https://doi.org/10.21140/mcuj.20251602002

PRINTER FRIENDLY PDF

EPUB

AUDIOBOOK

Abstract: This study investigates the militarization of space by the United States and China using the theoretical frameworks of technological determinism and the security dilemma. Data analysis of policy documents, military doctrines, and strategic literature reveals how technological advancements, mutual distrust, and dual-use technologies have transformed space into a contested domain. Findings indicate that the lack of international regulations and transparency exacerbates the risks of miscalculation and conflict. The study suggests actionable measures, including binding treaties, enhanced transparency, and conflict resolution mechanisms to promote peaceful space exploration. This research contributes to the broader discourse on space security by offering insights into managing militarization challenges in a rapidly advancing technological era.

Keywords: strategic stability, space militarization, technological determinism, security dilemma, military doctrines

Introduction

In 1962, President John F. Kennedy famously declared, “We choose to go to the Moon in this decade and do other things, not because they are easy, but because they are hard,” embodying the aspirational vision that once unified humanity in space exploration.1 However, outer space, once a symbol of collective progress, has now become a focal point of geopolitical competition. In 2022, global space-related spending surpassed $100 billion reaching $546 billion, highlighting the growing strategic significance of space.2 The intensifying militarization, particularly between the United States and China, reflects a shift in global dynamics. This rivalry, fueled by dual-use technologies and the recognition of space’s critical role in national security, economic prosperity, and technological leadership, presents both new opportunities and risks to global stability.

Space has historically represented humanity’s highest aspirations, exemplified by milestones like the Apollo 11 Moon landing in 1969 and the creation of the International Space Station, which began construction in 1998 and was finished in 2011.3 The 1967 Treaty on Principles Governing the Activities of States in the Exploration and Use of Outer Space, Including the Moon and Other Celestial Bodies (colloquially known as the Outer Space Treaty [OST]) enshrined the principle of using space for peaceful purposes, free from weapons of mass destruction. However, as Scott Sagan noted, “Seemingly harmless inventions have often been repurposed for destructive ends.”4 Advances in dual-use technologies blur the lines between civilian and military applications, driving the current U.S.-China space competition. Strategic priorities are increasingly replacing collaborative aims.

Here, a distinction is necessary between the militarization and weaponization of space. Militarization is the incorporation of space systems into military activity like surveillance, navigation, reconnaissance, and missile warning functions, which is already advanced. Weaponization, conversely, involves the deployment of offensive and defensive weaponry in or through space with the intent to destroy or incapacitate targets. Contrary to general concerns, the complete weaponization of outer space has not yet been achieved.5 Thus far, as of 2025, there have been initial experiments like China’s 2007 direct-ascent antisatellite weapon (ASAT) test, the United States’ 2008 intercept of USA-193 in Operation Burnt Frost, India’s Mission Shakti in 2019, which successfully tested an ASAT weapon by destroying a satellite, and Russia’s destructive test in 2021 against Cosmos-1408. Since then, there have been nondestructive demonstrations such as Russia’s 2020 co-orbital test along with other directed-

energy and co-orbital experiments.6 These are only steps in the direction of weaponization and do not constitute a continued presence of weapons in orbit.

This research thus centers on militarization because it reflects the competitive dynamics already transforming strategic stability. Militarization via dual-use technologies, strategic doctrines, and security dilemmas pushes escalation and suspicion well before weaponization occurs. By examining militarization as an independent driver of instability, this article underscores how space competition is undermining strategic stability even without permanently stationing weapons in orbit.

Figure 1. U.S. defense support program early warning satellite Liberty, deployed to provide warning of missile launches during the Gulf War

Source: Curtis Peebles, High Frontier: The US Air Force and the Military Space Program (Washington, DC: Air Force History and Museums Program, 2020).

Theoretical frameworks such as technological determinism and the security dilemma offer insights into this competition. Technological determinism suggests that technological advances inherently drive strategic behavior, as seen in developments in satellite and antisatellite technologies, which spark an arms race in space. The security dilemma explains how defensive actions by one state are perceived as offensive by another, intensifying distrust and militarization. These dynamics fuel the U.S.-China rivalry, with broader implications for global security.

The militarization of space poses significant challenges to global strategic stability, particularly regarding crisis management, arms race stability, and deterrence. Space-based infrastructure, vital for communication and surveillance, is highly vulnerable, as demonstrated by China’s 2007 antisatellite test, which created debris threatening vital systems. Additionally, arms race stability is compromised as nations race to develop superior space capabilities, risking unsustainable escalation.7 Deterrence is complicated by the ambiguity of space technologies, where dual-use satellites make it difficult to distinguish defensive from offensive actions, increasing the risk of miscalculation.8

This research examines the vulnerabilities arising from space militarization, emphasizing the need for enhanced governance, transparency, and international cooperation to mitigate these risks. As space becomes a more critical domain, the challenge is to ensure it does not evolve from peaceful exploration into unchecked exploitation and conflict. While exploration reflects collective scientific progress, exploitation highlights the pursuit of strategic and economic gains that risk augmenting rivalry. Addressing these issues will be crucial to maintaining global strategic stability and securing a sustainable future for outer space.

As humanity ventures further into the final frontier, the stakes have never been higher, with national security, technological leadership, and the stability of global strategic relationships hanging in the balance. The militarization of space not only threatens the fragile equilibrium of global strategic stability but also jeopardizes the potential for space to remain a domain of peaceful exploration and shared progress. By understanding the drivers, risks, and implications of this phenomenon, this research aims to contribute to the development of strategies that ensure a secure and sustainable future for outer space.

U.S.-China Space Militarization: Potential Implications

The escalating rivalry between the United States and China for space militarization has raised significant concerns about its implications for strategic stability. As both nations actively pursue advanced space capabilities, the potential implications on international security are multifaceted. The development and deployment of space-based weapons and ASAT capabilities by the United States and China have amplified the concerns about the risk of an arms race extending beyond Earth’s atmosphere. The absence of clear international norms and regulations governing space militarization further complicates the threat to strategic stability, as the potential for misunderstandings, miscalculations, and unintentional escalations looms large. The lack of established protocols for managing potential conflicts in space heightens the risk of destabilizing events that could impact Earth. The interdependence of modern economies and the global nature of modern security challenges places emphasis on a comprehensive and collaborative approach to address the implications of U.S.-China space militarization on strategic stability. There is a dire need to analyze the evolving dynamics of space militarization between the United States and China, exploring the associated risks to strategic stability and proposing viable frameworks for international cooperation. If left unchecked, the increasing militarization of space between the United States and China is likely to disrupt strategic stability.

This research provides a holistic analysis of the escalatory U.S.-China space militarization race and its potential impact on global strategic stability, crisis escalation risks, as well as deterrence issues. It also aims to examine the drivers behind the absence of robust arms control legislatures for space-based weapons and identify policy agendas for cooperative actions that can mitigate these threats to ensure a secure future for space as an equitable realm for peaceful explorations and sustainable global security.

Research on the Militarization of Space

The literature on space militarization presents a range of perspectives, examining strategic stability, historical comparisons, and emerging threats. Historical parallels, as discussed in Pericles Gasparini Alves’s Prevention of Arms Race in Outer Space: A Guide to the Discussions in the Conference on Disarmament and Curtis Peebles’s High Frontier: The U.S. Air Force and the Military Space Program, provide valuable insights into the Cold War’s space race between the United States and the Soviet Union.9 These works argue that the current rivalry between the United States and China in space bears similarities to that era. However, the world today is markedly different, shaped by multipolar dynamics and significant technological advancements. With new spacefaring nations entering the field, the challenge lies in crafting strategies to prevent the further militarization of space.10

Bleddyn E. Bowen’s Original Sin: Power, Technology and War in Outer Space and Dean Cheng’s works emphasize the realist perspective, where national security concerns drive space militarization.11 Realism highlights the strategic advantage of controlling space assets vital for modern military operations. Yet, this viewpoint often overlooks other important factors such as economic interests, domestic politics, and technological progress. Introducing alternative theories, such as liberalism—focused on international cooperation or constructivism (emphasizing the role of norms and perceptions) could enrich the understanding of space governance.12

The rapid development of technologies like hypersonic weapons, directed-energy systems, and cyber capabilities poses challenges to existing frameworks such as the Outer Space Treaty.13 These advancements blur the lines between civilian and military applications. Their military character is evident: hypersonic weapons are being tested as nuclear-capable delivery systems that oppose space-based early warning; directed-energy weapons are designed to blind or disable satellites, a key military enabler; and cyber operations increasingly attack satellite command networks, which was seen in the 2022 hack of an American satellite owned by Viasat, which impacted their KA-SAT network. The hack occurred on the first day of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine on 24 February 2022.14 China’s 2021 test of a hypersonic glide vehicle illustrates the manner in which such technologies directly challenge strategic stability, observing that the OST’s focus on weapons of mass destruction in space does not extend to the militarization of such new platforms.15 Works like The Hypersonic Revolution by Richard P. Hallion underscore how technological determinism—the idea that new technologies drive progress and competition intensifies these challenges.16 Ahmad Khan and Sufian Ullah’s analysis points out the OST’s shortcomings, particularly its lack of enforcement mechanisms to regulate dual-use technologies and ASAT weapon tests.17 To address these gaps, the development of new treaties with robust verification mechanisms and risk-reduction strategies is critical. Confidence-building measures and transparency protocols are essential to prevent miscalculations that could escalate tensions.18 While in the current geopolitical landscape of U.S.-China tensions, Russia’s estrangement, and India’s growing counterspace capabilities, such negotiations seem unlikely; however, voluntary moratoria on destructive ASAT testing as the United States pledged in 2022, later joined by Japan, Canada, and some other nations and track 2 diplomacy could offer modest yet feasible ways to reduce risks until broader agreements become possible.19

Articles like Ulrich Kuhn’s “Strategic Stability in the 21st Century: An Introduction” and Parliamentary reports like Claire Mills’s The Militarisation of Space explore the deterrence dynamics between the United States and China.20 While deterrence remains central to strategic stability, applying it to space introduces unique challenges. Unlike nuclear deterrence, space deterrence faces issues such as crisis instability and the dual-use nature of technologies. Addressing these concerns calls for innovative governance frameworks.21 Effective communication channels and confidence-building measures can help avert unintended escalations. Decentralized governance models and multistakeholder approaches, as suggested by James Clay Moltz’s article “The Changing Dynamics of 21st Century Space Power,” could build trust and reduce risks.22 Prioritizing international norms over unilateral measures is essential for long-term stability.

Critical Gaps in Legal Frameworks and Treaties

Despite the depth of existing literature, several critical gaps remain unaddressed. The limitations of current treaties, such as the Outer Space Treaty, highlight the urgent need for updated legal frameworks to address dual-use technologies and emerging threats like hypersonic weapons and directed-energy systems. The lack of enforcement mechanisms further exacerbates the challenge of ensuring compliance. Additionally, the unique characteristics of space deterrence, particularly its distinction from nuclear deterrence, remain insufficiently explored. The literature often downplays the risks of crisis instability and unintentional escalation in space, which could trigger conflicts.

Another overlooked aspect is the need for robust verification systems and effective communication channels to build trust and reduce risks. The proliferation of weapons in space, combined with inadequate frameworks to regulate their use, poses a significant threat to strategic stability. Furthermore, the concept of “peaceful use” of outer space remains ambiguously defined, especially concerning dual-use technologies that blur civilian and military applications. Greater clarity and consensus are required to guide international cooperation and governance. Finally, there is a lack of emphasis on interdisciplinary approaches that integrate technological, legal, and policy perspectives to ensure the long-term sustainability of space activities.

This article highlights the need to address the limitations of existing treaties, incorporate diverse theoretical perspectives, and propose actionable solutions to mitigate the risks of space militarization. Further research is needed to develop effective verification systems, clearly define peaceful uses of outer space, and explore interdisciplinary approaches.

Theoretical Framework

This research uses the theories of technological determinism and security dilemma, which provides a broader understanding of the topic under consideration. Technological determinism provides insights into the objectives of the United States and China in space and analyses the implications of their endeavors on global strategic stability. On the other hand, the security dilemma thoery explores the threat perceptions of the United States and China and elucidates the need and the security concerns of both states in the space domain.

Theoretical Frameworks

Technological Determinism

Technological determinism asserts that technological advancements inherently drive societal and strategic transformations. In the context of U.S.-China space militarization, this theory explains the inevitability of advancements in space technologies fueling competitive dynamics. For instance, China established the Strategic Support Force (SSF) in 2015 to centralize space, cyber, and electronic warfare missions. In 2024, it disbanded the force and reorganized its functions into three separate entities: the Space Force, the Cyber Force, and the Information Support Force. This has triggered reciprocal measures from the United States such as its Space Force in 2019 and development of advanced satellite surveillance systems.23 While these developments were not a direct response to the SSF, Department of Defense analyses made repeated references to adversaries (mainly China and Russia) counterspace advances as central arguments for establishing an independent Service dedicated to space. These actions reflect the autonomous trajectory of technological progress, where each state’s innovations compel the other to respond, perpetuating an escalation spiral. The development of ASAT weapons by both nations further illustrates this deterministic cycle, as each perceives the other’s advancements as a threat requiring a countermeasure.

While technological determinism provides valuable insights into the inevitability of technological progress shaping military strategies, it often downplays the role of human agency and governance. The theory assumes an unyielding trajectory of innovation, yet history shows that policy interventions and cooperative frameworks can mitigate escalatory tendencies, as seen in arms control efforts during the Cold War.

Security Dilemma

The security dilemma highlights how defensive measures by one state can be perceived as offensive by another, fostering mutual suspicion. This is evident in China’s BeiDou navigation system. Although framed as a civilian project, its origins lie in the 1995–96 Taiwan Strait crisis, when Chinese leaders came to believe that reliance on the American controlled GPS had undermined their missile operations, underscoring escalation based on one state’s actions that accelerated the other state’s technology development in response:

According to a retired Chinese general, China’s military concluded that an alleged disruption to GPS caused it to lose track of some ballistic missiles it fired into the Taiwan Strait during the 1995–1996 Taiwan Strait Crisis. This was “a great shame for [China’s military] . . . an unforgettable humiliation. That’s how we made up our mind to develop our own global [satellite] navigation and positioning system, no matter how huge the cost. BeiDou is a must for us. We learned the hard way.”24

This episode was interpreted in Beijing as humiliation and a stark reminder of strategic vulnerability, reinforcing the determination to build an independent navigation system regardless of costs. While conceived from a defensive logic of autonomy, BeiDou’s evident military utility has raised alarm in the United States. Similarly, the U.S. deployment of the X-37B spaceplane—capable of rapid orbital maneuvering—has spurred concerns in China about potential offensive uses. The dual-use nature of these technologies underscores the difficulty of distinguishing between defensive and offensive intentions, thereby escalating tensions and complicating deterrence.

Historical parallels, such as the Cold War space race, reveal how perceptions of technological superiority often spiral into arms races. However, the security dilemma’s assumption of rational actors sometimes overlooks ideological or economic motivations that drive state behavior. For instance, China’s investment in space infrastructure is not solely defensive but also tied to broader economic ambitions, such as the Belt and Road Initiative’s space component.

The Fragile Balance: Strategic Stability Risks in the U.S.-China Space Race

Imagine a stool with three legs—unsteady, yet remarkably sturdy. This fragility accurately represents the intricate balance of power referred to as strategic stability, which serves as the foundation of international relations. It represents a condition in which powerful nations are deterred from employing military force against one another.25 The preservation of this delicate equilibrium is crucial to avert conflict and uphold peace.

The escalating rivalry between the United States and China in space militarization is undermining the core concepts of strategic stability, causing uncertainty about their effectiveness and giving rise to concerns about the future of global security. As the fight for supremacy in space grows stronger, the possibility of wars, uncontrolled arms races, and weakening deterrent systems becomes a significant concern, leading to a pressing need to consider the consequences for the future of peace on Earth. By discussing the concept of strategic stability and its tiers, this research illustrates implications of the U.S.-China space militarization arms race, crisis stability, and deterrence stability.

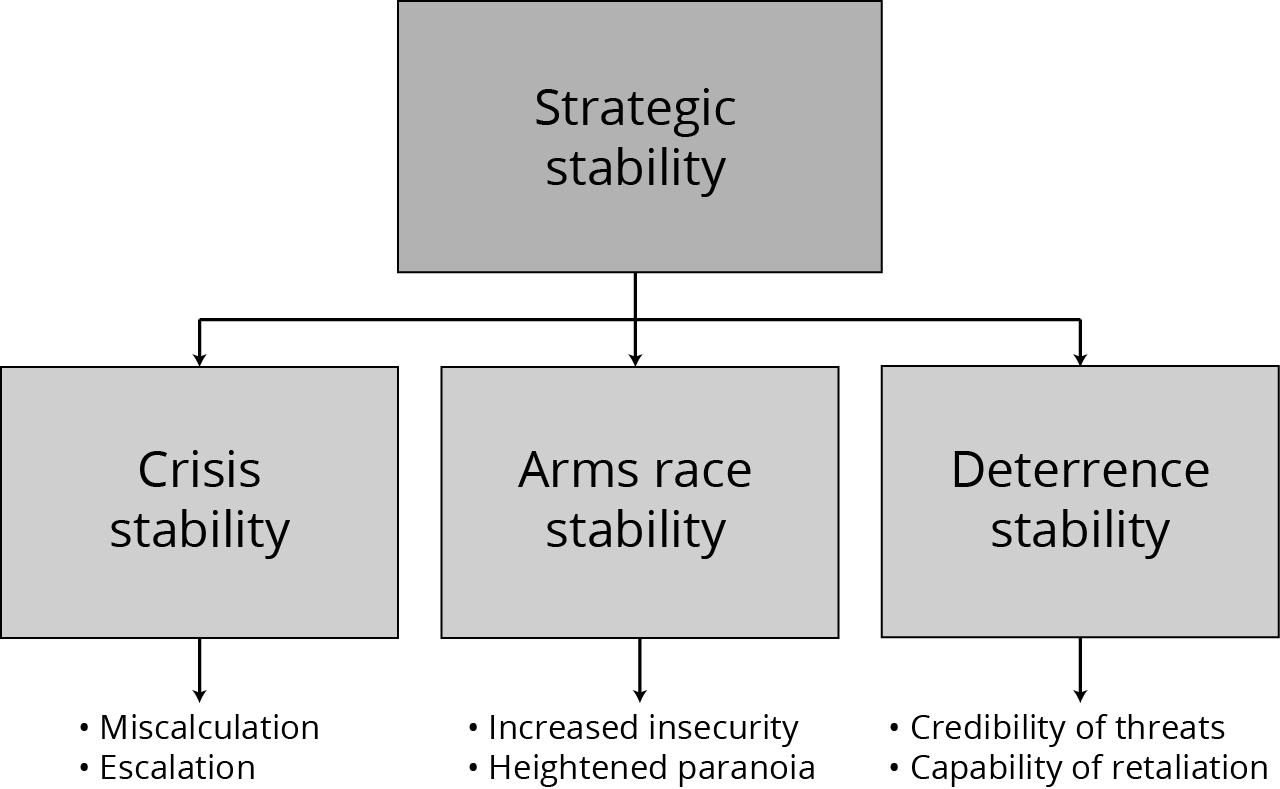

Tiers of Strategic Stability

The concept of strategic stability is based on three core pillars: crisis stability, arms race stability, and deterrence. Crisis stability refers to the capacity of nations to effectively and peacefully address and resolve international crises. This is crucial because even minor crises have the potential to grow into more significant wars. Various elements, including miscalculations, escalation, and unintended accidents can erode crisis stability. Miscalculation arises when a nation inaccurately assesses the intentions of another nation. Escalation is the process by which a situation intensifies and becomes unmanageable. Unintentional accidents might also give rise to conflict.

Figure 2. Tiers of strategic stability

Source: courtesy of author, adapted by MCUP.

Arms race stability denotes a state in which nations do not feel obligated to constantly augment their military capabilities. When nations participate in an arms race, it can develop a sense of insecurity and paranoia, which heightens the likelihood of conflict, whereas deterrence is the capability of a state to discourage an opponent from launching an attack against it. Deterrence relies on the prospect of retaliation. For a deterrent threat to possess credibility, it must be perceived as believable. The other nation must have confidence that the deterring nation will genuinely carry out its threat in the event of an attack. To possess the capability of deterring, a threat must possess a capacity to cause substantial harm to the aggressor.26

These pillars interact to establish a conducive environment in which countries experience a sense of security and are less inclined to engage in armed aggression. The process of militarizing space by the United States and China is causing substantial challenges for the three tiers. The likelihood of crises turning into conflicts is being heightened, along with the destabilization of arms race dynamics and the undermining of conventional deterrent approaches. The production and placement of sophisticated space-based weapons and technologies create additional sources of instability in global affairs, presenting substantial obstacles to the preservation of peace and security in outer space.

Risk of Crisis Instability and Escalation

The increasing development and deployment of offensive counter-space capabilities by both the United States and China raises significant concerns for crisis instability in the space domain. Although these capabilities may seem small, they have the capability to greatly destabilize the fragile balance of power and set off a series of destabilizing actions and reactions between these two prospective rivals. Crisis instability pertains to the susceptibility of the space domain to intensify tensions and conflicts during times of crisis or increased geopolitical rivalries.27 The inherent threat stems from the fact that even very slight improvements to offensive counter-space capabilities can cause significant discomfort and anxiety among competitor states, resulting in increased tensions and intensifying competition. The unpredictability of crisis instability in space is exacerbated by the ambiguity surrounding the consequences of such situations. Although the precise outcome of a space crisis cannot be foreseen, the risk of crisis instability is significant and is projected to increase as the United States and China further develop offensive counter-space capabilities.

Crisis Instability and the Offense-Defense Conundrum in Space

Thomas C. Schelling illustrates crisis instability through a scenario where armed individuals fear the other will shoot first, prompting preemptive action.28 This analogy mirrors space militarization, where the United States and China, driven by strategic distrust, may consider first strikes advantageous to avoid perceived vulnerabilities. The asymmetric benefits of preemption—particularly in neutralizing ASAT capabilities—can incentivize rapid, decisive action, escalating tensions.

Space conflict risks are heightened by reduced human cost and the strategic imperative to maintain dominance. For example, the United States may opt for a preemptive strike to incapacitate China’s ASAT systems, viewing this as essential to protect critical assets and strategic dominance. However, such measures risk triggering uncontrollable escalation.29 Retaliatory cycles could destroy satellites, disrupt global communications, and create long-term space debris, jeopardizing space stability.

Additionally, the U.S.-China rivalry in space is also exacerbated by ambiguity surrounding offensive and defensive maneuvers. Unlike terrestrial warfare with defined boundaries, space operations lack clarity.30 For instance, destroying a satellite might be framed as defensive, but without sovereignty in orbit under the OST, such acts are more likely interpreted as strategic aggression. This dual-use nature of technologies like lasers and cyber tools further blurs distinctions, complicating intent interpretation.

Such uncertainty fosters crisis instability. Imagine China destroying a U.S. surveillance satellite passing over its territory claiming defense, while the United States perceives it as a hostile act undermining intelligence capabilities. Current norms like the OST guidelines for peaceful use, the United Nations Committee on the Peaceful Uses of Outer Space norms, and more recent political undertakings like the U.S. commitment not to conduct destructive ASAT tests offer some constraint.31 However, they are voluntary, sporadically followed, and have no strong enforcement, so the threats of miscalculation and escalation remain.32

The disparity in interpretation can exacerbate suspicions and intensify animosity among states, hence augmenting the likelihood of conflict escalation. Perception has a critical role in the interpretation of actions in space.33 Engaging in the destruction of an adversary’s satellite, even in a defensive manner, when it is located above your own territory, may be interpreted as an aggressive action. For example, in the event that a U.S. missile defense system successfully neutralizes a Chinese satellite that was inadvertently approaching low-Eart orbit over U.S. territory China may perceive it as an unwarranted act of aggression, despite the U.S. intention to safeguard itself from an unanticipated but potential threat.

Deploying ASAT weapons exacerbates this offense-defense conundrum by lowering conflict thresholds. If either the United States or China employs ASAT systems, mutual vulnerability could spiral into large-scale conflict, driven by reciprocal escalation and mistrust.

Vulnerability of Space Centers of Gravity: A Threat for Crisis Escalation

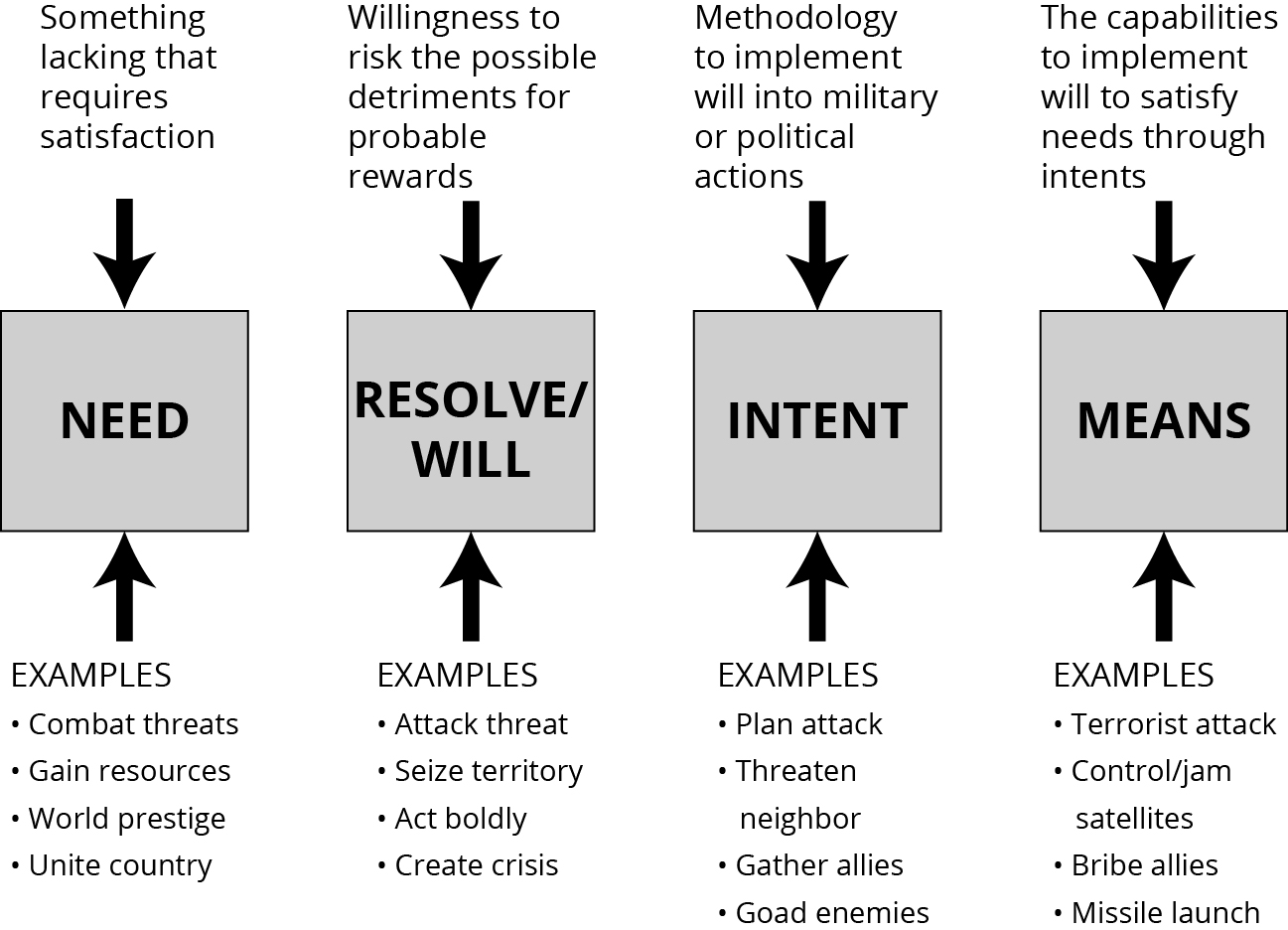

Space plays a pivotal role in national power, serving as a key battleground in U.S.-China rivalry. This competition for strategic superiority is not merely hypothetical but poses a genuine risk of escalating into conflict. At the heart of this struggle are centers of gravity (COGs), critical resources, capabilities, and advantages that enable states to achieve objectives and exert influence in space.34 These include satellites, space stations, ground control facilities, launch sites, and communication networks, forming the cornerstone of a nation’s space infrastructure.35

The race to secure dominance over COGs has profound implications for crisis stability. Significant investments by both nations in space infrastructure mean that any perceived threat to a COG could trigger a “use it or lose it” mindset, prompting preemptive strikes and initiating a perilous cycle of escalation. This competition is further exacerbated by the intrinsic vulnerabilities of space COGs, such as the limited maneuverability of satellites.

Military strategists in both nations prioritize identifying and exploiting weaknesses in their opponent’s COGs. Through wargaming simulations, they evaluate scenarios to devise countermeasures and preemptive strategies. However, preemptive actions based on incomplete intelligence risks miscalculations, misunderstandings, and unintended consequences, potentially escalating into a large-scale space conflict. Such hostilities amplify the risks of destabilization, undermining crisis management and intensifying global tensions.

To mitigate these risks, both nations must prioritize dialogue, transparency, and strategic restraint. Without these measures, the competition for space COGs threatens to destabilize global security and escalate conflicts into uncharted territory.

Figure 3. The center of gravity depicting the need, will, and intent of any state or military force to make decisions, strategies, devise a course of action, and shortlist means to accomplish its objectives and vested interests

Source: courtesy of author, adapted by MCUP.

Resource Competition and Quest for Dominance: A Threat to Global Peace

Both the United States and China recognize the immense strategic importance of space resources as pivotal to achieving geo-economic leadership and asserting global influence. Control over critical space positions and regulatory frameworks grants these nations the ability to shape wealth distribution, assert dominance, and influence the emerging global order.36 This high-stakes competition increasingly raises the prospect of unilateral sovereign claims or territorial appropriation in space, such as declaring exclusive economic zones or defense identification zones.37 Although there are some states, like the United States, that have committed to restraint on ASAT testing that is destructive, such steps do not respond to wider sovereignty issues. Unilateral assertions of space territory or resources would violate Article II of the OST, which forbids national appropriation of outer space, and invite defensive escalation.38

In this context, one actor’s attempts to assert dominance may trigger coercive countermeasures from the other, aimed at preserving national identity, strategic objectives, and geopolitical status. These measures could range from targeted military interventions to leveraging economic tools, such as disrupting supply chains or neutralizing critical assets. The dual-use nature of space technologies—serving both civilian and military purposes—further compounds the difficulty of distinguishing peaceful endeavors from aggressive maneuvers. Perceived threats, like ASAT capabilities, often blur the line between defense and offense, intensifying mutual distrust.

China’s 2007 direct-ascent capability test, designed to destroy satellites and augment missile defense, exemplifies this duality. The precedent for destructive ASAT testing was first set by the United States in 1985 and reaffirmed in 2008 with the intercept of the USA-193 satellite.39 Chinese adventure, however, marked the first such demonstration in the twenty-first century and set a precedent that stoked concerns about space weaponization.40 Similarly, in 2008 the U.S. interception of a satellite using missile defense systems demonstrated the inherent ambiguity of dual-use technologies, further destabilizing strategic perceptions.41

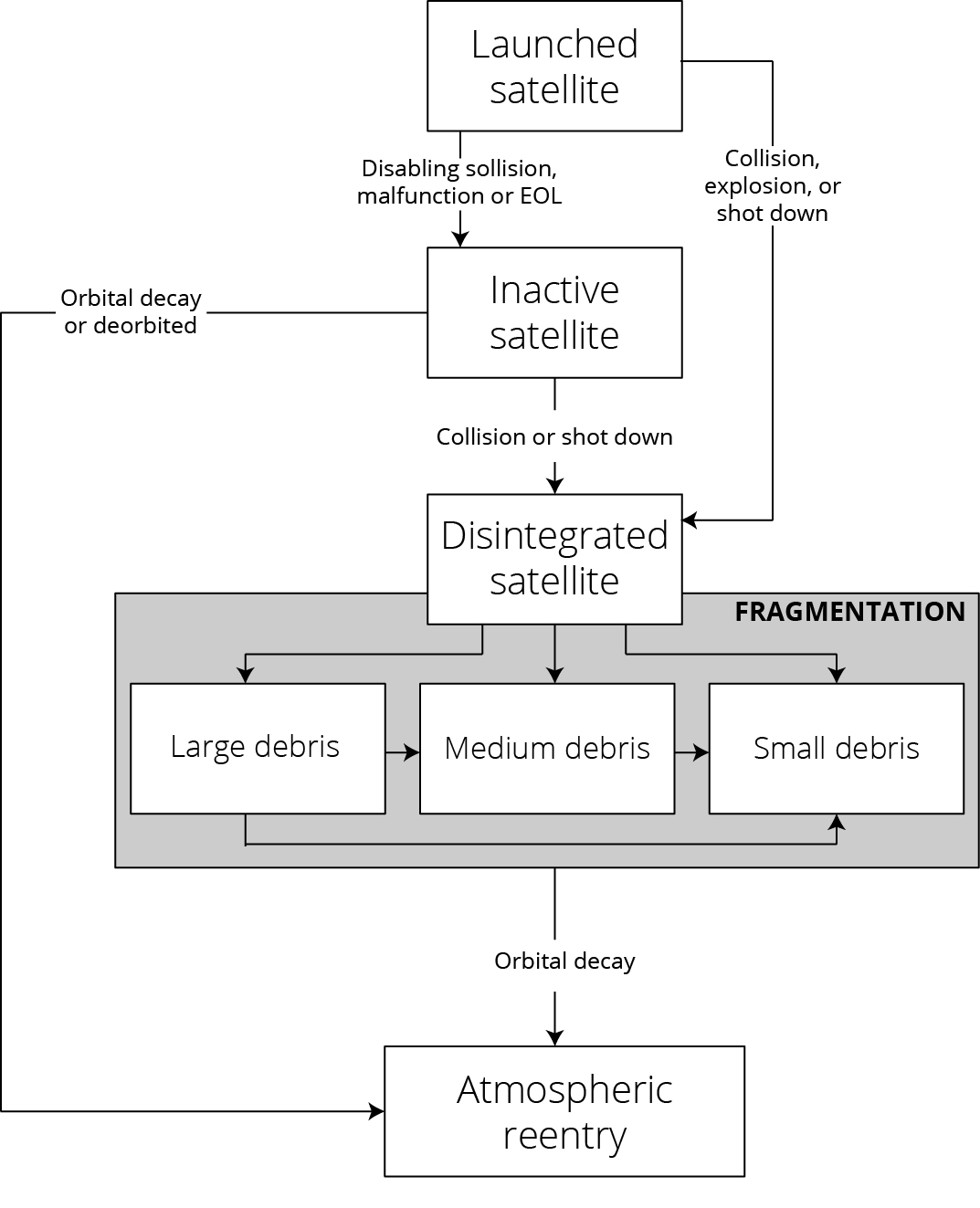

Figure 4. Hypothetical illustration of Kesseler Syndrome depicting how space accidents causing debris can lead to inadvertent escalations

Source: Bettina M. Mrusek, “Satellite Maintenance: An Opportunity to Minimize the Kessler Effect,” International Journal of Aviation Aeronautics and Aerospace 6, no. 2 (2019): https://doi.org/10.15394/ijaaa.2019.1323.

The crux of the challenge lies in deciphering intentions. Misjudging defensive postures as offensive threats, or underestimating provocations, risks spiraling tensions into conflict.42 The opacity surrounding space activities amplifies the dangers of miscalculation and reactionary cycles. To avert escalation, the United States and China must prioritize transparency and dialogue, fostering mutual understanding to ensure that space remains a realm of stability, cooperation, and shared progress.

The Domino Effect: A Hair-Trigger Threat

Satellites are marvels of engineering, but they are expensive and intricate pieces of machinery. Even a strike with a small bit of space debris can make them entirely useless. As opposed to fighter aircraft, which can be damaged slightly and still operate, satellites do not have redundancy when breached, so they are particularly vulnerable. This vulnerability is best shown by the Kessler Syndrome (see figure 4), a hypothetical situation in which successive accidents produce a debris cloud that obstructs future space activities for decades. 43

A Russian weather satellite, Parus, and a retired Chinese rocket had a close call but no collision in October 2020.44 The event indicates how unstable the space environment is and how easily even small miscalculations can have far-reaching consequences in the form of a chain reaction. What if this kind of collision had really happened, sending debris damaging both countries’ vital communication satellites? Tensions may quickly rise as a result of the allegations and finger-pointing that would occur, leading both sides to possibly take retaliatory action. This instance demonstrates the domino effect’s vulnerability by implying that a single attack might destabilize a balanced deterrent environment. In this case, even an accidental collision on a vital satellite may set off a catastrophic series of counterattacks that would destroy infrastructure and pull both countries into a confrontation that might have worldwide consequences. This vulnerability is being exacerbated by the United States’ and China’s expanding space arsenals.

Defense systems and antisatellite capabilities are being developed by China’s newly formed Aerospace Force in April 2024 (following the 2024 dissolution of the Strategic Space Force) and the U.S. Space Force. These systems can result in errors in perception and unintentional escalation because they are meant for quick responses in the event of a conflict.45 For example, China is concerned about the U.S. Boeing X-37B spacecraft’s potential for offensive maneuverability due to its reusable design and concealed cargo. Yet, Beijing has also pursued similar capabilities, launching its own reusable spaceplane in 2020 and 2022, underscoring the action–reaction dynamic of space competition.46 Now consider the following scenario: China misinterprets an X-37B routine mission as a lead-up to an attack. This misconception might result in a preemptive strike on a vital U.S. satellite, setting off a domino effect of counterattacks.

Due to the satellites’ susceptibility to collisions as well as the possibility of errors in perception and calculation, a volatile atmosphere is created where even a minor incident has the potential to escalate into a major war.47 Prioritizing dialogue, openness, and confidence-building measures are crucial as both the United States and China develop space capabilities in order to reduce the possibility of unintentional escalation and maintain peace in the space domain.

Technological determinism and the security dilemma suggest that technological advancements shape military doctrines and the development of capabilities, ultimately shaping the power balance. The pursuit of superiority in space capabilities is a defining factor in the strategic rivalry between these two major powers. The belief that technological progress yields a strategic advantage introduces inherent instabilities, disrupting traditional notions of strategic stability. The pursuit of superior space capabilities challenges the delicate balance necessary to prevent conflict, creating a paradox. The dual nature of space capabilities lies in the fact that the same technologies developed for launch vehicles, satellites, and others can serve both military and civilian purposes, which can also serve both defensive and offensive purposes. This causes a dual-use-dilemma and can escalate tensions, contribute to an arms race, and bring the world near unavoidable conflict.48

The U.S.-China space arms race poses escalation risks due to the competitive environment created by advanced capabilities. This competition increases the risk of miscalculation, misinterpretation, or accidental triggering of conflicts in space. The arms race dynamics raise concerns about the fragility of strategic stability. Each state is deploying cutting-edge technologies, believing it enhances security. However, this competition introduces the risk of unintended escalation.49 The concept of “spillover” in escalation dynamics can be applied to the space domain, extending conflicts beyond their original scope. The fragility of the pursuit of technological supremacy demands sophisticated diplomatic initiatives and mitigation strategies to navigate the complexities of space militarization in an era dominated by technological determinism.

Challenges of Arms Race and Arms Control in Outer Space

The United States’ and China’s burgeoning space competition offers an unprecedented and worrisome phase of arms race instability that the world has rarely seen. Unlike the Cold War, where rivalry was primarily state-driven and nuclear-focused, today’s contest involves dual-use technologies, commercial actors, and contested governance, creating unprecedented risks for escalation. The ramifications of these two countries’ competition for supremacy in the last frontier extend beyond national boundaries, posing important queries regarding the future trajectory of space exploration, collaboration, and security. Arms race instability is the term used to describe the situation in which two or more states’ pursuit of military superiority causes tensions to escalate, trust to erode, and the likelihood of conflict to increase. In a situation like this, each side aims to outcompete the other militarily, which fuels a spiral of armaments accumulation and elevated tensions.50 This dynamic is often described as Thucydides’ Trap; that is, the structural tension between a dominant power and a rising power. Just as Sparta feared the ascent of Athens, the United States today faces strategic anxiety over China’s rapid rise.51 The threat is not only in space weapons accumulation but in the way perceptions of vulnerability can push both sides toward confrontation.

The arms race’s inherent danger and uncertainty, which includes the possibility of miscalculation, misinterpretation, and unintentional escalation are the root cause of the instability. Technological developments, geopolitical rivalry, strategic competition, and the proliferation of space weapons are some of the variables that might aggravate this instability.52 In the end, the instability of the weapons race raises the probability of conflict and jeopardizes global security and stability. The instability of the arms race takes on a new dimension in the context of the U.S.-China space race. Both countries are actively working to develop and employ cutting-edge space-based military capabilities. The collective-action dilemma could result from any action taken by one side that sets off a series of escalations and retaliations in the goal of military control in space.53

Escalating Arms Race and Destabilization of Mutually Assured Destruction in Space

A perilous feedback loop between the United States and China is intensifying as both nations pursue missile defense systems and ASAT weapons, escalating capabilities and tensions. These technologies, even during development, are perceived as threats, prompting both sides to expand their space arsenals. This cycle risks undermining deterrence by enabling preemptive strikes, further destabilizing the strategic balance.

The concept of mutually assured destruction has now extended into the space domain, introducing unprecedented risks.54 Unlike the nuclear mutually assured destruction of the Cold War, space rivalry builds a unique kind of instability. Since satellites are extremely susceptible to preemptive attack, there is always a “use-it-or-lose-it” problem: countries might worry about losing vital communications, navigation, and intel networks at the start of a conflict, which might encourage dangerous escalation. Such an attack would not only blind military forces but also severely disrupt civilian life, highlighting the catastrophic consequences of space warfare. Moreover, the use of ASAT weapons rather than mere deployment exacerbates this instability by creating debris fields that could render critical orbital regions unusable for centuries, effectively locking humanity out of vital space resources.

The dual-use nature of missile defense systems further fuels suspicion. They are not considered “dual-use” technologies in a strict sense because they serve a noncivilian function. However, they often possess a dual capability; the same interceptors designed to target ballistic missiles can also be employed against satellites, as demonstrated in the U.S. 2008 Operation Burnt Frost.55 China perceives U.S. advancements in missile defense as direct threats to its space infrastructure, driving its own counter-space and ASAT developments and accelerating the arms race.

Both nations seek to protect space assets, but their actions escalate the likelihood of a catastrophic conflict. Without strategic restraint, dialogue, and cooperative frameworks, space-based mutually assured destruction threatens to destabilize global security, extending conflicts far beyond Earth’s boundaries and placing humanity’s future in space at grave risk.

The Nature of the Space Arms Race

Compared to conventional terrestrial arms races, the arms race fueled by China’s and the United States’ militarization of space offers a distinct perspective. Space, as opposed to land, sea, or air is a shared environment. Historically, the goal of arms races has frequently been to obtain an advantage in particular areas. But in space, a nation’s actions might inadvertently affect other nations. When a satellite is destroyed while in orbit, debris is released into orbit that might harm or destroy other satellites, making peaceful space exploration impossible for every state.

The primary goal of traditional weaponry is immediate devastation. ASATs and other space weapons, however, add a new level of complication. Not only does destroying a satellite render it inoperable but it also leaves a cloud of debris in the orbit. This debris has the potential to collide with other satellites, starting a chain reaction that might escalate the crisis.56 Furthermore, site inspections and verification of weapon stocks were a common feature in conventional arms races. A certain amount of confidence and verification about arms control are made possible by this transparency. It is far more difficult to monitor and validate space capabilities, though. Dual-use satellites are those that can be used for both military and civilian purposes.

While the Registration Convention (1976) commits states to giving basic details on space objects placed in orbit, it does not mandate revealing their exact purposes or military uses.57 This permits nations to maintain secrecy about the true capabilities of their space programs, making verification and trust more difficult. Finally, disarmament in a conventional arms race refers to the destruction of weapon stockpiles. But the issue is even more complicated in space. Debris removal from orbit is now a very expensive and difficult task. The large debris objects can be removed at exorbitant cost, but tiny untrackable fragments cannot be cleared currently, making complete debris removal totally impossible. It would take a long time and great effort to mitigate the current debris population, even if nations came to an agreement on an arms control treaty.58

Table 1. Differences between conventional and space arms race

|

Features

|

Conventional arms race

|

Space arms race

|

|

Battlefield

|

Land, sea, and air

|

Outer space

|

|

Nature of weapons

|

Tanks, aircraft, missiles, nuclear weapons

|

Satellites, antisatellite weapons, directed-energy systems

|

|

Verification

|

Relatively easier (treaties, inspections)

|

Very difficult (dual-use technologies, covert programs)

|

|

Disarmament

|

Achieved through arms control agreements (e.g., Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty, Intermediate-

Range Nuclear Forces Treaty)

|

Limited success; no binding treaty banning space weapons

|

|

Targeted regions

|

Specific geographic regions (borders, theaters of war)

|

Entire globe (space-based assets affect all regions)

|

Source: courtesy of author, adapted by MCUP.

Arms Control Efforts in Space: A Flawed Framework

Outer space is often viewed as a lawless frontier, yet it is governed by a framework of international laws designed to regulate human activities and prevent conflict. The United Nations Charter, international humanitarian law, and the 1967 Outer Space Treaty collectively provide guidelines for how states should behave in space.59 These include obligations concerning registration, accountability, liability, and contamination prevention. While efforts to prevent space-related conflicts, including the deployment of weapons, have been ongoing, the legal landscape remains underdeveloped and fragmented.

Although the OST is frequently considered a nonarmament treaty, it contains crucial provisions that indirectly support arms control. Drawing from the 1963 Partial Test Ban Treaty, the OST prohibits the placement of nuclear weapons or other weapons of mass destruction in space or on celestial bodies. It mandates that celestial bodies, such as the Moon, be used solely for peaceful purposes. However, the OST does not place extensive restrictions on the use, testing, or deployment of conventional weapons, either in space or directed toward space objects. This legal gap has been a point of concern as states like the United States and China intensify their space-related military capabilities.

Further arms control efforts are seen in the Hague Code of Conduct, which includes transparency measures for space activities, and the Environmental Modification Convention, which prohibits the use of environmental manipulation techniques for military purposes.60 The Anti-Ballistic Missile Treaty, though historically significant, no longer holds relevance after the United States formally withdrew in 2002, citing the need for unconstrained missile defense development.

A significant issue in space governance is the ambiguity surrounding the term peaceful purposes in the OST. This lack of definition is fueling uncertainty, particularly amid the escalating space competition between the United States and China. The OST’s advocacy for space to be used for peaceful purposes without a clear definition creates a gray area, allowing states to engage in dual-use space activities—technologies that can serve both civilian and military objectives.61 This lack of clarity enables countries to develop space programs with potential military applications while still remaining formally adherent to the OST’s peaceful intent, exacerbating geopolitical tensions.

The United States and China, both leading space powers, increasingly engage in activities with dual-use capabilities. China, for instance, has conducted antisatellite tests, such as the 2007 ASAT demonstration, which, although not violating the OST, showcased its ability to deploy space-based weapons. Unlike dual-use technologies like launch vehicles, this ASAT demonstration was explicitly military in design, yet it raised concerns regarding the distinction between compliant dual-use programs and overt weaponization. This event heightened concerns in the United States, which viewed it as a threat to the peaceful use of space. These incidents underscore the mistrust between the two nations, hampering collaboration and fostering a competitive escalation that could lead to an arms race.62

Moreover, the absence of a precise definition of peaceful purposes complicates verification efforts. For example, determining whether a satellite designed for Earth observation is solely for civilian use or could have military applications for targeting becomes a subjective judgment. Without clear criteria, verification of compliance with the OST becomes prone to bias and suspicion. Even overt military systems do not breach the OST, which bans weapons of mass destruction in space, leaving compliance intact but skepticism augmented, thus further straining relations between space-faring nations.

This uncertainty contributes to a climate of secrecy in space programs, with both the United States and China reluctant to disclose comprehensive details of their activities. Because OST does not define peaceful purposes explicitly, disclosing any dual-use capability would cause misinterpretation as militarization, thus this uncertainty incentivizes states to limit transparency. This lack of transparency also makes it difficult to monitor potential weaponization and arms development in space. Consequently, both nations are caught in a security dilemma—each perceives the other’s space program as a potential threat, driving them to enhance their own military space capabilities in response.63 This cycle of suspicion and competition could lead to an avoidable arms race.

To mitigate these tensions and promote stability in space exploration, it is crucial to define peaceful purposes more precisely in international space law. However, major powers like the United States, China, and Russia are unlikely to support such efforts as ambiguity benefits them to expand dual-use capabilities while remaining compliant with OST. However, recognizing this challenge does not devalue the need for dialogue over reducing interpretative gaps, a necessary determinant in long-term stability. A clear definition would help foster transparency, build trust, and ensure a cooperative future for space activities, where security concerns are addressed without resorting to weaponization.

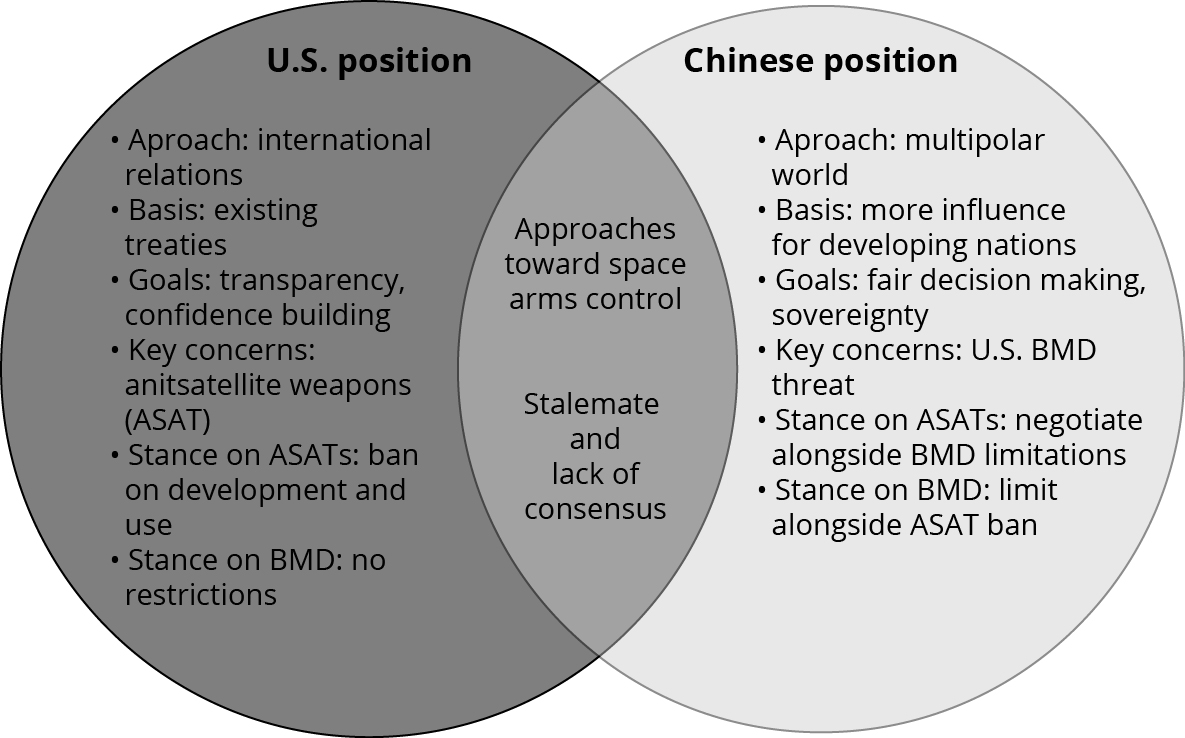

U.S.-China Stalemate on Space Arms Control

The issue of arms control in space has become contentious because of the contrasting ideas put forth by the United States and China regarding future actions beyond Earth’s atmosphere, as the former favors voluntary norms and transparency measures while the latter advocates for legally binding treaties like the proposed Placement of Weapons in Outer Space Treaty (PPWT). The core of this debate stems from basic disparities in approach, with each state advocating for separate concepts and techniques in establishing the rules and norms for effective arms control and managing the arms race in space.64 The United States advocates for a system of international regulations for controlling weapons in space, which is based on established agreements like the Outer Space Treaty.65

This approach highlights the significance of clear interpretations and strict adherence to the principles specified in these treaties. Its aim is to enhance transparency in space activities, thus fostering confidence and minimizing the likelihood of misunderstandings or miscalculations. A key aspect of the U.S. vision is the promotion of international norms that inhibit the creation and utilization of space weaponry. The United States considers space to be a crucial domain for global security and stability. Therefore, it aims to avoid the weaponization of space by employing diplomatic initiatives and engaging in multilateral agreements.

China supports a multipolar system, where developing spacefaring nations have more influence in decision-making processes. They perceive the U.S.-dominated system as favoring established powers to an excessive degree and aim to restore a more equitable allocation of power and influence in the governance of space.66 This vision underpins China’s promotion of the proposed Prevention of the Placement of Weapons in Outer Space Treaty (PPWT) with Russia, which upholds the principle of noninterference in national space programs. For Beijing, the PPWT represents both a counterweight to the United States’ dominance and an appeal to equitable multipolar governance.67 They oppose restrictions on their space endeavors, especially those that are seen as limiting their technological progress or national security concerns. China’s stance demonstrates its intention to assert its sovereignty and autonomy in space.

Figure 5. United States’ and China’s contrasting approaches toward space arms control

Source: courtesy of author, adapted by MCUP.

Moreover, the United States perceives China’s development of antisatellite capabilities as a threat to peaceful space endeavors, since it may potentially expose its satellites to vulnerability. Washington perceives a definite differentiation between ASATs and ballistic missile defense (BMD), advocating for a prohibition on the latter while not impeding the former. China, however, perceives the U.S. emphasis on BMD as hypocritical, as it is concerned that it may potentially be used for aggressive intentions. They argue that any prohibition on ASATs should also include restrictions on sophisticated BMD systems to preserve strategic balance and stability.

The ideological conflict between the United States and China leads to a stalemate in discussions aimed at creating a comprehensive treaty that effectively addresses antisatellite weapons and BMDs effectively.68 Both sides are adamant about not making concessions on crucial matters, as they emphasize that their positions are primarily motivated by concerns regarding national security and strategic objectives. The current deadlock presents substantial obstacles to global endeavors in monitoring and regulating space operations, intensifying conflicts, and accelerating the space arms race. The lack of substantive dialogue and collaboration between the United States and China makes it difficult to achieve consensus on crucial matters concerning space weapons control.

The Verification Dilemma

The escalating U.S.-China competition in space militarization presents strategic gains and drawbacks. While it pushes technological boundaries, it also intensifies verification challenges, complicating arms control efforts and accelerating an unregulated arms race in outer space. Verification in space is inherently difficult due to the unique conditions involved. Ensuring compliance with international agreements is complex, as objects in orbit are thousands of kilometers away, making it challenging to observe and analyze them accurately from ground-based sensors. High-powered telescopes provide limited insight, akin to identifying a car’s function from a blurry photograph, thus complicating assessments of a satellite’s purpose and capabilities.

Further complicating matters, many space technologies have dual-use potential, serving both civilian and military functions. For instance, differentiating a communication satellite from one with reconnaissance capabilities based on orbital parameters alone is challenging, contributing to the verification problem. Effective monitoring would require transparent sharing of information about space programs; however, the United States and China are reluctant to disclose such details. Concerns about compromising their technological edge or exposing vulnerabilities lead both states to withhold critical information, intensifying mutual suspicion.69

This secrecy fosters a worst-case-scenario mindset, fueling an unregulated arms race. China views the U.S. Space Force as a shift toward an aggressive space posture, driving China to increase its military space spending. This cyclical action-reaction dynamic sustains a high-stakes rivalry, marked by both nations preparing for potential conflict scenarios. Without a practical, trustable verification system, accurately assessing each state’s space capabilities remains challenging, and the lack of transparency exacerbates tensions. Consequently, both nations engage in a high-risk strategic game, making it difficult to achieve stability in outer space.

Deterrence Challenges in Space

Space-based deterrence is seriously threatened by the United States’ and China’s competitiveness in space militarization. Both countries are working on building antisatellite and directed energy weaponry to be able to target each other’s satellites. This leads to a more vulnerable situation: A country’s ability to communicate, navigate, and gather intelligence might be severely compromised by an attack on its satellites. Fear of reprisal may not be sufficient to prevent an attack given how dependent both sides are on space infrastructure, particularly if one side thinks it can significantly outmaneuver the other by striking first. The militarization of space risks undermining nuclear deterrence by fostering first-strike incentives, where states may believe space dominance can offset the fear of nuclear reprisals.

Deterrence can be defined as influencing an adversary’s cost-benefit calculations to discourage it from doing something it might otherwise choose to do.70 In practice, deterrence seeks to convince an opponent that taking a prohibited action will result in costs, inability to succeed, or some combination of the two. One can persuade the opponent to decide against acting on the grounds that the likely consequences would exceed the likely rewards. Coercive persuasion takes the form of deterrence. The goal of deterrence tactics is to affect the actions of a voluntary agent, who has the freedom to refuse to comply with the threats or comply with them.71 Controlling tactics are those aimed at preventing the other party from making a decision; they are not deterrent techniques.

Nuclear versus Space Deterrence

The United States’ and China’s space militarization efforts have fundamentally changed the dynamics of successful space deterrence, making the implementation of nuclear deterrent techniques more challenging. It is clear from studying nuclear deterrence that it is not perfect and depends on threats to sway future behavior. If the opponent chooses to disregard the threat, they have no way of knowing how much damage the foe can do or how effective their strikes would be. The opponent makes decisions based on this uncertainty. They assess the possibility of their strike succeeding against the possible costs of ignoring the threat.

Furthermore, two fundamental assumptions that ensure successful nuclear deterrence against one’s opponent are credibility and potency.72 The threat must be genuine and forceful enough to deter an attack. It also needs to be convincing enough to the opponent that it will be carried out. The promise that good behavior will not be punished comes in second. The other player must also be assured that restraint will preserve the status quo, that not attacking will result in no punishment (implicit assurance). Such assurance encourages appropriate behavior. These ideas sound reasonable and promising when applied to land, but they become very difficult when applied to space.

Through the imposition of costs and consequences on potential adversaries, space deterrence aims to dissuade hostile actions against vital space infrastructure. The context in which space-based deterrence functions is essentially different because there are no physical borders, territorial boundaries, or well-defined norms of engagement. Attacks in space might not be as globally devastating as nuclear war.73 The threat is diminished if an attack on a single satellite is not severe enough to justify escalation to a full-scale counterattack.

Moreover, compared to nuclear war, the possible outcomes of targeting space assets are less certain. An enemy finds it more difficult to feel certain that they will not be penalized for a restricted attack because of this ambiguity. A wider variety of threats are covered by space deterrence, such as directed energy weapons, cyberattacks, electronic warfare, and ASAT weapons. Challenges brought about by these advancements include the possibility of escalating conflicts, the militarization of space, and the spread of destructive powers. The table below shows the distinction between space-based and nuclear deterrence.

Table 2. Differences between nuclear and space deterrence

|

Feature

|

Nuclear deterrence

|

Space deterrence

|

|

Environment

|

Earth-bound, terrestrial, and atmospheric domains

|

Outer space, orbital environment

|

|

Threat certainty

|

High—destructive capacity proven and demonstrated

|

Lower—uncertainty due to dual-

use technologies and limited use cases

|

|

Threat credibility and potency

|

Extremely high—assured destruction

|

Ambiguous—depends on technological capability and attribution

|

|

Scope of threats

|

Targeting states, cities, military forces

|

Satellites, communication networks, global infrastructure

|

|

Defense

|

Missile defense limited, mostly deterrence by punishment

|

Hard to defend against; resilience and redundancy preferred

|

|

Limitations

|

Risk of mutual destruction, high political cost

|

Attribution problems, escalation risks, debris creation

|

Source: courtesy of author, adapted by MCUP.

Now, this article will explore the threats that U.S–China space militarization poses to space deterrence, explain why this militarization is increasingly losing its efficacy, and discuss the need for new strategies to counter deterrence instability and escalation risks it generates.

Challenges of Punishment and Denial Deterrent Strategies

The United States and China have developed advanced space-based capabilities, including missile defense systems, ASAT technology, and jamming systems, which render traditional deterrence strategies, such as “an eye for an eye,” increasingly ineffective. The United States’ heavy reliance on space infrastructure for military operations, communications, and intelligence makes it particularly vulnerable, as retaliatory actions against Chinese satellites may not adequately deter attacks. U.S. losses in space would likely be more detrimental for its adversaries’ deterrent strategies, further complicating deterrence as Washington might interpret such attacks as escalatory and respond forcefully.74 In contrast, China’s growing but less dependent space capabilities reduce its risk exposure, making threats of retaliation less impactful and escalation more likely.

Proportional retaliation, such as targeting China’s ASAT launch facilities, risks rapid escalation. Escalating to airstrikes on urban centers would be disproportionate and could provoke broader conflict.75 Effective deterrence requires credible threats balanced by proportionality; disproportionate actions, such as bombing cities for satellite losses, lack credibility and undermine strategic stability. This creates a pressing challenge for both nations to establish an equilibrium in their evolving deterrence strategies.

Denial-based deterrence, emphasizing satellite resilience, is also fraught with challenges. Satellites’ inherent exposure in space limits passive defenses like shielding, which offers modest protection and often relies on secrecy. Active defenses, such as lasers or directed energy weapons, present technical and economic constraints, including increased launch costs and limited maneuverability due to fuel constraints.76 Keplerian mechanics and high orbital speeds (around 17,000 mph in low Earth orbit) further restrict satellites’ ability to evade calculated attacks.77 These dynamics make it difficult for deterrence strategies relying solely on maneuverability or active defenses to succeed.

Asymmetric perceptions of risk and reward complicate deterrence. China may calculate that limited strikes on key U.S. satellites could yield strategic advantages with minimal retaliation, challenging the United States to innovate deterrence strategies that address these vulnerabilities while maintaining strategic stability.

Considering these challenges, a comprehensive space defense strategy is necessary. This approach should explore various defensive solutions, including advancements in space situational awareness (SSA) to enhance detection and tracking of threats in orbit. SSA capabilities are critical in providing early warning and potentially neutralizing threats before they cause damage. A combination of enhanced SSA, innovative defensive measures, and credible and proportional deterrent strategies can help secure space assets and maintain stability.78 By adopting such a strategy, the United States and China, as leading space powers, can mitigate risks of escalation and preserve stability and safety in an increasingly contested domain.

Table 3. Differences between active and passive defenses

|

Features

|

Passive defense

|

Active defense

|

|

Definition

|

Defensive measures that aim to minimize damage and exposure without engaging threats directly

|

Defensive measures that actively detect, respond to, and neutralize threats

|

|

Advantages

|

- Cost-effective in the long run

- Low operational complexity

- Reduces exposure to risks

|

- Real-time threat response

- Greater adaptability

- Can neutralize or deter

attackers

|

|

Limitations

|

- Cannot eliminate threats

- Static and predictable

- Limited adaptability

|

- Expensive and resource-

intensive

- Risk of escalation

- Requires skilled personnel

|

|

Examples

|

- Firewalls

- Encryption

- Intrusion prevention systems

- Access controls

|

- Intrusion detection systems

- Honeypots

- Threat hunting

- Automated response systems

|

Source: courtesy of author, adapted by MCUP.

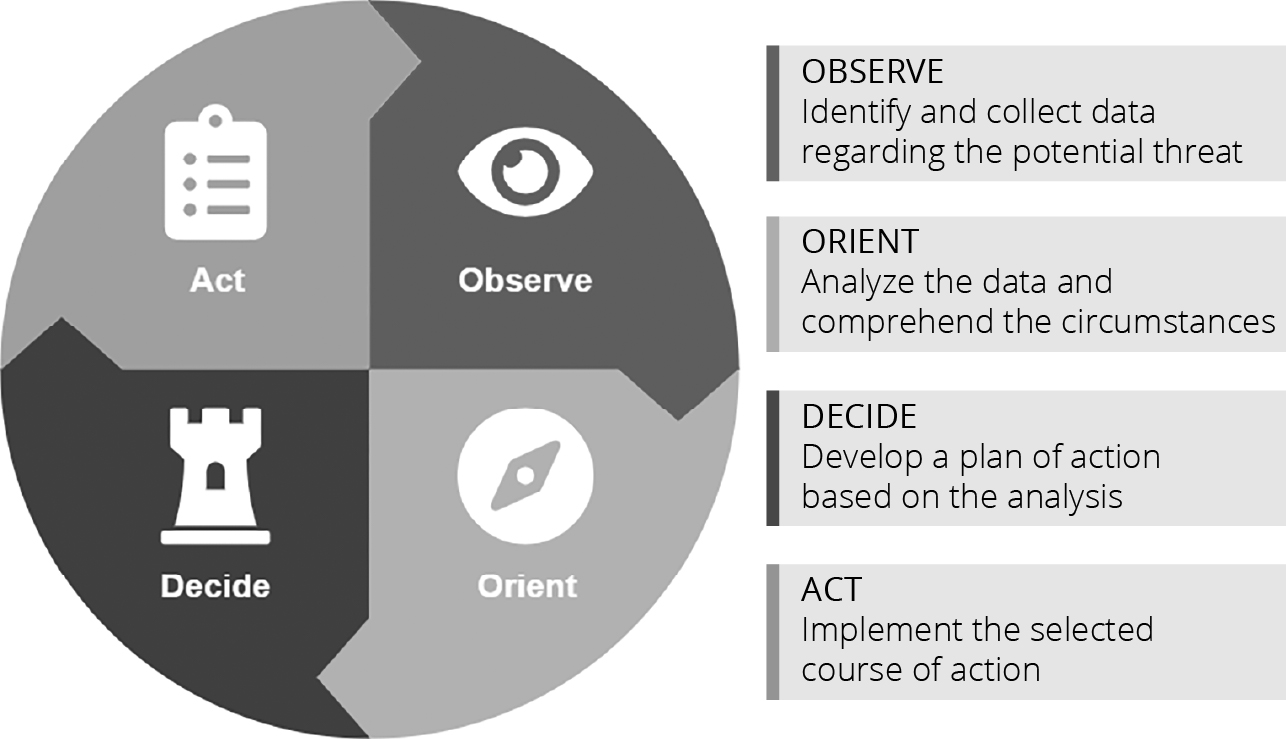

OODA Loop Gap in Space

Space warfare occurs with an accelerated pace, as both China and the United States possess the capability to launch unexpected assaults on each other’s satellites using kinetic ASAT weapons. Defense in this domain necessitates the efficient execution of the OODA loop—a decision-making framework comprising four critical stages: observe, orient, decide, and act.79 This framework underscores the importance of swift and informed responses to mitigate threats, yet its application in outer space faces significant challenges.80

Figure 6. OODA loop of decision making and course of action

Source: adapted from Col John R. Boyd, A Discourse on Winning and Losing, ed. Grant T. Hammond (Maxwell, AFB: Air University Press, 1987).

The observe phase involves identifying and collecting data on potential threats. In outer space, this is hindered by the difficulty of monitoring diminutive, maneuverable objects like ASAT weapons. Limited sensor coverage, particularly for high-orbit systems such as geosynchronous satellites, creates significant detection gaps. Attackers can exploit these gaps to launch undetected assaults, compromising the ability to respond effectively.81 The orient phase, which requires analyzing the data to understand the nature and severity of threats, is similarly constrained by delays in data processing and limited sensor capabilities. This results in incomplete or outdated situational awareness, further complicating timely decision making.

During the decide phase, commanders must formulate actionable plans based on available data. However, the pace of space war and intricacies of the space environment dictates severe time limitations, usually compelling decision makers to make decisions with limited information. Even once a decision is made, the act phase—like maneuvering satellites or activating countermeasures—is limited by orbital mechanics, fuel restrictions, and technological lag, making timely inception problematic.

The challenges inherent in the OODA loop highlight the urgent need for advancements in sensor technology, data processing, and real-time decision-making frameworks. Without these enhancements, the vulnerabilities in each phase of the OODA loop leaves space assets exposed to operational failures and augmented susceptibility to hostile interference or accidental collisions. As technological determinism suggests, advancements in offensive space capabilities continue to outpace defensive measures, challenging existing norms and treaties like the Outer Space Treaty. The dynamics underscore the paradox of technological progress, where the pursuit of strategic advantage undermines stability.

Strategic stability—comprising crisis management, arms control, and deterrence—is increasingly strained by U.S.-China competition. The proliferation of counterspace capabilities heightens the risk of crisis escalation through miscalculations and retaliatory spirals. Unlike traditional arms races, space militarization introduces unique instability, as ASAT weapons and missile defense systems enable preemptive strikes, while attribution challenges further render deterrence ineffective. Furthermore, ambiguities surrounding the definition of peaceful purposes and verification challenges exacerbate the complexity of arms control efforts.

The stakes in this cosmic brinkmanship are immense. A single misstep could result in catastrophic conflict with global ramifications. To avert such outcomes, global cooperation is imperative. Robust arms control agreements, enhanced transparency, and prioritization of peaceful initiatives are essential to preserve strategic stability. Navigating this volatile domain with foresight and intelligence is critical to securing a sustainable and conflict-free future in outer space.

Recommendations for Space Security

The intensifying space militarization by the United States and China poses significant challenges to global strategic stability, necessitating a multifaceted and collaborative approach. Addressing these challenges requires the integration of technological advancements, the formulation of comprehensive strategies, and robust global cooperation. By adopting targeted measures, both nations can promote security, stability, and the sustainable use of outer space, ensuring that its vast potential benefits all.

The following recommendations outline critical policies and strategies to foster peaceful coexistence in space, mitigate conflict risks, and enhance mutual security. These measures emphasize improving crisis and deterrence stability, advancing arms control mechanisms, and building a balanced framework for long-term collaboration in the space domain.

Enhance Crisis Stability through International Dialogues

• Foster regular communication channels between the United States and China to clarify intent and prevent miscalculations during crises.

• Establish bilateral and multilateral forums to discuss space security concerns, drawing precedents like the Artemis Accords and support with memorandums of understanding and agreements for real-time information exchange during emergencies.

• Encourage the use of regional platforms, such as the Asia-Pacific Regional Space Agency Forum, to address space security in localized contexts.

Promote Transparency and Space Situational Awareness (SSA)

• Develop joint SSA initiatives to improve tracking, cataloging, and monitoring of space objects, thereby reducing the risk of misinterpretation.

• Share satellite launch notifications, orbital data, and operational details to build mutual trust and reduce the likelihood of accidental escalations.

• Expand data-sharing efforts with independent experts and international organizations to enhance oversight and accountability.

Commit to Restraint in the Use of Kinetic ASAT Weapons

• Advocate for a “no-first-use” pledge by the United States and China for kinetic ASAT systems, initially between the United States and China as leading space powers, but with a goal of expanding to other states like Russia and India to prevent space debris and orbital congestion.

• Leverage diplomatic pressure and advanced nonkinetic capabilities to encourage responsible behavior and reduce reliance on destructive ASAT systems.

• Work toward a multilateral framework under United Nations supervision to establish a global ban on ASAT testing and deployment.

Table 4. Proposed space weapons categories to make arms control efforts effective and more practical

|

Space weapon category

|

Description

|

Example

|

Regulation focus

|

|

High-threat weapons

|

Widespread or lasting harm

|

Lasers to destroy satellites, nuclear weapons

|

Stringent regulations or prohibitions

|

|

Weapons of moderate threat

|

Disable or destroy a single satellite

|

Electronic jammers, lower-power lasers

|

Restrictions on deployment or testing

|

|

Low-threat weapons

|

Limited effectiveness, minor disruption

|

Basic ASAT capabilities, short-range jammers

|

Transparency and notification requirements

|

Source: courtesy of author, adapted by MCUP.

Define and Regulate Space Weapons

• Develop internationally accepted definitions for space weapons based on their design and intended use, focusing on their potential to cause harm in space.

• Categorize weapons into high-, moderate-, and low-threat levels, with high-threat weapons (e.g., destructive lasers and nuclear arms) subject to strict bans, and low-threat systems requiring transparency measures.

• Introduce protocols to regulate dual-use technologies, ensuring their peaceful application while mitigating security risks.

Strengthen Verification Mechanisms

• Design robust verification frameworks that combine satellite monitoring, open-source intelligence, and independent expert evaluations to ensure compliance with space agreements.

• Address national security concerns by introducing phased transparency agreements, beginning with nonsensitive data sharing and evolving into comprehensive verification practices.

• Explore technological solutions for real-time monitoring, such as advanced SSA systems, to provide early warnings of potential violations.

Foster Multilateral Cooperation on Space Governance

• Engage with global and regional organizations like the UN Committee on Peaceful Uses of Outer Space to address the governance gaps in space, focusing on collaborative efforts for arms control and debris management.

• Develop shared norms and protocols for peaceful space activities, including mechanisms to resolve disputes and ensure accountability like the China and Russia sponsored International Lunar Research Station that promote an alternative governance vision.

• Encourage Joint missions and projects between the United States and China to establish trust and demonstrate commitment to shared goals in space exploration and utilization.

Conclusion

The militarization of space by the United States and China reflects a complex interplay of geopolitical ambitions, technological advancements, and shifting national objectives. Initially spurred by Cold War tensions and perceived Soviet threats, the United States established space dominance, investing heavily in military space technologies. China, driven by military, prestige, and economic factors, has since emerged as a formidable space power, challenging U.S. supremacy. This U.S.-China rivalry now extends beyond exploration, focusing on control over strategic space resources and the military advantages space offers.

Technological determinism and the security dilemma illustrate this competition’s impact on strategic stability, as advancements fuel mutual suspicion. Space is perceived as a zero-sum game, where the line between defensive and offensive capabilities is blurred, fostering a cycle of militarization. This escalation threatens the three pillars of stability—crisis management, arms control, and deterrence. The deployment of ASAT weapons and missile defense systems risks crisis escalation and undermines deterrence, as space-based weapons enable potentially destructive, preemptive strikes. The lack of clarity on peaceful purposes and challenges in verifying space activities further complicate arms control efforts. This rivalry thus disrupts the balance of power, increasing the likelihood of miscalculation and unintended conflict, ultimately threatening peace in the space domain.