Jonah Carlson

https://doi.org/10.21140/mcuj.20241502006

PRINTER FRIENDLY PDF

EPUB

AUDIOBOOK

Abstract: Ansar Allah, known as the “Houthi movement,” has conducted attacks on ships transiting the Red Sea since October 2023. This event is now known as the “Red Sea Crisis.” Classifying Ansar Allah as merely an Iranian proxy, or categorizing its actions as a mere response to the conflict in Gaza and support for Hamas, inadequately explains these attacks. This article uses the cultural topography method to analyze the culture of the movement and provide alternative motivations for the attacks, such as consolidating domestic support and crafting a strong national appearance. The article concludes that Ansar Allah’s attacks on the Red Sea are more motivated by the belief they will yield pragmatic and material benefits for the movement rather than ideological or cultural overlap with Palestine or Iran.

Keywords: Israel, Red Sea, Gaza, Hamas, Yemen, Houthi, Iran

Since October 2023, Ansar Allah, also known as the “Houthi movement,” has conducted drone and missile strikes on various ships traversing the Red Sea, significantly disrupting global shipping. This event has become known as the “Red Sea Crisis.” While one may attempt to quickly categorize Ansar Allah as merely another Iranian proxy group or a militant group responding to the ongoing conflict in Gaza, this understanding is inadequate to explain both Ansar Allah’s ongoing aggression and the potential for future action. Rather, a more complete vision of Ansar Allah understands it as a Yemeni national movement with deep domestic and regional interests that are distinct from current events in Gaza. As a result of these interests, the group is likely to continue its attacks against ships traversing shipping routes near the Middle East regardless of an outcome to the Gaza conflict.

Ansar Allah leadership advertises a robust connection between maritime attacks and the plight of Palestinians in Gaza. Between October 2023 and April 2024, Ansar Allah leadership posts and newspaper publications focused most of their rhetoric on this connection. As Ansar Allah spokesman Mohammad Abdul Salam put simply on X, “The attacks in the Red Sea are related to the war in Gaza.”1 An examination of the internal culture of Ansar Allah, however, reveals a more complicated set of motivations for the movement’s military aggression, many of which will persist beyond a resolution of the Gaza conflict. Based on this research data, this article argues that the war in Palestine is not the primary motivator for the movement’s attacks on the Red Sea. Rather, sympathizing with the Palestinian cause is being employed as a cultural signal for Yemenis and others in the Middle East with the aim of bolstering support for Ansar Allah, both domestically and across the region.

While the conflict in Gaza provides Ansar Allah with a pretext for its attacks, its motivations for orchestrating attacks on the Red Sea and aggravating the United States predate and far exceed the current Israel-Palestine conflict. Palestine acts as a cover for Ansar Allah to pursue its will to craft a powerful Yemeni nation and combat the perceived enemies of that nation, such as the United States. Ansar Allah’s leadership sees the United States as the world’s “Greatest Satan,” an exploitative and imperialist state that threatens the Yemeni people and sees the Middle East as a playground for military escapades. Accepting Ansar Allah’s Gaza rational as an explanation for the group’s attacks encourages an inaccurately narrow lens on the movement’s decision making and invites miscalculations regarding the group’s perception of victory and end goals for aggression.

Methodology: Cultural Topography

The research that underpins this article was conducted via the cultural topography method. This method, developed by Jeannie L. Johnson and Matthew T. Berrett, codes data from primary and secondary sources to identify critical cultural traits that influence the behavior of actor groups. Primary sources informing the research include 83 articles published by Al-Masirah, an Ansar Allah-controlled Yemeni newspaper, during a four-month period; 112 posts published on X by Mohammad Abdul Salam, spokesman for Ansar Allah; and educational material, both formal and informal, for children and young adults acquired from Ansar Allah by Itam Shalev between 2015 and 2019. These primary sources have been combined with a variety of secondary sources, including both Western and non-Western reporting and analysis of the Red Sea Crisis and Ansar Allah, declassified military intelligence data from the U.S. Defense Intelligence Agency and third-party analyses of Iranian military contributions to the movement, and reports on the history, demographics, and public opinion of Yemen and its citizenry.2

Al-Masirah articles were acquired in English translation on the Al-Masirah website, Salam’s posts on X were translated using the website’s built-in translation feature, and educational material was translated by Itam Shalev as part of a project with Impact-SE.3 The sources selected primarily reflect the identities, norms, values, perceptual lens, and motives of Ansar Allah’s elite, which will be referred to in this article as “Ansar Allah,” rather than most of the group’s fighting force. The perspective of the elite offered here will be most useful when combined with work by other scholars examining Ansar Allah’s non-elite forces and other Yemeni groups.

Research within the cultural topography method is conducted using a modified form of Grounded Theory, employing four primary categories: identity, norms, values, and perceptual lens.

• Identity entails traits the group in question aspires to and applies to itself.

• Norms entail both accepted and expected modes of behavior within the group.

• Values entail behaviors or material possessions that increase the status of a group member.

• Perceptual lenses entail the filter through which a group determines its worldview and “facts” about other groups.4

The approach recognizes the inadequacies of purely realist and rational frameworks in explaining actor behavior, both inside and outside of the security space. While rationality often plays a key role in decision making, such rationality is bounded by culture. The influence of culture has been historically downplayed by analyses related to intelligence, defense, or other forms of security both at national and subnational levels.5

When utilizing the cultural topography method, however, it is also important to recognize when cultural factors are insufficient to explain the behavior and motivations of a group. Culture is not the end-all-be-all of behavior. The constructivist perspective of cultural topography is designed to supplement, not supplant, the realist perspectives that place a greater emphasis on material interests. For instance, as will be discussed later in the article, the data that informs this article does not support the idea that cultural traits are the primary motivation for Ansar Allah’s cooperation with Iran. Beliefs do not unite Iran and the Houthis: arms and enemies do. While this article primarily focuses on the importance of culture in understanding the Red Sea Crisis, it will necessarily include the operational realities that inform Ansar Allah’s decision making as well.

Understanding Culture and Policy as “Mutual Constructions”

The cultural topography method is used to conduct a thorough examination of how culture influences actors’ behavior and outcomes. This directionality—viewing culture as an agent shaping policy—is necessary for a holistic “all source” assessment of problem sets and is thus far systematically understudied in U.S. security spaces.6 Conversely, however, one must also examine how behavior and policy capitalize on and transform culture. Johnson and Berrett are critical of perceiving cultures as static entities. Acknowledging this criticism, one should recognize that culture does not simply influence policy, but policy also influences culture over time; the two are, to borrow parlance from Colin Flint, “mutually constructed.”7

Mutual construction can be observed in the rhetoric, behavior, and cultural traits of Ansar Allah. While Ansar Allah’s behavioral policy is motivated by critical cultural factors such as Yemeni national identity and a siege mentality that encourages resisting perceived oppressors, the movement’s elites also capitalize on other cultural preferences and motivators found among their Yemeni base and use those motivators to justify their behavior and reinforce the legitimacy of their strong position in the country. Rhetorical support for the Palestinian cause is an example of one such cultural preference, justifying Ansar Allah’s action on the Red Sea despite a weak relation between the ships the movement claims to target and the ships it actually attacks. All policy and rhetoric carry with it a level of ideological power that transforms what behavior is deemed acceptable. Culture does the same to policy, shaping which policies are deemed acceptable or overreaching. Ansar Allah’s rhetoric carries a level of ideological power and attempts to utilize the identity and perceptual lens of the wider Yemeni population to reinforce the policies underpinning the Red Sea Crisis.

Literature Review

Utilizing the cultural topography method in this research article provides a unique perspective on the motivations and current behavior of Ansar Allah. As will be observed in this section, most work discussing the movement published within the last decade focuses heavily on the connection between the movement and Iran. As a result, the relationship between Iran and Ansar Allah will be the subject of much of this literature review. However, while this article investigates Iranian contributions to Ansar Allah’s operational realities, it primarily examines the group’s behavior as being motivated by internal factors. Additionally, while earlier works on Ansar Allah place focus on the movement’s sectarian religious identity, this article examines the current iteration of Ansar Allah’s internal culture, which has evolved and taken on distinctive qualities beyond the Shi’ite identity of the movement’s founders.

Literature providing analysis of Ansar Allah, both from traditional academic sources and works designed for policy audiences, can be divided into two categories: works from before the outbreak of the Yemeni Civil War and works from after that conflict began. Scholarship predating the conflict typically puts an emphasis on Ansar Allah (though the movement did not use that name at the time; the name “Believing Youth” was still partially used, though some publications simply referred to the movement as “rebels”) as a religious movement with political motivations and ideological values associated with Zaydi Shi’ism.8 Little mention is made of Iranian contributions to the movement’s efforts, and when these are mentioned, a connection between the two parties was considered either minimally evidenced or to not involve the provision of arms.9 Cooperation between Iran and Ansar Allah was considered a noncrucial factor in analysis even in the years just before the Arab Spring. Jack Freeman, for example, wrote as late as 2009 that “because of the abundance of weapons in Yemen, [Houthi] insurgents have no need for that type of support.”10 Furthermore, Christopher Boucek asserted in 2010 that “a Saudi-Iranian regional rivalry is not playing out in Saada” and that if there was any connection between Iran and Ansar Allah, it likely involved only minimal funding.11

Since the outbreak of the Yemeni Civil War, the discourse has evolved to adapt to new realities. Most scholarship and policy writing make some reference to Ansar Allah’s role as a participant in a proxy conflict between Saudi Arabia and Iran.12 A majority of analyses have reduced the previously important nature of the movement’s Zaydi identity, swapping it for explanations focused on political ambitions, both domestic and foreign, and dropping culturally focused approaches in favor of more realist ones. Significantly less importance is put on religion and other cultural factors in examinations of the movement written following 2011.13 What remains debated by scholars is the extent to which Iran is involved in shaping Ansar Allah’s actions, as well as the extent of the interplay between their actions.

The spectrum of perspectives on Iranian involvement is extremely varied. Take Uzi Rubin, for example, who asserts that Ansar Allah’s strikes on Saudi Arabia are “camouflage” by which Iran can conduct war; he draws little distinction between what makes one attack from Yemen “Houthi” and another “Iranian.”14 On the other end, Marxist scholar Jude Kadri makes almost no note of Iranian influence or contributions to Ansar Allah in her analysis of the Yemeni Civil War, instead suggesting that the group’s military actions against the Saudi coalition are a response to “imperialist” forces, like the United States and Saudi Arabia, attempting to reduce Yemeni sovereignty.15 Most work from other scholars draw conclusions between these two spaces, determining that an interplay of both Ansar Allah’s and Iran’s interests and capabilities help explain the nature and extent of Ansar Allah’s action during the war. Furthermore, many authors agree that cooperation between the movement and Iran is driven merely by an overlap of interests rather than ideological common ground. Though acknowledging that ideological overlaps “may follow in time,” Elisabeth Kendall put it most plainly in 2017: “It seems likely that the Houthis have a pragmatic attitude towards Iran. They are willing to accept help in their fight as long as it suits them.”16

This article agrees with scholars such as Kendall who assess that Iran-Houthi cooperation is the result of both group’s pragmatism and aims to avoid merely restating this hypothesis. Rather, the research presented here provides a constructionist view of Ansar Allah that demonstrates the boundaries of cultural influence on the movement’s behavior and policies, and vice versa. Thomas Juneau wrote in 2021 that Ansar Allah’s influence had grown so significantly over the course of the Yemeni Civil War “that it is now possible to refer to Houthi foreign policy.”17 This article contributes to that line of thinking by supplying the cultural factors that are most prominent in developing and signaling that policy.

Ansar Allah’s New Cultural Priorities Supplant Purely Religious Goals

Much literature has been published recounting the history of the “Houthi movement,” and as a result this article will avoid spending much time on the subject. However, a cursory view of the evolution of the movement is worthwhile from the perspective of cultural topography, as the movement’s history exemplifies how the priority of cultural traits shifts over time, known within the methodology as “flux.”

The Houthis can trace their genesis back to an earlier movement known as “Believing Youth,” which began in the early 1990s. This movement had express cultural aims: to bolster both the cultural and political influence of Zaydi Shi’ism within the newly reunited Yemen.18 To understand the need for that revival, one must look back to the 1960s. Despite being a minority in Yemen, comprising roughly a third of the country’s population (with the remainder of the population being Sunni Muslims), the Zaydi Shi’ites of Yemen held immense political influence over the country for most of its history.19 Zaydi imamates intermittently controlled parts of the country for nine centuries. Their overthrow in a revolution in 1962 led to the formation of the Yemen Arab Republic in the north and resulted in a civil war that split the country in two for most of the remainder of the century.20

Believing Youth hoped to revive that influence following Yemen’s unification. Despite the newly crowned president of Yemen, Ali Abdullah Saleh—who would impose authoritarian rule over the country for nearly 30 years—being a Zaydi, Believing Youth found themselves increasingly dissatisfied with his level of support for increased Zaydi influence.21 That dissatisfaction only grew more apparent once Hussein al-Houthi joined the movement.

The growing radicalism of Believing Youth during al-Houthi’s membership demonstrates the influence he had on the group’s ideology. Saleh, perceiving al-Houthi and the increasingly militaristic movement as a threat, had al-Houthi killed by government forces in 2004.22 At this point, Believing Youth evolved into a full-fledged insurgency against Saleh’s government. Much of the ensuing fighting took place in the country’s north, in and around the city of Sa’ada. Hussein Al-Houthi’s brother took over leadership, cementing the family’s influence over the movement, which by that point had become so powerful the movement could be recognized by the family name alone.23 He continues to lead the organization today.

In 2012, the Arab Spring launched Yemen into revolution, which resulted in the overthrow of Saleh’s regime and collapse into civil war. It is around this time that the Houthi movement took on an official name, Ansar Allah—“Supporters of God.”24 Since the outbreak of the war, Ansar Allah has attempted to coercively consolidate its power over Yemen. The movement took over the capital of Sana’a in 2014, and since have only expanded their influence, today controlling a land area containing roughly 80 percent of the country’s total population.25 Ansar Allah’s cultural motivators and signaling have evolved over this period as the result of newfound influence and responsibility. Zaydi Shi’ite revivalism, while almost certainly still a factor in elite thought, has fallen to the backburner after decades of conflict both internal and external. This root cultural identity has been supplanted by cultural traits more politically charged: namely, Ansar Allah’s identity and perceptual lens as Yemen’s defender against imperialist siege, and their position as the leaders of the burgeoning Yemeni nation.

Nationalism, Resisting Foreign Influence Stronger Motivations for Maritime Attacks than Palestine

Ansar Allah has repeatedly used the ongoing conflict in Gaza as a signaling device with which to cover its action on the Red Sea. Multiple attacks exemplify how Ansar Allah is willing to attack ships indiscriminately, without regard for national origin or relation to Israel, contrary to their claims. While Ansar Allah leadership likely feel some culturally motivated sympathies toward Palestine themselves, their rhetorical focus on the conflict primarily disguises the critical cultural factors that motivate continued action on the Red Sea: namely, bolstering the nation of Yemen under Ansar Allah’s leadership while deterring the “Greatest Satan”—the United States—and its allies that resist the movement militarily.

Palestine Used as Cultural Signal—Message Resonates with Yemeni Public, Iranian Benefactors

Sympathies toward Palestine are founded in large part on regional identities. The shared Arab and Islamic identities between Yemen and Palestine are frequently brought to light by Salam in spokesman posts. These shared identity traits are also used to critique Arab states, such as Saudi Arabia and the UAE, deemed as insufficiently aligned with the Palestinian cause. These states are also the perceived aggressors against Ansar Allah in the Yemeni Civil War. In one scathing example from 5 November 2023, Salam declared a state of “Arab apostasy” due to lack of regional support for the “Al-Aqsa Flood,” the title given to Hamas’s attacks orchestrated on 7 October.26 Al-Masirah articles also hearken to this shared Arab and Islamic identity and emphasize shared values that emerge as a result of these identities.27 Critiquing neighboring states on this issue helps Ansar Allah appear to stand in a place of moral authority, unlike the states that capitalize upon these shared regional identities to a lesser extent, which seem comparatively out of touch.

As a result of these shared identities, the focus on Palestine comes with political benefits for Ansar Allah. Polling across the Arab world indicates that a majority of individuals in the region “have become certain that there will be no possibility for peace with Israel” or doubt the possibility of future peace.28 Additionally, more than half of those polled thought that the United States was the biggest threat to peace and stability in the Middle East in relation to the Gaza conflict.29 Yemeni support for the Palestinian cause is evident in Salam’s posts: while the number of attendees is almost certainly misreported by Salam, video evidence shows the presence of thousands of Yemenis in Sana’a protesting the ongoing conflict, backed by non-Houthi reporting.30 Holding this pro-Palestinian position rallies Ansar Allah’s political and ideological base around a contemporary issue and increases Ansar Allah’s potential to garner support domestically. Bolstering this support is the goal of the movement’s signaling: one must remember that Ansar Allah is a movement which, while having already accumulated great influence within Yemen, is still fighting a civil war and is not internationally recognized. Garnering support by leveraging shared cultural values is one method by which to increase perceived legitimacy, both abroad and at home.

Ansar Allah’s support of Palestine also comes with tangible benefits outside of domestic support. Palestine and Ansar Allah both share a common adversary, Israel, with a major regional benefactor: Iran. All of Iran’s major adversaries—the United States, Israel, and Saudi Arabia being the most notable—overlap with the adversaries of Ansar Allah. The extent of this overlap in adversaries, combined with the military support received, appears to have heavily contributed to the perception of Ansar Allah as an Iranian proxy, especially among Western news sources. Yet, Ansar Allah is not merely pandering to Iran. Rather, Ansar Allah’s signaling is a tool used to acquire the capabilities necessary to promote a stronger Yemeni nation and deter the perceived enemies of Ansar Allah, and thus boost Yemen’s strength. The precise nature of the Houthi-Iranian relationship will be further explained in later sections.

Cultural Motivators: Fighting “Greatest Satan” and Building Domestic Legitimacy, Support

Ansar Allah uses the relationship between the United States and Israel to justify its military actions on the Red Sea as solidarity with Palestine, both in Al-Masirah articles and spokesman posts. However, anti-American sentiment on the part of Ansar Allah not only predates the current conflict in Gaza by at least a decade, it is also a central element of the movement’s worldview. This perceptual lens can be seen in youth educational material distributed by the movement between 2015 and 2019, in which America is specifically described as the “Greatest Satan,” undermining the security of not only Yemen but its neighbors.31 From this “Greatest Satan” position, the United States is accused of playing the role of puppet master over Ansar Allah’s other enemies. The United States is described as the puppet master of Israel, or Israel as the protegee of America, in posts by Salam and in educational material.32 This “Greatest Satan” framework is also used to articulate sectarian differences between Ansar Allah and the Sunni extremist movements that make up their enemies. The United States is described as the mastermind behind the Islamic State: educational material describes the group as the product of American intelligence and Salam’s posts

depict the movement as being “American-manufactured.” 33 Ansar Allah’s anti-American sentiment is perhaps most obvious in a portion of the group’s motto, which, in red lettering, states simply: “Death to America.” The slogan was popularized by Iranian Supreme Leader Ruhollah Khomeini following the Iranian Revolution of 1979, indicating some agreement between the two on their anti-American sentiments. However, the movement adopted this part of the slogan after the U.S. invasion of Iraq in 2003, demonstrating how U.S. action itself has played into the creation of the “Greatest Satan” perception.34 In sum, from Ansar Allah’s perspective, the totality of threats faced by Yemenis can trace their roots back to America.

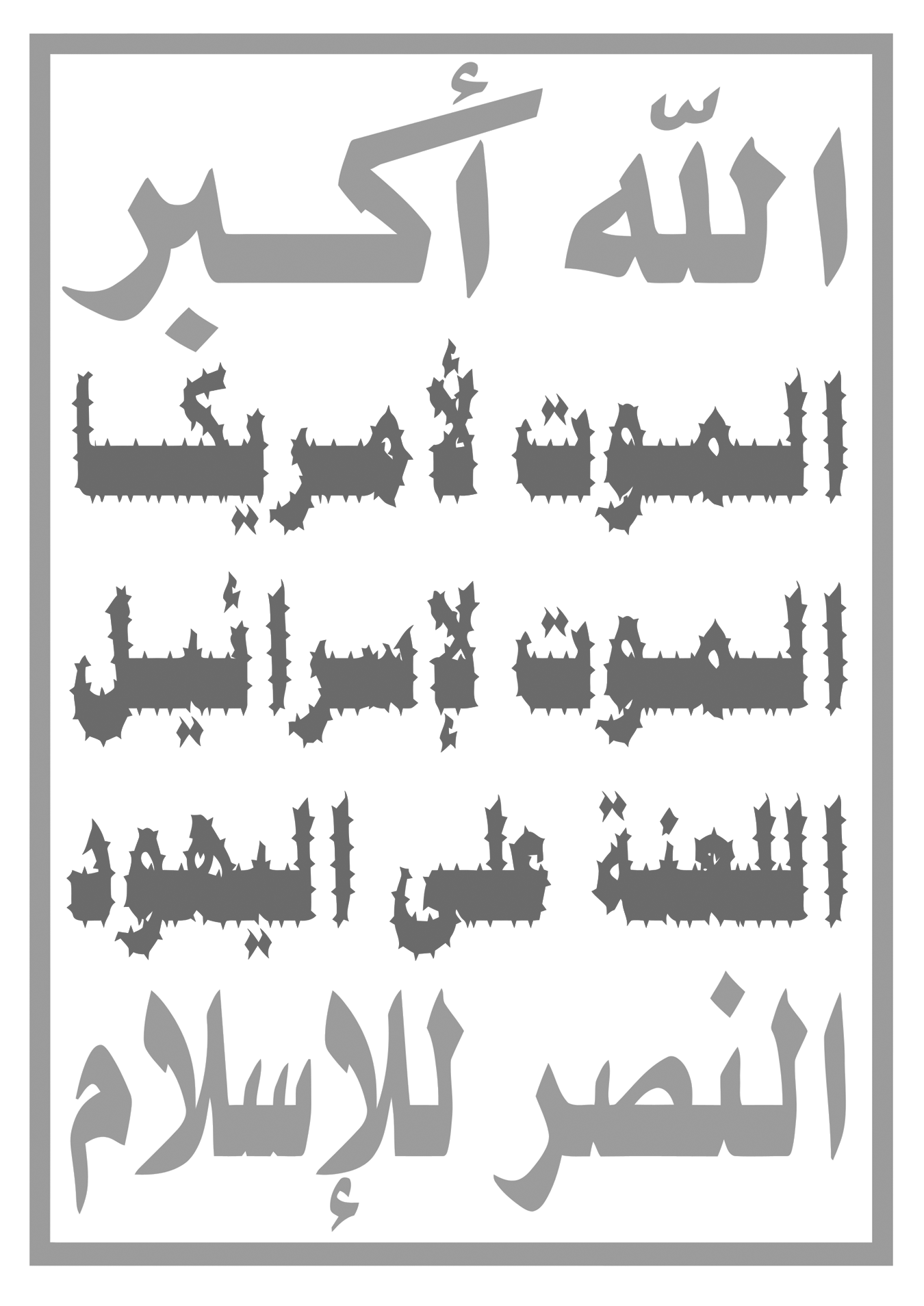

Figure 1. Ansar Allah’s slogan. The text reads: “Allah is the Greatest – Death to America – Death to Israel – A Curse upon the Jews – Victory to Islam”

Source: courtesy of RuneAgerhus, adapted by MCUP.

This perception of America as the “Greatest Satan” hyperbolizes a more common perception rooted in Yemen’s recent history. Tensions between Yemen and Saudi Arabia have encouraged this negative perception of the United States. Saudi Arabia has been viewed as a constant meddler in Yemeni politics, reaching well before the Yemeni Civil War, and has also been a uniting factor for Yemenis.35 The United States, as an ally in Saudi Arabia’s coalition and a key supplier of weaponry, is likely not viewed as a neutral actor by many Yemenis affected by the conflict, especially those in Ansar Allah controlled regions, where the most airstrikes have occurred.36

Saudi intervention in the civil war has upended lives across the country and driven Yemenis to back Ansar Allah. In 2022, a survey conducted by Resonate! Yemen and the Public International Law and Policy Group showed that more than one-half of Yemenis polled described the security situation constructed by Ansar Allah as “good” during the previous year. That is not to say the Yemenis polled were entirely pleased with Ansar Allah’s governing position—many raised concerns regarding their ability to voice dissent against the movement, claiming that Ansar Allah’s governance was a detriment to “individual security.” Yet, despite these concerns, Ansar Allah’s approach was perceived as a way to escape the “lawlessness” produced by the civil war and coalition airstrikes.37

The perceived cruelty of the Saudi-led coalitions efforts against Yemen is evidenced across Ansar Allah’s educational material, demonstrating the extent to which anger and opposition to foreign actors involved in the Yemeni Civil War has become a cultural narrative among the elite. Materials not only directly call out the involvement of Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, and the United States in the conflict but also paint vivid pictures of the destruction they have caused. Brutal images of bodies killed in airstrikes, both real and illustrated, are displayed with sorrowful captions.38 At the same time, educational material calls for a response to these actions. Multiple comic strips call for both youth and adults to fight this aggression against the “motherland,” simultaneously promoting the perception of a Yemeni nation united against foreign siege.39 These educational materials serve as a call to action that compels young Yemenis affected by the war to join Ansar Allah’s ranks. They inflame the anger many Yemenis feel about the destruction of their country and the extent of foreign influence in what began as a domestic conflict. Then, the materials provide a potential method by which Yemenis can not only save themselves and their families, but also their country: fighting the foreign aggressors, including the “Greatest Satan” that backs them economically and militarily. This fighting is promoted as a cultural value within Ansar Allah and helps produce a loose “anti-imperialist” identity. Similarly, Ansar Allah promotes an “anti-imperialist” identity among both its own forces and Yemenis within its area of governance: the education material it disseminates includes guides such as how to properly deter the aggression of “imperialist” and “colonialist” powers while also stipulating that it is the duty of Yemeni men to fight such forces.40 Ansar Allah’s current action on the Red Sea is an actualization of this identity, capitalizing on the cultivated value of resistance and the perceptual lens that frames the United States, allied Western powers, and neighboring states as oppressors.

Non-Gaza Motivators: Bolstering the Yemeni Nation, Encouraging Iranian Military Contributions

This examination of the evolution of the internal culture of Ansar Allah, and the militant narratives it is cultivating in the wider Yemeni population, indicate that an outcome to the conflict in Gaza in the short- or medium-term is unlikely to encourage Ansar Allah to stop its attacks against ships on the Red Sea. While Palestine plays an important role in helping Ansar Allah signal to both domestic and international audiences, the group’s action is ultimately driven by a combination of domestic interests and cultural motivators outside of the Gaza context. In addition to the cultural will to fight the “Greatest Satan” and other foreign forces, Ansar Allah aspires to make Yemen a recognized regional player; they perceive the country as a “rising underdog” with the influence to reshape the geopolitical landscape of the Middle East. This concept is repeated in articles published by Al-Masirah, as well as in spokesperson posts made by Salam. To continue promoting this perception of the Yemeni nation as rising in influence, Ansar Allah will continue to draw international and domestic attention through orchestrating attacks.

Thus far, Ansar Allah perceives its actions on the Red Sea as immensely successful. The group has stifled global trade through the Suez Canal, with shipping through that route dropping by more than 50 percent in 2024 compared to a year earlier.41 Articles from Al-Masirah celebrate the effect of the action on Yemen’s adversaries repeatedly, sometimes focusing only minimally on the additional Palestinian context. The success in disrupting global shipping and undermining the interests of the “Greatest Satan” give Ansar Allah an increased level of legitimacy—not as a legitimate government, per se, but as a force to be taken seriously in both domestic and international contexts. Through its Red Sea action, Ansar Allah demonstrates that its irregular warfare tactics can go toe-to-toe with some of the world’s most formidable militaries. This promotes Yemen’s image as an influential state, further cultivating the “underdog” nationalist identity and motivating disruptive action outside of the Palestinian context.

This desire for increased recognition and legitimacy as a regional actor is further evidenced by the types of vessels that Ansar Allah selects to target, which extend beyond those related to the conflict in Gaza. Both Salam’s posts and articles published by Al-Masirah claim that the movement is only targeting ships with association to Israel, the United States, and the United Kingdom.42 However, reporting from the Red Sea dismisses this claim. Ships with no recognizable connection to the aforementioned states, including a Barbados-flagged ship, a Palau-flagged ship messaging the presence of Syrian sailors, and a Chinese-owned oil tanker called Huang Pu, have been targeted.43 An analysis provided by the U.S. Congressional Research Service states that the movement’s attacks “have not appeared discriminate or linked to stated demands.”44 Additionally, the movement will simply lie about targeting certain vessels. For example, the movement claimed to attack an American vessel known as Ocean Jazz in January 2024, a claim which the United States denied, noting that the ship made a safe transit through the Red Sea.45 Such a claim indicates that signaling that the movement is fighting against the “Greatest Satan” is equally important as actually doing so.

A glance at the ships targeted by the movement indicates no concrete pattern. Ships without a direct connection to Israel appear to be targeted at random. Given that attacks on Red Sea vessels are described as part of both a pro-Palestinian and pro-Islamic mission and thus receive domestic support, the random attacks that accompany attacks against vessels with more obvious relations to Israel likely amount to a militaristic form of attention seeking.

The previously mentioned Chinese-owned oil tanker Huang Pu exemplifies the indiscriminate nature of Ansar Allah’s attacks. Toward the end of March 2024, both Russia and China struck a deal with Ansar Allah that would avoid having their ships attacked in exchange for “political support.”46 Yet the current state of this deal is unclear, as just a few days after Bloomberg reported the deal, U.S. Central Command (CENTCOM) reported that Ansar Allah attacked Huang Pu.47 It remains unclear whether Ansar Allah was aware of the ownership of this vessel, but their willingness to strike it without careful vetting further demonstrates how Israel and Palestine are not the primary motivators of the Red Sea attacks but instead serve as a useful cultural disguise that provides justification for the strikes to the movement’s audiences.48 While keeping up their anti-Israeli rhetoric, Ansar Allah builds popularity domestically by repeatedly flexing its muscles on the water, whether against U.S. and Israeli-associated vessels or not. The attacks on the Red Sea have proven popular domestically, boosting the number of fighters recruited by the movement.49 For Ansar Allah elite, the specific targets of attacks are unimportant, so long as the attacks display regional influence and improve domestic legitimacy.

Iranian Support Significantly Improves Ansar Allah’s Military Capabilities

Ansar Allah has dramatically increased its military capabilities during the course of the Yemeni Civil War. Their ability to conduct military action outside of Yemen’s borders has likely never been easier or more cost effective. This growth is the result of Iranian provision of support and supplies in missile and UAV construction. Deconstructed antiship parts are shipped or smuggled into Yemen and then fully rebuilt for use in Ansar Allah attacks. Evidence points to parts produced in Europe being smuggled into Iran and then provided to Ansar Allah.50

The most effective method of Houthi attacks appears to be the use of one-way unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) laden with explosives. The Yemeni Civil War has produced an extensive, successful record of Ansar Allah UAV attacks against Saudi Arabian targets.51 The movement’s Qasef-1 and Waid-1 models, with ranges of 200 km and 900 km, respectively, are sufficient to conduct strike missions on Red Sea targets.52 Longer range capabilities, such as Waid-2, are capable of covering most of the Middle East and striking targets in countries such as Israel.53 The most capable of the movement’s missiles have similar potential ranges and have already been tested against Israel in a recent attempted attack on Eliat.54 The first fatalities on the Red Sea were the result of Ansar Allah’s ballistic missile attacks on the cargo ship True Confidence, which killed three people.55 While evidence exists that suggests Ansar Allah is developing its own production capabilities, Ansar Allah remains beholden to Iranian design.56 Nearly the entirety of Ansar Allah’s antiship arsenal are near-identical copies of Iranian models.57

Ansar Allah, Iran Relationship Motivated by Shared Interests, Not Shared Culture

This formidable support on the part of Iran has advanced Ansar Allah from a relatively ragtag rebel group to a serious force not only within Yemen but regionally. When the movement took over Sana’a in 2014, what they inherited from the Yemeni military was largely old, Soviet-designed weaponry.58 Iranian-supplied and designed capabilities now allow Ansar Allah to launch explosives to the very edges of the European Union.59 Ansar Allah recognizes the importance of this military aid in allowing the movement to better pursue its own ambitions and cultural preferences. It therefore remains likely to continue backing its Iranian benefactor both rhetorically and militaristically. While Salam’s posts and articles from Al-Masirah largely keep the relationship between the movement and Iran hush-hush—with Salam’s posts denying the existence of Iranian supply lines assisting the movement in one X post and Al-Masirah denying the movement’s position as an “Iranian proxy”—Ansar Allah has also overtly praised or participated in pro-Iranian action.60 In the wake of Iran’s attack against Israel on 13 April 2024, an Ansar Allah spokesman from the movement declared it a “legitimate act.”61 A press release from Israel also indicated that Ansar Allah directly participated in this round of strikes with their own ballistic missile and UAV capabilities.62 Vocal participation in these attacks further signals to Iran that Ansar Allah is an ally worthy of receiving further support.

The cooperation seen between Iran and Ansar Allah is the result of overlapping interests and the “win-win” material outcomes that result from their symbiotic relationship rather than shared cultural identity and values. While Salam’s posts made brief mention of Ansar Allah’s position in the “axis of resistance” in the wake of the 7 October attacks, few other cultural or ideological connections are articulated in rhetoric.63 Ultimately, while the two parties have similar interests in the region currently, the cultural motivators for those interests are different. Yemeni nationalism is a significant cultural motivator for Ansar Allah, one that the Iranian elite do not share. In contrast, literature on Iranian strategic culture places a greater emphasis on the Shi’a Islamic identity of Iran and the country’s own nationalist and self-preservationist desires.64 The cultural link between the two states is not strong enough to deter actions that further their own interests and cultural preferences. Ansar Allah pursues actions that simultaneously align with Iranian interests while furthering the movement’s own cultural preferences: this includes both continuing strikes on the Red Sea and participating in attacks, whether successful or not, against Israel.

Ending the Crisis: Airstrikes Insufficient to Halt Ansar Allah

While strikes against Ansar Allah’s capabilities have the potential to slow the rate of their attacks on the Red Sea, military engagement at current levels is unlikely to encourage the group to cease such action and may instead encourage later retaliation. Saudi Arabia’s recent rounds of negotiation with the movement provide an example of how Ansar Allah is experiencing recent cultural flux, reducing its focus on solely resisting “imperialist” enemies to promoting a strong Yemeni nation, increasing its focus on domestic legitimacy. Furthermore, the negotiations outline how de-escalating violence can potentially lead to successful diplomacy.

The Current State of Play: Civil War Cooling, Ansar Allah Strengthening

Important, first, is to recount the current state of play. As of April 2024, fighting within Yemen has significantly cooled compared to the 2010s. This is the result of United Nations brokered ceasefires and ongoing rounds of negotiations between Ansar Allah and its adversaries.65 While ceasefire agreements within Yemen have proven fragile and are only somewhat upheld, their repeated implementation have assisted in reducing the extent of the fighting.66 A notable element of the negotiation process is the discussions between Saudi Arabia and representatives of Ansar Allah, which began in 2022.67 The on-and-off conversations culminated in the visit of representatives of Ansar Allah to Riyadh in September 2023.68

Despite the cooling state of the war within Yemen’s borders, Ansar Allah continues to execute military action on the Red Sea. Airstrikes conducted on Houthi targets by the United States and United Kingdom appear thus far generally ineffective at deterring further attacks. It is too early to determine the long-term effects of such action: U.S. military officials claim that Ansar Allah’s capabilities may be declining, reducing the pace of their attacks.69 Ansar Allah, meanwhile, continues to claim attacks against Red Sea vessels.70 Between the beginning of the Red Sea Crisis and May of 2024, attacks against ships increased roughly linearly despite retaliatory strikes beginning in February.71 Meanwhile, the effect on global shipping remains acute: passage through the Suez Canal remains reduced, significantly affecting schedules.72

Saudi Arabia Negotiations Provide Potential U.S. De-escalation Framework

While airstrikes against Ansar Allah’s capabilities may reduce their ability to conduct strikes on the Red Sea in the near term, they fail to strike at the identity-value combination that encourages the group to undertake future strikes. Since at least 2015, Ansar Allah has cultivated an identity of Yemenis as a people betrayed and oppressed by their neighbors and other adversaries.73 Simultaneously, the group has promoted armed aggression against these perceived oppressors as a cultural value. This identity-value combination encourages potential recruits to participate in armed resistance against the ongoing siege orchestrated against Yemen. An identity rooted in a sense of betrayal and oppression will not disappear if capabilities are destroyed by airstrikes; more likely, airstrikes will accentuate the identity-value combo that encourages recruits and elite alike to take military action against their perceived oppressors. Attempts to debilitate this identity-value combination using force, trying to “break the will” of the opponent, may backfire. A decade of conflict appears not to have shattered Ansar Allah’s resolve but rather those of everyday Yemenis, leading to the growth of Ansar Allah’s total numbers and a national tolerance for—or, at least, an inability to—resist internal extremism.74 Rather than discourage extremist behavior, excessive military strikes may instead breed the conditions for future extremism.

As a result of the “Greatest Satan” perceptual lens, the United States will struggle to make much diplomatic headway with Ansar Allah regarding the Red Sea Crisis without invoking the assistance of a third party. Even with the assistance of a third party, the stability of a diplomatic resolution is unclear. While Russia and China’s previously mentioned negotiations with the movement demonstrate the ability to bring Ansar Allah to the table, the attack on Huang Pu shows that Ansar Allah’s word is not their bond.75

Recent efforts by Saudi Arabia, however, may provide an example of how the United States can proceed. The rounds of negotiations between Saudi Arabia and Ansar Allah are a noteworthy example of flux on the part of both parties. First, it demonstrates the willingness of Saudi Arabian officials to recognize Ansar Allah’s influence in Yemen and to approach negotiations with an understanding of the movement’s near-term permanence. Second, the willingness for Ansar Allah to negotiate with Saudi Arabian officials—who Salam surprisingly described as “our brothers” in a spokesman post related to the negotiation—demonstrates that the movement’s motivations related to strengthening itself domestically and appearing as Yemen’s protector may outshine its motivations to resist its “imperialist” neighbors militarily.76 Fostering a stable state will be a crucial step for Ansar Allah to secure its legitimacy in Yemen and cultivate the image of safeguarding the nation. This demonstrates a further evolution in Ansar Allah’s internal culture. Core values driving decision-making are shifting away from the ideological domain, deterring “imperialist enemies,” and now emerge most strongly from the national domain, strengthening the nation and the movement’s place within it. The on-and-off ceasefire rounds seen since 2022 likely contribute to this flux, demonstrating how Ansar Allah can pursue its aims without relying on armed tactics.

While strikes against the movement’s capabilities may slow the pace at which they can fight, they fail to encourage Ansar Allah to negotiate with the United States. Additionally, strikes run the risk of promoting an image of instability within Yemen’s borders, which not only pushes Yemenis toward supporting the movement but also feeds the cultural values and perceptual lens its leadership promotes, including the need to resist foreign adversaries militarily. Prolonged military action by the United States and allies ultimately plays into the hands of Ansar Allah and encourages Yemenis to subscribe to its cultural signaling. Gradually slowing the rate of strikes against Ansar Allah targets may provide an opportunity for the United States to leverage the influence of a third party, such as Oman, to outline a pathway for Ansar Allah to pursue its domestic agenda without significantly disrupting U.S. and global economic interests on the Red Sea. Ansar Allah may desire to negotiate in the future to boost perceptions of its own legitimacy, which the movement seeks. Ansar Allah’s influence in Yemen is likely to continue to grow. Clever policy solutions to the Red Sea Crisis will leverage a knowledge of Ansar Allah’s internal culture, aspirational identity, and popular narratives to craft engagement strategies that reduce the domestic rewards Ansar Allah is garnering from Red Sea attacks and amplify the positive international recognition Yemen receives when engaging in diplomatic negotiations.

Endnotes

1. Mohammad Abdul Salam (@Abdusalamsalah), X, 16 January 2024.

2. Jeannie L. Johnson and Matthew T. Berrett, “Improving Analysis Cultural Topography: A New Research Tool for Intelligence Analysis,” Studies in Intelligence (June 2011): 3–4.

3. Itam Shalev and Eldad J. Pardo, Review of Houthi Educational Materials in Yemen 2015–19 (Ramat Gan, Israel: Impact-SE, 2021).

4. Definitions paraphrased from Johnson and Berrett, “Improving Analysis Cultural Topography.”

5. Kerry M. Kartchner, “Defining and Scoping Strategic Culture,” in Routledge Handbook of Strategic Culture (London: Routledge, 2023), 3–16, https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003010302-2.

6. Johnson and Berrett, “Improving Analysis Cultural Topography,” 3–4.

7. Colin Flint, “Putting the ‘Geo’ into Geopolitics: A Heuristic Framework and the Example of Australian Foreign Policy,” GeoJournal 87, no. 4 (February 17, 2021): 2577–92, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10708-021-10387-5.

8. Take the following examples: “Yemen Rebels Say Saudi Air Raids Kill 54,” Reuters, 20 December 2009; and Ellen Knickmeyer, “In Yemen, a Mostly Concealed Sectarian Fight,” NBC News, 7 June 2008. Take the following examples: “[Zaydism] is the movement’s most common and salient characteristic,” from Jack Freeman, “The Al Houthi Insurgency in the North of Yemen: An Analysis of the Shabab Al Moumineen,” Studies in Conflict and Terrorism 32, no. 11 (30 October 2009): 1008–19, https://doi.org/10.1080/10576100903262716; “The Government Is Fighting Shi’i Zaidi Revivalists”; and Christopher Boucek, War in Saada: From Local Insurrection to National Challenge (Washington, DC: Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, 2010). Though published in 2016, Mareike Transfeld describes the origins of Ansar Allah in terms of Zaydi Shi’ism: Mareike Transfeld, “Political Bargaining and Violent Conflict: Shifting Elite Alliances as the Decisive Factor in Yemen’s Transformation,” Mediterranean Politics 21, no. 1 (7 October 2015): 150–69, https://doi.org/10.1080/13629395.2015.1081454.

9. For example, “the state has not yet produced evidence that the Houthi rebels are receiving outside military assistance,” from Boucek, War in Saada; “Iran’s support includes funding, training, and political support to SAM insurgency,” from Jack Freeman, “The Al Houthi Insurgency in the North of Yemen: An Analysis of the Shabab Al Moumineen,” Studies in Conflict and Terrorism 32, no. 11 (October 2009): 1008–19, https://doi.org/10.1080/10576100903262716.

10. Freeman, “The Al Houthi Insurgency in the North of Yemen,” 1008–19.

11. Boucek, War in Saada.

12. Elisabeth Kendall states, “Houthis can be considered part of a broad pro-Iran constellation,” from Elisabeth Kendall, Iran’s Fingerprints in Yemen: Real or Imagined? (Washington, DC: Atlantic Council, 2017); “Iran’s main goal in Yemen is the same as it is regionally . . . to . . . weaken Saudi Arabia,” from Raiman al-Hamdani and Helen Lackner, Talking to the Houthis: How Europeans Can Promote Peace in Yemen (Berlin: European Council on Foreign Relations, 2020); “The conflict between Saleh and the Houthis quickly became part of the regional rivalry between Saudi Arabia and Iran,” from Jean-Loup C. Samaan, “Missiles, Drones, and the Houthis in Yemen,” Parameters 50, no. 1 (Spring 2020); “Iranian goals in supporting the Houthi movement in Yemen inherently challenge Saudi Arabia,” from Robert Springborg, F. C. “Pink” Williams, and John Zavage, “Iranian Security Assistance,” in Security Assistance in the Middle East: A Three-Dimensional Chessboard (Washington, DC: Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, 2020).

13. Take the following examples: “the Houthis promote a neo-Zaydi ideology that is mostly obscure,” from al-Hamdani and Lackner, Talking to the Houthis; “the current conflict was not motivated by religion,” from Kendall, Iran’s Fingerprints in Yemen; and “Iran’s relationship with the Houthi movement in Yemen is weaker from a Shia ideological perspective,” from Springborg, Williams, and Zavage, “Iranian Security Assistance.”

14. Uzi Rubin, Iran’s Missiles and Its Evolving “Rings of Fire” (Ramat Gan, Israel: Begin-Sadat Center for Strategic Studies, 2020).

15. Jude Kadri, “The Collapse of Yemen’s Sovereignty by Permanent Violence: A Means of Both Production and Consumption of Value,” Arab Studies Quarterly 43, no. 2 (2021), https://doi.org/10.13169/arabstudquar.43.2.0098.

16. Kendall, Iran’s Fingerprints in Yemen.

17. Thomas Juneau, “How War in Yemen Transformed the Iran-Houthi Partnership,” Studies in Conflict and Terrorism 47, no. 3 (2021): 1–23, https://doi.org/10.1080/1057610x.2021.1954353.

18. Ahmed Nagi, “Yemen’s Houthis Used Multiple Identities to Advance,” Carnegie Middle East Center, 19 March 2019.

19. Yemen 2022 International Religious Freedom Report (Washington, DC: Department of State, 2022).

20. Mohammed Abdulla Mohammed, “The Houthi Movement from a Local Perspective: A Resurgence of Political Zaidism,” Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies, 4 January 2021; Ekaterina Pukhovaia, “Early Modern State Development in Yemen,” Leiden Islam Blog, 3 February 2023; and Bruce Riedel, “The Houthis Have Won in Yemen: What Next?,” Brookings, 1 February 2022.

21. Riedel, “The Houthis Have Won in Yemen: What Next?”

22. Christopher Harnisch and Katherine Zimmerman, “Profile: Al Houthi Movement,” AEI, 28 January 2010.

23. Marcus Montgomery, “A Timeline of the Yemen Crisis, from the 1990s to the Present,” Arab Center Washington DC, 8 April 2024.

24. Michael Knights, “The Houthi War Machine: From Guerrilla War to State Capture,” CTC Sentinel 11, no. 8 (September 2018).

25. Yemen 2022 International Religious Freedom Report.

26. Mohammad Abdul Salam (@Abdusalamsalah), X, 5 November 2023.

27. Examples include the following articles: “Al-Aqsa Storm Exposes US Audacity, Arab Regimes’ Submissiveness,” Al-Masirah, accessed 7 August 2024; “Downing US MQ-9 Drone in Yemeni Waters Represents Sovereignty, Full Readiness,” Al-Masirah, accessed 7 August 2024; “Palestinian, Arab Politicians to Almasirah: US-UK Aggression Won’t Deter Yemen From Supporting Palestine,” Al-Masirah, 30 January 2024; and “Martyr Leader Sayyed Hussein Al-Houthi Established Practical Approach to Support Palestinians,” Al-Masirah, 17 February 2024.

28. “Arab Public Opinion About Israel’s War on Gaza,” Arab Center Washington DC, 8 February 2024.

29. “Arab Public Opinion About Israel’s War on Gaza.”

30. “ ‘Until Israel Stops!’: Yemenis Rally for Houthis, Palestinians in Sanaa,” Al Jazeera, 19 January 2024.

31. Refer to the following examples of educational material compiled by Itam Shalev: #13, #14, #15. Shalev and Pardo, Review of Houthi Educational Materials in Yemen 2015–19.

32. Mohammad Abdul Salam (@Abdusalamsalah), X, 4 January 2024. Additionally, refer to the following examples of educational material compiled by Itam Shalev: #15. Shalev and Pardo, Review of Houthi Educational Materials in Yemen 2015–19.

33. Refer to the following examples of educational material compiled by Itam Shalev: #7, #8. Shalev and Pardo Review of Houthi Educational Materials in Yemen 2015–19; and Mohammad Abdul Salam (@Abdusalamsalah), X, 13 October 2023.

34. Adam Taylor, “The History of ‘Death to America’,” Washington Post, 1 December 2021.

35. Ahmed Nagi, “The Pitfalls of Saudi Arabia’s Security-Centric Strategy in Yemen,” Carnegie Middle East Center, 12 October 2022.

36. “USA and France Dramatically Increase Major Arms Exports; Saudi Arabia Is Largest Arms Importer, Says SIPRI,” SIPRI, 9 March 2020; Forensic Architecture et al., “European Arms in the Bombing of Yemen,” Yemen.forensic-architecture.org, accessed 8 August 2024; and Steven A. Cook, “America Is Not an Innocent Bystander in Yemen,” Council on Foreign Relations, 3 October 2018.

37. Policy Planning White Paper: Governance Under Ansar Allah (Sana’a, Yemen: Resonate! Yemen, 2022).

38. Refer to the following examples of educational material compiled by Itam Shalev: #2, #3, #4. Shalev and Pardo, Review of Houthi Educational Materials in Yemen 2015–19.

39. Refer to the following examples of educational material compiled by Itam Shalev: #1, #22, #25. Shalev and Pardo, Review of Houthi Educational Materials in Yemen 2015–19.

40. Refer to the following examples of educational material compiled by Itam Shalev: #9, #19, #20, #22, #25. Shalev and Pardo, Review of Houthi Educational Materials in Yemen 2015–19.

41. Parisa Kamali et al., “Red Sea Attacks Disrupt Global Trade,” IMF, 7 March 2024.

42. “Reuters Report Exposes US Lies of Sana’a’s Threats to International Navigation in Red Sea,” Al-Masirah, 9 February 2024; and the following three X posts from Mohammad Abdul Salam (@Abdusalamsalah): 19 January 2024; and 15 January 2024.

43. “Houthi Attack Kills Three Sailors in Group’s First Fatal Strike on Shipping,” Al Jazeera, 7 March 2024; Jon Gambrell, “Houthi Rebel Attack Sets Cargo Ship Ablaze, Forces Israel to Intercept Another Attack Near Eilat,” AP News, 22 February 2024; and Heather Mongilio, “Chinese Tanker Hit with Houthi Missile in the Red Sea,” USNI News, 24 March 2024.

44. Houthi Attacks in the Red Sea: Issues for Congress (Washington, DC: Congressional Research Service, 2024).

45. “US Denies Yemen’s Houthis Claim of Attack on US Military Cargo Ship in Gulf of Aden,” Reuters, 22 January 2024.

46. Denis Leven, “Russia and China Strike Deal with Houthis to Ensure Ship Safety: Bloomberg,” Politico, 21 March 2024; and Sam Dagher and Mohammed Hatem, “Yemen’s Houthis Tell China, Russia Their Ships Won’t Be Targeted,” Bloomberg, 21 March 2024.

47. Mongilio, “Chinese Tanker Hit with Houthi Missile in the Red Sea.”

48. Agnes Helou, “Purported Houthi Strike on Chinese Vessel in Red Sea Likely a ‘Mistake’: Experts,” Breaking Defense, 25 March 2024.

49. Justin Salhani, “Houthis Are Recruiting Record Fighters. How Will This Affect Yemen?,” Al Jazeera, 23 February 2024.

50. “Evolution of UAVs Employed by Houthi Forces in Yemen,” Conflict Armament Research and ArcGIS StoryMaps, 25 March 2024.

51. Seth G. Jones et al., The Iranian and Houthi War Against Saudi Arabia (Washington, DC: Center for Strategic and International Studies, 2022).

52. Iran: Enabling Houthi Attacks Across the Middle East (Washington, DC: Defense Intelligence Agency, 2024).

53. Iran: Enabling Houthi Attacks Across the Middle East.

54. “Houthis Say They Fired Ballistic Missiles at Israel’s Eilat,” Reuters, 2 February 2024.

55. Jonathan Saul, “Three Killed in First Fatal Houthi Attack on Red Sea Shipping, CENTCOM Says,” Reuters, 6 March 2024.

56. “Evolution of UAVs Employed by Houthi Forces in Yemen.”

57. Dhia Muhsin, “Houthi Use of Drones Delivers Potent Message in Yemen War,” International Center for Strategic Study, 27 August 2019.

58. Fabian Hinz, “Houthi Anti-Ship Missile Systems: Getting Better All the Time,” International Institute for Strategic Studies, 8 January 2024.

59. Iran: Enabling Houthi Attacks Across the Middle East.

60. Mohammad Abdul Salam (@Abdusalamsalah), X, 17 January 2024. Additionally, “Yemen’s Solidarity with Palestine Makes It a Key Player in Axis of Resistance,” Al-Masirah, 24 December 2023.

61. “Yemen’s Houthis Say Iranian Attack on Israel Is Legitimate,” Reuters, 14 April 2024.

62. Israel Ministry of Foreign Affairs, “Large-scale Iranian attack against Israel,” press release, 14 April 2024.

63. The following three X posts from Mohammad Abdul Salam (@Abdusalamsalah): 10 October 2023; 11 October 2023; and 17 October 2023. See also the following articles: “Palestinian Resistance Prevails in Gaza as Israel and US Run Out of Options,” Al-Masirah, 15 February 2024; “Haifa Missile Strike by Iraqi Resistance Shows How Fragile Israeli Regime Is,” Al-Masirah, accessed 8 August 2024; and “Yemen’s Solidarity with Palestine Makes It a Key Player in Axis of Resistance,” Al-Masirah, 24 December 2023.

64. Ali Parchami, “An Iranian Worldview,” in Routledge Handbook of Strategic Culture, 341–54, https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003010302-27.

65. Mohammed Ghobari, “Yemen’s Warring Parties Commit to Ceasefire Steps, U.N. Special Envoy Says,” Reuters, 23 December 2023.

66. “War in Yemen,” Council on Foreign Relations, 5 March 2024.

67. Ahmed Nagi, “Catching Up on the Back-Channel Peace Talks in Yemen,” 10 October 2023.

68. Nagi, “Catching Up on the Back-Channel Peace Talks in Yemen.”

69. Lolita C. Baldor, “Houthis May Be Running Low on Their Weapons Stocks as Attacks on Ships Slow, US Commander Says,” AP News, 3 April 2024.

70. Muhammad Al Gebaly, Hatem Maher, and Tala Ramadan, “Yemen’s Houthis Say They Targeted Western Ships,” Reuters, 7 April 2024.

71. “Houthi Red Sea Attacks Have Global Economic Repercussions,” Arab Center Washington DC, 5 April 2024; Houthi Attacks in the Red Sea: Issues for Congress; and Jim Garamone, “U.S., U.K. Launch Strikes Against Houthi Targets in Yemen to Protect R,” DOD News, 4 February 2024.

72. “Houthi Red Sea Attacks Have Global Economic Repercussions.”

73. Mohammad Abdul Salam (@Abdusalamsalah), X, 5 November 2023. Additionally, refer to the following examples of educational material compiled by Itam Shalev: #16, #17, #18, #19. Shalev and Pardo, Review of Houthi Educational Materials in Yemen 2015–19.

74. Salhani, “Houthis Are Recruiting Record Fighters.”

75. Aadil Brar, “Houthis Attack Chinese Ship Despite Deal Not To,” Newsweek, 25 March 2024.

76. Mohammad Abdul Salam (@Abdusalamsalah), X, 19 January 2024.