PRINTER FRIENDLY PDF

EPUB

AUDIOBOOK

Abstract: During World War II, the military dog became synonymous with patriotism and a symbol of the fight for a free world. In the absence of a military dog program at the beginning of the war, the United States was the exception among Western powers. The establishment of an official military dog program during World War II was a critical step in the development of the country’s military. Through the creative collaboration of civilians and military personnel, the K-9 Corps and Dogs for Defense organization produced trained military dogs that had immediate positive impacts on the battlefield. The creation of the American military dog program laid the foundation for the continued utilization of the military dog, served as the proving ground for the capabilities of dogs, and expanded the understanding of how dogs might be used on the battlefield. This piece distinguishes the U.S. Marines’ military dog program separately from the Army’s.

Keywords: war dog, military dog, military working dog, dogs, World War II, Marine Corps mascots, World War I, sentry dog, sled dog, pack dog, messenger dog, scout dog, K-9 Corps

Introduction

Dogs for Defense and the K-9 Corps

People who haven’t been at the front don’t know what a little companionship means to a man on patrol duty, or in a dugout, or what a frisky pup means to a whole company.. . . If we can’t get a dog we’ll take a goat, or a cat, or a pig, a rabbit, a sheep, or, yes, even a wildcat. . . . We’ll take anything for a trench companion— but give us a dog first.1

During the First World War, British lieutenant Ralph Kynoch articulated a fact of warfare known intrinsically by soldiers for generations: there is a unique place on the battlefield for humankind’s best friend, the dog. Decades later and an ocean away, this same feeling permeated American hearts. In 1944, Thomas Yoseloff wrote, “Those who love dogs know that they are truly man’s best friend, and in this instance they are helping men of good will in the task of preserving the democratic tradition, so that the enslaved peoples of the earth can once again walk as freemen.”2 Marine Captain William B. Putney, commanding officer of the 3d War Dog Platoon, wrote of his experiences with the dogs in World War II, “For their contribution to the war effort, the dogs paid a dear price, but the good they did was still far out of proportion to the sacrifice they made. . . . They embodied the Marine Corps motto, Semper Fidelis.”3

(Left to right) PFC Jerry Ogle, 23, of Bend, OR, with dog Sergeant; PFC Marvin W. McBane, 20, of Minneapolis, MN, with dog Rex; and Cpl Willard Layton, 26, of Bayard, WV, with dog Bones. These Marines were the first to attend the Dogs for Defense school at Fort Armstrong, Honolulu, HI, where they learned to train dogs to be sentries and also the art of attack, ca. 1943. Official U.S. Marine Corps photo, courtesy of Archives Branch, Marine Corps History Division

When the United States entered World War II, there were no plans for using dogs in the field. While European forces had experienced great success with the animals in World War I, and the soldiers of the American Expeditionary Forces bore witness to the usefulness of military dogs, the United States had never initiated its own comparable program, and even in the beginnings of World War II had no intention to do so. But once a connection was made between a qualified civilian organization, Dogs for Defense, and the military, the first steps were made toward a military dog program. Through the diverse environments of the home front, Europe, and the Pacific, military personnel were able to evaluate the abilities of dogs and the requirements for their effective use. By the war’s end, it had become clear that a military dog program was an essential component to the American military. The work accomplished by civilians and military personnel in developing this program during World War II was invaluable not only to the early war effort, but also to its continued success within the American military structure.

A mixture of dedication and chance brought about the birth of the American military dog program in early 1942. Less than four months after the attack on Pearl Harbor, the Army quartermaster general, Edmund B. Gregory, activated the K-9 Corps, the first American military dog program. The road from 7 December 1941 to 13 March 1942 was neither smooth nor predestined, and it was the work of civilians and their fledgling nonprofit, Dogs for Defense, that initiated the development of the K-9 Corps. These individuals were all members of a community known as the Fancy, made up of “breeders, trainers, professional and amateur; kennel club members, show and field trial judges, handlers, veterinarians, editors, writers; in short, people who have to do with dogs—who own dogs and love them.”4 Collectively, they represented the most knowledgeable figures in their fields on dog breeding, abilities, and training practices, which allowed them to recognize the value of dogs to American military efforts at home and overseas. In reading accounts of Pearl Harbor, they saw weaknesses exploited by the Japanese that the abilities of a trained dog could seamlessly fill, and they were driven to provide these canines to protect America.

While the leaders of Dogs for Defense marketed their mission to the government, trainers began working with select dogs to qualify them for sentry work and provide demonstratable proof of dogs’ capabilities. The canine recruits made rapid progress, but the campaigns led by Harry I. Caesar, president of Dogs for Defense, for official government contracts hit dead ends.5 Canine organizations, including the Professional Handlers’ Association and the Westbury Kennel Association, provided legitimacy to Dogs for Defense through financial contributions or, as with the American Kennel Club, through vocal approval of its mission.6 Despite these affirmations, campaigns, and demonstrations, it would be the aforementioned chance that connected the U.S. Army Quartermaster Corps and Dogs for Defense. One of Gregory’s subordinates, Lieutenant Colonel Clifford C. Smith, had not only heard of Dogs for Defense, but had witnessed several of its earliest graduates in action guarding supply depots. Smith saw the potential and presented it to Gregory, who thought the “dogs were worth a trial.”7 He sought funding for a fledgling program of 200 dogs and inquired with the American Theater Wing regarding a prior offer of financial assistance. The organization’s public relations counsel, Sidney Wain, encouraged Gregory to instead contact Dogs or Defense. As a result of this connection, on “March 13, 1942, the Army transferred its authorization for 200 trained sentry dogs to DFD [Dogs for Defense]. The date is notable for it marks the first time in the history of the United States that war dogs were officially recognized.”8 Finally, Dogs for Defense had the much-needed military contract and the first official military working dog program in the United States, the K-9 Corps, began.

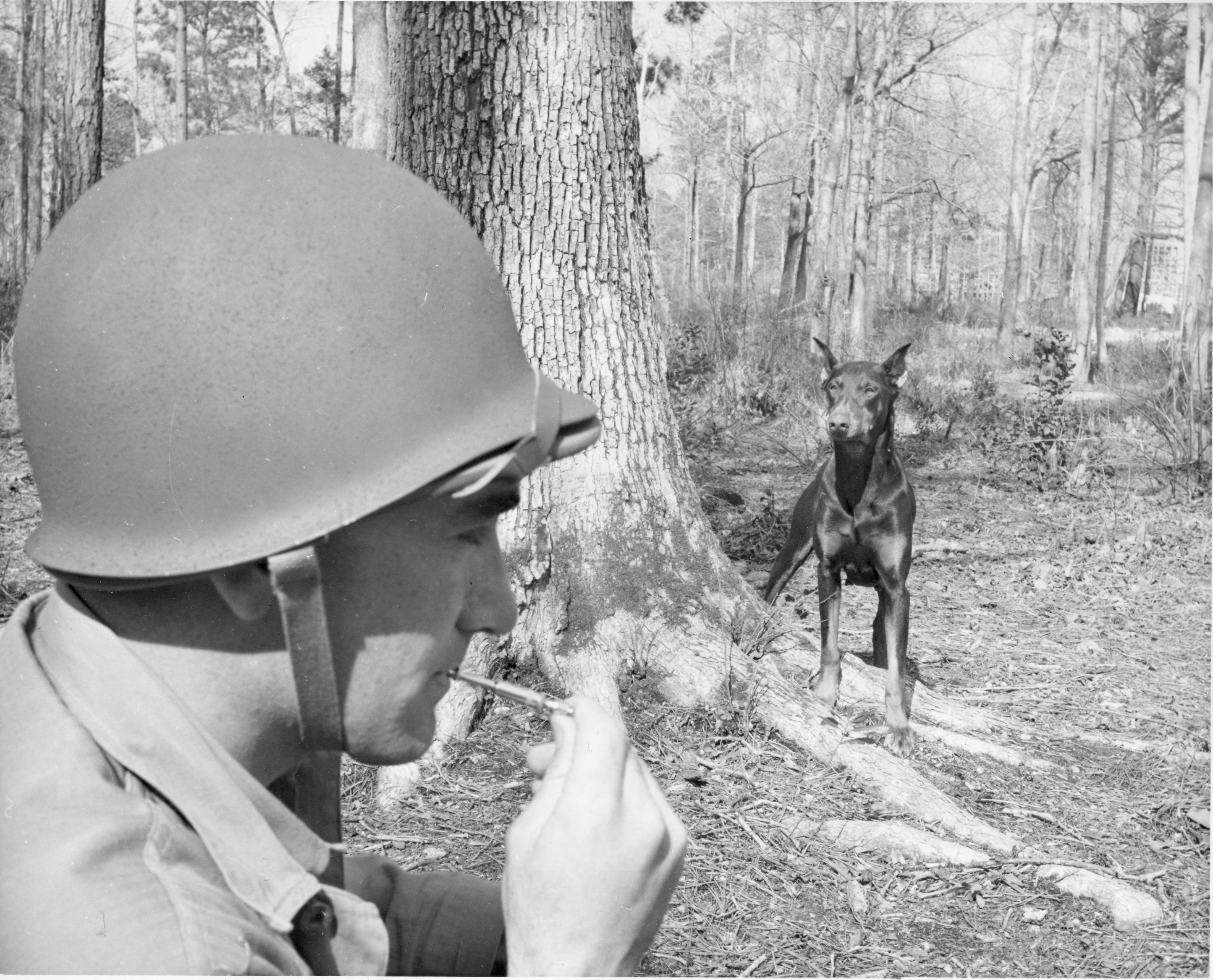

Pvt Michael PiPoi of Needham, MA, and his partner charge through the smoke of battle during training at the War Dog Detachment School, Camp Lejeune, NC. Doberman Pinschers and German Shepherds were trained by the Marines for scout, sentry, and messenger duties in the South Pacific en route to Tokyo. Official U.S. Marine Corps photo, courtesy of Archives Branch, Marine Corps History Division

Exactly a month later, on 13 April 1942, the first three sentry dog graduates went on duty at the Munitions Manufacturing Company, located in Poughkeepsie, New York.9 These were followed by nine dogs dispatched to Fort Hancock in Sandy Hook, New Jersey, under the command of U.S. Army major general Philip S. Gage, and 17 sentries to Mitchell Field on Long Island and to Staten Island.10 In July, Gage reported that after several months of continual use, the sentry dogs were seen to have an exceptional purpose “during the night blackout when their superior hearing more than compensated for the limited range of the soldier sentries’ vision.”11 Additionally, the sentry dogs “tremendously boosted the morale of the soldier.”12 In small numbers, immediate success was easily achieved, but it would quickly be seen that the logistics and colossal demands of a full-scale program would tax both the K-9 Corps and Dogs for Defense’s resources to the fullest, forcing the collaboration closer together in the process of marketing, fundraising, recruiting, transporting, and supplying the necessary dogs. These obstacles would be overcome through trial and error, producing qualified military dogs and handlers that indisputably changed the outcome of patrols, battles, and campaigns spanning from the home front to Guam, and laying the foundation for an enduring military dog program in the United States.

First Steps: Recruiting, Organizing, and Training Military Dogs

Dogs for Defense initially provided all training facilities, trainers, and resources for its sentry dogs through the collaboration of 402 kennel clubs and more than 1,000 individuals across the United States, but it became apparent that its system would need to undergo centralization to produce the estimated 125,000 dogs now demanded by the Quartermaster Corps.13 Such organization became possible once Secretary of War Harold L. Stimson gave the quartermaster general permission to expand the military dog program beyond sentry dogs on 16 July 1942. Military dogs would now include “search-and-rescue sled dogs, roving patrols, and messenger services,” and by this announcement it allowed the individual Service branches to decide how dogs would be used.14 While central oversight would be provided by the U.S. Army Quartermaster Corps, per an order from Stimson that removed the burden from Dogs for Defense, each branch would be granted flexibility in its training and utilization of the dogs to best suit the Service’s everyday needs. The Marine Corps deviated sharply from the other branches, and developed its own practices for recruitment, training, and the logistics of outfitting its War Dog Platoons. Through the oversight of the Quartermaster Corps, a total of six K-9 training centers were established during the course of the war. Each facility served a distinct purpose and provided opportunities for training simulations through varied terrain. Many of these locations graduated handlers and a small quantity of dogs that could then be transported back to their original stations to continue training other soldiers.15 Through this method, military dog training was able to occur across the country at any military posting. While military dogs were not necessary in every circumstance, such flexibility greatly increased the scope of the military dog program.

Four K-9 training facilities were established by the end of 1942 at Front Royal, Virginia; Fort Robinson, Nebraska; Camp Rimini, Montana; and San Carlos, California.16 Two more facilities opened soon after at Cat Island, Mississippi, and Camp Lejeune, North Carolina. Both dogs and handlers were trained at these facilities, preparing them for their specialized service either abroad or on the home front. While a few of the facilities trained dogs for any military branch and most positions, others were highly specialized by either branch or dog specialty, as is evidenced by Camp Lejeune. This facility was run by the Marine Corps directly, and all dogs who passed through its training were deployed in one of the Marine War Dog Platoons.17

Once the K-9 Corps training centers were established, the enlistment parameters had to be refined, particularly regarding the accepted breeds. In the beginning, the Quartermaster Corps provided broad guidelines for acceptable dogs: “Any purebred dog of either sex, physically sound, between the ages of one and five years, with characteristics of a watch-dog, qualifying under the physical examination and standard inspection of Dogs for Defense.”18 In the selection of breeds, there was some disconnect between the military and Dogs for Defense, as the latter began recruiting from a pool of 32 acceptable breeds, but the military narrowed the parameters by 1944 to include only 5 breeds for general use: “German and Belgian Shepherds, Dobermans, Collies . . . and Giant Schnauzers”; 3 breeds for sled dogs: “Malamutes, Eskimos, and Siberian Huskies”; and 2 breeds for pack dogs: “Newfoundlands and St. Bernards,” which were all carefully selected for their consistent traits that made them dependable resources.19 The Marine Corps was, once again, unique from the other military branches because it worked directly with the Doberman Pinscher Club of America to acquire well-bred Dobermans for its K-9 teams. Across most branches, purebred male dogs were the standard preference, but crossbred dogs or a spayed female would be accepted as well. The Coast Guard was the exception, as it typically preferred female over male dogs.20

Each dog’s temperament and abilities were also considered, as regardless of how well-bred, a dog without a drive to work or with a skittish nature would not be able to perform the functions of any military dog position. The dog had to be physically and mentally sound and able to handle the rigors and stressors of battle without faltering.21 Even if the dogs did not possess any prior formal training, the most important factors in determining their fitness for duty were breed, temperament, and physical fitness. Without the right combination of working drive, intelligence, loyalty, and bravery, a dog would not succeed in active combat and would be a greater danger than asset to the soldiers. Initial evaluations were oftentimes faulty, as a dog’s behavior while under shellfire could never be truly predicted. The dogs were desensitized to weapons, explosions, and the clamors of battle as much as was possible in training scenarios, but even these experiences could not prevent shellshock and other traumatic disorders from occurring in the canines. As a result, even as war dogs were being sent to the front lines in droves, there was a consistent turnover rate requiring a ready supply of fully trained dogs and handlers, which necessitated the continuation of recruitment efforts across the country.

Due to the relative infancy of the dog training field, most of the dogs accepted into the Dogs for Defense program were predominantly untrained, necessitating that their trainers begin from the basics of sit and stay before progressing to the detailed work that the dogs would be conducting in their military roles. After their acceptance into basic training, dogs were transported to their designated facility. In the Marine Corps, dogs were shipped in crates labeled with their originating location and former owner’s contact information. They were also provided with food and water for the journey, facilitated through Railway Express train systems, and sent to Camp Lejeune in North Carolina.22 Across the military branches, trains were the preferred method of transporting dogs. The longer and slower travel permitted the dogs to be exercised, rather than confined to their crates for the duration of the journey, which assisted in eliminating some excess energy and nerves prior to their arrival for training.

A German Shepherd leaps silently over the high wall on the training course that all Marine war dogs were required to master before being assigned to combat duty and deployed. Official U.S. Marine Corps photo, courtesy of Archives Branch, Marine Corps History Division

When dogs arrived at their designated training facility, they were given a brief period, ranging days to weeks, to become accustomed to military life and allow all screenings to take place, such as veterinary appointments, grooming, and finalization of enlistment paperwork. Of all of the military branches, only the Marine Corps designed and maintained record books for each military dog. These books were started on the dog’s enlistment and contained essential information, including the dog’s qualified military roles, medical history, handlers, service record, and discharge destination, be it a return to its original family or put up for adoption. It also indicated the military rank earned by the dog, which was determined based on the length of the dog’s service.23 Private first class rank was achieved with three months of service, corporal with one year, sergeant in two years, platoon sergeant in three years, gunnery sergeant in four years, and master gunnery sergeant with five years of service.24

Typically, the training process for the dog and their handler took between 8 and 12 weeks, although certain specialties could take several weeks longer.25 It began with basic training that acclimated the dogs to military service and provided foundational obedience training. Once they finished this step, trainers were able to determine which specialty best suited the dog. The remainder of the training prepared the dog and its handler for their specific role. The K-9 Corps was aware from the onset of the project that it was just as critical to select the proper handlers as it was the dogs, for it would be the K-9 team as a unit that produced results, not the dog working in isolation. Furthermore, the trainers had to be highly intelligent, physically fit, and above all, possess “a genuine love for dogs.”26 The trainers knew that to treat a dog harshly would only break its spirit and make it hesitant to perform tasks in the future, especially for the individual who had abused it. Rather, the dogs needed to be treated with genuine love and care. They were to be corrected with only words, never physical punishment, and spend as much time as possible with their handlers to forge the inseparable bonds needed to survive on the battlefield. It was well-known in the amateur as well as international dog training communities that treating a dog with kindness produces the best results.

PFC Homer J. Finley Jr. and Jan stand regular sentry duty. Photo by Pat Terry, courtesy of Records of the U.S. Marine Corps, 1775–9999, General Photograph File of the U.S. Marine Corps, 1927–1981, ID no.176250470, NARA, College Park, MD

Field and training manuals, such as the 1943 War Dogs, Training Manual (TM) 10-396, standardized these training principles for handlers.27 In addition to following the structures outlined in the manuals and by the trainers, the handlers demonstrated their devotion to their charges by spending their free time working and playing with their dogs to ensure they were prepared for the trials ahead.28 The handlers were responsible for caring for all the needs of their dogs, including regular grooming, exercise, feeding, and maintenance of their kennels. Not all initial dog and handler pairings were successful, but it was a small matter to move the dogs around until a suitable match was made. It was more important to build a confident team than it was to force the first assigned pairing of soldier and dog. Once the dogs and handlers graduated from their training, they were assigned for duty. There were six military dog specialties, and each had its own distinctions based on the branch it was intended to serve. It was key that dogs were not cross-trained between roles, as this would cause confusion and prevent the dog from adequately serving in its position.29

Marine sentries and war dogs kept nightly vigils along the shores of Okinawa to guard against surprise enemy landings. Silhouetted by the setting sun are PFC Lucien J. Vanasse of Northampton, MA, and King, a Doberman-Pinscher of a Marine War Dog platoon. Courtesy of Records of the Office of War Information, 1926–1951, RG 208, Photographs of the Allies and Axis, 1942–1945, ID no. 315834317, NARA, College Park, MD

The Roles of the Military Dog

Sentry Dogs

The sentry dog was the forerunner to all other military dog specialties. The sentry dogs were trained to guard and patrol a fixed location such as a plant, factory, or supply depot. Qualified sentry teams of a handler and dog were noted to be “the equal of six men on regular guard duty.”30 As defined in War Dogs, “The sentry dog, as the name implies, is used primarily on interior guard duty as a watch dog. . . . This class of dog is trained to give warning to his master by growling or barking or silent alert. . . . The dog, being kept on leash and close to the sentry, will also assist as a psychological factor in such circumstances.”31 Dogs would patrol with their handler around their designated facility, searching for any intruders, to prevent sabotage or destruction of government property. A unique aspect of sentry dog training was the tight bond handlers were encouraged to forge with their canine partner. Once assigned to the sentry track, dogs were not permitted to interact with any other humans aside from their handler, and the handler could not interact with any other dog.32 The goal was to “instill in his dog the idea that every human, except himself, is his natural enemy.”33 Once successful, the dog would naturally alert to the presence of any human while on duty, protecting their handler from threats long before human senses would have detected them. In a memorandum distributed by the Headquarters Hawaiian Department on 14 October 1942, it was noted that “the performance of the war dog unfailingly reflects the work habits and attitudes of the master. If the master is exact, energetic, and ‘on the job’, the dog will be the same. If the master is slothful and careless, the dog will, in time, acquire the same characteristics.”34

While most sentry dogs were not trained to attack, they were encouraged to intimidate by lunging and barking at the unknown individual. There was a thorough training process to acquire the right amount of aggressiveness in the sentry dog depending on their natural temperament; if the dog was too aggressive, the handler would work to lower the dog’s natural excitability, but if the dog was timid or too friendly, they would be encouraged to become more aggressive through simulated attacks and in group trainings with appropriately aggressive dogs.35 The key element of sentry dog training was to produce a dog distrustful of all people except for its handler so that they would alert to all threats, whether perceived or real.

Pvt Leo Crismore, USMCR, of Bloomington, IN, practices his silent whistle, which was used to direct and recall Marine dogs during scouting expeditions. Official U.S. Marine Corps photo, courtesy of Archives Branch, Marine Corps History Division

Shown in this photograph is Sgt Raymond G. Barnosky of Pontiac, MI, with a message-carrying dog in training. Official U.S. Marine Corps photo, courtesy of Archives Branch, Marine Corps History Division

Scout Dogs

The scout dog worked to detect hidden threats long before its handlers. Scout dogs differed from sentry dogs in that they were not limited to the protection of a single location but were tasked to look after a group of soldiers. They were trained “to detect and give silent warning of the presence of any foreign individual or group,” and they must be able to do so in any territory, familiar or foreign to the dog.36 Scout dogs would walk point with their handlers at the front of their unit during patrols, movements, or expeditions. In so doing, they were able to detect threats and ambushes from enemy combatants and prevent casualties. A key element in scout training was reinforcing silent alerts, which varied between dogs as some “stood tense, others crouched suddenly. Some pointed like bird dogs. With some their hackles rose or a low growl rumbled. in their throats.”37 It was critical that the dog learn to avoid barking at all costs, as that would destroy any element of surprise the alert provided the soldiers. The scout dogs were trained to work in reconnaissance patrols, combat patrols, guarding outposts, and leading scouting groups. They had to be capable of handling diverse terrain ranging from cities to jungles and work at any time of day or night without faltering. While they could work on or off leash, being on leash was always preferred because it provided the handler with greater control of the dog and prompt responses to alerts.

Scout dogs saw considerable action in the Pacific theater, where the dense jungles permitted the Japanese to ambush American soldiers. Captain William Putney, who directly oversaw the 2d and 3d War Dog Platoons, recorded his experiences with the Marine military dogs in the Pacific in his memoir, Always Faithful, in which he related a particularly painful event that took place on Guam. Putney had just finished field surgery on a dog when he was informed that one of the handlers, Private First Class Leon M. Ashton, had been walking point with his scout dog, Ginger, when she had alerted to an enemy presence. The lieutenant leading the patrol doubted Ginger, forcing Ashton to continue forward toward the potential threat. Ginger charged into the tall grass, but when Ashton followed, he was fatally shot through the neck. Ginger was reassigned to another handler, Private First Class Donald Rydgig, but he too would be killed before the war was ended. As Putney recounted, “Ginger alone survived the war.”38 Putney recorded many more stories such as Ginger’s, which gradually became more common as military dogs were fully integrated into the armed forces. Handlers would be killed or mortally wounded by enemy combatants even with the scout dog’s alert, and the dog would need to be reassigned to a new handler, if possible. Some dogs could not make the transition from one handler to another and had to be returned to their families in the United States. Even if not all lives could be saved, scout dogs like Ginger minimized the losses that did occur, and without fail became beloved members of their platoons.

Putney recalled another K-9 team that saw action on Guadalcanal. Allen Jacobson and his Doberman, Kurt, had walked point in front of a group of the 21st Marines, and Kurt alerted to an enemy presence.39 Jacobson was able to dispatch two Japanese soldiers, but a mortar shell exploded right next to him and Kurt, severely injuring both. Jacobson would be sent for immediate medical assistance, where he was treated for shrapnel wounds “in his back and shoulders,” but Putney pronounced that he “would be all right once he got to the hospital ship.”40 Kurt would not be so fortunate. Putney immediately noticed “a wedge-shaped hole in his back about three inches wide, strangely with very little blood,” as the blast and shrapnel had cauterized the blood vessels.41 The overarching concern was that “the wound would kill Kurt if the tissue over the spine swelled enough to exert pressure on the cord,” but continued survival also brought the risk of infection.42

With scarce medical supplies and limited resources at his disposal, Putney worked tirelessly to stabilize Kurt. Although the wound was closed, Putney’s fears regarding spinal pressure were realized, and morphine proved ineffective in halting Kurt’s convulsions.43 Putney did all that he could, but “at 3 A.M., Kurt stopped breathing.”44 Several hours later, Putney learned that Kurt’s alert of the Japanese soldiers had uncovered their outpost for a large Japanese force. In the ensuing battle, at least 350 Japanese soldiers were killed.45 The report from the commanding officer of the 3d Battalion, 21st Marines, acknowledged that “if Kurt had not discovered the Japanese outpost, his battalion would have stumbled into the main body of the defending force, with great losses.”46 Although Kurt’s alert came with the greatest sacrifice, his work was instrumental in saving the lives of hundreds of Marines and exemplified the work conducted daily by the war dog platoons in the Pacific theater.

Attack Dogs

Closely entwined with the sentry dog, the attack dog served a dual purpose. In addition to the standard sentry training, attack dogs received a specialized curriculum in apprehending targets through biting. While not all sentry dogs were trained to attack, attack dogs were generally trained for sentry work in addition to apprehending targets, whether saboteurs or fleeing prisoners of war. A fine balance had to be struck with the attack dogs, as they had to understand the difference between an enemy and a friend and discern which was to be attacked and which to be protected. The dog “attacks off leash on command, or on provocation, and ceases his attack on command or when resistance ends.”47 Critical considerations had to be taken when selecting attack dogs, particularly with their personality. The War Dogs manual reported that “in general, a dog which is rated under-aggressive cannot be taught to attack. The dog of average aggressiveness can be taught, though less readily, than an animal rated as overaggressive. The only difficulty in teaching the latter consists in securing prompt cessation of attack upon command.”48 Training required a soldier to act as an aggravator, teasing and riling the dog, while wearing a densely padded sleeve that formed both the target for the dog’s bite and his reward for successfully apprehending the aggravator.49 Arms were the ideal target for attack dogs, as they were a nonlethal target that forced the aggressor into submission through the force and pressure of the bite more so than a breaking of skin. Once fully trained, these dogs could assist or replace a sentry dog team and were often assigned to guard prisoners and transports.50

Messenger Dogs

Messenger dogs were trained to supplement radio and telephone technology, acting as a failsafe for when those resources were broken or destroyed, and often providing the only stable means of communication between combat areas and command centers. Messenger dogs were unique from other military dogs because they required teams of two handlers and two dogs. The canine duo was trained to go between their two masters, locating them by scent at distances of up to a kilometer. For the dogs, this was an exciting “game of hide-and-seek. . . . A dog’s delight was evident when he found one of his masters after a long run and hunt. He would obey a command to sit while the message was taken from the carrier-pouch on his collar and, praised and petted, beat a jubilant tattoo with his tail.”51 The dogs were intended to be a substitute for human messengers because they were faster and harder for the enemy to target, thereby providing a more stable method of communication while preventing the unnecessary loss of human life.52 In their training, they were given the ability to work from fixed locations and moving bases during day and night. This enabled them to be used to transport supplies ranging from telephone wire to carrier pigeons and in tandem with scout dogs on patrols, on battlefields, and for transport of resources.53 The messenger dogs needed to be trusted to make executive decisions regarding their routes and bypassing obstacles without losing focus on their target.

Messenger dogs needed to develop equally close bonds with both of their handlers to ensure the drive to find them was present when they were on duty. They were trained to associate a special collar with the task. It was designed to hold folded or rolled papers, and only placed on the dog immediately before it was dispatched. After completing its mission, the collar was removed, indicating to the dog that it was now off duty. The work of the messenger dogs was invaluable, as they were able to function as a backup when technology failed and at greater speeds than humanly capable; in most instances, messenger dogs were four to five times faster than a human at the same task.54 Despite appearing to be an antiquated system, messenger dogs were an indispensable resource to many American troops, especially those stationed in the Pacific, and they saved countless lives through their dedicated work. Putney recalled his best messenger dog, Missy, “a white German Shepherd” who was “assigned to Pfc.’s Claude Sexton and Earl Wright.”55 She was one of the fastest dogs assigned to their platoon, and had the courage to run through any obstacle to complete her mission, whether she was required to “swim rivers under fire, traverse fields with explosions, and crash through jungle vines and brush.”56 While Missy did not see extensive use in combat zones, she was the subject of a newsreel that showcased the abilities of messenger dogs.57 Messenger dogs numbered among the smallest of military dog specialties in World War II, but they remained an essential component of the military structure, one whose existence provided surety in communication and saved the lives of human messengers.58

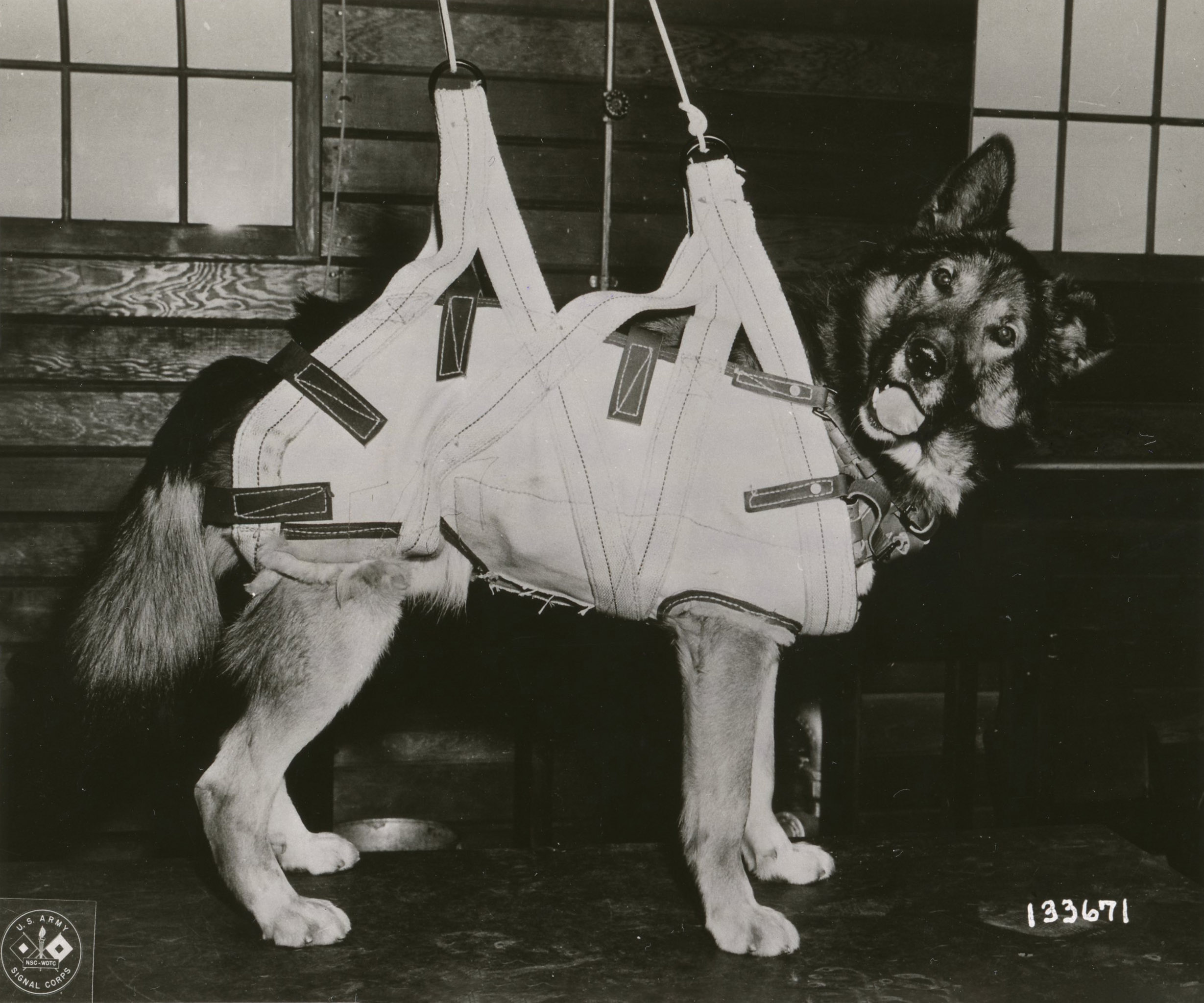

A sturdy German Shepherd, Pal, is fitted for a dog parachute harness. Pack and sled dogs were dropped by parachute to help rescue pilots forced down in Northwestern Canada. The dogs were guided down by a flight surgeon, who also carried food and medical equipment. Trained by the Remount Services, Quartermaster Corps, war dogs were used by the U.S. Army not only in warfare but also to bring aid and relief to victims of mishaps and accidents. War Dog Reception and Training Center, San Carlos, CA, ca. 1944. Courtesy of Records of the Office of the Chief Signal Officer, 1860–1985, RG 111, Photographs of American Military Activities, 1918–1981, ID no. 175539073, NARA, College Park, MD

Sled Dogs

The sled dogs, a program first initiated in the early years of the 20th century, finally saw use within the greater U.S. military structure. The established sled dog program transitioned into an Arctic search-and-rescue unit. Unlike the other specialties, which needed to have entire training and transportation programs developed in real time, the sled dogs had nearly four decades of precedent to enable seamless integration into the military dog structure. A manual had been released in 1941, Dog Team Transportation, Field Manual 25-6, outlining the care of sled dogs and the logistics of transporting the dogs, handlers, and gear. A revised edition of Dog Team Transportation would be released in 1944, providing sled dog units with the most current guidance for being most effectively used by their teams. At Camp Rimini in Montana, sled dogs experienced “refinement of the dogs themselves through a breeding program, improved training techniques, and organizational equipment assigned to military units.”59 Despite being included in the Dogs for Defense program, few sled and pack dogs were donated, as the accepted breeds were a small minority among dog owners in the United States, forcing the government to purchase the dogs from Alaska and Canada.60 As search-and-rescue teams, the sled dogs were deployed to conduct a rescue when an injured or stranded pilot was discovered by air patrols. Although the sled dog program transitioned into an experimental unit more than an active military Service, it still provided immense benefit through the hundreds of lives the dogs saved in their search-and-rescue operations as well as the work they contributed to developing adequate gear for future military dogs.61

Casualty and Mine-detection Dogs

The casualty and mine-detection dog programs experienced little success. The search-and-rescue casualty dogs transitioned out of the traditional Red Cross or mercy dog role of World War I into a formalized military position in World War II. It was a short-lived program, as the training methods used during World War II and the circumstances in which the dogs were deployed did not have the same effectiveness of their predecessors in World War I. The casualty dog program was widely considered a failure at the time, but not due to the efforts of the dogs, who succeeded in locating soldiers. Their struggle was a result of faulty training methods that led to difficulties in differentiating between the unhurt, the wounded, and the deceased, as the dogs would commence an alert for any soldier they found, regardless of his condition.

Conversely, the mine-detection dogs, or M-dogs as they were nicknamed, had immense theoretical potential. M-dogs were intended to “locate mine fields, lead the way around them, or point a safe path through them.”62 The British had trained mine dogs to great success during the war, building interest and excitement for an American program, but the training methods proved to be subpar.63 Trainers utilized attraction and repulsion methods with the M-dogs. Attraction was based on the sense of smell, locating the components of state-of-the-art nonmetallic German mines and alerting to their presence.64 Repulsion was far less successful because it relied on shocking the dogs with buried wires in an effort to create an association between buried items and discomfort. However, both were flawed strategies from the beginning. After several trial demonstrations, it was revealed the dogs trained in the attraction method were alerting to human odor around disturbed earth, while the repulsion method was doomed to failure, as it was well-known that dogs respond to positive reinforcement over negative stimuli.65 Military publications still purported that the M-dogs were “the elite of the K-9 Corps” as late as 1945.66 In later years, the M-dog program would be restarted “and provide outstanding service. The differences were time, money, and solid information combining for the big payoff.”67 Although not every military dog program was an immediate success, they all were instrumental in constructing the framework for a stable military dog program that would continue beyond the confines of World War II.

Marine Corps war dogs disembarking from of a landing barge with their Marine partners in a practice landing. Official U.S. Marine Corps photo, courtesy of Archives Branch, Marine Corps History Division

Military Dogs in Action

With handler and dog prepared for deployment in their specialty, they would be sent as teams to support American military personnel in the Pacific and European theaters. Fifteen war dog platoons were dispatched by the Army and 10 by the Marine Corps during the course of the war to serve overseas.68 The Army’s war dog platoons were divided, with seven going to Europe and the remaining eight to the Pacific.69 Marine war dog platoons were also dispatched overseas, and the canine Marines served in “the Bougainville operation (1 November to 15 December 1943). . . . Guam (21 July to 15 August 1944), Peleliu (15 September to 14 October 1944), Iwo Jima (19 February to 16 March 1945), and Okinawa (1 April to 30 June 1945),” as well as on Saipan and in Japan.70

Once dispatched to combat zones, the dogs proved to be life-saving resources for the troops in their vicinity, accurately and consistently fulfilling, if not exceeding, their mandates. The most damaging and critical struggles the dogs and handlers faced were rooted in human error. In both Europe and the Pacific, doubt about the scout dogs’ alerts led to injuries and deaths from waiting ambushes. Such casualties could have been prevented if the scout dog’s initial alert had been trusted, but the scout dog was a new technology, and most of the military was never briefed on proper implementation of the dogs and their handlers. There were also issues with camaraderie between the dog platoons and the other soldiers, as many of the latter either thought little of the dogs and their handlers or felt resentful. In most circumstances, once the dogs proved themselves, their work was trusted implicitly, but it was a process that would only be accomplished through time and experience.

The Marine Corps heavily used its military dogs throughout the war. It would be the Pacific theater that proved to have the most enduring and large-scale impact on the military dog program. In such battles as those for Bougainville and Iwo Jima, the military dogs of the Marine Corps showed their value in the thick jungles and open beaches. In every combat zone, the dogs were not immune to dangers beyond their human enemies, as diseases, accidents, and shellshock affected dogs in the thousands. These factors maintained a steady need for dogs in the Pacific until the end of the war. The Marine Corps also placed military dogs on the home front and, in some of its first uses of military dogs, made requests for qualified sentries as early as 7 June 1942, when the 1st Defense Battalion, Fleet Marine Force, requested 12 dogs for use in guarding Palmyra Atoll in Hawaii.71 In a message on 1 July 1942, commanding officer C. W. LeGette reiterated that these dogs were necessary to supplement the human sentries’ abilities. He wrote,

Due to the constant noise of the surf on the barrier reef, the absence of visibility on moonless nights, and the density of the vegetation on these Islands, it is possible for the enemy to place ashore reconnaissance patrols undetected. It will require a 200 or 300 percent increase in personnel to deny the enemy this very likely possibility. . . It is believed that the use of dogs as indicated above would greatly reduce the chances if not prevent the enemy placing patrols ashore undetected.72

The Marine Corps unit received 39 sentry dogs in December 1942 that were introduced into its patrol structure, and an additional 125 dogs were put in service elsewhere in the Hawaiian Islands.73 Eleven of the dogs received were evaluated in a report dated 2 March 1943, in which it was determined that four of the dogs were “no good” around .30-caliber machine gun posts and would need to be reassigned within the 1st Defense Battalion.74 Rather than replacing the dogs outright due to their skittish nature around the guns, Lieutenant Colonel John H. Griebel, the commanding officer, thought it more prudent to continue training the dogs for use on their bases.75

Conversely, the 16th Defense Battalion of the Fleet Marine Force did not see an equal value in the sentry dogs. In his 5 March 1943 report, the commanding officer, Lieutenant Colonel R. P. Ross Jr., wrote, “War dogs are not considered of great value at this station, but naturally they contribute somewhat to the security during darkness.”76 The terrain at the battalion’s posting on Johnston Island was not favorable to the dogs, as there was little shade to protect them from the heat of the day that was exacerbated by the surrounding water.77 Ross’s resulting decision was to return 6 of his 16 sentry dogs to the training facility at Pearl Harbor.78 Most of the Marine defense battalions posted in the Hawaiian Islands found good use for their sentry dogs, especially during night patrols when human senses were at their weakest. A review of the Marine defense battalions on Palmyra, Johnston, and Midway Islands revealed a diverse experience. Palmyra and Midway bases both found good uses for the dogs and requested additional dogs to supplement their existing teams, while Johnston’s base was the only one to see the dogs as “not of great value.”79 These evaluations revealed that not only were the dog and handler critical considerations, but that the terrain and appropriate equipment to maintain the dog’s health and effectiveness on duty were equally important to the canines’ perceived value. A single military dog solution, tactic, or program for the entire U.S. military was not practical or feasible. Rather, the handlers and soldiers on the ground would serve as essential testing components in the process of understanding how best to utilize a military dog force.

In the Pacific theater, the conditions necessitated the use of not only sentry dogs, but also scout and messenger dogs on a routine basis. The success of military dogs in the Pacific was newsworthy from the very beginning of their use, as discoveries were continually being made regarding the practicalities of utilizing dogs in a war zone. A sentry dog named Hey was present at Guadalcanal in December 1942 with the Marine Corps, and successfully thwarted an ambush from a Japanese sniper.80 During the Palau operation conducted by the Corps, the forces were able to recognize that the sentry and messenger dogs were most effective at night, because the dogs were spooked by the heavy artillery fire they experienced during the day.81 In October 1944, it was reported that the Marine Corps had transitioned out of using its Red Cross, or casualty, dogs because they were found to be ineffective in the context of the Pacific theater.82 Instead, these dogs were retrained as messengers, a position far more useful in the humid jungles that disrupted communication equipment. The few casualty dogs who were used in combat still served well despite the unfavorable conditions. Jack was one of these dogs who managed to locate and bring medical assistance to several wounded soldiers despite suffering an injury of his own on the journey.83 Deeply attached and loyal, the war dogs would serve their comrades as much as they were able, regardless of the danger.

This photo shows how the dogs were lowered over the side of a ship in landing operations. A dog would be wrapped inside a coverall blouse and lowered from the side of the ship. Official U.S. Marine Corps photo, courtesy of Archives Branch, Marine Corps History Division

While fighting on Iwo Jima, the 6th Marine War Dog Platoon’s military dogs immediately distinguished themselves on the beaches on 19 February 1945. In the early days of the campaign, the dogs were primarily utilized as sentries to detect the Japanese before they initiated their attacks.84 On 23 February, a Doberman Pinscher named Carl alerted his handler 30 minutes prior to a Japanese attack, which provided the Marines ample time to prepare a defense.85 The next day, routine patrols led by Jummy, a German Shepherd, and Hans, a Doberman Pinscher, identified the presence of enemy troops that were subsequently defeated.86 A messenger dog, Duke, was also used 25–27 February to deliver messages and casualty reports from the battalion to the regiment command post, a task in which he was successful at least four times.87 Through the effective and timely alerts of sentry and scout dogs, combined with the reliable messengers, it was determined that the military dogs were a valuable asset to the military operations, with the caveat that the dogs were discovered to be of no practical use until ground had been taken through a successful assault.88

Despite rigorous training protocols, the military failed to account for the scale of artillery fire in combat zones and its effects on dogs. Although the dogs were trained alongside gunfire, vehicles, and faux enemy combatants, most had never experienced prolonged artillery bombardments. This resulted in a number of dogs being returned early to the United States when they developed shellshock, which crippled their abilities to work on the front lines. One such dog was Andy, serial number 71 in the Marine Corps, a young Doberman Pinscher who was trained as a scout and attack dog. Andy served on Guadalcanal and Bougainville, where he distinguished himself as “an outstanding point and patrol dog.”89 However, his record noted that despite his excellent work, he “would not be good for further combat duty. Due to results caused by shell fire in combat.”90 Even though Andy, who later lost his life in the line of duty, was posthumously given an honorable discharge that noted his character as outstanding, he was not immune to the traumas inflicted by warfare.91

War dogs were also traumatized by the loss of their handlers. Due to the training methods that made the dogs completely dependent on their handlers, many dogs were rendered unusable if their handler died in battle. A reporter for the New York Times described the bond of dog and handler, writing that “in this way the intelligent animal soon becomes the alter ego of the man whose range and quickness of perception he so broadly extends.”92 It was not guaranteed that dogs could transition into a partnership with a new handler, and those who could not make the switch had to be sent back to the home front to be detrained. One such dog was a two-year-old cocker spaniel, Pistol Head, who had served for 48 missions alongside his handler, Lieutenant Colonel S. T. Willis. Willis was killed in action on his 51st mission, and Pistol Head was inconsolable to such a degree that his comrades worried he would die of grief. It was arranged for Pistol Head to return to Willis’s wife in the United States in the hope that her companionship would help him survive.93 While nothing further is recorded about Pistol Head, many dogs shared similar experiences when faced with the loss of their handler.

Pvt Ruth H. Whiteman of Philadelphia, PA, greets her Doberman Pinscher, Pvt Eram Von Lutenheimer, at Camp Lejeune, New River, NC, where both entered boot camp training with the Marine Corps Women’s Reserve and the Marine Corps Dog Detachment. Von Lutenheimer was owned jointly by Pvt Whiteman and her brother, Sgt William F. Hinkle of the Philadelphia Police Department. Whiteman’s husband, CPO Howard Whiteman, USN, was stationed overseas with a Seabee construction battalion. Photo by Cpl A.D. Hawkins, courtesy of Archives Branch, Marine Corps History Division

After the Battle: Returning to Civilian Life

In every combat theater, the military dogs distinguished themselves and proved their value to military operations. Casualties were inevitable, with many dogs losing their lives in the line of duty, from illness, or psychological breaks from the trauma of their experiences. Those who survived their tour of duty had to go through the process of detraining. Even while the war was ongoing, dogs were processed through detraining for a multitude of reasons, including injuries or illness, shellshock, and their positions phasing out. The detraining process required the dog unlearn all of the skills and tasks that had served their purposes on the battlefield. At the conclusion of the war, there were roughly 8,000 military dogs who needed to proceed through this program. Dogs for Defense came forward to oversee the detraining and adoption of the dogs, and, in conjunction with the government, helped to cover the costs for returning these dogs back to the United States.94

The detraining process took several weeks and had the dog acclimating to human interaction, the noise and activity of towns, and restraining their instincts to attack when provoked.95 One of the final tests that dogs had to pass was a field test in a busy town or city. The dogs would be exposed to a variety of noises, people, and experiences, including an interaction with an aggressive individual.96 Should the dog pass all of these scenarios without attacking, it was considered ready to return to civilian life. Although the number was few, there were dogs who, due to their aggressive temperament or traumas, could not be rehabilitated and had no other option than to be euthanized.97 Each dog who passed through the detraining program was sent home with a manual outlining the care and treatment of war dogs, which highlighted the commands and behaviors that the owner should in no circumstance use for their own safety.98 The return to civilian life was predominantly a success, and the war dogs were able to settle into a well-deserved retirement.

Despite the fearful mutterings of those concerned about allowing canine veterans back into society, there was no shortage of loving homes and accolades awaiting them. In Rockford, Illinois, the former war dogs were honored by receiving the freedom to wander their city as they pleased, and license fees were waived for the remainder of their lives.99 As early as 1944, there was public interest in adopting military dogs for both practical and sentimental reasons. Many households recognized the value of a trained dog for protection, but the demand for these dogs far outweighed the available supply.100 The original owners and handlers of the dogs were given first preference in adopting them after they were discharged. Many handlers reached out to the owners to inquire about adopting their canine partner, as the deep bonds forged between them were made through the stress of training and combat. There were reports in the press that “so far, no owner has refused to give his dog to the soldier asking for it.”101

One such fortunate handler was Private Richard Reinauer, who was granted permission to adopt his military dog partner. Rick, Marine dog number 471, was returned to his original owner, Robert Bell, who in turn transferred ownership to Reinauer in 1946.102 Not all handlers were so fortunate, as in the case of Marine dog Derek, a Doberman Pinscher, whose owners had to make difficult decisions in favor of their dog. During the war, Derek had two handlers, and one, Private First Class Henry Marsili, reached out to Mrs. Priscilla Dunn, Derek’s owner, to request ownership following the war’s end. Marsili had been Derek’s handler for two years and inquired to “possibly see some way . . . into letting me keeping him.”103 He was aware of other handlers who had received permission to adopt dogs, and was hoping for a similar response, spending much of the letter praising Derek’s qualities and great service. Mrs. Dunn was willing to consider Marsili’s request, but later decided against it on the grounds of his living situation. As she explained in a later memo,

We drove to New York City with the dog so he could see him. We had decided that although we did not want to give up “Derek” we would do so gladly if he would be happier with his Marine buddy. But the location that he lived in was entirely impossible for a dog like Derek to live—uptown New York City far away from any place to roam or run. So we brought him back to Cambridge and he adjusted overnight as though he had never been away.104

Conclusion: The Legacy of the Military Dogs of World War II

When the time came and orders were given, the military dogs of the United States proved themselves admirably in World War II. Each dog represented thousands of dollars, hundreds of personnel hours, and countless resources to train and equip for service, but their success was far from guaranteed. The story of the American military dog is one of overcoming adversity and doubt, stumbling through the unknown blindly, and fighting against the worst of odds for the sake of a bond between a handler and their canine friend. It took more than 150 years for the first military dog program to be officially initiated in the United States. The impetus of the Second World War, combined with the brave and dedicated work of civilians within Dogs for Defense, formed the perfect environment for such an event to occur. Beginning with sentry dogs on the home front, then expanding to sentries, scouts, search-and-rescue, messengers, and mine dogs, each represented an important development in the military dog institution. Beyond practical uses, the dogs provided psychological and morale benefits to the soldiers with whom they served, revealing the happiness and selfless love that still existed despite the horrors and atrocities permeating their daily lives. The place of military dogs in the United States was now firmly established. Through their dedicated service in the United States, Europe, and the Pacific, the dogs proved their valor and value by serving as a consistent, trustworthy partner to their handlers and the soldiers around them. While mistakes were made, trial and error revealed not only the best practices for utilizing war dogs on the battlefields of World War II, but also how they might be adapted for future use. It became clear that where American soldiers were present, so too should there be a dog. The skills of canine soldiers, combined with their indomitable loyalty, made them a true threat to enemy forces.

By the end of World War II, the American military dog program had exceeded all initial aspirations. In less than five years, the Army, Marine Corps, and Coast Guard had transitioned from possessing not a single trained dog to training more than 20,000 canine soldiers, each capable of fulfilling one of a number of specialties. Unlike the precedent set by European military dog programs, the American military dog program was not disbanded when the war ended. It was condensed into four Army platoons that would continue to serve and begin a breeding program to maintain a supply of qualified war dogs.105 Unfortunately, without the assistance of an organization such as Dogs for Defense, there were often few advocating for the best interests of the dogs. In the time following World War II, the efforts of military dogs slipped to the wayside of public and military interest as other military programs garnered more attention in the era of the Cold War. This made it easy for the regulations regarding military dogs to be overlooked. Nearly all of the estimated 10,000 dogs who served in Vietnam would be left behind, classified as “surplus equipment.”106 It would not be until 2000 that President William J. “Bill” Clinton would sign “Robby’s Law” into effect, which ended the systemic euthanasia of military dogs when they became too old to work.107 Through “Robby’s Law,” retiring military dogs are made available for adoption, providing them the opportunity for a quiet and peaceful retirement after years of dedicated service. Following the precedent set by Dogs for Defense, nonprofits and other civilian organizations help offset the costs of caring for retired military dogs, ranging from costly medical expenses to the daily necessity of food. The work accomplished in the first steps of the American military dog program was monumental, laying the foundation for future growth of the program into the present day.

Dogs held a unique position in American culture during the Second World War. They provided a rallying point that nearly everyone could support, regardless of personal beliefs, backgrounds, or demographics. The donation of pets represented the greatest sacrifices in displays of loyalty, patriotism, and selflessness, as families gave up their dearest companions to dangerous futures, without a guarantee of reunification. The end of the war brought difficult decisions for many families as dog handlers begged to be allowed ownership of their canine partners. Regardless of the home to which they returned or found anew, the military dog veterans were given the highest honors and praise available to them in postwar life. Over time, scholars have uncovered the stories of these brave dogs and the handlers who pioneered the first military dog program in the United States. From the works of veterans such as William Putney and Robert Fickbohm to detailed surveys by Michael G. Lemish and Charles Dean, the history of the American military dog program is being documented.

With the end of World War II, the dogs were promoted to a place of honor among other veterans. In parades, newspaper articles, movies, and books, the accomplishments of these dogs were lauded. Marine dog Derek frequently participated in parades, hospital visits, and interviews surrounding his war service. Canine veteran Thor, a boxer from Altoona, Pennsylvania, was a celebrity in his small town; he visited any business he liked, often receiving treats from the staff, and was transported by taxis and buses.108 Whether the dog served in New Jersey or Iwo Jima, alerted to 25 attacks or 1, guarded the president of the United States or a crate of rations, they each played a pivotal part in the success of American military efforts in World War II. In their faithful service during the war and their subsequent retirement, they showed that the bond between human and dog endures all things, even unto the worst of humanity, and that survival through such odds was not only possible, but that the life afterward was worth living.

•1775•

Endnotes

- Ann Bausum, Sergeant Stubby: How a Stray Dog and His Best Friend Helped Win World War I and Stole the Heart of a Nation (Washington, DC: National Geographic, 2014), 43.

- Thomas Yoseloff, Dogs for Democracy: The Story of America’s Canine Heroes in the Global War (New York: Bernard Ackerman, 1944), 11–12.

- William B. Putney, Always Faithful: A Memoir of the Marine Dogs of WWII (New York: Free Press, 2001), xi.

- Fairfax Downey, Dogs for Defense: American Dogs in the Second World War, 1941–45 (New York: Daniel P. McDonald, 1955), 15.

- Downey, Dogs for Defense, 19.

- Downey, Dogs for Defense, 18.

- Downey, Dogs for Defense, 19.

- Downey, Dogs for Defense, 21.

- Downey, Dogs for Defense, 18.

- Michael G. Lemish, War Dogs: A History of Loyalty and Heroism (Washington, DC: Brassey’s, 1996), 38.

- Downey, Dogs for Defense, 19.

- Downey, Dogs for Defense, 19.

- Downey, Dogs for Defense, 22.

- Lemish, War Dogs, 40.

- Thomas R. Buecker, Fort Robinson and the American Century (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2004), 92.

- Seth Paltzer, “The Dogs of War: The U.S. Army’s Use of Canines in World War II,” On Point 17, no. 1 (Summer 2011): 35.

- “Department of the Navy, U.S. Marine Corps. War Dog Training School, Camp Lejeune, North Carolina. 12/1942–ca.1946,” National Archives and Records Administration, accessed 8 November 2023.

- Downey, Dogs for Defense, 25.

- Downey, Dogs for Defense, 34.

- Lemish, War Dogs: A History of Loyalty and Heroism, 42.

- Downey, Dogs for Defense, 36.

- “Shipping Instructions: U.S. Marine. Corps War Dogs,” box 5, War Dogs Official Pubs, Manuals Reports, War Dogs, Collection 5440, Archives, Marine Corps History Division (MCHD), Quantico, VA.

- “U.S. Marine Corps Dog Record Book of Beau V. Milhell,” 33, Container #1 “Entry #UD-WW 100: War Dog Service Books 12/1942–06/1946,” Record Group (RG) 127, Records of the U.S. Marine Corps, War Dog Training School, Camp Lejeune, National Archives and Records Administration (NARA), College Park, MD.

- “U.S. Marine Corps Dog Record Book of Frederick of St. Thomas (Fritz), Serial No. 1,” container no. 1 “Entry #UD-WW 100: War Dog Service Books 12/1942–06/1946,” RG 127, Records of the U.S. Marine Corps, War Dog Training School, Camp Lejeune, NARA, 33.

- Arthur W. Bergeron Jr., “War Dogs: The Birth of the K-9 Corps,” U.S. Army, 16 March 2016.

- Downey, Dogs for Defense, 39.

- Downey, Dogs for Defense, 54; and War Dogs, Training Manual (TM) 10-396 (Washington, DC: U.S. War Department, 1943). Traditionally, War Dogs’s author has been identified as Alene Erlanger, as she had left Dogs for Defense to create films and training manuals for the military by the time of its publication.

- Downey, Dogs for Defense, 46.

- War Dogs, 96.

- Yoseloff, Dogs for Democracy, 12.

- War Dogs, 97, 99.

- War Dogs, 101.

- War Dogs, 100.

- “Notes on the Handling, Feeding, and Care of War Dogs,” file no. 1 C-1130 “Animals—Sentry & Warning Dogs,” 1942–43, Marine Garrison Forces Correspondence, 1941–45, Index to 1455-40, RG 127, Records of the U.S. Marine Corps, NARA.

- War Dogs, 103–5.

- War Dogs, 113.

- Downey, Dogs for Defense, 56.

- Putney, Always Faithful, 164.

- Putney, Always Faithful, 165.

- Putney, Always Faithful, 161.

- Putney, Always Faithful, 161.

- Putney, Always Faithful, 163.

- Putney, Always Faithful, 165.

- Putney, Always Faithful, 165.

- Putney, Always Faithful, 165–66.

- Putney, Always Faithful, 166.

- War Dogs, 106.

- Putney, Always Faithful, 13.

- Putney, Always Faithful, 109.

- Putney, Always Faithful, 106.

- Downey, Dogs for Defense, 56.

- War Dogs, 121.

- War Dogs, 121.

- Lemish, War Dogs, 18.

- Putney, Always Faithful, 43.

- Putney, Always Faithful, 44.

- Putney, Always Faithful, 44.

- War Dogs, 121.

- Dean, Soldiers and Sled Dogs, 27; and Dog Team Transportation, Field Manual 25-6 (Washington, DC: War Department, 1941).

- Dean, Soldiers and Sled Dogs, 27.

- Dean, Soldiers and Sled Dogs, 68.

- “Army’s M-Dogs Detect Enemy Mines,” Military Review 25, no. 3 (June 1945): 25, Articles/Extracts: Army Sources, Ca. 1912–2003, War Dogs, Collection 5440, War Dogs Articles, Clippings, box 4, Archives, MCHD.

- Anna M. Waller, Dogs and National Defense (Washington, DC: Office of the Quartermaster General, Department of the Army, 1943), 32.

- Waller, Dogs and National Defense, 32.

- Lemish, War Dogs, 94–97.

- “Army’s M-Dogs Detect Enemy Mines,” 25.

- Lemish, War Dogs, 97.

- Downey, Dogs for Defense, 58.

- Bergeron, “War Dogs.”

- “War Dogs in the Marine Corps in World War II,” War Dogs in the Marine Corps, Historical Resources Branch, MCHD, accessed 13 November 2023.

- “Dogs, Request For, June 7, 1942” file C-1130 “Animals–Sentry and Warning Dogs,” 1942–43, Marine Garrison Forces, Correspondence, 1941–45, box 1, index to 1455-40, RG 127, Records of the U.S. Marine Corps, NARA.

- “Dogs, Request For, July 1, 1942,” file C-1130 “Animals–Sentry and Warning Dogs,” 1942–43, Marine Garrison Forces, Correspondence, 1941–45, box 1, index to 1455-40, RG 127, Records of the U.S. Marine Corps, NARA.

- “War Dogs Requested Through June 1943, 7 December 1942,” file C-1130 “Animals–Sentry & Warning Dogs,” 1942–43, Marine Garrison Forces, Correspondence, 1941–45, box 1, index to 1455-40, RG 127, Records of the U.S. Marine Corps, NARA.

- “Warning Dogs, March 2, 1943,” file C-1130 “Animals–Sentry and Warning Dogs,” 1942–43, Marine Garrison Forces, Correspondence, 1941–45, box 1, index to 1455-40, RG 1276, Records of the U.S. Marine Corps, NARA.

- “Warning Dogs, March 2, 1943.”

- “Warning Dogs, March 5, 1943,” file C-1130 “Animals–Sentry and Warning Dogs,” 1942–43, Marine Garrison Forces, Correspondence, 1941–45, box 1, index to 1455-40, RG 127, Records of the U.S. Marine Corps, NARA.

- “Warning Dogs, March 5, 1943.”

- “Warning Dogs, March 5, 1943.”

- “Recommendations Concerning Dogs, March 22, 1943,” file C-1130 “Animals–Sentry and Warning Dogs,” 1942–43, Marine Garrison Forces, Correspondence, 1941–45, box 1, index to 1455-40, RG 127, Records of the U.S. Marine Corps, NARA.

- H. I. Brock, “Mentioned in Dispatches: The Front-Line Dog Has Proved Himself a Hero. Here Are the Stories of His Valor,” New York Times, 23 January 1944, 119.

- “Annex A–Phase II–Special Action Report–Palau Operation Infantry,” Collection 5440 War Dogs–Special Action Report-Palau Operation ca. 1944 file, box 5, War Dogs Official Pubs, Manuals Reports, War Dogs, Collection 5440, Archives, MCHD, 3.

- “Dog Heroes of the Marine Corps,” New York Times, 8 October 1944, 99.

- Brock, “Mentioned in Dispatches,” 119.

- “Combat Report of the Sixth Marine War Dog Platoon While Engaged in the Operation on Iwo Jima,” file no. 14, “Information on War Dogs; Combat Report & Training, 1943–45,” box 26, ONI-OCNO File Inter- views to Supply Area, 2d Base Depot, History and Museums Division, Reports, Studies and Plans Relating to World War II Military Operations, 1941–1956, RG 127, Records of the U.S. Marine Corps, NARA, 1.

- “Combat Report of the Sixth Marine War Dog Platoon While Engaged in the Operation on Iwo Jima,” 1.

- “Combat Report of the Sixth Marine War Dog Platoon While Engaged in the Operation on Iwo Jima,” 1.

- “Combat Report of the Sixth Marine War Dog Platoon While Engaged in the Operation on Iwo Jima,” 2.

- “Combat Report of the Sixth Marine War Dog Platoon While Engaged in the Operation on Iwo Jima.”

- “U.S. Marine Corps Dog Record Book of Andreas V. Wiedehurst, Serial No. 71,” container no. 1, serial no. 1–Serial No. 76, RG 127, U.S. Marine Corps War Dog Training School, Camp Lejeune, entry no. UD-WW 100: War Dog Service Books 12/1942-06/1946, NARA, 19.

- “U.S. Marine Corps Dog Record Book of Andreas V. Wiedehurst, Serial No. 71,” 4.

- “U.S. Marine Corps Dog Record Book of Andreas V. Wiedehurst, Serial No. 71,” 40.

- “Dogs to Aid in War,” New York Times, 15 June 1942, 34.

- “Dog Veteran of War Sent to Hero’s Wife,” New York Times, 28 July 1944, 14.

- Downey, Dogs for Defense, 109.

- Downey, Dogs for Defense, 109–10.

- “Many Army War Dogs Lose Minefield Jobs as New ‘Means’ Find Non-Metal Detonators,” New York Times, 28 January 1945, 7.

- Downey, Dogs for Defense, 110.

- Downey, Dogs for Defense, 112.

- Dog Heroes to Get ‘Key to City’,” New York Times, 23 September 1944, 17.

- “Army to Keep Dogs Until the War Ends: Few Trained Animals Will Be Released Now, Officials Say,” New York Times, 25 February 1944, 3.

- “Many Army War Dogs Lose Minefield Jobs as New ‘Means’ Find Non-Metal Detonators,” New York Times, 28 January 1945, 7.

- “Letter from H. W. Buse, Jr. to PFC Richard Reinauer, January 23, 1946,” Collection 4498—Personal Papers: Richard Reinauer—Correspondence: Discharge of War Dog Rick, 1946 File, Collection 4498 Personal Papers Richard Reinauer—War Dogs, Archives, MCHD.

- “Letter from Henry Marsili to Mrs. Frank Dunn, December 15, 1945,” Collection 3182 Frank Dunn—Scrapbook (2 of 2) file, Personal Papers, Coll 3812—Frank Dunn, Archives, MCHD.

- “Memo from Priscilla Dunn,” Collection 3182 Frank Dunn—Scrapbook (2 of 2) file, Personal Papers, Coll 3812—Frank Dunn, Archives, MCHD.

- Downey, Dogs for Defense, 108.

- Kristie J. Walker, “Military Working Dogs: Then and Now,” Maneuver Support (Summer 2008): 27.

- Sarah D. Cruse, “Military Working Dogs: Classification and Treatment in the U.S. Armed Forces,” Animal Law 21, no. 1 (2014): 259.

- “Eiche and Thor—About the Collection,” Robert E. Eiche Library, Penn State Altoona.