Michael T. Maus

https://doi.org/10.21140/mcuj.20241502010

PRINTER FRIENDLY PDF

EPUB

AUDIOBOOK

Abstract: During the Falklands War in 1982, the United Kingdom conducted an amphibious landing to repossess the Falkland Islands from the invading Argentinians. The Falkland Islands naturally possess thousands of miles of shoreline and more than two dozen suitable beaches for an amphibious landing with several in close proximity to the United Kingdom’s primary objective of Stanley. However, British forces landed in the San Carlos Water, a bay across East Falkland Island miles from their objective all the while short of tracked vehicles and helicopter transports and pressured by the approaching onset of the Southern Hemisphere’s winter. This article analyzes why British task force planners selected the San Carlos inlet for an amphibious assault and what parameters and events bound or persuaded planners to make their final decision. This article contributes to the operational analysis historiography of the Falklands War by examining the reasoning of selection and further supplements the historiography on the British way of war with regard to amphibious operations.

Keywords: United Kingdom, Argentina, Falklands War, Falkland Islands, amphibious operations

Introduction

At the start of the Falklands War, the United Kingdom was in a gradual process of demobilization of military assets such as advanced warning radar systems aboard ships or aircraft and amphibious warships, landing craft, and materiel necessary for amphibious operations in mass. Even after the grand amphibious operations that took place on the many fronts of World War II, and the usage of such methods of warfare as late as the Suez Crisis in 1956, the question over the continuation and necessity of marine amphibious forces was consistent and gaining momentum in the British Parliament up to the last decade before the Falklands War.1 The nuclear age along with nuclear weapons put into question the idea of amphibious expeditionary forces as they are slow and seemingly predictable and findable targets and subject to annihilation from a single tactical nuclear weapon. Nuclear weapons development and output among the superpowers rose exponentially since their inception leading up to the Falklands War. And the United Kingdom was no exception as its own inventory of nuclear weapons grew to 500, its highest ever.2 Despite this heavy arsenal and the three decade long successful deterrence the United Kingdom waged in support of North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO), the junta of Argentina chose to go to war against the United Kingdom.

The Falklands War revealed that the probability of an island war fought conventionally against a regional power in the nuclear age while one of the belligerents obtained nuclear weapons can still exist. The United Kingdom still possessed amphibious trained units and some equipment, though at the start of the conflict, they were hastily assembled. The British lacked war plans of this war scenario even though diplomatic conflict over the Falklands sovereignty was consistent in the twentieth century. Due to a lack of troopships, amphibious warships, and the need for further training, the British lost time at sea restowing and rehearsing at Ascension Island for an amphibious operation that was difficult but not entirely unfamiliar to others it had conducted in the past.3 The British were also not equipped in full when they departed the United Kingdom. Their early departure required a major airlift of supplies to Ascension Island, putting stress on the Royal Air Force.4 Further hindering landing planners was the lack of general understanding of amphibious operations among all staffs involved in the British task force. These symptoms contributed to limited options on where and when to land on the Falklands.5 Even so, their success in planning, landing, and ending the conflict before weather forced diplomacy over action emphasizes the advantages and necessity of possessing and maintaining modern amphibious forces.

The Falklands War began on 2 April 1982, with the Argentinian invasion of British territories in the South Atlantic and lasted until 14 June of the same year. Operation Corporate was the code name for all British military operations in the Falklands War. Strategically, retaking the Falklands was a grand amphibious operation, although it depended entirely on the British Royal Navy’s ability to obtain and maintain control of the sea. The journey from the United Kingdom to the Falklands was more than 8,000 nautical miles. Furthermore, the Falklands are more than 3,000 nautical miles from the nearest British base at Ascension Island. On top of that, the task force faced challenges from the available technological resources of the time as well as time itself, for the Southern Hemisphere was soon approaching winter.

During the nearly seven weeks in transit, the British task force was at sea restowing or training at Ascension Island as well as in transit to the Falklands. Ultimately, the Argentinian military surrendered to British forces on East Falkland Island following their amphibious invasion at San Carlos to reclaim the territory. The amphibious landing at San Carlos on East Falkland was the only major landing by the British during the Falklands War. The landings occurred early on 21 May 1982, less than two months into the war. British commanders debated the proper landing site for their forces to mount an amphibious assault to retake the Falkland Islands group from the occupying Argentinians.

Thousands of kilometers of shoreline exist on the Falklands, providing dozens of accommodating sites for amphibious landings.6 Many of these landing sites had defenses while others remained undefended. Many were close to Britain’s military objective of Stanley, while other sites were far away or on different islands altogether. Why did the British task force planners select the San Carlos inlet as the suitable area for an amphibious landing in the invasion of East Falkland? British task force planners selected the San Carlos inlet to assault East Falkland Island because it was a lightly defended landing area with an acceptable beach, had suitably protected anchorage for landing force vessels, had the best natural surrounding features to reduce the risk of counterattacks and aerial threats, and was still within an acceptable distance to their final objective of Stanley.

This article will first briefly describe the Argentinian invasion followed by the British government’s response. The British government successfully laid out the political objectives and parameters by which the conflict would be fought, and this enabled task force planners to begin searching for the best landing area. The author then describes the current situation and obstacles that faced the British task force and briefly describes the intelligence situation. Following this, the article includes the Argentinian defense, the landing force, and the Argentinian air situation to contextualize and show the factors that partially affected the planner’s elimination process. From here, the article examines why San Carlos inlet was the site that suited the needs and desires of the British task force best by describing the beach and landing areas, anchorages, surrounding landscapes security, the inlets protection from aerial threats, and its general proximity to Stanley.

Argentina Invades

After decades of rising tensions over the sovereignty of the Falkland Islands, the Argentinians decided to reclaim the “occupied” territory by military force. Reports from the South Georgia local government reveal that Argentinian military action began as early as 19 March, with the firing of shots and the raising of Argentina’s national flag on the island.7 By 28 March, three groups of warships left the Argentinian mainland, with plans to capture the Falkland Islands.8 Sailing from Puerto Belgrano, the Argentinian naval landing forces took five days to reach the Falklands. With the islands’ territorial defense force comprising fewer than 200 British military personnel, the Falklands quickly fell to Argentina on the morning of 2 April.9

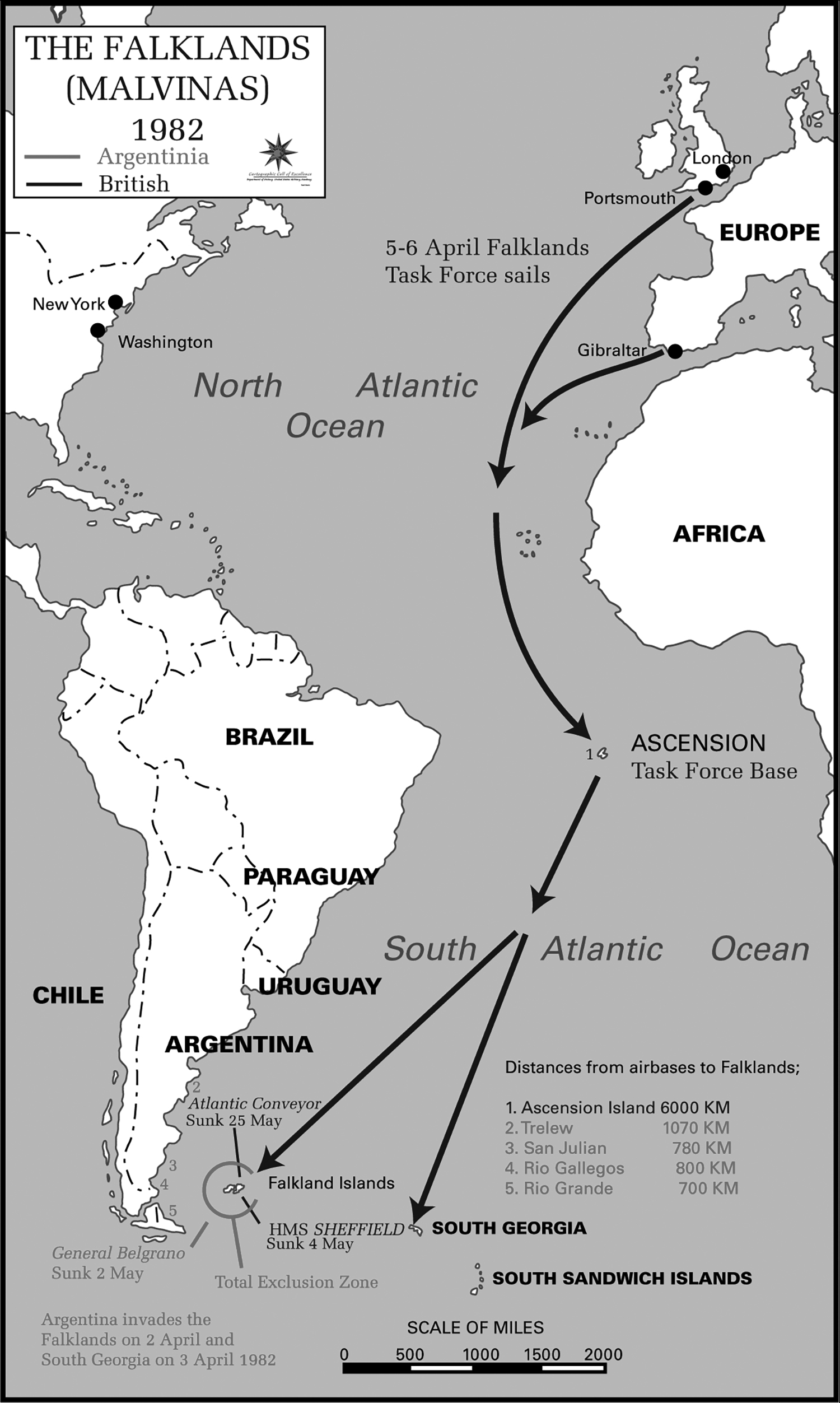

British prime minister Margaret Thatcher addressed the House of Commons on 3 April. Thatcher stated that the Falklands were still British territory, and no amount of military aggression can change that fact. Thatcher informed the house that some British naval units were already at or putting to sea immediately, and others gathering, stating that “the Government have now decided that a large task force will sail as soon as all preparations are complete.”10 The first launched naval units in the task force comprised of aircraft carriers, destroyers, frigates, and support ships, which left England as soon as 5–6 April. The remaining task force units, comprised of troopships and other supply vessels, left England no later than 9 April. The British task force joined forces with more British warships originating from Gibraltar and sailed together south to Ascension Island.11

Map 1. Route and distances of the British task force

Source: map courtesy of West Point Atlases Online, adapted by MCUP.

Political Objectives and Parameters

Before the British task force engaged with Argentina’s military in the South Atlantic, the British government succeeded in establishing its political objectives for the war and listed a set of preconditions required in the naval and aerial theater of war before any landing could take place on the Falkland Islands. On 11 April, commander of the South Atlantic Task Force, Admiral Sir John Fieldhouse, sent a tentative list of directives to the senior leadership along with the task force. Among these were commander carrier/battle group, Rear Admiral Sandy Woodward; commander amphibious task force, Commodore Michael C. Clapp; and commander landing force, Brigadier Julian Thompson.12 The directives stated that the task force was to “(a.) Enforce Falkland Island exclusion zone., (b.) Establish sea and air superiority in Falkland Island exclusion zone., (c.) Repossess South Georgia., [and] (d.) Repossess Falkland Islands.” Priority stressed subject (b.), while subjects (b.) and (c.) were on the same time scale.13 Furthermore, Fieldhouse advised Clapp and Thompson that they should “do the utmost to avoid an opposed landing.”14

Commodore Clapp states that neither he nor General Thompson intended to plan for an opposed assault. Clapp states that an opposed assault “is not our way of doing things and is not usually the more successful” option unless large-scale overkill is the intention or deemed acceptable.15 An opposed landing was also undesirable by the British due to the limited size of their available forces. The British soon realized they required more men to invade the Falklands at their discovery that the Argentinians had reinforced their garrison from 3,000 to at least 8,000 by 16 April. The rule book of amphibious operations states that the assaulter should have a three-to-one superiority over the enemy. By 16 April, the British landing forces were still outnumbered by a ratio of two-to-one.16 These ratios would likely not be present at the actual landing site. However, a campaign to end the war required more men.

On 17 April, Admiral Fieldhouse flew to Ascension Island and stated to a briefing room of nearly 100 naval and land force officers aboard the carrier HMS Hermes (R 12) that “if diplomacy failed,” the task force “could depend on absolute political support for its operations.”17 This assurance enabled commanders to operate at their own discretion and allowed for operational planning to begin. With this in mind, Clapp added a fifth task to the list. He stated that the task force needed to get as far south as swiftly as possible.18 Clapp’s concern for reaching the Falkland Islands as soon as possible was shared by all commanders in the task force.

The British Task Force Situation

The greatest natural concern to the fleet was the rapid approach of winter in the Southern Hemisphere and the expected environmental problems that come with the season. Thompson states that the majority of warships would face equipment failure by mid-to-late June. Thompson adds that any limitation to the sustainability of the navy would “have a profound effect on the land battle,” as well as reduce the overall time for pre-landing reconnaissance.19 The logistics of maintaining the task force for any protracted amount of time in the South Atlantic, being so far away from the United Kingdom or from their nearest base at Ascension Island, was difficult and unsustainable. The lack of current intelligence the British possessed of the Argentinians on the Falkland Islands was troubling and made planning difficult.20

Intelligence was mainly limited to reconnaissance missions by air or by special forces ground teams. Information on Argentina’s military and inventories from partnering nations such as France and the United States came to the task force, but information on Argentina via ground sources was still inadequate.21 Woodward describes that British intelligence on the Falklands had “very considerable ignorance—our intelligence had never been targeted on Argentina and, since the Falklands had never been thought a likely battleground, our knowledge of the seas around was absolutely minimal.”22 And special forces operations did not start on East Falkland until May.23 A British government paper, written 26 April, states that if the fleet were at all passive in the South Atlantic, they were then vulnerable to storms, enemy aircraft, enemy submarines, distance to friendly bases, declining morale, declining battle fitness, and illness.24 Task force commanders then established the window for mounting an amphibious landing as soon as 16 May and no later than 25 May.25

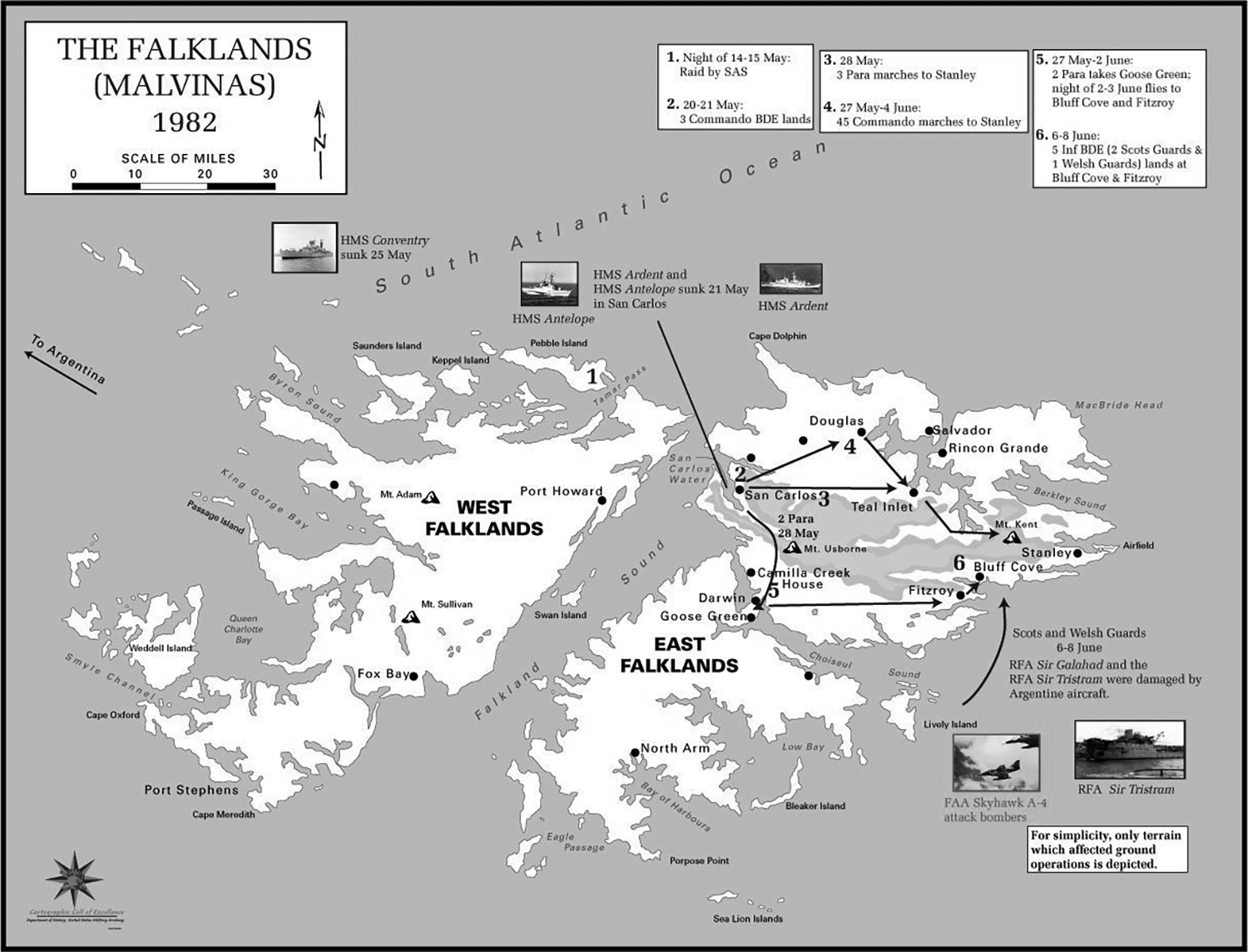

Map 2. Battle of the Falkland Islands

Source: courtesy West Point Atlases Online, adapted by MCUP.

Menendez’s Defense

Task force planners were correct in assuming the defenses around Stanley were significant enough to inflict severe casualties and possibly thwart a British landing. Argentinian land forces commander general Mario Menendez’s first defense priority focused on where the British were going to land. Menendez figured they would land on East Falkland either at Cow Bay north of Stanley or Port Fitzroy just south of Stanley and possibly Low Bay on the southeast coast of Lafonia. The greatest blow to his forces would be a direct assault on Stanley. In light of this, Menendez formed his defensive strategy into a static zone defense centered around Stanley. The number of plausible landing beaches made it impossible for the Argentinian defense to mine and erect landing defenses as well as defend every beach at the water’s edge. An Argentinian brigade and marine battalion defended Stanley, with the remainder of Menendez’s forces displaced around the rest of the islands. A total of nearly 13,000 Argentinian troops defended the Falklands, of which three-quarters garrisoned the Stanley region.26

The Landing Force

Twelve amphibious ships, some as auxiliary vessels and not warships, comprised the landing force. The 12 amphibious ships were the command assault ships HMS Fearless (L 10) and the HMS Intrepid (L 11), the small landing ships RFA Sir Galahad (L 3005), RFA Sir Geraint (L 3027), RFA Sir Percivale (L 3036), RFA Sir Tristram (L 3505), and RFA Sir Lancelot (L 3029), the royal auxiliary ships RFA Stromness (A 344) as a stores-ship and RFA Fort Austin as a helicopter carrier, and the requisitioned troopships of SS Canberra, MV Norland, and MS Europic Ferry. The plan was for the three troopships to sail right into landing positions with the other amphibious landing ships, a venture not foreseen on their departure from England.27 By the final days of planning, seven warships would escort the amphibious landing force. The escorts comprised the destroyer HMS Antrim (D 18), Type 22 frigates HMS Brilliant (F 90) and HMS Broadsword (F 88) for antiaircraft defense, and general-purpose frigates HMS Ardent (F 184), HMS Argonaut (F 56), HMS Plymouth (F 126), and HMS Yarmouth (1745).28 Fearless and Intrepid each weighed 12,000 tons. The smaller five landing ships weighed just more than 500 tons. The Stromness displaced the most, weighing 16,000 tons, and the destroyer and frigate weights varied from 2,800 to 5,500 tons.29 The landing force, with its protection, traveled at 12 knots maximum, giving Woodward and Clapp concern.30 The minimum draft the landing ships required was 26 feet. Task force planners needed the landing force to sail into landing positions safely, have suitable depths for proper anchoring, and have shelter from submarines. Many landing areas did not meet these criteria.

Argentina’s Air Situation

At the start of the conflict, the Argentinian Army, Air Force, and Navy each had aircraft deployed to the Falklands for its defense. Only light-attack aircraft and aerial transports were deployed on the Falklands as part of its defense. Argentinian high-performance aircraft used in the war originated from bases on the Argentina mainland. Argentina’s Air Force operated 82 combat aircraft of this caliber. The most important of these were “thirty-two American A-4 Skyhawks, twenty-four Israeli Daggers, and eight French Mirage IIIEAs.”31 The Argentina Navy added eight Douglas A-4 Skyhawks and five French Dassault-Breguet Super Etendards to the list of high-performance aircraft. Argentinian Navy Skyhawks were the only aerial force coming from the sea from their only carrier, ARA Veinticinco de Mayo (V 2). The Super Etendards were the only aircraft fitted with the Exocet AM39 antiship missiles. The remaining aircraft fired mostly unguided 500 pound and 1,000 pound bombs.32 Ninety-seven percent of the aerial inventory of Argentina was operational during the war.33 The Etendards and Veinticinco de Mayo were the greatest threats to the task force in the eyes of the British.34 The Argentinians also used, ironically, English Electric Canberra medium bombers, though these were slow and lacked the abilities of the modern harrier and regarded as an insignificant threat to the British task force.

The capabilities of Argentinian aircraft significantly limited their usage during the war. Argentina’s Dagger and Dassault Mirage aircraft lacked refueling capabilities and could not loiter. Conversely, the Skyhawks and Etendards had refueling capabilities. However, the Argentinians had only two Lockheed Martin KC-130 aerial refuelers.35 On the Falkland’s, none of the outlying airfields could support high-performance aircraft, and the runway at Stanley was deemed too short and too dangerous when wet to operate larger aircraft.36 Even with their limited operational capabilities, Argentinian aircraft possessing Exocet missiles posed the most lethal threat to the British task force.

The Exocet AM39 was a low-flying sea-skimmer missile capable of being fired from aircraft, warships, or a coastal defense platform. Both the British and the Argentinians possessed these weapons, though the Argentinians possessed only five AM39s for their five Super Etendard aircraft. Argentina also had six destroyers and frigates fitted with Exocet ship-to-ship missiles.37 However, it was the aerial version that inflicted the most damage on the British task force and was the worst threat to anchored landing ships. Exocets had the technological advantage of homing in on targets without human guidance. An example of this came on 4 May. Argentinians launched two Etendards to attack the British carriers in the task force. The aircraft flew low to avoid radar detection and would fly up periodically “to allow their radars to search for targets.”38 Once in range, Argentinians had no idea if they had fired on a destroyer or a British carrier. The attack resulted in the destruction of the destroyer HMS Sheffield (D 80). The Argentinian pilots fired on the first available target and struck the picket line of warships instead of the intended carriers.39

The air-to-surface Exocets fired from Argentinian Super Etendards changed the tactics of the entire war. Woodward writes, “despite all of our defensive systems, one had got through and demolished one of my three Type 42 destroyers without even exploding.”40 Three of the five Exocets remained in the inventory of Argentina, according to British intelligence at the start of the war. Therefore, Woodward concluded that he may yet lose another ship or possibly two. And Woodward placed higher protection and protocols around his carriers and increased their distance from known Argentinian Exocet threats. Embracing the reality of the weapon’s capability, task force planners focused on selecting a landing site that completely neutralized the Exocet threat.

By the time the task force reached the South Atlantic, the airfield at Stanley was repeatedly bombed and partially damaged by Avro Vulcan bombers and later on by task force fighter-bombers. Throughout the aerial and naval campaign leading up to the assault at San Carlos, several airfields and Argentinian installations received air strikes and naval bombardment in an attempt by the British to achieve air superiority and weaken the Argentinian strong points for the coming landing force. One of the airfields on Pebble Island was directly targeted and neutralized by British special forces to relieve the aerial threat as well as reduce Argentina’s radar capacity at the northern entrance of the Falkland Sound.41 The airfield had 10 attack aircraft comprised of 6 FMA IA 58 Pucarás and 4 Beechcraft T-34 Mentors. One Short SC.7 Skyvan utility aircraft was also on the airfield. British special forces successfully destroyed all 11 aircraft in what is known as the Pebble Island Raid. Argentina was soon able to replace some of the lost aircraft but with a reduction to the total Argentinian Air Force on the Falklands as well as Argentina’s capability from Pebble Island.42 This would later benefit the approaching landing force as well as the anchored vessels in San Carlos from aerial bombardment.

Elimination Process

Argentina is west of the islands, roughly 400 nautical miles from the westernmost tip of the islands to the nearest continental coastline of South America.43 The Falklands consist of an area of nearly 4,700 square miles.44 Approximately 2,500 statutory miles of coastline exist on the islands. The three main land masses are West Falkland, East Falkland, and Lafonia. Lafonia is part of East Falkland but connects only by a narrow strip of land at Goose Green and Darwin. West Falkland is separated from the others by the Falkland Sound. The sound’s width stretches from 15 to 30 miles between the two island groups. Hundreds of smaller islands form around the three larger ones. The islands are semi-mountainous, ranging from sea level to the highest point of 2,312 feet.45 The terrain on all islands has many low hills, large rocky outcrops, and many areas of bogland.46 The islands are void of foliage, providing no cover for vehicles or foot soldiers.47 The coastline possesses dozens of harbors and inlets. Argentinian defenders estimated that 30 of the islands’ beaches were suitable for an amphibious landing.48

Clapp interpreted the directive that stated the plan was to repossess the Falklands as meaning an invasion on East Falkland as well as a landing close to Stanley.49 Thompson agreed, and they decided early in the planning process to discard ideas of landing anywhere other than the north half of East Falkland Island. Landings at Stevelly Bay, Fox Bay, and Port Howard on West Falkland were pushed for by Admiral Woodward but ruled out for reasons discussed further on. Landings on Lafonia were also ruled out for similar reasons. Among British planners was Major Ewen Southby-Tailyour. Southby-Tailyour possessed extensive “encyclopedic” knowledge, as described by Clapp, of the Falkland Islands and its beaches from his many yacht excursions of the islands. Southby-Tailyour’s memory supplemented hydrographic charts, and he provided a shortlist of beaches on East Falkland worth looking at. Planners decided that there were 19 beaches plausible for a landing on East Falkland.50 Clapp and Southby-Tailyour reduced the list by half. Their list included “Volunteer and Cow Bays, Berkeley Sound, Salvador Inlet, North Camp (referencing all beaches on the north-west shore of East Falkland), Darwin, inlets off the Choiseul Sound, and San Carlos.”51

The two staff groups of Clapp and Thompson eliminated several beaches on the north half of East Falkland due to either their lack of width, slope, expected traction for landing vehicles, or by the erected obstacles of the Argentinian defense. The selected beach or beaches required gradients suitable for landing craft or Mexeflote boats. Clapp states that the beaches had to fit a brigade-size landing into as many as four areas, and at least one of the beaches needed a large and flat space for a “beach support area.” All of the beaches needed suitable traction and exits for infantry, tanks, and other vehicles to proceed inland.52 Beaches with sand dunes, cliffs, or high tussocks were not suitable and eliminated.53 Woodward argued that the beachhead must include the possibility of constructing an airstrip out of the terrain should his carriers remain at a permanent level of high-risk of attack.54 However, Woodword’s criteria were not prioritized by Clapp or Thompson due to the difficulty of such a venture.55

The planner’s initial intention was to hit the northeast coast of East Falkland so that they would look down topographically onto Stanley from the north and west. Any attack from the south or southwest would mean the “breasting up” of British forces to the main defensive lines of the Argentinians. The planners avoided this approach entirely.56 They also avoided a direct assault at Port Stanley so close to the Argentinian garrison commanded by Brigadier General Oscar Jofre.57 Thompson states that an amphibious landing in the vicinity of Port Stanley “would probably run into well-prepared defensive positions, wire, mines, and beaches covered by gunfire both direct and indirect.”58 At the time, the British did not possess armored amphibious vehicles or direct-fire assault guns on either vehicles or ships to provide any close fire support. Therefore, a suitable beach required that it was out of range of the Argentinian 105-mm guns, concentrated mostly around Stanley.59 There was a risk to the landing force that Argentina would reposition their guns quickly. Argentina’s guns were lighter than those the British had, and they could be cabled, lifted, and hauled by light-helicopters to new positions.60 Of greater concern was the British fear of the civilian casualties as well as collateral building damage. A direct assault on Port Stanley was out of the question.

Several meetings of task force leadership occurred in mid-to-late April to analyze and discuss landings on the northeast coast of East Falkland Island. Northeast landing sites included Cow and Volunteer Bays and the Berkeley Sound. Task force planners decided that Cow and Volunteer Bays were too exposed, easily defended, and poor for moving ground forces inland. Furthermore, Berkeley Sound had poor landscape features, had anchorages susceptible to rough seas and it was too close to the bulk of Argentinian forces on East Falkland. The landing forces would only target these areas “if the Argentines looked as if they wanted to surrender.”61 Berkeley Sound had the closest landing sites to Stanley, other than the port, but the British suspected the Argentinians of mining the seaward approaches.62 The San Carlos inlet on the west side of East Falkland was all that remained for major contenders for a landing site. This was Thompson’s and Clapp’s preferred choice.63

On 29 April, Thompson and Clapp were met by Major General Jeremy Moore aboard HMS Fearless at Ascension to discuss their primary landing options selected from the list of 19. The staff of both Thompson and Clapp narrowed the list to three possible areas. They presented the Cow Bay and Volunteer Bay areas (one mile apart), San Carlos, and Berkeley Sound. Port Salvador was the fourth site in consideration by Thompson and his staff, and personally Thompson’s second choice for a landing, but this was left out of their meeting. Due to reasons stated above, the staff eliminated options one and three and compromised on option two. Following the selection of San Carlos, Thompson’s staff agreed that the Port Salvador Inlet, northwest of Stanley 30 statutory miles, was the best alternative choice should reconnaissance teams find the San Carlos Water mined or the area significantly defended.64 Clapp did not push for his alternative landing choices for he was sure that San Carlos was the best choice.

Selecting San Carlos

San Carlos Topography

The San Carlos inlet is visually representative of a fjord. The northern side of the inlet above Port San Carlos has a low ridge of hills running southeast to northwest. Notable points on this ridge are the summits of Fanning Head and Settlement Rocks that are more than 700 feet above San Carlos Water. The southern flank of the inlet also has a ridge of hills that again runs southeast to northwest before turning straight north, providing shelter to the entire west and southern flank of San Carlos Water. The southern hills are known locally as the Sussex Mountains.65 The west ridges are called the Campito Mountains, and the east, the Verde Mountains. These ranges on the flanks of San Carlos Water ascend more than 650 feet, and the 500-mark contour lines on either side are only three miles apart.66

The Appropriate Beach

The beach conditions and the expected Argentinian defense of the beaches were major factors in selecting a suitable landing site. Any opposed landing overruled a beach’s prime condition due to the preferred preconditions of an amphibious landing set forth early in the war by the British government and senior task force leadership. The San Carlos inlet had three suitable beaches.67 The beaches possessed the proper slope for landing craft. They also had limited, but enough, space for a brigade-size landing force and good exits for landing forces to carry on inland. By the time planners selected San Carlos, intelligence had confirmed that San Carlos was not in range of Argentinian guns, nor would a landing there cost a severe loss of life due to the small Argentinian defense. The only Argentinian defense force at San Carlos was a small detachment of soldiers, a force no larger than 50, at Fanning Head on the north side of the inlet.68 By early May, Special Boat Service and Special Air Service reconnaissance teams found San Carlos “unbelievingly, except for visiting patrols . . . to be devoid of enemy.”69 The commanders of the task force partially selected the San Carlos inlet as the ultimate choice for an amphibious landing because it had a limited Argentinian defense and acceptable beaches. These are just two factors that went into selecting the landing site. Another factor that planners examined was which landing areas possessed proper anchorage.

Protected Anchorage

To conduct the amphibious landing that the task force planners envisaged, the water just off the landing area needed suitable depths and protection to anchor the vessels in the landing force. As part of the demands of the Royal Navy, the landing force had to have secure anchorage from bad weather and enemy attacks.70 The constant factor year-round in the weather cycle of the Falklands was high winds, and the landing area had to have calm or mild waters. A slight wind would hinder the roll-on/roll-off unloading procedures of the ships. A swell was the greatest weather danger to the landing vessels, according to Clapp.71 Planners expected the landing force to be slow on approach, and this made the risk to the landing force from any weather anomalies high.72 The second concern came from subsurface threats such as mines and submarines. The Argentine Navy “was effectively eliminated as a serious opponent” by the time of the landing as part of the precursor phase of operations.73 However, no matter how minimal, Argentinian submarines remained a constant threat to the task force and any anchored landing force for the rest of the war. Clapp states that from the naval perspective, the anchorage “had to have a difficult approach for or be easily defended against” submarine attacks. The Argentinians used German-designed S209 diesel submarines as part of their submarine force.74 The threat posed by these submarines was that one could “wait in advance of a landing or creep in undetected after one.”75 Therefore, the anchorage had to require enough depth to accommodate the drafts of the largest ships but also shallow enough water to prevent submarine incursions.76 With these risks in mind, task force planners selected San Carlos.

Clapp describes San Carlos as the “obvious choice.”77 He states that, from the overall point of view, “it seemed likely that the enemy would also have discovered San Carlos and marked, mined, and defended it.”78 The Royal Navy sent warships into the Falkland Sound and discovered that it was not mined. Likewise, special forces discovered that the entrance to the San Carlos inlet had no mines. The San Carlos inlet forked into two waterways. One harbored the small settlement of Port San Carlos, and the other led to the settlement of San Carlos.79 Six to seven grid miles separates these settlements. The narrow waters made it “ideal hiding places for ships particularly when there was mist and low cloud.”80 Ironically, General Menendez viewed the lack of “naval maneuver room” as a reason to dismiss San Carlos as a potential landing site for an amphibious landing.81

The San Carlos inlet had two “fine natural anchorages.”82 The deepest depth of the entrance to the inlet is 116 feet. The northern anchorage site ranges from this depth to 65 feet. The southern anchorage, where most of the landing ships gathered, ranges from depths of 100 feet deep to 40 feet at the shallowest.83 The width of the entrance is one and three-quarter miles. Six of the escorts remained positioned in the Falkland Sound for the landings. A submarine incursion was unlikely. Furthermore, the Argentinians mostly withdrew their naval forces from the maritime exclusion zone after the sinking of the ARA General Belgrano (C 4).

Task force planners required a landing area with suitable depths and protection from the natural elements and enemy attacks. The San Carlos inlet was the best choice available in this regard. The inlet had two anchorages in a narrow and relatively shallow stretch of water that helped prevent the threat of submarines. Task force planners also worked out that the anchorage site of the troopship Canberra would still keep the top decks of the ships above the waterline even if it were sunk.84 The narrow causeway of water also prevented swells from interfering with offloading operations, even with strong winds. Task force planners also selected the inlet as the ultimate landing site due to the surrounding natural features on all sides of the inlet that would protect the landing forces from counterattacks.

Secure from Counterattacks

The topography around the San Carlos inlet provided either an advantage over the surrounding area or potentially a great obstacle that risked the success of an amphibious landing. If secured, the hundreds of feet of ascending terrain gave invading ground forces the advantage of viewing the surrounding terrain of San Carlos for miles in each direction. This would enable the British to easily spot any approaching Argentinian counterattacks by air or land via line of sight or at night with thermal optic targeting. Furthermore, securing the surrounding high ground of the San Carlos inlet allowed air defenses to install. Overall, if the landing force seized the surrounding ridges, they held nearly every advantage. However, the enemy also holds every described advantage should they instead hold or reinforce the high ground before sufficient forces could land and establish a perimeter. Task force planners debated the scenarios of landing at an area with a high ascending surrounding landscape and decided that the advantages outweighed the disadvantages of such a venture.

Securing the high ground around the San Carlos inlet was a military necessity for the British landing force for both security and the prevention of an immediate Argentinian counterattack. The fear that the Argentinians would spot the landing force immediately entering the Falkland Sound and quickly reinforce the outpost at Fanning Head and other defensive points was a possibility the task force planners embraced when selecting San Carlos. Regarding ground counterattacks, Thompson’s concern was that the nearest Argentinian reinforcements would quickly secure the Sussex Mountains as the landing force approached San Carlos.85 An Argentinian counterattack from Goose Green-Darwin just 20 miles south had the potential to inflict serous casualties on the landing force. The Argentinian base there held 600 Argentinian troops and an airfield supporting small attack aircraft.86 During planning, Thompson only speculated that this force had the support of artillery, although he was certain it possessed air defense guns and surface-to-air missiles. A British Sea Harrier was shot down by these defenses in this area on 4 May.87 Three more Argentinian battalions were at either Port Howard or Fox Bay on West Falkland, though these were not an immediate threat.88 An Argentinian aerial counterattack to the San Carlos landing was a concern, but task force planners thought that one was logistically and numerically unlikely to repel the landing force. However, the landing was still at threat from aerial attacks.

Aerial Threats and Aerial Defense

The surrounding natural topography of San Carlos eliminated the threat of Exocet missiles. The surrounding features protected the landing force ships due to the phenomenon of radar shadowing provided by the terrain around the San Carlos inlet.89 The radar of the Exocets functioned poorly when operating near land.90 Furthermore, Argentinian pilots needed a minimum of “2,000 yards to lock their Exocet missiles on to target and direct line of site.”91 Even though San Carlos eliminated the greatest threat posed to the landing force, it did not eliminate all forms of aerial attacks.

By the time of the landing, Woodward states that “on paper, [the Argentinians] still had air superiority,” even with the Pebble Island Raid.92 And they were still a threat. The British knew that the San Carlos inlet was in the range of unrefueled Argentinian aircraft.93 Clapp was specifically worried at the fact that it was close to the maximum action radius of the Argentinian Skyhawks with heavy payloads.94 Even so, the windows of attack to the landing force in the San Carlos inlet for Argentinian pilots was narrow. The two openings for attack aircraft at San Carlos were at the northwest entrance to the Falkland Sound and the southeast valley between the Sussex and Verde Mountains leading to Darwin then Goose Green. The northwest entrance allowed for only medium- to high-level strikes, and the entrance gave Argentinian aircraft only two miles or 15 seconds at 550 mph. The southeast valley was the only approach that allowed for low-level strikes. Pilots had six miles of visibility and a gentle slope to approach the ships at or near sea level.95 British warships in the Falkland Sound were at greater risk than those in the inlet. Their placement was part of the British plan. Planners knew that due to fuel constraints, Argentinian aircraft would most likely approach San Carlos directly from the west. Clapp deliberately planned a “defense to take advantage of the protected anchorage and the high ground.”96 The six warships in the Falkland Sound were a picket line defense for the landing. Also, the frigates Broadsword and Brilliant with Sea Wolf missile systems were part of this defensive line. Other warships possessed the Sea Dart missile system. The Sea Wolf and Sea Dart had both scored aerial victories against aircraft. This picket line meant that Argentinian aircraft would first be subject to ship-to-air missiles before flying over the antiaircraft barrage from warships in the Falkland Sound and landing force vessels in San Carlos Water. The picket line also preyed on the mental condition pilots face during war.

Like many kamikazes in World War II flying through a constant heavy barrage with limited time, Argentinian pilots targeted the first ship they saw. Subsequently, the picket line of warships in the Falkland Sound faced the brunt of the Argentinian aerial attack following the landing.97 Furthermore, due to the split-second decisions and the minimum distances between aircraft, bombs, and targets, many of the Argentinians released their bombs “not allowing sufficient time for them to arm.”98 The west-northwest approach had a suitable defense to air attacks from the warships and the natural terrain of the inlet. The southeast approach was more accessible to attack aircraft, but the British prepared for this.

The surrounding landscape of the San Carlos inlet also provided perfect crests to install ground-to-air missile defense systems. The plan was for the first units in the landing force to secure the ridge lines, followed by artillery and the Rapier battery units.99 The goal of the Rapier system was to provide aerial coverage of the inlet as another layer of defense. The Rapiers were put into positions “scientifically chosen by computers in Britain’s chief radar research establishment at Malvern.”100 Unfortunately for the British, the systems could not install immediately due to the landing order. The landing began at night, and the Rapiers did not begin to install until daylight. The process was “excruciatingly slow,” because crews stowed the Rapiers at the bottom of ships’ holds. Furthermore, the Rapiers could only move by helicopter due to their size, weight, and the lack of roads or trails in the surrounding landscape. If spotters incorrectly sited the Rapiers by even a few feet, a helicopter had to adjust them. The British lost two Gazelle helicopters and three of four pilots during the installment process from attacking Argentinian aircraft.101 Once the Rapiers were online, they were quite formidable.

The Rapiers were low-level ground-to-air missiles firing up to 10,000 feet.102 Once established, the Rapiers set the firing base at X feet above the landing forces, putting the ships and troops ashore into a protected “pit.” Installing these at elevated positions above the landing force decreased the time and distance the Rapiers needed to target, fire, and reach Argentinian air units. This increased the risk to Argentinian planes and pilots should they aim to strike at the landing force and further decreased pilots’ time to assess, determine, and aim at any target inside the inlet. To prevent friendly fire once the missiles were online, Woodward set a box 10,000 thousand feet high and 10 by 2 miles wide that British aircraft could not enter.103

Although the San Carlos inlet did not eliminate the threats of ground counterattacks and aerial bombardments, the inlet succeeded in mitigating the threat to an acceptable level of risk. Securing the high ground around the inlet alone was able to deter counterattacks from enemy forces. Furthermore, the landing force outnumbered the nearest Argentinian forces at Goose Green-Darwin by a factor of nine-to-one at minimum. Via special forces, the British also had eyes on the main elements of Argentinian forces in the vicinity of San Carlos and on the main routes that reinforcements would travel to San Carlos, giving the landing force a clearer picture and enough time to react if needed. The surrounding landscape of the San Carlos inlet eliminated the threat of Exocet missiles and blocked a significant portion of other aerial attacks as well as suited the Royal Navy’s and ground force’s defense capabilities. The last reason task force planners selected the San Carlos inlet was due to its proximity to their ultimate objective of Stanley.

Proximity to Stanley

The proximity of the landing beach to the largest town on the Falkland Islands, Stanley, was a high priority to Argentinian defenders but of less priority to British task force planners. Clapp states, through the courtesy of the SBS and SAS, that the Argentinian defense catered to the expectation that the British would mount an amphibious assault like “the American way and land, if not straight into Stanley, then very close indeed.”104 This went against the guiding preconditions for a British landing set forth by political and military leadership at the start of the war. Furthermore, any landing too far from Stanley involved a long approaching march that put stress on their logistics and ability to resupply.105 Argentinian commanders set a policy that any landing far away from Stanley would face harassment from the helicopter infantry reserve at Stanley as well as from Argentinian special forces.106 As already mentioned, task force planners assessed nearly every plausible landing site on the Falkland Islands. And though the Argentinians had garrisoned troops on West Falkland, they did not suspect the British of contemplating a landing there.

Admiral Woodward sought a landing on West Falkland at the early stages of the planning process. Woodward considered West Falkland due to the likelihood of an easy victory and the expected advantages gained after taking the island. At the meeting aboard Fearless, on 16 April, Woodward first brought up the subject to the planning staff to make a bridgehead on the northwest coast of West Falkland at Stevelly Bay and hold it until finishing the construction of an airstrip.107 Woodward envisioned an airstrip that supported Lockheed C-130 Hercules transports and phantom fighter aircraft. He also listed that a landing at Low Bay, Lafonia, was also in close proximity to a flat plain necessary for the construction of an airstrip.108

Thompson writes that an airfield at Stevelly Bay on West Falkland was about as close to the Argentina mainland as the British could “get without actually being in the sea.”109 Furthermore, his engineers did not have the materiel nor the numbers to carry out such a scheme there or on Lafonia. Clapp and Southby-Tailyour added that they did not believe the landing would add “any real pressure on the Junta.”110 It also meant that if the Argentinians did not budge in diplomacy, that a second amphibious landing was necessary on East Falkland anyway. Thompson states that this alone was reason enough to throw the notion out. Woodward later realized that the landing at Stevelly Bay also exposed the fleet to air launched Exocets with no available cover to the task force, and the risk was too large to tolerate.111 All that remained was a landing on East Falkland.

The Low Bay landing scenario did not present an advantage over counterattacks from Goose Green-Darwin and was much closer to the Argentinian garrison there. Furthermore, the garrison strategically secured the chokepoint between Lafonia and the rest of East Falkland, and this had the possibility to hold up any British advance entirely. Therefore, planners eliminated Low Bay and Lafonia altogether. Volunteer and Cow Bays, Salvador and Teal Inlets, and the San Carlos area were acceptable landing sites due to their proximity to Stanley.112 Argentinian land commander General Menendez did not consider defending San Carlos, for it was 50 miles from Stanley and unlikely that the British would land that far away. And landings at Volunteer and Cow Bays and Salvador and Teal inlets were all half that distance.113 The Argentinians did not believe the British would choose a course where they would have to trek “units, supplies, and equipment across the rugged terrain of East Falkland to get to Stanley. They also believed that the British would get bogged down and that this approach placed them in an unacceptable vulnerable state.”114

The case for arguing that planners partly selected San Carlos due to its proximity to Stanley began when the British Royal Navy put forth the notion of landings on West Falkland or Lafonia. Both Clapp and Thompson and the Commando brigade staff aboard Fearless conclusively agreed that the landing should take place on East Falkland prior to Woodward’s proposal. West Falkland was too far, had too many risks, and demanded a second amphibious landing, which was unacceptable. Lafonia was also too far and gave every tactical advantage to the defending Argentinians and, therefore, unacceptable as well. A British landing at San Carlos was by no means the closest route to Stanley. However, it was well within the parameters of an acceptable distance away from their objective.

Conclusion

The decision to land at San Carlos came from careful consideration by task force planners who assessed the geography, typography, hydrography, and meteorology of the Falklands while pitting the capabilities of their forces against the known and later discovered capabilities of Argentinian forces. Task force planners faced constant duress over the timetable and the fog of war. The grand objectives and preconditions firmly established by senior political and military leadership guided task force planners and they followed the guidelines as best they could. Political and military leadership sought an unopposed landing, and San Carlos met that condition because it was out of range of Argentina’s heavy guns and defended by a force smaller than a company at a single observation point. The San Carlos inlet also met the minimum number of beaches, the specific grade, and possessed good exit points for a brigade-size landing force. Furthermore, San Carlos Water had two suitable anchorage sites for landing vessels, and the risk of swell and enemy submarines was low. The terrain around the inlet gave the anchored ships and the offloading troops protection from counterattacks and made aerial bombardment much more of a challenge for Argentina. The surrounding landscape also enabled the British to erect ground-based missile defense systems, providing further security for the landing force and relieving the pressure on their naval escorts. Lastly, San Carlos was within an acceptable range away from their ultimate objective of Stanley.

British task force planners faced an incredible challenge ahead of them at the start of the war. British intelligence on Argentina and their defense of the Falklands at the start of the conflict was minimal and speculative. For selecting a landing site, planners had dozens of options and still even 19 after they eliminated the obvious unacceptable landing areas. Although task force planners viewed San Carlos as the most obvious choice, the Argentinians did not consider it as a likely option. The Argentinians correctly believed that Stanley was the British’s likely objective on the Falklands and planned a defense around that area. This made the British landing at San Carlos a stunning success with total surprise achieved. The landings commenced as planned and without significant error. The error that did exist came in the form of poor stowage of the Rapier missile batteries aboard the anchored ships and overall human delay due to insufficient chances and time to train and rehearse landing scenarios at Ascension Island or at sea. The picket line of warships served their intended purpose by Commodore Clapp by absorbing the majority of aerial bombardment from Argentinian aircraft instead of striking the landing ships. The landing forces’ swift and sudden claim over the surrounding ridges prevented any counterattack and gave them time to regroup, install defenses, and plan their assault further into the mainland.

Lessons

The amphibious operation at San Carlos as part of the Falklands War provides many lessons for the contemporary discussion on amphibious operations. The British did not have a single unified commander for the operation. This was only a mild inconvenience due to the good-natured and cooperative characteristics of the four commanders involved in the British task force.115 However, having no unified commander to direct and coordinate naval and marine elements synchronously during amphibious operations exponentially increases the risk of failure. Furthermore, the Falklands War also describes how intricate naval and amphibious operations are intertwined. A naval campaign could not have taken the Falklands back physically and neither could amphibious operations conduct at all had the naval campaign and subsequent goals of sea dominance not been achieved by the time of the landing. Even with naval dominance achieved, the amphibious campaign at San Carlos suffered from its own shortcomings.

The British government highlights its approval of the San Carlos site as a proper fit to their parameters and preferred way of war, landing unopposed and with surprise achieved. This assertion is not contested, although this method of operation was also entirely selected due to the reality that the British had insufficient amphibious assault vehicles and necessary equipment required for a contested landing and the specialized operations that exists in amphibious warfare.116 Aerial amphibious landings via helicopter transports were also an option in this period of amphibious warfare. But the British were unable to conduct this method of landing in mass due to a shortage of helicopters and helicopter transport vessels in the British arsenal. The decision to land at San Carlos instead of Stanley also drew out the conflict perhaps unnecessarily. It is debatable whether casualties would be less or not had they proceeded with a direct assault on the defended beaches of Stanley but drawing out the conflict allowed further Argentinian aerial operations to continue and achieve success. From the Argentinian perspective, the onset of winter was fast approaching, and they only needed two weeks before an amphibious landing could no longer launch. By not challenging British naval forces more aggressively with their own naval forces and failing to understand the preferred British methods of amphibious operations, the Argentinians ultimately failed at delaying the British long enough for weather to decide the fate of the Falklands. It is possible that simple defenses such as sea mines at San Carlos or throughout the Falkland Sound may have eliminated the selection of San Carlos altogether and delayed the landing at the alternate site long enough to where a landing was no longer feasible.

Today’s armed forces can learn from the Falkland’s War and the story of San Carlos with regard to the current capability status and deployment of amphibious forces with respect to the likely areas around the world that would require such forces. Furthermore, the Falklands War is perhaps the greatest example of immediate logistics practice and usage of modern naval warfare to this day. From the defender’s perspective, the actions and defenses at San Carlos and East Falkland Island during the Falklands War is an example of perhaps how not to defend an island with multiple inlets and chokepoints. Furthermore, the Argentinian armed forces acted without appropriate interservice cooperation and lacked a central intelligence network that may have better informed defense commanders of the Britain’s likely landing site.

The story of San Carlos is yet unfinished and requires further analysis when more or all reports on the Falklands War are accessible to the public. In historical terms, the Falklands War is relatively new. Only time and further analysis will reveal the full story of the San Carlos landing and further explain why British task force planners selected it for an amphibious assault.

Endnotes

1. Max Hastings and Simon Jenkins, The Battle for the Falklands, 1st American ed. (New York: W. W. Norton, 1983), 86–88.

2. Hans M. Kristensen et al., “Status of World Nuclear Forces,” Federation of American Scientists, 29 March 2024.

3. Michael Clapp and Ewen Southby-Tailyour, Amphibious Assault Falklands: The Battle of San Carlos Water (Barnsley, UK: Pen & Sword Books, 1996), 35.

4. Hastings and Jenkins, The Battle for the Falklands, 78.

5. Julian Thompson, No Picnic: 3 Commando Brigade in the South Atlantic: 1982 (Glasgow: Fontana, 1986), 17–18.

6. Theodore L. Gatchel, At the Water’s Edge: Defending against Modern Amphibious Assault (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 1996), 192.

7. PREM19/613 f62, Prime Ministerial Private Office files, 20 March 1982.

8. Martin Middlebrook, Operation Corporate: The Falklands War, 1982 (London: Viking, 1985), 41.

9. Hastings and Jenkins, The Battle for the Falklands, 73.

10. “Falkland Islands,” House of Commons Debate, 3 April 1982, vol. 21, cc633-68.

11. Hastings and Jenkins, The Battle for the Falklands, 96–98.

12. Clapp and Southby-Tailyour, Amphibious Assault Falklands, 50.

13. Clapp and Southby-Tailyour, Amphibious Assault Falklands, 54.

14. Clapp and Southby-Tailyour, Amphibious Assault Falklands, 43.

15. Clapp and Southby-Tailyour, Amphibious Assault Falklands, 63.

16. Hastings and Jenkins, The Battle for the Falklands, 91–92, 121.

17. Hastings and Jenkins, The Battle for the Falklands, 123.

18. Hastings and Jenkins, The Battle for the Falklands, 61.

19. Thompson, No Picnic, 18.

20. Harry D. Train II, “An Analysis of the Falkland/Malvinas Islands Campaign,” Naval War College Review 41, no. 1 (Winter 1988): 41.

21. Hastings and Jenkins, The Battle for the Falklands, 91, 133.

22. Hastings and Jenkins, The Battle for the Falklands, 78.

23. Cedric Delves, Across an Angry Sea: The SAS in the Falklands War (Oxford, UK: C. Hurst, 2019), xxi, 113.

24. Personal and party papers, Falklands: Sherman minute to MT, 2.

25. Sandy Woodward and Patrick Robinson, One Hundred Days: The Memoirs of the Falklands Battle Group Commander (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 1992), 92.

26. Martin Middlebrook, The Fight for the “Malvinas”: The Argentine Forces in the Falklands (London: Penguin, 1989), 63.

27. Middlebrook, Task Force, 203.

28. Middlebrook, Task Force, 203–4.

29. Middlebrook, Task Force, 224.

30. Woodward and Robinson, One Hundred Days, 93.

31. Gatchel, At the Water’s Edge, 189.

32. David Brown, The Royal Navy and the Falklands War (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 1987), 114.

33. An Examination of Argentine Air Effort during the Falklands Campaign (London: British Operational Research Branch, 1982).

34. Brown, The Royal Navy and the Falklands War, 114.

35. Gatchel, At the Water’s Edge, 194.

36. Gatchel, At the Water’s Edge, 189.

37. Hastings and Jenkins, The Battle for the Falklands, 116.

38. Gatchel, At the Water’s Edge, 195.

39. Gatchel, At the Water’s Edge, 195.

40. Woodward and Robinson, One Hundred Days, 223.

41. Delves, Across an Angry Sea, 133.

42. Delves, Across an Angry Sea, 170–74.

43. Delves, Across an Angry Sea, 187.

44. Hastings and Jenkins, The Battle for the Falklands, 183.

45. Gatchel, At the Water’s Edge, 192.

46. Edgar O’Ballance, “The Falklands: 1982,” in Assault from the Sea: Essays on the History of Amphibious Warfare, ed. Merrill L. Bartlett (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 1993), 429.

47. Hastings and Jenkins, The Battle for the Falklands, 91.

48. Gatchel, At the Water’s Edge, 192.

49. Clapp and Southby-Tailyour, Amphibious Assault Falklands, 53–54.

50. Thompson, No Picnic, 21.

51. Clapp and Southby-Tailyour, Amphibious Assault Falklands, 79.

52. Clapp and Southby-Tailyour, Amphibious Assault Falklands, 78.

53. Thompson, No Picnic, 22.

54. Woodward and Robinson, One Hundred Days, 84.

55. Woodward and Robinson, One Hundred Days, 90.

56. Thompson, No Picnic, 24.

57. Rubén Oscar Moro, The History of the South Atlantic Conflict: The War for the Malvinas (New York: Praeger, 1989), 181.

58. Thompson, No Picnic, 22.

59. Thompson, No Picnic, 22.

60. Thompson, No Picnic, 35.

61. Thompson, No Picnic, 23.

62. Thompson, No Picnic, 23.

63. Thompson, No Picnic, 21–22.

64. Thompson, No Picnic, 22.

65. O’Ballance, “The Falklands: 1982,” 432.

66. Brown, The Royal Navy and the Falklands War, 183.

67. Clapp and Southby-Tailyour, Amphibious Assault Falklands, 80.

68. Gatchel, At the Water’s Edge, 196.

69. Thompson, No Picnic, 32.

70. Middlebrook, Task Force, 196.

71. Clapp and Southby-Tailyour, Amphibious Assault Falklands, 78.

72. Thompson, No Picnic, 22.

73. Brown, The Royal Navy and the Falklands War, 174.

74. Clapp and Southby-Tailyour, Amphibious Assault Falklands, 77.

75. Clapp and Southby-Tailyour, Amphibious Assault Falklands, 80.

76. Clapp and Southby-Tailyour, Amphibious Assault Falklands, 78.

77. Clapp and Southby-Tailyour, Amphibious Assault Falklands, 79.

78. Clapp and Southby-Tailyour, Amphibious Assault Falklands, 79.

79. Hastings and Jenkins, The Battle for the Falklands, 184.

80. O’Ballance, “The Falklands: 1982,” 432.

81. Gatchel, At the Water’s Edge, 192.

82. Middlebrook, Task Force, 199.

83. Brown, The Royal Navy and the Falklands War, 176.

84. Hastings and Jenkins, The Battle for the Falklands, 186.

85. Thompson, No Picnic, 43.

86. “UK-ARGENTINA: Probable British Strategy,” National Intelligence Daily (Cable), CIA, 24 May 1982.

87. Thompson, No Picnic, 35.

88. O’Ballance, “The Falklands: 1982,” 430.

89. Dave Winkler, “Vice Admiral Hank Mustin on New Warfighting Tactics and Taking the Maritime Strategy to Sea,” Center for International Maritime Security, 29 April 2021.

90. Middlebrook, Task Force, 199.

91. O’Ballance, “The Falklands: 1982,” 430.

92. Woodward and Robinson, One Hundred Days, 230.

93. Clapp and Southby-Tailyour, Amphibious Assault Falklands, 80.

94. Clapp and Southby-Tailyour, Amphibious Assault Falklands, 70.

95. Brown, The Royal Navy and the Falklands War, 183.

96. Kenneth L. Privratsky, Logistics in the Falklands War (Barnsley, UK: Pen and Sword, 2014), 106.

97. Gatchel, At the Water’s Edge, 197–98.

98. Privratsky, Logistics in the Falklands War, 108.

99. Thompson, No Picnic, 38.

100. Hastings and Jenkins, The Battle for the Falklands, 185.

101. Privratsky, Logistics in the Falklands War, 105, 108.

102. O’Ballance, “The Falklands: 1982,” 432.

103. Woodward and Robinson, One Hundred Days, 240.

104. Clapp and Southby-Tailyour, Amphibious Assault Falklands, 80.

105. Thompson, No Picnic, 22.

106. Middlebrook, The Fight for the “Malvinas,” 62.

107. Hastings and Jenkins, The Battle for the Falklands, 122.

108. Woodward and Robinson, One Hundred Days, 90.

109. Thompson, No Picnic, 17.

110. Clapp and Southby-Tailyour, Amphibious Assault Falklands, 77.

111. Hastings and Jenkins, The Battle for the Falklands, 163.

112. Middlebrook, Task Force, 199.

113. Gatchel, At the Water’s Edge, 192.

114. Privratsky, Logistics in the Falklands War, 106.

115. Gatchel, At the Water’s Edge, 191.

116. Gatchel, At the Water’s Edge, 201–2.