PRINTER FRIENDLY PDF

EPUB

AUDIOBOOK

The Marine Corps’ Combined Action Platoons (CAPs) in the Vietnam War became a significant component of the Corps’ counterinsurgency strategy to pacify the rural countryside.2 The Marine Corps’ general strategy, at least in part, was to clear and hold the land in its enclaves and expand the territory held like a spreading inkblot. Once an area had been cleared of Viet Cong by troops from the Marine or Army of the Republic of Vietnam (ARVN) infantry, adequate security forces were needed to stay in the villages to hold and protect them so enemy forces could not easily return.3 The task of protecting the village was the theoretical duty of a Popular Force platoon, if one existed in the cleared village, consisting of approximately 35 Popular Force soldiers. They were the lowest rung of the Vietnamese military structure, poorly trained, paid only half of what the regular ARVN soldiers were paid, and received no benefits. They were either under the age of 20 or older than 30; those between 20 and 30 were not eligible to elect for Popular Force duty.4 An incentive to joining the Popular Forces was that the soldiers could stay in their home villages and work the rice fields or other family business while providing protection.5 Many villages throughout the Marine Corps’ area of responsibility had Popular Force platoons, usually placed around or near military bases or along main supply routes. Unfortunately, the Popular Force soldiers were not up to the job of protecting the villages. In assessing the situation in October 1965, III Marine Amphibious Force (III MAF) found that the Popular Force platoons’ quality of performance and reliability were questionable.6

Each of the three major Marine Corps enclaves— Da Nang, Phu Bai, and Chu Lai—had substantially different populations and levels of Viet Cong saturation and organization. Even in the populations where the enemy had less power, the Popular Forces were not effective in providing security against enemy activities, especially at night. Throughout the life of the Combined Action Program, as it eventually came to be known, Marines were used to train, motivate, and assist Popular Force platoons to hold their villages once cleared of enemy forces.7 As a force multiplier, the program involved embedding, or brigading, a squad of Marines and a U.S. Navy corpsman into a Popular Force platoon in the villages where each was located. The Marines lived in the villages full time with the Popular Force soldiers.

With Marines in the leadership billets, they worked together to defend the villages and to interdict and suppress Viet Cong activity. The Marines worked hard to raise the level of competence, reliability, and fighting spirit of the Popular Forces, a task that would prove challenging during the course of the war. The official Combined Action Program unit table of organization was 14 Marines, a U.S. Navy corpsman, and 34 Vietnamese Popular Force soldiers.8 These numbers were not always met, however.

A further goal was to try to win over conflicted populations by demonstrating through conduct and civic action that the United States was there to help. The Combined Action Program involved aggressive day and night patrolling, holding regular medical clinics, and participating in civic action projects to improve village life, when possible. In 1969, the program’s peak year, platoons conducted 149,000 patrols, day and night. Serving in a CAP was dangerous duty. During the nearly five years of their existence, approximately 500–525 CAP Marines were killed in action. The available documentation of those killed in action lists 488 names, but it is likely that several deaths were left off while the program was still under the administrative control of infantry or other Marine battalions.9 While the enemy kills were not the measure of success for the program, CAPs accounted for more than 4,900 enemy killed in action.10 The Combined Action Program, which rapidly evolved and expanded, started out as an innovative experiment to defend a vulnerable section of the tactical area of responsibility (TAOR) of Phu Bai, one of the Corps’ priority enclaves in the beginning stages of the war. The account of how the CAPs were created is a study in classic Marine Corps ingenuity in the face of limited resources. The following is a detailed history of their creation.

Background and Context

The Marine Corps was the first of the U.S. military branches to land in force in Vietnam. The Corps’ area of responsibility was the I Corps Tactical Zone (ICTZ), known to most as I Corps, one of four military zones in South Vietnam. It comprised the five northernmost provinces of the country. At the northern end of I Corps was the demilitarized zone (at the 17th parallel) that separated the Democratic Republic of Vietnam (DRV), the north, from the Republic of Vietnam (RVN), the south. At I Corps’ southern end was the southern border of the Quang Ngai Province. When the Marines entered Vietnam in spring 1965, they quickly established three enclaves: Da Nang (established 8 March), Phu Bai (established 14 April), and Chu Lai (established 7 May). The Corps’ theory was to establish and secure these enclaves and then to expand control into the surrounding countryside. The strategy was to clear and hold the land against the enemy so that the RVN government could stabilize and gain back the territory that had been lost. Prior to the landing on 8 March, there were only 200 Marines in Vietnam. Following the initial landing at Da Nang, the number increased to 5,075. A third battalion landing team and a fighter squadron came ashore on 10 April, increasing the number of Marines on shore to 6,500. A fourth battalion, landed 14–15 April, brought the total to 8,150 Marines, and an additional 5,000 Marines landed at Chu Lai in early May, increasing the numbers again to 13,150 in all three enclaves. This movement of Marines into the desired positions in Vietnam resulted in an intense scene of activity.11 On 5 May, the III Marine Amphibious Force (III MAF) was formed and assumed command for all Marines in Vietnam.

Geographically, I Corps was a long north-to-south section of the central part of Vietnam. The landward littoral zone at the time contained vast and rich fields of rice, giving way to foothills and then rising, at some points rapidly, to become the Annamese Cordillera (commonly referred to as the Annamite range or mountains), which run north to south for the length of I Corps’ interior. The mountains are covered in large patches of triple-canopy jungle all the way west into Laos.

Map showing where the first three combined action-patrolled villages were located. Courtesy of Vietnam Center and Archive, Texas Tech University, adapted by Marine Corps History Division

From the Phu Bai River at Thuy Phu village, looking out across the vast rice fields. The South China Sea lies directly east about 8.8 km. Courtesy of Cpl Ed Matricardi

Between 80 and 90 percent of the population lived in the littoral zone in small rice-farming villages. Aside from a few larger population centers, such as Hue City and Da Nang, the hamlet was the natural and fundamental community structure for the farmers and their families. Several hamlets were grouped together as a village for governmental administrative purposes. Many hamlets were represented by their own chiefs, and the whole was represented by a village chief.12 The Marines’ three enclaves fell within this littoral zone.

The Phu Bai enclave was established on 14 April when Colonel Edwin B. Wheeler, the commander of Regimental Landing Team 3, sent units of his 2d Battalion, 3d Marines, to secure the airfield and the Army’s 8th Radio Research Unit (RRU) facility, until the 3d Battalion, 4th Marines, could land and take over the Phu Bai defense. The mission was to defend the Phu Bai airfield and the 8th RRU. This unit was an important key to locating enemy units through radio intercept techniques, and General William C. Westmoreland wanted a force to protect it.13

After 3d Battalion, 4th Marines, landed in Da Nang, 512 Marines of the battalion were lifted by helicopter to Phu Bai to relieve the units from 2d Battalion, 3d Marines, and establish the defense of area. By 16 April, the battalion was fully offloaded and positioned to take command of the Phu Bai enclave. Although the 3d Battalion, 4th Marines, were part of the 4th Marine Regiment, they were under the command and control of Colonel Wheeler’s 3d Marine Regiment. Colonel Wheeler had the ultimate responsibility for the defense of both Da Nang Air Base and Phu Bai.

Village boys herding their buffalo along a river trail in Thuy Phu village. Courtesy of Cpl Ed Matricardi

The Marines had originally been allowed an official TAOR of only two squares miles. This was similar to Da Nang, where the Marines were originally confined within the airfield perimeter and a certain limited area to the west of the airfield. From approximately March through July, the Vietnamese took a cautious approach to the expansion of the Marine areas of responsibility. The Marines were ready and anxious to spread out to defend their areas and to expand control of the enclaves, but the ARVN commanders were cautious for two reasons. The Communists had told the population that the Americans were coming in to take over the country. Despite the fact that the top ARVN commanders also wanted the Marines to spread out, they needed to move slowly so as not to encourage belief in the Communist propaganda.14 General Nguyen Chanh Thi, commander of I Corps, expressed another, perhaps more realistic concern. He was afraid that the Marines would not be able to handle the pacification aspects of the mission, especially in the populated areas south of the Da Nang airfield. Implicit was a fear of incidents that would antagonize the population.15 For the Phu Bai area of responsibility, this reluctance meant a serious limitation on the Marines’ ability to adequately secure a portion of the area immediately adjacent to the base that was critical for base defense.

Typical village trail scene in the Phu Bai rice-growing lowlands. Courtesy of Cpl James Ellison

The Vietnamese commanding general of I Corps, Nguyen Chanh Thi (center), was instrumental in the approval of the Combined Action Program and supported the program during its expansion in 1966 to Da Nang and Chu Lai. Courtesy of Historical Reference Branch, Marine Corps History Division

The Zone A Defense Problem

The Phu Bai military facilities, the airfield, and the 8th RRU straddled Vietnam’s Highway 1, which ran through the Phu Bai base area, angled northwest to southeast. Highway 1 was Vietnam’s national highway and it ran the length of the country from north to south, but the term national highway is deceptive; it was a two-lane paved road that sometimes resembled a county road in middle America more than it did a major thoroughfare.

South of Highway 1 was a vast open area of ridges and hills, variously barren or covered with brush, which finally morphed into jungle in the southernmost sector. This area was near the mountains that led to Laos, and it was from here that the greatest enemy threat would likely come. It was nearly uninhabited for several miles to the Ta Trach River, and despite the fact that this area was not in the initial TAOR, it was necessary for the Marines to immediately explore and control to prevent an attack on the military installations at Phu Bai.

The command records show that 3d Battalion, 4th Marines, very soon after landing—despite the initial TAOR limitations—began patrolling several thousand meters south of its perimeter.16 By 7 May, the TAOR was extended to include this southern area, making the TAOR now 38 square miles.17

The 3d Battalion, 4th Marines, in its defense of the Phu Bai perimeter and the 8th RRU, began an aggressive campaign of patrolling and ambushing within its enlarged TAOR. The Marines used four rifle companies, Headquarters and Service Company, and Company C of the 3d Reconnaissance Battalion, along with the support of engineers, tanks, other armor, and artillery, to defend the perimeter and to patrol. They continued this patrolling for months, exploring the entirety of the TAOR, pinpointing the Viet Cong routes of ingress into the TAOR from the jungles, and blocking their activity on the main routes to the rice lowlands.18

The full defense of the Phu Bai military installations from the surrounding areas, however, posed a problem. To the north and east was a semicircle of three villages bounded by the Dai Giang River. From the perimeter of the air base, it was difficult to see up to and into these villages. The apron between the airfield and the villages was at least a kilometer wide and more in some places. The hamlets themselves were densely vegetated; so even at close range, it would be impossible to see any distance into them. The villages provided enough cover that an enemy mortar team or ground assault unit could get close enough to cause substantial damage. This area was known as Zone A. These three villages and their hamlets had a total population of approximately 10,000 people, primarily subsistence rice farmers who had no electricity or running water. They worked in their fields during the day and went to bed by nightfall. The roads were all dirt, and the houses were made of bamboo framing with palm-thatched roofs and outer walls. Villagers cooked food over open fires and ate fish from the river and rice from their fields. In each of these villages was a 30- to 40-man village Popular Force protection platoon tasked with protecting the village from the Viet Cong. In reality, however, they were no match for the enemy forces. They were poorly trained, and information showed they rarely patrolled to protect the village. Village officials hid at night.19 It was also known at this time that the Viet Cong exercised domination over these villages.20 They taxed the villagers and spread propaganda.21

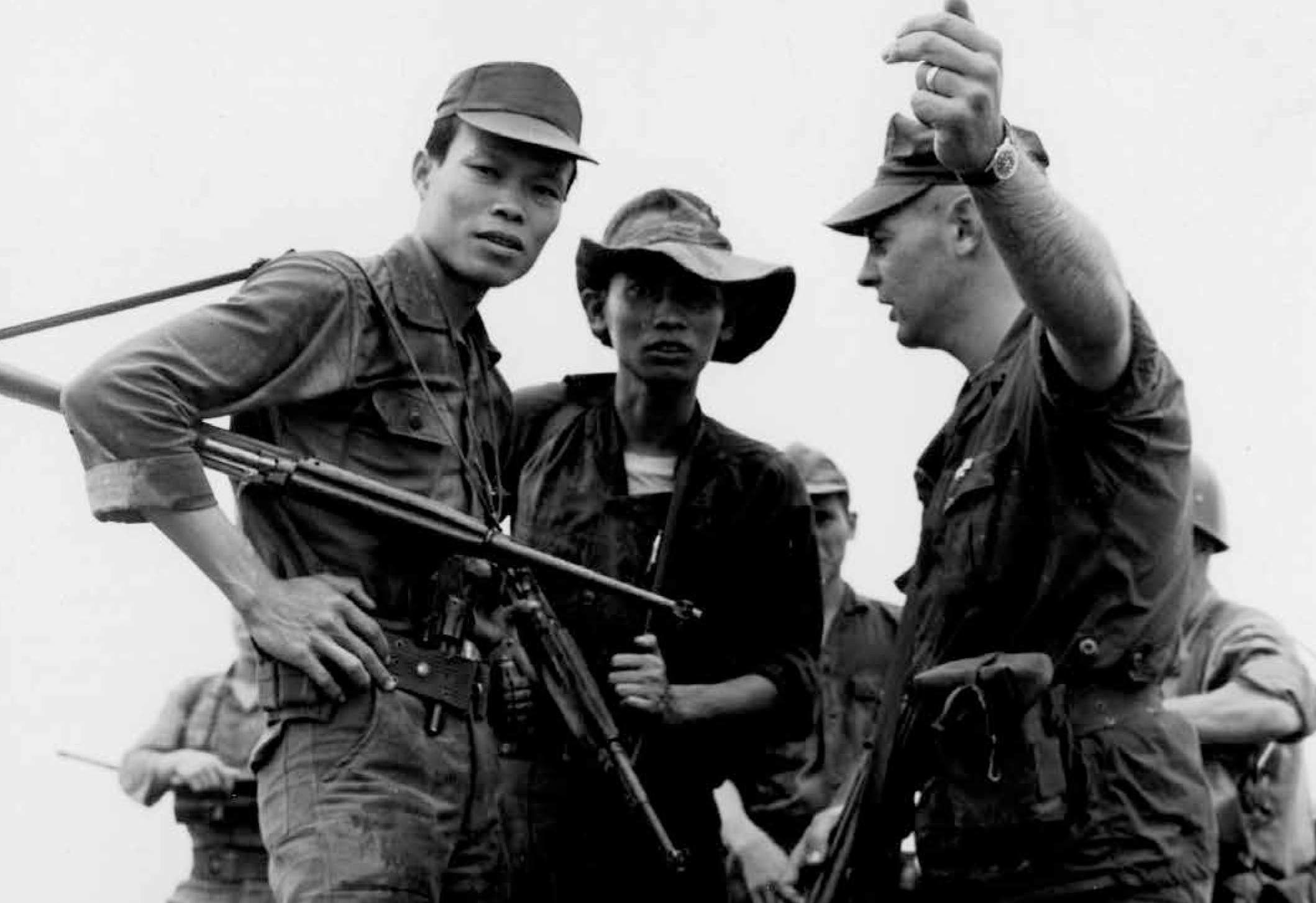

LCpl Thomas E. Reilly (right) points out information to his squad leader, Sgt David W. Sommers. This combined patrol is from Joint Action Company 2 at Thuy Tan village. Photo by SSgt C. Duris, courtesy of Historical Reference Branch, Marine Corps History Division

A village fisherman pushing his boat out to the fishing grounds near Thuy Phu village. Courtesy of Cpl Ed Matricardi

In the 21 April 1965 negotiations with General Nguyen Van Chuan, commanding general of the 1st ARVN division, Phu Bai TAOR parameters were agreed. Zone A would remain in the ARVN’s control.22 While the Marines quickly established control of their territory and maintained a commanding presence in the area, Zone A continued to bother Lieutenant Colonel William W. Taylor, the commanding officer of 3d Battalion, 4th Marines. Taylor made a formal request to Colonel Wheeler’s 3d Marines command that the 3d Battalion, 4th Marines’ TAOR be extended to include Zone A and that the Popular Force platoons remain under Marine technical direction. Taylor felt that the TAOR was overly restrictive and prevented an adequate defense of the airfield and the 8th RRU. He insisted that the Popular Forces be uniformed so they could be easily identified and offered that the Marines would provide the Popular Forces with uniforms if the ARVN would not provide them.23 The request was granted, and it became official and operational on 21 June 1965.

Expansion into Zone A

From early June onward, 3d Battalion, 4th Marines, pursued a dedicated and thorough civil affairs program to learn more about Zone A and to prepare for the moment when they were given full operational access to the area. First Lieutenant John J. Mullen was the adjutant and civil affairs officer for 3d Battalion, 4th Marines, and in that position directed or coordinated much of the activities involved.24

In early June, immediately following a meeting Lieutenant Colonel Taylor had with the village officials, the battalion began sending well-staffed medical clinics to all three villages on a semiregular basis. These mobile medical clinics were accompanied by a platoon from the infantry. This was not just for security; the infantry units were observing and learning about the villages as they provided security for the clinics.

By 15 June, it was known that the area of operations would be expanded into Zone A effective 21 June. On 15 June, First Lieutenant Mullen visited the district chief and the Popular Force platoon commanders to outline the plan to move Marines into the three villages for assessment and security operations. On 17 June, Mullen, along with the S-3 (the battalion operations chief), the S-2 (the battalion intelligence chief), the S-1 (the administrative chief), and a platoon from the reconnaissance battalion conducted a motorized patrol of all three villages. This was described as an observation patrol to familiarize the personnel aboard with the village characteristics and the Zone A terrain features.25

At 0730 on 21 June, the TAOR expansion went into effect. The battalion was also given operational control of the Popular Forces platoons in those villages.26 That morning, infantry Company K (-), Headquarters and Services Company (-), one platoon of Company C, 3d Reconnaissance Battalion, the battalion commander, the S-1, the S-2, and the S-3 patrolled through the southernmost village of Thuy Phu to familiarize the battalion personnel with the area and to become acquainted with the population. This movement, which would be carried out during three days, was called Operation Neighbor.27

For the next two days, Lieutenant Mullen and his team of battalion representatives went to each of the villages and conducted thorough surveys of each area. They assessed the Popular Force soldiers, the village officials, the nature of the terrain, and possible enemy approaches to and through each village, and they considered artillery concentration points. On each initial village contact, Mullen reported, the nucleus of the civil affairs operation was present. This included him as the civil affairs officer, an S-3 representative, the S-2, the counterintelligence officer, the engineer’s officer, a medical officer, the Vietnamese liaison officer, and an interpreter. During the first day it was decided, Mullen reported, to convene a civil-military advisory council with the goal of meeting soon for mutual cooperation and assistance.28

Lieutenant Mullen followed up the survey with meetings in the villages. On 28 June, a delegation went to Thuy Tan, the village grouping directly east of the base. They met with the village chief, the Popular Force platoon commander, and the Popular Force corpsman. They discussed a number of issues, including a medical program, locations for organized sales of goods to Marines, possible engineering projects, and local defense plans.29 On 30 June, the delegation went to the northernmost village of Thuy Luong. The records document that the delegation included the civil affairs officer (Mullen), a doctor, the chaplain, the provost marshal, and the S-2. They met with the village chief, the Popular Force platoon commander, and three village elders to discuss possible programs and problems in the village.30

On 30 June, the village survey was deemed complete. The battalion used Company C, 3d Reconnaissance Battalion, to scout, by patrol and by ambush, many of the Zone A areas previously forbidden to the Marines. The infantry was now able to regularly send night patrols around the outside of the perimeter wire, which improved the security of the base and the airfield.

During this time, the civil affairs program was in full force. On 3 July, Lieutenant Mullen went to the American consulate in Hue City and met the leading Buddhist layman in the area. They visited a Buddhist hospital and an orphanage and arranged a meeting for the Catholic chaplain from 3d Battalion, 4th Marines, to meet the Buddhist bishop of the area. Mullen was trying to find projects for the villages that would benefit Catholics and Buddhists alike. In the Zone A villages, Catholics made up about 5 percent of the population, with the rest being Buddhists. Both groups in the villages got along with each other.31

In July, the medical aid missions to each of the Zone A villages continued on a regular basis. They consistently drew more than 100 patients. The reconnaissance patrols also continued. They were now entering and patrolling through the interiors of the villages and increasing their forays as time progressed. Company C, 3d Reconnaissance Battalion, began learning about and assessing the skills and competence of the Popular Forces, conducting several patrols with them, including a few night ambushes.

Lieutenant Mullen had been closely involved with the expansion, pacification, and security efforts in Zone A since the beginning. He had been charged with developing the civil affairs program, which was inseparably tied to the Zone A security issues. Mullen stated that by mid-July he became concerned that the program was not progressing enough and that the situation was “status-quo.” He meant that the Marine patrols were meeting no resistance, the Popular Force platoons were not patrolling, and the village officials still had to hide at night. He learned that the Viet Cong were still taxing the villagers, and evidence of propaganda was present.32

Of primary importance was the fact that the Marines were getting no intelligence—one of the prime products of a civil affairs program—of enemy activity from the villagers. To address the problem, Mullen called a meeting with all three village chiefs (although the command records show a meeting between Mullen and only two of the village chiefs on 17 July).33

Lieutenant Mullen reported that the village chiefs, without reservation, expressed gratitude for the Marines’ effort and an appreciation that their villages were better off than ever before. They conveyed to Mullen that the missing element was security from the Viet Cong for the villagers. The chiefs declared that they were loyal to the government of the RVN and would like to help if they could but that none of the people could give information without the fear of reprisal. The Popular Force soldiers were no match for the Viet Cong, and Mullen said they “acted accordingly,” which likely means the Popular Force soldiers confined themselves to the village headquarters at night rather than aggressively pursuing the Viet Cong, thereby protecting themselves and their families.34

Mullen said he had an epiphany about the crux of the problem. The Marines had carried out their civil affairs program by the book, but they had neglected the important factor of security for the population. He understood now why they were not receiving any intelligence.35 This was a crucial observation. Mullen concluded that Marines were needed in Zone A on a more permanent basis.

The Creation of Combined Action

Lieutenant Mullen brought the situation to the attention of Major Cullen C. Zimmerman, the executive officer. They discussed the problem, and Mullen recommended that Marines be assigned to the villages to provide the missing security element. Major Zimmerman was receptive to the idea and called a meeting of the major figures involved.

The precise details and timeline of the combined action concept’s origin, the manner of approval, the selection of its commander, and the process of the selection of Marines for the program are rife with inconsistent accounts. The sources—including the combination of original records, recorded interviews, unrecorded interviews, written documents, missing interviews, and other missing documents—have made it difficult to determine certain facts precisely. Compounding the problem are the various studies and academic papers that have relied, with different degrees of accuracy, on the records available at the time of their writing. Regarding the historical outcome, however, these inconsistencies are only marginally important to the essence of how the combined action units came into existence and how they were initially employed.

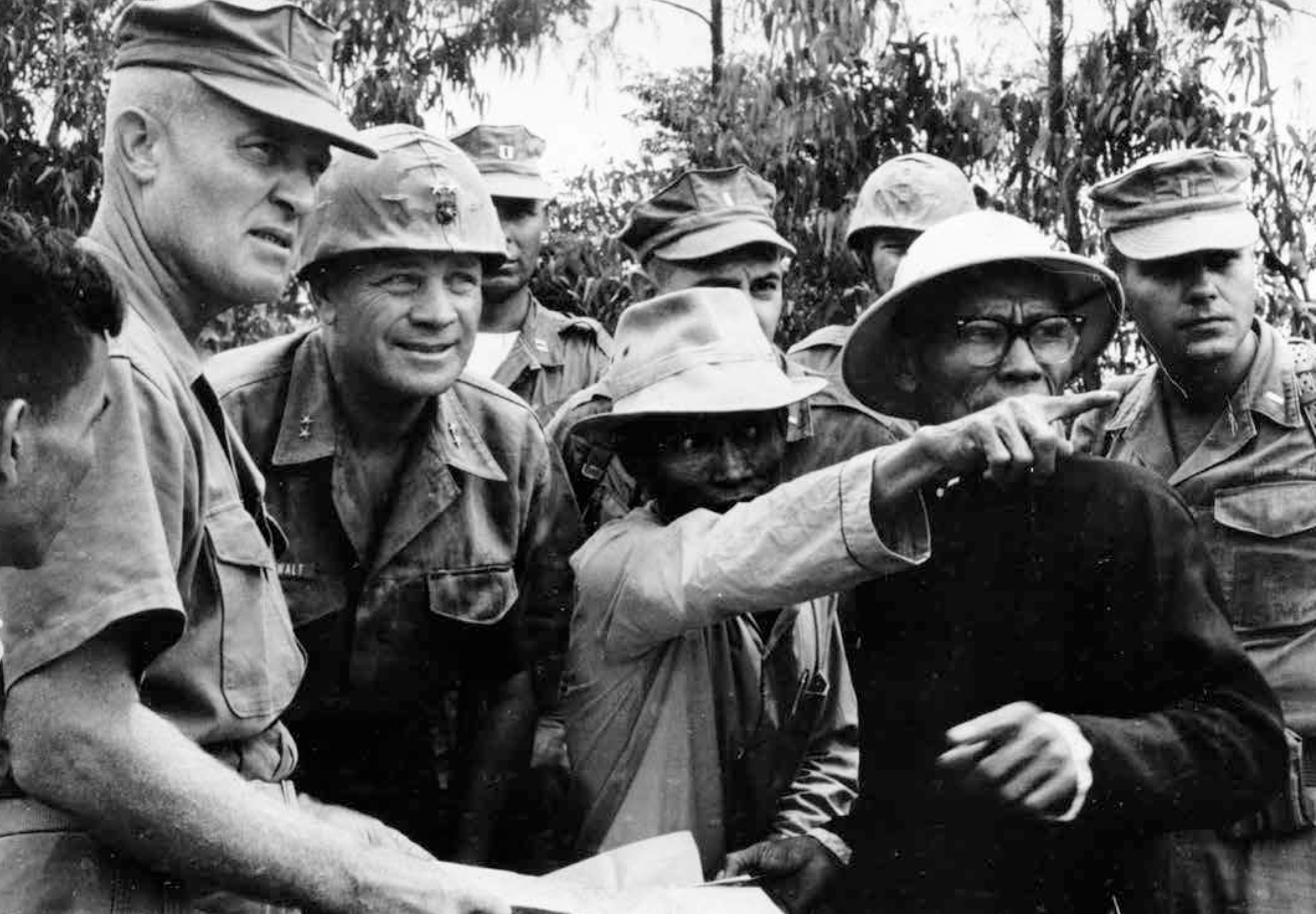

The chief of Thuy Phu village pointing out to Gen Walt the surveyed artillery concentrations in connection with the Combined Action Program. To the general’s right is LtCol William Taylor, commander of the 3d Battalion, 4th Marines. On the far left is 1stLt John J. Mullen, one of the creators of the Combined Action Program. It is believed that standing behind the village chief is 1stLt Paul Ek, the first commander of the Joint Action Company (JAC). Photo by WO Jim Smith, courtesy of Historical Reference Branch, Marine Corps History Division

The meeting called by Major Zimmerman regarding Lieutenant Mullen’s observations and recommendations was attended by the S-3, the S-2, Mullen, and Zimmerman. Mullen writes that all agreed to the concept of assigning troops to the villages except for the S-3. The S-3 (operations) was worried about the utilization of troops and the plan’s impact on causalities. Once they moved past his dissent, three plans were proposed and discussed.36

The first plan was to have one company from the battalion be responsible for all aspects—civic action and security—for one village. According to Mullen, this plan was rejected for several reasons: 1) each company would be reduced to two rifle platoons, which would make them less effective for other combat missions; and 2) there was concern that there would be no continuity or unity of effort among the villages. The second plan was to make one infantry company responsible for all of the villages in Zone A, which was also rejected, because it would deprive the battalion of a whole maneuver element that could prove decisive in an operation.37

The third plan was to use a smaller group of Marines to supplement the Popular Force soldiers, and it was accepted. They discussed whether the group should be a platoon or a squad for each village and decided that the squad would be the best use under the circumstances.38 Mullen reported, seemingly with enthusiasm, that the squad was decided on as a “revolutionary” and “speculative” concept.39 Major Zimmerman, in an oral history interview, confirmed that the concept of the CAP was the product of a number of Marines throwing around ideas and finally settling on one that seemed to make sense.40 It is not totally clear who originated the combined action concept. Mullen does not take credit for it in his 1968 written study, and Major Zimmerman, when asked about the topic in an interview, was also equivocal about Mullen’s role in developing the concept. General Lewis W. Walt, the former commander of all Marine forces in Vietnam—in his memoirs, Strange War, Strange Strategy—credits Lieutenant Mullen “unequivocally” as originally coming up with the idea. General Walt stated this in the context of mentioning that others have tried to take credit for the concept’s origination.41 It should be clear, regardless of who uttered the first words about combining Marines and Popular Force soldiers, that Lieutenant Mullen played an important role in the creation of the combined action concept.

Lt Paul Ek discussing a tactical situation with the police chief and an interpreter in one of the Joint Action Company villages. Photo by SSgt C. Durie, courtesy of Historical Reference Branch, Marine Corps History Division

Once the concept was agreed upon, Major Zimmerman presented it to the battalion commander, Lieutenant Colonel Taylor, who approved. Mullen believed it was presented on 20 July 1965.42 Major Zimmerman says that Taylor asked him to develop the details of the proposed combined force so that he could present it to the chain of command. Taylor said that once Zimmerman finalized the plans, he presented them to his regimental commander, Colonel Wheeler. And eventually, he presented them to Major General Walt and Lieutenant General Victor H. Krulak.43 The precise timing of the presentation to Generals Walt and Krulak is unclear. The program was implemented too quickly for there to have been a lengthy approval process.

Major Zimmerman wrote in 1968 that the concept in his mind was not the Marines’ use of indigenous troops during the Banana Wars, but the British practice of brigading British troops with native units.44 In a 1991 telephone interview with Duane Weltsch, Zimmerman elaborated that he had drawn from his knowledge of the British Army’s experiences in nineteenth century India.45 He felt this concept would leave the Popular Force platoons intact and allow them to better assume responsibility on their own when the Marines eventually left the area. He also wrote that during the discussion phase, one idea had been to continue the existing policy but to use the Marines in a U.S. Special Forces-style advisory role, but that concept was rejected.46

The timetable shows that the concept moved quickly to execution. By 1 August, at least three squads had gone through a week’s training and were prepared to enter the villages. Major Zimmerman said that he hand-picked all of the Marines. He instructed the company commanders to give him a full squad of volunteers, but not the best men from each company. He did not want the companies to sacrifice their capabilities, but he did insist on quality Marines. He went through the service records of each Marine and had to reject some who he felt were not qualified. Zimmer- man said they ended up with experienced sergeants who had several years in grade and with corporals who at one time or another had filled the role of a squad leader.47

First Lieutenant Paul R. Ek was brought in from the 3d Marine Regiment and given command of the program. Historian Jack Shulimson suggests that Lieutenant Ek was specially selected in response to discussions that Lieutenant Colonel Taylor had with Colonel Wheeler.48 While no documentation of this exists in the official records, this version of events makes sense. Colonel Wheeler, as commander of the 3d Marine Regiment, was responsible for the defense of the Phu Bai base and the airfield. He was in a senior and direct command position to Lieutenant Colonel Taylor. It would be in his best interests to make sure this unique program was successful and the base was fully protected. Lieutenant Ek was also an excellent choice because he spoke Vietnamese to near fluency and had been assigned to work counterinsurgency earlier in the year as an advisor with the Special Forces in Vietnam.49

On 23 July, Lieutenant Mullen, in his capacity as civil affairs officer, held an advisory council in the officer’s mess with all the village chiefs, the hamlet chiefs, and the Popular Force platoon leaders located in the TAOR. The records state that mutual military and civilian problems were discussed. The officials were then taken on helicopter tours of the area. The records show that the reaction of the civilian officials was “very” favorable.50 An inference can be drawn from this meeting that the plan to bring in more Marines to secure the population was being presented to the relevant officials so that they could prepare the people and troops they represented.

On 25 July, according to Lieutenant Mullen, Lieutenant Ek arrived and was briefed that night. He began work immediately. In an interview in January 1966, after he rotated back to the United States, Ek provided his insights into the program and how he set about developing it into a functioning unit, with Marines fully integrated into the Popular Force platoons. While Lieutenant Mullen must be given credit for helping to create the concept and for laying the groundwork with his civil affairs program for a smooth entry of Marines into the villages, Lieutenant Ek must be given credit for taking the concept to the next stage. Ek trained the Marines and used his language skills to integrate the forces into working units. In his mission to secure the airfield, he developed, during a two-month period, a counterinsurgency program based on an understanding of the villages and their people.

After the selection of the Marines was complete, Lieutenant Ek trained them for about a week before they went out into the field on operations. This training was geared to teach them all aspects of counterinsurgency warfare, including techniques of population control and the role of civic action. He said they were thoroughly briefed on intelligence. They needed to know what to look for and what means would be used to gather important information. He trained them in the political and military structure of Vietnam and taught them important local rules. He felt it was critical for them to know their place in any setting of people before they entered a village. He wanted to teach them as much about Vietnam and the Vietnamese people as possible so they could live with the villagers as part of the community, while still carrying out their military mission.51 Lieutenant Mullen must have been an invaluable resource in the military and political structure, as well as some of the local rules, since he had been studying these matters since May as the head of the civil affairs program.

Combined Operations Begin

The Joint Action Company (JAC), as it was named at the time of its origin, was formed on the record on 1 August 1965. After training, the Marines were introduced into their villages and training with the Popular Forces, and operations began very soon. The chain of command was established with Marines in all leadership billets. The Marine sergeant became the combined unit platoon commander. The Popular Force commander became the executive officer of the platoon and second in command, performing the same role as a platoon sergeant in a Marine Corps platoon. With 30–40 men in the Popular Force platoon, they were divided into squads. The Marine corporals became squad leaders of a combined squad of four Marines and one squad of Popular Force soldiers. Lieutenant Ek was viewed by the village chiefs as their superior, although he said he treated them as equals.52 The Vietnamese district chief was Lieutenant Ek’s superior, although Ek said the district chief, who was a Vietnamese Army captain, treated him as his equal. Ek said that all of the Vietnamese officials and military personnel were cooperative. He cites the likelihood that the 1st ARVN Division commander sent word down for all to cooperate fully with this Marine effort.53

At first the JAC units did not focus on the villagers, but on learning the village well and working with their Popular Force counterparts.54 Lieutenant Ek continued his training of the Marines, and he trained them as a unit with the Popular Forces.55 This worked out well, and by design, it created a bond between the Marines and the Popular Forces. The classes were conducted either by Ek or by his executive officer, a Vietnamese lieutenant. They conducted classes on scouting, patrolling, hand and arm signals, population control, intelligence needs, marksmanship, and a variety of other skills that they would need to be able to work together.56

Cpl Earl J. Suter and a Popular Forces soldier work on the construction of a bamboo barracks for the first squad of the Joint Action Company, which lived with the villagers of Thuy Luong. All of initial Joint Action Company squads were in joint projects with their Popular Force soldiers and hand-built barracks for the Marines out of bamboo, tin, and thatch. Photo by Sgt Reid, courtesy of Historical Reference Branch, Marine Corps History Division

The first JAC patrol occurred on 3 August 1965. The squad was trucked out to Thuy Tan Village and arrived at 0925. The records do not show how long they stayed that day, but the typical daytime patrols in those first weeks were from early in the morning until midafternoon. All patrols at this time were trucked out from the command center at Phu Bai. The ride to the village would be no more than 10 minutes. On 6 August, three squads were sent out, one to each of the three villages. All three JACs began a regular routine of daylight patrols and activities in their respective villages.

There are no descriptions of these early patrols, so we can only speculate about their composition and routes. Lieutenant Ek instructed the Marines to learn the village while integrating into the Popular Forces through patrols and other security missions. The Marines had topographical maps and compasses, which along with a lot of patrolling, resulted in learning a village during a period of weeks. Each one of the villages was several square kilometers in size with multiple hamlets that contained networks of trails, houses, and thick vegetation.

On any operation, Ek had one or two Popular Force soldiers paired with a Marine. This gave the Marines the ability to closely observe how the Popular Forces handled themselves, and it gave the Marines the opportunity for personal training in the field. Ek says that close relationships were formed between the Marines and the Popular Forces. He remembered that once, a wedding was held up for two hours for the patrol to return so the Marines could attend. Lieutenant Ek seemed satisfied that the Marines and the Popular Forces came to trust each other, and if something happened, the Popular Forces could be depended upon for support because of the personal bonds that had been established. At the end of his tour in late September 1965, Ek remarked how the Popular Forces had improved in discipline and military manner. They carried their rifles like Marines, they always put on a cover when they went outside, and every day another Popular Force soldier showed up with a Marine-like haircut. Lieutenant Ek reported that the patrolling and ambush techniques of the unit as a whole were excellent.57

There was pressure to get night ambush or night patrols out as soon as possible.58 The security of the people was important to start the flow of local intelligence, but the immediate security of the base from any surprise, mortar or ground attack, required nighttime coverage of the potential inbound routes. At Thuy Luong or Thuy Tan, an enemy force could cross the river at any time. Likewise, a nighttime force could pass through Thuy Phu, which backed up to the hills leading to the mountains where the known enemy base camps were located. Since the April arrival of 3d Battalion, 4th Marines, there had been multiple contacts with groups of Viet Cong that were large enough to be taken seriously. During September 1965, 3d Battalion, 4th Marines, documented sightings of 259 Viet Cong in or near the TAOR.59

Intelligence from 3d Battalion, 4th Marines, as they were preparing to conduct an operation to search the jungle in the southern part of the TAOR, suggested that there was a potential for more organized Viet Cong units that had only temporarily gone up into the mountains because of Marine presence.60 The intelligence reports showed two enemy local force platoons had operated in the Zone A area. One platoon was the Huong Thuy platoon of 25 fighters, who had been operating in the village of Thuy Phu to the immediate south of the airbase along Highway 1. The An Nong platoon had operated in the village of Loc Bon, also known as An Nong, along Highway 1 to the south of Thuy Phu village. The intelligence report showed that both platoons had moved up into the jungle and operated exclusively from there once the Marines arrived in the Phu Bai area.

A Citroen sedan, familiar in Vietnam in the 1960s, drives on the main road through CAC 4 at Loc Bon village. The building in the background became the Marines’ barracks by 1966. Courtesy of Cpl Pete Nardie

The central area of Loc Bon village on Vietnam’s national Highway 1. The Marines are shown in the process of building bunkers and stringing concertina wire for extra security. The photo shows the daytime radio watch position, ca. 1966. Courtesy of Cpl Pete Nardie

According to Lieutenant Ek, the Viet Cong dominated the villages. He observed that there were no active enemy troops in the villages and they were left alone as long as the villagers paid their taxes or provided rice. Estimates have been made that there was a 20–35 percent domination of the village by the Viet Cong.61 One of the villagers’ great fears was the threat of acts of terror against them if they did not pay taxes to the Viet Cong or against village officials who worked in opposition to their goals. Lieutenant Ek felt, as did others involved, that the village chief and the Viet Cong had an unspoken agreement that if the Popular Forces did not aggressively patrol at night they would not be attacked. In essence, the village chiefs ruled the day, and the enemy forces ruled the night.62

The night patrols started soon and by 22 August 1965, in all three villages, night ambush or night reconnaissance patrols went out on a regular basis. Between 12 and 18 September, the Marines were staying in the villages overnight, coming into the base only one day. During this time, both day and night patrols occurred on a daily basis.63

The Phu Bai TAOR had been expanded at the time of the Zone A initial expansion to include another village and another Popular Force platoon, but a JAC unit was not placed there until late August. The village was Loc Bon, south of Phu Bai on the junction of Highway 1 and the Nong River. The Nong River, which emptied into a large bay several kilometers from the highway, flowed from south to north, coming out of the mountains, where the enemy forces were based in the jungle areas. The Nong River route—the river and the land routes following the river—would be active grounds for contacts between the Marines and the enemy. A JAC unit started operations in Loc Bon on or about 31 August 1965. The records show the first patrol going out that day.64

As the Marines were integrating into the Popular Forces and building an operating unit, Lieutenant Ek turned his attention to the population. He reported that it took a while to build trust with the villagers. One of the first things he did was to reframe the villagers’ view of the Marines as a source of financial gain. The Marines who had gone out earlier had given candy to children, cigarettes to adults, and paid higher-than-value rates for food. Ek stopped Marines from buying anything from the villagers for a period of time and banned the giving of candy and cigarettes. Over time, this accomplished his goal of setting the Marines and the villagers on a more equal footing. He instructed the Marines to sit down and talk with the people using sign language or other means, rather than giving out candy and cigarettes. He cited one example on a night patrol in a village where a boy called out “cigarette.” When the cigarette was not forthcoming, the boy said to the Marines, “You number 10.”65 Being exposed on a night operation could be deadly. Such incidents, instigated by villagers’ expectations of the Marines as a source of treats, could reveal a patrol’s location to any enemy forces in the area.

It took three or four weeks, but with all the night patrols, the Viet Cong stopped coming to the villages to collect taxes, to hand out propaganda, or to rally support. Lieutenant Ek reported that in this time, Marines got on “thoroughly intimate” terms with the people. They were no longer pestered for candy and cigarettes, and they were sold goods at Vietnamese prices.66

Ek also introduced the concept of population control. It was important to know everyone who was in the village. At that time, adult villagers were required to carry an identification card. Without warning, the Marines and the Popular Forces would cordon off a segment of a hamlet, approximately one kilometer square, and gather all the males for an identification check. They made sure the villagers were registered with the district and that the village chief knew them. Lieutenant Ek said that they apologized for the inconvenience and the people seemed to accept the procedure. According to Ek, the procedure took between two to three hours and occurred just as dawn was breaking.67

The Marines also checked the village marketplaces randomly for outsiders purchasing supplies for the Viet Cong. There was a limit of 12 pounds of rice per day that anyone could purchase. On more than one occasion, they caught individuals—mostly women—purchasing larger quantities of rice. On one occasion, five women bought 80 pounds of rice. Investigation showed that it was purchased for enemy forces based a few kilometers away in a nearby district.68 The more the JACs built trust with the people and kept them secure, the more intelligence of this nature would flow into the units.

Lieutentant Ek used the tool of civic action projects to build relationships with the villagers. They did not perform random acts, but helped when a need was discovered. For example, the season was especially dry, and the village wells had not been dug deep enough to compensate. The Marines helped to dig deeper wells so the villagers did not have to carry fresh water as far. In another example, rains had washed away the ends of a bridge, leaving a gap of 1.5 feet that carts or vehicles could not cross, making it more difficult to get their goods to market. The Marines started working on the bridge and filling it in with anything they could find, and several villagers who saw this pitched in, and it became a joint project.69

1stLt Wayne Henderson (left), a forward observer with Company I, 3d Battalion, 12th Marines, providing artillery support to the JAC units in Phu Bai. This photo was taken while they were out checking on artillery concentrations in Thuy Phu villages. Standing next to Henderson are two Marines from the JAC. Courtesy of 2dLt Richard M. Cavagnol

Thuy Phu village market. Courtesy of Cpl Ed Matricardi

Soap was a luxury to the villagers at this time and it was conserved. The Marines provided soap to as many people as possible at the medical clinics, but they also started a baby washing service as a teaching tool. The Marines set up an assembly line system with one Marine washing a child, another rinsing the child, and a third dressing the child.70 It is unknown what real effect this project had, but it may have softened the Marines’ image and brought them closer to the villagers. Stories such as this often spread from hamlet to hamlet as villagers gathered at the markets and other venues and exchanged news.

Intensified Operations and Mission Change

Lieutenant Ek left the unit to rotate home on 25 September 1965, and Lieutenant Mullen replaced Ek as the company commander. The unit’s name was soon changed to Combined Action Company (CAC).71 This change was made because the command felt that this reflected better the character of the unit. Mullen said the reasoning was that it was not a joint operation between units but one combined unit made up of men from each country.72 In late 1967, the name was changed again to Combined Action Platoon (CAP) due to a potential unfortunate meaning of the word cac to the Vietnamese.73 CACs were assigned unit numbers (CAC 1, CAC 2, etc.). CAC 1 was assigned to Thuy Luong, the northernmost village in Zone A. CAC 2 was placed in the village of Thuy Tan at the eastern flank of Phu Bai Air Base. CAC 3 was positioned immediately south of Phu Bai Air Base in the village known as Thuy Phu (sometimes referred to as Phu Bai village). CAC 4 was placed the furthest south in the village of Loc Bon, along the Nong River.

Mullen made some immediate operational changes in the program, suggesting that he had a different opinion regarding the enemy threat and the need to confront it. First, he moved the Marines to the villages on a permanent basis; he began a program of saturation patrolling; and he demanded 100 percent alert at night. Operationally, he emphasized ambush and multiambush patrols. He also intensified combined training and concentrated it on marksmanship and small unit tactics, and he placed a new emphasis on population control and intelligence gathering.74

In the time period when Lieutenant Mullen took command of the combined action program, the patrol protocol—at least in CAC 3 at Thuy Phu village—was for all Marines to go out on night patrol with 10–15 Popular Force soldiers. They would leave at darkness and not return until daybreak. Patrol routines varied. Some nights they would go straight to an ambush site, and others they would patrol for a long period and then set up an ambush late, close to daybreak. When Private First Class Claude Martin first arrived at what was known as CAC 3 in very late September or early October, they stayed in the village headquarters building located on the highway, which was the main road through the village. Soon, the Marines and the Popular Force soldiers built a crude structure using bamboo framing and corrugated walls and roof. At that time, the sergeant, the corpsman, and the radio- man remained based out of the village headquarters building and the rest of the Marines used the shack for their quarters.75

There had been no significant contacts between combined action units and enemy forces at the time Lieutenant Mullen took over. Intelligence, however, showed a potential threat nearby. One of the infantry battalion’s thrust points (focus of operations) had been near the jungle to the direct south of CAC 3 and CAC 4. This area generally follows the Nong River south into the jungle and into the mountains and was a main route for units east of Phu Bai to get to the lowlands. It would become even more important as a route in the future. The village where Loc Bon was located was once the base and operating area of the Viet Cong local force platoon called the Loc Bon or the An Nong platoon. The intelligence showed that when the Marines of 3d Battalion, 4th Marines, arrived and began their operations, the Loc Bon platoon moved its base into the jungle several kilometers south of the village.76

A major change to the philosophy of the program also occurred when Lieutenant Mullen assumed command. Previously, the ultimate goal of the mission had been to secure the Phu Bai Air Base from possible attack through the Zone A villages. That goal remained, but the program was broadened in the direction of a full-fledged effort to increase good relationships with the people and improve their welfare. Mullen was involved with Zone A from the beginning, and it appears that he incorporated his civil affairs orientation into the military integration of the Marines with the Popular Forces. Mullen proposed his new concept and the battalion commander approved and directed this new mission be put into effect, the elements of which were:

- Secure the populated areas and deny their use to the enemy, thereby supporting the battalion primary mission and providing security for the civilian population.

- Establish and maintain an effective civic action program, in conjunction with local officials, for the purpose of improving the welfare of the people, increasing good relationships between the people and friendly forces, establishing an effective intelligence network; and

- Train the Popular Force platoons so that in the future they would be capable of protecting their own villages without U.S. troop assistance.77

Mullen said that the “intensified” operations began immediately.78 The first major contact between a CAC unit and the enemy occurred on 27 September. An ambush patrol from the Loc Bon CAC, known as CAC 4, was heading out toward the incoming enemy route to intercept Viet Cong coming toward the village. They went out approximately 1.5 kilometers from the headquarters into a prime area on the enemy routes from the jungle and encountered a group of 20 Viet Cong, and a firefight began.

Two enemy fighters and one Marine were killed. The enemy broke off contact and headed back up toward the hills. Corporal Edwin J. Falloon was in the point team and was the first combined action Marine to die in Vietnam. Two men on the patrol were wounded. The weapons found on the dead fighters were a semiautomatic rifle and a Chinese submachine gun.79 The weapons suggest that this was a Viet Cong local force company, quite likely the Loc Bon company that had been pushed up into the jungle when the Marines entered Phu Bai. A group of 20 was too big to simply hold rallies or spread propaganda leaflets.80 Lieutenant Mullen sensed that after this incident the population gained more confidence in the CACs’ ability to protect and secure them from the enemy. He saw that the Popular Force soldiers were becoming more efficient. Intelligence began to come in on a regular basis, first through the village chief and then directly by the people. The National Police began to take the CACs more seriously too and started actively providing them with intelligence. By November, 75 percent of the CAC operations were based on intelligence. Viet Cong activity in the villages ceased. Mullen noted that the villagers and the Marines had totally accepted each other. He stated that one of the greatest hallmarks of the program’s success was that eventually village officials stayed in their own homes again during the night.81

Following the 27 September incidents, there were several more contacts between CACs and the enemy forces. Most of these were either in CAC 3 or CAC 4 on the outer edges of the villages, consistent with groups coming down from the mountains. Both of those CACs sat on the direct trail from the Viet Cong jungle camps. Whatever intelligence was provided resulted in the CACs catching fighters coming into the village. There is a high likelihood that these ventures into the village were to obtain rice.82

The local force Viet Cong units depended on tax collections to support their operations. They also depended on rice grown by the villagers in the lowlands. When they were pushed up into the mountains, rice and other foodstuffs became difficult to obtain. They could not grow rice in the jungle camps, but they needed it daily to survive, so they had to come to the lowland villages to obtain it and other supplies. The Marines of 3d Battalion, 4th Marines, had learned through captured enemy fighters that the typical procedure was to make contact with a designated rice supplier, who delivered the rice to a collection point.83 Rice was always an issue, but before the local Viet Cong units were driven up into the hills, they had easy access to foodstuffs.84

In November 1965, CAC 3 experienced incidents three nights in a row. On the night of 29 November, however, the CAC 3 patrol heading out to attempt to intercept Viet Cong coming down from the mountains ran into an inbound group of 20 enemy. A sustained firefight ensued that resulted in four confirmed kills at the firefight site and the capture of a wounded Viet Cong corpsman the next day. Three weapons were captured, including a Chinese K50 submachine gun and a French-made MAT-49 submachine gun (used extensively in the first Indochina war), along with 718 piasters (Vietnamese currency) was found on one of the bodies.85 There were few reasons, aside from the intent to purchase rice and other supplies, for Viet Cong forces to be carrying money on a night patrol. They had not been to a village yet and they were coming from the jungle camps. The amount of money found was substantial. For comparison, Lieutenant Ek said that tax payments to the Viet Cong in the Zone A villages for villagers with a concrete house were 500 piasters. Villagers with thatched roof houses paid 300 piasters.86

Intelligence gathering and security efforts worked hand in hand to make for stronger and safer CACs. The more the CACs were trusted, the more intelligence came in from more sources. Consequently, the CACs gained more power to protect their villages. Lieutenant Mullen remained as the program commander through April 1966.87

Expansion of the Combined Action Concept

While the original Phu Bai combined action units were technically an experiment, the concept soon became an accepted part of the Corps’ counterinsurgency pacification strategy. The Phu Bai CACs became a model for future CACs and they were an inspiration to General Walt and the III MAF command.

The Marine command realized that the Popular Force platoons occupied hamlets and villages in key places to protect military installations and main supply routes. While the Marines were able to clear those areas of Viet Cong forces, however, the Popular Force soldiers proved inadequate to hold the cleared villages. A vacuum was created, and when the Marines moved on, the Viet Cong flowed back in and began their insurgent activities again.88 By October 1965, in the opening words of the FMFPac command chronology summary, the Marines were experiencing “more and more emphatically, the realities of counterinsurgency war.”89

General Walt tried to protect his rear areas from attack and at the same time aggressively move into uncleared areas to clear them with as many maneuver battalions as he could afford. The cumulative military installations at Da Nang were the nerve centers of the Marine Corps operation in Vietnam. At Da Nang was the main Marine Corps’ air base, which could handle planes of any size and began to rival the traffic of the busiest airports in the world. There was a large peninsula to the east of the air base across the Han River, on which were located several important facilities including the III MAF headquarters and the main

Marine helicopter base for the entire TAOR. There was also a sizable city in the middle of the area and a deep-water port where sometimes ships would line up for days to bring critical shipments of supplies into Vietnam. Protecting this operation was of the highest priority.

Da Nang was vulnerable to attack. Scattered in and around the Da Nang military complex were numerous villages and hamlets. Close to Da Nang the population was dense. The villages and hamlets extended out into the countryside for several kilometers in all directions. The villages, with plenty of vegetation, could and did easily hide enemy troops readying to make ground assault on the airbase, mortar attacks, and even rocket attacks.

In July 1965, an enemy attack against the airport occurred from the south that destroyed two Lockheed C130 Hercules transport planes and one Convair F-102 Delta Dagger jet fighter and damaged others. This attack caused the Vietnamese to open up the territory immediately south of Da Nang for clearing by the Marine infantry.

On 28 October 1965, a group of Viet Cong commandos attacked the Marble Mountain Air Facility in Quang Nam Province, the naval hospital under construction, and the Mobile Construction Battalion 9 (MCB-9) camp. The commandos destroyed 19 and damaged 21 more of the 60 helicopters based there. At the same time, 50 miles to the south at Chu Lai, the enemy destroyed two Douglas A-4D Skyhawk fighter jets at the Marine air base.

On 30 October 1965, in an area several kilometers southwest of Da Nang, Marine infantry clearing forces were attacked by a force of 300–400 main force Viet Cong. Company A of the 1st Battalion, 1st Marines, was at an established company base camp on a slight rise called Hill 22. There were a total of 154 Marines on the hill and 81 men on the perimeter when they were attacked in the early morning hours. Preceded by mortars and 57mm recoilless rifles, the attackers were able to break though Company A’s wire on the northwest side. The attack lasted approximately an hour before the attackers could be ejected from the Company A perimeter. The action resulted in 16 Marines killed and 45 wounded. Confirmed enemy killed were 47, although it was believed that more than 100 dead fighters were carried from the battlefield. It was later learned that the attackers came from three Viet Cong main force companies and two local force companies.90 The 3d Marine Division wrote that it “was first large scale attack on Marine positions in any of the TAORs.”91

These attacks and other incidents factored into the III MAF assessment to better protect the rear areas. They pursued control of the Popular Force platoons so that more Marine and ARVN forces could move forward to clear and drive the Viet Cong and their main force units out of the TAOR. Da Nang and the Quang Nam Province had 34 Popular Force platoons.92 Many were located in key areas that would provide protection for the massive military presence at Da Nang. General Walt recognized both the value and the weakness of the Popular Force platoons, and the command realized the key was to gain command control of all Popular Forces in the I Corps.93

Bolstered by the success of the CACs in Phu Bai, Walt envisioned placing CACs to the extent possible in selected Popular Force platoons. Following the positive results in the Phu Bai area CACs and influenced by the potential of more attacks on Da Nang and the Marble Mountain area, General Walt had the support of the ARVN command to expand CAC and take control of the Popular Forces.

General Walt pursued permission to take command of the Popular Forces. He first was given authority in late November 1965 over eight Popular Force platoons in the Da Nang Air Base general area. The 3d Battalion, 9th Marines, began training Popular Forces on 7 December 1965.94 The training of these Popular Force platoons from the perimeter locations of the Da Nang Air Base continued throughout January 1966.95 By 17 February 1966, 1st Battalion, 9th Marines, took over as the air base defense battalion. They reported on 18 February 1966 that a CAC had been formed during this period and the individual units were in six locations around the perimeter of Da Nang Air Base.96 There were many more Popular Force platoon locations, however, where CACs would be appropriate and useful.

General Walt next pursued authority over all Popular Force units in I Corps, submitting a formal request on 5 January 1966. On 28 January, Walt was granted written permission by General Thi, commander of I Corps, for command and control over all Popular Forces in I Corps.97 In a letter dated 4 February 1966 to the commanding general of the 3d Marine Division, General Walt directed that the commanders in each TAOR coordinate closely with each Popular Force unit in their area of operations; to provide communications, supporting arms, and reserve forces; and to place Marines with selected Popular Force units. He also directed that Popular Force units in proximity to each other be formed into CACs (companies.) He stressed the role that the Popular Forces would play: “The importance of the Popular Forces to provide security for the rear areas which will allow Marine/ARVN combat forces to move forward, cannot be overstated.”98 In the Da Nang TAOR, Walt would need all the resources he could muster to clear and hold the 54 villages and 241 hamlets, covering 395 square miles, with a population of 265,767. For comparison, the Phu Bai TAOR had 9 villages and 62 hamlets, covered 76 square miles, and had a civilian population of 36,131.99

The process of expansion started almost immediately. Internal Vietnamese political turmoil brought the expansion of the program to a virtual standstill. In June 1966, after three months, the program began to regain its thrust.100 By July, there were at least 19 CACs in the Da Nang enclave placed in critical areas around the airfield and covering the peninsula where the Marble Mountain facilities were located.101 Some of these CACs were placed to the immediate north and to the west/northwest of the airfield, as well, to protect those flanks.102 Five CACs were farther out along the southwest inland main supply to the Dai Loc District. They helped to protect the main supply route (a dirt road) and the western flank of the TAOR.103 Eight Marine infantry battalions, one reconnaissance battalion, and the 1st Military Police battalion, in an ongoing effort to drive out the presence of the Viet Cong, conducted saturation patrolling throughout the Quang Nam Province, including the areas where CACs were placed in the outlying areas. The total number of patrols during July 1966, including ambush patrols, was 5,820.104

While Da Nang was a first-priority expansion, the Chu Lai enclave also began working with the Popular Forces to form CAC units. Unlike Da Nang, Chu Lai was not built in a highly populated area. The Marines selected Chu Lai as a base due to its geographic location and its suitability to build a full-length combat airfield. It was a new base with an airfield that had been constructed in May 1965. There were fewer existing Popular Force platoons in Chu Lai, but the Marines there also began working with Popular Forces. By the end of summer 1966, several CAC units had been established there in a similar pattern to protect the flanks of the airfield, the supply routes, and other military installations from ground and mortar attacks.

The expansion of CAC continued in spurts for the next three years. In mid-1967, the program became an independent organization under the direct command of III MAF and took on its most well-known name, the Combined Action Program. At this time, the individual platoons were called Combined Action Platoons (CAPs). The original units in Phu Bai remained the basic model for CAPs everywhere, until the program phased into totally mobile units beginning after the Tet offensive of 1968.

•1775•

Endnotes

- William F. Nimmo holds a juris doctor degree from Loyola Law School, Los Angeles, CA. He spent nearly 40 years as a criminal trial lawyer. He was an assistant CAP leader in CAP Alpha 7 near Hue in 1967 and 1968. Assisting in the research for this article was Henry Beaudin, a former CAP Marine, who served in 1969 and 1970, southwest of Da Nang. Author’s statement: as the author researched the Combined Action Program’s creation, he discovered that the extant historiography on CAP either were not precisely accurate or dealt with the program’s creation only briefly. This work makes extensive use of the primary sources available to paint a very detailed picture of the program’s creation and the preparations of the villages in advance of implementation with effective civic action programs.

- The historiography can be a bit vague about the proper use of CAP. For our purposes, CAP refers to Combined Action Platoons; when referring to the Combined Action Program as a whole, we will use the full reference and not the acronym.

- There were several categories of enemy forces operating in South Vietnam. Viet Cong is the general term the Americans used for enemy forces that were not officially part of the North Vietnamese Army. It refers to political operatives, small insurgent cells, local force platoons and companies, and organized larger main force units (company and battalion size) that operated on a wider geographical basis. Such forces were routinely referred to in Marine Corps command chronologies and intelligence re- cords of the time as Viet Cong and are distinguished only by the force organizational size and purpose. The author’s usage of Viet Cong is based on how enemy forces were identified in the Marine Corps source documentation consulted.

- III Marine Amphibious Force (MAF) Command Chronology (ComdC), January 1966, RF/PF Improvement, item number 1201002108, U.S. Marine Corps History Division Vietnam War Documents Collection (USMCHD Vietnam War Docs), Vietnam Center and Archive, Texas Tech University, hereafter Texas Tech Vietnam Center and Archive, 3.

- Bruce C. Allnutt, Marine Combined Action Capabilities: The Vietnam Experience (McLean, VA: Office of Naval Research Group Psychology Programs, 1969), 37.

- Operations of the III MAF, Vietnam, Fleet Marine Force Pacific (FMFPac), 1 October 1965, item number 1201001017, folder 001, USMCHD Vietnam War Docs, Texas Tech Vietnam Center and Archive, 2.

- When the program was first initiated, embedded units were referred to as Joint Action Companies (JACs); as the program evolved, they became known as Combined Action Companies (CACs) and finally as Combined Action Platoons (CAPs). While the name for the units evolved throughout the program’s life, this article refers to them generally by the last-used term, CAP(s), unless specifically discussing a period during which the platoons were referred to as JACs or CACs.

- Allnutt, Marine Combined Action Capabilities, table A-1, A2.

- Rick Schelberg, “CAP KIA Lists,” CapMarine.com. Before CAPs became more organized, battalions recorded their members who were killed in action (KIA). In the authors’ examination of the chronologies, it was discovered that several were not recorded on the cited lists. The authors therefore estimated.

- Fact Sheet [combined action force], 31 March 1970, item number 1201061098, folder 061, USMCHD Vietnam War Docs, Texas Tech Vietnam Center and Archive, 31, enclosure 8.

- Operations of the III MAF, Vietnam, FMFPAC, March September 1965, item number 1201001016, folder 001, USMCHD Vietnam War Docs, Texas Tech Vietnam Center and Archive, part A, 5, 17, and Part B, 21, 26, 29.

- LtGen Ngo Quang Truong, Territorial Forces (Washington, DC: U.S. Army Center of Military History, 1980), 30.

- Jack Shulimson and Maj Charles M. Johnson, U.S. Marines in Vietnam: The Landing and the Buildup, 1965 (Washington, DC: History and Museums Division, Headquarters Marine Corps, 1978), 22.

- Lewis Walt, interview with Martin Russ, 31 July 1976, tape 6329–30A, Oral History section, Marine Corps History Division, segment beginning at 26:42.

- Operations of the III MAF, Vietnam, FMFPAC, March– September 1965, part B, 21.

- “Narrative,” 3d Battalion, 4th Marines, ComdC, 1 April 1965, item number 1201045069, folder 045, USMCHD Vietnam War Docs, Texas Tech Vietnam Center and Archive, 2.

- “Statistical Highlights,” Operations of the III MAF, Vietnam, FMFPAC, 1 March 1965, item number 1201001016, folder 001, USMCHD Vietnam War Docs, Texas Tech Vietnam Center and Archive, part B, 25–27.

- “Narrative,” 3d Battalion, 4th Marines, ComdC, 1 June 1965, item number 1201045070, folder 045, USMCHD Vietnam War Docs, Texas Tech Vietnam Center and Archive, 1–7; “Narrative,” 3d Battalion, 4th Marines, ComdC, 1 July 1965, item number 1201045071, folder 045, USMCHD Vietnam War Docs, Texas Tech Vietnam Center and Archive, 1–6; “Narrative,” 3d Battalion, 4th Marines, ComdC, 1 August 1965, item number 1201045072, folder 045, USMCHD Vietnam War Docs, Texas Tech Vietnam Center and Archive, 1–8; “Close Combat,” 3d Battalion, 4th Marines, ComdC, 1 September 1965, item number 1201045073, folder 045, USMCHD Vietnam War Docs, Texas Tech Vietnam Center and Archive, 1–7; and “Close Combat,” 3d Battalion, 4th Marines, ComdC, 1 October 1965, item number 1201045074, folder 045, USMCHD Vietnam War Docs, Texas Tech Vietnam Center and Archive, 1–8.

- Capt John J. Mullen Jr., “Modifications to the III MAF Combined Action Program in the Republic of Vietnam,” Individual Research Papers Collection, Capt John J. Mullen Jr. 1968–69, COLL/3953, Archives Branch, Marine Corps History Division, Quantico, VA.

- “Joint Company, Intelligence,” 3d Battalion, 4th Marines, ComdC, 1 September 1965, item number 1201045073, folder 045, USMCHD Vietnam War Docs, Texas Tech Vietnam Center and Archive, 3.

- Mullen, “Modifications to the III MAF Combined Action Program in the Republic of Vietnam,” C-4.

- Commanding Officer to Commanding General, 9th Marine Expeditionary Brigade, “Hue-Phu Bai defense arrangements,” 21 April 1965, 3d Marines, ComdC, April 1965, item number 1201037030, folder 037, USMCHD Vietnam War Docs, Texas Tech Vietnam Center and Archive, 29.

- “Zone A Hue Phu Bai,” 3d Marines, ComdC, 1 June 1965, item number 1201037034, folder 037, USMCHD Vietnam War Docs, Texas Tech Vietnam Center and Archive, tab 1.

- Situation Reports (SITREPs) no. 56–85, 3d Marines, 1–2 June 1965, item number 1201037035, folder 037, USMCHD Vietnam War Docs, Texas Tech Vietnam Center and Archive, hereafter SITREPS no. 56–85.

- SITREPS no. 56–85, 15–17 June 1965; and 3d Battalion, 4th Marines, ComdC, 1 June 1965, item number 1201045070, folder 045, USMCHD Vietnam War Docs, Texas Tech Vietnam Center and Archive, 4.

- “Joint Action Report,” 3d Battalion, 4th Marines, ComdC, 1 September 1965, item number 1201045073, folder 045, USMCHD Vietnam War Docs, Texas Tech Vietnam Center and Archive, 1.

- 3d Battalion, 4th Marines, ComdC, 1 June 1965, item number 1201045070, folder 045, USMCHD Vietnam War Docs, Texas Tech Vietnam Center and Archive, 5; and SITREPS no. 56–85, 20–21 June 1965. The notation (-) after company or unit names indicates the company or unit is not a full-strength company/ unit but is less some of its elements.

- Mullen, “Modifications to the III MAF Combined Action Program,” C-2, C-3.

- SITREPS no. 56–85, 28 June 1965.

- SITREPS no. 56–85, 30 June 1965.

- 1stLt Paul Ek, interview with LtCol D. J. Hunter, 24 January 1966, transcript, item number USMC0046, Oral History Section, U.S. Marine Corps History Division, Texas Tech Vietnam Center and Archive, 66, hereafter Ek oral history

- Mullen, “Modifications to the III MAF Combined Action Program,” C-4, C-5.

- SITREPS no. 86–116, 3d Marines, 16 July 1965, item number 1201037037, folder 037, USMCHD Vietnam War Docs, Texas Tech Vietnam Center and Archive.

- Mullen, “Modifications to the III MAF Combined Action Program,” C-4, C-5.

- Mullen, “Modifications to the III MAF Combined Action Program,” C-4.

- Mullen, “Modifications to the III MAF Combined Action Program,” C-5.

- Mullen, “Modifications to the III MAF Combined Action Program,” C-5, C-6.

- Mullen, “Modifications to the III MAF Combined Action Program,” C-6. Mullen’s report does not indicate the specific circumstances, but it is likely that they were a lack of large Viet Cong forces; a squad was sufficient to deal with the number of enemy they were likely to encounter.

- Mullen, “Modifications to the III MAF Combined Action Program,” C-6.

- Maj Michael Duane Weltsch, “The Future Role of the Combined Action Program” (master’s thesis, U.S. Army Command and General Staff College, 1991), 59; and Weltsch, interview with Col Cullen Zimmerman, 10 March 1991.

- Lewis W. Walt, Strange War, Strange Strategy: A General’s Report on Vietnam (New York: Funk and Wagnall’s, 1970), 105.

- Mullen, “Modifications to the III MAF Combined Action Program,” C-6.

- Weltsch, “The Future Role of the Combined Action Program,” 60.

- LtCol C. Zimmerman, review of The Betrayal, by LtCol William R. Corson, Marine Corps Gazette 52, no. 9 (September 1968): 14–15.

- Weltsch, “The Future Role of the Combined Action Program,” 59. It is unclear how much influence or impact the Marine Corp’s Banana Wars legacy had on the formation or the expansion of the Combined Action Program. Zimmerman is clear that he drew up the original plan and presented it to LtCol Taylor and that he drew on the British nineteenth-century experience of brigading troops with indigenous units. 1stLt Ek, who became the first commanding officer of the JAC unit, was later interviewed and commented that the program was patterned after the approach during the Banana Wars and that he understood it had also been done in Malaysia. Ek oral history, 9. 1stLt Mullen makes no mention of the historical origin of the concept. It is fair to state that the Corps’ experience in working with indigenous troops in the past, especially the experience in Nicaragua in the late 1920s, was a significant part of Marine Corps history. It is likely that the spirit of that history entered into the thinking of those involved in the creation and the expansion of the Combined Action Program. LtCol Richard J. Macak Jr., “Lessons from Yesterday’s Operations Short of War: Nicaragua and the Small Wars Manual,” Marine Corps Gazette 80, no. 11 (November 1996): 56–62.

- Zimmerman, review of The Betrayal.

- Weltsch, “The Future Role of the Combined Action Program,” 60–61.

- Shulimson and Johnson, U.S. Marines in Vietnam, 65, 133.

- Ek oral history, 1.

- SITREPS no. 86-116, 3d Marines, 23 July 1965.

- Ek oral history, 7.

- Ek oral history, 4.

- Ek oral history, 13.

- Ek oral history, 12.

- Ek oral history, 8, 27.

- Ek oral history, 8.

- “Combined Action Company Report,” 3d Battalion, 4th Marines, ComdC, item number 1201045073, folder 045, 1 September 1965, USMCHD Vietnam War Docs, Texas Tech Vietnam Center and Archive, A-2.

- Ek oral history, 8.“Intelligence Section,” 3d Battalion, 4th Marines, ComdC, item number 1201045073, folder 045, 1 September 1965, USMCHD

- “Intelligence Section,” 3d Battalion, 4th Marines, ComdC, item number 1201045073, folder 045, 1 September 1965, USMCHD Vietnam War Docs, Texas Tech Vietnam Center and Archive.

- Ek oral history, 18; and “Operation order 27–65,” 3d Battalion, 4th Marines, ComdC, item number 1201045072, folder 045, 1 August 1965, USMCHD Vietnam War Docs, Texas Tech Vietnam Center and Archive, Appendix 1, A-1-3, A-1-4.

- “Report: Joint Action Company (b) Intelligence,” 3d Battalion, 4th Marines, ComdC, item number 1201045073, folder 045, 1 September 1965, USMCHD Vietnam War Docs, Texas Tech Vietnam Center and Archive, enclosure 18, 3.

- Ek oral history, 25.

- “Daily journal,” 3d Battalion, 4th Marines, ComdC, item number 1201045072, folder 045, 1 August 1965, U.S. Marine Corps History Division Vietnam War Documents Collection, Texas Tech Vietnam Center and Archive; and “Daily journal,” 3d Battalion, 4th Marines, ComdC, item number 1201045073, folder 045, 1 September 1965, U.S. Marine Corps History Division Vietnam War Documents Collection, Texas Tech Vietnam Center and Archive. 64

- “Daily journal,” 3d Battalion, 4th Marines, ComdC, item number 1201045072, 1 August 1965, 34.

- Ek oral history, 9–11.

- Ek oral history, 11.

- Ek oral history, 15.

- Ek oral history, 16.

- Ek oral history, 23–25.

- Ek oral history, 24.

- number 1201045074, folder 045, 7 October 1965, USMCHD Vietnam War Docs, Texas Tech Vietnam Center and Archive. The last operation plan in September, dated 30 September 1965, set out dates in October using the heading “Joint Action Company,” but the first operation plan in October refers to the unit as Combined Action Company. The October chronology also lists the unit as Combined Action Company.

- Mullen, “Modifications to the III MAF Combined Action Program,” Annex C, C-11.

- CAC and CAP are interchangeable terms, and they are used here as they were used at the particular time period being discussed.

- Mullen, “Modifications to the III MAF Combined Action Program,” C-9.

- Claude Martin, interview with author, 4 May 2018. Martin is a former CAC Marine from Thuy Phu Village during November 1965.

- “Intelligence Section,” 3d Battalion, 4th Marines, ComdC, item number 1201045072, folder 045, 1 August 1965, USMCHD Vietnam War Docs, Texas Tech Vietnam Center and Archive, A-1–A-4.

- Mullen, “Modifications to the III MAF Combined Action Program,” C-9, C-10.

- Mullen, “Modifications to the III MAF Combined Action Program,” Annex C: C-10.