PRINTER FRIENDLY PDF

EPUB

AUDIOBOOK

At 0345 on 6 June 1918, First Sergeant Daniel A. Hunter assumed his position in front of the Marines from 67th Company, 1st Battalion, 5th Regiment. A portly veteran with graying hair and more than 20 years of service, Hunter was a legend in the Corps. As he strode in front of his company, he looked left and right to ensure that the ranks were properly aligned. When he heard a whistle blow signifying the attack, Hunter raised his cane above his head and brought it down in a sweeping motion, pointing toward the company’s objective more than 1,000 yards distant: Hill 142, held by German forces. The company moved forward in what was the opening battle of Belleau Wood, a month-long action that has become a defining moment in Marine Corps history.2 While there had been other local actions involving the offensive by American forces, most notably the U.S. Army’s 1st Infantry Division stopping the German attack at Cantigny at the end of May, this assault by the 1st Battalion, 5th Regiment, though local in nature, would set the tone and example for the 4th Brigade for the remainder of the war. It would also be the first sustained effort by the Marine Corps to provide committed forces to an extended land campaign; until then, Marines had only been used in amphibious actions. It brought the Corps into the high-intensity, high-casualty realm of modern war. No longer was the Corps merely the Navy’s police force. Finally, the assault would inspire confidence in French forces, credibility inside the American Expeditionary Forces (AEF), and respect among the German military and establish a reputation for the Marine Corps that is still recognized to this day.

As the untried Americans entered the war, the Germans wondered, “How would the Americans behave in a pitched battle?”3 An undated order from the German 28th Division to its soldiers, captured on 8 June, read:

Should the Americans to our front even temporarily gain the upper hand, it would leave a most unfavorable effect for us as regards the morale of the Allies and the duration of the war. In the fighting that now confronts us, we are not concerned about the occupation or non-occupation of this or that important wood or village; but rather as to the question as to whether Anglo- American propaganda, that the American Army is equal to or even superior to the Germans, will be successful.4

This article seeks to trace the actions of the 1st Battalion, 5th Regiment, on 6 June 1918 as a limited attack at the beginning of the epic battle in the game preserve of Belleau Wood. It also seeks to highlight the individual roles played by some of the veteran Marines—the “old breed”—of the battalion and their impact on new Marines. In the year between America’s entry into the war and the fight for Belleau Wood, the ethos instilled by veteran Marines into the young volunteers early in their training paid off as the veterans became casualties and the new Marines continued to carry the fight to the Germans.

Over There

When John W. Thomason Jr. penned his definitive work on the 4th Brigade in World War I, Fix Bayonets, he wrote of

a number of diverse people who ran curiously to type, with drilled shoulders and a bone-deep sunburn, and a tolerant scorn of nearly everything on earth. Their speech was flavored with navy words. Rifles were high and holy things to them, and they knew five-inch broadside guns. They were the Leathernecks, the Old Timers: collected from ship’s guards and shore stations all over the earth to form the 4th Brigade of Marines, the two rifle regiments, detached from the navy by order of the President for service with the American Expeditionary Forces. They were the old breed of American regular, regarding the service as their home and war as an occupation; and they transmitted their temper and character and view-point to the high-hearted volunteer mass which filled the ranks of the Marine Brigade.5

The 1st Battalion, 5th Regiment, was formed at Quantico, Virginia, during the last two weeks of May 1917 under the command of Major Julius S. Turrill. At least two members of the battalion already wore the Medal of Honor: Captain Roswell Winans (then a first sergeant) for actions in the Dominican Republic on 3 July 1916, and Marine Gunner Henry L. Hulbert for actions during the Philippine-American War (also referred to as the Philippine insurrection) on 1 April 1899.6 The battalion moved by train from Quantico to Long Island, where it boarded the USS DeKalb (ID 3010) and sailed for France on 14 June 1917, arriving on 26 June at Saint-Nazaire, where it disembarked on 27 June. The battalion spent the winter of 1917–18 training in the Breuvannes area of France. On 17 March 1918, the battalion deployed to the Verdun area, where it participated in minor actions against the Germans. Its first attack occurred on the night of 17 April, for which Second Lieutenant Max D. Gilfillan and Sergeant Louis Cukela were awarded the Croix de Guerre for their actions.7 In this action, the battalion suffered its first casualty when Corporal John L. Kuhn was killed. Kuhn and Privates George C. Brooks and Walter Klamm received citations for their actions.8

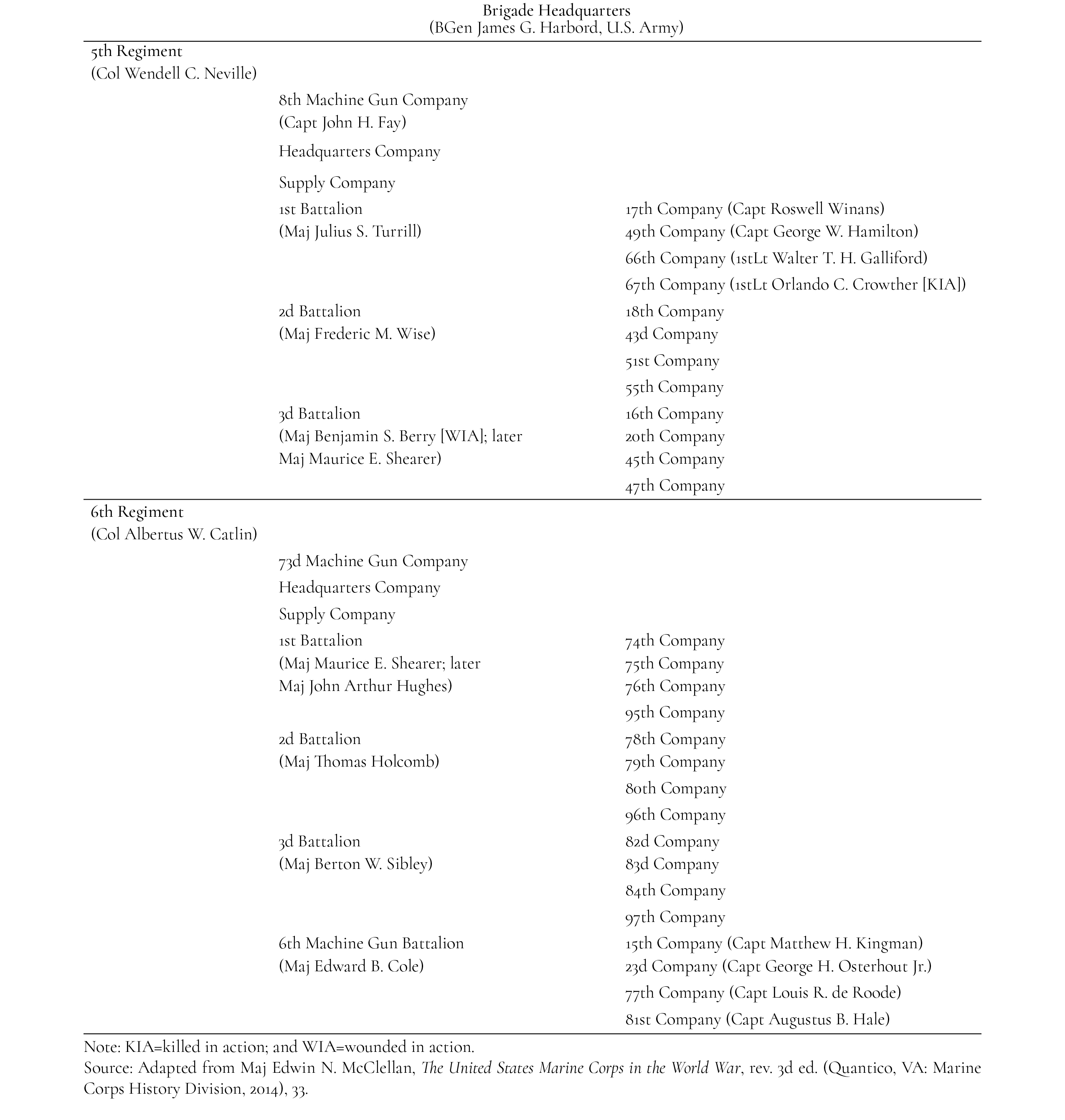

Table 1 4th Brigade Table of Operations, 6 June 1918

Adapted from Maj Edwin N. McClellan, The United States Marine Corps in the World War, rev. 3d ed. (Quantico, VA: Marine Corps History Division, 2014), 33.

In late May, the Germans launched the Chemin de Dames offensive toward Paris and the 4th Brigade was transferred to the Château Thierry sector about 72.4 kilometers (km) east of the capital city. The second of June found the 2d Infantry Division, of which the 4th Brigade was a part, occupying a 4.8-km gap in the French lines south of Belleau Wood, beginning at Lucy-le-Bocage and extending westward. Holding the right flank of the 4th Brigade’s line was 1st Battalion, 5th Regiment. While there, the 17th and 66th Companies, along with some elements of the 5th Regiment’s 8th Machine Gun Company, would be deployed to support the 2d Battalion, 5th Regiment, at Les Mares Farm. On 2 June, when the Americans reorganized their defensive positions, the remainder of the 1st Battalion, 5th Regiment, were withdrawn and became a brigade reserve located at Bois de Veuilly near Marigny. That respite would last until the early morning hours of 6 June. The battalion was on the verge of making the most extensive attack in the history of the Marine Corps to date; it numbered 22 officers and 953 enlisted—a total of 975 men.9

Marines of the 5th and 6th Regiments, 4th Brigade, arrive at the front, June 1918. Official U.S. Marine Corps photo

A Marine Corps officer in the field during World War I. This is how Capt Hamilton and 1stLt Crowther likely would have looked on 6 June. In this era, Marine officers and senior noncommissioned officers carried canes. Company Commander, John W. Thomason Jr. Ink on paper. Art Collection of the National Museum of the Marine Corps

The Objective

Alternating woods and wheat fields covered the entire region. In late spring, the woods were green and the wheat in the fields was thigh-high and beginning to ripen and turn gold. Red poppies grew throughout the wheat fields and other open areas. Numerous boulders were interspersed throughout the woods, providing natural defense for the German machine gunners who had fortified their positions.

The north-facing position the Marines occupied on Hill 176 was in heavy timber. About 300 meters to the north was another belt of woods, thick with underbrush. Between Hill 176 and Hill 142 lay 300 meters of wheat fields that the Marines would have to cross before reaching their objective. Dense woods covered both sides of the hill. Beyond, the hill sloped down gently to the north with more wheat. Tall pines and hardwood grew on the nose of the hill. A long, curving valley of wheat with tree-lined streams continued to the north.10

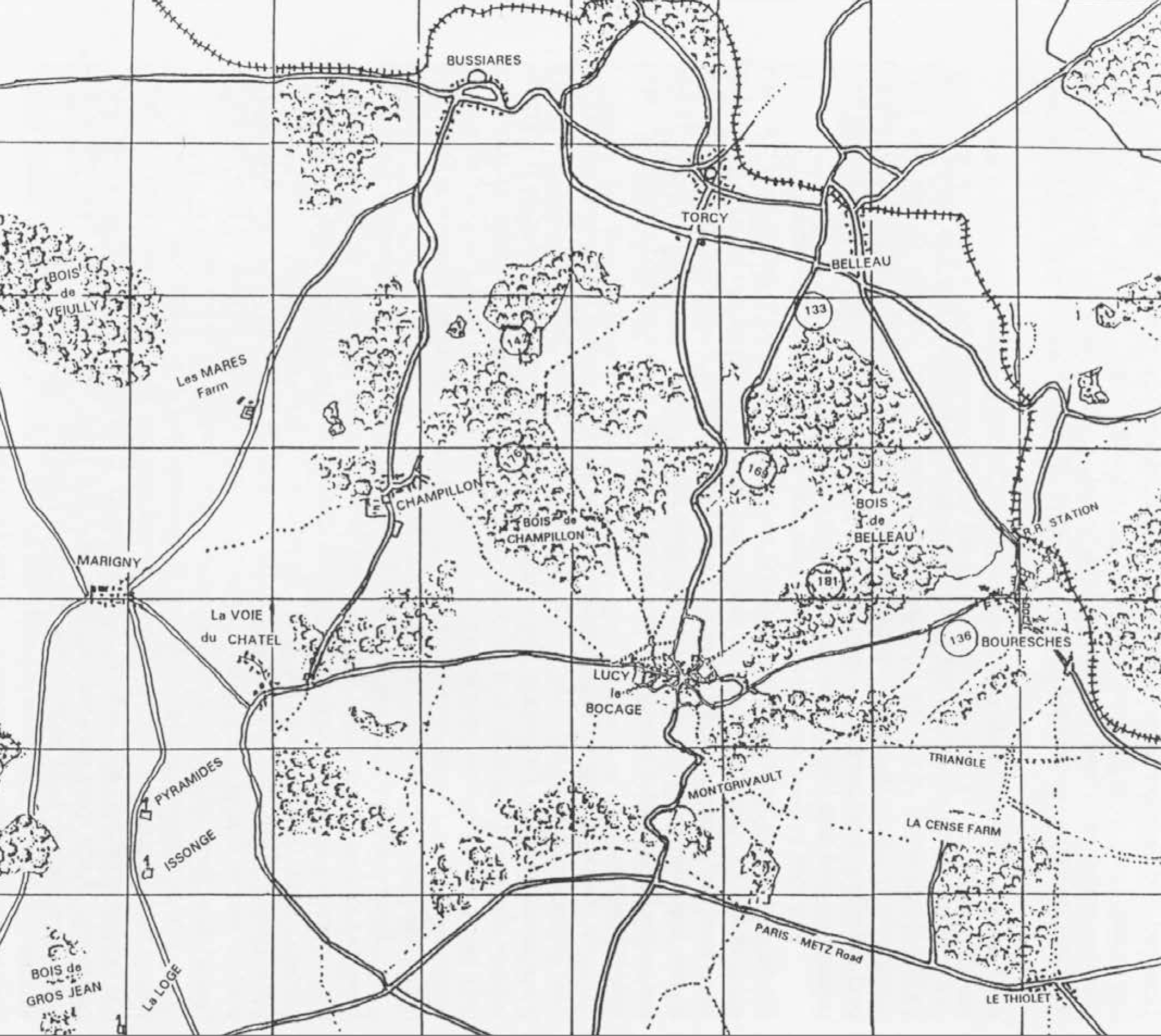

Lying just north of the 1st Battalion’s position on the forward slope of Hill 176, Hill 142 was a 2-km-long tree-covered ridge running roughly north-south with ravines on either side (see map 1). “Hill” was a misnomer; the name was more of an American designation for a series of connected low-lying hills. Contemporary local maps identified it as “Position 142” with brooks running through ravines to either side of Hill 142, but this too was misleading as there was no water in the “brooks.” One brook sprung at Champillon and passed north along the west side of Hill 142, while the other sprung at Bois de Champillon, passing along the east side of Hill 142.11 The east and north sides of the hill were especially steep and covered with boulders and underbrush, making it ideal for defense. To the north of Hill 142 was the town of Torcy, held by the Germans.12

Map 1. Belleau Wood area, June 1918, showing Hill 142 in the upper portion. John W. Thomason Jr., “Second Division Northwest of Chateau Thierry, 1 June–10 July 1918,” unpublished manuscript, 1928, Personal Papers, 1918–1950, Dolph Briscoe Center for American History, University of Texas at Austin

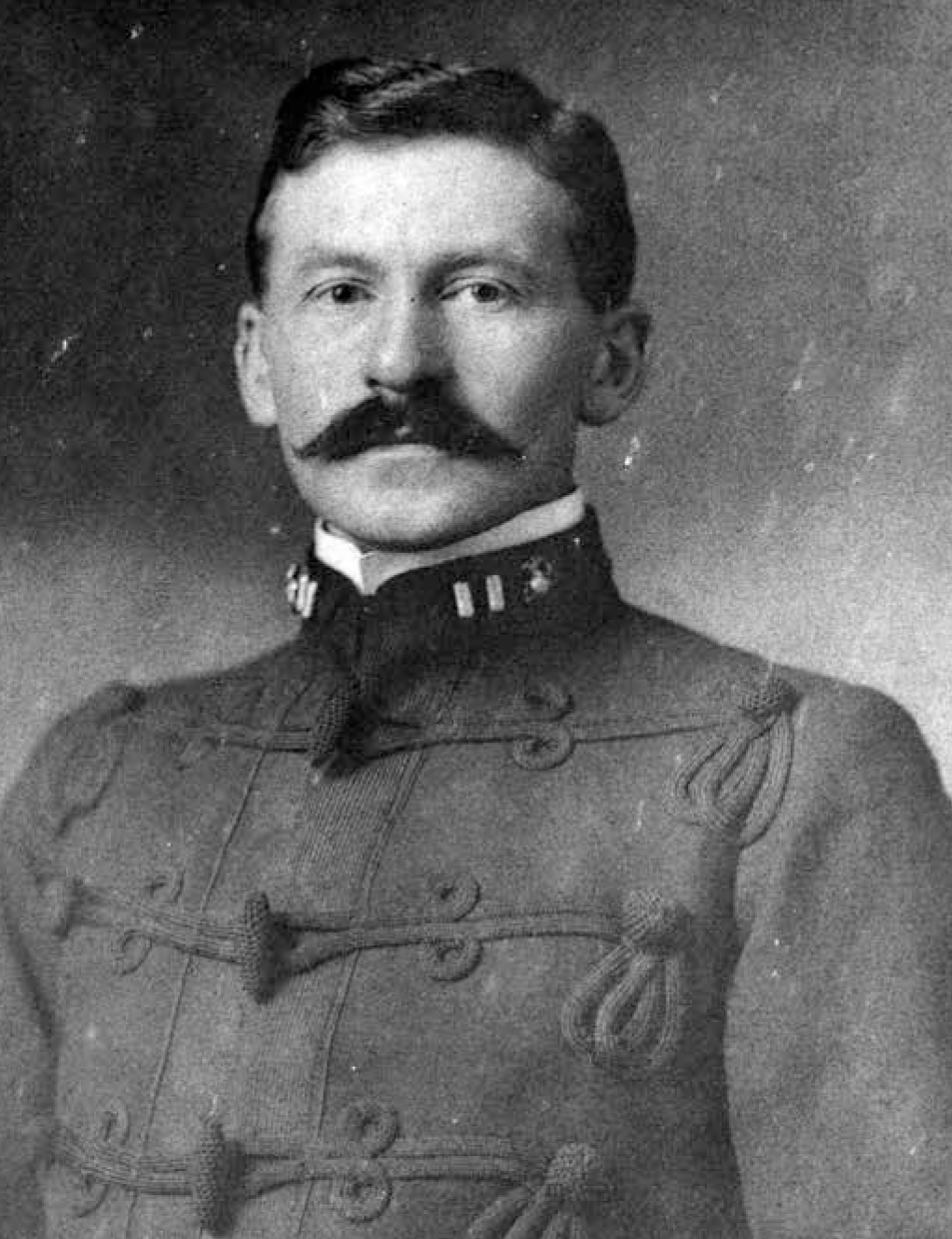

Maj Julius S. Turrill, commanding officer, 1st Battalion, 5th Regiment, shown here photographed as a captain. Historical Reference Branch, Marine Corps History Division

The German Defenders

The German Chemin de Dames offensive began on 27 May 1918 between Soissons and Rheims. The Germans quickly overran the French and were temporarily halted at the Marne River by fresh American troops, in some places only 72.4 km from Paris. The Germans spent the day of 4 June strengthening their positions around Bouresches. Initially facing the 5th Regiment was the 460th Infantry Regiment, while opposite the 6th Regiment was the 461st Infantry Regiment, both of the 237th Division, one of four divisions making up the German IV Reserve Corps. The 197th Division had its 237th Infantry Regiment on the left flank on Hill 142 with two battalions in line and one in support. The 28th Infantry Division was in reserve and would be available to support the regiments of the 237th Infantry Division if needed. On 5 June, the IV Reserve Corps issued orders that all offensive operations were to be suspended.13 This disposition of German forces would prove extremely fortunate for Major Turrill’s battalion, as there was confusion between the 460th Infantry Regiment and the 237th Infantry Regiment as to which stream was the division boundary. In a fortuitous twist of fate for the Marines, Hill 142 appeared to have been the boundary between the 127th and 237th Divisions. As a result, the Germans had a difficult time coordinating their defenses.14 The table of organization for German units specified 850 men per battalion, three battalions of 2,550 men to a regiment, and three regiments comprising an infantry brigade of 7,650 soldiers.15 Defending Hill 142 were four companies of the 460th Infantry Regiment, heavily supported by Maxim machine guns.16 Then-first lieutenant Thomason, himself a member of the 1st Battalion’s 49th Company, described the defenders: “A company of German infantry and a machine gun platoon lay in the three-cornered clump of trees on the forward slopes of Hill 142, in the sector northwest of Chateau-Thierry. By the white piping on their uniforms, they were Prussians, and by the ugly, confident look on them, with a touch of Berlin swank, they were Prussians of a very good division; and there were no better soldiers in the world.”17

At 274.3 meters from where the Marines were to cross the line of departure, across an open wheat field, the 9th Company of the 460th Regiment occupied the first woods extending from the ravine on the east. Beyond that, a heavy machine gun detachment from the 273d Regiment was positioned in a low, thick coppice in woods to the west of the Champillon ravine. In underbrush and tall pines to the left was the 10th Company, 462d Regiment. To the east in a square patch of woods were the 10th and 11th Companies, 460th Regiment, and the 12th Company in reserve north of them.18

Orders to Attack

At approximately 2225 on the night of 5 June 1918, the 4th Brigade issued Brigade Order No. 1 for the next morning’s attack, directing the 1st Battalion, 5th Regiment, supported by the 8th Machine Gun Company (Captain John H. Fay) and 23d Machine Gun Company (Captain George H. Osterhout Jr.), to seize Hill 142, with the attack to commence at sunrise (0345) on a frontage of 800 meters.19 It was after midnight when Colonel Wendell C. Neville, commanding officer of the 5th Regiment, arrived at the 1st Battalion’s command post, located in the basement of the powerhouse in Marigny to issue the order to Turrill.20 In part, that order read

- The enemy holds the general line Bouresches-Bois de Belleau-Torcy-Bussiares- Gandeelu-Chezy-on-Orxios. The French 167 D.I. [Division Infantry] is on the left of this Brigade and attacks June 6th in the direction of the Bussiares Wood.

- The Brigade will attack on the right of the French 167 D.I. Objective from the Little Square Wood 400 Meters S.E. of Calvaire to the brook crossing 174.0–263.4.21

- The attack between the brook of Champillon (inclusive), Hill 142, and the brook which flows from 1 kilometer N.E. of Champillon, inclusive will be made by the 1st Bn., 5th [Regiment], supported by the 8th and 23d Cos. Machine Guns.22

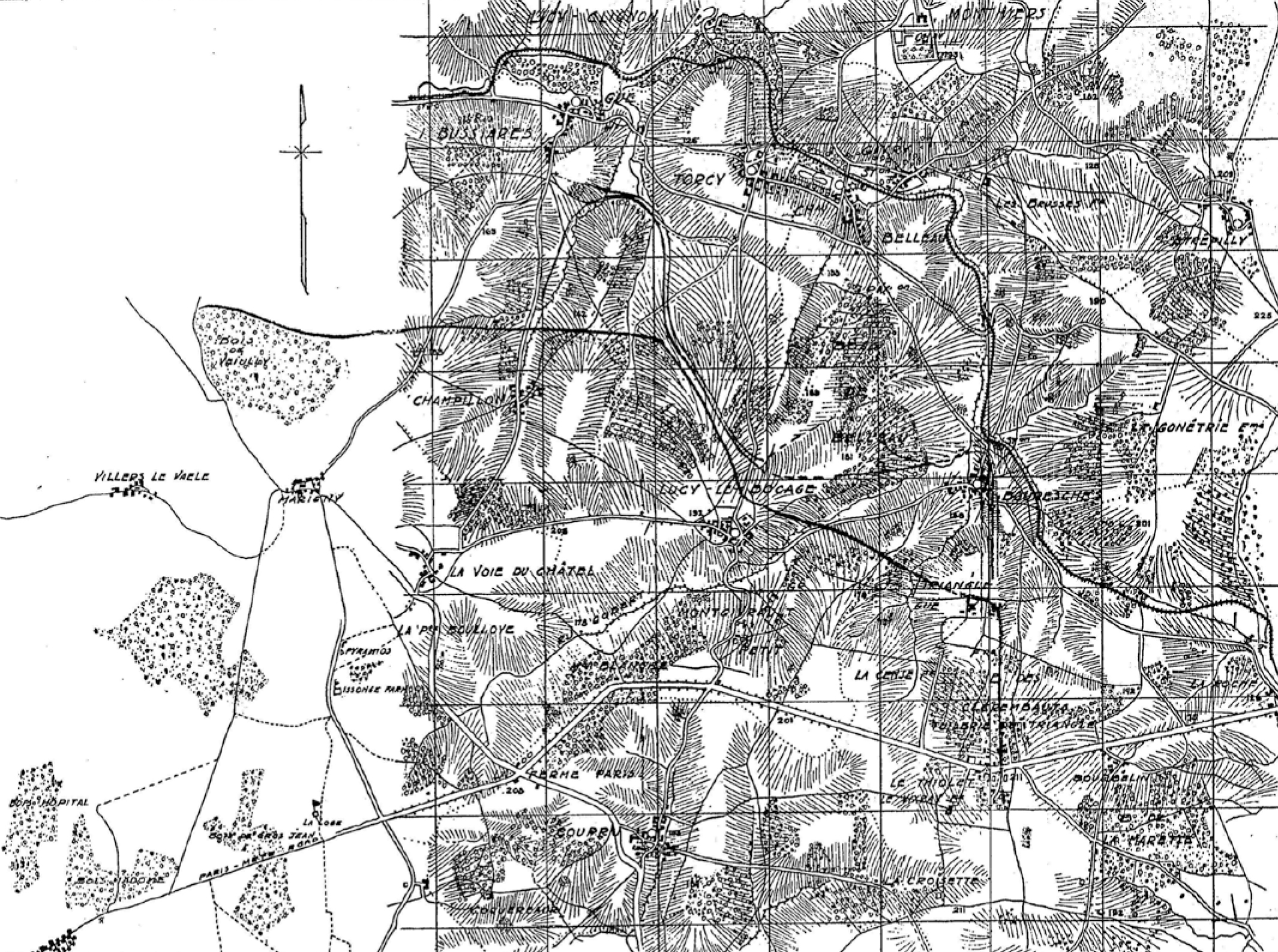

Due to the lateness of the hour, only company commanders Captain George W. Hamilton, 49th Company, and First Lieutenant Orlando C. Crowther, 67th Company, were told of the attack and given a map of the area. Platoon commanders and senior noncommissioned officers (NCOs) were allowed to look at their company commander’s map (map 2).23

Map 2. Hachured map similar to the ones given to Capt George W. Hamilton and 1stLt Orlando C. Crowther early on the morning of 6 June. Reprinted courtesy of the Marine Corps Gazette

French Army units were to be on Turrill’s left flank and Major Benjamin S. Berry’s 3d Battalion, 5th Regiment, on the right flank. The two companies of the battalion conducting the initial assault were forced to travel 3.2 km over unfamiliar ground in the dark to their attack position on Hill 176. Even more concerning to the Marines, there had not been time to bring up hot chow and they had not been fed.24 Holding a position on Hill 176 just south of Hill 142 was Major Berton W. Sibley’s 3d Battalion, 6th Regiment, which had occupied the position since 2 June. At 2100 on 5 June, Major Frank E. Evans, adjutant of the 6th Regiment, sent Sibley a message notifying him that two companies would relieve his battalion “sometime tonight.”25 Hamilton’s 49th Company arrived at its attack position on Hill 176 at 0240 on 6 June and he spent the next 20 minutes searching for the commanding officer of the company from the 3d Battalion, 6th Regiment, he was relieving. It was just getting light and a relief based on doctrine was not possible, so Hamilton told the defenders not to fire at any movement forward of their position. He then moved his company into an open area across from the Germans. He next moved to his left and found the 67th Company had just assumed their attack position at 0345, but there was no sign of the French on their left flank or the 3d Battalion, 5th Regiment, on his right. Hamilton located Second Lieutenant Thomas W. Ashley of the 67th Company’s right platoon, and informed him his company was moving forward.26

Capt George W. Hamilton, commanding officer, 49th Company, 1st Battalion, 5th Regiment Historical Reference Branch, Marine Corps History Division

The Attack

The time designated for the attack, 0345 on 6 June, found the two companies of Major Turrill’s 1st Battalion, 5th Regiment, formed in four waves per company on Hill 176 to the east of Champillon and west of Belleau Wood. In these two companies were 11 officers and 475 enlisted men. The 67th Company’s mission was to sweep down the left side of Hill 142 and into the wheat fields below. The 49th Company was to support the Marines of the 67th Company on their left flank and capture the crest of the hill and the road below it. Though not tasked in the brigade order, the 15th Machine Gun Company (6th Machine Gun Battalion) was positioned in Champillon and ready to provide support. Their fire had a telling effect on the 10th and 11th Companies of the 460th Regiment. The battalion’s other two companies, the 17th (Captain Roswell C. Winans) and 66th (First Lieutenant Walter T. H. Galliford), and the 8th Machine Gun Company were in defensive positions at Les Mares Farm awaiting relief by French troops before they would rejoin their parent battalion.27

Major Turrill arrived at the attack position shortly before 0345 from Champillon. He made a significant command decision when he commenced the attack on schedule with two rifle companies supported by one machine gun company rather than asking to post-pone the attack until the arrival of his whole battalion. American artillery had been firing on the German positions and assembly areas since 0315, and while not knowing the exact trace of the German positions, the barrage was effective in suppressing them.28 Dawn was just beginning to break when the two companies moved north from their positions on Hill 176 into a wheat field. Their initial objective, on the other side of the wheat field, was a copse of trees on the top of Hill 142 occupied by German infantry, heavily supported by machine guns.

The Germans began firing on the Marines after only 18.3 meters. The Marines advanced through the first wheat field, guiding center, and although encountering stiff resistance, quickly overran the 9th Company. The 9th Company sent up a red rocket—the signal for the German artillery to fire a barrage. On the left, the 67th Company came under fire from the Maxim machine guns in the Champillon ravine and suffered heavily in officer and NCO casualties. The 49th Company soon overran the 10th Company, 462d Regiment, as it moved down the hill, but immediately took fire from the 10th and 11th Companies of the 460th Regiment in the square woods.29 The 49th Company went through the square woods, but most of the two German companies were bypassed, effectively isolating them.30

While training under French troops at Bourmont, the Marines had been taught to attack in four waves. These tactics were a holdover from Napoleonic warfare, which theorized that two or three of the front ranks would be cut down in the assault, allowing the fourth rank to capture the objective. The Marines also were taught to go to the ground when taking heavy automatic fire and to respond with automatic weapons and hand grenades. Hamilton commented, “I saw immediately that such tactics would not do in this case. They might work against one nest, or two, but here was a nest broader than our battalion front and containing more machine guns than we had automatics. (No heavy machine guns attacked with us, and none joined us until several hours later.)”31

The Germans could not miss the Marines advancing on them in dawn’s light with the first rays of the sun shining on them. At this point, the Marines began to suffer heavy casualties and, according to doctrine, the second line moved into the first line and the fourth line moved into the third line. Shortly after that, casualties became so heavy that the Marines went to ground and advanced as best they could. Captain Hamilton later wrote that the Marines “hadn’t moved fifty yards when they cut loose at us from the woods ahead—more machine guns than I had ever heard before. Our men had been trained on a special method of getting out machine guns, and, according to their training, all immediately lay flat.”32

First Lieutenant Jonas H. Platt, 49th Company, described the initial advance: Across the fields we raced, banging down the boches as we went, and into the woods. Machine guns rattled and men dropped. There we started to form again, while I tried to count my men. Suddenly a machine gun far ahead opened up spitefully I crawled a bit ahead to see what was happening. ... There, grouped about a captured German machine gun, were ten of my missing men having the time of their lives, banging away with this captured gun at anything that looked like a boche.33

Turrill remained in his position watching the fourth wave move forward when First Lieutenant Gilfillan and his platoon of the 66th Company arrived at 0430. Turrill sent them forward and then established his post of command on the north edge of the woods on Hill 176. At about 0515, the remainder of the 66th Company arrived and were committed to the action. The 8th Machine Gun Company arrived next and provided support to the attack. Company D, 2d Battalion, 2d Engineers, came up at 0530 and was initially put into the line as infantry to help repel German counterattacks and then were used to help fortify the position on Hill 142. Captain Winans and the 17th Company arrived at 0537 and were commit- ted to the right of Hamilton’s 49th Company. Unfortunately, the 23d Machine Gun Company would not arrive until the afternoon, too late to support the attack.34 Captain Keller E. Rockey, the battalion adjutant, reported to brigade that things were going well.35 At 0537, Captain Rockey reported to Colonel Wendell Neville at 5th Regiment, “17th Co. going into deployment from old first line [Hill 176]-8th M G [Machine Gun] Co. already forward. Things seem to be going well—No engineers are in evidence—Can something be done to hurry them along—The advance is about one kilometer. Major Turrill up forward with the line.”36 Among the first killed was Second Lieutenant Walter D. Frazier of the 49th Company. He was posthumously awarded the Distinguished Service Cross, Navy Cross, Silver Star, and Croix de Guerre for “extraordinary heroism.”37

The waves of Marines were moving forward when a German artillery shell exploded within their ranks and a man cried out. One of the young Marines of the 67th Company called out, “Hey, Pop, [First Sergeant Hunter] there’s a man hit over here!” Hunter’s reply was immediate and terse: “C’mon, goddamnit! He ain’t the last man who’s gonna be hit today.”38 Moving forward across the wheat field, Hunter was hit twice, and twice he regained his feet and continued to advance.39

Early in the fight, First Lieutenant Orlando Crowther, commanding officer of the 67th Company, also was hit twice; the second wound proved fatal. He had made it across the wheat field to the first woods and had taken out one machine gun crew and was in the process of attacking a second machine gun position when he was shot in the throat and killed instantly.40 Crowther was not alone; eight other Marines were killed in the attempt to silence the gun. For his actions, Crowther was awarded the Distinguished Service Cross and the Navy Cross.41 After Crowther fell, remaining Marines led by Corporal Prentice S. Geer charged with bayonets and captured the machine gun. One of the Marines grabbed the muzzle of the gun and pushed it over, losing his hand in the process. They repelled a counterattack. Geer was awarded the Distinguished Service Cross, Navy Cross, and Silver Star; he was commissioned as a second lieutenant in July.42 Lieutenant Colonel Logan Feland, second in command of the 5th Regiment, went forward to take charge of the attack. At 0600, he requested support for the left flank of the 67th Company because the French had not yet moved up and the American flank was open. Colonel Neville deployed the 51st Company of the 2d Battalion, 5th Regiment—the brigade reserve—initially to Champillon; it then moved up the Champillon ravine and formed a right angle to the 67th Company. Machine guns were brought forward to provide support to the position.43

At 0430, the German 273d Regiment had reported that it was under attack and both flanks were giving ground, but that the center was holding. After the Marines swept over Hill 142 and continued north, the 12th Company, 460th Infantry, conducted a local counterattack. The regiment requested reinforcements and the 25th Jaeger Battalion of the 7th Saxon Regiment, the brigade reserve, was committed to action. The Americans did not record the time, but German records indicate this action was over by 0600.44

Initially, the Germans thought they could hold the line, but at 0610 the 273d Infantry Regiment request- ed artillery on its old position, and fire fell on Hill 142. At 0715, the 273d Infantry reported that it had been assaulted by a brigade of American troops, and at 0810, the infantry brigade of the 197th Division reported to the 237th Division that it was being attacked by French, American, and British troops.45

The attack stalled at this point, but the “old breed,” in the presence of Captain Hamilton and senior NCOs, carried the day. They moved up and down the lines, getting men to move forward and, in some cases, actually kicking them to their feet. Although the Germans on the southern edge of Hill 142 had been routed, some of the Marines were dazed and dis- oriented and hesitated to seize the advantage. Hamilton gathered five or six NCOs and told them, “Here is our direction. We go about a mile farther. When you come to a road, just over the nose of the hill, halt and dig in.” Yelling at the top of his lungs, Hamilton ran the length of the line, urging his men forward telling them, “We had ’em on the run.”46

It was also at this point that the Marine Corps investment in marksmanship paid off. Marines were inflicting casualties on the Germans with individual rifle shots at 274.3 meters. Private Walter H. Smith of the 49th Company wrote, “Then it became a matter of shooting at mere human targets. We fixed our rifle sights at 300 yards [274.3 meters] and aiming through the peep kept picking off the Germans. And a man went down at nearly every shot.”47 As they closed on the German positions, rifle shots were replaced with bayonets and rifle butts, and the Germans suffered extensive casualties.

The Marines of the 67th and 49th Companies surged forward through the wheat and went over Hill 142 before occupying positions on the hill’s forward slope about 0700. The 67th Company quickly overlapped and swept through the German 9th Company on its left. Unexpected support came from the 10 machine guns of Captain Matthew H. Kingman’s 15th Machine Gun Company of the 6th Machine Gun Battalion, described as “ten guns from the 15th Company, which obtained excellent overhead fire on enemy reserves and assembly points. When objective was reached the guns took up new positions to conform to the line established.”48

At 0630, Captain Rockey had again reported to brigade that all was going well, and at 0710 he reported to division that all objectives had been taken and the position was being consolidated. Without a doubt, Hamilton was the key to the Marines’ success that day. As the Marine attack got bogged down, he moved up and down the line, urging individual Marines to their feet and moving forward again. As his company moved through the woods, he sent prisoners to the rear, and at one point took an Iron Cross off of a German officer. The Germans began to withdraw and the Marines fired on them as they fled. The 49th Company moved through the first copse of trees and came on another wheat field full of red poppies. Once again, the Marines had to rush across the open wheat field to the next line of trees defended by German infantry supported by machine guns. Hamilton commented that by every machine gun there was a dead gunner, and it was only by rushing the guns the Marines were able to take them as there were too many guns with mutually supporting fire.49 The two assault companies moved up the northern edge of Hill 142. The 67th Company halted at that point, while Hamilton continued to move to the northeast, possibly to seize the square woods northeast of Hill 142. Before the Germans halted his forward movement, three of his Marines actually entered the village of Torcy, announcing they held the town but needed immediate reinforcements. The remainder of Hamilton’s company made it as far as the square woods between Hill 142 and Torcy before being forced to fall back to Hill 142.50

Platt and his men charged again, crossed another wheat field, and entered another wood holding many dead Germans. Platt’s men halted their advance momentarily to collect souvenirs until he moved them forward again. During this third rush, Platt tripped and fell behind his advancing Marines. When he caught up with them, they had stopped in yet another wood and were in groups of twos and threes.51

Gradually rounding up his platoon, Platt moved to evaluate the situation. He ran into a first sergeant (who he later identified only as “Chuck” but who must have been First Sergeant Hunter, as the 67th Company was on the left of Platt’s 49th Company) and 20 Marines from the company on his left.52 When Platt asked Hunter where his company commander was, Hunter responded that it was him; the rest of the Marines in the company were dead. Hunter also told Platt that he was going after the Germans, an idea that Platt tried to talk Hunter out of executing Hunter promised he would not move forward and Platt went to look for Captain Hamilton.53 Sometime later, Hunter was hit a third time and was killed in action that morning. Hunter would be awarded the Distinguished Service Cross, Navy Cross, and Silver Star “for extraordinary heroism in action. He fearlessly exposed himself and encouraged all men near him, although he himself was wounded three times.”54 Having reached the bottom of the hill, Hamilton looked for the road he thought was his objective. Upon reaching a road, Hamilton began to reconsider his objective when he received fire from his flanks and rear. He studied his map and found that he had advanced a half mile too far. Seeing a large number of Germans in the town of Bussiares to the northwest and fearing death or capture, Hamilton ordered his men to return to Hill 142. On the return up the hill, Hamilton ran into First Lieutenant Platt with about a platoon of men and sent him back up Hill 142. On the way back to the crest of Hill 142, Platt and his men successfully broke up a German counterattack and took out several machine gun nests, but Platt sustained a serious leg wound.55 Platt continued to direct his platoon. He charged and drove off a German ma-chine gun crew and supervised the establishment of a defensive position before being evacuated. He was awarded the Distinguished Service Cross, Navy Cross, and Silver Star for his actions.56

Hamilton’s company continued through the second wood—his actual objective and where he should have halted his men. However, he was looking for an unimproved road that was on his map. At this point, the Germans were retreating rapidly, so Hamilton continued down the nose of Hill 142 in search of the road with one platoon. Moving north and entering open ground at the base of Hill 142, Maxim machine guns opened up on the Marines from both flanks. As Hamilton continued to move north with an automatic rifle team, most of the platoon veered to the left to take out a German machine gun nest.

About that time, Hamilton spotted a road to his front with a good bank to offer protection, but he had overrun his objective and was just a few hundred meters short of the town of Bussiares to the left front. Most of the Germans had retreated at this point, but one company was forming for a counterattack when Hamilton realized he was too far forward. He soon sent his Marines back with the intent to occupy the nose of the hill and reorganize and dig in.

Hamilton went back up the hill in “a drainage ditch filled with cold water and shiny reeds. Machine gun bullets were just grazing my back and our own artillery was dropping close.” He finally occupied his objective and reorganized the 49th Company as well as the leaderless 67th Company. Hamilton then sent Marines to link up with French forces on his left and the 3d Battalion, 5th Regiment, on his right, but he could not make satisfactory liaison until the next day.57

Upon arriving back on Hill 142, Hamilton discovered that the 67th Company had lost four out of five officers, including its commanding officer, First Lieutenant Crowther, while the 49th Company had only Hamilton. Hamilton assumed command of both companies and established a defensive position, which was completed about noon.58 By 0800, the French 167th Division had belatedly started moving forward.59

Captain Winans sent a message to battalion stating that his 17th Company was to the right of Hamilton but there was nothing to his left and the Germans were working around that flank. In response, Winans sent “10 then 20 men to help and protect his flank.” He encouraged battalion to “get something in to plug the hole on our left.” He also reported: “We don’t know whether there are Marines on our right. Can’t establish liaison to right or left yet. . . . We have a good position but can’t extend anymore.” He then notes “Hamilton is o.k.”60

At 1045, the French liaison incorrectly sent word that the Americans had more than 300 prisoners. Eventually, 1 officer and 15 enlisted captives were sent to the rear.61 Although the 23d Machine Gun Company did not arrive in time to support the assault, six guns of the 81st Machine Gun Company were ordered to Hill 142 to support the 1st Battalion. The Germans attacked the consolidated position on Hill 142 on several occasions but were repulsed. At 1310, Turrill reported the French advancing on his left flank and the immediate threat of attack from that flank was over.62 The Germans had taken a beating at the hands of the untried Americans, and they knew it. The Americans struck the 1st Battalion, 460th Infantry, and practically annihilated the 9th Company of that battalion, although a few members of that company had fought their way out of the encirclement with bayonets. The 10th and 11th Companies had dug into a patch of woods southwest of Torcy. The two German companies beat back Hamilton’s attack and were soon joined by the 12th Company, and these units held until nightfall.63

At 0840 on 6 June, Brigadier General James Harbord sent the following message to the commanding general of the 2d Division:

The French did not relieve elements on the left of my line until 3.00 a.m. this morning instead of 9 o’clock last night as expected. Our attack between brooks on either side of Hill 142 started with two companies and half a machine gun company on the front line. At 6.30 our line was considerable distance ahead of the French and had to be halted to wait for them. At 7.01 a.m. report was received that both 1st and 3d battalions of the 5th Regiment had reached their objectives. There had been some heavy shell fire, rifle and machine gun fire. Several men killed and quite a number wounded. Figures as to casualties will be hurried as soon as received. Sixteen prisoners, including one officer, were reported captured by 5.50 a.m. At 7.10 reported that our position was being consolidated as rapidly as possible and that our front line had thrown out strong posts in front of the position.64

At 0950, Captain Hamilton sent what was probably the most succinct report of the battle to battalion:

Elements of this Company [49th] and the 67th Company reached their objective, but because very much disorganized were forced to retire to our present position which is on the nose of Hill 142 and about 400 yds. [365.8 meters] N. E. of square woods. Our position not very good because of salient. We are intrenching [sic] and have four machine guns in place. We have been counter-attacked several times but so far have held the hill. Our casualties are very heavy. We need medical aide badly, cannot locate any hospital apprentices and need many. We need artillery assistance to hold this line tonight. Ammunition of all kinds is needed. The line is being held by detachments from the 49th, 66th, and 67th Company & are very much mixed together. George W. Hamilton65

On the right flank, Captain Hamilton led his company and consolidated its gains with the remainder of the 67th Company, which had lost all but one of its officers. For his leadership, he was awarded the Distinguished Service Cross, the Navy Cross, the Silver Star, and the Croix de Guerre.66

Valley below Belleau Wood on way to Vaux road; Lucy-le-Bocage in background. Historical Reference Branch, Marine Corps History Division

German Counterattacks

Throughout the remainder of the day, the Germans launched at least five major counterattacks against the Marines’ newly established position. The first, conducted by the 12th Company, 460th Infantry, and the 26th Jaeger Battalion, occurred as the 49th Company withdrew from their advance position back to their objective on Hill 142.67

The 26th Jaeger Battalion was sent forward to close the gap left by the 2d Battalion, 237th Infantry Division, but the counterattack failed to dislodge the Marines from the hill. The 237th Infantry Division was ordered to retake all lost ground at any cost, but spent the remainder of the day in futile attempts to dislodge the Marines. Attacks continued by numerous German units through the remainder of the day, but none penetrated the Marines’ lines. The 197th Division had lost about 2,000 casualties during the period 4–6 June and the 273d Regiment reported the loss of 13 officers and 405 men on 6 June.68 Hamilton described these counterattacks:

And now came the counter-attacks—five nasty ones that came near driving us off the hill—but—we hung on. One especially came near getting me. There were heavy bushes all over the hill, and the first thing I knew hand grenades began dropping near. One grenade threw a rock which caught me be- hind the ear and made me dizzy for a few minutes.69

While consolidating their position during one of these German counterattacks, Captain Hamilton discovered a line of about 15 Germans and five light machine guns setting up about 18.3 meters from the Marine line. Gunnery Sergeant Ernest A. Janson (who went by the name Charles F. Hoffman at the time) moved forward, screaming and firing his rifle, and in the process took on the Germans; after several minutes of strenuous hand-to-hand fighting, he killed several and routed the remaining Germans. Janson was awarded the Medal of Honor, Silver Star, and Croix de Guerre for his actions.70 At 1310, Turrill sent a message to regiment notifying them that the French had come up and occupied positions on his left flank, thereby helping to alleviate some of the pressure the battalion was experiencing.71 Around midnight, the Marine positions on Hill 142 were consolidated and a defense was established. The square woods to the northeast were not occupied, but it was untenable to either side and the road running in front of the hill was covered by Marine rifles. At 0400 on 7 June, the 45th Company of the 3d Battalion, 5th Regiment, came up on the right flank and the defensive situation was somewhat stabilized.

The 9th Company, 462d Regiment, and the 9th Company, 460th Regiment, had both been practically annihilated. A vigorous counterattack was launched by the 12th Company, 460th Infantry, but was stalled when its commander fell. The regimental commander, Lieutenant Colonel Friederich Tismer, decided further attacks would produce severe casualties and ordered a withdrawal. Accordingly, during the night, the German 10th and 11th Companies withdrew to Torcy, taking their wounded with them. The 1st Battalion, 5th Regiment, were in sole possession of Hill 142. The old breed’s leadership had carried the day, but at a catastrophic cost in killed and wounded.72

Hamilton summarized the seizing of Hill 142 and the work of Turrill’s understrength battalion:

After the counter-attacks we settled down to the work of digging in. Gee, it was a long day! The night proved to be worse, and on account of my flanks I was more worried than I cared to admit. The Boches went up the valleys to our right and left and from their flares I thought we were all but surrounded. Two more companies had come up [17th and 66th], however, and the fire from the rifles and auto-rifles of several hundred men must have made the Germans nervous, too, for about dawn they went back and only left several machine guns to worry us during the next day.73

In the end, Major Julius Turrill led his two understrength companies to seize Hill 142, overwhelming the remaining German defenders and driving them off the high ground. He was awarded the Distinguished Service Cross, Navy Cross, two Silver Stars, and Croix de Guerre for extraordinary heroism in leading his command under heavy enemy fire.74 The battalion adjutant, Captain Rockey, was also awarded the Distinguished Service Cross, Navy Cross, and Silver Star for extraordinary heroism in carrying forward the attack and organizing and holding the position.75 Late that night, Rockey sent a message to Hamilton: “The rations sent to you tonight are for all companies. . . our ration truck was struck by a shell and rations are scattered all over the county. This is the best we can do tonight.”76

The battalion’s casualties were horrendous; one source set the number of 1st Battalion’s killed, wounded, and missing at 14 officers and 318 enlisted men.77 Sometime on 7 or 8 June, Turrill’s battalion received a group of replacements, but they could in no way replace the experience of those who were killed in the attack on Hill 142. The Old Breed no longer existed. Additionally, the 8th Machine Gun Company lost 10 men and the 51st Company from the 2d Battalion reported 1 officer and 45 men were casualties. The 45th Company of the 3d Battalion that had come up to support the 1st Battalion’s right flank suffered 2 officers and 71 men as casualties.78

Consequently, Thursday, 6 June 1918, was the most catastrophic day in Marine Corps history up to that point, with the 4th Brigade suffering 31 officer and 1,056 enlisted casualties. As many casualties were suffered on that single day as in the Corps’ preceding 143 years of existence.79 When Major Frederic Wise’s wife asked him “How are the Marines?” he replied, “There aren’t any more Marines.”80

Conclusion

The capture of Hill 142 and subsequent battle for Belleau Wood have gone down as a defining moment in the annals of Marine Corps history. The battalion would continue to fight for the possession of Belleau Wood with the other units of the 4th Brigade until 26 June, when Major Maurice E. Shearer, commanding officer of 3d Battalion, 5th Regiment, would send the message “Belleau Woods Now U.S. Marines Entirely.”81 Though the Marines suffered heavily in their first pitched battle, the Germans suffered far worse. A few days after the capture of Hill 142, an unmailed letter was found on the body of a dead German. Intended to be sent to his father, the letter said, “The Americans are savages. They kill everything that moves.”82

In a report dated 17 August 1918, General Richard von Conta, commanding the 4th Reserve Corps that faced the Marine brigade, wrote:

Fighting Value: the 2d American [Division] may be described as a very good division, and, might even be considered as being fit for shock troops. The numerous attacks by the two Marine regiments at Belleau Woods were executed vigorously and without regard for the consequences. Our fire did not affect their morale sufficiently to interfere appreciably with their advance; their nerves had not yet been used up. In spirit the troops are lively and full of grim, but good-natured, confidence. Indicative is the expression of a prisoner “We kill or get killed.”83

It was the “old breed of American regular” embodied by Major Julius Turrill, Captain George Hamilton, First Lieutenant Orlando Crowther, First Sergeant Daniel Hunter, and Gunnery Sergeant Janson who—along with others like them—not only carried the day at Belleau Wood, but also “transmitted their temper and character and view-point to the high-hearted volunteer mass which filled the ranks of the Marine Brigade.” And in that they found victory; not only on Hill 142 and Belleau Wood, but also at Soissons, Saint-Mihiel, Blanc Mont, and the Argonne Forest and in crossing the Meuse River on the last night of the war.84

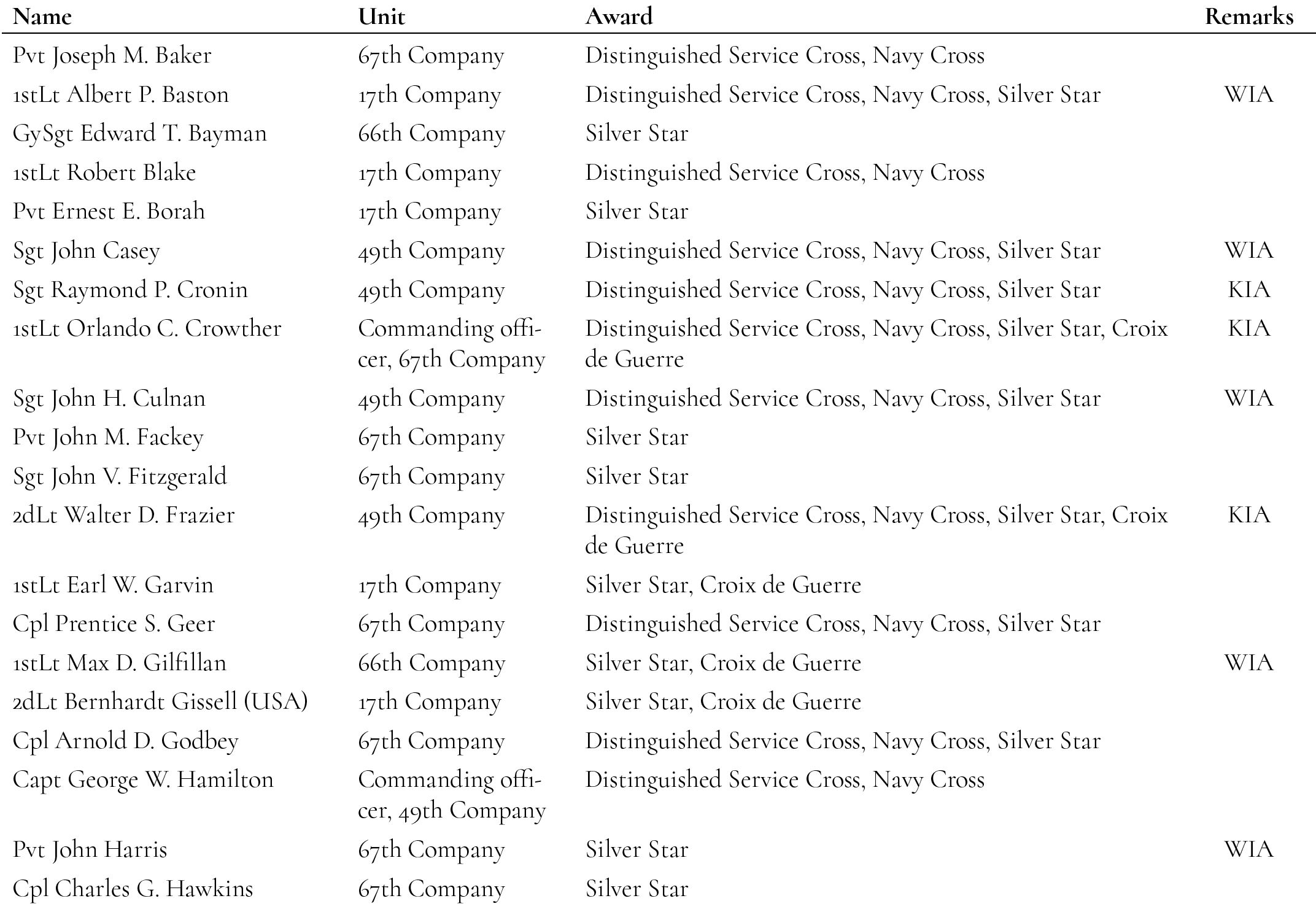

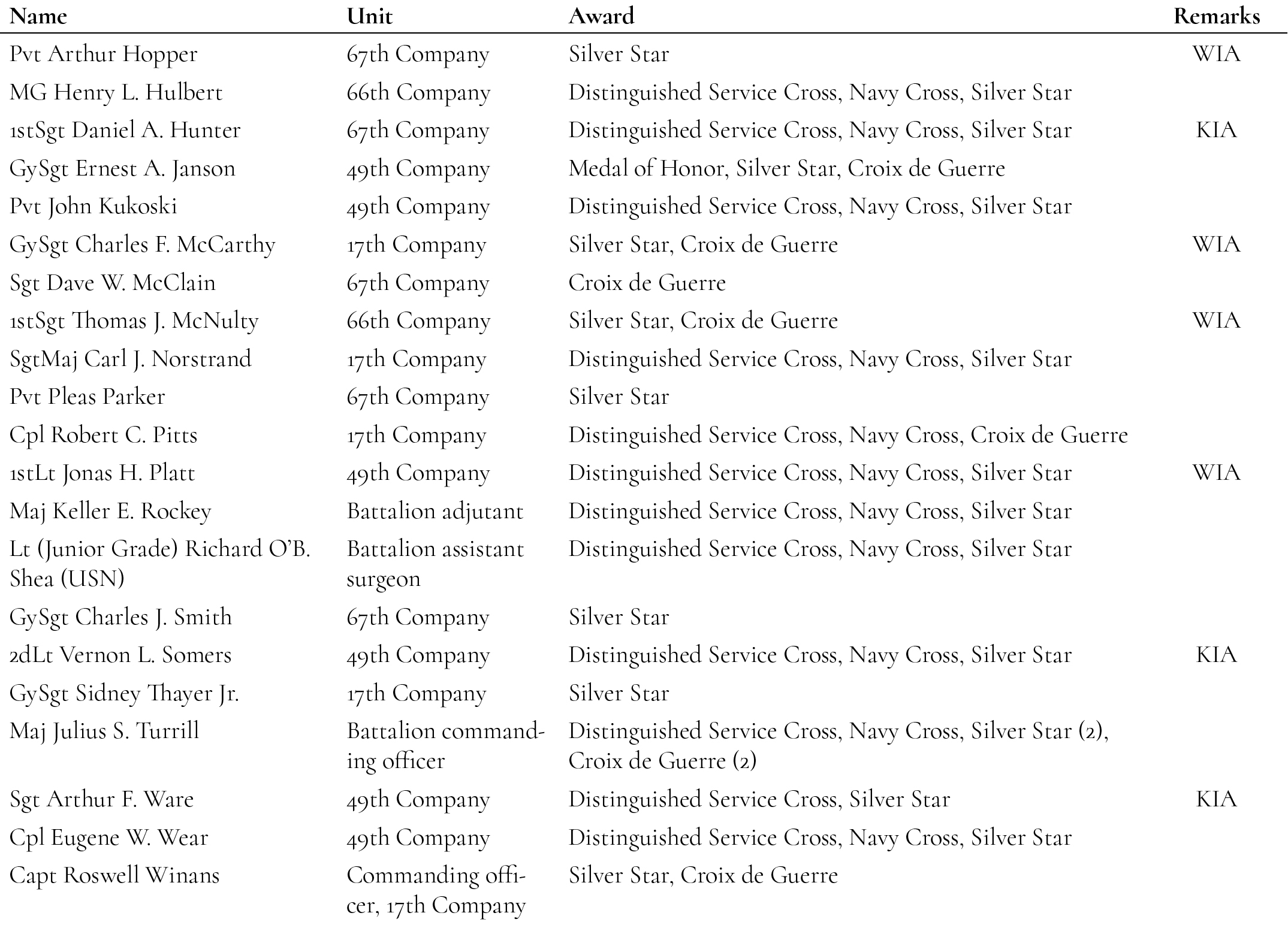

Table 2. Awards for 1st Battalion, 5th Regiment’s attack on Hill 142, 6 June 1918

Reference Branch, History Division

Epilogue: “That’s ‘Pop’ Hunter”

Major Turrill sent a message to the 5th Regiment at 0725 on 7 June requesting that the battalion’s dead be buried at Champillon and notifying the regiment he would send his dead to that town.85 However, the remains of those Marines killed in action were initially interred in Cemetery 29 on the road leading from Hill 142 to Torcy. Replacements were brought forward to replenish the depleted Marine ranks. One of the replacements’ jobs was to bury the dead. Author George B. Clark relates how an old-timer passing by stopped to watch the burial detail and occasionally would salute a body. One of those brought in for burial was dressed in the forest green uniform of the Marines with a first sergeant’s chevrons and seven hashmarks for seven enlistments. Dangling from his neck was a whistle and his pistol flap was unhooked. The old-timer, taking note of the dead man, saluted sharply, turned to one of the new Marines burying the casualities, and said, “Get a blanket, soldier. Wrap him up proper. That’s ‘Pop’ [Daniel] Hunter.”86

Perhaps Private Elton Mackin of the 67th Company wrote a fitting tribute to First Sergeant Hunter and the 1st Battalion, 5th Regiment’s legacy on Hill 142: “Little crosses stand above the dead. They do not tell how men died. They hide the bitter human stories of the war. They seldom stand alone. Men see to that.”87

•1775•

Endnotes

- The quote in this piece’s title is from LtCol Ernst Otto, German Army (Ret), “The Battles for the Possession of Belleau Woods, June 1918,” Proceedings (U.S. Naval Institute Press) 54, no. 11 (November 1928): 941. Maj Gary Wayne Cozzens, USMCR, passed away on 31 July 2018. Major assistance for this article was provided by the late George B. Clark, Col Walt Ford (Ret), LtCol Pete Owen (Ret), and Angela Anderson. For more about Cozzens, see p. 75.

- Elton E. Mackin, Suddenly We Didn’t Want to Die: Memoirs of a World War I Marine (Novato, CA; Presidio Press, 1993), 17; Dick Camp, The Devil Dogs at Belleau Wood: U.S. Marines in World War I (Minneapolis, MN: Zenith Press, 2008), 75; and George B. Clark, Devil Dogs: Fighting Marines of World War I (Novato, CA: Presidio Press, 1999), 102. Clark’s Devil Dogs is considered by many to be the best single-volume history of the Marines in World War I.

- Otto, “The Battles for the Possession of Belleau Woods, June 1918,” 941.

- David C. Homsher, “Securing the Flanks,” Marine Corps Gazette 90, no. 11 (November 2006): 82.

- Capt John W. Thomason Jr., Fix Bayonets! (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1926), x–xiii. This book is considered by many to be the finest fictional book written about the Marines in World War I. Though classified as fiction, it is thinly veiled fiction and, in many cases, Thomason uses actual names of the Marines of the 49th Company. The first chapter, “Battle-Sight,” is the story of the attack on Hill 142. Thomason was not an original member of the 49th Company that began the assault on 6 June. Research by the late George B. Clark indicates that Thomason arrived with replacement troops on 7 June. See John W. Thomason Jr., The United States Army Second Division Northwest of Chateau Thierry in World War I, ed. George B. Clark (Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 2006); and John W. Thomason Jr., “Second Division Northwest of Chateau Thierry, June 1–July 10, 1918,” unpublished manuscript, 1928, Personal Papers, 1918–1950, Dolph Briscoe Center for American History, University of Texas at Austin, 223n807. The former is perhaps the most accurate book written about the battle of Belleau Wood, yet it was not published until 2006. Thomason wrote the report in the 1920s, but quit in frustration after several of the high-ranking officers involved in the battle tried to sanitize his account.

- Hulbert was later killed in action at Blanc Mont on 4 October 1918.

- Cukela later received the Medal of Honor for actions at Sois- sons on 18 July 1918.

- George B. Clark, The Fourth Marine Brigade in World War I: Bat- talion Histories Based on Official Documents (Jefferson, NC: McFar- land, 2015), 26–28, 32.

- Clark, The Fourth Marine Brigade in World War I, 30–32.

- Thomason, The United States Army Second Division Northwest of Chateau Thierry in World War I, 81–82.

- Thomason, The United States Army Second Division Northwest of Chateau Thierry in World War I, 74.

- Homsher, “Securing the Flanks,” 88.

- Otto, “The Battles for the Possession of Belleau Woods, June 1918,” 943; and Thomason, The United States Army Second Division Northwest of Chateau Thierry in World War I, 89–90.

- Thomason, The United States Army Second Division Northwest of Chateau Thierry in World War I, 74.

- Thomason, The United States Army Second Division Northwest of Chateau Thierry in World War I, 76.

- Clark, Devil Dogs, 102. The self-powered, water-cooled machine gun was designed by American inventor Hiram S. Maxim in 1884; it fired at a rate of up to 600 rounds per minute. In 1887, it was introduced to the German Army, which quickly developed its own version of the Maxim machine gun and manufactured 12,000 of them by the beginning of World War I in August 1914. “How the Machine Gun Changed Combat during World War I,” Norwich University online, accessed 19 November 2018; and Paul Cornish, “Machine Gun,” International Encyclopedia of the First World War, accessed 19 November 2018.

- Col John W. Thomason Jr., . . . and a Few Marines (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1943), 475. Though a fictional short story, Thomason describes the attack on Hill 142. The actual German defenders might not have been Prussian. Swank is defined as ostentation or arrogance of dress or manner; swagger.

- Thomason, The United States Army Second Division Northwest of Chateau Thierry in World War I, 84; and Otto, “The Battles for the Possession of Belleau Woods, June 1918,” 944.

- Times are confusing, even in source documents. Located in northern France, the sun would rise on Hill 142 at about 0348. See National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration Sunrise/ Sunset Calculator, accessed 28 December 2017. The Allies used Western European Time, while the Germans used Central Euro- pean Time, which was one hour ahead of the Allies. Both sides used daylight savings time. Otto, “The Battles for the Possession of Belleau Woods, June 1918,” 942.

- Capt George W. Hamilton letter to Commandant of the Marine Corps, 19 November 1919, quoted in Mark Mortensen, George W. Hamilton, USMC: America’s Greatest World War I Hero (Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 2011), 210.

- The map used by U.S. forces in this attack was Chateau-Thierry Sector, June 6–July 16, 1918, at 1/20,000 scale. Summary of Operations in the World War (Washington, DC: U.S. Army Map Service, 1944).

- Field Orders No. 1, 4th Brigade, June 5, 10:25 p.m., as cited in 2d Division, Summary of Operations in the World War (Washington, DC: American Battle Monuments Commission, 1944), 11, 102.

- The map referred to was the old Meaux-50,000 hachured map produced by Depot de la Guerre in 1832 and corrected in 1912. It was almost worthless. Hachure refers to the short lines used for shading and showing surfaces in relief and in the direction of the slope. Thomason, The United States Army Second Division North- west of Chateau Thierry in World War I, 81.

- Mortensen, George W. Hamilton, USMC, 210; and Clark, The Fourth Marine Brigade in World War I, 32.

- Clark, The Fourth Marine Brigade in World War I, 218.

- Mortensen, George W. Hamilton, USMC, 210.

- Galliford was temporarily attached to the 66th Company from the 17th Company from 1 to 9 June as commanding officer and returned to the 17th Company on 10 June. The actual commanding officer of the 66th Company was Capt Raymond F. Dirksen, who was sick in the hospital. U.S. Marine Corps Muster Rolls, 1893–1958, microfilm publication T977, 460 rolls, Record Group (RG) 127, ARC identifier 922159, National Archives and Records Administration (NARA), Washington, DC; Thomason, The United States Army Second Division Northwest of Chateau Thierry, 83–84; and Clark, The Fourth Marine Brigade in World War I, 32–33.

- Thomason, The United States Army Second Division Northwest of Chateau Thierry, 83–84.

- The “square woods” was not shown on the Marines’ maps. It would cause problems later in the day when Hamilton would misinterpret his objective and extend too far forward, eventually withdrawing back to his objective on the forward slope of Hill 142. Thomason, The United States Army Second Division Northwest of Chateau Thierry, 84.

- Thomason, The United States Army Second Division Northwest of Chateau Thierry, 85.

- Mortensen, George W. Hamilton, USMC, 211–12.

- Kemper F. Cowling, comp., and Courtney R. Cooper, ed. “Dear Folks at Home - - -”: The Glorious Story of United States Marines in France as Told by Their Letters from the Battlefield (Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin, 1919), 126.

- Capt Jonas Platt, “Holding Back the Marines: They Would Go to Germany and Bag the German Army,” Ladies Home Journal, September 1919, 114. Boche or bosche was pejorative slang used by French and American soldiers to refer to German soldiers.

- Cowling and Cooper, “Dear Folks at Home - - -,” 87–88.

- Keller Rockey commanded the 67th Company earlier. He would later command the 5th Marine Division on Iwo Jima dur- ing World War II and retired as a lieutenant general in 1950. Thomason, The United States Army Second Division Northwest of Chateau Thierry, 83, 87; and Clark, Devil Dogs, 100.

- Clark, The Fourth Marine Brigade in World War I, 36.

- George B. Clark, Citations and Awards to Members of the 4th Marine Brigade (Pike, NH: Brass Hat, 1993), 18. Original awards were the Army Distinguished Service Cross (DSC) and Silver Star Citation. See also George B. Clark, A List of Officers of the 4th Marine Brigade (Pike, NH: Brass Hat, 1995), 3–20; Clark, Cita- tions and Awards to Members of the 4th Marine Brigade, 2–52; and Jane Blakeney, Heroes: U.S. Marine Corps, 1861–1955: Armed Forces Awards, Flags (Washington, DC: Guthrie Lithograph, 1957).

- Mackin, Suddenly We Didn’t Want to Die, 17–18.

- Clark, Citations and Awards to Members of the 4th Marine Brigade, 25; Clark, The Fourth Marine Brigade in World War I, 35; and Camp, The Devil Dogs at Belleau Wood, 75–77.

- Mortensen, George W. Hamilton, USMC, 78.

- Clark, Citations and Awards to Members of the 4th Marine Brigade,13.

- Clark, Citations and Awards to Members of the 4th Marine Brigade,18. Because the muster rolls indicate only “wounded,” not the na- ture of the wounds, it is has not been possible to identify the Marine who lost his hand nor the specific injury that resulted in him losing his hand; however, since he grabbed the gun’s muzzle, his hand may have been shot off.

- Thomason, The United States Army Second Division Northwest of Chateau Thierry, 89.

- Thomason, The United States Army Second Division Northwest of Chateau Thierry, 86–87.

- Thomason, The United States Army Second Division Northwest of Chateau Thierry, 90.

- Mortensen, George W. Hamilton, USMC, 212.

- George B. Clark, ed., Devil Dog Chronicle: Voices of the 4th Marine Brigade in World War I (Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 2013), 163.

- Maj Littleton W. T. Waller Jr., Final Report of the 6th Machine Gun Battalion (Pike, NH: Brass Hat), 15; and LtCol Frank E. Ev- ans, “Demobilizing the Brigades,” Marine Corps Gazette 4, no. 4 (December 1919): 303–14.

- Cowling and Cooper, “Dear Folks at Home - - -,” 127.

- Clark, Devil Dogs, 210n41.

- Platt, “Holding Back the Marines,” 114.

- See Robert Asprey, At Belleau Wood (New York: G. P. Putnam’s Sons, 1965), 151. Hunter also was known as “Beau.”

- Platt, “Holding Back the Marines,” 114.

- Clark, Citations and Awards to Members of the 4th Marine Brigade, 25; Clark, The Fourth Marine Brigade in World War I, 35; and Camp, The Devil Dogs at Belleau Wood, 75–77.

- Mortensen, George W. Hamilton, USMC, 212–13.

- Clark, Citations and Awards to Members of the 4th Marine Brigade, 38.

- Cowling and Cooper, “Dear Folks at Home - - -,” 127–28.

- Clark, Devil Dogs, 105–6.

- 2d Division, Summary of Operations in the World War, 10, 11; and Clark, Devil Dogs, 106.

- Clark, Devil Dogs, 110.

- Thomason, The United States Army Second Division Northwest of Chateau Thierry, 88.

- Thomason, The United States Army Second Division Northwest of Chateau Thierry, 89.

- Otto, “The Battles for the Possession of Belleau Woods, June 1918,” 944.

- Maj Edwin N. McClellan, “Capture of Hill 142, Battle of Belleau Wood, and Capture of Bouresches,” Marine Corps Gazette 5, no. 3 (September 1920): 284.

- Clark, The Fourth Marine Brigade in World War I, 38.

- Clark, Citations and Awards to Members of the 4th Marine Brigade, 20–21.

- Clark, Devil Dogs, 104–5.

- Thomason, The United States Army Second Division Northwest of Chateau Thierry, 90.

- Cowling and Cooper, “Dear Folks at Home - - -,” 128.

- Cowling and Cooper, “Dear Folks at Home - - -,” 128; and Clark, Citations and Awards to Members of the 4th Marine Brigade, 23. Born Ernest August Janson on 17 August 1878, Janson spent 10 years in the Army before he enlisted in the Marine Corps at Marine Barracks Bremerton, WA, under the name of Charles F. Hoff- man. On 3 January 1921, he submitted a letter to Headquarters Marine Corps requesting that his record be corrected to reflect his given name (Ernest August Janson). According to the letter, Janson enlisted in the U.S. Army in late 1899 but deserted about July 1900. On 10 November 1900, Janson reenlisted in the Army as Charles Hoffman. He honorably served in the Army under the name Hoffman before enlisting in the Marine Corps on 14 June 1910 under the same name. Headquarters accepted the request in late January 1921 and corrected all of Hoffman’s service records to the name of Janson. Janson retired from the Marine Corps as a sergeant major on 30 September 1926.

- Clark, Devil Dogs, 107.

- Thomason, The United States Army Second Division Northwest of Chateau Thierry, 91; Clark, The Fourth Marine Brigade in World War I, 39; and, Otto, “The Battles for the Possession of Belleau Woods, June 1918,” 945.

- Cowling and Cooper, “Dear Folks at Home - - -,” 129.

- Clark, Citations and Awards to Members of the 4th Marine Brigade, 47.

- Clark, Citations and Awards to Members of the 4th Marine Brigade, 40.

- Clark, Devil Dogs, 109–10.

- Clark, The Fourth Marine Brigade in World War I, 39.

- Thomason, The United States Army Second Division Northwest of Chateau Thierry, 91.

- Clark, Devil Dogs, 101, 128.

- Clark, Devil Dogs, 207.

- Clark, Devil Dogs, 202.

- Clark, Devil Dogs, 112–13.

- Otto, “The Battles for the Possession of Belleau Woods, June 1918,” 962.

- Clark, The Fourth Marine Brigade in World War I, 39.

- Clark, The Fourth Marine Brigade in World War I, 39.

- Mackin, Suddenly We Didn’t Want to Die, 44.

- Mackin, Suddenly We Didn’t Want to Die, viii.