PRINTER FRIENDLY PDF

EPUB

AUDIOBOOK

Abstract: The Marine Corps is poised to vastly expand its presence in Guam. Under a 2012 bilateral agreement with Japan, the United States is preparing to transfer approximately 5,000 in Marine Corps force strength from Okinawa to Guam. The relationship between Guam and the Corps has endured since 1898, when the Marine Corps played a supporting, yet significant, role in the United States’ acquisition of Guam. By early 1899, the United States had finally established effective control over Guam, which would continue until a Japanese invasion force seized the island on 10 December 1941.

Keywords: Guam, USS Charleston, Spanish-American War, Lieutenant John T. Myers, Fort Santa Cruz, San Luis d’Apra, USS Bennington, Treaty of Paris

The U.S. Marine Corps is poised to vastly expand its presence in Guam. Under a 2012 bilateral agreement with Japan, the United States is preparing to transfer approximately 5,000 in Marine Corps force strength from Okinawa to Guam.1 That process began with the October 2020 administrative activation of Camp Blaz at Dededo in northwest Guam.2 The first newly established Marine Corps base since 1952, Camp Blaz is the site of more than $1 billion in construction projects during fiscal year 2024.3 The installation’s website explains that the “base is named in honor of Brigadier General Vicente Tomas ‘Ben’ Garrido Blaz, the first [Chamorro] Marine to attain the rank of general officer and honors the Blaz family and the significant relationship between the island of Guam and the U.S. Marine Corps, which has endured since before the campaigns of World War II.”4 That relationship began in 1898, when the Marine Corps played a supporting, yet significant, role in the United States’ acquisition of Guam.

Launched a decade before the Spanish-American War, USS Charleston (C 2) was a 320-foot protected cruiser with a top speed of 18.7 knots.5 It was armed with two pivoting 8-inch breach-loading rifles capable of firing 250-pound projectiles, six 6-inch breach-loading rifles, and 12 secondary guns.6 When Charleston set sail from San Francisco in May 1898, most of the crew members were raw recruits making their first voyage.7 Of the 233 sailors recorded on the ship’s 5 May 1898 muster roll, 161 enlisted after an explosion sank USS Maine (second-class battleship) in Havana’s harbor 79 days earlier.8 Joining them were three embedded reporters who generated a trove of contemporary narratives of Charleston’s voyage.9

USS Charleston (C 2) was escorting troop transports from Hawaii to the Philippines when it was diverted to take possession of Guam. Little more than 16 months after Guam’s capture, Charleston sank after striking an uncharted coral reef off Luzon’s northern coast. Naval History and Heritage Command, catalog no. NH 88407

Also on board Charleston was a guard consisting of 30 enlisted Marines under the command of Second Lieutenant John T. Myers. The detachment included 1 first sergeant, 2 sergeants, 3 corporals, 2 fifers, and 22 privates. The Marines were somewhat more seasoned than their Navy counterparts. Only two had joined the Marine Corps after Maine’s sinking.10

2dLt John Twiggs Myers in 1897, the year before he participated in the capture of Guam. John Twiggs Myers Personal Papers (Coll/3016), Archives Branch, Marine Corps History Division

Myers’s path to a Marine Corps commission was unusually circuitous. His father was Abraham Myers, an 1833 West Point graduate for whom Fort Myers, Florida, was named when it was an actual fort.11 Abraham Myers served as the Confederate Army’s quartermaster general until President Jefferson Davis removed him in August 1863. Explanations vary.12 After the Civil War, Myers exiled himself to Wiesbaden, Germany, where his son John was born in 1871.13 The Myers family returned to the United States in 1876.14

Sixteen-year-old Myers was appointed to the Naval Academy from Georgia’s Ninth Congressional District, enrolling in autumn 1887 as part of the class of 1891.15 However, he spent so much time on the sick list during his second year that he was turned back to the next class.16 Nevertheless, he persevered. In June 1892, Myers was 1 of 40 naval cadets (as midshipmen were then known) to receive a diploma from Secretary of the Navy Benjamin F. Tracy.17 Two years later, at the conclusion of his follow-on cruise on board the protected cruiser USS Boston (1884) and final examination, his class standing was 29th of 31 in the line division—too low to obtain a commission.18 After being honorably discharged, Myers was rescued by an 1894 law allowing Naval Academy graduates who did not receive a commission to become Navy assistant engineers.19 The Senate confirmed Myers’s nomination in August 1894.20 He did not remain an assistant engineer long. Worried that he did “not know high pressure from low pressure” and fearing assignment to engineer duty on a warship, Myers arranged a transfer.21 Learning that his Naval Academy classmate Second Lieutenant Walter Ball was unhappy as a Marine Corps officer, Myers proposed that they swap career fields. Both Ball and the Navy Department agreed.22 The Senate formally approved the transfers on 25 February 1895.23

Training consumed much of Myers’s early Marine Corps service. In spring and summer 1895, he received his initial indoctrination as a Marine Corps officer at the School of Application at Marine Barracks Washington, DC, a precursor to The Basic School. In May 1896, he studied ordnance at the Washington Navy Yard. That summer, he attended the Naval War College in Newport, Rhode Island. Following a month-long assignment at Marine Barracks Boston, Myers was transferred across the country to Marine Barracks Mare Island, California. After almost 18 months there, on 9 May 1898, he reported to USS Charleston as commanding officer of the ship’s Marine guard.24 The cruiser was then moored at the Mare Island Naval Yard.25 While assigned to Charleston, Myers wore a stylish pointed beard topped by a handlebar mustache (see figure on p. 9). The 27-year-old Marine officer was a newlywed. Less than a month before Charleston left San Francisco, he married Alice Cutts, a great-granddaughter of Francis Scott Key.26

To great fanfare, USS Charleston cast off and headed toward sea at 1022 on 18 May 1898.27 It was a false start. At 0450 the next morning, the cruiser returned to the Mare Island Naval Yard for repairs.28 While engineers plugged leaks in Charleston’s condenser tubes, Secretary of the Navy John D. Long sent a telegram to Rear Admiral George Dewey, commander of the Asiatic Squadron, on 20 May: “[USS City of ] Pekin [1898, steamer] and Charleston proceed at once to Manila, touching at Guam, Ladrone Islands, where will capture fort, Spanish officials, and garrison and act at discretion regarding coal that may be found.”29 In fact, the Navy Department had already issued an order dated 10 May 1898 to be delivered to Captain Glass in Honolulu providing more detailed directions for his operations “at the Spanish Island of Guam.”30 Yet, Charleston’s captain, officers, and crew apparently remained unaware of that mission when they restarted their westward voyage on the morning of 21 May. At 1115, as recorded in the logbook, Charleston “stood down Mare Island Strait, the Captain and Navigator on the bridge.”31 After a slow start in foggy conditions that delayed making necessary adjustments to the ship’s compasses, Charleston passed through the Golden Gate on the morning of 22 May.32 Troops from the Presidio awaiting transportation to the Philippines cheered from the shore.33 A member of the signal corps used a flag to send a message to the departing vessel by wigwag: “Be sure to remember the Maine.” The warship signaled back, “Good bye. Don’t fear, we will remember.”34

2dLt Myers strides in front of the Marine guard aboard USS Charleston. Photo by Douglas White, Naval History and Heritage Command, catalog no. WHI.2014.48

A week after departing Mare Island, Charleston arrived in Honolulu, the capital of what was then the independent Republic of Hawaii.35 There the cruiser rendezvoused with three troop transports: City of Pekin, SS Australia, and SS City of Sydney.36 Embarked on those vessels were the 1st California Volunteer Infantry Regiment, 2d Oregon Volunteer Infantry Regiment, five companies of the 14th United States Infantry, and a detachment of the 1st California Field Artillery. Those units’ combined strength was 115 officers and 2,386 enlisted soldiers.37 The Army component was under the command of Brigadier General Thomas McArthur Anderson, a Civil War veteran who was a nephew of Major Robert Anderson, the commander of Fort Sumter at that war’s outset.38 City of Pekin, a merchant vessel the Navy rented for $1,000 per day, also carried Marines who would be assigned to ships in the Asiatic Squadron.39 Charleston’s mission was to escort the three lumbering transports from Hawaii to Manila Bay, where the convoy’s passengers would augment a U.S. force assembling to capture the Philippines’ capital from its Spanish defenders. While in Honolulu, Charleston’s crew and the transports’ Manila-bound soldiers were feted at a giant luau on Iolani Palace’s grounds.40 Five of Charleston’s Marines enjoyed Honolulu too much. Three privates, a corporal, and a sergeant had their liberty status downgraded for returning late by one to three hours. Fifty-eight sailors were also punished for returning to Charleston late, drunk, or both.41

Charleston’s captain was Henry Glass. He finished first in what was supposed to be the Naval Academy’s class of 1864; the class’s graduation was accelerated by a year to supply the fleet with sorely needed junior officers.42 Assigned to the South Atlantic Blockading Squadron, Glass saw considerable action during the Civil War.43 His career survived a censure from the secretary of the Navy for grounding USS Cincinnati (C 7) on Long Island Sound’s Execution Rock in 1894, the same year he had been promoted to captain.44 He took command of Charleston when the cruiser was recommissioned on 5 May 1898, 10 days after the United States declared war against Spain.45 A future chief of naval operations who served under Glass on board Charleston described him as “a hard driver.”46

While in Honolulu, Glass received sealed orders he was not to open until underway.47 Once at sea, Charleston’s captain read this directive from Secretary Long:

Sir: Upon the receipt of this order, which is forwarded by the steamship City of Pekin to you at Honolulu, you will proceed, with the Charleston and City of Pekin in company, to Manila, Philippine Islands.

On your way, you are directed to stop at the Spanish Island of Guam. You will use such force as may be necessary to capture the port of Guam, making prisoners of the governor and other officials and any armed force that may be there. You will also destroy any fortifications on said island and any Spanish naval vessels that may be there, or in the immediate vicinity. These operations at the Island of Guam should be very brief, and should not occupy more than one or two days. Should you find any coal at the Island of Guam, you will make such use of it as you consider desirable. It is left to your discretion whether or not you destroy it.

From the Island of Guam, proceed to Manila and report to Rear-Admiral George Dewey, U. S. N., for duty in the squadron under his command.48

Capt Henry Glass on the deck of USS Charleston. A future Chief of Naval Operations who served under Glass on board Charleston characterized him as “a hard driver.” Photo by Douglas White, Naval History and Heritage Command, catalog no. WHI.2014.42

Secretary Long’s order to Glass, as well as follow-on communications with Rear Admiral Dewey, suggests that the Navy Department’s primary goal for Charleston’s mission was to acquire a port facility between Honolulu and the Philippines.49 In executing his orders, however, Captain Glass would exceed that limited objective.

At 0900 on 5 June, the day after leaving Hawaii, Captain Glass mustered his officers on the quarterdeck and informed them of the convoy’s revised mission.50 Wigwag messages soon passed the news to the troop transports.51 It would take the four vessels 15 more days to sail the roughly 3,300 nautical miles to Guam.

Nine days into the voyage, City of Pekin steamed ahead of Charleston and dropped boxes into the ocean.52 Charleston’s gun crews were soon engaged in target practice, aiming at the bobbing crates. At least one of Charleston’s four 6-pounder rapid-fire guns was manned by Marines (see figure, p. 12). During the late nineteenth century, the Marine Corps was in danger of being disestablished.53 To increase Marines’ usefulness, Colonel Commandant Charles Heywood launched a campaign for Marine guard detachments to man their ships’ rapid-fire and secondary batteries.54 Charleston’s Marines working as a gun crew exemplified that self-preservation strategy in action.

More target practice followed on 15 June.55 Two days later, the convoy stopped to allow Charleston’s captain’s gig to transport Glass to Australia. There, he, Brigadier General Anderson, and the three transports’ captains held a council of war. While Glass was on board Australia, he was treated to the spectacle of Charleston’s main battery firing with remarkable precision at a white canvas pyramid target rising six feet above the waterline a kilometer away.56

Marines manned at least one of USS Charleston’s four 6-pounder rapid-fire guns. The Marines were not called on to fire during the conquest of Guam. Photo by Douglas White, Naval History and Heritage Command, catalog no. WHI.2014.49

Throughout 18 June, Charleston’s crew gradually cleared the ship for action.57 An Associated Press reporter embedded on the vessel observed that “by nightfall the boats had been wrapped in canvas, all the portable wood and iron work stowed below, the splinter netting spread above the main deck, and the Charleston was ready for any emergency.”58

On Sunday, 19 June, less than a day’s sail from Guam, the convoy stopped again. Australia’s third officer, Thomas A. Hallett, who had previously visited Guam as captain of a whaler, transferred onto Charleston to act as the ship’s pilot.59 Father William D. McKinnon, the 1st California Volunteers’ Roman Catholic chaplain, reported on board Charleston from City of Pekin in anticipation of battle the next day.60 Charleston’s logbook records that at 1850 that evening, “rang church bell, and held Divine Service on board. Father McKinnon officiating.”61 McKinnon heard confessions until 0130 that night. Several days later, he wrote that “[b]efore the expected engagement, I gave a general absolution. It was quite a solemn sight as all (even non-Catholics) seemed very much in earnest.”62

At 0450 on 20 June, just as dawn broke, Guam’s northern tip was sighted off Charleston’s port bow.63 Fifteen minutes later, City of Pekin fired a rocket and flashed a blue light, signaling that its crew had also sighted land.64 Charleston went to general quarters at 0530.65 Half an hour later, its crewmembers ate breakfast before returning to their battle stations, the ship’s guns already shotted in preparation.66

The original plan called for Charleston to hoist a Japanese flag while approaching Guam.67 But that ruse was ultimately rejected, and the American warship made the run flying the Stars and Stripes.68 After steaming halfway down the island’s west coast, the convoy approached Agaña Bay at 0730.69 The transports fell back as Charleston sailed close to shore, looking for a Spanish gunboat believed to be in the vicinity. After the cruiser’s lookout reported “nothing there,” the convoy proceeded approximately 10 kilometers south to the harbor of San Luis d’Apra.70 Third Officer Hallett was perched on the warship’s forward fighting top, allowing him to better see transitions in the water color that signified changes in the bottom’s depth or the presence of dangerous coral reefs.71

As Charleston entered the mist-enshrouded harbor, an anchored vessel came into view.72 Someone on Charleston’s bridge exclaimed, “By George, it’s a gunboat!”73 The resulting excitement dissipated when the vessel hoisted a white pennant adorned with a red circle, signifying it was a Japanese merchantman.74 Spanish fortifications then renewed the tension on Charleston’s bridge. The ship’s charts showed a fort atop a cliff on the starboard side.75 In a letter to his brother, Myers recalled the “ticklish moment when we got under the fort and found we could not train our guns on it, as it was too high.”76 Fortunately for the vulnerable Americans, the clifftop citadel was long-abandoned.77 As Charleston sailed past that fort, another loomed ahead.78 Constructed in 1808, Fort Santa Cruz was, as described by Charleston’s assistant surgeon, “a small, square, stone, box-like affair built on a low coral reef in about the center of the harbor.”79 Charleston dropped its speed to 4 knots in the twisting channel, a coral reef off the port side and high bluffs to starboard.80 After signaling the transport ships to remain outside the harbor, Captain Glass had his forward 3-pound gun crews lob a dozen shells toward the fort.81 Following a 10-minute wait with no reply, Charleston dropped its port anchor.82

A map of Guam from 1902. The 48-kilometer-long island has a total area of 550 square kilometers. USS Charleston arrived from the northwest before steaming down the island’s west coast, first entering Agaña Bay and then Apra’s harbor 10 kilometers to the south. Map by U.S. Coast and Geodetic Survey, Library of Congress Geography and Map Division

A map of Port San Luis d’Apra from 1902. The channel into Apra’s harbor brought Charleston close to Fort Santiago, situated atop a cliff near Orote Peninsula’s point. Fortunately for the Americans, the island’s Spanish garrison had abandoned the fort. After sailing past Fort Santiago, Charleston faced Fort Santa Cruz, a low-lying structure built on a reef in the middle of the harbor. Map by U.S. Coast and Geodetic Survey, Library of Congress Geography and Map Division

A pair of boats soon rowed out to the cruiser, one flying a Spanish flag.83 Two Spanish officers and an interpreter boarded the warship and were escorted to Captain Glass’s cabin. History offers conflicting accounts of what occurred there. According to one version, Lieutenant Francisco García Gutiérrez of the Spanish Navy apologized for failing to return Charleston’s salute. He explained that the port had no guns but promised to return the salute as soon as possible. Captain Glass was puzzled for a moment before realizing his visitors mistook Charleston’s shelling of Fort Santa Cruz for a salute to the Spanish flag. The United States had declared war against Spain almost two months earlier, and 50 days had passed since Commodore George Dewey’s squadron sank the Spanish fleet in Manila Bay. Yet, the Spanish forces stationed at Guam had no idea their country was at war with the United States. Captain Glass informed his astounded guests that they were prisoners of war. He directed them to go ashore, proceed to the Mariana Islands’ capital of Agaña (now Hagåtña), and summon the governor, Lieutenant Colonel Juan Marina Vega (more commonly known as Juan Marina), to the ship.84

Douglas White, a San Francisco Examiner correspondent embarked on board Charleston, disputed that the Spanish officers believed the shelling was a salute. Describing himself as an eyewitness to the events in Captain Glass’s cabin, White insisted that when the two Spanish officers arrived on board Charleston, “there was absolutely no apology on account of their supposing that the shots which had been fired at Fort Santa Cruz were in the nature of a salute.”85 White explained that “the only mention of the word ‘salute’ came from Lieutenant-Commander Gutierrez, who said: ‘Why, Captain, we are without defenses at this port, as all of our forts have been dismantled. If it were only that you were entitled to a salute from us, we could not have fired it except from Agaña, as we have not even a field-piece on this bay’.”86 White concluded:

These Spaniards knew that the Charleston had “swatted” their ancient fort with solid shot, and they never for a moment considered these shots a salute. They never attempted to define it as such; and one or two of the chroniclers who have given out the salute theory as part of their versions of the capture of Guam were at least well enough informed to have made no such mistakes.87

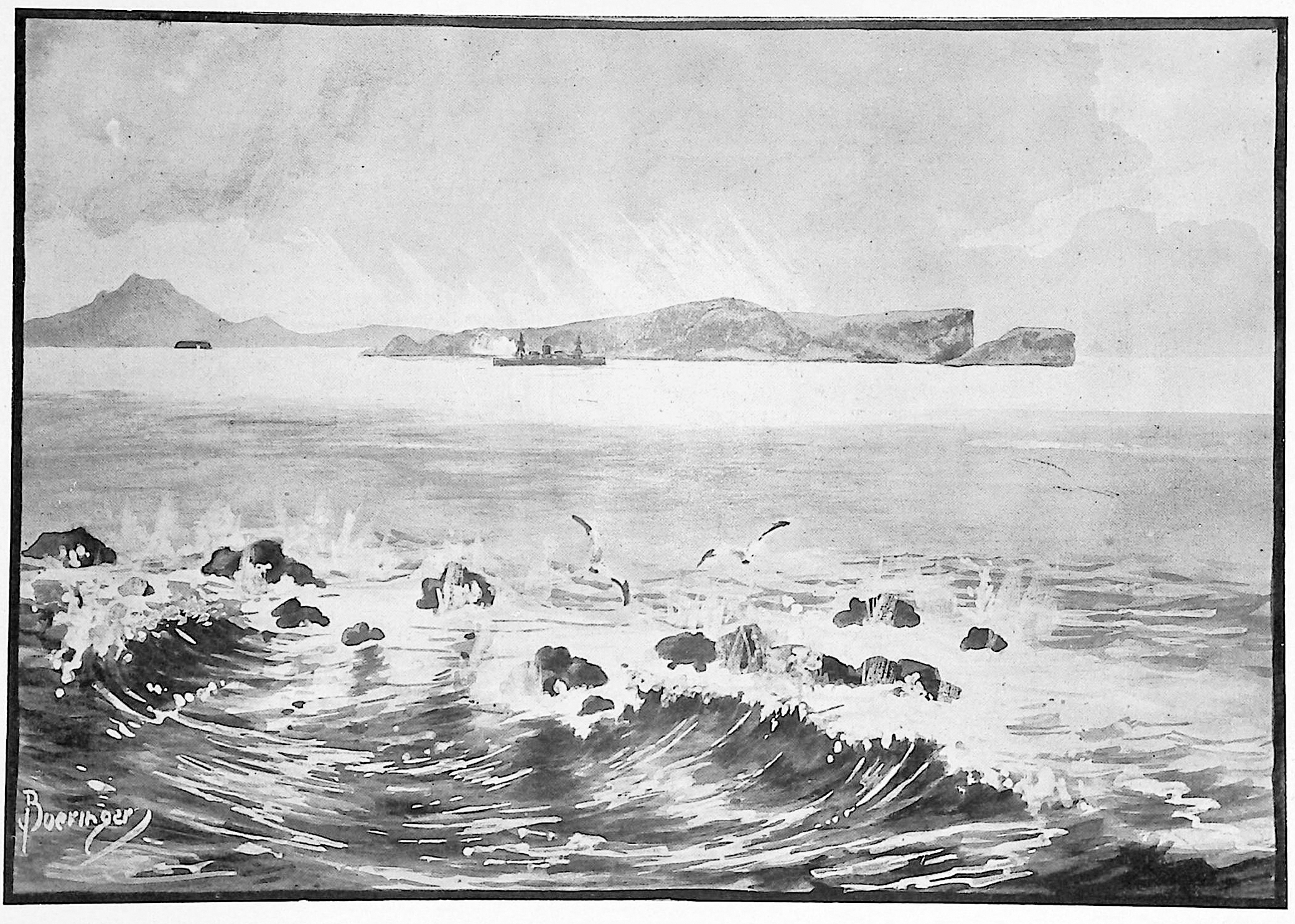

Pierre N. Boeringer, an artist for the San Francisco Call who was on the transport Australia when Charleston shelled Fort Santa Cruz, drew this illustration of the incident. Drawing by Pierre N. Boeringer, as reproduced in Douglas White, On to Manila (1899)

Perhaps one of the journalists White had in mind was Sol Sheridan of the San Francisco Call. White noted that, like himself, Sheridan witnessed the day’s events.88 In a dispatch dated 22 June on board Charleston in San Luis d’Apra’s harbor, Sheridan reported, “It was 10:30 when the Spanish officials came on board, ignorant of the fact that war was waging between Spain and the United States and profuse in their apologies that, their saluting battery being at Agana, they had been unable to return the Charleston’s salute.”89

Years later, Myers and another U.S. officer involved in the incident endorsed the account that the Spanish officers believed Charleston’s barrage of Fort Santa Cruz was a salute.90 Another witness who corroborated that interpretation was Frank Portusach, a naturalized American citizen then living in Guam.91 Portusach recounted that when Charleston shelled Fort Santa Cruz, a Spanish officer on shore thought the ship was firing a salute, resulting in a message being dispatched to Agaña to send artillery to return the salute.92

An account by Lieutenant García definitively resolves the historical dispute. In this instance, the more colorful account is correct. Four months after the events, Lieutenant García wrote to a Spanish official that on 20 June, a squadron of four large American ships arrived at the San Luis d’Apra port’s entrance.93 One of the ships, a cruiser, entered the harbor flying a “beautiful Spanish flag” from its stern as it fired its guns.94 Lieutenant García explained to his Spanish superiors that the “great distance from which the ship was firing, which did not allow the shots to be heard, and the fact that the Spanish flag was hoisted, led the officer who has the honor of subscribing to be certain that the foreign ship was saluting the Spanish flag.”95 When recounting the meeting in Captain Glass’s cabin, Lieutenant García noted that he expressed his “surprise at the firing, which from the shore appeared to be entirely a salute to the flag.”96 Glass replied that “the firing had been intended to find out whether or not the squadron would be harassed.”97 White was mistaken when he declared that the Spanish officers “never for a moment considered these shots a salute.” His haughty rebuke of “one or two” well-informed journalists for publishing accounts of the Spaniards’ mistaken interpretation of the shelling of Fort Santa Cruz did his colleagues an injustice.

At 1700 on the day of Charleston’s arrival at Guam, Captain Pedro Duarte—a Spanish Army officer who served as Governor Marina’s secretary—accompanied by the governor’s interpreter arrived on board the warship.98 They delivered a communiqué from Marina stating that Spanish law prohibited him from boarding a foreign vessel but offering to host Captain Glass ashore. The missive concluded with a promise: “I guarantee your safe return to your ship.”99 Both amused and chagrined by the response, Glass directed the Spaniards to tell Governor Marina that he would dispatch an officer with a message for the governor early the next morning.100

That evening, Captain Glass met with General Anderson aboard the troop transport Australia. Fearing that Governor Marina’s invitation to meet ashore might be part of some ruse de guerre, they agreed that the American landing party would be augmented by Charleston’s Marine guard, 2 companies of the 2d Oregon Volunteer Infantry Regiment, and 10 of the Marines aboard City of Pekin.101 As another security measure, a boarding party from Charleston inspected the Japanese merchant vessel, which turned out to be harmless.102 With Charleston’s officers and crew no doubt remembering Maine’s explosion in Havana’s harbor, the ship’s guard was doubled that night as its searchlights skimmed across the water.103

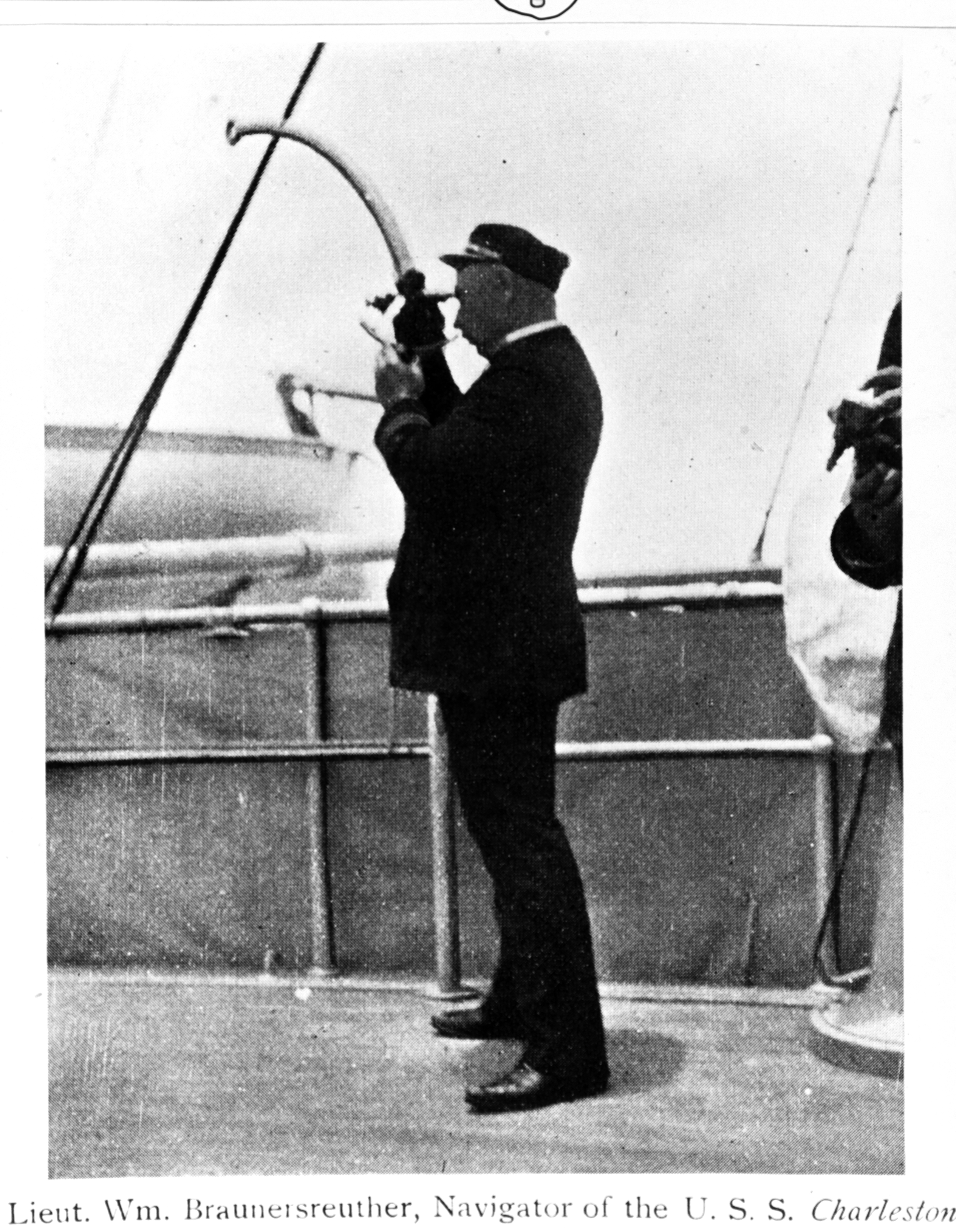

The officer Captain Glass sent to meet with Governor Marina the next morning was Lieutenant William Braunersreuther, Charleston’s navigator and anchorman of the Naval Academy’s class of 1876.104 Early on 21 June—accompanied by Ensign Waldo Evans, five sailors, and two newspaper correspondents—Braunersreuther set off for shore.105 The group climbed on board one of Charleston’s whaleboats, which the cruiser’s steam launch towed toward land.106 Governor Marina’s interpreter, who had boarded Charleston earlier that morning to deliver a message, served as their pilot. Armed with a holstered pistol, Braunersreuther sternly warned him, “We are prepared for anything that may happen, and at the least sign of treachery you die first.”107 Once the water became too shallow for the steam launch to proceed, the whaleboat was detached and rowed the rest of the way, a white flag fluttering from its bow.108

When Braunersreuther and his party reached shore, the landing force that Glass and Anderson had planned the previous evening was still assembling. Lieutenant Myers commanded the Joint force of Marines and soldiers.109 A stiff wind was blowing, making the water choppy. It was 0900 by the time Lieutenant Myers and Charleston’s Marine guard reached Australia to rendezvous with two 85-man companies from the 2d Oregon Volunteer Infantry Regiment.110 A journalist embedded on board Australia described the Marines as “a fine-looking lot of men, well set up and soldierly in appearance.”111 They were armed with M1895 Lee Navy straight-pull rifles.112 Soon after Charleston’s Marines reached Australia, the Joint force’s final contingent—10 Marines from City of Pekin—arrived.113 Because of developments on shore, however, Myers’s landing force never landed.

When Braunersreuther reached shore at Piti—a port on the north side of Apra’s harbor—Governor Marina, Lieutenant García, and two other Spanish officers were awaiting him.114 After a formal introduction, Braunersreuther handed the governor an envelope containing a demand from Captain Glass for “the immediate surrender of the defenses of the island of Guam, with arms of all kinds, all officials and persons in the military service of Spain now in this island.”115 Braunersreuther noted that the time was 1015 and, as he later summarized the dialogue, “called attention to the fact that but one half hour would be given for a reply.” He also “casually informed the governor that he had better take into consideration the fact that we had in the harbor three transports loaded with troops and one war vessel of a very formidable nature.”116 Even while Myers’s Joint landing force remained offshore, it had a psychological impact. Lieutenant García’s report stated that within five minutes of the beach, the Americans had positioned “two squadrons with 18 large gunboats, each of them carrying 40 to 50 landing troops.”117 Although that assessment almost doubled the size of Myers’s Joint force while greatly underestimating how long it would have taken it to reach shore, Lieutenant García’s report suggests that the landing party constituted an effective show of force.

Lt William Braunersreuther, USS Charleston’s navigator, demanded and received Governor Juan Marina Vega’s surrender and then, supported by Charleston’s Marine guard, oversaw the disarming of Guam’s Spanish garrison. Photo by Douglas White, Overland Monthly 35, no. 207 (March 1900): 230

After receiving Lieutenant Braunersreuther’s instructions, the Spanish governor and his retinue withdrew to a nearby building. Twenty-five minutes later, a steam launch chugged toward shore, towing six boats filled with half of Myers’s Joint landing force.118 At 1044, with only a minute to spare before the deadline, Governor Marina emerged from the building where he and his aides had been sequestered.119 He handed Braunersreuther a sealed envelope addressed to Captain Glass.120 When the American officer proceeded to break the seal, Marina exclaimed, “Ah! but it is for the commandante.” Braunersreuther curtly replied, “I represent him here.”121 Even though an interpreter was present, Braunersreuther later recounted, “I forgot all about using him.” Instead, the “whole affair was transacted in Spanish.” Braunersreuther explained, “I did not want them to get a chance to think even before it was too late.”122

Handwritten in Spanish, Governor Marina’s letter stated:

Being without defenses of any kind and without means for meeting the present situation, I am under the sad necessity of being unable to resist such superior forces and regretfully to accede to your demands, at the same time protesting against this act of violence, when I have received no information from my Government to the effect that Spain is in war with your nation.

God be with you!123

After reading the letter, Braunersreuther informed Governor Marina and the other Spanish officers, “Gentlemen, you are now my prisoners; you will have to repair on board the Charleston with me.”124 Alarmed by that announcement, the Spaniards objected that they lacked necessities, such as a change of clothes.125 Braunersreuther’s official report summarized his reply:

I assured them that they could send messages to their families to send clothes and anything else they might desire, and that I would have a boat ashore at 4 p.m. ready to take off for them anything sent down. I would even secure passage for each of their families as they might desire and give them a safe return to Petey.126

Governor Marina was not appeased. He complained, “You came on shore to talk over matters, and you make us prisoners instead.”127 Parrying the implicit attack on his honor, Braunersreuther responded, “I came on shore to hand you a letter and to get your reply. In this reply, now in my hands, you agree to surrender all under your jurisdiction. If this means anything at all it means that you will accede to any demand I may deem proper to make.”128 After delivering that rebuke, Braunersreuther directed the Spanish governor to write an order summoning two companies of soldiers stationed at Agaña, instructing their commanding officer to arrive at the Piti landing by 1600 with all arms, ammunition, and Spanish flags on the island.129 As Braunersreuther later recounted, when the Spanish officers “protested and demurred,” he replied, “Senors, it must be done.”130 After Governor Marina complied and a messenger was dispatched to deliver the order to Agaña, Braunersreuther told the dejected Spaniards that they could write to their families. Half an hour later, Governor Marina handed three sheets of paper to Braunersreuther. The American officer declined to take them, explaining that it was a private letter that the governor was free to have delivered without review.131 At that, the overwhelmed Spanish governor crossed his arms on his desk, lowered his head, and sobbed.132

Governor Marina and his three staff officers were loaded into the waiting whaleboat.133 Just as they set off, a tropical deluge drenched both captives and captors.134 The brooding Spanish officers managed to smoke cigarettes amid the downpour.135 As the rain slackened, Braunersreuther signaled to Lieutenant Myers and his Joint landing force—also drenched—to return to their ships.136 Braunersreuther then delivered his four prisoners to Charleston.137

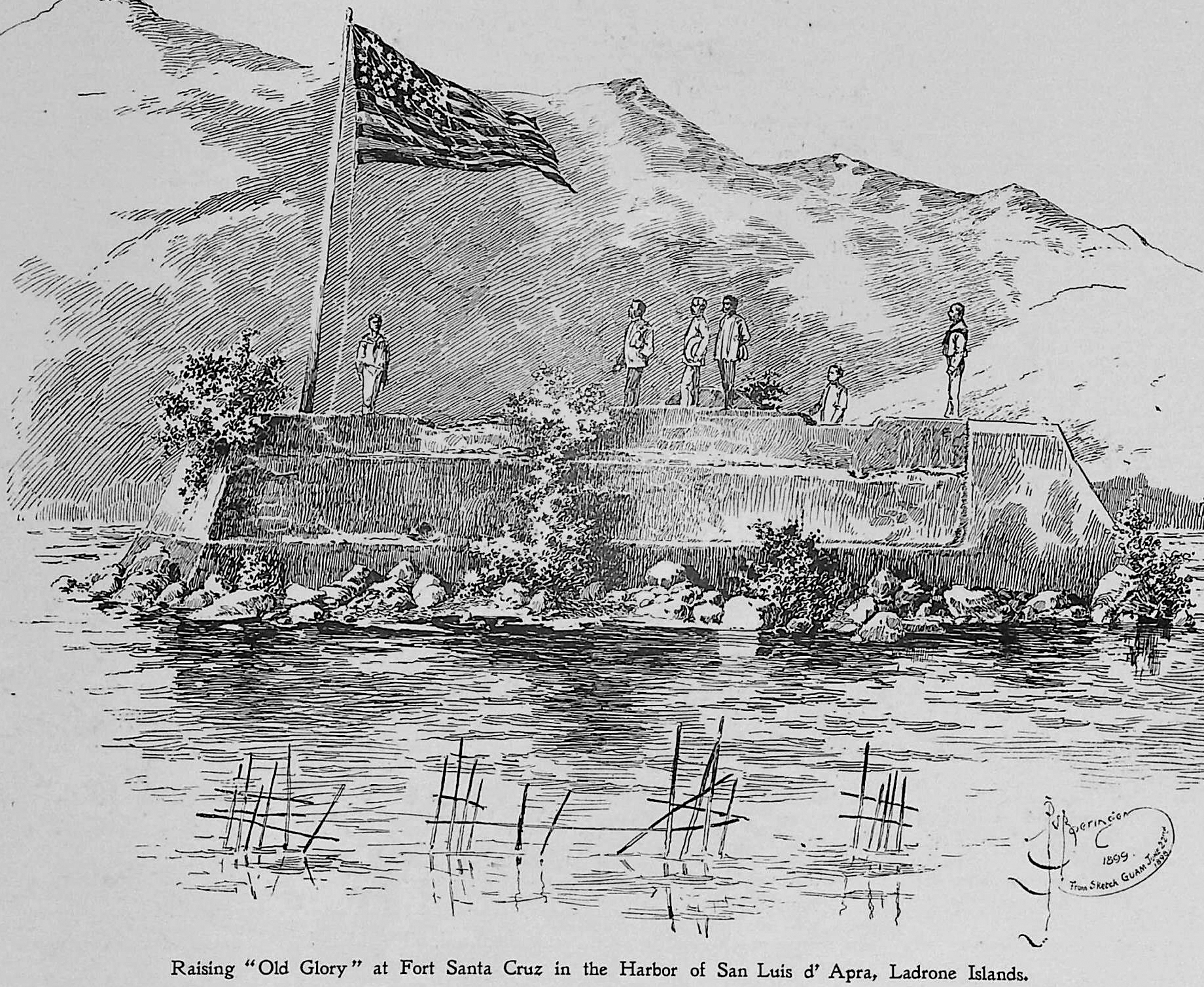

At 1445 that afternoon, Charleston’s guns once again boomed.138 This time, they were firing a salute—to the American flag as it was raised above the dilapidated Fort Santa Cruz in Apra’s harbor.139 Captain Glass intended the ceremony as an assertion of U.S. control of the island. His official report on his operations at Guam, dated 24 June 1898, stated, “Having received the surrender of the Island of Guam, I took formal possession at 2.45 p.m., hoisting the American flag on Fort Santa Cruz and saluting it with 21 guns from the Charleston.”140 Rear Admiral Dewey expanded Glass’s claim. In his 19 September 1898 report on U.S. naval operations in Asia, Dewey referred to Charleston having “taken possession, in the name of the United States, of Guam and the Ladrone Islands.”141

Glass’s visit to Fort Santa Cruz for the flag-raising ceremony convinced him that, despite his orders to “destroy any fortifications” on Guam, it was unnecessary to do so. The dilapidated fort was already “in a partly ruinous condition,” rendering it unnecessary “to expend any mines in blowing it up.” The other forts on the island, he continued, “are of no value.”142

An hour after the flag-raising ceremony, Lieutenant Braunersreuther returned ashore. Ensign Evans once again accompanied him, along with 16 sailors and Charleston’s Marine guard.143 The water near shore was shallow, compelling the Americans to climb out of their boats and haul them over a reef.144 Arriving a bit after the appointed hour of 1600, they found two Spanish naval infantry lieutenants with two companies of soldiers—one Spanish, the other Guamanian—standing in formation.145 Offshore, Charleston’s guns were shotted, ready to fire on Braunersreuther’s signal if the enemy troops offered resistance.146 The senior Spanish officer saluted Braunersreuther, who informed the assembly he was there to accept their surrender, as ordered by Governor Marina.147 While Braunersreuther spoke, Charleston’s Marine guard, augmented by eight sailors, fanned out in front of the two enemy companies.148 With this show of force in place, Braunersreuther ordered the senior Spanish officer to command his men to surrender their weapons.149 Each Spanish soldier then approached Ensign Evans, saluted, opened the breech block of his Mauser rifle to show that the weapon was unloaded, and handed the rifle to the American officer. Ensign Evans then closed the block and handed the rifle to an American sailor, who passed it along a line of his shipmates to one of the waiting boats. Each Spanish soldier also removed his belt, which held a cartridge box and bayonet, as well as his haversack and handed them to Ensign Evans, who gave the equipment to a sailor to pass along for stowage. The soldier then saluted Evans again and returned to formation. That process was repeated for each of the 54 Spanish enlisted men.150 A reporter described the Spanish soldiers as “little more than boys.”151 The company of Guamanian soldiers then underwent the same process, though they were armed with Remington rifles rather than Mausers.152 After the last of the enlisted troops relinquished their rifles and gear, Braunersreuther drew the two Spanish officers aside and told them, “Gentlemen, it is my unpleasant duty to be obliged to disarm you also. I am compelled to ask for your swords and revolvers.”153 As the Spanish officers handed over their weapons, the U.S. Marines saluted them by presenting arms.154 Braunersreuther directed the Spanish lieutenants to tell their men they may say goodbye to their Guamanian comrades.155 Realizing the Americans were about to take them away as prisoners of war, the Spanish soldiers erupted in lamentations.156 The Guamanians, on the other hand, greeted the news with quiet satisfaction.157 When Braunersreuther formally released them, the Guamanians soldiers ripped the brass buttons and collar insignias from their uniforms, handing some to the American Marines and sailors as souvenirs.158

After Governor Juan Marina Vega surrendered Guam, Capt Henry Glass led a small party to Fort Santa Cruz, where they raised an American flag as Charleston rendered a 21-gun salute. Drawing by Pierre N. Boeringer, as reproduced in Douglas White, On to Manila (1899)

The Americans commandeered a sampan anchored nearby and the Marines, with fixed bayonets, loaded the 54 Spanish enlisted men onto it.159 The two Spanish officers boarded another boat with Braunersreuther, along with four surrendered Spanish flags. As the flotilla set off, the Guamanian soldiers cheered from the landing.160

The Spanish prisoners reached Charleston just as the sun was setting.161 After being marched up the cruiser’s gangway, they—along with the prisoners seized earlier that day—were transferred to the more spacious City of Sydney.162

In a report to Captain Glass detailing the execution of his mission ashore, Braunersreuther noted the operation’s danger while praising the officers, Marines, and sailors who conducted it:

In closing my report I desire to call attention to the absolute obedience and splendid discipline of all the force (30 marines and 16 sailors) I had with me, particularly to the efficient aid received from Lieut. J. T. Myers, U. S. M. C., and Ensign Waldo Evans, U. S. N.

Both of these gentlemen were fully alive to the dangers and necessities of the occasion and rendered most valuable assistance.

A casual glance at the class and number of the rifles captured, together with the quantity of the ammunition, will demonstrate the care that had to be exercised in disarming and making prisoners of a force of men more than double the number I had with me, and will also call attention to the fact that the entire undertaking was neither devoid of danger nor risk.163

The next day, Charleston received 125 tons of coal from City of Pekin and the four American ships steamed off to the Philippines.164 The process of asserting U.S. sovereignty over Guam lurched forward. During the coaling operation, according to a contemporaneous newspaper account, “Captain Glass sent for Francis Portusach, who is the single American citizen residing on the Ladrones, and into his hands placed the duty of keeping a lookout over affairs there until he can be relieved by either a civil or military Governor.”165 Glass departed without leaving any naval or Army personnel on Guam.

Once the American vessels left, the senior Spanish official who remained on the island reasserted Spanish sovereignty over Guam. On 30 June 1898, Treasury Administrator José Sixto wrote a letter to Spain’s minister of overseas territories recounting the American operation while disclaiming continued U.S. legal possession of Guam:

In view of the fact that the North American squadron limited themselves to hoisting a flag and taking the garrison on the island as prisoners, in view of the fact that they did not leave a single garrison soldier, representative, authority or flag on the island to prove that they had taken possession of the territory, I considered the act of sovereignty that had been carried out to be perfectly null and void.166

Sixto disparaged “the enemy squadron[’s]” assertion of sovereignty “as nothing more than a moral act.” He, therefore, felt obliged, “as a Spaniard and as a public official on the island, to continue to consider the island Spanish, which in fact I carried out from the very moment the enemy left, restoring and taking charge of the government of the Mariana islands in the name of Spain.” Sixto also assured the minister of overseas territories that “the natives have continued to pay their contributions and tributes and to show their affection and attachment to the fatherland.”167

Control over Guam proceeded on two tracks. Spanish officials and prelates exercised de facto control over the populace while the United States asserted de jure possession of the island and used San Luis d’Apra’s port to facilitate its naval operations in Asia. Amid that dissonance, Spanish and U.S. negotiators signed the Treaty of Paris on 10 December 1898. Among that treaty’s provisions was Spain’s agreement to cede Guam to the United States.168 The United States did not receive possession of any other island in the Mariana chain. Spain sold the rest of the archipelago—along with the Caroline Islands, the Marshall Islands, and the Palau Islands—to Germany.169

Before either party ratified the Treaty of Paris, President William McKinley issued an executive order on 23 December 1898 providing that the “Island of Guam in the Ladrones is hereby placed under the control of the Department of the Navy. The Secretary of the Navy will take such steps as may be necessary to establish the authority of the United States and give it necessary protection and government.”170 The following month, the U.S. Navy took steps to carry out that presidential mandate.

USS Bennington (PG 4), captained by Commander Edward D. Taussig, arrived at San Luis d’Apra’s harbor on 23 January 1899.171 A week later, Commander Taussig announced that “the United States Department of the Navy” was seizing all public lands bordering the port that had previously been owned by Spain.172 Bennington’s logbook entry for the 0400 to 0800 watch on 1 February includes the notation: “7.00 landed the battalion to take possession of the Island of Guam.”173 At 1030 that same morning, Commander Taussig directed the simultaneous hoisting of American flags over Fort Santa Cruz and on a flag staff facing the governor’s palace in Agaña.174 Bennington’s 16-member Marine guard probably participated in at least one of those flag raisings.175 When Commander Taussig took those actions, the Treaty of Paris still had not been ratified by either party, suggesting that the United States relied on Charleston’s operation in June 1898 to establish its acquisition of Guam from Spain. When Bennington weighed anchor to depart for Manila on 15 February 1899, like Captain Glass before him, Commander Taussig left no U.S. naval or Army personnel on the island.176

Yet another assertion of U.S. sovereignty over Guam occurred on 10 August 1899, three days after USS Yosemite (1892) arrived at San Luis d’Apra’s harbor.177 By then, both parties had ratified the Treaty of Paris, which entered into force on 11 April 1899.178 On board Yosemite were Navy captain Richard P. Leary, the newly assigned governor of Guam, and two companies of Marines under the command of Major Allen C. Kelton who would establish the island’s Marine barracks.179 Captain Leary issued a “Proclamation to the Inhabitants of Guam.” After referring to the Treaty of Paris’s ceding of Guam to the United States, Leary announced his “actual occupation and administration of this Island, in the fulfillment of the Rights of Sovereignty thus acquired.”180 The United States had finally established effective control over Guam, which would continue until a Japanese invasion force seized the island on 10 December 1941.181

One of Captain Leary’s first official acts as Guam’s governor was to request more Marines. Near the end of his first month, he reported to the secretary of the Navy that “too much cannot be said in praise of the Officers and men of the Guam Battalion of Marines during the passage and since their arrival here, as their conduct has been excellent and on all occasions they have evinced an enthusiastic willingness and untiring energy in all work and duties that have been assigned to them.”182 Leary requested “that another Battalion of Marines and Officers be sent here at the earliest convenience, especially additional Officers, as there is much necessary work in the island that will keep them all continuously employed.”183 One and a quarter centuries after Captain Leary made that request, Guam will once again experience an influx of Marines. As Theodor Reik wrote, “It has been said that history repeats itself. This is perhaps not quite correct; it merely rhymes.”184

•1775•

endnotes

- Irene Loewenson, “New in 2024: Marines Start Moving from Japan to New Base on Guam,” Marine Corps Times, 29 December 2023; and U.S. Department of State, Office of the Spokesperson, “Joint Statement of the Security Consultative Committee,” press release, 26 April 2012.

- “History,” Reactivation and Naming, Marine Corps Base Camp Blaz, U.S. Marine Corps, accessed 11 June 2024.

- Loewenson, “New in 2024.”

- “History,” Reactivation and Naming, Marine Corps Base Camp Blaz.

- Dictionary of American Naval Fighting Ships, vol. 2 (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1963), 82; and “A Possible Race to Manila,” Sun (Baltimore), 12 May 1898, 1.

- USS Charleston logbook, 5 May 1898–15 November 1898, entry 118, Record Group (RG) 14, National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, DC, (NARA I), “Armament” page.

- Douglas White, On to Manila (San Francisco, CA: Geo. Spaulding, 1899), 2; and Robert E. Coontz, From Mississippi to the Sea (Philadelphia, PA: Dorrance, 1930), 200.

- Muster rolls, USS Charleston, 5 May 1898–30 June 1899, entry 134, RG24, NARA I.

- The reporters embedded aboard Charleston were Sol N. Sheridan of the San Francisco Call, Douglas White of the Examiner (San Francisco), and E. Langley Jones of the Associated Press. Charleston logbook, 18 May 1898. Oscar King Davis of the Sun (New York) and Pierre N. Boeringer, an artist working for the San Francisco Call and New York Herald, were embedded on board the troop transport Australia. “The Boys in Blue,” Hawaiian Star, 1 June 1898, 1.

- U.S. Marine Corps muster roll, USS Charleston, 2d Rate, 5 May–18 May 1898, T977, roll 12, NARA I.

- Bvt MajGen George W. Cullum, Biographical Register of the Officers and Graduates of the U.S. Military Academy at West Point, N.Y. from Its Establishment in 1802, to 1890, 3d ed., vol. 1 (Boston, MA: Houghton, Mifflin, 1891), 562; and Robert Rosen, Jewish Confederates (Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 2000), 119.

- In a letter to the Confederate States Senate, Jefferson Davis explained that he replaced Myers as quartermaster general because “the public interest required an officer of greater ability and one better qualified to meet the pressing emergencies of the service during the war.” Jefferson Davis to the Senate, 27 January 1864, reprinted in Journal of the Congress of the Confederate States of America, 1861–1865 (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1904), 3:627. On the other hand, rumors attributed Davis’s decision to remove Myers as quartermaster general “to Myers’s wife calling the dark-complexioned Mrs. Davis a ‘squaw’.” Bruce S. Allardice, Confederate Colonels: A Biographical Register (Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 2008), 287.

- Jack Shulimson, The Marine Corps’ Search for a Mission, 1880–1898 (Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 1993), 135.

- Glenn M. Harned, Marine Corps Generals, 1899–1936: A Biographical Encyclopedia (Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 2015), 120.

- U.S. Naval Academy Academic and Conduct Records of Cadets, 1881–1908, vol. 11, 290⅛, Special Collections and Archives, Nimitz Library, U.S. Naval Academy; and Annual Register of the United States Naval Academy, Annapolis, Md., Thirty-Eighth Academic Year, 1887–’88 (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1887), 33.

- U.S. Naval Academy Academic and Conduct Records of Cadets, 1881–1908, vol. 11, 290½.

- “Naval Academy Graduates,” Evening Capital (Annapolis), 3 June 1892, 3.

- Shulimson, The Marine Corps’ Search for a Mission, 135; and Annual Register of the United States Naval Academy, Annapolis, Md., Fiftieth Academic Year, 1894–’95 (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1894), 46–47, 49–50.

- “Reorganization of the Navy,” Sun (Baltimore), 20 August 1894, 2; and Naval Appropriation Act of July 28, 1894, ch. 165, 28 Stat. 123, 124 (1894).

- Journal of the Executive Proceedings of the Senate of the United States of America, vol. 29, pt. 1 (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1909), 782.

- “Capt. Myers’s Leap to Fame,” Evening Post (New York), 25 August 1900, 10.

- Shulimson, The Marine Corps’ Search for a Mission, 135.

- Grover Cleveland to Senate of the United States, 12 February 1895, in Journal of the Executive Proceedings of the Senate of the United States of America, vol. 29, pt. 2 (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1909), 927, nominating Myers and Ball for appointment to their new positions by transfer; and Journal of the Executive Proceedings of the Senate of the United States of America, vol. 29, pt. 2, 949, Senate confirmation.

- Record of Myers, John Twiggs, sheet no. 1, John Twiggs Myers Official Military Personnel File, Service No. 703, National Personnel Records Center, St. Louis, MO; and USS Charleston logbook, 9 May 1898.

- USS Charleston logbook, 9 May 1898.

- “War–Time Wedding,” Examiner (San Francisco), 29 April 1898, 7. Myers would later receive a brevet promotion to major “for distinguished conduct in the presence of the enemy at the defense of the legations” while in Beijing during the Boxer Rebellion of 1900. When he retired from the Marine Corps in 1935, he was a major general. “China Heroes Rewarded,” Boston Sunday Globe, 10 March 1901, 4; and Record of Myers, John Twiggs, unnumbered sheet following sheet no. 9. He was later elevated to lieutenant general on the retired list. “Two Retired Officers of Marines Named Lieutenant Generals,” Evening Star (Washington, DC), 16 April 1942, B-1.

- USS Charleston logbook, 18 May 1898; and “Charleston Off for Manila,” San Francisco Call, 19 May 1898, 5.

- USS Charleston logbook, 19 May 1898.

- Douglas White, “Charleston’s Trip Delayed,” Examiner (San Francisco), 20 May 1898, 2; Long to Dewey, 20 May 1898, in Appendix to the Report of the Chief of the Bureau of Navigation, 1898 (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1898), 99, hereafter 1898 Appendix. The Mariana Islands were also called the Ladrones, the Spanish word for thieves. The islands acquired that pejorative appellation during Ferdinand Magellan’s 1521 stop in the islands. Lt Frederick J. Nelson, USN, “Why Guam Alone Is American,” U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings 62, no. 8 (August 1936): 1131.

- Secretary of the Navy to Commanding Officer, U.S.S. Charleston, 10 May 1898, 1898 Appendix, 151.

- USS Charleston logbook, 21 May 1898.

- USS Charleston logbook, 22 May 1898.

- White, On to Manila, 2.

- White, On to Manila, 2.

- USS Charleston logbook, 29 May 1898; and “U.S.S. Charleston,” Honolulu Advertiser, 30 May 1898, 1.

- USS Charleston logbook, 1 June 1898; and Sol N. Sheridan, “Target Practice Previous to the Taking of Guam,” San Francisco Call, 3 August 1898, 1.

- “Charleston at Honolulu,” Sun (New York), 8 June 1898, 2; “Transports Depart,” Hawaii Herald, 9 June 1898, 4; and Leslie W. Walker, “Guam’s Seizure by the United States in 1898,” Pacific Historical Review 14, no. 1 (March 1945): 1.

- “Gen. T. McA. Anderson Dies,” New York Times, 10 May 1917, 13; “After Long Service,” Courier–Journal (Louisville), 21 December 1899, 2; and “Gen. Anderson Dies as He Prepares to Preside at Banquet,” Oregon Journal, 9 May 1917, 1.

- Report of the Secretary of the Navy, 15 November 1898, in Annual Reports of the Navy Department for the Year 1898 (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1898), 21; and Oscar King Davis, Our Conquests in the Pacific (New York: Frederick A. Stokes Company, 1899), 57. An Army communication sent the day before City of Pekin sailed from San Francisco stated that the “Navy contingent” aboard the vessel numbered “11 officers and 76 enlisted men.” MajGen Elwell Otis, U.S. Volunteers, to AdjGen, U.S. Army, 24 May 1898, Correspondence Relating to the War with Spain, vol. 2 (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1902), 671–72. It is unclear how many of the 76 enlisted men were Marines.

- Douglas White, “Hawaii Honors Our Soldiers,” Sunday Examiner (San Francisco), 19 June 1898, 15; and Pandia Ralli, “Campaigning in the Philippines,” Overland Monthly 33, no. 194 (February 1899): 157–58.

- USS Charleston logbook, 8 June 1898.

- Official Register of the Officers and Midshipmen of the United States Naval Academy, Newport, Rhode Island, December 31, 1863 (Newport, RI: Frederick A. Pratt, 1864), 11; and Park Benjamin, The United States Naval Academy (New York: G. P. Putnam’s Sons, 1900), 253–57.

- Lewis Randolph Hamersly, Records of Living Officers of the U.S. Navy and Marine Corps, 5th ed. (Philadelphia, PA: L. R. Hamersly, 1894), 107–8.

- “Hole in the Cincinnati,” New York Times, 17 November 1894, 1; and Secretary of the Navy H. A. Herbert, Action on Court of Inquiry no. 4868, box 56, entry 30, RG 125, NARA I.

- “Charleston Is Commissioned,” Examiner (San Francisco), 6 May 1898, 3; and 31 Cong. Rec. 4244, 4252 (1898).

- Coontz, From Mississippi to the Sea, 200.

- Sheridan, “Target Practice,” 1.

- Secretary of the Navy to Commanding Officer, U.S.S. Charleston, 10 May 1898, 1898 Appendix, 151.

- For example, Long to Dewey, 25 June 1898, 1898 Appendix, 108 (referring to the Second Army Division’s expected arrival at Guam on 10 July to meet convoying vessel); and Long to Dewey, 29 June 1898, 1898 Appendix, 109 (referring to USS Monterey [BM 6] sailing from San Diego via Honolulu and Guam).

- E. Langley Jones, “How Guam Was Taken,” San Francisco Chronicle, 3 August 1898, 2.

- Davis, Our Conquests, 31–32.

- USS Charleston logbook, 13 June 1898; and Sheridan, “Target Practice Previous to the Taking of Guam,” 1.

- Shulimson, The Marine Corps’ Search for a Mission, 130–32, 147, 164–65.

- Shulimson, The Marine Corps’ Search for a Mission, 166–67, 195; and Report of the Commandant of United States Marine Corps, 24 September 1898, in Annual Reports of the Navy Department for the Year 1898, 830–31.

- USS Charleston logbook, 15 June 1898.

- USS Charleston logbook, 17 June 1898; Sheridan, “Target Practice Previous to the Taking of Guam,” 1; Jones, “How Guam Was Taken,” 2; and Davis, Our Conquests, 42–43.

- USS Charleston logbook, 18 June 1898; and Jones, “How Guam Was Taken,” 2.

- Jones, “How Guam Was Taken,” 2.

- USS Charleston logbook, 19 June 1898; and Jones, “How Guam Was Taken,” 2.

- USS Charleston logbook, 19 June 1898.

- USS Charleston logbook, 19 June 1898.

- Letter from Father William D. McKinnon, June 26, 1898, in Monitor (San Francisco), 20 August 1898, 405.

- Jones, “How Guam Was Taken,” 2.

- Jones, “How Guam Was Taken,” 2.

- Douglas White, “Capture of Guam and Hoisting of Stars and Stripes in the Ladrones,” Examiner (San Francisco), 3 August 1898, 1.

- White, “Capture of Guam and Hoisting of Stars and Stripes in the Ladrones,” 1.

- Davis, Our Conquests, 45; and Capt A. Farenholt (MC), USN, “Incidents on the Voyage of U.S.S. ‘Charleston’ to Manila in 1898,” U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings 50, no. 255 (May 1924): 756.

- Farenholt, “Incidents,” 756; and Davis, Our Conquests, 49.

- USS Charleston logbook, 22 June 1898; Sheridan, “Target Practice,” 1; Davis, Our Conquests, 87–88; and Oscar King Davis, “The Taking of Guam,” Harper’s Weekly, 20 August 1898, 830.

- White, “Capture of Guam,” 1; USS Charleston logbook, 20 June 1898; and Davis, Our Conquests, 44–46.

- Davis, Our Conquests, 47.

- White, “Capture of Guam and Hoisting of Stars and Stripes in the Ladrones,” 1.

- Jones, “How Guam Was Taken,” 2.

- Jones, “How Guam Was Taken,” 2; and Davis, Our Conquests, 48–50.

- Davis, Our Conquests, 50.

- 2dLt John T. Myers to Heyward Myers, 27 August 1898, 1, box 1, folder 2, John Twiggs Myers Personal Papers (Coll/3016), Archives Branch, Marine Corps History Division, Quantico, VA.

- Davis, Our Conquests, 50–51.

- Jones, “How Guam Was Taken,” 2.

- Farenholt, “Incidents,” 756; and Sol N. Sheridan, “Cruiser Charleston Fires Her Maiden Hostile Shells,” San Francisco Call, 3 August 1898, 1.

- Jones, “How Guam Was Taken,” 2.

- Capt Henry Glass’s Report to Secretary of the Navy, 24 June 1898, 1898 Appendix, hereafter Glass’s Report, 152; USS Charleston logbook, 20 June 1898; and J. T. Myers, “Extract from Journal Kept on Board U.S.S. Charleston, 1898,” Guam Recorder 9, no. 11 (February 1933): 187.

- Jones, “How Guam Was Taken,” 2.

- Sheridan, “Cruiser Charleston,” 1; Jones, “How Guam Was Taken,” 2; White, “Capture of Guam,” 2; Davis, Our Conquests, 52–53; and Frank Portusach, “History of the Capture of Guam by the United States Man-of-War Charleston and Its Transport,” U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings 43, no. 170 (April 1917): 707–18.

- Davis, Our Conquests, 53–55.

- Douglas White, “The Capture of the Island of Guam,” Overland Monthly 35, no. 207 (March 1900): 229.

- White’s account, as well as some others, referred to Lt García as LtCdr Gutierrez. White, “The Capture of the Island of Guam,” 229.

- White, “The Capture of the Island of Guam,” 229–30.

- White, “The Capture of the Island of Guam,” 230.

- Sheridan, “Cruiser Charleston,” 1.

- “Marine General Recalls Capture of Guam in Musical Comedy Style,” Philadelphia Inquirer, 10 June 1931, 3; and “Behind the Scenes at the Nation’s Capital,” Philadelphia Inquirer, 23 February 1931, 8.

- Portusach, “History of the Capture of Guam,” 708; and Naturalization of Francisco P. Portusach, 12 October 1888, no. 18-369, Clerk of the Circuit Court of Cook County Archives, Chicago, IL.

- Portusach, “History of the Capture of Guam,” 708.

- Teniente de Navío D. Francisco García Gutiérrez to Leopoldo Boada, de la Comandancia General del Apostadero y Escuadra de Filipinas, 24 October 1898, rin Referente a la evacuación de las Islas Marianas, 1 December 1898, España, Ministerio de Defensa, Archivo Histórico de la Armada Juan Sebastián de Elcano 525, Ms. 1532/0014 (Legajó 1532, 57–62), trans. by Beatriz Muñoz Santero, hereafter García’s Report. In a letter dated 24 October 1898, Lt García sent a description of the U.S. operations in Guam to Spain’s general command of the Philippine Station and Squadron. A communiqué from Leopoldo Boada of the general staff to the Minister of the Navy dated 1 December 1898 included a transcription of García’s 24 October 1898 report. Boada’s letter, with a stamp showing it was received by the Ministry of the Navy on 21 January 1900, is located at the Archivo del Museo Naval de Madrid.

- García’s Report, 58.

- García’s Report, 58.

- García’s Report, 59.

- García’s Report, 59.

- Sheridan, “Cruiser Charleston,” 1.

- Juan Marina Vega to Henry Glass, 20 June 1898, Addendum A to Glass’s Report, 154.

- Glass’s Report, 152; and Davis, Our Conquests, 57.

- White, “Capture of Guam,” 2; Lt W. Braunersreuther to Capt Henry Glass, 21 June 1898, hereafter Braunersreuther’s Report, Addendum E to Glass’s Report, 154; and Davis, Our Conquests, 57.

- USS Charleston logbook, 20 June 1898; and White, On to Manila, 12.

- White, “Capture of Guam,” 2; and White, On to Manila, 12.

- Annual Register of the United States Naval Academy, Annapolis, Md., Twenty–Seventh Academic Year, 1876–’77 (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1876), 12–13.

- White, “Capture of Guam,” 2. Evans, who would rise to the grade of Navy captain and serve as the naval governor of the U.S. Virgin Islands and American Samoa, was a Naval Academy classmate of Myers’s before Myers was set back to the class of 1892. “Naval Cadets Graduate,” Evening Star (Washington, DC), 6 June 1891, 15; and “Captain Evans, 66, Navy Officer, Dead,” New York Times, 16 April 1936, 25.

- Davis, Our Conquests, 59.

- White, “Capture of Guam,” 2.

- Davis, Our Conquests, 59.

- Davis, Our Conquests, 57; and 1stLt and Adj Henry P. McCain, 14th Infantry, to Commanding Officer, 2d Oregon Infantry, 20 June 1898, in 1898 Appendix, 156.

- Davis, Our Conquests, 57.

- Davis, Our Conquests, 57–58.

- Davis, Our Conquests, 58; and “Of the 198 Cal. 6m/m Rifles (30) Are for Marine Guard,” “Armament,” in USS Charleston logbook.

- Davis, Our Conquests, 59.

- Davis, Our Conquests, 62–63; and García’s Report, 60. The two additional officers accompanying Governor Marina were his secretary, Capt Pedro Duarte of the Spanish Army, and the port’s health officer, Dr. José Romero, surgeon, Spanish Army. Davis, “The Taking of Guam,” 830; and Prisoners and Property Captured at San Luis d’Apra, Guam, 21 June 1898, Addendum F to Glass’s Report, 157.

- Braunersreuther’s Report, 155; and Capt Henry Glass to Governor Juan Marina Vega, 20 June 1898, Addendum B to Glass’s Report, 154.

- Braunersreuther’s Report, 155.

- García’s Report, 60.

- Davis, Our Conquests, 63.

- Braunersreuther’s Report, 155.

- Braunersreuther’s Report, 155; and Lt William Braunersreuther to Augustus Pollack, 24 June 1898, in “How Spain Lost Guam,” San Francisco Chronicle, 8 August 1898, 3.

- Braunersreuther’s Report, 155.

- Braunersreuther to Pollack, 3.

- Governor Juan Marina Vega to Capt of the North American Cruiser Charleston, 21 June 1898, Addendum D to Glass’s Report, 155; and “VI 1898 GUAM–AFFAIRS WITH” folder, box 665, RG 45, NARA I (original).

- Braunersreuther’s Report, 155.

- Braunersreuther’s Report, 155; and Sheridan, “Capture of Guam,” 2.

- Braunersreuther’s Report, 155.

- Braunersreuther to Pollack, 3.

- Braunersreuther to Pollack, 3.

- Braunersreuther to Pollack, 3.

- Braunersreuther to Pollack, 3.

- Davis, Our Conquests, 67; and Braunersreuther’s Report, 155.

- Davis, Our Conquests, 67.

- Davis, Our Conquests, 68.

- Davis, Our Conquests, 68; and White, “Capture of Guam,” 2.

- White, “Capture of Guam,” 2.

- Braunersreuther’s Report, 155; Davis, Our Conquests, 61, 68; and White, “Capture of Guam,” 2.

- Braunersreuther’s Report, 156; and USS Charleston logbook, 21 June 1898.

- USS Charleston logbook, 21 June 1898; and Davis, Our Conquests, 71.

- USS Charleston logbook, 21 June 1898; and Davis, Our Conquests, 44, 71.

- Glass’s Report, 153.

- RAdm George Dewey to Secretary of the Navy, 19 September 1898, in 1898 Appendix, 128.

- Glass’s Report, 153.

- Braunersreuther’s Report, 156.

- Myers, “Extract from Journal,” 187; and White, “Capture of Guam,” 2.

- Davis, Our Conquests, 72–75.

- Davis, Our Conquests, 72.

- Davis, Our Conquests, 72–73.

- Davis, Our Conquests, 73.

- Davis, Our Conquests, 73.

- Davis, Our Conquests, 73–74.

- Sheridan, “Cruiser Charleston,” 1.

- Davis, Our Conquests, 74. No source has been located specifying the models of the Mauser and Remington rifles seized from the Spanish garrison on Guam. By the time of the Spanish-American War, most Spanish forces were armed with 7mm M1893 Mausers, which held five rounds of smokeless ammunition in a magazine and could be reloaded with stripper clips. The Guamanian soldiers’ rifles were likely the single-shot Remington “rolling-block” model, which fired black powder cartridges. Alejandro de Quesada, The Spanish-American War and Philippine Insurrection, 1898–1902 (Oxford, UK: Osprey Publishing, 2007), 36–37.

- Davis, Our Conquests, 74.

- Davis, Our Conquests, 74.

- Davis, Our Conquests, 74.

- Davis, Our Conquests, 75.

- Davis, Our Conquests, 75.

- Braunersreuther’s Report, 156; Davis, “The Taking of Guam,” 830; and Walker, “Guam’s Seizure by the United States in 1898,” 11. The portion of Walker’s article discussing the disarming of the Spanish garrison was based on John T. Myers’s journal entries, which Myers made available to Walker. Walker, “Guam’s Seizure by the United States in 1898,” 11n23. Oscar King Davis’s accounts of the sailors in the landing party receiving the Guamanian soldiers’ buttons and insignia while the Marines remained in formation is inconsistent with other accounts, including his own article in Harper’s Weekly. Compare Davis, “The Taking of Guam,” 830, with Davis, Our Conquests, 75; O. K. D., “Our Flag at Guam,” Sun (New York), 8 August 1898, 1, 3. His Harper’s Weekly account, which is consistent with Walker’s account based on Myers’s journal, is more credible.

- Myers, “Extract from Journal Kept on Board U.S.S. Charleston, 1898,” 187; and Sheridan, “Cruiser Charleston,” 1.

- Davis, Our Conquests, 75–76.

- White, “Capture of Guam,” 2.

- White, “Capture of Guam,” 2; and Glass’s Report, 153.

- Braunersreuther’s Report, 156.

- Charleston Logbook, 22 June 1898; Davis, Our Conquests, 87–88; and Davis, “The Taking of Guam,” 830.

- Douglas White, “Capture of Guam,” 2. Portusach later wrote that Capt Glass “asked me if I could take care of the island until some other officers or man-of-war might reach Guam, I being the only United States citizen at that time; I promised Captain Glass that I would do my best; he asked me if I was in need of aid, meaning soldiers for the island. I answered, ‘No,’ as the people are very good here.” Portusach, “History of the Capture of Guam,” 710–11. Robert F. Rogers seemed skeptical of Portusach’s claim. He observed that Capt Glass’s “casual request was not put in writing, if it was actually made; the U.S. Navy never confirmed it.” Robert F. Rogers, Destiny’s Landfall: A History of Guam, rev. ed. (Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press, 2011), 106. Portusach’s account is corroborated by White’s 1898 article.

- José Sixto to Minister of Overseas Territories, 30 June 1898, Archivo Histórico Nacional, Madrid, Spain (Filipinas Legajó 5359, no. 28), trans. by Beatriz Muñoz Santero.

- José Sixto to Minister of Overseas Territories, 30 June 1898.

- Treaty of Peace between the United States of America and the Kingdom of Spain, art. II, 30 Stat. 1754, 1755 (1899).

- Nelson, “Why Guam Alone Is American,” 1133.

- William McKinley, Executive Order, 23 December 1898, in Senate Document No. 111, 57th Cong., 2d Sess. (1903), 2.

- Dictionary of American Naval Fighting Ships, vol. 1 (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1959), 117–18; and USS Bennington logbook, 23 January 1899, entry 118, RG 14, NARA I.

- Order No. 2, E. D. Taussig, Commander U.S.N., Commanding U.S.S. Bennington and Senior Officer Present, 30 January 1899, entry 19, RG80, no. 9351, NARA I.

- USS Bennington logbook, 1 February 1899. That logbook entry was made by Lt Charles Brainard Taylor Moore, who went on to become governor of American Samoa and, later, a rear admiral. “Admiral Moore Dead,” New York Times, 5 April 1923, 19.

- Cdr Taussig Report to Secretary of the Navy, 1 February 1899, para. 1, entry 19, RG 80, no. 9351, NARA I.

- USS Bennington logbook, “Complement of Petty Officers, Seamen, Ordinary Seamen, Landsmen, Boys, and Maries on board of the U. S. S. Bennington, January 31st 1899.”

- USS Bennington logbook, 15 February 1899; and Rogers, Destiny’s Landfall, 109–10.

- Capt Leary Report to Secretary of the Navy, 28 August 1899, para. 1, entry 19, RG 80, no. 9351, NARA I, hereafter Leary’s Report.

- Treaties and Other International Agreements of the United States of America 1776–1949, vol. 11 (Washington, DC: Department of State, 1974), 614.

- William Edwin Safford, A Year on the Island of Guam (Washington, DC: H. L. McQueen, [1910?]), 1, 17, 38, 48; and U.S. Marine Corps muster roll, U.S.S. Yosemite at Guam, L.I., 1–31 August 1899, T977, roll 17, NARA I.

- Leary’s Report, para. 3; and Proclamation to the Inhabitants of Guam and to Whom It May Concern, 10 August 1899, entry 19, RG 80, no. 9351, NARA I.

- Thomas Wilds, “The Japanese Seizure of Guam,” Marine Corps Gazette 39, no. 7 (July 1955): 20–23.

- Leary’s Report, para. 17.

- Leary’s Report, para. 19.

- Theodor Reik, Curiosities of the Self (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1965), 133.

About the Author

Dwight Sullivan is a retired colonel of the U.S. Marine Corps Reserve and is a senior associate deputy general counsel in the DOD Office of General Counsel. He serves as an adjunct faculty member at George Washington University Law School and recently received a master’s in military history from Norwich University. The views expressed in this article are his alone and do not necessarily represent the views of DOD.

https://orcid.org/0009-0002-1565-195X.