https://doi.org/10.21140/mcuj.20251602001

PRINTER FRIENDLY PDF

EPUB

AUDIOBOOK

Abstract: The unmanned combat vehicle, or combat drone, is making its presence felt on battlefields around the world. Much like the tank and aircraft in World War I, drones have been employed individually or in small groups to conduct reconnaissance and precision strikes. But the Department of War’s renewed focus on large-scale combat operations warrants new thought regarding drone employment. This article is not a treatise on the technical aspects of unmanned combat vehicles, but instead a proposal for drone employment en masse as an operational maneuver force. It uses historical examples of operational maneuver, recent drone operations, and imagination to generate a new concept for combat drone employment: the swarm maneuver group. The high mobility and mass of the proposed swarm maneuver group offers the Joint Force a new means of conducting persistent deep operations to disintegrate adversary antiaccess/area-denial (A2/AD) systems and enable Joint operational access to theaters. The aim of this article is to generate creative thought, debate, and purposeful action regarding the offensive employment of unmanned combat vehicles in large-scale combat operations.

Keywords: swarm maneuver group, unmanned systems, military innovation, antiaccess/area-denial, A2/AD, Joint Force, swarm tactics, combat drone doctrine

Introduction

The United States faces the prospect of a multifront war against several rogue adversaries and a peer, which is arguably the most existential threat the United States has faced in its history, the People’s Republic of China. As highlighted in the Joint Operational Access Concept (JOAC), these adversaries have robust antiaccess, area-denial (A2/AD) systems combining the tyranny of distance with the lethality of long-range reconnaissance-strike complexes. They seek fait accompli victories, believing they can achieve political objectives with armed incursions before the United States and its allies can mass a credible military response. Simultaneously, shortfalls in recruiting and retention efforts and large numbers of citizens unfit for service constrain the size of the U.S. military. While the United States has the best servicemembers in the world and many exquisite capabilities, the Services are spread thin and have constrained mobilization potential.

During the interwar years, figures such as J. F. C. Fuller, Georgii Samoilovich Isserson, Heinz Guderian, and William L. “Billy” Mitchell grappled with a similar dilemma: How can the offense, constrained by peacetime budgets and force sizes, overcome the immense depth and firepower of the modern defense at the outset of the war? Two new combat platforms, tanks and aircraft, had achieved tactical successes in World War I but in limited and auxiliary roles. Armor served as infantry support, and aircraft in reconnaissance and air-to-air combat.

In the 1920s and 1930s, these visionaries and others developed doctrine for the offensive employment of armor and airpower en masse to achieve not just tactical breakthroughs but operational-level ruptures of entire defensive systems. They used history, combat experience, training, and imagination to develop new theories of warfare, often before tanks and aircraft of sufficient quality existed to validate their proposals. It was not until the 1939–40 German invasions of Poland and France that their hypotheses were substantiated. Tanks, aircraft, operational design, and offensive-minded leadership outmaneuvered and defeated the epitome of defensive depth and firepower, the Maginot Line.

A new offensive means, the unmanned combat vehicle (UCV), is making its presence felt on battlefields across the world. Just like tanks and airplanes in World War I, they are spread throughout the force in driblets, conducting aerial reconnaissance and isolated strikes. But as the German general Heinz Guderian said, “You hit somebody with your fist and not with your fingers spread.” The United States requires a highly mobile force with sufficient mass to conduct, as stated in the Joint Concept for Entry Operations: “opportunistic and unpredictable maneuver in and across multiple domains, establishing local superiority at multiple entry points to gain entry and achieve objectives.”1

This article proposes a new method of using UCVs to meet many of the requirements outlined in the JOAC—the swarm maneuver group. This is not a treatise on the technical aspects of UCVs but instead a theory of their organization and employment en masse as a deep maneuver force synthesized from historical examples, recent tactical actions, and imagination. The aim is to generate creative thought, debate, and purposeful action regarding the offensive employment of UCVs to disintegrate adversary A2/AD and decision making and enable Joint entry operations.

Mongols, Napoléon, Vicksburg, and Operational Maneuver Groups: Historical Precedence for Operational Maneuver

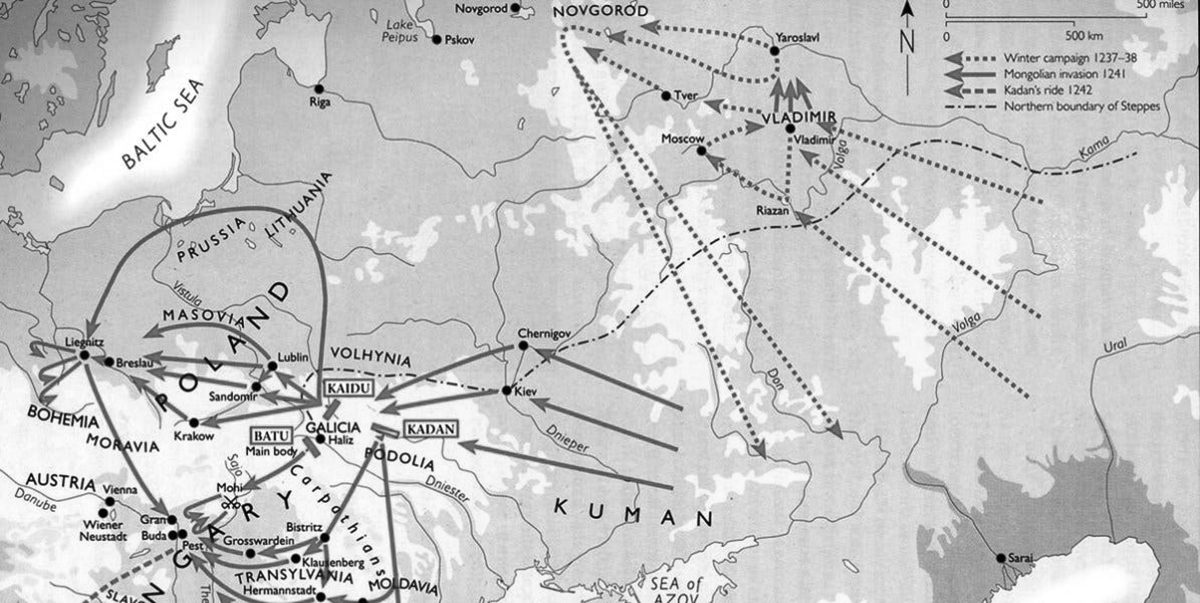

During 1240–41, the Mongols invaded Eastern Europe with the intent of subjugating Hungary. A simultaneous operation in Poland led by the Mongol commander Subutai supported the Hungary operation by preventing the opposing forces from concentrating combat power. The Mongols divided their army into four columns, each of which had two to three tumens (divisions) of 10,000 horsemen. Column commanders had the freedom to plan their own route and tactical actions, so long as they adhered to the operational timeline and theater strategy.2

Mongol commanders bypassed enemy strongpoints and only attempted to storm fortresses once. If resistance was strong, they moved on. By raiding vulnerable yet critical parts of their enemy’s civil-military system—agriculture, small towns, etc.—they consolidated gains while avoiding enemy strengths. When the opportunity to defeat their enemy in detail emerged, as at the Battles of Mohi and Liegnitz (April 1241), the Mongols used speed, deception, swarming tactics, and envelopments to defeat the slower European forces.3

Map 1. Map of the Mongol invasion of Eastern Europe

Note the use of multiple, converging columns.

Source: Derek Davidson, “Today in European history: the Battle of Mohi (1241),” Foreign Exchanges, 11 April 2019.

Six centuries later, during the American Civil War, commanders on both sides employed large, mobile groups of horse cavalry in raiding operations. In late 1862, Union major general Ulysses S. Grant initiated his first campaign to capture the Confederate river fortress of Vicksburg, attempting an overland march east of the Mississippi River. Lieutenant General John C. Pemberton, the Confederate commander, launched two deep cavalry raids on Grant’s supply lines while keeping his main forces in Vicksburg. The first Confederate raid, led by Nathan Bedford Forrest, destroyed rail junctions in the vicinity of Jackson, Mississippi, roughly 200 kilometers (km) behind Grant’s forces, severing Union wire communications and supply lines.4 Nearly simultaneously, General Earl Van Dorn led 3,500 Confederate cavalry in three columns in a raid on Grant’s main supply depot at Holly Springs. Van Dorn’s forces quickly overcame the defenders and destroyed the Union depot.5 Grant’s attempt to use support area forces to neutralize the Confederate raiders failed and, with the loss of his lines of supply and communication, he was forced to temporarily regroup at Memphis, Tennessee.

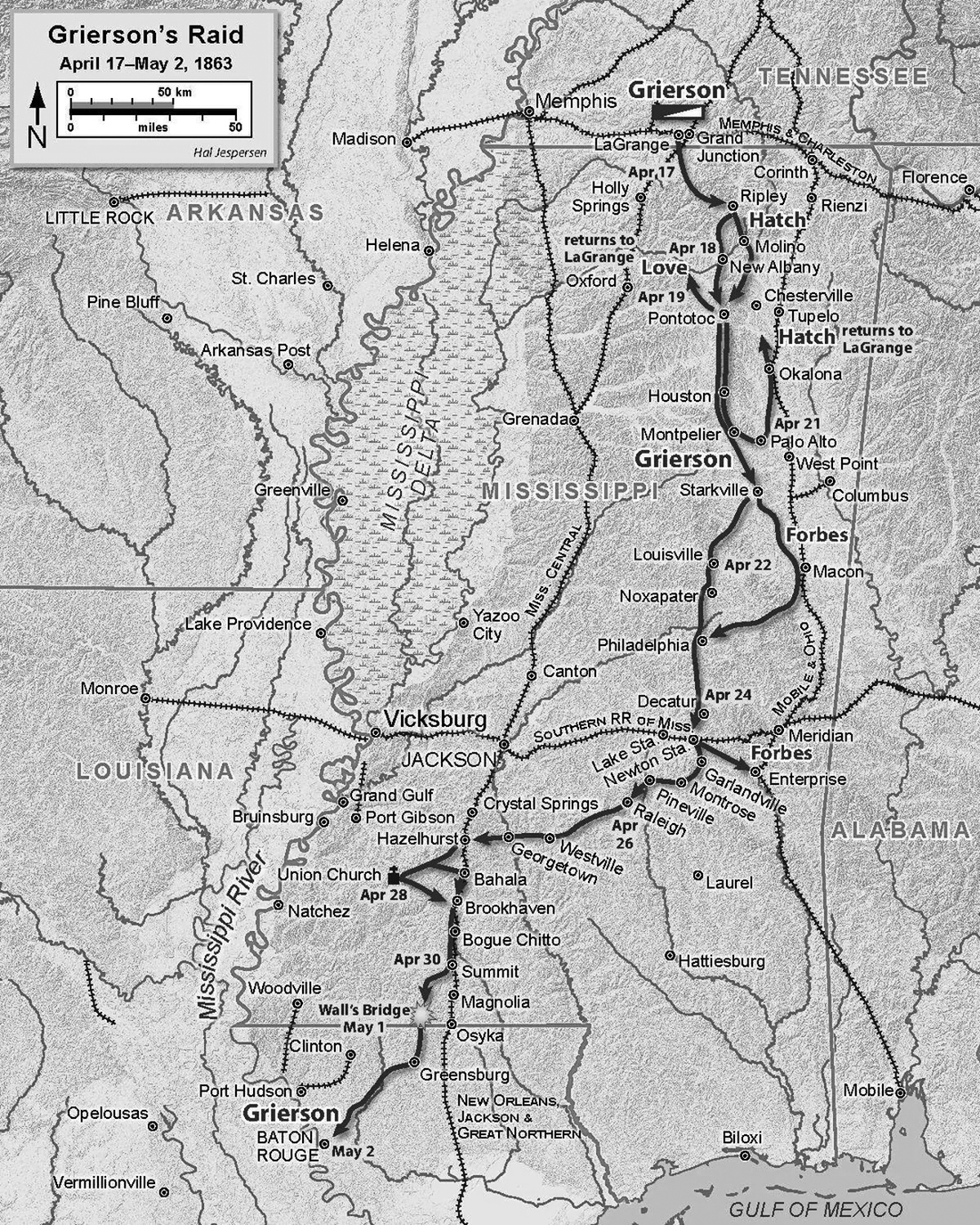

In April 1863, Grant launched a second Vicksburg Campaign, this time seeking to cross the Mississippi River south of the fortress. On 17 April, he dispatched a brigade of 1,700 cavalry and six small guns under Colonel Benjamin H. Grierson with the dual purposes of distracting Pemberton from Grant’s movement and fixing Confederate forces, primarily their cavalry, away from the Union crossing site. Grierson avoided Confederate strengths and attacked weaknesses. He routinely detached subordinate elements to move on separate axes and made numerous feints to confuse the Confederates as to his real objective. He also employed an advanced reconnaissance force wearing Confederate uniforms to provide early warning of enemy forces.6

Map 2. Grierson’s raid in support of Grant’s Vicksburg Campaign

Source: Mike Phifer, “Grierson’s Raid in Support of Grant’s Vicksburg Campaign,” Warfare History Network, accessed 24 September 2025.

For 16 days, Grierson covered 970 km of enemy territory and destroyed more than 80 km of Confederate railways and telegraph wire.7 More importantly, he fixed a division of Confederate combat power in a secondary sector while Grant crossed the Mississippi. His actions highlight the outsized operational effects that highly mobile maneuver forces can have on opposing armies as well as their commanders’ minds.

During the 1945 Soviet invasion of Japanese-held Manchuria, the Red Army employed forward detachments of combined-arms mechanized divisions, corps, and armies to execute deep penetrations of Japanese positions and seize objectives that supported follow-on-force advances. These forward detachments operated jointly with Soviet air, airborne, and amphibious groups to penetrate up to 800 km into Manchuria and disintegrate Japanese command and control (C2) and transportation systems.8 During the Cold War, Soviet military theorists used the forward detachment model to conceptualize the operational maneuver group. An operational maneuver group is:

a highly mobile, combined arms formation intended to operate ahead of the main body of Warsaw Pact frontal forces. It would be committed, through a gap created in enemy defenses by first echelon forces, to conduct a “deep operation” in the enemy rear.9

Operational maneuver groups would disrupt North Atlantic Treaty Organization’s (NATO) C2, neutralize airfields, seize mobility corridors, and threaten enemy capitals in order to enable the success of follow-on-forces. Their employment would, ideally, force an early decision in conflict while avoiding NATO’s high-readiness frontline units and succeeding before NATO could mobilize additional forces or employ nuclear weapons.

Recent Developments in Unmanned Combat Vehicles

Mavericks of armored and aerial warfare during the interwar years pulled from contemporary conflicts and training exercises to develop their theories and doctrine. They also accounted for technical improvements in tanks and aircraft, the five most critical of which were described by Soviet brigade commander Georgii Isserson as increased speed, improved firepower, greater range, higher mobility, and mass production. Isserson particularly emphasized mobility, stating, “Everything that increases mobility enriches offensive potential. Defensive potential can be increased only by increasing firepower.”10 A treatise on the many technical developments of UCVs exceeds the breadth of this article and belongs to experts in the field but suffice it to say the five critical factors described above apply to UCVs today. The following section instead focuses on the performance of UCVs in recent conflicts, wargames, and training exercises as a means of examining their future potential.

Abqaiq-Khurais Attack

On 14 September 2019, Iran attacked Saudi oil refineries at Abqaiq and Khurais with a barrage of 18 loitering munitions and several cruise missiles.11 These drones and missiles likely traveled 300–500 km and reached their targets despite the presence of Saudi antiaircraft guns and a Patriot missile defense system.12 This small tactical action had strategic effects on the global petroleum supply chain and highlights the potential of future UCV attacks on national logistics infrastructure. The attack also demonstrated the benefits of combining loitering munitions with more expensive and capable missiles.

Second Nagorno-Karabakh War

During 44 days in 2020, Azerbaijan inflicted a significant military defeat on Armenia in the Second Nagorno-Karabakh War. It was the first war to feature mass-employment of unmanned systems executing reconnaissance strike complexes. Azerbaijan initiated the war with a rapid suppression of enemy air defense operation, destroying 50 percent of Armenia’s air defense and 40 percent of its artillery in the first 15 minutes of the war.13 Using remotely piloted biplanes to trigger Armenian radars and air defenses to engage, Azerbaijan loitering munitions and armed UAVs subsequently destroyed the exposed air defense systems. Azerbaijan combined these attacks with electronic warfare disruption of Armenian radar and artillery suppression of defensive positions, enabling UAV freedom of maneuver.14

Azerbaijani commanders established reconnaissance strike zones (RSZ), a three-dimensional permissive fire control measure allowing human-out-of-the-loop (HOOTL) engagements by UCVs. HOOTL refers to “a weapon system that, once activated, can select and engage targets without further intervention by a human operator.”15 Satellites, reconnaissance UAVs, and small teams of clandestine Azerbaijani forces conducted target identification in RSZs for both UAVs and conventional fires.16 Azerbaijan first destroyed key Armenian defensive network components (air defense, electronic warfare, C2, and fires), then attrited ground maneuver forces and interdicted supply lines.17

Simultaneously, a three-corps ground offensive exploited an Armenian defense fixed throughout its depth by RSZs. Two Azerbaijani corps fixed the Armenians along the northern portion of the front allowing Azerbaijan’s main effort, the II Corps and a special forces element, to penetrate Armenians defenses in the south and capture the critical city of Shusha. Also of note, thick fog grounded UCVs for two days during the conflict, displaying the limitations of these systems.18

Russo-Ukrainian War

The ongoing Russo-Ukrainian War is emerging as a testing ground for UCVs akin to what the Spanish Civil War was for the Wehrmacht’s armored and air forces before World War II. On 29 October 2022, the Armed Forces of Ukraine (AFU) launched a multidomain swarm attack on the Russian Black Sea Fleet docked at Sevastopol, Crimea. In total, 16 unmanned systems—9 UAVs and 7 unmanned surface vehicles (USVs)—traveled 160 km across the Black Sea to the Russian port.19 Reports on the success of the attack vary, but it likely damaged the Russian fleet’s flagship and a minesweeper while losing all 16 drones.20 While not operationally significant, this marked the first time a swarm of UAVs and USVs executed a joint strike on an enemy port and demonstrates the potential for future littoral swarm employment en masse.

UCV experimentation and proliferation continued during the relative operational stalemate of 2023–25. First, Ukraine expanded its deep-strike campaign against Russian infrastructure with drone attacks hundreds of kilometers deep in Russian territory.21 Second, in December 2024, the Battle of Lyptsi became the first all-robotic air-land offensive in history. Although only a small tactical engagement with minimal consequence in the war, Lyptsi may one day be remembered similarly to the first insignificant uses of tanks on World War I’s Western Front.22

Taiwan Wargames

Rand highlighted the potential for large numbers of low-cost, reusable UAVs in support of the defense of Taiwan in their publication, Operating Low-Cost, Reusable Unmanned Aerial Vehicles in Contested Environments. The UAVs in the wargame were a mix of XQ-58 Valkyries (8.9 hours loiter time, 9,362 km range) and a smaller “kitten” variant (5.6 hours loiter time, 6,182 km range), one-tenth the size of the Valkyrie. The defenders tasked the UAV group with maintaining intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance over the strait to enable the accurate delivery of Harpoon antiship missiles against People’s Republic of China (PRC) vessels. To accomplish this, the UAVs established a 10,000-square-kilometer formation of 500 UAVs flying over the Taiwan Strait at 30,000 feet. They communicated and shared intelligence using a mesh communications network and a chain of relays.23 The UAVs enabled the defenders to destroy more than 70 percent of the PRC fleet.24 The wargamers mitigated the effects of enemy jamming by employing the UAVs at high altitudes, though the article admitted lower-altitude and overland employment would increase the success of enemy jammers.25

OFFensive Swarm-Enabled Tactics

Since 2017, the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) OFFensive Swarm-Enabled Tactics (OFFSET) program has conducted coding, simulations, and field experiments focused on offensive drone swarm employment. Per DARPA’s website, the stated objective of the program is to develop ground and air drone swarms that enable infantry units to seize eight square city blocks in four to six hours. The drone swarms, up to 250 UCVs in size, execute tactical enabling operations such as reconnaissance and surveillance and cordon and combine both UAVs and unmanned ground vehicles (UGV). The program completed its sixth urban field experiment in late 2021 and participated in the U.S. Army’s Project Convergence 2022.26

The Swarm Maneuver Group

The swarm maneuver group is a highly mobile, combined arms, unmanned formation intended to enable the Joint Force to achieve cross-domain synergy. Swarm maneuver groups employ AI-enabled swarm tactics, converging mass, and multidomain capabilities to conduct deep maneuver to disintegrate adversary systems and decision making at both the tactical and operational levels. Swarm maneuver groups do not achieve decisive results on their own; they enable predominately manned forces to gain operational access and close with and destroy adversaries from a position of advantage.

Swarm tactics are coordinated and harmonious attacks on an objective from multiple directions. Swarm tactics require economy of force: attack with enough combat power to overwhelm the defender’s ability to respond, but not so much as to produce target overkill. For example, an entire swarm maneuver group regiment may be required to neutralize an aircraft carrier, while a single UCV may destroy a fuel truck.

Converging mass is the rapid assembly of dispersed forces at decisive points and moments, followed by the immediate disaggregation of forces once the desired effect is achieved. When not massed, swarm maneuver groups move in multiple, dispersed (horizontally and vertically) columns and routinely make feints and direction changes to confuse adversaries as to their intended objectives. Columns are mutually supporting, close enough to allow converging mass as opportunities present themselves.

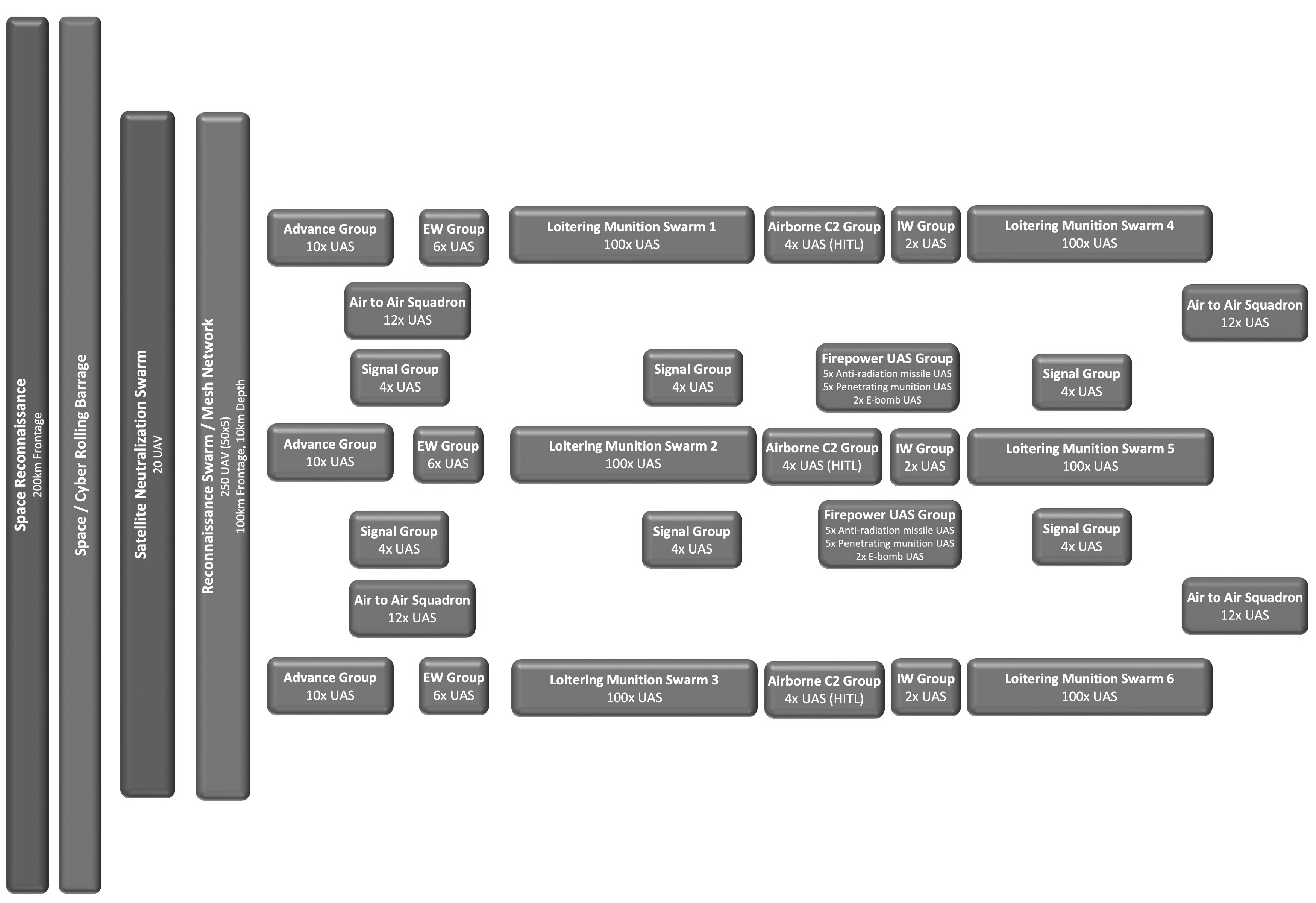

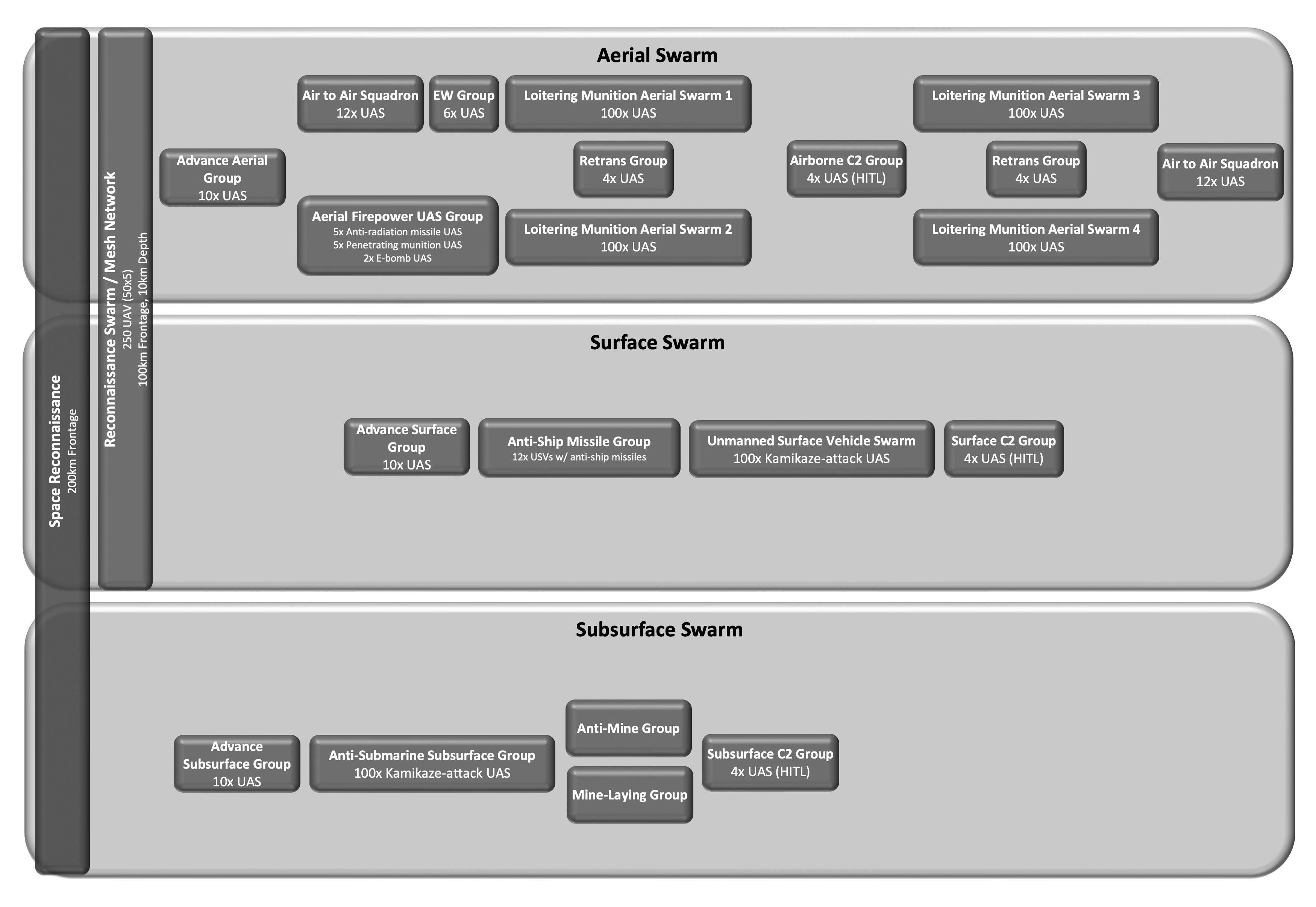

Organization

This article presents two potential small maneuver group types: continental and littoral. Continental small maneuver groups operate in the air domain and consist entirely of UAVs. UGVs are not incorporated in the below design to maximize mobility and speed. Littoral small maneuver groups are specially designed to operate in coastal areas and consist of UAVs, USVs, and unmanned subsurface vehicles (USSVs). While the graphical depictions of small maneuver groups in this article are organized and symmetric for sake of clarity, in actual operations small maneuver groups will maneuver fluidly to complicate adversary targeting.

Small maneuver groups are employed in three sizes: regimental (supports maneuver division or Joint equivalent), division (supports maneuver corps or Joint equivalent), and corps (supports army or theater army or Joint equivalent). The continental small maneuver group regiment contains 1,012 total UAVs organized into nine subgroups and can conduct combined arms operations on up to three lines of operation. The littoral small maneuver group regiment has 728 UCVs organized into nine subgroups, and it is designed to combine aerial, surface, and subsurface swarms on a single line of operation. A small maneuver group division consists of three regiments, and a small maneuver group corps consists of three divisions.

The subgroups are broken down into two categories: swarm groups and enabling groups. Swarm groups are the small maneuver group’s main firepower: mass-produced UCVs employed in kamikaze swarm tactics or aerial and subsurface minefields to deny enemy maneuver. Enabling groups are more exquisite UCVs that use combined arms effects to allow the swarm groups to accomplish their assigned task. The subgroups are as follows:

• Satellite neutralization group (SNG): UAVs that maneuver in low Earth orbit with conventional or nuclear propulsion. One SNG supports up to one small maneuver group corps.

° Task: Neutralize enemy low-Earth orbit satellites through electronic attack or affixing to satellites and propelling them back to Earth.

° Purpose: Deny adversary space-based intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance, C2, and precision-navigation and timing.

• Reconnaissance swarm: Mesh network UAVs modeled on the above Rand wargame.

° Task: Wide-area intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance queued by Joint reconnaissance.

° Purpose: Queue swarm columns onto enemy forces or objectives. Enable accurate Joint fires.

• Advance group: UCVs with enhanced intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance capabilities. Ideally disguised to appear as enemy systems or nature.

° Task: Aerial reconnaissance.

° Purpose: Provide early warning to a small maneuver group.

• Swarm group: Groups of 100 relatively cheap, expendable kamikaze-

style UCVs.

° Task: Employ swarm tactics to destroy, neutralize, suppress, or disrupt enemy forces.

° Purpose: Nested with Joint task force purpose.

• Firepower group: Standoff engagement UCVs armed with penetrating munitions, antiradiation missiles, and electromagnetic pulse bombs.

° Task: Support and attack by fire. Precision strikes.

° Purpose: Enable swarm group maneuver.

• C2 group: Remotely piloted UCVs capable of controlling or retasking small maneuver groups.

° Task: Provide human-in-the-loop C2.

° Purpose: Enable human C2 of small maneuver groups.

• Signal group: UCVs designed to enhance connectivity in degraded areas.

° Task: Data sharing and communication between swarm groups and to Joint task force headquarters.

° Purpose: Enable small maneuver group C2.

• Electronic warfare group: UAVs capable of electromagnetic jamming, deception, and reconnaissance.

° Task: Suppression and deception of enemy radars and precision munitions. Electromagnetic reconnaissance.

° Purpose: Disrupt adversary air defenses. Allow small maneuver group freedom of maneuver.

• Information warfare group: Signals intelligence UAVs capable of broadcasting via digital networks.

° Task: Deliver pro-U.S. information and messaging to digital devices.

° Purpose: Incite civil resistance against adversaries.

• Air-to-air group: Unmanned or remotely piloted fighter aircraft, likely models that are currently or soon to be retired.

° Task: Combat air patrol.

° Purpose: Defeat enemy aviation.

• Antimine group: USSVs designed to defeat enemy subsurface obstacles.

° Task: Reduce subsurface obstacles.

° Purpose: Enable subsurface swarm freedom of maneuver.

Figure 1. Horizontal plane view of a continental small maneuver group regiment

Source: courtesy of the author, adapted by MCUP.

Various small maneuver group organizations should be tested in wargames and virtual environments such as the Warfighter Simulation program. If validated, further wargaming should refine the capabilities and design of the small maneuver group. Small scale field experiments should follow, then integration with the Joint Force in free play excises such as the National Training Center at Fort Irwin and Marine Air Ground Combat Center at Twentynine Palms.

Small maneuver groups must be forward postured to enable combatant commanders to employ them on day one of a crisis or conflict. The UCVs should be stored in distributed and concealed locations or on mobile platforms and hardened against both kinetic and electronic attack. Small maneuver groups should be given HOOTL permission to scramble if adversary first strike operations are detected.

Figure 2. Vertical plane view of a continental small maneuver group regiment

Source: courtesy of the author, adapted by MCUP.

Small Maneuver Group Employment

Due to their high mobility, small maneuver groups are ideal maneuver forces to conduct indirect approaches in support of main body forces on more direct lines of operation. Harmonization between the two forces is critical. For example, a small maneuver group should begin a raid or saturation attack on an adversary while friendly main body forces enter the adversary’s primary engagement area. A great historical example of unity of purpose is Grierson’s raid enabling Grant’s crossing of the Mississippi.

The second tenant is early and rapid offensive employment. Everyone has a plan until they get punched in the mouth. Small maneuver groups are forward stationed to be able to counterattack aggressors on day one of a conflict to prevent a fait accompli. Small maneuver groups should be programmed to execute operations in accordance with established operation plans on human approval or engagement criteria being met. In more deliberate operations, small maneuver groups typically operate forward of manned Joint Force formations.

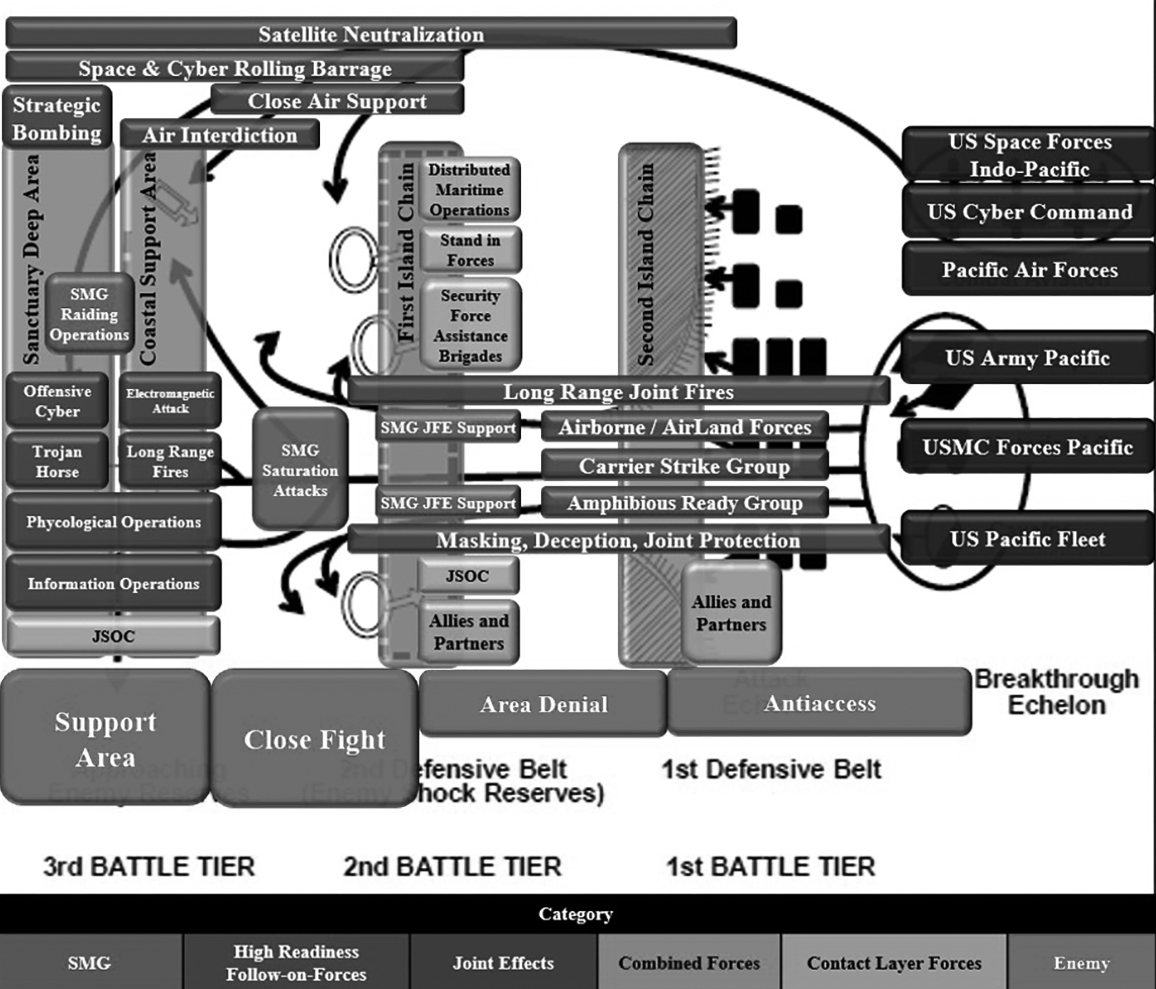

The third tenant is cross-domain synergy and weaponeering. Small maneuver groups do not achieve strategic success on their own; they enable cross-domain synergy in the Joint Force. In the diagram below, forward stationed U.S. forces, allies, and partners fix and disrupt adversaries in the contact layer. Joint all-domain fires, masking, protection, and deception enable small maneuver group penetration or infiltration of A2/AD. Satellite neutralization groups, space and cyber rolling barrages, trojan horse attacks, and long-range Joint fires enable small maneuver group freedom of maneuver in enemy rear areas. Small maneuver group raids and saturation attacks, combined with Air Force strategic bombing and air interdiction, disintegrate A2/AD from within. These attacks, combined with psychological and information operations, disrupt adversary decision making and exploit vulnerabilities in authoritarian regimes. These cumulative effects inflict system paralysis on adversaries, enabling the operational access or forcible entry of high readiness follow-on-forces such as airborne units, carrier strike groups, and amphibious ready groups.

Figure 3 is an example Joint task force penetration of the PRC’s A2/AD system in the Western Pacific, overlayed on Isserson’s deep operation concept.27 Note SMG saturation attacks, raids, and Joint forcible entry operations disintegrate the PRC’s A2/AD systems and enable Joint task force freedom of maneuver.

Figure 3. Example of Joint task force penetration of the PRC’s A2/AD system in the Western Pacific, overlayed on Georgii Isserson’s deep operation concept

Source: base image from Georgii Isserson, The Evolution of Operational Art, trans. Bruce W. Menning (Fort Leavenworth, KS: Combat Studies Institute Press, 2013), 35, adapted by MCUP.

Small maneuver groups allow Joint task force weaponeering: exquisite Joint fires focus on the highest-value and most protected enemy targets while small maneuver groups mass on more vulnerable yet critical points, such as C2 and logistics. During Operation Desert Storm, there were more than 40,000 ground targets prosecuted during a 43-day campaign by an Air Force larger than today’s. Against the PRC, there would likely be 100,000 or more such targets.28 Instead of gradual attrition of a high value target list, small maneuver groups provide the mass to attack several decisive points simultaneously.

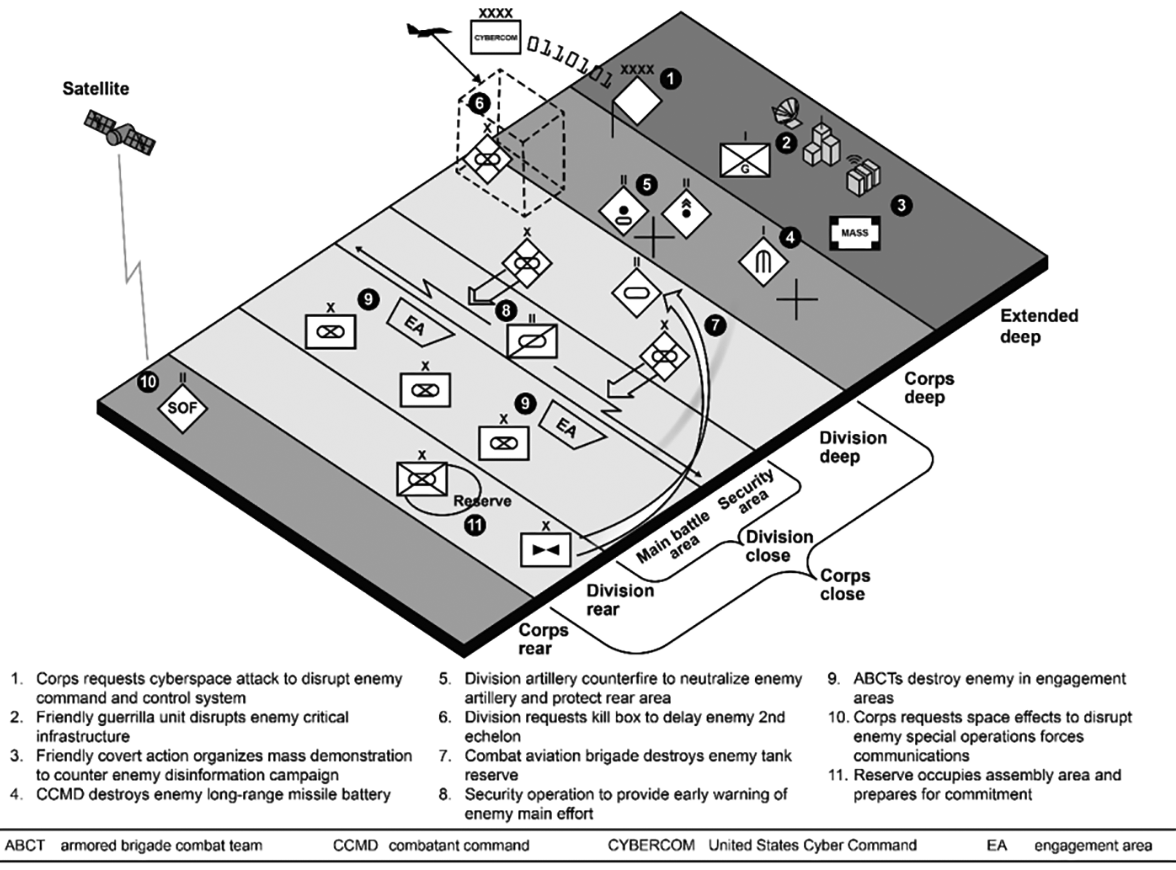

The fourth requirement for a small maneuver group’s employment is the establishment of reconnaissance strike zones: RSZs are three-dimensional permissive fire control measures allowing HOOTL engagements by autonomous systems. AI-enabled identification, friend or foe algorithms, and engagement criteria allow UCVs to decide, detect, deliver, and assess at machine speeds, reducing kill chains to seconds. To shorten kill chains, Joint task force fires should not require clearance to fire into RSZs occupied solely by small maneuver groups.

Figure 4. A small maneuver group reconnaissance strike zone overlayed on a notional U.S. Army operational framework for offensive operations

Source: base image from Operations, Field Manual 3-0 (Fort Belvoir, VA: U.S. Army Publishing Directorate, October 2022), 6-44, adapted by MCUP.

The fifth and final tenants of small maneuver groups are their risk and expendability: small maneuver groups must be primarily or entirely unmanned and viewed as expendable. This enables Joint force commands (JFCs) to execute audacious, high-risk, high-reward operations against adversaries that may result in unacceptable casualties to manned formations.

The three basic methods of small maneuver group employment are:

1. Raiding: Raiding operations are modeled on Mongol and U.S. Civil War cavalry raids and Soviet operational maneuver groups (OMGs). Small maneuver groups avoid enemy strengths and attack weaknesses such as enemy headquarters, C2 nodes, telecommunications infrastructure, depots, logistics infrastructure, electric plants, and other lightly defended but critical components of an enemy’s warfighting potential. Raiding operations disintegrate enemy A2/AD and C2, interdict sustainment, demoralize adversaries, and disrupt their decision cycles. Small maneuver groups threaten every inch of an adversary’s civil-military system, forcing enemies to divert combat power to support areas or let the small maneuver group run amok in their rear areas. Raiding small maneuver groups persist in the enemy’s support zone as long as sustainment capabilities allow.

2. Saturation attacks: The Abqaiq-Khurais and Sevastopol attacks provided the inspiration for small maneuver group saturation attacks. In this employment, small maneuver groups mass against strongly defended yet critical adversary system components such as airfields, ports, air defense batteries, missile groupings, and enemy reserves. If possible, small maneuver groups use deception and converging mass to achieve surprise prior to beginning saturation attacks. Even if detected and countered, saturation attacks will force defenders to commit massive amounts of surface to air and air to air munitions, creating opportunities for follow-on force exploitation. Small maneuver groups can also be committed against critical enemy main body forces, such as amphibious, airborne, or air assault groupings during enemy joint forcible entry operations. Though small maneuver group attrition will be extremely high in saturation attacks, the damage to critical enemy system components and preservation of follow-on-force combat power and human lives will merit the expense. Attrition operations must enable Joint Force success. As Vietnam taught military planners, kill counts do not always equal victory.

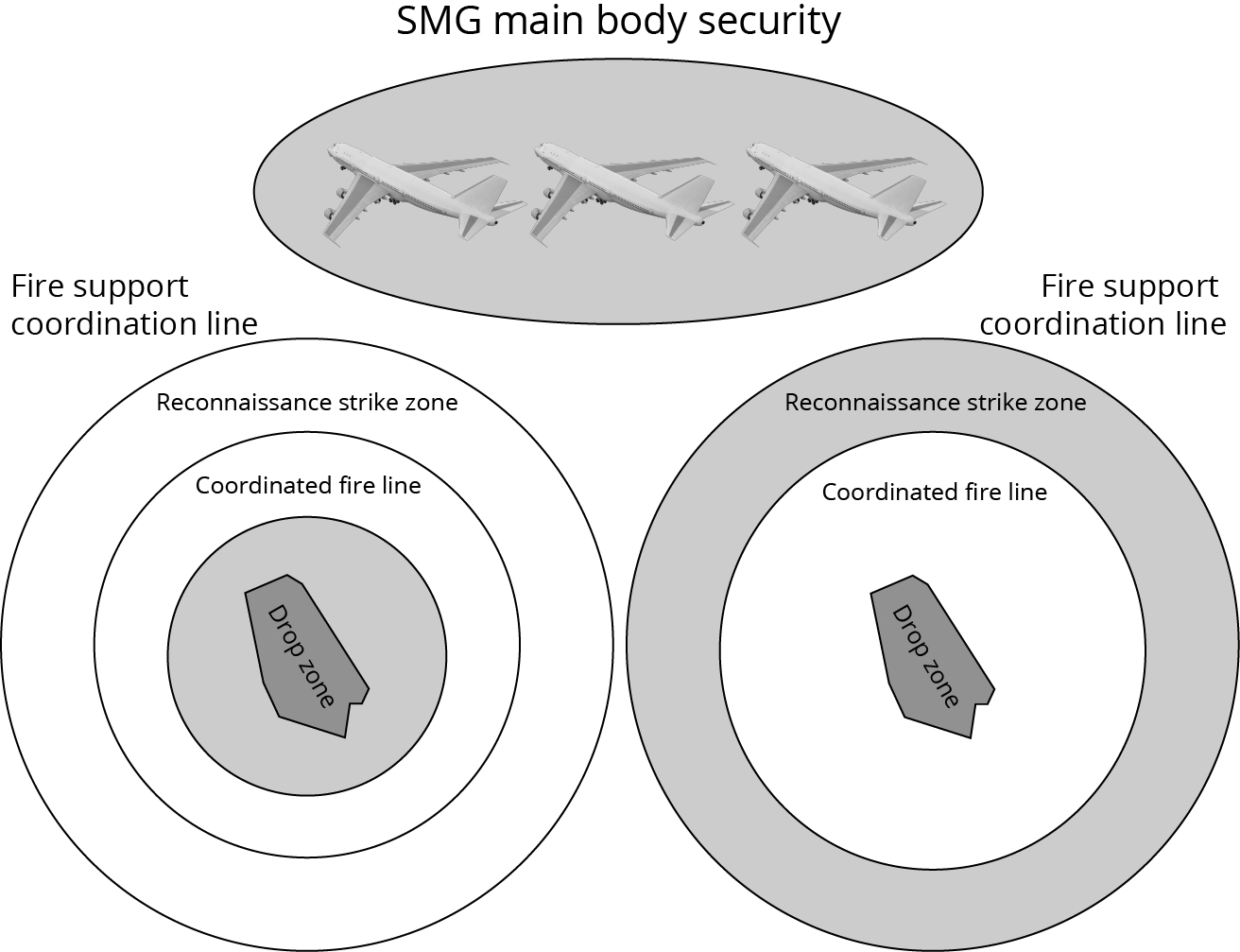

3. Joint forcible entry: Airborne, air assault, and amphibious Joint forcible entry are among the most difficult operations to execute. Small maneuver groups can fulfil three roles to enable joint forcible entry operations: advance guard, main body security, and aerial or littoral minefield. In an advance guard role, small maneuver groups conduct a reconnaissance in force of the approach heading and airhead line or beachhead, neutralizing enemy air defense, antiship, and counterattack forces that survived preassault fires. In main body security, small maneuver groups act as a three-dimensional shielding force for air and sea transports, interdicting enemy missiles and aircraft with kamikaze-style collision attacks. Once U.S. forces seize a lodgment, small maneuver groups establish an aerial or littoral minefield: a three-dimensional guarding swarm tasked with neutralizing enemy direct and indirect fires against the protected force. The aerial minefield occupies a hollow-cylindrical RSZ between the coordinated fire line and fire support coordination line. After lodgment stabilization and follow-on-force introduction, small maneuver groups can transition to raiding and saturation attacks in support of JFC offensive operations.

Small maneuver groups enable U.S. interests in competition and crisis. During competition, small maneuver groups offer increased aerial reconnaissance mass to company commanders. For example, in the South China Sea the reconnaissance and advance groups could increase surveillance of PRC gray-zone fishing fleets in Philippine waters. Filming their coercive methods and publishing it for the world to see could increase political pressure on the PRC to obey international law. Electronic warfare groups can jam the fishing fleets navigation systems and communications, and information warfare groups can spread pro-U.S., anti-PRC information to these proxies. Small maneuver groups should partner with Marine Corps stand-in forces, Joint Special Operations Command, and Army security force assistance brigades to train with partners and allies. SMGs must demonstrate their lethality and operational range to adversary decision-makers to inflict doubt on their ability to accomplish fait accompli campaigns. During crisis, small maneuver groups conduct demonstrations to display U.S. resolve to both deter adversaries and assure allies and partners. Small maneuver groups maintain the ability to conduct preemptive strikes on adversaries in conjunction with air forces and long-range fires.

Figure 5. Visual depiction of a small maneuver group supporting a joint forcible entry—

airborne operation

Top: A small maneuver group serves as main body security of transport aircraft. Left: A small maneuver group advance guard neutralizes enemy forces in the vicinity of a planned drop zone and confirms pre-assault fires effects. Right: A small maneuver group establishes an aerial minefield to protect an airborne lodgment.

Source: courtesy of the author, adapted by MCUP.

Current Shortfalls and Limitations

As with tanks and aircraft during the early interwar years, UCV capabilities do not yet match the requirements necessary to transform the small maneuver group from theory to reality. While progress is constantly being made, the following capability gaps need to be addressed.

Sustainment: The small maneuver group needs to be capable of deep offensive maneuver and persistent presence in enemy territory. Hydrogen fuel cell batteries and solar power offer potential solutions to extending UAV endurance, as well as in-flight battery swaps currently being experimented with on the civilian market. As small maneuver groups are attrited, replacement UCVs can be delivered via self-movement or aerial delivery. Forward-postured and disaggregated 3D-printing sites can produce swarm group UCVs in mass and their components as needed. During periods of competition, stockpiles of extra small maneuver group UCVs of all types should be mass produced to facilitate the high attrition likely in conflict.

Command and control: Improvements in AI-enabled swarm tactics, machine learning, data sharing, rapid identification friend or foe (IFF) software, and robust space-based C2 capabilities are all required to make the small maneuver group a reality. Using OFFSET as a baseline, digital and real-world exercises should be used to build data sets and improve algorithms. Joint all-domain command and control (JADC2) is a possible solution to the C2 requirements of small maneuver groups.

Protection: Against hostile kinetic fires, speed, and dispersion are the best protection measures for small maneuver groups. To increase resilience to electronic attack, UAVs must be hardened to resist effects and forward stationed in hardened sites. As an example, Russians implemented primitive measures to reduce the effects of jamming on their Iranian-purchased Shahed-136 loitering munitions in Ukraine.29 In the event of GPS denial, small maneuver groups navigate by AI-driven terrain association, celestial navigation, or preprogrammed coordinates. When jammed, UCVs must execute in accordance with AI algorithms or conduct a terminal attack. Small maneuver groups conduct feints, move in unpredictable manners, and disperse to overwhelm adversary sensors and decision making. In short, when employed en masse, the drone will always get through.

Weather effects: Storms, rain, fog, extreme temperatures, and other natural factors will reduce the effectiveness of small maneuver groups. They also provide opportunities for undetected infiltration of enemy territory.

Policy: SMG operations require national-level authorization to conduct HOOTL targeting and engagements in RSZs. IFF systems will need improvements to reduce the risk of collateral damage, especially over areas with significant civilian populations or when operating close to friendly forces.

Conclusion

As Heinz Guderian wrote in Achtung—Panzer!, the inspiration of this article, regarding the tank in 1937:

On many issues there still exist differences of opinion of a sometimes quite fundamental nature. Only time will tell who is right. But it is incontrovertible that as a general rule new weapons call for new ways of fighting, and for the appropriate tactical and organizational forms. You should not pour new wine into old vessels.30

This is one attempt at not pouring new wine into old vessels. The methods and proposals in this article are far from perfect, and critiques and alternative opinions are encouraged. The goal of this article is not to be right but to ensure the Joint Force generates new ideas, dialogue, and purposeful action regarding the employment of UCVs in support of the Joint Operational Access Concept and Joint entry operations. If we do not, adversaries will. The only failure in this field will be a failure of imagination.

Endnotes

1. Joint Concept for Entry Operations (Washington, DC: Joint Chiefs of Staff, 2014), 10.

2. Chris Bellamy, “Heirs of Genghis Khan: The Influence of the Tartar-Mongols on the Imperial Russian and Soviet Armies,” RUSI Journal 128, no. 1 (March 1983): 52–55, https://doi.org/10.1080/03071848308522218.

3. Timothy May, The Mongol Art of War: Chinggis Khan and the Mongol Military System (Barnsley, UK: Pen and Sword Books, 2007), 121–26.

4. Timothy B. Smith, The Decision Was Always My Own: Ulysses S. Grant and the Vicksburg Campaign (Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press, 2018), 35.

5. Matt Atkinson, “Van Dorn’s Raid,” Mississippi Encyclopedia, 15 April 2018.

6. Tim Deforest, “Grierson’s Raid during the Vicksburg Campaign,” HistoryNet, 12 June 2006.

7. Deforest, “Grierson’s Raid during the Vicksburg Campaign.”

8. Elvis E. Blumenstock, A Look at Soviet Deep Operations: Is There an Amphibious Operational Maneuver Group in the Marine Corps’ Future? (Quantico, VA: Command and Staff College, Marine Corps University, 1994).

9. Henry S. Shields, “Why the OMG?,” Military Review 65, no. 11 (November 1985).

10. Georgii Isserson, The Evolution of Operational Art, trans. Bruce W. Menning (Fort Leavenworth, KS: Combat Studies Institute Press, 2013), 43–70.

11. “Missiles of Iran,” Missile Threat, Center for Strategic and International Studies, 10 August 2021.

12. Natasha Turak, “How Saudi Arabia Failed to Protect Itself from Drone and Missile Attacks,” CNBC, 19 September 2019.

13. John Antal, Seven Seconds to Die: A Military Analysis of the Second Nagorno-Karabakh War and the Future of Warfighting (Havertown, PA: Casemate, 2022), 22.

14. Uzi Rubin, The Second Nagorno-Karabakh War: A Milestone in Military Affairs, Mideast Security and Policy Studies no. 184 (Ramat Gan, Israel: Begin-Sadat Center for Strategic Studies, 2020), 7.

15. Department of Defense Directive 3000.09, Autonomy in Weapon Systems (Washington, DC: Department of Defense, 25 January 2023).

16. Nicole Thomas et al., “What the United States Military Can Learn from the Nagorno-

Karabakh War,” Small Wars Journal, 4 April 2021.

17. Antal, Seven Seconds to Die, 27.

18. Antal, Seven Seconds to Die, 28.

19. John C. K. Daly, “Ukraine Launches Unprecedented Drone Attack on Russian Black Sea Fleet’s Sevastopol Headquarters,” Eurasia Daily Monitor 19, no. 166 (8 November 2022).

20. Luke Harding and Isobel Koshiw, “Russia’s Black Sea Flagship Damaged in Crimea Drone Attack, Video Suggests,” Guardian, 30 October 2022.

21. Mick Ryan, “How Ukraine Has Changed the Character of War,” Futura Doctrina (blog), 21 February 2025.

22. Mick Ryan, “The Battle of Lyptsi: Robotic Land Combat,” Futura Doctrina (blog), 22 December 2025.

23. Thomas Hamilton and David A. Ochmanek, Operating Low-Cost, Reusable Unmanned Aerial Vehicles in Contested Environments: Preliminary Evaluation of Operational Concepts (Santa Monica, CA: Rand, 2020), 5–7, https://doi.org/10.7249/RR4407.

24. Hamilton and Ochmanek, Operating Low-Cost, Reusable Unmanned Aerial Vehicles in Contested Environments, 12.

25. Hamilton and Ochmanek, Operating Low-Cost, Reusable Unmanned Aerial Vehicles in Contested Environments, 13.

26. “OFFensive Swarm-Enabled Tactics (OFFSET),” Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency, accessed 13 August 2025.

27. Isserson, The Evolution of Operational Art, 35.

28. “Affordable Mass: Precision Guided Munition Requirements for Great Power Conflict,” episode 63, 12 February 2022, in Aerospace Advantage, podcast.

29. Justin Bronk, Nick Reynolds, and Jack Watling, The Russian Air War and Ukrainian Requirements for Air Defence (London: RUSI, 2022).

30. Heinz Guderian, Achtung—Panzer!: The Development of Tank Warfare, trans. Christopher Duffy (London: Cassell, 2012), 226, Kindle.