PRINTER FRIENDLY PDF

Abstract: With the onset of America’s involvement in World War II in December 1941, there was a marked upswing in the popularity of all patriotic music, including the “Marines’ Hymn.” This article provides insight into the story of the “Marines’ Hymn” during World War II, including the increase in demand for published sheet music editions and the numerous suggestions of new lyrics to reflect the wartime experiences of Marines around the globe. It also highlights the role played by Marine Corps leadership in encouraging the hymn’s popularity, both at home and in the directives given to their combat correspondents reporting from the front.

Keywords: “Marines’ Hymn,” Brigadier General Robert L. Denig, Lieutenant General Thomas Holcomb, Marine Corps Women’s Reserve, Navajo code talkers, Marine Corps Aviation

Introduction

From its mysterious nineteenth-century beginnings, the “Marines’ Hymn” became increasingly standardized and well-known throughout the 1910s and 1920s.1 It remained popular throughout the 1930s as the official song of the Marine Corps, and was frequently played on the radio, such as in “The Leathernecks,” a program broadcast on radio station WNYC by the New York detachment of the Marine Corps League starting in 1931.2 It also featured prominently in several films, such as The Cuban Love Song in 1931 and Professional Soldier in 1935.3 Short articles also regularly appeared in local newspapers that gave a brief history of the hymn and offered commentary on its quality and its popularity among the general public. The hymn’s impact as a symbol of the U.S. Marine Corps was such that after hearing it during a stop in Iceland on 16 August 1941, British prime minister Winston S. Churchill famously recalled, “[The hymn] bit so deeply into my memory that I could not get it out of my head.”4

With the onset of America’s involvement in World War II in December 1941, there was a marked upswing in the popularity of all patriotic music, including the “Marines’ Hymn,” as seen in the numerous requests from publishing companies to print new editions of the song and the steady stream of letters sent to Headquarters Marine Corps suggesting new lyrics to reflect the wartime experiences of Marines around the globe. This popularity was actively encouraged by Marine Corps leadership, who approved a new official lyric in November 1942 celebrating Marine Corps Aviation, partly in response to the growing public support for such a change. The Marine Corps also directed its combat correspondents to report stories from the front that would promote the fighting spirit, which resulted in several accounts of Marines being welcomed by rousing renditions of their own hymn by citizens of other nations worldwide. An article in a headquarters bulletin in February 1944 even boasted about this increased international familiarity of the “Marines’ Hymn” since Guadalcanal, due in part to the attention given to it in various media.

The news flashed to the world from Guadalcanal in August, 1942 did two things—it put into common use a previously little-known name and place, and it loosed on the radio and movie screen, as well as countless other places, the musical notes of the “Marines’ Hymn.” Probably at no other time—even following the heroic fight in Belleau Wood in 1918 (for there was no radio in the home then)—have the notes from the stirring song been played so often, or so universally, as following the Guadalcanal attack. Today, the words and music of the “Marines’ Hymn” are known and frequently sung by flaxen-haired Icelanders, Solomon Island natives, and the residents of the Antipodes.5

Using documents stored at the Marine Band Library in Washington, DC, and the Marine Corps History Division’s Historical Resources Branch at Quantico, Virginia, as a foundation, this article tells the story of the “Marines’ Hymn” during World War II and its role in the war effort, at home and abroad.

The Rush to Publish

By the start of the war, the Marine Corps already had a history of providing free copies of the lyrics and music of the hymn for recruiting purposes, such as when Major General Commandant Wendell C. Neville asked the Marine Corps Recruiting Bureau in Philadelphia to print 10,000 copies of the hymn for distribution in April 1929.6 This practice of offering free copies of the hymn became well-known, and several articles advertising the availability of such copies, often described as “beautifully illustrated,” at recruiting offices and mentioning their popularity among the general public are seen in local newspapers across the country throughout the 1930s.7 The recruitment purpose of this endeavor can be seen in a letter by the sergeant in charge of publicity in Louisiana printed in a local newspaper, which stated, “We are particularly interested in supplying high school bands with the music of our inspiring song, and we’d be grateful to you for the names of all groups who desire copies of the Marine Corps Hymn.”8

While the Marine Corps continued to supply free copies of the hymn during the war, this effort apparently did not meet the high public demand, and requests soon came pouring into the Division of Public Relations, led by Brigadier General Robert L. Denig, from music publishing companies that saw an opportunity to make money publishing their own editions of the song. Most requests were from companies wishing to publish arrangements of the hymn for piano or choral groups, or from those publishing songbooks for schoolchildren. However, there were more unusual requests too. In September 1942, the American Printing House for the Blind requested permission to publish a version embossed in braille; in March 1943, there was a request to publish a version in Greek; in July 1943, the O. Pagani and Brothers music company requested permission to publish one version for piano accordion and another for two mandolins and guitar; and in August 1943, the Oahu Publishing Company asked to publish an arrangement for Hawaiian guitar.9 Two Canadian publishers also requested permission, including the Provincial Normal School in Moose Jaw, Saskatchewan, which wished to include one or two good American songs in its upcoming songbook “to help foster and maintain the very fine sense of neighborliness which exists between our two countries.”10 Requests for nonmusical uses of the hymn were sent too, including from the Walter S. Mills Company to print the words of the hymn on cloth, earthenware, and decorative tiles.11

World War II-era cover of the “Marines’ Hymn” sheet music printed for complimentary distribution by the U.S. Marine Corps. Marine Band Library

BGen Robert L. Denig, director of the Division of Public Relations. Historical Resources Branch, Archives, Marine Corps History Division

Denig approved most of these requests, making sure that the publishers complied with the Marine Corps’ policy from 18 February 1942, which allowed for royalty-free use and publication of the hymn on condition that the authorized version was used, with credit given to the U.S. Marine Corps. This policy had been proposed by Brigadier General Edward A. Ostermann, adjutant and inspector of the Marine Corps, in a memorandum to Lieutenant General Commandant Thomas Holcomb, in response to a decade-long dispute about the ownership of the “Marines’ Hymn.” This dispute had mainly been between the Marine Corps, former First Sergeant L. Z. Phillips (who had been instrumental in registering the first copyright of the hymn on 19 August 1919), and the Edward B. Marks Music Corporation, which claimed to have purchased the copyright from Phillips in October 1935 and spent the next few years aggressively pursuing its rights to collect royalties from it.12 This policy was built on the precedent set in August 1931, when Major General Commandant Fuller granted L. Z. Phillips’s request to publish copies of the hymn at his own expense on the condition that he use the authorized version of the lyrics and include the credit line “Copyright 1919 by U.S. Marine Corps.”13 Between that initial letter to Phillips in August 1931 and Ostermann’s memorandum in February 1942, about 20 other publishers had received similar permission, and the number rose even higher during World War II. This policy reasserted Marine Corps ownership of the 1919 copyright of the hymn and ensured that no third party could control publication rights of the hymn or collect royalties from other publishers by claiming to be the copyright holder.

The relevance of the copyright issue at this time can be seen in the response to the Canadian Music Sales Corporation in April 1943. The company complained that a competing Canadian publisher had recently released “The Song of the Marines,” which was likely an infringement on the copyright of the “Marines’ Hymn” and offered to protect the Marine Corps’ legal interests in this matter in the Canadian market.14 In response, Rear Admiral L. E. Bratton, acting judge advocate general of the Navy stated, “The USMC copyright registration is effective in the United States only, as this country is not a member of the International Union under whose provisions a copyright registration is also effective in those countries that are members of the Union, provided that certain requirements are complied with.”15

Cover of the “Marines’ Hymn” sheet music printed by the Calumet Music Co. in 1943. Marine Band Library

World War II-era cover of the “Marines’ Hymn” sheet music printed by the Morris Music Co. Marine Band Library

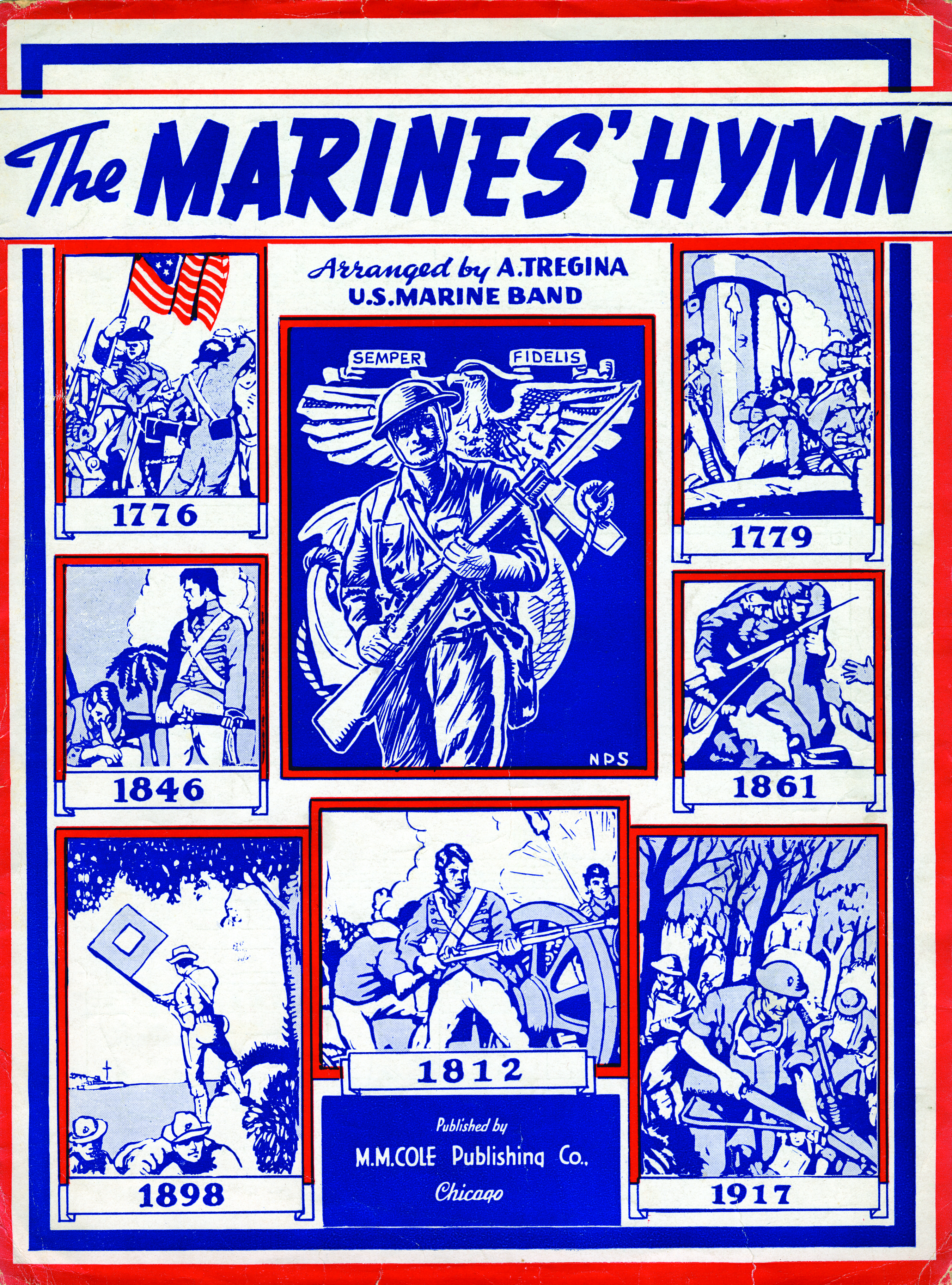

World War II-era cover of the “Marines’ Hymn” sheet music printed by the M. M. Cole Publishing Co. Marine Band Library

In addition to approving many publication requests, Brigadier General Ostermann actively corresponded with various music publishing companies to clarify the new Marine Corps free-use policy of February 1942. He reprimanded publishers who were not in compliance with the new policy and acknowledged the complaints of publishers who were frustrated by the sudden proliferation of sheet music editions of the hymn, especially those that undercut the competition by selling for 3 or 4 cents per copy, far below the usual 22 cents per copy.16 Ostermann also reassured those who had previously received cease and desist letters from the Marks Corporation that they were within their rights to publish the song royalty-free.17 For example, when the Chart Music Publishing House in Chicago sent Ostermann a check in July 1942 for 5 percent of the net revenue of its quarterly sales of the hymn, Ostermann restated that no royalties from sales of the hymn could be accepted and returned the $22.78.18

Not all requests to use the hymn were approved by the Marine Corps. For instance, in March 1942 the J. Fischer and Brother company from New York City requested permission to publish the hymn as part of a musical medley. Ostermann rejected the request, on the grounds that “the Marines consider the relation of this hymn to the Corps as analogous to the relations of the national anthem to the United States. Navy Regulations forbid the playing of the Star Spangled Banner as part of a medley, and it is the policy of the Marine Corps not to sanction the playing of ‘The Marines’ Hymn as part of a medley.”19 However, this position was either reversed or overruled the following year, when permission was given to Louis Lewyn Productions in August 1943 to use the hymn in a short film showing the U.S. Coast Guard Band playing a medley of martial airs in a musical salute to the Marines.20 Another exception to the Marine Corps’ free-use policy was the specific arrangement played by the Marine Corps Band. In March 1943, Charles E. Jenkins, a member of a 45-piece ensemble including Army band members from World War I, requested copies of the Marine Corps Band’s own arrangement, rather than the simplified version available on the market. Band Leader William F. Santelmann denied the request, on the basis that the arrangement was his own, and was only to be used by the Marine Corps Band.21 These exceptions show that although the Marine Corps had broadened its policy regarding third-party use of the hymn, it still considered the hymn to be “special property of the Marines” and reserved some uses for itself.22

On 21 November 1942, Lieutenant General Commandant Thomas Holcomb issued Letter of Instruction 267, stating that he officially approved a change in the fourth line of the first verse of the hymn from “we fight our country’s battles on the land as on the sea” to “we fight our country’s battles in the air, on land and sea.”23 The subsequent press release issued through the Associated Press on 26 November noted that, although many people had suggested similar changes to honor the contributions of Marine Corps Aviation, Commandant Holcomb specifically adopted the version proposed by retired gunnery sergeant Henry Lloyd Tallman at a recent meeting of the First Marine Aviation Force Veterans Association in Cincinnati, Ohio.24 No evidence has been found that the Marine Corps leadership asked music publishers to recall their now outdated editions, but for the remainder of the war, most responses to publication requests included a free copy of the updated lyrics and clarification that these were the correct lyrics to be used in any forthcoming editions.25 The extant letters in the Marine Corps collections also indicate that music publishers took this change in stride and were eager to publish the correct version of the hymn. For instance, immediately after the Associated Press press release, Robert Schirmer of the Boston Music Company in New York City, which had published seven different editions of the hymn since the bombing of Pearl Harbor, wrote to Denig to ascertain whether the change was indeed official, adding that “if it is, we will be more than glad to make the correction in all our editions before the next printings.”26

The Women’s Reserve and the Navajo Code Talkers

A thorough discussion of the impact and dissemination of the hymn’s updated lyric is beyond the scope of this article, but one important outcome is worth highlighting here. Namely, that the official lyric change mentioned above, which was done to recognize the contributions of Marine Corps Aviation, likely inspired other groups of Marines to celebrate their own specialized contributions to the Corps.

The Marine Corps Women’s Reserve was formed on 13 February 1943, seven months after it had been signed into law. Within the first three days, Mrs. Lillian Parker sent a letter to the director, Major Ruth C. Streeter, with a new verse honoring the Women Marines:

From the hearts and minds of all of us,

to Marines we will be true.

We will strive to give them all our help

in everything we do.

We will share their hopes for freedom

and will keep our honor clean, we are proud that we can be of use,

to United States Marines.27

In response, Major C. B. Rhoads, assistant to the director, wrote that she was interested in having a hymn specifically for the Women’s Reserve and would pass the letter on to the Division of Public Relations.28 A few weeks later Rhoads forwarded another suggested version of the hymn “for the ladies,” with similar lyrics:

From the Halls of Montezuma

to the shores of Tripoli,

you can fight our country’s battles

for we have set you free.

Though we may not leave this country

though no enemy we’ll face,

we free you for that privilege

as we quickly take your place.

So on Marines to Victory

’gainst what ever foe you find.

And leave the detail here at home

to the girls you left behind.

When history is written

and you look behind the scenes,

we are sure that you’ll be proud of us

this country’s Girl Marines.29

The tone of these entries echoes the “Free a Marine to Fight” slogan that was used in recruiting materials for the Women’s Reserve. Similar verses were sent in by other women, mostly emphasizing the supportive role the new recruits would play, but also honoring their own determination and patriotism:

From the office and the schoolroom

from the home and from the stage,

we have come to do our duty

in this hist’ry-making age;

we could not endure just waiting

and we’re tired of magazines,

so we gladly donn’d the colors

of United States Marines.

Till the starry flag of freedom

waves unchallenged in the sky,

we are standing by our brothers

as they bravely live and die.

Tho’ the way seems long and weary

as we learn what Service means,

we will never shirk or falter

we’re United States Marines.30

In July 1943, Marine Corps Band Leader William F. Santelmann forwarded to Major Streeter a recording, manuscript, and arrangement of the “March of the Marine Corps’ Women’s Reserve” that had been composed by Second Class Musician Louis Saverino, with lyrics by Second Class Musician Emil E. Grasser Jr., both of the Marine Corps Band. The piece had been composed for a presentation ceremony, when flags were presented to representatives of the Women’s Reserve, and Santelmann requested that it be selected as the official march of the Women’s Reserve.31 Major Streeter approved the request in August, with one important clarification: “Care must be taken not to call this the official ‘hymn’ of the Women’s Reserve. There is only one hymn of the Marine Corps. . . . As the Women’s Reserves are full members of the Marine Corps, this is their hymn also and no separate hymn will be authorized for them.”32

Frank V. McKinless swearing in the first Women Marines in the New York area in February 1943 at the Marines’ Women’s Reserve recruiting office. Frank V. McKinless Collection (COLL/5185), Historical Resources Branch, Archives, Marine Corps History Division

Another important group of Marines had their own relationship with the hymn. In early 1942, Navajo recruits, who would later be known as code talkers, began their training at the Marine Corps Training Center at Camp Elliott in San Diego, under the command of Staff Sergeant Phillip Johnston. An article in Marine Corps Chevron from 23 January 1943 described their daily lives, coyly noting that “naturally not much can be said about the work they’re doing in school and in battle zones. But it takes advantage of individual intelligence, military training and heredity, and is distinctly annoying to enemy forces.”33 The article also mentioned that the unit planned to “stage one of their annual ceremonial dances for the benefit of the entire camp” and that “another one of their stunts has been the translation of the ‘Marine Hymn’ into their native tongue. They sing anything at the least excuse (and well) and it’s really an experience to hear 40 odd Navajos swing out on the cocky-sounding ‘Hymn’ in ‘Navajo-ese’.”34 The text of this unique version of the hymn was not included in the article, which may have been an intentional omission due to secretive use of the Navajo language in the war effort. Two years later, in January 1944, a Marine Corps public relations officer wrote to Brigadier General Denig requesting permission to publish the text of the hymn in Navajo, stating, “If security is no longer involved, perhaps the hymn and translation could be released to service and other publications.”35 Denig denied the request, noting that “they still have the ban on mentioning or discussing Navajo Indians, therefore it would appear that the attached Marine Corps Hymn in Navajo should not be published.”36

The Navajo version of the hymn and its English translation were eventually published, with Jimmy King, a Navajo instructor at the training camp, credited as the translator:

We have conquered our enemies

All over the world.

On land and on sea,

Everywhere we fight.

True and loyal to our duty.

We are known by that.

United States Marines.

To be one is a great thing.

Our flag waves

From dawn to setting sun.

We have fought every place

Where we could take a gun.

From northern lands

to southern tropic scenes,

We are known to be tireless,

the United States Marines.

(Last verse like a prayer)

May we live in peace hereafter.

We have conquered all our foes.

No force in the world we cannot conquer,

We know of no fear.

If the Army and the Navy

ever look on Heaven’s scenes,

United States Marines will be there

Living in peace.37

This version was sung at subsequent events honoring the code talkers. One such occasion was a veterans gathering in Window Rock, Arizona, in July 1971, during which “each of the 60 participants was presented Fourth Marine Division medallions [to] commemorate Congressional Medal of Honor winner Pima Indian Ira Hayes’ part in the flagraising atop Mt. Suribachi on Iwo Jima.” Jimmy King attended the event, and “sang a Navajo version of the Marine Corps Hymn which he composed in 1943.”38

The “Marines’ Hymn” at the Front

The popularity of the “Marines’ Hymn” and its close connection to the identity of the Marine Corps was reflected in the numerous wartime news reports from around the globe. For instance, reports from Guadalcanal in September and October 1942 recounted that Japanese tactics in the thick jungles included calling out common names like Smith and Brown, and whistling the “Marines’ Hymn” and “Reveille” “to entice the enemy to reveal his positions and to deceive him as to his opponents’ whereabouts.”39 Two years later, an article in the New York Times described an account by a small advance patrol during the Battle of Kwajalein: “Five wounded marine veterans of the Marshall Islands invasion said today that they and their comrades had laughed and sung the marine hymn as they stormed the beach at Namur Island.”40

There were also several accounts of Marines being welcomed by the inhabitants of various islands in the South Pacific by rousing renditions of the “Marines’ Hymn,” often in their native languages. For instance, in an article written by a Marine Corps correspondent, First Lieutenant J. Wendell Crain recounted the successful patrol he led against a Japanese unit on Malaita in the Solomon Islands in early November 1942. Crain described how “the natives were overjoyed by our success . . . [they] gave us plenty of fruit and sang a lot of native songs for us. Before we left, they were all singing the Marine Corps hymn.”41 The following year another Marine Corps correspondent, Sergeant Ben Wahrman, reported on a version of the “Marines’ Hymn,” although with strikingly different words and melody, that he heard in the Solomon Islands. It was sung in pidgin English by the native islanders and celebrated the recent deeds of the U.S. Marines. The three-verse song was transcribed for Wahrman by island native Philip Charles Kana:

Me Maliney, fly all aloundy, longey Eastey, Longey Westey

Me sentry All Aboutey, Keepem Solomons.

My work Lookey Lookey,

Longey Landey, Longey Sea.

Hah hah, hah hah, hah hah, hah hah hah.

Me falle ecome downee, Long my parasuit

enemy shoot some, but he missey all bootee

You know me come, but where me belong him.

Hah hah, hah hah, Japanee, hah hah.

You wantem Smarseem Every Island Pacific

America Smarseem Capital Tokyo,

You look out, my friend, old man kickee back.

Me laugh long, you Japanee, hah hah42

In March 1944, Marine Corps combat correspondent Master Technical Sergeant Samuel E. Stavisky recounted how the newly liberated villagers on the island of New Britain greeted the Americans by bursting into song.

We have long since become used to their hymns, rendered in pleasing harmony, but this night they were singing something new and startling, something they didn’t understand, but knew would please the Marines who had driven out the Japanese. It was the celebrated Marine Corps Hymn. An Australian guide accompanying our combat force had taught the musical Melanesians the first two lines: “From the Halls of Montezuma to the shores of Tripoli.”43

Another account from Bougainville in March 1945 described a festive stage show put on by the Maori members of the Royal New Zealand Air Force as a tribute to the 1st Marine Aircraft Wing and Marine Major General Ralph J. Mitchell, under whom the New Zealand air units had served. The show included members of the Maori battalion wearing grass skirts and singing traditional songs, with the highlight being their singing of the “Marines’ Hymn” in the Maori language.44

Navajo code talkers on Bougainville, 1943. From left to right, front row: Pvt Earl Johnny, Pvt Kee Etsicitty, Pvt John V. Goodluck, and PFC David Jordan. From left to right, rear row: Pvt Jack C. Morgan, Pvt George H. Kirk, Pvt Tom H. Jones, and Cpl Henry Bake Jr. Photograph Collection (COLL/3948), Historical Resources Branch, Archives, Marine Corps History Division

These kinds of stories were not arbitrary observations of life in the field, but instead deliberately reflected the directives given to Marine Corps combat correspondents by Brigadier General Denig, head of the Division of Public Relations. In the aftermath of the attacks on Pearl Harbor and Wake Island in December 1941, it became clear that having journalists in the field alongside fighting Marines would be necessary to manage news and publicity during the war, and Denig began recruiting professional newspaper and public relations experts into the Marine Corps, with the first group of combat correspondents graduating from boot camp in July 1942.45 Starting in September 1942, Denig had the Division of Public Relations produce a regular “Memorandum for all Combat Correspondents” that updated the correspondents on each others’ work and provided information about what types of stories were and were not in demand. The 8 December 1942 memorandum noted that one of the two best stories produced by the correspondents so far was about the “treacheries” employed by Japanese combatants, including the tactics used on Guadalcanal mentioned above.46 The 1 February 1943 memorandum included a specific request from Leatherneck magazine for stories about “what the men think of the enemy (either combat or personal) [and] how they mix with the native population” as well as “something that would be understandable to all enlisted Marines everywhere and serve to integrate Corps morale and fighting spirit.”47 The accounts mentioned above, of Pacific Islanders welcoming Marines with exuberant renditions of the Marines’ own hymn, can be seen as a response to such a request.

MajGen Ralph J. Mitchell (left), commander, Marine Aircraft, South Pacific, who oversaw the Royal New Zealand Air Force including the Maori Battalion. Field Harris Collection (COLL/746), Historical Resources Branch, Archives, Marine Corps History Division

Denig’s most common directive to the correspondents was to report on the experiences of individual Marines: “Give most of your time and attention to the enlisted man and what he says, thinks, and does. Tell the human-interest side of the Marine Corps.”48 These personal accounts, known as “Joe Blow” stories, connected the Marines in all corners of the world to their families and communities back home, and their popularity led to the adoption of this style of war reporting by other correspondents. One such personal account referenced the “Marines’ Hymn” to heighten the emotional impact for the readers back home as it relayed the story of Private First Class Red Vanover, 21, of Louellen, Kentucky, while he lay in a hospital bed after being severely wounded on Saipan.

“I know I am going to die.” His head slowly turned toward the [doctor and two nurses]. He asked: “Will you do me a favor?” They nodded. His eyes sparkled. There were no tears; instead, a smile. “Will you have someone play, or maybe whistle or sing the Marine Hymn?” A moment of silence. His eyes closed, smiling. He was dead—and the smile was still there.49

An equally moving story from September 1945 told of the hero’s welcome given at the Yokosuka Naval Base, Japan, to the old 4th Marines, who had fought at Bataan and Corregidor, after their liberation from three years in Japanese prison camps. The celebration included steaks, jazz music, American beer, and a rendition of the “Marines’ Hymn.”

The band struck up the marine corps hymn, and as the familiar strains of “From the Halls of Montezuma to the Shores of Tripoli” rang across the field one returned prisoner—a tough-looking leatherneck with a face like a bulldog’s—began to sob openly. Tears streamed down the cheeks of half a dozen more, and those who weren’t weeping were swallowing hard. It was a long time since these men—most of them professional troops—had heard the song they lived by.50

A Hymn for Everyone

With the increased visibility of the “Marines’ Hymn” during the war, due to the proliferation of published sheet music editions and recordings, the official change in lyrics to honor Marine Corps Aviation, and references to the hymn in numerous reports from the front, it is not surprising that many ordinary Americans chose to pen their own verses of the hymn to express their support for Marines fighting around the world. This was not a new practice, as by the 1940s there was already a long tradition of both Marines and non-Marines creating various updated lyrics, either in seriousness or for their own amusement. Indeed, the newest official change to the hymn, incorporating “in the air, on land and sea” in the first verse, was approved in part because of the groundswell of public support for such a change, as seen in the many similar suggestions that were made during the start of the war. However, this long tradition of ordinary Americans writing their own verses of the hymn took on a different character during World War II. First, there was a significant increase of people sending their suggestions directly to Headquarters Marine Corps. Second, when analyzing the collections of these letters that are now kept at the Marine Corps History Division and the Marine Corps Band Library, it is clear that many people viewed their suggestions of new lyrics as a genuine part of the war effort, either as a way to offer support and comfort to active Marines, to preserve details of the war for posterity, or simply to fulfill their patriotic duty as Americans. One mother of an active-duty Marine even stated that she was inspired to write two new verses for the hymn partly because she “heard the President say that song writers should get to work on patriotic songs.”51

The earliest submission of a wartime verse in the collection of the Marine Corps Band Library is dated 12 December 1941, just five days after the attack on Pearl Harbor. It was submitted by Arthur Jenkins, who had served in the Marines from 1918 to 1919 and wrote his verse to commemorate the heroic deeds of the Marines fighting in the Pacific:

From the bay of Honolulu

to the tip of North Luzon,

we are fighting for our country

in the isles of Wake and Guam;

first to fight the yellow peril,

our glory to maintain,

we still possess the title

of United States Marines.52

The following day, an editorial was printed in the Atlanta Constitution that highlighted the connection between the fighting at Wake Island and the importance of traditions within the Marine Corps, including the hymn, that would be needed to get the Marines through the current war.

I remember talking some years ago with a very wise old man. He was saying that a man without tradition was a man without character. . . . I thought of that again, thinking of the Marines at Wake Island. The Marines have a Marine Corps hymn. When it is sung or when the music is played, they stand up and take off their hats just as the college crowds do when alma mater is played. . . . His Marine hymn gets to be a part of him. . . . That handful of Marines on Wake Island has thrilled the whole nation. They suffered severe losses, but they are there and being a little stylish about it and just a little dashing. Theatrical? Sure. They mean it to be. The Marine Corps hymn, the ribald songs, the tradition of shooting and soldiering stylishly, will help them to die in style and in a manner which will make a story and add to the Marine Corps tradition. It all adds up. The old man was right.53

Many other submissions of new verses commemorating Pearl Harbor and Wake Island soon followed, and throughout the war Americans continued to submit new lyrics to Headquarters Marine Corps to express their reactions to the harrowing news reports of various campaigns, including Guadalcanal, Saipan, Guam, Tinian, and Kiska Island. For example, Hugh Brady Long of New Jersey explained why he penned such a verse after learning about the Battle of Tarawa.

I wrote this on the day the result of the battle was announced, having in mind the commanding officer’s statement that this was the hardest test ever faced by the corps. The idea came to me while on the job as an inspector in an airplane propeller plant here, so it might be regarded as a tribute from the production front to the fighting front. Ample precedence for such an additional stanza exists, as I recall one was added after the Battle of Chateau Thiery [sic] and the Marne in the First World War. While I may not be a poet enough to do complete honor to the corps, I believe, at least, my stanza catches the spirit of the immortal saga.54

Another example came from Philip A. Mark, captain of the campus patrol at Pennsylvania State College, after the Battle of Iwo Jima.

To even borrow the music of such a song is an honor let alone write a verse. However, I sincerely feel that the last great and heroic effort of our “1945” Marines should not go unnoticed in song—in fact, in the song of the Marines. I refer, of course to the Battle of Iwo Jima. The verse I have written is the work of just an ordinary person but it takes care of one of the greatest achievements of any part of our Armed Forces.55

Not all the new verses written during the war reflected such serious topics. Some, often by Marines themselves, took a more lighthearted look at the wartime experience, such as the one printed in Leatherneck in September 1944 and written by Private First Class Donald C. Akers from an unspecified location in the South Pacific as he reflected on his time in San Diego:

From the streets of San Diego

to the shores of the Salten [sic] Sea;

where the desert winds are blowing,

and the women all love me;

where we spend our time on liberty,

pitching woo with sweet sixteens;

we’re the wolf pack of the service,

we’re United States Marines.

If you’re young, sweet and lovely,

and pure as morning dew,

you have no need to worry,

for we’ll all be after you;

We’ll start your heart to throbbing

we’ll haunt you in your dreams;

we’re the Casanovas of the fleet,

we’re United States Marines.

We can laugh and love from dark ’til dawn,

when the soldiers are in bed;

we will laugh and love when they are gone,

and the sailors are all dead.

If the Army and the Navy

ever gaze on heaven’s scenes,

they’ll find the angels in the arms

of United States Marines.56

It is also worth noting that several submissions to Headquarters Marine Corps were from servicemembers of other branches who were impressed and inspired by news from the front. Private Pink Walker, U.S. Army Air Corps Reserve, called himself a “Marine admirer” after learning about the defense of Wake Island, and submitted a verse of the hymn in the hopes that “its expresse[d] American feeling to the fullest.”57 In December 1943, Mrs. C. S. Cash wrote to the Commandant to pass on the words of her son, who was serving as a sergeant in the Army, formerly in the 7th Regiment in New York City.

[My son] says that the Marines should henceforth begin their song with “From the beach at Tarawa to” etc. instead of the “Halls of Montezuma.” Tarawa will remain thru the years as a hallowed memory—whereas—Montezuma is vague to many of ours and future eras. I hope I am not presumptuous, but my boy said, the Marines’ feat at Tarawa will be a constant reminder that they have a debt to pay on behalf of the Marines, he also said the news of that day stirred his men as nothing else has in this war.58

Other submissions were inspired by personal connections, written by the parents, siblings, and friends of Marines fighting in far-off places. Mrs. A. N. Kilmartine, a member of the American Gold Star Mothers, submitted a verse while her son was deployed in an unknown location.59 Similarly, Olive and George Roda of Rochester, New York, submitted three verses in honor of their son, Private First Class Arthur A. Roda, while he was on Guadalcanal.

I am just a mother of one of those Marines, who spent his twenty-first birthday there. To keep my mind occupied I have acquired a hobby of writing patriotic songs and verses. I have never had a complaint from my son since he entered the service of the United States Marines. Only since the news has come out in the newspapers and on the radio did I know of the real situation on Guadalcanal.60

For the Bartlett family, the hymn was a source of comfort while their son was deployed, and they wished to share their own verse with other families in a similar situation.

From the home to far off battlefields

that is where our son has gone;

he has learned the art of modern war

and will fight through to the dawn.

All Marines are trained to meet the foe

and to work unceasingly;

and they’ll all march home triumphantly

with a well-earned victory.61

Other submissions were from people who felt excluded from the larger war effort but wanted to help in any way they could. This included several teenagers and children, such as 11-year-old Jerome Silverman of San Francisco, who submitted the following verse in August 1944:

On Tarawa they told us we had to hold,

you could hear the rifles crack.

The enemy attacked from every side

but by-gosh we drove ’em back.

We have fought on bloody beach-heads,

we have fought in Normandy,

and we glory in the title

of the United States Marines.62

Many of these younger lyricists expressed admiration for the Marine Corps and a desire to join once they were old enough. In a similar vein, letters were submitted by adults who had tried to enlist in military service but were denied and were now looking for other outlets to lend their support. Charles A. Darr, who had made the suggestion to add the line “in the air, on the land and sea” in July 1942, sent a follow-up letter in November 1942 to Lieutenant General Commandant Holcomb to express his pleasure that the change had been officially approved (mistakenly taking credit for it), and his frustration at being denied a chance to serve: “I have tried three times to get into the service but because I am 62 years of age and too many of the brass hats do not fully realize we have a war on, that there are exceptions to all rules in an emergency, I cannot get in, even to being inducted and detailed for clerical work.” Instead, he settled on calling himself an “Honorary member of the Marines.”63 David W. Miner from Washington, DC, likewise turned to the hymn after the disappointment of being deemed unfit for military service and honorably discharged from the Marine Corps. “My commanding officer Brigadier General E. P. Moses, told me that I could help win the war at home. I have written, sir, a last verse to the famous Marine Hymn. Will you please give it a little consideration, as it is all that I am able to offer.”64

For the most part, these letters were accepted with a simple note of thanks for all the fine tributes that the many friends of the Marine Corps had submitted, and an acknowledgment that the submissions of new verses were being compiled for future reference. In the case of younger letter writers, the responses also included Marine Corps recruiting pamphlets. However, the responses after the official lyric change in November 1942 also made clear that the Marine Corps was not planning to make further changes to the “Marines’ Hymn.” As stated in one response, “The Hymn and its words have become so much a part of the Corps’ tradition that any attempt to change them would bring about a storm of protest.”65

Marine Corps leadership graciously accepted these private letters, but actively discouraged those who expressed a wish to share their new verses more publicly. For instance, in October 1944, Mrs. Clara Fauteck of Wichita, Kansas, asked permission to sing her two new verses at a meeting of the Southern Kansas Marine Corps Auxiliary. She had written the verses to honor her son, Corporal Robert J. Fauteck, a machine gunner who had fought on Tarawa, Saipan, and Tinian and believed her sentiments as a mother at war would be best expressed through the melody of the “Marines’ Hymn.”

We are firmly convinced that no other tune would fit these two verses and that no Leatherneck can appreciate any tune but their own beloved Marines’ Hymn. I honestly believe that this would encourage our Marines and build up their morale, which is already good. I have written from the viewpoint of a Marine, for those Marines who would like to express themselves in song, and cannot. I have tried to write what I believe they have in their hearts. I believe they need these lines now, not after Japan has been whipped. For that reason, above all, I ask that you grant permission for these lines to be used for the glory of the United States Marines.66

Denig rejected the request, stating that “it has long been an established policy of the Marine Corps not to authorize the inclusion of any additional verses to the official copyrighted version of the song; also not to authorize the use of music with words other than those of the official version.”67 This stance was extended to celebrities too. In November 1945, television station CBS in New York City requested permission to allow Frank Sinatra to sing a parody of the “Marines’ Hymn” on an upcoming radio broadcast. “It would be a parody ‘From the Shores of California to the hills of Tennessee’ and would pay tribute to the people who built the bombers, made guns, etc. It will be used along with parodies of Home on the Range (Tribute to West); Oklahoma (Midwest and Central) and Land of the Big Sky Waters (North).”68 When the request was denied on the basis that it would violate the Marine Corps’ policy of only authorizing use of the official copyrighted version of the hymn, the origin of this policy was explicitly cited as the memo written by Brigadier General Ostermann on 18 February 1942.69

Another Change to the Hymn?

Despite the Marine Corps’ stance that official changes to the hymn would not be considered after November 1942, as the war came to a close and Americans reflected on the enormity of its impact, there were repeated suggestions in 1945 and 1946 to officially change the hymn’s lyrics to honor the extraordinary Marines of World War II. One suggestion came from the Hageman-Wegis detachment of the Marine Corps League in its November 1945 booklet honoring Marines from Kern County, California.

New verses should be added to that stirring marine corps hymn to include the immortal heroism of the corps at Guadalcanal, Tarawa, Saipan, Tinian, Iwo Jima, Okinawa; indeed all that galaxy of strange named places, the lustre [sic] of which shall brighten with the polish of history, as time adds them to the annals of the corps. Their names are written in the blood of its men.70

In March 1946, Joseph W. Wells of Norfolk, Virginia, proposed two new verses to the hymn, which he initially composed while serving with the V Amphibious Corps during the assault and seizure of Iwo Jima. These new verses were submitted with the intention of officially honoring the exploits of the Marines in both world wars:

From the blood-soaked beach at Lunga Point

to Tulagi’s shell-ripped shore,

from the runway strip on Henderson

where Grumman Wildcats roar.

We have trod Decatur’s hallowed path,

for God and country’s sake,

from the “Philadelphia’s” blazing guns

to the sacred soil of Wake.

Through the crimson surf at Tarawa

to Suribachi’s Crest,

Through the littered streets of Garapan,

we followed in our quest.

We have sought Jehovah’s guiding hand,

we have prayed as best we could,

that we might fight as well as those

who fell at Belleau Wood.71

In December 1946, Colonel Robert D. Heinl Jr., officer-in-charge of the Marine Corps Historical Section, sent a memo to the director of the Division of Public Information in which he officially recommended consideration of adding a verse to the hymn “embodying the soldierly achievements, traditions and victories of the Corps in World War II.” He further suggested that a nationwide competition be organized for such a purpose, with the winning entry to be chosen by the Commandant “with the assistance of a board of nationally distinguished literary men” and a prize of $500 offered by the Marine Corps Fund. Heinl also noted “that properly handled and exploited, it would prove to be a source of much desirable general publicity for the Marine Corps.”72 Although no response to this recommendation was found in the files, it is clear that Heinl’s suggesting was not approved, and lyrics commemorating World War II were never officially added to the hymn. However, Heinl’s recommendation was significant in that it carried on the decades-old tradition of wanting to keep the hymn updated and relevant to new generations, and because it looked to the public rather than professional songwriters for the new lyrics. The proposed selection process may have been a departure from the way previous changes were approved, but the keen awareness of the potential publicity boost from such a change was very much in line with past decisions regarding the hymn. Heinl’s proposed selection process was even referenced nearly 30 years later, in a response by Colonel C. W. Hoffner, deputy director of information, to yet another proposal to update the hymn’s lyrics: “The longstanding tradition and history associated with the Marines’ Hymn are not likely to allow for changes or additions to the piece. . . . If another verse should be added to the Marines’ Hymn I am sure it will be announced to the public for composition on a competitive basis.”73

Suggestions to incorporate lyrics relating to World War II, sometimes in conjunction with those honoring World War I and the Korean War, continued for many years. For instance, during his speech as guest of honor at the Marine Corps birthday dinner in November 1970, Walter H. Annenberg, U.S. ambassador to the United Kingdom, stated, “I would respectfully suggest that the tremendous Marine participation at Château Thierry and Belleau Wood, as well as the heroic episodes of the Pacific, from Guadalcanal to Iwo Jima, be incorporated in a further stanza of your traditional song.”74 In April 2002, Jack V. Scarola submitted six verses of his self-penned “Marine Hymn of the Forties,” which he hoped would supplement, not supplant, the existing “Marines’ Hymn” that honored Marine Corps achievements of the nineteenth century. Although Scarola had served in the Marine Corps in the late 1950s, he felt compelled to honor the previous generation of Marines, the “unique breed of Americans who enabled our nation and her allies to survive a truly unique crisis, [who] deserve this lasting honorific tribute to their courage, sacrifices, achievement and unforgettable Rendezvous With Destiny” in his new verses.75

Time will tell if the hymn is ever updated to specifically honor the Marines who fought in World War II, but considering that the previous changes, honoring Marine Corps Aviation in 1942 and adding the “First to Fight” slogan during World War I, were added during moments in history when they were most relevant, as more time passes it becomes increasingly unlikely.

Conclusion

The “Marines’ Hymn” had already been an integral part of Marine Corps identity for decades, but during World War II it became more popular and visible than ever before. It could be accessed in sheet music, phonograph recordings, radio, movies, and numerous news reports from the front. Furthermore, many Americans found comfort and strength by adding their own words to the famous song in response to the overwhelming scope of the war and their fears for loved ones serving abroad.

On 16 August 1945, Hanson W. Baldwin, who had won a Pulitzer Prize for journalism in 1943 for his coverage of the Southwest Pacific theater, published an article in the New York Times pondering what life after such a devasting war would look like, and how the American armed forces had fared.

Gone, but never forgotten. For the Pacific battles have become warp and woof of our tradition, to be passed down from generation unto generation as our rightful heritage. The marines, perhaps the proudest corps of a proud nation, have added new verses to their stirring hymn; Army outfits storied with past glories fly new battle streamers; the strong ships and the stout ships of a Navy unequaled in any epoch conceal their battles scars beneath new peace time paint.76

It is striking that the main comment about the impact of the war on the Marine Corps, written by a man who had witnessed the Guadalcanal campaign firsthand, was about the wartime experience of the “Marines’ Hymn.” Baldwin was likely aware that the Marines had not literally added new verses to their hymn during the war, and rather, his comment may allude to both the numerous unofficial additions to the hymn written by average citizens as a way of enduring the war years, and also to the knowledge that the lyrics and spirit of the hymn would now be forever associated in the American mind with many more campaigns than merely the ones enumerated in the famous first lines.

On 13 January 1945, the Halls of Montezuma radio program broadcast its 139th episode, “Poetry in War,” which was dedicated to “poetry written by Marines inspired by the emotions of battle; and martial music played by the Post Band.”77 The weekly program, which first aired in April 1942, was entirely produced by enlisted men in the San Diego area and focused on dramatizing “the stories of Marines, past and present, who have become heroes in action.” According to a November 1942 press release, the show was heard on about 140 radio stations nationwide, with an audience of around 7,000,000.78 The “Poetry in War” episode featured a section focusing on the hymn, with a brief account of its history, highlighting the contributions of individual Marines over the years, including “the words another Marine left to be sung by those who would follow after him” written in the South Pacific in 1942:

In the merry hell of Guad’canal,

we paved the way once more.

Ripped the Nipponese from cocoa trees,

and we opened Truk’s front door.

Crossed the bridge of Tanambogo,

Stormed Gavutu’s cave-torn hill,

Repaying Heaven’s Sons with steel and gun,

Marines have settled one more bill.

By Lunga’s side our comrades died,

in the fight to keep us free.

In the crawling mud they spilled their blood,

moving on to victory.

Rising wounded out of foxholes,

in sleepless grim routine.

To alien sky they gave reply

as to “Why is a Marine.”

On guts and luck in jungle muck,

we have seen our Wildcats rise,

and with hammering guns, our flying song,

swept Zeros from the skies.

Keeping rendezvous with glory,

far above Tulagi’s strand,

Geiger’s boys up high echo the cry,

“Situation’s well in hand.”

Now when Gabriel toots his mighty flute

calling old comrades home,

and Tojo’s ears have hung for years,

on Valhalla’s golden dome,

Then the Lord will wink at Vandegrift,

while he’s eating Spam and beans,

saying, “God on high sees eye to eye,

with United States Marines.”79

The episode also included a poignant description of what it meant for a Marine to hear the hymn, deliberately connecting the generation that fought in World War II with all the Marines who had come before.

The Marine Hymn is a song dear to the heart of every Leatherneck because it bespeaks the spirit of the Corps. When you’re sweaty and tired and your dogs are battered and you’re covered with mud made up of dust and sweat; when the pack weighs a ton and your cartridge belt seems filled with 15-inch shells instead of caliber 30 ball; when you’re too tired to cuss and want to fall in your tracks and sleep; when you’re like that, brother . . . and the band way up ahead strikes up the old hymn with a flare of drums and trumpets, one by one the voices start in singing, chins and chests come up and our legs seem to swing in rhythm . . . right away you become a part of that tradition that has carried the Marines through 160 years of fight and fire.80

•1775•

Endnotes

- For the first two articles in this series about the history of the “Marines’ Hymn,” see Lauren Bowers, “A Song with ‘Dash’ and ‘Pep’: A History of the ‘Marines’ Hymn’ to 1919,” Marine Corps History 6, no. 2 (Winter 2020): 5–22, https://doi.org/10.35318/mch.2020060201; and Lauren Bowers, “The ‘Devil-May-Care Song of the Leathernecks’: A History of the ‘Marines’ Hymn,’ 1920–47,” Marine Corps History 7, no. 2 (Winter 2021): 36–53, https://doi.org/10.35318/mch.2021070203.

- Jo Ranson, “Radio Dial-Log,” Brooklyn (NY) Daily Eagle, 19 December 1931, 13.

- Although The Cuban Love Song was able to use the “Marines’ Hymn” freely in the United States, when the film played in Europe, film studio MGM had to pay royalties to the descendants of Jacques Offenbach, credited as the composer of the tune, in accordance with local copyright laws. Glen Beverly, “Those Indefatigable ‘Musical G-Men’,” Brooklyn (NY) Daily Eagle, 27 June 1937, 53.

- Winston S. Churchill, The Second World War, vol. 3, The Grand Alliance (Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1950), 449.

- “The Marines’ Hymn Sung Round the World,” Headquarters bulletin, February 1944, Marines’ Hymn file, U.S. Marine Band Library, Washington, DC, 9.

- MajGen Cmdt Wendell C. Neville to the Officer in Charge, Marine Corps Recruiting Bureau, Philadelphia, 24 April 1929, Hymn subject file, Historical Resources Branch, Marine Corps History Division (MCHD), Quantico, VA.

- Casey, “Sea Soldiers’ Song Is Mystery Ballad,” 4; and “Who Wants Free Copy of U.S. Marine Hymn?,” Courier-Post (Camden, NJ), 25 June 1936, 33.

- Sgt Richard C. Seither, “Marine Corps Hymn,” Tensas Gazette (Saint Joseph, LA), 6 March 1942, 1.

- American Printing House for the Blind to BGen Robert L. Denig, 15 September 1942; William F. Santelmann, memo to T. F. Carley, 15 March 1943; Theresa Costello, O. Pagani and Bro. to BGen Robert L. Denig, 20 July 1943; and Harry Stanley, Oahu Publishing Company to BGen Robert L. Denig, 30 August 1943, Marines’ Hymn file, U.S. Marine Band Library.

- R. J. Staples, Provincial Normal School, Saskatchewan, Canada to BGen Franklin A. Hart, 9 March 1946, Marine Corps Hymn Correspondence, January 1943–August 1946, Historical Resources Branch, MCHD.

- Walter S. Mills Company, Ltd. to BGen Robert L. Denig, 20 May 1943; and BGen Robert L. Denig to Walter S. Mills Company Ltd., 25 May 1943, Marine Corps Hymn Correspondence, January 1943–August 1946, Historical Resources Branch, MCHD.

- BGen Edward A. Ostermann, memo to LtGen Cmdt Thomas Holcomb, 18 February 1942, Marines’ Hymn file, U.S. Marine Band Library, hereafter Ostermann memo to Holcomb; and Bowers, “The ‘Devil-May-Care Song of the Leathernecks’,” 41–47.

- Quoted in Ostermann memo to Holcomb.

- Canadian Music Sales Corporation, Ltd. to LtGen Commandant Thomas Holcomb, 7 April 1943, Marines’ Hymn file, U.S. Marine Band Library.

- RAdm L. E. Bratton to W. S. Low, 27 April 1943, Marines’ Hymn file, U.S. Marine Band Library.

- Eugene A. Warner, Chart Music Publishing House, Inc. to BGen Edward A. Ostermann, 28 July 1942, Marines’ Hymn file, U.S. Marine Band Library, hereafter Warner letter to Ostermann.

- BGen Edward A. Ostermann to Manhattan Publications, 30 April 1942, Hymn subject file, Historical Resources Branch, MCHD; BGen Edward A. Ostermann, to the Morris Music Company, 31 July 1942; and R. L. Kramer, Morris Music Company to BGen Edward A. Ostermann, 3 August 1942, Marines’ Hymn file, U.S. Marine Band Library.

- Warner letter to Ostermann; and BGen Edward A. Ostermann to Eugene A. Warner, 31 July 1942, Marines’ Hymn file, U.S. Marine Band Library.

- J. Fischer and Bro. to U.S. Marine Corps, 20 March 1942; and BGen Edward A. Ostermann to J. Fischer and Bro., 23 March 1942, Marines’ Hymn file, U.S. Marine Band Library, hereafter Ostermann letter to J. Fischer and Bro.

- Louis Lewyn, Louis Lewyn Productions to U.S. Marine Corps, 19 August 1943; and BGen Robert L. Denig to Louis Lewyn, 21 August 1943, Marine Corps Hymn Correspondence, January 1943–August 1946, Historical Resources Branch, MCHD.

- Charles E. Jenkins to Director, Marine Corps Band, 20 March 1943; and William F. Santelmann to Charles E. Jenkins, 1 April 1943, Marines’ Hymn file, U.S. Marine Band Library.

- Ostermann letter to J. Fischer and Bro.

- LtGen Cmdt Thomas Holcomb, Letter of Instruction 267, 25 November 1942, Hymn subject file, Historical Resources Branch, MCHD.

- “Alteration Made in Marine Anthem: First Verse Revamped to Give Recognition to Troops in Air Branch,” Baltimore (MD) Sun, 27 November 1942, 4, 28; and Bowers, “The ‘Devil-May-Care Song of the Leathernecks’,” 47–51.

- Some examples: BGen Robert L. Denig to Ginn and Company, Educational Publishers, 31 December 1942; LtCol G. T. Van Der Hoef to Harry Stanley, Oahu Publishing Company, 15 September 1943; BGen Robert L. Denig to Max T. Krone, Associate Director, School of Music, University of Southern California, 30 November 1943; and BGen Robert L. Denig to Leonard Greene, Sam Fox Publishing Company, 8 January 1944, Marines’ Hymn file, U.S. Marine Band Library.

- Robert Schirmer, Boston Music Company to BGen Robert L. Denig, 27 November 1942, Marines’ Hymn file, U.S. Marine Band Library.

- Lillian Parker to Maj Ruth Streeter, 16 February 1943, Marine Corps Hymn Correspondence, January 1943–August 1946, Historical Resources Branch, MCHD.

- 19 February Response from Maj C. B. Rhoads to Lillian Parker, 19 February 1943, Marine Corps Hymn Correspondence, January 1943–August 1946, Historical Resources Branch, MCHD.

- Maj C. B. Rhoads, memo to LtCol G. T. Van Der Hoef, 4 March 1943, Marine Corps Hymn Correspondence, January 1943–August 1946, Historical Resources Branch, MCHD.

- Quoted in BGen Robert L. Denig to Thelma M. Parker, 24 March 1943, Hymn subject file, Historical Resources Branch, MCHD.

- William F. Santelmann to Maj Ruth C. Streeter, 15 July 1943, Hymn subject file, Historical Resources Branch, MCHD.

- Maj Ruth C. Streeter to Max Winkler, 13 August 1943, Hymn subject file, Historical Resources Branch, MCHD.

- PFC Bruce Deobler, “Navajos Readying to Going Tough for ‘Japanazis’,” Marine Corps Chevron, 23 January 1943, 3.

- Deobler, “Navajos Readying to Going Tough,” 3.

- 1stLt C. E. McVarish to BGen Robert L. Denig, 25 January 1944, Marine Corps Hymn Correspondence, January 1943–August 1946, Historical Resources Branch, MCHD.

- BGen Robert L. Denig to 1stLt C. E. McVarish, 29 January 1944, Marine Corps Hymn Correspondence, January 1943–August 1946, Historical Resources Branch, MCHD.

- Doris A. Paul, The Navajo Code Talkers (Bryn Mawr, PA: Dorrance, 1973) 21–22.

- “Navajo Codetalkers Assemble, Relive Days of WWII Glory,” Albuquerque (NM) Journal, 11 July 1971, 6.

- Hanson W. Baldwin, “Japs Whistle Reveille, Sing Marines’ Hymn,” Chicago (IL) Tribune, 29 September 1942, 2; and “Guadalcanal,” New York Times, 18 October 1942, 1.

- “Five Marines Tell of Namur Landing,” New York Times, 14 February 1944, 7.

- Sgt James W. Hurlbut, “40 Marines Do a 100% Job,” New York Times, 15 December 1942, 10.

- Sgt Ben Wahrman, Press Release 163, 26 November 1943, Hymn subject file, Historical Resources Branch, MCHD. Solomon Islands pidgin is one of the primary languages spoken among the citizens of the Solomons, due to there being in regular use between 70 and 120 different languages and dialects, in addition to English as the official language.

- Samuel E. Stavisky, “Natives Greet Marines by Singing Corps Hymn,” Brattleboro (VT) Reformer, 28 March 1944, 1.

- New Zealanders Honor Marines,” Courier-News (Bridgewater, NJ), 6 March 1945, 8.

- Colin Colbourn, “Esprit de Marine Corps: The Making of the Modern Marine Corps through Public Relations, 1898–1945” (PhD diss., University of Southern Mississippi, 2018), 165–66.

- BGen Robert L. Denig, “Memorandum for all Combat Correspondents,” 8 December 1942, Combat Correspondents subject file, Historical Resources Branch, MCHD, 2.

- BGen Robert L. Denig, “Memorandum for all Combat Correspondents,” 1 February 1943, Combat Correspondents subject file, Historical Resources Branch, MCHD, 8.

- Quoted in Colbourn, “Esprit de Marine Corps,” 171–72.

- “Death Cheats Doctors of Chance to Grant Dying Kentuckian’s Request to Hear Marine Corps Hymn,” Cincinnati (OH) Enquirer, 23 January 1945, 1.

- Hal Boyle, “Homecoming for Bataan’s Marines Fourth Welcomes Back Survivors,” Joplin (MO) Globe, 7 September 1945, 1.

- Clara Fauteck to BGen Robert L. Denig, 28 October 1944, Marine Corps Hymn Correspondence, January 1943–August 1946, Historical Resources Branch, MCHD.

- Arthur Jenkins to the Marine Corps Band, 12 December 1941, Marines’ Hymn file, U.S. Marine Band Library.

- Ralph McGill, “One Word More,” Atlanta (GA) Constitution, 13 December 1942, 8.

- Hugh Brady Long to BGen Robert L. Denig, 13 December 1943, Marine Corps Hymn Correspondence, January 1943–August 1946, Historical Resources Branch, MCHD.

- Philip A. Mark, to BGen Robert L. Denig, 31 March 1945, Marine Corps Hymn Correspondence, January 1943–August 1946, Historical Resources Branch, MCHD.

- “Parody from Perdition,” Leatherneck (Pacific Edition), 15 September 1944, 28.

- Pvt Pink Walker, to BGen Robert L. Denig, 6 January 1943, Marine Corps Hymn Correspondence, January 1943–August 1946, Historical Resources Branch, MCHD.

- C. S. Cash to LtGen Cmdt Thomas Holcomb, December 1943, Marine Corps Hymn Correspondence, January 1943–August 1946, Historical Resources Branch, MCHD.

- Quoted in Roberta Jacobs to BGen Robert L. Denig, 10 January 1943, Marine Corps Hymn Correspondence, January 1943–August 1946, Historical Resources Branch, MCHD.

- Olive and George C. Roda to BGen Robert L. Denig, 28 February 1943, Marine Corps Hymn Correspondence, January 1943–August 1946, Historical Resources Branch, MCHD.

- Bartlett Family to the Marine Corps Association, 22 January 1943, Hymn subject file, Historical Resources Branch, MCHD.

- Jerome Silverman to BGen Robert L. Denig, 10 August 1944, Marine Corps Hymn Correspondence, January 1943–August 1946, Historical Resources Branch, MCHD.

- Charles A. Darr to LtGen Cmdt Thomas Holcomb, 28 November 1942, Marines’ Hymn file, U.S. Marine Band Library.

- David W. Miner to BGen Robert L. Denig, 13 April 1944, Marine Corps Hymn Correspondence, January 1943–August 1946, Historical Resources Branch, MCHD.

- LtCol G. T. Van Der Hoef to C. S. Cash, 20 December 1943, Marine Corps Hymn Correspondence, January 1943–August 1946, Historical Resources Branch, MCHD.

- Clara Fauteck to BGen Robert L. Denig, 28 October 1944, Marine Corps Hymn Correspondence, January 1943–August 1946, Historical Resources Branch, MCHD.

- BGen Robert L. Denig to Clara Fauteck, 3 November 1944, Marine Corps Hymn Correspondence, January 1943–August 1946, Historical Resources Branch, MCHD.

- Memorandum to BGen Robert L. Denig and Col E. R. Hagenah, November 1945, Marine Corps Hymn Correspondence, January 1943–August 1946, Historical Resources Branch, MCHD.

- J. T. Carley, Memorandum to Col E. R. Hagenah, November 1945, Marine Corps Hymn Correspondence, January 1943–August 1946, Historical Resources Branch, MCHD.

- “Local Detachment Honors Marine Corps: Booklet Features Kern ‘Leathernecks’ in War,” Bakersfield Californian, 1 November 1945, 13.

- Joseph W. Wells to BGen Robert L. Denig, 28 March 1946, Marine Corps Hymn Correspondence, January 1943–August 1946, Historical Resources Branch, MCHD.

- Robert D. Heinl Jr., memorandum to Director, Division of Public Information, 30 December 1946, Marines’ Hymn file, U.S. Marine Band Library.

- Col C. W. Hoffner to Robert E. Anti, 11 December 1975, Marine Corps Hymn Correspondence, January 1943–August 1946, Historical Resources Branch, MCHD.

- Ambassador Walter H. Annenberg, speech, 11 November 1970, Marines’ Hymn file, U.S. Marine Band Library.

- Jack V. Scarola to Col John W. Ripley, 29 April 2002, Hymn subject file, Historical Resources Branch, MCHD.

- Hanson W. Baldwin, “Beginning After End: Our Traditions Upheld, Brightened, America Faces Complicated Tasks,” New York Times, 16 August 1945, 3.

- PFC Gene Shumate, “Poetry in War,” Halls of Montezuma radio show, episode 139, 13 January 1945, Marines’ Hymn file, U.S. Marine Band Library.

- Press release, Halls of Montezuma radio show, November 1942, Command Performance, Correspondence and Radio Program Schedules, March–December 1942, Historical Resources Branch, MCHD.

- “Poetry in War,” Halls of Montezuma radio show.

- “Poetry in War,” Halls of Montezuma radio show.