PRINTER FRIENDLY PDF

EPUB

AUDIOBOOK

Abstract: Large swaths of the U.S. Marine Corps’ history have yet to be entirely understood by scholars and Marines alike. A considerable gap in knowledge exists pertaining to the usage of the emblem used on the buttons of the Marine Corps’ service alpha and dress blue uniforms today. Many confuse this device of an eagle, fouled anchor, and 13 stars for the Corps’ famed Eagle, Globe, and Anchor (EGA) emblem, which was commissioned in 1868 by Commandant General Jacob Zeilin, nearly five decades after the button insignia made its first appearance. The history of the Marine button emblem is closely tied to the Corps’ naval heritage. This research illuminates its origins, shedding light on a previously obscured, yet salient, chapter in Marine Corps history.

Keywords: Marine Corps emblem, Dr. Theodore F. Marburg, Aaron Merrill Peasley, uniform buttons, naval history, War of 1812, Archibald Henderson

Introduction

A considerable gap in knowledge exists pertaining to the creation of the device bearing an eagle, fouled anchor, and 13 stars that is used on the buttons of the U.S. Marine Corps’ service alpha and dress blue uniforms. Many confuse this image of a bald eagle clutching a fouled anchor and topped by an arc of 13 stars, for the Corps’ more widely used Eagle, Globe, and Anchor (EGA) emblem, which was commissioned in 1868 by General Jacob Zeilin, the seventh Commandant of the Marine Corps. The button emblem made its first appearance nearly five decades earlier, and its history is closely tied to the Corps’ naval heritage. This research illuminates its origins, ultimately shedding light on a previously obscured, yet salient, chapter in Marine Corps history.

The Marine Corps’ uniform button emblem is one of the oldest used by any U.S. Service branch to date, but the history behind its creation has been obscure. Through primary source and archival research, this emblem’s beginnings can be revealed, as well as the identities of its earliest confirmed commissioner and manufacturer. This article traces the emblem’s origin back to the Charlestown Naval Yard in Massachusetts, the birthplace of the U.S. Navy’s first commissioned ship of the line, the USS Independence (1776), and to die-sinker Aaron Merrill Peasley, who was possibly responsible for designing the Corps’ first emblem for uniform buttons. Peasley may also have been the first person to die-sink the emblem, which is still used—in an updated form—on Marines’ service alpha and dress blue uniforms.

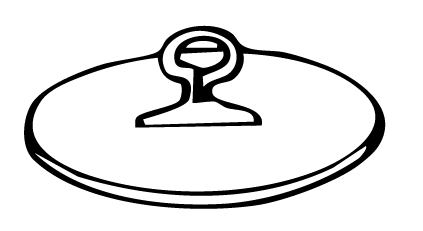

Figure 1. This is an example of the modern Marine Corps button currently used on Marine Corps dress uniforms.

Author's personal collection.

What’s in a Button

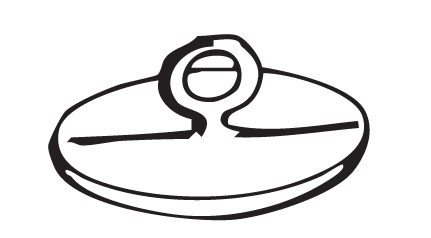

The button to which the eagle, fouled anchor, and 13 stars were first applied is classified as a stamped one-piece brass button with an omega shank.[1] A stamped button used a blank manufactured button onto the front and/or back of which the maker die-sank a design. There are also early examples showing buttons being used with preexisting designs from multiple different agencies in the government. One-piece buttons resemble a flat disc, like a planchet used in coin-making. These planchets would have most likely come from England during the period of the Marine emblem’s inception, as it was cheaper and the United States at this time lacked both the tradesmen and the technological capability to make high-quality buttons, unlike England.[2] However, the records do not indicate that it was cheaper to have the buttons die-sunk in England.[3] The omega shank, so-called because it resembled an omega symbol, required a stronger wiring that would be able to withstand harsh conditions such as those at sea. Shanks used would vary by tradesman, but typically each die-sinker had a preferred type of shank and button they would use. One other example of buttons during this time are cast buttons, which are cast from molds and have a distinct line on the back of the button when the button was taken out of the mold. There are two-piece and three-piece buttons; however, due to technological limitations, these were not manufactured until a later period and were introduced well after the Marine Corps uniform regulations of 1821, which will be explained later.

Figure 2. (Left) An example of a one-piece button with an omega shank.

Figure 3. (Right) An example of a one-piece cast button.

Digital Archaeological Archive of Comparative Slavery, adapted by MCUP.

The profession of a die-sinker, now long phased out by modern technology, was a profession that took years to master, and during the early nineteenth century the United States had very few individuals with this skill set. Die-sinkers were paid very well and were hard to come by, as shown through early correspondence from the button and sewing hardware firm Scovill Manufacturing Company.[4]

Early in the nineteenth century, the uniforms worn by U.S. Navy personnel were slowly developing their own personality. This article will but brush the surface of early uniforms of the U.S. Navy and concentrate on the buttons worn on naval uniforms according to the Naval Uniform Regulations from 1798 to 1821.

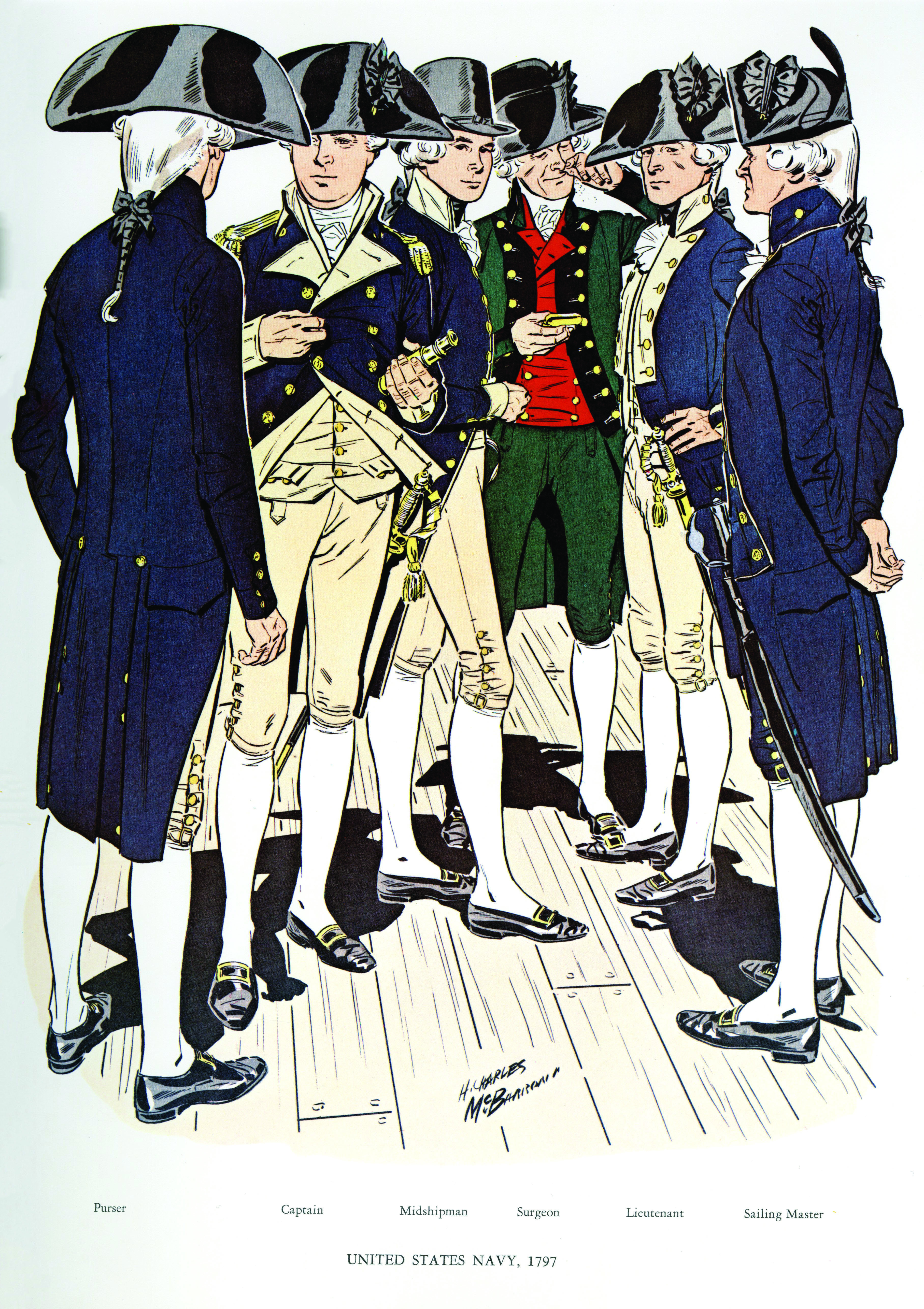

Figure 4. The 1797 U.S. naval uniforms (from left to right): purser, captain, midshipman, surgeon, lieutenant, and sailing master.

Courtesy of Naval History and Heritage Command.

Figure 5. U.S. naval officers and seamen, dress uniforms, 1812–15.

Courtesy Naval History and Heritage Command.

Who Were Buttons Made For?

Following the Act Establishing the Navy and Act for Establishing and Organizing a Marine Corps in April and July 1798, respectively, the Marine Corps and Navy were created to be technically separate entities, however their uniforms were effectively the same with minor differences.[5] The emblems used on their buttons came from the 1798 Navy Uniform Regulations pertaining to the dress uniform for Navy officers. According to Edwin N. McClellan’s Uniforms of the American Marines, the original buttons were composed of a “yellow metal eagle, with shield on left wing, enclosing a foul [sic] anchor.”[6] This pattern would be changed in 1802 to “the buttons of yellow metal, with the foul [sic] anchor and American eagle, surrounded with fifteen stars.”[7] The latter would also be reiterated in the Navy Uniform Regulations of 1814 and would hold true in the Navy Uniform Regulations until 1821, when a clear distinction between Navy and Marine buttons was stated.

Fifth Commandant of the Marine Corps Archibald Henderson ensured the uniformity of his Marines was included on the proposal for uniform regulations the Navy published in May 1821. This was the first time the term Marine button was used under the officers undress uniform section in a proposal to the secretary of the Navy, dated 15 May 1821.[8] Under the Naval General Orders established 10 May 1820, it is stated “the buttons are to be as described in the drawing No. 1,” but unfortunately, no drawings have been found pertaining to this statement.[9] However, a button pattern book from an English button manufacturer in 1826 shows U.S. Navy buttons numbered one through five, showing the patterns made by the manufacturer.[10] There may also be a more direct connection between then-captain Henderson and the Marine Corps button emblem; it is possible that Henderson commissioned it, as he was stationed in the Charleston, Massachusetts, naval yard from September 1812 to August 1813 and he was the Commandant who standardized the Corps’ uniforms in 1821, using the emblem under discussion here.[11] This cannot be proven with current primary sources available and is only circumstantial at this point in the author’s research.

Until 1821, both officer and enlisted Marine uniforms used Navy buttons. Enlisted Marine uniforms used Navy buttons until the 1830s. Because officer uniform buttons were purchased independently, these Marines had a choice in where to obtain their buttons. Figure 6 (see p. 10) shows an example of a button bearing the typical naval button emblem—an eagle holding a shield bearing the fouled anchor, which was commonly worn by Marine officers. The bald eagle has been a staple of U.S. heraldry since its use in 1782 on the Great Seal of the United States of America.[12] The 15 stars incorporated in this design pertain to U.S. naval regulations of 1802, however in 1804 the United States encompassed 17 states.[13] It is not known why this specific number of stars was selected, but it can be surmised for later examples to include 13 stars for the original 13 colonies. The shield the eagle holds most likely represents protection while the anchor symbolizes naval heritage and maritime history.

The button shown in figure 11 (see p. 12), which bears the device of an eagle, fouled anchor, and 13 stars along with Peasley’s backmark, is currently the oldest known example of the Marine Corps emblem. It was found in an isolated area on land that was once owned by the Vernon family in the greater Oyster Bay, New York, area until the land was sold in 1834. The Vernons were a prominent family in the area and have several War of 1812 connections, including family member James Vernon, who fought for a New York militia out of Brooklyn, New York.[14] U.S. Navy surgeon’s mate Samuel Vernon, who served from 11 January 1812 until 5 February 1814, served on board the USS United States (1797) during the War of 1812 under legendary captain Stephen Decatur, known to have been docked in the Charleston Navy Yard July – October 1813 and in the New York Navy Yard in December 1813 after the United States’s victory over HMS Macedonian. Vernon was from Middlesex, New Jersey; family ties are still being established between these two Vernon families.[15] Whether this button found on the Vernon property was worn by Samuel Vernon is still unclear, however the implications of a U.S. Navy surgeon’s mate possessing a button stamped with the earliest known Marine Corps emblem is something that would need to be covered separately from this publication.

Variations to Navy buttons can be observed in the leading books on military buttons, such as Record of American Uniform and Historical Buttons by Alphaeus H. Albert; Uniform Buttons of the United States: Button Makers of the United States, 1776–1865, Button Suppliers to the Confederate States, 1800–1865, Antebellum and Civil War Buttons of U.S. Forces, Confederate Buttons, Uniform Buttons of the Various States, 1776–1865 by Warren K. Tice; The Emilio Collection of Military Buttons: American, British, French And Spanish, with Some of Other Countries, and Non-Military by Luis Fenollosa Emilio; and American Military Buttons: An Interpretive Study—The Early Years, 1785–1835 by Bruce S. Bazelon and William Leigh.[16] Coincidently Bazelon and Leigh’s interpretative study was published while the author researched this article and now is the leading book on early United States buttons. Coupled with modern technology, many military buttons can be found online through auction websites such as eBay or Auction Zip and compared to buttons in these books. With the variations presented in these books, the differences can be observed in the interpretation of the uniform regulations and general orders from the producers of the era.

Aaron Merrill Peasley

Aaron Merrill Peasley (also spelled Peaslee, 2 July 1775–6 April 1837) was born in Hanover, New Hampshire, and he first appears to have worked as an engraver in Newburyport, Massachusetts, in 1802.[17] He is credited with multiple engravings, including A Plan of the Town of Exeter and A Plan of the Compact Part of the Town of Exeter both in 1802.[18] Peasley also created multiple engravings for the book The American Coast Pilot by Edmund M. Blunt and Captain Lawrence Furlong in 1804 and an engraving of French religious figure Jacques Saurin and a patent corn sheller.[19] In the spring of 1804, Peasley was arrested in Newburyport and convicted in Ipswich, Massachusetts, for the possession of counterfeit bank notes made for the Beverly Bank and the possession of tools to make counterfeit silver coins. He was sentenced to five years in jail and to hard labor, but as a follow-on sentence, he would serve another five years if he did not pay restitution for his crime.[20]

During Peasley’s incarceration, he was moved to the Charlestown State Prison, located just north of Boston, due to overcrowding at the jail where he was initially imprisoned.[21] Despite a possible sentence of up to 10 years in jail and hard labor, Peasley submitted multiple petitions for an early release because of his reformation in prison, claiming to be “seduced to be an instrument” to forge the counterfeit bank note plates.[22] Peasley was pardoned 8 March 1808 and shortly thereafter began using his talents with metal to great effect in the greater Boston area.[23]

As a die-sinker, Peasley was able to shape steel into a die by softening it and carving a design into its surface before hardening it again.[24] This skillset was highly sought after, to the extent that even as a convicted felon Peasley was able to establish multiple contracts with the U.S. government only four years after being released from prison. Peasley manufactured buttons for multiple government agencies, one of which was the Corps of Artificers, only an active unit from April 1812 to 1815.[25] These dates establish that Peasley made buttons as early as 1812, confirmed through his backmark of the Corps of Artificers unit; they also assist in narrowing the time frame of the creation of the Marine Corps button emblem’s specific design. Primary-source research into Peasley’s background and timeline is corroborated through the archives of the Boston Directory and archived Boston property records. Located in the Boston Athenaeum, an institution for literary and scientific study, the directory reveals that Peasley was working in the Boston area from 1810 (under the name spelling of Peasly) to 1823 and that in the year 1816 he is classified as a die-sinker.[26]

Figure 6. NA 45v backmark “***U.S.*** MARINE.”

Author’s personal collection.

Figure 7. NA 57D, backmark “A. M. PEASLEY / BOSTON.”

Author’s personal collection.

The Details in the Buttons

It has been established that Peasley was an early American die-sinker of one-piece buttons in the Boston area. However, to substantiate that he is indeed responsible for manufacturing the earliest known Marine Corps buttons bearing the aforementioned emblem, the elements of which still form the basis of the device found on Marine buttons today, we must first explore his unique style and works. Peasley leveraged a distinct approach when designing dies for his Marine Corps emblem, but the easiest way to differentiate his from those made by all later and similar personnel manufacturing Marine Corps buttons is the rope found at the bottom of the button, stemming off the anchor. Peasley’s rope follows the curve of the button’s edge; no other producer of Marine Corps buttons used this distinctive design element, as will be shown through examining examples by his competitors.

Figure 8. NA 66 backmark “A. M. PEASLEY / BOSTON.”

Author’s personal collection.

Figure 9. An example of a Corps of Artificers button, with the backmark “* A.M. PEASLEY * * BOSTON.”

Courtesy of William Leigh Collection.

Figures 10 through 19 all share the designation MC, letters that are used as classification markers in Alphaeus H. Albert’s book Record of American Uniform and Historical Buttons, first published in 1969, and are still employed today.[27] Despite each of these buttons having different backmarks, each button shares a near-identical front die strike. The dies used would have been made by hand, meaning that despite slight differences, the same die-sinker made them.[28] Theodore F. Marburg discussed the reasoning behind using different backmarks in the National Button Society’s quarterly publication in 1946. He attested that the reason for the different backmarks was due to the pricing of the buttons and advertisement for the business. If a button were to have two different dies made, it would require more funding.[29] The buttons in figures 10 and 12 marked CLAPP AND NICHOLS TAILORS BOSTON / A.M.P. / D.S. and C. NEWMAN TAILOR (Charles Newman, proprietor) would have simply cost more and could have been the earlier works of Peasley’s die-sinking career. This is surmised due to Peasley establishing connections within Boston. Being recently released from prison would have required him to seek work through different modes of employment. The tailors in this period did not have the capability to die-sink buttons, but working with tailors would have allowed him to start building connections with military personnel, advertised his work through the tailor’s business, and provided a steady income stream. No other (later) examples of Peasley’s buttons indicate that he worked with any other tailors after establishing himself as a superior die-sinker.

Figure 10. An MC 3 type button with the backmark “CLAPP AND NICHOLS TAILORS BOSTON / A.M.P. / D.S.”

Author’s personal collection.

Figure 11. An MC 3 type button with the backmark “NE PLUS ULTRA / TREBLE GILT / STANDD COLR.”

Author’s personal collection.

Figure 12. An MC 1 type button with the backmark “C. NEWMAN TAYLOR.” This backmark is not listed in Alphaeus Albert’s book.

Courtesy of William Leigh Collection.

Figure 13. An MC 3 type button with the backmark “EXTRA RICH ORANGE.”

Courtesy of Bruce S. Bazelon collection.

Figure 14. An MC 1 type button with the backmark “A M Peasley / Boston.”

Courtesy of William Leigh collection.

Figure 15. An MC 3 type button with the backmark “WISE / BIEBLY HYDE & CO / NO 5 / EXTRA FINE.”

Courtesy of Bruce S. Bazelon collection.

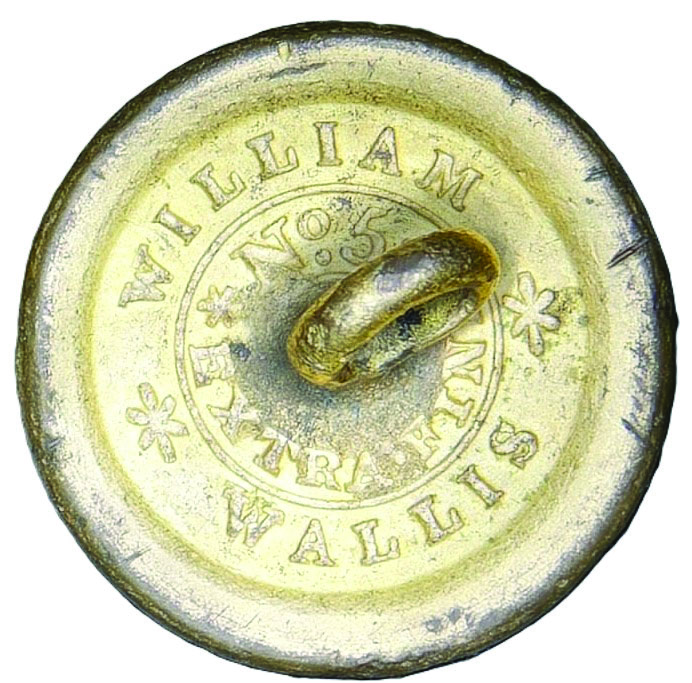

Figure 16. Two MC 3 type buttons, front and back, with the backmark “*WILLIAM WALLIS * / *No 5 * EXTRA FINE.” The left button measures 22.4 mm, and the right button measures 16.2 mm.

Courtesy of William Leigh collection.

The only known instances of D.S. being used on the back of Peasley’s buttons are on those marked CLAPP AND NICHOLS TAILORS BOSTON / A.M.P. / D.S. and on the Corps of Artificers buttons (dating to 1812–15). It can be determined by an entry in the Boston Directory that Charles Nichols and Chester Clapp (entered as Clap and Nichols, tailors) were documented as business partners as early as 1806, but they were no longer in business together after April 1818, when their “Copartnership Dissolved.”[30] Despite this still predating the 1821 Naval Uniform Regulations and establishing a no-later-than date of April 1818 for the Clapp and Nichols button presented in figure 11, newspaper advertisements for Clapp and Nichols Tailors indicate that they employed Peasley in August 1811 by the inclusion of the statement “gilt plated, and steel Buttons: Infantry and Navy,” rather than just “plated and gilt Buttons.”[31] Clapp and Nichols Tailors stopped advertising “bullet, gilt and plated, artillery, navy and engineer Buttons” between September 1815 and January 1816.[32] At no point were Marine buttons promoted in Clapp and Nichols’s advertising.

The last element to be considered is the role of other stakeholders in the fabrication process. Tailors as well as naval agents played critical functions in the acquisition of these buttons. Merchandise was procured by the U.S. Navy and Marine Corps in the early 1800s through naval agents located at U.S. naval ports.[33] An example of this agreement can be found in Uniforms of the American Marines, 1775 to 1829, in which correspondence between third Commandant of the Marine Corps Lieutenant Colonel Franklin Wharton and Philadelphia naval agent George Harrison were transcribed by Major Edwin N. McClellan. Harrison wrote,

October 12, 1804 (Enlisted Men): As Armitage’s Die is won out & he is about to have another executed, he wishes your order as to the Button you will prefer. I enclose his patterns for your selection, which return (thro same medium) pr [sic] return of mail. He is of the opinion that you had better do away’ the stars and have an Anchor on the Button.[34]

Lieutenant Colonel Wharton responded,

October 19, 1804 (Enlisted Men): “It will be out my department to make an alteration in the buttons. I therefore return to Mr. Armitage the card. *** Please order them to be of the former pattern *** black cloth for gaiters*** brown linen *** white common buttons *** large common buttons.”[35]

This interaction between Harrison and Wharton establishes the relationship between a naval agent and the Commandant of the Marine Corps in 1804. Despite this conversation focusing on buttons and on George Armitage, the sole provider of enlisted buttons to the Marine Corps at that time, it does not shed more light on the emblem in question. It may, however, be surmised that Peasley most likely had a relationship with the naval agent during this time, although it does not establish Peasley as the designer of the emblem. Due to naval officers being required to purchase their own uniform items, the naval agent, Amos Binney or Francis Johnnot depending on the inception date of the Marine Corps emblem, would have most likely directed the naval officers to appropriate tailors, in this case either Clapp and Nichols or Newman.[36] Eventually Peasley established personal connections with the officers and no longer had to work with tailors, so he was able to use his own backmarks, such as A.M. PEASLEY / BOSTON (see figure 8).

Peasley used a variety of backmarks on his buttons, which indicates that he did not make the Marine Corps buttons for a single client but for at most six different people. The Marine button will be explored later, but the stipulation for size and slight variations in design are a result of the vagueness in uniform regulations and indicate different orders placed by different Marines or sailors. For example, out of the surviving Navy and Marine Corps one-piece brass buttons cataloged, the vast majority vary between 21 millimeters to 24 millimeters in diameter, however, one example of Peasley’s MC 1 button measures 25 millimeters in diameter. This size difference could indicate different orders were made to accommodate different servicemembers and their different uniforms.

Figure 17. An MC 4 type button with the backmark “LEWIS & TOMES • EXTRA RICH • NO 5.”

Courtesy of William Leigh collection.

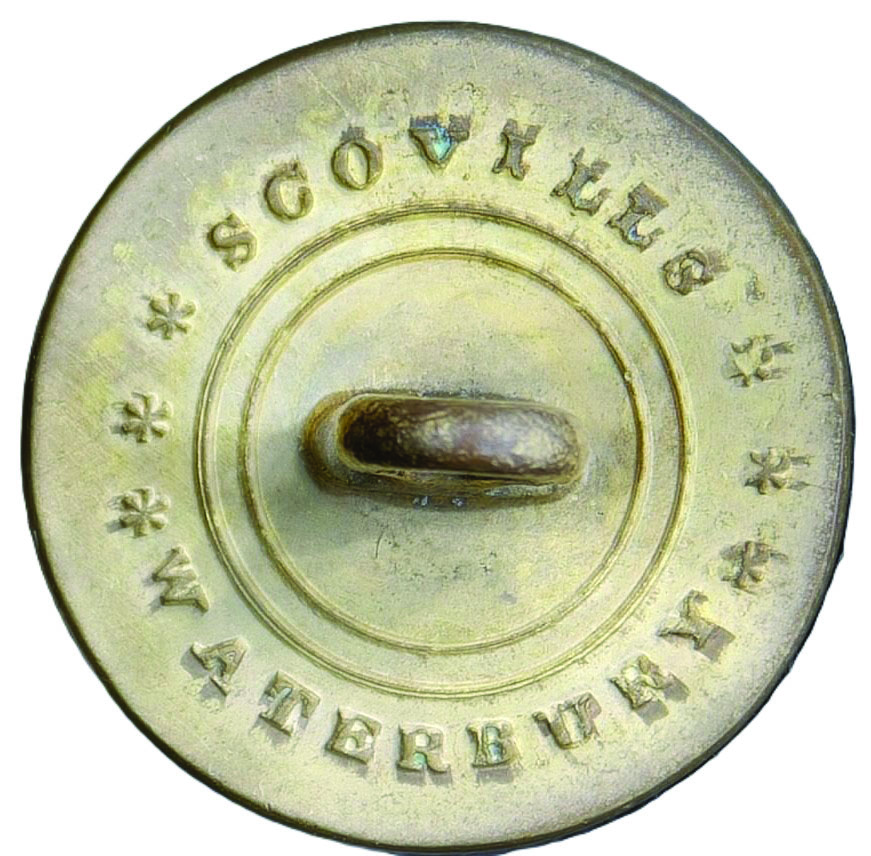

Figure 18. An MC 5A type button, front and back, backmarked “***SCOVILLS*** / WATERBURY,” measuring 20.4 mm, and an MC 5Av button, front and back, backmarked “<<SCOVILLS>><<EXTRA>>,” measuring 15.7 mm.

Courtesy of William Leigh collection.

Figure 19. An MC 4 type button backmarked “CHARLES JENNENS • LONDON•.”

Courtesy of Bruce S. Bazelon collection.

Ruling Out the Competition

Examining other manufacturers of early one-piece Marine Corps buttons during this period rules out other possibilities for the earliest confirmed manufacturer of Marine Corps buttons. The works of Albert, Tice, Emilio, and Bazelon and Leigh demonstrate examples of military brass buttons ranging from revolutionary to modern times. In addition, Marburg’s research on economies and methodologies of early brass button production reveals the scarcity of die-sinkers, and Marine Corps muster roll sheets show how few Marine Corps officers were in the Corps at this time. Through these sources and others, at this time, it can be concluded that there were only seven verifiable producers of the first Marine Corps emblem onto one-piece brass buttons during this period. Along with Peasley, these producers were Wise, Bielby, Hyde and Company, using the backmark WISE / BIEBLY HYDE & CO / NO 5 / EXTRA FINE (MC 3A); William Wallis, backmark WILLIAM * WALLIS * / No 5 * EXTRA FINE * (MC 3A); Lewis and Tomes, backmark LEWIS & TOMES / EXTRA RICH / No 5 (MC 3A); Charles Jennens, backmark CHARLES JENNENS / LONDON (MC 4); W. R. Smith, backmark W. & R. SMITH TREBLE GILT (MC 4); and Scovill Manufacturing Company, backmark ***SCOVILLS***/ WATERBURY (MC 5).

The timeline of each producer closely aligns to the same general period Peasley was die-sinking his own buttons, but through the backmarks, location of producers, and designs used, it can be determined that each of the manufacturers above designed and produced their buttons after Peasley.

The manufacturers Wise, Bielby, Hyde and Company (operating around 1818), William Wallis (operating late 1790s to late 1820s), and Lewis and Tomes (operating 1816–33) all have No. 5 incorporated into their backmarks, indicating these buttons were made after the Naval General Order of 10 May 1820.[37] This seemingly minute detail is relevant because these uniform regulations enforced each button to have a designation of 1 through 4. Consequently, an amendment would have had to be adopted for the Marine Corps buttons produced during the period of inquiry by any of these makers to have a No. 5 designation. This amendment has been theorized by lead researchers of early U.S. military emblems.[38]

As stated in Marburg’s writings for the National Button Society Quarterly Bulletin, Scovill Manufacturing Company did not officially make Marine Corps buttons until 1832 for commercial purchases. Scovill Manufacturing has an extremely rich history, which Marburg employed via the Scovill archives to write an unpublished dissertation on the economics of early brass button-making and the four articles published in the National Button Society Quarterly Bulletin in 1946. Marburg’s work was invaluable for this author’s research and also provides a detailed insight into the beginnings of one of America’s greatest button manufacturers, the Scovill Manufacturing Company.[39]

Charles Jennens, in business from 1805 to 1844, and W. R. Smith, operating from 1790 to 1831, both were London-based button makers, disqualifying them as the makers of the earliest buttons made for the U.S. Marine Corps. Relations with Great Britain were strained during this period, with the Embargo Act of 1807 affecting trade, despite its ending with the Non-Intercourse Act in March 1809.[40] The relations between Great Britain and the United States became so strained that they sparked the War of 1812, which ended on 24 December 1814 with the Treaty of Ghent.[41] U.S.-British relations would have taken time to repair, making it unlikely that London-based businesses, including die-sinkers, would manufacture buttons for a U.S. Service branch long after the war ended. Furthermore, records do not indicate it was cost-effective to have the buttons die-sunk in London, but it was cost-effective to have plain gilt buttons shipped to the United States and then die-sunk by local crafters. This was also discussed in Marburg’s articles in the National Button Society Quarterly Bulletin.[42]

Conclusion

Something as simple as a button can possess a complex history that illuminates aspects of broader U.S. and Marine Corps history and heritage. This research finds that Aaron M. Peasley was responsible for producing the earliest confirmed Marine Corps uniform button emblem, which is still being used today in an updated style. For roughly 200 years, Peasley’s contribution to the Marine Corps was unrecognized. His impact on the Marine Corps, though not one of doctrine or battles fought, still survives and his work centuries ago should be understood and credited in the twenty-first century.

Endnotes

[1] Jennifer Aultman and Kate Grillo, “DAACS Cataloging Manual: Buttons,” PDF, DAACS Digital Archaeological Archive of Comparative Slavery, June 2018; and Alphaeus H. Albert, Record of American Uniform and Historical Buttons, 6th ed. (Boyertown, PA: Boyertown Publishing, 1977), 7.

[2] Marburg, “Brass Button Making, 1802–1852. Part I, The Early History of the Scovill Enterprise,” National Button Society Quarterly Bulletin 5, no. 1 (January 1946): 19–34.

[3] Marburg, “Brass Button Making, 1802–1852. Part I, The Early History of the Scovill Enterprise,” 19–34.

[4] Theodore F. Marburg, “Button Making at the Scovill Enterprise 1802–1852, Part III, Casting, Rolling, and Stamping,” National Button Society Quarterly Bulletin 5, no. 3 (July 1946): 159–74.

[5] An Act to Establish an Executive Department to Be Denominated the Department of the Navy, 30 April 1798, Chap. 35, Congressional Record, 5th Cong., 2d Sess., 553–54; and An Act for the Establishing and Organizing a Marine Corps, 11 July 1798, Chap. 72, Congressional Record, 5th Cong., 2d Sess., 594–95.

[6] Maj Edwin North McClellan, Uniforms of the American Marines, 1775 to 1829 (Washington, DC: History and Museums Division, Headquarters Marine Corps, 1982), 6.

[7] R. Smith, “Uniform Regulations, 1802,” Naval History and Heritage Command, 23 August 2017.

[8] McClellan, Uniforms of the American Marines, 1775 to 1829, 74.

[9] Naval General Order: Navy Uniform (Washington, DC: Office of the Secretary of the Navy, 10 May 1820).

[10] Bruce S. Bazelon and William Leigh, American Military Buttons: An Interpretive Study—The Early Years, 1785–1835 (Woonsocket, RI: Mowbray Publishing, 2024), 74.

[11] Detachment of Marines, Charlestown, MA, Navy Yard muster roll (Mroll), September 1812, United States Muster Rolls of the Marine Corps, 1798–1937, Roll 3 1810 January–1812 December, FamilySearch.org, image 593 of 707; Detachment of Marines, Charlestown, MA, Navy Yard MRoll, August 1813, United States Muster Rolls of the Marine Corps, 1798–1937, Roll 4 1813 January–1814 June, FamilySearch.org, image 212 of 503; and McClellan, Uniforms of the American Marines, 1775 to 1829, 69–74.

[12] “The Great Seal,” National Museum of American Diplomacy, U.S. Department of State, 19 March 2018.

[13] Smith, “Uniform Regulations, 1802.”

[14] War of 1812 Survivor’s Pension certificate of James Vernon, Department of the Interior, 6 November 1871, author’s personal collection; and Edward W. Callahan, ed., List of Officers of the Navy of the United States and of the Marine Corps from 1775 to 1900 (New York: L. R. Hammersly, 1901), 560.

[15] Edgar Stanton Maclay, A History of the United States Navy, from 1775 to 1898, vol. 12 (New York: D. Appleton, 1898), 389; and Samuel Vernon to Paul Hamilton, secretary of the Navy, 12 January 1812, Record Group 45, Naval Records Collection of the Office of Naval Records and Library, Letters Received Accepting Appointments as Midshipmen, 1809–39, Entry 122-I18, National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, DC.

[16] Albert, Record of American Uniform and Historical Buttons; Warren K. Tice, Uniform Buttons of the United States: Button Makers of the United States, 1776–1865, Button Suppliers to the Confederate States, 1800–1865, Antebellum and Civil War Buttons of U.S. Forces, Confederate Buttons, Uniform Buttons of the Various States, 1776–1865 (Gettysburg, PA: Thomas Publications, 1997); Luis Fenollosa Emilio, The Emilio Collection of Military Buttons: American, British, French and Spanish, with Some of the Other Countries, and Non-Military in the Museum of the Essex Institute, Salem, Massachusetts (Salem, MA: Essex Institute, 1911); and Bazelon and Leigh, American Military Buttons.

[17] Aaron Peaslee, New Hampshire Birth Records, Early to 1900, database, FamilySearch.org, 21 October 2022.

[18] P. Merrill, A Plan of the Compact Part of the Town of Exeter at the Head of the Southerly Branch of Piscataqua River, Newburyport, Massachusetts: A. Peasley, 1802.

[19] Lawrence Furlong, The American Coast Pilot Containing the Courses and Distances Between the Principal Harbours, Capes and Headlands, from Passamaquoddy, Through the Gulf of Florida: With Directions for Sailing into the same, Describing the Soundings, Bearings of the Light-Houses and Beacons from the Rocks, Shoals, Ledges, &c.: Together with the Courses and Distances from Cape Cod and Cape Ann to Georges’ Bank, Through the South and East Channels, and the Setting of the Currents with Latitudes and Longitudes of the Principal Harbours on the Coast, Together with a Tide Table, 4th ed. (Newburyport, MA: Edmund M. Blunt, 1804), 135, 136, 141, 143, 152, 168, 177, 182, 186; and A. M. Peasley, Jacques Saurin, nineteenth century, line and stipple engraving on cream laid paper, Worcester Art Museum Charles E. Goodspeed Collection, Worcester, MA.

[20] A. Haswell, “More Money Makers,” Vermont Gazette 2d ed., no. 6 (8 May 1804): 3; and Commonwealth vs. Peaslie [sic] for Making a Plate for Counterfeiting Bank Notes and for Being Posessed of Tools for Counterfeiting Money, April Term, 1804, Court Records 1802–1805, Essex County Court House, Salem, MA, 258–60, MSSC 4, roll no. 2123, via FamilySearch.org.

[21] Intake entry for Aaron Peasley, 3 May 1804, HS9.01/series 285X, Daily Reports, Charlestown State Prison, Charlestown, MA.

[22] Early release petitions and pardon and discharge proclamation of A. Peasley, Commonwealth of Massachusetts, 8 March 1808, GC3/series 328, Council Pardon Files, box 3, Massachusetts Archives, Boston, MA, hereafter Peasley pardon proclamation.

[23] Peasley pardon proclamation.

[24] Marburg, “Button Making at the Scovill Enterprise 1802–1852, Part III, Casting, Rolling, and Stamping,” 159–74.

[25] Capt Oscar F. Long, “The Quartermaster’s Department,” in The Army of the United States: Historical Sketches of Staff and Line with Portraits of Generals-in-Chief, ed. Theo. F. Rodenbough and William L. Haskin (New York: Maynard, Merrill, 1896), 38–66; and William F. McGuinn and Bruce S. Bazelon, American Military Button Makers and Dealers; Their Backmarks and Dates, 2d ed. (Chelsea, MI: BookCrafters, 1988).

[26] The Boston Directory (Boston, MA: Edward Cotton, 1810), 153; The Boston Directory (Boston, MA: E. Cotton, 1816), 170; and The Boston Directory (Boston, MA: C. Stimpson Jr. and J. H. A. Frost, 1823), 180.

[27] Albert, Record of American Uniform and Historical Buttons, 109.

[28] Bazelon and Leigh, American Military Buttons, ix.

[29] Marburg, “Button Making at the Scovill Enterprise 1802–1852, Part III, Casting, Rolling, and Stamping,” 159–74.

[30] The Boston Directory (Boston, MA: Edward Cotton, 1806), 32; and “Copartnership Dissolved,” Boston (MA) Daily Advertiser, 16 May 1818, Genealogy Bank, 2.

[31] Advertisement for Clapp and Nichols, Tailors, Boston (MA) Patriot, 6 October 1810, Genealogy Bank, 4; and Advertisement for Clapp and Nichols, Tailors, Boston (MA) Patriot, 31 August 1811, Genealogy Bank, 4.

[32] Advertisement for Clapp and Nichols, Tailors, Boston (MA) Daily Advertiser, 11 September 1815, GenealogyBank, 3; and Advertisement for Clapp and Nichols, Tailors, Boston (MA) Daily Advertiser, GenealogyBank, 22 January 1816, 4.

[33] Robert G. Albion, “Brief History of Civilian Personnel in the US Navy Department,” Naval History and Heritage Command, 23 August 2017.

[34] McClellan, Uniforms of the American Marines, 1775 to 1829, 32.

[35] McClellan, Uniforms of the American Marines, 1775 to 1829, 32.

[36] Edwin C. Bearss, Historic Resource Study, Charlestown Navy Yard 1800–1842, vol. 1 (Boston, MA: U.S. Department of the Interior, 1984), 55, 95.

[37] Naval General Order: Navy Uniform.

[38] LtCol Robert Milburn, USA (Ret), text message interview with author, 22 May 2023.

[39] Marburg, “Button Making at the Scovill Enterprise 1802–1852, Part II, The Varieties of Buttons,” National Button Society Quarterly Bulletin 5, no. 2 (April 1946): 89–107.

[40] Bill no. 26, in Acts Passed at the First Session of the Tenth Congress (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1808), 1–11; Bruce S. Bazelon and William F. McGuinn, A Directory of American Military Goods Dealers and Makers, 1785–1915 (Woonsocket, RI: Andrew Mowbray Publishing, 2006), 67, 199; Albert, Record of American Uniform and Historical Buttons, 110; and Bill no. 26, in Acts Passed at the First Session of the Tenth Congress (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1810), 520–524.

[41] Treaty of Ghent, 24 December 1814, Perfected Treaties, 1778–1945, General Records of the United States Government, Record Group 11, National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, DC.

[42] Marburg, “Brass Button Making at the Scovill Enterprise, 1802–1852. Part II, The Varieties of Buttons,” 159–74.

About the Author

2dLt Kevin Rosentreter holds a bachelor of arts in history, a certificate in Arabic studies from Arizona State University in Tempe, AZ, and has been active-duty in the U.S. Marine Corps since July 2009.

https://orcid .org/0009-0008-2340-2172