https://doi.org/10.21140/mcuj.20251602008

PRINTER FRIENDLY PDF

EPUB

AUDIOBOOK

Abstract: Artificial intelligence (AI) is already reshaping work methodologies, but future disruptions will inevitably extend further, fundamentally influencing how we conceptualize and understand reality. The scale and pace of this disruption will accelerate significantly with the integration of AI agents and multiagent systems. Traditional linear military planning processes, which depend solely on human cognition, have repeatedly proven inadequate in confronting the complexities of contemporary battlespaces. This article explores the potential impacts of AI on operational art and highlights opportunities for military organizations to successfully reimagine operational cognition through collaborative frameworks that seamlessly integrate human and AI capabilities. The findings suggest multiple transformative impacts on existing linear cognitive paradigms and propose enhanced human-machine collaboration mental models.

Keywords: operational art, multiparadigm design, multiagent system, warfare

The world is currently facing a technological disruption, as artificial intelligence is fundamentally reshaping not only our methods of work but also the ways we conceptualize and comprehend reality. This article examines the potential impacts of AI on operational art and discusses opportunities for military organizations to successfully reconceptualize operational cognition through syndicates that seamlessly integrate human-AI collaboration. The traditional linear military planning process—reliant exclusively on human cognition—has repeatedly proven insufficient when confronted by the complexities inherent to contemporary battlespaces. Information saturation, rapidly unfolding events, and ambiguous operational contexts consistently challenge the effectiveness of reductionist decision-making paradigms. Planners frequently resort to oversimplifying complex realities to achieve clarity, despite complexity being an inherent characteristic of the modern operational environment. While humans simplify reality due to cognitive limitations, artificial intelligence simplifies due to computational efficiency and goal-driven optimization. This fundamental divergence in cognitive approaches underscores the necessity of an integrated human-AI paradigm shift in military planning processes.

One of the most disruptive advancements in artificial intelligence is AI agent technology.1 AI agents integrate automation and generative AI, enabling greater adaptability and emergent decision making. Within military planning processes, this leap in technology offers new pathways for dynamic operational design, allowing planners to retain cognitive depth while optimizing execution. Operational planning in the military domain has traditionally relied on hierarchical command structures, doctrinal principles, and predefined scenarios.2 However, the growing complexity of the modern battlespace, the accelerating tempo of decision making, and the increasing adaptability of adversaries challenge these conventional approaches, which remain constrained by human cognitive limitations.3 Human decision making is inherently susceptible to heuristic biases, cognitive overload, and errors stemming from incomplete situational awareness, all of which can contribute to strategic failures.4 In this evolving operational landscape, the integration of AI agents and multiagent systems (MAS) into planning of operations or campaigns represents a radical paradigm shift, one that has the potential to redefine the foundational principles of military planning and decision making. In this article, planning is seen in a broad manner, encompassing processes throughout the whole conflict continuum and extending to the planning during phases of execution.

Military planning can and should be comprehended as inherently nonstatic, as temporal and spatial rigidity cannot be sustained in warfare. Future planning will therefore emphasize dynamism, emergent organization, and self-organization, where time, space, and force composition happen in tandem with AI agents.5 This transition redefines classical military planning principles—systematic logic and frame-by-frame snapshot of warfare—by shifting their meaning in relation to space, time, and strategic actors. Objectives no longer have to be fixed endpoints but rather fluid constructs that emerge within the continuous evolution of the planning syndicate. Rather than being merely a challenge, uncertainty becomes a fundamental premise of operational design. Critical decision-making convergence points arise where AI agents and human planners converge into a continuously evolving decision-making rhizome.6 This transformation moves military planning beyond rigid linearity and traditional group decision-making constraints toward adaptive, self-regulating syndicates, leveraging AI’s cognitive and analytical capabilities. AI agents cease to be mere reactive tools and instead become active participants in operational design—shaping strategy rather than merely executing predefined tasks.

Winning in peer-to-peer conflict, or even against a numerically superior adversary, has historically relied on superior cognition to generate sudden and unforeseen disruption.7 From a Finnish perspective, it is evident that the country’s survival during the 1939 Winter War would not have been feasible had static trench warfare been favored over tactical mobility, counteroffensives, and leveraging the local battlespace conditions for engagements. Surprise has consistently been a transient phenomenon—a fleeting window of opportunity sustained solely through tempo, defined as the dynamic interplay of speed and unpredictability. This, in turn, necessitates decentralized command structures, an acute awareness of risk, and cognitively demanding military judgment.8 The fundamental principles of operational-level warfare have remained largely unchanged. Contemporary conflicts further substantiate this reality: the Russo-Ukrainian War has exemplified disruptive applications of unconventional operational thinking, incorporating a synergistic combination of disinformation campaigns, land-based maneuvers, and the denial of maritime dominance through unmanned surface vessels. Similarly, the annexation of Crimea, executed by unmarked military personnel colloquially referred to as “little green men,” parallels historical instances of strategic deception, such as the Trojan horse or the airborne assault on Belgium’s Fort Eben-Emael—operations that profoundly redefined prevailing conceptions of what is operationally feasible in warfare.

This article contends that the rapid advancements in AI technology have the potential to elevate operational art to unprecedented levels of unconventional thinking. While traditional maneuver warfare theories have predominantly centered on the physical domains, emerging technologies are increasingly dismantling these boundaries, enabling a more expansive and fluid conceptualization of conflict. This article argues that the core principles of warfare—surprise and speed—will remain integral; however, the operational maneuvers of the near future will progressively transcend conventional domains, continuously redefining feasibility and broadening the spectrum of possible military actions.

This article analyzes how AI multiagent systems reframe operational art and disrupt planning processes in warfare. This posits that military operational thinking and decision making will face a paradigmatic shift, catalyzed by the emergence of AI agents and multiagent systems as defining constructs in future operational environments. Artificial intelligence is no longer an abstract theoretical construct but a tangible and operationally integrated force multiplier, as evidenced already by the ubiquitous deployment of generative AI architectures, such as ChatGPT. The AI-driven paradigms analyzed in this study—AI agents and MAS—represent an advanced evolutionary leap in computational autonomy, characterized by disruptive potential that redefines the foundational principles of operational art and strategic command structures. Gordon Moore’s 1965 prediction of exponential technological progress, based on the doubling of transistor density, laid the foundation for decades of innovation. Today, the advent of AI agents and MAS systems accelerates this trajectory, granting agile and adaptive organizations a decisive strategic advantage. In contrast, entities that remain reliant on rigid, bureaucratic planning structures and cumbersome processes risk obsolescence. Within military organizations, human-centered decision making may become a limiting factor if legacy planning paradigms continue to be maintained without adaptation to the evolving technological landscape.

The Need for a Paradigm Shift in Military Convention

Ben Zweibelson has argued that artificial intelligence challenges the foundational philosophical pillars of operational art.9 The integration of AI agents can help shift military planning away from deterministic, Newtonian-style linearity and toward a model that embraces complexity, emergence, and dynamism. This transition necessitates not only technological investment but also a fundamental cultural and paradigmatic shift within military organizations. The military profession must evolve beyond institutional inertia and actively integrate complexity-driven operational methodologies to leverage AI-human collaboration. Linear and hierarchical planning processes are no longer sufficient to win against an opponent also aiming for relative advantage through leveraging rapidly emerging dilemmas. This will necessitate a paradigm shift in military doctrine toward more flexible and self-organizing decision making to keep up with the rate of change possible.

The excessive reliance on bureaucratic control mechanisms and doctrinal standardization within military organizations presents a structural impediment to innovative cognition and the evolution of adaptive decision-making frameworks.10 This institutional rigidity fosters a competency trap, wherein organizations become self-referentially entrenched in established methodologies, misperceiving them as universally optimal, thus impairing their capacity for epistemic adaptation and strategic responsiveness in dynamic operational contexts.11 Hierarchical decision making and static planning may result in a loss of operational flexibility, allowing an adaptive enemy to outmaneuver overly rigid operational thinking. The operations in Afghanistan and Iraq exemplified how rapidly changing battlefield conditions rendered traditional planning models ineffective, leading to strategic miscalculations.12

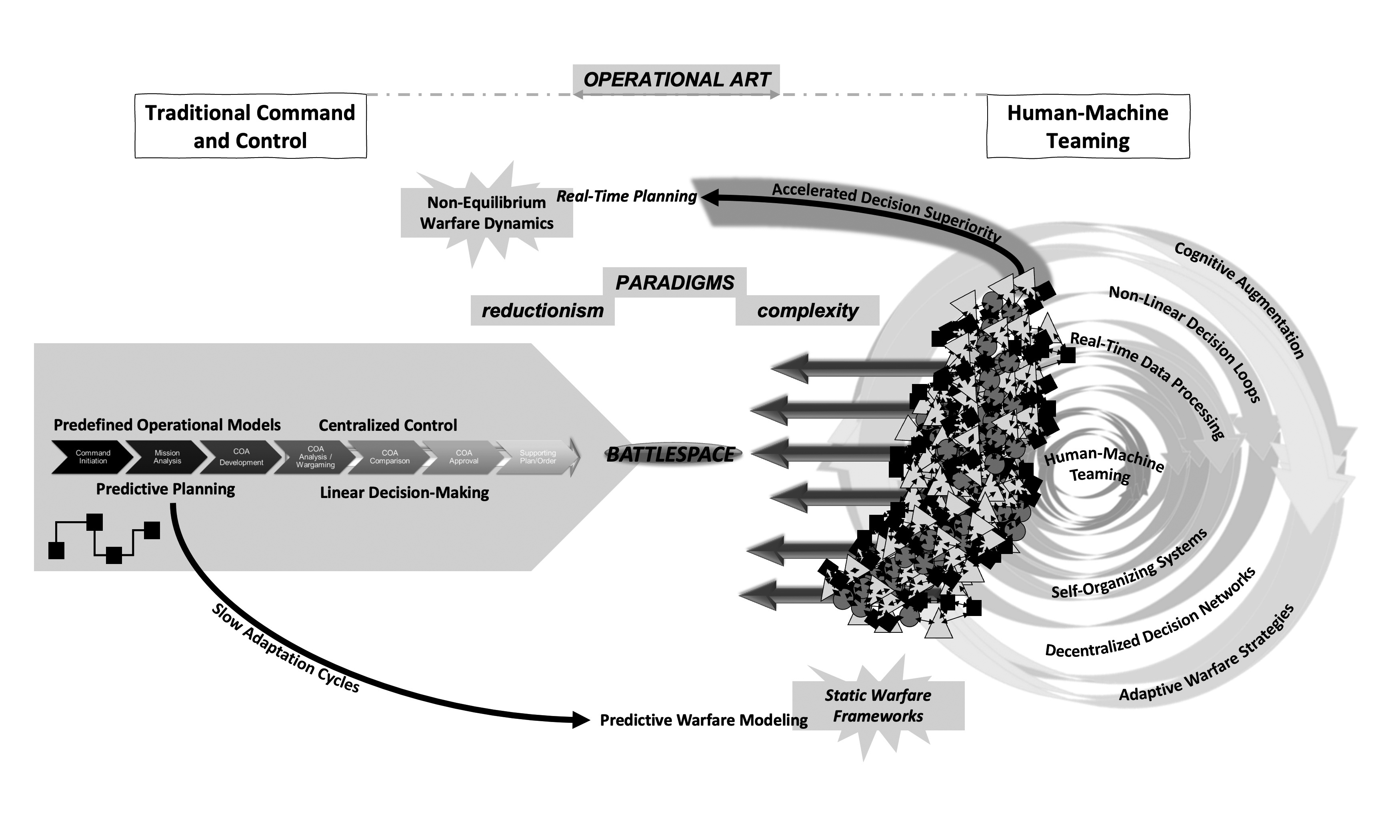

Figure 1 illustrates the tension between linear and complex operational art, where two distinct paradigms can intersect on the future battlefield. The purpose of this depiction is not to argue for the superiority of either approach but to analyze the reality of warfare and military planning from two different perspectives. The traditional linear planning mental model is rooted in reductionist thinking, where complex phenomena are deconstructed into discrete, manageable components. This article, however, posits that AI applications introduce a disruptive dimension to military planning, enabling novel approaches to addressing threats within a dynamic and multifaceted operational environment. In particular, the multiparadigmatic nature of the contemporary battlespace, along with the inherently complex and dynamic character of operational reality, necessitates the continuous evolution of military planning and operational art. The development of AI should be perceived as an opportunity rather than a threat. It is essential to recognize that AI is not merely another “instrument” in the historical progression of military technology, gradually enhancing warfare through incremental advancements, nor just a decision-support system; instead, it can establish a novel operational environment where strategic choices, situational awareness, and operational thought evolve in constant interaction with multidimensional data flows. Thus, AI does not simply provide more efficient means of responding to changes in warfare; rather, it can alter the very conceptualization of warfare itself by generating new situational developments, enabling emergent strategies and decentralizing operational decision making in ways that challenge traditional command structures and linear planning paradigms. In this sense, AI is not merely a solution to the challenges of modern warfare—it constitutes an entirely new paradigm for understanding, organizing, and executing military operations.

Figure 1. The tension between complexity and linearity in multiparadigmatic battlefield planning

Source: courtesy of the author, adapted by MCUP.

We can first analyze whether AI agents could calculate, model, or simulate the complexity of warfare to a level of rationalist and mechanistic paradigm. This is plausible, as AI systems can filter, structure, and distill vast, multilayered information flows—often surpassing human cognitive capacity—into clear and actionable decision alternatives.13 However, warfare and even a conflict is always a reciprocal hostile activity. The degree to which AI influences warfare complexity depends on its design and operational application. If AI is used primarily for data reduction and simplification, it risks reestablishing a deterministic, mechanistic approach to military planning, limiting adaptability in emergent, nonlinear conflict environments. Conversely, when AI is integrated within an iterative, emergent, and complexity-embracing operational framework, it can enhance adaptive decision making, deepen situational awareness, and facilitate dynamic actions. Ultimately, the human role remains decisive—military professionals determine whether AI functions merely as an information-reduction tool or as a catalyst for embracing complexity and fostering emergent strategic thinking.

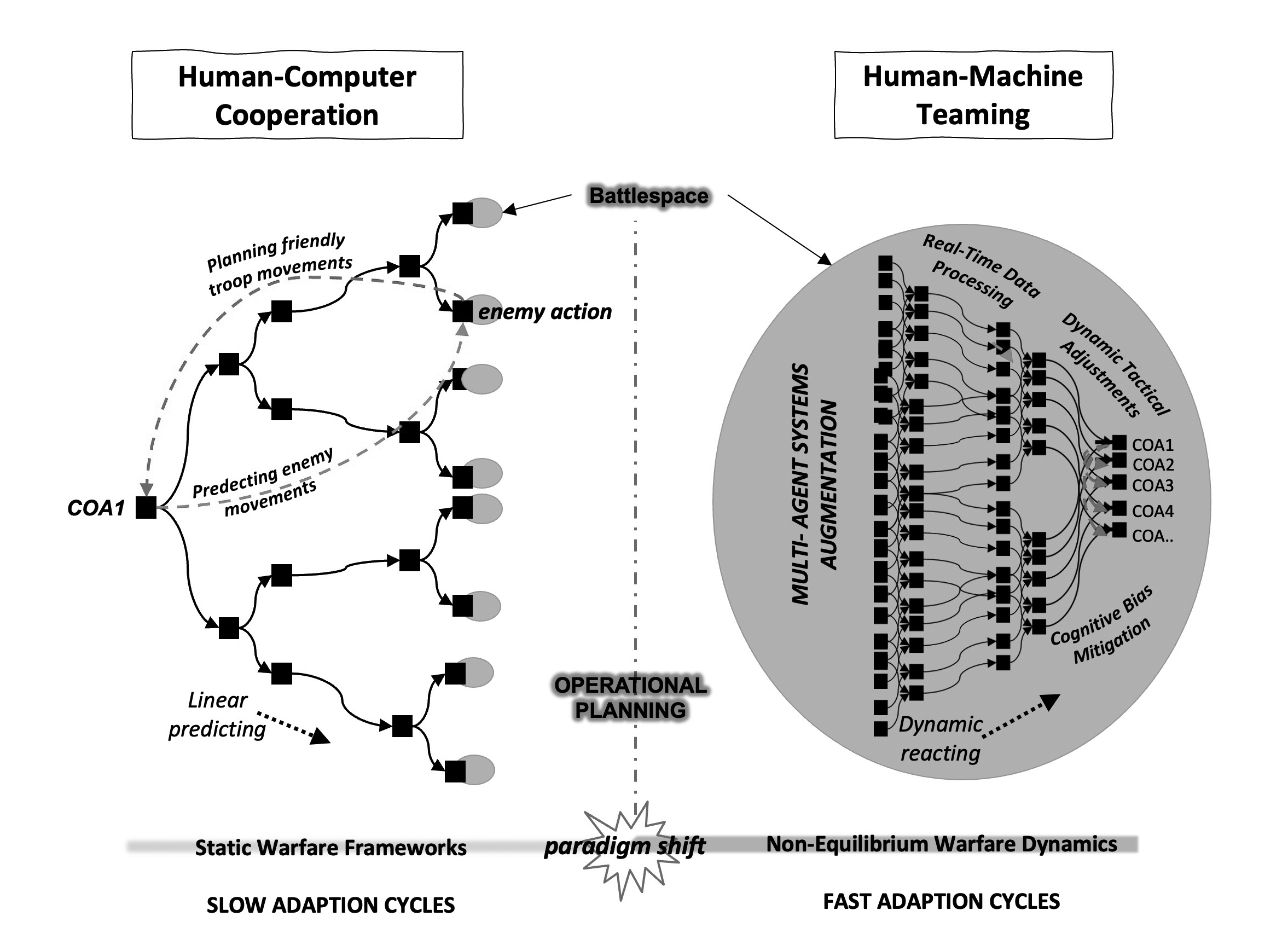

Figure 2 illustrates a paradigm shift that will be driven by multiagent systems. Real-time operational planning becomes feasible through data automation, multiagent network intelligence, and enhanced human-machine integration. In traditional, static operational planning, enemy actions must be predicted well in advance, as dynamic responses during combat situations are severely limited. Historically, predictions relied heavily on extensive manual data management, typically handled via cumbersome spreadsheets emphasizing data entry over cognitive teaming. MAS fundamentally transforms this process by integrating information with unprecedented precision and significantly mitigating cognitive biases inherent in human-centric planning. Rather than eliminating the need for predictive activities, MAS refines and improves prediction accuracy through artificial intelligence. Automated management of information overload, combined with an emergent and dynamic human-machine planning interaction, ensures continuous adaptation. Multiagent coordination further supports decision making, enabling tactical adjustments in real-time combat scenarios, provided sufficient authorization. The introduction of MAS radically compresses both spatial and temporal dimensions within the battlespace. Consequently, operational planning undergoes a profound paradigm shift, adopting a multiparadigmatic approach centered around dynamic human-machine teaming. This transformation is crucial for addressing the inherent unpredictability and instability of future warfare environments.

Figure 2. Static versus nonequilibrium warfare

Source: courtesy of the author, adapted by MCUP.

Historically, the center of gravity has been perceived as the enemy’s critical focal point, the disruption of which would lead to the collapse of the entire system.14 This perspective is rooted in mechanistic thinking, where the adversary is conceptualized as a hierarchical and predictable system. Operational planning has also been based on the assumption that targeting strategic nodes—such as command centers, logistical networks, and key capabilities—is sufficient to achieve the objectives of warfare.15 This model has proven effective in traditional conflicts and during battles with superior forces where warfare has been clearly delineated and structured. However, in asymmetric and hybrid operations, the adversary can be a decentralized and adaptive network in which focal points continuously shift.16 In preparing the abilities to fight near peer enemies, the static and predefined center of gravity no longer provides a viable strategic framework, as modern military operations require continuous situational awareness updates and adaptive decision-making mechanisms. In contemporary warfare, center of gravity should be understood as an evolving and context-dependent phenomenon, emerging in real-time as a result of various factors and environmental changes. Instead of focusing on striking a fixed center of gravity, operational planning can leverage multiagent systems and AI to map how an enemy’s critical structures evolve dynamically.

Current Research on Human Collaboration with Multiagent Systems

AI research has transitioned toward a paradigm that fuses adaptability with structured planning, reactivity with cognitive modeling, and emergence with self-organization, creating an increasingly seamless and autonomous decision-making framework.17 This shift represents a departure from deterministic, rule-based systems of the 1950s, which were limited in scope and lacked situational awareness or contextual learning. Today, AI agents have evolved into sophisticated, autonomous systems leveraging deep learning, reinforcement learning, and large language models (LLMs) to address complex, multilayered challenges.18 Unlike their predecessors, these AI agents are not merely reactive tools; they now engage in higher-order decision making, problem-solving, and dynamic environmental interaction.19 Their integration into both civilian and military applications is redefining intelligence analysis, operational planning, and command structures, enhancing speed, adaptability, and strategic foresight. Looking ahead, AI agents are poised to transition from digital environments to real-world physical operations, particularly in robotics and autonomous systems where they will navigate, assess, and act independently within dynamic, unpredictable terrains.20 This evolution requires advanced sensor fusion, real-time data processing, and context-sensitive decision making, ensuring AI systems adapt fluidly to changing operational conditions. As AI’s role extends beyond passive computation into active execution, its impact on warfighting, logistics, and battlefield autonomy will become increasingly foundational rather than supplementary.

The defining characteristic of AI agents is their ability to operate autonomously while interacting with their environment. Unlike traditional software systems that follow static, predefined rules, AI agents sense, interpret, and adapt to new situations in real time. They leverage sensors to collect stimuli—such as sound, text, and images—and process this data to support decision making. This capability distinguishes AI agents from conventional software, which lacks the flexibility to adjust to evolving conditions.21 AI agents can be broadly defined as autonomous entities that function independently yet engage dynamically with other agents and their surroundings. Their core attributes include autonomy, social intelligence, reactivity, and proactivity.22

The future of AI agents is closely tied to their increasing autonomy, adaptive learning, and self-organizing capabilities, which are crucial for the evolution of more complex multiagent systems.23 The key distinction between AI agents and MAS lies in the complexity and scalability of their application domains. While an individual AI agent can efficiently perform a specific task, MAS enables decentralized decision making, real-time adaptability, and emergent problem-solving, making them particularly valuable in highly dynamic and uncertain environments.24 MAS consists of autonomous agents that can either collaborate or compete to achieve shared objectives. One of their primary advantages is their ability to decompose complex problems into smaller, manageable subproblems, allowing for parallel computation and real-time decision optimization.25 MAS systems are uniquely suited for environments requiring both distributed intelligence and dynamic adaptability. By leveraging collective intelligence, swarm behavior, and coordinated learning, MAS can generate synergistic effects that surpass the capabilities of individual agents. This allows them to enhance system-wide efficiency, optimize resources, and increase resilience against disruptions.26

Drone swarms are a concrete example of applying multiagent system theory to dynamic combat environments, and their significance in autonomous warfare is growing.27 Swarming behavior refers to the real-time, coordinated operation of multiple autonomous agents acting as a unified whole. Each agent operates independently but synchronizes its decision making with others without centralized control, enabling faster responses compared to traditional systems.28 With localized situational awareness and rule-based decision making, the system remains both adaptive and resilient under rapidly changing conditions. Intelligent communication within the swarm allows for real-time data sharing, enabling sensor drones to detect threats or targets and direct armed units accordingly.29 Drone autonomy enables coordinated collaboration without continuous human intervention, and cooperative methods developed on this basis support effective swarm behavior across various operational environments.30 Swarm technologies are expected to play a critical role in future armed forces seeking to outpace adversaries in decision-making and operational tempo within complex and fast-evolving combat scenarios.31 The United States’ latest planned Boeing F-47 sixth generation stealth fighter jet exemplifies the integration of swarm intelligence and AI-based agent technology into a single, advanced system.32

MAS systems elevate the operational capabilities of AI agents to a new level. Their decentralized architecture enables the efficient and flexible resolution of complex, large-scale problems, making them highly adaptable to dynamic environments.33 Moreover, MAS systems leverage synergistic effects, where the collective intelligence of individual agents leads to emergent behaviors and solutions that surpass the sum of their individual capabilities.34 According to recent publications, AI agents are transforming military planning and execution in the following 10 key areas.35

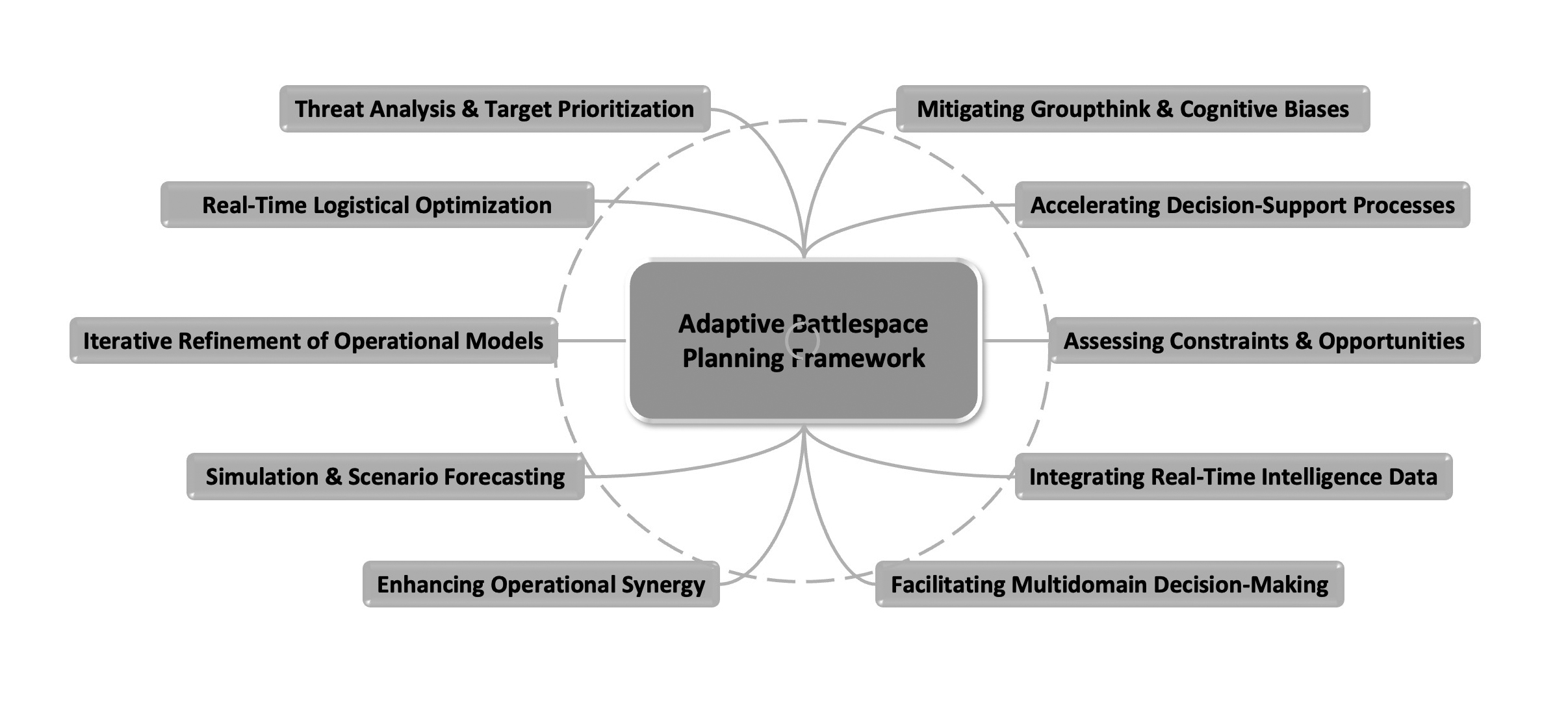

The benefits offered by AI agents and multi-agent systems extend broadly across military planning and operational activities. These technologies can enhance command processes, optimize resource utilization, and support decision making in complex and rapidly evolving environments. Most importantly, AI agents can introduce noninstitutionalized novel alternatives, generating solutions and decisions that are developed interactively—learning from past operations and adversary actions to refine and design future actions. Looking ahead, the advancement of AI agents and MAS systems will unlock new opportunities to merge human and AI capabilities, paving the way for more efficient, adaptive, and innovative operational models. This evolution will inevitably reshape operational art and influence the organization of planning syndicates, driving military strategy toward greater agility and intelligence-driven execution.

Figure 3. Adaptive battlepace planning framework.

Source: based on ideas from Thom Hawkins, “We Are All Agents: The Future of Human-AI Collaboration,” Modern War Institute, 28 August 2024; and J. Caballero Testón, “The Role of Automated Planning in Battle Management Systems for Military Tactics,” Expert Systems with Applications 297 (2025), https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eswa.2025.129259.

At this point it seems already clear that AI agents represent a paradigm-disrupting technology, not a fleeting trend, and their influence extends across tactical, operational, and strategic levels.36 Organizations increasingly integrate AI agents as virtual team members, leveraging them for knowledge management, workflow coordination, and complex operational execution.37 As the technology evolves, AI agents transition from simple assistants to autonomous entities capable of decision making, environmental adaptation, and achieving strategic objectives with minimal human oversight.38 This transformation signals a fundamental shift in both technological and operational paradigms, with far-reaching implications for planning effectiveness, strategic agility, and emergent decision architectures. Military organizations must embrace the dissolution of rigid, deterministic models and move toward fluid, adaptive, and AI-enhanced frameworks that align with the realities of modern conflict.

The primary challenge of this technological transformation is not merely the performance capabilities of AI agents but their acceptance within military organizations as integral components of operational planning and decision making. Sarvash Sawant et al. highlight three critical concerns: the transparency of AI-driven decision making, the formal delineation of its role within operational structures, and the trust that military personnel place in autonomous systems’ evaluative capacities.39 Excessive AI autonomy risks obscuring accountability, increasing strategic uncertainty, and diminishing critical human judgment, particularly if AI agents operate beyond the comprehension and oversight of human commanders.40 Conversely, well-integrated and applied AI agents could enable a novel paradigm of autonomous operational planning, characterized by unprecedented speed, adaptability, and initiative in decision-making. Consequently, the radical adoption of AI-driven military planning necessitates a fundamental redefinition of operational thinking—one that deeply accounts for the capabilities and limitations of these technologies and systematically reevaluates AI agents’ roles within military operations at a foundational level.

As has become clear, MAS consists of autonomous agents, which can be either software- or hardware-based components working collectively to achieve a common objective.41 The core attributes of these systems include:

• Decentralized decision making: MAS agents can operate autonomously and make decisions without reliance on a centralized command structure.

• Scalability: The system can adapt to operations of varying scales and types.

• Adaptability: MAS can respond to real-time changes in the environment and anticipate emerging threats.

Agents within MAS can be homogeneous (identical in function and capability) or heterogeneous (specialized with different roles and abilities), allowing for efficient execution of complex tasks.42 While AI offers significant advantages in analytical and administrative tasks, its role as a leader or in fostering social cohesion remains challenging. Military leadership requires not only decision making but also human empathy, social intelligence, and intuitive understanding of complex political and cultural factors. These limitations define the extent to which AI can fully replace human decision making in critical military situations.

AI agents can already offer a decisive advantage in military operations by automating repetitive and high-volume tasks, allowing human operators to focus on complex, strategic, and creative decision making. Beyond task automation, AI agents and MAS can process real-time data streams, detect emerging patterns, and execute high-speed strategic decisions with unmatched precision.43 This capability is particularly critical in military operations, where fast data-driven decisions can directly influence mission success. AI agents enhance operational efficiency, reduce cognitive overload on human planners, and provide real-time adaptability in rapidly evolving combat environments.

Paradigmatic Disruptions in Warfare: Lessons of Unconventional Thinking

Future warfare scenarios are likely to become increasingly complex, faster-paced, multiparadigmatic, and conceptually more challenging to comprehend. This is particularly true in conflicts involving near-peer adversaries with highly trained officer corps, who may demonstrate minimal regard for institutionalized rituals or legal constraints on fair warfare. Engaging a near-peer adversary—whether through direct confrontation or proxy conflicts—will inevitably incorporate familiar elements of past military engagements, including established methods, strategies, and operational practices, and these can be augmented by progressively faster adaptation cycles and accelerated deployment of emerging technologies. However, such developments primarily reflect increased efficiency in applying existing methodologies rather than a fundamental shift in the nature of warfare. While adaptation and incremental innovations remain crucial, they are not the primary focus of this article. Beyond simply accelerating existing approaches, strategic advantage may also emerge through entirely novel methods and unconventional means.44 Additionally, the relatively unexplored operational domains of space and cyberspace introduce further layers of disruption. To contextualize this shift, the concept of paradigmatic surprise is introduced into military theory, illustrated through historical case studies, and linked to the planning process.

Paradigmatic surprise is a cognitive effect imposed on an adversary through actions that cannot be comprehended using existing mental models and conceptual frameworks. In military contexts, surprise is traditionally understood in terms of unexpected force posturing, troop numbers, or unforeseen movement vectors. However, in such cases, the advantage is still gained within the established and mutually understood parameters of warfare. In contrast, paradigmatic surprises arise from actions that fundamentally disrupt the prevailing paradigm, necessitating entirely new indicators to assess their impact. In the realm of technological innovation, radical advancements are often distinguished by whether their capabilities are measured using entirely new performance indicators.45

As previously suggested, future warfare may challenge the Newtonian deterministic paradigm that underpins current ontological and epistemological approaches to warfighting and operational planning. This evolution places increasing demands on military organizations to cultivate innovation that transcends institutional rigidity. With AI-enhanced collective cognition, paradigmatic surprises may not only become a recurrent feature of modern warfare but also an essential element of contingency planning. Although history offers numerous instances of paradigmatic surprise, these events were often incomprehensible at the time they occurred—only later were they fully understood in hindsight. When first encountered, their very nature obscured whether an operation was actively unfolding, often delaying an effective response until it was rendered futile. Even though these surprises seemed unpredictable in the moment, the activities were nevertheless devised within the planning groups of one antagonist—the surpriser’s. As such, even MAS-augmented and broad contingency planning might not have prevented the activities, but it could have been extremely helpful in recognizing the disruptive situation as unfolding aggression and in designing timely countermeasures to the new reality. Therefore, the following examples are not intended to predict specific future actions but rather to illustrate how war paradigms have been disrupted in the past and potential superior cognitive capabilities can conceptualize the paradigms again also.

Superiority through Surprise Instead of Mass

The German victory in France in 1940, often characterized by the term blitzkrieg, represented an unprecedented development in modern warfare. The assault through the Ardennes began on 10 May 1940.46 At the time, France was considered the militarily superior power and had spent the previous two decades preparing for a potential conflict.47 Nevertheless, Germany devised a military solution that bypassed the previously assumed strengths of conventional warfare, achieving a decisive and unexpected success. Several key factors contributed to the German victory and the element of surprise. The concentration of highly mobile panzer divisions, led by bold and aggressive commanders, spearheaded the offensive in a manner without historical precedent.48 According to Richard Shuster, Germany’s success can be attributed to the innovative employment of armored forces, maneuver warfare tactics that disrupted the conventional notion of a linear front, and a novel conceptualization of military command structures.49 These strategic innovations rendered obsolete the earlier emphasis on numerical superiority and massed formations as the primary determinants of military effectiveness.

During the Falkland Islands War (1982), Argentina achieved operational surprise but failed to effectively respond to Britain’s strategic adaptation, leading to the ultimate failure of its campaign. Similarly, during the Yom Kippur War (1973), Syria and Egypt executed a well-coordinated, large-scale offensive against Israel, yet Israel’s ability to improvise and rapidly adjust its defensive strategy enabled it to shift the course of the war in its favor. These cases illustrate that surprise alone does not secure strategic success. The decisive factor is not the initial disruption of an opponent’s expectations, but rather the capacity to exploit that moment of shock and sustain a dynamic response to the evolving battlespace. For mechanistic organizations, this underscores the necessity of integrating innovation-seeking behaviors into their structural and cultural dynamics. Adaptation cannot be a reactive measure; it must be an inherent feature of military planning and execution, ensuring forces remain fluid, responsive, and attuned to emergent complexities in warfare.50

Separatists or Joint-Level Special Operation Forces of Russia

During the early hours of 27 February 2014, special operations forces from the Russian Special Operations Command (SOC) seized the Crimean parliament building.51 These SOC troops, described as the special operations unit “most directly at the hands of the political leadership,” had only recently been officially established in March 2013 and were modeled after the United States Delta Force and the United Kingdom Special Air Service.52 The operation diverged significantly from prevailing Western special operations doctrines, particularly those emphasizing military direct action. The soldiers did not wear identifying insignia, as required under international law, and the Russian government denied any involvement. Instead, the operatives were publicly portrayed as local civilians. The operation demonstrated a high degree of coherence across all levels—from tactical execution to strategic communications and political-strategic maneuvering—ultimately achieving its objectives without direct military confrontation.

The operation was executed at the tactical level through covert means and conducted without direct combat. While it did not constitute a disruptive innovation in special operations at the tactical level, its impact at the operational level created a paradigmatic surprise. It challenged the binary distinction between war and peace, contradicted the Western emphasis on the right to peaceful protest, and did not fit conventional definitions of terrorism. The inability to conceptualize or even name the situation led to a disruption in recognizing it as a military operation altogether. Although carried out at the tactical level, this swift and decisive action undermined the cognitive frameworks of the time, achieving a fait accompli before Ukraine could respond effectively. By the time Ukrainian authorities could react, Russian second-echelon forces were already positioned.53 The tactical maneuver rapidly escalated into strategic-level consequences. More than two weeks later, Western media outlets continued to refer to the Russian operatives as “armed gunmen” and “separatists.”54 Within just 19 days, a rigged referendum had already taken place, leading to the formal annexation of Crimea by Russia. Throughout this period, special operations forces were still publicly labeled as “pro-Russian armed forces,” and major Western news sources, such as BBC, framed the event as the Crimean parliament having “formally applied to join Russia.”55 This cognitive and political disruption persisted among Western governments, as they struggled to categorize an event that defied existing paradigms of warfighting. While this operation redefined the contemporary understanding of military action, the future of warfare may introduce even greater disruptions, as operations increasingly evolve into multidomain engagements that transcend traditional conceptual boundaries.

The historical case study of Russia’s operation in Crimea provides valuable insights into contemporary cognitive deficiencies in military planning processes. First, the operation disrupted existing mental models used to conceptualize military situations, thereby significantly delaying the sensemaking phase, which constitutes the first and most critical step of any military planning process. Whether this phase involves intelligence preparation of the operational environment—through mapping, factor analysis sheets, or other methodologies—effective sensemaking requires the appropriate cognitive tools to identify key challenges and fully comprehend the problem.56 The process of naming plays a fundamental role in framing a given situation.57 It is conceivable that the disruptive cognitive capabilities of AI-driven multiagent systems could have enhanced defense planning by recognizing the potential risk of a modern-day Trojan horse operation before its execution. Moreover, the ability to challenge institutional rigidity in planning teams, as well as the prevailing ontological and epistemological frameworks of warfare, could have provided a cognitive advantage in understanding the unfolding situation and, consequently, formulating effective responses. It is also possible that a viable countermeasure already exists but remains unrecognized due to cognitive constraints imposed by preexisting mental models.

The conventional temporal construct in military planning is misleading, as it relies on static and spatial assumptions that fragment operational reality into predefined phases. This reductionist approach can restrict adaptability in responding to dynamic and uncertain situations, particularly when planning is anchored in preestablished scenarios that fail to account for the emergent and adaptive nature of modern warfare. The Crimean operation provides a compelling example of how Russia integrated hybrid warfare elements—disinformation, rapid special forces deployment, and political uncertainty—to manufacture strategic surprise. This represents a cognitive bias toward surprise, where the disruption was not merely a result of tactical execution but rather a deliberate exploitation of information saturation and deception. The objective was to distort and disrupt adversarial decision making, which was predisposed to mechanistic, symmetrical warfare constructs.

Toward Novel Military Thought: The Synergy of Human and Multiagent Systems

Within operational art, planning syndicates will become even more pivotal in achieving complex and dynamic objectives and in surpassing more commander-driven approaches. Recent advancements have expanded the concept of teamwork and decision making to incorporate human-machine collaboration.58 AI agents can integrate advanced artificial intelligence technologies, such as machine learning, to enhance their adaptability, efficiency, and decision-making capabilities.59 This transformation is particularly valuable in military planning, where adaptive, high-speed solutions are essential to address complex, multidomain operational challenges. AI agents extend the role of generative AI beyond traditional support functions—rather than merely assisting human operators, they can act as independent agents, collaborating or even autonomously executing tasks when required. AI-driven agents operate 24/7, processing vast streams of battlefield intelligence, command center data, and real-time communications. This continuous, high-speed data synthesis improves situational awareness, optimizes strategic responses, and reduces human cognitive burden, reinforcing faster and more precise decision cycles in modern warfare.

The cognitive demands placed on human operators in human-AI collaboration have already undergone a significant transformation. While certain cognitive burdens, such as information gathering, can now be delegated to generative AI, critical tasks—including information verification and cross-referencing—remain intrinsically human responsibilities. This shift has also introduced new cognitive challenges associated with response integration, wherein AI-generated information must be critically assessed for contextual relevance, alignment with intended objectives, and suitability for the target audience. Consequently, the human role is evolving from that of an executor to that of an overseer.60 Nathan J. McNeese et al. examined human-AI teams in emergency response scenarios and found that teams integrating AI significantly outperformed all-human teams in shared situational awareness and task efficiency, despite a decline in perceived shared cognition.61 In the context of military planning teams, research has highlighted not only the critical role of internal information-sharing but also the necessity of external coupling—leveraging expertise beyond the immediate team. Effective decision making in novel and dynamic operational environments depends on the ability to access multidisciplinary insights.62 If AI-generated knowledge can provide reliable and timely access to diverse fields of expertise, AI agents may fundamentally disrupt traditional external networking paradigms.

Humans have a natural tendency to oversimplify complex and ambiguous phenomena, perceiving them as more structured and controlled than they truly are. This cognitive bias limits critical discourse and prevents deeper exploration of alternative perspectives, thereby constraining the recognition, comprehension, and learning of new insights.63 During the operational planning process, AI agents serve as force multipliers by augmenting human expertise and enhancing the capacity to manage complexity. They can assist in strategic planning by autonomously distributing tasks, integrating external intelligence sources, and continuously refining their own performance. Their role becomes particularly vital during wargaming and scenario analysis, where AI-driven simulations can rapidly generate and assess thousands of alternative courses of action in real time. While human planners rely on cognitive reasoning and experience, AI agents provide a systematic, data-driven approach that significantly accelerates decision cycles and increases strategic foresight. Iterative feedback loops and machine learning mechanisms further refine AI agents’ accuracy, adaptability, and responsiveness, making them indispensable tools in modern multidomain operations. Their ability to process vast intelligence streams, optimize dynamic decision making, and function autonomously cements their role as essential components of next-generation operational planning frameworks.64

AI agents are no longer passive decision-support tools; they actively engage in the planning process as predictors, critics, advisors, and even leaders. This evolution demands the development of highly adaptive, resilient, and efficient AI agents, capable of navigating complex operational environments, augmenting decision making, anticipating situational shifts, and aligning actions toward shared strategic objectives.65 This human-AI synergy fosters a nonlinear, emergent approach to decision making, enabling enhanced adaptability in responding to the intricate, rapidly evolving challenges of modern warfare. The integration of decision-making rhizomes—decentralized, non-hierarchical, continuously evolving decision structures—transforms how military organizations perceive and react to complexity.

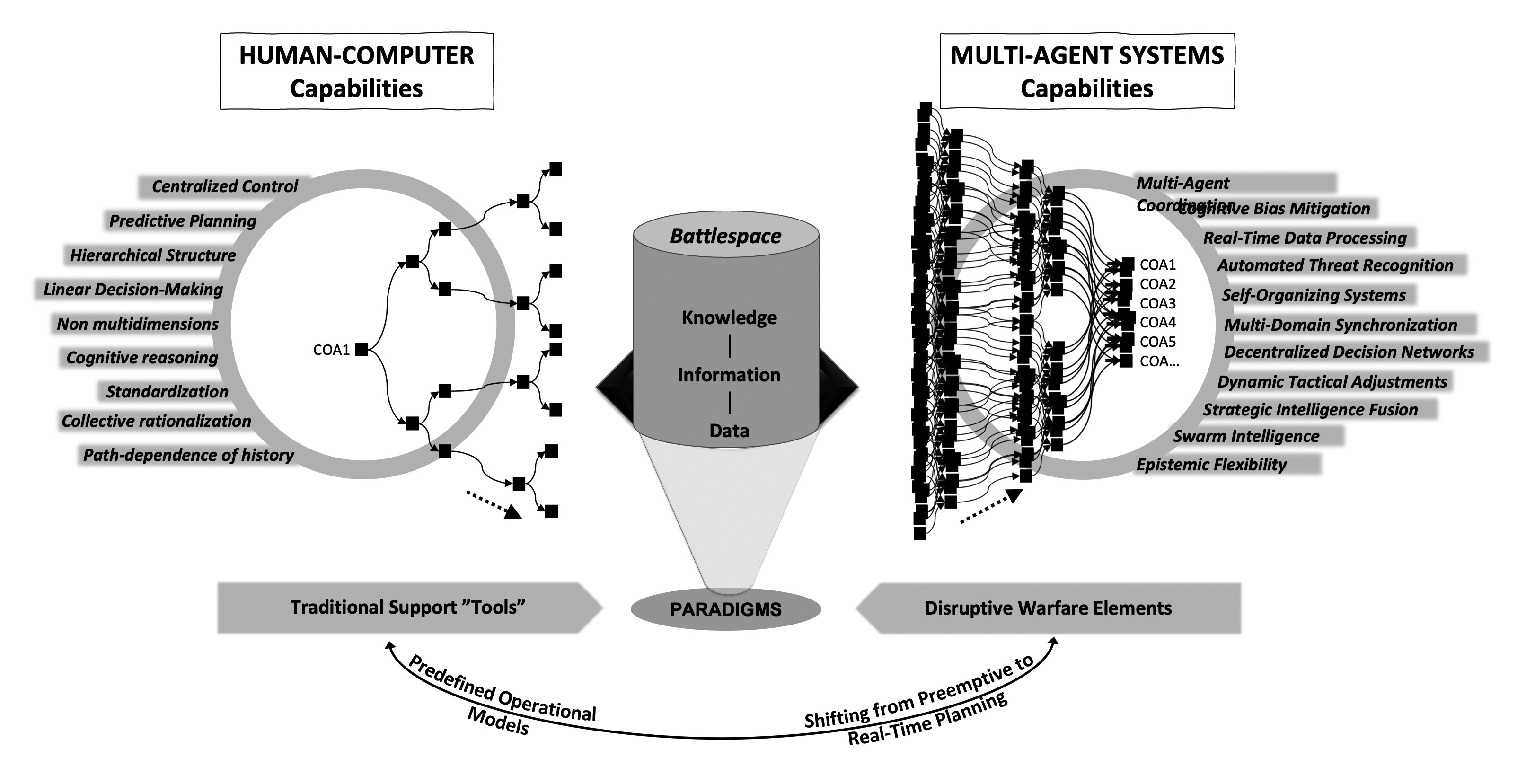

Figure 4 presents key terms illustrating the significance and role of MAS in the context of operational planning. AI-driven autonomous agents are not merely auxiliary tools; rather, they can function as independent entities within operational planning, capable of generating, optimizing, and executing complex operational plans in real time. According to Michael Mayer, integrating AI with advanced sensors and autonomous systems enables a self-organizing observe-orient-decide-act (OODA), allowing tasks to be executed without direct human oversight.66 This advancement could drive a shift toward decision-centric warfare, where AI agents not only support but fundamentally reframe military decision-making processes by continuously generating decision points and courses of action. With AI-driven operational planning, the traditional hierarchical and prescripted planning model can be replaced by a dynamic, decentralized, and self-learning system in which AI agents autonomously analyze situational awareness, devise adaptive strategies, and coordinate force deployments in real time.67

Figure 4. From static frameworks to emergent design

Source: courtesy of the author, adapted by MCUP.

Table 1. The impact of the AI multiagent systems

|

Zweibelson and Paparone’s critiques of contemporary challenges

|

“Perspectives on Future Operational Art: The Impact of AI MAS”

|

|

1. The challenge of the Newtonian paradigm: from determinism to complexity

The Newtonian, linear way of thinking emphasizes causality and predictability.

|

AI multiagent systems’ iterative and emergent analyses enhance our understanding of complex operations while deconstructing traditional deterministic warfare models. This shift challenges established planning paradigms and necessitates more adaptive, dynamic mechanisms.

|

|

2. The ontology and epistemology of warfare

Traditional concepts like centers of gravity and operational levels are outdated and poorly suited for addressing modern complex threats.

|

AI multiagent systems’ adaptive knowledge models promote paradigm diversity, surpassing traditional linear and hierarchical frameworks.

|

|

3. Human-machine collaboration: a new division of roles

The relationship between humans and machines can no longer be based on a commander-tool model.

|

AI multiagent systems transform thinking into a collaborative process, where machines generate innovative solutions and continuous learning becomes integral to strategic adaptation.

|

|

4. Complexity and emergence in military planning

Dynamic and complex models challenge conventional mathematical frameworks, providing alternative perspectives on fluid, nonlinear, and multidimensional operational dynamics.

|

AI multiagent systems integrate multidisciplinary data sources and dynamically anticipate changes, enabling continuous and adaptive emergent planning.

|

|

5. Institutional rigidity versus innovation

Institutional inertia perpetuates outdated models, stifling innovative approaches and preventing the assimilation of new paradigms into operational thinking.

|

AI multiagent systems can disrupt institutionalized thinking by providing alternative, objective perspectives. However, their impact depends on an organization’s flexibility and willingness to adapt.

|

Source: based on Ben Zweibelson, “Breaking the Newtonian Fetish: Conceptualizing War Differently for a Changing World,” Journal of Advanced Military Studies 15, no. 1 (Spring 2024), https://doi.org/10.21140/mcuj.20231501009; Christopher R. Paparone, “How We Fight: A Critical Exploration of U.S. Military Doctrine,” Organization 24, no. 4 (2017): 516–33, https://doi.org/10.1177/1350508417693853; Thom Hawkins, “We Are All Agents: The Future of Human-AI Collaboration,” Modern War Institute, 28 August 2024; and J. Caballero Testón, ”The Role of Automated Planning in Battle Management Systems for Military Tactics,” Expert Systems with Applications 297 (2025), https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eswa.2025.129259

Redefined Operational Understanding

The People’s Liberation Army (PLA) perceives the future of warfare not as a continuation of traditional strategic logics but as a contest over the ability to define and reframe the evolving rules of conflict engagement. By integrating artificial intelligence into its strategic calculus, the PLA seeks to anticipate, shape, and dictate the trajectory of military scenarios before adversarial forces can cognitively and structurally adapt to the altered battlespace.68 However, the assumption that AI can singularly supersede human decision-making complexities ignores a fundamental reality of warfare—its emergent and complex-adaptive nature. Historical military paradigms have repeatedly overestimated technological determinism, neglecting the intricate web of strategic, economic, and sociopolitical entanglements that continuously redefine operational realities. Warfare is not a closed system governed by fixed inputs and predictable outcomes; rather it is an open, recursive, and self-organizing phenomenon, where innovation and adaptation coalesce in unpredictable ways. For instance, the blitzkrieg concept has often been mythologized as a linear and mechanistic breakthrough, yet modern historiography suggests that the Wehrmacht’s operational artistry was far more nuanced than merely a doctrine of speed and armored maneuver.69 Similarly, contemporary AI-driven decision architectures including multi-agent systems risk becoming cognitively entrapped within rigid epistemological boundaries that fail to capture the ever-evolving nature of military conflict. The critical question, then, is not whether AI can provide superior decision making, but whether it can transcend the human tendency toward rigid doctrinal framing and enable new heuristics for navigating complexity and uncertainty. Could AI, rather than merely optimizing existing military methodologies, act as a catalyst for post-linear operational design thinking, wherein strategy is conceived as an iterative, multidimensional, and nonstatic process rather than a preordained sequence of actions?

In the technological domain, surprise can create new opportunities, particularly when combined with the ability to exploit a rapidly evolving military environment. China’s AI strategy appears to place considerable expectations on a single technological solution, a historically common yet often flawed approach.70 However, it is crucial to recognize that historical patterns do not repeat in a deterministic manner, and assuming linear progression in military development can be misleading.

The advancement of artificial intelligence and autonomous systems may constitute a military revolution akin to how the atomic bomb diverged from the tank during World War II. The tank enhanced and accelerated traditional warfare, reinforcing mobility and firepower but leaving the fundamental principles of land warfare intact. In contrast, the atomic bomb completely transformed the nature of war, shifting the focus from operational engagements to strategic deterrence and redefining conflict as an existential threat. Similarly, AI and autonomous systems may not merely optimize current military practices but could fundamentally alter the paradigm of warfare, redefining the role of the human on the battlefield and challenging traditional conceptions of conflict.

Discussion

Throughout the history of warfare, technological advancements—such as aircraft, tanks, and siege towers—have been pivotal in securing operational superiority and shaping the evolution of operational art.71 Traditionally, military tools have been defined by human control and innovation, often leading to rapid and radical shifts in warfare (e.g., the disruptive impact of drones in Ukraine). However, the rise of artificial intelligence fundamentally disrupts this paradigm, as it reconfigures the role of military tools—transforming them from passive, human-operated instruments into partially autonomous agents capable of decision making and dynamic action alongside human operators. This transformation is not merely a technological leap, but a philosophical shift in how military assets are conceptualized and employed. Warfare may no longer be solely an instrumental activity dictated by human actors; instead, it could evolve into an emergent and self-directed process, where AI and other advanced technologies influence—or even establish—operational objectives autonomously.

While Jeremiah Hurley and Morgan Greene emphasize the importance of data-driven thinking, history demonstrates that technological breakthroughs alone have rarely determined the outcomes of wars.72 For instance, in the twentieth century, mechanized warfare did not single-handedly resolve conflicts; it was most effective when combined with flexible operational planning and the ability to adapt to adversary movements. Similarly, AI and MAS offer unprecedented decision-making capabilities and operational agility, yet they also introduce new vulnerabilities, such as cyber threats, reduced transparency in decision making, and potential dependencies on data analytics, which may be susceptible to manipulation or misinformation. Consequently, the traditional typology of military technology is not merely evolving—strategic decision making must adapt to an increasingly complex and dynamic operational environment.

The operational environment can change rapidly—and historically, an inability to adapt to shifting conditions has resulted in severe losses.73 The adoption of multiagent systems is a pivotal component in the digitalization of military decision making and the AI revolution. MAS enhances operational capabilities by increasing decision-making speed, optimizing information utilization, enabling decentralized operations, and fostering proactive planning. When effectively implemented, MAS facilitates near-real-time command and control, making it indispensable in contemporary warfare. MAS represents a shift toward a decentralized decision-making approach.

Table 2. From the MAS dilemma to propositions

|

Dilemma

|

AI multiagent system ability

|

Proposition

|

|

Causal reductionism is an inadequate epistemology for explaining a complex world

|

The ability to continuously discover new ways of representing data, whether visual, narrative, or literary.

|

AI as an interpreter between diverse participants, bridging epistemological stances.

|

|

The enemy deliberately creates complexity,

conceals intentions, diverts attention, and remains an active actor.

|

The ability to continuously evaluate vast data sets and construct representations, models, and visualizations free from institutionalized cognitive biases.

|

AI continuously generates enemy courses of action (COAs), ranging from the probable to the improbable.

|

|

Multidomain environments increasingly require a multiparadigmatic approach.

|

The ability to assume diverse roles within a syndicate, incorporating multiple perspectives and integrating expertise from various fields.

|

AI assuming multiple planner roles, introducing new frameworks and perspectives (human-to-AI ratio: 4:2 or 3:3).

|

|

Cognitively demanding processes have proven too complex to effectively teach and comprehend for a broad audience.

|

The ability to engage with theoretical knowledge in metaphysics, develop processes, and design methodologies and methods.

|

AI as a facilitator within the syndicate/planning team, assisting the leader in selecting contextually appropriate processes and methods.

|

Source: courtesy of the author, adapted by MCUP.

Operational planning cannot be confined to a singular or static paradigm; instead, it must leverage multiple, interwoven theoretical frameworks that dynamically interact with one another. Traditional operational constructs, such as the North Atlantic Treaty Organization’s (NATO) long-term NATO Defense Planning Process or short-term Joint Targeting Process, rest on predefined structures and assumptions about the static nature of warfare. However, the modern operational environment fundamentally disrupts these linear approaches, demanding a more fluid, emergent design perspective. Following Bergson’s philosophy, the concept of duration resists segmentation into discrete phases, as creativity and temporal continuity unfold as an indivisible, evolving process.74 Warfare, therefore, is not a linear sequence of events but a dynamic, heterogeneous process that does not conform to a predetermined structure.75 This means that military operations are not isolated stages but continuous, adaptive phenomena that blend into one another. Recognizing and exploiting this continuity is essential for contemporary warfare. War is not an ordered system, nor can it be prescripted through static models—its shape and content emerge through a complex interplay of adversarial actions, environmental shifts, and technological capabilities. As Ben Zweibelson argues, war should be understood as an emergent, multilayered, and dynamically evolving phenomenon, in which conventional static planning models are increasingly insufficient.76 Instead, adaptive, multiparadigmatic approaches provide the necessary epistemic agility to navigate the inherent unpredictability of modern conflict and prevent decision-making entrapment within outdated doctrinal constraints.

Multiagent systems introduce novel capabilities into operational planning, enabling an accelerated decision-making cycle and a deeper, iteratively evolving situational awareness. MAS transcend the cognitive boundaries of traditional military decision making by integrating real-time analytics, multidimensional data processing, and the ability to dynamically adapt to complex scenarios without the constraints of hierarchical command structures. MAS not only enhances operational planning efficiency but fundamentally alters its core principles, shifting the focus from deterministic, predictive models to real-time, emergent adaptation and context-driven decision making. This transition fosters multiparadigmatic adaptability, where planning is no longer constrained by predefined heuristic models but is instead rooted in self-organizing and adaptive situational analysis. Future military strategies can no longer rely on conventional hierarchical and linear frameworks; rather, they must integrate networked, decentralized, and continuously evolving mechanisms that enable flexible and iterative responses to an increasingly volatile operational environment. This marks a paradigm shift, wherein warfare ceases to be a unidirectional and prescripted process and instead emerges as a self-reflective, self-adaptive system—one in which operational planning and battlefield events coalesce into an interconnected, continuously evolving ecosystem.

Traditional rigid command structures can create bottlenecks in the effective utilization of new technologies and advanced decision-making frameworks.77 Thus, the integration of multiagent systems is not merely a technological advancement but fundamentally an organizational challenge—one that demands resilience and epistemic agility—the ability to rapidly adapt to fluid operational conditions and leverage new paradigms effectively. MAS can provide alternative analytical frameworks for decision makers, acting as a mechanism that detects strategic blind spots that human cognition might overlook. This fosters multiparadigmatic decision making, where multiple scenarios and interpretations can be evaluated simultaneously, mitigating the risk of cognitive entrenchment within preordained assumptions.

Endnotes

1. “What Is a Multiagent System?,” IBM, accessed 25 September 2025; and “Magentic-One: A Generalist Multi-Agent System for Solving Complex Tasks,” Microsoft, 17 July 2025.

2. Ben Zweibelson, “Breaking the Newtonian Fetish: Conceptualizing War Differently for a Changing World,” Journal of Advanced Military Studies 15, no. 1 (Spring 2024), https://doi.org/10.21140/mcuj.20231501009.

3. Christopher R. Paparone and George E. Reed, “The Reflective Military Practitioner: How Military Professionals Think in Action,” Journal of Military Learning no. 88 (October 2017).

4. Daniel Kahneman, Thinking, Fast and Slow (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2011).

5. Haridimos Tsoukas and Robert Chia, “On Organizational Becoming: Rethinking Organizational Change,” Organization Science 13, no. 5 (September–October 2002): 567–82.

6. Robert Chia, “A ‘Rhizomic’ Model of Organizational Change and Transformation: Perspective from a Metaphysics of Change,” British Journal of Management no. 10 (1999): 209–27, https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8551.00128.

7. William S. Lind, Maneuver Warfare Handbook (Boulder, CO: Westview Press, 1984), 3–4, 9.

8. Warfighting, Fleet Marine Force Manual (FMFM) 1 (Washington, DC: Headquarters Marine Corps, 1989), 29.

9. Zweibelson, “Breaking the Newtonian Fetish.”

10. Jani Liikola, “Luovuuden hyödyntäminen sotilasorganisaatiossa” [Harnessing creativity within military organizations], Tiede ja ase [Science and arms] no. 75 (2017).

11. Paparone and Reed, “The Reflective Military Practitioner.”

12. Ben Zweibelson, “One Piece at a Time: Why Linear Planning and Institutionalisms Promote Military Campaign Failures,” Defence Studies 15, no. 4 (2015): 360–74, https://doi.org/10.1080/14702436.2015.1113667.

13. Zweibelson, “Breaking the Newtonian Fetish.”

14. Carl von Clausewitz, On War, ed. and trans. Michael Howard and Peter Paret (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1976; reprint, 1989).

15. Christopher R. Paparone, “How We Fight: A Critical Exploration of U.S. Military Doctrine,” Organization 24, no. 4 (2017): 516–33, https://doi.org/10.1177/1350508417693853.

16. Zweibelson, “One Piece at a Time.”

17. Cristiano Castelfranchi, “Modeling Social Action for AI Agents,” IJCAI International Joint Conference on Artificial Intelligence no. 2 (1997): 1567–76.

18. Navigating the AI Frontier: A Primer on the Evolution and Impact of AI Agents (Geneva, Switzerland: World Economic Forum, 2024).

19. “What Is a Multiagent System?”

20. Navigating the AI Frontier.

21. “What Is a Multiagent System?”

22. W. J. Zhang and S. Q. Xie, “Agent Technology for Collaborative Process Planning: A Review,” International Journal of Advanced Manufacturing Technology 32 (2007): 315–25, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00170-005-0345-x.

23. Navigating the AI Frontier.

24. P. G. Balaji and D. Srinivasan, “An Introduction to Multi-Agent Systems,” in Innovations in Multi-Agent Systems and Applications, ed. Dipti Srinivasan and Lakhmi C. Jain (Berlin: Springer, 2010), https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-14435-6_1.

25. Khadijah M. Hanga and Yevgeniya Kovalchuk, “Machine Learning and Multi-Agent Systems in Oil and Gas Industry Applications: A Survey,” Computer Science Review 34 (2019): 100191, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cosrev.2019.08.002.

26. Eugénio Oliveira, Klaus Fischer, and Olga Stepankova, “Multi-Agent Systems: Which Research for Which Applications,” Robotics and Autonomous Systems 27, nos. 1–2 (1999): 91–106, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0921-8890(98)00085-2.

27. Gyu Seon Kim et al., “Cooperative Reinforcement Learning for Military Drones over Large-Scale Battlefields,” IEEE Transactions on Intelligent Vehicles (2024): 1–11.

28. Kim et al., “Cooperative Reinforcement Learning for Military Drones over Large-Scale Battlefields.”

29. M. Lehto and W. Hutchinson, “Mini-Drone Swarms: Their Issues and Potential in Conflict Situations,” Journal of Information Warfare 20, no. 1 (2021): 33–49.

30. Yong-Kun Zhou, Bin Rao, and Wei Wang, “UAV Swarm Intelligence: Recent Advances and Future Trends,” IEEE Access 20, no. 8 (2020): 1–1, https://doir.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2020.3028865.

31. Kim et al., “Cooperative Reinforcement Learning for Military Drones over Large-Scale Battlefields.”

32. George Allison, “What Do We Know About the New F-47 Fighter?,” UK Defence Journal, 22 March 2025.

33. Hanga and Kovalchuk, “Machine Learning and Multi-Agent Systems.”

34. Oliveira et al., “Multi-Agent Systems.”

35. Thom Hawkins, “We Are All Agents: The Future of Human-AI Collaboration,” Modern War Institute, 28 August 2024; and J. Caballero Testón, ”The Role of Automated Planning in Battle Management Systems for Military Tactics,” Expert Systems with Applications 297 (2025), https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eswa.2025.129259.

36. “What Is a Multiagent System?”; “Introducing Multi-agent Collaboration Capability for Amazon Bedrock,” AWS News Blog, 3 December 2024; and “Magentic-One: A Generalist Multi-Agent System for Solving Complex Tasks,” AI Frontiers Blog (Microsoft), 17 July 2025.

37. Alan Dennis, Akshat Lakhiwal, and Agrim Sachdeva, “AI Agents as Team Members: Effects on Satisfaction, Conflict, Trustworthiness, and Willingness to Work With,” Journal of Management Information Systems 40, no. 2 (2023): 307–37, https://doi.org/10.1080/07421222.2023.2196773.

38. Joseph B. Lyons et al., “Human-Autonomy Teaming: Definitions, Debates, and Directions,” Frontiers in Psychology 12 (2021): 589585, https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.589585.

39. Sarvesh Sawant et al., “Human-AI Teams in Complex Military Operations: Soldiers’ Perception of Intelligent AI Agents as Teammates in Human-AI Teams,” Proceedings of the Human Factors and Ergonomics Society Annual Meeting 67, no. 1 (2023): 1122–24, https://doi.org/10.1177/2169506723119242.

40. Sawant et al., “Human-AI Teams in Complex Military Operations.”

41. Zhang and Xie, “Agent Technology for Collaborative Process Planning.”

42. Pedro Hilario Luzolo et al. “Combining Multi-Agent Systems and Artificial Intelligence of Things: Technical Challenges and Gains,” Internet of Things 28 (2024): https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iot.2024.101364.

43. Antje Barth, “Introducing Multi-agent Collaboration Capability for Amazon Bedrock,” AWS News Blog, 3 December 2024.

44. Lucy L. Gilson and Nora Madjar, “Radical and Incremental Creativity: Antecedents and Processes,” Psychology of Aesthetics, Creativity, and the Arts 5, no. 1 (2011): 21, https://doi.org/10.1037/a0017863.

45. Markus Häyhtiö, Amanda Eklund, and Marko Palokangas, “Innovation and Adaptation in Public–Private Partnerships in the Military Domain under Broad-Spectrum Influencing: Towards a Competence-Based Strategic Approach,” Journal of Military Studies 13, no. 1 (December 2024): 10, https://doi.org/10.2478/jms-2024-0007.

46. Richard Shuster, “Trying Not to Lose It: The Allied Disaster in France and the Low Countries, 1940,” Journal of Advanced Military Studies 14, no. 1 (2023): 272, https://doi.org/10.21140/mcuj.20231401012.

47. Shuster, “Trying Not to Lose It,” 272.

48. Shuster, “Trying Not to Lose It,” 278.

49. Shuster, “Trying Not to Lose It,” 286.

50. Karl E. Weick and Robert E. Quinn, “Organizational Change and Development,” Annual Review of Psychology 50 (1999): 361–86, https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.50.1.361.

51. Tor Bukkvoll, “Russian Special Operations Forces in Crimea and Donbas,” Parameters 46, no. 2 (2016): 14–17, https://doi.org/10.55540/0031-1723.2917.

52. Bukkvoll, “Russian Special Operations Forces in Crimea and Donbas,” 14–15.

53. Bukkvoll, “Russian Special Operations Forces in Crimea and Donbas,” 16–17.

54. Alissa De Carbonnel, “Insight—How the Separatists Delivered Crimea to Moscow,” Reuters, 13 March 2014.

55. “Crimean Parliament Formally Applies to Join Russia,” BBC, 17 March 2014.

56. John N. Warfield and George H. Perino Jr., “The Problematique: Evolution of an Idea,” Systems Research and Behavioral Science 16, no. 3 (May/June 1999): 221–26, https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1099-1743(199905/06)16:3<221::AID-SRES245>3.0.CO;2-G.

57. Stefan Banach and Alex Ryan, “The Art of Design: A Design Methodology,” Military Review (March–April 2009): 107.

58. Lyons et al., “Human-Autonomy Teaming.”

59. Hanga and Kovalchuk, “Machine Learning and Multi-Agent Systems.”

60. Hao-Ping (Hank) Lee et al., “The Impact of Generative AI on Critical Thinking: Self-Reported Reductions in Cognitive Effort and Confidence Effects From a Survey of Knowledge Workers,” in CHI ‘25: Proceedings of the 2025 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (Yokohama, Japan: Association for Computing Machinery, 2025), 15, https://doi.org/10.1145/3706598.3713778.

61. Nathan J. McNeese et al., “Who/What Is My Teammate?: Team Composition Considerations in Human–AI Teaming,” IEEE Transactions on Human-Machine Systems 51, no. 4 (2021): 8–10, https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2105.11000.

62. Petteri Blomvall and Mikko Hirvi, “A Dynamic and Decentralised Headquarters to Thrive in Uncertainty,” Journal of Military Studies 13, no. 1 (December 2024): 108, https://doi.org/10.2478/jms-2024-0008.

63. Karl E. Weick, The Social Psychology of Organizing, 2d ed. (New York: McGraw-Hill, 1979).

64. Peng Lu et al., “Human-AI Collaboration: Unraveling the Effects of User Proficiency and AI Agent Capability in Intelligent Decision Support Systems,” International Journal of Industrial Ergonomics 103 (September 2024), https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ergon.2024.103629; and “What Is a Multiagent System?”

65. Alan Chan et al., “Visibility into AI Agents,” in FAccT ‘24: Proceedings of the 2024 ACM Conference on Fairness, Accountability, and Transparency (New York: Association for Computing Machinery, 2024), 958–73.

66. Michael Mayer, “Trusting Machine Intelligence: Artificial Intelligence and Human-Autonomy Teaming in Military Operations,” Defense & Security Analysis 39, no. 4 (2023): 521–38, https://doi.org/10.1080/14751798.2023.2264070.

67. Mayer, “Trusting Machine Intelligence.”

68. Koichiro Takagi, “Is the PLA Overestimating the Potential of Artificial Intelligence?,” Joint Force Quarterly 116 (1st Quarter 2025): 71–78.

69. Rolf Hobson, “Blitzkrieg, the Revolution in Military Affairs and Defense Intellectuals,” Journal of Strategic Studies 33, no. 4 (2010): 625–43, https://doi.org/10.1080/01402390.2010.489717.

70. Takagi, “Is the PLA Overestimating the Potential of Artificial Intelligence?”

71. Zweibelson, “Breaking the Newtonian Fetish.”

72. Jeremiah Hurley and Morgan Greene, “Adopting a Data-Centric Mindset for Operational Planning,” Joint Force Quarterly 116 (1st Quarter 2025): 24–32.

73. Richard Farnell and Kira Coffey, “AI’s New Frontier in War Planning: How AI Agents Can Revolutionize Military Decision-Making,” Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs, 11 October 2024.

74. Ajit Nayak, “On the Way to Theory: A Processual Approach,” Organization Studies 29, no. 2 (2008): 173–90, https://doi.org/10.1177/0170840607082227.

75. Martin Wood and Ewan Ferlie, “Journeying from Hippocrates with Bergson and Deleuze,” Organization Studies 24, no. 1 (2003): 47–68, https://doi.org/10.1177/0170840603024001680.

76. Zweibelson, “Breaking the Newtonian Fetish.”

77. Liikola, “Harnessing Creativity within Military Organizations.”