https://doi.org/10.21140/mcuj.20251602007

PRINTER FRIENDLY PDF

EPUB

AUDIOBOOK

Abstract: Proxy war has been a dynamic U.S. military strategy since the Cold War. In recent decades, however, artificial intelligence (AI) as a new manifestation of technology has played a significant role in these wars. The United States has been a pioneer in this field, making substantial investments, annually allocates multibillion-dollar budgets to advance robotic and automated weapons to win future wars. Artificial intelligence proxy wars can manage the competition between international actors as a mediating factor without wasting human resources. The main question of this article is as follows: What is the role of artificial intelligence in U.S. military strategy, and how much can this new technology help win proxy wars? The findings indicate that the United States, by applying artificial intelligence technology to its military equipment with remote control capabilities, robots, and automated guided weapons, has reduced human and financial costs while increasing the probability of triumph on the battlefield. However, the obtained data, according to moral and humanitarian criteria, suggest a high rate of civilian casualties in such military conflicts.

Keywords: artificial intelligence, AI, proxy war, military strategy, drones, automated weapons

Many analysts view the world order and American hegemony as influenced by nuclear arms races, economic shifts, and various treaties and alliances. The United States has consistently leveraged these factors to maintain its position. According to Samuel Huntington’s predictions, the current international order is transitioning toward a unipolar-multipolar dynamic, where emerging technological issues in the economy and military could become key challenges.1 The rise of AI in these areas, along with its critical role in optimizing resources and preserving hegemony, has made it a strategic asset for U.S. rivals like China in pursuing global competitiveness.

World leaders, including Barack H. Obama, Donald J. Trump, Xi Jinping, and Vladimir Putin have made critical statements about the prominence of AI. This importance can be summed up in Putin’s September 2017 speech: “Whoever becomes the leader in AI will rule the world.”2 This context has developed since 1956, but interest in this field has increased since 2010. Despite the existence of opponents and supporters in AI war applications, Daniel Araya and Meg King have provided predictions about the scale of the impact of AI on the future nature of war that have three possible positions: minimal effect, evolutionary effect, and revolutionary effect.3 This technology is viewed as a significant advantage for countries that possess it, benefiting both civilian and military sectors.

Specifically, China and the United States gain substantial economic and military benefits over their competitors, which could lead to a redefinition of the current balance of power. Gloria Shkurti Özdemir emphasizes that this technology should not be considered a unique weapon, but it should be regarded as an “enabler and all-purpose technology with multiple applications.”4 Therefore, while it can potentially enable several military innovations, it is not an army innovation itself.5 The study of AI extends beyond military and hardware applications; it also encompasses cyberspace and media, where psychological warfare, fake news, and manipulated videos can alter the speeches of prominent figures and politicians, as well as their facial expressions. This technology enables the creation and execution of attacks against rival states.

AI functions as a proxy instrument with even greater efficiency than traditional forms of proxy warfare in managing the dynamics of competition and conflict between state and non-state actors. To date, this technology has functioned as a strategic deterrent, shaping the dynamics of international authority and prestige and has remained a focal point of bargaining and competition among major powers such as the United States. The main question of this article is what place AI has in the U.S. military strategy and how much this new technology can help the United States in proxy wars. The United States seeks to use AI in the form of hardware and software to achieve the most in future fights with the least cost.6 In this regard, the U.S. Army is trying to conduct proxy wars in remote areas with the most negligible financial and human costs through remotely controlled military equipment, such as drones and robots. These platforms provide several advantages over traditional irregular warfare weapons: they are smaller and more cost-effective, offer unparalleled surveillance capabilities, and minimize risks to soldiers.7 The available evidence indicates that proxy wars through AI reduce the number of civilian casualties. In this context, the effective use of AI can positively impact civilian harm reduction.8 Lauren Gould argues that, contrary to proponents of using drones in warfare, “In practice, AI is accelerating the kill chain—the process from identifying a target to launching an attack.”9

Moreover, autonomous systems must be designed to minimize economic costs. This task is complex, as economic costs encompass not only the platform or munitions but also logistics, information technology, and the manpower needed for operation and maintenance. Furthermore, autonomy may be most cost-effective without human oversight, though this compromises control and safety. Therefore, autonomy may be best suited for missions that reduce overall warfare costs rather than those that replace manned missions.10 For instance, robots do not have to be expensive or complicated; the Ukrainian military has successfully used modified commercial drones against Russian invaders.11

Research Background

In a report by Maggie Gray and Amy Ertan entitled AI and Autonomy in the Military: An Overview of NATO Member States’ Strategies and Deployment, they suggested that AI and autonomous systems will play an increasing role in enabling future military operations. Gray and Ertan, pointing to the evidence of China and Russia’s active and aggressive efforts in acquiring military AI systems, emphasize the disastrous consequences of falling behind this technology. In addition to the importance of the military and weapons aspect, North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) states must share information among their members in the field of supplies and facilities between the members and the recruitment of specialist forces, as well as create sufficient confidence for the military systems to remain advanced.12 Brandon Tyler McNally wrote a thesis entitled “United States AI Policy: Building toward a Sixth-Generation Military and Lethal Autonomous Weapon Systems,” which discussed and explained the capacity of AI as a new revolution in changing the strategic balance of power. He believes the United States, entangled in the Middle East and pursuing a long-term strategy for AI, has reduced its readiness for the sixth generation of military power. The United States’ ability to harness talent and innovative capabilities across the military/civilian spectrum will be a determining factor in maintaining its strategic advantage over its competitors through the mid-twenty-first century.13

In her report entitled Artificial Intelligence and the Future of Warfare, Mary Louise Missy Cummings states that the development of autonomous military systems has been gradual at best, and its progress has been fragile compared to the autonomous systems of the commercial sector. Indeed, research costs and development in this direction will significantly impact its types and quality. One of the essential issues in this field is whether defense companies can develop and test safe and controllable autonomous systems, especially weapons capable of firing. In other words, using nascent technologies without comprehensive testing can put the military and civilians at unnecessary risk.14 Kai-Fu Lee’s book, AI Superpowers: China, Silicon Valley, and the New World Order, examines China’s progress in AI and discusses its tight competition with the United States for new technologies. China has developed at an astonishing and unexpected speed in AI and surpassed its rival, the United States. Kai Foley believes China will be the next superpower in the technology.15 AI and autonomous systems are increasingly crucial in shaping military power and strategic balance. The United States and NATO must expedite innovation, collaboration, and talent development to counter advances from rivals like China and Russia, while ensuring these technologies remain safe and controllable. Achieving this balance is vital for maintaining security, stability, and global influence in the coming decades.

Theoretical Framework

Offensive realism posits that a government can best ensure its security by maximizing its power. This concept has sparked considerable debate among realists. For instance, some realists argue that excessive force can undermine a state’s security, as it may provoke other states to counterbalance that power.16

John Mearsheimer argues that the anarchic nature of the international system is responsible for issues such as doubt, fear, security competition, and conflicts among great powers.17 States are compelled to maximize their offensive capabilities and prevent rivals from gaining advantages at all costs. A state’s ultimate goal is to achieve hegemony in the international system, as this is the only way to ensure its security fully. In this anarchic environment, the most effective strategy for maximizing safety is to pursue power maximization. However, one criticism of offensive realism is its inability to explain why costly wars sometimes occur against the interests of the initiating governments. Additionally, Mearsheimer and other realist analysts recognize that power maximization can be counterproductive, leading some countries to disaster.18

Proxy Wars in the Contemporary Era

The proxy war is a method between classical and modern war. A third actor manages this type of war to achieve strategic results. The host actor is out of the conflict, and their proxies enter this strategic field by providing financing, training, and weapons to the host. A proxy war is a logical alternative for states that seek to advance their strategic goals but refrain from engaging in direct, costly, and bloody war.19 One of the most widely used definitions for this concept during the Cold War belongs to Karl Deutsch. He defines proxy war as an international conflict in which two foreign powers use a third actor’s military might and other resources to align with their interests, goals, and strategies.20

The origin of proxy wars dates back to the Cold War, during which the Soviet Union engaged nonstate actors in conflicts instead of confronting the United States directly.21 After the Cold War, despite initial optimism about reduced conflicts and the emergence of pacifist models, war remained a dominant force in international politics. The expansion of the concept of “region” in security studies allowed regional actors to independently provide financial and military support to vulnerable groups and governments, thereby regionalizing proxy wars. Additionally, rising costs and the destructive impacts of direct warfare prompted both regional and global powers to adopt strategies focused on proxy conflicts. During these conflicts, two parties engage indirectly, with a third party acting on behalf of one side. The aim is to limit the conflict’s scale to prevent it from escalating into a full-scale war. Proxy wars typically occur in strategically significant areas near the rival’s borders or even within their territories, using internal resources for their execution.22 Scholars like Geraint Hughes argue that governments cannot serve as proxies, as history demonstrates that they will intervene when it aligns with their interests.23 Consequently, the intervention of a proxy agent may be negligible. In contrast, Yaakov Bar-Siman-Tov categorizes proxies into two types: those that intervene by force and those that do so voluntarily due to “compatibility of interests.”24 State A may initially request state B to represent it, whether through coercion or voluntary agreement.25

The following summary explains the total realistic approach to proxy wars. With proxy war and strategic changes, neorealists claim that states do not act with the rational decision-making process they enter into. Indeed, their decisions are related to the position of the respective actors and competitors in the system.26 The existence of new proxy wars somehow reproduces international anarchy within the state. Therefore, it is impossible to distinguish the domestic territory from the foreign domain.27 Offensive realists highlight the ability of states to initiate proxy wars driven by material capabilities, viewing the power of the sponsoring state as the most critical aspect of the discussion.28

When there is a lack of trust between states, proxy war becomes a tool to validate alliances and coalitions. Conversely, if state A is more powerful than state B, the best option for state B is to resort to a proxy war. Moreover, the importance of public opinion in democratic countries and concern about international reactions to direct entry into war with another country increases the tendency to proxy war.29 Many experts analyze this component within the framework of offensive realism, as it channels the hostile motives of conflicting actors toward maximizing power. Consequently, the costs of war are minimized due to the absence of direct confrontation with the host state.

From Early Concept to Strategic Leverage: The U.S. Artificial Intelligence Trajectory

The term AI was first coined by John McCarthy in 1956 when he held the first academic conference in this field. In this regard, Alan Turing wrote an article about the concept of machines that can simulate humans with the ability to perform intelligent tasks such as playing chess. Using the brainpower of experts to help others has always been the main driving force behind the development of expert systems. This issue is one of the most positive potentials of AI.30 In 2010, America’s big tech attracted more than 60 small AI companies.

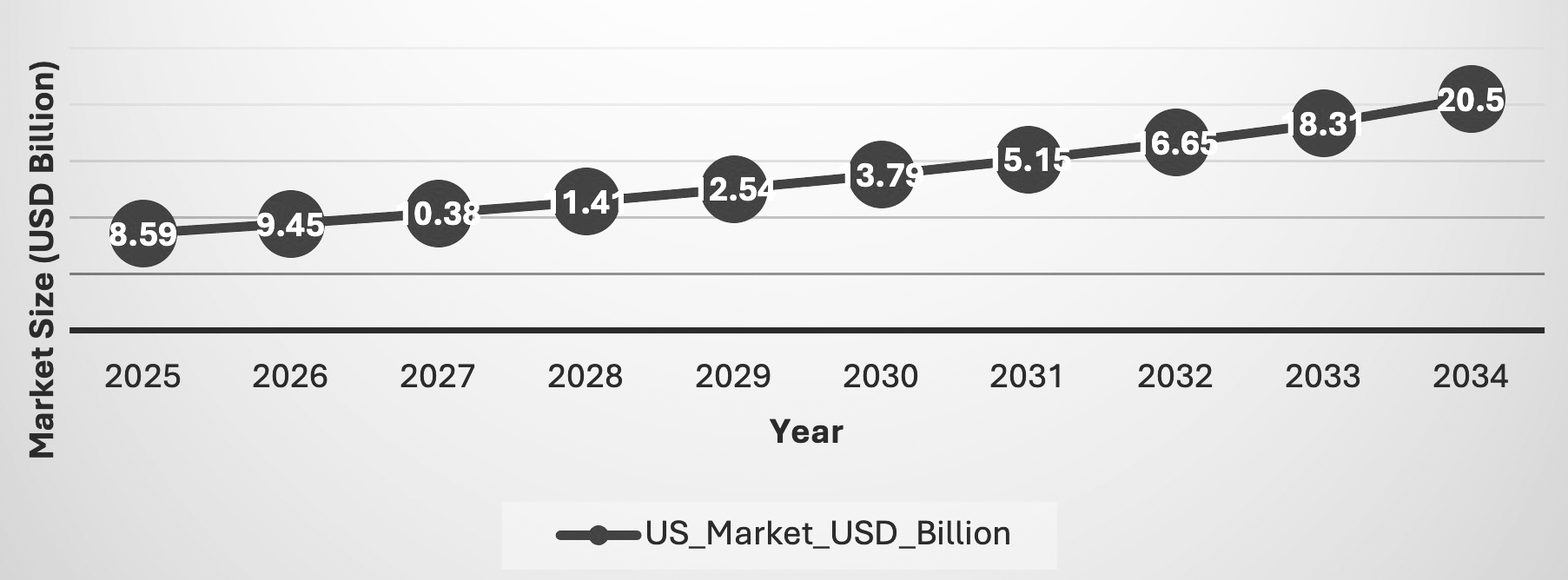

The President’s Council of Advisors on Science and Technology predicted that American companies will spend more than $100 billion annually on AI research and development by 2025. Many of the world’s largest AI companies are American. These companies pay more than $76 billion annually on research and development, making the total value of their investment markets more than $5 trillion.31 The research and development activities of U.S. multinational companies abroad can strengthen the technological ecosystem of other states in different ways. Some industry experts argue that if Microsoft had not established its Asian research, China could not have created its own AI ecosystem. In 2019, then chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, General Joseph F. Dunford, stated that Google’s work in China indirectly benefits the Chinese military. Despite these claims, Microsoft and Google have rejected them.32 The U.S. competition with China and its proxy wars, particularly in the Middle East, are significant factors. The U.S. AI market in aerospace and defense was valued at $7.82 billion (USD) in 2024 and is projected to reach approximately $20.50 billion by 2034.33

Military Dimensions

The deployment of AI as a part of the Third Offset Strategy of the United States was launched in 2014 by then Secretary of Defense Chuck Hagel to revive the U.S. military. The main focus of the Third Offset Strategy is on robotics and autonomy, in which AI plays an important role. Despite the opportunities that previous presidents created to become the world leader in AI, they always faced internal and external limitations.34 The Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA), which leads the Department of Defense regarding AI research and development, requested $3.17 billion in 2018 and $3.44 billion in 2019. Additionally, in 2018, DARPA announced a multiyear investment of more than $2 billion in new and existing programs called the AI Next Campaign.35

Figure 1. U.S. AI in aerospace and defense market size and forecast 2025 to 2034

Source: “AI in Aerospace and Defense Market,” Precendence Research, 10 July 2025.

The military uses AI, which is widely related to drone technology. Drones are uncrewed aerial vehicles that have a variety of uses. When drones were first used, they were controlled remotely and manually. However, today, the integration of drones equipped with AI and advanced technologies—such as high-resolution cameras, infrared and thermal imaging, microphones, various sensors, and both guided and unguided missiles—into the command, control, computers, communications, cyber, intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance (C5IRS) system greatly enhances the effectiveness of combat units. This advanced technology provides real-time, accurate information about events and allows for target destruction without endangering human lives, while simultaneously relaying situational updates to the battlefield command center.36 The following table shows examples of drones used by the Pentagon.

Table 1. Drones used by the Pentagon

|

Drones

|

Service

|

Performance details of drones in the U.S. armed forces

|

|

General Atomics MQ-1C Gray Eagle

|

Ground force

|

The MQ-1C Gray Eagle is a ground-force drone operated through a dedicated and highly reliable command system. It offers long endurance and supports multimission capabilities across strategic, operational, and tactical levels. Its payload includes a laser rangefinder, laser designator, synthetic aperture radar, ground moving target indicator, communications relay, and Hellfire missiles. The Gray Eagle has been deployed in various operational theaters, including Iraq, Syria, Afghanistan, South Korea, India, and the Republic of Niger.

|

|

AAI RQ-7

Shadow 200

|

Ground force

|

In the U.S. Army, the U.S. Marine Corps, the Australian Army, and the Italian and Swedish armed forces, the AAI RQ-7 Shadow 200 is used to locate and identify targets up to 125 kilometers from a tactical operations center. This system detects vehicles day and night from a height of 800 feet and a slope range of 3.5 kilometers. The Shadow UAV was deployed in Iraq in January 2004 and Afghanistan in August

2010 by the Australian Ministry of Defence.

|

|

Northrop Grumman RQ-4 Global Hawk

|

Air Force

|

This high-altitude and long-endurance drone can fly at 60,000 feet and stay in the air for more than 34 hours. The range of its cameras and sensors is confidential. However, the line of sight is about 340 miles. The U.S. Air Force has used it since 2001 in Afghanistan, Iraq, and North Africa.

|

|

General Atomics MQ-9A Reaper (a.k.a. Predator)

|

Air Force

|

The MQ-9A Reaper boasts an endurance of more than 27 hours, a speed of 240 knots true airspeed, and an operational ceiling of 50,000 feet. It has a payload capacity of 3,850 pounds (1,746 kilograms), which includes 3,000 pounds (1,361 kilograms) of external stores. This aircraft can carry five times more payload and has nine times the horsepower than other drones. Predator, the world’s first armed drone, mainly operates in Iraq, Afghanistan, and Pakistan.

|

|

AeroVironment RQ-20

|

Navy

|

This unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) is used for tactical information, surveillance, reconnaissance, targeting, maritime patrol, search and rescue, combating illegal smuggling, and supporting ground operations. Its length is 1.4 meters, and it weighs 6.3 kilograms. Only two people are needed to assemble it. Its functions have been in Afghanistan for reconnaissance.

|

|

AeroVironment RQ-11 Raven

|

Navy

|

This lightweight UAV is designed for rapid deployment and high mobility in military and commercial operations. Additionally, it fulfills the Army’s requirements for reconnaissance, surveillance, and low-altitude target acquisition. The U.S. Army, Air Force, Marine Corps, and Special Operations Command are the primary users of Raven. U.S. allies such as Australia, Italy, Denmark, Great Britain, and Spain also use it. It is the most advanced small unmanned aircraft system in the U.S. Armed Forces. Examples of its operational use have been in Afghanistan for surveillance and reconnaissance.

|

Sources: MQ-1C Gray Eagle Unmanned Aircraft System (MO-1C Gray Eagle) (Washington, DC: Department of Defense, 2019); “Shadow 200 RQ-7 Tactical Unmanned Aircraft System,” Army Technology, 13 March 2020; Hanan Zaffer, “Japan Receives First of Three RQ-48 Global Hawks from U.S.,” Defense Post, 18 March 2022; “MQ-9A ‘Reaper’,” General Atomics Aeronautical, accessed 20 August 2022; “RQ-20B Puma AE Small Unmanned Aircraft System (UAS),” Naval Technology, 15 August 2016; and “RQ-11 Raven Unmanned Aerial Vehicle,” Army Technology, 22 July 2021.

Unmanned systems operating underwater, on the surface, on land, and in the air require exceptionally high processing power to function autonomously.37 Mike Southworth, a production manager in the defense field, says an automated device needs different technologies to function properly. Analyzing large volumes of data and complex algorithms requires significant processing capabilities.38 AI is now a military reality. For example, guided weapon systems can make decisions independently of the human agent. Also, AI systems allow independent and autonomous decision making through a network of operators who work with computers. Such systems can perform several actions consecutively and quickly, even in uncertain conditions. Soon, intelligent and autonomous platforms will have faster maneuvering speed and use force more accurately than platforms that work with human guidance.39 AI has driven the development of autonomous weapons, including drones. They can perform a range of operations, from long-range aerial surveillance and deterrence to monitoring nuclear developments in other countries and executing attacks.40

DARPA has transferred newly developed defensive capabilities from its Guaranteeing AI Robustness Against Deception (GARD) program to the Chief Digital and Artificial Intelligence Office. GARD is part of DARPA’s broader artificial intelligence efforts, which the agency has pursued since its founding in 1958 and has intensified in recent years.

Currently, approximately 70 percent of DARPA’s programs focus on AI, machine learning, or autonomous systems. The Pentagon requested $10 million for the program in its fiscal year 2024 budget, but no funding was allocated for 2025 as the initiative is concluding.41

In President Donald J. Trump’s 2025 budget request, $20 billion is invested in primary research agencies, an increase of $1.2 billion during fiscal year 2023, to advance and strengthen America’s leadership in scientific research and discovery. An additional $32 million is earmarked for digital and public services and personnel to support AI talent.42 Research, development, testing, and evaluation have played a crucial role in advancing the department’s innovative initiatives to align with the Department of Defense’s strategic goals, bolster national security, and enhance defense capabilities. Of the $143.2 billion invested in this area, $17.2 billion is designated for science and technology, particularly in artificial intelligence and next-generation programs.43

These investments not only advance technological innovation but also shape how the United States leverages military strategy in contemporary conflicts. Today, military strategists use proxy wars to avoid the costs of direct conflict. Proxy wars serve as a strategic alternative for states aiming to achieve their goals while avoiding direct, costly, and bloody conflicts.44 Proxies provide a means to combat escalation. States frequently deny their support for these proxies; for instance, Russia asserted it was not involved in Ukraine, despite having funded various groups opposing the Kyiv government and supplied them with arms and support.45

Russia supported its former client states in Syria and Libya by deploying Chechen task forces and private military contractors. This aligns with its long-standing strategy of using private forces to extend its influence in areas where direct intervention would be challenging. This approach was evident in the Black Sea region and Ukraine, where Moscow’s use of “little green men” allowed it to operate below the threshold for U.S. intervention while maintaining plausible deniability.46

In the meantime, the United States is trying to avoid the expense and risks of military occupation and direct rule over a hostile state or nonstate actor through proxy forces. In addition to great powers like the United States, nonstate actors can achieve their strategic goals at a lower cost by using advanced technologies such as remote targeting, cyber warfare, and AI. Nevertheless, the investigation of the number of deaths on the battlefield in the Middle East shows that the number of deaths in proxy wars in the years after 2011 has increased compared to Middle East wars during the Cold War. Additionally, the number of refugees has been higher since the end of World War II, all of which were caused by civil and proxy wars in Syria, Yemen, and Libya following the Arab Spring in 2011.47 Statements like “we will develop innovative, low-cost, and compact approaches to achieve our security objectives” and “the U.S. military will invest as needed to ensure effective operations in anti-access and area denial (A2/AD) environments” reflect an understanding of the potential for utilizing proxy war strategies in regions where direct military intervention may be too costly or risky in the coming years.48

The Pentagon’s Use of AI in Military Strategy

The U.S. Project Maven is one of the most well-known cases of AI combining intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance applications. This project was designed to support the war against Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (ISIS) in Iraq and Syria. This ongoing project processes and interprets information received from videos taken by drones. As algorithms are developed, AI may be used for command and control, including managing battles, by analyzing large data sets with predictions to guide human activities.49 The U.S. military is trying to step into the field of AI in future wars. In this regard, internal Pentagon documents and senior government officials clearly show that the Department of Defense is working to prevent this technology’s rejection and create a plan that may be used in a new type of warfare.50

In June 2018, Google withdrew from the aforementioned Project Maven, which uses AI software, and then published a set of AI principles that indicated that the company did not use AI to create weapons and technologies that harm people. Defense officials have long worried that Google might aid China, America’s chief competitor in AI, and its withdrawal from Project Maven left the Pentagon frustrated and scrambling for alternatives. Maven, the military’s first serious AI experiment, aimed to create algorithms that could help intelligence analysts identify potential targets from drone footage, but Google’s exit underscored the Pentagon’s vulnerability in attracting top tech talent.51 Since then, Google has intensified its commitment as a military contractor. In early 2025, to capitalize on federal contracts available under Trump, the company abandoned its pledge not to develop AI for weapons or surveillance.52

The Pentagon is researching combat scenarios in which AI would be allowed to operate automatically after receiving instructions from a human. Although the Pentagon has promised to establish an ethical AI army, such an undertaking will take work. Of course, the Pentagon realizes that arming existing commercial drones with human cognitive skills through AI can turn them into valuable weapons for insurgent and terrorist forces. Drones can be used to collect sensitive information, bypass physical obstacles on the ground, and carry out air strikes with high efficiency. Meanwhile, political leaders want drones to have more autonomy and for the servicemembers to be able to delegate important and dangerous tasks to the drones. For example, in areas where the Global Positioning System (GPS) does not work or where there is severe electromagnetic interference, drones can significantly help the military forces with surveillance and reconnaissance.53

The limited progress in advancing autonomous military technologies stems not only from high costs and technical challenges but also from significant organizational and cultural resistance. In the United States, internal rivalries and a preference for manned systems have hindered the deployment of UAVs. For example, despite the Lockheed Martin F-22 Raptor’s technical issues and minimal combat use, the Air Force is considering restarting its costly production rather than expanding drone programs, even though UAVs like the Predator are far cheaper and capable of most missions. Similarly, the X-47B is a groundbreaking unmanned aircraft developed by Northrop Grumman for the U.S. Navy, demonstrating significant advancements in carrier operations and autonomous refueling.54 Both Services continue to prioritize the troubled, expensive Lockheed Martin F-35 Lightning II over unmanned alternatives. Many in the military accept drones only in support roles, as their broader adoption threatens traditional hierarchies and prestige associated with piloted aircraft.55 Conversely, drone pilots are akin to video gamers, disconnected from the real-world consequences of their actions.56 The Kratos XQ-58 Valkyrie serves as an excellent example of a stealthy unmanned combat aerial vehicle. Originally designed and built by Kratos, it was demonstrated to the U.S. Air Force through the Low-Cost Attritable Strike Demonstrator program, part of the Air Force Research Laboratory’s Low-cost Attritable Aircraft Technology (LCAAT) project portfolio. The LCAAT initiative aims to reduce the rising costs of tactically relevant aircraft by offering an affordable, lightweight solution as an unmanned escort or wingman alongside crewed fighter aircraft in combat.57

Armed drones can fly to bases thousands of kilometers away to destroy the intended targets. The main advantage of drones is that they allow the military to attack the enemy while minimizing damage and casualties. However, drone attacks cause significant collateral damage, so many innocent citizens are killed along with the intended target. To reduce the cost of operating drones, manufacturers are increasingly producing them so that they can run automatically; they do not need instructions and human interaction. However, the automatic operation of military weapons raises severe ethical issues about liability for collateral damage from brutal drone strikes. The separation of humans from the decision-making process of drones during drone strikes makes it unclear who is responsible for the consequences of drone strikes: the robot, the programmer, or the military.58 Therefore, it may be necessary to address the legal and ethical dilemmas posed by drones, whether due to the technology or its application.59 One of the main ethical dangers of drones is moral hazard. The low cost and growing accessibility of drone technology to various states and nonstate actors make targeted killings easier and, consequently, more frequent.60

In 2013, the prototype of the X47B autonomous drone landed, and in 2015, it performed automatic aerial refueling; in both cases, human intervention was only for the command to land or in-flight refueling, which was done by software. In 2016, the United States displayed 103 drones that flew together independently. The Pentagon described the move as systems that share a distributed brain to make decisions and coordinate with each other.61 In 2020, for the first time, an automatic drone operating with AI, without any human consultation, targeted the Libyan forces of General Khalifa Haftar.62 In addition to drones, the Department of Defense can employ other autonomous weapons. The Navy conducted a similar test in November 2016, when five uncrewed boats patrolled a particular section of the Chesapeake Bay and intercepted an opposing vessel.63 The Sea Hunter is the first uncrewed antisubmarine warfare ship that DARPA transferred to the Department of the Navy. It was the first to travel autonomously from California to Hawaii and then back.64

In a report by Foreign Policy, the U.S. military has provided a robotic dog named Spot to help with demining and unexploded ordnance in Ukraine. Boston Dynamics announced the removal of mortar shells and cluster munitions in formerly Russian-controlled areas near the capital of Kyiv.65 However, the Pentagon claims to use AI to help the military and not replace soldiers.

While the U.S. military will not allow a computer to pull the trigger, it has developed a “target recognition” system in drones, tanks, and infantry.66 Also, one of the features of AI is that it can act quickly.67 The U.S. Department of Defense must accept that nonstate groups and actors will acquire weapons powered by AI technology. These weapons are inexpensive for nonstate actors and, in contrast to nuclear weapons, are appealing because their development is relatively accessible to them. Even great powers may make AI weapons available to nonstate actors like conventional weapons.68 Alex Karp, CEO of military contractor Palantir, has stated that AI-enabled warfare and autonomous weapons systems have reached their “Oppenheimer moment.”69 The affordability and ease of deploying AI weapons prompt both governmental and nongovernmental actors to incorporate them into their military strategies, as they involve lower financial and human costs.

Pentagon’s AI Drones to Ukraine: A Proxy War Boost

U.S.-German autonomous software company Auterion has secured a Pentagon contract to provide 33,000 AI strike kits for Ukrainian drones, enhancing Kyiv’s efforts against Russia. This deal, part of Washington’s latest security aid package, will increase the use of Auterion’s technology in Ukraine tenfold, with deliveries anticipated by year-end. The technology has already been implemented in Kyiv and is currently utilized in autonomous combat missions against invading forces.70 Ukraine’s adoption of AI-enhanced weapons is not merely a step toward military modernization; it is a crucial act of survival. In an increasingly digitized battlefield, these systems provide speed, reach, and lethality while minimizing human risk. Ukraine’s experience highlights both the potential and dangers of such technologies.71 Ukrainian companies have developed various AI solutions for battlefield and defense applications. These include unmanned aerial and ground vehicles for tasks such as reconnaissance, surveillance, fire adjustment, target identification, logistics, and evacuation as well as electronic warfare systems to protect cities from enemy drones.72 The Ukraine war has demonstrated that both urban centers and military sites are vulnerable to low-cost drones. Cities, public venues, and critical infrastructure should be regarded as potential targets.73 Ultimately, the key factor in using drones in Ukraine is not about a less politically risky approach to warfare; it is primarily a matter of cost.74

Conclusion

The cost effectiveness and ease of deployment of AI weapons have enabled the United States to increase the use of this technology in line with its military strategies with less financial and forced cost. The recognition of AI technology as a part of the United States’ Third Offset Strategy shows the importance and strategic position of this concept for the Pentagon, which focuses on robotic and automatic weapons. Despite the Pentagon’s investments in projects such as Maven, due to the noncooperation of some companies and the opposition of a group of Pentagon officials due to violating moral and humanitarian rights, this project faced stagnation. Furthermore, the rise of AI presents challenges for nonspecialists and workers due to the potential for job displacement. A significant advantage of AI in proxy wars is its capacity to operate quickly and achieve optimal results by leveraging advanced hardware and software, thus gaining an edge in remote conflicts.

Drones enable the military to strike targets quickly and accurately. They can also communicate with other drones and jet fighters to locate targets more efficiently. These automated systems gather intelligence on various targets, providing valuable information for proxies. Additionally, drones facilitate easier and faster access to remote areas for both proxies and their supporters. Moreover, drones help save the lives of U.S. Marines and reduce collateral damage. Finally, by using drones, the United States can avoid deploying ground forces and aircraft carriers to equip and support its proxies abroad.

Endnotes

1. William C. Wohlforth, “The Stability of a Unipolar World,” International Security 24, no. 1 (Summer 1999): 5–41, https://doi.org/10.1162/016228899560031.

2. Gloria Shkurti Özdemir, Artificial Intelligence Application in the Military: The Case of United States and China (Ankara, Turkey: SETA, 2019).

3. Daniel Araya and Meg King, The Impact of Artificial Intelligence on Military Defence and Security (Waterloo, Canada: Centre for International Governance Innovation, 2022).

4. Özdemir, “Artificial Intelligence Application in the Military.”

5. Özdemir, “Artificial Intelligence Application in the Military.”

6. In this article, the authors describe artificial intelligence (AI) as a cutting-edge technology utilized in the design, production, and operation of drones and other automated weapons.

7. Seth G. Jones, The Tech Revolution and Irregular Warfare: Leveraging Commercial Innovation for Great Power Competition (Washington, DC: Center for Strategic & International Studies, 2025).

8. Patrick Tucker, “Special Operators Hope AI Can Reduce Civilian Deaths in Combat,” DefenseOne, 26 August 2024.

9. “Does AI Really Reduce Casualties in War?: ‘That’s Highly Questionable,’ Says Lauren Gould,” Utrecht University, 27 January 2025.

10. Jacquelyn Schneider and Julia Macdonald, “Looking Back to Look Forward: Autonomous Systems, Military Revolutions, and the Importance of Cost,” Journal of Strategic Studies 47, no. 2 (2024): 162–84, https://doi.org/10.1080/01402390.2022.2164570.

11. Christopher Wall, “The Ghost in the Machine: Counterterrorism in the Age of Artificial Intelligence,” Studies in Conflict & Terrorism (March 2025): https://doi.org/10.1080/1057610X.2025.2475850.

12. Maggie Gray and Amy Ertan, Artificial Intelligence and Autonomy in the Military: An Overview of NATO Member States’ Strategies and Deployment (Tallinn, Estonia: NATO Cooperative Cyber Defence Centre of Excellence, 2021), 19–22.

13. Brandon Teylor McNally, “United States Artificial Intelligence Policy: Building Toward a Sixth-Generation Military and Lethal Autonomous Weapon Systems” (PhD diss., Johns Hopkins University, 2021), 33–35.

14. M. L. Cummings, Artificial Intelligence and the Future of Warfare (London: Chatham House for the Royal Institute of International Affairs, 2017), 1–18.

15. Kai-Fu Lee, AI Superpowers: China, Silicon Valley, and the New World Order (Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin, 2018).

16. Dominic D. P. Johnson and Bradley A. Thayer, “The Evolution of Offensive Realism: Survival under Anarchy from the Pleistocene to the Present,” Politics and the Life Sciences 35, no. 1 (2016): 6, https://doi.org/10.1017/pls.2016.6.

17. Johnson and Thayer, “The Evolution of Offensive Realism,” 17–18.

18. Johnson and Thayer, “The Evolution of Offensive Realism,” 17–18.

19. Andrew Mumford, Proxy Warfare (Cambridge, UK: Polity Press, 2013), 1.

20. Vahít Güntay, “Analysis of Proxy Wars from a Neorealist Perspective: Case of Syrian Crisis,” TESAM Academy Journal 7, no. 2 (2020): 499, http://dx.doi.org/10.30626/tesamakademi.788857.

21. Güntay, “Analysis of Proxy Wars from a Neorealist Perspective,” 500.

22. Mohammad Hossein Ghanbari Jahromi, “Philosophy of Proxy Wars in the New Era,” Defense Policy Magazine 29, no. 13 (2019): 21, 25.

23. Geraint Hughes, My Enemy’s Enemy: Proxy Warfare in International Politics (Brighton, UK: Sussex Academic Press, 2012).

24. Yaacov Bar-Siman-Tov, “The Strategy of War by Proxy,” Conflict and Cooperation 19, no. 4 (1984): 263–73, https://doi.org/10.1177/001083678401900405.

25. Benjamin Vaughn Allison, “Proxy War as Strategic Avoidance: A Quantitative Study of Great Power Intervention in Intrastate Wars, 1816–2010” (conference paper, Midwest Political Science Association 76th Annual Meeting Conference, Chicago, IL, 5–8 April 2018), 3.

26. Güntay, “Analysis of Proxy Wars from a Neorealist Perspective,” 500.

27. Daniel Byman, Deadly Connections: States that Sponsor Terrorism (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2005), 37, https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511790843.

28. Byman, Deadly Connections, 39.

29. Jahromi, “Philosophy of Proxy Wars in the New Era,” 27, 46.

30. Chris Smith et al., The History of Artificial Intelligence (Seattle: University of Washington, 2006), 4, 16.

31. Roxanne Heston and Remco Zwetsloot, Mapping U.S. Multinationals’ Global AI R&D Activity (Washington, DC: Center for Security and Emerging Technology, 2020), 4, https://doi.org/10.51593/20190008.

32. Heston and Zwetsloot, Mapping U.S. Multinationals’ Global AI R&D Activity, 5.

33. “AI in Aerospace and Defense Market,” Precedence Research, 10 July 2025.

34. Adam Lowther and Stephen Cimbala, “Future Technology and Nuclear Deterrence,” Wild Blue Yonder (February 2020).

35. Özdemir, “Artificial Intelligence Application in the Military,” 14, 16.

36. Aleksandar Petrovski, Marko Radovanović, and Aner Behlic, “Application of Drones with Artificial Intelligence for Military Purposes” (paper presented at the 10th International Scientific Conference on Defense Technologies OTEH 2022, Belgrade, Serbia, 13–14 October 2022), 99.

37. AI makes it possible for autonomous surface vessels and underwater drones to be used in the following applications: autonomous sea mine detection and neutralization are known as mine countermeasures. Ashikur Rahman Nazil, “AI at War: The Next Revolution for Military and Defense,” World Journal of Advanced Research and Reviews 27, no. 1 (2025): 1998–2004, https://doi.org/10.30574/wjarr.2025.27.1.2735.

38. As quoted in Jamie Whitney, “Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning for Unmanned Vehicles,” Military & Aerospace Electronics, 26 April 2021.

39. Kenneth Payne, “Artificial Intelligence: A Revolution in Strategic Affairs?,” Survival 60, no. 5 (2018): 8–9, https://doi.org/10.1080/00396338.2018.1518374.

40. Jeremy Julian Sarkin and Saba Sotoudehfar, “Artificial Intelligence and Arms Races in the Middle East: The Evolution of Technology and Its Implications for Regional and International Security,” Defense & Security Analysis 40, no. 1 (2024): 97–119, https://doi.org/10.1080/14751798.2024.2302699.

41. Jon Harper, “DARPA Transitions New Technology to Shield Military AI Systems from Trickery,” DefenseScoop, 27 March 2024.

42. Ed Pagano et al., “President Biden Unveils Key AI Priorities in FY2025 Budget Request,” Akin, 20 August 2025.

43. Department of Defense, “Department of Defense Releases the President’s Fiscal Year 2025 Defense Budget,” press release, 11 March 2024.

44. Andrew Mumford, “Proxy Warfare and the Future of Conflict,” RUSI Journal 158, no. 2 (2013): 40–46, https://doi.org/10.1080/03071847.2013.787733.

45. Daniel L. Byman, “Why Engage in Proxy War?: A State’s Perspective,” Brookings, 21 May 2018.

46. Candace Rondeaux and David Sterman, Twenty-First Century Proxy Warfare: Confronting Strategic Innovation in a Multipolar World (Washington, DC: New America, 2019).

47. Rondeaux and Sterman, Twenty-First Century Proxy Warfare.

48. Mumford, “Proxy Warfare and the Future of Conflict,” 40–46.

49. Özdemir, “Artificial Intelligence Application in the Military,” 10–17.

50. Zachary Fryer-Biggs, “Inside the Pentagon’s Plan to Win Over Silicon Valley’s A.I. Exports,” Wired, 21 December 2018.

51. Fryer-Biggs, “Inside the Pentagon’s Plan to Win Over Silicon Valley’s AI Experts.”

52. Emma Jackson, “I’ve Worked at Google for Decades. I’m Sickened by What It’s Doing,” Nation, 16 April 2025.

53. K. Preetipadma, “Artificial Intelligence in Military Drones: How Is the World Gearing up and What Does It Mean?,” Analytics Drift, 14 August 2021.

54. “X-47B UCAS,” Northrop Grumman, accessed 9 September 2025.

55. Cummings, Artificial Intelligence and the Future of Warfare, 9.

56. Mark Bowden, “The Killing Machines,” Atlantic, September 2013.

57. “Uncrewed Tactical Aircraft,” Kratos, accessed 20 August 2025.

58. Anna Konert and Tomasz Balcerzak, “Military Autonomous Drones (UAVs)—From Fantasy to Reality. Legal and Ethical Implications,” Transportation Research Procedia, no. 59 (2021): 294, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trpro.2021.11.121.

59. Michael J. Boyle, “The Legal and Ethical Implications of Drone Warfare,” International Journal of Human Rights 19, no. 2 (2015): 107, https://doi.org/10.1080/13642987.2014.991210.

60. Boyle, “The Legal and Ethical Implications of Drone Warfare,” 121.

61. Özdemir, “Artificial Intelligence Application in the Military,” 19.

62. Charles Q. Choi, “A.I. Drone May Have ‘Hunted Down’ and Killed Soldiers in Libya with No Human Input,” Live Science, 3 June 2021.

63. Özdemir, “Artificial Intelligence Application in the Military,” 16.

64. Özdemir, “Artificial Intelligence Application in the Military,” 17.

65. Jack Deutsch, “Ukraine’s Bomb Squads Have a New Top Dog,” Foreign Policy, 22 June 2022.

66. Sydney Freedberg, “How A.I. Could Change the Art of War,” Breaking Defense, 25 April 2019.

67. Jeremy Straub, “Artificial Intelligence Is the Weapon of the Subsequent Cold War,” Conversation, 29 January 2018.

68. Daniel Egel et al., “A.I. and Irregular Warfare: An Evolution, Not a Revolution,” War on the Rocks, 31 October 2019.

69. David Gray Widder, Sireesh Gururaja, and Lucy Suchman, “Basic Research, Lethal Effects: Military AI Research Funding as Enlistment,” arXiv, 26 November 2024, https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2411.17840.

70. Rojoef Manuel, “33,000 AI Drone Strike Kits Headed to Ukraine in Pentagon Deal,” Defense Post, 29 July 2025.

71. Ramesh Jaura, “Ukraine War: Use of AI Drones Signals a Dangerous New Era,” Eurasia Review, 8 June 2025.

72. Vitaliy Goncharuk, Russia’s War in Ukraine: Artificial Intelligence in Defence of Ukraine (Tallinn, Estonia: International Centre for Defence and Security, 2024).

73 Viktoriia Rafalovych et al., Beyond the Border: What Ukraine’s Deep-Strike Drone Attack Means for the Future of Proxy and Drone Warfare (Brussels, Belgium: Centre of Youth and International Studies, 2025).

74. Dominika Kunertova, “Drones Have Boots: Learning from Russia’s War in Ukraine,” Contemporary Security Policy 44, no. 4 (2023): 576–91, https://doi.org/10.1080/13523260.2023.2262792.