China’s Campaign to Undermine American Military Plans in the Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands

Evan N. Polisar

https://doi.org/10.21140/mcuj.2020110102

PRINTER FRIENDLY PDF

EPUB

AUDIOBOOK

Abstract: The Department of Defense (DOD) has proposed establishing several live-fire training areas in the Commonwealth of the Mariana Islands (CNMI) to address dozens of training deficiencies impacting Pacific forces. Capitalizing on local resistance to the proposal, the People’s Republic of China has waged a campaign of political and economic warfare in the CNMI through proxy casino companies to inflame opposition among residents and assert greater influence in the region. This article examines the DOD’s joint training proposal, China’s political and military efforts to undermine it, and important considerations should the plan move forward.

Keywords: China, Indo-Pacific, political warfare, military training, Mariana Islands

Introduction

The Indo-Pacific region is undergoing a period of profound change that will have considerable implications for the national security of the United States. Already home to more than one-half of the global population and many of the world’s busiest maritime trading routes, the Indo-Pacific has been identified by the Department of Defense (DOD) as the “single most consequential region” for American competitiveness and prosperity in the future.1 Recent presidential administrations have sought to increase the role of the United States in shaping the region through strategies such as the Pivot to Asia and the Free and Open Indo-Pacific, while simultaneously pursuing the ongoing realignment of the American military presence on Okinawa to address long-standing grievances held by the government of Japan.2

Against this backdrop, the DOD has pursued new joint military training capabilities in the Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands (CNMI) to address 42 training deficiencies identified in a 2013 study of the United States Indo-Pacific Command.3 One of four independent regions (or “hubs”) within the geographic area of responsibility with a concentration of units that meet or exceed the size of a squadron or battalion, the CNMI is expected to play an important role in maintaining American combat readiness in the Western Pacific following the repositioning of thousands of Marines from Japan to Guam, Hawaii, the western United States, and the rotational force in Darwin, Australia.4 The DOD has identified the CNMI islands of Tinian and Pagan as the “only suitable locations for development of RTAs for unit level and combined level training” capable of addressing these deficiencies. The DOD’s Combined Joint Military Training (CJMT) proposal seeks to establish large-scale, live-fire ranges and training areas (RTAs) on the two-thirds of Tinian already leased by the U.S. government and the entirety of Pagan.5 The RTAs would be used to address deficiencies in areas such as tactical amphibious operations, close air support, convoy operations, small arms proficiencies, naval gunfire support, and more to meet Title 10 U.S. Code (U.S.C.) requirements for organizing, training, and equipping forces.6

Though considered to be an important element of future basing and training options in the Western Pacific, the CJMT proposal has stalled for several years amid bureaucratic delays and local opposition. Amid this uncertainty, the People’s Republic of China (PRC) seized an opportunity to promote its strategic interests and assert greater influence in the region by fueling resentment to the proposal through a proxy campaign of political and economic warfare.7 As part of a “ ‘blocking operation’ designed to degrade the readiness of frontline U.S. Navy and Marine Corps (USMC) forces assigned or transiting [in the CNMI],” casino developers with close links to the PRC have promised multi-billion-dollar investments on several islands—an economic lifeline for the territory that has a per capita income of roughly $17,600 and poverty levels exceeding 55 percent.8 These developers have vocally opposed U.S. military activities in the CNMI and suggested that they would take their business elsewhere should the proposal move forward.9 Lieutenant General Wallace C. Gregson Jr. (Ret), former commander of Marine Forces, Pacific, describes what is happening in the CNMI as part of a larger, targeted information operation seeking to “control [American] access and limit our military presence” throughout the entire region.10

As the PRC continues to assert power in the Western Pacific through coercive economic and political policies—backed by a sweeping military modernization program designed to apply pressure on nations in the region and beyond with the ultimate goal of dislocating the United States—the CJMT proposal is increasingly caught in the cross fire of U.S.-China power competition.11 The DOD and senior military leaders continue to advocate for the CJMT proposal, including it in several guiding strategic documents (as recently as the June 2019 Indo-Pacific Strategy Report) and recent testimony before the Senate Armed Services Committee, and may soon face the difficult decision of whether to move the project forward over the objections of CNMI residents.12

This article argues that any action taken by the DOD, regardless of Chinese political interference, must be cognizant of the views of CNMI residents. While the PRC’s political operations are to a degree responsible for opposition to the CJMT proposal, long-standing preconceptions of distrust of the U.S. military resulting from decades of broken promises and neglect stand to be exacerbated by the establishment of new live-fire RTAs. The CNMI recently established a Second Marianas Political Status Commission for the purpose of reassessing its political status with the United States and exploring options for asserting independence—an endeavor that is increasingly influenced by negative attitudes toward the CJMT—underscoring the potential long-term ramifications of moving the proposal forward in bad faith.13

This article first examines the origins of the CJMT and discusses the PRC’s efforts to assert influence in the Western Pacific through political warfare and a sweeping military modernization program. After moving to a discussion of the questions surrounding the relevancy of the CJMT within the context of the changing security environment, this article concludes by outlining three considerations that should be addressed by the DOD prior to moving the proposal forward.

The Origin of the Combined Joint Military Training Proposal

Located to the north of Guam, the CNMI consists of 14 islands spanning more than 300 miles with a total land area of 183.5 square miles.14 After capturing the islands during World War II, American forces utilized Tinian as the point of departure for the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, Japan.15 Since then, the CNMI have continued to play an important role in U.S. strategic planning due to their location. Most recently, in May 2019, the DOD finalized a 40-year lease agreement to establish a United States Air Force divert airfield on Tinian, adding valuable operational capabilities for American forces during military exercises, humanitarian assistance and disaster-relief operations, or other emergencies as the U.S. military expands its footprint in the region.16

The CJMT grew out of a 2009 study completed by the Institute for Defense Analyses examining the state of individual Service component training capabilities in the Pacific. The study was the first to recognize the existence of unfulfilled training needs and identify the CNMI as a desirable location for future RTAs, noting its potential for supporting American forces reliant on foreign nations’ RTAs.17 The following year, the 2010 Quadrennial Defense Review Report validated the Institute for Defense Analyses study and formally recognized deficiencies in joint training in the Western Pacific. The U.S. Navy subsequently identified 62 specific training deficiencies affecting Pacific forces in 2012 and finalized a consolidated list of 42 needs in its 2013 Final Commonwealth of the Northern Marianna Islands Joint Military Training Requirements and Siting Study.18 The study made initial recommendations for where to establish new RTAs in the CNMI, paving the way for the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) process to begin. Under NEPA, which requires federal agencies to examine the potential effects of proposed actions that could cause significant harm to the environment, the DOD initiated an environmental impact study of the CJMT proposal in 2013.19 The Draft Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands Joint Military Training Environmental Impact Statement/Overseas Environmental Impact Statement (DEIS/OEIS), released in 2015, determined that the CJMT would have significant impacts on farmland, historic and cultural areas, public recreation, native wildlife and marine habitat, special-status species (including endangered coral), and other areas.20 The DEIS/OEIS suggested several mitigation measures to offset these effects but acknowledged that both Tinian and Pagan would incur unavoidable adverse effects.21 The document further noted the potential need for increasing training volume beyond the maximum capacity identified for each island, from 20 weeks on Tinian and 16 weeks on Pagan, up to 45 weeks and 40 weeks, respectively, which would require additional compliance under NEPA.22

After receiving strong opposition from CNMI residents amid concerns that the proposal would cause irreparable damage to the islands and those who live there, the DOD announced in February 2016 that it would publish a supplemental draft impact statement with “additional studies on the proposal’s impacts to coral, potable water, local transportation, and socioeconomic effects on surrounding communities.”23 The revision was expected to be finalized in March 2017, but has yet to be released at the time of this writing. Once finalized, the Office of the Assistant Secretary of the Navy must adhere to a mandatory 30-day waiting period before deciding whether to allow the proposal to move forward.24

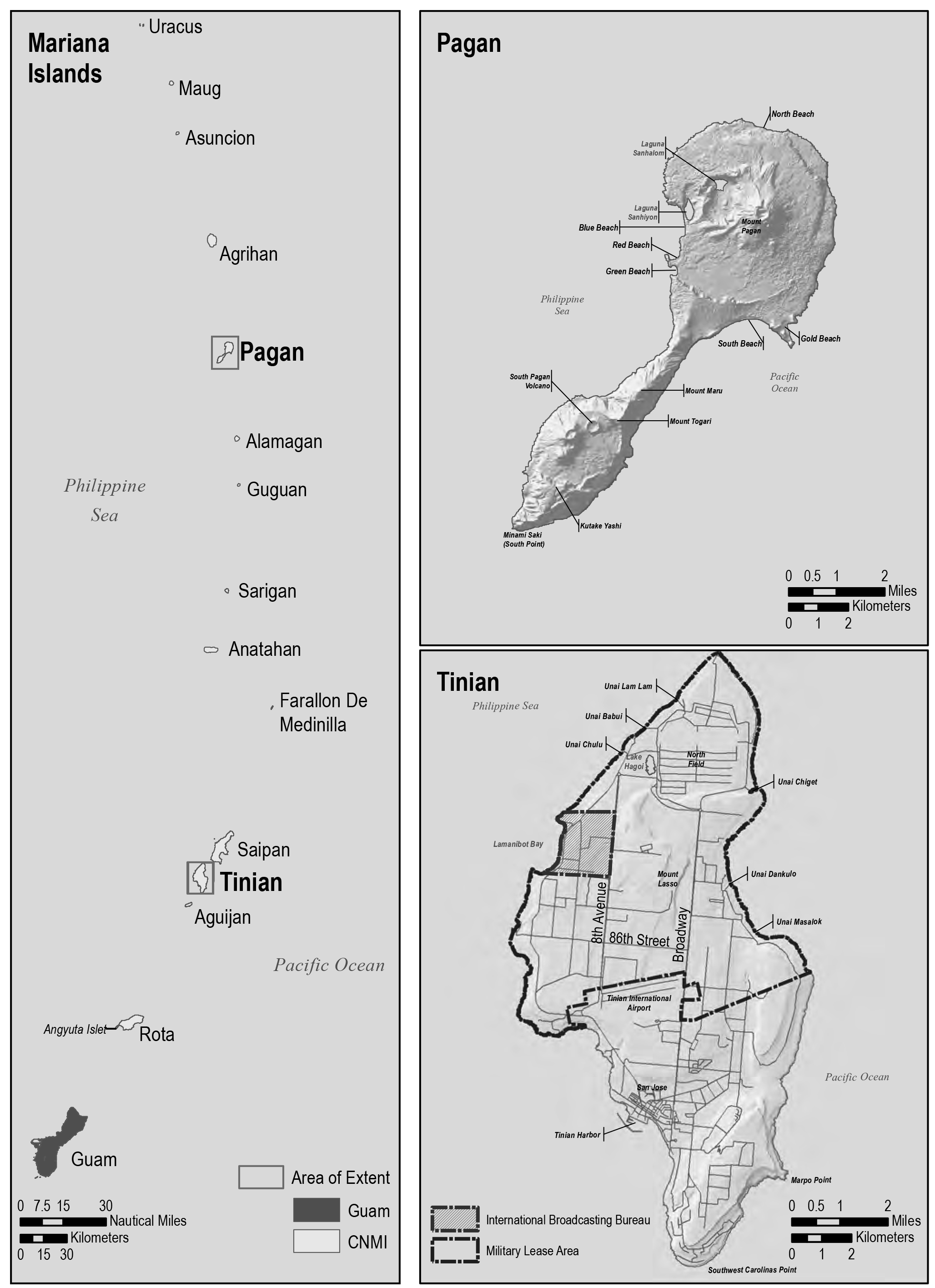

Map 1. Map of CNMI and CJMT project area

Source: Draft Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands Joint Military Training Environmental Impact Statement/Overseas Environmental Impact Statement (Washington, DC: Department of Defense, 2015).

Casinos as a Weapon of War

As the U.S. military continues to pursue the CJMT, the Chinese government has increasingly turned to political and economic warfare as an innovative means of expanding its reach without risking military conflict. Investors with ties to the Chinese government have set their eyes on the CNMI, pledging billions in economic development to assert influence on the island’s residents and economy. The United States-China Economic and Security Review Commission cites the “rapid growth in Chinese investment and [the] influx of Chinese tourists” as fueling opposition to the DOD’s plans, while a recent report from the Center for Strategic and Budgetary Assessments emphasizes the “strategic benefit [for the PRC] of handcuffing the U.S. military on Pagan, interfering with it elsewhere in CNMI, and creating a politically influential Chinese presence in an American territory.”25 Indeed, significant investments in casinos and resorts, including two on the island of Tinian (one of which would border land leased by the DOD intended for the CJMT) have caused trepidation among residents, who fear that the United States’ military presence could jeopardize Chinese investments. Representatives from Alter City Group, one of several Chinese developers invested in the islands, have fueled the narrative that American military strategies are not in the best interests of CNMI residents, stating that “the [U.S. military] has suggested activities which adversely impact the island of Tinian, its residents and adjacent operators like [Alter City Group]. The benefits from the military with the [proposal] are minimal, but the burdens are significant and unsustainable.”26 Press releases issued by casino developers such as Imperial Pacific Holdings Limited have been published verbatim on the online newspaper Saipan Tribune, with headlines such as “Imperial Pacific: Bringing in More Jobs” and “Imperial Pacific=Economic Miracle.”27

The PRC’s pattern of coercive economic practices (often referred to as debt-trap diplomacy) has already allowed it to extend its political and military influence well beyond the CNMI and throughout the Indo-Pacific region. One of the most well-known examples of this practice is the case of Sri Lanka’s Magampura Mahinda Rajapaksa Port in the city of Hambantota. After unsuccessfully attempting to solicit $300 million in capital investment for the port in the early 2000s, Sri Lanka turned to the PRC to fund the project. From 2009 to 2014, unable to make the port commercially viable, Sri Lanka borrowed an additional $1.9 billion from the PRC. By 2017, Sri Lanka owed the PRC more than $8 billion. To relieve itself of the debt burden, the government eventually signed over the port to China on a 99-year lease, raising concerns that the facility could one day become a Chinese naval hub at the edge of the Indian Ocean.28

Figure 1. The Imperial Pacific Resort Hotel (pictured under construction) is part of a $7 billion resort and casino development with ties to the PRC on the CNMI island of Saipan

Source: Reprinted with permission by Jon Perez.

The PRC established a similar foothold in the Maldives following the 2013 election of Abdulla Yameen Abdul Gayoom, a pro-Beijing president who has since promoted exclusive trade agreements with the PRC and facilitated other forms of access likely to lead to increased Chinese naval operations in the region.29 The PRC has also financed a new wharf on the island of Espiritu Santo in Vanuatu, developing it into one of the largest in the region while making significant investments in the nation’s airport, sports stadiums, convention centers, roads, and office buildings—including governmental buildings used by the prime minister and Vanuatu’s foreign ministry staff.30 In May 2019, Vanuatu’s prime minister Charlot Salwaia announced that he would seek additional funding from the PRC through the One Belt, One Road initiative, stating that “we can’t wait for grants to come,” to address needs such as roads, ports, telecommunications, utilities, health care, and education.31 In total, the PRC has increased its foreign direct investments in Pacific Island countries 173 percent between 2014 and 2016 to nearly $3 billion to improve its strategic foothold.32 Over time, Indo-Pacific governments have developed a clearer understanding of China’s political and economic warfare strategies, resulting in a “significant stiffening of resistance” to Chinese influence operations among sovereign nations. China, however, maintains momentum and continues to assert its influence throughout the region.33

The PRC has recently turned its attention toward states aligned with the United States through Compacts of Free Association (COFA), including Palau, the Federated States of Micronesia (FSM), and the Marshall Islands.34 As the agreements approach expiration in 2023 and 2024, the PRC seeks to undermine the relationship between the United States and its COFA partners. The PRC’s influence operations in the FSM have been “systemic,” intertwining Chinese interests into the FSM’s political and commercial spheres through “grants, loans, donations, gifts, scholarships, educational opportunities, and China-sponsored regional forums offering investment and aid,” and routinely hosting high-level FSM delegations.35 China’s efforts to promote these contributions have allowed it to receive “outsized credit” for its investments in the FSM, while longstanding and significantly larger economic partnerships between the FSM and the United States are “taken for granted.”36 The FSM legislature’s consideration of a 2015 resolution proposing to terminate the nation’s compact agreement with the United States—irrespective of the proposal’s failure—illustrates the potential impacts of such influence operations. This has not gone unnoticed in the United States, leading lawmakers to include provisions in the conference report accompanying the National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2020 calling for expeditious negotiations for the agreement’s renewal, and the Donald J. Trump administration signaling that it will prioritize renegotiating the agreements.37

Beyond Casinos: Enduring Resentment Toward the American Military in the Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands

As the power struggle with the PRC continues to play out in the CNMI, a series of early missteps in the CJMT process, combined with the United States’ poor history of environmental stewardship in the region and across the globe, has cast a shadow over the legitimacy of the military and amplified the concerns of those opposed to the proposal. These underlying and enduring feelings are likely responsible, to a degree, for increasing the region’s vulnerability to Chinese influence operations. Indeed, CNMI residents have expressed their concerns that the DOD’s interests will eventually supersede their own, paving the way for the U.S. Navy and Marine Corps to proceed regardless of the wishes of the community.38 The CNMI’s previous governor, Eloy S. Inos, went so far as to call the CJMT an “existential threat” to the islands’ tourism-driven economy, fragile ecosystem, cultural resources, and way of life.39 The CNMI’s current governor, Ralph D. L. G. Torres, has described the process in which the proposal was pursued as “a slap in our face.”40

Figure 2. A Japanese shrine at Bandera Point, on the island of Pagan, sits in an area designated as Green Beach, one of several beaches sought by the DOD for live-fire amphibious assault training

Source: Reprinted with permission from Dan Lin.

A network of activists opposed to the proposal on environmental grounds have organized to stop the CJMT. Rosemond Santos, a founding member of the Guardians of Gani’—one of several groups to sue the DOD over the CJMT proposal—describes her connection with the island of Pagan concisely: “God lives there,” and when she visits the island, she can “sense the presence of [her] ancestors.”41 Santos recalls a hearing on the island of Tinian following the release of the DEIS/OEIS when residents expressed concern about the plan and an important fishing area that would be impacted by live-fire training. The representative of the military suggested that the DOD would “move the fish” to solve the problem.42 Governor Torres describes the DOD’s initial approach to the CJMT as having “started with people who were arrogant and disrespectful.” During his first meeting with representatives of the U.S. Navy, then-CNMI Senate President Torres inquired what recourse was available to the commonwealth’s government. He was told “there’s not much the government can do, at the end of the day, whether you like it or not, [the DOD] can take [the islands] through eminent domain.”43

Many in the CNMI believe the islands have already given enough to the DOD, which currently leases the entirety of the island of Farallon de Medinilla on a $20,600, 50-year lease, and most of the island of Tinian on a similar $17.5 million lease.44 The DOD recently received permission to triple the number of explosives dropped on Farallon de Medinilla annually and doubled the area around the CNMI where the U.S. Navy conducts undersea sonar and explosive training, despite significant opposition from the community.45 For some, these are just recent examples of the larger trend of broken promises and indifference to the people on the islands. David Mendiola Cing, a resident and former senator of the CNMI, remembers when the land leases were first being debated, recalling that residents were desperate from poverty and desired a military-based economy like the one on Guam. However, “in the 2010 census, every resident fell below the poverty line, and the median household income was $24,470, [and he says] Tinian was ‘the sacrificial lamb for the Commonwealth, for all of us to become U.S. citizens’.”46 The land lease, which was agreed to in the 1970s, described the services that would be made available to CNMI residents, including emergency care in military facilities, augmented firefighting capabilities, access to an on-base movie theater, federal assistance for funding for the local school system, jobs, and other economic activities.47 Rather than constructing an installation capable of providing these services, the land was used for cattle grazing, leaving residents feeling cheated.48

For other CNMI residents opposed to the CJMT, the American military’s legacy of poor environmental stewardship has led them to question the safety of the proposal. On the island of Saipan, the Tanapag Fuel Farm stands as a vestige of past American military presence. Abandoned by the Navy more than 50 years ago, the facility contains 42 above-ground fuel tanks that have, over time, corroded and collapsed, leaking their toxic contents into the ground.49 In 2006, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, the CNMI Division of Environmental Quality, and the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers removed more than a dozen of the tanks, disposing more than 1,000 tons of oil-contaminated soil and 140 tons of scrap metal in the process.50 In nearby Guam, a Superfund cleanup has been ongoing since 1993 to address contaminated groundwater in the region’s sole-source aquifer at Andersen Air Force Base.51 On Kaho’olawe Island, Hawaii, where the U.S. Navy conducted live-fire target practice for nearly 50 years, more than $400 million was needed to clear 85 percent of the island of nearly 30,000 munitions during a seven year period.52 After Hawaii’s legislature urged the Navy to finish the job, a Navy spokesperson explained that “no one familiar with Kaho’olawe or the clearance project ever promised or expected to clean up all of the [ordnance].”53 And, in Vieques, Puerto Rico, where the U.S. Navy conducted amphibious training and high-impact exercises nearly 180 days out of the year until 1999, including four months of integrated live-fire exercises by carrier groups and amphibious ready groups, thousands of acres of land have been left contaminated with mercury, depleted uranium, and Agent Orange, with an estimated cleanup cost exceeding $130 million.54

These considerations are significant when viewed through the lens of the rapidly changing security environment in the Western Pacific. As the PRC continues to project power into the region, the situation in the CNMI stands out as an opportunity for exerting new pressure on the United States, facilitated to a degree by views of residents influenced by preconceived views toward the American military. Projections included in the DEIS/OEIS indicate that the number of tourists to the CNMI could increase “between 25 percent and 56 percent higher than 2012 levels” in large part due to those visiting from the PRC—economic growth that could be jeopardized by the implementation of the CJMT.55 The CNMI already draws its largest amount of revenue from hospitality, and residents increasingly worry that constant bombing and training on the islands will discourage tourism, jeopardize its visa waiver program with China, and impact daily life.56 In this way, the CJMT already presents a double-edged sword for CNMI residents, pitting American strategic interests at odds with the desires of many people in the community. As questions surrounding the proposal continue, the CNMI’s discontent with the United States over its treatment of the islands—contrasted with readily available, large-scale Chinese economic investments—continues to take on greater significance.

The Combined Joint Military Training Proposal: A Strategic Imperative?

The PRC’s far-reaching military modernization program complements its political and economic warfare campaigns. China’s military buildup is particularly noteworthy as it represents the most tangible front for exerting power and coercing sovereign states and territories throughout the Pacific. In the 10 years that have passed since the CJMT took shape, the Western Pacific has experienced significant changes in the strategic landscape as the PRC extends its territorial reach farther into international waters with new capabilities in the maritime, air, space, and cyber domains.57

The PRC’s modernization effort has yielded developments in submarines, surface craft, aircraft, unmanned vehicles, advanced missiles, and the requisite command and control, communications, computers, intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance systems.58 New aircraft have the ability to carry long-range and precision strike land-attack cruise missiles capable of reaching Guam and the CNMI, while new antiship ballistic missile capabilities give the PRC the ability to strike American aircraft carriers in the Western Pacific for the first time.59 Rear Admiral A. Eric McVadon (Ret) describes the PRC’s antiship ballistic missile capabilities as the “strategic equivalent of China’s acquiring nuclear weapons in 1964,” while other analysts have warned that the proliferation of such technology increases the risks of “miscalculation, deterrence failure, military escalation, inadvertent war, and an intractable security dilemma.”60 Already controlling the region’s largest naval force with more than 300 craft, the People’s Liberation Army Navy is expected to possess between 65 and 70 submarines in 2020, including several with submarine-launched ballistic missile capabilities considered to be China’s first credible sea-based nuclear deterrent.61

It is important to note that the PRC does not seek military conflict with the United States, and the likelihood of armed conflict between the two countries is widely considered to be unlikely.62 While the PRC prefers to achieve its military, economic, and diplomatic goals without jeopardizing regional stability, it nevertheless wants a military force capable of winning if a fight becomes necessary.63 The PRC’s military modernization effort should therefore be seen as a form of deterrence that complements its nonmilitary instruments of power as it continues to fortify its antiaccess/area-denial (A2/AD) shield and to extend its reach into the Western Pacific.

The United States will need to adapt to the paradigm of near-peer strategic competition as the PRC fields increasingly sophisticated military capabilities that can challenge American power. Given that the CJMT is predicated on enabling forward-based Pacific forces to meet their Title 10 requirements to organize, train, and equip, dramatic shifts in the operational environment should be important factors for determining if and how the plan will progress.64 While not directed at China specifically, the capabilities encapsulated within the CJMT are considered integral for the type of joint force operations that will likely characterize any future military operations. The DOD formulated the CJMT based on the determination that “existing U.S. military live-fire, unit and combined level training ranges, training areas, and support facilities are insufficient to support U.S. Pacific Command Service Components’ training requirements in the Western Pacific, specifically in the Mariana Islands.”65 The need for these capabilities is further described in the 2015 National Military Strategy, which specifically cites the CJMT proposal as critical for “[enhancing] the readiness of our forward forces to respond to regional crises . . . [and supporting] the arrival of next-generation capabilities and joint training and readiness.”66 The recently published 2019 Indo-Pacific Strategy Report similarly identifies the air, surface, and subsurface training capabilities encompassed by the CJMT as important for maintaining joint force readiness and increasing multilateral training opportunities amid the military buildup in Guam.67

Documents disseminated to the public following the release of the DEIS/OEIS explain that readiness training “must be as realistic and diverse as possible to provide the experiences necessary for the success,” citing the need for training to be realistic, integrated, adaptable, exclusive, continuous, uninterrupted, and supportive of alliances and partnerships.68 As the security environment continues to evolve, so too have American military concepts for conducting operations in environments contested by near-peer adversary forces. In keeping with then-Secretary of Defense James N. Mattis’s statement in the unclassified summary of the 2018 National Defense Strategy that the United States “cannot expect success fighting tomorrow’s conflicts with yesterday’s weapons or equipment,” the DOD is fielding new technologies as Service components issue new operating concepts addressing the emerging paradigm of near-peer competition.69 As an example, the most recently published Marine Corps Operating Concept is premised on the need to train, organize, and equip for future operational constraints, such as complex terrain, the proliferation of technology, and the increasingly nonpermissive A2/AD environment.70 The subordinate concept, littoral operations in a contested environment, provides an additional framework for the U.S. Navy and Marine Corps to fight in contested littoral areas without presumptive sea control, and describes how both will operate “from dispersed locations both ashore and afloat [to] achieve local sea control and power projection into contested littoral areas,” including “creating gaps/seams by location and/or time that can be exploited through a maneuver warfare approach.”71 The forthcoming expeditionary advanced base operations concept is expected to provide an approach for mobile, low-cost, distributed expeditionary operations in austere environments, including the ability to position coastal missile defenses and rearming and refueling points along key island chains.72

While these new operational concepts will require routine access to training—suggesting a greater need for new RTAs in the Western Pacific—such significant shifts in operational paradigms also emphasize the degree to which the PRC’s increasing naval, air, space, and cyber power have resulted in an operational environment that is vastly different from the one that existed when the CJMT was first proposed. When considering the proposal’s raison d’être of addressing joint training deficiencies throughout U.S. Indo-Pacific Command, it is possible that some of the capabilities driving the CJMT may no longer be essential—or even viable—for American power projection in the region. This consideration is illustrated by the Marine Corps’ recently published Force Design 2030, which calls for substantially altering how the force will prepare to meet the emerging operational environment in the Indo-Pacific. Citing the impacts of the proliferation of advanced long-range fires, mines, and other threats, Force Design 2030 outlines the Commandant’s intention to divest the Marine Corps from increasingly vulnerable systems, including eliminating the Service’s tank force, a significant number of cannon artillery battalions, several air combat elements and amphibious assault companies, and a total force reduction of approximately 12,000 Marines by the end of the decade.73

Notably, many of the force projection capabilities identified for divestment by Force Design 2030 are encapsulated within the CJMT. The list of unmet training needs outlined in the 2013 Joint Military Training Requirements and Siting Study included RTA requirements for field artillery, tank operations, and amphibious operations, including forced entry and maneuver operations. While some of these capabilities—amphibious capabilities, for example—will continue to be critical for U.S. power projection in the future (as reiterated by concepts such as littoral operations in a contested environment and expeditionary advanced base operations), it is nevertheless important to recognize that the way in which these operations are conducted must reflect changes in the strategic landscape. For instance, the United States has not staged a large-scale amphibious operation since the Korean War. And, according to Major General David W. Coffman, director of expeditionary warfare for the Chief of Naval Operations, the Marine Corps has too few ships to even conduct such an operation today without incurring an unacceptable number of casualties given the PRC’s increasingly sophisticated missile capabilities, growing military strength, and expanded A2/AD shield.74 The PRC’s continued militarization of the South China Sea, including the placement of antiship cruise missiles and long-range surface to air missiles in the Spratly Islands and recently conducted strategic bomber takeoff and landing drills on the disputed Woody Island (a.k.a. Yongxing Island by the PRC) further illustrates the speed with which the PRC has expanded its reach into the Western Pacific.75 Force Design 2030 reflects this reality, pairing divestments with increased investments in land-based rocket artillery, long-range precision antiship missile capabilities, unmanned aerial systems, and smaller, lower signature amphibious vehicles.76 Such significant operational constraints call into question the need to establish new RTAs for amphibious capabilities while others already exist throughout the area of operations. These concerns are further buoyed by findings from the 2013 Training Needs Assessment, which noted that just 2 of the 62 deficiencies initially identified were “not mission capable” across all four hubs—suggesting that some form of training capability already exists in the area of operation for virtually every training requirement identified as deficient.77

While changes in the operational environment suggest the DOD would benefit from refining the list of deficiencies sought to be addressed by the CJMT, it can also be argued that even a refined list of training capabilities would provide sufficient strategic benefits simply by making it easier for forces to remain operationally proficient. Bilateral and multilateral amphibious operations are central aspects of the littoral operations in a contested environment and expeditionary advanced base operations concepts and will continue to serve important purposes across the spectrum of military operations. As these concepts illustrate, future operations are likely to continue to increase in complexity and will require access to geographically dispersed training areas. Further, as noted by senior military leaders, having RTAs sovereign to the United States may also be of enough strategic benefit to warrant the proposal. For instance, the 2009 Institute for Defense Analyses study noted that the CNMI were particularly important to U.S. forces located on the Western Pacific rim given their reliance on foreign nations’ RTAs and long transit time to American soil.78 During a prior military buildup on Andersen Air Force Base in Guam, Air Force major general Dennis R. Larsen explained the strategic benefits of placing RTAs within American territories, saying that “this is not Okinawa. . . .This is American soil in the midst of the Pacific. . . . We can do what we want here and make huge investments without fear of being thrown out.”79 While this perspective offers another insight into the impetus for the CJMT, guiding national strategic documents, including the National Military Strategy and the Asia-Pacific Maritime Security Strategy, laud the United States’ role in the region and infer that other nations are increasingly looking to the American military to promote stability.80 This suggests that there is increased interest in partnering with American forces, rather than growing risk of being denied access to areas of strategic importance.

Considerations

Following years of delays and uncertainty, the CJMT proposal may soon move forward following the release of the revised EIS/OEIS. The proposal, however, does not exist in a vacuum. While Service components are required to meet specific responsibilities under Title 10, technological advancements on the part of the PRC have already required the United States military to adapt with new operating concepts emphasizing maneuverability, resiliency, and distribution. Amid challenges posed by near-peer military threats and ongoing economic and political warfare campaigns, it is necessary to take steps to ensure that the CJMT is still in the best interest of U.S. national security and that it is carried out appropriately. To satisfy these considerations, the DOD should do three things before moving forward with the proposal.

First, the DOD should revisit the conclusions of the 2009 Institute for Defense Analyses study and 2013 Joint Military Training Requirements and Siting Study to determine the extent to which the joint training deficiencies driving the CJMT proposal are relevant to the current and future operational environment. The PRC’s development of cutting-edge technologies, emphasis on space and cyber domain warfare, and proliferation of new, modernized naval craft and aircraft will continue to reshape the balance of power in the region. Furthermore, its antiship cruise missile program, expanding air defense architecture, and rapidly improving offensive capabilities will increasingly call into question conventional American deterrence strategies that have been effective throughout the past several decades. Force Design 2030 serves as an example of how the shifting landscape requires an evolution in how the Marine Corps trains, organizes, and equips its forces. Ensuring the CJMT is focused on specific enduring capabilities rather than overextending itself with unnecessary RTAs would save valuable resources and, perhaps more importantly, demonstrate the U.S. government’s desire to do only what is necessary to maintain its strategic foothold. This small step would be an important signal to CNMI residents that their land and concerns are not taken for granted.

Second, the DOD should clarify the strategic benefits of placing the CJMT in the CNMI region. Several documents supporting the CJMT specifically mention the need to construct RTAs on American soil to decrease reliance on foreign RTAs. While the PRC’s coercive economic and diplomatic processes have brought a few nations further into its sphere of influence, the United States continues to maintain its alliances and develop new partnerships, conducting hundreds of exercises and military engagements with dozens of countries every year. This fact is not lost on CNMI residents. The DOD should therefore articulate which, if any, foreign RTAs it fears losing access to, what options exist for filling these potential gaps with preexisting RTAs within U.S. Indo-Pacific Command, and how it will work with other American government agencies to strengthen existing foreign RTA agreements. The DOD should clearly address why the deficiencies outlined in the Joint Military Training Requirements and Siting Study cannot be addressed elsewhere, either at foreign RTAs or those existing in Hawaii or the Western United States. As with the previous consideration, this small step would send an important signal to residents of the CNMI and more sufficiently communicate the DOD’s position on the long-term strategic necessity of the CJMT.

Finally, recognizing that moving forward with the CJMT will likely create new challenges for the U.S. government in the CNMI, the DOD must do more to address the concerns of the territory’s residents. As has been illustrated, opposition to the CJMT stems from several factors, including residents’ feelings of neglect and disrespect, the military’s perceived indifference toward the proposal’s impacts on their daily lives, as well as concerns stemming from the potential loss of billions in foreign investments. In this regard, it is important to acknowledge that the PRC’s economic and political operations in the territory only tell part of the story. The DOD’s legacy of broken promises has arguably influenced many in the region to distrust the military’s DEIS/OEIS findings, such as the determination that the CJMT would benefit the local economy despite failing to acknowledge the constraints the proposal would place on future economic growth and the potential loss of billions in outside investments. The DOD, and the entire U.S. government, must work with government of the CNMI to mitigate the impacts of these considerations and commit to new economic investments in the territory. These discussions should be conducted respectfully and transparently to emphasize the United States’ continued commitment to the CNMI and its people. Doing so may be the best option for moving the CJMT proposal forward in a manner that is acceptable to all parties.

Conclusion

The PRC’s continued political influence operations in the CNMI present a significant challenge for the DOD and the U.S. government. Chinese investments provide residents with sorely needed economic incentives and an alternative to constant live-fire training, despite being at odds with American strategic interests. Given the above scenario, this article argued that the U.S. government should unequivocally recommit itself to the CNMI, paying particularly close attention to the islands’ needs so as not to create additional opportunities for the PRC to exploit through political and economic influence operations. While the CJMT could strengthen the United States’ strategic posture in the CNMI region, if implemented in the face of overwhelming opposition, such an action would likely undermine the military’s position as a moral and ethical force and lead to new animosity among the local population. As the government of the CNMI considers exerting greater independence from the United States, the DOD must therefore make every possible effort to work with the local government to address the concerns of those whose lives will be changed by bombs, bullets, and wargames.

Endnotes

- The Department of Defense Indo-Pacific Strategy Report: Preparedness, Partnerships, and Promoting a Networked Region (Washington, DC: DOD, 2019), 1, hereafter Indo-Pacific Strategy Report.

- Emma Chanlett-Avery, Christopher T. Mann, and Joshua A. Williams, U.S. Military Presence on Okinawa and Realignment to Guam, In Focus series (Washington, DC: Congressional Research Service, 2019).

- Final Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands Joint Military Training Requirements and Siting Study (Honolulu, HI: Naval Facilities Engineering Command, Pacific, Department of the Navy, 2013), 3-1, hereafter Siting Study.

- Siting Study, 1-2; and Indo-Pacific Strategy Report, 23. The four hubs—Hawaii, Japan, Korea, and the Mariana Islands—are identified in Final Training Needs Assessment: An Assessment of Current Training Ranges and Supporting Facilities in the U.S. Pacific Command Area of Responsibility (Honolulu, HI: Naval Facilities Engineering Command, Pacific, Department of the Navy, 2013), ES-2.

- Draft Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands Joint Military Training Environmental Impact Statement/Overseas Environmental Impact Statement (Honolulu, HI: Naval Facilities Engineering Command, Pacific, Department of the Navy, 2015), ES-6, ES-40, 1-12.

- Goldwater-Nichols Department of Defense Reorganization Act of 1986, 10 U.S.C. §5062–3 (1986).

- Indo-Pacific Strategy Report, 23.

- James E. Fanell, “China’s Global Naval Strategy and Expanding Force Structure: Pathway to Hegemony,” Naval War College Review 72, no. 1 (Winter 2019): 41; “Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands,” Office of Insular Affairs, U.S. Department of the Interior, accessed 19 May 2020; and “HIES 2016 Population,” CNMI Department of Commerce, accessed 19 May 2020.

- Ross Babbage, Winning without Fighting: Chinese and Russian Political Warfare Campaigns and How the West Can Prevail, vol. II, Case Studies (Washington, DC: Center for Strategic and Budgetary Assessments, 2019), 19.

- Ethan Meick, Michelle Ker, and Han May Chan, China’s Engagement in the Pacific Islands: Implications for the United States (Washington, DC: U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission, 2018), 19.

- China Naval Modernization: Implications for U.S. Navy Capabilities—Background and Issues for Congress (Washington, DC: Congressional Research Service, 2018), 6. This report has since been updated in 2020.

- Indo-Pacific Strategy Report, 23; and Statement of Admiral Philip S. Davidson, U.S. Navy Commander of U.S. Indo-Pacific Command, before the Senate Armed Services Committee, 116th Cong. (12 February 2019).

- Anita Hofschneider, “More Political Power For The Marianas?,” Honolulu Civil Beat, 15 December 2016; Ross Babbage, Winning without Fighting: Chinese and Russian Political Warfare Campaigns and How the West Can Prevail, vol. I (Washington, DC: Center for Strategic and Budgetary Assessments, 2019), 18; and Emmanuel T. Erediano, “UN expert, Guam professor Meet with 2nd Marianas Political Status Commission,” Marianas Variety, 19 November 2019.

- “Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands.”

- Josette H. Williams, “The Information War in the Pacific, 1945: Paths to Peace,” Studies in Intelligence 46, no. 3 (2002).

- According to the DOD, the term divert airfield refers to an airfield with at least minimum essential facilities to serve as an emergency airfield or when the main or redeployment airfield is not usable or as required to accommodate tactical operations. Pacific Air Forces Public Affairs, “CNMI Signs $21.9M 40-year Lease with US DOD,” U.S. Air Force, 8 May 2019.

- Draft Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands Joint Military Training Environmental Impact Statement, ES-4; and Training Needs Assessment: An Assessment of Current Training Ranges and Supporting Facilities in the U.S. Pacific Command Area of Responsibility (Honolulu, HI: Department of the Navy, 2013), ES-1.

- Training Needs Assessment, ES-1; and Siting Study, 3-1.

- Draft Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands Joint Military Training Environmental Impact Statement, ES-1.

- Draft Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands Joint Military Training Environmental Impact Statement, 4-546–4-573.

- Draft Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands Joint Military Training Environmental Impact Statement, 6-3, 6-5.

- Draft Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands Joint Military Training Environmental Impact Statement, ES-14.

- “DOD to Issue Revised Draft EIS on CJMT,” CNMI Joint Military Training EIS/OEIS, 18 February 2016.

- Draft Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands Joint Military Training Environmental Impact Statement (DEIS)/Overseas Environmental Impact Statement (OEIS) (Washington, DC: DOD, 2015), 18, hereafter DEIS/OEIS.

- Meick, China’s Engagement in the Pacific Islands, 10; and Babbage, Winning without Fighting, vol. II, 20.

- Meick, China’s Engagement in the Pacific Islands, 11.

- “Imperial Pacific: Bringing in More Jobs,” press release, Saipan Tribune, 2 June 2017; and “Imperial Pacific=Economic Miracle,” press release, Saipan Tribune, 30 May 2017.

- Sam Parker and Gabrielle Chefitz, Debtbook Diplomacy: China’s Strategic Leveraging of its Newfound Economic Influence and the Consequences for U.S. Foreign Policy (Cambridge, MA: Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs, Harvard Kennedy School, Harvard University, 2018), 9.

- Abdul Gayoom would later lose his second bid at the presidency and be sentenced to prison for money laundering. Fanell, “China’s Global Naval Strategy and Expanding Force Structure,” 42.

- Fanell, “China’s Global Naval Strategy and Expanding Force Structure,” 40.

- Charlotte Greenfield, “Vanuatu to Seek More Belt and Road Assistance from Beijing: PM,” Reuters, 22 May 2019.

- Meick, China’s Engagement in the Pacific Islands, 10.

- Babbage, Winning without Fighting, vol. I, 47.

- Derek Grossman et al., America’s Pacific Island Allies: The Freely Associated States and Chinese Influence (Santa Monica, CA: Rand, 2019), https://doi.org/10.7249/RR2973.

- Babbage, Winning without Fighting, vol. II, 20.

- Babbage, Winning without Fighting, vol. II, 23.

- National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2020, Conference Report to Accompany S.1790, 116th Cong. (2019), 1413; and “Secretary Pompeo Tells President Panuelo: ‘We’re Ready to Start Negotiations on the Compact of Free Association’,” press release, Embassy of the Federated States of Micronesia in Washington, DC, 5 August 2019.

- Sophia Perez, “Despite Lawsuit Outcome, Governor Remains Opposed to CJMT,” Marianas Variety, 24 August 2018.

- Anita Hofschneider, “Can These Islands Survive America’s Military Pivot to Asia?,” Honolulu Civil Beat, 12 December 2016.

- Perez, “Despite Lawsuit Outcome, Governor Remains Opposed to CJMT.”

- Sophia Perez, “Despite Losing Lawsuit, Guardians of Gani’ Co-founder Continues Fight,” Marianas Variety, 31 August 2018.

- Perez, “Despite Losing Lawsuit, Guardians of Gani’ Co-founder Continues Fight.”

- Perez, “Despite Lawsuit Outcome, Governor remains Opposed to CJMT.”

- Anita Hofschneider, “FDM: This Island Has Been Military Target Practice for Decades,” Honolulu Civil Beat, 13 December 2016.

- Hofschneider, “FDM”; and Hofschneider, “Can These Islands Survive America’s Military Pivot to Asia?”

- Anita Hofschneider, “Tinian: ‘We Believed in America’,” Honolulu Civil Beat, 14 December 2016.

- Technical Agreement Regarding Use of Land to be Leased by the United States in the Northern Mariana Islands (15 February 1975), B-17–B19.

- Hofschneider, “FDM.”

- Hofschneider, “Can These Islands Survive America’s Military Pivot to Asia?”

- “Tanapag Fuel Farm Project,” Pollution Report (POLREP) #11, United States Environmental Protection Agency, 26 June 2006.

- “Superfund Site: Andersen Air Force Base, Yigo, GU,” United States Environmental Protection Agency, accessed 19 May 2020.

- Final Summary: After Action Report Kaho’olawe Island Reserve (Honolulu, HI: Naval Facilities Engineering Command Pacific Division, 2004), 10.

- Sophie Cocke, “State Senators: Sue Navy for $100 Million Over Kahoolawe Cleanup,” Honolulu Civil Beat, 28 August 2013.

- Ronald O’Rourke, Vieques, Puerto Rico Naval Training Range: Background and Issues for Congress (Washington, DC: Congressional Research Service, 2001), 2; and David Bearden, Vieques and Culebra Islands: An Analysis of Cleanup Status and Costs (Washington, DC: Congressional Research Service, 2005), 8.

- Draft Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands Joint Military Training Environmental Impact Statement, 3-252.

- Hofschneider, “Can These Islands Survive America’s Military Pivot to Asia?”

- Hearing to Consider the Nominations of: Admiral Phillip S. Davidson, U.S. Navy, for Reappointment to the Grade of Admiral and to Be Commander, United States Pacific Command; and General Terrence J. O’Shaughnessy, USAF, for Reappointment to the Grade of General and to Be the Command, United States Northern Command, and Commander, North American Aerospace Defense Command, 115th Cong. (17 April 2018) (statement of Adm Phillip S. Davidson, U.S. Navy).

- China Naval Modernization, 2.

- Annual Report to Congress: Military and Security Developments Involving the People’s Republic of China 2019 (Washington, DC: Office of the Secretary of Defense, 2019), 41, 44.

- James Samuel Johnson, “China’s ‘Guam Express’ and ‘Carrier Killers’: The Anti-ship Asymmetric Challenge to the U.S. in the Western Pacific,” Comparative Strategy 36, no. 4 (2017): 319, https://doi.org/10.1080/01495933.2017.1361204.

- Annual Report to Congress, 36.

- James Dobbins et al., Conflict with China Revisited: Prospects, Consequences, and Strategies for Deterrence (Santa Monica, CA: Rand, 2017), 2, https://doi.org/10.7249/PE248.

- Annual Report to Congress, 13.

- Draft Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands Joint Military Training Environmental Impact Statement, 1-8.

- Draft Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands Joint Military Training Environmental Impact Statement, 1-5.

- The National Military Strategy of the United States of America, 2015: The United States Military’s Contribution to National Security (Washington, DC, Joint Chiefs of Staff, 2015), 22–23.

- Indo-Pacific Strategy Report, 23.

- DEIS/OEIS, 2; and Draft Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands Joint Military Training Environmental Impact Statement, 1-5.

- James N. Mattis, Summary of the 2018 National Defense Strategy of the United States of America: Sharpening the American Military’s Competitive Edge (Washington, DC: DOD, 2018), 6.

- Marine Corps Operating Concept: How an Expeditionary Force Operates in the 21st Century (Washington. DC: Headquarters Marine Corps, 2016), 8.

- Marine Corps Operating Concept, 12.

- “Expeditionary Advanced Base Operations (EABO),” Concepts and Programs, United States Marine Corps, accessed 25 June 2019.

- David H. Berger, Force Design 2030 (Washington, DC: Headquarters Marine Corps, 2020), 2–7.

- Todd South, “Set Up to Fail?: Marines Don’t Have Enough Ships to Train for a Real Amphibious Assault,” Marine Corps Times, 8 January 2018.

- Annual Report to Congress, 73.

- Force Design 2030, 2–8.

- Training Needs Assessment, ES-8.

- Training Needs Assessment, ES-1.

- Robert D. Kaplan, Hog Pilots, Blue Water Grunts: The American Military in the Air, at Sea, and on the Ground (New York: Random House, 2007), 60–61.

- National Military Strategy, 9; and Asia-Pacific Maritime Security Strategy (Washington, DC: DOD, 2015), 24.