PRINTER FRIENDLY PDF

EPUB

AUDIOBOOK

In August 1990, Iraqi military forces invaded the neighboring nation of Kuwait; the large Iraqi Army quickly overwhelmed the small Kuwait armed forces. Under President George H. W. Bush, the United States assembled a global Coalition of concerned nations, first to defend Saudi Arabia against further Iraqi aggression, then to eject the Iraqi military from Kuwait.

The Gulf War would represent the largest deployment of U.S. Marines since the Vietnam War. It challenged the entire warfighting establishment of the Marine Corps—aviation, ground, and logistics—and forced a generation of Marines to put two decades of planning and training to the test. The Corps would see many of its tactical and operational philosophies justified under combat conditions. But the Corps’ most cherished operational justification—amphibious warfare—was never put to the test. Powerful Marine air-ground task forces (MAGTFs) remained a threat at sea; however, aside from some small raids, feints, and minor postwar landings acted as a floating reserve, a major amphibious assault on Kuwait never materialized. Despite planning for a landing, the difficulties of landing in Kuwait and the lack of any clear benefits from such a landing kept it as a feint, albeit a powerful one, which diverted significant Iraqi forces from the main lines of attack.

Gearing Up for War

The 13th Marine Expeditionary Unit (Special Operations Capable) (13th MEU[SOC]) was the first amphibious task force to reach the war zone, on 7 September 1990. Prior to getting underway, the unit went through a training cycle designed to prepare it to conduct different types of special operations that might be encountered during its deployment.2 These special operations included recovering lost aircraft, rescuing hostages, evacuating civilians from hostile environments, and training local forces.3 Originally, 13th MEU(SOC) was deployed on a scheduled cruise of the western Pacific Ocean in June 1990. These “WestPac” cruises were an annual six-month deployment that rotated between West Coast Marine units; the deployed units served as the landing force of the U.S. Navy’s Seventh Fleet. The expeditionary unit was commanded by Colonel John E. Rhodes, which included Battalion Landing Team 1/4 (1st Battalion, 4th Marines), Marine Medium Helicopter Squadron (Composite) 164, and Marine Expeditionary Unit Service Support Group 13. These Marines were embarked on the ships of Amphibious Squadron 5, an amphibious ready group that included the USS Okinawa (LPH 3), USS Ogden (LPD 5), USS Fort McHenry (LSD 43), USS Cayuga (LST 1186), and USS Durham (LKA 114).4 The original cruise was planned for six months, but the deployment was extended as a result of the crisis in the Gulf by nearly four months. Due to the protracted timeframe, the Marines began calling themselves the “Raiders of the Lost ARG [amphibious ready group].”5 The 13th MEU(SOC) began its cruise of the western Pacific with a training exercise in the Philippines in July 1990. An earthquake on the island of Luzon on 16 July led to a disaster relief operation that lasted through the end of the month. A scheduled port visit to Hong Kong followed in August, but the Raiders of the Lost ARG were then ordered to the Persian Gulf, arriving in the region on 7 September.6

This propaganda leaflet dramatically illustrates the threat of a Marine amphibious landing to Iraqi forces in Kuwait. Marine Corps History Division

The next Marine force afloat sent to the Persian Gulf was assembled on the East Coast. In August 1990, the 4th Marine Expeditionary Brigade (4th MEB) was commanded by Major General Harry W. Jenkins Jr., and the brigade was preparing to train with North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) forces in two exercises—Teamwork and Bold Guard 90—in northern Europe. Stationed primarily at Camp Lejeune, North Carolina, the brigade was traditionally oriented toward Europe and Africa. In addition to preparing for the upcoming exercises, the brigade kept an eye on civil wartorn Liberia, where the 22d Marine Expeditionary Unit (22d MEU) was conducting a noncombatant evacuation and defending the U.S. embassy throughout August 1990. The focus of the brigade abruptly shifted on 10 August, when it was ordered to the Persian Gulf, forcing units that had trained for operations in Norway to turn in their cold weather gear for desert warfare garb.7 To be adequately prepared for the deployment, the MEB would require additional elements for full support. The ground combat element of Jenkins’s brigade, Regimental Landing Team 2, was commanded by Colonel Thomas A. Hobbs. Major units of the regimental combat team included 1st Battalion, 2d Marines; 3d Battalion, 2d Marines; 1st Battalion, 10th Marines (Reinforced); Companies B and D, 2d Light Armored Infantry Battalion; Company A, 2d Assault Amphibian Battalion; and Company A, 2d Tank Battalion.

The logistics element came from Brigade Service Support Group 4, commanded by Colonel James J. Doyle Jr., and it included the 2d Military Police Company, 2d Medical Battalion, 2d Dental Battalion, 2d Maintenance Battalion, 2d Supply Battalion, 8th Communications Battalion, 8th Motor Transport Battalion, 8th Engineer Support Battalion, and 2d Landing Support Battalion. The 4th MEB aviation combat element was Marine Aircraft Group 40, commanded by Colonel Glenn F. Burgess. Because the group was deploying on board amphibious warfare vessels, the only fixed-wing aircraft in the group were the McDonnell-Douglas AV-8B Harriers of Marine Attack Squadron 331. Marine Medium Helicopter Squadrons 263 and 365 brought Boeing Vertol CH-46 Sea Knights; Marine Heavy Helicopter Squadron 461 was equipped with Sikorsky CH-53E Super Stallions; and Marine Light Attack Helicopter Squadron 269 flew Bell AH-1 Sea Cobras and Bell UH-1 Hueys.8

The brigade was embarked on the ships of the U.S. Navy’s Amphibious Group 2, commanded by Rear Admiral John B. LaPlante. The ships were divided into three transit groups: Transit Group 1 consisted of the USS Shreveport (LPD 12), USS Trenton (LPD 14), USS Portland (LSD 37), and USS Gunston Hall (LSD 44); Transit Group 2 comprised USS Nassau (LHA 4), USS Raleigh (LPD 1), USS Pensacola (LSD 38), and USS Saginaw (LST 1188); and Transit Group 3 included USS Iwo Jima (LPH 2), USS Guam (LPH 9), USS Manitowoc (LST 1180), and USS LaMoure County (LST 1194).9 In addition, Military Sealift Command supported the brigade with a squadron that included USNS Wright (T-AVB 3) and two vehicle cargo ships in the MV Cape Domingo (T-AKR 5053) and MV Strong Texan (T-AK 9670). Because there was not enough cargo tonnage for the brigade’s needs, three additional vessels were leased for the duration of the deployment; these non-naval vessels were the MV Bassro Polar, MV Pheasant, and MV Aurora T.10

The lack of amphibious shipping impacted the amphibious forces in the Gulf War from the beginning. The 4th MEB was intended to deploy on two dozen amphibious warfare vessels, but only a dozen were available in time for the brigade’s deployment. As a result, some of the brigade’s assault equipment and supplies were loaded on board the Military Sealift Command vessels. The brigade loaded the available ships at Morehead City and Wilmington, North Carolina. The dispersed loading sites and rushed embarkation created confusion that required the brigade’s shipping to reorganize and reload in al-Jubayl, Saudi Arabia, in November 1990. Transit Group 1 departed on 17 August; Transit Group 2 departed on 20 August; and Transit Group 3 departed on 21 August, each crossing the Atlantic and Mediterranean and passing through the Suez Canal to the Persian Gulf.11

Paul Westermeyer, U.S. Marines in the Gulf War, 1990–1991: Liberating Kuwait (Quantico, VA: Marine Corps History Division, 2014), 43

Amphibious Group 2 arrived in the Gulf in early September, with the transit groups arriving in the same order they had departed, on 3 September, 6 September, and 9 September, respectively. The brigade’s Military Sealift Command vessels arrived from mid-September through mid-October. Because they were not present when these vessels were loaded, the brigade’s logistics officers had to physically board each vessel to find and record the location of all their cargo in person.12

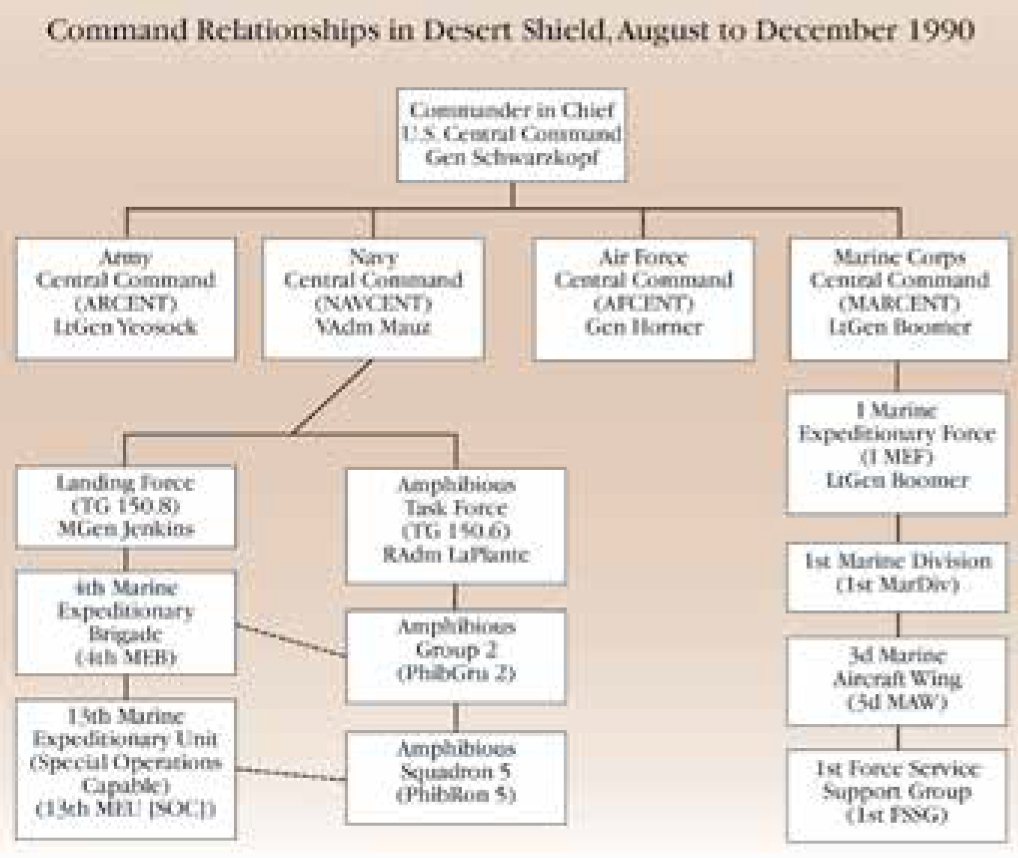

Command Relationships

Following Navy–Marine Corps amphibious doctrine, the 4th MEB and 13th MEU(SOC) fell under the control of U.S. Naval Forces Central Command, rather than under Lieutenant General Walter E. Boomer’s Marine Forces Central Command. Through December 1990, Vice Admiral Henry H. Mauz Jr. commanded Central Command’s naval forces. Amphibious Group 2 and Amphibious Squadron 5 formed the Amphibious Task Force (TG 150.6), commanded by Rear Admiral LaPlante, and the two Marine expeditionary forces formed the Landing Force (TG 150.8), commanded by Major General Jenkins.13

The Marine expeditionary forces in the Amphibious Task Force 150.6 were intended as a theater reserve, and their employment was controlled directly by General H. Norman Schwarzkopf, commander of U.S. Central Command. During Operation Desert Shield, they were prepared to reinforce the troops defending Saudi Arabia if needed or to launch amphibious assaults or raids against the enemy’s rear if the Iraqis attacked Saudi Arabia. Their presence also was intended to divert Iraqi forces toward defending the coast, thus reducing the number of troops faced inland.14

Admiral Mauz saw the terminal end of the Persian Gulf as particularly inhospitable for naval forces, with Iran a constant danger on the flank of any naval force passing through the Strait of Hormuz and up the Gulf to Kuwait. Admiral Mauz later declared: “I wanted to see an amphibious landing as much as anybody. . . . The trouble was, there was no good place to do a landing.”15 Mauz believed that Desert Shield would shape inter-Service competition in the post-Soviet world and that the Army and Air Force were looking to replace their NATO missions with traditional Navy/Marine Corps expeditionary missions; therefore, he wanted the naval forces to have an impact on the conflict. Despite this, he made “insistent and re- peated” requests to General Schwarzkopf to halve the number of amphibious ships in the area. Mauz’s belief that amphibious operations were not practical in the Gulf likely led General Jenkins to conclude that the commander of Naval Forces Central Command “displayed little interest in developing a naval campaign that went beyond the level of presence.”16

During Exercise Sea Soldier III in the Persian Gulf, the bow ramp of a utility landing craft from the amphibious assault ship USS Nassau (LHA 4) descends as troops and vehicles prepare to hit the beach in support of Operation Desert Shield. Defense Imagery DN-ST-92-07370

General Schwarzkopf repeatedly denied Admiral Mauz’s request to reduce the amount of amphibious shipping under his command because the Marines afloat were already being used as a reserve force as well as a threat and feint against the Iraqis, who could never rule out the possibility of an amphibious assault. General Jenkins and his staff prepared various amphibious options for the 4th MEB and the 13th MEU(SOC), both separately and in tandem. These options included landings behind an Iraqi thrust into Saudi Arabia as well as reinforcement of the American and allied forces defending Saudi Arabia. Because the shoreline of the Gulf was relatively unsuited for amphibious operations, the reinforcement mission was considered most likely.17

The hasty departure of General Jenkins’s troops and their previous training for exercises in Norway left the brigade ill-prepared for amphibious operations in a desert environment. To rectify these problems, a series of four amphibious exercises were planned in the friendly nation of Oman, each dubbed “Sea Soldier.” Sea Soldiers I and II took place in October and early November, respectively. In addition to practicing amphibious landings, the exercises gave the Marines a chance to conduct maintenance that could not be completed on ship and to rearrange the loading of the amphibious vessels to better suit the staff’s planning. The 13th MEU(SOC) worked with the brigade in these exercises as well, highlighting the unity of the amphibious task force.18 Throughout October and November, the three leased vessels—the Bassro Polar, Pheasant, and Aurora T—were off-loaded in al-Jubayl, and their cargos were combat loaded onto the two roll-on/roll-off prepositioning ships.19 Major General Jenkins explained, “This was the first time that [Maritime Prepositioning] ships had ever been combat loaded to support a general landing plan for the amphibious force.”20 Three of the ships assigned to the brigade’s Military Sealift Command support squadron were leased vessels with foreign flags, and thus unable to be employed in a combat zone. With the prepositioning ships now emptied of gear, two vessels from Maritime Prepositioning Ship Squadron Two—the MV PFC William Baugh Jr. (T-AK 3001) and the MV 1stLt Alex Bonnyman Jr. (T-AK 3003)—were assigned to the brigade’s support squadron instead.

The 13th MEU(SOC) had been deployed since June 1990, when it had departed on its scheduled cruise of the Pacific. On 4 November, the expeditionary unit departed the Persian Gulf region and sailed for Subic Bay in the Philippines, with orders to rearm and train, preparing to possibly return to the Gulf at a later date. The departure of Colonel John Rhodes’s Marines left the 4th MEB as the sole amphibious landing force available in the Persian Gulf region until December.

Planning for War

Operation Imminent Thunder was conducted during 15–21 November 1990 by Central Command at General Schwarzkopf’s orders. This training exercise was conducted to test the plan for defending Saudi Arabia and to determine what issues would arise from the large joint/combined force working together in the desert kingdom.21 It was a five-phase operation that focused on air and amphibious exercises paired with tests of command, control, and communications. The exercise also served to strengthen General Boomer’s I Marine Expeditionary Force (I MEF) staff. Although Marine expeditionary forces were an established part of Marine Corps doctrine, there was little expectation that they would be employed. The Marine expeditionary units deployed annually to the Mediterranean and the Pacific, and the Marine expeditionary brigades exercised regularly, but few expected the Corps to deploy an expeditionary force outside a major war. Operation Imminent Thunder provided an opportunity for the MEF staff to practice controlling the battle in a joint/combined environment.22

The exercise’s amphibious landings were originally planned for the port of Ras al-Mishab, but its proximity to the Kuwaiti border and the possibility of unintentional conflict with Iraqi forces led to General Schwarzkopf shifting the exercise south to the port of Ras al-Ghar. The new site was much more accessible to the media, which was eager for any new footage as the confrontation continued into its third month. Marine amphibious capabilities received a great deal of press attention as a result, and the Amphibious Task Force commander, Rear Admiral John LaPlante, later described it as “beating our chest for the press.” Ironically, most of the amphibious landings were canceled because of dangerous seas, but the extensive air and communication operations were a success.23 In late November 1990, with Saudi Arabia secured, the president ordered Central Command to shift its focus of planning from defending Saudi Arabia to liberating Kuwait. Additional forces were sent to the Persian Gulf region to prepare for the required offensive. The amphibious forces were reinforced by the 5th Marine Expeditionary Brigade (5th MEB), commanded by Brigadier General Peter J. Rowe. Brigadier General Rowe’s brigade was normally the designated sea-deployment brigade of the I MEF (just as the 7th MEB was designated as the Maritime Prepositioning Force brigade), but many of the units that would normally be called on to fill out the brigade had already been reassigned to fill out the forces deploying for Desert Shield. As a result, the brigade’s elements included large numbers of reservists operating along-side their active-duty Marines.24

On 1 December 1990, Vice Admiral Stanley R. Arthur took over from Admiral Mauz as commander of U.S. Naval Forces, Central Command, and commander of the U.S. Seventh Fleet.25 Admiral Arthur was described as a “fighter” by General Schwarzkopf and General Boomer, both of whom he got along with very well. However, he was not eager to conduct an amphibious operation, stating after the war, “I knew that neither he [Schwarzkopf] nor the Chairman [of the Joint Chiefs, Colin Powell] wanted to have an amphibious landing. That was the last thing they wanted to have happen. And there was never going to be an occasion where an amphibious landing was going to be necessary to conduct the war the way they wanted to.”26

Although the air campaign had already begun, most of the Marines serving on board the amphibious task force spent the end of January participating in Sea Soldier IV, the last amphibious exercise conducted for the Gulf War. Both the 4th and 5th MEBs participated in this exercise, marking it as the largest Marine amphibious exercise since 1964.27

The exercises had served their purpose as the two-brigade amphibious landing was a success. Three battalions of the landing force were lifted ashore by the brigade’s helicopter squadrons, training to handle prisoners of war occurred, and the brigades underwent a week of desert training and equipment maintenance before conducting a tactical withdrawal exercise from the beach back to the ships. For most of the Marines in the 4th MEB, floating in the North Arabian Sea since early September, this would be the highlight of a monotonous Desert Shield and Desert Storm deployment.28

Map courtesy of U.S. Army

When the allied air attacks against Iraq began on 17 January 1991, the seaborne feint needed reinforcement in order to remain credible. Amphibious raids were one method of reinforcing that threat.29 On 23 January 1991, Navy Captain Thomas L. McClelland, commanding Amphibious Squadron 5, and Colonel John E. Rhodes, commander of the 13th MEU(SOC), were ordered to plan for an amphibious raid on several Iraqi-held Kuwaiti islands; this raid was code named Operation Desert Sting. Before the operation began, Iraqis on one of the targeted islands, Qaruh, surrendered on 25 January to the USS Curts (FFG 38). On 26 January, the Iraqi garrison on another of the targeted islands, Umm al-Maradim, created a sign for U.S. Navy reconnaissance aircraft photographing the island that indicated they wished to surrender. The plan for Operation Desert Sting was modified to account for the surrender.

Heavily supported by Navy aircraft, Company A, Battalion Landing Team 1/4 (Rein), landed on the north end of Umm al-Maradim Island at noon on 29 January. They encountered no enemy fire or other resistance and found the island had been deserted by its garrison. The Marines captured or destroyed a large quantity of small arms, machine guns, and mortars as well as several Iraqi antiaircraft guns and missiles. After three hours on the island, the raid force departed, leaving a Kuwaiti flag raised over the island and the words “Free Kuwait” and “USMC” painted on several of the buildings.

By February, the Corps’ plan for liberating Kuwait was not popular among the Marine commanders who would have to execute it. The plan called for both Marine divisions to pass in column through one breach in the Iraqi fortifications, a difficult and time consuming operation. After the war was underway, the Marines in the amphibious task force would land at Ash Shu‘aybah and seize the port to establish a logistics base for the I Marine Expeditionary Force’s advance.30

General Boomer later said:

As we began to plan everything was on the table. In the beginning, it seemed to make sense to use our amphibious capability to come from the Gulf, attack Kuwait on the flank while forces from Saudi Arabia drove up, ultimately conducting a link up. We explored that option carefully. Extensive planning went into that concept. There were schemes to attack up North of Kuwait City, into the Basra area. That line of thinking seemed to be favored by those at Headquarters Marine Corps. When the Navy and Stan Arthur and I really began to explore that concept, it became clear that part of the Gulf did not lend itself to an amphibious operation for a lot of reasons. Going back, there was all this criticism of Army planners working in a vacuum and devising plans and here we had planners at Headquarters Marine Corps/Quantico devising plans for us from half way around the world, none of which ultimately made any sense. Admiral Arthur and I gave them as much credence as they deserved, which was not much.31

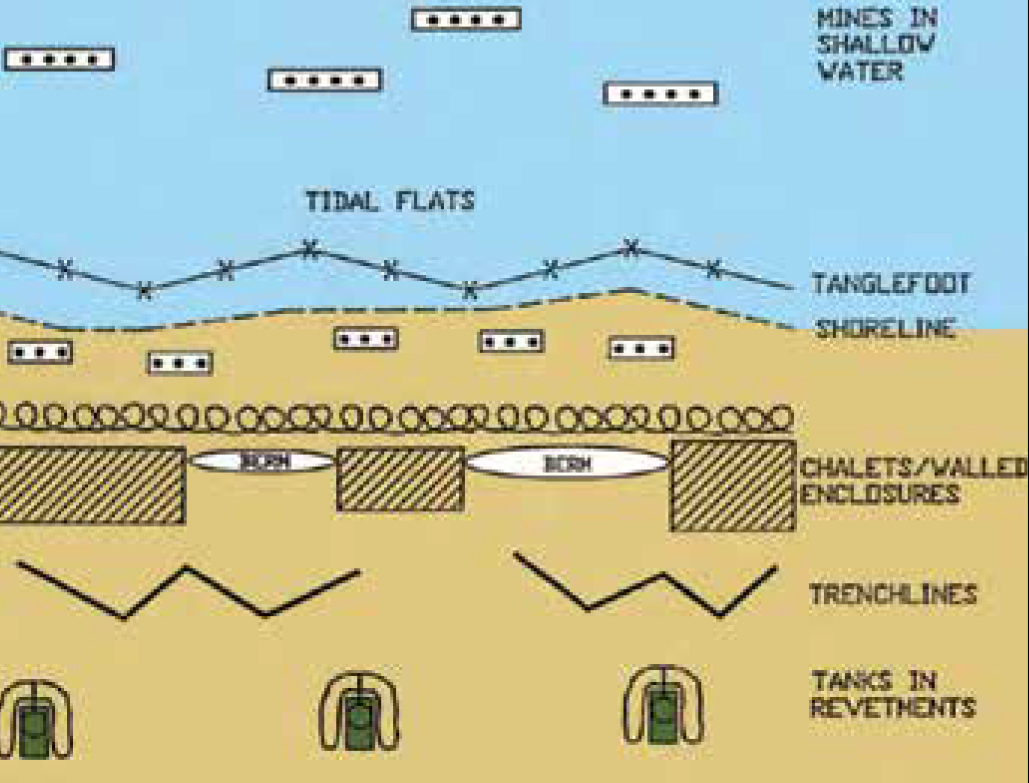

An amphibious landing into Kuwait involved surmounting all of the standard difficulties of an amphibious assault, such as weather, tides, beach quality, shipping, and enemy forces, as well as the unique challenges presented by the oil industry’s heavy presence in the Persian Gulf.

In addition, relatively few beaches were acceptable for a landing in Kuwait. One was available approximately 12 miles from the Saudi border—a landing so close to the front lines that it would provide no operational benefits. Farther north along the coast, the Mina al-Ahmadi oil terminal offered a more appropriate option; beyond that was a heavily urbanized beach area with many civilians and myriad buildings ideal for beach defense. Finally, the north coast of Kuwait and Bubiyan Island was surrounded by mud flats and significant tidal variations.32

Landing in northern Kuwait exposed the majority of the Kuwaiti civilian population to the dangers of an amphibious assault, which would have required heavy air strikes and naval shelling, combining the difficulties of an amphibious assault with those of an urban battle. If the Iraqis put up any sort of fight at all, the collateral damage and civilian death toll would have been significant.33

The refinery and oil terminal of Mina al-Ahmadi was the better choice, but it was one of Kuwait’s prime economic resources. Moreover, the web of storage tanks, pipelines, terminals, and wellheads presented a unique tactical environment with few if any precedents. The Iraqis opened pipelines and well-heads, creating massive amounts of smoke and large oil spills. The smoke turned day into night; however, since American equipment was better suited to poor observation conditions, the smoke generally aided the liberators. The oil spills caused issues but did not hinder military activity. The result of such environmental warfare was an unknown prior to the war, as was the damage that might arise from storage tanks detonating in the refinery. Some estimates concluded that, if the natural gas facility in the Mina al-Ahmadi complex detonated, the resulting explosion could be nuclear in scale.34

In addition to terrain and collateral damage considerations, an amphibious assault required U.S. forces to take Iraqi military capabilities into account. The Iraqi military’s greatest strengths included massed infantry, large artillery forces, and plentiful armored vehicles. Dug in behind beach defenses, even the demoralized Iraqi Army units then in Kuwait might put up a respectable resistance, though this threat applied equally to a land invasion. The Iraqi Air Force and Navy presented threats to an amphibious landing that a land offensive could safely ignore.

The threats to an amphibious assault included Exocet antiship missile-armed Dassault Mirage F1 aircraft. During the “Tanker War” portion of the Iran-Iraq conflict, an Iraqi aircraft fired two Exocet missiles into the USS Stark (FFG 31), severely damaging the frigate and killing 37 of her crew. This history left the U.S. Navy very sensitive to the dangers of the Exocet missile. On 24 January, two Mirages further illustrated this threat, when they followed Coalition strike aircraft on a course along the Saudi coast. Whether through design or good luck, these Iraqi aircraft proceeded along a “seam” in Coalition air defense between the U.S. Navy and the U.S. Air Force. The Iraqi aircraft got far closer to Coalition shipping and port targets than they should have before a pair of Saudi McDonnell Douglas F-15 Eagles successfully intercepted them.35

In addition to aircraft-borne Exocet missiles, the Iraqis fielded Chinese-made, shore-based HY-2 “Silkworm” antiship missiles; they had seven launchers and approximately 50 missiles. The Silkworm missile threat turned out to be somewhat hollow; only one attack occurred. Two missiles were launched on 25 February at the USS Missouri (BB 63); one crashed harmlessly into the sea, and the second was downed by a British Sea Dart surface-to-air missile fired by HMS Gloucester (D 96). The USS Missouri located the launcher with its drone reconnaissance craft and destroyed it with a salvo of its 16-inch, .50-caliber Mark 7 guns.36

The Iraqi Navy presented two threats to Coalition naval and amphibious forces with missile boats armed with surface-to-surface antiship missiles and mines. The missile boat threat was eliminated on 29 and 30 January in a series of engagements dubbed the “Bubiyan Turkey Shoot” by U.S. Navy personnel. The Iraqi Navy attempted to send the majority if its vessels to Iran, hoping they could be preserved there for postwar use. Many Iraqi vessels were destroyed by Coalition aircraft flying repeated strikes against them before they reached Iranian waters. The few Iraqi vessels that made their destination in Iranian ports were seized by Iran.37

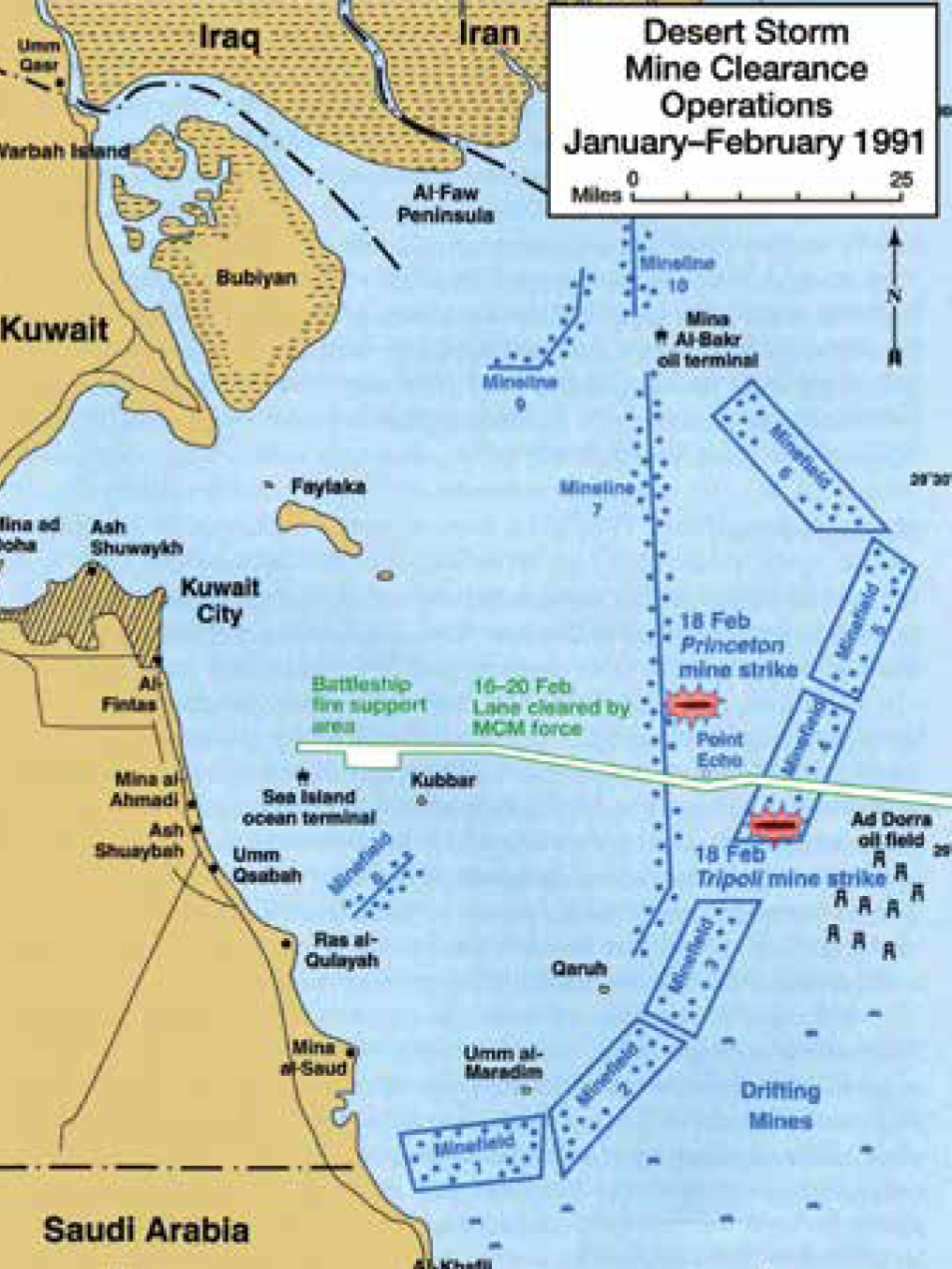

The threat from naval mines was more significant to Coalition naval forces, and the U.S. Navy was ill-equipped to deal with it, despite the prevalence of mine warfare during the Tanker War, as when the USS Samuel B. Roberts (FFG 58) was nearly sunk by an Iranian mine on 14 April 1988. The United States deployed Sikorsky MH-53E Sea Dragon helicopters for countermine operations, sweeping narrow lanes at more than twice the speed of mine countermeasure vessels. After preliminary searches, the mine sweepers would follow. The USS Avenger (MCM 1), USS Impervious (MSO 449), USS Leader (MSO 490), and USS Adroit (MSO 509) comprised the U.S. mine counter-measures force, while the Royal Navy deployed the ocean survey ship HMS Herald (H 138) and five Hunt-class minesweepers: HMS Atherstone (M 38), HMS Cattistock (M 31), HMS Dulverton (M 35), HMS Hurworth (M 39), and HMS Ledbury (M 30). American mine sweeping got off to a slow start; Admiral Mauz considered antimine warfare a low priority, so American minesweepers were sent to the Persian Gulf against his objections. Crewed by temporarily assigned sailors and activated reservists, the ships had not trained together prior to the crisis, and as a result the mine countermeasures forces were not ready for operations until November. British vessels and other NATO nations’ mine countermeasures vessels were technologically superior to those of the United States. Admiral Arthur later remarked that “everybody in the world had better minesweepers out there than I did.”38

As the air war moved forward, Navy and Marine planners on Admiral Arthur’s staff continued evaluating amphibious landing options, especially a landing on the coast of Kuwait in support of the Marine Corps offensive across the Saudi-Kuwaiti border. Rear Admiral Samuel J. Cox, who was then an assistant intelligence officer on Arthur’s staff, recalled the various Iraqi antiship capabilities listed above and how they had not yet been targeted during the air campaign: “Attrition of the primary threat systems is less than 5 percent. At the present rate of attrition, it will be sometime next year before we reach 50 percent.” As long as these threats remained essentially unaddressed, minesweeping operations in the northern Gulf could not begin and amphibious operations would not be conducted.39

The postwar Gulf War Airpower Survey, commissioned by the Air Force, claimed that 46 percent of all carrier strike sorties were launched at maritime targets in the first two weeks of the air campaign. It also found that the Iraqi surface fleet was neutralized by 2 February, but that the shore-based Silkworm sites remained a threat until the ground campaign began. These sites were difficult to confirm destroyed, and many decoy sites were suspected. Of the 45 strikes launched against Silkworm strikes, 80 percent occurred after 7 February.40

On 2 February, General Boomer flew out to the USS Blue Ridge (LCC 19) for a conference with General Norman Schwarzkopf and Vice Admiral Stanley Arthur concerning amphibious operations, especially the planned landing at Ash Shu‘aybah. At the meeting, it became clear the Navy was not ready to conduct any large amphibious operations, primarily because of the large number of mines the Iraqis had deployed in Kuwaiti waters. General Schwarzkopf was not enthusiastic either, since he was informed during the meeting that the amphibious operation and subsequent coastal fighting would likely involve massive destruction to Kuwait’s most densely populated areas. He remarked that he was “not going to destroy Kuwait in order to save it.” When asked if the landing was required for success, General Boomer replied no, with the caveat that the amphibious deception and mine-clearing operations move forward and that the amphibious forces continue planning so the option would remain available if needed.41

Edward J. Marolda and Robert J. Schneller Jr., Shield and Sword: The United States Navy and the Persian Gulf War (Washington, DC: Naval Historical Center, Department of the Navy, 1998), 248

Although General Schwarzkopf had vetoed a major amphibious invasion, an amphibious feint remained an important part of the Coalition’s plan to draw attention away from both the Marine thrust into central Kuwait and the Army’s wide, sweeping flanking movement to the west. The American battleships conducted naval gunfire support missions along the coast throughout February, and Coalition minelayers cleared lanes through the Iraqi minefields on 16 February.42

The battleship USS Wisconsin (BB 64) fires a round from one of its 16-inch guns at Iraqi targets in Kuwait. In the first days of the ground war, the battleships—directed by Marine ANGLICO teams—often fired in support of the Saudi troops advancing along the coastal highway. Defense Imagery DN-SC-92-08659

The U.S. Navy’s fear of Iraqi mines and lack of confidence in its ability to fully clear the minefields proved well founded. On 17 February, the USS Tripoli (LPH 10) was disabled after it hit a mine. Tripoli had been pressed into service as the platform for the Sikorsky MH-53E Sea Dragon helicopters of the Navy’s Helicopter Mine Countermeasures Squadron 14 during minesweeping operations and was, ironically, engaged in this task when it struck a mine. Later the same day, the USS Princeton (CG 59) also was struck by a mine. Fortunately, and surprisingly, neither vessel suffered fatalities from the mine attacks.43

The Amphibious Feint

In the days leading up to the liberation of Kuwait, and during the ground assault itself, the U.S. battleships fired effectively on Iraqi forces along the coast. Admiral Arthur used the battleships to continue the amphibious feint because they were strongly tied to an amphibious assault. After the war, he remarked, “All I had to do was start moving the battleships . . . and then line General Jenkins and his fine Marines and our amphibs [amphibious ships] up behind them, and there was no doubt in anybody’s mind that we were coming.”44

Most of the battleships’ 16-inch naval gunfire was directed at preplanned targets, but some spectacular direct support was also provided. On 24 February 1991, this came to the aid of the Joint Forces Command–East troops and Captain Douglas R. Kleinsmith of the 1st Air Naval Gunfire Liaison Company (1st ANGLICO):

The Saudi battalion commander, a colonel, looked at him [Kleinsmith] incredulously “You can call in the battleships?” he asked. “Yea[h],” answered Captain Kleinsmith, “That’s why we’re here.” Kleinsmith contacted [the USS] Wisconsin [BB 64] and the battleship opened fire. The captain heard the muted roar of her 16-inch guns through his radio. The 43 seconds required for the first shell to reach its target seemed an eternity. Kleinsmith was beginning to wonder if he had transmitted the wrong coordinates when projectiles began to fall precisely where he wanted them. The Saudi marines stared in amazement as the 2,700 pound shells lifted whole houses into the air. “You can do this anytime?” asked the Saudi battalion commander. Kleinsmith re- plied in the affirmative. “Ah,” exclaimed the colonel, “We can win now.”45

The battleship support was somewhat irrelevant, however, because the Saudi advance encountered almost no resistance on the first day as it advanced into Kuwait and captured thousands of Iraqi prisoners.

In the predawn hours of 25 February, 13th MEU(SOC) conducted a helicopter feint into the Ash Shu‘aybah area, attempting to convince the Iraqis that an amphibious landing was pending. The flight included six CH-46E Sea Knights, two Bell AH-1W Super Cobras, one CH-53E Super Stallion, and one Bell UH-1N Twin Huey. The helicopters flew in low and deliberately popped up to be detected by Iraqi radar at 0449 before returning safely to USS Okinawa. Combined with the battleships’ naval gunfire, the operation appeared to be a success.46

This sketch depicts the extensive beach defenses the Iraqis placed along the Kuwaiti coastline in anticipation of an amphibious landing. Marine Corps History Division

Conclusion

Two relatively large landings by the Marines of the landing force deployed in support of Operation Desert Storm, although neither involved an amphibious assault. On 24 February, the 5th MEB’s 3d Battalion, 1st Marines, landed by helicopter south of the al Wafrah oil field on the Saudi-Kuwaiti border, where it established a blocking position and filled the gap between the I MEF and the Saudi-led Joint Forces Command–East along the coast. After the Iraqi surrender on 28 February 1991, the battalion cleared the forest of Iraqi stragglers.47

On 3 March, the 13th MEU(SOC) landed on the island of Jazirat Faylaka, which was held by the Iraqi 440th Naval Infantry Brigade. Aerial reconnaissance observed white flags as the Iraqis gathered in a communications compound. The Marines conducted a helicopter assault on the island, accepted the Iraqi troops’ surrender, and supervised their evacuation to the USS Ogden.48

The amphibious threat remained a constant concern for the Iraqis throughout the conflict, given the extensive defenses built along the coast manned by five infantry divisions. The Iraqi Navy devoted itself to extensively mining the Kuwait coast and the northern waters of the Persian Gulf. Although some Iraqi officers expressed doubts about an American amphibious assault, it appears to have dominated Saddam Hussein’s thinking as late as 24 February 1991, hours after the Coalition’s offensive was well underway. Postwar examination of Iraqi coastal defenses and a captured sand table depicting Iraqi shore defenses in a Kuwaiti school amply illustrated how seriously the Iraqis took the amphibious threat.49

After the war, the commander of the Iraqi Navy declared that “these [Iraqi] mines proved [their] lethality and effectiveness. They caused havoc within the enemy force.” He continued, “During the epic Mother of All Battles, this weapon [mines] was utilized effectively and successfully to disrupt the allies’ plans in launching any operation from the sea.” His view was shared by the U.S. Navy Central Command commander, Vice Admiral Arthur, who later stated that “Iraq successfully delayed and might have prevented an amphibious assault on Kuwait’s assailable flank, protected a large part of its force from the effects of naval gunfire, and severely hampered surface operations in the northern Arabian Gulf, all through the use of naval mines.”50

This Iraqi sand table was found in a school gymnasium in Kuwait City. The marked Iraqi positions corresponded to their defense plans and indicated how successful the Marines’ amphibious deception was at distracting Iraqi attention from the Saudi-Kuwaiti frontier. Defense Imagery DM-SC-93-05230, courtesy of SSgt J. R. Ruark

Barbed wire, mines, and other obstacles were erected along the shoreline during the Iraqi occupation of Kuwait to prevent or slow attacks by sea. Defense Imagery DN-ST-91-08410

Looking back at the conflict, the Marine commanders felt the role of the amphibious deception needed to be emphasized. Major General James M. Myatt, commander of the 1st Marine Division, recalled: “I think what we can’t dismiss is the level of effort put into the defenses along the beaches by the Iraqis.. . . probably 40% to 50% of the Iraqi artillery pieces were pointed to the east in defense of this perceived real threat—an attack from the Gulf. There were literally hundreds of antiaircraft weapon systems laid in a direct-fire mode from Saudi Arabia all the way up way above Kuwait City to defend against the amphibious threat. I think it [the amphibious feint] saved a lot of Marine lives.”51

•1775•

Endnotes

- Paul Westermeyer is a historian who joined the History Division in 2005. He earned his bachelor’s in history and master’s in military history from The Ohio State University. He was the 2015 recipient of Marine Corps Heritage Foundation’s BGen Edwin Simmons-Henry I. Shaw Award for U.S. Marines in the Gulf War, 1990–1991: Liberating Kuwait. He is the author of U.S. Marines in Battle: Al-Khafji, 28 January–1 February 1991 and the editor of Desert Voices: Oral Histories of Marines in the Gulf War and U.S. Marines in Afghanistan, 2010–2014: Anthology and Annotated Bibliography. He is the series historian for the Marines in the Vietnam War Commemorative Series. Earlier versions of this article were presented at the 83d Annual Meeting of the Society for Military History (2016) and at the 2017 McMullen Naval History Symposium. This article is based on the relevant Marine command chronologies archived at the Marine Corps History Division’s Archives Branch, Quantico, VA; oral histories conducted by the author and other History Division historians; Paul Westermeyer, U.S. Marines in the Gulf War, 1990–1991: Liberating Kuwait (Quantico, VA: Marine Corps History Division, 2014), hereafter Liberating Kuwait; LtCol Ronald J. Brown, U.S. Marines in the Persian Gulf, 1990–1991: With Marine Forces Afloat in Desert Shield and Desert Storm (Washington, DC: History and Museums Division, Headquarters Marine Corps, 1998), hereafter Marine Forces Afloat; Maj Charles D. Melson, Evelyn A. Englander, and Capt David A. Dawson, comps., U.S. Marines in the Persian Gulf, 1990–1991: Anthology and Annotated Bibliography (Washington, DC: History and Museums Division, Headquarters Marine Corps, 1992), hereafter Anthology and Annotated Bibliography; and Edward J. Marolda and Robert J. Schneller Jr., Shield and Sword: The United States Navy and the Persian Gulf War (Washington, DC: Naval Historical Center, 1998).

- These predeployment training programs were the Marine Corps’ reaction in the 1980s to the creation of the joint U.S. Special Operations Command (USSOCOM) that included Army, Navy, and Air Force special operations forces. The Marine Corps did not join USSOCOM until 2006.

- Brown, Marine Forces Afloat, 12.

- Amphibious assault ships are classified as: LPH, landing platform, helicopter; LPD, landing platform, dock; LSD, landing ship, dock; LST, landing ship, tank; and LKA, cargo ship, amphibious.

- This moniker was a humorous play on the title of the popular 1981 movie, Raiders of the Lost Ark. 13th MEU(SOC) Command Chronology (ComdC), July–December 1990 (Archives Branch, Marine Corps History Division, Quantico, VA); and Brown, Marine Forces Afloat, 12–16.

- 13th MEU(SOC) ComdC, July–December 1990; and Brown, Marine Forces Afloat, 15–16.

- 4th MEB ComdC, August 1990 (Archives Branch, Marine Corps History Division, Quantico, VA); Brown, Marine Forces Afloat, 16–22. Operation Sharp Edge, the Liberian evacuations conducted in 1990–91, is described fully in Maj James G. Antal and Maj R. John Vanden Berghe, On Mamba Station: U.S. Marines in West Africa, 1990–2003 (Washington, DC: History and Museums Division, Headquarters Marine Corps, 2004).

- 8 4th MEB ComdC, August 1990.

- Most of these ships were commissioned in the 1970s and nearly all would be decommissioned in the following year or two.

- Brown, Marine Forces Afloat, 22–23, 230; and 4th MEB ComdC, August 1990.

- Brown, Marine Forces Afloat, 21–25, 28; and 4th MEB ComdC, August 1990.

- Brown, Marine Forces Afloat, 30–33; and 4th MEB ComdC, August 1990.

- Brown, Marine Forces Afloat, 34–36, 42; and Marolda and Schneller, Shield and Sword, 84

- Brown, Marine Forces Afloat, 41–45.

- Westermeyer, Liberating Kuwait, 43.

- Brown, Marine Forces Afloat, 42–43; Marolda and Schneller, Shield and Sword, 117–18; and LtGen Bernard E. Trainor, “Amphibious Operations in the Gulf War,” Marine Corps Gazette 78, no. 8 (August 1994): 56.

- Brown, Marine Forces Afloat, 42–43; and Marolda and Schneller, Shield and Sword, 117–18.

- Brown, Marine Forces Afloat, 46–50; 13th MEU(SOC) ComdC, October 1990 (Archives Branch, Marine Corps History Division, Quantico, VA); and 4th MEB ComdC, October 1990 (Archives Branch, Marine Corps History Division, Quantico, VA).

- Roll-on/roll-off ships are designed to carry wheeled cargo, such as trucks, automobiles, or railroad cars that are driven on and off the ship.

- Brown, Marine Forces Afloat, 54–59; and MajGen Harry W. Jen- kins, comments on draft of Westermeyer, Liberating Kuwait, 24 February 2012 (Marine Corps History Division, Quantico, VA).

- In American military parlance, joint operations are conducted by two or more Services (Navy-Army, Air Force–Marine Corps, etc.), while combined operations are conducted by American forces in conjunction with allied foreign military forces. Operation Desert Shield, conducted by forces from all U.S. Armed Services as well as the military forces of several other nations, including Saudi Arabia, Great Britain, France, etc., was therefore a joint/ combined operation.

- I MEF ComdC, November 1990 (Archives Branch, Marine Corps History Division, Quantico, VA); BGen Paul K. Van Riper, “Observations During Operation Desert Storm,” Marine Corps Gazette 100, no. 3 (March 2016): 54–61; and Col Charles J. Quilter II, USMCR, U.S. Marines in the Persian Gulf, 1990–1991: With the I Marine Expeditionary Force in Desert Shield and Desert Storm (Washington, DC: History and Museums Division, Headquarters Marine Corps, 1993), 24–27.

- Transcript of I MEF morning brief, 19–21 November 1990 (Archives Branch, Marine Corps History Division, Quantico, VA); 4th MEB ComdC, November 1990 (Archives Branch, Marine Corps History Division, Quantico, VA); Brown, Marine Forces Afloat, 64–69; and Marolda and Schneller, Shield and Sword, 150.

- 5th MEB ComdC, July–December 1990, Westermeyer Collection (Archives Branch, Marine Corps History Division, Quantico, VA); and Brown, Marine Forces Afloat, 73–76.

- This command change had been scheduled prior to the war and the Chief of Naval Operations decided to go ahead with it despite the crisis.

- Marolda and Schneller, Shield and Sword, 137–38, 150.

- Brown, Marine Forces Afloat, 107–9.

- Brown, Marine Forces Afloat, 107–9.

- Operation Desert Sting is described in greater detail in Brown, Marine Forces Afloat, 139–43.

- Gen Walter E. Boomer, intvw with author, 27 July 2006, hereafter Boomer intvw.

- Boomer intvw.

- RAdm Sam Cox, USN (Ret), “Storm Season: War Clouds Form Over the Sands of Mina al-Ahmadi,” Sextant (blog), Naval History and Heritage Command, 18 February 2016.

- Cox, “Storm Season.”

- Cox, “Storm Season”; and RAdm Sam Cox, USN (Ret), “Gathering Storm: Mina al-Ahmadi in the Crosshairs–Part Two,” Sextant (blog), Naval History and Heritage Command, 24 February 2016.

- Marolda and Schneller, Shield and Sword, 36, 206–7.

- Marolda and Schneller, Shield and Sword, 67.

- Marolda and Schneller, Shield and Sword, 229–32.

- Marolda and Schneller, Shield and Sword, 74–77, 261–63.

- RAdm Sam Cox, USN (Ret), “Storm Front: The Threat of Mina al-Ahmadi–Part Four,” Sextant (blog), Naval History and Heritage Command, 1 March 2016.

- Eliot A. Cohen, “Effects and Effectiveness,” in The Gulf War Air Power Survey, vol. II, Operations and Effects and Effectiveness (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1993), 226–29.

- Brown, Marine Forces Afloat, 130–33; and Marolda and Schneller, Shield and Sword, 254.

- Marolda and Schneller, Shield and Sword, 247–68; and Brown, Marine Forces Afloat, 149–54.

- Brown, Marine Forces Afloat, 149–54.

- Marolda and Schneller, Shield and Sword, 279, 288–89.

- Marolda and Schneller, Shield and Sword, 288.

- Brown, Marine Forces Afloat, 155–56.

- Brown, Marine Forces Afloat, 173–80.

- 13th MEU(SOC) ComdC, March 1991 (Archives Branch, Marine Corps History Division, Quantico, VA); MEU Service Support Group 13 ComdC, February–March 1991 (Archives Branch, Marine Corps History Division, Quantico, VA); and Brown, Marine Forces Afloat, 157–62.

- Kevin M. Woods, The Mother of All Battles: Saddam Hussein’s Strategic Plan for the Persian Gulf War (Annapolis: Naval Institute Press, 2008), 199, 223.

- Woods, The Mother of All Battles, 134; Marolda and Schneller, Shield and Sword, 247–68; and Brown, Marine Forces Afloat, 149–54.

- “The 1st Marine Division in the Attack: Interview with Major General J. M. Myatt, USMC,” U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings 117, no. 11 (November 1991), as quoted in Maj Charles D. Melson (Ret), Evelyn A. Englander, and Capt David A. Dawson, comps., U.S. Marines in the Persian Gulf, 1990–1991: Anthology and Annotated Bibliography (Washington, DC: History and Museums Division, Headquarters Marine Corps, 1992), 145.