PRINTER FRIENDLY PDF

EPUB

AUDIOBOOK

Abstract: It is widely believed that the Marine Corps’ participation in World War I was only grudgingly allowed. The U.S. Army and General John J. Pershing are often cast as being vehemently opposed to Marines being assigned to frontline units or actively participating in combat. While there is no evidence that Pershing advocated against using Marines, other than his opposition to creating an all-Marine division, there is little direct evidence that he let his preference for the Army override his professional judgment in employing Marines in the American Expeditionary Forces. If the Corps ever had a bête noir, it seems it was General Pershing. However, while Pershing’s personal views about Marines can only be surmised, his decisions on their employment in the AEF indicate that he was guided by the demands of war and military logic rather than personal pique. This article attempts to seek the truth of how Pershing’s purported attitudes toward Marines affected his decisions regarding Marine employment in the AEF.

Keywords: General John J. Pershing, American Expeditionary Forces, AEF, Marines in World War I, anti-Marine sentiments, inter-Service rivalry, all-Marine AEF division, 4th Brigade of Marines, 5th Brigade of Marines, Fifth Regiment, Major General George Barnett, Colonel John A. Lejeune, Brigadier General Charles Doyen, Brigadier General Smedley D. Butler, Brigadier General Eli Cole, Belleau Wood, Marine replacement strength

Most Marines agree that the modern U.S. Marine Corps earned its right to be counted as one of America’s premier fighting forces during World War I on the battlefields of France. Its success in those battles, especially the Battle of Belleau Wood, gave birth to a Corps with a new vision of its capabilities and role in the defense of the United States.

But it is also widely believed that the Corps’ participation in World War I was only grudgingly allowed. The U.S. Army and specifically General John J. Pershing are often cast as being vehemently opposed to Marines being assigned to frontline units or actively participating in combat. While there is no evidence that Pershing advocated against using Marines, other than his opposition to creating an all-Marine division, there is little direct evidence that he let his preference for the Army override his professional judgment in employing Marines in the American Expeditionary Forces (AEF).

MajGen George Barnett, 12th Commandant of the Marine Corps. Historical Reference Branch, Marine Corps History Division, official U.S. Marine Corps photo

The accusations of Pershing denying Marines any meaningful role in the AEF usually include: trying to subsume their unique culture into the Army’s by forcing them to wear Army uniforms and use Army equipment; sidelining their participation by using them for labor parties; relieving the 4th Brigade of its Marine Corps commander and replacing him with an Army general; envying the glory and recognition garnered by the Marines following their victory at Belleau Wood, attempting to prevent them from achieving even greater glory by limiting their participation in future battles; and, finally, preventing the creation of a Marine division. As the AEF commander, Pershing is often accused of being personally responsible for all of these affronts and is said to have become “furious” when forced to accept the Marines into the AEF. As a result, one military warfare history instructor claimed, “his actions would become an outward and visible sign of an inward and seething resentment.”1 If the Corps ever had a bête noir, it seems it was General Pershing. Pershing’s memoirs are very reticent regarding Marines. He wrote that the 5th and 6th Marines became “a part of our forces at the suggestion of Major General George Barnett, then Commandant of the Marine Corps, and with my approval.” He further commented that the AEF’s 2d Division enjoyed an advantage in having the 5th and 6th Regiments in its ranks, giving it “well trained troops” early in the war.2 These matter-of-fact statements indicate neither favoritism nor antipathy regarding Marines. They are hardly a ringing endorsement of the Marine Corps, but neither are they the comments of someone resentfully grinding an axe. While Pershing’s personal views about Marines can only be surmised, his decisions on their employment in the AEF indicate that he was guided by the demands of war and military logic rather than personal pique. An objective look at the relationship between the Marine Corps, the Army, and General Pershing suggests the friction between them was not necessarily one of jealousy and inter-Service rivalry. It was more likely the result of natural bureaucratic friction as the Marines struggled to quickly integrate themselves into the machinery of the Army. While this friction certainly irritated the Marines, the Corps’ leaders also recognized that its causes were legitimate and they addressed them as effectively as they could. This article attempts to seek the truth of how Pershing’s purported attitudes toward Marines affected his decisions regarding Marine employment in the AEF.

Organization and Equipment

The National Defense Act of 1916 authorized the Marine Corps to increase its end strength from 13,700 to 15,600 with provisions to expand to 18,100. This alowed the Corps to perform its primary mission of providing brigade-size advanced base forces and base security detachments for the U.S. Navy as well as a force to deploy and fight with the Army if the opportunity presented itself, as it had at Veracruz.3 Before this legislation was passed, the Commandant of the Marine Corps, Major General George Barnett, asked to meet with Secretary of War Newton D. Baker. Accompanied by his boss, Secretary of the Navy Josephus Daniels, and his able assistant Colonel John A. Lejeune, Major General Barnett met with Baker and the Army chief of staff and discussed the role of the Marines in the event of war.4

In this meeting, the Commandant “cajoled” the Army’s leaders into accepting two regiments with the intent of forming a Marine brigade.5 The Army agreed but did not issue a blank check. At the same meeting, Barnett “agreed to several administrative changes so as to outfit and organize the token leatherneck force along army lines.”6 In turn, Secretary Baker assured Barnett that the Army would provide the Marines with the equipment needed to bring the regiments up to the Army’s tables of equipment so the Marine regiments would be “organized like the Army.”7 This raises the question of why Major General Barnett and Colonel Lejeune agreed to these conditions. Were they forced into the agreement? Was the Army spitefully demanding the Marines look like soldiers? Were the Marines in such dire need of equipment that they felt compelled to agree?

Before World War I, the Corps, like the Army, organized itself into regiments. But unlike the Army, the Corps did not have a fixed structure below the regiment level. Its naval mission required Marines to deploy on various combinations of naval vessels, so the Corps used a flexible organization where the number of battalions and companies per regiment could be adjusted to match changing requirements. This ability to task organize was a strength when operating with the Navy. The problem was that when the Marines moved inland, away from the ships providing logistical support, they would then have to draw that support from the Army.8

As the clouds of war blew from Europe to America, Secretary Baker and the Army staff were also planning their own wartime requirements. They understood the Army would be expanding at an unprecedented rate, turning out combat divisions in a matter of weeks and months. To do this required a standard and uniform template. Every type of unit—infantry, artillery, engineer, or any other essential support unit—would all have to be the same in organization and equipment. Nonstandard units with unique requirements would be too difficult to manage.9

The AEF eventually exceeded 2 million troops.10 To this force, the Marines contributed 24,555 servicemembers organized into four infantry regiments and accompanying casualty replacement units.11 Four infantry regiments were hardly enough to cause the Army to adjust its planning system, but it was enough to complicate its sustainment system with nonstandard equipment and units with fluctuating numbers of fighters.

Anticipating the need for more than 1 million troops, the Army foresaw the need to quickly form infantry divisions at locations all over France. They explained to the Marine leaders that the only way they could effectively do this would be by imposing absolute uniformity in organization and structure. Secretary Baker expressed concern that the Marine Corps, with its flexible organization and supply system tethered to the Navy, would be difficult to integrate into this rapidly expanding Army system.12

We can assume that General Barnett and Colonel Lejeune recognized and accepted this logic. They must have accepted the fact that if they were to achieve their goal of fighting in the coming war alongside the Army they would have to adapt. The meeting ended with Barnett and Lejeune assuring Secretary Baker that any Marine units going to Europe would fit smoothly into the machinery of the growing Army.13

The Commandant organized the two Marine regiments earmarked for Europe to mirror the Army’s, with equal numbers of Marines organized in equal numbers of battalions, companies, and platoons. They would use the same equipment as the Army and, on deployment, would shift their system of supply from the Navy to the Army. Wearing the Army’s olive drab uniforms seemed a small price to pay to ensure Marines a place in the line of battle.

The United States declared war against Germany on 6 April 1917, eight months after the Army agreed to Marines fighting next to soldiers and the Commandant decided those Marines would mirror the Army in organization and equipment. On 10 May 1917, Secretary Baker appointed General Pershing commander of the AEF, and on 29 May the Marines received the order to form the 5th Regiment. The Marines’ prior planning to mirror the Army’s table of organization and table of equipment resulted in the new regiment being manned, equipped, and ready to deploy in five weeks.14 The Corps realized its plan to fight in Europe beside the Army.

The charge that the Army, and particularly General Pershing, attempted to destroy the Marines’ unique character by forcing them to change their table of organization to mirror the Army’s, and to use Army equipment, to include the wearing of Army uniforms, simply does not stand up to the facts. The decision to change the Marine Corps’ tables of organization and equipment to mirror the Army’s was made by the Commandant, not by General Pershing, and the decision was made before the United States entered the war and well before Pershing took command of the AEF. Further, the Marines were not shoehorned into the AEF against the Army’s will. The secretary of war and Army chief of staff accepted the Marines once assured that Corps regiments would administratively fit into the Army’s organizational structure. The Commandant made the decision to mirror the Army’s organization and use its equipment months before the United States ever entered the war or Pershing took command of the AEF.

Perhaps more importantly, these decisions reflect the prescience and judgment of the Marine Corps’ leaders, General Barnett and Colonel Lejeune. They recognized that the future of the Corps lay in proving its ability to fight in major land battles beside the Army, not insisting on retaining organizations poorly structured to the coming struggle or insisting on unique uniforms and equipment. The Corps’ legend and lore should reflect this institutional flexibility, adaptability, and willingness to do what was required to ensure a meaningful position in the nation’s defense, not a grudging acceptance of dictates from the Army.

Rear Area Duties

When Marines began arriving in France, many units were quickly scattered about the country attached to the Services of Supply (SOS), primarily as guards and labor parties. While rear area duties were distasteful to Marines, the decision to use them in this role came from hard military logic. In virtually every conflict since the SpanishAmerican War, the U.S. military has faced the difficult decision of determining the mix of the first troops to deploy. When making an opposed landing on a hostile shore, it is logical that combat units arrive first. But when the landing is administrative, the decision is harder to make. Modern armies are dependent on vast amounts of logistical support. If service support troops are not available to perform essential support functions, combat units must do them themselves.

When the first contingent of Americans arrived in France, it consisted primarily of the Army’s 1st Division and the Marines’ 5th Regiment. The support troops necessary to unload the ships, build and run the billeting and training camps, and establish essential supply depots were in very short supply.15 As the Americans began pouring in, the requirements to support them grew exponentially. It would be months before the SOS would have all the people needed to perform its mission. Even though helping perform these duties did not sit well with Marines, the reason for using them in that capacity is understandable.

General Pershing intended to commit his divisions to combat as a fully trained army, not individually as fillers for the depleted French and British divisions. To do this would take time—up to a year—as his divisions formed and trained in France. But he realized that a crisis might force him to commit whatever forces he had. In the first months of America’s growing presence in the war, the 1st Division was Pershing’s only fully manned, equipped, and trained division. If forced to commit American troops to combat before he fully formed his army, the unit to deploy would be the 1st Division, the only one fully ready for combat.16

While 5th Regiment was also fully manned, equipped, and trained, it lacked the ancillary support needed to sustain it in combat. Artillery, communications, engineers, transportation, and all logistical support had to come from the Army. Until another division could be formed using the 5th and 6th Regiments as one of its brigades, the 5th Regiment was just an “extra” regiment and not integral to the 1st Division as trying to attach it would only overtax the division’s resources, slowing its own preparations for battle. With this logic, elements of 5th and then 6th Regiments were used to support the SOS until more support troops could arrive. Only then would the two regiments combine to form a Marine brigade.17

While the process of replacing Marines with support troops took longer than the Marines would have liked, General Pershing proved true to his word and on 23 October 1917, the 4th Brigade raised its colors, becoming one of the two brigades of the 2d Division along with the Army’s 3d Infantry Brigade.18 Then on 16 January 1918, with Pershing’s approval, the 4th Brigade was officially redesignated the 4th Brigade of Marines, a distinctly all-Marine unit.19

But even after the formation of the brigade, Marines continued to serve with the SOS in a variety of functions all over France as casualty replacements. The Marine Corps sent 14,500 officers and enlisted as casualty replacements, organizing them into 18 separate units.20 Most of these troops spent some period of time performing rear-area duties. While this may give the appearance that Marines were being spitefully singled out for noncombat duties, a closer examination suggests otherwise.

In July 1917, the AEF published The General Organization Project, specifying how it would replace its casualties and sustain its combat divisions and corps. Based on British and French practices, this document stated that to maintain two divisions in combat, each corps would need two additional divisions in reserve, allowing them to rotate in and out of the line. In addition to the support provided by the SOS, these four divisions needed another two divisions to provide administrative support in the form of training units, school units, base support units, replacement processing units, and positions at Corps- and Army-level units.21 This was the tax that had to be paid to sustain the combat units; the Marines were not exempt.

BGen Charles A. Doyen, commanding general, 4th Brigade, France, 1918. Official U.S. Marine Corps photo, Historical Reference Branch, Marine Corps History Division

The administrative requirements to sustain large military forces are vast. The debate about the ratio of “tooth to tail” is always contentious, but to brush away the requirements to support forces in the field is to ignore the realities of modern war. Maintaining a constant level of combat troops in the field demands a price. The Army based its support system on those of its allies.22 The Army’s expectation that the Marine Corps would support these requirements was reasonable, and the Marine Corps met those obligations to the best of its ability. As the AEF grew in size and the demand for manpower swelled, it was not uncommon for Army units to send large detachments to perform similar support functions. To suggest that Pershing singled out Marines for rear-area support functions simply ignores the conditions in France necessary to support the combat divisions.

Charles Doyen's Relief

In April 1918, while the AEF was training in the trenches of the Verdun sector, an incident occurred that Marines have ever since considered to be one of the most distasteful affronts inflicted on the Corps: General Pershing’s relief of the 4th Brigade’s commander, Brigadier General Charles A. Doyen. When the 5th Regiment formed, Doyen, then a colonel, became its first commander. A seasoned campaigner, he was by all accounts everything a military officer could aspire to be: competent, committed, conscientious, devoted to his troops, and loyal to his superiors. When 6th Regiment arrived in France and General Pershing formed a Marine brigade, Doyen assumed command with the rank of brigadier general.

For 10 months, Brigadier General Doyen provided a skilled and guiding hand to the Marines in France. He formed the brigade and trained it under intense pressure and difficult conditions. The bond between the commander and his Marines was strong, and their trust in him was implicit. Then, on 29 April 1918, while Doyen and his troops were in the trenches at Verdun training under combat conditions, General Pershing removed him from command, replacing him with an Army general.23

His relief was part of a larger effort to ensure that all general officers were up to the imminent physical challenges of combat. General Pershing observed that most of the general officers in France were old campaigners—old not only in experience but also in age. Their physical stamina and endurance to perform effectively in the harsh conditions of battle became a concern. An order was issued requiring every general in the AEF to undergo a comprehensive physical examination. Standards were established and those failing to meet them would be returned to the United States.24

Doyen and four other Army generals failed to meet the established requirements and they were all returned to the United States.25 Command of the Marine brigade passed to Army Brigadier General James G. Harbord, Pershing’s chief of staff. Harbord quickly earned the trust, confidence, and loyalty of the Marines. In less than two months, he would lead them to victory in the Battles of Belleau Wood and Soissons. Doyen would die before the end of the year on 6 October 1918 at age 59, six weeks before the end of the war. Replacing Doyen with an Army general was one of the more unpalatable events of the war for the Marine Corps. Even though Doyen failed to meet the established standards of an objective physical examination, his relief fueled rumors that General Pershing disliked Marines and had only accepted them under pressure from Washington.26

Marines in the AEF

Some Marines took Doyen’s relief as a personal affront, never forgiving Pershing or the Army at large for this seeming slight against the Corps. While this viewpoint appeals to those interested in fostering legends of inter-Service conflict, the actual record of Pershing’s treatment of Marines indicates that if he had a prejudice, it was one in favor of their professional abilities. When he appointed Harbord to command the Marine brigade, there were no other Marine generals in France. Pershing had no other option.

When Harbord assumed command of the AEF’s Services of Supply, the newly arrived Lejeune received command of the brigade and then three days later advanced to command its parent unit, the 2d Division.27 This was not preordained and Pershing did not have to do it.

In World War I, the Army consisted of three types of divisions: Regular Army divisions, National Guard divisions, and National Army divisions, the last being the rough equivalent of a modern Reserve division. Without debating the merits of each type, the Regular Army divisions were generally considered the premier commands. On arrival, Lejeune initially received command of the 64th Infantry Brigade of the Wisconsin National Guard. Had General Pershing disliked Marines or doubted their professional competence, he could easily have left Lejeune in this command. Instead, he transferred him to command the coveted 4th Brigade and then almost immediately advanced him to command the 2d Division of the Regular Army. Along with the 1st and 3d Divisions, it was considered one of the AEF’s premier assault divisions.28 Posting a Marine to command such a unit was hardly the action of a man with an axe to grind against the Marine Corps.

If Pershing harbored animosity against the Marine Corps, he certainly did not seem to express it in the assignment of individual Marines. He carried two Marines with him on his staff when he left for France. During the war, dozens of Marine officers filled positions of authority and responsibility throughout the AEF as commanders and staff officers.29 Only two of four Marine generals served in France and two commanded units in combat: Major General Lejeune, the first Marine to command a division in combat—and an Army division, at that—and Brigadier General Wendell C. Neville, who took command of the 4th Brigade after Lejeune.

When the 5th Brigade arrived in France, its commander, Brigadier General Eli K. Cole, was promoted and briefly commanded the 41st Division during the final weeks of the war. He then commanded the 1st Replacement Depot at Saint-Aignan and finally the American Embarkation Center and Forwarding Camp at Le Mans.30 Brigadier General Smedley D. Butler commanded Camp Pontanezen in Brest, France. This was the AEF’s primary depot for all arriving and departing troops. His job was to oversee the operations of the “largest embarkation camp in the world.”31

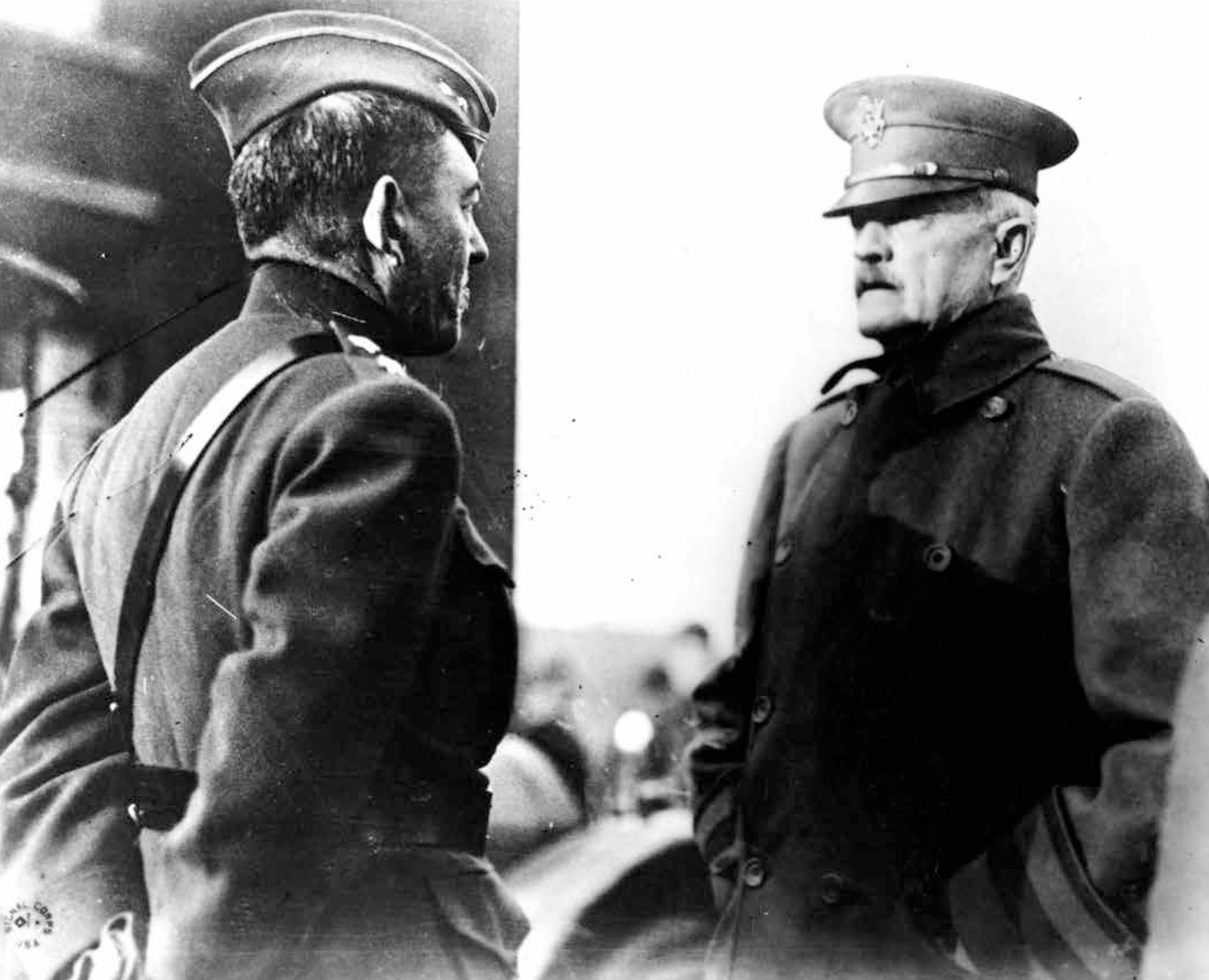

Gen John J. Pershing and Gen John A. Lejeune, France, 1918. Official U.S. Marine Corps photo, Historical Reference Branch, Marine Corps History Division

In May 1918, there were in fact more field-grade officers in the 4th Brigade than it needed. This stood in contrast to the exponentially expanding Army that found itself short of senior officers with combat experience. Most Marine field-grade officers had extensive service and experience. As such, they were highly sought after for both command and staff positions, detaching to serve as battalion, regimental, and brigade commanders of Army infantry, machine gun, and artillery units.32 Throughout the war, Marine officers served almost continuously on the staffs of not only the 2d Division but also the 1st, 3d, 4th, 6th, 26th, 32d, 35th, 90th, and 92d Divisions.33

While it is common to focus on the use of Marines in what are generally considered unglamorous rear-echelon jobs, it should be remembered these jobs were essential, and the assignments were not a reflection on the Marines’ professional abilities. Marines were generally prized for their abilities. Had General Pershing disliked Marines or held reservations about their abilities as soldiers, it seems unlikely he would have condoned their assignment to so many positions of authority and responsibility. The relief of Brigadier General Doyen was unquestionably an unsatisfactory event, but war is a hard business. When people’s lives hang in the balance and victory is at stake, commanders must make hard decisions. That is something all Marines understand.

A Place in the Line of Battle

The 4th Brigade spent almost two months in the trenches near Verdun, but its first major test came at the Battle of Belleau Wood. The 4th Brigade’s performance at Belleau Wood does not need to be recounted here, however. The glory and honors it garnered and the publicity it received propelled it and the Marine Corps into the forefront of the nation’s consciousness.

Marine Corps lore often portrays Belleau Wood as an all-Marine battle in which the 4th Brigade halted the German advance and saved Paris. It is often overlooked that while the Marines had an excess of field-grade officers, it was in short supply of junior company-grade officers; a shortage filled by the Army. Many of the small unit actions in this and the other battles of the war were led by Army officers serving in the brigade. In his memoirs, General Pershing clearly acknowledges the performance of the 4th Brigade at Belleau Wood, but his account, perhaps to the annoyance of Marines, places the battle in the larger context, one fought by the 2d Division, next to the 3d Division’s simultaneous combat at Château-Thierry.34

Without question, the 4th Brigade deserves every honor it earned at Belleau Wood. The courage and tenacity it displayed during that battle have seldom been matched. But it is easy to forget that the 4th Brigade never fought as an independent unit. It always fought as an integral part of the 2d Division, which included the 3d Infantry Brigade, 2d Field Artillery Brigade, and its other organic units providing engineer, signals, supply, and sanitation support.35

The 2d Division was a Regular Army division, one of the first three formed in France, and considered one of the Army’s top three divisions. It fought prominently in every campaign of the war; the Aisne defensive, the Aisne-Marne offensive, the Saint-Mihiel offensive, and the Champagne offensive, where it was attached to bolster the French sector, assaulting and capturing Blanc Mont before returning to the U.S. 1st Army for the final Meuse-Argonne offensive. With the Armistice and the occupation of bridgeheads on the east bank of the Rhine, General Pershing again turned to the 2d Division to serve in the Army of Occupation. If excessive publicity caused Pershing to want to keep the 4th Brigade from the front lines after its performance at Belleau Wood, leaving it in the 2d Infantry Division was not the way to do it.

The account of Chicago Tribune reporter Floyd Gibbons reporting on the actions of the Marines at Belleau Wood is almost as famous as the battle itself and does not need to be recounted here anymore than does the battle. There is no doubt that the Marines’ unexpected publicity temporarily ruffled some feathers. But there is no evidence that due to this publicity Pershing ever considered reassigning the 4th Brigade to another division to prevent it from fighting in the coming battles, even if he did bear a professional grudge against the Marine Corps as an institution.

In the spring of 1918, the AEF still had not reached the level of proficiency that Pershing felt was essential before committing it to battle. But when the Germans launched their spring offensives in a final attempt to win the war, he came under intense political pressure to commit his forces. After Pershing finally agreed, the 1st, 2d, and 3d Divisions joined the defensive battles and helped halt the Germans. With the Aisne-Marne offensive immediately following and lasting into July, he was hard-pressed to ensure the American Army would be prepared to undertake the Saint-Mihiel offensive in early September. This first all-American offensive was quickly followed by an even larger Allied offensive, the Meuse-Argonne. With the intense pressure and focus required to manage these events, it seems unlikely that the commander of the AEF would have time to obsess about the publicity of a single brigade, even if it was a Marine brigade. There is no evidence that Pershing spitefully tried to prevent this single brigade, with its record of excellent performance, from fighting when it would require him to break apart one of his best-trained and combat-tested divisions. By all accounts, he had far more important things on his mind. If animosity did exist between General Pershing and the Marines, it was most likely not with the 4th Brigade, but rather with Headquarters Marine Corps in Washington, DC.

The Struggle for a Division

The Commandant, Major General Barnett, made no secret that he wanted to field a Marine Corps division. In turn, Pershing unquestionably opposed the formation of such a division. But the reason for his objection was more than professional pique or interService rivalry.

As with the other Services, the Marine Corps experienced numerous administrative challenges in expanding to meet the needs of World War I. Even though it expanded from 15,000 to 75,000, it was still only able to send four infantry regiments to France, with casualty replacement units sufficient only for a single brigade. It was never able to deploy a single battery of artillery or any of the other combat support and combat service support units essential for a functional division. Had a Marine division been formed in 1918, other than the infantry regiments, the Army would have had to provide all of the units required to make it a functional unit. At this time, the Marine Corps simply did not have the organizational and administrative capacity to field a fully capable division. Had the war lasted another year, the Corps might have been able to provide those capabilities, but it was never feasible during the war. By then, there was the even more pressing issue of replacing casualties.

Even though they analyzed the British and French experience of the previous three years, Americans never believed they would also suffer the same horrendous casualties on the western front.36 Despite the best efforts of American planners, by late summer 1918, the entire AEF experienced a crisis in manpower. The losses hit the Marines particularly hard, and during the relatively short period of six months of combat, they were hard-pressed to maintain their single infantry brigade.

When Major General Barnett met with Secretary of War Baker in 1916, he understood and quickly addressed the Army’s concern about uniformity in organization and equipment. His adjustments ensured all Marine units joining the AEF would fit in seamlessly. But the Corps’ ability to provide the casualty replacements needed to ensure its brigade could be sustained in combat was never fully addressed. The Army determined that even with the Marine Corps’ five-fold expansion, it simply lacked the depth and organizational ability to sustain large combat formations given the expected casualties. Once committed to combat, if the Marines could not provide a steady flow of replacements, the all-Marine brigade would cease to exist through attrition, with soldiers rather than Marines filling its depleting ranks. If the Marines could not ensure a reliable supply of troops, the logic of committing them to combat as a uniquely Marine Corps unit had to be questioned. It was the view of the War Department, the AEF, and Pershing that “while the Marines are splendid troops, their use as a separate division is unadvisable.”37 This view never changed; it was simply a matter of battlefield logic.

Manpower administration is a subject that attracts scant attention among military scholars and even less with students of military history. Those charged with its management gain little glory and, even when successful, tend to be ignored and forgotten. But administrative organization and depth, sufficient to meet the growing and unexpected demands of war, is essential. Without it, well-trained and competently led units imbued with esprit de corps cannot be sustained in the face of the inevitable attrition of battle.

From the Washington corridors of Headquarters Marine Corps to Major General Lejeune’s field headquarters in France, ensuring the availability of fresh Marines was an issue of concern for the Corps’ top leaders. Their efforts to supply the personnel needed to keep their single brigade at combat strength were herculean. They succeeded—but with little room to spare.

To understand why requires a general understanding of the AEF casualty replacement plan. To maintain its manpower, the AEF estimated that 2 percent of its strength would need to be shipped as replacements on a monthly basis. They later increased this estimate to 3 percent. The composition of replacements was 60 percent infantry and 40 percent for all other arms, including the services of supply.38 As previously discussed, the Marine Corps only provided infantry units. This relieved them from providing for the other arms and support units.

Soon after the 5th Regiment arrived in France in June 1917, General Pershing asked the Commandant for three replacement battalions to start building the Marines’ replacement pool. This number quickly increased to five battalions.39 The first unit raised to meet this need was the 5th Regiment Base Detachment.40 With 1,200 men organized into one machine gun and four rifle companies, these were the only Marine Corps replacements in France until December 1917.41 In December, the War Department notified Headquarters Marine Corps that it needed to send three more battalions of replacements to conform to the current plan of having replacements equal to 50 percent of the combat forces. Then in January 1918, the AEF increased the requirement from three battalions to five to provide cadres for advanced training units.42

This set in motion a process that sent an additional battalion from Quantico nearly every month for the rest of the war.43 These units deployed to France based on monthly requests from the AEF as well as Headquarters Marine Corps’ own determination for replacements. A total of 204 officers and 14,358 enlisted eventually deployed to France as replacements. Despite these numbers, the 4th Brigade still relied on the Army for personnel. In addition to the 65 officers and 375 enlisted provided by the Navy as chaplains, doctors, corpsmen, dentists, and dental technicians, the Army ultimately provided six Regular Army officers and two men, three National Army officers, 109 Infantry Reserve Corps officers, 29 officers and 27 enlisted men from the Medical and Dental Corps, 7 chaplains, 8 Veterinary Corps officers, and 7 officers and 80 enlisted men from the Signal Corps.44

Once engaged in battle, these numbers proved sufficient to keep the brigade at its table of organization strength of 8,469. But with 12,000 casualties and a 150-percent replacement rate, along with the administrative toll to support the larger AEF, it was barely sufficient. If the 5th Brigade had been committed to combat, there would be more casualties, generating an even greater demand for replacements.

Considering the Corps’ difficulty in maintain the strength of a single brigade in combat, Pershing’s concerns about the Marines’ ability to sustain themselves seems justified. It also helps explain his resistance to combining the 4th and 5th Brigades to form a Marine division.

Almost as soon as the Marines arrived in France, the Commandant, Major General Barnett, began peppering Pershing with inquiries about how he was employing them, when they would form a brigade, and the possibilities of forming a division with the arrival of a second brigade.45 While Pershing likely understood Barnett’s concern for his men, being constantly second-guessed by Washington and pressured to accommodate fewer than 30,000 men out of more than 2 million must have worn thin rather quickly.

When Major General Lejeune arrived in France, he brought a letter from the Commandant to General Pershing. It proposed that the Marines provide one or more divisions to the AEF. As previously noted, this would require breaking up the 2d Division just as the first all-American offensive was about to begin. Pershing had also expressed his reservations about forming a Marine division, based on the perceived inability of the Marine Corps to replace its ever-growing list of casualties. In a letter to Secretary of War Newton Baker, Pershing commented on the proposal with an emphatic “No.” He later stated: “Referring to my conversation with the Secretary . . . on this subject, I am still of the opinion that the formation of such a unit [a Marine Division] is not desirable from a military standpoint.”46

The obvious retort to his objections to forming a Marine division because of concerns over manpower is that if Marines had not been diverted to innumerable duties with the SOS, they would have been available as casualty replacements, the sole reason they had been sent to France. But this argument does not stand up under scrutiny.

The 4th Brigade entered the Aisne defensive at its table of organization strength of 8,459. The casualties suffered during the June and July battles triggered a call for replacements, which Headquarters met by sending roughly two battalions a month for the rest of the war.47 From the start, this effort was barely sufficient. A large number of replacements were already in France, but the need to augment the administrative establishment of the AEF was significant. When these numbers were added to the casualties incurred in battle, it meant the Marines suddenly needed to provide approximately 5,000 troops to maintain the 4th Brigade’s combat strength.48 This triggered a crisis never fully resolved during the war.

During June 1918, the 1st, 2d, 3d, and 4th Replacement Battalions provided 2,471 fighters, augmented by an additional 550 casualties who were returned to duty. This total of 3,021 replacements against a requirement of 5,000, gave the 4th Brigade only 6,137 troops, roughly 2,000 short of its required strength, with no more replacements available in France. The next large group of Marines in France had been assigned as AEF training cadres and could not be released without first having their own replacements.49

By 17 July, the eve of the Aisne-Marne offensive, the brigade was up to 7,037 troops. But by 1 August, when it withdrew from Soissons, its ranks had been depleted to 4,959, more than 2,500 short with no replacements available other than returning casualties. The situation was so dire that the AEF staff notified Major General Lejeune, the 2d Division commander, that if Marine replacements could not immediately be obtained, Army replacements would fill the gap.50

This was the situation Pershing had feared and the Marine Corps had sought to avoid. Its impact was fully understood by both Lejeune and Barnett. The Commandant, who had struggled so hard to ensure Marines left for France with the first detachment of American troops and who had contentiously pressed Pershing to assign the Marine brigade to a combat division despite the concerns of Pershing and the AEF staff, now faced the prospect of seeing the brigade’s Marine Corps identity erased through battlefield attrition unless he could quickly feed more Marines to the front lines. The seriousness of the situation and the Marine Corps’ inability to quickly and definitively resolve the problem are reflected in a letter from the Commandant to Lejeune dated 14 August 1918:

Have just organized and sent to France the 3rd, 4th, 5th, and 6th, Separate Battalions with a total enlisted strength of 3800. In addition the First Separate Machine Gun Battalion, with a total enlisted strength of 500 has been organized and will leave before the end of the month. This makes a total of about 18,000 men that we have dispatched to France for the maintenance of the one Brigade. Today a cablegram received from General Pershing making requisition for September replacements as follows: Infantry 3,500, Machine Gunners 1,000. If this order stands, it means that we will have by the end of September 22,500 men in France for the Fourth Brigade and with no way of estimating what is to follow. You can easily imagine the predicament this leaves us in, especially as regards furnishing the new brigade with its replacements.

To further complicate the matter, the President has just issued an order stopping all enlistments in the Navy and Marine Corps, and recruiting will probably be stopped for a month or more. We have about 12,000 men at Parris Island under training and awaiting completion of enlistment, and we will be alright for the next two months, but after that, there will be a period (the length of which will depend upon the length of time during which recruiting is stopped) when recruit depots will not turn out any men and the question of replacements is going to be a very serious one. Of course over here we cannot form any idea of what the situation is in France, but it seems like there must be a large number of Marines scattered around in France, not available at the present time for replacements. If you get the chance, therefore, I wish you would try to take up the question with General Pershing or someone on the General Staff, and see if you cannot get all of the scattered detachments ordered into our replacement organization.51

The battalions Major General Barnett referenced in this letter would not be in France until 2 September, hardly enough time to process and integrate the new troops into the brigade before the launching of the Saint-Mihiel offensive on 12 September.52 Major General Lejeune found himself in a tough position. As the commanding general of 2d Division, his primary responsibility was to ensure his division was ready when the offensive began, even if it meant filling the 4th Brigade with soldiers. But as the senior Marine Corps officer in France, and the one who guided the effort to ensure a Marine brigade would fight with the Army, he certainly felt compelled to explore every avenue to ensure Marines filled the brigade’s ranks.

On the eve of the first all-American operation, Lejeune certainly realized that Pershing had greater issues to deal with than the casualty replacements of a single brigade. He likely felt it prudent not to raise this issue with the commanding general. Instead, he contacted his friend from days as a student at the Army War College, the former 4th Brigade commander, Major General Harbord, now commanding the SOS that had absorbed so many Marines. Lejeune requested that Harbord send all Marines with the SOS who were fit for combat duty to the 4th Brigade. Harbord came to the aid of his friend and old brigade, immediately releasing Marines with the SOS from all over France. By 31 August, the brigade’s strength was up to 6,836, still far from full strength. Lejeune was compelled to notify 1st Army Headquarters that he needed 1,700 more replacements.53

The crisis soon resolved itself, at least in G-1s ledgers of the 2d Division, I Corps, and First Army. Between 5 and 11 September, 2,000 Marine Corps replacements were assigned to the brigade, bolstering its rolls to combat strength. But, in fact, the 3d, 4th, and 5th Separate Battalions did not leave the rear areas to join the brigade until 8 September. Confusion and delays in transportation prevented their reaching the brigade until the night of 11–12 September, the eve of the Saint-Mihiel offensive. With the brigade already in the trenches poised to attack, getting the replacements to their assigned companies and platoons proved problematic. How many servicemembers actually reached their units before the assault began will never be known, but the brigade’s muster rolls list approximately 30 percent of the replacements as joining their units on 16 September, the day the offensive ended.54

Fortunately, the Saint-Mihiel offensive exacted a light toll with only 132 killed and 574 wounded. The Champagne offensive would not be as gentle. The brigade strength on 1 October 1918 stood at 7,560. In the near-continuous fighting during 2–10 October, 494 troops were killed and 1,864 wounded. By 12 October, Lejeune needed more than 1,000 replacements for the 4th Brigade and a total of 5,000 for the entire 2d Division.55

On the night of 30–31 October, the 4th Brigade reached its frontline position to begin its final attack as part of the Meuse-Argonne offensive. Its assault through the Ardennes was brutal. When the Marines reached the banks of the Meuse on 11 November, their ranks were depleted. On 14 November, the 4th Brigade requested an additional 2,800 infantry, 200 machine gunners, and 40 second lieutenants. The only available infantry replacements in France were two battalions that had landed on 3 November. They would not arrive at the American training base at Saint-Aignan until 14 November. There were no available machine gunner replacements. The commanding general of Base Section 5, which controlled Camp Pontanezen, was ordered to strip 200 fighters from the 5th Brigade Machine Gun Battalion and forward them to the 4th Brigade.56

When the replacement battalions reached SaintAignan on 14 November, they immediately passed through, leaving the following day with virtually no preparation or training. They arrived at the Dun-surMeuse railhead the evening of 16 November. They immediately began marching to join the brigade at its last position east of the Meuse only to find it was no longer there. As one of the divisions to participate in the Army of Occupation, the 2d Division was already marching toward the Rhine. The replacements followed in trace, picking up the pace and joining the brigade the evening of 20 November in the town of Arlon, Belgium.57

The last Marine replacement unit to leave the United States, the 9th Separate Battalion, arrived in France on 9 November.58 With the Armistice declared two days later, the replacement crisis was over, but the situation had been critical. By the time the Armistice was announced, every replacement unit, even if not every Marine in those units, had been forwarded to the 4th Brigade, and still, the 5th Brigade had to provide 200 troops.59

If there had been no Armistice on 11 November, the brigade’s casualties would almost certainly have continued to rise. Based on the bleak assessment from Headquarters, the only viable option for Marine replacements would have been the further stripping of people from the 5th Brigade. This assumes the AEF would even have agreed to use the 5th Brigade as a replacement pool, which is questionable. This would have given credence to Pershing’s objections to fielding a Marine division, or even employing a second Marine brigade as part of another division, based on his concerns about the Marine Corps’ ability to provide sufficient replacements. From the perspective of the most efficient use of available manpower to meet immediate combat requirements, it seems likely that 4th Brigade replacements would have increasingly been soldiers, not Marines. If the war had continued with the brigade sustaining casualties at the same rate, another major offensive would have likely meant the 4th Brigade would have been composed primarily of soldiers. While distasteful to acknowledge, in retrospect, Pershing’s objections to fielding a second Marine brigade or a division seem justified.

Conclusion

While General Pershing can hardly be called a friend of the Marine Corps, an honest appraisal cannot cast him as a vehement antagonist, as he is often portrayed. In the instances discussed, either decisions had been made before he assumed command of the AEF, or, when he did make decisions adversely affecting the Marines under his command, they were based on the requirements as he saw them at the time. There is no evidence, other than conjecture, that Pershing based his decisions on personal animosity toward the Corps.

The decision to assign Marines to the AEF was made long before Pershing assumed command. While the Commandant intended that the two attached regiments form a brigade, once the Marines detached from the Department of the Navy and joined the Department of the Army, they became a part of the AEF. As its commander, General Pershing was free to use them as he deemed fit and was under no obligation to use them according to the Commandant’s desires. But he did, keeping his word to form the brigade and then assign it as an organic brigade of the 2d Division. He approved its redesignation from the 4th Infantry Brigade to the 4th Brigade of Marines, and raised no objections when its troops were authorized to wear the Eagle, Globe, and Anchor on their Army uniforms. Pershing could have interfered with these actions, but he did not.

His opinion of the Marines is best illustrated in how he used them, not in what he might have thought about them. He assigned the 4th Brigade to the 2d Division, a Regular Army division. As such, it participated in every major operation in which the AEF participated. Once battle was joined, the only time the brigade and its parent division were not fighting was when the AEF was not fighting.

His use of Marine field-grade officers throughout the AEF further reflects his regard for their abilities. These officers commanded Army battalions, regiments, and brigades. They served on the staffs of units at every level. Even in rear-area duties, Marines were in positions of importance with training units and large personnel centers responsible for ensuring the smooth flow of personnel to and from the front.

As volunteers who joined to fight, those standing guard in supply depots were not doing what they had hoped. But even larger numbers of Marines who volunteered to fight the Germans spent the war on the Mexican border or Caribbean islands, waiting for combat that never came. All members of the military execute their orders, regardless of where those orders send them.

He clearly opposed the formation of a Marine division and opposed the commitment of a second brigade of Marines to battle, but those objections were based on two irrefutable facts. In 1917–18, the Marine Corps lacked the ability to field a fully capable infantry division, and the ability of the Corps to quickly and reliably replace the large number of expected casualties was, at best, questionable. An honest examination of the record shows that both of these concerns remained valid for the duration of the war.

For Marines to dwell on perceived slights during World War I seems fruitless. Pershing’s placement of the Marine brigade in the 2d Division gave the Corps the opportunity to prove, beyond any doubt, that they were more than just a naval landing party. They proved that they could successfully fight next to the best regiments of the Army and against what was considered one of the best armies in the world. This helped secure their future role in America’s defense establishment, and for that, some degree of recognition is due to General Pershing.

If Pershing’s concern about the institutional ability of the Marine Corps to field a fully capable infantry division strikes a nerve or if his concern for the Corps’ ability to ensure it could sustain its units in the face of heavy casualties is painful to admit, the Corps’ leaders at the time saw these criticisms for what they were: legitimate weaknesses that needed to be corrected.

The interwar period is remembered as the time when the Marines’ search for a mission produced the amphibious doctrine that won World War II in the Pacific. But clearly, time was also invested in correcting the institutional shortcomings that were so apparent during World War I. Postwar reductions shrank the Marines back to their prewar strength of 15,000, where they remained for the next two decades. But the administrative lessons of World War I were fully absorbed, and when World War II came, the Marines were prepared to expand rapidly. The ability to produce a fully capable division was no longer an issue. Far from just fielding a single all-infantry brigade, before the war’s end, the Marines fielded six divisions with six supporting air wings, organized into two corps-level commands. Without the willingness to accept the hard-learned lessons of World War I, this may not have been possible. If General Pershing had not assigned the 4th Brigade to the 2d Division, those lessons may never have been learned.

Still, when the casualty lists exceeded all expectations, it created a crisis in manpower that lasted until the war’s end. The Marine Corps sustained its one combat brigade and met its requirement to augment the AEF’s supporting establishment, but only barely.

•1775•

Endnotes

- Maj Ralph Stoney Bates Sr., “Belleau Wood: A Brigade’s Human Dynamics,” Marine Corps Gazette 99, no. 11 (November 2015): 13.

- John J. Pershing, My Experiences in the World War (Blue Ridge Summit, PA: TAB Books, 1989), 321.

- Kenneth W. Condit, Maj John H. Johnstone, and Ella W. Nargele, A Brief History of Headquarters Marine Corps Staff Organization (Washington, DC: Historical Division, Headquarters Marine Corps, 1971), 10.

- Merrill L. Bartlett, Lejeune: A Marine’s Life, 1867–1942 (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 2012), 65.

- 5 Allan R. Millett, Semper Fidelis: The History of the United States Marine Corps (New York: Free Press, 1991), 290.

- Allan R. Millett and Jack Shulimson, eds., Commandants of the Marine Corps (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 2004), 184.

- Millett, Semper Fidelis, 290.

- George B. Clark, The Second Infantry Division in World War I: A History of the American Expeditionary Force Regulars, 1917–1919 (Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 2007), 190.

- Clark, The Second Infantry Division in World War I, 11.

- American Armies and Battlefields in Europe (Washington, DC: Center of Military History, U.S. Army, 1992), 515.

- Maj Edwin N. McClellan, The United States Marine Corps in the World War (Washington, DC: Historical Branch, G-3 Division, Headquarters Marine Corps, 1968), 17.

- Clark, The Second Infantry Division in World War I, 11

- Millett and Shulimson, Commandants of the Marine Corps, 184.

- Tom FitzPatrick, Tidewater Warrior: The World War I Years—General Lemuel C. Shepherd, Jr., USMC Twentieth Commandant (Fairfax, VA: Signature Book Printing, 2010), 121.

- McClellan, The United States Marine Corps in the World War, 30.

- Maj James M. Yingling, A Brief History of the 5th Marines, rev. ed. (Washington, DC: Historical Branch, G-3 Division, Headquarters Marine Corps, 1968), 3.

- Clark, The Second Infantry Division in World War I, 186.

- Maj Edwin N. McClellan, “The Fourth Brigade of Marines in the Training Areas and the Operations in the Verdun Sector,” Marine Corps Gazette 5, no. 1 (March 1920): 81.

- McClellan, “The Fourth Brigade of Marines in the Training Areas and the Operations in the Verdun Sector,” 81.

- Joel D. Thacker, “Replacement Personnel in World War I” (unpublished paper, Historical Section, G-3 Division, Headquarters Marine Corps, Washington, DC, 1942), 17–19.

- United States Army in the World War, 1917–1919, vol. 12, Reports of the Commander in Chief, Staff Sections and Services (Washington, DC: Center of Military History, U.S. Army, 1991), 142.

- United States Army in the World War, 142–44.

- McClellan, “The Fourth Brigade of Marines in the Training Areas and the Operations in the Verdun Sector,” 107.

- George B. Clark, The Fourth Marine Brigade in World War I: Battalion Histories Based on Official Documents (Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 2015), 5–6.

- Clark, The Fourth Marine Brigade in World War I, 5–6.

- Clark, The Fourth Marine Brigade in World War I, 5–6.

- FitzPatrick, Tidewater Warrior, 351

- FitzPatrick, Tidewater Warrior, 351.

- McClellan, The United States Marine Corps in the World War, 38

- McClellan, The United States Marine Corps in the World War, 62.

- McClellan, The United States Marine Corps in the World War, 62.

- McClellan, The United States Marine Corps in the World War, 36–37.

- McClellan, The United States Marine Corps in the World War, 36–37.

- Pershing, My Experiences in the World War, 90

- McClellan, The United States Marine Corps in the World War, 38.

- Clark, The Second Infantry Division in World War I, 12

- George B. Clark, Devil Dogs: Fighting Marines of World War I (Novato, CA: Presidio Press, 1999), 390–91.

- United States Army in the World War, 142–44.

- LtCol Charles A. Fleming, Capt Robin L. Austin, and Capt Charles A. Braley III, Quantico: Crossroads of the Marine Corps (Washington, DC: History and Museums Division, Headquarters Marine Corps, 1978), 32.

- Fleming, Austin, and Braley, Quantico, 26.

- McClellan, The United States Marine Corps in the World War, 34.

- Thacker, “Replacement Personnel in World War I,” 19–24.

- Fleming, Austin, and Braley, Quantico, 32.

- Thacker, “Replacement Personnel in World War I,” 17–19.

- Bartlett, Lejeune, 69

- Clark, Devil Dogs, 390–91.

- Fleming, Austin, and Braley, Quantico, 32

- Thacker, “Replacement Personnel in World War I,” 24.

- Thacker, “Replacement Personnel in World War I,” 24.

- Thacker, “Replacement Personnel in World War I,” 25.

- Thacker, “Replacement Personnel in World War I,” 25–26.

- McClellan, The United States Marine Corps in the World War, 30–34.

- Thacker, “Replacement Personnel in World War I,” 25–26.

- Thacker, “Replacement Personnel in World War I,” 26–27

- Thacker, “Replacement Personnel in World War I,” 26–27

- Thacker, “Replacement Personnel in World War I,” 28.

- Thacker, “Replacement Personnel in World War I,” 28.

- McClellan, The United States Marine Corps in the World War, 30–34.

- Thacker, “Replacement Personnel in World War I,” 28.