The People’s Republic of China’s Strategy “to Win without Fighting”1

Professor Kerry K. Gershaneck

https://doi.org/10.21140/mcuj.2020110103

PRINTER FRIENDLY PDF

EPUB

AUDIOBOOK

Abstract: The Commandant of the Marine Corps has identified the People’s Republic of China (PRC) as an existential threat to the United States in the long term. To successfully confront this threat, the United States must relearn how to fight on the political warfare battlefield. Although increasingly capable militarily, the PRC employs political warfare as its primary weapon to destroy its adversaries. However, America no longer has the capacity to compete and win on the political warfare battlefield: this capacity atrophied in the nearly three decades following the collapse of the Soviet Union. Failure to understand China’s political warfare and how to fight it may well lead to America’s strategic defeat before initiation of armed conflict and to operational defeat of U.S. military forces on the battlefield. The study concludes with recommendations the U.S. government must take to successfully counter this existential threat.

Keywords: People’s Republic of China, PRC, political warfare, United Front Work Department, propaganda, China Dream, Great Rejuvenation, Xi Jinping, people’s war, three warfares, strategic psychological warfare, People’s Liberation Army, PLA, proxy army, PLA’s Strategic Support Force, public opinion/media warfare, cyber warfare, Confucius Institutes

In October 2019, Commandant of the Marine Corps General David H. Berger identified the People’s Republic of China (PRC) as “the long-term existential threat to the U.S.”2 The Marines would be the “first-responder to any fight that bubbles up,” said Berger, “quickly getting to the scene to ‘freeze’ the conflict and allow diplomats to de-escalate, ideally, or for the military to send in follow-on forces if called upon.”3 Kinetic conflict with the PRC has not happened yet, but that fact should offer little comfort or consolation for U.S. national security leadership. In reality, the PRC is already at war with the United States, and with much of the rest of the world—but not in the traditional sense.

The PRC is fighting this war for global influence and control to achieve its expansionist China Dream.4 The PRC’s weapons include coercion, corruption, deception, intimidation, fake news, disinformation, social media, and violent covert operations that rely on physical assault, kidnapping, and proxy army warfare. The PRC prefers to win this war by never having to fire a shot, but its increasingly powerful military and paramilitary forces loom ominously in the background in support of its expanding war of influence.

In the minds of Chinese Communist Party (CCP) rulers, this war is designed to restore China’s former imperial grandeur as the Middle Kingdom—to once again be what China’s rulers have called “Everything Under the Sun,” the all-powerful Hegemon Power (Baquan).5 It is a war to ensure the CCP’s total control over the Chinese population and resources, as well as those of what China has historically called the barbarian states—nations nearby (e.g., Thailand and Japan) and global (e.g., European, African, and South American countries).

Much like the emperors of the Celestial Empire at its zenith, the CCP effectively classifies other barbarian nations as either tributary states that recognize the PRC’s hegemony or as potential enemies.6 Despite the professed intention of simple, peaceful “national rejuvenation” reflected in Xi Jinping’s China Dream, the CCP has demonstrated expansionist intentions and its actions reflect no desire for equality among nations.7 Rather, it seeks to impose its all-encompassing civilization on other, lesser states, consistent with the book by a PLA officer that provided the ideological foundation of Xi’s China Dream.8 Of greatest concern, Xi’s China Dream is one of unrepentant, totalitarian Marxist-Leninism.9

For the CCP, this is a total war for regional and global supremacy, and it takes the form of military, economic, informational, and—especially—political warfare. A detailed definition of political warfare will be provided later, but a simple description follows: political warfare employs all means at a nation’s command—short of war—to achieve its national objectives. These means range from overt actions such as political alliances, economic measures, and public diplomacy, to covert operations, including coercion, disinformation, psychological warfare, assassination, criminal activities, violent attacks, and support for proxy armies and insurgencies.

The PRC’s political warfare is both defensive and offensive in nature: it takes the form of unrestricted warfare, and it is conducted on a global scale.10 Most recently, the world has seen Beijing’s political warfare apparatus engaged in a massive global effort “aimed at redirecting blame [for the COVID-19 crisis] away from China and sowing confusion and discord among China’s detractors.”11

As a prelude to this article, it is crucial to establish the answer to some key questions: Why does it matter that the PRC seeks regional and ultimately global hegemony? Why cannot the world simply accept and abide a rising China, a seemingly benign term employed by PRC propaganda organs? Why should the world be concerned about China’s long-term strategy, extensively detailed in Michael Pillsbury’s highly acclaimed book The Hundred-Year Marathon, to replace America as the global superpower?12 What is there to fear about “China’s peaceful rise” and the CCP’s goal of a “Chinese-led world order”?13

After all, should the United States be concerned if, say, a rising Brazil or a rising India or a rising Taiwan sought regional hegemony and proclaimed its intent (as a PRC defense white paper proclaimed) to “lead the world into the 21st Century”?14 The answer is simple, and stark: the PRC is an expansionist, coercive, hypernationalistic, militarily powerful, brutally repressive, fascist, and totalitarian state that wants to reshape the world in its image. The world has seen what happens when expansionist, totalitarian regimes such as the PRC are left unchallenged and unchecked. In a hegemonic world, people are subjects—simply property of the state. There is no place for ideals such as democracy, popular sovereignty, inalienable rights, limited government, independent thought, free expression, and rule of law.

The PRC’s totalitarian nature is explored in detail in this article, but it is useful here to lay a foundation regarding general characteristics of totalitarianism, such as identification of the individual as merely a subject of the state; total control of media, education, and entertainment; control of major economic sectors; lack of governmental checks and balances; control by a single party, with a separate chain of control alongside the government; personality cults; militarism; a contrived historical narrative of humiliation leading to hypernationalism; and an entitlement to aggression. These characteristics were witnessed in the twentieth century in Adolf Hitler’s Germany, Vladimir Lenin’s Soviet Union, Benito Mussolini’s Italy, Imperialist Japan, and Pol Pot’s Cambodia. Such political structures and narratives established a divine right of governance for dictatorships and empires like the PRC long before the founding of the CCP. There is nothing new or inherently Chinese about totalitarian fascism.

The threat that modern totalitarian Sino-Fascism poses is, however, unprecedented. The power of modern technology and the PRC’s rapid convergence of massive economic, military, and political power, position it to be—as Canada’s top-rated think tank, the Fraser Institute, asserts—“world freedom’s greatest threat.”15

The PRC has become a hegemon bent on controlling the world’s resources, ostensibly to benefit China—but in reality to benefit the roughly 6.5 percent of its population who are Chinese Communist Party members. In addition to brutally repressing China’s population, the CCP has proven it can effectively leverage the openness of democratic systems to achieve hegemony over those democracies.16 It prefers to do this peacefully if possible: not really without a struggle but ideally without kinetic combat—without “firing a shot.”17 However, the PRC has repeatedly signaled that it is now strong and confident enough to fight a war to achieve that hegemony, even if it must pay a very large price.18

As the PRC builds a navy that will, in 10 years, be roughly twice the size of the U.S. Navy and will be “perhaps qualitatively on a par with that of the U.S. Navy” as it adds multiple-warhead, maneuverable hypersonic missiles to its triad nuclear strike capability that now covers the entire U.S. mainland, Beijing flouts international law and increasingly eschews existing rules and norms.19 According to U.S. vice president Michael R. “Mike” Pence, the PRC relies instead on coercion and corruption to achieve its economic, military, and diplomatic aims.20 Beijing’s strategies include “fracturing and capturing regional institutions that could otherwise raise collective concerns about China’s behavior, and intimidating countries in maritime Asia that seek to lawfully extract resources and defend their sovereignty,” according to Ely Ratner of the Council on Foreign Affairs.21

The PRC’s political warfare apparatus is a key weapon of compellence in its drive for regional and, ultimately, global hegemony, and its arsenal of coercive weapons is immense. Brutal internal repression is one well-documented form of the PRC’s unique brand of political warfare. Amnesty International and the U.S. government have criticized the PRC for imprisoning at least a million Uighurs in so-called reeducation camps under particularly brutal circumstances.22 In fact, the repression of Uighurs and other Muslim sects is part of a much more insidious trend: the Washington Post editorial board assesses that “China’s systematic anti-Muslim campaign, and accompanying repression of Christians and Tibetan Buddhists, may represent the largest-scale official attack on religious freedom in the world.”23 The late 2019 release of the PRC’s secret China Cables from 2017 provides confirmation of the gross atrocities and brutal repression against Uighurs.24 The cables provide irrefutable evidence of the power and intensity with which the PRC uses political warfare against its minorities. Beijing has employed both military/police operations and political warfare to crush unique cultures and democratic freedoms in Kashmir, Tibet, Tiananmen Square, and North Korea—and potentially it will use both military and political warfare to subjugate Hong Kong and Taiwan when it feels powerful enough to do so.

The PRC’s internal political repression entails a brutality much more lethal than religious suppression and thought control: the CCP is responsible for the deaths of millions of Chinese people during disastrous large-scale reigns of terror such as the Great Leap Forward (1958–60), the Cultural Revolution (1966–76), and smaller-scale atrocities such as the Tiananmen Square Massacre in 1989. Scholars such as Hong Kong-based historian Frank Dikötter have confirmed, based on the PRC’s archives, that during the Great Leap Forward alone, “systematic torture, brutality, starvation and killing of Chinese peasants [occurred and]. . . . At least 45 million people were worked, starved or beaten to death in China over these four years.”25 The Cultural Revolution resulted in the murder of at least 2 million more, and “another 1 to 2 million were killed in other campaigns, such as land-reform and ‘anti-rightist’ movements in the 1950s.”26 Estimates of Chinese killed directly or indirectly through CCP political warfare against its own population are strongly debated, but they range as high as 70 million deaths during peacetime.27

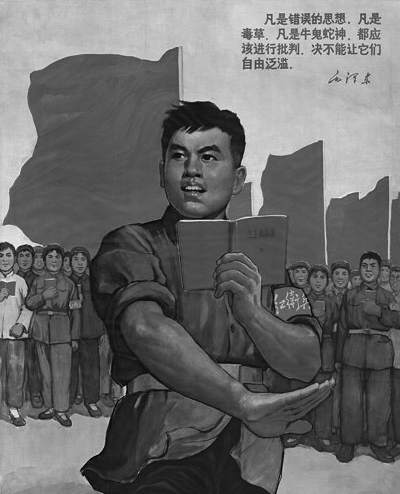

Figure 1. Translation: Criticize the old world and build a new world with Mao Zedong Thought as a weapon. This 1966 propaganda poster was one of many produced during the Cultural Revolution (1966–76) to encourage young Red Guards to study Mao to “scatter the old world and build a new world.”

Source: “Cultural Revolution Campaigns (1966–1976),” Chineseposters.net.

While there is debate regarding the total number of Chinese killed by the CCP, there is no doubt that the Chinese Communist Party that is responsible for what amounts to mass murder still tightly holds the reins of power in the PRC and that it reveres the man who presided over the deadliest repression: Mao Zedong. Evidence of the CCP’s continued reverence for Mao includes what China Daily described as the “unprecedented” respect and “piety” Xi and the CCP displayed for Mao during the 70th anniversary of the PRC extravaganza in October 2019.28

While the PRC’s “propaganda machine has mastered the power of symbol and symbolism in the mass media” and many Chinese eagerly embrace its hypernationalistic patriotic education programs, those residing in the PRC face censorship and thought control unimaginable to most citizens of liberal democracies.29 Of even greater concern, the CCP’s censorship and thought control have gone global: through its extensive propaganda and influence tentacles, Beijing disregards rules or actions that, in the CCP’s view, contain China’s power or “hurt the feelings of the Chinese people.”30 The PRC’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs and propaganda organs lambast as “immoral” those who criticize its egregious human-rights abuses and as “racist” those who object to overseas Chinese malign influence activities.31

The CCP’s draconian censorship ensnares American institutions such as the National Basketball Association, who was recently chastised by the Washington Post editorial board for “essentially importing to the United States China’s denial of free speech.”32 Further, an increasingly punitive Beijing now routinely censors world-famous brands, such as Marriott, United Airlines, Cathay Pacific Airways, Givenchy, and Versace.33 Hollywood has been co-opted “to avoid issues that the Chinese Communist Party would consider sensitive and produce soft propaganda movies that portray China in a positive light to global audiences.”34 Beijing is very clear in conveying its coercive censorship requirements, as reflected with the Global Times headline: “Global Brands Better Stay Away from Politics.” The article condemned “so-called ‘freedom of speech’ ” and carried explicit and implicit threats to those who did not toe the CCP line.35

Beijing also exports violence to other countries in support of its political warfare activities abroad. One example is its use of proxy armies. The PRC’s support of its proxy armies in Myanmar seems an anomaly to many contemporary diplomats, academics, and journalists, but such support has been the norm for the CCP since the founding of the People’s Republic of China.36 Its proxy armies across Southeast Asia kept the United States and its allies in the region distracted and cost them dearly for more than four decades of the Cold War.37

Economic coercion has become a particularly visible PRC political warfare tool, as the CCP uses the promise of its global One Belt, One Road (OBOR) scheme (also called Belt and Road Initiative, or BRI) to build what China Daily describes as “a new platform for world economic cooperation.”38 The U.S. assistant secretary of state for East Asia and Pacific Affairs, David R. Stilwell, characterizes OBOR and related PRC economic coercion less charitably: “Beijing . . . [employs] market-distorting economic inducements and penalties, influence operations, and intimidation to persuade other states to heed its political and security agenda.”39 Vice President Mike Pence’s foreign policy speech of 4 October 2018 specifically details American concerns regarding the PRC’s use of destructive foreign direct investment, market access, and debt traps to compel foreign governments to acquiesce to its wishes.40

Of equal concern, the PRC shapes public opinion inside and outside its borders “to undermine academic freedom, censor foreign media, restrict the free flow of information, and curb civil society,” according to Ely Ratner.41 Worldwide, countries have belatedly awakened to the remarkable degree to which the PRC’s diplomatic, economic, and military interests—and with these, the PRC’s malign influence—have infiltrated their regions, such as Australia and New Zealand as well as countries across Europe, Oceania and the Pacific Islands, South America, the Arctic nations, and many African countries.42 Canada and the United States have had equally rude awakenings regarding the efficacy of the PRC’s ability to co-opt institutions, organizations, and people (called “united front” operations) and other forms of PRC coercion, repression, and violent attacks within their borders.43

Of particular concern to the U.S. military is the PRC’s highly successful employment of political warfare operations to co-opt retired senior U.S. military officers to lobby on behalf of PRC objectives and to undermine U.S. national security objectives.44 The PLA has successfully co-opted retired U.S. military flag and general officers through organizations such as the Chinese Association for International Friendly Contact (CAIFC) and other programs such as the Sanya Initiative.45

Established in December 1984 as a political warfare platform, CAIFC’s “main function is establishing and maintaining rapport with senior foreign defense and security community elites, including retired senior military officers and legislators.”46 CAIFC routinely sponsors retired U.S. officers for free visits to the PRC for what amounts to political indoctrination sessions. According to Mark Stokes and Russell Hsiao, “CAIFC facilitates influence operations through PRC foreign affairs, state security, united front, propaganda systems, and military systems.”47 To entice American and other foreign retired military officers, “CAIFC serves as a window to China’s broader business community.” In some cases, foreign retired officers have been required to “agree to publish editorials supporting China [sic] position and criticize U.S. regional policy in exchange for business development support in China.”48

The Sanya Initiative began in February 2008 as a PRC initiative to influence senior retired U.S. flag and general officers to support PRC security interests. At the first meeting at Sanya Resort on the PRC’s Hainan Island, senior PRC political warfare and intelligence officers led the PLA side, and U.S. participants were led by retired Admiral (and former Vice Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff) William A. Owens. According to a Congressional Research Service report on the Sanya Initiative, “The PLA side asked the U.S. participants to help with PRC objections to U.S. policies and laws: namely the Taiwan Relations Act (TRA), Pentagon’s report to Congress on PRC Military Power, and legal restrictions on military contacts in the [National Defense Authorization Act] NDAA for FY2000.”49 Meetings were subsequently held during 2009, in Honolulu, Hawaii; Washington, DC; and New York City. As a result, Owens (who had business interests in China as a managing director of AEA Investors in Hong Kong) published an opinion piece opposing the Taiwan Relations Act as harmful to the relationship with a rising great power—China—that has increasing wealth and influence in the world.50 Owens and certain other U.S. officers continued to meet with senior CCP officials and to support PRC security objectives in discussions with members of Congress and DOD officials.51

Senior officials of allied and friendly countries are also targeted by CAIFC and similar programs, particularly through academic and think tank affiliations. For example, a think tank called the National Institute for South China Seas Studies (NISCSS), located on Hainan Island, focuses on persuading foreign retired and serving officials that the PRC is entitled to own the South China Seas. To this end, NISCSS has established collaborative links with institutions such as the University of Alberta, the Korea Institute for Maritime Strategy, International Ocean Institute (Canada), Center for Southeast Asian Studies (Indonesia), and a South China Seas-themed summer camp organized by Nanjing University. Senior academics and retired military personnel from South Korea, Australia, Indonesia, and Taiwan (as well as other countries) continue to attend NISCSS seminars.52

Australian journalist John Garnaut captures the nature of the long-overdue awakening concerning the PRC’s political warfare—and the disturbing lack of consensus on response:

Belatedly, and quite suddenly, political leaders, policy makers and civil society actors in a dozen nations around the world are scrambling to come to terms with a form of China’s extraterritorial influence described variously as “sharp power,” “United Front work,” and “influence operations”. . . . A dozen others are entering the debate. But none of these countries has sustained a vigorous conversation, let alone reached a political consensus.53

The use of political warfare is not unique to the PRC, of course. During the Cold War, the United States and other democratic countries engaged in an ultimately successful political warfare effort to bring down the Soviet Union’s Iron Curtain.54 But the PRC version of political warfare is different than the other states, and it seeks to achieve more through its influence and political warfare operations than other states, according to Singapore’s former ambassador Bilahari Kausikan, a highly respected expert of PRC malign influence. Kausikan notes that China is a totalitarian Leninist state that takes a holistic approach, which melds together the legal and the covert in conjunction with persuasion, inducement, and coercion. He identifies the aim of the PRC is not simply to direct behavior but to condition behavior.55 “In other words, China does not just want you to comply with its wishes,” Kausikan asserts, but “far more fundamentally, it wants you to think in such a way that you will of your own volition do what it wants without being told. It’s a form of psychological manipulation.”56

As it wages global political war to achieve its political, economic, and military ends, China exports authoritarianism, as detailed by the National Endowment for Democracy.57 Beijing intentionally undermines the credibility of democracy and individual freedoms to bolster support for its own totalitarian regime—what it calls the China Model.

While there has been relatively recent bipartisan agreement in the United States regarding the need to confront the general threat posed by the PRC, there is still insufficient attention devoted to countering the threat of PRC political warfare. Based on the author’s discussions with senior National Security Council officials and DOD and Department of State officials, there has been, until relatively recently, a lack of will to identify and confront PRC political warfare. Consequently, as Garnaut observed, there is no comprehensive approach at the strategic and operational levels that bring a common vision, coherency, and the necessary resources to fight it.

Specific weaknesses of the United States and other democracies in combating PRC political warfare are delineated by a 2019 Center for Strategic and Budgetary Assessments report. Key weaknesses include the fact that there is little consensus about or clearly defined strategic goals within or between Western countries; no powerful strategic narrative to provide a strong focus for a counterauthoritarian political warfare campaign; no clearly defined strategy or game plan to drive coalition political warfare operations; and universally weak levels of experience, culture, and doctrine in the field of political warfare, even though some Western countries possessed substantial political warfare expertise during the Cold War. Also worth noting is the fact that politicians, business people, media personalities, and the general population are poorly informed regarding the political warfare challenges they face, and are ill-prepared mentally and practically for the long struggle ahead.58

Organizations such as Project 2049 Institute, Hudson Institute, Center for Strategic and Budgetary Assessments, Jamestown Foundation, and Global Taiwan Institute, as well as individual scholars and reporters, have provided superb analysis and reports on PRC political warfare. Nevertheless, relatively little open-source academic literature is written in English on the subject. Of particular concern is the significant deficiency in academic research in both civilian and U.S. government educational institutions regarding the PRC’s comprehensive political warfare strategies.

As previously noted, the United States was once adept at conducting political warfare. During the Cold War, the United States successfully waged political warfare against the Communist Bloc through a variety of mechanisms, including such overt actions as building political alliances and initiating economic development (i.e., the Marshall Plan in Europe). American agencies also used “white” propaganda (the source is identified), covert operations using the clandestine support of friendly foreign elements, and “black” psychological warfare (the source is concealed). The United States also encouraged underground resistance in hostile states, covertly funded non-Communist political parties, covertly started magazines and organizations to organize artists and intellectuals against Communism, and provided financial and logistical support to dissidents behind the Iron Curtain and military support for freedom fighters.59

Looking to the future, the United States must invest heavily and with great urgency now to inoculate our institutions, military forces, and citizens against the existential threat posed by PRC political warfare, and to effectively counter the threat. The Marine Corps and the other military Services must first understand the political warfare threat, however, then engage in the fight and ultimately win the war.

PRC Political Warfare: Goals, Ways, Means, and Wartime Support

Political Warfare Goals

In congressional testimony, Princeton’s Professor Aaron L. Friedberg identified four strategic goals for the CCP, and hence for its political warfare operations: “First and foremost,” said Friedberg, “to preserve the power of the CCP. Second, to restore China to what the regime sees as its proper, historic status as the preponderant power in eastern Eurasia. Third, to become a truly global player, with power, presence and influence on par with, and eventually superior to, that of the United States.”60

Further, Friedberg asserts that the PRC rejects concepts the CCP derisively refers to as “ ‘so-called universal values’: freedom of speech and religion, representative democracy, the rule of law, and so on,” which threaten the legitimacy of the CCP. Accordingly, the PRC has worked “openly and vigorously to make [the world] safe for authoritarianism, or at least for continued CCP rule of China.” He says the PRC’s efforts have “intensified markedly” since the rise to power of Xi Jinping in 2012.61

A 2018 Hudson Institute study provides an apt, if somewhat informal, description of PRC political warfare goals, target audiences, and strategies:

With the United States, whose geostrategic power the Party perceives as the ultimate threat, the goal is a long-term interference and influence campaign that tames American power and freedoms, in part by limiting and neutralizing American discussions about the CCP. Liberal values such as freedom of expression, individual rights, and academic freedom are anathema to the Party and its internal system of operation.62

The CCP, by changing how democracies speak and think about the PRC, is making the world safe for its continued rise. However, as Friedberg testified, PRC political warfare goals extend well beyond CCP self-preservation. These goals include restoring China to what the CCP sees as its rightful place as the Middle Kingdom, particularly in eastern Eurasia but also across more distant continental and maritime domains. Concurrent with its intent to drive the United States from the Asia-Pacific region, Beijing’s goal is to take physical possession of Taiwan.

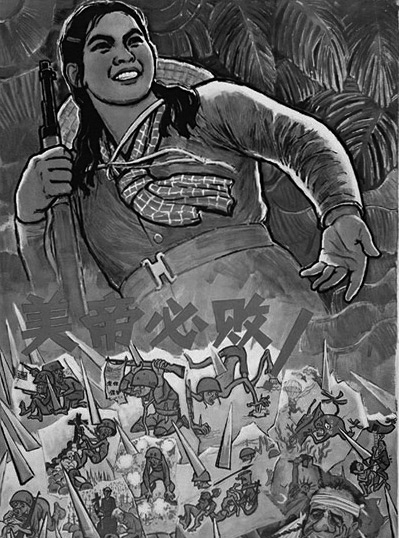

Figure 2. Translation: American imperialism must be beaten! This 1965 poster reflects a PRC propaganda theme that continues through present day: that U.S. defense of its friends and allies is “imperialism” and must be defeated.

Source: “Foreign Friends: Indo-China,” Chineseposters.net.

Taiwan remains the central focus of PRC political warfare. Stokes and Hsiao write that “from Beijing’s perspective, Taiwan’s democratic government—an alternative to mainland China’s authoritarian model—presents an existential challenge to the CCP’s monopoly on domestic political power.”63 The CCP’s desired final resolution of the Chinese civil war entails the destruction of the political entity called the Republic of China (commonly known as Taiwan), and absorbing Taiwan as a province into the PRC. Consequently, taking Taiwan represents a key milestone in what Xi describes as “national reunification”—and he has clearly stated he will use all means, including force, to obtain it if necessary.64 Of greater concern, Friedberg concludes that the PRC has “stepped up its use of influence operations to try to undermine and weaken the ability of other countries to resist its efforts. Ultimately Beijing appears to envision a new regional system extending across Eurasia, linked together by infrastructure and trade agreements, with China at its center, America’s democratic allies either integrated and subordinated or weakened and isolated, and the United States pushed to the periphery, if not out of East Asia altogether.”65 A brief examination of the ways and means the PRC devotes to its political warfare efforts to achieve these goals follows, including a brief overview of the PRC’s political warfare traits and organization. Additionally, this article will describe how political warfare supports the PRC’s wartime and other military operations.

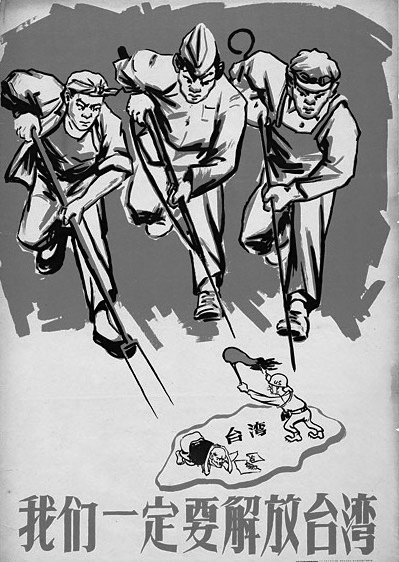

Figure 3. Translation: We must liberate Taiwan. Although the PRC’s planned 1950 invasion of Taiwan was foiled by the intervention in the Korean War, this 1958 propaganda poster supported Beijing’s psychological warfare against Taipei and Washington, with Beijing’s continuing threat to seize the island by force. Unification with Taiwan remains the primary PRC political warfare objective today.

Source: “Taiwan – Liberation,” Chineseposters.net.

PRC Political Warfare Traits

Common characteristics of the PRC’s political warfare strategy include such elements as a strong centralized command of political warfare operations by the CCP through organizations like the United Front Work Department (UFWD) and the PLA. These organizations provide a clear vision, ideology, and strategy, and they employ overt and covert means to influence, coerce, intimidate, divide, and subvert rival countries to force their compliance.

Key traits of the PRC’s political warfare programs include tight control over the domestic population and detailed understanding of targeted countries. To achieve its goals, the CCP employs a comprehensive range of instruments in coordinated actions, and exhibits a willingness to accept a high level of political risk from the exposure of its activities.

Ways and Means: Funding and Economic Aspects

China is the world’s second-largest economy, and the CCP has invested enormous resources into “influence operations” abroad, estimated at $10 billion a year in 2015.66 Current funding is likely significantly higher, but credible data is unavailable. Further, the PRC’s OBOR initiatives provide access to additional political warfare support resources, as OBOR can be rightly viewed as a global United Front Work Department strategy.67

Cash is vital in this global political war, augmented as needed by threats of overt or covert military, economic, or other attacks. Unlike the Cold War, in this current political war with the PRC, ideology plays little role. As Lum et al. explain,

At hardly any time did countries aspire to adopt the Chinese model. Mao’s disastrous Great Leap Forward, Cultural Revolution, collective farms, state owned enterprises, egalitarian poverty (except for Party insiders), and repressive government had little appeal except to other dictatorial regimes.68

Beijing’s phenomenal economic growth during the past three decades has provided a different model, based on what is termed the Beijing Consensus that largely rejects most Western economic and political values and models.69 The main attribute of this PRC model is for people to be “brought out of poverty, not necessarily to have legal freedoms.”70 With the scale and relatively rapid growth of the Chinese economy, the CCP is indeed helping many political, news media, and other influential elites worldwide come, as the CCP characterizes it, out of poverty. Cash, combined with the massive growth of the PLA and its ever-watchful political warfare and intelligence apparatus, have proven to be the compelling motivators for those supporting and enabling the PRC’s global ambitions.

Beyond funding political warfare operations, Beijing frequently employs economic instruments in its political warfare campaigns. The PRC is the largest trading partner for nearly all countries in the Western Pacific, and Beijing’s goodwill is important for their development and prosperity. Indeed, in the Western Pacific, the PRC adheres to the plan detailed in its Blue Book of Oceania.71 In China, Blue Books are “made available to all government departments, stocked in Xinhua Bookstores across China, and are seen as the standard reference on any given topic.”72 The Chinese government’s interest in Oceania has increased significantly in recent years, with massive increases in aid, trade and investment, and diplomacy that have surprised many in the United States and other affected governments.73 As noted by Babbage, the Chinese have many ways to apply pressure to countries by using economic incentives such as tourism sanctions, boycotts of corporations, and other reprisals, including its pressure campaign of South Korea for its commitment to host American missile defense systems.74

Organization

A number of party and state organizations support the CCP’s political warfare operations, and it is useful to provide a very brief overview of how some of the key elements interrelate. Peter Mattis writes that there are three layers within this system: the responsible CCP officials, the executive or implementing agencies, and supporting agencies that bring platforms or capabilities to bear in support of united front and propaganda work. On the first level, several CCP officials oversee the party organizations responsible for political warfare and supporting influence operations. The organization flows down from the Politburo Standing Committee (PSC). The senior-most united front official is the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference (CPPCC) chairman, who is the fourth-ranking PSC member. The other two officials are the PSC members who direct the UFWD and the Propaganda Department. They often sit on the Secretariat of the CCP, which is empowered to make day-to-day decisions for the routine functioning of the party and state, which are synonymous in the PRC.75

The UFWD is the executive agency for united front work, with responsibilities within the PRC and abroad. The UFWD operates at all levels of the party system, and its purview includes Hong Kong, Macao, and Taiwan affairs; the Overseas Chinese Affairs Office of the State Council (OCAO); ethnic and religious affairs; domestic and external propaganda; entrepreneurs and nonparty personages; intellectuals; and people-to-people exchanges. The department also leads the establishment of party committees in Chinese and foreign businesses.76 The OCAO is particularly important in rallying the worldwide diaspora. OCAO’s mission statement maintains that it works “to enhance unity and friendship in overseas Chinese communities; to maintain contact with and support overseas Chinese media and Chinese language schools; [and] to increase cooperation and exchanges between overseas Chinese and China related to the economy, science, culture and education.”77

Propaganda and United Front Work Departments

According to the Jamestown Foundation, the UFWD has reorganized in recent years and now has a total of 12 professional bureaus. The responsibilities of the bureaus range from policy in Xinjiang and Tibet, to businesspeople and Chinese diaspora communities. The UFWD has added six bureaus to its structure in the past three years to increase the CCP’s power to directly influence religious groups and overseas Chinese, as well as to target members of “ ‘new social strata’ . . . such as new media professionals and managerial staff in foreign enterprises.”78

In addition to the UFWD, a range of CCP military and civilian organizations actively carry out united front work, either working directly for the UFWD or under the broader leadership of the CPPCC. For instance, the Taiwan-related China Council for the Promotion of Peaceful Nationals Reunification of China (CPPNRC) carries out united front work for the PRC. CPPNRC has at least 200 chapters in 90 countries, including 33 chapters in the United States registered as the National Association for China’s Peaceful Unification.79

The Propaganda Department’s duties include conducting the party’s theoretical research; guiding public opinion; guiding and coordinating the work of the central news agencies, including Xinhua and People’s Daily; guiding the propaganda and cultural systems; and administering the Cyberspace Administration of China and various state administrations pertaining to press, publication, radio, film, and television.

On the third level, many other party-state organizations contribute to influence operations. Their focus may not be on united front or propaganda work, but they still have capabilities and responsibilities that can be used for these purposes. Many of these agencies share cover or front organizations when they are involved in influence operations; Mattis reports that such platforms are sometimes lent to other agencies when appropriate. The principal political warfare organizations report to the PSC through their own separate chain of command that deals mostly with party affairs, according to Mattis.80

The PLA and Chinese Intelligence Organizations

The PLA plays a significant role in PRC political warfare. Under the leadership of the CCP Central Military Commission (CMC), the PLA General Political Department/Liaison Department (GPD/LD) is the PLA’s principle political warfare command. Policy analyst J. Michael Cole describes the GPD/LD as “an interlocking directorate that operates at the nexus of politics, finance, military operations, and intelligence.”81

Hsiao and Stokes note that GPD/LD liaison work augments traditional state diplomacy and formal military-to-military relations, which are normally considered to be the most important aspects of international relations. The GPD/LD, the UFWD, and other influence organizations play a role in setting up and facilitating the activities of a multitude of friendship and cultural associations, such as the previously described CAIFC, a key organization in co-opting foreign military officers.

PRC intelligence organizations (Chinese Intelligence Service or CIS, and Ministry of State Security or MSS) seem to play a secondary role in foreign influence operations, says Mattis. Beijing’s participants in exchanges organized with these organizations are rarely intelligence officers themselves, but are usually party elite who understand the party’s objectives and are skilled in managing foreigners. There is a seemingly compartmented role for intelligence in the overall political warfare and influence spectrum.82 But MSS and CIS are certainly engaged in political warfare active measures, and intelligence collection is always an integral part of political warfare’s success during political warfare operations.

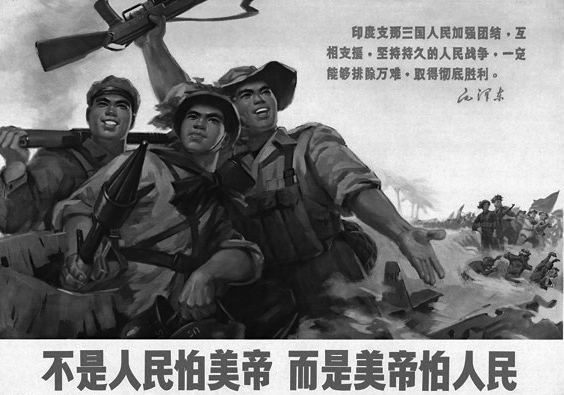

Figure 4. Translation: The people do not fear the American imperialists, but the American imperialists fear the people. This propaganda poster highlights the PRC’s support for national liberation forces across Southeast Asia, to include Thailand, Laos, Cambodia, and Vietnam. The PRC provided political warfare, military personnel, and material support that led to Vietnam, Cambodia, and Laos falling to Communist forces.

Source: “Foreign Friends: Indo-China,” Chineseposters.net.

Political Warfare in Support of PLA Combat Operations

Through the use of political warfare and deception, the PRC has achieved notable strategic victories without fighting.83 However, if the PRC’s rulers perceive that political warfare alone will not deliver the results it desires regarding Taiwan, the South China Seas, or with India, the PRC may achieve its goals through planned combat operations, or a war may inadvertently ignite from its actions.84

In any armed conflict within the Asia-Pacific region (or globally), the PRC’s fight for public opinion will be their second battlefield, on which it will wage a wide range of political warfare operations. The PRC has used political warfare to support past combat operations, seen in the 1950 invasion of South Korea, the 1951 occupation of Tibet, the 1962 Sino-Indian War, the 1969 border battles with the Soviet Union, the 1974 assault on the Paracel Islands, the 1979 invasion of Vietnam, the 1988 Spratly Islands attack, the 1995 occupation of Mischief Reef, and the recent standoff with India and Bhutan at Doklam.85

The PRC’s doctrinal principle of uniting with friends and disintegrating enemies guides PRC active political warfare measures to promote its rise and to combat perceived threats.86 Its political warfare operations propagate the CCP’s narrative of events, actions, and policies to lead international discourse and influence policies of both friends and adversaries.

Military officers become acquainted with political warfare concepts early in their careers and study it in-depth as they rise in rank. Their resources include PLA texts on military strategy, such as the 2013 Academy of Military Science’s edition of Science of Military Strategy and the 2015 National Defence University’s edition of Science of Military Strategy.87 Other texts include teaching materials used by the PLA National Defence University, such as An Introduction to Public Opinion Warfare, Psychological Warfare, and Legal Warfare.88

Based on available literature and experience, the PRC will engage in hybrid warfare, similar to—but possibly more sophisticated than—that employed in Russia’s 2014 seizure of Crimea.89 In Crimea, Russia employed hybrid and political warfare strategies as assistance to local groups, including criminal and terrorist organizations and mobilization of the Russian diaspora. Russia also created credible online channels that camouflaged Russian sponsorship and recruited a strong network of “agents of influence” and “fellow travelers” who were committed to Russia’s cause.90

The doctrine, concepts, and capabilities that the PRC employs include “military and para-military forces that operate below the threshold of war, such as increased presence in contested waters of fishing fleets and supporting maritime militia and navy vessels. These operations might spark conflict when an opposing claimant such as the Philippines, Vietnam, or Japan responds.”91 Further, the PRC is already engaged in hybrid warfare against Taiwan, so these types of operations would likely increase in preparation for an attack on the island nation.92

The PRC will augment conventional military operations with nonconventional operations, such as subversion, disinformation and misinformation (commonly referred to as “fake news”), and cyberattacks. The operationalization of psychological operations (psyops) with cyber capabilities is key to this strategy. China has fully empowered its psychological warfare forces, most notably the Three Warfares Base (or 311 Base) in Fuzhou, China, on the mainland.93 This base “is responsible for strategic psychological operations and propaganda directed against Taiwan’s society. . . . [and the PLA] has been suspected of cyber espionage against Taiwan government networks.”94 It was subordinated to the PLA’s Strategic Support Force and is integrated with China’s cyberforces.95

Doctrinally, China will employ political warfare before, during, and after any hostilities it initiates. Prior to a military confrontation, China often initiates a political warfare campaign worldwide. This includes the employment of united front organizations and other sympathizers to initiate protests, support rallies and other actions, including the use of mass information channels such as the internet, social media, television, and radio for propaganda and psyops. History shows political warfare efforts are often tied into China’s strategic deception operations. Deception is designed to confuse or delay an adversaries’ defensive actions until it is too late to effectively respond.

A Fall 2017 Marine Corps University Journal article describes how conflict with China might begin.96 The PLA would gain the initiative by striking the first blow—that is, it is the PLA’s “absolute requirement to seize the initiative in the opening phase of a war.” Regarding triggers that prompt the first strike, China’s policy stipulates that “the first strike that triggers a Chinese military response need not be military; actions in the political and strategic realm may also justify a Chinese military reaction.” That could be a perceived slight, diplomatic miscommunication, or statement by a government official that supposedly justifies Chinese military reaction.97

Prior to initiating an offensive or other military confrontation, the PRC will use worldwide psyops and public opinion warfare as part of a concerted political warfare campaign, as it did before (and during) the Doklam confrontation with India.98 As with the Doklam confrontation, the PRC will employ united front organizations and other sympathizers, along with both Chinese and other-nation mass information channels, such as the internet, television, and radio. As the PLA Navy, Air Force, Rocket Forces, Strategic Support Forces, and other forces engage in kinetic combat against targeted enemy forces, the CCP will already be fighting for worldwide public opinion on this second battlefield to shape perceptions globally. The focus of these influence operations will be to support China’s position and demonize, confuse, and demoralize the United States, Japan, Taiwan, and its supporting friends and allies. The global campaign also will attempt to win support for the PRC’s position from initially undecided nations.

As previously noted, in addition to standard propaganda, disinformation and deception will be employed. Disinformation and deception will likely include false reports of surrender of national governments and/or forces, atrocities and other violations of international law, and other reports intended to distract or paralyze decision making by the United States and its friends and allies. Internally, the political warfare campaign in support of the combat operations will be important in mobilizing mass support for the PRC’s actions. This political warfare campaign will continue through the military confrontation and after—regardless of the success or failure of the operation.99

Recommendations

The purpose of this article is to provide knowledge regarding the PRC’s extensive political warfare operations in general and to provide recommendations for the United States to successfully combat these operations. The United States and its friends and allies face a relentless, multifaceted onslaught of PRC political warfare strategies, tactics, techniques, and procedures but, as in the Cold War, if the United States shows the strength and leadership to fight back, friends and allies will follow. This research should prove useful in helping the United States to establish and lead allies and partner nations to counter PRC political warfare. Respected individuals such as Peter Mattis and institutions such as the Hudson Institute and the Center for Strategic and Budgetary Assessment have provided a range of recommendations to counter PRC political warfare.100 Some of the recommendations below draw on their excellent work.

As a matter of policy, the United States government, to include the DOD and the Department of State, must call the PRC political warfare threat by its rightful name: political warfare. The PRC is engaged in warfare against the United States: not mere strategic competition or malign influence—it is an information or disinformation war for influence, by PRC definition. Words matter. Proper terminology leads ideally to proper national goals, objectives, policies, and operations. That is why American diplomat and historian George F. Kennan wrote both the successful strategy of Soviet containment and on counterpolitical warfare strategy in straightforward terms. The United States must educate our internal and external audiences that China is at war with us—and why and how we will successfully confront that existential threat.

The United States must mandate the development of a national strategy to counter PRC political warfare, with appropriate legal authority to compete successfully regarding organization, training, manpower, and funding. Through legislation, require a comprehensive approach, and include the requirement to appoint a highly respected coordinator for political warfare within the National Security Council, and the development of counter-political warfare career paths in diplomatic, military, and intelligence organizations, similar in concept to the recently established cyber operations occupational specialty.

The Center for Security and Budgetary Assessment’s political warfare study cited in this article provides an excellent delineation of steps to be taken to build a strategy: first, the United States must state its goals in combating political warfare, particularly the PRC’s version, and develop a theory of victory and an end state. Second, determine if the “goal is to force a cessation of authoritarian state political warfare and instill greater caution in . . . Beijing or, alternatively, to facilitate the demise of these regimes and their replacement by liberal democratic alternatives.”101

The United States must rebuild national-level institutions that can successfully undertake countering PRC political warfare operations. The Executive Branch and Congress must revive America’s ability to engage in information operations and strategic communication similar in scope to the capabilities that were developed during the Cold War era, to include an independent U.S. Information Agency-like organization and active measures capabilities with broader authority than the existing Global Engagement Center and external to the Department of State.102 This rebuilding includes governmental structures and capacity building with the private sector, civil society, and the news media.

The United States also should establish systematic education programs in government, industry, business, academia, and the general public regarding PRC political warfare operations. Within the DOD and the Department of State especially, establish short and long courses in senior- and intermediate-level professional courses, as well as entry-level for the foreign service, intelligence, commerce, public affairs, and education-affiliated communities. In some cases, this education program would be voluntary, as with private education institutions, the private sector (industry and business), and nongovernmental organizations. However, within the government, the training should be compulsory, including for contractors, businesses and institutions with government contracts, and publicly funded education institutions. Similarly, in coordination with news media, the private sector and civic groups should initiate public-information programs to be able to distinguish between factual information and propaganda or disinformation.

The focus of U.S. efforts should be on building internal defenses within the most highly valued PRC target audiences: political elites, thought leaders, national security managers, and other information gatekeepers. Such governmental, institutional, and public-education programs were employed successfully during the Cold War, with threat briefs and public discussion a routine part of the program.

With competent leadership, U.S. government education institutions should be able to rapidly resource and conduct a five-day course, which would include the following subjects:

- PRC political warfare history, theory, and doctrine;

- PRC political warfare practice (objectives, strategies, tactics, techniques, and procedures);

- Political warfare terminology;

- Political warfare mapping (e.g., diagramming hostile influence structures and related funding and support mechanisms, as well as intended audiences);

- National strategic communication planning;

- News media relations and social media employment;

- Intergovernmental relations;

- Civil society engagement;

- Legal and law enforcement implications;

- Defensive and offensive strategies; and

- Examples of contemporary political warfare campaigns and case studies to educate the public

Immediately available mass education instruments include Department of State and DOD public affairs media assets. As during the Cold War, public affairs information programs can be used to educate internal and external audiences about the PRC threat and to routinely expose PRC political warfare operations publicly. As a matter of policy, U.S. government public affairs assets should be used to counter anti-U.S. military three warfares operations—psyops, legal warfare (lawfare), and public opinion (media) warfare—and to expose united front operations such as CAIFC efforts to co-opt retired U.S. military officers.

The government must establish a regional Asian Political Warfare Center of Excellence (APWCE) similar to the European Centre of Excellence for Countering Hybrid Threats based in Finland. The mission of the APWCE would be similar to the European model, as reflected in the adapted proposal below:

To develop a common understanding of PRC political warfare threats and promote the development of comprehensive, whole-of-government response at national levels in countering PRC (and other country) political warfare threats.103

The APWCE would function as follows:

- Encourage strategic-level dialogue and consulting between and among like-minded participants in Asia and globally; investigate and examine political warfare targeted at democracies by state and nonstate actors and to map participants’ vulnerabilities and improve their resilience and response;

- Conduct tailored training and arrange scenario-based exercises for practitioners aimed at enhancing the participants’ individual capabilities, as well as interoperability between and among participants in countering political warfare threats;

- Conduct research and analysis into political warfare threats and methods to counter such threats; and

- Engage with and invite dialogue with governmental experts, nongovernmental experts, and practitioners from a wide range of professional sectors and disciplines to improve situational awareness of political warfare threats.

Domestically, establish task-specific government departments and agencies responsible for investigating, disrupting, and prosecuting political warfare and other illegal foreign influence activities and hold these departments and agencies accountable for success. The Department of State, Department of Defense, Department of Justice, Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI), and the intelligence agencies each play key roles in countering CCP political warfare. Based on failures in countering PRC political warfare to date and in prosecuting espionage prosecutions as described by Peter Mattis’s congressional testimony, it appears imperative to review existing laws and legislative and policy authorities and requirements that apply to PRC political warfare to ensure clear mission statements, requirements for action, and assessment of success.

The United States should increase the readiness, staffing, and training of law enforcement and counterintelligence professionals to better screen, track, and expose PRC political warfare activities. In discussions with FBI, military intelligence, and Department of State officials, it is apparent that combating PRC political warfare has not received the priority it must have to compete in resource battles within the bureaucracies. As Mattis highlights, “the Executive Branch has failed to prosecute or [has] botched investigations into Chinese espionage,” which are more straightforward to prosecute than political warfare and other influence operations.104 The U.S. intelligence community and Department of Justice personnel who perform counterpolitical warfare operations are likely the same as those who conduct counterespionage, and for them to succeed there is a need for better analytical, investigative, and legal training.

We must routinely expose PRC political warfare operations publicly. As a matter of law and policy, expose covert and overt PRC political warfare. Either by legislation or executive order, mandate an annual National Security Council-led, publicly disseminated report on the CCP’s influence and propaganda activities, similar to the President Ronald W. Reagan-era annual report on Soviet active measures, with a special focus on united front interference and influence operations that includes practical advice for ordinary citizens about how to recognize and avoid these operations. As Mattis notes, an annual report on the CCP’s activities “forced government agencies to come together to discuss the problem and make decisions about what information needed to be released for public consumption. . . .[It] would have the beneficial effect of raising awareness and convening disparate parts of the U.S. Government that may not often speak with each other.”105 A classified annex could be produced for internal government consumption.

As the Hudson Institute suggests, one way to operationalize the public exposure of PRC political warfare is for the Executive Branch to work with think tanks, journalists, academic institutions, and other civil society organizations to map out PRC political warfare operations and expose them in ways that will not harm U.S. national security. One approach would be to create a united front tracker to expose the PRC political warfare fronts, enablers, and operations and hold the organizations accountable. This tracker could, for example, expose the myriad of organizations engaged in united front activities, and activities such as taxpayer-funded conferences at universities and academic institutions that parrot PRC propaganda themes. By exposing such political warfare operations on a sustained basis, the United States will better inform its citizens of the threat they face. Also, such a tracker should also be used to publicly shame united front and other PRC political warfare operations. Such shaming can be quite beneficial, as was proven when the U.S. government took forceful action against the Republic of South Africa’s influence operations during the apartheid era. It is worth revisiting that legislation (U.S. Comprehensive Anti-Apartheid Act of 1986) and the resultant success it had in limiting South Africa’s information operations. Other steps that should be taken include publicly identifying those involved in foreign censorship and influence in the news media. Most Americans likely are unaware that PRC-based news organizations act as organs of the CCP and that their reporting is based on CCP Propaganda Department direction, as opposed to the often-independent reporting of commercial news media organizations.

We must increase the costs for CCP interference. Too often, the U.S. government has gone soft on PRC transgressions, even on American soil—often overriding U.S. law enforcement officials to accommodate illegal PRC intelligence activities. Beijing “faces few if any consequences for its interference inside the United States,” reports Mattis.106

When PRC embassy and consulate officials travel to universities to threaten students or turn them out for a rally, as they do to counter pro-democracy Hong Kong rallies and disrupt the layover of Taiwan’s president in Honolulu, the U.S. government can revoke their diplomatic status or place travel restrictions on those officials.

The United States must continue to closely monitor the various Chinese student associations, Confucius institutes, and similar institutions affiliated with the PRC and take legal action to ban them and/or prosecute PRC officials engaged in subversive activities. Although ostensibly a student support association, the real Chinese student association’s mission is to penetrate academia to subvert democratic institutions and to engage in espionage against their host country as well as academics and Chinese students matriculating abroad. Confucius institutes are also engaged in various forms of censorship, coercion, and surveillance of Chinese students and academics. To help counter them, Mattis suggests leveraging civil rights legislation. For instance, Conspiracy against Rights (18 U.S.C., Title 18, § 241) could be used against Chinese student associations, Confucius institutes, and other united front and undercover CCP intelligence and security officials. These organizations “threaten, coerce, or intimidate Chinese people (or others) in the United States.”107

Specifically, this provision makes it unlawful for two or more persons to conspire to “injure, oppress, threaten, or intimidate any person in any State, Territory, Commonwealth, Possession, or District in the free exercise or enjoyment of any right or privilege secured to him by the Constitution or laws of the United States, or because of his having so exercised the same.”108 Other related civil rights legislation could be employed as well.

The United States should advance academic study and thesis development in U.S. government higher education institutions regarding PRC political warfare, including how to contain, deter, and/or defeat the political warfare threat. Further, we should encourage research into this existential challenge and how to combat it with funding and with special high-level recognition and awards.

Finally, the United States must pass legislation to diminish the offensive power of PRC news media and social media. Freedom of the press must be scrupulously safeguarded in democracies, but allowing totalitarian state news agencies such as the PRC’s to dominate the democracies’ news media is the path to national suicide. Legislation, combined with the exposure and public shaming discussed previously, would help diminish (but never completely eliminate) the harm the PRC does through its insidious infiltration of the news media. Initially, simple steps can be taken, such as passing legislation that requires reciprocity pertaining to the news media, social media, and entertainment sectors. Legislation should be passed that states no PRC-affiliated entity or person should be allowed to buy or engage in any news media, business, education, or entertainment activities in the United States that U.S. citizens cannot do in the PRC. Legislation should also be passed that supports and encourages Chinese-language publications, social media, and broadcasts that counter PRC propaganda outlets globally.

Endnotes

- Portions of this article are extracted from Kerry K. Gershaneck’s forthcoming book to be published by Marine Corps University Press, Political Warfare: Strategies for Combating China’s Plan to “Win without Fighting.”

- Megan Eckstein, “Berger: Marines Focused on China in Developing New Way to Fight in the Pacific,” U.S. Naval Institute News, 2 October 2019.

- Eckstein, “Berger.”

- China Dream refers to a term promoted by Xi Jinping since 2013 that describes a set of personal and national ethos and ideals in China. Graham Allison, “What Xi Jinping Wants,” Atlantic, 31 May 2017.

- Steven W. Mosher, Hegemon: China’s Plan to Dominate Asia and the World (San Francisco, CA: Encounter Books, 2000), 1–2.

- The term Celestial Empire refers to a literary and poetic translation of tianchao or heavenly dynasty. Mosher, Hegemon, 3.

- Xi Jingping, “Secure a Decisive Victory in Building a Moderately Prosperous Society in All Respects and Strive for the Great Success of Socialism with Chinese Characteristics for a New Era” (speech, 19th National Congress of the Communist Party of China, Beijing, China, 18 October 2017).

- “China’s Intentions and Her Place in the World,” U.S. Naval Institute Blog (blog), 1 March 2010.

- Bill Birtles, “China’s President Xi Jinping Is Pushing a Marxist Revival—but How Communist Is It Really?,” Australia Broadcasting Corporation, 3 May 2018.

- Col Qiao Liang and Col Wang Xiangsui, Unrestricted Warfare (Beijing: PLA Literature and Arts Publishing House, 1999).

- David Gitter, Sandy Lu, and Brock Erdahl, “China Will Do Anything to Deflect Coronavirus Blame,” Foreign Policy, 30 March 2020.

- Michael Pillsbury, The Hundred-Year Marathon: China’s Secret Strategy to Replace America as the Global Superpower, 1st ed. (New York: Henry Holt, 2015).

- Pillsbury, The Hundred-Year Marathon, 16.

- China’s National Defense (Beijing: Information Office of the State Council of the People’s Republic of China, 1998).

- Fred McMahon, “China—World Freedom’s Greatest Threat,” Fraser Institute, 10 May 2019.

- Jonas Parello-Plesner and Belinda Li, The Chinese Communist Party’s Foreign Interference Operations: How the U.S. and Other Democracies Should Respond (Washington, DC: Hudson Institute, 2018).

- Kerry K. Gershaneck, discussions with senior PRC political warfare officers, Fu Hsing Kang Political Warfare College, National Defense University, Taipei, 2018.

- Tara Copp and Aaron Mehta, “New Defense Intelligence Assessment Warns China Nears Critical Military Milestone,” DefenseNews, 15 January 2019.

- China’s Global Naval Strategy and Expanding Force Structure: Pathway to Hegemony (17 May 2018) (testimony, Capt James E. Fanell, USN [Ret], House Permanent Select Committee on Intelligence); Nick Danby, “China’s Navy Looms Larger,” Harvard Political Review, 5 October 2019; and China can transition from a regional and technologically inadequate navy to one that is global, upgraded, and capable of multiple missions far from China’s ports. As the United States shows signs of wavering when it comes to defending its allied commitments in the Pacific or remain a pivotal power in the Indo-Pacific region, China is waiting to swoop in and fill the power vacuum the United States will inevitably leave open. As Sam Roggeveen at the Australian National University so aptly noted, “China is building a surface fleet not so much to challenge the United States as to inherit its position. Of course, China may help push the United States to cede such superpower responsibilities over time.” Liu Zhen, “China’s Latest Display of Military Might Suggests Its ‘Nuclear Triad’ Is Complete,” South China Morning Post (Hong Kong), 2 October 2019.

- Michael J. Pence, “Remarks by Vice President Pence on the Administration’s Policy Toward China” (speech, Hudson Institute, Washington, DC, 4 October 2018).

- Hearing on “The China Challenge, Part I: Economic Coercion as Statecraft,” 115th Cong. (24 July 2018) (prepared statement by Ely Ratner, vice president and director of studies, Center for a New American Security, Senate Foreign Relations Committee, United States House of Representatives), hereafter Ratner hearing.

- Uighurs are the Turkic-speaking people of interior Asia, who live primarily in northwestern China in the Uygur Autonomous Region of Xinjiang and a small number live in the Central Asian republics. “Up to One Million Detained in China’s Mass ‘Re-Education’ Drive,” Amnesty International, September 2018.

- “China’s Repressive Reach Is Growing,” Washington Post, 27 September 2019.

- Colm Keena, “China Cables: ‘The Largest Incarceration of a Minority since the Holocaust’,” Irish Times (Dublin), 24 November 2019.

- Arifa Akbar, “Mao’s Great Leap Forward ‘Killed 45 Million in Four Years’,” Independent, 17 September 2010.

- Ian Buruma, “The Tenacity of Chinese Communism,” New York Times, 28 September 2019; and Ian Johnson, “Who Killed More: Hitler, Stalin, or Mao?,” New York Review of Books, 5 February 2018.

- Johnson, “Who Killed More?”

- Laurence Brahm, “Nothing Will Stop China’s Progress,” China Daily (Beijing), 2 October 2019.

- Li Yuan, “China Masters Political Propaganda for the Instagram Age,” New York Times, 5 October 2019.

- Liu Chen, “US Should Stop Posing as a ‘Savior’,” PLA Daily, 27 September 2019; and Amy King, “Hurting the Feelings of the Chinese People,” Sources and Methods (blog), Wilson Center, 15 February 2017.

- “China Slams Use of Bringing up Human Rights Issues with Political Motives as ‘Immoral’,” Global Times, 12 December 2018; and Ben Blanchard, “China’s Top Paper Says Australian Media Reports Are Racist,” Reuters, 11 December 2017.

- “The Day the NBA Fluttered before China,” Washington Post, 7 October 2019.

- Amy Qin and Julie Creswell, “For Companies in China, Political Hazards Are Getting Harder to See,” New York Times, 8 October 2019.

- Ross Babbage, Winning without Fighting: Chinese and Russian Political Warfare Campaigns and How the West Can Prevail, vol. I (Washington, DC: Center for Strategic and Budgetary Assessments, 2019), 36.

- “Global Brands Better Stay Away from Politics,” Global Times, 7 October 2019.

- Bertil Lintner, “A Chinese War in Myanmar,” Asia Times (Hong Kong), 5 April 2017.

- Robert Taber, The War of the Flea: A Study of Guerrilla Warfare Theory and Practice (New York: Citadel Press, 1970).

- Yang Han and Wen Zongduo, “Belt and Road Reaches Out to the World,” China Daily (Beijing), 30 September 2019.

- Hearing on U.S. Policy in the Indo-Pacific Region: Hong Kong, Alliances and Partnerships, and Other Issues, 116th Cong. (18 September 2019) (statement, David Stilwell, assistant secretary of state for East Asian and Pacific Affairs).

- Pence, “Remarks by Vice President Pence on the Administration’s Policy Toward China.”

- Ratner hearing.

- John Garnaut, “Australia’s China Reset,” Monthly (Australia), August 2018; Didi Kirsten Tatlow, “Mapping China-in-Germany,” Sinopsis, 2 October 2019; Austin Doehler, “How China Challenges the EU in the Western Balkans,” Diplomat, 25 September 2019; Grant Newsham, “China ‘Political Warfare’ Targets US-Affiliated Pacific Islands,” Asia Times (Hong Kong), 5 August 2019; Derek Grossman et al., America’s Pacific Island Allies: The Freely Associated States and Chinese Influence (Santa Monica, CA: Rand, 2019), https://doi.org/10.7249/RR2973; C. Todd Lopez, “Southcom Commander: Foreign Powers Pose Security Concerns,” U.S. Southern Command, 4 October 2019; Andrew McCormick, “ ‘Even If You Don’t Think You Have a Relationship with China, China Has a Big Relationship with You’,” Columbia Journalism Review, 20 June 2019; and Heather A. Conley, “The Arctic Spring: Washington Is Sleeping Through Changes at the Top of the World,” Foreign Affairs, 24 September 2019.

- Tom Blackwell, “How China Uses Shadowy United Front as ‘Magic Weapon’ to Try to Extend Its Influence in Canada,” National Post (Canada), 28 January 2019; and Alexander Bowe, China’s Overseas United Front Work: Background and Implications for the United States (Washington, DC: U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission, 2018).

- Bill Gertz, “Chinese Military Engaged in Political Warfare Against the United States,” Washington Free Beacon, 22 October 2013.

- Gertz, “Chinese Military Engaged in Political Warfare Against the United States.”

- Mark Stokes and Russell Hsiao, The People’s Liberation Army General Political Department: Political Warfare with Chinese Characteristics (Arlington, VA: Project 2049 Institute, 2013), 24.

- Stokes and Hsiao, The People’s Liberation Army General Political Department, 24.

- Stokes and Hsiao, The People’s Liberation Army General Political Department, 24.

- Shirley A. Kan, U.S.-China Military Contacts: Issues for Congress (Washington, DC: Congressional Research Service, 2010), 33–34.

- Bill Owens, “America Must Start Treating China as a Friend,” Financial Times, 17 November 2009.

- Kan, U.S.-China Military Contacts, 33–34.

- Capt David L. O. Hayward, RAN (Ret), “The Sovereignty Dispute in the South China Sea, Economic Considerations for the Military & Economic Security of Australia” (lecture, Royal United Service Institute Queensland, Victoria Barracks, Brisbane, 13 September 2017).

- Garnaut, “Australia’s China Reset.”

- Babbage, Winning without Fighting, vol. I, 11–19.

- Bilahari Kausikan, “An Expose of How States Manipulate Other Countries’ Citizens,” Straits Times (Singapore), 1 July 2018.

- Kausikan, “An Expose of How States Manipulate Other Countries’ Citizens.”

- Sharp Power: Rising Authoritarian Influence (Washington, DC: National Endowment for Democracy, 2017).

- Babbage, Winning without Fighting, vol. I, 68.

- Parello-Plesner and Li, The Chinese Communist Party’s Foreign Interference Operations.

- Smart Competition: Adapting U.S. Strategy Toward China at 40 Years, 116th Cong. (8 May 2019) (statement of Aaron L. Freidberg, professor of politics and international affairs, Princeton University).

- Friedberg, Smart Competition.

- Parello-Plesner and Li, The Chinese Communist Party’s Foreign Interference Operations, 4.

- Stokes and Hsiao, PLA General Political Department Liaison Department, 41.

- Chris Buckley and Chris Horton, “Xi Jinping Warns Taiwan that Unification Is the Goal and Force Is an Option,” New York Times, 1 January 2019.

- Friedberg, Smart Competition.

- David Shambaugh, “China’s Soft-Power Push: The Search for Respect,” Foreign Affairs 94, no. 4 (July/August 2015).

- Anne-Marie Brady, “Exploit Every Rift: United Front Work Goes Global,” in David Gitter et al., Party Watch Annual Report, 2018 (Washington, DC: Center for Advanced China Research, 2018), 34–40.

- Thomas Lum et al., Comparing Global Influence: China’s and U.S. Diplomacy, Foreign Aid, Trade, and Investment in the Developing World (Washington, DC: Congressional Research Service, 2008), 7.

- Lum et al., Comparing Global Influence, 9.

- Lum et al., Comparing Global Influence, 10.

- Graeme Smith and Denghua Zhang, “China’s Blue Book of Oceania,” In Brief, no. 70 (2015).

- Smith and Zhang, “China’s Blue Book of Oceania.”

- Smith and Zhang, “China’s Blue Book of Oceania.”

- Babbage, Winning without Fighting, vol. I, 38–39.

- Peter Mattis, “An American Lens on China’s Interference and Influence Building Abroad,” Open Forum, Asan Forum, 30 April 2018.

- Mattis, “An American Lens on China’s Interference and Influence Building Abroad.”

- “Overseas Chinese Affairs Office of the State Council,” State Council, the People’s Republic of China, 12 September 2014.

- Alex Joske, “Reorganizing the United Front Work Department: New Structures for a New Era of Diaspora and Religious Affairs Work,” China Brief 19, no. 9 (May 2019).

- Bowe, China’s Overseas United Front Work, 8.

- Peter Mattis, “Contrasting China’s and Russia’s Influence Operations,” War on the Rocks, 16 January 2018.

- Stokes and Hsiao, The People’s Liberation Army General Political Department, 4.

- Parello-Plesner and Li, The Chinese Communist Party’s Foreign Interference Operations, 27.

- Babbage, Winning without Fighting, vol. I, 46–47.

- Cortez A. Cooper III, “China’s Military Is Ready for War: Everything You Need to Know,” National Interest, 18 August 2019.

- Mark A. Ryan, David Michael Finkelstein, and Michael A. McDevitt, eds., Chinese Warfighting: The PLA Experience since 1949 (Armonk, NY: M. E. Sharpe, 2003).

- Stokes and Hsiao, PLA General Political Department Liaison Department, 3, 15.

- Science of Military Strategy, 2013 (Beijing: Academy of Military Sciences, People’s Liberation Army of China, 2013); and Science of Military Strategy, 2015 (Beijing: National Defence University, 2015).

- Elsa Kania, “The PLA’s Latest Strategic Thinking on the Three Warfares,” China Brief 16, no. 13 (2016).

- Chris Kremidas-Courtney, “Hybrid Warfare: The Comprehensive Approach in the Offense,” Strategy International, 13 February 2019.

- Mahnken, Babbage, and Yoshihara, Countering Comprehensive Coercion, 20–21; and Kremidas-Courtney, “Hybrid Warfare.”

- Cooper, “China’s Military Is Ready for War.”

- David Ignatius, “China’s Hybrid Warfare against Taiwan,” Washington Post, 18 December 2018.

- Stokes and Hsiao, PLA General Political Department Liaison Department, 29.

- “PLA Eastern Theater Command Army SIGINT Operations Targeting Taiwan,” Taiwan Link (blog), 8 August 2016.

- John Costello and Joe McReynolds, China’s Strategic Support Force: A Force for a New Era, Center for the Study of Chinese Military Affairs, Institute for National Strategic Studies, China Strategic Perspectives, No. 13 (Washington, DC; National Defense University Press, 2018), 5.

- James E. Fanell and Kerry K. Gershaneck, “White Warships and Little Blue Men: The Looming ‘Short, Sharp War’ in the East China Sea over the Senkakus’,” Marine Corps University Journal 8, no. 2 (Fall 2017): 71–72, https://doi.org/10.21140/mcuj.2017080204.

- Fanell and Gershaneck, “White Warships and Little Blue Men,” 72.

- Bertil Lintner, “In a High-Stakes Dance, China Charms Bhutan,” Asia Times (Hong Kong), 31 July 2018.

- Fanell, China’s Global Naval Strategy and Expanding Force Structure.

- U.S. Responses to China’s Foreign Influence Operations, 115th Cong. (21 March 2018) (testimony by Peter Mattis before the House Committee on Foreign Affairs, Subcommittee on Asia and the Pacific); Babbage, Winning without Fighting, vol. I, 79–83; and Parello-Plesner and Li, The Chinese Communist Party’s Foreign Interference Operations, 46–49.

- Babbage, Winning without Fighting, vol. I.