On the morning of 7 August 1942, personnel from the 1st Marine Division scrambled onto their landing craft and began the invasion of Guadalcanal, the first step by Allies to retake the Solomon Islands from forces of the Japanese empire.1 Mountains of material have been written on these legendary battles, from books by historians such as Richard B. Frank and Eric M. Hammel to memoirs from individual Marines who took part in the conflicts on Bougainville, Guadalcanal, and New Georgia. However, none of these works discuss what happened to the remains of those Marines who did not survive these encounters with the Japanese or determine how many Marines may still lie in unmarked graves on the Solomon Islands or remain unidentified in American cemeteries and why many of these Marines were not able to be properly identified after the end of World War II. The Marines killed in the Solomon Islands who remain unrecovered or unidentified remain so because a lack of trained graves registration personnel and a policy decision to inter their remains on the battlefield either rendered their burial site lost to history or their remains too decomposed for identification.

How Many Marines Remain Unidentified?

After the conclusion of World War II, the Memorial Division of the Office of the Quartermaster General (OQMG) created the “Rosters of Military Personnel Whose Remains Were Not Recovered, 1951–1954.”2 “The Rosters” is an electronic list created by the De- partment of the Army in 1954 of military personnel whose remains were not recovered or identified during or after World War II. The list is arranged alpha- betically by surname of the decedent and lists rank, branch of Service, date of death, and the geographical area in which the servicemember died. “The Rosters” used a system of “geographic codes” to detail not only the theater in which an individual was lost—the “area code”—but, in cases of Service personnel from the U.S. Marine Corps and Navy, the individual country using a “pinpoint code.” Unfortunately, the original key to these codes does not accompany the copy of “The Rosters” held by the National Archives and Records Administration (NARA), and it is not known which organizations originally assigned the area and pinpoint codes. The NARA data file of World War II prisoners of war (POWs) provided initial information on the codes associated with individual theaters and countries.3 Historians at the Defense Prisoner of War/Missing Personnel Office (DPMO), renamed the Defense POW/MIA Accounting Agency (DPAA) in 2015, analyzed a sample of individual deceased personnel files (IDPFs) created for each U.S. servicemember lost during World War II.4 Through the use of IDPFs and other documents held by NARA, the historians were able to determine that 08 is the primary area code, and 3H is the primary pinpoint code used in “The Rosters” to indicate Marine Corps losses in the Solomon Islands.5

A graves registration worker points out the outlines of a body to his crew. National Archives

In 2007, DPAA released the “Service Personnel Not Recovered Following World War II” list of more than 78,000 U.S. Service personnel whose remains were not recovered or identified from that conflict. Using this data revealed that 798 Marines were not recovered or identified whose geographic codes place their area of loss in the Solomon Islands. The names of each of those Marines were compared with individuals on lists of personnel buried at sea and personnel lost in the sinking of U.S. Navy ships. Per these two lists, 48 Marines were buried at sea and 71 were killed when their ship sank during one of the many battles between the United States and the Imperial Japanese Navies in the Solomon Islands. Lastly, because of an error in coding, the individual deceased personnel file of 15 Marines include area and pinpoint codes that indicate they were lost in the Solomon Islands when in fact they were lost elsewhere in the Pacific theater. Removing those Marines buried at sea, lost in the sinking of Navy ships, and mistakenly included in the overall number of Marines unrecovered from the Solomon Islands leaves approximately 663 Marine Corps personnel still de- serving of a proper burial.

The Military Establishes a Graves Registration Service and Learns from World War I

After the United States’ entry into World War I in August 1917, Secretary of War Newton D. Baker Jr. issued War Department General Orders No. 104, which authorized the creation of a graves registration services.6 By the end of the war, 19 graves registration companies were created by the Quartermaster General and sent to Europe.7 During the war, one of the most important duties of the GRS was, “the deployment of units and groups along the entire line of battle, so that they might begin their work of identification of bodies and marking of graves im- mediately upon the beginning of hostilities in any given sector.”8 The policy of deploying graves registration units as quickly as possible, sometimes even while hostilities were ongoing, resulted in successful identification of 96.5 percent of the 79,129 U.S. military deaths in World War I.9 According to OQMG historian Edward Steere, the experience of World War I resulted in the emergence of a “theater graves registration service, with its operating units in close support to combat.”10

During the 1920s, many of the policies established during World War I were codified in Army regulations. In February 1924, the War Department published the AR-30 series of Army regulations (AR) that governed graves registration responsibilities during the first half of World War II, until their replacement by a new set of AR-30 regulations in 1943. One of these regulations, known as AR-30-1810, established strict procedures for the registration of unmarked graves, the care and disposition of unburied remains, and the identification of individual remains.11 According to AR-30-1810, burials of military personnel during wartime were to be conducted and supervised by “detailed burial officers and commanding officers under the general supervision of the graves registration officer of the command.”12 These regulations also heavily discouraged the use of isolated burials, which were defined as a group of less than 12 graves because, as AR-30-1810 noted, “Every isolated burial renders liable the loss of a soldier’s body.”13

Graves Registration on Guadalcanal

Prior to World War II, the AR-30 regulations anticipated that, upon a declaration of war, four graves registration companies would be activated, which would have “served as a nucleus for expansion” of the graves registration service.14 However, the surprise Japanese attack against the American base at Pearl Harbor, Hawaii, on 7 December 1941 gave the U.S. military no such opportunity for slow expansion, and with it adequate training. According to Steere, “under the accelerated training program of wartime there was no unit training.”15 Only seven complete graves registration companies were active in August 1942 at the beginning of the invasion of Guadalcanal, and none of them were fully trained.16 The Army estimated that each graves registration unit needed three months of training to adequately perform its function in the field.17 It was not to be until early 1943 that an adequate training program was available for graves registration units.18 The 604th Quartermaster Graves Registration Company, which later served on Guadalcanal in postwar search-and-recovery operations, became the first graves registration company to complete a training course at Vancouver Barracks Unit Training Center in Washington State.19

The lack of fully trained graves registration personnel heavily influenced the graves registration policy pursued by the Marine Corps during operations in the Solomon Islands. The Marines modeled their graves registration doctrine using a recent example of an operation conducted without the benefit of graves registration personnel—the U.S. Army’s long retreat down the Bataan Peninsula on the island of Luzon, Philippine Islands, in 1941. During the retreat, Army troops were forced to develop their own graves registration service using untrained personnel and to perform burials wherever possible instead of waiting to inter their fallen comrades at a central cemetery. Facing the same lack of trained personnel in mid-1942, the Marines simply copied the Army’s policy used on Bataan and improvised a graves registration service staffed by combat personnel under the direction of the Navy’s Bureau of Medicine and Surgery.20

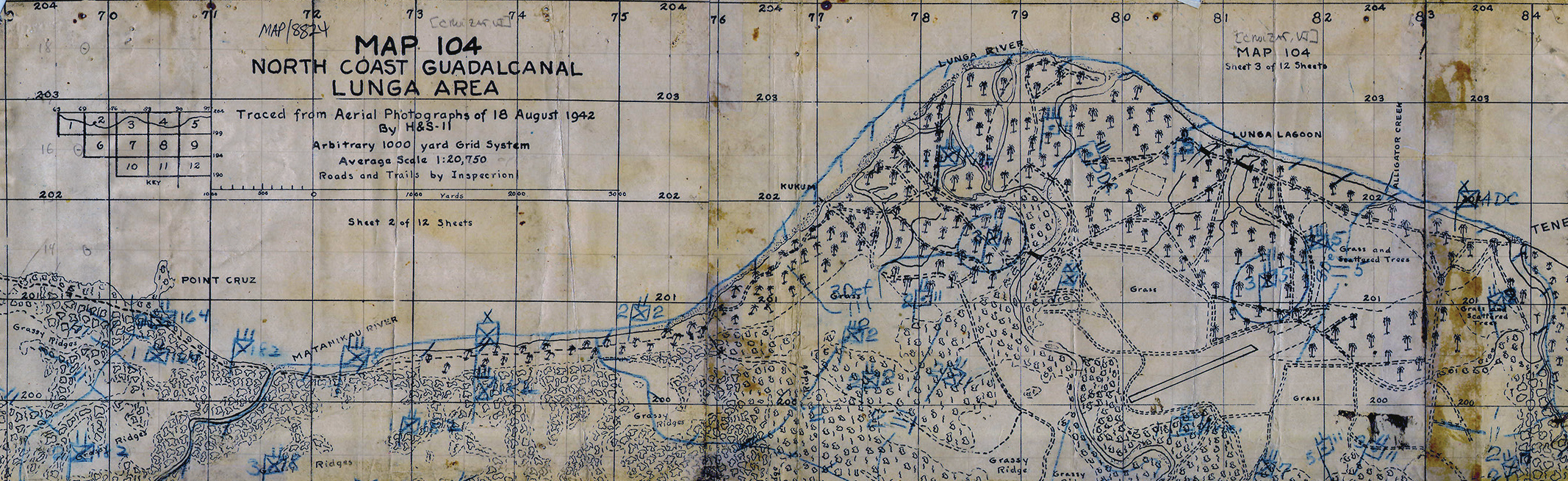

Map of Guadalcanal. Official U.S. Marine Corps map

Burial policy prior to the invasion held that, “a necessary concession to conditions of combat” would have to be made, and initially, Marines killed on Guadalcanal would be buried on the battlefield and not taken to a central collection point for proper identification and burial.21 The Marine Corps directed a platoon of combat personnel selected for graves registration duties to follow the main combat invasion force ashore.22 A postwar critique of this unit stated that it “confined its activities almost entirely to emergency burial on the battlefield.” Plans for the invasion of Guadalcanal stated that, once the main combat objectives were accomplished, it would then be feasible to establish a cemetery on the island. It was not until the arrival of the U.S. Army’s Americal (23d Infantry) and 25th Infantry Divisions in November and December 1942 that a provisional island graves registration service was established. Plucked out of the artillery and transferred to the Quartermaster Corps because he worked as a mortician prior to the outbreak of the war, Warrant Officer (later First Lieutenant) Chester E. Goodwin headed this new effort to improve graves registration operations on Guadalcanal. Under Goodwin’s leadership, GRS personnel immediately began to bring the haphazard layout of the cemetery on Guadalcanal into conformity with specifications approved by the OQMG. On 18 February 1943, the 1st Platoon, 45th Graves Registration Company, became the first graves registration unit in the Solomon Islands. However, they were not given motor transport or enough labor personnel to enable Goodwin to initiate a program to disinter and collect the remains of the Marines buried on the battlefields around the island. Goodwin’s unit only consisted of six enlisted personnel and native laborers. U.S. Army Colonel Joseph H. Burgheim of the Quartermaster Service Command, New Caledonia, wrote to Army Major General (later Lieutenant General) Edmund B. Gregory, Quartermaster General, shortly after the activation of the 1st Platoon, 45th Graves Registration Company, and stated that

No attempt has been made to date, to move battlefield casualties to the cemetery owing to the battered condition under which these bodies were interred and the rapidity with which decomposition takes place in the tropical climates, and these bodies must wait for a considerable time before they can be exhumed and reburied in proper cemeterial plots.23

According to Steere, “Lacking trained personnel and motor transport, essential to the operation of a collecting point system, any persistent effort at evacuating bodies to a centrally located burial place only tended to defeat the utilitarian purpose sought in first removing the dead.”24 Records of the OQMG indicate that burial of the dead by graves registration personnel in the combined U.S. Army, Navy, and Marine Corps cemetery on Guadalcanal occurred as early as January 1943.25 However, none of the Marines buried in the cemetery during that month had been disinterred from a battlefield grave and reburied in the cemetery; all of the burials were of Marines killed in late 1942 and early 1943. Unfortunately, the location of the consolidated cemetery on Guadalcanal does not appear on any map created by either the Marines or Army troops from the OQMG. The second and third pages of the burial plot chart for the cemetery in the holdings of NARA states “See Page 1” for its location; however, page one of this plot chart is missing. The likely location of this cemetery was near Henderson Field. According to Marine Corps Chaplain W. Wyeth Willard, the cemetery was “out past Henderson Field.”26 When Willard and the 3d Battalion, 1st Marine Division, departed Guadalcanal on 15 December 1942, the cemetery consisted of 650 graves.27 This number of graves is sufficient for less than half of the 1,769 Marines and Army soldiers killed on Guadalcanal.28

Battlefield Burials on Guadalcanal

Burial information for Service personnel killed during World War II was recorded on OQMG Form 371, “Data on Remains Not Yet Recovered or Identified,” which was completed for each servicemember’s IDPF. The exact coordinates where burial occurred on the battlefield were recorded for 82 of the 137 Marines who were killed on Guadalcanal. These coordinates were determined using a Marine Corps map known as “Map 104, North Coast of Guadalcanal, Lunga Area,” which used an arbitrary 1,000-yard system to divide the map into grid sections.29 It is unknown which Marine organization drew the original map, but the creation of a map fitting its description is discussed by Navy Captain William H. Whyte in his memoir, A Time of War. According to Whyte, “[Lieutenant Colonel William McKelvy] instructed [Corporal] Wilke to draw up a battalion map. It was a handsome affair. The lettering was especially impressive, ‘North Coast of Guadalcanal–Lunga Area’.”30 These deaths and the burial locations generally follow the course of the lengthy battle for Guadalcanal.31

In addition to the Marines known to have been buried on the battlefield, 86 Marine airmen were lost on or around Guadalcanal. These losses encompass at least 48 different loss incidents; 19 of the losses occurred in a variant of the Douglas SBD Dauntless dive bomber (the SBD-3, SBD-4, or SBD-5) and another 18 occurred in a variant of the Grumman F4F Wildcat aircraft (the F4F-1 or F4F-4). Identifying the location of air losses is a tricky one, however, because only the last known location of the aircraft can be identified. In some cases, the last known sighting of the aircraft occurred when it took off from Henderson Field. Therefore, the actual location of the crash can be anywhere between Henderson Field and the intended target location—either on Guadalcanal, at sea, or another island.

Adherence to Established Prewar Policy Leads to Fewer Unidentified Marines

Elsewhere in the Solomon Islands, the policy of battlefield burials without relatively quick disinterment and reinterment in the local cemetery does not appear to be a widely accepted practice. Just prior to the invasion of New Georgia, the 43d Infantry Division ordered that burials were to be confined to those at sea or inshore cemeteries.32 Because the New Georgia invasion did not begin until 20 June 1943, Goodwin also was afforded the time to train provisional graves registration units.33 According to Steere, “Bodies were removed from the battlefield and, whenever possible, carried to task force or island cemeteries.”34 These provisional units were reinforced by the 109th Quartermaster Graves Registration Platoon, which arrived on 3 August 1943.35 In addition to recovery and identification operations, the 109th began building the permanent cemetery on New Georgia in September 1943.36 There is evidence that graves registration troops from New Zealand assisted in the effort to recover casualties from the battlefield.37 According to Steere and fellow Quartermaster historian Thayer M. Boardman, “New Georgia Island underwent a rather thorough search during the wartime American occupation, but construction work either covered or wiped out many graves.”38

In total, 33 Marines are still not recovered or identified from action on New Georgia. The vast majority of these Marines are airmen lost in attacks against the Japanese airfield at Munda on 1–2 February 1943. Unfortunately, not all of these aircraft are potentially recoverable. According to the IDPFs of their occupants, four of these aircraft are known to have crashed into the ocean. Overall, 17 Marine airmen, whose area of loss is New Georgia, are currently not recovered or identified; these 17 losses occurred in nine separate loss incidents. Eleven of the 17 airmen currently not recovered or identified were lost while flying a Grumman TBF-1 Avenger torpedo bomber, another 3 in an F4F-4 Wildcat, and 3 in an SBD-4 Dauntless dive bomber. Out of nine separate loss incidents, five TBF-1 Avengers, three F4F-4s, and one SBD-4 crashed on and around New Georgia. Of the 15 Marines known to have been lost on the ground in New Georgia but have not yet been recovered or identified, only 5 are known to have been buried on the battlefield. The majority of the Marines not recovered or identified, including the only Marine buried on the battlefield with exact burial coordinates recorded in his IDPF, were lost on the same day, 20 July 1943, during a Marine attack on Japanese positions at Bairoko Harbor.39

The ground loss statistics for Bougainville, Papua New Guinea, are similar to those on New Georgia. However, as with the invasion of Guadalcanal, the invasion of Bougainville illustrates the impact the absence of trained graves registration personnel in the invasion force had on the number of unrecovered or unidentified Marines. Even though the Marines had been bombing and harassing the Japanese garrison and airfield on Bougainville since the arrival of airplanes to Henderson Field on Guadalcanal in 1942, the actual land invasion of Bougainville did not begin until 1 November 1943. Unfortunately, trained graves registration personnel from the 1st Platoon, 49th Quartermaster Graves Registration Company, did not arrive on Bougainville until 8 November 1943.40 Of the 39 Marines lost in ground action on Bougainville and still not yet recovered or identified, 10 were lost on 1 November 1943 and another 4 on 7 November, before the arrival of graves registration personnel. However, evidence exists that the 1st Platoon, 49th Quartermaster Graves Registration Company, did conduct wartime search-and-recovery operations. Per the unit history, Sergeant Jakob O. Christofferson received the Bronze Star for recovery of the remains of U.S. Service personnel killed in an aircraft crash beyond American lines.41 Staff Sergeant Stanley J. Zisk also received a commendation for outstanding service for directing the removal of remains from temporary burial plots and their reinternment into the cemetery on Bougainville.42

By far, the largest number of Marine airmen not recovered or identified have Bougainville as their area of loss; for example, 65 Marine airmen are not recovered or identified from action over or around the island. As with the action elsewhere in the Solomon Islands, some of these losses undoubtedly occurred over deep water and the exact location of the aircraft crash may never be known.

Postwar Graves Registration in the Solomon Islands

After the end of World War II, in addition to providing burial and identification services on the battlefield, the American GRS (AGRS), under the direction of the OQMG, identified and repatriated the remains of U.S. servicemembers killed during the war in the Pacific. The responsibility and authority for these operations was assigned to the commanding general of American forces in the western Pacific.43 Three subordinate sector commands were also established: MIDPAC (mid-Pacific) sector, WESPAC (western Pacific) sector, and JAP-KOR (Japan-Korea) sector. The Solomon Islands, because of the geographical broadness of the area, were assigned to both MID-PAC and WESPAC sectors, with the northern Solomon Islands assigned to WESPAC and the southern Solomon Islands assigned to MIDPAC.44

There apparently were operations undertaken in the southern Solomon Islands to search and recover remains of U.S. military personnel immediately following the surrender of Japan and then again in July 1946.45 Unfortunately, the organizations that conducted these operations and their results remain a mystery. Operational plans were laid out for a third search-and-recovery operation of isolated burials in the Solomon Islands to begin on 15 May 1947 and conclude three months later.46 Prior to the beginning of this third recovery operation, an estimated 277 U.S. personnel potentially were recoverable from isolated burials in the southern Solomon Islands, including 268 on Guadalcanal.47 As we have seen, the AGRS woefully underestimated the number of potentially recoverable Marines on Guadalcanal. However, the AGRS did their best to recover the low number of Marines they estimated were yet to be recovered.

On 15 July 1947, the 1st Platoon, 604th Quartermaster Graves Registration Company (QM GRC), left Hawaii on board USS LST 711 en route to the South Pacific to conduct search-and-recovery operations. A detail of 33 men and 5 officers were to search Guadalcanal while the rest of the company continued operations elsewhere because, “A number of men lost during the heavy fighting in the fall of 1942 and early spring of 1943, had never been recovered and in view of time elapsed [of] four years, rapid growth of jungle covering the area where these men fell would entail a great amount of work in searching.” After LST 711 arrived back at Guadalcanal on 18 October 1947, the 604th QM GRC began an intensive area search of Guadalcanal during 19–24 October. According to the unit history, “As most of all the fighting on Guadalcanal covered an area starting at Henderson Field and extending west for approximately six miles and to an average of three miles inland, this area was concentrated on.” In addition to trained graves registration troops, the 604th QM GRC also enlisted the aid of natives on Guadalcanal in the area search. The specific details of any recoveries made by the company on Guadalcanal are unknown. However, the 604th QM GRC did recover certain remains and also knowingly left others unrecovered, possibly because these remains were in locations that made them simply impossible to recover. For example, on 1 November, a team from the 604th ascended Mauru Peak on Guadalcanal to recover remains from the crash of a Douglas C-47 Skytrain, which caused the loss of 12 U.S. Service personnel, including the Marine pilot and crew. The team only recovered the remains of eight individuals, “leaving four unrecoverable.” On 6 November, the 604th QM GRC investigated losses on the west bank of the Matanikau River without success. According to Chief Warrant Officer John R. McBee, the area to the west of the river, which he had fought through during World War II, had changed significantly, and he recognized very little.48

The 604th QM GRC also investigated losses elsewhere in the Solomon Islands, not just on Guadalcanal. On 26 November and 1 December 1947, the company investigated losses on New Georgia, specifically those which occurred at Munda Point. Specific details of this investigation are unknown; however, the unit history specifically states that this investigation did not result in any recovered remains. Natives reported that remains had been removed previously from New Georgia and that they did not know of any other aircraft crashes or isolated burials. During 12–19 December, the 604th extensively investigated losses that occurred on the island of Bougainville. Little detail is known about the identity of individual remains the 604th QM GRC attempted to recover during these investigations. Per the unit history, the company recovered two sets of remains from Bougainville and that the cases of several other U.S. Service personnel lost on Bougainville were sent for further investigation by an unknown higher authority.49

The grave of an unknown American on Guadalcanal, ca. 1942–43. National Archives

Consolidation of cemeteries in the southern Solomon Islands (as well as from Espíritu Santo, Efate, New Hebrides) to the Army, Navy, and Marine Corps cemetery on Guadalcanal occurred in September 1945.50 From November to December 1947, the 9105th Technical Services Unit (TSU) operated a mausoleum on Guadalcanal and was charged with identifying the dead consolidated into the cemetery and preparing their remains for shipment.51 The majority of more than 3,000 remains processed by the 9105th TSU were skeletal and not casketed.52 Therefore, the possibility exists that a large number of these remains were unable to be identified and were later buried as unknown remains. The USAT Cardinal O’Connell transported all the remains from Guadalcanal to Hawaii in January 1948.53

Remains from cemeteries on Rendova and Bougainville Islands were consolidated in the cemetery on New Georgia and then removed to Finschhafen, New Guinea; though, little is known about the consolidation of cemeteries from the northern Solo- mon Islands.54 However, the dates these operations were undertaken and the organizations involved is unknown. In May 1947, operations began to remove remains from cemeteries in Finschhafen to their ultimate burial destination, the Manila American Cemetery and Memorial in the Philippines.55 The removal of all remains from Finschhafen was completed and the temporary cemetery closed 22 March 1948, thus ending the journey to a final resting place for U.S. Service personnel recovered from the Solomon Islands.56 While the recovery effort by the graves registration personnel involved was noble and herculean in task, if the military had followed its own established procedures following World War I, and been better prepared for war, those ships could have carried more identified Marines out of the Solomon Islands.

• 1775 •

Endnotes