https://doi.org/10.21140/mcuj.20251602005

PRINTER FRIENDLY PDF

EPUB

AUDIOBOOK

Abstract: This article examines the integration of artificial intelligence (AI) into the military decision-making process (MDMP) through a multidisciplinary approach, with particular attention to the experimental COA-GPT system. While AI offers unprecedented opportunities to accelerate operational tempo, generates multiple courses of action (COAs), and reduces cognitive burdens on commanders and staff, the study warns against overreliance on quantitative metrics and algorithmic processes and outputs. Drawing on Carl von Clausewitz’s principles, Trevor N. Dupuy’s models, and historical failures such as Robert S. McNamara’s “body count” in Vietnam, the analysis highlights the enduring uncertainty and friction of war that cannot be captured by purely mathematical or deterministic models. AI’s risks of overfitting, black-box opacity, and the exclusion of moral, human, and contextual factors underscore the indispensable role of human judgment. The article emphasizes the need to adapt doctrine, organization, training, leadership, and infrastructure to the challenges and opportunities introduced by AI. The goal is to ensure that AI is employed as a powerful enabling tool that enhances human decision making rather than replacing it.

Keywords: artificial intelligence, AI, military decision-making process, MDMP, planning process, metrics, COA-GPT, Carl von Clausewitz, Trevor N. Depuy

The integration of artificial intelligence (AI) into the military decision-making process (MDMP) currently represents the most significant technological development in modern warfare, with the potential to fundamentally transform the traditional approach to planning and conducting operations. Ongoing conflicts and the current geopolitical situation underscore the magnitude of this transformation: on the one hand, Russian and Ukrainian forces are racing to enhance AI-driven systems on the battlefield, striving to accelerate targeting processes and battlefield analysis with ever-greater speed and precision; on the other hand, major global powers such as the United States and China are investing billions of dollars in both civilian and military AI applications, fully aware that these technologies will confer a decisive strategic advantage over potential adversaries, and fueling what is increasingly being called an “AI Cold War.”1

In the military domain, advancements in AI undoubtedly offer unprecedented potential for a pivotal revolution.2 The relative speed and effectiveness of decision making are the most critical capabilities to succeed in military operations. The current operating environment, marked by increasingly congested spaces, complex areas, contested domains, interconnected zones, constraints on the use of force, enhanced battlefield firepower and surveillance, and heightened vulnerability to cyberattacks, further emphasizes the need to maintain an operational tempo superior to the adversary.3 This advantage relies on continuously updated situational awareness that informs a timely decision-making process.

Drawing from the most significant cornerstone of naval warfare, which emphasizes the necessity to strike effectively first, we can assert that in all other domains as well, there is now more than ever a critical need to act effectively and decisively first.4 To preserve initiative and gain a temporal advantage over the adversary, superiority in the AI field will certainly prove to be a key factor.

Beyond the technical aspects, which fall outside the scope of this analysis, one of the most pressing questions for effectively harnessing this potential is how AI can be integrated into the planning process to ensure the ability to act effectively first.

While prior research has emphasized the benefit of AI’s role in military planning processes, weaknesses remain in understanding how to implement it, accounting for the inherent uncertainty of war, avoiding overreliance, and eluding predictable results.5 This research investigates the integration of AI into MDMP, emphasizing the need for speed while acknowledging the inherent uncertainty of war, commonly referred to as the “fog of war.” The study addresses the central problem that while AI can enhance decision-making efficiency, war cannot be reduced to purely mathematical estimates, as demonstrated by historical blunders such as Robert S. McNamara’s body count strategy or the “insurgency math.”6

Aiming to achieve this objective, the investigation follows a multidisciplinary path, integrating insights from military history and theory, philosophy, epistemology, and technology, and unfolds across four analytical phases: first, establishing theoretical foundations through examination of Clausewitzian principles and historical precedents of quantitative military analysis; second, analyzing the technical capabilities and inherent limitations of contemporary AI systems, particularly machine learning risks of overfitting and opacity; third, conducting a detailed case study examination of the experimental COA-GPT system as a representative example of AI-MDMP integration; and lastly, proposing specific recommendations for further AI-MDMP development and advocating for the renovation of our Services through the doctrine, organization, training, material, leadership, personnel, facilities (DOTMLPF) framework, to ensure that AI is employed as a tool rather than a definitive decision maker, with human judgment remaining indispensable to leverage its tactical advantages while avoiding blind dependence on its outputs.

Deductive and Inductive Reasoning for Predicting Future Outcomes

To set the foundation of this research, it is essential to first reflect on the lessons, frequently cited yet often forgotten, that Carl von Clausewitz offers in his most renowned work on the reliability of numbers, which is as nightmarishly complex and bizarre as Kafka’s works.7 James Willbanks, director of the Department of Military History at the U.S. Army Command and General Staff College, humorously recounted that in 1967, some Pentagon officials ventured into the building’s basement, where the computers were located. With great enthusiasm, they began inputting everything quantifiable into punched cards: numbers of ships, tanks, helicopters, artillery pieces, machine guns, and even ammunition. After feeding all this data into the “time machine,” they posed the crucial question: “When will we win in Vietnam?” They then left for the weekend, confident that they would have an answer by Monday. After their return, they found a card in the output tray that stated, “You won in 1965.”8

Although this is merely an old, apocryphal tale, the anecdote recounted by Willbanks reveals how humanity’s relentless quest to simplify the complexity of the world into universal laws can lead to an excessive oversimplification of reality, increasing the risk of erroneous predictions.9 This risk is inherent in inductive reasoning, which, starting from specific premises, seeks to arrive at general conclusions. Unlike deductive reasoning, however, these conclusions can never be deemed entirely certain, even when experience suggests otherwise.10

Far from discrediting one reasoning process over the other, it is necessary to highlight that, in the military domain, both deductive reasoning (e.g., studying adversary doctrine) and inductive reasoning (e.g., analyzing recent enemy operations) form the foundation of military intelligence.11 These methods are essential for predicting an adversary’s future actions and supporting a commander’s decision-making process. However, the limitation of such predictions is that they rely solely on past experiences, making them unable to anticipate when or how an adversary might act unconventionally or irrationally, especially given the constant need to adapt to evolving situations.12

Consider, for example, Sir B. H. Liddell Hart’s analysis of Germany’s mobile offensive operations beginning in 1939 (the so-called blitzkrieg) or Eliot A. Cohen and Phillips O’Brien’s discussion of Ukraine’s fierce resistance against Russia’s invasion in February 2022.13 Both cases illustrate the unpredictability of such events, emphasizing the inherent limitations of rationalization in fully grasping future actions.

The Often-Forgotten Principles of Clausewitz

The observations above emphasize Clausewitz’s argument regarding the limitations of doctrine as a theory based exclusively on past historical events, cautioning against using it as a universal model for the art of war in all conditions. Rather, it should be a tool for educating the minds of future commanders, fostering their judgment and intellectual instinct, without reducing warfare to a fixed mathematical formula. Furthermore, Clausewitz continues his critique of rigid rules and fixed schemes based on material factors by outlining three principles that illustrate how such frameworks merely oversimplify reality.14

First, he emphasizes the uncertainty of war and critiques the superiority of numerical strength as a metric for success. Such a mechanical simplification neglects key factors such as the enemy’s reactions, moral elements such as courage and the will to fight, and the commander’s role.

Second, Clausewitz highlights the positive reaction, defined as the uncertainty stemming from the reciprocity of actions between two opponents. This principle underscores that the effects of our actions, as well as those of the enemy, cannot be predicted with certainty and should not rely merely on theoretical assumptions. This concept is further validated by one of the major trends—now almost a constant—outlined by Wayne P. Hughes in his work Fleet Tactics and Naval Operations. Hughes asserts that the effectiveness of weapon systems is consistently overestimated before their actual use in conflict.15

Finally, Clausewitz underlines the uncertainty of information, which is often unreliable or incorrect, arguing that chance and talent play a crucial role in mitigating these uncertainties. Considering the tragic consequences of the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor or the Battle of Goose Green during the Falkland Islands War, both events illustrate how flawed intelligence can significantly influence the outcome of a battle.16

Although these limitations may seem self-evident, they are frequently overlooked in the face of humanity’s intrinsic desire to identify a logical process based on statistics, metrics, and models to address a problem and devise a rational solution with rigorously predetermined probabilities of success. One of the most notable examples of this mindset is linked to McNamara’s tenure as U.S. Secretary of Defense from 1961 to 1968. His technocratic and rationalist approach had catastrophic consequences for the Vietnam War.17 However, while McNamara later expressed regret for his role, acknowledging in his 1995 memoir In Retrospect: The Tragedy and Lessons of Vietnam that the war was “wrong, terribly wrong,” critics have noted that this contrition was limited and delayed.18 Many observers argue that McNamara’s reflections often downplayed personal responsibility, framing errors as honest mistakes amid complex circumstances rather than recognizing the human cost of his policies.19 This partial remorse underscores the enduring tension between technocratic decision-making and the profound, tragic realities of warfare.

The Analytical Approach and Its Contradictions

After his appointment as secretary of defense by President John F. Kennedy, McNamara faced the challenging mission of introducing order and rationality to a fragmented Department of Defense bureaucracy marked by internal conflicts. Leveraging the expanded powers granted to the Office of the Secretary of Defense by the 1958 Defense Reorganization Act, McNamara took decisive steps to assert control over the Pentagon. One of his most significant initiatives was the implementation of the Planning, Programming, and Budgeting System (PPBS), a model inspired by managerial processes at Ford, where he had previously worked. As described in the contemporary publication How Much Is Enough?: Shaping the Defense Program, 1961–1969, edited by Alain C. Enthoven and K. Wayne Smith, the PPBS represented an innovative approach.20 It organized the department’s budget around functional objectives tied to specific missions, thereby integrating strategic planning with financial planning. Additionally, the introduction of systems analysis enabled comparative evaluation of various programs, assessing their relative effectiveness in achieving similar operational goals and attempting to reduce uncertainties through scientific analysis. This reorganization aimed not only to optimize resources but also to create a more rational and coherent decision-making structure.

However, the Vietnam War exposed the limitations and contradictions of this methodology. In a war where territorial control, distances covered, or cities occupied held little significance, the enemy’s body count emerged as a seemingly more compelling metric of progress and success.21 This system, based on calculations, charts, and statistics, produced two unintended effects. At the tactical level, units deliberately exaggerated enemy casualty figures while minimizing their losses to appease superiors.22 At the strategic level, this approach proved inadequate in measuring the Viet Cong’s determination to achieve their objectives.23 The futility of this method was later confirmed by General Douglas Kinnard’s historical essay, The War Managers, which revealed that only 2 percent of American commanders considered body count an effective metric for measuring success.24

The consequences of McNamara’s hyperrational approach, transplanted from the economic sphere to the military domain, underscore how Clausewitz’s first and third principles remain unchallenged. On the one hand, mere numerical comparisons of strength fail to account for the moral elements essential in conflict, rendering them ineffective as predictors of victory. On the other hand, the fallacy of numerical metrics becomes exponentially greater when the numbers themselves, such as the Viet Cong body count, are derived from flawed or manipulated information.25

The contradictions of this approach are even more apparent in counterinsurgency (COIN) operations. As Jon Krakauer notes in Where Men Win Glory: The Odyssey of Pat Tillman, the Pentagon relied on quantitative indicators such as insurgent body counts, completed operations, or secured objectives to monitor progress in the wars on terror in Iraq and Afghanistan.26 According to Krakauer, this methodology demonstrates McNamara’s enduring legacy and the continued reliance on numerical metrics within military and political organizations. Beyond the oversimplification inherent in reducing war to a mere spreadsheet, this system, as David Kilcullen argues in The Accidental Guerrilla: Fighting Small Wars in the Midst of a Big One, ignores critical factors such as local population support (“hearts and minds”), governance capacity—both military and civilian—and the sustainability of operations over time.27 Moreover, this quantitative criterion fails to link tactical objectives with strategic goals, or, in other words, to establish a coherent process between ways, means, and ends.28 As a result, it often produces overwhelming tactical victories but fails to achieve the desired end state.29

Despite recognizing the fallacy of tightly controlling the relationship between allocated resources and performance expectations (translated into mere numbers), military culture remains deeply entrenched in this mindset. As Edward N. Luttwak observed in his 1984 work, The Pentagon and the Art of War: The Question of Military Reform, he reflected: “Much of what went wrong in Vietnam belonged to the time and place, but much derived from military institutions that have not yet been reformed . . . and that continue to fail in converting manpower and money into effective military power.”30

The Use of Metrics in Planning

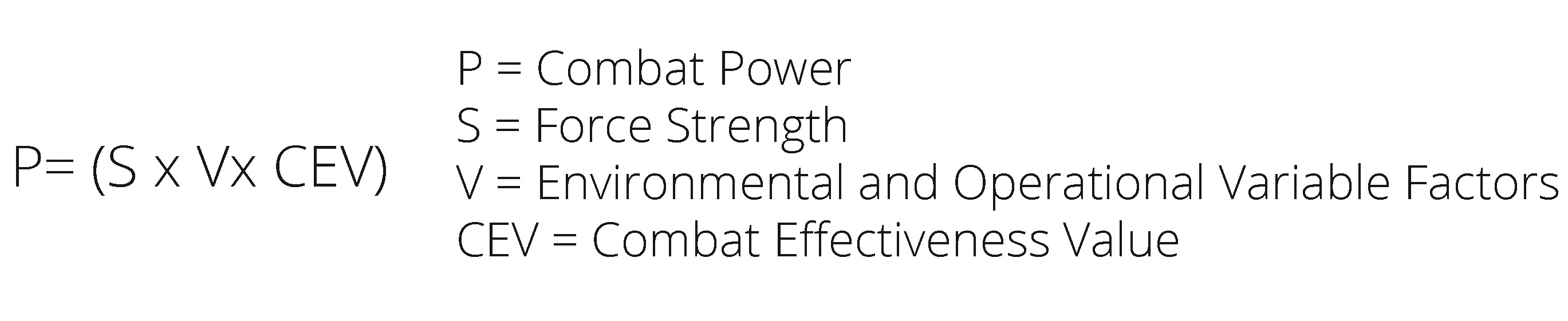

Far from condemning the use of metrics, force ratios, and mathematical calculations, the ongoing debate over their effectiveness remains unresolved.31 In War by Numbers: Understanding Conventional Combat, Christopher A. Lawrence, drawing on a database of 752 battles fought between 1904 and 1991 and the exemplary theories of Colonel Trevor N. Dupuy (the Quantified Judgment Model), underscores the utility of metrics such as force ratios, rates of advance, and casualty estimates in determining the outcome of battles. Even Clausewitz, in chapter 8 of book III of On War, affirms that “in tactics, as in strategy, superiority of numbers is the most common element in victory.”32 However, it is essential to note that this superiority should not be understood in absolute terms but rather in relation to the concentration of a superior force at a decisive point. Both Dupuy and Lawrence, however, identify numerous other factors influencing the conduct of military operations, thereby advocating for a comprehensive analysis. Elements such as morale, training levels, motivation, cohesion, surprise, logistical organization, and the adaptability of commanders and units play a critical role in determining the outcome of combat. These elements contribute to what Dupuy terms quality of troops, now more commonly known as combat effectiveness.33

Figure 1. Depuy’s combat power equation

Source: Shawn Woodford, “Dupuy’s Verities: Combat Power =/= Firepower,” Dupuy Institute, 12 May 2019.

Combat Effectiveness: A Complex and Intangible Factor

Depuy described combat effectiveness (CEV) as the sum of “the intangible behavioral or moral factors of man that determine the fighting quality of a combat force.”34 These factors are meticulously categorized into leadership (encompassing training, experience, logistics, and other multipliers), disarticulation factors (such as surprise, suppression, culmination point), force quality (interpreted as relative combat effectiveness, morale, cohesion, fatigue, and trends over time), and the relationship between physical and moral factors (such as friction, defensive posture, momentum, and luck).35

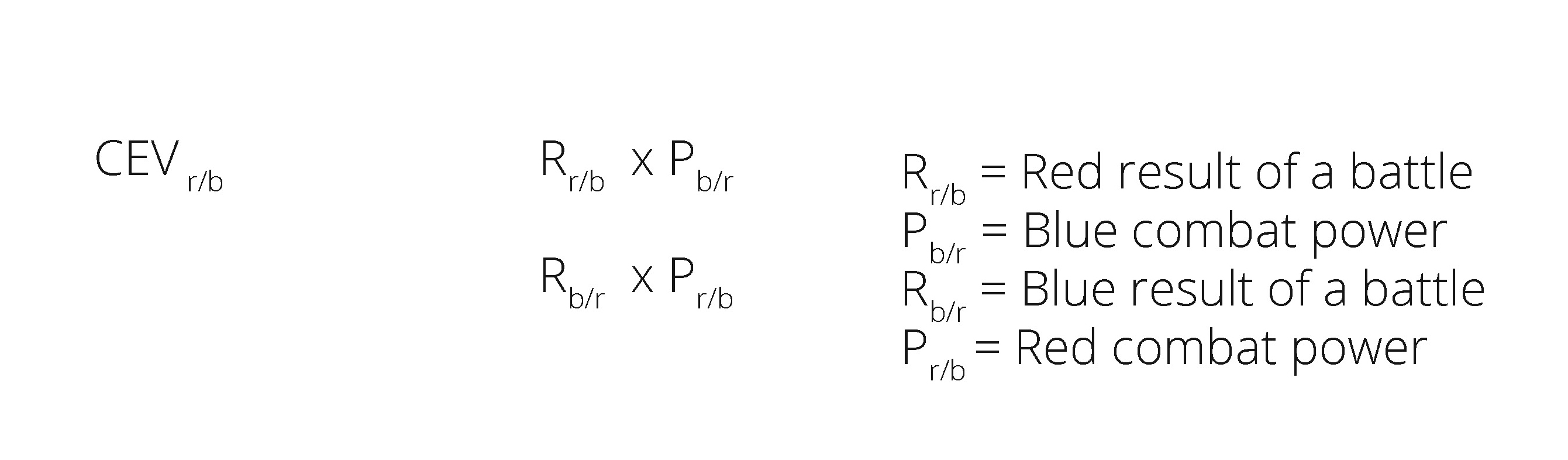

Figure 2. Depuy’s combat effectiveness equation

Source: Gerhard Geldenhuys and Elmarie Botha, “A Note on Dupuy’s QJM and New Square Law,” ORiON 10, nos. 1–2 (1994): 45–55, https://doi.org/10.5784/10-0-455.

However, as noted by Lieutenant Colonel Z. Jobbagy (Hungarian Defence Forces) in his analysis of fighting power, the “frustrating intangibility” of these factors and the inherent difficulty in quantifying them prevent us from relying on these variables for the effective prediction of battle or campaign outcomes.36

Even from a purely mathematical perspective, the attempt to accurately measure CEV and incorporate it into a new “square law,” adapted from Lanchester’s celebrated equations and revised by Dupuy, has been called into question by the Operations Research Society of South Africa (ORSSA).37 Researchers from the society’s Department of Applied Mathematics, after identifying mathematical discrepancies in Dupuy’s formula for calculating CEV, argue that “even though Lanchester’s theories have been significantly developed and are often used in war games, there are serious doubts about their potential application in real battles.”38

The Debate on Metrics, Mathematical Models, and the Dynamic Approach

The discussion on the effectiveness of metrics and mathematical models continues with the introduction of a dynamic approach, such as the one developed by Joshua Epstein in 1985.39 Epstein’s model, designed to provide a valid alternative to static analysis for assessing NATO’s resource allocation effectiveness during the Cold War, is based on the premise that combat is “a process whose course and outcome depend on factors that cannot be captured in a simple beans count.”40 Among these factors, he lists elements such as “technology (weapon quality); troop training and skills; command, control, communications, and intelligence (C3I); logistics; relative concealment and exposure (use of terrain); ally reliability; readiness; surprise; and the relative willingness to endure attrition and concede territory.”41 To support his argument, Epstein also turns to historical examples, citing battles and campaigns such as Austerlitz (1805), Antietam (1862), the invasion of France (1940), Operation Barbarossa (1941), and Kursk (1943), highlighting how victory can smile even upon those who, under analysis, appear numerically inferior.42

Despite its innovative nature and detailed mathematical analysis, Epstein’s model has not been immune to criticism. A 1988 publication edited by the U.S. Congress implicitly affirmed the validity of the aforementioned properties enunciated by Clausewitz, stating: “There are questions about the equations used in the models, whether the model or scenario is biased in favor of or against a particular faction, and the sensitivity of the model to different assumptions.”43 The publication further noted:

Epstein’s model, like any quantitative method for assessing the relationship between two military forces, cannot be used to predict the outcome of a real conflict. No mathematical model, even one attempting to capture the dynamics of war, can replicate all the factors that determine the course of a battle. Some factors that have a significant impact on the outcome of a clash, such as leadership, morale, and tactical competence, cannot be quantified.44

Clausewitz’s theories and the U.S. Congress’s conclusions are further reinforced by the observations of Russian writer and philosopher Leo Tolstoy. In his celebrated work, War and Peace, Tolstoy illustrates the complexity, unpredictability, and apparent disconnect between the theory and practice of war through the eyes of those who lived it. Tolstoy, employing a skillful analogy with the game of chess, critiques the rationalistic and deterministic vision of war, underlining how human beings strive to impose order and logic on phenomena that are inherently chaotic and uncertain.45

Unlike chess, where the player has a sense of control over events thanks to the complete visibility of the board and its fixed rules, Tolstoy argues that the reality of war introduces numerous unpredictable variables: chance, human emotions, confusion, and the will of combatants. These factors render the claim of total control futile and illusory. Through this comparison, Tolstoy also seeks to diminish the central role often attributed to commanders, who are frequently regarded as the sole architects of decisive victories.46 He argues that their success is not uniquely dependent on their skill but rather on a network of uncontrollable circumstances and factors, such as the contributions of soldiers, weather conditions, and sheer luck.47 In other words, Tolstoy asserts that war cannot be reduced to an ordered game like chess but remains an anarchic and chaotic phenomenon where human control is limited.

The discussion thus far allows us to grasp the inherent risks of inductive reasoning—when one attempts to derive a general rule (a mathematical equation) from a particular phenomenon (a specific battle). This risk is further amplified by the heuristic methods employed to formulate mathematical equations for force ratios, which aim to predict and “control” the outcome of a future event using procedures that are not rigorous and whose validation will always remain uncertain.

On the other hand, as previously emphasized, the use of metrics and mathematical equations in the military domain remains indispensable. They are invaluable tools for planning the forces to be assigned to specific tasks, helping us determine whether they are proportionate to them and identifying any associated risks. However, to borrow Epstein’s words, mathematical models must remain solely a force-planning tool, for which “depictive realism and precision are not absolutely necessary.”48 These models should not cross the feeble line into our unconscious desire to predict an outcome, even though such prediction is not “definitively and eternally precluded.”49

The Final Frontier of Inductive Reasoning: Artificial Intelligence

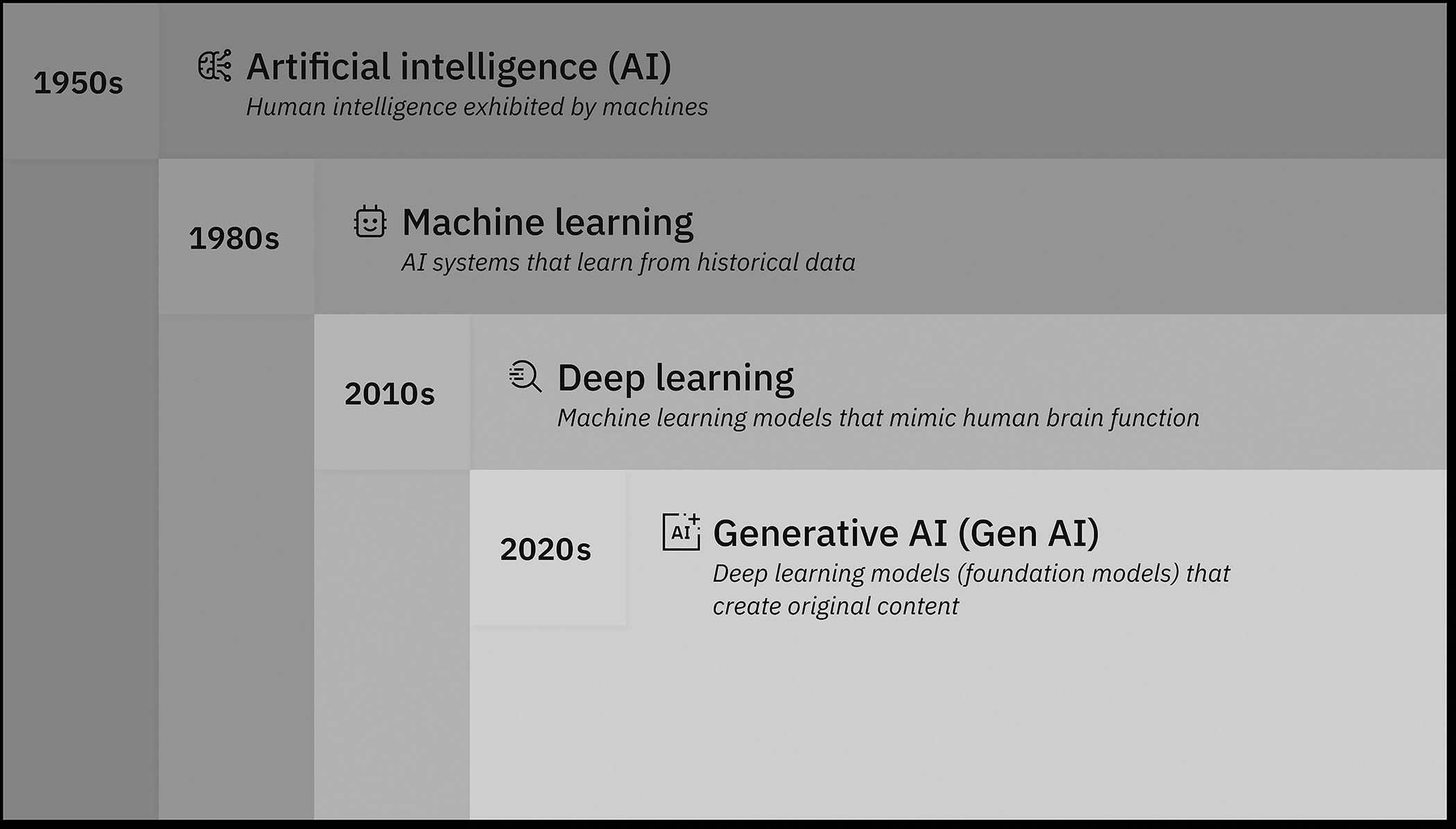

The principles of inductive reasoning and their inherent limitations, along with those of metrics based on historical data and heuristic methods previously examined, provide a foundation for introducing what is arguably the most significant technological revolution of our time—AI. According to IBM, AI is defined as “a collection of systems or machines that imitate human intelligence to perform tasks and are capable of iteratively improving themselves based on the information they collect. Applications of AI include natural language processing, image recognition, and the prediction of future events through data analysis.”50

To fully understand both the potential and the risks associated with the use of AI and its most advanced stage of development, generative AI (GenAI), it is essential to analyze the models upon which these technologies are based. These models include machine learning (ML) and deep learning (DL).

Machine learning refers to the development of algorithms that enable computers to learn from input data and to improve their performance over time without being explicitly programmed for specific tasks.51 In other words, by analyzing large volumes of data, machine learning systems are capable of identifying recurring patterns and harnessing this information to make decisions or produce predictions.

Deep learning, on the other hand, is a subfield of machine learning that relies on multiple layers of artificial neural networks.52 The term deep refers to the use of numerous layers that allow for the modeling and interpretation of complex data. These deep neural networks are inspired by the structure of the human brain and are particularly effective in processing unstructured data such as images, audio, and text. This architecture enables models to learn hierarchical representations of data, beginning with low-level features and advancing to increasingly abstract and complex concepts.53

Figure 3. Correlation between artificial intelligence, machine learning, deep learning, and generative AI

Source: IBM.com, adapted by MCUP.

The Primary Risk of Machine Learning: Overfitting

The use of the aforementioned models, which are fundamental to the learning process of AI, highlights the profound distinction between AI systems and conventional computing. While traditional software works by following fixed instructions explicitly programmed by humans to convert specific inputs into predetermined outputs, artificial intelligence systems use algorithms designed by humans that enable the system to learn from data and improve over time. Instead of relying solely on predefined rules, AI autonomously builds internal models that map inputs to outputs, allowing it to adapt and handle new situations without explicit reprogramming. Subsequently, AI systems continue to learn through iterative processes involving trial, error, and feedback provided by human developers, thereby reconfiguring internal mappings and the connections among acquired data.54

The principal risk associated with this learning process is that AI’s neural networks may resort to memorizing responses rather than genuinely learning the underlying principles. This phenomenon, often referred to as the “parrot effect,” has been effectively illustrated in an interview conducted by Alexandre Piquard with linguist Emily Bender.55

From a technical perspective, this issue is known as overfitting, which refers to a model’s failure to generalize due to the limited size of the training dataset. Such datasets often lack enough examples to accurately represent the full range of possible input values. As a result, the model’s predictions become highly sensitive to variations in new data, leading to unstable and unreliable behavior. This significantly reduces the model’s usefulness in complex or real-world scenarios.56

Table 1. Example of overfitting

|

Weight (g)

|

Price ($)

|

|

100

|

1.00

|

|

150

|

1.50

|

|

200

|

2.00

|

Source: courtesy of author, adapted by MCUP.

In an attempt to provide a simple example illustrating the risks associated with overfitting, let us consider a small dataset containing information on the prices of a given product as a function of its weight (table 1).

A model not affected by overfitting would identify a simple relationship, such as:

Weight/100 = Price

By contrast, a model affected by overfitting would attempt to fit the training data perfectly, producing a complex curve that passes exactly through the given points like a parabola. Although this approach may perform well on the specific dataset used for training, it would likely fail to generalize. For instance, when presented with a new input (e.g., a product weighing 120 grams), the model might produce an inaccurate prediction due to its excessive sensitivity to the original data.

Moving to the military field, a constant in the history of naval warfare says, “Firepower is less effective than anticipated from peacetime tests and firing exercises.”57 Overfitting in AI systems has the same limitations, as algorithms can perform well on training data but may not generalize accurately to the complex and dynamic environments of a real battlefield.58 Overfitting leads to brittleness, where AI systems are unable to adapt to novel battlefield conditions, resulting in erroneous target identification or misclassification that can have fatal consequences, such as striking friendly forces, civilian objects, or misidentifying combatants.59 This is exacerbated by the scarcity of high-quality, diverse training data and the use of synthetic or biased datasets, which can embed systematic errors into decision-making processes.60 Furthermore, overfitting contributes to the following “black box” risk, where AI decisions lack transparency and explainability, undermining human trust or prompting overreliance in high-stakes contexts.

The Second Risk of Machine Learning: The Black-Box Problem

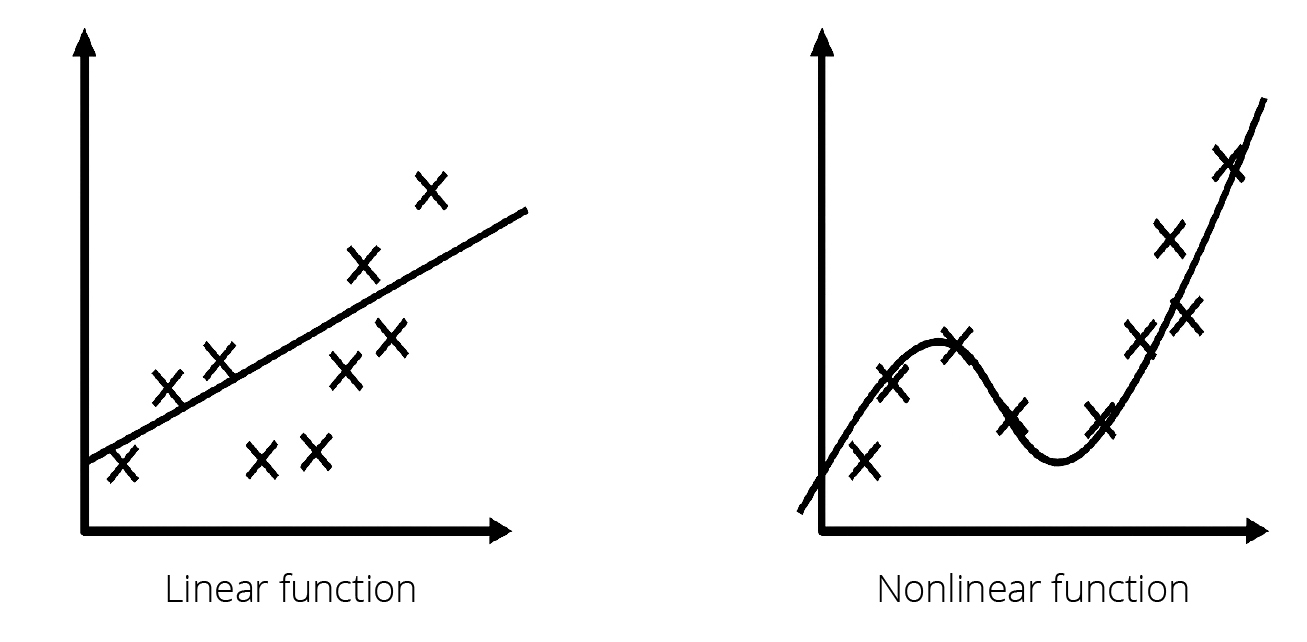

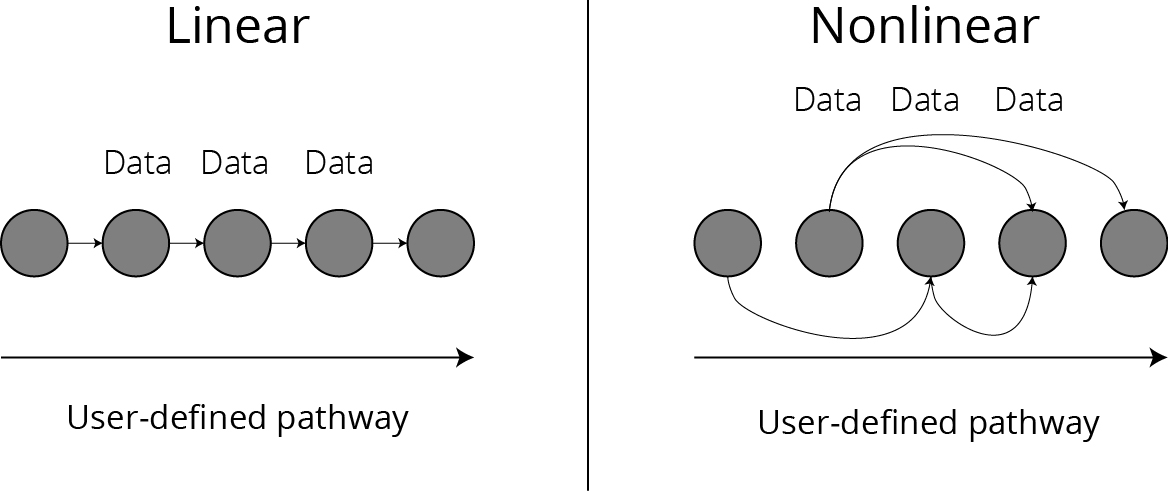

The second major risk associated with the learning models underpinning AI arises from the use of nonlinear regression to represent relationships between input variables. Nonlinearity implies that the relationship between a dependent variable and an independent variable is neither proportional nor constant. This allows models to capture and represent multiple complex relationships that would be difficult to identify through linear approaches. As a result, AI systems can construct more realistic and accurate representations of data, thereby enabling the resolution of complex problems with greater precision.61

Figure 4. Linear versus nonlinear regression

Source: Medium.com, adapted by MCUP.

Figure 5. Linear versus nonlinear regression network

Source: courtesy of author, adapted by MCUP.

However, the intrinsic nature of nonlinear processes introduces what is commonly referred to as the black-box problem, wherein the internal decision-making mechanisms of the AI are not readily interpretable by human observers. In other words, while the algorithm can generate an output, such as a prediction or a classification, it does not make transparent the reasoning or path by which that output was reached.62

In the distinguished work Genesis: Artificial Intelligence, Hope, and the Human Spirit, Henry A. Kissinger emphasizes that, although the phenomenon is well known, it has not deterred millions of people from passively accepting the veracity of most outputs provided by AI. This acceptance stands in stark contrast to the principles of enlightened analytical reasoning. In our understanding of rationality, the legitimacy of certainty is grounded in its transparency, reproducibility, and logical validation. However, this principle vanishes in the opaque reasoning processes of AI. The risk, therefore, is that without a critical analysis of AI-generated outputs, “these new ‘brains’ could appear to be not only authoritative but infallible.”63

A replicable experiment that demonstrates the fallacy of AI in providing accurate answers, while disguising false information with an authoritative and convincing tone, is to request citations or a bibliography on a specific topic. In many cases, as summarized in the results of a study conducted by Andrea Capaccioni, attempting to verify the requested citation or topic in the AI-provided bibliography will reveal the inaccuracies of the answers (table 2).64

Table 2. Results of Capaccioni’s research about the reliability of bibliographies generated by AI

| ChaptGPT 3.5 |

Bard |

|

Correct quotation/ argument

|

2

|

Correct quotation/

argument

|

4

|

|

Incorrect quotation/

argument

|

8

|

Incorrect quotation/

argument

|

6

|

Source: Andrea Capaccioni, “Sull’affidabilità delle bibliografie generate dai chatbot. Alcune considerazioni,” AIDAinformazioni, nos. 1–2 (January–June 2024).

The critical consequences arising from the combination of what is known as AI’s Dunning-Kruger effect and the phenomenon of anthropomorphism, where humans are more inclined to trust responses from a humanized AI, are readily apparent. 65

In the military domain, this risk will translate into potentially critical failures in decision-making processes where human operators rely on autonomous systems without a clear understanding of the underlying rationale. Tracing the premises already known from a previous investigation conducted by the Army Research Laboratory on autonomous agents in 2014, the black-box nature of advanced AI models means that commanders and soldiers may receive outputs, such as threat assessments, target identifications, or mission orders, that are not accompanied by transparent explanations of how those conclusions were reached.66 This opacity can lead to misplaced trust or unwarranted skepticism, both of which impair effective collaboration between humans and machines. Without proper transparency, the ability to calibrate trust appropriately is compromised, increasing the likelihood of overreliance or disuse of automation, which in turn can degrade situational awareness and operational effectiveness. Given the high-stakes environment of military operations, where rapid and accurate decision making is crucial to addressing the black-box problem through enhanced agent transparency is essential to ensure that autonomous systems serve as reliable and comprehensible partners rather than inscrutable tools.

AI-Military Decision-making Process:The Future of Military Planning

In the purely military domain, AI has found numerous applications in recent years, sparking an arms race and technological innovation comparable to the nuclear arms race during the Cold War.67 From autonomous weapon systems and intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance (ISR) to predictive logistics and recent advancements in cyber operations, AI permeates every domain and dimension of warfare.68

Regarding command and control, the implementation of AI has found fertile ground, particularly in enabling the effective conduct of distributed operations through the creation of a real-time, updated common operational picture, facilitating the targeting process.69 The ultimate goal is singular: to accelerate the decision-making process of commanders and units to gain a cognitive advantage over the enemy, thus maintaining a favorable operational tempo.

The magnitude of this advantage is particularly evident when viewed in light of the theories of Colonel John R. Boyd, who, based on his experiences in aerial combat during the Korean War, theorized that it is the speed at which the human brain processes information and makes decisions that largely determines who wins or loses a battle or war. According to his theory, victory or defeat is not determined by the performance of a weapon, but by the speed of a continuous cycle of observation, orientation, decision, and action (the OODA loop).70

The overwhelming force of the technological revolution brought by AI now seems to break the final barrier of what was once considered a strictly human domain: the tactical level of operations planning. From studies on the automation of intelligence preparation of the battlefield (IPB) to the vision of semiautonomous future command posts, military AI developments continue to work toward an effort to automate the entire MDMP. 71

As skillfully analyzed by Colonel Michael S. Farmer, the primary objective remains the development of “the ability to understand and react first in a dynamic environment capable of rapidly invalidating previous plans, which will be essential to seizing and retaining the initiative.”72 This ability would manifest in the semiautonomous execution of the entire MDMP, evaluating continuous updates of the current situation, selecting the best course of action (COA) based on it, and anticipating the execution of potential branch plans.

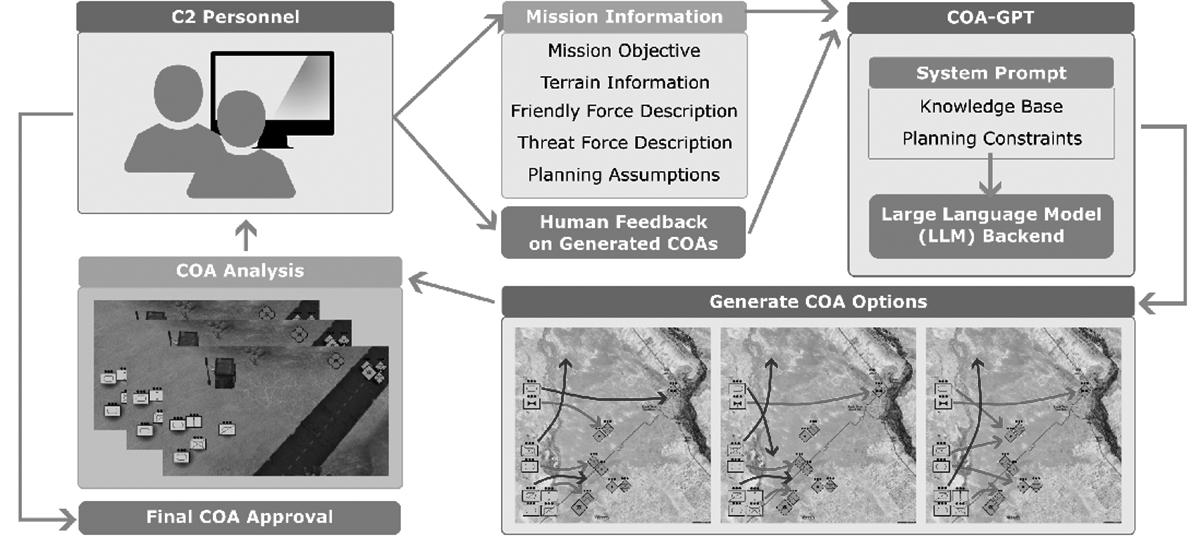

AI-Military Decision-making Process: The COA-GPT Case

A concrete initial attempt to automate the decision-making process by autonomously developing a COA through the use of an algorithm employing large language models (LLMs) is currently under study at the U.S. Army Combat Capabilities Development Command (DEVCOM) Army Research Laboratory.73 This algorithm, named COA-GPT, appears to be capable of analyzing all mission variables provided by a commander and their staff (inputs) and subsequently proposing a COA (output) that aligns with those from higher levels and can adapt to human feedback. Once the COA is approved, the algorithm will conduct a simulation and performance analysis, evaluating outcomes through objective metrics such as rate of advance and friendly and enemy casualties. This process highlights a human-centered paradigm, where the commander retains decision-making control while benefiting from the speed, adaptability, and creativity of the AI system. The LLM does not merely provide options; it enables the tactical co-creation of the plan.

Figure 6. Linear versus nonlinear regression network

Source: Vinicius G. Goecks and Nicholas R. Waytowich, “COA-GPT: Generative Pre-Trained Transformers for Accelerated Course of Action Development in Military Operations,” 2024 International Conference on Military Communication and Information Systems (Brussels, Belgium: North Atlantic Treaty Organization, 2024): 1–10, https://doi.org/10.1109/ICMCIS61231.2024.10540749.

To fully grasp its potential, it is necessary to first explore the concept of LLMs. These can be defined as artificial systems capable of acquiring linguistic competencies through training on vast amounts of data. During their large-scale learning phase, the models do not store individual facts but rather learn linguistic patterns, such as word co-occurrences, syntactical construction of sentences, and conceptual relationships between terms. Through the repeated application of this process on a massive scale, the model develops the ability to generate coherent text, answer questions, and create content with linguistic characteristics very similar to human expression.74

Their architectural structure is based on the Transformer, a layered model that analyzes each word in relation to all others within the textual context, without relying on sequential reading. In other words, the system does not simply read from left to right but understands connections between even distant words within a sentence or context.75

In the case of COA-GPT, LLMs previously trained with military doctrine knowledge are used to receive a prompt containing operational information provided by the commander or their staff in the form of text and images, which will then be analyzed by the artificial system. Subsequently, the LLM’s ability to interpret free text and images, combined with the assimilation of military doctrine, will enable COA-GPT to simulate tactical reasoning without the need for specific training for each scenario and to modify its outputs in real time based on human feedback.76

COA-GPT and the Use of Metrics

The use of quantitative metrics to assess the quality of COAs generated by COA-GPT represents one of the central elements of the project, but at the same time, it constitutes one of its most critical and delicate areas.

The system evaluates each course of action based on three primary metrics:

1. Total Reward: a score that assigns positive values (+10) for the elimination of enemy forces or the seizure of key terrain, and negative values (-10) for the loss or retreat of friendly units.

2. Friendly Force Casualties: the total number of friendly units lost.

3. Threat Force Casualties: the losses inflicted on the enemy.

At first glance, this approach allows for an objective and comparable evaluation of the different COAs generated, creating a feedback system beneficial both to the machine and to the human commander. However, these metrics present structural limitations that echo historical problems previously discussed.

In the same way that McNamara’s body count metric became problematic, the Threat Force Casualties metric adopted in COA-GPT, if isolated or decontextualized, risks replicating the same illusion.77 A COA that eliminates the highest number of enemies may seem optimal, but it could simultaneously leave out a more favorable form of maneuver (such as penetration, encirclement, or envelopment), which exploits the enemy’s gaps and avoids unnecessary attrition, undermines the legitimacy of friendly forces, causes unmeasured collateral damage, and results in a tactical victory but a strategic defeat

A comparison between COA-GPT and the more recent insurgency math used during the Global War on Terrorism in Iraq and Afghanistan highlights further limitations. The metrics adopted fail to include any measure of the informational domain, the enemy or civilian population’s will, the perception of success by the actors involved, or the long-term consequences.78

Furthermore, returning to the theories put forward by Clausewitz and Depuy, these limitations demand greater reflection on the future developments of an AI-MDMP. As it stands, it is possible to argue that the Clausewitzian “friction” is completely absent from COA-GPT’s metrics. The scores assigned within the system presume a perfectly observable and entirely deterministic world, where every action has a clear and measurable effect.79 While this approach may be useful in a simulated environment, it violates the fundamental Clausewitzian principle of the “fog of war,” excluding the human element of uncertainty, risk, and intuition that is central to the reality of combat.

Finally, returning to Depuy’s model, which sought to translate military interaction into a mathematical function, the oversimplification of battle and the predictive fallacy become even more evident. The metrics adopted in the COA-GPT algorithm show disturbing conceptual analogies with the Depuy approach:

1. Total reward is an algebraic sum of kinetic events such as bridge crossings, enemy eliminations, and casualties sustained.

2. Friendly or enemy casualties are mere numerical counts, disconnected from any qualitative consideration (e.g., the symbolic value of a loss or the loss of a leader).

3. The analysis is based on repeated rollouts in simulated environments, which, though diversified, do not introduce structural uncertainty or friction.

In other words, the current system risks confining military planning to an engineering logic, where victory seems to favor those who optimize best, yet loses sight of the Clausewitzian essence of war as a domain of chance, will, and commanders’ insight (table 3).

Table 3. Comparative analysis of aspects related to the art and science of war

|

Aspect

|

Clausewitz

|

DePuy

|

COA-GPT

|

|

fog of war

|

central

|

ignored

|

ignored

|

|

friction

|

inevitable

|

absent

|

absent

|

|

qualitative parameters

|

fundamental

|

secondary

|

excluded

|

|

human context

|

dominant

|

marginal

|

absent

|

|

quantitative output

|

secondary

|

primary

|

primary

|

Source: Courtesy of author, adapted by MCUP.

In conclusion, Clausewitz, DePuy, and the metric failures of the past teach us that war is an open, complex system that cannot be reduced to absolute numbers. COA-GPT, despite its technical brilliance, still exhibits a closed ontology, where the model assumes to know the exact position of every unit, assigns absolute and symmetric value to losses, and operates in an environment free from friction or informational distortion. This brings us back to two inherent risks in AI, which were discussed earlier. On the one hand, there is the risk of tactical overfitting, where the algorithm generates perfect COAs for the simulated world, but they are not transferable to the real world. On the other hand, there is the false illusion of objectivity and control for decision makers, leading commanders and staff to underestimate what cannot be quantified.

AI-Military Decision-making Process: Advantages and Opportunities

Despite the limitations of the current development of AI-MDMP, it certainly offers significant advantages and opportunities for maintaining a favorable operational tempo over the enemy. If the opposite were true, the rapid adoption of AI in the Russian-Ukrainian conflict and in strategic initiatives—such as the United States’ Project Maven and Russia’s command-and-control (C2) programs—would defy comprehension. Project Maven’s operational success demonstrates this in practice: brigades equipped with the AI-powered system achieved targeting performance comparable to the 2003 Iraq War using only 20 soldiers instead of 2,000.80 Russia is pursuing similar objectives: according to the Saratoga Foundation, Russia’s 27th Central Research Institute is working on an automated command systems able to analyze intelligence data, generating battle plans while also finding the best variants for a specific situation, based on self-teaching.81

Indeed, one of the greatest advantages of COA-GPT is the drastic reduction in the time required to generate, analyze, and compare different COAs. Traditionally, the COA development phase in the MDMP takes hours, if not days, especially in complex and multi-domain environments. COA-GPT can produce valid COAs in just seconds, enabling almost immediate responses to battlefield changes. This results in a drastic reduction of the OODA loop and the overcoming of potential cognitive limitations of the human staff, allowing action to be taken before the enemy can react.

Moreover, it is important to consider that a human commander and their staff can typically evaluate two or three COAs due to time and resource constraints. A system like COA-GPT can generate dozens of alternative COAs from the same initial configuration, each with a different maneuver structure, axis of effort, tactical risk, or fire priority. This ability to explore solutions is a crucial advantage in complex environments, enabling a broader comparative assessment by the staff and leading to the selection of the COA most aligned with the commander’s intent.82

Additionally, the incorporation of military doctrine into the prompts of COA-GPT ensures that the generated COAs align with standard operational principles, reducing reliance on the training or experience of individual planners. This automation standardizes the quality of the outputs, even under conditions of limited time, high stress, or varying professional backgrounds.

Finally, the reduction of the cognitive and logistical load on staff officers is a practical, significant advantage. In contested or degraded environments, where command posts must be distributed, mobile, or temporary, an automated MDMP helps reduce the amount of personnel needed while still maintaining a high level of planning capability. In modern warfare scenarios characterized by rapid movements, cyber disruption, and dynamic targeting of decision-making centers, this feature can ensure the survival and continuity of C2 operations.83

Proposing COA-GPT 2.0: An Architecture for the Uncertainty of War

The application of AI to the MDMP holds extraordinary potential, but its ultimate usefulness will depend on how well we guide its evolution with a strategic vision that accounts for operational needs, human cognitive limits, and the deep nature of warfare.84

For a system like COA-GPT to genuinely contribute to a battlefield decision-making advantage, it is essential to address and overcome some structural challenges. First, the architecture of the model itself must be rethought. COA-GPT 2.0 will need to incorporate uncertainty, not just as a technical variable, but as an essential element of the combat experience.85 This requires the integration of probabilistic and dynamic models capable of representing the partiality of information, the fog of war, the ambiguity of sources, and operational friction.86 Using models such as partially observable Markov decision processes (POMDPs), Bayesian networks, and Monte Carlo simulations can allow the system to generate COAs that are not evaluated based on absolute and deterministic scores, but accompanied by confidence estimates, risk intervals, and probabilistic assessments.87

At the same time, it will be crucial that the system does not propose rigid plans but adapts in real time to new information and human feedback, even during the execution of the COA. One of the structural limitations of COA-GPT is the discrete command mode, where the system assigns a single order to each unit at the start of the simulation, with no possibility of dynamic intervention during the scenario.88 While this approach is perfectly compatible with top-down planning logic, it becomes problematic in dynamic operational environments where conditions change rapidly.89 In the simulated environment of StarCraft II, reinforcement learning-based methods continuously update commands based on evolving tactics, whereas COA-GPT lacks this reactivity. The result is increased vulnerability to change, as evidenced by the higher rate of friendly force casualties compared to more granular control methods.

This limitation could be addressed by adopting a continuous planning logic with rolling time windows, transforming COA-GPT into an “always-listening” assistant during execution. This could be integrated with current C2 systems: Command Post of the Future (CPoF), Android Team Awareness Kit (ATAK), and Joint Operations Center Watch (JOCWatch), or a compromise between discrete control and dynamic autonomy could be adopted through preplanned contingency rules that enable predictive reactivity.90

In conclusion, by introducing these dynamic and flexible capabilities, a COA-GPT 2.0 could better reflect the unpredictability of warfare, enhancing its practical utility while also aligning with the inherent uncertainty and complexity that Clausewitz described.

A Doctrine, Organization, Training, Material, Leadership, Personnel, Facilities (DOTMLPF) Approach for the Way Ahead

To ensure a meaningful and responsible integration of AI into the MDMP, a comprehensive analysis across the DOTMLPF framework is required. This evolution must achieve technological enhancement to include fundamental cultural and procedural changes across our Services. Beyond the proposals presented here, which remain subject to revision in light of future research, the ultimate objective must be the development of an effective human–machine team (HMT). This concept rests on overcoming the long-standing debate over the primacy of humans versus machines, thereby paving the way for new levels of cognition, which is defined by General Brigadier Yossi Sariel (IDF) as “super-cognition.”91 The latter can indeed be achieved only through the synergistic integration of human and artificial intelligence: while machines are unsurpassed in the analysis of large volumes of data and rapid decision making, we have seen how they remain limited when it comes to addressing uncertain contexts, managing singular events characteristic of warfare, confronting ethical dilemmas, or creatively adapting to novel and uncodified situations. Conversely, humans, despite representing the bottleneck in stages requiring massive computational processes, are indispensable for defining the overall meaning of operations, navigating friction, and managing uncertainty, because “war is the realm of uncertainty” and the battlefield landscape continuously evolves.92 Therefore, only the genuine collaboration between computational capabilities and human judgment can ensure an effective and adaptive approach capable of providing a real advantage over adversaries.

Doctrine must be updated to formally incorporate AI systems as a core element of MDMP. This entails a clear delineation of roles, responsibilities, and the creation of effective HMT architecture. First, AI must not be described as a decision maker but as a tool for generating, refining, and testing COAs. Second, the doctrine should outline commander responsibilities in validating, questioning, or rejecting AI-generated outputs, especially under conditions of moral ambiguity or when collateral risks are involved. Furthermore, doctrinal revisions must address ethical guidelines for AI use, the acceptable thresholds of risk and uncertainty, and protocols for contested interpretations between human and machine assessments. It must instill the principle that the human commander or operator remains ultimately responsible, with AI serving as an advisory component that requires constant critical scrutiny.93

Third, to mitigate the specific risk of overfitting within the doctrinal domain, it becomes essential to integrate granular human control mechanisms, defining precisely in which areas each type is to be applied. The implementation of the human-in-the-loop (HITL) and human-on-the-loop (HOTL) framework represents a fundamental doctrinal necessity to counter the algorithmic brittleness identified by Hoffman and Kim, addressing the challenge that AI systems “work well under ideal conditions but quickly fail in the face of unforeseen changes in the environment or malicious interference.”94

HITL, characterized by deliberate and direct operator control over every critical AI decision, emerges as a doctrinal imperative in high-ambiguity operational scenarios, such as complex urban environments where the probability of misclassification is statistically elevated. Conversely, HOTL, which permits AI operational autonomy within predefined parameters while maintaining human supervisory and veto capabilities in real time, finds appropriate application in temporally constrained contexts such as anti-missile defense, where decision speed is critical for operational effectiveness. Doctrine must additionally incorporate principles of uncertainty quantification, requiring AI systems to provide quantitative measures of their decisional uncertainty, with predefined thresholds that automatically trigger escalation to human control when uncertainty exceeds critical parameters.95 An advanced HMT architecture, as proposed by recent research, represents a paradigm shift from the traditional binary human control/machine autonomy approach toward an adaptive model that dynamically calibrates supervision levels based on situational complexity and algorithmic confidence. However, as mentioned earlier, the basic principle in creating a new architecture must be that “humans remain in command, not just in the loop.”96

Organization must evolve by institutionalizing AI-integrated decision-making teams, where AI agents are effective active members.97 These could be composed by commanders, military staff, data analysts, AI interface specialists, and AI agents to ensure a rapid adaptation to the evolving situation.98 Moreover, such multidisciplinary human-machine collaboration would facilitate the AI output evaluation and interpretation through both military judgment and technical understanding. These organizational changes should also establish internal feedback loops to track the performance of AI recommendations, enabling iterative improvement and trust-building between humans and machines.99

Moreover, to mitigate the specific risks of overfitting and data poisoning through organizational reforms, the systematic implementation of specialized AI red teaming units emerges as an indispensable structural necessity.100 These organizational entities must operate through multidisciplinary approaches that combine machine learning expertise, operational field experience, and electronic warfare competencies to simulate multidimensional adversarial attacks and identify algorithmic cognitive vulnerabilities prior to operational deployment.101 Research conducted by the Swedish Defence Research Agency demonstrates how adversaries can compromise AI system integrity through data poisoning, rendering red teaming a continuous process rather than a static predeployment verification.102

It is also appropriate to specifically mention how the command posts of the future should evolve. Drawing from the consideration of Benjamin Jensen, the military command structures in place today remain largely reminiscent of those established during Napoléon Bonaparte’s era, despite two centuries of warfare evolution.103 Contemporary staff have grown unwieldy, struggling to manage the broader and more complex battlespace that now includes cyberspace, outer space, and information domains. This expansion has led to diminishing returns in coordination and operational effectiveness, exacerbated by vulnerabilities to precision strikes and electronic warfare, as starkly evidenced by Ukraine’s targeting of Russian command posts labeled the “graveyard of command posts.”104

Jensen advocates that AI, in the form of autonomous, goal-driven agents powered by large language models, offers transformative capabilities that can address these structural inefficiencies. By automating routine staff functions such as integrating disparate intelligence inputs, modeling threats, and even facilitating limited decision cycles, AI agents promise to reduce staff sizes while accelerating decision timelines and enabling smaller, more resilient command posts.105 Human operators remain essential for relevant decisions and ethical judgment, but AI augments their capacity to process vast information streams, generate diverse operational options, and focus on higher-level contingency analysis rather than administrative tasks.

Moreover, the envisioned Adaptive Staff Model, informed by ethnographic sociological approaches, integrates AI and human decision makers in continuous feedback loops, enabling dynamic plan adaptation in complex, Joint operational scenarios like those involving China-Taiwan contingencies.106 This model contrasts sharply with static, hierarchical staffs and emphasizes flexible, iterative command rather than linear planning. However, Jensen also cautions against several risks already discussed: reliance on generalized AI models that may lack domain-specific accuracy, and the danger of complacency among human users who might substitute AI outputs for critical reasoning.

These considerations perfectly complement what is advocated by Jim Storr’s insights from Something Rotten, as the imperative to rethink command structures aligns with his critique of bureaucratic inertia and overly complex decision making in modern militaries. Storr advocates for empowered, decentralized command with streamlined processes, a vision congruent with AI-enabled smaller, agile command posts.107 Together, these perspectives suggest that military command structures must evolve from cumbersome, industrial-age organizations into adaptive, AI-enhanced entities that maintain human judgment while harnessing computational power and flexibility to survive and be effective in future conflicts. 108

Training will be the decisive factor in this transformation. To establish an effective human-machine team, it is essential to initially train the individual parties and then their cohesive integration in a holistic manner. First, a commander or operator who lacks the ability to query, interpret, or critically engage with AI risks either overreliance or outright rejection. AI literacy must therefore become a core component of curricula in staff colleges, war colleges, and military academies.109 Officers and specialists must be educated not only in how to operate AI systems but also in how these systems work.110 To this end, it will be urgently necessary to proceed with a revision of the training plans of military schools, in alignment with the directives also highlighted by the White House’s report, Winning the Race: America’s AI Action Plan.111

Second, in addition to being directed toward commanders and AI system operators, training must also be extended to the system itself. As previously discussed regarding the risk of overfitting, it has been shown that this phenomenon may entail significant collateral effects in the context of military operations. To mitigate this risk, the AI system must therefore undergo dedicated training through the continuous and systematic integration of standard and mission-tailored datasets and adversarial examples, controlling the integration of synthetic data, and conducting rigorous validation against real-world data to prevent model collapse.112

Thirdly, and most importantly, it will be necessary to form the team. To create an effective team, as in a basic infantry unit, it is not sufficient merely to assemble individuals and equipment; rather, a specific training progression aimed at developing skills, cohesion, and mutual trust must be followed. These objectives may be pursued through the following concepts:

• Learning through synergetic learning, as a new process of mutual learning between humans and machines. By effectively combining the cognitive abilities of humans, which have driven global changes and transformations to date, with those of AI, which is potentially capable of analyzing every event from multiple perspectives, it becomes possible to achieve new and ambitious levels of analytical capability and inductive reasoning.113

• Organizing by introducing shared mental models (SMM) as a “pattern of cognitive similarity that enables them to anticipate one another’s needs and actions and to synchronize their work in a way that is synergistic toward meeting the team’s ultimate goals.”114 Introducing specific SMMs to define goals and processes, and outlining roles, tasks, and expectations, it is possible to improve cohesion and mutual trust by facilitating effective communication, reducing misunderstanding, and increasing predictability in interactions. It will lead to an overall increased HMT performance.115

• Testing and evaluating by conducting practical exercises, such as scenario-based COA testing with live troops, simulations, and wargaming. They will be the final critical events to validate AI-enhanced COAs and foster adaptive decision making, supported by specific benchmarks.116 These exercises should include feedback mechanisms to assess not only outcomes but especially the quality of human-AI interaction and mutual trust.117 Above all, as traditional training, the conduct of live force-on-force exercises, with both sides equipped with AI-enabled MDMP, could prove to be the decisive factor for success in real operations.118 Only such scenarios will in fact make it possible to effectively test the system under conditions of uncertainty; enable the system to learn from real-world rather than synthetic data; assess the effectiveness of HMT by identifying situations of overreliance or insufficient use; and evaluate commanders’ ability to manage the unpredictability of the operational environment, applying their “genius,” and demonstrating the usefulness or otherwise of AI support.119

Materiel must support the integration of AI into operational planning, particularly by minimizing black-box risk. This includes user-friendly interfaces for commanders, real-time battlefield data integration, and visualization tools that enhance transparency in how AI systems arrive at their recommendations. Such tools should allow commanders to trace the logic and assumptions behind AI outputs and provide input to refine them. Moreover, these systems must support feedback collection to train future iterations of AI, creating a continual improvement loop between field experience and model refinement.120

Starting from the aforementioned Army Laboratory Research studies, their Situation Awareness-based Agent Transparency (SAT) model seeks to mitigate the risks associated with black-box systems by establishing three distinct levels of situational awareness.121 The first level pertains to basic information such as the current state of the AI agent, and its goals, intentions, and proposed actions. The second level concerns the rationale underlying the agent’s actions, as well as potential environmental or situational constraints that may impact its operation. The third level involves the AI agent’s predictions regarding the consequences of its actions, including the likelihood of success or failure and the degree of uncertainty associated with those outcomes.122 Drawing from the SAT, the current progress made by Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) with Explainable Artificial Intelligence (XAI) demonstrates a significant leap forward in creating transparent, trustworthy AI partners. Initiated in 2015 and formally launched in 2017, the four-year DARPA XAI program successfully developed a portfolio of machine-learning algorithms and explanation techniques that balance predictive performance with interpretability, enabling end users to understand the strengths, weaknesses, and decision logic of AI systems.123 By 2021, XAI research teams had delivered the prototype Explainable Learners and psychological models of explanation, along with an open-source Explainable AI Toolkit (XAI Toolkit) that consolidates code, datasets, and evaluation frameworks for future development.124 In the military decision-making context, XAI advances support human-machine teaming by providing user-friendly interfaces that visualize both instance-level and model-level explanations, such as feature-importance heatmaps and decision-tree surrogates, allowing commanders to trace AI recommendations back to specific assumptions and data inputs.125 Furthermore, DARPA’s integration of after-action review modules, mirroring Army war gaming practices, could close the loop between battlefield feedback and model refinement, collecting commander and operator inputs to continually retrain and improve AI responses under realistic mission conditions.126

Leadership and education will shape the culture surrounding AI use.127 Future commanders do not need to be programmers, but they must understand how to engage with the machine, evaluate its suggestions critically, and maintain ethical judgment under uncertainty.128 Leadership development programs must emphasize cognitive flexibility and a willingness to scrutinize machine outputs. Bias mitigation must be taught not as a technical issue alone but as a leadership responsibility, recognizing that bias can stem not only from algorithms but also from how humans frame queries or interpret outputs.129 Although extensively addressed by numerous previous studies, it remains necessary to reiterate that leadership education must be centered on the foundational ethical and moral principles of international humanitarian law (IHL) and profession of arms. Empathetic IHL education is essential for learners to internalize the rules, appreciate their importance, and understand the requirements to apply them effectively.130

Indeed, beyond the metrics and probabilistic approaches of artificial intelligence, only human judgment will remain the decisive factor in ensuring the principles of distinction, military necessity, proportionality, and humanity.131

Although conceived prior to the advent of AI, the final principle—humanity—is self-explanatory in asserting why the centrality of human judgment in ultimate decision making is a nonnegotiable issue.132

Personnel policies should reflect the need for new skill sets. Roles such as AI operations advisors or human-AI interaction specialists may need to be formalized within staff structures. Incentivizing cross-training between military planners and data analysts can bridge knowledge gaps and reduce misinterpretation.133

Facilities must be reconfigured to support real-time, high-fidelity human-AI collaboration. In particular, training centers should allow Joint experimentation with AI during exercises, reinforcing the importance of physically colocated or networked human-machine teams. Moreover, facilities must include dedicated spaces for post-operation analysis where AI and human performance can be jointly assessed to improve future decision-making processes.

In summary, the successful integration of AI into military planning and command requires a systemic transformation. Mitigating bias in AI queries, understanding the limits of machine logic, and developing a robust training-feedback ecosystem are not technical challenges alone—they are doctrinal, cultural, and educational imperatives. Only through a deliberate DOTMLPF analysis can armed forces ensure that AI becomes a planning enabler instead of a source of risk or overdependence.

Conclusions

The article’s analysis of AI’s integration into MDMP, particularly through tools like COA-GPT, reinforces that warfare fundamentally remains a human endeavor. As Clausewitz, Dupuy, and the examination of historical examples like McNamara’s body count concept demonstrate, war is characterized by inherent uncertainty, friction, and the critical influence of intangible factors such as will, judgment, and human emotion. While AI offers extraordinary potential as a valuable tool, assisting in processing vast amounts of data, accelerating the OODA loop, and generating multiple courses of action, it cannot replace the human commander and staff.134 The technology’s limitations, including the risks of overfitting, the black-box problem, and the absence of Clausewitzian friction in its calculations, highlight the necessity of human oversight and critical thinking. In the words of Milan Vego:

There is a huge difference between using science and technology to enhance the combat potential of one’s forces and applying scientific methods in the conduct of war. Our knowledge and understanding of warfare is a science, but the conduct of war itself is largely an art. This will not change in the future regardless of scientific and technological advances. As in the past, the character of war will change, even dramatically, but the nature of war as explained by Clausewitz will not.135

The path forward for effectively leveraging AI in military planning, as suggested by the developmental trajectory of COA-GPT, demands a holistic approach. This approach extends beyond technological advancements to encompass cultural, educational, and doctrinal changes within the military. Ultimately, the true success of AI integration hinges on how effectively we prepare our commanders and their staff to exploit these tools, especially when the time-constrained nature of tactical situations may tempt them to over rely on AI-generated solutions. This includes instilling AI literacy, fostering critical thinking, and developing the ability to exercise sound judgment. We must learn to guide AI, challenge its outputs, and, when necessary, override its recommendations. By doing so, we can harness AI’s power to enhance our competitive advantage while ensuring that human intellect and acumen remain at the forefront of military decision making.136

Endnotes

1. Daniel Boffey, “Killing Machines: How Russia and Ukraine’s Race to Perfect Deadly Pilotless Drones Could Harm Us All,” The Guardian, 25 June 2025; “The Age of AI in U.S.-China Great Power Competition: Strategic Implications, Risks, and Global Governance,” Beyond the Horizon, 3 February 2025; and Nicholas Thompson and Ian Bremmer, “The AI Cold War That Threatens Us All,” Wired, 23 October 2018.

2. Kateryna Stepanenko, The Battlefield AI Revolution Is Not Here Yet: The Status of Current Russian and Ukrainian AI Drone Efforts (Washington, DC: Institute for the Study of War, 2025).

3. Framework for Future Alliance Operations, 2018 (Norfolk, VA: NATO Allied Command Transformation, 2018), 10–12.

4. Norman Hughes, Fleet Tactics and Naval Operations (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 2000), 29; and Tactics, Marine Corps Doctrinal Publication (MCDP) 1-3 (Washington, DC: Headquarters, Marine Corps, 2018).

5. H. W. Meerveld et al., “The Irresponsibility of Not Using AI in the Military,” Ethics and Information Technology 25, no. 14 (2023): https://doi.org/10.1007/s10676-023-09683-0.

6. A. Trevor Thrall and Erik Goepner, “Counterinsurgency Math Revisited,” CATO Institute, 2 January 2018.

7. Carl von Clausewitz, On War, ed. and trans. by Michael Howard and Peter Paret (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1976).

8. Alexis C. Madrigal, “The Computer That Predicted the U.S. Would Win the Vietnam War,” The Atlantic, 5 October 2017.

9. Karl Popper, The Logic of Scientific Discovery (London: Routledge, 1959), 1–20, 122–31; and Nassim Nicholas Taleb, The Black Swan: The Impact of the Highly Improbable (New York: Random House, 2007), 138–50.

10. David Hume, A Treatise of Human Nature (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1888), 92–104.

11. Intelligence Analysis, Army Techniques Publication (ATP) 2.33.4 (Washington, DC: Department of the Army, 2014), appendix b, 2.

12. John Boyd, Destruction and Creation (Fort Leavenworth, KS: U.S. Army Command and General Staff College, 1976).

13. B. H. Liddell Hart, History of the Second World War (London: Pan Books, 1970), 16–22; and Eliot A. Cohen and Phillips O’Brien, The Russia-Ukraine War: A Study in Analytic Failure (Washington, DC: Center for Strategic and International Studies, 2024).

14. Clausewitz, On War, book II, chap. 2.

15. Hughes, Fleet Tactics and Naval Operations, 195–96.

16. Gordon W. Prange, At Dawn We Slept: The Untold Story of Pearl Harbor (New York: Penguin Books, 1982), 725–37; and Max Hastings and Simon Jenkins, The Battle for the Falklands (London: W. W. Norton & Company, 1983), 267–89.

17. Mark Bowden, Hue 1968: A Turning Point of the American War in Vietnam (New York: Grove Press, 2018), 34–42.

18. Robert S. McNamara, In Retrospect: The Tragedy and Lessons of Vietnam (New York: Vintage Books, 1996), 3.

19. J. T. Correll, “The Confessions of Robert S. McNamara,” Air & Space Forces Magazine, 1 June 1995; and K. Eschner, “How Robert McNamara Came to Regret the War He Escalated,” Smithsonian Magazine, 29 November 2016.

20. Alain C. Enthoven and K. Wayne Smith, How Much Is Enough?: Shaping the Defense Program, 1961–1969 (Santa Monica, CA: Rand Corporation, 2005), 71–72.

21. John L. Gaddis, Strategies of Containment: A Critical Appraisal of American National Security Policy during the Cold War (New York: Oxford University Press, 1982), 255–58.

22. Kenneth Cukier and Viktor Mayer-Schönberger, “The Dictatorship of Data,” MIT Technology Review, 31 May 2013.

23. Matthew Fay, “Rationalizing McNamara’s Legacy,” War on the Rocks, 5 August 2016.

24. Douglas Kinnard, The War Managers (Hanover, NH: University Press of New England, 1977), 74.

25. Kinnard, The War Managers, 75.

26. Andrew Marshall, “An Overview of the McNamara Fallacy,” Boot Camp & Military Fitness Institute, 31 December 2024.

27. David Kilcullen, The Accidental Guerrilla: Fighting Small Wars in the Midst of a Big One (Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 2009), 25–27.

28. In strategic planning, the three fundamental elements proposed in Arthur Lykke’s framework are represented by: ends, which refer to the objectives or desired outcomes to be achieved; ways, meaning the methods, strategies, or courses of action employed to use the available means in order to attain the desired results; and means, which encompass the resources and tools, both tangible and intangible, available to the decision maker for achieving the objectives. Harry R. Yarger, “Toward a Theory of Strategy,” in U.S. Army War College Guide to National Security Policy and Strategy, 2d ed. (Carlise, PA: U.S. Army War College, 2006), chap. 8, 107–13.

29. Nazanin Azizian, Easier to Get into War Than to Get Out: The Case of Afghanistan (Cambridge, MA: Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs, 2021).

30. Edward N. Luttwak, The Pentagon and the Art of War: The Question of Military Reform (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1985), 23.

31. John J. Mearsheimer, “Assessing the Conventional Balance,” International Security 13, no. 4 (Spring 1989): 5–53, https://doi.org/10.2307/2538780.

32. Clausewitz, On War, book II, chap. 2, 194.

33. Christopher A. Lawrence, War by Numbers: Understanding Conventional Combat (Lincoln: Potomac Books, an imprint of University of Nebraska Press, 2017), 30–31.

34. Shawn Woodford, “Dupuy’s Verities: Combat Power =/= Firepower,” The Dupuy Institute, 12 May 2019.

35. Woodford, “Dupuy’s Verities.”

36. LtCol Z. Jobbagy, “The Efficiency Aspect of Military Effectiveness,” Militaire Spectator 178, no. 10 (2009): 431–39.

37. Gerhard Geldenhuys and Elmarie Botha, “A Note on Dupuy’s QJM and New Square Law,” ORiON 10, nos. 1–2 (1994): 45–55, https://doi.org/10.5784/10-0-455.

38. Geldenhuys and Botha, “A Note on Dupuy’s QJM and New Square Law,” 50–51.

39. Joshua M. Epstein, The Calculus of Conventional War: Dynamic Analysis without Lanchester Theory (Washington, DC: Brookings Institution Press, 1985).

40. Joshua M. Epstein, “Dynamic Analysis and the Conventional Balance,” International Security 12, no. 4 (Spring 1988): 154–65.

41. Epstein, “Dynamic Analysis and the Conventional Balance.”

42. Epstein, “Dynamic Analysis and the Conventional Balance.”

43. U.S. Ground Forces and the Conventional Balance in Europe (Washington, DC: Congressional Budget Office, 1988), 83.

44. U.S. Ground Forces and the Conventional Balance in Europe.

45. Leo Tolstoy, War and Peace (Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press; originally 1869), book X, chap. 7, 1667.

46. Tolstoy, War and Peace, book II, chap. 17, 411–12.