America’s Citizen Marines—State Militias, a Tradition of National Service

To address more than a century of evolving national requirements, the United States Marine Corps added the crisis response capabilities of the Marine Corps Reserve (Reserve); its origins can be traced to the inadequacies of the states’ naval militias for the defense of democracy and protecting the country’s interests abroad. The 1916 legislation authorizing a Reserve provided a source of trained manpower and, not surprisingly, was the result of a coordinated Navy-Marine team approach.1 This first part of a two-part story discusses how the Reserve in World War I depended greatly on the development of Marine branches inside state naval militias, the initiatives authorizing the Reserve and its mobilization, and finally the contributions of the Marine Reserve during the war.

The founding fathers recognized the need for a strong military reserve, but not as it has come to exist. The authors of the Articles of Confederation and later the U.S. Constitution were concerned about possible excesses of a large standing army and its expense on a fledgling nation. Retaining the citizen-soldier character of the military after the American Revolutionary War was fundamental to the survival of the new nation. A small standing army, backed by well-armed and -trained militias provided by the states, offered support for national emergencies.

The U.S. Constitution, which took effect in 1789, addressed the use of state militias with Article I, Section 8, Clause 15, defining the grounds for Congress to call up militias “to execute the laws of the Union, suppress insurrections, and repel invasions.”2 Then on 2 May 1792, Congress passed the Uniform Militia Act (1 Stat. 264) requiring enrollment in the states militia, specifying exceptions to enrollment and providing guidance on organization and arming of the state militias.3

The War of 1812 was the first great test of the militia system. However, when many of the militiamen refused to leave their home states, the militia proved to be of little national value. Militia deployments were not authorized for the Mexican-American War because the conflict did not meet the criteria for employment of state militias as defined in the Constitution, that is to enforce laws, repel invasions, and suppress insurrection. Use of state militias in the American Civil War was more effective—the militias could be used to end insurrections but members were limited to no more than three months active duty.4 Secretary of the U.S. Navy Benjamin F. Tracy (1889–93) stressed the importance of a trained militia for the Navy and called for funding arms and equipment for naval militia in various seacoast states. As a result of his efforts with Congress, in his annual report for 1892, Tracy noted the naval appropriation act, approved 19 July 1892, provided $25,000 for naval militias. In that annual report, he also confirmed qualifying instructions for states seeking a portion of the funds. Seven states formed and mustered in naval militias by the time Tracy submitted his annual report on 10 December 1892. One additional state mustered in a naval militia unit before the end of the year.5

In spite of various congressional actions to improve the state militia system, the Constitutional restrictions on employment of militia remained unchanged, and by the end of the 1898 Spanish-American War, the militia system, which relied on militiamen provided by states, was shown to be inadequate in responding to national emergencies.6

Calls for a National Naval Reserve

The office of the state adjutant general monitored the state militias, including the naval militias. A review of annual adjutant general reports reveals a consensus that improvements were needed in the militia systems.

Of particular note are the difficulties encountered in New York state. In the Annual Report of the Adjutant General of the State of New York for the Year 1898, C. Whitney Tillinghast II emphasized a major lesson from the Spanish-American War: the states’ abilities to provide forces to support the national call were hindered by the U.S. Constitution’s restrictions on the use of militias. Since that war did not meet Constitutional requirements, Tillinghast noted the state of New York was forced to ask its militia for volunteers. While volunteers did come forward, the administrative nightmares associated with reporting the New York militia volunteers “mustering in,” or swearing in for federal duty to the satisfaction of the U.S. War Department, were extremely challenging and frustrating, particularly federal payment to the volunteers.

In an exchange of telegrams from May through July 1898, the War Department and the New York adjutant general attempted to sort through the administrative issues associated with the expenses of food and shelter, transportation, and pay for the volunteers for federal service.7

Additionally, included in the New York adjutant general’s 1898 report was the report of the head of the New York Naval Militia, Captain J. W. Miller. Miller wrote on the war with Spain, “The personnel of the Naval Militia is well fitted to defend the immediate coast of the State. If it be desired to perfect the officers and men for deep-sea duty, the general government must provide suitable tools, in the way of modern ships. This has been recommended by me in many annual reports.”8

Miller added “If the general government provided these ships, it would naturally expect a high standard of excellence both in officers and men. This standard can be obtained by the enactment of a National Naval Reserve Law.” He also recommended the National Naval Reserve have its own ranks and ratings and be distinct from the U.S. Navy and that the federal government publish the “scope of examinations for entrance to the Naval Reserve . . . and a certain proportion of the Naval Militiamen of each State should have passed it before any aid was supplied by Congress.”9

Under President William McKinley’s direction, the secretary of the War Department was to procure soldiers from the states’ National Guard (NG) units.10 New York’s challenges in responding to federal requests for more manpower were typical of the other states of the Union. More improvements in growing a crisis response capability were needed.

On 1 November 1900, Lieutenant Commander William H. H. Southerland (USN), officer in charge of the Navy Department’s Naval Militia Office and future commander of the Navy and Marine force in Nicaragua in August 1912,11 wrote to the secretary of the Navy about the inadequacies of the naval militia system:

I call your attention to these facts to show the absolute necessity for the creation, in addition to the naval militia organizations, of a Government or national reserve force, which should be organized entirely under . . . the control of the Navy Department.12

Little progress was made in authorizing a reserve for the Navy and Marine Corps until Secretary of the Navy George V. L. Meyer (6 March 1909–4 March 1913) recognized the inadequacies of the militia system as a source of trained officers and men for the Navy and Marine Corps. Meyer twice called for legislation to move toward a viable solution.13 In December 1911, under his leadership, the Department of the Navy proposed legislation to the 61st Congress (1909–11) to create a “reserve of personnel for the U.S. Navy and Marine Corps and for its enrollment.”14

Need for a Marine Corps Reserve

While the need for a national Navy and Marine Corps reserve force had been building over the years, the operational tempo of the sea services had increased. In particular, the Marine Corps’ operational tempo in Central America, Mexico, and the Caribbean had been expanding since the Spanish-American War. Protecting American interests in Haiti, Veracruz, Nicaragua, and Santo Domingo kept Marines deployed, while manpower had grown only marginally.15 These demands, plus ships’ detachments, legation guards, and other requirements, strained the Corps’ resources and affirmed the need for a Marine Corps Reserve ready to meet emergent force requirements.

Marine Militia and National Naval Volunteers

The U.S. Marine Corps Reserve obtained much of its initial core of trained manpower from Marine units in the state naval militias. Finding records of Marines in state naval militias in the early days of America remains problematic, thus confirming the existence of the first Marine Corps unit in a state militia, after the Naval Appropriations Act of 1892, presents a challenge.

According to available records, the 1st Marine Corps Reserve Company, New York State Naval Militia, was activated in 1893.16 On 25 January 1994, New York Senator Alfonse M. D’Amato asked for and was granted permission to read into the congressional record part one of a two-part Naval Reserve Association News magazine article by two U.S. Navy Reserve/New York Naval Militia officers, Commanders Walter J. Johanson and William A. Murphy, on the history and importance of the naval reserve. It read, in part, as follows:

The Naval Militia, in addition to developing as a reserve for the Navy, was an incipient reserve for the Marine Corps as well. Starting in 1893, the New York Naval Militia included the 1st Marine Corps Reserve Company. Massachusetts and Louisiana also included units of Marines in their Naval Militia organizations.17

At the national level, the assistant secretary of war was charged with oversight of the state naval militias from 1891 to 1909. In December 1909, that responsibility was moved to the Personnel Division, Department of the Navy; and in 1911, the Office of Naval Militia was established and assumed oversight and support functions. Then in 1912, the U.S. Naval Militia functions were moved to the Navy’s Bureau of Navigation.18

Key references for identifying Marine units in state naval militias include the annual reports of the states adjutants general, which incorporate both national guard and naval militia information. In the annual adjutant general reports of the three states named in the above mentioned article—New York, Massachusetts, and Louisiana—the earliest mentioned Marine unit is in the Annual Report of the Adjutant General of the State of Louisiana for the Year Ending 1902. The report lists a Marine guard of 31 men in the 1st Naval Battalion, Louisiana Naval Militia (LNM), serving onboard the USS Stranger.19 The next year, that Marine guard increased to 49 militiamen and reported as Division G, 1st Naval Battalion, Naval Brigade, LNM. The militia continued to increase in number and in 1906, LNM added a second division, Division H, 1st Naval Battalion, Naval Brigade.20 In a reorganization of the Naval Brigade, Division H was disbanded on 5 September 1912, and the Marine militiamen consolidated into Division G.21

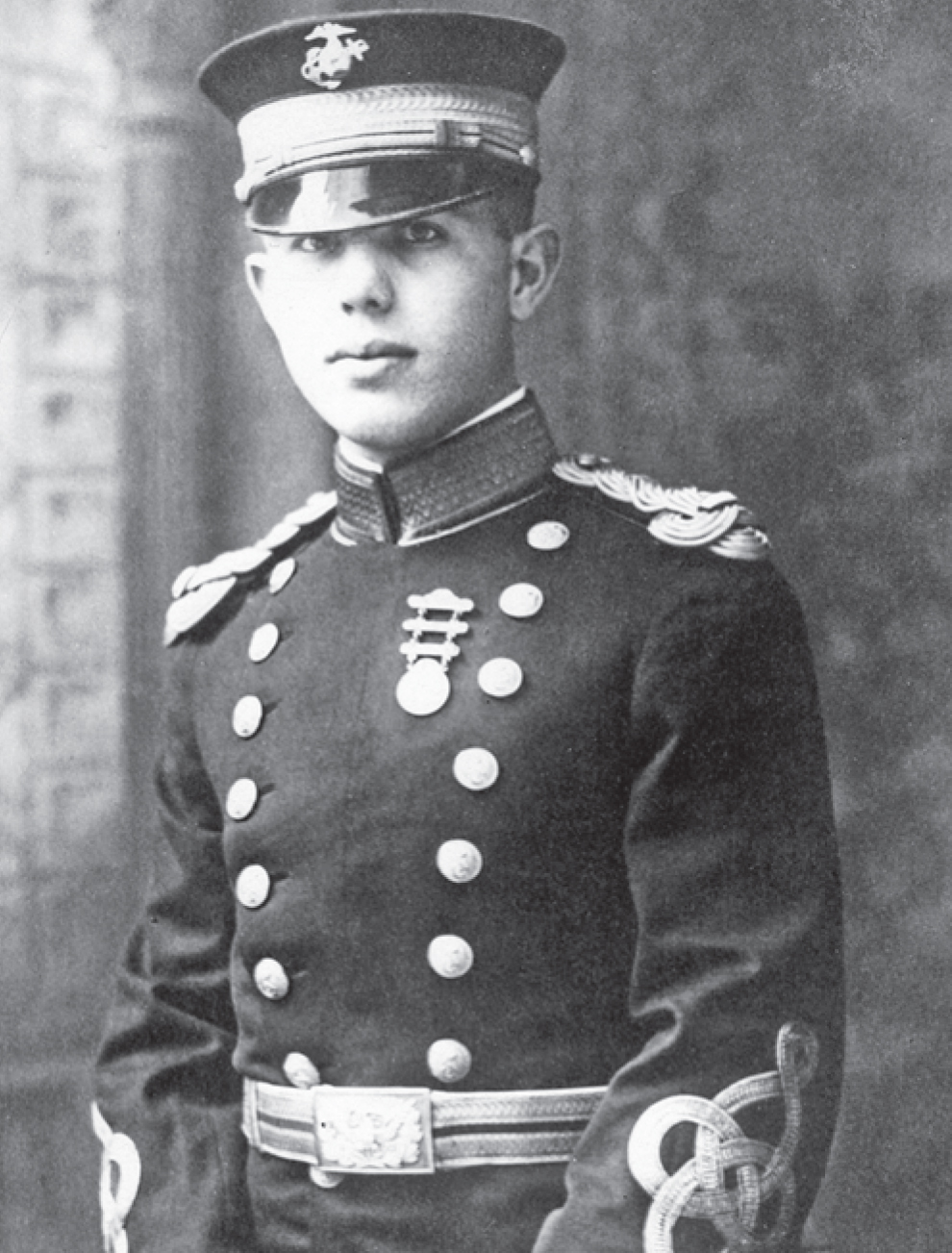

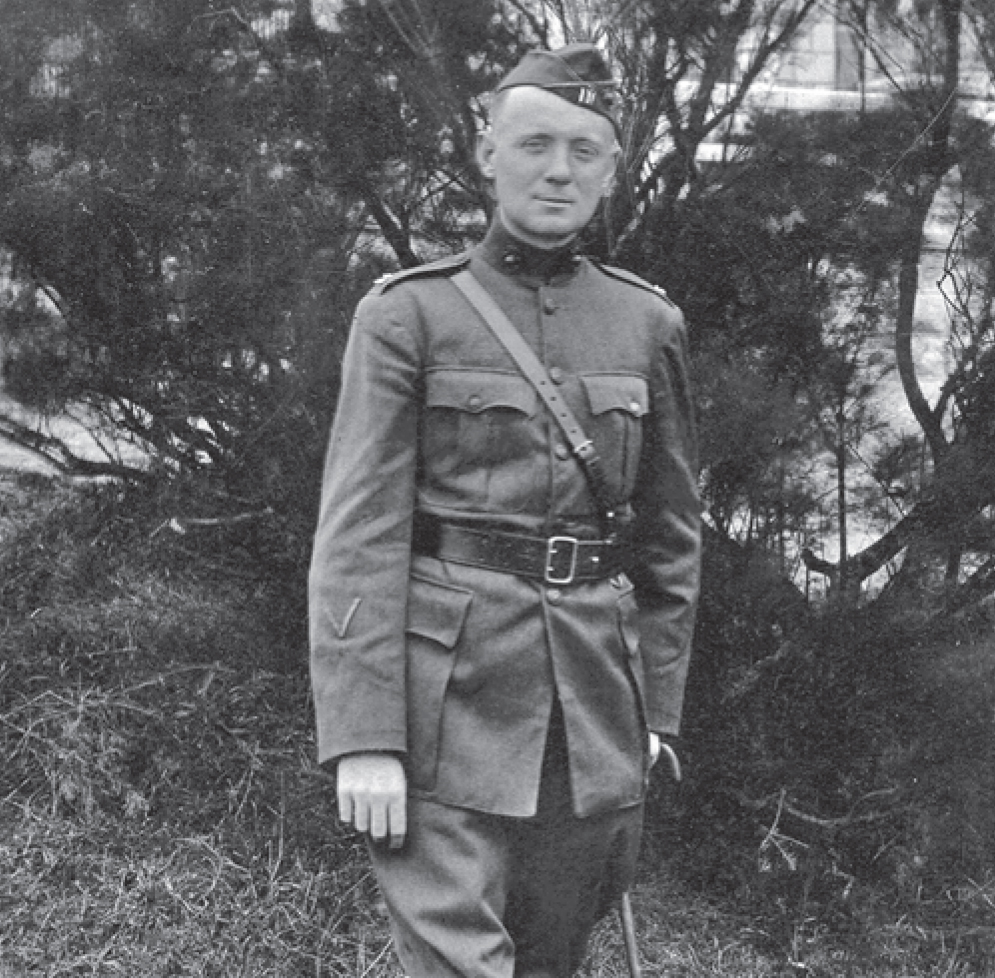

1stLt William A. Worton, Marine Branch, Massachusetts Naval Militia, in 1916 at age 16. Marine Corps History Division

In a report ending 31 December 1912, the adjutant general of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts noted the authorization of a Marine guard as part of a new naval militia battalion.22 In his report the following year, the adjutant general wrote, “For the first time in the history of the Naval Brigade, a Marine guard consisting of 1 commissioned officer and 25 enlisted” was formed.23

As a charter member of Marine Company, Massachusetts Naval Militia, William A. Worton served more than 30 years on active duty after World War I and retired as a major general in June 1949. His detailed record keeping, personal papers collection, and oral history maintained in the Marine Corps Archives and Special Collections Section of the Marine Corps University provide insight into the organization, arms, equipment, uniforms, and strength of the Marine units in the naval militia prior to and during the war. He mentions the formation of a Marine unit in the Massachusetts Naval Militia in May 1913 with Walter A. Powers, Assistant Attorney General for the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, appointed as a first lieutenant and named as the Marine Company’s first commander.24 A 1909 Harvard graduate, Powers’s credentials mirror those of many who joined the naval militia: well-educated and upwardly mobile. His militia records indicate he was mustered into the Massachusetts Naval Militia on 11 March 1911 and commissioned first lieutenant 27 March 1913.25

Beginning in 1892, the annual reports of the adjutant general of the state of New York included reports from the commander of the naval militia. However, the state’s report does not mention a Marine unit in the state naval militia until the annual report for 1916. That report cites an amendment to the federal law on naval militias approved 15 May 1916, addressing the composition, strength, and command of the state naval militias. In New York, the 1st Battalion, Naval Brigade, now included nine divisions and an aeronautic section; the 2d Battalion included seven divisions, one Marine company, and one aeronautic section; and the 3d Battalion included eight divisions. According to the 1916 annual report, the naval militia mustered from the Marine Company into the 2d Battalion on 1 May 1916. The company’s first commander was Lieutenant J. F. Rorke.26

The annual Register of the Commissioned and Warrant Oificers of the Naval Militia of the United States does not list a Marine unit in any state naval militia until the 1 January 1914 edition, which reported on units that were active in 1913.27 The sole Marine unit listed in 1914 was Marine Company, Massachusetts Naval Militia, Boston, with 1 officer and 31 enlisted men. A note in the 1914 edition indicates the state of Louisiana did not submit a report for 1913.28

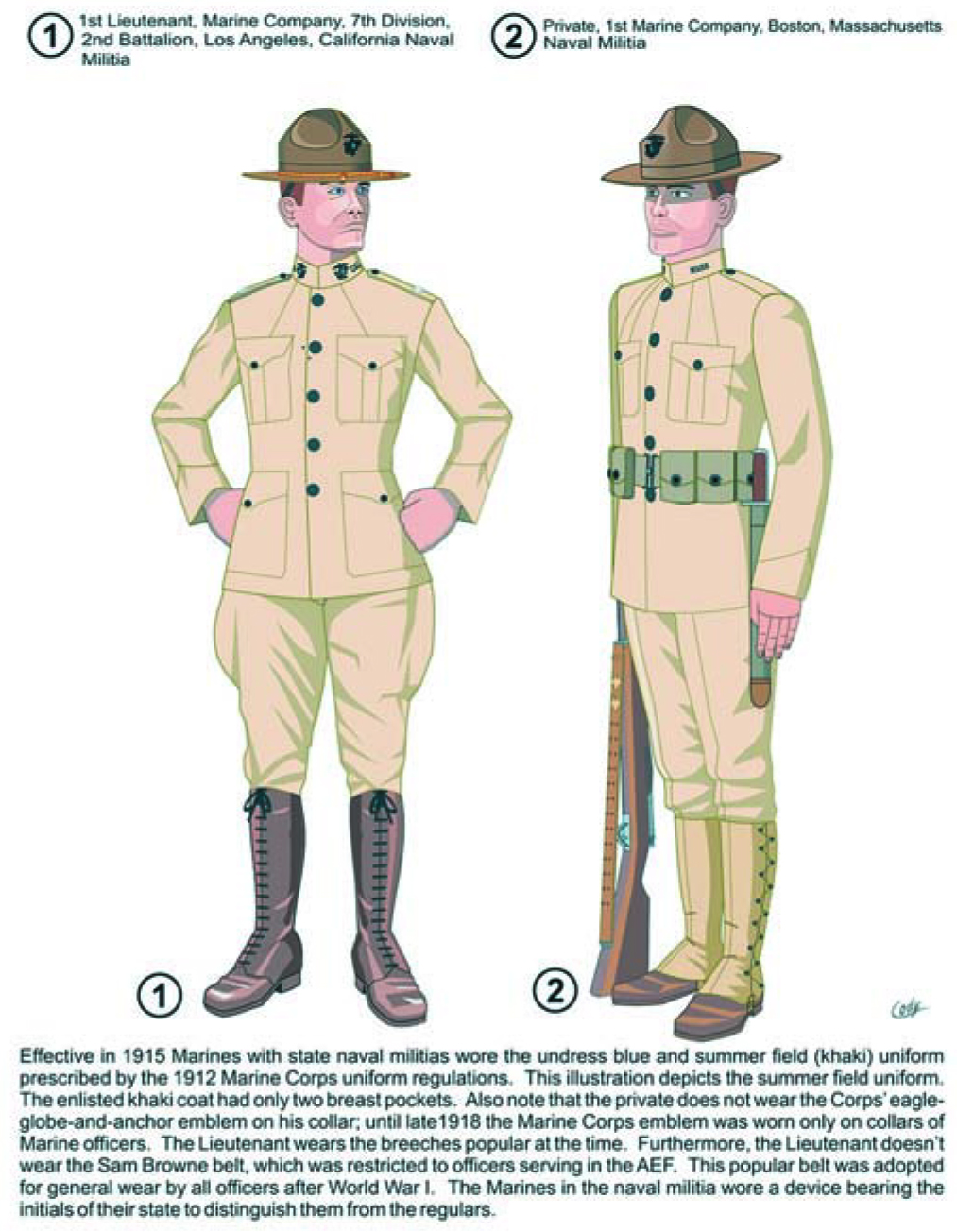

Uniforms of the Marines in the Naval Militia

In a 25 January 1915 letter to U.S. Navy Captain Frederic B. Bassett Jr., chief of the Navy’s Division of Naval Militia Affairs, Charles H. Power29 of 1st Battalion, Naval Militia, New York, asked for clarification on the uniforms, equipment, and ordnance for the state’s Marines. His question arose after learning in Washington that “Marines are to be allowed for the Naval Militia, and being about ready to muster in a detachment of one officer and twenty-four men.”30

Bassett forwarded the letter to Major General Commandant George Barnett on 30 January and stated in his endorsement that appropriations to support the Naval Militia Act would be used to purchase uniforms, equipment, and ordnance for enlisted men, but “no uniforms will be issued to officers, as this is contrary to precedent and there is not sufficient money available.” Bassett requested that Barnett define the uniform items and insignia for the Marines in the naval militias.31

In a response dated 3 February 1915, Barnett confirmed the enlisted uniform items to be supplied: “khaki, undress blue, campaign hat, undress cap, leggings, flannel shirt, and noncommissioned officers’ chevrons, and the regulation tan shoes.”32 He recommended that Marine officers in the naval militias “be required to equip themselves with khaki and blue, including cap, sword, belt, gloves, leather puttees, campaign hat, etc.” He continued with the following:

It is recommended that Marine officers and enlisted men of the Naval Militia wear the same rank devices and chevrons as in the regular service, and that they wear the Marine Corps insignia, with the same distinguishing mark that may be adopted for the Naval Militia.33

Uniforms of Marines in the Naval Militia. LtCol Richard L. Cody (Ret)

Calls for a United States Marine Corps Reserve

Although more federal funding and equipment were provided to the militia after the Spanish-American War, the militia remained an ineffective solution to a presidential call for forces in time of war. While the inadequacies of the militia system were becoming more apparent at this point, incremental improvements continued.34 The states’ naval militia organizational efforts progressed significantly with the 16 February passing of the Naval Militia Act of 1914.35 The act placed the Naval Militia under the supervision of the Department of the Navy, authorizing annual inspections, assigning active-duty naval officers as inspector-instructors for the units, establishing a board to standardize qualifications for all naval militia officers and enlisted men, and elevating the Office of Naval Militia within the Department of the Navy to the larger Division of Naval Militia Affairs under the Bureau of Navigation.36

Despite the 1914 Naval Militia Act, the state militia was not seen as the panacea for the ills associated with mobilizing a force in response to a presidential call. Major General Barnett took the oath of office as the 12th Commandant of the Marine Corps on 25 February 1914, just days after passage of the Militia Naval Act.37 Barnett and Secretary of the Navy Josephus Daniels began a series of meetings from which emerged a coordinated plan to increase the size of the Marine Corps and create a Marine Corps Reserve to meet the country’s ever-expanding expeditionary commitments and to provide a source for a manpower surge in the time of war.38

A demanding and decisive man of action with a natural bent for seeking efficiencies, Secretary Daniels issued a succinct implementation order for the 1914 Naval Militia Act two months after the legislation passed.39 In Department of the Navy General Order No. 93 of 12 April 1914, the secretary elevated the importance of the U.S. Naval Militia by enlarging the Office of Naval Militia and renaming it the Division of Naval Militia Affairs.40 In that order, he also decreed that communications between the states, territories, District of Columbia, and Department of the Navy would be through the new division. That division would be responsible for all business pertaining to the Naval Militia including “armaments, equipment, discipline, training, education, and organization of the Naval Militia.”41

Secretary of the Navy Josephus Daniels, 1913-21. Library of U.S. Congress, Harris & Ewing Collection

Secretary Daniels further interpreted the Naval Militia Act of 1914 in his expansive Navy Department General Order No. 153, wherein he more clearly defined the scope of Marine units in the Marine Corps Branch, Naval Militia, and specified that federal funding was contingent on naval militia units complying with the order’s provisions by 16 February 1917. In General Order 153, dated 10 July 1915, Daniels prescribed a “unit of organization” for the Marine element in the naval militias as a company with 3 officers and 48 enlisted, but noted the companies may be greater or lesser in strength, depending on availability of men. In the 103-page order, he also specified qualification requirements and prerequisites for the different ranks and billets, provided guidance on professional examinations for advancement, and authorized the formation of Marine battalions and brigades, if men were available. The order allowed for honorably discharged Marine veterans to join naval militias without a professional examination.42

As a senior colonel and then brigadier general, John A. Lejeune served in the billet of Assistant to the Commandant for MajGen Commandant George Barnett before taking command of Marine Barracks Quantico in September 1917. Photo courtesy of Leatherneck magazine

The secretary moved forward in organizing the naval militias and improving the professional skills of the militia members “in order that they will be eligible to be mustered into the service of the United States without further professional examination on the call of the president.”43 Barnett continued to press Congress for a ready reserve, noting that manpower was a paramount need and a standing reserve force would be of significant assistance. In his annual report for fiscal year 1915, submitted 1 December, Barnett stated that “The Marine Corps has no reserve. During the last session of Congress a naval reserve, consisting of men who have seen service in the Navy, was created. The adoption of a similar proviso for the Marine Corps is recommended.”44

In addition to formal testimonies promoting increased manpower and the creation of a Reserve, efforts moved forward on other fronts with Congress.

In his memoir The Reminiscences of a Marine, Major General John A. Lejeune, 13th Commandant of the Marine Corps, tells of becoming the Assistant to the Commandant in January 1915 while a colonel and working to ease the Marine Corps’ manpower deficiencies.45 General Lejeune noted that “probably the most important” undertaking while he was Assistant to the Commandant was his participation, along with Colonel Charles H. Lauchheimer, on the Navy and Marine Corps Personnel Board. The board worked with the House of Representatives for three months in the summer of 1915 to hammer out the manpower sections of the critically important Naval Appropriations Bill, which later became law.46

On 29 February 1916, Barnett, accompanied by Colonel Charles L. McCawley, quartermaster; Colonel George Richards, paymaster; and then-Colonel Lejeune, Assistant to the Commandant, testified before the House Committee on Naval Affairs. In his statement, Barnett once again strongly promoted the need for a Marine Corps Reserve.

Now, Mr. Chairman, I would like to refer to the matter of a Marine Corps reserve. The Marine Corps has no reserve. This is a very important matter, and it is urgently recommended that legislation similar to that enacted for the Navy be also enacted for the Marine Corps. During the last session of Congress the headquarters office of the Marine Corps urgently recommended the incorporation in the naval appropriation bill of a proviso for a Marine Corps reserve, and in the annual report of the Major General Commandant this recommendation was renewed.47

Congress Creates a Marine Corps Reserve

The clarion call by Daniels and Barnett for a formal Reserve was finally heard. On 29 August 1916, the Sixty-Fourth Congress, in its first session, authorized a Reserve in H.R. 15947. Specifically, on the creation of the Reserve, the legislation set forth the following:

A United States Marine Corps Reserve, to be a constituent part of the Marine Corps and in addition to the authorized strength thereof, is hereby established under the same provisions in all respects (except as may be necessary to adapt the said provisions to the Marine Corps) as those providing for the Naval Reserve Force in this Act: Provided, That the Marine Corps Reserve may consist of not more than five classes, corresponding, as near as may be, to the Fleet Naval Reserve, the Naval Reserve, the Naval Coast Defense Reserve, the Volunteer Naval Reserve, and the Naval Reserve Flying Corps, respectively.48

The legislation addressed the manpower needs of the Navy and Marine Corps and ultimately gave the president more authority to mobilize the U.S. Naval Militia. The congressional work to finally improve the president’s access to the Naval Militia also created a new organization, the National Naval Volunteers, into which the president could order members of the Naval Militia and then federalize, or bring onto active service, those trained militiamen for war or other needs. Regarding the National Naval Volunteers, the legislation announced

that to provide a force for use in any emergency, including that of actual or imminent war, requiring the use of naval forces in addition to those of the regular Navy, of which emergency the president shall be, for the purposes of this Act, the sole judge, there is hereby created a force, to be known as the “National Naval Volunteers,” into which the President alone is authorized, under such regulations as he may prescribe, to at any time enroll, by commission, warrant, and enlistment, respectively, and without examination, such number as he may decide to enroll from among those of the Naval Militia.49

The secretary of the Navy moved quickly to publish the legislation through Navy Department channels. General Order No. 231, dated 31 August 1916, reprinted the legislation for the “information and guidance of all persons belonging to the Navy.”50

While the legislation creating the Marine Corps Reserve directed that it consist of not more than five classes, similar to the Naval Reserve Force, the Marine Corps took time to evaluate the next step and did not clarify or define those classes until months later. Marine Corps Order No. 13 (series 1917), dated 21 March 1917, laid out the Marine Corps’ expected implementation of that legislation and defined the five classes in the Reserve for men.51

The earlier efforts of the members of the Navy and Marine Corps Personnel Board also paid off as an increase in manpower was authorized in the August 1916 legislation. The Marine Corps was granted an immediate increase in officers from 344 to 597, and in enlisted men from 9,921 to 14,981. The legislation also authorized the president to further increase the number of officers to 693 and enlisted men to 17,400 in an emergency.52

Classes of Marine Corps Reserve

On 29 August 1916, congressional legislation created the Marine Corps Reserve. Subsequently, Marine Corps Order No. 13, dated 21 March 1917, laid out the implementation of that legislation, creating five classes of Marine reservists for males. Legislation and the Marine Corps order did not address women in the Marine Corps Reserve because Secretary of the Navy Josephus Daniels did not grant the Marine Corps permission to enroll women in the Reserve until 12 August 1918.

Class 1: Fleet Marine Corps Reserve (FMCR)

1a. Officers honorably discharged.

1b. Men entitled to an honorable discharge after at least one four-year enlistment.

1c. Enlisted men who completed 16 years of honorable service and were transferred to the FMCR at the expiration of enlistment.

1d. Enlisted men who completed 20 years of honorable service.

Class 2: Marine Corps Reserve A

All enrollments were restricted to U.S. citizens, and the commitment was for four years.

2a. Officers, provisional: must not be less than 20 or more than 40 years of age; not less than two years’ experience as an officer in a military organization or military school or college; and pass a physical and professional examination.

2b. Officers, confirmation: after three months active service, must pass another professional examination by a board of officers and a physical examination to retain the provisional rank granted at enrollment.

2c. Enlisted men, provisional: must not be less than 18 or more than 35 years of age and of good character and show evidence of abilities.

2d. Enlisted men, confirmation: after three months active service, could be confirmed in provisional rank by an appointed Marine Corps officer.

Class 4: Marine Corps Reserve

This class was for citizens with useful skills and had no age limit. Those enrolled could subsequently transfer to Class 2, if eligible. Often underage or overage men took advantage of this category.

4a. Officers, provisional: must show proof of special skills needed in naval and reserve districts and pass a professional and physical examination.

4b. Officers, confirmation: same as Class 2, 2b.

4c. Enlisted men, provisional: must provide evidence of character and citizenship and proof of needed special skills and pass a medical examination. The provisional rank given was based on skills of the applicant and the requirements of the district.

4d. Enlisted men, confirmation: same as Class 2, 2d.

Class 5: Marine Corps Reserve Flying Corps

Former officers and men of the Marine Corps who were members of the Naval Flying Corps, surplus graduates of the aeronautic school, civilians skilled in flying, building or designing aircraft, and other current members of the Marine Corps Reserve with aviation skills could enter this Marine Corps Reserve class.

5a. Officers, provisional: must provide proof of character and citizenship, qualify through a professional examination, and pass a medical examination.

5b. Officers, confirmation: honorably discharged former officers of the Naval Flying Corps and surplus graduates of the aeronautical school could be designated in this class without a prior provisional appointment. Marines appointed with a provisional rank must serve three months’ active duty service and be confirmed to that provisional rank through a professional examination and a medical examination.

5c. Enlisted men, provisional: must provide proof of character, ability and citizenship and qualify through a professional examination for a provisional rank and pass a medical examination. This class had no age limit.

5d. Enlisted men, confirmation: honorably discharged men of the Naval Flying Corps after at least one four-year enlistment in the Navy and those who were discharged after a term of enlistment. After three months’ active duty service, a member could be confirmed in his provisional rank by qualifying before a designated Marine Corps officer.

5e. Any enlisted Marine with 16 years’ service could transfer, with the authority of the Major General Commandant, at the end of his current enlistment contract to the Marine Corps Reserve Flying Corps if all other Class 5 requirements were met.

5f. Any enlisted Marine with 20 or more years enlisted service could transfer, with authority of the Major General Commandant, to the Marine Corps Reserve Flying Corps.

Class 6: Volunteer Marine Corps Reserve

This class was comprised of men who met the qualifications for the above classes and committed themselves but waived their retainer fee and uniform gratuity in time of peace. When called to active duty service in wartime, their pay was the same as the corresponding rank in the Marine Corps.

|

Transfer of Personnel of the National Naval Volunteers, Marine Corps Branch, to Marine Corps Reserve

While the intent of the 1916 legislation was to create the Marine Corps Reserve and provide the president access to a trained militia in time of an emergency, the creation of the National Naval Volunteers caused confusion since both it and the Naval Militia had Marine Corps branches. Congress addressed the issue with an amendment to an appropriations bill for naval services on 1 July 1918, authorizing the president to transfer all personnel of the National Naval Volunteers as a class to the Naval Reserve Force, or the Marine Corps Reserve.53

On 10 July 1918, Barnett issued Marine Corps Order No. 34 (series 1918), stating that “from and including July 1, 1918, the personnel of the National Naval Volunteers, Marine Corps Branch, is transferred from that organization to Class 2, Marine Corps Reserve . . .” The order also confirmed that, in accordance with the congressional action, individuals transferred to the Reserve would retain their ranks on a provisional basis. Also, the Reserve would not conduct medical examinations or tests to gauge the professional competence of those brought in via transfer.54

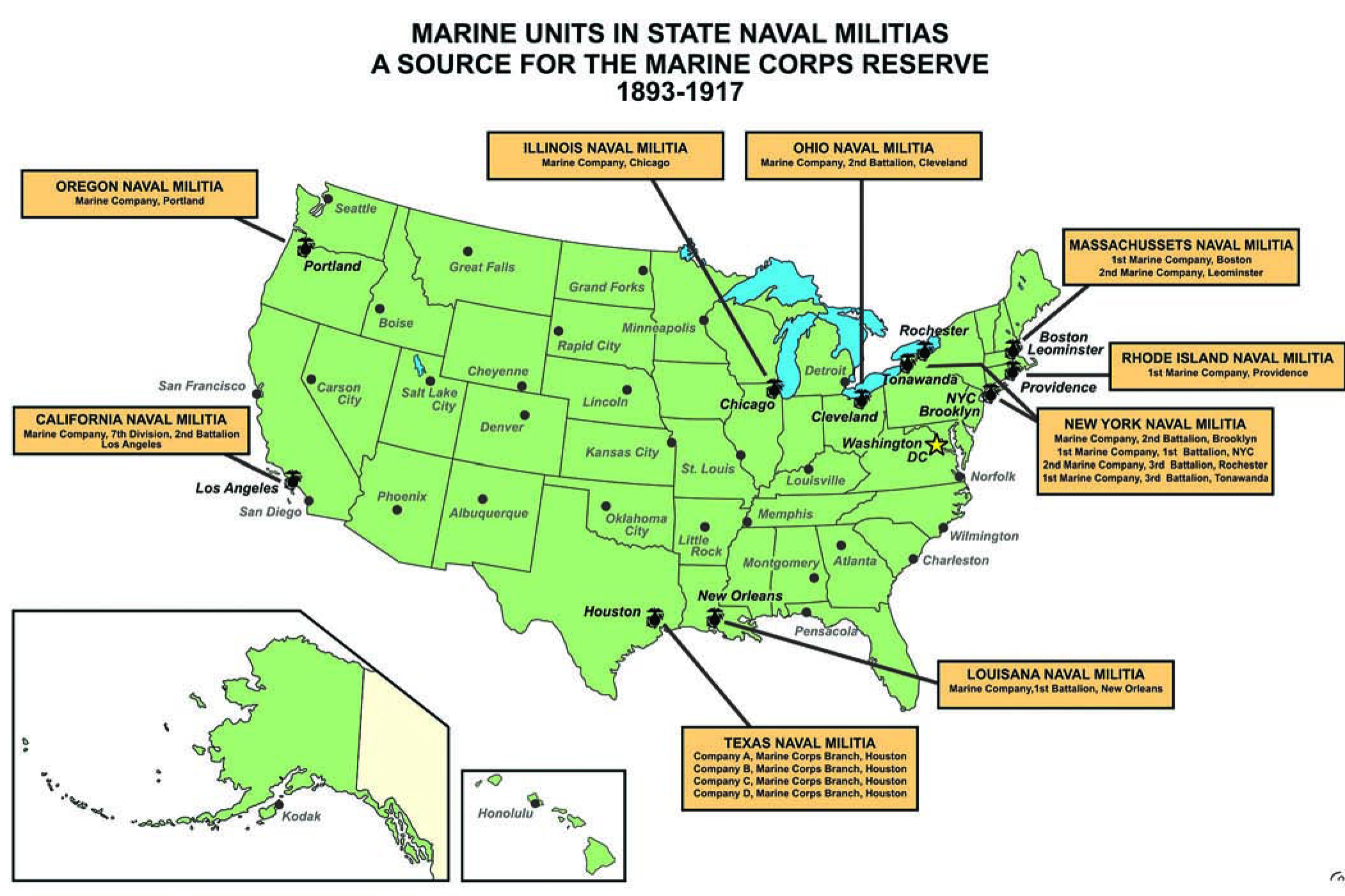

Barnett then sent letters to the adjutants general of those states with National Naval Volunteers or Marine branches in their naval militias, informing them of his actions. Those letters, dated 11 July 1918, went to the nine states with Marine units: California, Illinois, Louisiana, Massachusetts, New York, Ohio, Oregon, Rhode Island, and Texas. The letters noted that should the Marine reservists who entered from state organizations be discharged from the Reserve, the adjutants general would be informed. Barnett then signed a letter that same day to the chief of the Division of Naval Militia Affairs, Bureau of Navigation, Department of the Navy, informing him of the actions to bring the militiamen and National Naval Volunteers into the Reserve.55

MajGen Commandant George Barnett (1914–20) oversaw the largest expansion in Marine Corps manpower up to that time in the history of the Corps. Marine Corps History Division

The Philadelphia Military Training Corps

Recruiting for the Reserve was slow to begin, hampered by the fact that guidance on the different classes of reserves was not published by the Marine Corps until March 1917. When war was declared on 6 April 1917, the Reserve had just 3 commissioned officers and 36 enlisted men to call for active duty. The Marine Corps Branch of the National Naval Volunteers had 24 officers and 928 enlisted men, also subject to the call for active duty.56

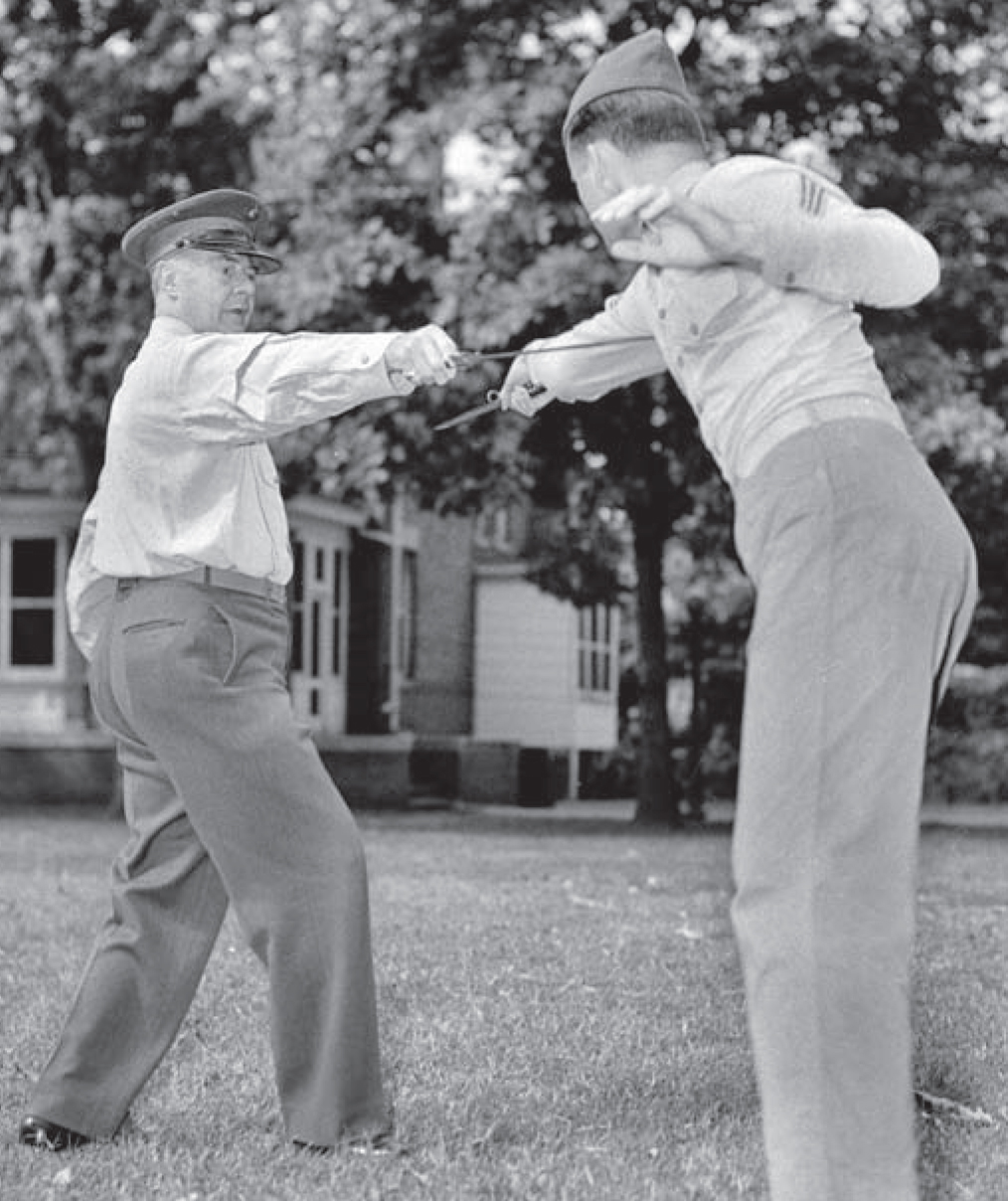

However, efforts not associated with the naval militia programs became a valuable source of trained manpower. Civilian military training programs, particularly the Philadelphia Military Training Corps—established with the resources of wealthy, conservative Philadelphian Anthony J. Drexel Biddle—garnered positive Marine Corps exposure and enlistments in the Reserve.

Biddle was among a group of influential individuals who foresaw America’s eventual involvement in World War I. In October 1915, with the consent of Barnett, Biddle created a training camp at Lansdowne, Pennsylvania, conducted by Marine noncommissioned officers from Marine Barracks Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. After the close of the camp, Marines from the Philadelphia barracks led periodic drills throughout the winter. Those trained in the camp became known as the “Drexel Biddle Citizens’ Army,” and by April 1916, more than 3,000 men had completed training. At that point, U.S. Representative Thomas S. Butler of Pennsylvania introduced a bill, which was approved, to provide $31,000 for the Marine Corps to train citizen soldiers.57

Also in April 1916, Biddle invited Barnett to speak at a Philadelphia Preparedness Campaign Committee dinner focused on raising money for a citizens’ army. The dinner afforded another opportunity for the Commandant to promote a citizens’ army, reinforcing his quest to pressure Congress into creating a Marine Corps Reserve. Pledging his support for the preparedness campaign, Barnett ordered Captain Logan Feland from Marine Barracks Philadelphia to command training during the summer of 1916 at Lansdowne.58

On 23 July, thousands of civilians attended the camp’s opening ceremony, and Barnett conducted a formal inspection. At the end of training on 28 August, the Commandant returned to review the graduation parade. During the closing ceremony, Captain Feland called on the graduates to join the Reserve, and 74 percent of the men volunteered.59 At age 43, Biddle enrolled as a captain in the Reserve, Class 4, on 31 March 1917, not long before war was declared.60 By that time, the millionaire sportsman and philanthropist had significantly refined his combat skills and influenced many of Philadelphia’s finest to join the Reserve. One report stated that Biddle’s Philadelphia Military Training Corps recruited 40,000 men for the military, including 8,900 for the Marine Corps.61 Biddle, initially assigned as a bayonet instructor at the new training site, Marine Barracks Paris Island, [sic] South Carolina,62 (name changed to Parris Island in 1919), became an instructor at the Marine officer training camp at Marine Barracks Quantico, Virginia, by the fall of 1917. While there, he was sent as an observer to study both the French and British close combat training.63

Logan Feland, as a captain in 1916, was instrumental in successfully recruiting men into the Marine Corps Reserve from the Philadelphia Military Training Corps. Photo courtesy of Leatherneck magazine

Anthony J. Drexel Biddle, a millionaire philanthropist who helped form the Philadelphia Military Training Corps prior to WWI, enrolled as a captain in the Marine Corps Reserve in 1917 and taught personal combat techniques until released from active duty in 1919. Photo courtesy of Leatherneck magazine

Upon his return from Europe in the spring of 1918, Biddle was assigned as an instructor in the Infantry Officers’ School at Marine Barracks Quantico, teaching bayonet, knife fighting, and hand-to-hand combat. He continued to prepare officers for war through the Armistice, transferring from Quantico to Marine Barracks Philadelphia on 1 January 1919, where he served as the athletics officer until being released from active duty in July 1919.64

Biddle’s initiatives promoting civilian readiness indirectly helped to push legislation that created the Reserve and greatly assisted in providing trained manpower for America’s war effort. For the next three decades, Biddle continued to serve as a Marine Corps reservist. Biddle returned to active duty briefly in World War II as a colonel, still spry and effective as an instructor in bayonet fighting, boxing, and jujitsu.65

Nine U.S. states included Marine Corps units in their naval militias at the beginning of WWI. They were mobilized as National Naval Volunteers (Marines). LtCol Richard L. Cody (Ret)

Mobilization in the Naval Militia, National Naval Volunteers, and Marine Corps Reserve

As America moved toward war, recruitment numbers for the Marine Corps Branch of the Naval Militia topped out at 1,046 men on 1 April 1917. Recruitment for the militia had stopped while recruiting efforts for the Reserve picked up.66 Just as America declared war on 6 April 1917, the Reserve and Naval Militia mobilized that same day. Nearly all members of the Naval Militia volunteered for enrollment in the National Naval Volunteers.67 The recruiting environment significantly changed as patriotic fervor spread; three Marine Reserve companies, designated 1st, 2d and 3d Reserve Companies, 68 were immediately recruited in Philadelphia, many most probably sourced from Drexel Biddle Citizens’ Army, and began training at the Philadelphia Navy Yard.

Militia and National Naval Volunteers

After members of the state militias and National Naval Volunteers were mustered into federal service, members of the Marine units were ordered to rendezvous sites and then dispatched to various naval stations. Upon arriving at these naval stations, the Marine Corps disbanded the units and men were brought into the Marine Corps and sent to Marine installations to join units based on the needs of the Marine Corps. Some officers in the Marine Corps Reserve and National Naval Volunteers applied for temporary appointments in the regular Marine Corps with the goal of becoming regular active duty officers. Noncommissioned officers were tested and evaluated to confirm their ranks and determine their occupational ratings.69

Uniforms

As the Marine Corps grew in numbers with the influx of Marines from the National Naval Volunteers and Reserve, Barnett extended the uniform guidance given to Marines in the state naval militias to Marines serving in the National Naval Volunteers and Reserve.

Marine Corps Order No. 17 (series 1917), signed 14 April 1917, directed that officers and enlisted men of the National Naval Volunteers and the Reserve wear the same uniforms as officers and enlisted men of the regular Marine Corps but with a distinguishing device. Officers in the National Naval Volunteers wore a metal “V” on their coat collars, overcoat shoulder straps, and field hats. Enlisted men of the National Naval Volunteers wore a metal “V” on the field hat. Reserve officers wore a metal “R” on the collars of “undress, white, and field coats and on the shoulder straps of the overcoat.” Reserve officers also wore the metal “R” on “the field hat with the bottom of the letter resting on the top of the hatband” and centered underneath the “eyelet for the corps device.”70

After being called to federal service in 1917, 2dLt Newton Best, California Naval Militia (Marines), was assigned as the post athletics officer for Marine Barracks Mare Island. Marine Corps History Division

Training

With a small Reserve at the beginning of World War I, the multitude of young men who volunteered at the onset of the war overwhelmed the Marine recruit depots. The two Marine Corps recruit training sites for enlisted men—Paris Island [sic] and Mare Island—were initially unprepared for the growth in the number of recruits. While the facilities were being expanded, a temporary recruit depot with capacity for 2,500 recruits was established at the Philadelphia Navy Yard. Another temporary recruit training facility with a capacity for 500 opened at the Norfolk Navy Yard. By the end of the war, the Marine Corps had significantly enlarged both primary recruit training facilities and set the duration of training at eight weeks.87

Table 1. Marine Corps Reserve Units Activated for the First World War

|

Unit

|

Activated

|

Commander

|

Location

|

|

Marine Company, 7th Division, 2d Battalion, California Naval Militia became 36th Company

|

6 April 1917

|

Capt Newton Best

|

Exposition Park, Los Angeles moved to Marine Barracks Mare Island, California71

|

|

Marine Company, 1st Battalion, Louisiana Naval Militia, New Orleans

|

6 April 1917

|

Capt Sidney S. Simpson

|

Marine Barracks Naval Station New Orleans72

|

|

1st Marine Company, Massachusetts Naval Militia, Boston

|

27 March 1917

|

Capt George H. Manks

|

Charlestown (Boston) Navy Yard73

|

|

2d Marine Company, Massachusetts Naval Militia, Leominster, Massachusetts

|

9 May 1917

|

1stLt James R. Walsh (discharged 18 June 1917)

|

Charlestown (Boston) Navy Yard74

|

|

Marine Company, 2d Battalion, New York Naval Militia, Brooklyn

|

6 April 1917

|

1stLt James F. Rorke

|

Northport, New York, power station75

|

|

1st Marine Company, 1st Battalion, New York Naval Militia, New York City

|

26 April 1917

|

1stLt Stanford W. Hoffman

|

Marine Barracks Brooklyn Navy Yard, New York76

|

|

1st Marine Company, 3d Battalion, New York Naval Militia, Tonawanda

|

7 April 1917

|

1stLt Alan V. Parker

|

Marine Barracks Brooklyn Navy Yard77

|

|

2d Marine Company, 3d Battalion, New York Naval Militia, Rochester

|

7 May 1917

|

2dLt Clarence Ball

|

Marine Barracks Brooklyn Navy Yard78

|

|

Marine Company, 2d Battalion, Ohio Naval Militia, Cleveland

|

7 April 1917

|

1stLt Jonas H. Platt

|

Marine Barracks Brooklyn Navy Yard79

|

|

Marine Company, Oregon Naval Militia, Portland

|

6 April 1917

|

2dLt Richard I. Heller

|

Marine Barracks Puget Sound Navy Yard, Washington80

|

|

Company A, Texas Naval Militia

|

6 April 1917

|

Capt Thomas R. Shearer

|

Marine Barracks Pensacola, Florida81

|

|

Company B, Texas Naval Militia

|

6 April 1917

|

Capt Percy D. Cornell

|

Marine Barracks Pensacola, Florida82

|

|

Company C, Texas Naval Militia

|

6 April 1917

|

Capt William N. Pearson

|

Marine Barracks Charleston Navy Yard, South Carolina83

|

|

Company D, Texas Naval Militia

|

6 April 1917

|

Capt Angus A. Acree

|

Marine Barracks Norfolk Navy Yard, Virginia84

|

|

1st Marine Company, Rhode Island Naval Militia, Providence

|

6 April 1917

|

Capt John H. Sadler

|

Marine Barracks Boston Navy Yard85

|

|

Marine Company, Illinois Naval Militia, Chicago

|

6 April 1917

|

Capt Franklin T. Steele

|

Marine Barracks Philadelphia Navy Yard86

|

The Marine Corps pursued officers differently. Before legislation authorized the formation of a Reserve in August 1916, Commandant Barnett brought 18 of the best Marine noncommissioned officers to Washington, DC, for officer testing. On 7 August, 12 enlisted Marines passed the exam. After legislation for the Reserve was approved, the Commandant sent a letter to colleges with military training curriculums offering graduates the opportunity to take an examination on 18 September 1916 to become a Reserve officer. Only 24 candidates passed the exam, so the Commandant offered a second examination (military training was not necessary) in November 1916 for any civilian.88

Officers appointed directly from civilian life went to the Marine barracks at Mare Island and San Diego, California; the Marine Corps Rifle Range Winthrop, Maryland; and Paris Island 89 [sic] until the Officers Camp of Instruction could be opened at Marine Barracks Quantico. The first contingent of 345 untried, new lieutenants arrived at Quantico in July 1917.90

Clarence Ball

|

|

Clarence Ball, a member of the Sons of the American Revolution, Empire State Society, enlisted in the New York Naval Militia in Rochester in 1892 and served as a petty officer in the U. S. Navy during the Spanish-American War, was promoted to first lieutenant in the Marine Corps Branch, New York Naval Militia in August 1917 and ordered to the officers training camp in Quantico, Virginia. He joined the 5th Regiment in France in June 1918 in time for the beginning of the battle of Belleau Wood on 6 June. Ball fought at Soissons, the Saint-Mihiel salient, and the Champagne sector. During the battle of Blanc Mont Ridge, he assumed command of Company M, 5th Regiment, after the commanding officer was wounded and evacuated. Hospitalized for wounds received during his time in the Champagne sector, Ball yielded command in early November 1918 and was evacuated back to the United States.1

Ball was cited for gallantry in action while serving with the 5th Regiment (Marines), 2d Division, American Expeditionary Forces, at Château-Thierry, France, 6–10 July 1918 and authorized to wear a silver star “on the ribbon of the Victory Medals awarded him.”2 Ball was honorably discharged from the Marine Corps Reserve on 6 October 1919 as a captain.3

|

- Edward R. Foreman, ed., World War Service Record of Rochester and Monroe County New York, vol. 2, Those Who Went Forth to Serve(Rochester, NY: City of Rochester, 1928), 58.

- “Clarence Ball,” Hall of Valor, http://valor.militarytimes.com/recipient.php?recipientid=75048,1910.

- “Barracks Detachment, Marine Barracks Quantico, VA, MRoll, 1 October–31 October 1919,” roll 0181, ancestry.com.

|

Capt Jonas H. Platt resigned from the National Naval Volunteers to accept a regular commission in the Marine Corps in September 1917. He earned a Navy Cross and a Purple Heart in the battle of Bois de Belleau on 6 June 1918. Marine Corps History Division

In June 1917, after success in these early efforts, the Commandant issued Marine Corps Order No. 25 (series 1917), discontinuing the enrollment of civilians because he believed this source for officers was no longer required. Instead, the Marine Corps would appoint graduates of the U.S. Naval Academy and enlisted men who distinguished themselves in active service.91

John W. Thomason Jr. enlisted as a private in the Texas Naval Militia, mobilized as a gunnery sergeant with Company A, Texas Naval Militia, then commissioned in Company C. He gained fame as an author and illustrator and passed away in 1944 as a Marine colonel. Marine Corps History Division

Capt Franklin T. Steele, Naval Militia Illinois, accepted a regular commission in the Marine Corps and served in the Heavy Artillery Force, Marine Barracks Quantico during WWI. Marine Corps History Division

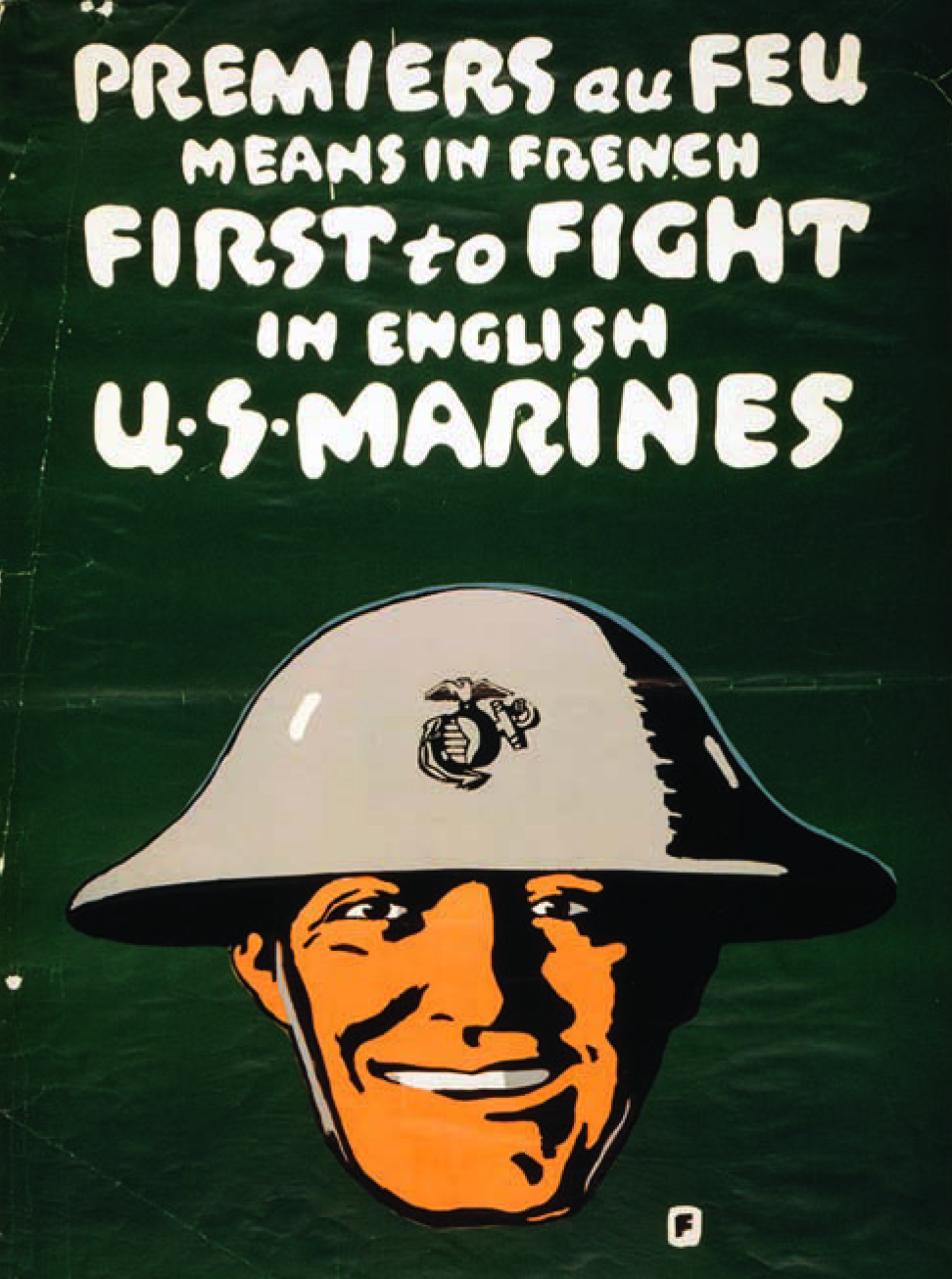

In April 1917 at the beginning of U.S. involvement in World War I, more than 50 percent of active duty U.S. Marines (13,725) were serving outside the continental United States, either onboard U.S. Navy ships (2,236) or ashore (4,733).92 With the adopted slogan of “First to Fight,” the Marine Corps quickly carved out the 7th, 8th, and 9th Regiments for the continuing commitments of the Advanced Base Force, with all remaining regiments intended for the American Expeditionary Forces (AEF).93

At that time, Marine Corps manpower was stretched. However, with the assistance of the emerging Reserve and National Naval Volunteers, the Marine Corps filled a request from Secretary of War Newton D. Baker Jr. for a regiment of Marines to be part of the AEF in France. Within weeks, the Marine Corps’ 5th Regiment sailed from Philadelphia.94

The regiment officially organized at the Philadelphia Navy Yard on 7 June 1917, just one week prior to departing for France on 14 June.95 Commanded by Colonel Charles A. Doyen, the regiment consisted of 70 officers and 2,689 enlisted men96 drawn from ship detachments, naval stations, and barracks plus newly enlisted men from the Reserve and National Naval Volunteers.97 The Reserve was of critical importance when the Marine Corps was called to war quickly; for example, 75 of the 123 Marines of the regiment’s Supply Company were reservists. Most of these men came from 1st and 2d Marine Reserve Companies in training in Philadelphia.98 The June muster rolls for 5th Regiment units included 16 Reserve officers, 1 officer in the National Naval Volunteers, Marine Branch, 88 Reserve enlisted men, 74 enlisted men in the National Naval Volunteers, and 2 enlisted men in the U.S. Naval Militia, Marine Branch, who had not yet been brought into the National Naval Volunteers.99

MajGen Commandant George Barnett inspects the sights and action of a Lewis machine gun at the Marine Corps Rifle Range Winthrop, MD, in 1917. Library of Congress, Harris & Ewing Collection

Premiers au feu means “First to Fight” in English, and the Marines meant to live up to that reputation by getting to France with the American Expeditionary Forces in June 1917. Library of Congress, Charles Buckles Falls, World War I Posters Collection

Many reservists and National Naval Volunteers in the AEF ground forces in France were in units of the 4th Brigade, 2d Division.100 The brigade earned honors from actions taken in the Aisne defensive and the battles at Hill 142, Bouresches, and Belleau Wood—which garnered international recognition for U.S. Marines—and at Soissons, Saint-Mihiel, Blanc Mont, the crossing of the Meuse River, and during the occupation of Germany, all of which motivated U.S. Marines and instilled the Marine Corps in the hearts of Americans.

The Marine Corps Reserve during the War but Not “Over There”

While most of the mobilized Marine Corps Reserve, U.S. Naval Militia, and National Naval Volunteers were deployed with units in France, many remained in the United States at bases and stations, some were in U.S. Navy ships’ detachments and others were with Marine units scattered around the globe.

As America’s involvement in World War I became unavoidable, bands of rebels created unrest and disturbed sugar production in Cuba. As early as March 1917, Marines deployed from Haiti to Cuba to ensure the continued safety of the Allied sugar supply. With continued disruption of sugar-producing efforts and an outcry from American sugar producers, the Marine Corps activated the 7th Regiment, one of the Advanced Base Force regiments, in Philadelphia on 14 August 1917 under Lieutenant Colonel Melville J. Shaw.101 The regiment arrived in Guantanamo Bay, Cuba, on 27 August 1917.102

With significant efforts to assemble a fighting force for Europe, filling out the 7th Regiment for Cuba required Reserve participation, specifically for the headquarters company. Marine regiments, at this time, were not organized in battalions but were formed for expeditionary service with a headquarters and a varying number of companies based on the need.103 The 7th Regiment included a headquarters company and eight infantry companies. Of the 120 men in Headquarters Company, 7th Regiment, 42 were reservists and all transferred in from the 1st Marine Reserve Company, Marine Barracks Philadelphia.104 The eight companies in the regiment—37th, 59th, 71st, 72d, 86th, 90th, 93d, and 94th—were less dependent on the Reserve for men. However, two of the three officers in each company were reservists except in 59th Company, which had one Marine Corps Regular, one Reserve, and one officer from the National Naval Volunteers.105

Oil was another resource critical to the Allied war effort. The U.S. Navy and Allies were dependent on the Mexican oil fields, but deteriorating relations and continued turmoil in Mexico in 1917 caused concern about undisrupted oil supply. The infamous “Zimmermann Telegram” prompted action.106 To ensure the flow of oil from Mexico and to promote stability in relations with Mexico, once again the president turned to the Marine Corps for a ready reserve force, and the Corps responded with the 8th Regiment.

The 8th Regiment of the Advanced Base Force was activated at Marine Barracks Quantico on 9 October 1917 under the command of Major Ellis B. Miller. The 8th Regiment became an infantry regiment with a headquarters and three companies—105th, 106th, and 107th. Within the month, it added 103d, 104th, 108th, 109th, and 110th Companies from Marine Barracks Mare Island, and two additional companies were organized from men at Marine Barracks Quantico—111th and 112th Companies.107 Once again, the Reserve helped the Corps quickly field the new regiment. The regiment’s Headquarters Company stood up on 9 October with 39 men on its muster roll, 20 of whom were reservists.108 Each of the companies, except the 109th and 111th, included Marine Corps reservists and National Naval Volunteers.109 On 2 November 1917, Colonel Laurence H. Moses arrived at Quantico from Marine Barracks New York and assumed command of the regiment the next day. Then, exactly one month after being activated, the 8th Regiment boarded USS Hancock (AP 3) and, on 10 November 1917, sailed for Fort Crockett, Texas, on Galveston Island and arrived on 18 November.110 The regiment’s mission was to prepare to move swiftly to land on the Mexican coast and seize the major oil fields near Tampico, Mexico. The 8th Regiment, joined by 9th Regiment in August 1918, remained at Fort Crockett under the command of 3d Provisional Brigade until early 1919.111

Marines in France dig trenches during training for battle. Library of Congress, United States Army Signal Corps

The third regiment intended for the Advanced Base Force—the 9th Regiment—was formed at Marine Barracks Quantico on 20 November 1917 with a headquarters, one machine gun company, the 14th Company, and eight rifle companies—36th, 100th, 121st, 122d, 123d, 124th, 125th, and 126th.112 Again, the Reserve and the National Naval Volunteers played a key role. The headquarters of the newly formed 9th Regiment had 22 men on its muster roll on the day the regiment was activated, and 19 were Marine Corps reservists.113 On 20 November, the 36th Company, 9th Regiment, had 4 Marine Corps reservists and 41 National Naval Volunteers to a total strength of 117 men.114 While the 100th Company reported only 1 Marine Corps reservist and 7 National Naval Volunteers to a strength of 111 men,115 the remaining five companies, 121st through 126th, reported no Marine Corps reservists or National Naval Volunteers on their muster rolls.116

Secretary of the Navy Josephus Daniels visits Marines during training at the newly activated Marine Barracks Quantico in 1918. Library of Congress, Harris & Ewing Collection

Numbers Reflect Wartime Significance of the Reserve

An examination of the “General Recapitulation” of the Marine Corps’ November 1918 muster rolls for the 4th Brigade, 2d Division, AEF, reveals that 28.9 percent (86 of 212) of the officers and 11 percent (1,040 of 8,372) of the enlisted men in the brigade were Marine Corps reservists.117 In that month, November 1918, the Reserve attained its highest strength: 6,773.118

Certainly the Reserve suffered its share of casualties in a war where the Marine Corps endured more casualties in eight months than during its entire 142 years of existence.119 In February 1919, Barnett reported that 7 Marine Reserve officers and 156 enlisted men were killed in action, and 8 Reserve officers and 61 enlisted men died of other causes. The 6,435 Marines reported wounded were not separated by component, Regular or Reserve, so a definite look at this measure of sacrifice for the Reserve is not possible.120

The deaths reflect the sacrifice and commitment of Marine Corps reservists. The decorations awarded to reservists punctuate the significance of the contributions the Reserve made to the war effort. One Marine reservist, Second Lieutenant Ralph Talbot, earned the Medal of Honor. Forty Marine reservists or Marines enrolled via the Naval Militia or National Naval Volunteers were awarded the Navy Cross with many also earning a Distinguished Service Cross for the same actions.121 Captain Percy D. Cornell, who entered the Marine Corps via the Texas Naval Militia, Marine Branch, was awarded the Navy Cross twice for separate actions.122

Private Roy H. Simpson, who joined the Reserve in Philadelphia assigned to 1st Reserve Company, Marine Barracks Philadelphia,123 was awarded a Navy Cross for heroic actions while serving with the 47th Company, 5th Regiment, during the attack on Belleau Wood. On 12 June 1918, Simpson was carrying a message from battalion headquarters to his company when he was apparently shot. Initially reported as killed in action and posthumously awarded the Navy Cross,124 Simpson was actually a prisoner of war being held at Rastatt, Baden, Germany. He was released on 6 December 1918 and returned to his unit in France on 19 January 1919.125

Several Marine reservists were awarded Navy Distinguished Service medals in addition to the Navy Cross, but only one Marine reservist was recognized solely with the Navy Distinguished Service medal. Second Lieutenant Frank Nelms Jr. earned the medal “for extraordinary heroism as a pilot in the First Marine Aviation Force” during several air raids and for his participation in the airdrop of supplies to an isolated French army unit in October 1918. Nelms flew in at an altitude of 100 feet and dropped food under intense rifle and machine-gun fire, not once, but three times.126 Nelms was commissioned in the Reserve, Class 5, and was among those former U.S. Naval Reserve Force pilots discharged to enter the Reserve to meet the need for pilots in the Day Wing, Northern Bombing Group.127

Two reservists earned the Distinguished Service Cross (DSC): Private Sydney G. Gest and Second Lieutenant Fred Thomas.128 For two separate actions, Thomas earned two DSCs and a Navy Distinguished Service medal. Always in the thick of the action, Thomas also earned four Silver Star citations.129

When war was declared in April 1917, the U.S. Marine Corps had less than 14,000 men in active-duty ranks, with another 1,091 Reserve and National Naval Volunteers available for active duty. By mid November 1918, the Marine Corps had more than 75,000 men and women on active duty, and 7,256 were members of the Reserve. While the Reserve represented not quite 10 percent of the Marine Corps at the end of the war, its growth in approximately 17 months was phenomenal.130

Demobilization

Immediately after the Armistice of 11 November 1918 went into effect, demobilization began. The 1st Marine Aviation Force, which returned to the United States in December 1918,131 disbanded in February 1919, and Marine Flying Field Miami, Florida, closed in September 1919.132 With the end of the war, the number of Reserve aviators quickly dropped. On 9 September 1918, the Reserve Flying Corps had 11 first lieutenants and 118 second lieutenants. A Marine aviator list published 13 March 1919 reflected just 13 first lieutenants and 60-second lieutenants.133 The number continued to drop as men transitioned to inactive status or became members of the regular component.

Marines in the brigades were released on a different basis, with individual requests for release processed as they were received until the new fiscal year began on 1 July 1919. The Naval Appropriations Act approved on 11 July 1919 provided the Marine Corps with funds for an average strength of 27,400 enlisted men plus officers. The pace of demobilization for the brigades then significantly increased. The Marine Corps completed demobilization of the brigades on 13 August. The transfer of reservists on active duty to inactive status was completed on 25 August 1919.134

While the World War I Marine reservists returned to their homes, just as militiamen had done for more than a century, a new and vital source of military capability emerged through the Reserve. Evolutionary changes in American interests, a more international bent, proved the need for a military that could be called upon to do more than “execute the laws of the Union, suppress insurrections, and repel invasions.” The citizen-soldier construct, so important to the founders of the Republic, was maintained. Although an embryonic force in World War I, the Reserve contributions were significant. It was born at just the right time.

The second, and concluding part, of the special feature on the Reserve in World War I focuses on the birth, growth, and contributions of the Reserve Flying Corps and the Reserve (Female).

• 1775 •

Endnotes

- Reserve officers of Public Affairs Unit 4-1, The Marine Corps Reserve: A History (Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office [GPO], 1966), 1.

- U.S. Const. art. I, § 8, cl. 15. U.S. Constitution Online, http://www.usconstitution.net/xconst_A1Sec8.html.

- Uniform Militia Act of 1792, Pub. L. No. 2-1-28, 1 Stat. 264 (1792).

- Rollin F. Van Cantfort, “Call Out the Reserves,” Marine Corps Gazette 37, no. 10 (October 1953): 16.

- U.S. Department of the Navy, Report of the Secretary of the Navy: Being Part of the Message and Documents Communicated to the Two Houses of Congress at the Beginning of the Second Session of the Fifty-Second Congress (Washington, DC: GPO, 1892), 44–46.\

- Van Cantfort, “Call Out the Reserves,” 16.

- New York’s call for volunteers, the very positive response, frustration with the administrative issues, and the exchange of messages between the War Department and New York’s state paymaster-general reflects ever increasing annoyance at the federal and state levels and suggests the absence of clearly defined procedures for bringing a militiaman into federal service. See the Adjutant General’s Office, State of New York, Annual Report of the Adjutant-General of the State of New York for the Year 1898 (Albany, NY: Wynkoop Hallenbeck Crawford Co., 1899), 36–43.

- Adjutant General’s Office, State of New York, Annual Report of the Adjutant-General of the State of New York for the Year 1898 (Albany, NY: Wynkoop Hallenbeck

- Ibid.

- Ibid., 13; and Maj Michael S. Warren, The National Guard in the Spanish-American War and Philippine Insurrection, 1898–1899 (Ft. Leaven- worth, KS: School of Advanced Military, U.S. Army Command and General Staff College, 2012), 12.

- George B. Clark, The United States Military in Latin America: A History of Interventions through 1934 (Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Co., 2014), 117.

- Marine Corps Reserve, 2.

- Ibid.

- U.S. Department of the Navy, Annual Reports of the Navy Department for the Fiscal Year 1911 (Washington, DC: GPO, 1912), 56, 63.

- Col Jon T. Hoffman, USMC: A Complete History (Quantico, VA: Marine Corps Association, 2002), 162–63.

- Marine Corps Reserve, 3.

- 140 Cong. Rec. S (The Naval Militia) (25 January 1994).

- “Records of the Bureau of Naval Personnel: Records of the Division of Naval Militia Affairs,” U.S. National Archives Guide to Federal Records www.archives.gov/research/guide-fed-records/groups/024.html?vm=r#24.6.2.

- Louisiana Adjutant General’s Office, Annual Report of the Adjutant General of the State of Louisiana for the Year Ending 1902 (Baton Rouge, LA: Ramires-Jones Printing Co., 1903), 77–78, filed in The National Guard Memorial Library, Washington, DC.

- Louisiana Adjutant General’s Office, Annual Report of the Adjutant General of the State of Louisiana for the Year Ending 1906 (Baton Rouge, LA: Ramires-Jones Printing Co., 1907),132–33.

- Louisiana Adjutant General’s Office, Annual Report of the Adjutant General of the State of Louisiana for the Year Ending 1912 (Baton Rouge, LA: Ramires-Jones Printing Co., 1913), 26, 72, 104, 134.

- Massachusetts Adjutant General’s Office, Annual Report of the Adjutant General of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts for the Year Ending

- December 31, 1912 (Boston, MA: Wright & Potter Printing Co., 1913), 11.

- Ibid., 33–34.William A. Worton, Personal Papers, Marine Corps Archives and Special Collections, Marine Corps University, Quantico, VA.

- Massachusetts Adjutant General’s Office, Annual Report of the Adjutant General of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts for the Year Ending December 31, 1913 (Boston, MA: Wright & Potter Printing Co., 1914), 24.

- New York Adjutant General’s Office, Annual Report of the Adjutant General of the State of New York for the Year 1916 (Albany, NY: J. B. Lyon Co., 1917), 45, 50, 118, 124. The Department of the Navy issued General Order No. 153 implementing the new federal law, and as the states complied with the directive, the composition of their naval brigades adhered to a three-battalion organizational construct. Secretary of the U.S. Navy, U.S. Department of the Navy, General Orders of the Navy Department: Series of 1913 (Washington, DC: GPO, 1918).

- U.S. Department of the Navy, Register of the Commissioned and Warrant Officers of the Naval Militia of the United States (Washington, DC: GPO, 1914).

- Ibid., 28.

- Of note, when war was declared, Power left the naval militia and joined the New York National Guard (NG) in May 1917 and was assigned to the 102d Sanitation Train, 27th Division, NG. He deployed for World War I in June 1918 and returned to Brooklyn, New York, in March 1919 to be discharged. New York State Adjutant General’s Office, Abstracts of National Guard Service in World War I, 1917–1919, Series 13721, New York State Archives, http://nysa32.nysed.gov/a/digital/images/about/about_military_wwi.shtml.

- Charles H. Power to Capt F. B. Bassett, USN, letter, 25 January 1915, Reserve subject file, Historical Inquiries and Research Branch (HIRB), Ma- rine Corps History Division, Quantico, VA.

- Capt Bassett forwarding Power’s letter to MajGen Commandant George Barnett, Reserve subject file, HIRB, Marine Corps History Division,Quantico, VA.

- Letter from MajGen George Barnett, 3 February 1915, Reserve subject file, HIRB, Marine Corps History Division, Quantico, VA.

- Ibid.

- War College Division, General Staff Corps, The Militia as Organized Under the Constitution and Its Value to the Nation as a Military Asset, War Department Document No. 516 (Washington, DC: GPO, 1916), 19.

- Naval Militia Act of 1914, Pub. L. No. 63-57, 38 Stat. 283.

- Division of Naval Militia Affairs, Navy Department, Naval Militia Annual Report for the Year 1914 (Washington, DC: GPO, 1915), 3, 4, 72.

- LtCol Merrill L. Bartlett, “George Barnett,” in Commandants of the Marine Corps, ed. Allan R. Millett and Jack Shulimson (Annapolis, MD: U.S. Naval Institute Press, 2004), 176.

- Marine Corps Reserve, 4.

- Bartlett, “George Barnett,” 181–82.

- General Orders of Navy Department.

- Ibid.

- Ibid., 3, 4, 9..

- Ibid., 2.

- Navy Department, Annual Reports of the Navy Department for the Fiscal Year 1915 (Washington, DC: GPO, 1916) 761.

- The billet title “Assistant Commandant of the Marine Corps” was first used in October 1946, but in reading Gen Lejeune’s memoir, Lejeune’s duties as Assistant to the Commandant were similar to those of the Assistant Commandant of the Marine Corps. “Marine Corps Assistant Commandants,” HIRB, Marine Corps History Division, www.mcu.usmc.mil/historydivision/pages/frequently_requested/Assistant_Commandant.aspx.

- MajGen John A. Lejeune, The Reminiscences of a Marine (Philadelphia: Dorrance and Company, 1930), 219, 227.

- Hearings Before the Committee on Naval Affairs, House of Representatives, 64th Cong. (29 February 1916) (statement of USMC MajGen Commandant George Barnett), 2143.

- U.S. Congress and Secretary of State, The Statutes at Large of the United States of America from December, 1915, to March, 1917: Concurrent Resolutions of the Two Houses of Congress and Recent Treaties, Conventions, and Executive Proclamations, vol. 39, part 1 (Washington, DC: GPO, 1917), 593.

- Ibid., 595.

- General Orders of the Navy Department.

- Headquarters U.S. Marine Corps, Revision of U.S. Marine Corps Orders, May, 1918 (Washington, DC: GPO, 1918), hereafter Revision of U.S. Marine Corps Orders, 104–20. Among other Marine Corps orders, the reference contains Marine Corps Order No. 13 (series 1917).

- Maj Edwin N. McClellan, The United States Marine Corps in the World War (Washington, DC: Historical Branch, G-3 Division, Headquarters Marine Corps, 1968), 71.

- S. Doc. No. 7983, at 452 (1918).

- Commandant of the Marine Corps, U.S. Marine Corps General Order No. 34, 10 July 1918, Reserve subject file, HIRB, Marine Corps History Division, Quantico, VA.

- MajGen Barnett letter to chief of the Division of Naval Militia Affairs, Bureau of Navigation, Department of the Navy, 11 July 1918, Reserve sub- ject file, HIRB, Marine Corps History Division, Quantico, VA. In spite of the legislation and Barnett’s order, some Marines continued to be listed as National Naval Volunteers on unit muster rolls through World War I and during demobilization.

- McClellan, United States Marine Corps in the World War, 11, 76.

- Philadelphia War History Committee, Philadelphia in the World War, 1914–1919 (New York: Wynkoop, Hollenbeck, Crawford Co., 1922), 81.

- David J. Bettez, Kentucky Marine: Major General Logan Feland and the Making of the Modern USMC (Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 2014), 76–77.

- Ibid., 78.

- U.S. Department of the Navy, Register of the Commissioned and Warrant Officers of the United States Navy, U.S. Naval Reserve Force and the Marine Corps, January 1, 1919 (Washington, DC: GPO, 1919), 870.

- Robert B. Asprey, “The King of Kill,” Marine Corps Gazette 51, no. 5 (May 1967): 33.

- The current Marine Corps Recruit Depot Parris Island was Marine Barracks, Paris Island, SC, in 1917. The spelling changed to Parris Island in May 1919. Revision of U.S. Marine Corps Orders, MCO No. 27 (Series 1917), 129; and Elmore A. Champie, Brief History of Marine Corps Recruit Depot, Parris Island, South Carolina (Washington, DC: Historical Branch, G-3 Division, Headquarters, U.S. Marine Corps, 1962), 4.

- Asprey, “The King of Kill,” 33.

- “Anthony J. Drexel Biddle,” in “Headquarters Detachment, Officers Training Camp, Marine Barracks Quantico, VA, muster roll (MRoll), April–December 1918,” “Barracks Detachment, Marine Barracks Philadelphia Navy Yard, PA, MRoll, January 1919,” and “Third Reserve District MRoll, July 1919,” HIRB, Marine Corps History Division, Quantico, VA.

- David J. Bettez, “The Marine Corps Prepares for War: The Philadelphia Military Training Camp,” Leatherneck 92, no.10 (October 2009), 51.

- McClellan, United States Marine Corps in the World War, 76.

- U.S. Department of the Navy, Annual Reports of the Navy Department for the Fiscal Year 1917 (Washington, DC: GPO, 1918), 25.

- “United States Reserve, 1914–1940,” a summary paper, Reserve subject file, HIRB, Marine Corps History Division, Quantico, VA.

- “Marine Corps Militia,” Marine Magazine, July 1917, 4.

- Revision of U.S. Marine Corps Orders, 125.

- Department of the Navy, Register of the Naval Militia of the States, Territories, and of the District of Columbia, January 1, 1917 (Washington, DC: GPO, 1917), 228, and “National Naval Volunteers (MC), 36th Company, Marine Barracks Mare Island, CA MRoll, 6 April-30 April 1917,” and “98th Company, Marine Barracks Mare Island MRoll, 1 September-30 September 1917,” HIRB, Marine Corps History Division.

- “Louisiana Company, National Naval Volunteers (MOB) MRoll, 6 April-30 April 1917,” HIRB, Marine Corps History Division.

- LtCol Eben Putnam, A. of U.S., ed., Report of the Commission on Massachusetts’ Part in the World War: History, vol.1 (Boston, MA: The Commonwealth of Massachusetts, 1931), 28; and “1st Marine Company (Mass.), National Naval Volunteers MRoll, 7 April-30 April 1917,” HIRB, Marine Corps History Division.

- Ibid., 155-56; and James R. Walsh, Officers’ Data Card, Archives-Museum Branch, The Adjutant General’s Office, Concord, MA.

- “New York Company, National Naval Volunteers MRoll, 6 April-11 April 1917,” HIRB, Marine Corps History Division.

- “Eastern Recruiting Division MRoll, 1November-30 November, 1917,” HIRB, Marine Corps History Division, Quantico, VA; and New York Adjutant General, Annual Report of the Adjutant General of The State of New York, 1917 (Albany, NY: J.B. Lyon Co., 1920), 20.

- “1st Marine Company, 3d Battalion, National Naval Volunteers, Tonawanda, NY MRoll, 7 April-7 May 1917,” HIRB, Marine Corps History Division.

- “2d Marine Company, 3d Battalion, National Naval Volunteers, Rochester, NY MRoll, 6 April-6 May 1917,” HIRB, Marine Corps History Division.

- “Ohio Company, National Naval Volunteers, Marine Barracks New York MRoll, 7 April-30 April 1917,” HIRB, Marine Corps History Division.

- Oregon Secretary of State, Oregon Blue Book, 1917-1918, compiled by Ben W. Olcott, Secretary of State (Salem, OR: State Printing Department, 1918), 114; and “Marine Corps Militia,” Marine Magazine, July, 1917, 4.

- “Company A, Texas National Naval Volunteers MRoll, 12 April-30 April 1917,” HIRB, Marine Corps History Division.

- “Company B, Texas National Naval Volunteers MRolls 7 April-30 April 1917 and 1May-4 May 1917,” HIRB, Marine Corps History Division.

- “Company C, Texas National Naval Volunteers MRoll 6 April-30 April 1917,” HIRB, Marine Corps History Division.

- “Company D, Texas Naval Militia (Marine Corps Branch) MRoll 6 April-30 April 1917,” HIRB, Marine Corps History Division.

- “1st Marine Company, (R.I.), National Naval Volunteers MRoll 7 April-30 April 1917,” HIRB, Marine Corps History Division.

- “Marine Company, National Naval Volunteers, 1st Regiment, Marine Barracks Navy Yard Philadelphia MRoll 9 April-30 April 1917,” HIRB, Marine Corps History Division.

- McClellan, United States Marine Corps in the World War, 25.

- Bernard C. Nalty and LtCol Ralph F. Moody, A Brief History of U.S. Marine Corps Officer Procurement, 1775–1969 (Washington, DC: Historical Division, HQMC, 1958, rev. ed. 1970), 4..

- McClellan, United States Marine Corps in the World War, 22.

- LtCol Charles A. Fleming, Capt Robin L. Austin, and Capt Charles A. Braley III, Quantico: Crossroads of the Marine Corps (Washington, DC: History and Museums Division, HQMC, 1978), 26.

- Revision of U.S. Marine Corps Orders, 128; and Nalty and Moody, A Brief History of U.S. Marine Corps Officer Procurement, 76.

- McClellan, United States Marine Corps in the World War, 9, 11.

- Col Robert Debs Heinl Jr., Soldiers of the Sea: The United States Marine Corps, 1775–1962 (Annapolis: U.S. Naval Institute, 1962), 193.

- George B. Clark, Devil Dogs: Fighting Marines of World War I (Novato, CA: Presidio Press, Inc., 1999), 2–3.

- Ibid., 2.

- McClellan, United States Marine Corps in the World War, 9.

- Clark, Devil Dogs, 2.

- “Supply Company, 5th Regiment, onboard USS Hancock, MRoll, 12 June–30 June 1917,” HIRB, Marine Corps History Division, Quantico, VA.

- “5th Regiment Field and Staff MRoll, 8 June–30 June 1917” and the muster rolls of “Headquarters Company, 5th Regiment; Supply Company, 5th Regiment” and the companies of “1st Battalion, 5th Regiment, 2d Battalion, 5th Regiment and 3d Battalion, 5th Regiment, June 1917,” HIRB, Marine Corps History Division, Quantico, VA.

- "2d Division General Recapitulation MRoll, 1 November–30 November 1918,” HIRB, Marine Corps History Division, Quantico, VA.

- James S. Santelli, A Brief History of the 7th Marines (Washington, DC: History and Museums Division, HQMC, 1980), 1.

- J. Robert Moskin, The U.S. Marine Corps Story, 3d rev. ed. (Boston, MA: Little, Brown and Company, 1992), 156; and “Headquarters, 7th Marine Regiment MRoll, 14 August–31 August 1917,” HIRB, Marine Corps History Division, Quantico, VA.

- James S. Santelli, A Brief History of the 8th Marines (Washington, DC: History and Museums Division, HQMC, 1976), 1–2.

- “Headquarters, 7th Marine Regiment MRoll, 14 August–31 August 1917,” HIRB, Marine Corps History Division.

- “37th, 59th, 71st, 72d, 86th, 90th, 93d, and 94th Companies, 7th Marine Regiment, USMC, MRoll, 1–31 August 1917,” HIRB, Marine Corps History Division, Quantico, VA.

- Communiqué from the German foreign secretary, Arthur Zimmermann, to the German ambassador to Mexico that promised significant financial support to Mexico if it allied with Germany against the United States. BGen Edwin Howard Simmons and Col Joseph H. Alexander, Through the Wheat: The U.S. Marines in World War I (Annapolis: U.S. Naval Institute Press, 2008), 2.

- Santelli, A Brief History of the 8th Marines, 1.

- “Headquarters Company, 8th Marine Regiment MRoll, 9–31 October 1917,” HIRB, Marine Corps History Division, Quantico, VA.

- “103d, 104th, 105th, 106th, 107th, 108th, 109th, 110th, 111th, and 112th Companies, 8th Marine Regiment, USMC MRoll, 1–31 October 1917,” HIRB, Marine Corps History Division, Quantico, VA.

- “Headquarters Company, 8th Marine Regiment MRoll, 1–30 November 1917,” HIRB, Marine Corps History Division, Quantico, VA.

- Santelli, A Brief History of the 8th Marines, 2.

- Truman R. Strobridge, A Brief History of the 9th Marines (Washington, DC: Historical Branch, G-3 Division, HQMC, 1967), 1.

- “Headquarters, 9th Marine Regiment MRoll, 20 November–30 November 1917,” HIRB, Marine Corps History Division.

- “36th Company, 9th Marine Regiment MRoll, 20 November–30 November 1917, HIRB, Marine Corps History Division.

- “100th Company, 9th Marine Regiment MRoll, 1 November–30 November 1917,” HIRB, Marine Corps History Division.

- “121st, 122d, 123d, 124th, 125th, and 126th Companies, 9th Marine Regiment MRoll, 1 November– 30 November 1917,” HIRB, Marine Corps History Division.

- “2d Division General Recapitulation MRoll, 1 November–30 November 1918,” HIRB, Marine Corps History Division.

- McClellan, United States Marine Corps in the World War, 76.

- Heinl, Soldiers of the Sea, 219.

- The Marine Corps Reserve, 10.