PRINTER FRIENDLY PDF

EPUB

AUDIOBOOK

Abstract: In an attempt to institutionalize the intelligence experiences gained by the American Expeditionary Forces in World War I, the U.S. Army published its first doctrinal publication on intelligence in 1920, Intelligence Regulations. On 18 August 1921, the Major General Commandant of the U.S. Marine Corps sent three copies of this classified Army publication to the commanding general at Marine Barracks, Quantico, Virginia. To understand what might cause this high-level transfer of an Army doctrinal publication, it is instructive to look at what was going on across the Marine Corps at this time—particularly in intelligence. Intelligence Marines often point to the 1939 reorganization of Headquarters Marine Corps and cite the creation that year of the staff M-2 as the birth of Marine Corps Intelligence, but many in the national intelligence community point to the creation of the Office of Strategic Services (1942–45) as the birth of the intelligence community; prior to that, there was no dedicated or formal U.S. intelligence service outside of the military. A look at how the intelligence lessons learned from World War I resulted in organizational changes in the interwar years reveals significant intelligence activity in the Marine Corps during that period and predates the 1939 reorganization of Headquarters Marine Corps.

Keywords: intelligence community, Marine Corps Intelligence, Headquarters Marine Corps reorganization, World War I intelligence, intelligence service, Division of Operations and Training, Military Intelligence Section, Division of Plans and Policies, staff M-2, Office of Strategic Services, Office of Naval Intelligence, American Legation U.S. naval attaché, A/ALUSNA, U.S. Army intelligence doctrine, Intelligence Regulations, On-the-Roof Gang, Communications Security Section

In an attempt to institutionalize the intelligence experiences gained by the American Expeditionary Forces (AEF) in World War I, the U.S. Army published its first doctrinal publication on intelligence in 1920, Intelligence Regulations. On 18 August 1921, the Major General Commandant of the U.S. Marine Corps sent three copies of this classified Army publication to the commanding general at Marine Barracks, Quantico, Virginia. The letter was signed by Brigadier General Logan Feland “by direction” and the receipt was returned signed by a future Commandant, Lieutenant Colonel Thomas Holcomb, then chief of staff to Brigadier General Smedley D. Butler.1

To understand what might cause this high-level transfer of an Army doctrinal publication, it is instructive to look at what was going on across the Marine Corps at this time. In the early years after World War I, veterans of the AEF worked to apply lessons learned on staff and unit organization, combined arms, and other tactics, techniques, and procedures to the organization of the Marine Corps for warfighting and at Headquarters Marine Corps. This was especially true of intelligence.

Intelligence Marines often point to the 1939 reorganization of Headquarters Marine Corps and cite the creation that year of the staff M-2 as the birth of Marine Corps Intelligence. Marines are not alone in the view that World War II or the run-up to it began the formal approach to the craft of intelligence. Many in the national intelligence community point to the creation of the Office of Strategic Services as the birth of the intelligence community; prior to that, there was no dedicated or formal U.S. intelligence service outside of the military. As former intelligence officer Dr. Mark Stout asserts, “Historians and practitioners generally date the origins of modern American intelligence to the Office of Strategic Services (1942–1945) and the National Security Act of 1947 which created the CIA and the U.S. Intelligence Community.”2 However, an analysis of how the intelligence lessons learned from World War I resulted in organizational changes in the interwar years reveals significant intelligence activity in the Marine Corps during that period and predates the 1939 reorganization of Headquarters Marine Corps.

Post–World War I Reorganization of the Marine Corps

Until a few years before World War I, the Marine Corps had essentially no Headquarters Staff as we think of it today. The Major General Commandant oversaw the Marine Corps through a small personal staff and three staff departments: Adjutant and Inspector, Quartermaster, and Paymaster. It was not until April 1911 that the Office of Assistant to the Commandant was created, headed by Colonel Eli K. Cole, who served as what today would be called a chief of staff.3 Colonel Cole was replaced in January 1915 by Colonel John A. Lejeune.

Since World War I began in August 1914, the Major General Commandant, as well as the secretary of the Navy and the chief of naval operations, had pushed for increases of manpower and materiel, to include larger staffs. This led to the Naval Act of 1916, which increased the Corps’ size by about 50 percent, from 344 officers and 9,921 enlisted to 597 officers and 14,981 enlisted.4 It also authorized emergency in- creases up to 693 officers and 17,400 enlisted, which occurred on 26 March 1917.5 The act allowed for 8 percent of the officers, or 55 of the 693, to serve in the staff departments.

By fall 1918—after Marines had fought in Belleau Wood, Soissons-Château-Thierry, and Saint-Mihiel—the 12th Major General Commandant, George C. Barnett, decided to create a planning section. On 19 December 1918, the Headquarters Planning Section was established and charged with “all matters pertaining to plans for operations and training, intelligence, ordnance, ordnance supplies and equipment.” At first, the Planning Section, under direct supervision of the Office of the Assistant to the Commandant, only had three officers.6

World War I was a driving factor in the decision to create a Planning Section, with intelligence as one of many functions identified for improvement based on shortcomings experienced during the war. During World War I, Marine officers interacted with and learned from other branches of the AEF and other armies, such as the French. The Army’s Military Intelligence Division (MID) and the U.S. Office of Naval Intelligence (ONI) were larger and more sophisticated than the Marine Corps’ intelligence efforts and staff organization. It is likely that the Marine Corps staff developed its own small intelligence section after World War I based on experience with the larger ONI and MID organizations.

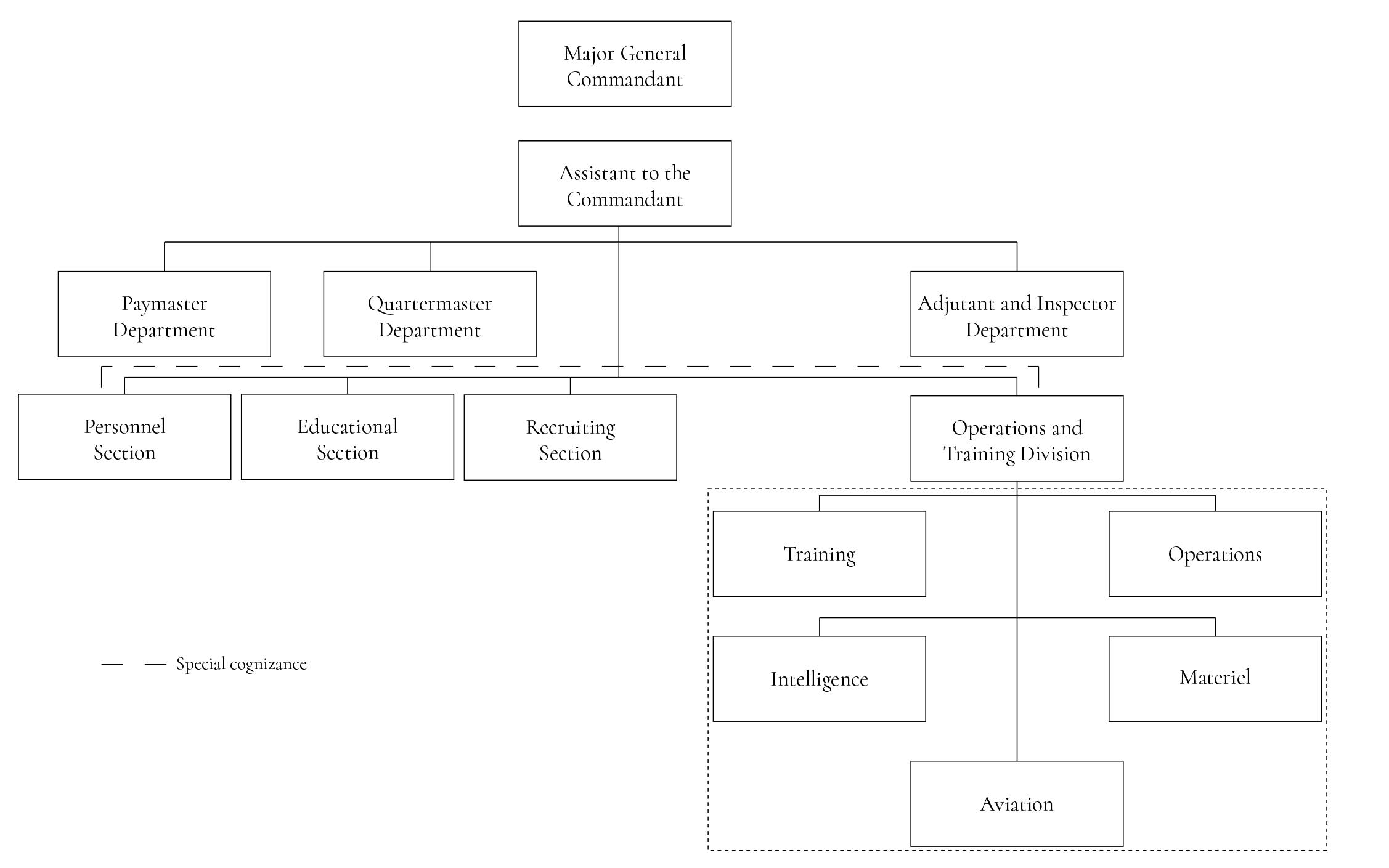

Table of organization, Headquarters Marine Corps, 1 December 1920. A Brief History of Headquarters Marine Corps Staff Organization, adapted by MCU Press

Major General Lejeune became the Major General Commandant on 1 July 1920 and brought his experience of commanding the 2d Division in the AEF and extensive use of a European staff system in those organizations to Headquarters. On 1 December 1920, Lejeune reorganized Headquarters and created the Division of Operations and Training, with Brigadier General Logan Feland as its first director. The Division of Operations and Training included Operations, Training, Materiel, Aviation, and Military Intelligence sections.7 Creation of the Military Intelligence Section represents the first permanent Marine Corps intelligence organization. Brigadier General Feland assigned Lieutenant Colonel Earl H. Ellis, who had been his brigade intelligence officer in the Dominican Republic, as the first head of the Military Intelligence Section.8

Military Intelligence Section Activities

In 1922, Brigadier General Feland wrote in the Marine Corps Gazette that he saw the Division of Operations and Training as essential for the Marine Corps to mitigate future losses in combat and increase organizational readiness. He stated that the Military Intelligence Section’s principal function was the “collection and compilation of intelligence useful to the Marine Corps, in carrying out its mission.”9

There is ample evidence of the Military Intelligence Section collecting and compiling information. Many Marines are familiar with the legend of Lieutenant Colonel Ellis writing Advanced Base Operations in Micronesia in 1921 and then being found dead in Palau in 1923 while on an intelligence or reconnaissance mission.10 What few Marines may know is that with no professional or career intelligence officers, all officers in the Division of Operations and Training could move between sections and perform a variety of duties as needed. Ellis, for example, simultaneously headed the Military Intelligence Section and wrote those advanced basing plans that guided Marine Corps war planning for the subsequent 25 years.

As evidenced by the Headquarters letter forwarding the 1920 Army doctrinal publication Intelligence Regulations, the Military Intelligence Section also took part in the Division of Operations and Training’s other efforts, such as “organization of units, matters of training, choice of most suitable arms and equipment, military schooling, etc.”11

On 10 January 1921, a month after the Military Intelligence Section was formed, it promulgated a “List of Intelligence Regulations, etc. Transmitted to Certain Marine Corps Units.”12 The list included items such as the aforementioned Intelligence Regulations, along with various other military orders, articles, and reports. A few excerpts from items on the list highlight the type of things this 40-day-old Headquarters office determined would be of use to Marine Corps Schools and “certain” field units.

“Front Line Intelligence, extract from an article in the Marine Corps Gazette, December 1920, by Major Ralph Stover Keyser.”13 Major Keyser had served as commanding officer of 2d Battalion, 5th Marines, June–July 1918 during battles in the Château-Thierry sector and the Aisne-Marne offensive; then, August 1918–August 1919, he served as Major General Lejeune’s assistant chief of staff, G-2 (Intelligence Department), in the 2d Division, AEF. The article was a tour-de-force of tactical intelligence support on intelligence functions at the division, regiment, and battalion level. Major Keyser noted, “Military intelligence is more than reliable information, it is reliable information furnished in time to permit appropriate action.”14 “Intelligence Service in the Bush Brigades and Baby Nations, Extracts from a 1920 report by Major Earl Ellis.”15 Ellis noted, “In executing the intelligence functions stated the most difficult problem of all is to force the personnel to realize that their mission is not to gather information of any kind and place it on file, as is generally the custom, but to gather pertinent information, put it in proper form for use and then place it in the hands of the person who can use it to best advantage—and this as quickly as possible.”16

“Functions of Intelligence Officers in War Plans, Extract from U.S. Army Instructions to Intelligence Officers by Military Intelligence Department, 1921.”17 This Army doctrine stated, “As the plan is built up, every portion should be submitted to you for attack as the enemy’s representative—this for the purpose of providing the means of disinterested construction [sic] criticism. Your mental attitude in doing this work should be that of the enemy’s Chief of Staff, who, supposedly having captured the plan, strives to make arrangements to circumvent it.”18

These examples show how the combined lessons of small wars and the AEF in World War I instructed these officers that newly formed Marine Corps intelligence staffs should focus on tactical and operational intelligence support that was very practical and directly tied to current operational planning and decision-making. However, the Military Intelligence Section was dividing its time between this type of “force development” activity (as it might be called today) and the need to do other longer-range planning and interagency coordination.

Brigadier General Feland noted that the Division of Operations and Training “has been charged with certain responsibility in regard to the policy to be followed in selecting the personnel for assignment to certain duties.”19 Examples of this would include detailing of Marines to the ONI, naval attaché duty, special training in areas such as communications intelligence, and special reconnaissance missions.

Service in ONI

The ONI was established in the Bureau of Navigation in March 1882 by Navy Department General Order No. 292, nearly 40 years before the fledgling Headquarters Military Intelligence Section.20 Marines served at ONI prior to the creation of the Corps’ Military Intelligence Section, with the first Marine, First Lieutenant Lincoln Karmany, being assigned to ONI in January 1893.21 Captain (later Major) William L. Reddles served as assistant naval attaché in Tokyo, Japan, from 1915 to 1918 and then served as a lieutenant colonel in ONI from 1920 to 1921. In the 1930s, there were often three to five Marine officers at ONI, most often serving in or leading the Far East and Latin American sections.22 For example, Captain Ronald Aubry Boone, who served as S-2, 4th Marine Regiment, in Shanghai at the start of the Sino-Japanese War in 1937, was pro- moted to major and assigned to ONI in 1939 as assistant head of the Far East Section.

While we do not have evidence that duty at ONI was viewed as career enhancing by Marines of that era, we do know that many Marines who served at ONI were later promoted to colonel and general officer ranks. A future Commandant (1934–37), Major John H. Russell Jr., came to ONI in 1913 after serving as commander of the Marine Detachment, American Legation, Peking (Beijing), China. In 1916, Major Russell worked with Navy Commander Dudley W. Knox on a reorganization plan for ONI that was approved by Secretary of the Navy Josephus Daniels on 1 October 1916. In early 1917, Major Russell took charge of Section A, Organization and Control of Agencies for the Collecting of Information, which included debriefing of commercial travelers as well as control of hired agents and informants.23 Lieutenant Colonel John C. Beaumont served in ONI in 1920, was promoted to colonel in 1926, commanded 4th Marines in 1933, and was promoted to brigadier general in 1935.24

Brigadier General Dion Williams is considered the father of amphibious reconnaissance based on his book Naval Reconnaissance, which he wrote in 1905–6 while a major on the instructor staff at the Naval War College.25 He served as a staff intelligence officer in ONI and on intelligence duty abroad from November 1909 to March 1913. From 1924 to 1925, as a brigadier general, he was director of operations and training at Headquarters and supervised the Military Intelligence Section.26

U.S. Naval Attachés Abroad

In 1910, the first of many Marines was sent to Tokyo to serve as assistant American Legation U.S. naval attaché in Tokyo for language training. Most notably, Captain Ralph Stover Keyser, who later served as Major General Lejeune’s G-2 in France, served as assistant naval attaché at the American embassy in Tokyo from January 1912 to February 1915. Marine officers served in Tokyo, gaining Japanese language capability, through summer 1941, when the decision was made to withdraw the naval attaché office from Japan. The two Marines evacuated in 1941 were Captain Bankson T. Holcomb Jr. and First Lieutenant Ferdinand W. Bishop.27 Holcomb would go on to serve as director of intelligence at Headquarters in 1957.

Marines were normally assigned as assistant naval attachés. Lieutenant Colonel James C. Breckinridge was the first Marine to serve as the naval attaché, being assigned to Christiania (now Oslo), Norway, in 1917 with the added duty of covering Denmark and Sweden. In the interwar years, more Marines served in unique or first-time attaché roles. Captain David R. Nimmer was sent to Moscow in March 1934 as the assistant naval attaché, but ended up as the second Marine naval attaché because the Navy officer assigned as naval attaché to Moscow turned down his orders.28 Perhaps the most famous Marine of this period to serve as an assistant naval attaché was Colonel Pedro A. del Valle, who later commanded the 11th Marine Regiment (Artillery) at Guadalcanal and the 1st Marine Division at Okinawa and would retire as a lieutenant general. Colonel del Valle served as assistant naval attaché in Rome, Italy, from 1935 to 1936 and was a military observer with the Italian Army during its campaigns in Ethiopia.29

Communications Intelligence

Department of the Navy communications intelligence began in the fashion of one-at-a-time, on-the-job training for experienced communications and linguist personnel. This activity was controlled by the director of naval communications within the Communications Security Section, which was formed in 1922. By 1926, the Communications Security Section began to conduct small training classes for officers, and the first class included Captain Leo F. S. Horan. By 1928, Communications Security Section began classes for enlisted intercept operators in a classroom that was constructed on the roof of the main Navy building in Washington, DC, earning intercept operators who graduated the course the nickname “On-the-Roof Gang” or OTRG. Two of the classes were entirely comprised of Marines.30

Some of the Marines detailed to Japan for foreign language training did follow-on tours of duty at radio intercept stations. First Lieutenant Alva B. Lass- well was sent to Tokyo for Japanese language training from 1935 to 1938, to the 16th Naval District’s C Station radio intercept station (Corregidor) in 1938–39, and Shanghai in 1939.31 Lasswell’s tour at C Station exposed him to the technical aspects of communications intelligence: cryptanalysis, traffic analysis, and translation, since all were performed at Corregidor in support of both the Asiatic Fleet and Army General Douglas MacArthur.32

Although not an activity of the interwar years, it is worth noting that experience gained by this small group of linguists and cryptologists in Japan and China directly contributed to the success of the U.S. Pacific Fleet in World War II (WWII). Alva Lasswell was the linguist and cryptologist who later decrypted and translated the message traffic in 1942 that led to the Battle of Midway and the 1943 traffic that led to the downing of Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto’s plane.33 It is also interesting to note that Marines were assigned to Fleet Radio Unit Pacific performing communications intelligence as WWII began, with Marines such as Bankson Holcomb taking a “direct support” radio intercept unit aboard USS Enterprise (CV 6) for the February 1942 Marshalls–Gilberts raids.

Special Reconnaissance

Special duty assignments—in this case of intelligence, reconnaissance, and related missions—were accounted for in the U.S. Navy regulations of 1920, which stated in article 127, section 2, of its chapter on general instructions to officers that “no officer of the Navy or of the Marine Corps shall proceed to a foreign country on special duty connected with the service except un- der orders prepared by the Bureau of Navigation or by the Major General Commandant as the case may be, and signed by the Secretary of the Navy.”34 While records do not note how many Marines were detailed to special duty assignments in the interwar years, the provision of Navy regulations citing the Major General Commandant’s authority to prepare such orders indicates anticipation that Marines would be used in this manner. Perhaps the most famous special duty assignment of a Marine during this period is the mission of Lieutenant Colonel Ellis to survey islands in East Asia. Ellis’s special duty was approved by the Major General Commandant and the secretary of the Navy. Unfortunately, the mission ended with Ellis’s death in Palau in 1923.35

Another example of a special duty reconnaissance mission is the work of then-major William Arthur Worton in China from 1935 to 1936.36 Major Worton, who as a platoon commander during World War I had been badly wounded in a gas attack in Belleau Wood, was assigned to ONI’s Far East Section after several tours of duty in China, including completion of the State Department’s Chinese language course in Beijing and a tour as an intelligence officer in 3d Brigade under Major General Smedley Butler. While serving at ONI, Worton proposed the fleet intelligence officer of the Asiatic Fleet be assigned an assistant who would be based in Hong Kong or Shanghai to recruit and deploy foreign agents to Japanese ports to observe and report on the Japanese Navy. Worton was sent to Shanghai to execute his plan, which he did undercover as a businessman. Worton was able to set up an agent network, but he recommended successive Marines assigned to this duty be designated assistant naval attachés because the proximity of Shanghai’s international settlement to the 4th Marines often meant running into fellow Marine officers who did not always believe he was there to start a business.

Organization and Manning

As noted earlier, the Division of Operations and Training also had the lead for “organization of units, matters of training, choice of most suitable arms and equipment, military schooling, etc.”37 Today, this would be called force development or even an occupational field sponsor role, although we note intelligence was not yet a Marine Corps military occupational specialty at this time. The Military Intelligence Section likely assisted the Division of Operations and Training in developing tables of organization and equipment for intelligence sections and units.

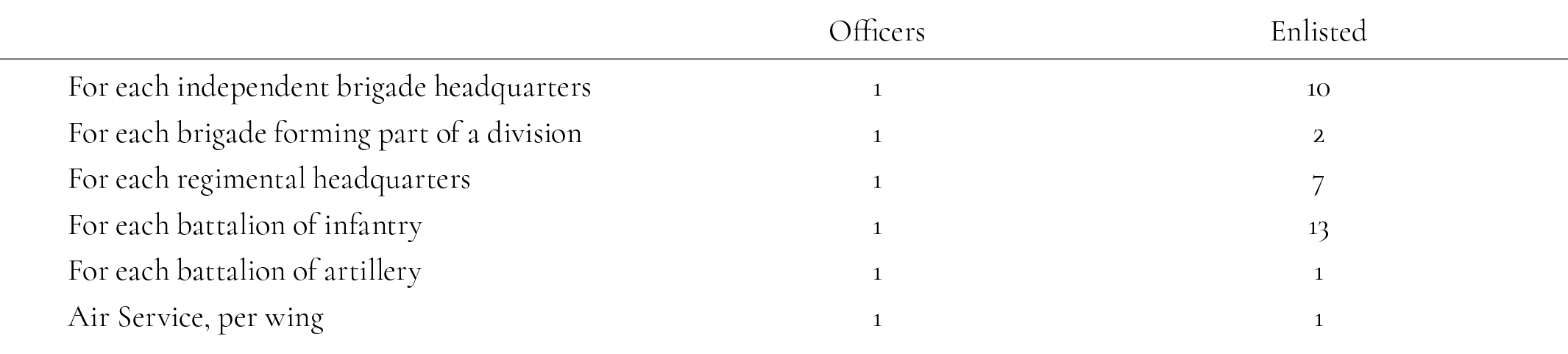

In 1921, the Major General Commandant authorized creation of combat intelligence personnel billets in deployed Marine Corps units.38 In the following year, the Marine Corps assigned a new four-section executive staff—including personnel, intelligence, operations and training, and supply—to brigades and infantry regiments. These staff sections did not use the conventional G-2 if the unit was commanded by a general and S-2 if the unit had a more junior commander. Rather, the convention was B-2 for brigade intelligence officers and R-2 for regiments. Finally, in 1925, planning tables of organization under consideration should the Marine Corps need to field divisions also showed the four-section executive staff.39 An example of the envisioned size of intelligence staffs and units at various echelons is shown above (table 1).40

The Military Intelligence Section also served as a conduit to the brigades for Army doctrinal publications. In addition to the aforementioned classified Intelligence Regulations, operational- and tactical-level Army publications, such as the Army’s Provisional Combat Intelligence Manual, were mailed directly to deployed brigades.41

Table 1. Authorized intelligence staff per unit.

MajGen Cmdt letter to Brigade Cmdr, First Provisional Brigade, U.S. Marine Corps, Port-au-Prince, Republic of Haiti, 1975-35-AO-15-rac, Subj. Combat Intelligence, 17 June 1921, box 5, Records of the U.S. Marine Corps, Division of Operations and Training, Intelligence Section, General Correspondence, 1919–1939, RG 127, NARA

Typically, officers were assigned as brigade/ regimental intelligence officers, while enlisted Marines served as scouts/observers, messengers, or topographical draftsmen.42 Since there was no intelligence military occupational specialty, recommendations were sent to the brigades to assist in screening Marines for duty in intelligence staffs and units. The screening criteria were:

- Especially smart, active, intelligent, and trustworthy.

- Sober and temperate habits.

- Physically fit for great strain and hardship.

- Keen observer; excellent eyesight and hearing.

- Accurate shot; deliberate and yet quick.

- Good judge of distance.

- Strong will power and determination.

- Courage, combined with coolness and self-reliance.

- Capable, adaptable, original and resourceful.

- Capable, adaptable, original and resourceful.

Evolution of Brigade Intelligence

During the interwar period, Marine Corps intelligence evolved at the tactical levels of the independent Marine brigade and its subordinate units; its initial B-2 and S-2 organizations were derived from the World War I experience. General John J. Pershing arrived in Europe in June 1917 with the first division of the AEF and decided to adopt the French staff system throughout the AEF. Intelligence became the second section, or G-2, of the AEF headquarters staff, and this convention was adopted in various forms at each echelon as more divisions, brigades, regiments, and battalions joined the AEF and personnel were sent to Allied intelligence training. Personnel designated to serve as intelligence officers were initially trained on document exploitation and prisoner-of-war interrogation at the British intelligence school at Harrow, but in August 1918, the AEF opened an intelligence training center at Langres, France. Intelligence students at Langres were trained to perform interrogations using actual captured German prisoners.44

The 5th Marine Regiment arrived in June 1917 with the first element of the AEF, and Marine units followed the AEF in creating intelligence staffs by taking personnel from line units, also taking advantage of the intelligence training schools set up in the field by the French, the British, and the AEF itself. By February 1918, the 6th Marine Regiment arrived and the 4th Brigade was at strength. The 1st Battalion, 6th Marines, is a good example of a Marine unit adjusting to the AEF staff system. The battalion was commanded by Medal of Honor Recipient Major John Arthur Hughes. As the battalion went through what today would be called reception, staging, onward movement, and integration, Major Hughes reached into his 75th Company and pulled Second Lieutenant Carlton Burr to be the battalion intelligence officer, or S-2. Burr in turn asked 75th Company for Sergeant Gerald C. Thomas, a future Assistant Commandant, to be the battalion intelligence chief.45

Following the AEF model of battalion S-2s having a reconnaissance element of about 28 scouts, observers, and snipers, Major Hughes allowed Second Lieutenant Burr and Sergeant Thomas to form a 25-man platoon of scout/observers who were also trained to sketch maps and troop positions, but over time Hughes acceded to demands from the line companies for the return of this manpower.46 Sergeant Thomas was only called back up to 1st Battalion, 6th Marines, headquarters to serve as acting S-2 when Burr was medically evacuated the day before the Battle of Belleau Wood. Major Hughes’s first order to Thomas was for a detailed map of the battalion’s position. It was common for S-2s of that period to spend as much effort plotting friendly positions as enemy positions.

Until 1917, brigade and independent battalion staffs were organized similarly to Headquarters, with three staff officers: adjutant, quartermaster, and paymaster. In the 1920s, veterans of World War I, whether recipients of intelligence support or actual veterans of these ad hoc intelligence staffs and units, were reassigned to deployed Marine brigades, where the lessons learned were put into practice. Even before the new brigade and regimental tables of organization were issued in 1922 and 1925, respectively, brigade and regimental commanders were often using their own resources to arrange four-section staffs.

During most of the interwar period, the Marine Corps had three brigades deployed. The 1st Marine Brigade was located in Haiti/Dominican Republic before moving its flag to Quantico in 1933. The 2d Marine Brigade was located in Nicaragua, and the 3d Marine Brigade was stationed in China. The first-hand experiences of Marines on the ground in these areas led to the earlier-mentioned practice of Marines serving as heads of the Far East and Latin American Sections of ONI. As Navy intelligence historian Captain Wyman H. Packard noted, “In the mid-1930s, some of the principal sources for ONI’s Far East [Section] (OP-16-B-11) were reports from Marine Corps intelligence officers stationed in China. Pertinent reports on Japanese-controlled islands in the Pacific were also submitted by overseas units of the Marine Corps.”47

In 1927, the 4th Marine Regiment was sent to Shanghai, China, to protect key international zones and buildings during the Chinese civil war. The war— or, as some called it, the Communist insurgency—was between the Nationalist Party of China and the Communist Party of China, but Japan took advantage of the 10 years of conflict to make gains on the periphery of China. Japan invaded Manchuria in 1931. Marines in Shanghai and with the Marine Detachment, Ameri- can Legation Guard, Peking (Beijing), were referred to as the China Marines and came to know the country well, but perhaps more importantly, they were able to learn much about their future enemy, the Japanese military, during this period.

The Marine Corps placed the 3d Brigade in Tientsin to take command of all Marines in China. The first commanding general was Brigadier General Smedley D. Butler, a veteran of the Marine expedition to China in 1900 to relieve the Legation Quarter and put down the Boxer Rebellion.48 Major Earl C. Long served as the 3d Brigade B-2 and Captain Evans Fordyce Carl- son served as the operations and training officer, 3d Marine Brigade in Tientsin, and then as intelligence officer for 4th Marines in Shanghai.49 Carlson would return to China in 1937 in various positions, including as an observer with Chinese 8th Route Army, where he was able to study Japanese Army capabilities first-hand.50

The 3d Brigade was planning for the possibility that the Marine Detachment, American Legation, Peking (Beijing), would need to be relieved in similar fashion to the relief column that fought its way from Tientsin to Beijing during the Boxer Rebellion. In March 1928, Major Long completed a roster listing the forward echelon of a B-2, which he planned would consist of 2 officers and 10 enlisted Marines.51 Ten enlisted Marines was what Headquarters had published in 1921 as the table of organization for a B-2 section in a deployed independent brigade. The composition of the B-2’s 10 enlisted Marines was listed as follows in Major Long’s plan:

Sergeant In charge of field party

PFC Field party and blueprint man

2 x PFCs Draftsmen

PFC Clerk

PFC Motorcycle orderly

2 x Private Field party

Private Moving picture operator

Private Chauffer52

In Shanghai and Beijing, members of the OTRG, consisting of Navy staff and a detachment of Marines, targeted Japanese diplomatic communications, but also intercepted and relayed information regarding Japanese tactics, orders of battle, and objectives to Washington, DC, during the Japanese invasion of Manchuria and later attacks on Shanghai.53 The Navy established radio security stations in Shanghai during 1924 near the Asiatic Fleet headquarters and in Beijing, with the Marine detachment, during 1927. The Radio Security Station, Shanghai, or the Fleet Communication Intelligence Unit, Shanghai, as it was known at various times, is believed to be the Navy’s first shore-based intercept station.54

Due to equipment and personnel shortages, the station in Shanghai was closed from 1929 to 1935. During this period, Marine Corps intercept operators worked in the Beijing station. However, by the mid-1930s, it was decided to close the station in Beijing, effective 28 July 1935.55 At that point, the Shanghai radio security station at 4th Marines was reestablished, operating from 1935 to 1940.

On 5 March 1932, the chief of naval operations forwarded a letter to the commanding officer of Marine Detachment, Beijing, commending “the excellent work and progressive development of the Intercept Station, Peiping, for the past four years, and especially during the past six months.”56 A letter dated 26 October 1935 discussing Marine Corps intercept operators at the Beijing station noted nine enlisted Marines assigned in 1932 and 1933 and eight Marines assigned in 1934.57 Unfortunately, the Navy had asked for 20 Marine Corps intercept operators, and these lower numbers led to the 1935 closing of the Beijing station. The Marine Corps provided the officer-in-charge for the reactivated Shanghai intercept station with Captain Shelton C. Zern (1935–38), Captain Kenneth H. Cornell (1937–39), and Captain Alva B. Lasswell (1939–40), each serving as the 4th Marines assistant communications officer, the station officer-in-charge’s official cover.58

In the 1920s and well into the 1930s, Navy fleet commanders also had small staffs and often had the fleet Marine officer serve as the fleet intelligence officer. For example, Brigadier General Dion Williams served as fleet Marine officer of the U.S. Atlantic Fleet and fleet intelligence officer of that fleet from December 1907 to October 1909.59

In July 1937, war between China and Japan erupted in earnest. Admiral Harry E. Yarnell, commander of the Asiatic Fleet, moved his flagship, the heavy cruiser USS Augusta (CA 31) to Shanghai. Admiral Yarnell met regularly with the U.S. consul general and Colonel Charles F. B. Price, the commanding officer of 4th Marines.60 The fleet intelligence officer of the Asiatic Fleet, Lieutenant Henry H. Smith-Hutton, was a Japanese linguist, while the 4th Marines’ R-2, Captain Ronald Aubry Boone, was a Chinese linguist. Together, they were able to keep the Asiatic Fleet and 4th Marines well-informed on the war.

Boone’s assistant R-2 was First Lieutenant Victor H. Krulak, who would retire as a lieutenant general and commanding general of the Fleet Marine Force Pacific. Krulak was able to observe Japanese offensive operations on the Yangtze River during 1937 and wrote an intelligence information report on Japanese landing craft titled Japanese Assault Landing Operations: Yangtze Delta Campaign, 1937. The report highlighted Japanese boats “which were obviously designed to negotiate surf and shallow beach landings.”61 The report went on to note “the overhanging square bow of the Type ‘A’ boat is hinged about 18 inches above the water line so that the entire bow structure can be lowered, thus making a landing ramp for troops and rolling vehicles.”62 Since this was a problem that had vexed Marines for some time, upon returning to the United States, Krulak followed his report through ONI to the Bureau of Ships to see what was being done with the information. The staff in the bureau thought the report had reversed the labeling of the bow and the stern and so had ignored it. Once Krulak explained that the photos were labeled properly, the staff became much more interested in his report.63

The brigades in Haiti/Dominican Republic and Nicaragua appear less interesting from an intelligence perspective than the 3d Brigade in China, except for aviation support. Lieutenant Colonel Kenneth J. Clifford noted in his work Progress and Purpose, “Marine air served in Santo Domingo from February 1919 until July 1924, in Haiti from March 1919 to August 1934, and in Nicaragua from 1927 to 1933.”64 The Marine Corps established the School of Aerial Observation at Quantico during mid-1926 in response to early lessons learned by Marines in the Caribbean, where Marine Observation Squadron 9 was stationed in Haiti and Aviation Squadron, 2d Brigade, was stationed in Nicaragua. The history of Marine Corps Base Quantico notes that “Marine aviators conducted two extensive courses at the School of Aerial Observation at Quantico during 1926, and students worked directly with the 5th Regiment to perfect air-ground coordination.”65 We close this section on the Marine brigades with an anecdote on the relations between 3d Marine Brigade and the Asiatic Fleet. The 3d Marine Brigade was under command of the Asiatic Fleet, and while some equipment and supplies were procured centrally by the Headquarters Quartermaster Department, certain Navy funds were managed by the fleet. In November 1927, the 3d Brigade B-2, Major Long, sent a request to the Asiatic Fleet for additional “intelligence funds” for paid agents and translators. On 14 December 1927, Rear Admiral Mark L. Bristol, commander in chief of the Asiatic Fleet, wrote to the commanding general of 3d Brigade, “It is the Commander in Chief’s policy not to employ paid agents. However, he would like to have the Commanding General’s comments regarding this matter.”66 Brigadier General Butler replied on 29 December 1927 that he agreed “information from paid agents cannot be relied upon in its entirety.” However, he went on, “with a system such as the Brigade Intelligence Section has for checking the information these paid agents submit, this is a source of information that we cannot afford to neglect for the small amount of money involved.”67 This exchange ended well, but it points to one reason the Major General Commandant had been pressing for new policy and doctrine on the command relationships between fleet and Marine commanders ashore.

Creation of the Fleet Marine Force

Major General Lejeune became the Major General Commandant on 1 July 1920. Having commanded the 4th Marines and 2d Army Division in World War I, Lejeune felt the Marine Corps needed revised policy and doctrine for command and control of large Marine formations ashore. In 1916, he wrote, “All, I believe, will agree that our training as an Advance Base organization, both as a mobile and as a fixed defense force, will best fit us for any or all of these roles [seize, fortify, and hold a port], and that such training should, therefore, be adopted as our special peace mission.”68

In February 1922, Major General Lejeune sent a memorandum to the General Board of the Navy stating, “The primary war mission of the Marine Corps is to supply a mobile force to accompany the Fleet for operations ashore in support of the Fleet.”69 Clearly, this would drive a need for standing Marine brigades with organizations and equipment to enable them to be a “mobile force,” defined command relationships during “operations ashore,” and related technical support capabilities such as intelligence. Fleet maneuvers were conducted in the 1920s that included seizing and defending advance bases with the Marine Corps exercise force designated the Marine Corps Expeditionary Force (MCEF).

Major General Lejeune retired in 1929, and it was not until Major General Ben H. Fuller became Commandant the following year that the pace of development of Lejeune’s envisioned mobile force would accelerate. In 1933, Major General John H. Russell, assistant to the Commandant, recommended dropping the term expeditionary force and using a term that better conveyed the role of Marines within the fleet: the Fleet Marine Force (FMF). On 7 December 1933, the secretary of the Navy created the FMF by issuing Navy Department General Order 241.70

Marine Corps Schools (MCS) at Quantico had started work in 1931 on a tentative text to be titled Marine Corps Landing Operations. Progress had been slow, and knowing that the approval of the FMF was imminent, in November 1933 classes were cancelled and MCS instructors and students prepared a detailed outline of the manual. By June 1934, the Tentative Manual for Landing Operations was available in mimeograph form for use by the 1934–35 school year’s classes.71 The manual was revised and reproduced in various forms annually until 1939, when the definitive version was is- sued as Landing Operations Doctrine, United States Navy 1938, Fleet Training Publication 167 (FTP-167).72 Landing Operations Doctrine, United States Navy 1938 was used with minor changes through World War II.

Landing Operations Doctrine, United States Navy 1938 contained dozens of references to intelligence and reconnaissance. It emphasized the importance of a detailed intelligence plan that compared data required for the mission to the data available on the area of operations and development of a plan for collecting the additional information needed to conduct the operation. This in turn would determine the “size, composition, and tasks of the reconnaissance force dispatched to the theater of operations.”73 Chapter 4, “Ship to Shore Movement,” offers a list of reasons to use rubber landing craft, one of which was “landing of intelligence agents.”74 Chapter 2, “Task Organization,” recommended creating a reconnaissance group and noted “photographs and panoramic sketches executed by surface craft or submarines, and oblique aerial photographs from seaward will be a great assistance” to boat group, fire support groups, and troop commanders.75

On 18 December 1934, Marine Corps General Order No. 84 was issued designating the 1st Marine Brigade at Quantico as the first FMF brigade headquarters, with “the Fifth Marines constituting the nucleus on the East Coast and the Sixth Marines on the West Coast.”76 Major General Lejeune’s former G-2, Ralph Keyser, wrote, “The establishment of the Fleet Marine Force and the inclusion of a force of Marines as an integral part of the United States Fleet organization should give great satisfaction to those interested in the welfare of the Marine Corps.”77

Pre–World War II Reorganization of Headquarters Marine Corps

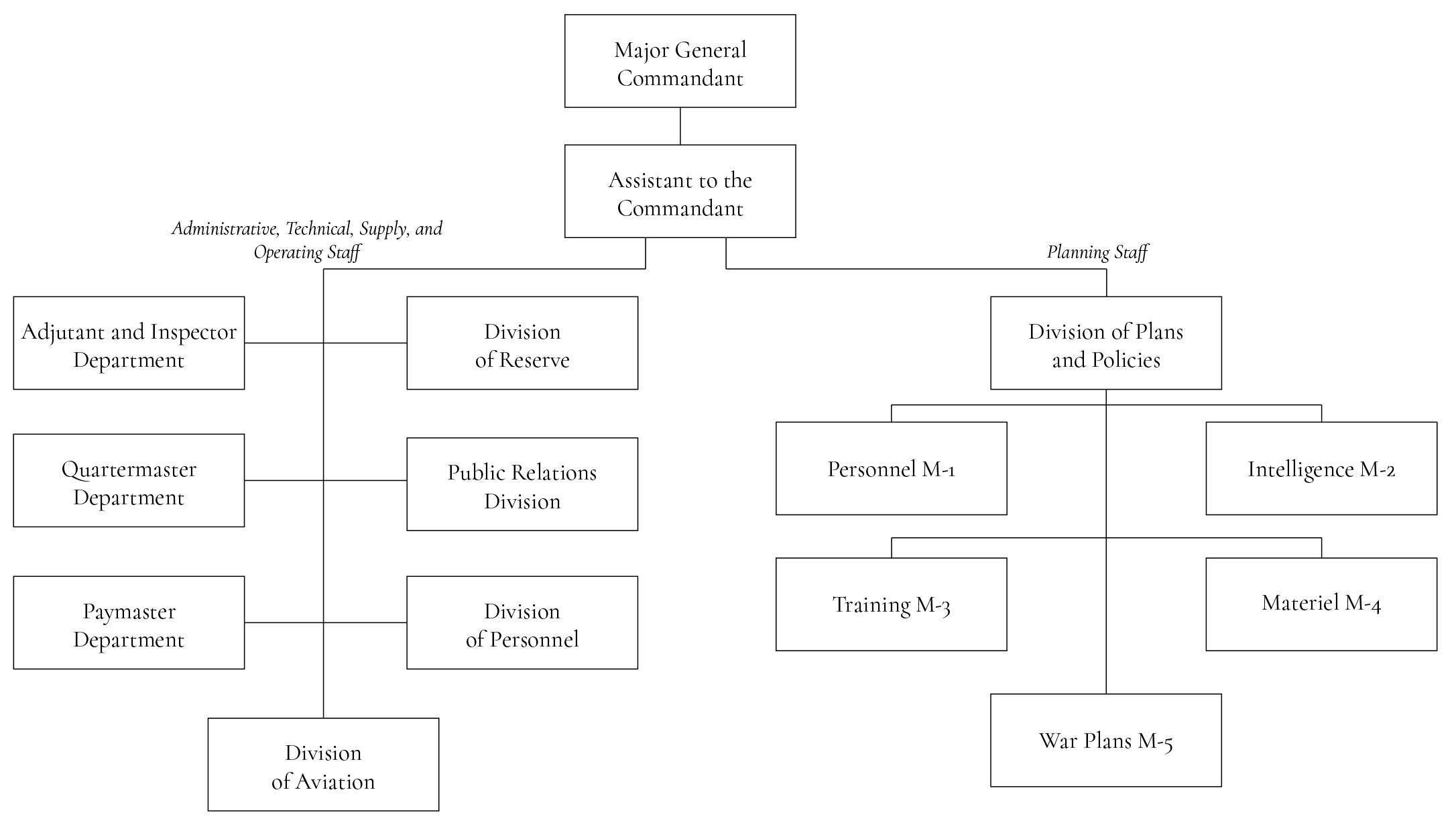

On 21 April 1939, Major General Thomas Holcomb issued Headquarters Memorandum No. 1–1939 on staff organization and procedures, in which the Division of Operations and Training was redesignated the Division of Plans and Policies.78 According to A Brief History of Marine Corp Staff Organization,

popularly known as “Pots and Pans,” the new Division retained the same subdivisions as the old with the standard number designations of a general or executive staff, but designated “M” rather than “G.” Under the supervision of a Director, the Division contained the standard M-l, Personnel; M-2, Intelligence; M-3, Training; and M-4, Supply and Equipment Sections and an M-5, War Plans Section, which was to be abolished in the fall of 1941, with M-5 functions being absorbed by M-3.79

Table of organization, Headquarters Marine Corps, 1 August 1941. A Brief History of Headquarters Marine Corps Staff Organization, adapted by MCU Press

The Division of Plans and Policies did not have the authority to execute policy, only to formulate recommendations to the Major General Commandant, who in turn would issue orders to the administrative staff.

Mark Stout has written on the importance of the World War I experience to the creation of an intelligence community in the United States, noting, “The standard origin myth of modern American intelligence has the period from World War II to the passage of the National Security Act in 1947 as the seminal period. It is clear that many of the artifacts, values, and assumptions that exist in today’s Intelligence Community date back to World War I.”80

The first director of the M-2 is believed to be Major David A. Stafford. An article published on the occasion of Brigadier General Stafford’s retirement noted that “from 1935 to 1940 he served variously as a ‘sea soldier’ aboard the ‘USS West Virginia,’ and as officer in charge of intelligence in the Division of Plans and Polices at Marine Corps Headquarters in Washington, D.C.”81

Intelligence Marines have traditionally observed the Headquarters reorganization of April 1939 and creation of the M-2 as the birthdate of Marine Corps intelligence. With all deference to the trailblazing work of Major Stafford and the officers who succeeded him throughout the World War II era, given the facts outlined above, the true formal birth of Marine Corps intelligence occurred on 1 December 1920 with Lejeune’s establishment of the Military Intelligence Section in the Division of Operations and Training. It seems on 1 December 2020, Intelligence Marines around the world should be saying to each other, “Happy 100th Birthday, Marine!”

•1775•

Endnotes

- MajGen Cmdt letter to CG Quantico, U.S. Marine Corps, 1975-35-AO-47-cel.-56, Subj. Intelligence Regulations, 18 August 1921, box 5, Division of Operations and Training, Intelligence Section, General Correspondence, 1919–1939, Record Group (RG) 127, National Archives and Re-cords Administration (NARA).

- Mark Stout, “World War I and the Birth of American Intelligence Culture,” Intelligence and National Security 32, no. 3 (2017): 378,https://doi.org/10.1080/02684527.2016.1270997.

- Kenneth W. Condit, Maj John H. Johnstone, and Ella W. Nargele, A Brief History of Headquarters Marine Corps Staff Organization (Washington, DC: Historical Division, Headquarters Marine Corps, 1971), 8.

- Naval Appropriations Act of 1916, Pub. L. No. 64-241 (1916).

- Maj Edwin N. McClellan, The United States Marine Corps in the World War (Washington, DC: Historical Branch, G-3 Division, Headquarters Marine Corps, 1920).

- Condit, Johnstone, and Nargele, A Brief History of Headquarters Marine Corps Staff Organization, 11.

- Condit, Johnstone, and Nargele, A Brief History of Headquarters Marine Corps Staff Organization, 12.

- David J. Bettez, “Quiet Hero: MajGen Logan Feland,” Marine Corps Ga- zette 92, no. 11 (November 2008): 61.

- BGen Logan Feland, “The Division of Operations and Training Headquarters U.S. Marine Corps,” Marine Corps Gazette 7, no. 1 (March 1922): 42.

- Earl H. Ellis, Advanced Base Operations in Micronesia, Fleet Marine Force Reference Publication 12-46 (Washington, DC: Headquarters Marine Corps, 1992).

- Feland, “The Division of Operations and Training Headquarters U.S. Marine Corps,” 41.

- “Instructions on Marine Corps Intelligence,” letter CF-152-AO-15, 10 January 1921, box 5, Division of Operations and Training, Intelligence Section, General Correspondence, 1919–1939, RG 127, NARA.

- “Instructions on Marine Corps Intelligence,” original emphasis removed.

- Maj Ralph S. Keyser, “Military Intelligence,” Marine Corps Gazette 5, no. 4 (December 1920): 321.

- “Instructions on Marine Corps Intelligence,” original emphasis removed.

- Maj Earl Ellis, Intelligence Service in the Bush Brigades and Baby Nations (Washington, DC: Headquarters Marine Corps, 1920), enclosure to “Instructions on Marine Corps Intelligence,” original emphasis removed.

- “Instructions on Marine Corps Intelligence,” original emphasis removed.

- U.S. Army Instructions to Intelligence Officers, 1921, enclosure to “Instructions on Marine Corps Intelligence.”

- Feland, “The Division of Operations and Training Headquarters U.S. Marine Corps,” 42.

- Capt Wyman H. Packard (USN), A Century of U.S. Naval Intelligence (Washington, DC: Office of Naval Intelligence and the Naval Historical Center, 1996), 2.

- W. H. Russell, “The Genesis of FMF Doctrine: 1879–1899,” Marine Corps Gazette 35, no. 4 (April 1951): 57; and Packard, A Century of U.S. Naval Intelligence, 7.

- Packard, A Century of U.S. Naval Intelligence, 344–53.

- Packard, A Century of U.S. Naval Intelligence, 41, 331.

- BGen John C. Beaumont biographical file, “Military History of BGen John C. Beaumont,” Historical Reference Branch, Quantico, VA.

- Maj Dion Williams, Naval Reconnaissance: Instructions for the Reconnaissance of Bays, Harbors, and Adjacent Country (Washington, DC: Govern- ment Printing Office, 1906).

- BGen Dion Williams biographical file, “Military History of BGen Dion Williams,” 30 September 1925, Historical Reference Branch, Quan- tico, VA, hereafter “Military History of BGen Dion Williams.”

- Packard, A Century of U.S. Naval Intelligence, 367.

- Packard, A Century of U.S. Naval Intelligence, 69.

- LtGen Pedro A. del Valle biographical file, “Biography, Lieutenant General Pedro A. del Valle, USMC (Ret),” AH-1265-HPH, 3 January 1951, Historical Reference Branch, Quantico, VA.

- Frederick D. Parker, Pearl Harbor Revisited: U.S. Navy Communications Intelligence, 1924–1941, series 4: World War II, vol. 6, 3d ed. (Fort George C. Meade, MD: National Security Agency, Center for Cryptologic History, 2013), 10–11. OTRG was often applied to all radio intercept operators regardless of whether they had graduated from the OTRG school.

- Packard, A Century of U.S. Naval Intelligence, 370. C Station was also referred to as CAST.

- Robert Louis Benson, A History of U.S. Communications Intelligence during World War II: Policy and Administration, series 4: World War II, vol.6 (Fort George C. Meade, MD: National Security Agency, Center for Cryptologic History, 1997).

- Dick Camp Jr., “Listening to the Enemy: Radio Security Stations, China—‘Get Yamamoto’,” Leatherneck 87, no. 1, January 2004, 40–43.

- United States Navy Regulations, 1920 (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1920), 40.

- LtCol P. N. Pierce, “The Unsolved Mystery of Pete Ellis,” Marine Corps Gazette 46, no. 2 (February 1962): 34–40.

- Dennis L. Noble, “A US Naval Intelligence Mission to China in the 1930s,” Studies in Intelligence 50, no. 2 (2006).

- Feland, “The Division of Operations and Training Headquarters U.S. Marine Corps,” 41.

- 38 MajGen Cmdt letter to Brigade Cmdr, First Provisional Brigade, U.S. Marine Corps, Port au Prince, Republic of Haiti, 1975-35-AO-15-rac, Subj. Combat Intelligence, 17 June 1921, box 5, Division of Operations and Training, Intelligence Section, General Correspondence, 1919–1939, RG 127, NARA, hereafter MajGen Cmdt letter to brigade cmdr.

- Condit, Johnstone, and Nargele, A Brief History of Marine Corps Staff Organization, 15.

- MajGen Cmdt letter to brigade cmdr.

- Provisional Combat Intelligence Manual, Document 1041 (Washington, DC: War Department, 1920).

- MajGen Cmdt letter to brigade cmdr.

- Provisional Combat Intelligence Manual.

- John Patrick Finnegan and Romana Danysh, Military Intelligence, Army Lineage Series (Washington, DC: Department of the Army, 1998), 33

- Allan R. Millett, In Many a Strife: General Gerald C. Thomas and the U.S. Marine Corps, 1917–1956 (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 1993), 26.

- Finnegan and Danysh, Military Intelligence, 35.

- Packard, A Century of U.S. Naval Intelligence, 43.

- Trevor K. Plante, “U.S. Marines in the Boxer Rebellion,” Prologue 31, no. 4 (Winter 1999). Marine Corps officers were not eligible for the Medal of Honor until 1913, but given the slow pace of promotions, being advanced in numbers was a high reward. Then-1stLt Butler was advanced two ranks and brevetted a captain for bravery in action during the July 1900 battle for Tientsin.

- BGen Evans F. Carlson biographical file, “Brigadier General Evans F. Carlson,” AHC-1265-hph, 5 March 1951, Historical Reference Branch, Marine Corps History Division, Quantico, VA, hereafter Carlson biographical file.

- Carlson biographical file.

- 3d Brigade Proposed Forward Echelon, Plan II, March 1928, draft B-2 section transmitted to Headquarters Intelligence Section by Maj Earl C. Long, box 1, Division of Operations and Training, Intelligence Section, General Correspondence, 1919–1939, RG 127, NARA.

- 3d Brigade Proposed Forward Echelon, Plan II.

- Camp, “Listening to the Enemy.”

- “Security Group in China, 1928 through 1945,” Cryptolog 7, no. 2 (Win- ter 1986): pull-out supplement, A-6.

- “Security Group in China, 1928 through 1945,” A-4.

- Camp, “Listening to the Enemy,” 41.

- “Security Group in China, 1928 through 1945,” A-4.

- Camp, “Listening to the Enemy.”

- “Military History of BGen Dion Williams.”

- Packard, A Century of U.S. Naval Intelligence, 393.

- 1stLt Victor H. Krulak, Japanese Assault Landing Operations: Yangtze Delta Campaign, 1937 (Washington, DC: U.S. Marine Corps, 1937) as reproduced in LtCol John J. Guenther, The Transformation and Professionalization of Marine Corps Intelligence (Quantico, VA: Marine Corps Intelligence Activity, 2017), 86.

- Krulak, Japanese Landing Operations, 94.

- Guenther, The Transformation and Professionalization of Marine Corps Intelligence, 86.

- LtCol Kenneth J. Clifford, Progress and Purpose: A Developmental History of the U.S. Marine Corps, 1900–1970 (Washington, DC: History and Museums Division, Headquarters Marine Corps, 1973), 38.

- LtCol Charles A. Fleming, Capt Robin L. Austin, and Capt Charles A. Braley III, Quantico: Crossroads of the Marine Corps (Washington, DC: History and Museums Division, Headquarters Marine Corps, 1978), 52.

- Asiatic Fleet Cmdr in Chief letter to CG 3d Brigade, Subj: “Intelligence Funds,” 14 December 1927, box 1, Division of Operations and Training, Intelligence Section, General Correspondence, 1919–1939, RG 127, NARA.

- CG 3d Brigade letter to the Asiatic Fleet Commander in Chief, Subj: “Intelligence Funds,” 29 December 1927, box 1, Division of Operations and Training, Intelligence Section, General Correspondence, 1919–1939, RG 127, NARA. The letter requested $500 per month in intelligence funds, of which $200 was for paid agents.

- John A. Lejeune, “The Mobile Defense of Advance Bases by the Marine Corps,” Marine Corps Gazette 1, no. 1 (March 1916): 2.

- MajGen Cmdt memo to General Board dated 11 February 1922, Subject: Future Policy for the Marine Corps as Influenced by the Conference on the Limitation of Armament (Record 432) as cited in Clifford, Progress and Purpose, 30.

- Millett, In Many A Strife, 113.

- Clifford, Progress and Purpose, 140.

- Landing Operations Doctrine, United States Navy 1938, FTP-167 (Washing- ton, DC: Office of Naval Operations, Division of Fleet Training, 1938).

- Landing Operations Doctrine, United States Navy 1938, 6.

- Landing Operations Doctrine, United States Navy 1938, 61.

- Landing Operations Doctrine, United States Navy 1938, 33.

- “Transition of the Fleet Marine Force,” Marine Corps Gazette 20, no. 1 (February 1936): 7.

- LtCol Ralph S. Keyser, “The Fleet Marine Force,” Marine Corps Gazette 18, no. 1 (February 1934): 51.

- T. Holcomb, Headquarters Memorandum No. 1–1939, Subject: Staff Organization and Procedure, Headquarters, U.S. Marine Corps, 21 April 1939, RG 127, NARA.

- Condit, Johnstone, and Nargele, A Brief History of Marine Corps Staff Organization, 17.

- Stout, “World War I and the Birth of American Intelligence Culture,” 378.

- “Gen Stafford Retired from Marines June 30,” Press-Republican (Platts- burgh, NY), 21 July 1949, 3.