One of the more unusual missions in Marine Corps history took place from November 1918 to August 1919. The idea of Marines performing as police and civil administrators was certainly nothing new. This time, however, it was not taking place in Haiti, the Dominican Republic, or Nicaragua but in the heart of Europe, specifically the German Rhineland. Also unique to this situation was the size of the Marine contingent—specifically, a fully equipped brigade that counted among its members five future Marine Corps Commandants as well as a number of other Marines who later became legends of the Corps. In spite of the size of the force, the importance of the mission, and the celebrity status of some of the participants, the Marine brigade’s service in the occupation of Germany is unknown by many and virtually unappreciated.

The 4th Brigade’s service, as part of the U.S. Army’s 2d Division in the American Expeditionary Forces (AEF), has been well covered elsewhere so this epoch begins where those histories end—on 11 November 1918. Just days previously, on the night of 30–31 October 1918, the 4th Brigade moved into the front lines south of Landres-et-Saint Georges. The brigade had enjoyed a short respite from battle, but now was joining the rest of the AEF in the massive Meuse-Argonne Campaign. The American offensive began on 26 September 1918, and many of the original attacking divisions were roughly handled by the Germans. With a good number of them now requiring rest and refit, other divisions, such as the 2d Division, received the call to join the fight. Early on the morning of 1 November, the brigade began its final combat operation of the war. By 1100 on the morning of 11 November 1918, the Marines had advanced 30 kilometers and, after conducting attacks across the Meuse River, were set in positions on the opposing bank.

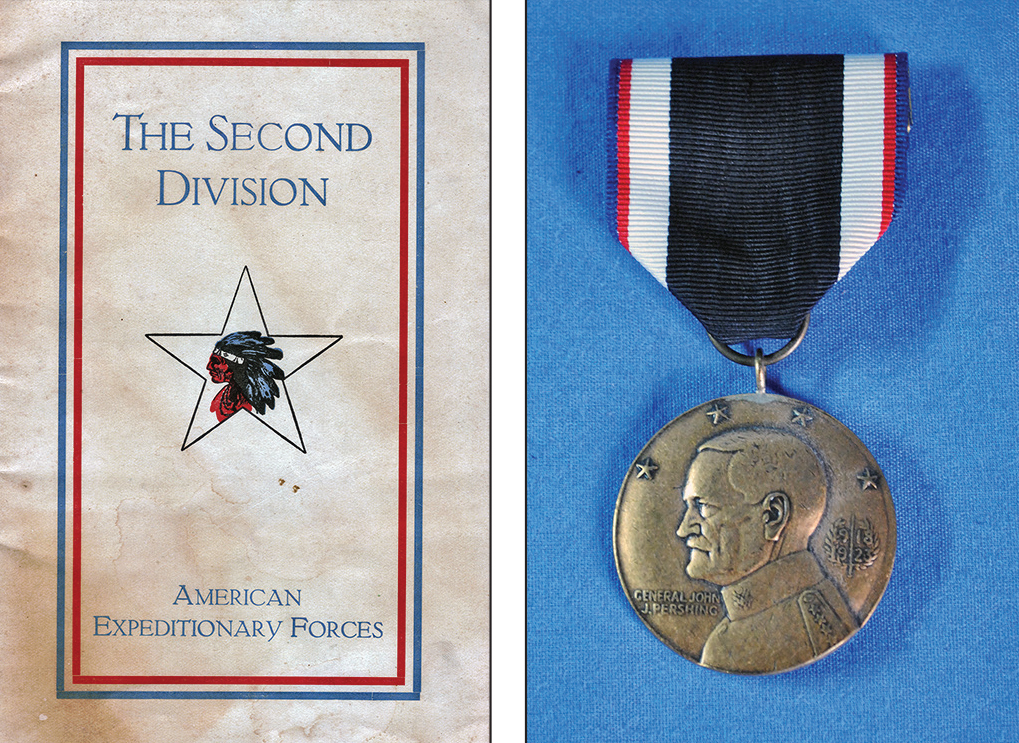

(Left) Program from 2d Division. Courtesy of the Peck family. (Right) Occupation of Germany Medal. Courtesy of Alison Hutton

The Armistice

As the guns fired their last shots that November morning, the western front went silent for the first time in more than four years. The German Army was unable to continue fighting due to the collapse of its government, the strength of the Allied offensive, and the revolution flaring up all over the fatherland. The hastily selected German representatives to the Armistice negotiations had little choice but to accept the Allied peace terms, which included two bitter pills: occupation of the Rhineland and a war reparations program. The Armistice document, signed in a railcar near Compiègne, France, put into effect a tentative peace and led the Americans and their allies into the unusual circumstance of occupying large portions of Germany. While much of the world celebrated the end of the war, the staffs of the American, British, French, and Belgian armies were hurriedly trying to figure out how they would administer the peace. The AEF found itself transitioning from a combatant force into an administrative organization now responsible for the governmental and economic control of 2,500 square miles of the German homeland, which included a potentially hostile population.

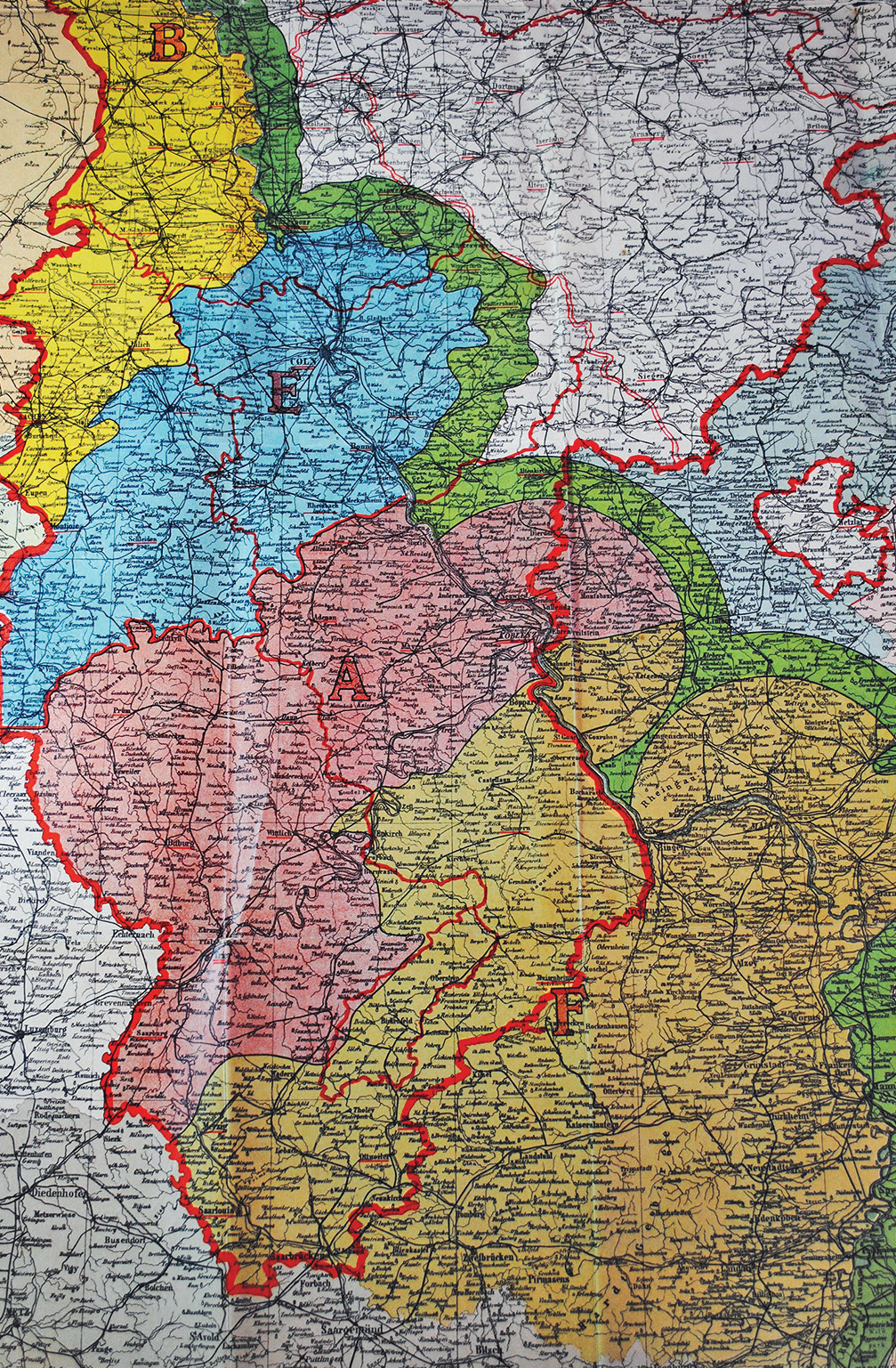

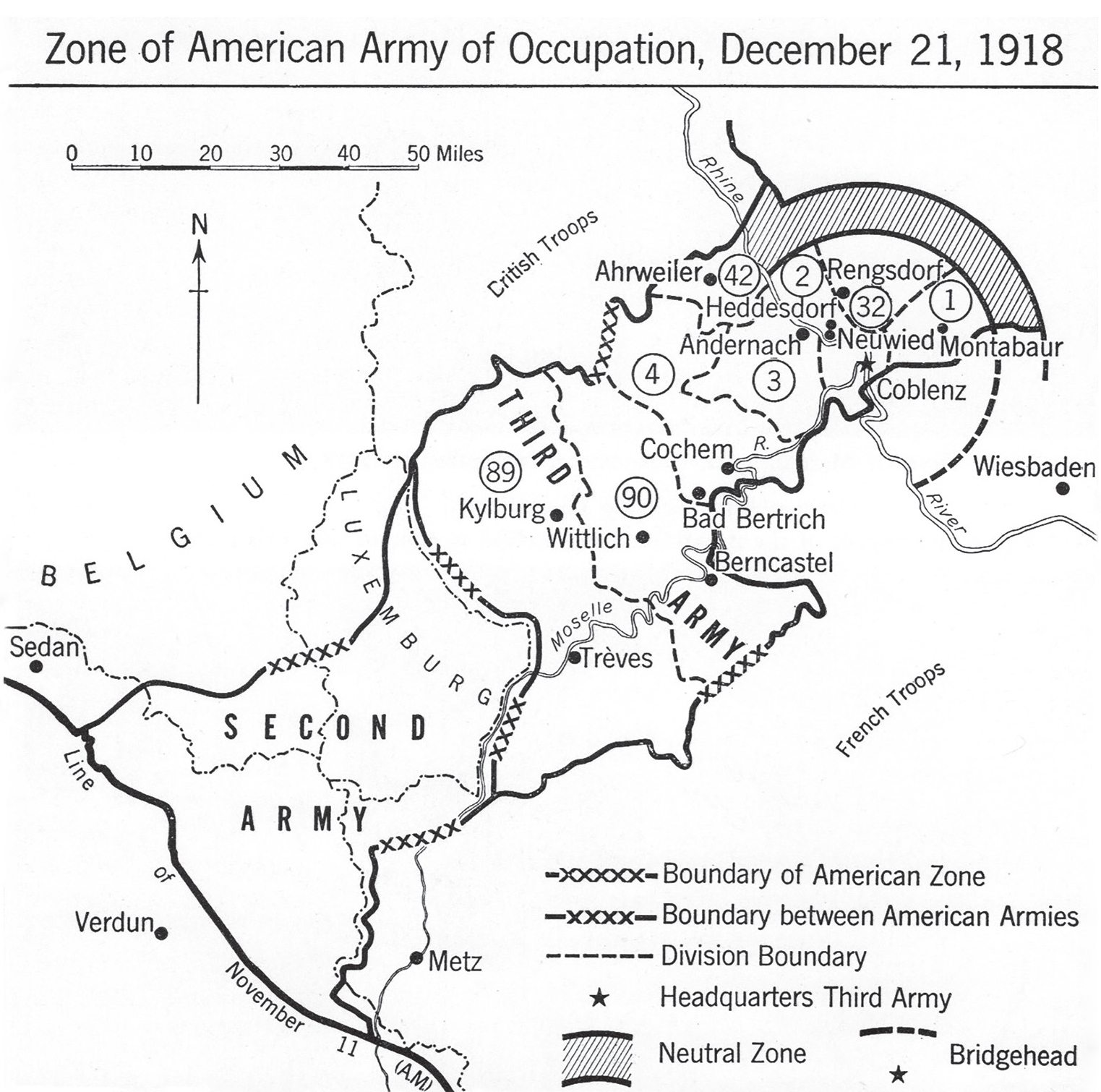

This period map shows the four Allied occupation zones starting in the north with “B” for Belgian, “E” for English (Great Britain), “A” for United States, and “F” for French. The three semicircle bridgeheads across the Rhine River are clearly visible as is the neutral zone (in green). Karte von Rheinland und Westfalen und den angrezenden Ländern, c. 1920, author’s collection

General John J. Pershing’s directions to the Third Army were deceptively simple in wording, yet high in complexity: cease current combat operations, as- semble the Army, move it from the combat zone in France through Luxembourg and into Germany, establish an occupation in conjunction with the armies of three other nations, accept war reparations from the defeated enemy, and be prepared to resume combat operations at any time. Any one of these operations would be significantly difficult; together they were a real challenge. Keeping in mind that the Armistice of 11 November was not the actual end of World War I, but merely a truce to allow peace negotiations to take place, the mission of the occupying forces was quite complex and challenging.

Pershing addressed the soldiers and Marines of the Third Army:

There remains now a harder task which will test your soldierly qualities to the utmost. Succeed in this and little note will be taken and few praises will be sung; fail, and the light of your glorious achievements of the past will sadly be dimmed Every natural tendency may urge towards relaxation in discipline, in conduct, in appearance, in everything that marks the soldier. Yet you will remember that each officer and each soldier is the representative in Europe of his people. Whether you stand on hostile territory or on the friendly soil of France, you will so bear yourself in discipline, in appearance and respect for all civil rights that you will confirm for all time the pride and love which every American feels for your uniform and for you.1

One of the key objectives of the American force was the seizure and control of all access to the Rhine River bridges within its sector. These included a pontoon bridge and a railroad bridge at Coblenz, as well as the railroad bridges at Engers and Remagen in Germany. To the north, the British Army and troops from their empire were similarly assigned to control the five bridges in the Cologne and Bonn area. The French Army would do likewise for the crossings in the area around Wiesbaden and Mainz. These same bridges were the starting points for the German invasion of Belgium and France in 1914, so the Allies recognized the need to secure them. As was proven in World War II, the Rhine serves as the natural western barrier in and out of Germany. Only an army in control of bridges across the river can easily traverse this barrier. Should the Paris peace negotiations break down, the Allies could use their strongly defended bridgeheads across the Rhine to swiftly deploy additional forces into the heart of Germany. The occupation zones also were designed to serve as the administrative areas for the acceptance of war materiels required by the Armistice to be turned over to the Allies by the German Army.

The American Zone

Under terms of the Armistice, an area of western Germany with a million inhabitants was assigned to the United States for occupation duty. The Third Army set up its positions in a sector running from the Luxembourg border to a semicircular section on the east side of the Rhine River, soon known simply as the Coblenz Bridgehead. The area of Germany the Americans occupied was predominantly conservative in politics and Roman Catholic in religion. There were only two large towns in the American zone: Trèves with a population of 45,000 and Coblenz with 65,000.2 The Grand Duchy of Luxembourg also fell under American control for a short period.

Originally, only the French and Belgian governments insisted on the occupation of an area of Germany as a key provision of the Armistice. Following much debate and discussion, the Americans and British finally agreed and directed their military staffs to participate in the planning. Meanwhile, after intense negotiation among the Allied representatives, the terms of the Armistice, which now included the occupation of the Rhineland by the victorious forces, were finally agreed upon. Paragraph V of the 11 November 1918 Armistice agreement stated that “the [portion of Germany on] the left bank of the Rhine shall be administered by the local authorities under the control of the Allied and United States armies of occupation.”3 Historically, the United States’ colonial experiences in the Philippines, Mexico, and the Caribbean had shown that the supervision of a civil government by an occupying force may be either strict or loose, depending on the level of compliance or hostility of the local population. In the case of the German Rhineland, the original intent was to follow a loose style of supervision because of America’s earnest desire to not interfere with German customs or institutions. However, as with the leaders of the other occupying armies, the security and safety of American troops was just as important as their administrative duties in the zones. If mistakes were made, the Allies were determined to err on the side of safety to protect their troops.

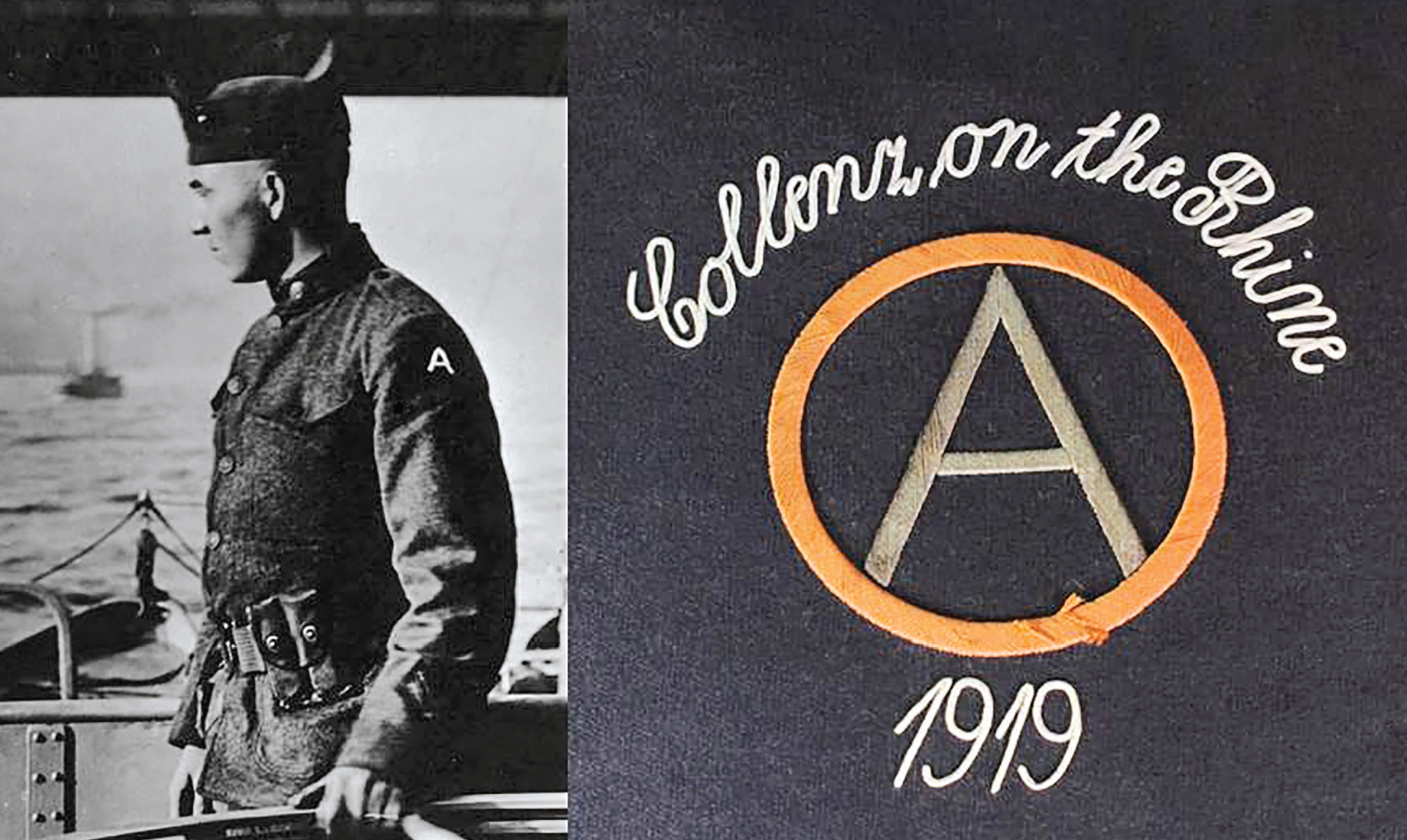

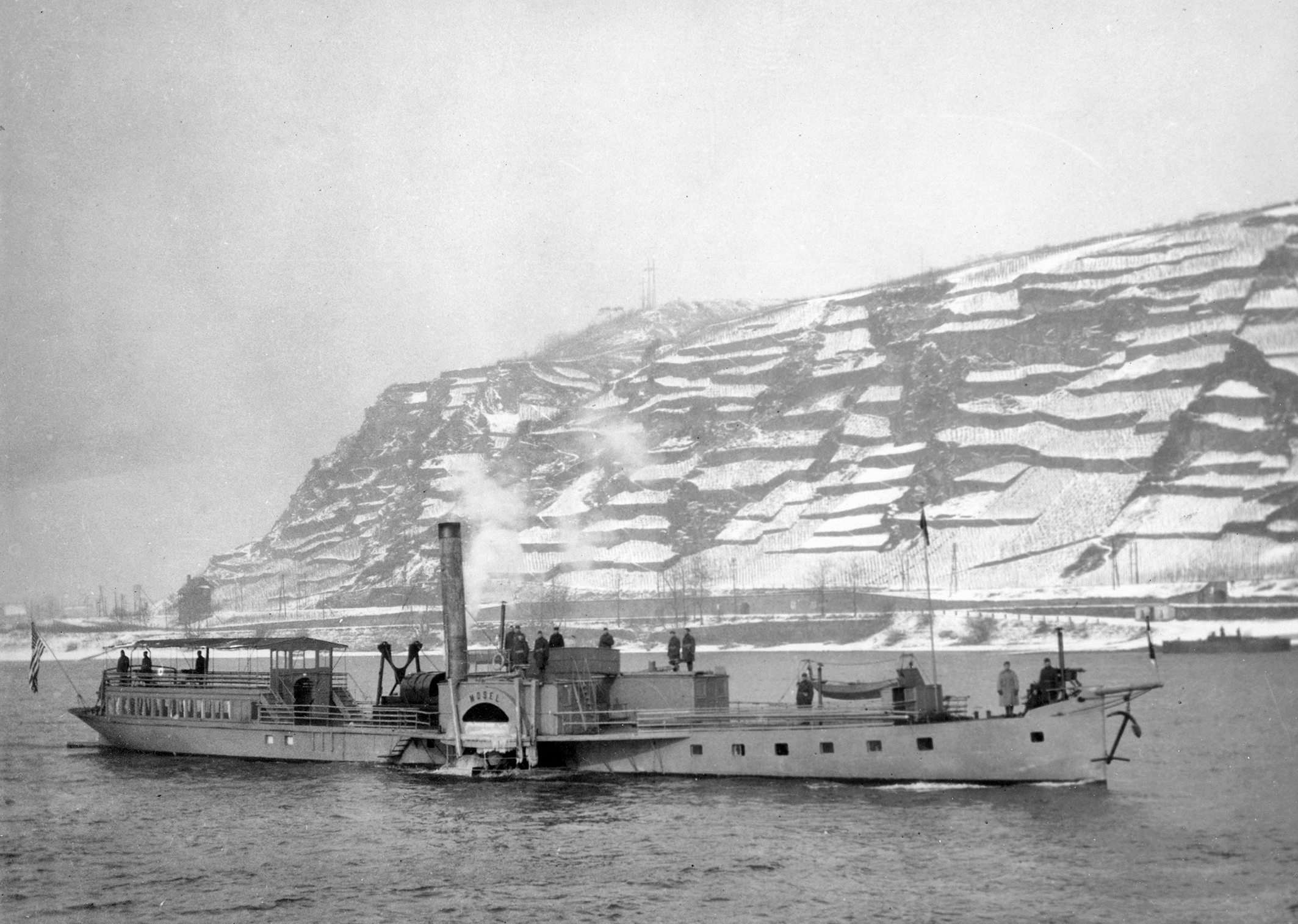

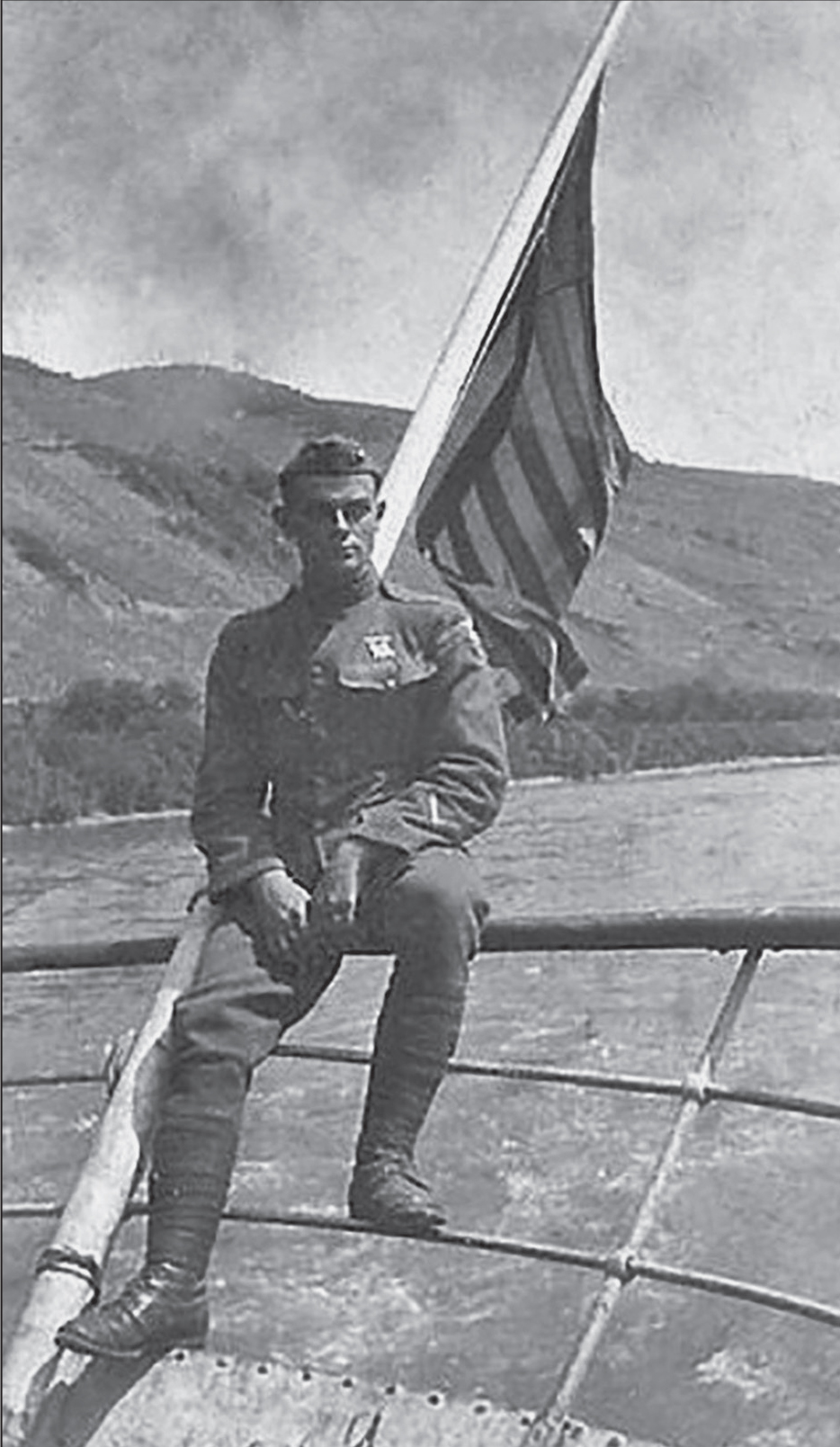

Cpl Edward J. Donnelly of the Marine Rhine River Patrol, seen here on 11 January 1919, pilots the SS Mosel. While most of the 4th Brigade Marines wore a version of the 2d Division patch, the members of the Marine patrol wore the Third Army’s “Army of Occupation” shoulder patch. The banner displayed here shows clearly the “A” inside the “O,” symbolizing the Army of Occupation.

Strict rules against fraternization were published and enforced by the military police. Due to the very nature of military and civil administration of the occupied areas, the Third Army soon found it impossible to avoid interference in local matters that were not strictly within the realm of “security.”4 What was not clear or precise in the Armistice was the definition of “local authorities.” Equally unclear was the meaning of “under control.” These ambiguities led to complications of many kinds and, at times, almost set the two sides back at war with each other. Making a bad situation even worse, each Allied nation had its own national agenda, and therefore, a differing approach on exactly how to conduct an occupation. After some 19 months of war, the German and American people had reached some conclusions about each other; now they were going to meet, not separated as before by the barbed wire of no-man’s-land, but face to face in the very heart of Germany’s historic Rhineland. As a Third Army civil affairs officer noted simply: “The average soldier looked forward with curiosity to seeing Germany.”5 First, however, they had to get there.

Organization of Third Army

When the AEF commander, General Pershing, received notification of the occupation requirement, he selected his occupying force from among the 29 intact combat divisions in the AEF.6 Realizing the potential for danger and the inherent complexity of the operation, he chose the best units, specifically, four Regular Army divisions: the 1st, the 2d with its Marine brigade, the 3d, and 4th. From the National Guard divisions, he selected the 42d Division (Rainbow Division) and the 32d Division from Michigan and Wisconsin, whose members became known as the “Gemütlichkeit boys” because so many of them spoke German.7 From the National Army divisions, he added the 89th Division, originally formed with men from Missouri, Kansas, and Colorado, and the 90th Division, whose men were drawn primarily from Texas and Oklahoma. These eight divisions now comprised the Third Army, commanded by Major General Joseph T. Dickman.8 Their distinctive patch, designed for the Third Army, was a capital letter “A” inside the letter “O,” symbolizing the “Army of Occupation.”

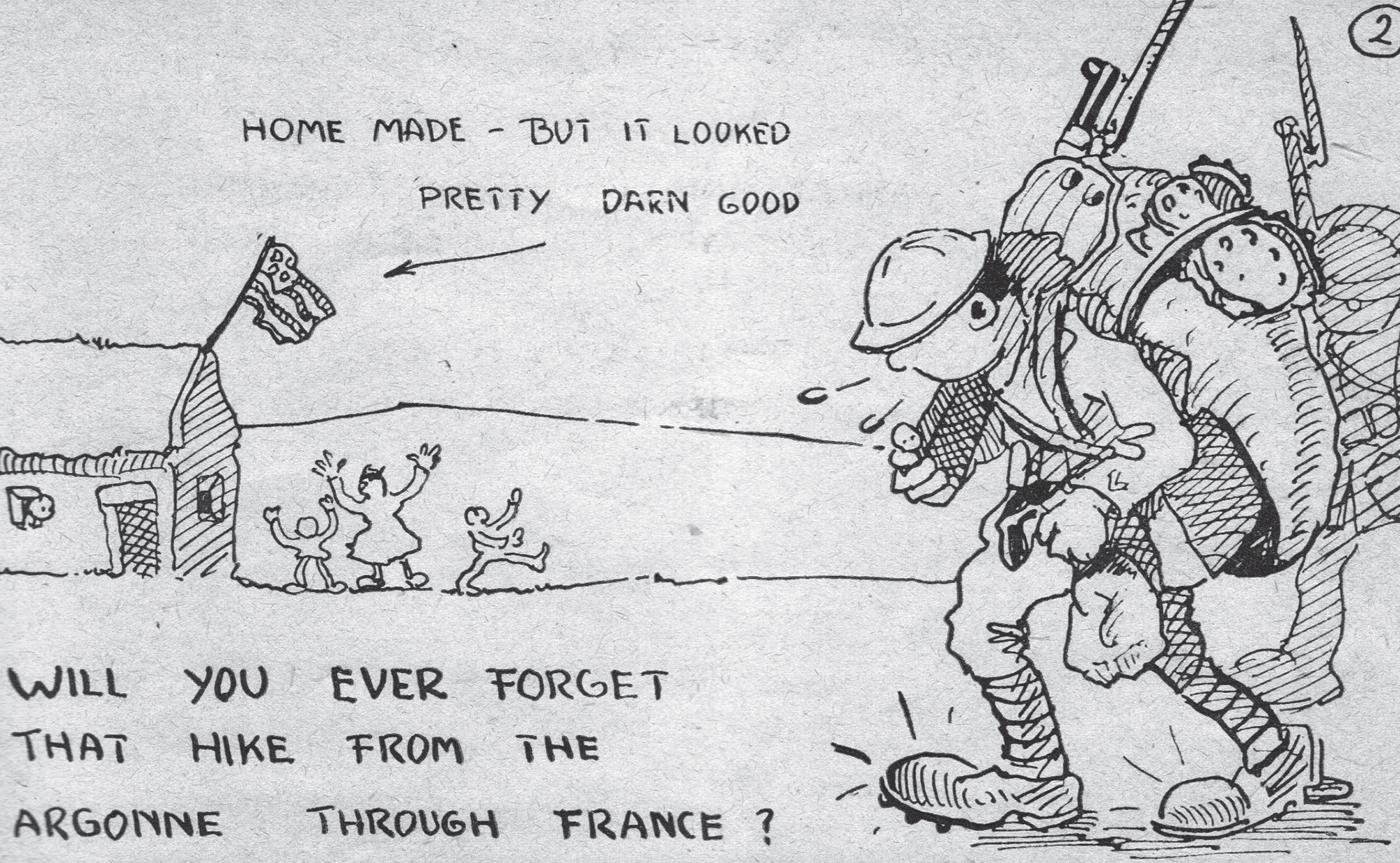

American doughboy humor reflects the hardships of the hike from France through Belgium and Luxembourg into Germany. As tired as they were from the march, many of the doughboys found the local versions of the U.S. flag entertaining. “When I was in Germany” cartoon pamphlet, c. 1919, author’s collection

Receiving notification of their new mission as part of the Third Army almost immediately after the end of the fighting on 11 November, the selected divisions had only a few days to prepare for the move. Some of the units, those farthest from the intended occupation zone, would have to travel some 300 kilometers. Other units had shorter distances to cover, but for all participants, it was going to be a long march. Following on the heels of the retreating German Army, Third Army units began their advance toward Germany on 17 November 1918 and crossed the borders of Belgium and Luxembourg. Soon the roads between France, Belgium, Luxembourg, and Coblenz were filled with 250,000 American doughboys and all of their equipment. To the north, elements of the British Army marched toward Cologne, and the Belgian Army advanced toward Aachen. To the south of the Third Army, the French forces headed toward their sector, which was centered on the cities of Wiesbaden and Mainz. Under the guiding provisions of the Armistice, the victorious armies moved in stages, conscious at all times of the potential for renewed warfare. The Armistice did not permit crossing the German border until 1 December, and this allowed the units to take organized pauses to rest their animals, care for their sick soldiers, and refurbish some of their equipment.9

To the Rhine

As the Third Army crossed into Luxembourg, AEF headquarters announced a policy of noninterference in the affairs of the Grand Duchy. Shortly thereafter, a French general in Luxembourg City was placed in charge of all troops in the Grand Duchy by the Commander in Chief of the Allied Armies, Marshal Ferdinand Foch. Pershing issued instructions that this order did not apply to his U.S. troops, and they would not be subject to French control. Maintaining American independence of command in the Grand Duchy was extremely important because, not only would the Third Army’s route of march and logistical support pipeline run through Luxembourg, some U.S. force—the 5th and the 33d Divisions—were to remain within its borders protecting that pipeline. Marshal Foch, in response to the action by Pershing, resolved the issue by placing the entire Grand Duchy in the American zone.10

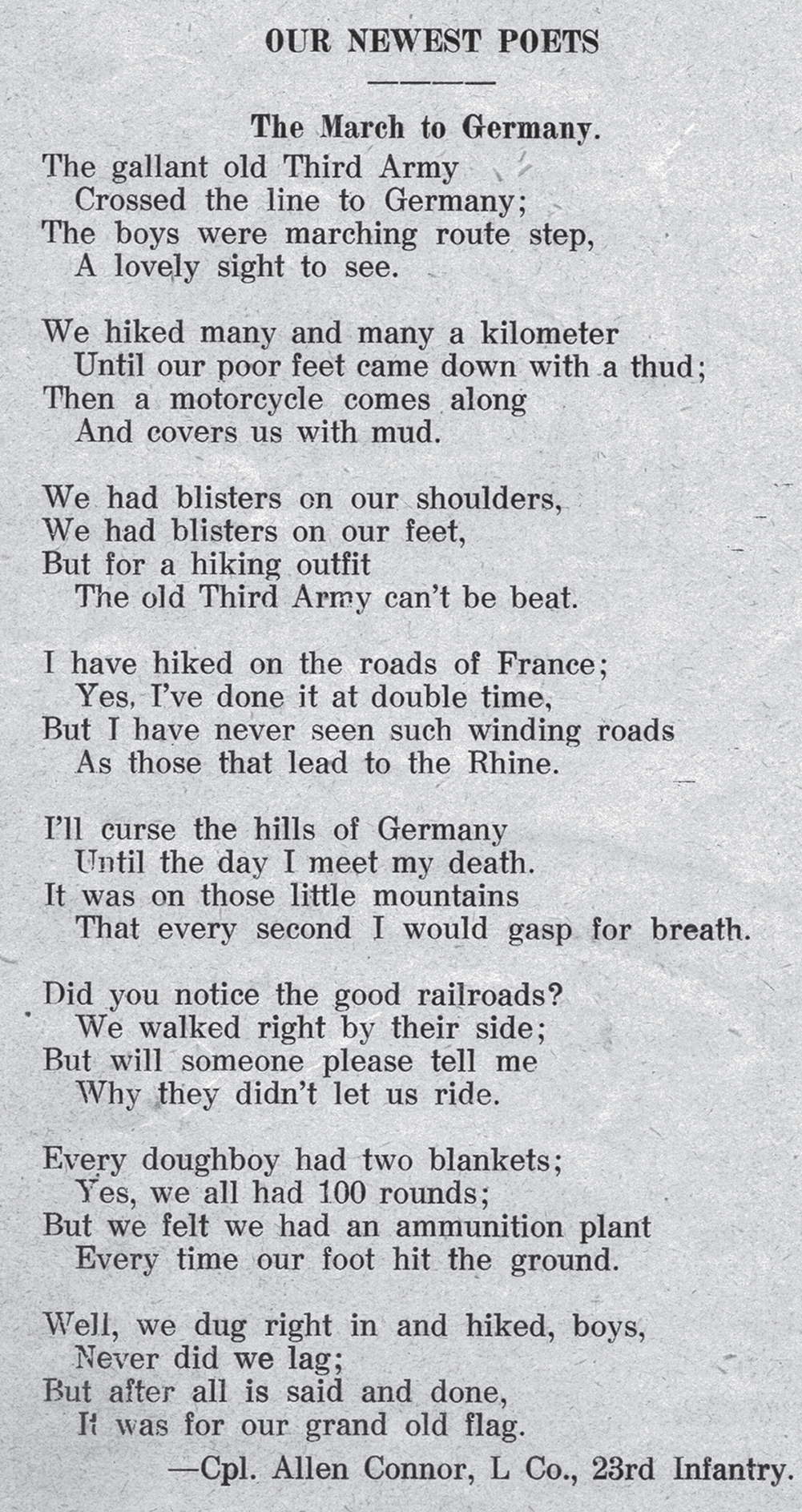

Written by a 23d Infantry Regiment soldier and printed in The Indian, this poem reflects the difficulties of the hike into Germany for the soldiers and Marines of the 2d Division. The Indian magazine, author’s collection

Meanwhile, the march continued, and the daily reports from the Third Army back to AEF headquarters in Chaumont highlighted the problems advancing forces were having. Being unable to accurately fix the location of the German forces and the confusion caused by the revolution that was sweeping throughout Germany made it difficult to provide a clear picture of the movement. The 18 November 1918 U.S. Army report noted:

The march of the Third Army to the Rhine has been resumed one day in advance of the pre-arranged schedule owing to the lack of established authority in the region being evacuated by the enemy. The latter is having difficulty in complying with the terms of the armistice because of the limited number of roads available for his withdrawal across the MOSELLE and SURE [SÛre or Sauer] Rivers.11

In addition to the German Army having problems moving its units out of the occupation zones, some Germans also went out of their way to make it more difficult for the advancing Americans by cutting telegraph lines and shooting holes in water tanks.

As the various units of the American force passed slowly through France, Belgium, and Luxembourg, the doughboys were pleasantly surprised by the warm welcome they received. The areas previously occupied by the Germans were particularly festive. Once across the German border, however, the march took a different tone altogether. Victory flags and pretty girls waving from the windows of the liberated towns of France and Luxembourg gave way to shuttered windows and deserted streets.

By 26 November, most of the Third Army’s advance units reached the German border and stopped. The Allied troops previously decided to cross the German border on 1 December simultaneously. The pause was welcomed by the soldiers and Marines as it gave the supply sections a chance to bring up badly needed cold weather clothing and rations. It also allowed medical personnel to treat some of their sick rather than evacuate them to hospitals.

At 0700 on 1 December 1918, with the 5th Regiment commanded by Colonel Logan Feland in the lead, the Marines of the 4th Brigade crossed the Sauer River near the town of Neidersgegen into Germany. Now fully aware that they were on enemy soil, the previously cased regimental colors and guidons were unfurled to allow the Germans to see who was marching through their country.12 For the most part, the advancing Third Army passed through seemingly deserted small towns and villages as most of the Germans chose to remain inside, perhaps fearful of drawing attention after the rumors spread by defeated German soldiers. Some of the disorganized German units retreating earlier along these same roads had “taken a considerable quantity of foodstuffs without paying for it, excusing their actions by saying: ‘The Americans, who are the biggest robbers in the world, will take it anyway when they come’.”13 With both Americans and Germans appearing to be on their best behavior, the march continued on a wide front through the Moselle Valley west of the Rhine. One Marine of the 6th Regiment wrote home: “I don’t know just where [we are] but can guess close enough. Ten of us are staying tonight in an old lady’s house. We had nice feather beds with clean sheets and everything . . . she set out a huge bowl of beef soup, a large platter of fried spuds, liverwurst about a yard long, good old rye bread [and] coffee. We sure did eat.”14 In spite of the good conditions, the Marines remained aware of the fact that they were in enemy country. The Marine ended his letter by saying he had to close because he had to go on guard duty for the night.

This illustration shows the location of the American divisions (in circles) in the U.S. occupation zone. The first division to redeploy to the states was the 32d Division, which was located on the east side of the Rhine. With that departure, the 1st and 2d Divisions expanded their areas to cover the entire sector on the east side of the Rhine. Official U.S. Army photo.

Once past Trèves, the terrain became more difficult, and the combination of frozen roads and heavy loads took their toll on the troops. Usually marching for 10 hours a day, with hourly 10-minute breaks, the Marines of the 4th Brigade managed to keep the required separation zone between the German forces and themselves. By the time the Americans were 80 kilometers inside Germany, the troops in the lead divisions were feeling the strain of hiking through rain and snow on frozen roads. Adding to the distance was the fact that there were few straight roads due to the Moselle Valley geography. Instead, curving, switchback roads were the norm, and the troops marched much farther than the straight-line distance on a map would indicate. Later reports commented negatively on what appeared to be a straggling problem in the Marine brigade. Approximately 1,000 replacements intended for the 4th Brigade joined their units during the march. Unfortunately, many of these men had arrived recently in France and were not prepared for the arduous journey to Germany. An observing officer noted at the time that “more men fell out on this hike than on any other. Most of these men were new replacements who had joined the brigade in and near Arlons, Belgium.”15 Lieutenant Colonel Hugh Matthews, assigned to the 2d Division staff, later wrote that the replacements had made a daylong march just to catch up to the Brigade and that the

replacements had no equipment other than the personal equipment of the soldier and their reserve rations . . . after a conference at Division Headquarters, it was decided on account of the foot-sore condition of the replacements, to send back machine gun trucks and ambulances to bring up the replacements so that they might join their organizations and be ready to resume when the march was again taken up During the 19th a number of machine gun trucks from the Fourth Machine Gun Battalion and ambulances from the Sanitary Train were utilized to bring up the Marine replacements, repeated trips being necessary to effect this. By the evening of the 19th all the replacements had been turned over to the Fourth Brigade and resumed the march . . . the morning of the 20th.16

Another Marine officer, Major Franklin B. Garrett, the 2d Division staff officer in charge of the mission to pick up the replacements and take them to the brigade, gave a more detailed version. After receiving his orders, Garrett quickly found out that even the brigade headquarters did not know “which of the many roads the replacements had taken.” Finally getting in contact with the lead element of the replacements, he found the detachment “strung out all along the line for many miles back.” After gathering the replacements in a central location, Garrett made an assessment of their condition. Many of the men were so exhausted or had such bad foot problems that they were unable to continue the march. Contacting the 4th Brigade Headquarters, he reported to Brigadier General Wendell C. Neville, the brigade commander, “of the condition the men were in and suggested that transportation be furnished as [he] did not think these men would ever catch up by hiking.” A short while later, the trucks from the 6th Machine Gun Battalion and the ambulances from the sanitary train arrived to carry the men forward.

Garrett later reported that “the spirit of these men was wonderful. Their one desire seemed to be to join up with the [4th Brigade] column. For green replacements they had covered a remarkable distance. . . . Many of them had continued hiking with feet so badly bruised that only Spartan courage and Marine grit could have brought them as far as they had come.”17

Significantly, another Marine officer mentioned having to find accommodations for the replacements prior to them joining up with their assigned units in the 4th Brigade. He stated that he “finally made arrangements with a local priest to put 800 of the men in a convent” and the remainder in a local school. Due to the massive movement of U.S. forces through the area during this period, the officer further explained that billets were so difficult to obtain that he, himself, “was unable to get a billet and slept on a table in a café.”18

Still the Third Army continued, making staggered stops and starts, but always pushing eastward with the 1st, 2d, and 32d Divisions leading the way. These three divisions, under control of III Corps, were the lead elements and had the farthest distance to travel. Ultimately, their trek led them over the Rhine to sectors on the far side of the river. As the 2d Division moved eastward, the 5th and 6th Regiments alternated serving as flank guard and advance guard. Early in the march, the left flank was covered by French Army units, but they soon moved southward and headed for their occupation sector near Mainz. Their place was taken by British soldiers, who maintained liaison with the Americans the rest of the way to the Rhine.

In this unique view, Pvt Clinton Vann Peck, 97th Company, 6th Regiment, cleans his rifle in preparation for a unit inspection. This photo was likely taken at the rifle range established in the 2d Division sector near Leutesdorf, Germany. Photo courtesy of the Peck family

The 330 kilometers from the Argonne that some of the units travelled was a struggle for the doughboys in the second echelon also. Following the lead divisions, they were able to occupy previously used billets, but found the roads even more torn up by the passage of the leading units. Army Sergeant Bert A. Fidler, an experienced combat veteran from the 39th Infantry Regiment, wrote his father that “I will not mention the fourteen days hike from the Argonne woods to Coblenz, making anywhere from twenty to fifty-four kilometers a day with full field equipment. I couldn’t begin to express my feelings.”19 Others in the 4th Division were not so reticent, referring to what they called the “Hobnail Express,” where “everyone agrees that it was a corker from any point it might be considered.”20 Ironically, Marine Private Clinton Vann Peck, one of Sergeant Fidler’s best friends from Syracuse, New York, was making the same hike as part of the 6th Regiment. In a hurriedly written letter to his mother, Peck wrote: “I suppose you read much now days about the Victorious march to the Rhine. It is much nicer to read about than to do as we are now doing. It is sure tough hiking. We march all day and then stop overnight in barns and houses.”21

As noted, one requirement of the Armistice was to keep 25 kilometers between the advancing Allied forces and the retreating German Army. Maintaining this interval was a struggle for the Americans because they seldom knew the exact location of the German Army to their front. As German forces withdrew from the western front, they were required to pass certain delineated, numbered geographic lines on definite dates. These “phase” lines and the dates for reaching them were written into the Armistice documentation and had been determined by staff officers in the comfort of warm and dry headquarters buildings. However, with road conditions deteriorating quickly due to the weather and heavy traffic, meeting the published march schedule proved to be a difficult task for both sides.

As the American Army crossed the German border, some of the second and third echelon units dropped out of the march and set up in their assigned sectors. The other units continued on through the rain and mud toward the Rhine.

The Watch on the Rhine

On 11 December 1918, all of the Allied forces reached the Rhine. After another short reorganization period, they crossed the river in large numbers on 13 December to establish positions on its eastern shore.22 The Marine brigade, still serving as the extreme left flank of the Third Army, crossed the Rhine led by the 5th Regiment via the Ludendorff Railroad Bridge at Remagen, a site that assumed even greater significance in the next world war. On their left flank, the Marines made contact with the Canadian Corps, which represented the extreme right flank of the British zone.

When the main U.S. force arrived, the headquarters of the Third Army was established in Coblenz in a large German government building complex located on the waterfront on the west bank of the Rhine. Crossing to the east side of the Rhine, the U.S. III Corps, comprised of the 1st, 2d, and 32d Divisions, took up positions within a large semicircle, 30 kilometers (18.6 miles) in radius, guarding the Rhine River bridges they had crossed.

Among the primary duties of the 4th Brigade was maintaining control of the neutral zone, the 10-kilometer-wide barrier between unoccupied Germany and the Allied zones. BGen Wendell C. Neville poses on the edge of the neutral zone with two enlisted Marines and another officer. HRB, Marine Corps University

To keep the Allied armies and the German Army apart, a 10-kilometer (6.2 miles) strip was established. It ran from the Netherlands to the border of Switzerland and served as the demilitarized zone between the Allied zones and unoccupied Germany. This region was designated as the neutral zone. Germany was allowed to keep civil police forces in the towns of the neutral zone: however, they were not allowed to make any infrastructure changes or improvements. This meant the Germans were not allowed to fix roads, upgrade railroads, or run telephone lines without permission from the French, who were the nominal overseers of the entire neutral zone. The German Army was allowed to enter the zone in small numbers, if necessary, to assist local police with riot control. No recruiting for the German Army was allowed in either the neutral zone or in any of the Allied occupation areas.23 In addition to these restrictions, hunting and fireworks also were forbidden. Obviously, the Allies feared the danger of sneak attacks coming out of the zone and so the Armistice terms included these restrictions to ensure they did not happen.

One potential problem for the Allied armies during the occupation was the presence of a very large, unoccupied Germany just to the east on the other side of the neutral zone. There were still many proud and angry Germans who believed the war should not have ended as or when it did. Therefore, aggravating or provoking the Allies and their occupation armies served as a viable and valid means to continue the conflict. Maintaining oversight of their portion of the neutral zone to keep potential troublemakers out of the American zone soon became an important part of the Marine brigade’s mission.

West of the Rhine

Remaining on the west bank of the Rhine was IV Corps with the 3d, 4th, and 42d Divisions. The U.S. VII Corps, made up of the 89th and 90th Divisions, occupied the Moselle Valley from Trèves west to the Luxembourg border.24 As expected, the arrival of the U.S. Third Army was a cause for uncertainty in the local population because the attitude of the Ameri- cans toward the Germans was unknown. General Pershing attempted to alleviate the local citizens’ fears by proclaiming, “The American Army has not come to make war on the civilian population. All persons, who with honest submission act peaceably and obey the rules laid down by the military authorities, will be protected in their persons, their homes, their religion and their property. All others will be brought within the rule with firmness, promptness and vigor.”25

Along that same line, just before the arrival of the first American forces, Coblenz’s Burgomaster (Mayor) and Police Director Bernhard Clostermann announced to the German population: “We are informed by the American Commission that the civil life will not be disturbed. Under the condition, however, that not the slightest disturbance to public order and security occurs.”26 Despite these assurances from the U.S. Army, American forces soon issued regulations for their occupation zone that banned public gatherings, severely restricted long-distance telephone communications and outdoor photography, censored the press, and even required detailed reports from the owners of carrier pigeons. With these edicts, General Dickman and his staff regulated a broad range of social and economic aspects of life for the occupiers and the occupied in the American zone. The Americans were determined to let everyone know who was in charge in the Coblenz Bridgehead.

Although preliminary planning had been quite limited, the AEF had wisely decided that officers designated for civil affairs duty would accompany and assist the commanders of combat units into their designated zones of occupation. This freed the unit commanders to focus their attention on the disposition of their units and to make preparations for combat operations should that be necessary. Operating in the towns and local regions of the American zone, the officers in charge of civil affairs had responsibilities that far outstripped any training they received. Their administrative duties eventually included supervision of the German police and local jails, liaison with the local government officials, the conduct of provost marshal courts, control of the movement of all civilians in their area, and respond- ing to complaints by local civilians against the military. Other duties included the surveillance of local food and fuel supplies, supervision of public utilities, and oversight of the local political scene.27

The Marines of the 4th Brigade carried out many duties, one of which was to furnish mail detachments and guards. Here, one group from 6th Marine Post Office Detachment (APO 710) poses with their U.S. mail sacks. Photo courtesy of the Mark Sanders collection

Marines of 1st Battalion, 6th Regiment, on winter maneuvers in the hills around Segendorf, Germany. Photo courtesy of NARA (Ref #127-N-520522)

For their part, the soldiers and Marines of the 2d Division were kept in a constant state of vigilance and training in which “outpost positions and patrols were established, and a strict guard maintained.”28 Almost immediately after arrival in their designated sector, the Marines of the 4th Brigade conducted a series of training exercises to maintain their hard-won combat skills, while integrating the new Marines into their units. Construction of a rifle range also was high on the list of priority projects and was quickly completed. Another group of Marines was assigned to mail duty and served in the 2d Division’s APO 710 Mail Detachment on the east side of the Rhine.29

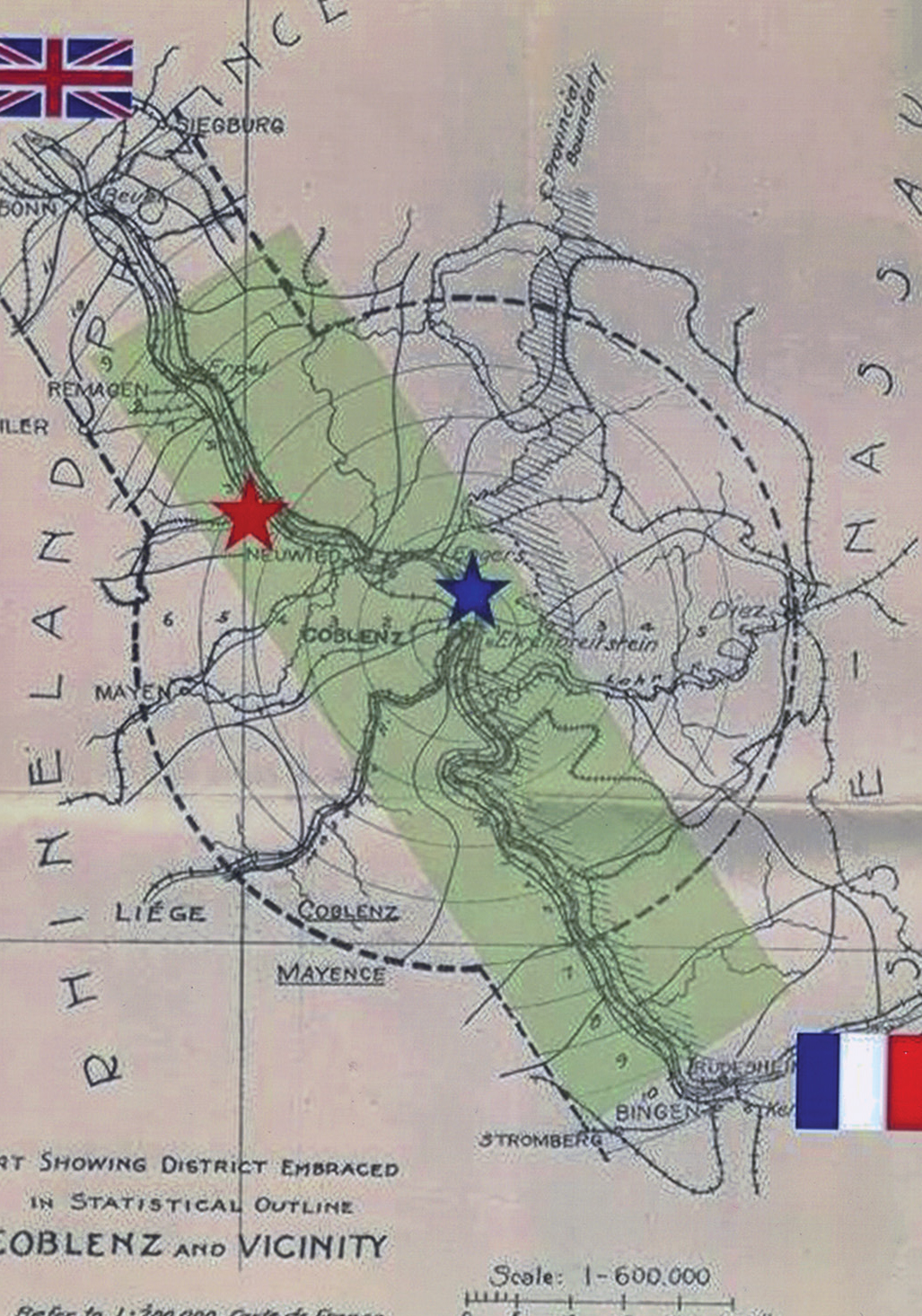

The patrol zone for the Marine Rhine River Patrol extended from Remagen, Germany, in the north down to Bingen in the south. The Marine patrol boats regulated river traffic and enforced the terms of the Armistice. The Marine patrol headquarters at Andernach is shown with a red star and the Third Army headquarters at Coblenz is shown with a blue star. Map courtesy of 1st Division Museum at Wheaton, IL. Overlay graphics by author

The Rhine River Patrol

During this period, the Marines also drew a mission that was greatly to their liking. Known as the Marine Detachment, Rhine River Patrol, Third Army Water Transportation Service, they were assigned to work for the Inter-Allied Waterway Commission. An original agreement between the Allied Armies had called for the British and French to maintain the river patrol for all of the occupied zones. Subsequent discussion led to the agreement being rescinded and the Americans were assigned to patrol a portion of the river. Thus, the Marines drew the assignment.30 Estimates of German commercially operated boats on the river ranged at more than 12,000 vessels, including a number of sailing ships and barges. At any given time, there were almost 35,000 sailors working on these boats. Some ocean-going cargo ships were able to navigate the Rhine as far south as Remagen before the river became too shallow for them to operate. Obviously a workforce this large, operating vessels that could sail from Rotterdam in the north all the way through the Allied occupied zones to Mannheim in the south, would require strict monitoring and military oversight.

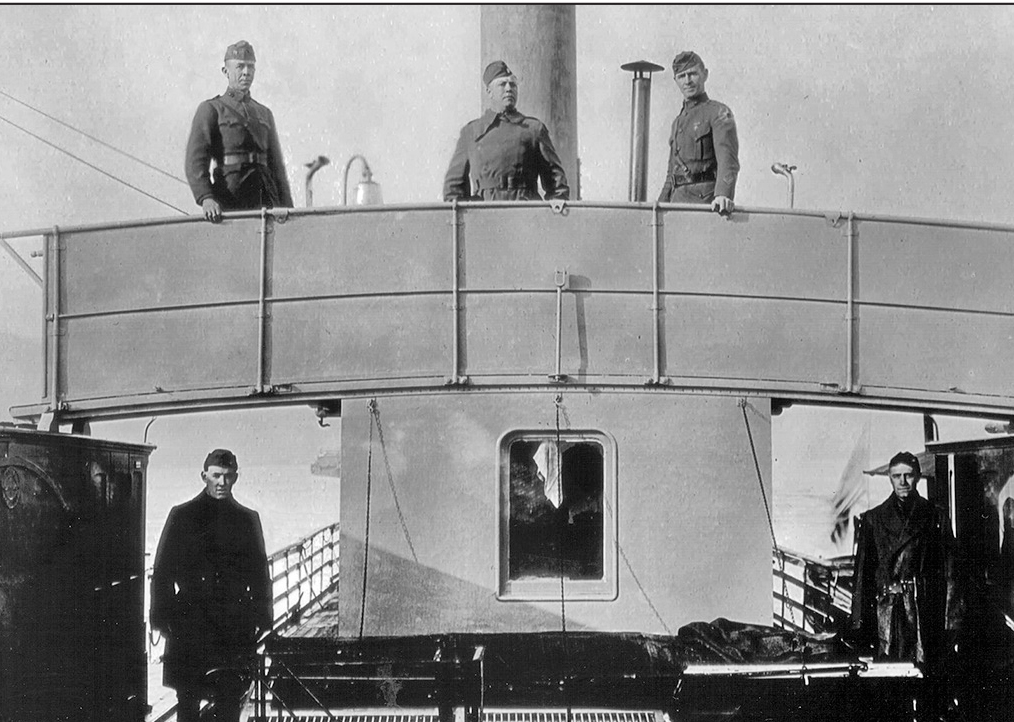

The Mosel, under the command of Capt Gaines Moseley, was a real workhorse for the Marine river patrol. It fea- tured several mounted machine guns, and its crew included several Marines from the 6th Machine Gun Battalion. HRB, Marine Corps University

The bridge of the Mosel with Capt Moseley on the left, Capt A. G. Chase in the center, and 2dLt Vernon Bourdette on the right. On the deck below them stand two enlisted members of the crew: Pvt J. F. Hoffman and Pvt H. S. Yarbrough. HRB, Marine Corps University

One of the clauses of the Armistice forbade German policemen in the four occupied zones from carrying weapons. The need to maintain the blockade of Germany, the threat of river pirates and armed smugglers, as well as fear of Bolsheviks using the river to transport weapons, meant that an armed force would be required. The obvious solution was to establish the river patrol by using armed Marines in confiscated German patrol boats. Marines from the 5th and 6th Regiments and the 6th Machine Gun Battalion were assigned as boat crewmen manning the deck cannons and machine guns. Using these boats, they regulated river traffic, performed courier and escort duty, and arrested smugglers on the 30-mile stretch of river from Rolandseck in the north down to the Horchheim railway bridge, which was just south of Coblenz. The French Rhine River Patrol was responsible for the section of river from Horchheim down to the southernmost part of their sector near Mainz. However, the section of river from Horchheim to Bingen was under the nominal command of American forces, although the French ships patrolled it. Therefore, French patrol boats were a common site in Coblenz.

The American Rhine River Patrol fleet consisted of 14 boats, manned by 8 officers and 190 enlisted Marines (table 1). From 18 December 1918 to 1 March 1919, Captain Robert H. Shiel commanded it. He was succeeded by First Lieutenant (later Captain) Lloyd A. Houchin, who led the detachment until 8 July 1919. Perhaps the most unique member of the American river patrol was not a Marine, but a 16-year-old American named Joseph Frengar. Originally from Lincoln, Nebraska, Frengar had been trapped in Germany during a visit with German relatives at the outbreak of the war. He eventually encountered the American Army near Trèves as they marched into Germany in 1918. At first a mascot of a military police unit, he ended up in Coblenz after their redeployment to the United States. The Red Cross representative in Coblenz introduced him to the executive officer of the Rhine River Patrol, Lieutenant Houchin, who added him to the crew of the SS Rheingold.31

Table 1. U.S. Rhine River Patrol ships and stations

|

Ship/station

|

Commander

|

|

SS Mosel (1872)

|

Captain Gaines Moseley

|

|

SS Preussen (1902)

|

First Lieutenant William L. Harding Jr.

|

|

SS Rhein (1899)

|

First Lieutenant Harold W. Whitney

|

|

SS Borussia (1912)

|

Second Lieutenant Guy D. Atmore

|

|

SS Elsa (1904)

|

Second Lieutenant Morris C. Richardson

|

|

SS Rheingold

|

Second Lieutenant Morris C. Richardson

|

|

SS Albertus Magnus

|

Second Lieutenant George R. Rowan

|

|

SS Frauenlob (1902)

|

Second Lieutenant James E. Stanners

|

|

Stadt Düsseldorf Station

|

Second Lieutenant Elmer L. Sutherland

|

|

Andernach Station

|

Second Lieutenant Louis Cukela (18 December 1918 to 22 March 1919)

Second Lieutenant John T. Thornton

|

|

Remagen Station

|

Second Lieutenant Vernon B. Bourdette

|

Note: The command of some of the river patrol boats changed fairly regularly—the Elsa, Frauenlob, Borussia, Rheingold and Albertus Magnus in particular changed hands several times. Source: Edwin N. McClellan, “Fourth Brigade of Marines,” Marine Corps Gazette, December 1919, 363.

The largest of all the boats was the SS Preussen, formerly the official vessel of the Rhineland uberpräsident, the Rhineland’s equivalent of governor. The Preussen was used by Major General Dickman on his inspection tours of the bridgehead.32 The Pruessen had a working crew of 29 Marines and six Germans and was heavily armed with two 37mm cannons and six machine guns. In addition, the Preussen was noted for having “graceful lines and [an] elaborately laid out and beautifully paneled saloon, cabins and dining room.” Among the first things the Marine crew did, after cleaning her “filthy spaces” was to repaint her to “battleship gray.”

The SS Mosel (Moselle) was the second largest of the vessels and was the first boat of the Marine patrol to fly the American flag on the Rhine River. Its trial run was conducted on 20 December 1918 and performed well enough to be accepted by the Third Army for use on the river.33 Also armed with machine guns, the Mosel carried “a sufficiently strong body of men to cope with any disturbances ashore.” It was primarily used as a supply boat for carrying provisions for the patrol stations and troops stationed along the river. The SS Mainz (1904) was used by the members of the Inter-Allied Waterway Commission in the performance of their regulation of commercial river traffic. There was a houseboat, usually stationed at Andernach, which served as the brig or guardhouse for lawbreakers brought in by the river patrol. The city of Andernach also served as the central headquarters for the Marine patrol; it shared a building with the 3d Division’s post office a short distance from the river. At the time, Andernach had one of the best-equipped river port complexes with its series of warehouses and five cranes for loading and unloading cargo.

In addition to the eight vessels named above, six other vessels were used, though unnamed, known simply by their hull numbers. Two of them had steam engines while the others were gasoline driven. Using these vessels, the Marines monitored most aspects of river traffic, including their most controversial arrest in January 1919.

It all started simply enough; two German citizens, Mathias Scheid and Jacob Ring, attempted to smuggle 700 cases of contraband cognac worth ₰1 million by boat from Oppenheim am-Rhein into Coblenz.34 The two men hid their illegal cargo under what appeared to be a full shipment of rocks and gravel. Unfortunately for the two, the Marines regulating traffic on the river that day grew suspicious. Very quickly, the Marines removed the layer of camouflage and found the bottles of cognac, as this alcohol was forbidden in the U.S. zone. After being arrested, the two pleaded not guilty to a number of smuggling and fraudulent documentation charges. They were found guilty after four days of hearings and were sentenced to hard labor for a year and a fine of ₰250,000. The punishment was later reduced by the Third Army commander, Major General Dickman, to six months hard labor and a ₰100,000 fine. Their trial was such a major event that it even received coverage in the 23 May 1919 Stars and Stripes published in Paris.

The headquarters for the Marine patrol was located in this building in Andernach on the west side of the river. The first commander of the headquarters detachment was 2dLt Louis Cukela, a Medal of Honor recipient and legendary figure in Marine Corps history. Author’s collection

Scheid and Ring were two of the wealthiest citizens in the American bridgehead area, and their arrest and subsequent trial were meant to show that the law was being applied equally to rich and poor. Viewed from a German perspective, it was seen as just another example of the harshness of American justice. One German wrote that “the American is very fond of large fines. I saw copies of the ‘Coblenzer Zeitung’ in which the lists of fines covered columns. No fines were less than 100 marks, and many of them mounted into the thousands. Two respectable merchants were given two years imprisonment and 200,000 marks fine for smuggling cognac and this sentence was ‘mercifully’ commuted to six months imprisonment and 100,000 marks fine.”35 Obviously, the nationality of the observer tended to color the spin put on the story. Nonetheless, the commander of the Third Army had decreed that no cognac would be sold in his zone, and the two smugglers received a six-month sentence in jail to let that message sink in.

Four Marines assigned to the Marine patrol enjoy some time off away from their boats. The varied clothing would suggest that this photo was taken early in the occupation before the supply pipeline ensured uniformity. Here, they are wearing Third Army patches, the standard insignia for Rhine River Patrol Marines. HRB, Marine Corps University

The house in which Pvt Peck was billeted in Rockenfeld, Germany. The owner of the house was a noted huntsman in the area, and Peck wrote home that the house was filled with antlers, horns, and “stuffed hawks, ducks, cranes, woodpeckers, and a fawn.” Photo courtesy of the Peck family

One of the more notable events took place in February when all of the Marine patrol vessels were assembled for the first time for a review by General Dickman. Joining Dickman on the Andernach reviewing stand was Franklin Delano Roosevelt, assistant secretary of the Navy. To maximize the effectiveness of the review, all the ships were filled with doughboys in Coblenz on R&R, providing them with a Rhine cruise and a chance to see their commanding general at the same time. Adding to the excitement, a squadron of aircraft from the nearby Weißenthurm airfield performed aerial maneuvers over the fleet. Among the aircraft were two German Etrich Taube (pigeon) planes, flown by U.S. Army pilots, providing for many of the doughboys their first view of enemy aircraft since the Meuse-Argonne Campaign.36 In spite of the continually inclement Rhineland weather, the Marines spent a great deal of time outdoors, securing the neutral zone and practicing to repel any attacks from unoccupied Germany. A member of the 4th Brigade commented on his living conditions by saying that “we, four of us, have a good billet now. The [German] people here are very good to us. . . . The old man here has a fine collection of [animal] horns. In our room there [are] 15 pairs and in the front parlor there are about 20 or more all sizes, also [stuffed] hawks, ducks, cranes, woodpeckers and a fawn”37 By April, life in the Marine sector was good. The German Army had completed its demobilization and much of the postwar tension had dissipated; although, it would prove to be only a short reprieve. Soon, the 2d Division would find itself again preparing for war.

The Treaty of Versailles

The period of lessened tension lasted only until late May 1919 when reports from the Paris peace negotiations indicated that the German government seemed to be dragging its feet about signing the final surrender documents. By this time, almost half of the original American occupation force had departed, leaving only the 1st, 2d, 3d, and 4th Divisions in Germany and the 5th Division in Luxembourg. The problem was quite simple: many German government officials considered the surrender documents and the peace treaty being negotiated in Versailles to be a second capitulation to the Allies. Fearing for their reputations and in an increasingly angry and violent postwar Germany, their lives, they were understandably hesitant to sign the documents. They chose instead to try to drag out the negotiations in hopes of obtaining less harsh terms.

This strategy became apparent to the Allies in May 1919. Just the opposite of Germany, they needed to settle these issues quickly so they could demobilize their armies which were consuming many of the resources necessary to restore their war-weakened economies. The Allies also needed to focus and redirect their energies to reshaping Europe’s map as the dissolution of the Austro-Hungarian Empire and the Imperial Russian Empire had created a number of violent border disputes in Central Europe. Hungary, Romania, Yugoslavia, and the newly merged country of Czechoslovakia, Lithuania, and Poland, just to name a few, all sought more land and population at the expense of their neighbors. Several of these flare-ups required the deployment of Allied troops to separate the warring factions. Equally draining were the Allied expeditionary forces that had been sent to Siberia and northern Russia to confront the Bolsheviks. Clearly then, to the Allies, something had to be done quickly before their own military strength melted away completely. Most of the 2 million U.S. soldiers of the AEF had already returned to camps in the United States for demobilization. Many of Britain’s soldiers had demobilized as well.

Due to German foot dragging, on 20 May 1919, Marshal Ferdinand Foch, the overall military commander for the Allied armies, directed the staffs of the French, British, Belgian, and United States armies to prepare operational plans that would move their forces out of their occupation zones and into unoccupied Germany.38 General Pershing’s headquarters instructed Third Army headquarters in Coblenz to begin the planning phase, and on 22 May, each of the five American divisions still on occupation duty received instructions that included the wording:

Should the enemy refuse or decline to sign the Treaty of Peace presented to him, the Allied and Associated Powers will renounce the present Armistice and resume the march of their armies into the enemy’s territory The purpose of this advance would be: to separate northern and southern GERMANY by the occupation of the valley of the MAIN; to reduce the enemy’s resources by the seizure of the RUHR industrial district; and to threaten his seats of government—WEIMAR and BERLIN. . . . All arrangements will be made to begin the advance by crossing the present outer limits of the bridgehead on or after May 30.39

The basic operational plan for the Americans was simple in design. Since the 1st and 2d Divisions were already occupying the bridgehead on the eastern bank of the Rhine, they would lead the American forces through the neutral zone into unoccupied Germany. The 3d Division, centered near Andernach on the west side of the Rhine, would move by foot, vehicle, and rail over the Rhine. One reinforced brigade (consisting of the 30th and 38th Infantry Regiments with associated engineers and machine gun battalions) of the 3d Division was detached from divisional command and placed directly under Third Army control. This brigade would move strictly by train and once across the Rhine would be used as a mobile force to support the advance. The 4th Division would remain on the left bank of the Rhine to maintain security of the river crossings. A French cavalry division would pass through the American zone and cross the Rhine to act as the link between the British Army and the American forces.

Soon after the plan was drawn up, Third Army also provided direction to III Corps and the leading divisions:

The corps will advance with its leading division transported on trucks in two main columns to reach the line FRANKENBERG-KIRCHHAIN on the first day of the advance. These columns will advance in combat formation well covered and connected by armored cars and motor patrols armed with rifles and machine guns. This division will seize and leave guards overall principal railway stations and junctions, important telephone and telegraph centrals, and all other sensitive points on the lines of communication east of the RHINE River. These guards will be as small as is consistent with safety so that the greatest possible strength of the division will be with the advance available for combat. The civil population of country passed over, especially those engaged in operating public utilities, will be required to remain in place and continue their functions.40

Thoughts of a renewed war were put on temporary hold in the Marines’ sector during the first week of June, when there was an unusual and deadly episode involving two Marines from 17th Company (commanded by First Lieutenant Augustus Paris), 5th Regiment. Privates Albert D. Dupree and Lauren W. Collier, two Marines with somewhat checkered pasts, became fed up with occupation duty and decided to see what was on the other side of the neutral zone. They loaded up their packs with field gear and a supply of soap and cigarettes. Avoiding the guard post, the two slipped through the demilitarized zone and then rode a train eastward until the first stop. After spending the night in a German hotel, they encountered three Germans who wanted to purchase some of their blankets. During the course of negotiations, one of the Germans asked the Marines if they had a pass allowing them to be outside of the American sector. The two privates responded by tapping their holsters, saying, “This is our pass.” One of the Germans then grabbed Private Dupree and wrestled with him as he attempted to take his .45 automatic pistol out of its holster. After a short struggle, the two men fell down a flight of stairs to the ground floor of the hotel. Collier followed the two men down the stairs and fired into the air to scare away any other onlookers. Unfortunately, the German managed to get control of Dupree’s pistol and shot him. Hit twice, Dupree fell into the hotel kitchen and died. The German then turned the pistol on Collier and shot him in the arm. German authorities arrived quickly on the scene, and after a telephone call between them and the American authorities, the wounded Marine and his deceased friend were transported back to the American sector. The Germans later reported that “the men complained of army life and said they were through with it all and were going to Berlin for a good time.”41

The town of Herschbach in late June on the edge of the neutral zone. While preparing to restart hostilities be- cause of the German unwillingness to sign the Treaty of Versailles, Peck wrote on the back: “This was our ad- vance position waiting for the Heinies to sign. In case they refused, Bango Alles Kaput.” Photo courtesy of the Peck family

On 9 June 1919, the Third Army received another message from AEF headquarters, which again indicated the rising tension between the Allies and the Germans:

The enemy has refused to sign the Treaty of Peace presented to him. The Armistice has been renounced by the Allied and Associated Powers, effective at H [hour] of D day. The enemy occupies with one corps of approximately 10,000 second class troops, the territory through which this army will advance. His forces are scattered and are not prepared to offer an organized resistance. Resistance from stubborn detachments of a battalion or less may be expected. No troops have been reported as moving from the east to reinforce this corps. The attitude of the enemy civil population will probably be passive. The British Army of the RHINE on the left, and the French Tenth Army on the right, advance abreast of our army.42

To the soldiers and Marines of Third Army who had fought their way through the Argonne against German soldiers, the statement from higher headquarters that they would only be facing 10,000 second-class troops was probably greeted with some skepticism. They had learned the hard way what a few German soldiers behind a Maschinengewehr (MG08) machine gun, nicknamed the “devil’s paintbrush,” could do to advancing American troops. The MG08 was so respected by the Americans of the Third Army that they had equipped the Marine patrol boats with MG08s instead of their own organic weapons. As tensions between the governments in- creased, the previously friendly relationship between the Americans and the Germans took a sudden downturn. Arguments and street fights increased, and there were several violent incidents leading to injuries and fatalities on both sides. As German hesitation continued to deadlock the peace treaty signing, Marshal Foch finally decided on a date for the operation to commence—20 June 1919 would be D-Day.43 Prior to this, the Allied forces had been told that the day, three days before the actual operation, would be known as J-Day. Once J-Day was announced, all participants would know that they were now in the three-day window prior to the operation and to proceed with their initial troop movements. This planning information was so important in ensuring the transportation requirements for the attack were met that French Lieutenant Colonel Jean Marcel Guitry, the president and senior member of the Inter-Allied Railway Commission, personally telephoned Major Gornusy Courtillet, the French liaison officer in the Third Army Coblenz office, on 16 June to ensure that he and his American counterpart were aware of the impending announcement. At this point, however, H-Hour had not yet been determined, and while the subsequent J-Day (17 June) Third Army message provided further movement instructions for the American units, the exact time for the attack remained a mystery.44

As is so common in military operations, the very next day, 18 June 1919, Third Army received a change: D-Day was now set for 23 June 1919. Along with the date change, there was more information on the enemy situation and follow-on maneuvers:

As no great resistance to our forward movement is expected, we may, by a rapid movement of our advance troops, seize important centers and lines of supply and communication far to the east of the present limit of the bridge-head, thus providing for an extensive forward movement upon further orders from the Allied Commander-in-Chief.45

Simultaneously, as this message was sent, the roads in the American zone on the east side of the Rhine were filled with trucks and horses as the soldiers and Marines of the 1st and 2d Divisions moved to their jumping off points near the neutral zone. By 19 June, even the artillery regiments were in place and ready to support the advance with either fire or further maneuver. The Third Army reported that “concentration of our troops having been completed this date, the American Third Army is prepared to advance eastward.” Third Army also informed the 1st and 2d Divisions in their jump-off positions that H-Hour was now set for 1900 on 23 June.46

The Herschbach town church as it appears today. The town sits on high ground, and from its strategic heights, most of the surrounding area of the neutral zone was visible. Fortunately, the Germans signed the treaty, and the impending battles never took place. Photo courtesy of LtCol Peter T. Underwood (Ret)

The Americans received word that the British forces to the north were ready and in place as were the French to the south. A clear indication of the French influence on the language of the American Army is evident in the 20 June report that stated “camions [trucks] for the forward movement of the 1st Division have been assigned to all units and have reported at designated entrucking points.” With this notification, all eyes turned to the clock. The Third Army logisticians continued to refine their plans. They received the welcome news that they would be provided 25 trucks with drivers to move the Inter-Allied Railway Commission on D-Day because it had been decided that the commission staff would accompany the frontline troops to take immediate control of key railheads. Rations, gasoline, and forage for the animals in the combat units were scheduled to be delivered to designated forward railheads. Ammunition was to be resupplied from stockage maintained at the ammo depot in Neuwied. Evacuation hospitals were loaded on trains and staged at the Coblenz railhead, awaiting movement orders. Resumption of the Great War was now less than 36 hours away.

Tension increased almost to the breaking point on 21 June, when news arrived that the German fleet’s warship crews, who were interned at Scapa Flow in the Orkney Islands since the Armistice, scuttled their own ships rather than have them taken over by the Allies. Before they could be stopped, 74 warships were sitting on the bottom of the harbor. Some nearby British warships fired on them in an unsuccessful attempt to stop the destruction, killing eight German sailors.47 The next day in Versailles, France, the German delegation indicated they might be willing to sign the treaty, except for the clauses that held Germany responsible for starting the war, and asked for an extension to the signing deadline. Still angry at the report of the German warships being scuttled, the Allies rejected this request and informed the Germans that the deadline remained 23 June 1919. At 1800 on 22 June, Third Army reported that “the American Third Army is awaiting orders for forward movement.”48 War was now only 25 hours away, and the Marines of the 6th Regiment were hunkered down in the area around Herschbach awaiting the word to advance. Likewise, the soldiers of the 28th Infantry Regiment, 1st Division, were at Mähren watching the clock. With the possibil- ity of renewed combat looming, events outside the occupation zones now took a sudden turn in rapid succession. In Berlin, the German cabinet and its leader, Reichs Chancellor Phillip Scheidemann, who had taken a strong stand against signing the peace terms, resigned from office. They were almost immediately replaced by a new coalition government formed under the new chancellor, Gustav A. Bauer, a former trade union leader. When the senior German Army leaders were summoned by this new government and asked if they could defend their homeland from an Allied attack, their only reply was that the situation was “hopeless.” In light of this revelation, the German government notified the attendees at the Paris Peace Conference (1919–20) of their intention to sign the peace treaty as written. As a result, at 1000 on 23 June, the Third Army sent a message to its units.

From: Chief of Staff, Third Army

To: Commanding General, III Corps

1. The preliminary operations directed by letter June 19, to begin at 19 h., June 23, are suspended until further orders.49

War was averted with just nine hours to spare. Soon after, another message was sent from Allied Headquarters.

The German Government having indicated its intention of signing the Treaty of Peace, the units of the Allied Armies, while maintaining the alert, are being so disposed as to increase the comfort of men and animals; the divisional areas being extended and certain units withdrawing somewhat from the advance line pending the actual signing.50

On the date the treaty was signed, the 5th Regiment, with headquarters at Hatenfels, occupied the most advanced position ever occupied by Marines in Germany. During the course of the next few days, the Marines of the 4th Brigade made the hike back to their regular duty stations near Leutesdorf, Boppard, and Hönningen. With the crisis over, the members of the brigade and the entire Third Army could begin preparations for what was going to be a memorable Fourth of July celebration in the American occupation zone.

The Fourth of July and the Composite Regiment

In April 1919, the Regular Army divisions in the Third Army received orders to establish a company-size element in each of their infantry brigades, which would represent their division in the postwar celebrations. They would also serve as the U.S. representative to the many ceremonies that would take place. The Composite Regiment was composed of a headquarters detachment with a band and 12 infantry companies as follows:

- 1st Battalion: Company A, 1st Division; Company B, 1st Division; Company C, 3d Division; and Company D, 3d Division.

- 2d Battalion: Company E, 4th Brigade (USMC); 2d Division, Company F; 3d Brigade, 2d Division; Company G, 5th Division; and Company H, 5th Division.

- 3d Battalion: Company I, 4th Division; Company K, 4th Division; Company L, 6th Division; and Company M, 6th Division.

One aspect of 2d Division culture had to be changed to accommodate uniformity requirements of the Composite Regiment: the shoulder patch. The 2d Division had previously chosen an Indianhead imposed on different shapes and with varying colors to represent the individual units. For the Composite Regiment, the background design was replaced by a star, thereby presenting a uniform appearance for the Army and Marine representatives in the regiment.

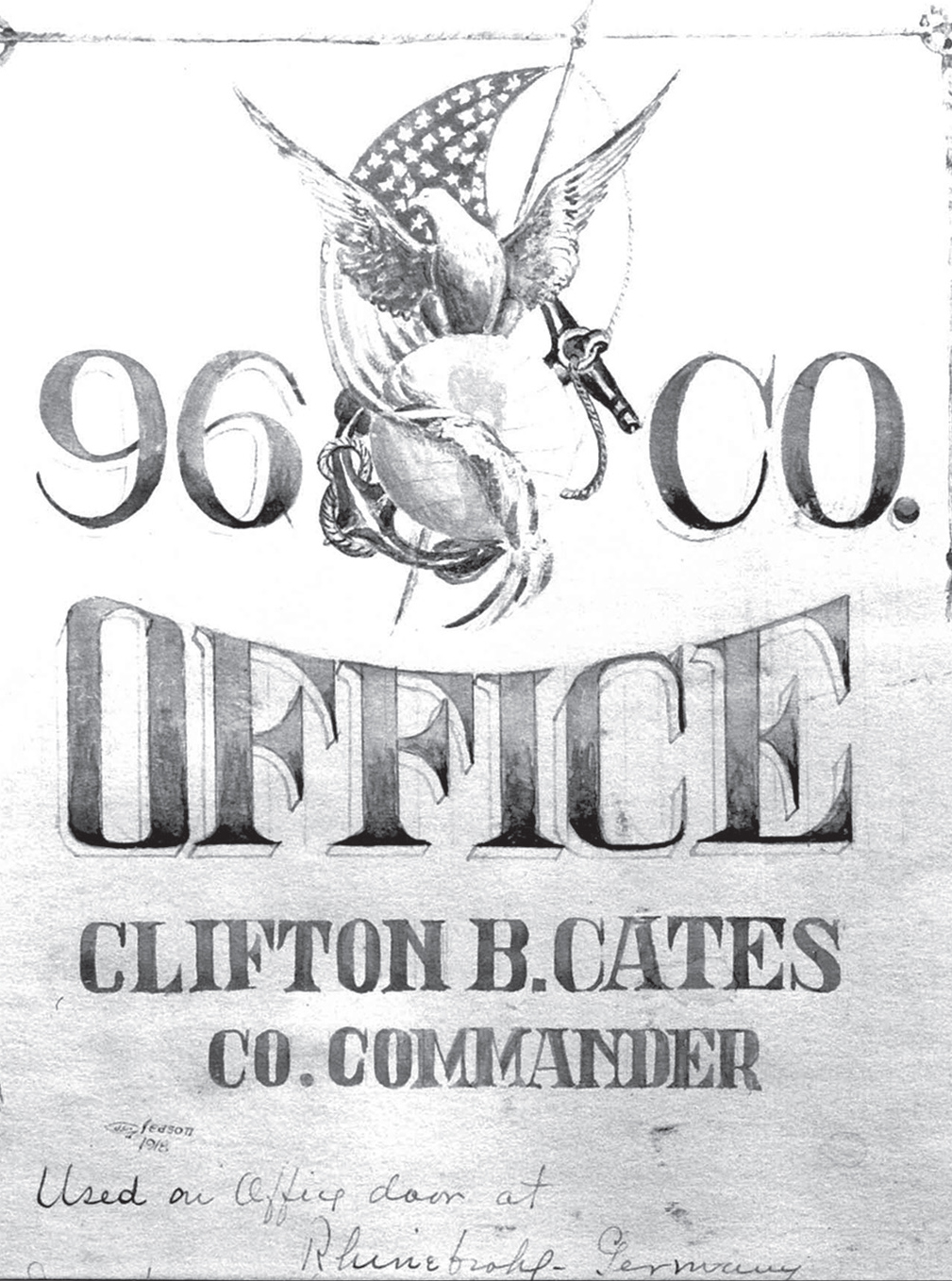

The sign for the 96th Company office of Capt Clifton B. Cates. Cates served with distinction during the fighting at Belleau Wood and was an excellent choice to lead the Marine component of the Composite Regiment. He would later serve as the nineteenth Commandant of the Marine Corps. HRB, Marine Corps University

Unlike many military directives that often provided a unit the opportunity to remove malcon tents or troubled soldiers, the composite units were formed from among the very best and most combat-experienced men. After selection, the companies from all the divisions reported to Third Army headquarters at Coblenz, where they were formed into the three battalions of the Third Army’s Composite Regiment. The Marine officers chosen to lead the 4th Brigade were well known figures among Marine Corps lore. The commander of the 4th Brigade contingent (now Company E, 2d Battalion, Composite Regiment) was Captain Clifton B. Cates. His second-in-command and executive officer was First Lieutenant Merwin H. Silverthorn. Both would go on to illustrious Marine Corps careers.51 Cates would later recall in an oral history interview how the Marines for the unit were chosen: “We had I think about 12 or 14 lieutenants and about 400 enlisted men that were already handpicked. The first requirement was they had to be 5 feet 10 inches tall, and they had to have been in combat operations, and they had to be in good shape physically.”52

Now assembled with the finest soldiers from the other Regular Army divisions, the Marines and doughboys from the 2d Division drilled with a vengeance. In late May and June, while the rest of the Third Army’s infantrymen were cleaning weapons and preparing to go back to fighting, the members of the Composite Regiment continued drilling. Their first official appearance outside the American zone had to be postponed because of the German delay in signing the Treaty of Versailles. They were scheduled to accompany General Pershing to London for a victory parade, but Pershing decided to cancel his appearance and instead stayed at his headquarters in the event hostilities began. As a result, the regiment remained encamped on Carnival Island near Coblenz.53 To keep their skills sharp, the regiment paraded every other day through the streets of the city. On 24 May 1919, American Army of Occupation (AMAROC) News reported that the marching soldiers and Marines were “picked for size and appearance, with every man in new clothing and equipment, they look [like] soldiers [to] the last man . . . marching in line of half companies, two platoons abreast, with the 3rd Division band in the lead.”54

A group of officers from the 5th Regiment pause for a sandwich. This photograph was likely taken during one of many drill sessions in preparation for service in the Composite Regiment. Although the units of the 2d Division wore different versions of the Indianhead patch, before they joined the rest of the Composite Regiment, all would switch to the same patch with the white star background and their helmets painted accordingly. HRB, Marine Corps University

As the treaty crisis was being resolved, the Composite Regiment departed Coblenz for Paris via train. Known now as “Pershing’s Own,” the Composite Regiment made its first public appearance at the Inter-Allied Games being held in Pershing Stadium. During the opening ceremonies on 22 June, the regiment was reviewed by General Pershing and French Premier Georges B. Clémenceau. The unit performed guard and escort duties during the athletic competitions. This was followed by Independence Day ceremonies on 4 July, and 10 days later, the French Bastille Day ceremony. These were proud moments for Cates and 100 of his Marines as they marched in the parades. Although the regiment was at reduced strength on these occasions, the order of march was the same. The Marines fell in just behind the massed colors and standards of the regiments of the Third Army as they passed through the Arc de Triomphe de l’Étoile and down the Champs-Élysées to the Place de la Concorde.

After the victory parade in Paris, Cates’ Company E accompanied General Pershing to London. Enjoying a few days in Britain, which included an inspection by the Prince of Wales in Hyde Park, they marched in the Empire Day victory parade.55 The Marines then crossed the English Channel again to embark on the USS Leviathan (1913) and returned home with Pershing. On 19 September 1919, Company E was detached and transferred to the Marine Barracks Washington, and on the 20th, Cates paid his men and discharged those who had decided not to remain in the Corps.

While the Composite Regiment was drilling and marching, the rest of the Third Army back in the occupation zone prepared for the Fourth of July celebration. Starting early in the day, concerts were held by all of the units’ bands and at noon there was a 48-gun salute in honor of the 48 states. One of the culminating events was a baseball game between the 3d Division and the 2d Division. Most of the other units followed suit, and the American zone turned quickly into a hotbed of athletic competition.

Following the full day of concerts, sporting events, pie-eating contests, and boxing matches, all the inhabitants of the zone eagerly awaited the arrival of darkness. Shortly after 2100, two signal guns were fired from on top of Ehrenbreitstein Fortress, and the grand finale began. The 17th Field Artillery, stationed in the fortress, shot off the 10,000 captured German signal rockets and flares it had in storage. As the sky lit up with multicolored streamers from the flares, the 4th Division to the north of Coblenz pitched in, launching their own supply of captured pyrotechnics. The show continued until midnight, when the massive stockpiles were finally exhausted.56 The New York Times reported the next day that “the Americans have just finished a Fourth of July celebration the memory of which will live long in the Rhineland, and it will not soon be forgotten by the hundred thousand soldiers who staged it. In the doughboys’ slang, it was a ‘beaucoups show’.”57 The timing of the celebration was particularly appropriate because the Third Army was quickly shrinking; on some days, up to 8,000 soldiers left the occupation zone for the United States. After it was over, all who witnessed it agreed that they had successfully brought the excitement of the American holiday to the German Rhineland.

Homeward Bound

With the departure of the Composite Regiment from the Coblenz area en route to their full schedule of appearances in London and Paris and the conclusion of the Fourth of July celebration, the high water mark of the Third Army had been reached. Very shortly thereafter, the Third Army was renamed the American Forces in Germany and a new commander, Major General Henry T. Allen, took over. The 4th Division departed the American zone on 12 July and the 2d Division began to leave a short while later on 21 July. The 3d and 1st Divisions left on 11 and 12 August, respectively.

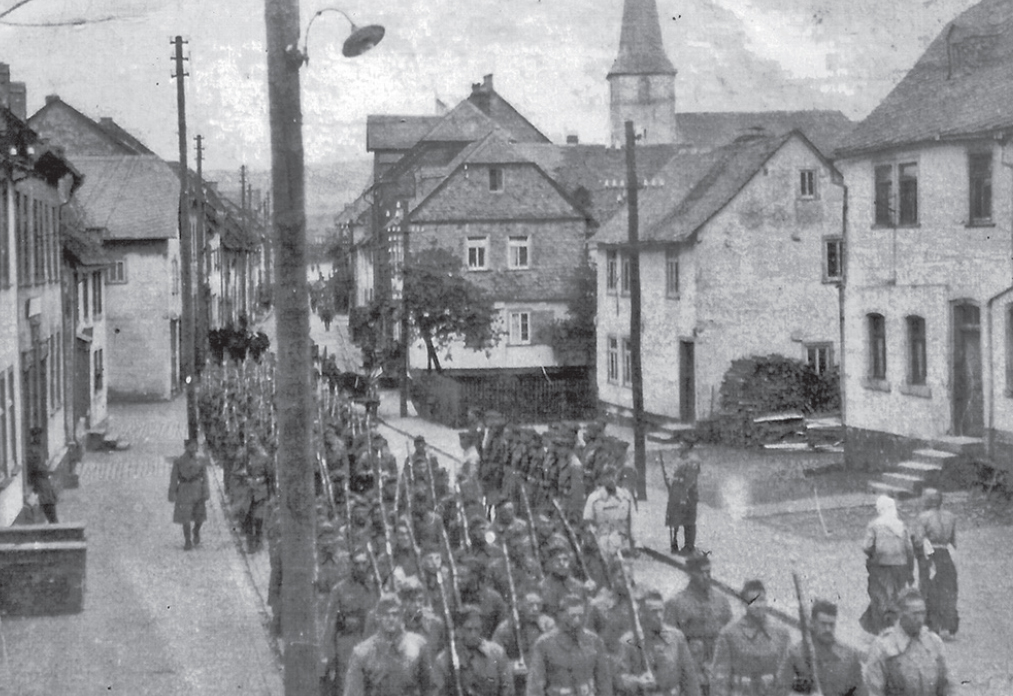

A key part of each victory parade was the marching of the AEF units. Here, the 6th Regiment receive a warm welcome as they march down 5th Avenue in New York City on 8 August 1919. HRB, Marine Corps University

In the 4th Brigade, the Marines were well aware of this movement; Vann Peck wrote his mother on 3 July that “I expect to walk to Leutesdorf tomorrow and then go up to Neuwied or Coblenz for it may be the last chance I get. The way things look we will sail this month.”58

The westward journey was a marked change from the original march to the Rhine. Instead of hiking, the now well-fed and well-dressed soldiers and Marines of the 2d Division were divided into train-size contingents and dispatched to the transit camps outside the port of Brest in mid-July. General Lejeune, his staff, the 4th Brigade headquarters, the 5th Regiment, and the 2d Battalion of the 6th Regiment sailed on the USS George Washington (ID 3018) and arrived in the United States on 3 August. The 6th Machine Gun Battalion sailed on the USS Santa Paula (ID 1590) and arrived on 5 August, while the remainder of the 6th Regiment sailed shortly thereafter on the USS Rijndam (ID 2505) and the USS Wilhelmina (ID 2168). The Marine contingent of the Composite Regiment arrived on 8 September, still serving as the escort for General Pershing. While the ocean voyage was more pleasant than their previous trip, the 2d Division still had one more mission before they could demobilize— a parade in New York City on 8 August and then a review by the president in Washington, DC, just four days later to celebrate their well-deserved victory. With the parade and review completed, the Marines of the 4th Brigade returned to Quantico, Virginia, on 12 August. Their final duties consisted of being fitted for and issued new green uniforms as well as drawing their closeout pay and a train ticket home.59 The 4th Brigade, brought to life to serve in the AEF’s 2d Division on 24 October 1917 at Bourmont, Haute-Marne, France, was deactivated on 13 August 1919, its mission complete.

Author’s collection

Photo courtesy of the Matthew Fidler collection

• 1775 •

Endnotes