Abstract: Only two weeks after the fall of Saigon in May 1975, Khmer Rouge forces seized the American merchant ship SS Mayaguez (1944) off the Cambodian coast, setting up a Marine rescue and recovery battle on the island of Koh Tang. This battle on 12–15 May 1975 was the final U.S. military episode amid the wider Second Indochina War. The term Vietnam War has impeded a proper understanding of the wider war in the American consciousness, leading many to disassociate the Mayaguez incident from the Vietnam War, though they belong within the same historical frame. This article seeks to provide a heretofore unseen historical argument connecting the Mayaguez incident to the wider war and to demonstrate that Mayaguez and Koh Tang veterans are Vietnam veterans, relying on primary sources from the Ford administration, the papers of the Vietnam Veterans Memorial Fund, and interviews with veterans.

Keywords: Vietnam, Cambodia, veterans, memory, Mayaguez, the Wall, Vietnam Veterans Memorial Fund, Koh Tang, Koh Tang Mayaguez Veterans Organization, Gerald R. Ford, Henry A. Kissinger, James R. Schlesinger, U.S. Marine Corps, Admiral Noel A. M. Gayler

Sometimes regulation fails to match reality. “What are you wearing?!” the indignant colonel demanded while poking the lance corporal’s chest. In the fall of 1975, young Timothy W. Trebil had a problem after arriving in Quantico, Virginia, from Okinawa for temporary duty—but it was not clear why as he stood locked at attention.

“Sir, the lance corporal is wearing his—”

“No. I’m talking about that ribbon!”

It was Trebil’s Purple Heart. He earned it earlier that May during the SS Mayaguez container ship rescue, only two weeks after South Vietnam’s collapse. The Cambodian Khmer Rouge shot down Trebil’s helicopter in May 1975 as it attempted to land assaulting U.S. Marines on Koh Tang Island, where the ship’s crew was supposedly captive. With second-and third-degree burns, Trebil floated out to sea before being scooped up by a supporting U.S. Navy ship. The Purple Heart was the only ribbon he rated, a highly unusual circumstance for a junior enlisted Marine in 1975. After Trebil hastily spurted an explanation justifying his Purple Heart, the colonel redirected his fire at what was missing: “Nobody wears that ribbon by itself. Nobody rates just that ribbon— wait here.” He took Trebil’s service record brief, the proof of his existence in the Corps, and stormed off to remedy the situation.1

President Dwight D. Eisenhower authorized the National Defense Service Medal (NDSM) in Executive Order 10448 on 22 April 1953 as a blanket recognition medal for military personnel serving at a time of national emergency, though not necessarily in a combat zone.2 According to the 1973 Paris Peace Accords, U.S. combat operations in Vietnam ended on 28 January 1973, but the Department of Defense (DOD) kept issuing the NDSM to servicemembers for the national emergency of the Vietnam War until 14 August 1974. Trebil joined the Marine Corps in September 1974, missing the regulatory cutoff date. The incongruity between Trebil’s combat experience, exemplified by the Purple Heart, and the absence of other awards for wartime or emergency service troubled the colonel. Although existing regulations said Trebil had not served during a period of national emergency, the colonel reconciled the regulation’s intent with Trebil’s experience through an impromptu award ceremony at the Marine Corps Commandant’s office. Now Trebil had two ribbons to his name: the Purple Heart and NDSM.3

Official U.S. Air Force photo 090424-F-1234P-028, courtesy of the National Museum of the U.S. Air Force

Unidentified U.S. Marines run from a Sikorsky HH-53C Jolly Green Giant helicopter of the 40th Aerospace Rescue and Recovery Squadron during the assault on Koh Tang Island to rescue the U.S. merchant ship Mayaguez and its crew, 15 May 1975.

Popular conception, national narratives, and wartime decoration regulations do not always match individual historical experiences. In addition to not warranting the NDSM, the fighting on and around Koh Tang—contested by the new revolutionary governments of Vietnam and Cambodia—from 12 to 15 May 1975 also failed to merit the green, yellow, or red Vietnam Service Medal (VSM). Perhaps the most iconic ribbon from the United States’ nearly 20-year military effort in Indochina, the image of the VSM now adorns countless black Vietnam veteran hats, jackets, and memorials across the United States and serves as a prominent discriminator between those who fought in-country in Vietnam and those who did not.4

In a narrowly defined policy, service in the Mayaguez rescue operation alone did not warrant the VSM because combat operations ceased in 1973 and President Gerald Ford had officially proclaimed the Vietnam War over five days before the ship’s seizure.5 More than 58,000 American servicemembers and hundreds of thousands of Vietnamese, Cambodians, Laotians, and others lost their lives during what the United States calls the Vietnam War. But wars are rarely contained neatly within dates and borders, and the Vietnam War extended outside the geographical borders of Vietnam.

Official U.S. Air Force photo, courtesy of the National Museum of the United States Air Force

Container ship SS Mayaguez.

The battle on and around Koh Tang to rescue the Mayaguez and its crew on the border between Cambodia and Vietnam was the U.S. military’s final episode amid a concurrent wider war for control of Indochina—known as the Second Indochina War. France’s colonial exit from Indochina after the 1954 Geneva Conference triggered struggles for control across the region.6 The United States’ main military effort in the Second Indochina War was the fighting in Vietnam, but the term Vietnam War has hindered a proper understanding of the wider war in the American consciousness. Governments, institutions, and historians frame events for various reasons, among them political, bureaucratic, and a desire for coherence. The most valid reasons for placing the Vietnam War and the Mayaguez incident within the same frame are historical. U.S. military participation within Vietnamese and Cambodian territory in spring 1975 was participation in the same war, not separate conflicts. U.S. decision-makers and military leaders in the region understood this at the time and participants in the Mayaguez incident at various levels remembered and memorialized the connection in the following years.7 This article will first review the military and diplomatic events in South Vietnam and Cambodia during the winter and spring of 1975 and comment on existing interpretations. Next, the article will explain why some view the Mayaguez incident as distinct from the Vietnam War/Second Indochina War for political, bureaucratic, and social reasons before demonstrating historical and national memory linkages. This article provides a heretofore unseen historical argument connecting the Mayaguez incident to the wider war and demonstrates that Mayaguez and Koh Tang veterans are Vietnam veterans.

Official Department of Defense photo, courtesy of Historical Resources Branch, Marine Corps History Division

A Marine and an Air Force pararescueman of the 40th Aerospace Rescue and Recovery Squadron (in wetsuit) run for an Air Force helicopter during an assault on Koh Tang Island to rescue the merchant ship SS Mayaguez and its crew, 15 May 1975.

Official Department of Defense photo, by YN3 Michael Chan, courtesy of Historical Resources Branch, Marine Corps History Division

A U.S. Marine from the escort ship USS Harold E. Holt (DE 1074) storm the merchant ship SS Mayaguez to recapture the ship and to rescue the captive crew. No one was aboard the ship and the crew were later returned by a fishing boat.

Indochina, 1975

As the calendar turned from 1974 to 1975, the situation across Indochina—Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia—appeared grim for governments allied with the United States. Opposing regimes within each country, under the mantle of Communism (though not Moscow or Beijing stooges as many believed), made significant gains in their decades-long struggles for control of independent nation states derived from the former French Indochina. Two dominoes teetered by the end of March. In the face of the advancing Khmer Rouge, the United States evacuated personnel from Phnom Penh, Cambodia’s capital, in Operation Eagle Pull on 12 April. Similarly, with North Vietnamese armored columns closing in, the United States evacuated Saigon in Operation Frequent Wind on 30 April. It seemed the last helicopter lift brought finality—bitter for many, inglorious at best—to nearly 20 years of American military presence in embattled Indochina.8

Twelve days after the rooftop dust settled in Saigon, and five days after President Ford officially ended the Vietnam era, Khmer Rouge soldiers captured the Mayaguez and its 40-person crew.9 Ford again ordered U.S. forces to battle in Indochina. Portions of two U.S. Marine battalions, supported by Navy and Air Force elements, assaulted both the Mayaguez and Koh Tang Island in the early morning hours of 15 May 1975. Precombat intelligence reports judged Koh Tang to be lightly defended, yet a disciplined and heavily armed element of the Khmer Rouge numbering in the hundreds stiffly resisted. The Cambodians released the crew unharmed from another location back to U.S. ships shortly after the Marine insertion. The Mayaguez was unguarded. But tragically, by the time the Marines on the island received this report, several helicopters lay burning in the water and some Marines had already given their lives. The mission switched from rescue to withdrawal, but this proved difficult under heavy fire and with the now-limited number of helicopters available. As the withdrawal stretched into the hours of darkness, personnel accountability became more challenged. After 14 hours of ground combat and 41 servicemembers killed in action, U.S. forces recovered the Mayaguez and its entire crew. Given the intensity of the fighting and the difficult withdrawal conditions, many of the fallen remained on the island or in the surf. Hauntingly, three Marines may have been left on the island alive; they remain officially unaccounted for.10

Raymond Potter Collection, COLL/1088, Historical Resources Branch, Marine Corps History Division

Maj Raymond Potter raising the American flag on the SS Mayaguez after its recapture by U.S. Marines.

Last Battle or First Post-Vietnam Battle?

The Mayaguez incident exists on a historical fault line: Was it part of the Vietnam War or a post-Vietnam operation? In general, scholars writing about the end of the Vietnam War conclude with the 30 April 1975 fall of Saigon and perhaps a mention of fleeing South Vietnamese boat people, but no mention of the Mayaguez capture. Meanwhile, several Mayaguez historians refer to the rescue operation as the “last battle” of Vietnam, but without providing any justification.

None of the academy’s reputed comprehensive diplomatic histories of the Vietnam War conclude with the Mayaguez incident. George C. Herring discusses events in Laos and Cambodia after Saigon’s fall but does not mention the incident; neither do Lewis Sorley, Michael Lind, or Robert McMahon. Editor David L. Anderson includes it in the Columbia Guide to the Vietnam War on an extended time line of U.S. involvement with Vietnam that stretches to U.S. diplomatic recognition of Vietnam in 1995, but without comment about its inclusion. However, Anderson does not mention it in The Columbia History of the Vietnam War, which includes a chapter by Kenton Clymer titled “Cambodia and Laos in the Vietnam War.” LienHang T. Nguyen’s history of the war from Hanoi’s perspective includes discussion of diplomatic squabbling between the North Vietnamese and Communist parties in Laos and Cambodia but overlooks the incident. Even Mark Atwood Lawrence’s international history of the war, which includes discussion of the Khmer Rouge takeover in Cambodia, fails to mention it.11

The Mayaguez incident is mentioned in histories of Henry Kissinger’s tenure as the United States’ premier foreign policy maker but never as an event with direct connection to Vietnam, despite the earlier distinction of being credited (alongside Richard Nixon) for expanding the war into Cambodia. Robert D. Schulzinger’s and Jussi Hanhimäki’s research into Kissinger imply the Mayaguez operation was simply a post-Vietnam opportunity for Ford and Kissinger to forcefully save face after Saigon’s fall. Likewise, John Robert Greene’s and Douglas Brinkley’s Ford biographies liken the ship’s capture to a post-Vietnam foreign policy challenge more akin to the 1968 North Korean USS Pueblo (AGER 2) seizure than with any direct linkage to Vietnam.12

There is also no consensus on the question in focused historical accounts of the incident. Several of these works place it outside the Vietnam War. Time journalist Roy Rowan’s The Four Days of Mayaguez came off the presses two months after the events on Koh Tang, yet it speaks of the Vietnam War in the past tense. Christopher J. Lamb’s 1989 work, Belief Systems and Decision Making in the Mayaguez Crisis, suggested Ford’s military response had more to do with Northeast Asia and North Korean provocations than recent events in Southeast Asia. Lucien S. Vandenbroucke recognized the connection to broader Indochinese troubles but does not place it within the war as the United States’ prior actions in Vietnam. James Wise and Scott Baron emphasized linkages to the Pueblo and modern piracy.13 Robert Mahoney splits the difference, referring to it as both “the last chapter of the United States’ military involvement in Indochina” and “the first direct foreign challenge to American power since the end of the Vietnam War.”14

Others characterize the incident clearly as Vietnam’s last battle. George Dunham and David Quinlan, writing the Marine Corps’ official history of the Vietnam War in 1990, included it as the final chapter. John Guilmartin, a pilot in one of the U.S. Air Force units that supported the operation from Thailand and later a distinguished historian, referred to it explicitly as the “last battle” of Vietnam. Both Guilmartin and Ralph Wetterhahn, the author of a more recent book titled Last Battle: The Mayaguez Incident and the End of the Vietnam War, neglected to justify their claims. Similarly, another former pilot, Ric Hunter, who flew a McDonnell Douglas F-4D Phantom aircraft as part of operations over Vietnam and in support of the Mayaguez, penned several journal articles within the past two decades making the connection. Most recently, Lamb opened his 2018 study of the incident’s mission command and civil-military relations aspects by also explicitly calling it the last battle.15

Policy, Bureaucracy, and Social Reasons to Separate the Mayaguez from Vietnam

Three significant factors hinder the connection between the Mayaguez operation and the Vietnam War from being more broadly recognized: the contemporary national policy context, bureaucratic inertia, and the protected social status of being a Vietnam veteran. Neither President Ford nor Congress had any policy desire to claim to be continuing the Vietnam War in May 1975. Likewise, the DOD resisted the connection in its award eligibility policy for the VSM. In addition, protection of the classification Vietnam veteran as a distinguished status caused some veterans to resist a wider interpretation of the war.

It is no revelation that U.S. public support for Vietnam combat waned in the 1970s.16 By 1972, President Richard Nixon yearned to be publicly recognized as a Vietnam peacemaker while Kissinger negotiated U.S. withdrawal. Privately, both men doubted South Vietnam’s ability to withstand future North Vietnamese aggression and hoped at least a “decent interval” would pass after the January 1973 Peace Accord before South Vietnam succumbed.17 This transpired under the hanging pall of corruption during the Watergate investigation and Vice President Spiro Agnew’s resignation in October 1973. Meanwhile, the House of Representatives and Senate overrode Nixon’s veto to enact the War Powers Resolution in November 1973 and rein in perceived presidential war-making excesses.18 Gerald Ford, then House minority leader, entered within this setting, backing into the vice presidency in 1973 and later the presidency in August 1974.

Ford pledged to continue an American peace moment as war escalated across Indochina. Upon taking the presidential oath of office in August, he promised an “uninterrupted and sincere search for peace” while acknowledging his predecessor had “brought peace to millions.”19 By the dawn of 1975, as North Vietnamese columns began the final decisive push south, the interval Ford inherited from Nixon was closing rapidly. As South Vietnamese resistance crumbled, Ford argued with Congress for funds but not troops. Historians can argue whether this advocacy was in earnest or part of the political blame game between the executive and legislative branches for South Vietnam’s approaching defeat.20 Privately, Ford and his advisors sought a way to frame the situation in a positive light.

Shedding the Vietnam War was desirable not only for political reasons but also for financial considerations. As early as January 1975, before South Vietnam’s collapse was imminent or a foregone conclusion, Ford’s domestic advisors debated when he should declare an official end date to the conflict to save money on costly wartime veterans’ benefits. Although U.S. combat operations supposedly ceased in 1973, no counterpart proclamation to Lyndon B. Johnson’s 1965 Executive Order No. 11216, which designated Vietnam as a combat zone, had been issued to end the war.21 Ford’s domestic policy team weighed these considerations. Domestic advisor James M. Cannon’s handwritten musing on a memorandum in January 1975 “April 1st good time to end the Vietnam War?” makes the point. As things looked worse for South Vietnam in early 1975, the driving considerations to disassociate from the war were political and financial.22

As South Vietnam’s collapse became imminent in April, Ford sought to inspire the American people with forward-looking platitudes while harkening back to a military moment that restored American pride. Rather than dwelling on the present-day defeat at a 23 April speech at Tulane University’s New Orleans, Louisiana, campus, Ford recalled a proud moment in U.S. history. Before referring to Vietnam as a “war that is finished as far as America is concerned,” he remembered the American victory in the 1815 Battle of New Orleans as a “national restorative to our pride” after having suffered “humiliation and a measure of defeat” when the British burned Washington, DC. Ironically, in the context of connecting the Mayaguez incident and Vietnam, Ford referred to the Battle of New Orleans as part of the War of 1812, although “the victory at New Orleans actually took place two weeks after the signing of the armistice in Europe. Thousands died although a peace had been negotiated. The combatants had not gotten the word,” he noted. For reasons of policy, late April 1975 was equivalent to January 1815 for Ford: “In New Orleans, a great battle was fought after a war was over. In New Orleans tonight, we can begin a great national reconciliation.”23 While recalling the past, Ford wanted the American public looking to the future.

Coincidentally, his battle for national reconciliation came just two weeks later with the seizure of the Mayaguez—a week after he closed the Vietnam era via presidential proclamation. Ford referred to the Cambodian seizure of the ship as a “clear act of piracy,” not an act of war.24 This characterization made a clean conceptual break with Vietnam and made any subsequent military action more acceptable to the public. He also considered it piracy for legal reasons. The War Powers Resolution rescinded presidential authority to send combat forces into Indochina without congressional authorization. Although he complied with some of the War Powers Resolution’s terms by notifying Congress before ordering the Marine assault and rescue mission, Ford deftly argued his authority to use force to protect the private interests of American citizens from pirates at any time.25 U.S. military heroics that safely returned the crew and ship fulfilled Ford’s national restorative wish. His Gallup approval ratings shot up 11 points, previously recalcitrant members of Congress heaped praise, and the once-morose public cheered.26 Ford’s characterization of events at the national executive level helped to establish the existing disjointed narrative about Vietnam and the Mayaguez.

As the White House and Congress debated how to end the war and whether to continue aid for Indochinese governments, the DOD adjusted military award policies to reflect the changing context. After the end of the Vietnam Ceasefire Campaign in January 1973, DOD stopped awarding the VSM, which had been awarded to eligible servicemembers with service in Vietnam, Cambodia, and Laos since 1965 (and retroactively to 1958).27

For DOD, the Mayaguez operation occurred at the wrong time, in the wrong location, against the wrong enemy, and without connection to the military effort in Vietnam to be considered part of the Vietnam War. Neatly, the eligibility termination date for the VSM aligns with “the signing of the Paris Peace Accords which led to the cessation of military combat operations in Vietnam and ended direct U.S. military involvement in the Vietnam conflict,” and after which in Vietnam there were “no combat operations or combat casualties.”28 Because Cambodian Communists captured the Mayaguez, not Vietnamese, and because the rescue mission was interpreted as not being directed toward “support operations in Vietnam,” DOD’s position was that participating servicemembers were appropriately awarded the Armed Forces Expeditionary Medal (AFEM) for operations disconnected from a larger war instead of the VSM.29

Resistance to connecting the Mayaguez with Vietnam also came from some Vietnam veterans. This phenomenon centers on whether a servicemember earned the distinctive title Vietnam veteran by serving in Vietnam (generally recognized through receipt of the VSM) or is a Vietnam-era veteran who happened to be in the Armed Services during the Vietnam War but never served in-country. The Vietnam War dominates popular memory of the U.S. military during the 1960s and early 1970s. Approximately 2.5 million American troops served somewhere in Southeast Asia during the war, but during the same time frame more than 2.5 million servicemembers never went to Southeast Asia.30 Many Vietnam veterans, especially those claiming combat veteran status, vociferously defend the distinctive title.31

VSM-wearing veterans may recognize the Mayaguez’s relation to the war as a battle experience in Indochina but discount it as part of the Vietnam War for different reasons than DOD. Length of tour matters for many Vietnam veterans when considering whether to confer veteran status on others: “The criteria for the Vietnam Service Medal and Vietnam Campaign Ribbon are very specific, and both require 30 or more days in-country unless captured, wounded or killed.”32 Koh Tang may have been a 14-hour hell for the Marines on the beach, but it was a one-off mission, not a months- or yearslong deployment experience. Timothy Trebil, who was 19 years old when he earned the Purple Heart during the Mayageuz rescue, recalls being ostracized by older Vietnam veterans in the 1990s for wearing a Purple Heart cap; they wondered how someone who was noticeably younger but too old to be an Operation Desert Storm veteran could have possibly earned a Purple Heart during their military career.33 These political, legal, bureaucratic, and social reasons for separating the incident from Vietnam rely on the supposition that a war is over when an actor desires it to be over and neglect war’s dialectic nature.

Widening the Frame: The Mayaguez Incident as “Last Battle”

The Mayaguez incident should be properly understood as the United States’ last battle in the Vietnam War for broad geostrategic and specific local historic reasons. Geostrategically, the war the United States militarily entered in the 1950s, escalated in 1965, left in 1973, and reentered in 1975 was a wider Indochinese war at the confluence of European decolonization, the ideological East-versus-West Cold War, and intraregional conflicts for control of Indochina. The war did not end with the last American helicopter lifting off from a Saigon rooftop because it involved more than just U.S. support for South Vietnam. The incident is also directly historically connected to operations in Vietnam for specific local reasons: the Mayaguez carried sensitive equipment it had recently loaded in Saigon and some of the same U.S. forces participated in both the evacuation of Saigon and the ship rescue.

Vietnam is an inexact prefix and national mnemonic device for a war that touched all of Indochina. The reality that a clear majority of, though not all, U.S. troops who participated in this war did so from within Vietnamese borders creates the domestic misperception that the war was all about the survival of South Vietnam in the face of Vietnamese Communist aggression. The war predated U.S. involvement, and comprehending it requires an understanding of Indochina’s experience with European colonization in the first half of the twentieth century, especially at the close of the Second World War.

This wider twentieth-century Indochina war bore resemblance to historical struggles for territorial control between ethnic Cambodian, Laotian, Vietnamese, and Thai peoples, but French removal after the 1954 Geneva Conference unleashed local power struggles anew within a postwar decolonization context.34 Violent unrest in the wake of the Second World War was not unique to Indochina. Wars of independence from European colonial powers erupted across Asia, Africa, and Latin America. Independence often occurred in tandem with bloody war and did not mean new governments accepted the borders and sovereignty established in Geneva.35

Events in Cambodia after 1954 are an exemplary case of the wider war that extends beyond U.S. involvement. The new Kingdom of Cambodia and its inconstant monarch Prince Norodom Sihanouk attempted to remain neutral in the part of the war represented by the North-South Vietnamese conflict. This reflected Cambodia’s geographic position between the historically stronger powers of Vietnam and Thailand. Yet, during a period of supposed peace from 1954 until overt U.S. military intervention in Cambodia in 1970, Sihanouk’s regime suffered a border invasion and occupation from Thai troops in the Dângrêk Mountains, large-scale occupation by North Vietnamese regular forces, armed incursions from South Vietnamese Communists, and growing threats from homegrown Cambodian Khmer Communists.36 The 1970 coup that overthrew Sihanouk for Prime Minister Lon Nol, the later controversial U.S. “incursion,” and Lon Nol’s massacre of ethnic Vietnamese undoubtedly represented war in Cambodia, but describing the prior period as one of peace obscures the lived experience in many parts of the country.37 The internal struggles for power and control between Communist parties in North Vietnam and Cambodia also conceptually link the Mayaguez incident and the Vietnam War.

The Cold War served as the overarching context for the Vietnam War in national understanding, and Communism was an important component of the wider war, but not in a rudimentary “Communism versus the Free World” sense. The component of Indochinese Communism that best connects the Mayaguez to Vietnam is the conflict between competing Communist factions. While for a time nominally aligned as Communists against U.S. imperialism, the Vietnamese Workers Party (VWP, or North Vietnamese Communist politburo) and the Communist Party of Kampuchea (CPK, an umbrella organization that included the Khmer Rouge) competed for territorial control and ideological purity. National and local interests trumped their Communist connection. The CPK detested the VWP’s blatant chauvinist attitude toward Khmer Communists. The VWP publicly supported Prince Sihanouk’s claim to power after the coup that overthrew him against both the U.S.-backed Lon Nol government and Pol Pot’s CPK. As an example of this animosity, after assuming control of the CPK in 1971, Pol Pot began the systematic killing of Vietnamese trained Khmer Communists to purge his movement from any connection to Hanoi.38

When U.S. forces responded to crises across the region in 1975, they participated in the same convulsive war, not separate conflicts. The Khmer Rouge defended Koh Tang heavily because they feared an invasion from their North Vietnamese “hereditary enemy.”39 Before and after the Mayaguez incident, the Poulo Wai Islands and Koh Tang were contested borderlands for the Khmer Rouge and the Vietnamese government in Hanoi to the point of armed conflict.40

Moving down from the geostrategic, there are specific U.S. military factors that link the Mayaguez rescue and operations in Vietnam as two parts of a wider conflict. U.S. forces stationed in Southeast Asia for more than a decade operated and reacted to events across Indochina both during the bureaucratically restricted Vietnam War time frame and after. For U.S. Air Force units in Southeast Asia with a mission to keep the non-Communist dominoes from falling, the January 1973 Paris Peace Accord was more of an administrative stroke of the pen than a change from war to peace, because it only concerned Vietnam. This meant more sorties were available in Laos and Cambodia until their respective peace agreements could be reached. Thailand-based units continued flying combat missions over Laos until 17 April and Cambodia until 16 August 1973. In the last 160 days of bombing in Cambodia alone, the United States exceeded by 50 percent the total tonnage of conventional explosives used against Japan in the Second World War. But if peace supposedly reigned across Indochina, it resulted in the redeployment of only a few thousand Thailand-based servicemembers and about a hundred aircraft to the United States. Approximately 40,000 soldiers and 400 aircraft remained, including all the Boeing B-52 Stratofortress bombers.41

From August 1973 until early 1975, these units prepared to resume fighting. The war continued and looked dire for the U.S.-backed governments in Indochina, but the order for combat did not come. Instead, with Khmer Rouge forces closing on Phnom Penh in early April 1975, the Thailand-based aircraft launched Operation Eagle Pull to rescue embassy personnel and other U.S. citizens. Only two weeks later at the end of April, many of the same aircraft flew from Thailand to South Vietnam in a larger rescue effort, Operation Frequent Wind, as North Vietnamese forces closed on Saigon. When they landed back at Thai bases, such as U-Tapao, they shared runway space with fleeing South Vietnamese aircraft and personnel.42 Things appeared final in Cambodia and Laos, but these units still prepared for combat and reacted to events in the wider Second Indochina War. When they received the call for the Mayaguez, some of the same personnel, in the same units, from the same bases who earned the VSM for flying over Cambodia, Laos, or Vietnam flew back to Cambodia.43

Like Air Force units in Thailand, U.S. Marines stationed in Okinawa had long served as a reserve quick-response force for any crisis in Southeast Asia, the Korean Peninsula, or elsewhere in the Pacific. The 2d Battalion, 9th Marine Regiment—young Lance Corporal Timothy Trebil’s outfit—assumed this duty in early 1975. Members of the battalion recall being flown out to train on naval vessels in preparation for the worst in Phnom Penh and Saigon. Because the evacuation situations were so chaotic, decisions about which parts of the battalion would participate in the operations were made in apparent haste and in a way that seemed arbitrary to many of the young Marines. Handfuls of Marines from different companies and platoons flew in to participate while other elements flew back to Okinawa to remain on standby. The Marines of 2d Battalion, 9th Marine Regiment, who went to help with the Saigon evacuation returned to Okinawa around 7 May, only to be ordered back to combat a week later for the Mayaguez rescue. These Marines, many of them youthful first-term enlisted Marines like Trebil, knew North Vietnamese victory over the South was momentous, but the clear distinction between a war and an incident had yet to be drawn.44 Shifting focus from the Marines to the Mayaguez reveals a connection to Saigon, as well.

Official Department of Defense photo, courtesy of Historical Resources Branch, Marine Corps History Division

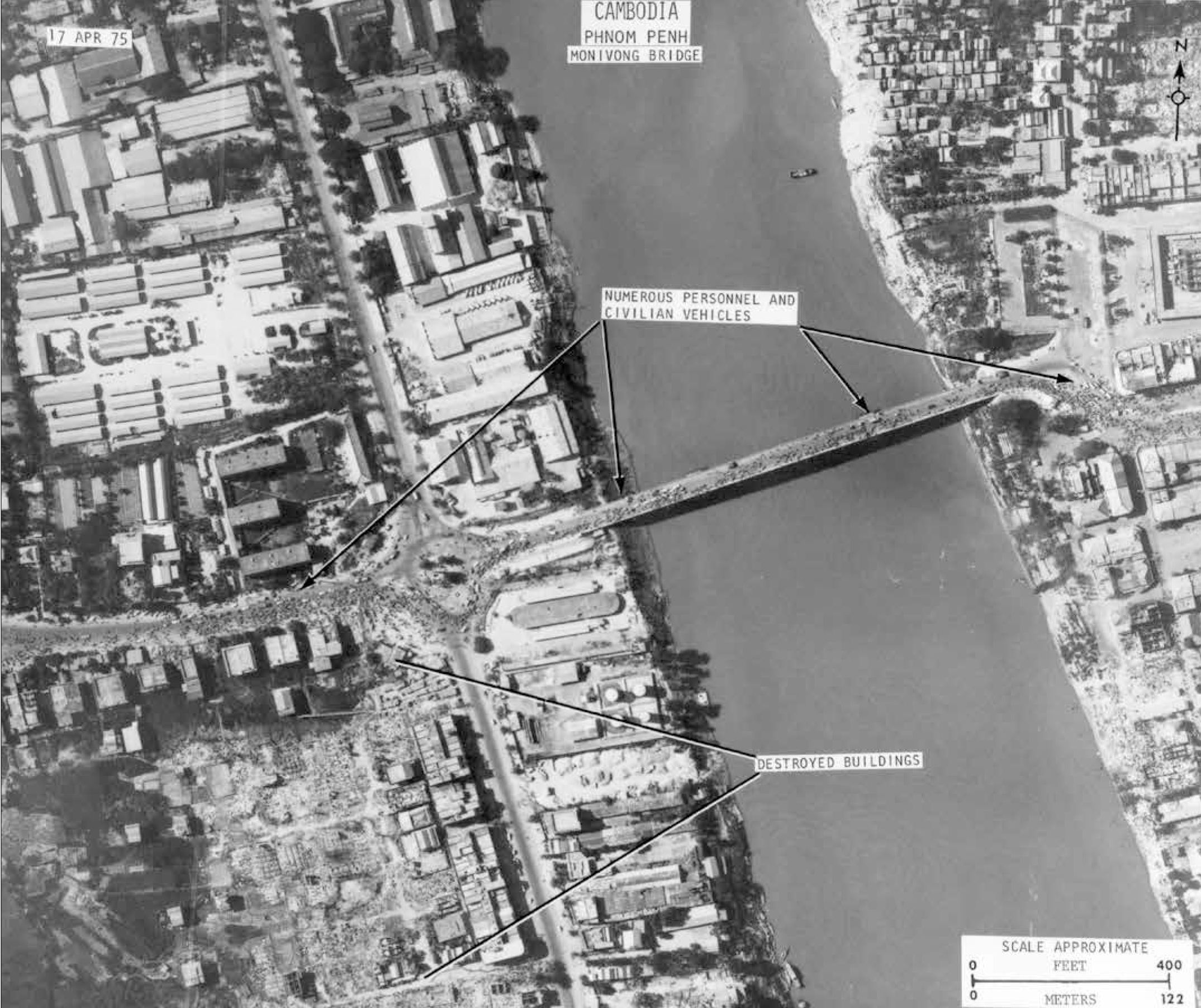

Aerial view of the Monivong Bridge showing numerous personnel and civilian vehicles, Phnom Penh, Cambodia, 17 April 1975.

DOD rejects claims to award the VSM to Mayaguez veterans partially because the operation did not “support operations in Vietnam,” yet the ship’s purpose at the time of capture was to retrograde equipment from the evacuated Saigon.45 Several Mayaguez crew members sued both the United States and the ship’s owner, Sea-Land Corporation, for multi million-dollar damages in the years following their return from captivity. Multiple suits against Sea-Land were filed in California admiralty courts and later consolidated under the case Rappenecker v. Sea-Land Service, Inc. The aggrieved former crew members contended that, through the actions of the ship’s captain, Sea-Land “recklessly ventured into Cambodian waters” and “clearly invited the seizure and detention of the Mayaguez.”46 Moreover, discovery through the trial process revealed interesting facts about the Mayaguez’s sea route and assumptions about the content of its containers that are scarcely mentioned in accounts of the ship’s purportedly innocent voyage through the Gulf of Thailand. These details suggest the Mayaguez served as the transport ship in the operation to remove top-secret intelligence-gathering equipment from the U.S. embassy in Saigon prior to evacuation.

The first revelation deals with the origin of the Mayaguez’s voyage. Hong Kong is often cited as the ship’s port of departure prior to capture, but less widely cited by historians is that the ship docked in Saigon to load equipment from the U.S. embassy before it traveled to Hong Kong. Only items of significant interest to the United States would be worth loading into containers in the face of an invading army. In fact, trial deposition revealed the “administrative” equipment was loaded under special circumstance with an embassy escort.47 Also suggestive that some of the cargo loaded at Saigon was sensitive is the unusual fact that the ship’s captain admitted under deposition that some of the cargo was secret and that he destroyed at least one secret code upon being captured.48 These details indicate that the Mayaguez was neither a typical container ship nor making a typical voyage.

Second, the ship’s capture is often recounted as the aggressive seizure of an innocent vessel passing through international waters.49 Trial discovery revealed the Mayaguez was less than 3 kilometers from the coast of Poulo Wai Island at the time of its capture—well within disputed territorial waters and nowhere near an international sea lane.50 As claimed by the trial plaintiffs, this was at least “negligence, dereliction, and reckless misconduct,” given the regional unrest at the time.51 One would assume if a ship did not want to be seized or was not involved in sea-based espionage of coastal territories that it would hedge away from hostile territory.

Third, after it was recovered, the ship made an unplanned stop to unload a handful of its 274 containers in Singapore before continuing to its planned destination of Sattahip, Thailand. Given the prior incident with the Pueblo spy ship, many in the global press speculated the Mayaguez had been conducting a similar operation. Sea-Land and the U.S. government invited the press to search the ship in Singapore, but no containers were opened. Later, on arrival in Thailand, the press investigated only 6 of the 274 containers.52 Even when pressured under litigation, the U.S. government failed to disclose the complete contents of the containers of the Mayaguez and many of the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) files related to the rescue operation remain classified.

Removal of sensitive U.S. government equipment and military cargo before it fell into the hands of the North Vietnamese was in essence a retrograde operation—the movement of “equipment and materiel from a forward location . . . to another directed area of operations.”53 Contrary to the narrowly interpreted DOD policy, removal of this equipment from Vietnam supported U.S. interests in Vietnam, which by late April 1975 consisted of securing people and sensitive property. The ship’s contents were at least among the most critical items to be retrograded in the final hours of the United States’ Saigon embassy. U.S. decision-makers may have believed their involvement in the Second Indochina War was over as the ship sailed away from Vietnam, but the Khmer Rouge unexpectedly dragged the United States back into the war by seizing the ship.

Placing the Mayaguez incident within the American idea of the Vietnam War (the Second Indochina War) acknowledges that events within the region in late April and early May were seamless, fluid, and part of a wider war. Adopting this broader framework also acknowledges that war is a dialectical enterprise between multiple forces. It is complex, confusing, and not always logical. In the narrow view, since the ship’s capture was not part of a larger effort represented by a chain of military orders, it can be discarded as a oneoff, a chance incident. This view misses the confluence of larger processes, including a long history of armed conflict in and around Cambodia and Laos, especially on the border regions, which characterized the long war in Indochina. This view also neglects the hard facts that the same U.S. forces operated between the two nations concurrently before and after the Paris Peace Accords and that the Mayaguez ship was retrograding equipment from Saigon at the time of its capture. Forces in combat with different sets of enemy forces, all involved in the same struggle, are still participating in the same war. By taking off the blinders emplaced by bureaucratic stricture—an overemphasis on dates and borders—one can view the Mayaguez rescue operation as the United States’ last battle in its decades-long involvement in a long Indochina war— a war we have called in shorthand the Vietnam War.

The Mayaguez Incident and Historical Memory

This understanding is not revisionist history in the sense no one understood it to be true at the time. In early 1975, but before the Mayaguez incident, the public recognized a connection between events in Cambodia and Vietnam. This perspective continued for some immediately after the Mayaguez’s capture and has since been supported publicly in various ways, some of them with national notoriety and U.S. government acknowledgement, and some of them even with sanction from the DOD.

While Ford and congressional leaders did not frame the Mayaguez incident publicly as part of the Vietnam War for policy reasons, they strongly promoted a connected understanding between events in Cambodia and Vietnam in the months before the incident. Congress provided millions of dollars in aid to South Vietnam, Cambodia, and Laos in the hopes of staving off Communist revolutions.54 As Congress debated further aid in early March, Senator Robert C. Byrd worried that “additional military support for either Cambodia or South Vietnam probably would fall into the hands of those we are now opposing.” Ford’s press secretary, Ron Nessen, advised the U.S. “should withdraw” from “Indochina”—not Vietnam—while proposing in a draft of Ford’s joint address to Congress that in this war, “South Vietnam and Cambodia have fought bravely and long.”55 When Ford delivered the address on 10 April, he remarked how “under five Presidents and 12 Congresses, the United States was engaged in Indochina. Millions of Americans served, thousands died, and many more were wounded, imprisoned, or lost.”56 The events in Indochina were personally one war for Ford in this moment, although he had little desire to continue the conflict.

Admiral Noel Gayler, commander of U.S. Pacific Command from 1972 to 1976, recalled in his memoirs that one of the problems in fighting the Vietnam War was a misinterpretation of “what was really a quarrel basically over which Vietnamese sect was going to control what had been French Indochina.”57 He also recalled that “after December ‘72 [and the Paris Peace Accord] . . . we still had a considerable logistic responsibility to the South Vietnamese and the Cambodians—and I made many visits both to Saigon and Phnom Penh, up into the hills and everywhere else—to see what was going on. Still, we had defacto conceded the war by then.”58 Combat being over on paper did not mean the war effort was over for Pacific Command.

The capriciousness that sent some Marines from 2d Battalion, 9th Marine Regiment, to Cambodia to support Operation Eagle Pull, to Saigon to support Operation Frequent Wind, and finally to the Gulf of Thailand to recover the Mayaguez made it difficult for some Marines and other servicemembers involved to distinguish how these happenings could be considered separate, unrelated events. After years of seeing video footage of American helicopters lifting evacuees off the rooftops in Saigon, the U.S. withdrawal is seared into the national memory as the final event of the war. For servicemembers in Southeast Asia at the time, the situation was much more fluid.59 As North Vietnam consolidated its victory in the south, Khmer Rouge on the borders and contested islands prepared for Vietnamese invasion, and thousands of refugee boats fled, U.S. military personnel in the region continued to prepare for the unexpected.

Among other U.S. naval vessels with similar stories, the experience of the sailors on the USS Schofield (FFG 3), a guided missile frigate, is instructive. On the same Western Pacific deployment from its California base in early 1975, Schofield floated up the Saigon River into Vietnam during South Vietnam’s last few days, then assisted evacuees off the coast and escorted fleeing South Vietnamese vessels to Subic Bay, Philippines, before steaming back to the Gulf of Thailand to support the Mayaguez recovery operation.60

Thailand-based servicemembers provide more evidence of this seamless connection. After landing and later recovering stranded Marines off Koh Tang’s beach, members of the Air Force’s 40th Aerospace Rescue and Recovery Squadron and 21st Special Operations Squadron returned to Nakhon Phanom Royal Thai Air Force Base. On 19 May, four days after the operation ended (which also happened to be Vietnamese Communist revolutionary Ho Chi Minh’s birthday, though he had been dead for almost six years) some of the squadrons’ enlisted servicemembers commemorated their rescue with a party. Makeshift signs included both the celebratory “U.S.S. [sic] Mayaguez Raiders” and the antagonistic “F——k Ho Chi Minh.”61 For these airmen in Thailand, their operations against Communist forces in Southeast Asia—whether in Cambodia or Vietnam—were linked.

The connected context soon found itself in print. The Marine Corps Association’s Leatherneck magazine dedicated its September 1975 issue to the “end of an era” with an image of the VSM adorning the cover. Inside, the edition featured articles about the Marine Corps’ role in Operations Eagle Pull, Frequent Wind, and the Mayaguez rescue. At the time, none of these operations qualified Marines for the medal on the magazine’s cover.62 More than members of the military held the Mayaguez incident as part of the Vietnam War in 1975.

The U.S. Senate passed Senate Resolution 171, “A Resolution to Pay Tribute to American Servicemen Who Fought in Southeast Asia and to Their Families,” on 22 May 1975, which included the suggestive following statements: “Whereas, the participation of American troops in hostilities in Southeast Asia have been brought to an end,” and “that the nation is eternally grateful to all those American servicemen who participated in the Southeast Asian conflict.”63 Veterans’ family members also made this wider connection. The most publicly notable recognition that the Mayaguez rescue operation concluded U.S. combat operations in the Vietnam War came in 1982 with the opening of the Vietnam War Memorial (The Wall). The 41 servicemembers who lost their lives in the operation are the last names etched into The Wall as casualties of the Vietnam War. This was neither a typo nor a casual oversight and includes some level of sanction from the DOD. The Wall, from conception to completion, was the effort of a group of veterans who fought in Vietnam and sought appropriate recognition for their generation’s sacrifice. Former Army infantryman Jan C. Scruggs conceived the initial vision, and together with former Air Force intelligence officer Robert W. Doubek and the rest of the nonprofit Vietnam Veterans Memorial Fund (VVMF) staff, carried the project to its place on the National Mall in Washington, DC.64 The controversy surrounding The Wall’s design is well known, but less so is the outpouring of petitions the VVMF received on behalf of grieving parents, spouses, and siblings trying to ensure their family member’s name would be inscribed. Many Americans lost their lives on land in Indochina and offshore during U.S. involvement in the region. Many were deployed and still remain missing or unaccounted for. Most casualties came from hostile fire, but some came from accidents or natural causes—even homicide and suicide—and not all the fallen were servicemembers. In addition to the hundreds of letters received from military family members, the VVMF received impassioned pleas from the families of fallen State Department and CIA personnel, and even the family of a murdered Red Cross volunteer.65

The VVMF needed a supportable set of criteria by which to judge these requests. Given their vision to honor fallen servicemembers, they respectfully informed petitioning nonmilitary family members that their loved one’s sacrifices were included in The Wall’s purpose to memorialize but would not be inscribed. Yet, this still left hundreds of requests from military families, such as a mother whose sailor son died on board a ship in the South China Sea while fighting raged in Vietnam.66 To this mother, her son died in the Vietnam War, but not in the eyes of the VVMF. The group’s board of directors decided to rely mostly on a listing of casualties in Southeast Asia compiled by the DOD, cross-checked against lists compiled by the individual Services, while also considering the executive order that classified Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia as combat zones. The casualty names from the Mayaguez operation appeared on Air Force and Marine Corps lists, but not on DOD’s. VVMF considered the Mayaguez names along with other apparent outliers such as Air Force lieutenant colonel Clarence F. Blanton, who was killed atop a Laotian tactical air navigation radar site by North Vietnamese soldiers in 1968, and whose presence on the Air Force casualty list in 1982 represented the first time the U.S. government publicly acknowledged his death.67 When 150,000 Americans dedicated The Wall on Veterans Day 1982, they saw the names of the 41 airmen, sailors, and Marines who died for the Mayaguez engraved as the last casualties of the Vietnam War.

The story told by the iconic U.S. Marine Corps War Memorial, or Iwo Jima Memorial, also considers the Mayaguez to be a part of the Vietnam War. The memorial managed by the Corps and the National Park Service lists the names and dates of the well-known wars and battles, but also lesser known engagements, in which U.S. Marines have fought. The listing for Vietnam gives the dates 1962–75. When a group of Mayaguez veterans queried the memorial’s curator as to why the Koh Tang operation did not have its own inscription, he replied that the event is included in the Vietnam inscription.68

Poignantly, and succinctly, Senator John S. McCain remembered what the Mayaguez incident represented when he traveled to the reestablished U.S. embassy in Phnom Penh to dedicate a memorial for the mission’s fallen on Veterans Day 1996. McCain bluntly stated, “The Mayaguez fight, we know, was the last combat action of America’s longest war. Of course, war continued in Indochina after May 1975. . . . But for Americans, the Mayaguez should have been an end point, a final chapter.” For many who served in it, the Mayaguez rescue operation did represent this conclusion.69

Conclusion: Ribbons and War in Context

Mayaguez veterans formed a group in the 1990s, now known as the Koh Tang/Mayaguez Veterans Organization, to connect to their shared past and find resolution. The group’s website is a place where Mayaguez veterans “as well as their friends, and families can find comfort and support to this oft-forgotten chapter in American history.”70 For the past 20 years, the group has advocated for recognition from the DOD to correct the “lingering slight that those who participated in the Mayaguez Operation have been denied the right to wear the VSM for over 40 years.”71 Yet, more important to the group has been its quest to find closure for families and friends of the fallen through repatriation of their remains. Most, but not all, have been accounted for, and the group has yet to rest.

The Koh Tang/Mayaguez Veterans Organization is not the only group from the waning days of the conflict to push for DOD recognition as Vietnam veterans. Veterans who assisted in the evacuation of Saigon lobbied their members of Congress for recognition with the VSM in the early 2000s. The VSM’s narrowly defined cutoff date remained aligned with the signing of the Paris Peace Accords on 28 January 1973. DOD resisted, but Congress resolved in the National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA) for fiscal year 2002 that the secretary of defense “should consider” awarding the VSM to those who evacuated Saigon.72 In the following year’s defense authorization act, “should consider” became “shall award.”73 Today, Operation Frequent Wind veterans in the U.S. Navy, Marine Corps, and Air Force are eligible to exchange their previously awarded Armed Forces Expeditionary Medals (AFEM) for the VSM. A wider view of the war won out.

Mayaguez veterans have made a similar case. House Resolution 1788, Recognizing Mayaguez Veterans Act, introduced in March 2017, resolved to allow Mayaguez veterans to exchange their AFEM awards for the VSM.74 It was considered as part of the fiscal year 2018 NDAA, though not adopted as part of the bill’s final passage. DOD resisted this wider view even though it included a prominent display of the Mayaguez operation in its own Vietnam War Commemoration corridor in the Pentagon, dedicated just a few months prior to the bill’s introduction.75

Compared to the wrangling over the VSM’s restrictiveness, consider the ubiquitous Global War on Terrorism Expeditionary and Service Medals (GWOTEM and GWOTSM, respectively). Both medals were established by executive order on 12 March 2003, prior to Operation Iraqi Freedom and in the wake of the 11 September 2001 (9/11) attacks. The GWOTEM, the more restrictive medal, requires service in either combat or a designated hostile area in any of 54 specific geographic areas from the South China Sea, Middle East, Africa, Europe, and certain waterways in between. Even broader, any servicemember on active duty, anywhere in the world for more than 30 days since 9/11 receives the GWOTSM until a cutoff date to be determined.76 Although there are political, legal, and bureaucratic reasons to do so, wars in reality are rarely circumscribed by political and geographic borders with tidy start and end dates. Timothy Trebil and all Mayaguez veterans earned the VSM in addition to the NDSM because the Vietnam War ended for the United States when the fighting stopped on Koh Tang in 1975.

•1775•

Endnotes

- Timothy Trebil, 2d Battalion, 9th Regiment veteran, interview with author, 10 November 2017, Arlington, VA, hereafter Trebil interview.

- Exec. Order No. 10448, 3 C.F.R., 1949–1953 Comp., 935.

- Trebil interview.

- Legal and social questions regarding status as a Vietnam veteran or Vietnam-era veteran have abounded since at least 1974. For example, see Vietnam Era Veterans’ Readjustment Assistance Act, H.R. 12649, 93d Cong. (1974).

- Proclamation No. 4373, Fed. Reg. 20257 (7 May 1975).

- Donald Kirk, Wider War: The Struggle for Cambodia, Thailand, and Laos (New York: Praeger, 1971), 3–15.

- On the importance of historical memory, see David Thelen, “Memory and American History,” Journal of American History 75, no. 4 (March 1989): 1117–29.

- David L. Anderson, The Columbia Guide to the Vietnam War (New York: Columbia University Press, 2002), 191.

- For brevity, the article refers to the totality of U.S. military actions around Koh Tang and the Mayaguez from 12–15 May 1975 as the “Mayaguez rescue operation,” “the Mayaguez,” the “Mayaguez incident,” or “the incident” unless otherwise specified.

- The decisions surrounding the fate of LCpl Joseph N. Hargrove, PFC Gary L. Hall, and Pvt Danny G. Marshall require greater attention, but that is not the focus of this article. See John F. Guilmartin Jr., A Very Short War: The Mayaguez and the Battle of Koh Tang (College Station: Texas A&M University Press, 1995).

- George C. Herring, America’s Longest War: The United States and Vietnam, 1950–1975, 4th ed. (New York: McGraw Hill, 2001), 340–42; Lewis Sorley, A Better War: The Unexamined Victories and Final Tragedy of America’s Last Years in Vietnam (New York: Harcourt Brace, 1999); Michael Lind, Vietnam: The Necessary War—A Reinterpretation of America’s Most Disastrous Military Conflict (New York: Free Press, 1999); Robert McMahon, Major Problems in the History of the Vietnam War: Documents and Essays (New York: Houghton Mifflin, 2008), 437–540; Anderson, The Columbia Guide to the Vietnam War, 191; Anderson, ed., The Columbia History of the Vietnam War; Kenton Clymer, “Cambodia and Laos in the Vietnam War,” in The Columbia History of the Vietnam War, ed. David L. Anderson, 357–81; Lien-Hang T. Nguyen, Hanoi’s War: An International History of the War for Peace in Vietnam (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2012), 300–4; and Mark Atwood Lawrence, The Vietnam War: An International History in Documents (New York: Oxford University Press, 2014), 173–74.

- Robert D. Schulzinger, Henry Kissinger: Doctor of Diplomacy (New York: Columbia University Press, 1989), 203–5; Jussi Hanhimäki, The Flawed Architect: Henry Kissinger and American Foreign Policy (New York: Oxford University Press, 2004), 398; John Robert Greene, The Presidency of Gerald R. Ford (Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 1994), 143–51; and Douglas Brinkley, Gerald R. Ford (New York: Times Books, 2007), 100–6.

- Roy Rowan, The Four Days of Mayaguez (New York: Norton, 1975); Christopher Jon Lamb, Belief Systems and Decision Making in the Mayaguez Crisis (Gainesville: University of Florida Press, 1989), 99; Lucien S. Vandenbroucke, Perilous Options: Special Operations as an Instrument of U.S. Foreign Policy (New York: Oxford University Press, 1993), 72–112; and James E. Wise Jr. and Scott Baron, The 14-Hour War: Valor on Koh Tang and the Recapture of the SS Mayaguez (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 2011), ix–x. North Korea captured the USS Pueblo in 1968 and the ship remains in its possession. The Mayaguez’s seizure made an immediately recognizable connection. See Mitchell B. Lerner, The Pueblo Incident: A Spy Ship and the Failure of American Foreign Policy (Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 2002).

- Robert J. Mahoney, The Mayaguez Incident: Testing America’s Resolve in the Post-Vietnam Era (Lubbock: Texas Tech University Press, 2011), xiii– xiv.

- “Recovery of the S.S. Mayaguez,” in Maj George R. Dunham and Col David A. Quinlan, U.S. Marines in Vietnam: The Bitter End, 1973–1975 (Washington, DC: History and Museums Division, Headquarters Marine Corps, 1990), 238–65; Guilmartin, A Very Short War, 28; Ralph Wetterhahn, The Last Battle: The Mayaguez Incident and the End of the Vietnam War (New York: Carroll and Graf Publishers, 2001); Ric Hunter, “SS Mayaguez: The Last Battle of Vietnam,” Flight Journal 5, no. 2 (April 2000): 46–54; and Ric Hunter, “The Last Firefight: the Desperate and Confused Battle Triggered by the Mayaguez Incident was a Disturbing Finale to America’s War in Southeast Asia,” Vietnam 23, no. 2 (August 2010): 38–45; and Christopher J. Lamb, The Mayaguez Crisis, Mission Command, and Civil-Military Relations (Washington, DC: Office of the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, 2018), 1.

- Lydia Saad, “Gallup Vault: Hawks vs. Doves on Vietnam,” Gallup News, 24 May 2016.

- Jeffrey Kimball, Nixon’s Vietnam War (Lawrence: University of Kansas Press, 1998); and Larry Berman, No Peace, No Honor: Nixon, Kissinger, and Betrayal in Vietnam (New York: Free Press, 2001).

- War Powers Resolution, 50 U.S.C. § 1541 (1973).

- “Gerald R. Ford, 38th President of the United States: 1974–1977. Remarks on Taking the Oath of Office, 9 August 1974,” American Presidency Project (website), accessed 15 December 2017.

- Ford’s press secretary, Ron Nessen, laid out the political calculus on the eve of Ford’s address to a Joint Session of Congress, 10 April 1975. See “Memorandum for Donald Rumsfeld, from Ron Nessen,” 8 April 1975, Vietnam General File, Richard Cheney digital collection, Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library (GRFPL), Grand Rapids, MI, 31.

- “Lyndon B. Johnson, 36th President of the United States: 1963–1969. Executive Order 11216—Designation of Vietnam and Waters Adjacent Thereto as a Combat Zone for the Purposes of Section 112 of the Internal Revenue Code of 1954, 24 April 1965,” American Presidency Project (website).

- “Memo on Subject of Termination of Wartime Veterans Benefits,” 27 January 1975, box 39, Veterans (1) folder, Jack Cannon digital collection, GRFPL, 28.

- “Gerald R. Ford: Address at a Tulane University Convocation, 23 April 1975,” American Presidency Project (website), accessed 16 December 2017.

- Memorandum, “NSC Meeting of May 12, 1975,” box 1, NSC Meeting, 5/12/1975 folder, National Security Advisor’s NSC Meetings file, 1974– 77, digital collections, GRFPL.

- Stephen Isaacs, “Authority Is Cited for Use of Force,” Washington Post, 14 May 1975.

- See Jeffrey Jones, “Gerald Ford Retrospective,” Gallup News, 29 December 2006; several articles in Time, U.S. edition, 26 May 1975; and several articles in Newsweek, U.S. edition, 26 May 1975.

- For example, see Vietnam War campaign dates in Secretary of the Navy Instruction (SECNAVINST) 1650.1H, Navy and Marine Corps Award Manual (Washington, DC: Department of the Navy, 22 August 2006), 8-20.

- Combat casualty is a bureaucratic term that does not include, in this case, those American servicemembers who died as a direct result of enemy fire within the VSM’s earlier geographic eligibility boundaries after January 1973. For example, Cpl Charles McMahon Jr. and LCpl Darwin L. Judge, who died from Viet Cong rocket attack while defending the American embassy in Saigon on 30 April 1975, were not eligible for the VSM.

- DOD Director of Officer and Enlisted Personnel Management (Military Personnel Policy) letter to Donald Raatz, 7 April 2017, shared with author by Donald Raatz, hereafter DOD Personnel Policy letter to Raatz. For DOD, the Mayaguez bears more connection to operations such as Urgent Fury in Grenada in 1983 or El Dorado Canyon in Libya in 1986 than to the Vietnam War.

- “U.S. Military Casualties—Vietnam Conflict Casualty Summary,” Defense Casualty Analysis System, accessed 17 December 2017.

- See Spc Johnny Velazquez, PhD, “Should Vietnam Era Vets be Addressed as ‘Vietnam Vets’?,” Rally Point message boards, 27 February 2015; and T. L. Johnson Jr., letter to the editor: “Johnson: There Is a Difference between ‘Vietnam Vet’ and ‘Vietnam Era Vet’,” Amarillo (TX) Globe-News, 27 April 2015.

- Johnson, “Johnson: There Is a Difference between ‘Vietnam Vet’ and ‘Vietnam Era Vet’.”

- Trebil interview.

- Kirk, Wider War, 3–15.

- Odd Arne Westad, The Global Cold War: Third World Interventions and the Making of Our Times (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2007), 87.

- Kirk, Wider War, 41–67.

- Nguyen, Hanoi’s War, 173–75.

- Nguyen, Hanoi’s War, 179–80.

- Pak Sok, questioning by Kong Sam On, transcript of trial proceeding, Extraordinary Chambers in the Courts of Cambodia, Trial Chamber—Trial Day 351, Case No. 002/19-09-2007-ECCC/TC, 5 January 2016, 63–75, accessed 22 November 2020.

- Pak Sok, questioning by Victor Koppe, transcript of trial proceeding, Extraordinary Chambers in the Courts of Cambodia, Trial Chamber—Trial Day 351, Case No. 002/19-09-2007-ECCC/TC, 5 January 2016, 37–41, accessed 22 November 2020.

- Jeffrey D. Glasser, The Secret Vietnam War: The United States Air Force in Thailand, 1961–1975 (Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 1995), 196–98.

- Glasser, The Secret Vietnam War, 204–8.

- For example, Hunter, “The Last Firefight,” 38–45; Donald Raatz, U.S. Air Force AC-130 pilot who flew in support of Eagle Pull, Frequent Wind, and the Mayaguez rescue, telephone conversation with author, 16 October 2017; and George Bracken interview with Erin Matlack, 2001, Oral History, George Clooney Bracken Collection, AFC/2001/001/102068, Veterans History Project, American Folklife Center, Library of Congress, Washington, DC.

- Timothy Trebil, interview with author, 10 November 2017; and James Prothro, interview with author, 10 November 2017.

- DOD Personnel Policy letter to Raatz.

- Jordan J. Paust, “More Revelations about Mayaguez (and Its Secret Cargo),” Boston College International and Comparative Law Review 4, no. 1 (May 1981): 66.

- Paust, “More Revelations about the Mayaguez (and Its Secret Cargo),” 72.

- Jordan J. Paust, “The Seizure and Recovery of the Mayaguez,” Yale Law Journal 85, no. 6 (1976): 794.

- None of the Mayaguez histories suggest espionage, but the trial discovery recorded by Paust identifies several unanswered questions about the ship’s secret contents.

- Paust, “More Revelations about the Mayaguez (and Its Secret Cargo),” 69–70.

- Paust, “More Revelations about the Mayaguez (and Its Secret Cargo),” 71.

- Paust, “More Revelations about the Mayaguez (and Its Secret Cargo),” 73–74.

- DOD Dictionary of Military and Associated Terms (Washington, DC: Department of Defense, 2017), 201.

- “Impact of Congressional Cuts in Administration Economic Aid Requests for Indochina,” April 1975, box 13, General Subject file, “VietnamGeneral” folder, digital collections, GRFPL.

- Ron Nessen, “Draft of Presidential Speech to Congress,” 8 April 1975, box 13, General Subject file, “Vietnam-General” folder, digital collections, GRFPL.

- “Gerald R. Ford, 38th President of the United States: 1974–1977—Address Before a Joint Session of the Congress Reporting on United States Foreign Policy, 10 April 1975,” American Presidency Project (website), accessed 16 December 2017.

- The Reminiscences of Admiral Noel A. M. Gayler, U.S. Navy (Ret.), interviewed by Paul Stillwell in December 1983 (Annapolis, MD: U.S. Naval Institute Press, 2012), 289.

- The Reminiscences of Admiral Noel A. M. Gayler, U.S. Navy (Ret.), 296–97.

- Author interviewed or corresponded with nine Mayaguez veterans while researching this article: five Marines, two Navy, and two Air Force. They represent a mix of officer and enlisted. All spoke to the chaotic nature in the region as their units/vessels responded in various ways to events in Vietnam and Cambodia. The following four perspectives are representative: Timothy Trebil, 2d Battalion, 9th Regiment, veteran, interview with author, Arlington, VA, 10 November 2017; James Prothro, 2d Battalion, 9th Regiment, veteran, interview with author, Arlington, VA, 10 November 2017; Donald Raatz, USAF, Lockheed AC-130 pilot who flew in support of Eagle Pull, Frequent Wind, and the Mayaguez rescue, telephone conversation with author, 16 October 2017; and Scott Kelley, USN, veteran of the USS Schofield, email to author, 10 October 2017.

- 1975 USS Schofield FFG-3, HSL-33 DET-10, WESTPAC cruise book (San Diego, CA: Wallsworth Publishing, 1975), 50.

- “40th ARRS and 21st SOS Celebrate Ho Chi Minh’s Birthday May 19, 1975 NKP (No Audio),” YouTube, 15 October 2012, 8 mm camera video, 01:26.

- Leatherneck, September 1975, Mayaguez file, folder 3 of 4, Historical Resources Branch, Marine Corps History Division, Quantico, VA.

- A Resolution to Pay Tribute to American Servicemen Who Fought in Southeast Asia and to Their Families, S. Res. 171, 94th Cong. (1975).

- See Robert W. Doubek, Creating the Vietnam Veterans Memorial: The Inside Story (Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 2015).

- See box 39, Records of the Vietnam Veterans Memorial Fund, Manuscript Division Reading Room, Library of Congress.

- Frances Angerhofer letter to Hon Carlos Moorhead, congressman, 22d California District, 31 March 1982, box 39, Records of the Vietnam Veterans Memorial Fund, Manuscript Reading Room, Library of Congress, Washington, DC.

- See Doubek, Creating the Vietnam Veterans Memorial, 221; and Zeke Campfield, “El Reno Family Celebrates Return of Long-lost Husband, Father,” Oklahoman, 14 September 2012.

- See Al Bailey, President’s Page, letter to members (PDF), 26 October 2012, Koh Tang/ Mayaguez Veterans Organization website, 2, accessed 23 November 2020; and Dennis Green, Guest Book post, 27 April 2014, Koh Tang/ Mayaguez Veterans Organization website, accessed 23 November 2020, 43.

- John S. McCain, “McCain Address on Dedication of Mayaguez Memorial” (speech, U.S. Embassy, Cambodia, 11 November 1996), accessed via Koh Tang/Mayaguez Veterans Organization website.

- Homepage, Koh Tang/Mayaguez Veterans Organization website, accessed 10 February 2017.

- Donald Raatz, president’s update, Koh Tang/Mayaguez Veterans Organization website, 8 February 2016.

- 72 Section 556 of the National Defense Authorization Act for 2002, Pub. L. No. 107-107 (2001).

- Section 542, Bob Stump National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2003, Pub. L. No. 107-314 (2002).

- Recognizing Mayaguez Veterans Act, H.R. 1788, 115th Cong. (2017).

- DOD, “Secretary Carter Opens Vietnam War Commemoration Pentagon Corridor Honoring Vietnam Veterans and Their Families,” press release, 20 December 2016.

- Army Regulation 600-8-22, Military Awards (Washington, DC: Headquarters, Department of the Army, 25 June 2015), 30–36.