PRINTER FRIENDLY PDF

EPUB

AUDIOBOOK

Abstract: From 1920 to 1947, the “Marines’ Hymn” was a familiar sound over the radio waves and in motion pictures. Beyond its popular appeal, however, the hymn was scrutinized by Marine Corps leadership under the reforms of Major General Commandant John A. Lejeune, subjected to a prolonged ownership dispute, updated during a world war, and given an official birthday. This article continues the author’s research on the topic and examines these important milestones in the history of the “Marines’ Hymn” and the conflicts that arose as Marine Corps leadership attempted to maintain and promote one dignified official version that would foster a positive public image for the increasingly professional Corps.

Keywords: “Marines’ Hymn,” copyright, Major Joseph C. Fegan Jr., Major General Ben H. Fuller, First Sergeant L. Z. Phillips, Brigadier General Robert L. Denig, Lieutenant General Thomas Holcomb, Marine Corps Aviation

Introduction

The early history of the “Marines’ Hymn,” from mysterious nineteenth-century beginnings to respected anthem of the Marine Corps, culminated in the authorization and copyright of an official version of the song in the summer of 1919, largely due to the efforts of First Sergeant L. Z. Phillips, first leader of the Quantico Post Band.1 While the story of those years focused on the development of the song itself, the next chapter of the hymn’s life was one that saw Marine Corps leadership take a more active role in exerting control over the popular song to help maintain a positive public image for the increasingly professional Corps. Using documents stored at the Marine Band Library in Washington, DC, and the Marine Corps History Division’s Historical Resources Branch at Quantico, Virginia, as a foundation, this article tells the story of the “Marines’ Hymn” from 1920 to 1947. During this time, the hymn was a familiar sound over the radio waves and in motion pictures, and it was a popular topic in local newspapers that offered readers a brief history of the hymn and colorful commentary about its appeal, as seen in one example from July 1934.

When played with a dirgelike cadence the hymn has all the impressiveness of a solemn requiem sung in a vaulted cathedral. Pepped up to modern jazz tempo, it becomes the devil-maycare song of the Leathernecks. . . . The words, which make no pretense to a higher poetical value than mere doggerel, express the spirit of the sea soldiers as only their unknown marine authors could express it.2

In these years, the hymn was also scrutinized under the reforms of Major General Commandant John A. Lejeune, subjected to an ownership dispute, updated during a world war, and given an official birthday. This article examines these important milestones in the history of the “Marines’ Hymn” and the conflicts that arose as Marine Corps leadership attempted to maintain and promote one dignified official version.

Program for MGM’s 1926 film Tell It to the Marines, produced in cooperation with the Marine Corps. Courtesy of the National Museum of the Marine Corps

Major Joseph C. Fegan’s Quest for a Dignified Hymn, 1920–29

In the immediate aftermath of World War I, the Marine Corps was faced with a significantly reduced budget and an American public weary of battles and bloodshed. A large-scale reorganization of the Marine Corps followed, under the leadership of Commandant Lejeune (1 July 1920–4 March 1929). Lejeune’s priorities included fostering a positive public image of the Corps, and throughout the 1920s the “Marines’ Hymn” played a small but consistent role in furthering this goal. In an article celebrating the 150th birthday of the Marine Corps in November 1924, the hymn was used to show the affection Marines had toward the “iron disciplinarians” in the officer ranks. It included the following verse honoring Major General Joseph H. Pendleton, which was said to be sung by “Uncle Joe’s nephews”:

From the Halls of Montezuma

To the shores of Tripoli

We fight our country’s battles

On the land as on the sea.

The Marines in Nicaragua

Were the boys to fill the bill,

And Uncle Joe he was the lad

Took Coyotepe Hill.3

Maj Joseph C. Fegan, appointed the first publicity officer at Headquarters Marine Corps in September 1925. Historical Resources Branch, Marine Corps History Division

In 1926, the hymn was featured in the MGM film Tell It to the Marines, which was produced after Lejeune signed a contract with the studio for “exclusive rights to make all feature pictures of the marines” for one year.4 On 23 September 1927, the Victor Company made a recording of the Marine Band performing the hymn during a tour. The record was made on behalf of Leatherneck magazine and was given as a premium for customers who purchased a three-year subscription. It featured Marine Corps Band leader Captain Taylor Branson singing the first two verses solo, and the entire band singing the final verse.5

In September 1925, Lejeune named Major Joseph C. Fegan as the first Marine Corps publicity officer at Headquarters Marine Corps. In this capacity, Fegan served as the primary point of contact for any matters that could be used for publicity to raise the profile of the Corps.6 On 9 October 1928, Major Fegan sent a memorandum to Lejeune that responded to Lejeune’s inquiries about the origins of the hymn and what role it might play in the future. Fegan highlighted the usefulness of the hymn by recruiters and recommended that the Recruiting Bureau print the verses on a leaflet for general distribution, as well as publish sheet music editions for use by military and civilian bands. In addition, he specified that “on the front cover of the sheet music the story of the hymn could also be told in picture, and on the back cover a short historical sketch of its origin could be placed.” On a broader scale, he recommended that “the origin and history of the hymn be included in the training of recruits, and that every member of the Corps likewise be urged to learn it.”7 Although several printed editions of both the lyrics and music of the hymn had been published before this time, Fegan’s recommendation was fairly innovative. His idea of printing leaflets that would serve the dual purposes of teaching the lyrics and history of the hymn reflected both Lejeune’s goal of raising the public image of the Marine Corps and the increased emphasis on having the Corps research and publish its own history.

In the same memo, Fegan recommended “the inclusion of considerations governing the respect to be shown the hymn by our personnel when it is being sung or played.” Specifically, he argued that “to perpetuate its dignity our personnel should be required to show their respect for it by standing and remaining uncovered when it is sung or played at mass meetings or on official occasions.”8 Anecdotal evidence from the 1910s shows that standing uncovered during the playing of the hymn was already commonplace, but now Fegan sought to make it official protocol.9

Regarding the history of the hymn, Fegan agreed with previous assessments by leaders of the Marine Band that the music was a “steal” from the 1867 edition of the operetta Geneviève de Brabant by Jacques Offenbach. He also included the lyrics of three verses of the “Marines’ Hymn” that he determined were “as nearly the original ones as any.” These verses are recognizable as the ones used today in the official version. One exception was Fegan’s use of “admiration of the nation, we’re the finest ever seen” in the fifth and sixth lines of the first verse, rather than “first to fight for right and freedom, and to keep our honor clean.”10 The “admiration of the nation” line had been the usual lyric in the beginning of the twentieth century, until “first to fight” was incorporated in 1917 during the nationwide recruiting drive at the start of the U.S. involvement in World War I and quickly became the preferred version.11

The remainder of Fegan’s memo addressed the content of the hymn’s lyrics: “Our hymn has become one of the popular patriotic songs and we must keep it on a dignified plane. We cannot permit verses or parodies uncomplimentary to countries in which we have served to be recognized.”12 Although he does not elaborate on this point, he was almost certainly referring to the following verse, which had been circulating for many years:

From the pest-hole of Cavite

To the ditch at Panama,

You will find them very needy

Of marines—that’s what we are.

We’re the watchdogs of a pile of coal,

Or we dig a magazine.

Though our job-lot they are manifold,

Who would not be a Marine?

Major Henry C. Davis claimed credit for writing this verse while stationed at Camp Meyer, Guantánamo Bay, Cuba, in 1911, and it had been included in several publications of the hymn’s lyrics, as early as the 1914 edition of the Publicity Bureau’s pamphlet, The Marines in Rhyme, Prose, and Cartoon.13 It was not included in the 1919 version of the hymn authorized by Major General Commandant George Barnett, and it seemingly fell out of favor during the 1920s.14 The fate of this verse was addressed directly in a Leatherneck article in April 1926 about the history of the hymn:

This verse has been dropped for obvious reasons. Cavite is no longer a “pest hole,” whatever it may have been years ago. The ditch at Panama has been completed for years, and, apart from Coco Solo [U.S. Navy submarine base], there are few Marines in that vicinity. The piles of coal used by the Navy have been largely superseded in recent years by oil tanks, and the verse doesn’t seem to fit present circumstances.15

Fegan’s recommendation to Lejeune echoed this sentiment, and he argued that undignified verses from the past should be dropped from the hymn and new ones should be discouraged in the future. To enforce this position, he further suggested that the hymn should be protected by being granted an official standing within the Corps.

Recommendations: That a regular Marine Corps order be issued on this matter in order that it may have an official standing, thereby protecting it from being subject to ridiculous parodies. The adoption of the three verses as given herein, and that no new verses or parodies be permitted.16

Although Fegan’s desire to have the Marine Corps represented by a song with lyrics on a “dignified plane” was shared by many others, not everyone believed the “Marines’ Hymn” was the right song for the job. In response to Fegan’s memo, Assistant to the Commandant Brigadier General Ben H. Fuller (who went on to serve as Commandant from 9 July 1930 to 28 February 1934) gave a very different opinion about the hymn.

Both the music and the words lack artistic merit and I do not think they should be dignified by formal official recognition. The whole composition is boastful and more appropriate to convivial gatherings than to serious occasions, although suitable enough to be sung by all marines as a marching song and at games. I am not in favor of showing the same respect for it that is shown to a national air, nor do I think it should be called a “Hymn.”17

This negative assessment was likely based on Fuller’s early experiences with the song. In his memo, he acknowledged that he personally heard an earlier version of it aboard the steam screw frigate USS Wabash (1855) in 1892 and he then carried it to the Philippines in 1899, where additional verses were added by various Marines.18 Although the song had been increasingly legitimized in the intervening years, it is understandable that someone from Fuller’s generation would not view it with the same reverence that Major Fegan was now recommending. However, Fegan’s stance on the lyrics prevailed, and on 15 October 1928, a Marine Corps Headquarters bulletin was released stating that the three verses included in Fegan’s memo from the previous week “should be continued without addition or change.”19

Fegan continued to work toward official recognition of the “Marines’ Hymn” and on 1 April 1929, less than one month into Major General Wendell C. Neville’s tenure as Commandant, Fegan sent another memo on this issue. Specifically, after researching the history of the hymn with the Register of Copyrights, he recommended that “the Marines Hymn should be copyrighted in the name of the Major General Commandant.” He argued that this step would give the Marine Corps official ownership of the song, and override the previous copyright of August 1919, done at the instigation of First Sergeant L. Z. Phillips and Leatherneck newspaper, based at Quantico.20 It is unclear whether this recommendation by Fegan was officially acted on. Although 1929 is frequently cited as the year in which the hymn was copyrighted, no documents confirming a copyright registration in 1929 were found in preparation of this article. In addition, when music publishers requested permission to print sheet music copies of the “Marines’ Hymn” in the 1930s and 1940s, the official Marine Corps response was to insist that the credit be given as “Copyright 1919 by U.S. Marine Corps,” with no mention of a 1929 copyright.21

Major General Commandant Neville responded to Fegan’s memo by issuing another authorization of the lyrics, making a minor correction to restore the “first to fight for right and freedom and to keep our honor clean” lyrics in the first verse, which had been officially authorized a decade earlier by Major General Commandant Barnett.22 In addition, he requested that 10,000 copies of the hymn be printed for recruiting publicity as soon as possible, with the first thousand copies to be sent to the leader of the Marine Band.23 This practice of distributing free copies of the music and lyrics became well-known, and several articles advertising the availability of such copies at recruiting offices, and mentioning their popularity among the general public, appeared in local newspapers across the country throughout the 1930s and into the 1940s.24

Major Fegan’s efforts in the late 1920s to adopt a standard version of the song and an equally dignified protocol during its playing reflected Lejeune’s priorities of increased standardization and professionalism throughout the Service. They also reflected Fegan’s own vision of the hymn’s role within the Marine Corps. In part, his recommendations to teach the origin and history of the song during the training of recruits and to adopt the three verses that he described as “nearly the original ones as any” indicate a reverence for history and a desire to return to the earliest version of the song. This could also be the reasoning behind his choice to omit two recent well-known contributions to the hymn. Namely, the “first to fight for right and freedom” lyric in the first verse introduced in 1917 and the verse about the Château-Thierry campaign that had been included in the official 1919 version and continued to appear intermittently for years afterward.25

However, Fegan was also clearly motivated by more contemporary concerns. His stated objection to lyrics with uncomplimentary parodies makes it clear that his choice to omit the “pest-hole of Cavite” verse was based on considerations of public image rather than historical accuracy. When taken together, therefore, Fegan’s recommended version of the hymn’s lyrics—retaining early verses, omitting undignified parodies, and removing references to recent campaigns—may be interpreted less as a desire to return to the hymn’s origins, and more as a push toward a dignified, timeless song that would remain relevant to future generations. Aside from Neville’s directive to restore the “first to fight” lyric, Fegan’s recommendations were adopted, and the verses referencing the “pest-hole of Cavite” and Château-Thierry soon fell out of use. However, Fegan’s concerns about the proliferation of unauthorized parody verses and potential copyright issues pertaining to the hymn were not adequately addressed by the end of the 1920s and they remained points of contention into the 1940s.

Will the Real Owner of the “Marines’ Hymn” Please Stand Up, 1929–42

Major Fegan’s recommendation in 1929 that the hymn should be copyrighted in the name of the Commandant was based on his specific concern “that copyright can be sold, and in case [First Sergeant L. Z.] Phillips, who is now discharged from the Marine Corps, desires to dispose of the copyright [of 1919], it will make it embarrassing for us.”26 Fegan’s worries proved valid, and the issue did indeed result in embarrassment and confusion as Phillips and others staked their claims to the song in the following years. Much of the dispute likely stemmed from confusion about the complexities of copyright law. Specifically, although Phillips had been a driving force behind the copyright and was given official credit for the “words and music,” the copyright certificate registered with the Library of Congress on 19 August 1919 clearly stated that the “Marines’ Hymn” was registered in the name of the U.S. Marine Corps, Quantico, Virginia.27 However, it is unclear if either the Marine Corps or the Commandant, as suggested by Fegan, would have been able to claim legal ownership, since section 7 of the Copyright Act of 1909 stated that “no copyright shall subsist . . . in any publication of the United States Government, or any reprint, in whole or in part, thereof.”28 To be clear, this article makes no assertions about the veracity of any claims pertaining to U.S. copyright law by any of the parties involved; rather, the intent is to offer the arguments of each party as they were originally presented and to show how this prolonged dispute led directly to a change in official Marine Corps policy regarding the use of the hymn.

First Sergeant Phillips served as the first Quantico Post bandmaster from the time of his enlistment at the age of 50 in September 1917 until he was honorably discharged at his own request in May 1922. Before enlisting, he owned the Dutch Mill restaurant in Cleveland, Ohio, a “splendid business that netted him $10,000 a year,” but after leaving the Corps he supported himself and his wife by working at the Southern Music Company and Sacred Music Company in Washington, DC, and with a Marine Corps pension of $30 per month.29 In 1931, he wrote to the office of the Commandant requesting permission “to print and sell copies of the Marines’ Hymn as long as I live” with the acknowledgement that the Marine Corps would own his copyright after his death. He was motivated by financial need, stating “this may help me get a little of the money back I lost in helping Uncle Sam when he was in need; now that I am in need will Uncle Sam help me?”30

In his reply sent 11 August 1931, Major General Commandant Fuller minimized Phillips’s involvement in the 1919 copyright by reaffirming that the copyright was already owned by the U.S. Marine Corps, and that the words and music predated Phillips’s time in the Marines. He also gave formal consent for Phillips to print and sell the song as sheet music, at his own risk and expense, provided that he used the authorized version of the lyrics and included the credit line “Copyright 1919 by U.S. Marine Corps.” More specifically, Fuller stated that “the consent was not exclusive, was not transferrable, and might be revoked at any time.”31 Phillips acted quickly after receiving permission, as seen in a December 1931 article in Metronome magazine:

At last the Marine Hymn, official song of the USMC, has been made available to the public, and it is now on sale generally throughout the US and foreign countries. This was brought about when permission was granted to the compiler, L. Z. Phillips of Washington, to print the famous hymn. He in turn has granted exclusive selling rights as well as mechanical and sound rights to Edward B. Marks. Phillips has been granted special permission to print the stirring song because of his work in compiling it and in unselfishly copyrighting it in the name of the Marine Corps instead of himself. Strict orders from Marine headquarters are that the melody and words must not be distorted in any way since the hymn is sacred and traditional with the US Marines.32

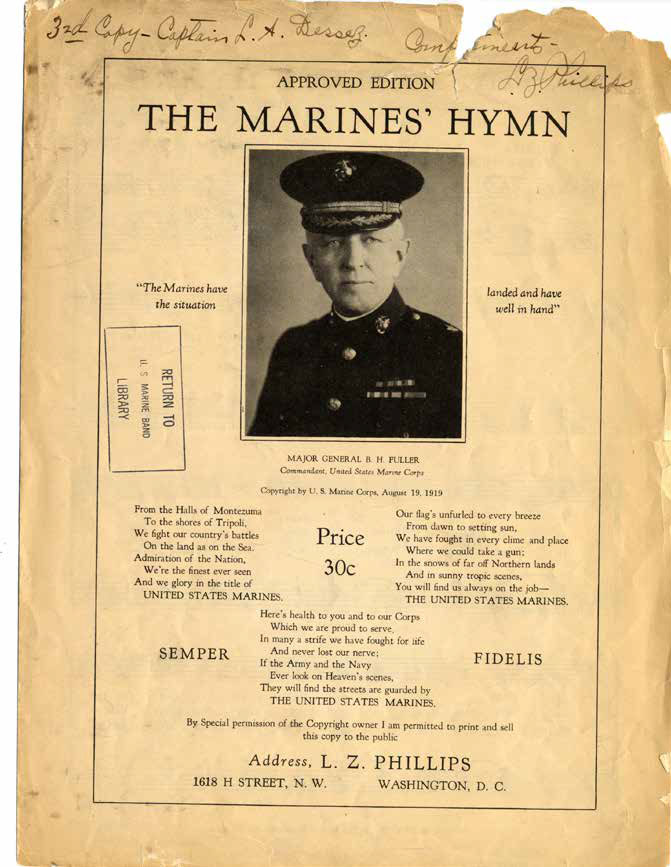

The article’s claim that Phillips was authorized to grant “exclusive selling rights” to a publishing company contradicted Fuller’s letter. The assertion that the hymn was available to the general public “at last” is also confusing, given that multiple versions were printed from 1917 to 1920 and Fuller had recently ordered the production of 10,000 copies to be distributed for recruitment purposes. One copy of sheet music published by Phillips is housed at the Marine Corps Band Library. It is undated, but features a portrait of Major General Fuller on the cover, suggesting that it was printed sometime between August 1931 and the end of Fuller’s tenure as Commandant in February 1934. The credit line “Copyright by the USMC, 19 August 1919” appears as directed, as does the acknowledgement that Phillips printed the edition “by Special permission of the Copyright owner.” The edition cost 30 cents and included the three verses approved by Fuller in 1929 at the request of Major Fegan.

The publishing agreement between the Marine Corps and Phillips hit its first snag when Fuller received a letter dated 30 March 1932 from Russell Doubleday, the vice president of Doubleday, Doran, and Company, regarding the firm’s desire to include the “Marines’ Hymn” in its new publication, The Book of Navy Songs.33 In this letter, Doubleday stated that he was also seeking permission from L. Z. Phillips, who had recently sent a letter to Doubleday in which he asserted that he copyrighted this song at his own expense in the name of the U.S. Marine Corps and called himself the “owner of the copyright.”34 The following day, Fuller sent a stern letter to Phillips, admonishing him for making misleading claims.

This statement that you are the owner of the copyright is not in accordance with the facts. The Marines’ Hymn is copyrighted in the name of the United States Marine Corps and the only interest you have in it is the revocable, non-exclusive permission to print and sell the Hymn as sheet music on your own account. It is requested that you correct the impression you have given Doubleday, Doran and Company in this matter and that you desist from such practice in the future.35

One week later, Major General John T. Myers responded to Doubleday’s request and gave them permission to print the authorized version of the “Marines’ Hymn” and made a point to correct the misinformation the company had been given by Phillips: “With reference to Mr. L. Z. Phillips, the only interest which he has in the Marines’ Hymn is a revocable non-exclusive permission given him by this office in August last to print and sell the hymn as sheet music on his own account.”36 Phillips’s initial reaction to this episode is unknown, but his last act regarding his involvement with the “Marines’ Hymn” three years later can only be seen as in direct defiance of Fuller’s letters from August 1931 and March 1932. To put this action in context, it is important to note that in 1935 Phillips was still experiencing financial difficulties, to the extent that he wrote to Assistant Secretary of the Navy Henry L. Roosevelt for assistance. As a result of this letter, on 13 August 1935, Congressman Martin L. Sweeney (D-OH) introduced bill H.R. 9129 to the first session of the 74th Congress, proposing that Phillips “be appointed a second lieutenant in the Marine Corps and be immediately placed on the retired list with the rank and pay of a second lieutenant.” This action would have increased Phillips’s pension from $30 to $93 per month.37 In response, the Office of the Commandant acknowledged Phillips’s excellent record but denied the request due to its cost to the government of $1,125 per year.38

Only two months later, on 14 October, Phillips signed a document confirming the sale of the copyright of the “Marines’ Hymn” to the Edward B. Marks Music Corporation of New York for the sum of $150. This transaction was officially recorded in the U.S. Copyright Office on 18 October and gave the Marks Corporation ownership of “the musical composition, words and music, entitled ‘The Marines’ Hymn’ written and composed by L. Z. Phillips,” including three copyrighted versions. It further specified that the Marks Corporation would now hold the publishing rights and “all rights to all royalties accruing and all copyrights upon the same, and the right to obtain any and all copyrights for the same and all renewals and extensions thereof.”39

Considering that this document acknowledged that the existing copyright entries for the “Marines’ Hymn” were “in the name of the United States Marine Corps,” it is puzzling that the Copyright Office permitted this transaction to go through with Phillips being listed as the sole legal “assignor.” Also, by 1935, Phillips had been told multiple times by Marine Corps leadership that the copyright was not his to sell, and yet he proceeded to anyway, selling the song that he had once published “through patriotic motives” for a sum equivalent to $2,990 in 2021 money.40 Fortunately for Phillips, his decision appears to have gone unnoticed by the Marine Corps for the remainder of his life, and the permission granted to him to publish copies of the hymn was never revoked.41 He died on 22 August 1936 and was buried with military honors, rendered by a detachment of Marines from the Marine Barracks, Washington, DC, at Arlington National Cemetery three days later.42

Legally or not, by the end of 1935, the Marks Corporation believed itself to be the sole owner of the “Marines’ Hymn” with the right to publish and profit from it as the company saw fit. It had been interested in the hymn for several years by this point, as seen in a letter dated 12 January 1928 from the head of the company, Edward B. Marks, to Captain Taylor Branson, leader of the Marine Band, inquiring about the hymn and its copyright status.43 By December 1931, the Marks Corporation had teamed up with L. Z. Phillips, as noted in the Metronome article quoted above, which stated that Phillips had decided to work with the company “because of its wide and lengthy experience in the field of exploiting and fostering songs without in any way cheapening them.”44 During the next six years, the Marks Corporation registered six copyright entries of various arrangements of the “Marines’ Hymn,” including an arrangement for band, one for vocal quartet and trio, and a fox-trot version credited to L. Z. Phillips.45

The sale of the “Marines’ Hymn” copyright from L. Z. Phillips to the Marks Corporation in October 1935 was brought to the attention of Marine Corps leadership in 1941 by the Pathé News organization. By this time, Pathé had used the “Marines’ Hymn” in several newsreel stories, always with express permission of the Commandant.46 However, in a letter dated 4 June 1941, Herman Fuchs, music editor of Pathé News, informed Brigadier General Alexander A. Vandegrift, Acting Commandant, that an attorney of the Marks Corporation had recently sent a letter to Pathé claiming that “[the Marks Corporation] is the copyright owner of this song through assignment of the full title from L. Z. Phillips. Consequently, they deny ownership by the Marine Corps and demand payment from [Pathé] for having used ‘The Marines’ Hymn’ in connection with Marine Corps stories.”47 Vandegrift responded on 18 June, informing Fuchs that Phillips had been involved with the 1919 copyright and had received permission to publish the song at his own expense in 1931 but had no further claim.48 Armed with this official response, Fuchs sent a stern reply to the Marks Corporation’s attorney, Arthur E. Garmaize, advising him that “it would serve no useful purpose” to continue arguing over the copyright of the hymn, as it had always been in the name of the Marine Corps, “as recognized not only in the Marine Corps’ permission to Phillips of August 11, 1931, to print and sell, but also in Phillips’ assignment to the Edward B. Marks Music Corporation of August [sic October] 14, 1935.” Fuchs further warned that if the Marks Corporation wished to pursue its claim, “in any such fight, we [Pathé] appear to have the backing of the United States Marine Corps.”49

Despite this warning, the copyright issue reared its head once more. In early 1942, Leonard D. Callahan of the Society of European Stage Authors and Composers (SESAC) approached Brigadier General Edward A. Ostermann, adjutant and inspector of the Marine Corps, for permission to publish an arrangement of the “Marines’ Hymn.” During his conversation with Ostermann, Callahan expressed confusion regarding the proper channels for obtaining such permission, since he had heard that the Marks Corporation was claiming exclusive rights to the song and was aggressively defending those rights by collecting royalties from every copy sold by itself and other publishing houses, which Callahan estimated to be more than $20,000 per year.50 In a subsequent letter dated 11 February, he informed Ostermann that the Marks Corporation had recently sent a letter to every radio station in the country “putting them on notice that they, E.B. Marks, are the sole and exclusive copyright owners of the ‘Marines’ Hymn’.”51 This information was corroborated on 12 February, when a sheet music publisher turned congressman, Sol Bloom (D-NY), chairman of the House Foreign Affairs Committee, forwarded a letter to Lieutenant General Commandant Thomas Holcomb that he had received from Herbert E. Marks of the Marks Corporation.

We are the publishers of ‘The Marines’ Hymn,’ official anthem of the Marine Corps. We bought the rights outright sometime ago [1935] from Sergeant L. Z. Phillips, Marine veteran, in whom the copyright was vested. Because the song is enjoying somewhat of a revival of popularity and because we feel inclined to do something to show our appreciation of the stand the Marines are making in the Far East, we wish voluntarily to restore a royalty on every copy sold. As Sergeant Phillips died some years ago, we should like this to be divided equally between his widow and any agency or organization which takes care of the Marine Corps’ families or its entertainment or its veterans. We have inquired and all we have been able to learn so far is that the Navy Relief Society of 90 Church Street in this city is the proper organization.52

In the midst of the wartime mobilization of early 1942, Brigadier General Ostermann found time to formulate a response to this issue within a week that would settle the disagreement once and for all. On 18 February, he submitted a memorandum to Commandant Holcomb detailing the history of the ownership dispute and noting that it had been Marine Corps policy since 1931 “to give permission to music publishing houses to publish the Marines’ Hymn, provided the official version of the hymn is followed and that a credit line is used showing that the publication is by permission of the Marine Corps, the copyright owner.” He also stated that about 20 publishing houses had been given such permission to date.53 Most importantly, Ostermann made the official recommendation “that the Director of Public Relations inform all broadcasting stations and music publishing companies that they are authorized to use the official Marine Corps version of the Hymn without cost.”54 Five days later, on 23 February, Holcomb responded to Congressman Bloom’s letter and made it clear that Ostermann’s recommendation had become official policy. He also noted that the Marks Corporation’s offer to restore the royalties it had collected from previous copies sold was very generous, but that the Marine Corps had no separate organization similar to the Navy Relief Society. Regarding the statement that the Marks Corporation had bought the rights to the hymn from Phillips, Holcomb stated again that the impression that the hymn’s copyright was vested in Phillips was “erroneous” and that it had been in the name of the U.S. Marine Corps since 1919.55 The Marks Corporation appears to have accepted Holcomb’s position, as there is no further correspondence to or from the Marks Corporation in the files, and there is no evidence that the company reasserted its claim to the copyright when it was up for renewal in 1947.

During the next several months, Ostermann corresponded with several music publishing companies to clarify the new Marine Corps policy and reassure those who had previously received cease and desist letters from the Marks Corporation that they were within their rights to publish the song royaltyfree.56 He also reprimanded publishers who were not in compliance with the new policy and acknowledged the complaints of publishers who were frustrated by the sudden proliferation of sheet music editions of the hymn, especially those that undercut the competition by selling for 3 or 4 cents per copy, far below the usual 22 cents per copy.57

The Marine Corps’ new policy of February 1942 ended the struggle over control of the “Marines’ Hymn” by reasserting Marine Corps ownership of the 1919 copyright away from L. Z. Phillips and the Marks Corporation and setting out a clear free use policy. The policy ensured that no third party could control publication rights of the hymn or collect royalties from other publishers by claiming to be the copyright holder. This move was not only in the best interest of the Marine Corps, but it was in step with the mood of a country at war that craved patriotic music. This is illustrated in a New York Times article from December 1942, in which Dr. Joseph Maddy, music professor at the University of Michigan and chairman of the Michigan wartime civic music committee, asserted that “military songs of the armed services were public property in wartime” and promised to “appeal to Washington against private copyright owners.”58 Maddy argued that “there is no more reason why the services should sponsor a privately owned song than a particular brand of soap, cigarette or breakfast food.” While criticizing the private copyright owners of the Army Air Forces song, the “Caisson Song” of the field artillery, and “Semper Paratus” of the Coast Guard for demanding royalties, he notably praised the Marine Corps for making its hymn “readily available” to publishers.59 However, he was likely unaware that it had taken more than a decade of behind-the-scenes frustration for the Marine Corps to officially enact this policy.

Cover of the “Marines’ Hymn” sheet music printed by L. Z. Phillips, ca. 1931–34, featuring a portrait of MajGen Cmdt Ben H. Fuller, who had once criticized the song as “boastful” and “lack[ing] artistic merit.” Marine Band Library

Cover of the “Marines’ Hymn” sheet music printed by the Edward B. Marks Music Corporation in 1942 as a tie-in to the 20th Century Fox film To the Shores of Tripoli. Marine Band Library

“In the Air, on Land and Sea,” November 1942

The “Marines’ Hymn” experienced an upswing in popularity in the aftermath of the attack on Pearl Harbor and the defense of Wake Island in December 1941. Sever al phonograph recordings of the song were advertised, including ones by Kate Smith (Columbia Records), Gene Krupa (Okeh Records), Richard Himber (RCA Victor), the Victor Military Band (RCA Victor), and Tony Pastor (Bluebird Records), and Billboard magazine reported that music machine operators nationwide were being encouraged to work with local movie theaters to promote recordings of the hymn alongside the new 20th Century Fox film To the Shores of Tripoli, which premiered in San Diego on 24 March 1942.60 A special sheet music edition of the “Marines’ Hymn” was also produced by the Marks Corporation as a tiein to the film. At this time, many ordinary Americans also chose to pen their own verses of the hymn to express their support for Marines fighting around the world. Several people sent their verses to Marine Corps Headquarters, and collections of these letters are kept at the Marine Corps History Division and the Marine Corps Band Library. The few responses to these letters included in the collections thank the sender for their contribution and reaffirm the policy of only supporting the official version of the hymn. However, despite the official policy, one unauthorized verse was explicitly approved and promoted. On 17 May 1942, the radio station WJSB in Quantico, Virginia, aired a version of the “Marines’ Hymn” sung by Kate Smith, a highly popular singer whose radio broadcasts went on to sell more than $600 million worth of war bonds throughout the war.61 The version of the “Marines’ Hymn” she sang in May 1942 included the following verse:

When today we hear a call to war,

We have wings to take us there.

With an Ace High Aviation Corps

The Marines are in the air!

And whatever seas our ships may ply,

To whatever distant scenes,

They will find the sky commanded By the United States Marines.62

The following day, Brigadier General Robert L. Denig, director of the newly established Division of Public Relations, wrote to the producers of Halls of Montezuma, a weekly radio program started the previous month by enlisted Marines broadcasting from the Marine Corps base auditorium in San Diego, California. Denig informed them of the debut performance of this verse honoring Marine Corps Aviation and suggested that they use it on their radio program.63 He gave credit to Oscar Hammerstein III for writing the verse, although he clearly meant Oscar Hammerstein II, the famous lyricist and librettist, rather than his future grandson of the same name. Although most famous now for his later partnership with Richard Rodgers on musicals such as Oklahoma! (1943) and The Sound of Music (1959), in early 1942 Hammerstein was at a low point in his career. In 1936, Hammerstein had been a founding member of the Hollywood Anti-Nazi League, and as he watched world events unfold in January 1942, his patriotism was once again stirred, as seen in a letter to his friend, Broadway producer Max Gordon.

I am trying to write a good song that might do something for the nation’s war morale.

I am convinced that all the war songs I have heard so far are on the wrong track.

But I know that there is a great situation for a great song and I am going to

hunt it out—if it takes me a year.64

Within three months of writing this letter, Hammerstein’s verse honoring Marine Corps Aviation was played over the airways. Many amateur lyricists were also inspired by the accomplishments of the Marine Corps aviators.

World War II-era recruitment poster celebrating Marine Corps Aviation. Historical Resources Branch, Marine Corps History Division

BGen Robert L. Denig, director of the Division of Public Relations. Historical Resources Branch, Marine Corps History Division

One submission sent to Marine Corps Headquarters opened with the line “They fought in the air at Midway Isle as well as land and sea,” and another began the second verse with “History is in the making now there’s a big job to be done; but we’ll ‘Keep ’em Flying’ high and wide until victory is won.”65 In July 1942, Charles A. Darr of Mildred, Kansas, went a step further by proposing a formal change to the hymn.

It seems to me that the song should have a place in it for that splendid part

of your organization, the Marine Air Corps. I would suggest a slight change

and addition as follows: “We fight our country’s battles in the air,

on the land and sea.”. . . Our Flying Marines have made such a splendid record,

that we owe them every tribute for what they have done. We might say

“The Marines are flying and have the situation well under wing.”66

One week later, Brigadier General Denig personally responded to Darr’s suggestion, stating, “If an opportunity presents itself to use these lines we shall furnish you with a copy of the publication.”67 He sent another response one week later, stating, “Your suggestion that the Marines’ Hymn should contain a toast to Marine Corps Aviation is certainly very appropriate. You will, no doubt, be interested to know that a new aviation verse was recently introduced by Kate Smith, and approved for release by the Public Relations Division, HQ, USMC.” He also expressed interest in the suggestion of the motto “Marines are flying and have the situation well under wing.”68 Denig’s continued promotion of the recent aviation verse sung by Kate Smith and his unusually personal response to Darr’s ideas indicate his growing support for a change in the hymn’s lyrics to officially honor the contributions of Marine Corps Aviation.

On 7 November 1942, the annual meeting of the 1st Marine Aviation Force Veterans Association, founded by aviation veterans of World War I and a precursor of the Marine Corps Aviation Association, was held in Cincinnati, Ohio. At the meeting, Henry Lloyd Tallman of Albany, Georgia, who had served in Oye, France, as a gunnery sergeant in the 1st Marine Aviation Force, Squadron B, in 1918, “protest[ed] that the air arm was ignored in the ‘Marine Hymn’ [and] persuaded the group to adopt a resolution directed to the commandant urging correction of this unintentional slight.”69 James E. Nicholson, adjutant of the association, conveyed the group’s resolution in a letter to Commandant Holcomb, asserting that “nothing, in our opinion, could do more to recognize and pay tribute to the air arm of our corps, past, present, and future.”70

Holcomb responded favorably to the suggestion, and issued Letter of Instruction 267, stating that on 21 November 1942 he officially approved a change in the fourth line of the first verse of the hymn from “on the land as on the sea” to “in the air, on land and sea.”71 Holcomb sent a personal response to Nicholson to inform him of this change, noting that he was reluctant “to make a change in the historic song but that he was doing so to accord well-merited recognition to the fact that our fields of operation now include the air.”72 A memo from Colonel S. C. Cumming, acting adjutant and inspector to Brigadier General Denig, indicated that an application was being made for a new copyright of the song, and instructed Denig to have the Division of Public Relations print an updated edition.73 It is unclear whether a new copyright was actually registered at this time, but an updated edition was printed and promoted. Denig issued a press release about the lyric change through the Associated Press on 26 November, providing the text of the updated first verse and stating that although many people had suggested similar changes, Commandant Holcomb specifically adopted the version proposed by the 1st Marine Aviation Force Veterans Association.74

Darr, who made the suggestion to add the line “in the air, on the land and sea” in July 1942, sent a follow-up letter in November 1942 to Holcomb to express his pleasure that the change had been officially approved and to take personal credit for it. He also acknowledged his frustration at being repeatedly denied the chance to enlist in the current war based on his age of 62, but was satisfied with calling himself an “Honorary member of the Marines” due to his contribution to the hymn.75

Insignia of the 1st Marine Aviation Force, whose veterans association was credited for proposing the lyric change honoring Marine Corps Aviation in the “Marines’ Hymn.” Historical Resources Branch, Marine Corps History Division

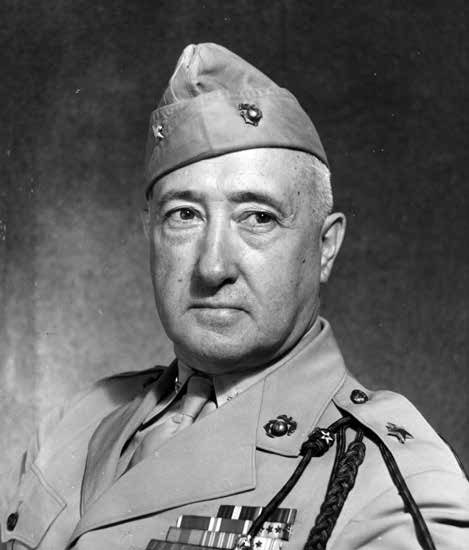

LtGen Cmdt Thomas Holcomb (pictured here as a major general), who authorized the lyric change in the “Marines’ Hymn” to honor Marine Corps Aviation on 21 November 1942. Historical Resources Branch, Marine Corps History Division

A Hundred Years and Counting, 1947

Throughout the war, the impact of the hymn on the American psyche remained strong; more people were inspired to write their own verses and numerous news outlets reported stories that highlighted the hymn’s international notoriety, by both friend and foe, as an important symbol of the American military. A thorough discussion of the role of the hymn during World War II is beyond the scope of this article but deserves to be addressed separately.

The year 1947 marked two significant moments in the history of the “Marines’ Hymn.” First, on 31 December, the original copyright for the hymn that was registered on 19 August 1919 by Phillips and the Marine Corps expired, and the song returned to the public domain. Marine Corps historian Joel D. Thacker called attention to this change in early January 1948, stating in a letter, “Future correspondence must omit any reference to the Marine Corps as copyright owner. In any case where permission is requested to use the Hymn, correspondence granting such permission should suggest that the version considered as official by the Marine Corps should be used.”76

According to a later assistant register of copyrights, the Marine Corps did not renew the initial copyright in 1947 because it was not legally eligible to do so. Specifically, if Phillips had created the work as a private citizen, only he or his successors could have renewed it; but if Phillips had created the work as part of his official duties, “it would have been a publication of the U.S. Government within the meaning of the copyright law, and the USMC could have claimed neither the original copyright nor the renewal copyright.”77 This point was further emphasized in a letter from Master Gunnery Sergeant D. Michael Ressler, chief librarian of the Marine Corps Band Library in 1991: “Copyright law prohibits the United States government from holding any copyright. . . . Early publications of the Marines’ Hymn which gave copyright ownership to the Marine Corps were incorrectly credited.”78 These later statements may provide some legal clarification, to the point of rendering the copyright dispute of the 1930s irrelevant, but they do not negate the fact that the copyright was officially issued in 1919 and that the years of confusion and debate over ownership of the hymn led to a change to Marine Corps policy regarding its use in February 1942.

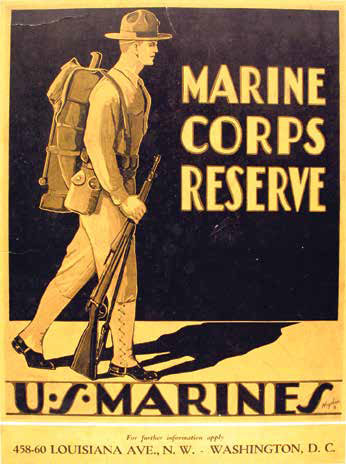

The second significant moment in 1947 was related to the struggles faced by the Marine Corps as a whole immediately following the war. In 1945 and 1946, Marine Corps leadership had to fight for the very existence of the Corps against efforts by members of the War Department and Congress to significantly reduce its strength, until the National Defense Act of 1947 secured its independent status.79 Postwar recruitment was also a serious challenge, especially for the Marine Corps Reserve, as detailed in an article by Captain Dennis D. Nicholson in the Marine Corps Gazette in December 1947.80 Nicholson asserted that although recruitment numbers had been high in the first nine months of 1946, the elimination of key incentives and changes to the G.I. Bill of Rights benefits in July 1947 had caused a steep decline.81 This downward trend was compounded by the fact that a disproportionately high number of enlistments would expire in 1948, meaning that the Recruiting Service needed to procure nearly 80,000 more reservists by 30 January 1948 “to bring our Reserve strength up to the authorized 100,000.”82

Faced with this monumental task, the Marine Corps once again turned to its popular hymn to gain public support, and in early December newspapers around the country announced that Marine Corps Headquarters had designated 7–13 December as “ ‘Marines’ Hymn’ Centennial Week.” The idea shrewdly capitalized on the popular yet unsubstantiated belief that the hymn had first been written in 1847 by an anonymous Marine serving in the Mexican-American War.83 The centennial week, significantly starting on the anniversary of the Pearl Harbor attack, would begin a year in which the hymn would be dedicated “to the new postwar citizen Marine Reserve” and was specifically created to bring attention to the nationwide recruiting drive to build the Marine Corps Reserve to full strength.84 It was an effort to appeal to potential recruits on a more emotional level than could be done by a list of financial and educational benefits.

One article announcing the centennial week noted that “ex-Marines and physically fit young men have an opportunity to share the comradeship of an unusual group. Reservists can join in the words of the hymn and say with thousands of other young men, ‘. . . we are proud to claim the title of United States Marine’.”85

The hymn’s centennial week was meant to be a widespread celebration, with newspapers announcing that “an invitation has been extended to members of the entertainment field and all others who wish to participate in ceremonies for the centennial of the song” that “sparkles with lilt and lift.”86 In answer to this call, the logbook for the Marine Corps Band recorded two performances that week specifically relating to the celebration. On Wednesday, 10 December, their performance of the hymn featuring nine male singers from Catholic University in Washington, DC, was heard over the Mutual Broadcasting System, and on 12 December it was sung during the band’s popular weekly radio program Dream Hour for Shut-ins on NBC.87 More notably, the “Marines’ Hymn Centennial Week” was the subject of the 8 December broadcast of Believe It or Not featuring Robert Ripley on NBC. The 15-minute episode told a fanciful account of the origin of the hymn, in which the impoverished composer Jacques Offenbach impulsively scribbled the musical notation for a military march on the shirt of a beggar in lieu of money. Months later, the story went, Offenbach wanted to use the tune in his new opera, but the clever beggar charged him 7,000 francs for the publication rights. The beggar became a wealthy man, Offenbach’s opera was a success, and that marching song eventually became the “Marines’ Hymn.”88 Given the recent behind-the-scenes copyright dispute over the song, it is fascinating that this spurious account revolved around a fight for ownership between the original composer and a beggar.

Recruitment poster for the Marine Corps Reserve, which was created by an act of Congress on 29 August 1916. Historical Resources Branch, Marine Corps History Division

Conclusion

The story of the “Marines’ Hymn” from 1920 to 1947 is primarily one of Marine Corps leadership taking full ownership of their song and using its popularity to promote a positive public image of the Corps. In some cases, these actions were done behind the scenes, such as the memos generated by Major Fegan in the late 1920s recommending the removal of lyrics that were “uncomplimentary to countries in which we have served” to create a dignified, timeless version of the hymn.89 Others actions, such as the protracted 87 Marine Corps Band log book, 10 and 12 December 1947, U.S. Marine Band Library. 88 Transcript of Believe It or Not featuring Robert Ripley, episode 151, sketch: “Marine Hymn,” 8 December 1947, Marines’ Hymn file, U.S. Marine Band Library. 89 Fegan memo to Lejeune. copyright dispute of the 1930s, were primarily about control of the use of the hymn but had the unexpected benefit of broadening its reach, by resulting in a policy that allowed anyone free use of the authorized, properly credited version. Other decisions were much more public, such as the celebration of the hymn’s centennial week in conjunction with a massive recruiting drive, and the most well-known episode from this time: the lyric change to “in the air, on land and sea” on 21 November 1942. This was the last official change to the “Marines’ Hymn” to date and, similar to the addition of “first to fight for right and freedom” during World War I, it was done to reflect one of the strongest aspects of the Marine Corps’ public image. Marine Corps Aviation was not a new concept in 1942, but it loomed large in the minds of Americans as events in the Pacific theater unfolded, and it is unsurprising that so many people independently suggested lyrics for the hymn that would honor the accomplishments and sacrifices of the aviators involved. The Division of Public Relations approved this idea by promoting the verse written by Oscar Hammerstein II and sung by Kate Smith. When the official change was approved, the division gave credit to the 1st Marine Aviation Force Veterans Association for the new lyric but made it clear that the change was meant to be inclusive “to give deserved recognition to the air arm of the corps as a whole not because of any special action performed by any certain unit or units.”90

By the end of this period, the hymn could no longer be trivialized or dismissed as “boastful” or “devil-maycare.” It had served as inspiration and comfort through the largest war in history, to both Marines and civilians alike, and its popularity showed no signs of waning.

•1775•

Endnotes

- For the first part of this investigation into the history of the hymn, see Lauren Bowers, “A Song with ‘Dash’ and ‘Pep’: a History of the ‘Marines’ Hymn’ to 1919,” Marine Corps History 6, no. 2 (Winter 2020): 5–22, https:// doi.org/10.35318/mch.2020060201.

- Loren T. Casey, “Sea Soldiers’ Song Is Mystery Ballad,” Everett Press (Everett, PA), 20 July 1934, 4.

- John Dickenson Sherman, “U.S.M.C.,” Press Herald (Pine Grove, PA), 31 October 1924, 6.

- “Gets Sole Rights to Film Marines,” New York Times, 2 February 1926, 7.

- Capt Taylor Branson to Edward B. Marks, 14 January 1928, Hymn subject file, Historical Resources Branch, Marine Corps History Division (MCHD), Quantico, VA; and List of Marine Corps Band recordings, Marines’ Hymn file, U.S. Marine Band Library, Washington, DC.

- Colin Colbourn, “Esprit de Marine Corps: The Making of the Modern Marine Corps through Public Relations, 1898–1945” (PhD diss., University of Southern Mississippi, 2018), 152.

- Maj Joseph C. Fegan, memo to MajGen Cmdt John Lejeune, 9 October 1928, Hymn subject file, Historical Resources Branch, MCHD, hereafter Fegan memo to Lejeune.

- Fegan memo to Lejeune. The term remaining uncovered refers to removing hats or covers.

- R. B. Stuart to Victor Talking Machine Company, 17 May 1918, Marines’ Hymn file, U.S. Marine Band Library; and Letter from Lt Merritt Edson, Springfield (VT) Reporter, 1 August 1918, 6.

- Fegan memo to Lejeune.

- For more information about the addition of “first to fight” to the hymn, see Bowers, “A Song with ‘Dash’ and ‘Pep’,” 12–14.

- Fegan memo to Lejeune.

- The Book of Navy Songs (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 1930), 126–27; and The Marines in Rhyme, Prose, and Cartoon, 2d ed. (New York: U.S. Marine Corps Recruiting Publicity Bureau, 1914–15), 4, Hymn subject file, Historical Resources Branch, MCHD.

- The Marines’ Hymn (Quantico, VA: Leatherneck, 1919), box 54, M1646, LCCN 2014561867, Library of Congress, Washington, DC.

- Hash Mark, “Whence Came the Marine’s Hymn?,” Leatherneck, 10 April 1926, 1.

- Fegan memo to Lejeune.

- AstCmdt Ben Fuller, memo to MajGen Cmdt John Lejeune, 11 October 1928, Marines’ Hymn file, U.S. Marine Band Library, hereafter Fuller memo to Lejeune.

- Fuller memo to Lejeune.

- Headquarters bulletin, 15 October 1928, Hymn subject file, Historical Resources Branch, MCHD.

- Maj Joseph C. Fegan, memo to the MajGen Cmdt Wendell Neville, 1 April 1929, Marines’ Hymn file, U.S. Marine Band Library, hereafter Fegan memo to Neville.

- The first known example of this wording is in a letter from MajGen Cmdt Ben Fuller to L. Z. Phillips, 11 August 1931, quoted in MajGen Cmdt (acting) A. A. Vandegrift to Mr. Herman Fuchs, Pathé News, 18 June 1941, Hymn subject file, Historical Resources Branch, MCHD, hereafter Vandegrift letter to Fuchs.

- MajGen Cmdt Wendell Neville to the Officer in Charge, Marine Corps Recruiting Bureau, Philadelphia, 24 April 1929, Hymn subject file, Historical Resources Branch, MCHD, hereafter Neville letter to Recruiting Bureau, Philadelphia.

- Neville letter to Recruiting Bureau, Philadelphia.

- Casey, “Sea Soldiers’ Song Is Mystery Ballad,” 4; “Who Wants Free Copy of U.S. Marine Hymn?,” Courier-Post (Camden, NJ), 25 June 1936, 33; and Sgt Richard C. Seither, “Marine Corps Hymn,” Tensas Gazette (Saint Joseph, LA), 6 March 1942, 1.

- Later references to this verse include Second Leader of Marine Corps Band to Mr. Andrew Ontke, 28 March 1924, Marines’ Hymn file, U.S. Marine Band Library; and “Legation Guard News,” 1930 Legation Guard Annual, Beijing, China, Hymn subject file, Historical Resources Branch, MCHD.

- Fegan memo to Neville.

- L. Z. Phillips, “The Marine’s Hymn,” Certificate of Copyright Registration, Copyright Office of the U.S., Library of Congress, E 457132, 19 August 1919, Marines’ Hymn file, U.S. Marine Band Library. For more information about the 1919 copyright, see Bowers, “A Song with ‘Dash’ and ‘Pep’,” 18–21.

- Copyright Act of 1909: An Act to Amend and Consolidate the Acts Respecting Copyright, Pub. L. No. 60-349, 35 Stat. 1075 (1909).

- Arthur Tregina, “How the Popular Post Band Was Recruited and Formed,” Quantico Leatherneck 1, no. 12 (9 February 1918): 3; as quoted in MajGen Cmdt Ben H. Fuller to L. Z. Phillips, 31 March 1932, Marines’ Hymn file, U.S. Marine Band Library; and To Appoint L. Z. Phillips a second lieutenant in the Marine Corps, H.R. 9129, 74th Cong. (1935), hereafter H.R. 9129.

- Quoted in BGen Edward A. Ostermann, memo to LtGen Cmdt Thomas Holcomb, 18 February 1942, Marines’ Hymn file, U.S. Marine Band Library, hereafter Ostermann memo to Holcomb.

- Quoted in Ostermann memo to Holcomb; and quoted in Vandergrift letter to Fuchs.

- “Marks Gets Marine Hymn,” Metronome, December 1931, 33, Hymn subject file, Historical Resources Branch, MCHD, hereafter “Marks Gets Marine Hymn.”

- Russell Doubleday to MajGen Cmdt Ben Fuller, 30 March 1932, Marines’ Hymn file, U.S. Marine Band Library, hereafter Doubleday letter to Fuller.

- Doubleday letter to Fuller.

- MajGen Cmdt Ben Fuller to L. Z. Phillips, 31 March 1932, Marines’ Hymn file, U.S. Marine Band Library.

- MajGen J. T. Myers to Doubleday, Doran, 6 April 1932, Hymn subject file, Historical Resources Branch, MCHD.

- H.R. 9129.

- MajGen Cmdt John Russell to Judge Advocate General, 17 August 1935, Marines’ Hymn file, U.S. Marine Band Library.

- L. Z. Phillips to Edward B. Marks Music Corporation, Assignment of Copyright (E457132, E29678, E29679), Copyright Office of the U.S., 18 October 1935, Marines’ Hymn file, U.S. Marine Band Library.

- Post Cmdr, Quantico, John T. Myers to MajGen Cmdt George Barnett, 18 June 1919, as quoted in a memo to Gen Lane, 2 April 1929, Hymn Subject File, Historical Resources Branch, MCHD. The equivalent value of the copyright sale was calculated using U.S. Inflation Calculator, accessed 24 August 2021.

- Ostermann memo to Holcomb.

- SgtMaj W. T. Ramberg, memo to Maj R. H. Jeschke, 25 August 1936, L. Z. Phillips, U.S. Marine Corps service record, Marines’ Hymn file, U.S. Marine Band Library.

- Edward Marks to Capt Taylor Branson, 12 January 1928, Hymn Subject File, Historical Resources Branch, MCHD.

- “Marks Gets Marine Hymn.”

- “Fact Sheet Q & A,” unpublished paper, 1976, Hymn subject file, Historical Resources Branch, MCHD, hereafter “Fact Sheet Q & A.”

- Fred Doerr to Sam Fox, 28 April 1941, Marines’ Hymn file, U.S. Marine Band Library.

- Herman Fuchs to MajGen Cmdt (acting) A. A. Vandegrift, 4 June 1941, quoted in “Fact Sheet Q & A.”

- Vandegrift letter to Fuchs.

- Herman Fuchs to Arthur Garmaize, 7 July 1941, quoted in Herman Fuchs to Commandant A. A. Vandegrift, 7 July 1941, Marines’ Hymn file, U.S. Marine Band Library.

- Quoted in Ostermann memo to Holcomb.

- Leonard Callahan to BGen Ostermann, 11 February 1942, Marines’ Hymn file, U.S. Marine Band Library.

- Quoted in LtGen Cmdt Thomas Holcomb to Hon Sol Bloom, 23 February 1942, Marines’ Hymn file, U.S. Marine Band Library, hereafter Holcomb letter to Bloom.

- Ostermann memo to Holcomb.

- Ostermann memo to Holcomb.

- Holcomb letter to Bloom.

- BGen Edward Ostermann to Manhattan Publications, 30 April 1942, Hymn subject file, Historical Resources Branch, MCHD; BGen Edward Ostermann to Morris Music Company, 31 July 1942; and Morris Music Company to BGen Edward Ostermann, 3 August 1942, Marines’ Hymn file, U.S. Marine Band Library.

- Eugene Warner to BGen Edward Ostermann, 28 July 1942, Marines’ Hymn file, U.S. Marine Band Library.

- “Fights Private Fees on Military Songs: Michigan Music Teacher Says Public Owns Service Tunes,” New York Times, 18 December 1942, 16.

- “Fights Private Fees on Military Songs,” 16.

- “Picture Tie-ups for Music Machine Operators,” Billboard 54, no. 32 (28 March 1942): 116.

- Frank G. Prial, “Kate Smith, All-American Singer, Dies at 79,” New York Times, 18 June 1986, 1.

- “Fact Sheet Q & A”; and 1stLt W. N. Gibson to Charles E. Goodman, 22 May 1942, Marines’ Hymn file, U.S. Marine Band Library.

- BGen Robert Denig to Capt Harry Maynard, 18 May 1942, Command Performance, Correspondence and Radio Program Schedules, March– December 1942, Historical Resources Branch, MCHD.

- Hugh Fordin, Getting to Know Him: A Biography of Oscar Hammerstein II (Boston, MA: Da Capo Press, 1995), 141, 175–76.

- Thomas Plummer to BGen Robert Denig, 25 February 1942; and Rosalind Wade to W. F. Santelmann, 29 June 1942, Marines’ Hymn file, U.S. Marine Band Library.

- Charles Darr to LtGen Cmdt Thomas Holcomb, 7 July 1942, Hymn subject file, Historical Resources Branch, MCHD.

- BGen Robert Denig to Charles Darr, 14 July 1942, Marines’ Hymn file, U.S. Marine Band Library.

- BGen Robert Denig to Charles Darr, 20 July 1942, Marines’ Hymn file, U.S. Marine Band Library.

- Henry L. Tallman, U.S. Marine Corps Muster Rolls, 1893–1958, Rolls 145–156 (Historical Resources Branch, MCHD); and “Alteration Made in Marine Anthem: First Verse Revamped to Give Recognition to Troops in Air Branch,” Baltimore (MD) Sun, 27 November 1942, 4, 28, hereafter, “Alteration Made in Marine Anthem.”

- “Alteration Made in Marine Anthem,” 28.

- LtGen Cmdt Thomas Holcomb, Letter of Instruction 267, 25 November 1942, Hymn subject file, Historical Resources Branch, MCHD.

- “Alteration Made in Marine Anthem,” 4; and James E. Nicholson to LtGen Cmdt Thomas Holcomb, 24 November 1942, Marines’ Hymn file, U.S. Marine Band Library.

- Col S. C. Cumming memo to BGen Robert Denig, 25 November 1942, Marines’ Hymn file, U.S. Marine Band Library.

- “Alteration Made in Marine Anthem,” 28.

- Charles A. Darr to LtGen Cmdt Thomas Holcomb, 28 November 1942, Marines’ Hymn file, U.S. Marine Band Library.

- Joel Thacker to Whom It May Concern, 10 January 1948, Hymn subject file, Historical Resources Branch, MCHD.

- Waldo H. Moore to Office of Naval Research, 4 August 1977, Hymn subject file, Historical Resources Branch, MCHD. Section 23 of the Copyright Act of 1909 addresses the issue of copyright renewal.

- Mike Ressler to Sgt Kathleen Roost, 1 November 1991, Marines’ Hymn file, U.S. Marine Band Library.

- Robert D. Heinl Jr., Soldiers of the Sea: The United States Marine Corps, 1775–1962 (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 1962), 514–18.

- Capt Dennis D. Nicholson Jr., “Recruiting—First Service of the Corps,” Marine Corps Gazette 31, no. 12 (December 1947): 33–41. See also Sgt Edward J. Evans, “Reserve Power,” Leatherneck, October 1947, 3–5.

- Originally established to provide services and benefits to the veterans of World War II, the Servicemen’s Readjustment Act of 1944, a.k.a. the G.I. Bill of Rights, was signed by Franklin D. Roosevelt on 22 June 1944. S. 1776, 78th Cong., 2d Sess. (7 February 1944).

- Nicholson, “Recruiting—First Service of the Corps,” 34.

- For more information about the nineteenth-century origins of the hymn, see Bowers, “A Song with ‘Dash’ and ‘Pep’,” 6–8.

- “Marine Corps Hymn Centennial Week to Be Observed,” Visalia (CA) Times-Delta, 6 December 1947, 2; “Marine Corps Marks 100th Year of Hymn,” Cumberland (MD) Sunday Times, 7 December 1947, 53; “Song for Men: Marine Corps Hymn Chanted 100 Years Old,” Decatur (AL) Daily, 7 December 1947, 3; and “Marine Hymn Marks 100th Anniversary,” Kingsport (TN) News, 8 December 1947, 4.

- “Marine Hymn Marks 100th Anniversary,” 4.

- “Marine Corps Hymn Centennial Week to Be Observed,” 2.

- Marine Corps Band log book, 10 and 12 December 1947, U.S. Marine Band Library.

- Transcript of Believe It or Not featuring Robert Ripley, episode 151, sketch: “Marine Hymn,” 8 December 1947, Marines’ Hymn file, U.S. Marine Band Library.

- Fegan memo to Lejeune.

- Freling Foster, telegram to U.S. Marine Corps Division of Public Relations, 10 January 1943; Maj George Van Der Hoef to Freling Foster, 11 January 1942 [sic –1943], Marine Corps Hymn Correspondence, January 1943–August 1946, Historical Resources Branch, MCHD.