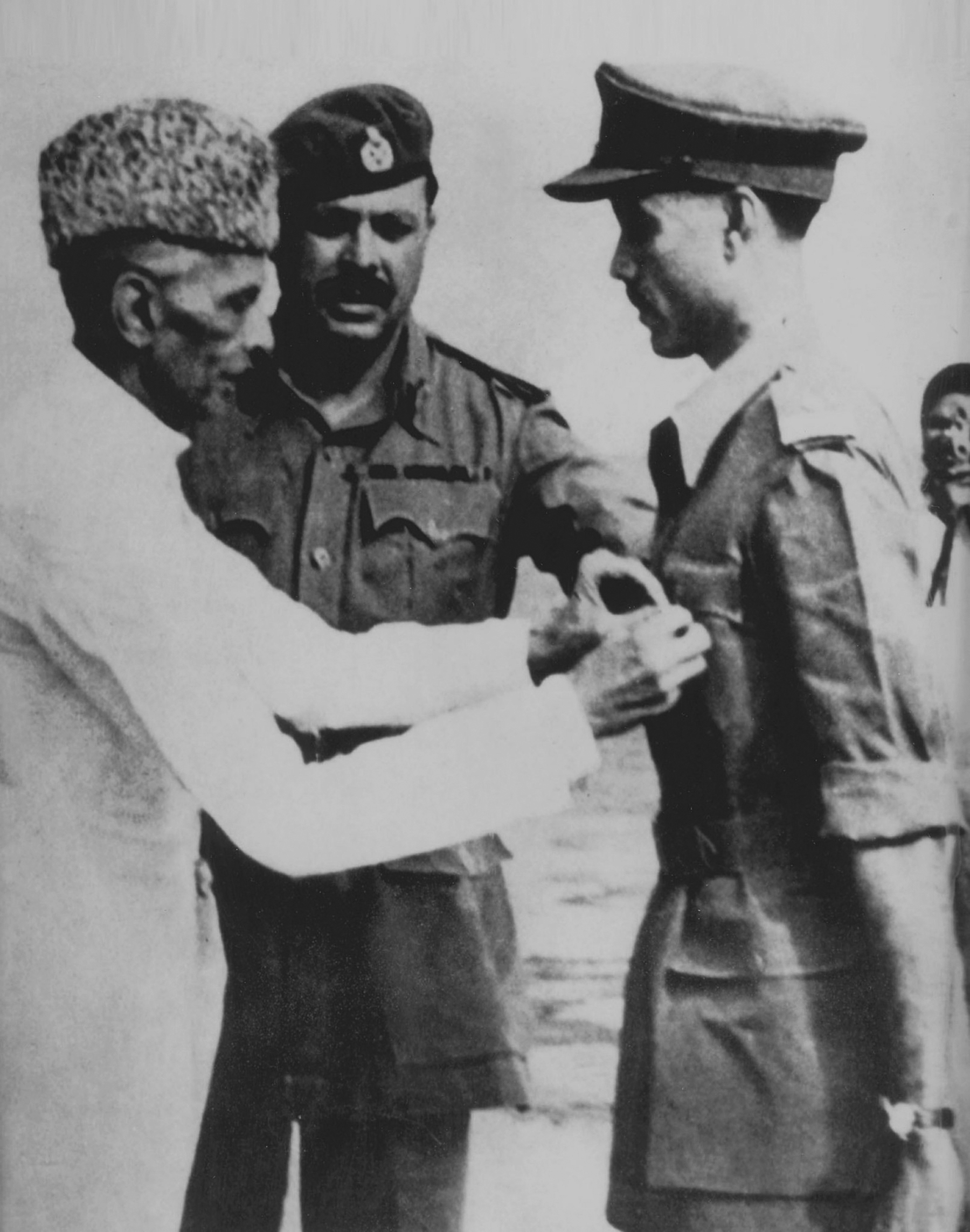

Figure 1. Architect of Pakistan’s strategic culture Ayub Khan (center) with founder of Pakistan Mohammed Ali Jinnah (left) decorating a soldier (1948, Dhaka)

Source: Dr. Ghulam Nabi Kazi

The invasion of Kashmir by tribal invaders that India alleged was orchestrated by the Pakistan Army was eventually repulsed in early November 1947 with India effectively gaining control of Jammu and Kashmir while Pakistan gained control of those areas it would describe as free or Azad Kashmir.22 Continued Pakistani protests at the United Nations (UN) resulted in a UN Security Council plan to hold a plebiscite in Kashmir in March 1948, which was never held, while it took until July 1949 for India and Pakistan to agree on a cease-fire line for Jammu and Kashmir. The UN mediator, Sir Owen Dixon, announced on 22 July 1950 his failure to bring India and Pakistan together to solve the Kashmir dispute.

The nebulous sense of identity for the new multiethnic state in which two wings of the country were separated by India was made apparent in March 1948 when Jinnah made a speech at Dacca University. Jinnah announced to an East Pakistani audience proud of their Bengali language and identity that Urdu, a language native to neither West nor East Pakistan, would be the national language for Pakistan. Later that same year, there were communal riots in Karachi involving many of the Muhajirs or Muslim settlers from India who The Foundations of Pakistan's Strategic Culture Journal of Advanced Military Studies had emigrated during partition, resulting in a state of emergency.23 To complicate the already tenuous existence of the new country, Jinnah—the architect of Pakistan—died in September 1948. Pakistan, already indignant at the loss of Kashmir, also protested to the United Nations concerning India’s invasion of Hyderabad, a Hindu majority state ruled by a Muslim, in August 1948.

Internationally, with a view to establishing its Muslim credentials, Pakistan hosted the first international Islamic conference in Karachi in December 1949. The leader of the Pakistan Muslim League, Chaudhry Khaliquzzaman, had also suggested a pan-Islamic unity of countries to be known as Islamistan.24 Pakistan and India also engaged in bilateral talks in 1949 concerning a host of disputes including Kashmir, evacuee property, and the Punjab water dispute concerning India stemming the flow of water into Pakistan.25

The disputes and enmities begun at independence continued into 1951 with Pakistan blaming India for inciting Afghan hostility against Pakistan. Belying Pakistan’s efforts with pan-Islamism unity was Muslim Afghanistan, which had not recognized Pakistan’s independence and held specific irredentist claims on Pakistani territory that Britain had taken from Afghanistan. This further amplified Pakistan’s concerns of two rapacious neighbors and their territorial claims on the new sovereign state. India had also, to Pakistan’s mind, provocatively hosted the all-India Pashtun jirga in Delhi, as well as allowing the Afghan ambassador to use All India Radio to deliver an anti-Pakistan speech in May 1951. Pakistan’s woes continued with the assassination of Liaquat Ali Khan in October 1951. After Jinnah, Khan was perhaps Pakistan’s most able politician capable of articulating a coherent vision and identity for Pakistan.

Pakistan’s formation and identity were loosely tied to the idea of a Muslim homeland by a secular elite that had largely not been supported by the ulema of the day while a Pakistan identity was still being negotiated.26 Those interested in pursuing a more Islamic basis to the state moved toward this objective almost from independence. Many ulema, including Abu al-A’la al-Mawdudi, the founder of Jama’at-e-Islami, had been opposed to Jinnah and felt that he aimed to secularize the Muslims of India, while nationalist Muslims were opposed to the idea of Pakistan as proposed by the Muslim League.27 Some Muslims felt even more strongly and described Jinnah in hostile terms as the great Kafir-eAzam (“the greatest of infidels”). Despite this opposition, many north Indian ulema, including Maududi, joined the mass migration to Pakistan during partition and some ulema who had become members of the league pushed for the adoption of an Islamic constitution.28

Betrayal and Conspiracy: Developmental Histories and Myths of Pakistani Strategic Culture

It is to the next section of this article that the partition of British India into the dominions of Pakistan and India shall now be considered and why this process provoked strong sentiments of distrust and betrayal in many Pakistan Army officers and the importance of this in the foundation of a Pakistani strategic culture. Officers who would constitute the new Pakistan Army did not trust Viceroy Louis Mountbatten and believed him to be biased against Pakistan in considering the partition, while Vicereine Edwina Mountbatten’s allegedly improper relationship with Jawaharlal Nehru were believed by Pakistanis to be another example of the improper Hindu influence on the viceroy.29

Similarly, the departure (before his due date) of the supreme commander of the British Indian Army Claude Auchinleck at Mountbatten’s urging, because of allegations of Auchinleck’s bias toward Pakistan, infuriated the Pakistanis,who saw themselves as outmaneuvered by the Indians due to their special relationship with Mountbatten.30 Mountbatten had also taken advantage of Auchinleck’s offer to resign in response to his alleged bias toward Pakistan.31 Pakistanis believed the early departure of Auchinleck left Pakistan at the mercy of India, who held most of the government and military stores, and believed India would not honor the agreed division. This belief was shared by Auchinleck, who thought Indian intentions were

too strongly imbued with the implacable determination to remove anything which is likely to prevent their gaining their own ends, which are to prevent Pakistan receiving her just share, or indeed anything. If we are removed there is no hope at all of any just division of assets in the shape of movable assets belonging to the former Indian Army.32

Auchinleck’s beliefs were supported by those officers who formed the new Pakistan Army, who were outraged by Mountbatten’s actions, as well as the violence during the process of partition. The process of partition poisoned what trust had existed between Hindu, Sikh, and Muslim communities in the Punjab. Pakistani, Indian, and British officers who had served together in the British Indian Army were witness to a carnage and brutality that fundamentally polarized communal perceptions between Muslim, Sikh, and Hindu communities. The brutalities were not one-sided, but many caught in the maelstrom of violence could see it only as evidence of hate perpetrated on their coreligionists. The personal and communal experiences of violence experienced by Muslim officers invoked an epiphany in many officers, which separated them from their past perspectives on relations with other communities during service with Sikh and Hindu officers. The shared experiences of these officers who were mainly Punjabi and Pashtun officers amplified their sense of Muslim identity and the threat posed by the Hindus and Sikhs and fulfilled the Muslim League’s prepartition fears of being dominated by a Hindu India.33

Major Mohammad Musa, a senior staff officer in Lahore between September and December 1947 and later commander in chief of the army, recalled his trauma of having witnessed a train full of slaughtered Muslim refugees and the influence this had on his perceptions of the Indian state and its political objectives.34 Similarly, Mohammad Zia ul-Haq, the later commander in chief and dictator, had related how the vision of his exhausted mother crossing the border into Pakistan carrying their worldly possessions produced an indelible impact on him.35

It is important to note that there had originally been a concerted effort to prevent the division of the British Indian Army. Many British believed a single army could have served both dominions for a time. It is this topic that the article now examines.

Conspiracy Theories and a Muslim Pakistan Army

The uncompleted nature of the division was due in part to this resistance to divide the army by the British and some Indian officers, with some British officers believing that the majority of Indian officers were even against independence.36 The division was resisted by Mountbatten, the last viceroy; Auchinleck, the supreme commander in chief; as well as senior officers of the new Indian Army.37 Lord Hastings Lionel Ismay, who had served in the British Indian Army and who was Mountbatten’s chief of staff, stated,

The problem which caused many of us the greatest grief was the decision to divide the Indian Army on communal lines be- fore partition took place . . . I did my utmost to persuade Mr. Jinnah to reconsider his decision . . . but Jinnah was adamant. He said that he would refuse to take over power on 15 August unless he had an army of appropriate strength and predominantly Muslim composition under his control.38

Auchinleck had opposed an early plan for the division of the forces in April 1947 by the first prime minister of Pakistan, Liaquat Ali Khan. The Pakistanis resented this and saw the reluctance as contributing to the failure of Pakistan receiving its share of military stores.39 Other Pakistanis saw the reluctance in more sinister terms with the save the united army campaign as a Hindu plot to sabotage the partition of India and deny the creation of Pakistan.40 The “Hindu plot” to deny the formation of the Pakistan Army became an established army myth held by the officers of the new Pakistan Army.

To sabotage partition, a campaign to save the Army was stepped up. Senior Hindu Officers went around persuading the Muslim personnel not to accept the division . . . at the back of their minds was the hope that without an Army of its own Pakistan would not be able to last very long.41

Other Pakistanis saw the hand of British strategic expediency with Britain trying to maintain a united army in terms of its strategic value to the Commonwealth.42 The issue had actually been the subject of British cabinet considerations regarding potential contingency planning against the Soviets.43 The fact that Britain did want to retain influence in the future dominion’s defense relationships was evident in that the May 1947 India Burma committee recommended that Britain should insist that Pakistan and India should not lease bases to any power outside the Commonwealth other than in pursuance of regional defense approved by the UN.44 Chaudhri Muhammad Ali, a member of the armed forces reconstitution steering committee chaired by Auchinleck, claimed that the attachment to the undivided army by British officers and many Indian officers was so great that many could not emotionally reconcile themselves to the army’s division.45 The profound impact of even using the term “division” was felt to be psychologically harmful by Auchinleck.46 Officers of the new Pakistan Army were distinctly against retaining a single army and stated their preferences to the British in terms of the religious chasm between Muslim and Hindu. The commanding officer of the 7th Battalion of the 10th Baluch Regiment stated to General Sir Frank Walter Messervy, the first commander in chief of the Pakistan Army, the Islamic nature of the proposed new army, which was in contradiction with the Indian Army:

Sir, my grandfather, my father and I have fought for your empire. I have no wish that my sons and grandsons fight for the Hindus.47

Later commander and dictator of Pakistan Ayub Khan wrote that he was approached by General Kodandera Cariappa, the first commander in chief of the Indian Army, in a bid to seek Ayub’s support in not dividing the army.48 Muslim officers, though, were increasingly influenced by the impact of the communal violence during partition. Furthermore, there were instances of the army’s unity unraveling with episodes involving Muslim units engaging in fatal skirmishes with Sikh and Hindu units.49 Other instances such as the Indian Navy mutiny as well as communal troubles on board troopships returning with Muslim and Hindu troops from overseas were also reported.50 The British also began to suffer casualties involved in the escort of refugees between India and Pakistan.51

The rapidity of partition and the division of the army was confusing to the few senior officers who would constitute the Pakistan Army. Brigadier Akbar Khan, in his response to an armed forces committee question, responded,

I don’t even know whether there will be one or two Indias. It will depend on whether there will be internal troubles or war.52

This confusion was something familiar to junior Muslim officers, who had no idea as late as March and April 1947 that the army would be divided.53

The resistance to divide the army was perhaps amplified by the fact that several senior British officials were critical of Jinnah, with Ismay sharing confidential notes of his discussions with Jinnah to Nehru.54 Jinnah was likewise critical of some British officials. Jinnah informed Ismay that a number of British officials were dangerously susceptible to providing concessions to the Indians due to their inability to understand the wiles of the Hindu mind and the Hindu determination to prevent the creation of Pakistan.55 Jinnah’s distinctly religious rhetoric in describing the Hindu mind was incongruent with a number of his notable addresses on the nature of Pakistan’s inclusiveness.

Despite the resistance by the British, the army was divided. Pakistan became a nation on 14 August 1947, and the army it inherited was constituted from the Muslim elements of the former regiments of the British Indian Army. For a very short time before the violence of partition escalated, in keeping with Jinnah’s vision, there were Hindu officers who had opted to serve in the Pakistan Army.56

The Pakistani officers forming the new army, though nearly all Muslim and nearly all originating from the Punjab or the NWFP, came from a complex sociological mélange of tribes, clans, and religions. Most officers came from families with traditions of military service to the British. The first two commanders in chief of the Pakistan Army were British, and upon independence in 1947 there were 120 British officers serving in the Pakistan Army in senior positions.57 Most of the Muslim officers who constituted the army were junior in rank and experience. The loss of officers during partition due to combat in Kashmir and accidents meant that many were rapidly promoted to fill gaps in the new army.58 Ayub Khan, for instance, advanced within six years from colonel to be the army’s first commander in chief. This was a familiar experience to many of the new Pakistani Army officers with, for example, an artillery officer commissioned in 1946 receiving an accelerated promotion to major due to the shortage of qualified officers.59

While the division of army personnel was confused, the division of the military weapons, stores, and assets of the British Indian Army between the two new dominion’s armies was fraught with ill will and subterfuge. The division of assets involved countless claims and counter claims between Pakistani and Indian sources as to the dastardly acts performed by each other. Complaints alleged nearly every conceivable crime and act from plain theft of stores to fraud and the alleged sabotage of equipment. In keeping with the Hindu myth, many Pakistani officers believed the Indians premeditatively starved them of supplies to prevent the establishment of the Pakistan Army.60

Brigadier Mohammad Ansari, commissioned in 1943, oversaw the emergence of the Pakistan Army Ordnance Corps at partition and claimed that India had disarmed repatriated troops bound for Pakistan.61 Ansari’s perspective as an officer who formed the first generation of the new Pakistan Army is consistent with others of this generation who believed in the hostile disposition of an irredentist India. These beliefs were linked ideologically to a vengeful Hindu India engaged on a deliberate initiative to ruin Muslim Pakistan that have incrementally become an important element of a Pakistani strategic culture since partition.

Despite Indian complaints of their own problems, the Pakistanis viewed their problems as continuing elements of a sinister and premeditated Indian attempt to extinguish the Pakistan Army at birth.62 The sabotage of equipment left behind in Pakistan—such as the rendering of the Poona Horse’s few tanks in operation by fouling their fuel tanks—were seen as warlike in their intention, especially so when it had prevented these tanks’ subsequent deployment in the 1948 border hostilities.63

The Pakistanis, of course, were not ready to concede the arguably inescapable reality that during the Second World War army depots had been situated near the main supply routes for the war in Southeast Asia. The location of most of these depots had absolutely nothing to do with Indian intentions at partition and everything to do with the pragmatism of such centers being close to operational theaters during the war.

Pakistani claims were countered by Indian arguments that the division of assets was impossible given the immensity of trying to sort out records from 1857 onward within the limited time frame thrust on them by the British decision.64 Pakistani officers argued they were not assisted by Indian or British officers in their tasks and had to leave New Delhi prematurely without achieving their tasks due to the mounting violence against Muslims.65 A Pakistani officer noted they had to cobble together units made up of a patchwork of individuals, platoons, and oddly constituted companies that had trickled into Pakistan.66 Though officers of the British Indian Army generation still perceived India as an existential threat, it is apparent this early generation still held many of these former colleagues in warm regard, a phenomenon the officers commissioned after 1947 did not experience and that served to further polarize their view of India.67 A number also had relatives in Indian military service as well as matrimonial agreements with communal connections in India.68

Many of the first generation of officers at the new officer training school at the Pakistan Military Academy (PMA) were convinced of the hostile intentions of India. This newer generation of officers derived these beliefs from the tribulations experienced during partition and were convinced India did not want Pakistan to exist.69 Significantly, this new generation of officers were being nurtured on the same notions of their inherent martial race superiority by those remaining British officers as their ancestors had. Their martial race identities were being conflated with the Muslim nature of the new state and contributed to a martial race Muslim exceptionalism.

The dominant narrative remained outrage at India’s alleged perfidy in not honoring the division of the force’s agreement. Many of the new Pakistani officers may have been aware that their British commander had also bitterly complained about India’s alleged failure to honor agreements. General Sir Douglas D. Gracey, the army’s second commander in chief, had complained directly to the Commonwealth Relations Office that India was “continuing to do its best to sabotage Pakistan” with this complaint possibly not lost on the Pakistani officers who worked closely with him, such as his aide-de-camp Lieutenant Wajahat Hussain.70 Other British officers in the Pakistan Army also noted their misgivings, with one believing the Indians maliciously turned trains around east of Lahore back to their points of departure 71

The British, Martial Race, and Its Influence on Pakistani Strategic Culture

This section now examines how General Sir Douglas Gracey and some other British Officers in the Pakistan Army had pronounced preferences for martial race units obtained during their service with the British Indian Army before, during, and after World War II. These preferences were significant in their influence on the Punjabi and the Pashtun bulk of the newly formed officer corps. Class composition limiting army recruitment to Punjabis and Pashtuns, while identified as not appropriate in a new national army, was still evident in the newly formed Pakistan Army. The foreword written by General Gracey in 1950 in the centenary publication of the Punjab Field Force Regiment noted recruitment had of necessity changed because Sikhs, Dogras, and Gurkhas could no longer be recruited:

Since partition the class composition has been changed to 50% each of Punjabi Mussulmans and Pathans and the recruitment of only special areas and tribes has been done away with.72

The changes, though, only concerned a matter of choice between classes of Punjabi and Pashtuns. There is, for instance, no mention of Pakistan’s majority population of Bengalis or that of the other Pakistani ethnic populations.

The matter of martial race and “class” composition was an issue of some importance to British officers in deciding whether to stay on in Pakistan. It is perhaps not difficult to believe that these British officers so immersed in favorable views of martial race would not continue to utter and promote these beliefs to those same martial race officers now being groomed to assume leadership of the army. As late as 1945, Colonel Christopher Bromhead Birdwood argued for the immutable logic of martial race, despite protests of its racially discriminatory presumptions.73 The Punjabi and Pashtun officers arguably provided a receptive audience to these senior British officers so enamored with martial race. The positive views of these British officers would have probably gone some way in confirming these beliefs of exceptionalism in the older generation of Pakistani officers, as well as indoctrinating the newer generations being trained at the PMA. In so doing, these British Indian officers ensured the continuation of these beliefs in the army:

The thought of commanding a regiment composed of Punjabi Mussulmans and one to be regarded as the equivalent of an R.H.A [Royal Horse Artillery] regiment in the British Service was a choice I could not resist.74

That British officers continued to hold such beliefs even after the expansion of recruitment to nonmartial groups during World War II is not surprising, given the preeminent place of martial race in the British Indian Army from the late nineteenth century onward. This identification by British officers with the servicemembers of the Pakistan Army was not unusual and was an element of the two-way process of glorification and identification with the martial race unit that had occurred in the British Indian Army.75

The British officers in Pakistan from 1947 to 1951 continued to believe in the veracity of martial race and transmitted this to their largely Punjabi and Pashtun audience in the now independent Pakistan Army. The Punjabi and Pashtun officers who formed the bulk of the Pakistan Army were indoctrinated by the British to define themselves by religion and ethnicity and believed this to be accepted wisdom. They took up wholeheartedly their territorial and ideological mantle as Islamic Ghazis and soldier saviors of the newly created Muslim homeland from the Hindu enemy. Though Pakistan had never been a nation in the past and had inauthentic and tenuous links to the Mughal Empire, the influence of British martial race rhetoric glorified and confirmed their perceptions of identity as glorious Islamic warriors. The accession of Kashmir to India invoked the call of an Islam in danger and the official and unofficial involvement of the army. Elements of the army supported and were involved with eclectic bands of mujahideen and tribal Lashkars bent on taking Kashmir from India.

Kashmir: The Bedrock of Pakistani Strategic Culture

Kashmir provided the grounds for further mythmaking in the tale of a battle in which the former British Indian officers, newly commissioned officers, and officers in training became thoroughly immersed in a war in which “Islam in danger” was the rallying cry and cast all into a conflict overlaid with religious themes.

The hardships of partition had amplified the divide between Muslim and Hindu due to the entire premise of the two-nation theory for which Pakistan had been created. The signing of the instrument of accession by the maharajah of Kashmir confirmed the new Pakistani officers’ views of the abject treachery on India’s part in securing the Muslim majority state for the Indian Union. The accession was bitterly argued by the Pakistanis who denounced India’s perfidy and Mountbatten and his Hindu clique’s bias. All these factors contributed to a narrative of Hindu oppression, perfidy, and lost opportunities in which Pakistan should have acquired Kashmir. It also served as a useful motif for defining and consolidating the army’s identity with the treachery of the Hindu enemy “other” defining the Muslim nature of the Pakistan Army.

Islam in Danger and the Vengeful, Irredentist India Narrative Impact on the Foundations of Pakistani Strategic Culture

What this section of the article will briefly make evident is that irrespective of the ultimate argument concerning the accession of Kashmir to India is the enduring influence that the accession had on this first and succeeding generations of Pakistani officers. The manner that India obtained Kashmir as well as the alleged subjection of a Muslim majority area to Hindu India from this point became a core element of Pakistan Army strategic culture in which Islam was pitted against Hinduism. An enduring narrative by army officers maintains that a vengeful Hindu India—thwarted by its designs of a unified subcontinent by the creation of Pakistan—undertook to dismantle, diminish, and delegitimize Pakistan’s existence until it was absorbed back into the fold of India. The Kashmir issue was from that time until today a point of friction as well as a tinderbox to war in 1948 and 1965 as well as undeclared war and insurgencies by Pakistani proxies from Lashkar-e-Taiba to the use of disguised Pakistani infantry in the Kargil crisis as well as other hostile and shallowly deniable attacks against Indian interests.

Significantly, in religious terms, Pakistani Army officers understood the situation of the original Kashmir conflict explicitly as one of Hindu Indians being a danger to Islam.76 “Islam in danger” in Kashmir became a rallying cry acquired by the Pakistan Army. This notion was familiar in its tribal context to many of the officers from Pashtun backgrounds. The powerful unifying aspects of the jihad on this basis drew from a tradition of Southwest Asian Muslim resistance where “religion was used to define the enemy.”77

Many Pakistani officers of this generation note how they participated, or knew of others who had participated, with tribal Lashkars in the invasion of Kashmir. Officers justified their break from professional training and involvement in the jihad specifically in terms of “Islam in danger.” The response to “Islam in danger” entailed a religious obligation of jihad against a Hindu aggressor believed to be guilty of atrocities on the Muslim population.78 Tribal jirgas of the Afridi and Mohmand’s had initially and unsuccessfully sought the permission of Sir George Cunningham, the governor of the NWFP in late October 1947, to go to the assistance of their brethren in Kashmir.79

Their leaders, both religious and secular, were unanimous in their belief that it was their duty to go to the help of their brethren in the Punjab and Kashmir Jihad or holy war was being discussed in every hujra and Jirga.80

The first generation of officers being trained at the PMA, which was not officially opened until November 1948, were also alert to the call of “Islam in danger” and were eager to participate in the jihad in Kashmir.81 Some went to Kashmir without the knowledge of the PMA staff and led tribal Lashkars. 82 One notes that he and other officers volunteered when it became apparent that the commitment of regular forces would not cause the Indians to spread the conflict into the Punjab.83 Others went because they recognized that the jihad of the tribes would not succeed without their skilled assistance.

Soon after the tribesmen invaded Kashmir it became imperative to have some control over them to defend Azad Kashmir effectively. To that end Pakistani officer volunteers were inducted immediately to take care of these Lashkar’s. This number kept increasing.84

Islamic martial myths were important to the army officers who joined this jihad and heroic tales of Islamic military prowess are popular reference points in the military history taught to Pakistani Army officers. Religious and martial imagery are evident in accounts of the fighting in Kashmir during 1947–48. Akbar Khan’s account of leading tribal Lashkars under the nom de guerre General Tariq, the famous Moorish invader, were evidence of the importance of connecting such heroic Islamic figures to the exploits of the new Muslim officers of the Pakistan Army. Hafeez Jalandhri, who was to become the national poet of Pakistan during this period, was also wounded in Kashmir and would write the heroic lyrics to the Pakistan National Anthem. Religious and martial symbolisms in this first generation of Pakistani officers are imbued with the myth of Muslim exceptionalism as Ghazis defending and overcoming the enemies of the faith.

The spectacle before us was like a page out of old history. Memory flashed back many centuries. This is what it might have been like when our forefathers had poured in through the mountain passes of the Frontier . . . men of all ages, grey beards to teenagers good to look at and awe inspiring . . . these men had come to fight, in their blood ran the memory of centuries of invasions and adventure . . . above the rumble and din could be heard a chorus of war songs . . . ahead lay glory.85

The significance of Akbar’s account as well as the less florid accounts of others is important in their emphasis on the joint tribulations and camaraderie experienced by these fellow Muslim officers in the new army of a new country with no historical antecedents.

It was a formative experience at the very beginning of many officers’ army careers, and it encouraged many young Pakistani men such as Hakeem Qureshi, who had assisted the Mujahideen, to join the army and continue the fight against India.86 Veteran officers such as Akbar and officer cadets alike engaged in a jihad against the perceived threat of a Hindu India bent on denying Pakistan its birthright. The excitement apparent at the beginning of many conflicts played a part, but equally the experiences of the jihad in Kashmir made lasting impressions on these officers’ individual and group identity. This was especially so for those officer cadets and newly commissioned officers whose first experience of combat would be against India in a conflict infused with religious overtones. The jihad in Kashmir tied with the communal and religious violence that had occurred during partition became infused with powerful elements of religion, historical experience, and myth that contributed to the creation of an identity for the Pakistan Army and the foundation of the army’s strategic culture.

Defending Pakistan for the army became significantly synonymous not with any concept of a constitution or political ideology but explicitly in terms of defending Islam, and the injustice at the loss of Kashmir tempered by the heroism of the jihadi tribes and their Pakistan Army members was established as the key element of the fledgling army’s strategic culture.

The cries of the danger presented to Islam called on the new army officers to respond in a manner inimical to their previously inherited traditions and training received in the British Indian Army, with the psychological impact of combat tied with the religious aspects of combat profoundly influencing this generation of officers.87 The fears of the loss of Kashmir to India galvanized officers such as the Sandhurst-trained Akbar as well as others to join and lead tribal Lashkars in an unconventional, religiously inspired war against India.

There was also a strategic territorial imperative in wishing to obtain Kashmir by any means necessary, but it was the religious call of Islam in danger that motivated many Muslims. The call to jihad saw serving Pakistani officers act jointly with disgraced Indian National Army officers, deserters, entire units of princely state forces—such as the 300 soldiers of the Wali of Swat’s Army—and even adventurers sympathetic to Pakistan’s cause, such as the case of a former American servicemember who allegedly led a Lashkar of 8,000 tribals.88

A British officer was also arrested in Rawalpindi and suspected by the British of leading Pakistani troops in Kashmir.89 The arrested officer had threatened to reveal the alleged involvement of other British officers in Kashmir, including the bombardment of Indian positions on behalf of Azad Kashmir forces by a British officer.90

The 1971 War: Strategic Shock, Moral Turpitude, and Islam

As Pakistan approached war with India in 1971, the Americans were surprised at the arrogance and naiveté of the Pakistani Army generals’ belief in their martial race identity and Islamic exceptionalism to rescue them from their developing debacle.

When I asked as tactfully as I could about the Indian advantage in numbers and equipment, Yahya [Khan] and his colleagues answered with bravado about the historic superiority of Moslem fighters.91

The impact of the loss of the war was a strategic shock for the army that caused it to question both its leadership and culture. A strategic shock or a strategic surprise may be explained as

those . . . events that, if they occur, would make a big difference to the future, force decision makers to challenge their own assumptions of how the world works, and require hard choices today.92

In particular, the loss ignited a belief that attributed blame to a great degree on the moral turpitude of the senior officer corps. These officers came to be thought of as irreligious and slavish followers of the inherited culture from the British Indian Army. In rowdy scenes after the war, younger officers distinctly saw the irreligiosity of their officers as a major factor in the humiliating loss to India.

Conclusion

This article examined the formative years of the Pakistan Army from its inception in 1947. The article explored and analyzed the impact of the partition of British India on the newly independent dominion of Pakistan’s army officers and argued the significance of this in the establishment of a Pakistani strategic culture that reflected on a history of treachery, a fear of an irredentist Hindu India hostile to a Muslim Pakistan, and a belief that the identity for the new state should be wedded to its formation as a homeland for Muslims. This article illustrated how the searing impact of partition created these beliefs in the new Pakistani army officers. Many of these who had served with Sikhs and Hindus experienced epiphany-like situations arising out of the horrors of partition that reinvigorated their sense of Islamic identity.

The article also argued those British officers who undertook service in the Pakistan Army, including their commanders, were thoroughly imbued with beliefs in martial race. The article asserted that these senior and influential officers’ views on martial race would have received a receptive audience in an officer corps consisting of Punjabi and Pashtun officers who had been generationally feted as superior soldiers. The impact of partition, together with the perpetuation of beliefs in martial race, were then joined by the impact of the First Kashmir War (1947–48). The mythology of the potential danger that a Hindu India presented to Islam was noted in the article as a cry to the faithful to join the battle against the Indians in Kashmir. The convergence of these three elements established the foundations of strategic culture derived from shared hardships, disasters, and the unitary call to Islam. The strategic culture founded during the tumultuous period of independence in 1947 has since added new dimensions and nuances to the contours in its regional and geostrategic relationships. This strategic culture is agile and attuned to political realism to ensure the survival of the Pakistani state or at least how the military perceives its interests and survival. As illustrated above, the foundational contours of the strategic culture of Pakistan endure with absolutely no indication of any shift in its outlook in the near future, especially in its perception of India, which remains essentially as belligerent as it did 74 years ago when both nations became independent. Looking back from 1947 to the current day, these foundational influences are still apparent with the Indian threat remaining centric to Pakistan’s strategic culture and security interests, whether it was the series of wars from 1948 to 1971 and later incidents such as Kargil or the enduring impact of the Global War on Terrorism and continuing claims that India is attempting to destabilize Pakistan, either through their alleged support of militants such as the Balochistan Liberation Army or their historic support for an Afghanistan hostile to Pakistani interests.

Endnotes

- As quoted in the foreword of Brig S. K. Malik, The Quranic Concept of War (New Delhi, India: Himalayan Books, [1976] 1986). Emphasis in original.

- A strategic shock may also be explained as an event that has an important impact on the country and/or stretches conventional wisdom with fundamental implications, or as Nathan Freier explains more informally, “a game changing event that changes the nature of the game.” Nathan Freier, Known Unknowns: Unconventional “Strategic Shocks” in Defense Strategy Development (Carlisle, PA: Strategic Studies Institute, 2008), 4–5.

- “The belief that Islam is under threat politically and/or religiously is shared by different Islamic movements and scholars across various Muslim countries.” Joas Wagemakers, “Framing the ‘Threat to Islam: Al-Wala’Wa Al-Bara’ in Salafi Discourse,” Arab Studies Quarterly 30, no. 4 (Fall 2008): 4. Some scholars have placed the concept of “Islam in danger” as central to the formation of Pakistan. Sayeed argued in 1963 that even Jinnah with all his brilliance could not have achieved Pakistan without the two cries, “Islam in danger!” and “Pakistan an Islamic State!” Khalid Bin Sayeed, “Islam and National Integration in Pakistan,” in South Asian Politics and Religion, ed. Donald Eugene Smith (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1966), 412, https://doi.org /10.1515/9781400879083.

- Gregory F. Giles, Continuity and Change in Israel’s Strategic Culture (Fort Belvoir, VA: Defense Threat Reduction Agency, 2002); Jennifer Knepper, “Nuclear Weapons and Iranian Strategic Culture,” Comparative Strategy 27, no. 5 (2008): https:// doi.org/10.1080/01495930802430080; and Elizabeth Kier, “Culture and Military Doctrine: France between the Wars,” International Security 19, no. 4 (Spring 1995): https://doi.org/10.2307/2539120.

- Lawrence Sondhaus, Strategic Culture and Ways of War (London: Routledge, 2006), 3.

- Sondhaus, Strategic Culture, 1.

- Jeffrey S. Lantis and Darryle Howlett, “Strategic Culture,” in Strategy in the Contemporary World, ed. John Bayliss, James J. Wirtz, and Colin S. Gray, 4th ed. (Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 2013), 76–95.

- Sondhaus, Strategic Culture and Ways of War, 5.

- Hasan Askari Rizvi, “Pakistan’s Strategic Culture,” in South Asia in 2020: Future Strategic Balances and Alliances, ed. Michael R. Chambers (Carlisle, PA: Strategic Studies Institute, 2002), 305–29; Feroz Hassan Khan, “Comparative Strategic Culture: The Case of Pakistan,” Strategic Insights 4, no. 10 (October 2005); and Peter R. Lavoy, Pakistan’s Strategic Culture (Fort Belvoir, VA: Defense Threat Reduction Agency 2006).

- Rizvi, “Pakistan’s Strategic Culture,” 307.

- Sondhaus, Strategic Culture and Ways of War, 78, 86–88.

- According to Anthony Smith, emeritus professor of nationalism and ethnicity at the London School of Economics, ethno-symbolism and nationalism theory emphasizes the importance of conflict in creating myths of battle and heroism that later generations may emulate, a theme that is prevalent in Pakistan. Anthony D. Smith, EthnoSymbolism and Nationalism (London: Routledge, 2009), 47. The term myth is also usefully considered from the sense described by Marwick of a “myth” being a version of the past containing an element of truth in that it distorts what actually happened in support of a vested interest. See Arthur Marwick, The New Nature of History: Knowledge, Evidence, Language (London: Palgrave MacMillan, 2001), 292.

- Population estimates derived from estimates of 1951. Joseph E Schwartzberg, ed., A Historical Atlas of South Asia (New York: Oxford University Press, 1992), 77.

- Schwartzberg, A Historical Atlas of South Asia, 77.

- One in 5 of East Pakistan’s population was non-Muslim compared to 1 in 30 of West Pakistan. Ian Talbot, Pakistan: A New History (London: Hurst, 2012), 16.

- MajGen S. Shahid Hamid, Early Years of Pakistan: Including the Period from August 1947 to 1949 (Lahore, Pakistan: Ferozsons, 1993), 26, 41–53.

- Pervaiz Iqbal Cheema, Pakistan’s Defence Policy, 1947–58 (Lahore, Pakistan: Sang-eMeel Publications, 1998), 67, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-349-20942-2.

- Aparna Pande, Explaining Pakistan’s Foreign Policy: Escaping India (London: Routledge, 2011), 47.

- Hamid, Early Years of Pakistan, 37.

- For literature on the violence of partition, see Partition: Surgery Without Anesthesia (Islamabad, Pakistan: Society for the Protection of the Rights of the Child, 1998); Yasmin Khan, The Great Partition: The Making of India and Pakistan (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2007); Gyanendra Pandey, Remembering Partition: Violence, Nationalism and History in India (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2001), https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511613173; Ian Talbot and Gurharpal Singh, The Partition of India (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2009); and Stanley Wolpert, Shameful Flight: The Last Years of the British Empire in India (Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 2006).

- Hamid, Early Years of Pakistan, 41–53.

- MajGen S. K. Sinha, Operation Rescue: Military Operations in Jammu & Kashmir, 1947–49 (New Delhi, India: Vision Books, [1955] 1977), 21.

- Verinder Grover and Ranjana Arora, eds., Pakistan: 50 Years of Independence (New Delhi, India: Deep & Deep Publications, 1997), 23.

- Anas Malik, Political Survival in Pakistan: Beyond Ideology (London: Taylor & Francis, 2010), 42.

- Aaron T. Wolf and Joshua T. Newton, Case Study of Transboundary Dispute Resolution: The Indus Water Treaty (Corvallis: Institute for Water and Watersheds, Oregon State University, 2013).

- There was significant opposition to the idea of Pakistan among religious groups with figures in the Deoband school believing that Jinnah and Liaquat Ali Khan would be incapable of building an Islamic state in Pakistan. See Ziya-ul-Hasan Faruqi, The Deoband School and the Demand for Pakistan (Calcutta, India: Navana, 1963), 118–21.

- Mohamed Nawab bin Mohammed Osman, “The Ulama in Pakistani Politics,” South Asia—Journal of South Asian Studies 32, no. 2 (2009): 232; and Safir Akhtar, “Pakistan Since Independence: The Political Role of the Ulama” (PhD diss., University of York, May 1989), 236.

- Safir, “Pakistan Since Independence,” 234.

- The poor view of Mountbatten by Pakistani Army writers is prolific, including an almost de rigueur reference in regimental histories; for example, in MajGen Rafiuddin Ahmed, History of the Baloch Regiment, 1939–1956 (East Sussex, UK: Naval & Military Press, 2005), 189, 197; and Col M. Y. Effendi, Punjab Cavalry: Evolution, Role, Organisation and Tactical Doctrine 11 Cavalry (Frontier Force), 1849–1971 (Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 2007), 147.

- General the Lord Ismay Papers, 3/7/67/38, Letter from Viceroy Mountbatten to Field Marshal Sir Claude Auchinleck, 26 September 1947 at Government House to Field Marshal Sir Claude Auchinleck, Liddell Hart Centre for Military Archives (LHCMA).

- General the Lord Ismay Papers, 3/7/67/38, 4.

- John Connell, Auchinleck: A Critical Biography of Field-Marshal Sir Claude Auchinleck (London: Cassell, 1959), 920–21; and Auchinleck’s private secretary MajGen Shahid Hamid, Disastrous Twilight: A Personal Record of the Partition of India (London: Leo Cooper, 1986), 260–61. Auchinleck’s papers in the John Rylands Library at the University of Manchester, document 1262, 28 September 1947, refer to this quote.

- Wajahat Hussain’s Indian commander attempted to persuade him to remain in India, but Hussain, who had served on the Punjab Boundary Force, was convinced by witnessing the carnage brought on Muslims in the East Punjab to opt for Pakistan, in Hussain, “Remembering Our Warriors.” MajGen S. Wajahat Hussain, “Remembering Our Warriors—Interview of Major General (Retd) S. Wajahat Husain,” Defence Journal (August 2002).

- Gen Mohammad Musa, From Jawan to Genera (Karachi, Pakistan: East & West Publishing, 1984), 77.

- Quoted in Shahid Javed Burki, “Pakistan under Zia, 1977–1988,” Asian Survey 28, no. 10 (October 1988): 1084, https://doi.org/10.2307/2644708.

- Fraser claims this from his time with Indian officer cadets at an officer cadet training school after World War II. George MacDonald Fraser, Quartered Safe Out Here: A Recollection of the War in Burma (London: Harvill, 1992), 133.

- Ayub Khan notes that he was approached by Gen Kodandera M. Cariappa, the first commander in chief of the Indian Army, in a bid to seek Ayub’s support in not dividing the army, in Ayub Khan, Friends Not Masters: A Political Autobiography (London: Oxford University Press, 1967), 19. Chaudhri Muhammad Ali, a member of the armed forces reconstitution steering committee during partition also makes this claim; see Chaudhri Muhammad Ali, The Emergence of Pakistan (New York: Columbia University Press, 1967), 187.

- Lord Hastings Lionel Ismay, The Memoirs of the General the Lord Ismay (London: Heinemann, 1960), 425–28; and Alan Campbell-Johnson, Mission with Mountbatten (London: Robert Hale, 1951), 137. Johnson was Mountbatten’s aide-de-camp and wrote that Mountbatten thought the partition of the armed forces to be “the biggest crime and the biggest headache.”

- Ali, The Emergence of Pakistan, 187.

- MajGen Fazal Muqeem Khan, The Story of the Pakistan Army (Karachi, Pakistan: Oxford University Press, Karachi, 1961), 17–18.

- Brig S. Haider Abbas Rizvi, Veteran Campaigners: A History of the Punjab Regiment, 1759–1981 (Lahore, Pakistan: Wajidalis, 1984), 105.

- MajGen Shaukat Riza, The Pakistan Army, 1947–1949 (Lahore, Pakistan: Services Books Club, 1989), 118–19. See also Brig D. H. Cole, Imperial Military Geography: The Geographical Background of the Defence Problems of the British Commonwealth (London: Sifton Praed, 1953), 159–82. Cole writes of the importance of India as a potential base for Britain and the particular problems of Pakistan, 172–76.

- National Archives of the United Kingdom—Public Record Office (PRO) CAB 128/7—Confidential Annex to reference CM (46) 55, India Constitutional Problem, 23.

- Anita Inder Singh, “Imperial Defence and the Transfer of Power in India, 1946–1947,” International History Review 4, no. 4. (November 1982): 568–88; and Riza, The Pakistan Army, 1947–1949, 125.

- Ali, The Emergence of Pakistan, 186–87.

- Field Marshal Auchinleck to chiefs of staff and British Cabinet, in Connell, Auchinleck, 889.

- Ahmed, History of the Baloch Regiment, 187–88.

- Khan, Friends Not Masters, 19. The future defense minister and prime minister of Pakistan, Chaudhri Muhammad Ali, also makes this claim in his book, Ali, The Emergence of Pakistan,187.

- An officer of the 2d Battalion of the Black Watch witnessed a fatal skirmish between the Muslim troops of the 3d Battalion of the 8th Punjab Regiment and the Sikhs and Hindus of the 19th Lancers on 7 September 1947, in Roy Humphries, To Stop a Rising Sun: Reminiscences of Wartime in India and Burma (Gloucestershire, UK: Sutton Publishing, 1996), 203.

- Boyle—Reports and Messages re: tensions between Muslim and Hindu troops on board H.M. Troopship “Empire Pride,” Suez-Bombay, October 1947, LHCMA. Boyle reports via “Marconigrams” of his and fellow British officers’ (Maj Walker and Maj Mitchell) belief in imminent violence on board the vessel between the Muslim majority and Hindu minority if the vessel did not dock at Karachi before Bombay.

- The commander of the 33 Field Squadron Engineers reported the death of two British officers escorting Muslim refugees in Amritsar, India, in Humphries, To Stop a Rising Sun, 201–2.

- National Army Museum (NAM.1982-04-797-1), Brig Akbar Khan’s response as a wit- Briskey 151 Strategic Culture ness to the Armed Forces Naturalisation Committee (AFNC) (from minutes of AFNC at 14th meeting on Wednesday, 9 April 1947).

- MajGen Tajammal Hussain Malik, The Story of My Struggle (Lahore, Pakistan: Jang Publishers, 1991), 7.

- Ismay and Montgomery were critical of Jinnah and even Montgomery with his contemporary lack of familiarity with India pronounced that Jinnah had a deadly hatred of Hindus. Field Marshal Montgomery, The Memoirs of Field-Marshal the Viscount Montgomery of Alamein (London: Collins, 1958), 457; and Ismay blamed the troubles of partition on Jinnah, in British Library sound recording, C940/19 General Lord Ismay (1887–1965), interviewed by Henry Vincent Hodson, General the Lord Ismay Papers, 3/7/68/45, LHCMA.

- General the Lord Ismay Papers, 3/7/68/45.

- Jinnah’s inaugural address to the Constituent Assembly of Pakistan on 11 August 1947, in his capacity as its first president, in G. Allana, ed., Pakistan Movement: Historic Documents (Karachi, Pakistan: University of Karachi, 1967), 407–11; Hamid, Early Years of Pakistan, 37; and Ali, The Emergence of Pakistan, 186.

- Oriental and India Office Collections (OIOC) L/WS/1/1673—Appointments held by British Officers in Pakistan and List of Colonels and above—Pakistan Army.

- For instance, one serious loss was MajGen Iftikhar Khan, who some believed would be the first Pakistani army chief, who together with Brig Sher Khan, another experienced officer, was killed in an air crash on 13 November 1949.

- Brig Syed Shah Abul Qasim, Life Story of an Ex-Soldier (Karachi, Pakistan: Publicity Panel Publishers, 2003), 73.

- “Remembering Our Warriors.”

- Brig M. A. H. Ansari, Brig M. H. Hydri, and Col Mahboob Elahi, History of the Pakistan Army Ordnance Corps, 1947–1992 (Rawalpindi, Pakistan: Ordnance History Cell & Ferozsons, 1993), 89–90.

- Ansari, Hydri, and Elahi, History of the Pakistan Army Ordnance Corps, 1947–1992, 90.

- Brig Z. A. Khan, The Way It Was: Inside the Pakistan Army (Karachi, Pakistan: Ahbab Printers, 1998), 44.

- MajGen S. K. Sinha, Operation Rescue—Military Operations in Jammu & Kashmir, 1947–49 (New Delhi, India: Vision Books, [1955] 1977), 4. Sinha notes how he and a Pakistani officer ended up destroying several files due to their impossible task.

- Riza, The Pakistan Army, 1947–1949, 145–46.

- LtGen Faiz Ali Chisti, Betrayals of Another Kind: Islam, Democracy, and the Army in Pakistan (Lahore, Pakistan: Jang Publishers, 1996), 399.

- Rahman fondly recalled visiting India and meeting old British Indian Army colleagues such as Sam Manekshaw, an Indian Army officer. M. Attiqur Rahman, Back to the Pavilion (Karachi, Pakistan: Oxford University Press, 2005), 81.

- Qasim notes despite the tense atmosphere between Pakistan and India when he returned to Bangalore in 1953 to be married. Qasim, Life Story of an Ex-Soldier, 73; and LtGen Rahman’s brother was in the Indian government, in Rahman, Back to the Pavilion, 156.

- LtGen Jahan Dad Khan, Pakistan Leadership Challenges (Karachi, Pakistan: Oxford University Press, 1999), 8.

- From General Sir Douglas Gracey to General Sir Geoffrey Scoones, Commonwealth Relations Office, London, OIOC L/WS/1/1652 (7); and Hussain, “Remembering Our Warriors.”

- Devereux Papers ACC.197, “My tour with the Pakistan Army,” LHCMA, 1–2. Devereux commanded 3 SP Regiment Royal Pakistan Artillery.

- MajGen M. Hayaud Din, One Hundred Glorious Years: A History of the Punjab Frontier Force, 1849–1949 (Lahore, Pakistan: Civil and Military Gazette, 1950), 9.

- LtCol the Hon C. B. Birdwood, M.V.O., A Continent Experiments (London: Skeffington & Son, 1945), 112–13.

- LHCMA—Devereux Papers ACC.197, “My tour with the Pakistan Army,” 1. 152 The Foundations of Pakistan's Strategic Culture Journal of Advanced Military Studies

- MajGen Sher Ali Pataudi, The Story of Soldiering and Politics in India and Pakistan (Lahore, Pakistan: Syed Mobin Mahmud, 1988), 36.

- Khan, The Story of the Pakistan Army, 96. In regard to the notion of “Islam in danger,” several chapters discuss Pathan tribal custom on rebellion in the name of Islam, in Alan Warren, Waziristan, the Faqir of Ipi, and the Indian Army: The North West Frontier Revolt of 1936–37 (Karachi, Pakistan: Oxford University Press, 2000), chaps. 3–4.

- Warren, Waziristan, the Faqir of Ipi, and the Indian Army, 120.

- “The belief that Islam is under threat politically and/or religiously is shared by different Islamic movements and scholars across various Muslim countries.” Joas Wagemakers, “Framing the ‘Threat to Islam’: Al-Wala’Wa Al-Bara’ in Salafi Discourse,” Arab Studies Quarterly 30, no. 4 (Fall 2008): 4, https://doi.org/10.2307/41858559. Some scholars have placed the concept of “Islam in danger” as central to the formation of Pakistan. Sayeed argued in 1963 that even Jinnah with all his brilliance could not have achieved Pakistan without the two cries: “Islam in danger!” and “Pakistan an Islamic State!” Khalid Bin Sayeed, “Islam and National Integration in Pakistan,” in South Asian Politics and Religion, ed. Donald Eugene Smith (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1966), 412, https://doi.org/10.1515/9781400879083-019.

- OIOC IOR L/WS/1/747—British High Commission, Political Movements within the State, dated 28 November 1947.

- Khan, The Story of the Pakistan Army, 88.

- Khan, Pakistan Leadership Challenges, 11.

- Interview of MajGen Naseerullah Khan Babar, in “Remembering Our Warriors— Babar the Great,” Defence Journal 4, no. 9 (April 2001): 9.

- Brig S. Haider Abbas Rizvi, Veteran Campaigners: A History of the Punjab Regiment, 1759–1981 (Lahore, Pakistan: Wajidalis, 1984), 121.

- Hussain, “Remembering Our Warriors.”

- MajGen Akbar Khan, Raiders in Kashmir (Islamabad, Pakistan: National Book Foundation, 1970), 34–36, corroborated in part by Wajahat Hussain upon Akbar adopting the nom de guerre of the Muslim conqueror of Spain, “Tariq.” Hussain, “Remembering Our Warriors.”

- MajGen Hakeen Arshad Qureshi, The 1971 Indo-Pak War: A Soldier’s Narrative (Karachi, Pakistan: Oxford University Press, 2002), 246.

- On the existential transformation from experiencing combat, see Rune Henriksen, “Warriors in Combat—What Makes People Actively Fight in Combat?,” Journal of Strategic Studies 30 no. 2 (April 2007): 188–89, https://doi.org/10.1080 /01402390701248707.

- Khan, Raiders in Kashmir, 58, 72; Howard B. Schaffer, The Limits of Influence: America’s Role in Kashmir (Washington, DC: Brookings Institution Press, 2009), 21; and a photograph of Haight appearing in uniform wearing a ‘Pagri in Life Magazine 24, no. 7, 16 February 1948, 42.

- OIOC IOR L/PJ/7/13851—Capt Skellon I.E.M.E. Arrest at Rawalpindi and the Matter of Col Milne Pakistan Artillery.

- OIOC IOR L/PJ/7/13851—Capt Skellon.

- Henry Kissinger, The White House Years (Sydney: Hodder and Stoughton, 1979), 861.

- A strategic shock may also be explained as an event that has an important impact on the country and/or stretches conventional wisdom with fundamental implications, or as Freier explains more informally, “a game changing event that changes the nature of the game.” Freier, Known Unknowns, 4–5.