PRINTER FRIENDLY PDF

EPUB

AUDIOBOOK

Abstract: The U.S. Marine Corps spent the years between the world wars developing a doctrine of opposed landings from the sea in an arena where the ocean provided the only maneuver space, but the opposed amphibious operation is not the province of ocean-borne amphibious assaults alone. The land-water interface impacts warfare well inland from the coast, and much can be learned from the application of riverine and lacustrine amphibious assaults found in history. One such example is the siege of Enniskillen Castle in Ireland in 1594. English operations at Enniskillen demonstrated the value of coordinated waterborne and land-based forces at the tactical level. Considering English lacustrine operations in the Irish Nine Years’ War (1593–1603) and U.S. riverine warfare experiences in the American Civil War and Vietnam War can inform Marine planners as they develop the tactics, techniques, and procedures of the Marine Littoral Regiments.

Keywords: riverine, amphibious, inland amphibious warfare, stand-in force, Marine Littoral Regiment, land-water interface, riverine assault, lacustrine assault, littorals, Nine Years’ War, Tyrone rebellion, Enniskillen Castle

Introduction

For many naval enthusiasts, the roots of amphibious warfare reach back only as far as the British disaster at Gallipoli in 1914–15. Looking more broadly, the use of the sea as a military maneuver space dates to antiquity, but primarily as navies transporting an army to an undefended landing site, after which the army engages in land warfare once established ashore. The U.S. Marine Corps famously spent the years between World War I and II developing a doctrine of opposed landings from the sea in an arena where the ocean provided the only maneuver space. Even today, amphibious doctrine talks of naval task forces and combined arms landing forces derived from that interwar development. But the opposed amphibious operation is not the province of ocean-borne amphibious assaults alone. The land-water interface impacts warfare well inland from the coast, and much can be learned from the application of riverine and lacustrine amphibious assaults found in history.1 Considering English riverine/lacustrine operations in the Irish Nine Years’ War (1593–1603, a.k.a. the Tyrone rebellion) and U.S. riverine warfare experiences in the American Civil War and Vietnam War can inform Marine planners as they develop the tactics, techniques, and procedures of the Marine Littoral Regiment.

England conducted amphibious operations in several theaters at the end of the sixteenth century, including several riverine and lacustrine operations executed in Ireland during the Nine Years’ War. Ireland’s riverine and lacustrine nature encouraged an amphibious strategy, and both Irish and English forces adopted tactics to deal with the Irish geography. As historian Mark C. Fissel notes, the result was that English amphibious operations in Ireland were “remarkably and consistently successful in a theater of operations where the English were failing in the prosecution of land warfare.”2 The siege and assault on the Irish castle at Enniskillen provide one example of Irish and English operations among Ireland’s rivers and loughs.3 Operations such as those at Enniskillen help demonstrate why the English eventually succeeded in quelling the rebellious Irish lords.

This article began as an exercise in historical writing from limited primary sources. In this case, a combination of written and visual evidence about the English capture of Enniskillen Castle allows for some detailed analysis of one specific amphibious operation in Ulster early in the Nine Years’ War. The evidence available for that exercise, being from English sources alone, provides an incomplete picture of events. But the compelling nature of the event, its connection to the broader amphibious campaign in Ulster and as an example of inland amphibious warfare, provides a catalyst for discussion of the expanded nature of amphibious operations that might be encountered by a stand-in force such as the modern Marine Littoral Regiment.

Riverine and Lacustrine Warfare

Since land transportation was slow and ineffective at easily carrying large quantities of material until the twentieth century, water transport was the preferred method of moving goods between communities. Seaports situated far inland on bays and rivers supported the transshipment of goods in and out of the hinterlands. Rivers and canals thus served as corridors to the sea, connecting inland communities, resources, and wealth to the international market. These fluvial systems of waterways and seaports supported entire regions, and control of the waterways was often crucial to control those regions. Rivers, lakes, and canals remain a highly efficient mode of transporting large amounts of goods for relatively low cost. These inland waters remain the loci of commerce and civic life. This is especially true in areas with underdeveloped road systems and rail networks. Even in regions with extensive road and rail networks that allow efficient movement of goods over land, waterways remain critical avenues of transport and, therefore, areas vital to military operations in riverine and lacustrine environments.

Inland amphibious warfare, referred to colloquially today as riverine or brown water operations, like its open water cousins, sea control and sea denial, focuses on two essential elements. The first is to preserve freedom of action to use the rivers and lakes as a maneuver space, to project power, and to protect friendly commerce and military traffic along riverine, lacustrine, and coastal waterways. The second is denying the enemy that freedom of action by disrupting their ability to operate in that same terrain. These competing elements present significant challenges due to the often-expansive nature of the fluvial system supporting a given region. Control of seaports alone is insufficient to control a fluvial system since multiple rivers, lakes, and canals feed individual ports. However, seizing critical junctures could disrupt the ability to move goods or troops over the waterways. By identifying these critical points, effective defenses could be erected, or offensive military operations could be focused.

One method of control is to fortify key terrains, such as river junctions, narrow channels, or points through which most traffic must pass. In the British Isles during the Elizabethan period, these fortified positions often took the form of forts or fortified castles erected along the riverbanks and lough shores. Such fortifications became the object of military operations.4

Irish Way of War

The fluvial systems that defined much of northern Ireland consisted of a series of loughs and rivers combined with bogs and wooded corries and drumlins subject to frequent flooding.5 This geography made waterborne movement an effective method of military operations. It also presented critical locations that controlled the flow of commercial and military traffic in the waterways. Traditionally, the Irish fortified these vital points by erecting keeps on islands in the middle of loughs.6

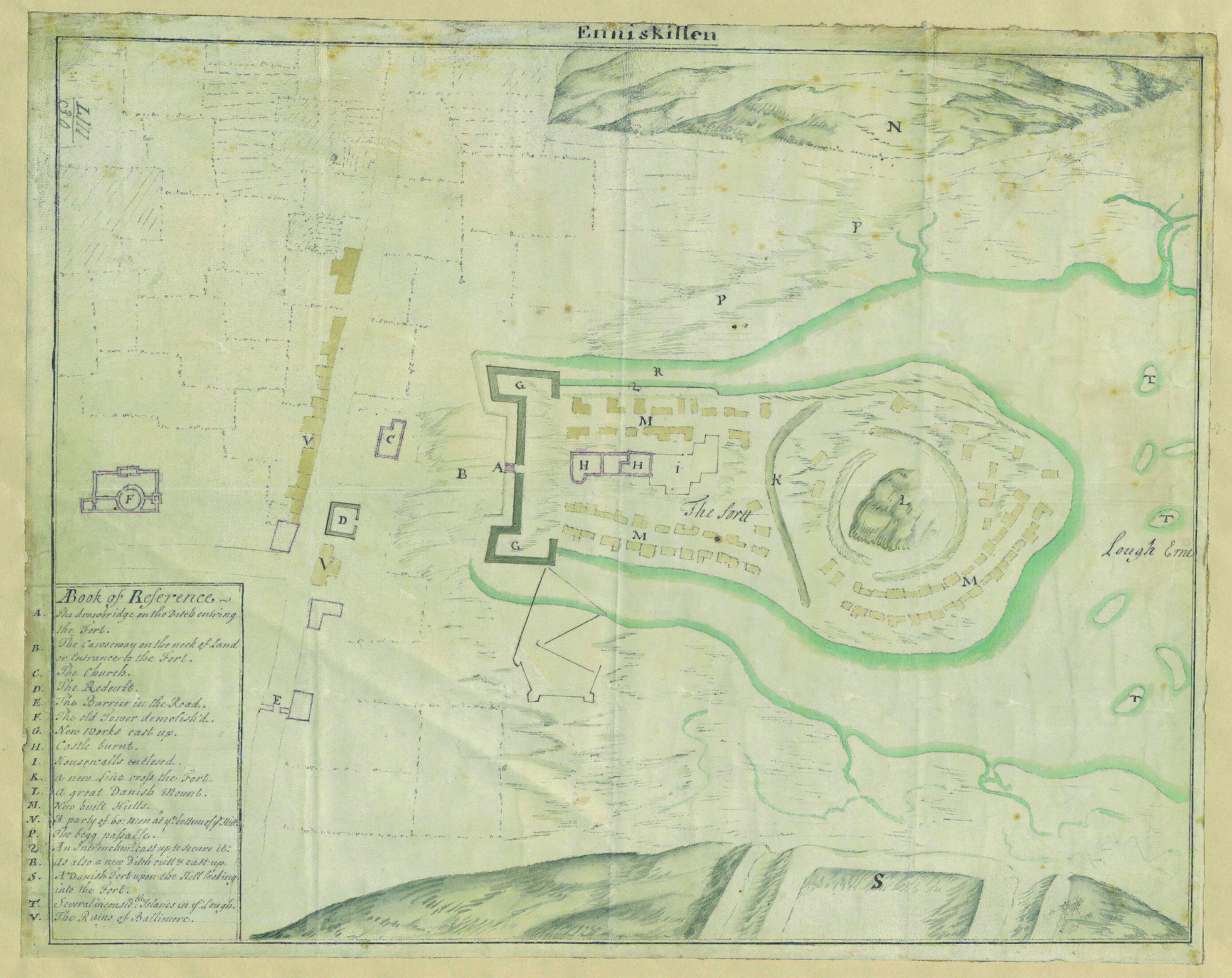

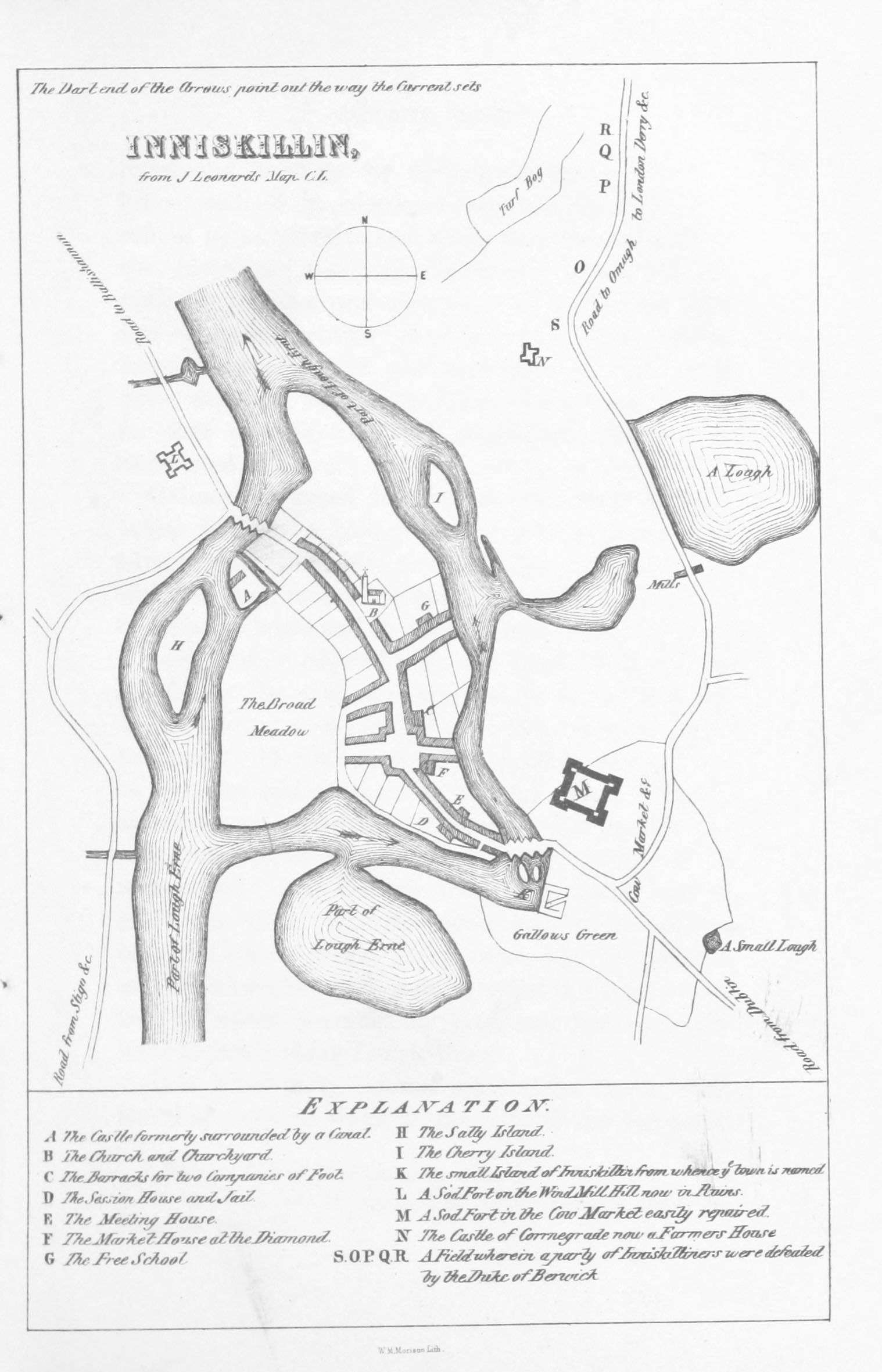

Enniskillen Castle is an example of such a fortification. Built in the early 1400s by Hugh “The Hospitable” Maguire (d. 1428), Enniskillen Castle stood on an island in the River Erne as it flows from Upper to Lower Lough Erne.7 John Thomas’s illustration of the siege of Enniskillen Castle shows it occupying the entirety of its island and positioned on a bend in the river, allowing the castle to command about 270 degrees of river approaches.8

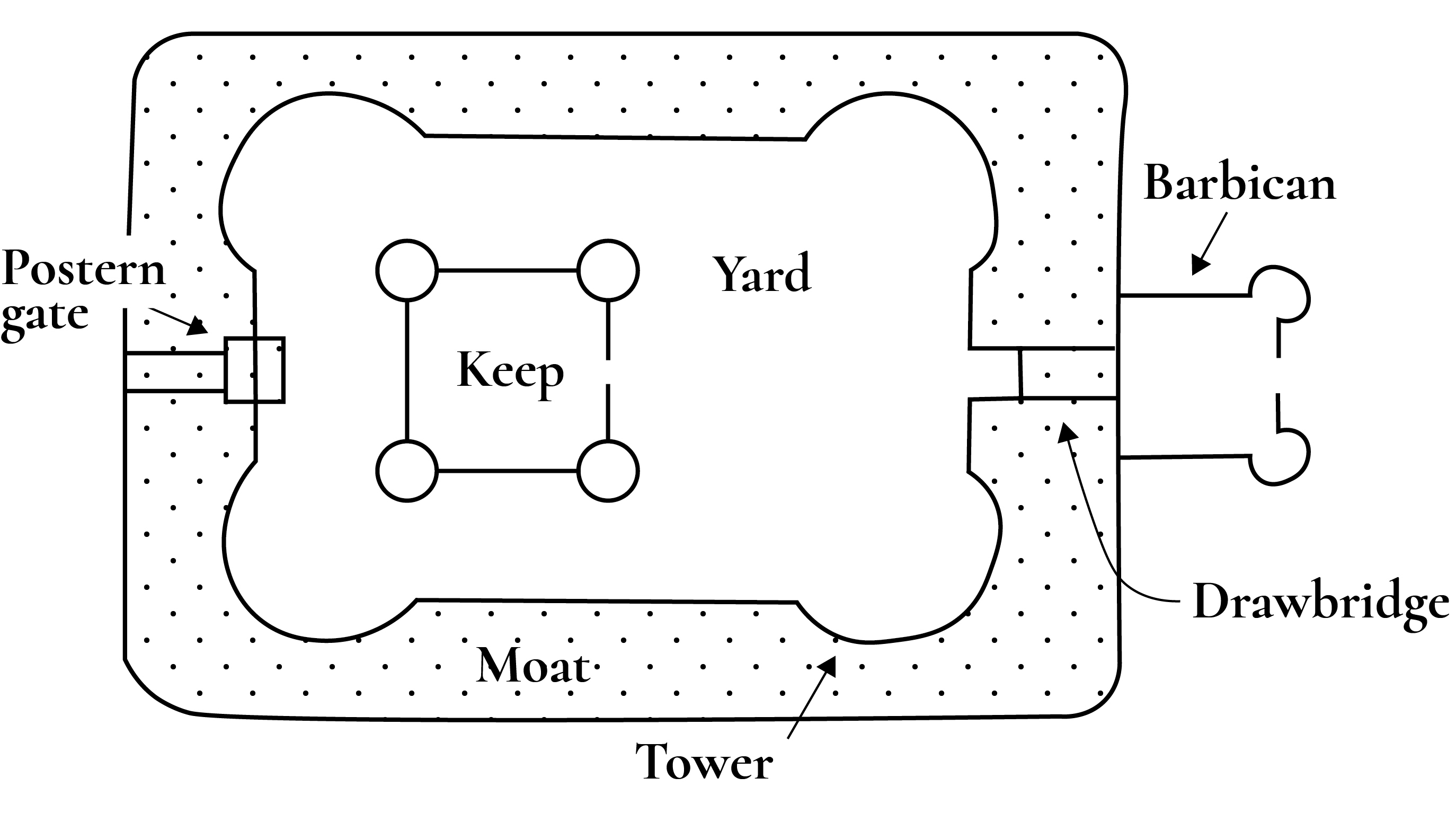

Recognizing the vulnerability of these keeps to amphibious assault, the Irish constructed sconces, or small defensive earthworks, surrounding the keep. They planted sharpened stakes in the water approaches to foul assaulting boats. Irish castles varied in design, but the construction of Enniskillen Castle featured a barbican containing a single landward gate with a bridge across the narrow portion of the river that served as a moat. The castle walls surrounded a central keep that stood four stories tall, capped with a catwalk that provided commanding views in all directions. The height of the keep also allowed for plunging fire on forces attacking the barbican.9

In his book, At the Water’s Edge, Theodore Gatchel describes three basic methods of amphibious defense: the naval defense, defense at the water’s edge, and the mobile land defense.10 Although written to describe twentieth-century amphibious operations, these defense methods also reflect those available to forces in the late 1500s. Lacking a naval force, the naval defense was not an option for the Irish, and the Irish tactic of retreating to their keep removed the prospect of a mobile land defense. This limited the defensive options to defending at the water’s edge and thus inhibited their ability to engage the English amphibious raids where they were most vulnerable, on the water and during disembarkation. Fissel notes in his analysis of the Nine Years’ War that, given Irish specialization in mobile operations, it is amazing that defenders sat in wait instead of going out and disrupting the attack.11

Parts of a typical medieval castle. Adapted by MCUP

English Way of War

English amphibious operations in Ireland during the Nine Years’ War proved significantly more successful than those attempted by the English in their concurrent war against Spain. When the English arrived in Ireland to quell the rebellious lords, they recognized the need for amphibious capability and transformed their transport watercraft into vessels of war. The geography of Ulster, a vital center of the conflict, with its maze of waterways, lent itself to the use of combined land and waterborne operations, in other words, amphibious operations. The frequent inundation of the Irish landscape made land operations problematic and compelled the English to depend on riverine and lacustrine transportation. Control of the river routes was essential to subjugating the region and, by extension, the whole of Ireland.12

Captain Sir John Dowdall (ca. 1545–ca. 1608) pioneered Hibernian amphibious operations, and his assault on Enniskillen Castle demonstrated the amphibious tactics adopted by the English. Those tactics focused on firepower and mobility, including the use of light, shallow draft cots, and longboats.13 One key element to English success was adapting material, both indigenous and already in hand, to the local geography. The English adopted the longboats carried by English seagoing vessels for use in Ireland. Frequently employed as landing boats from larger sailing ships, eight or ten oarsmen rowed the longboat, which had good seakeeping qualities that allowed it to operate in the surf zone. Cots were indigenous flat-bottom boats explicitly developed for the loughs and rivers in Ireland.14 Operations on Irish rivers required oared vessels to maneuver in the many twists, turns, and hilly terrain, as wind power was unreliable. The boats also carried a medium-caliber swivel gun in the bows, which allowed the English to bring firepower to bear on the Irish castles from their less-defended watersides.15 It is, however, important to note that larger caliber artillery available to the English was not fielded at Enniskillen due to the limited carrying capacity of the boats available, a potential limitation to inland amphibious operations conducted in the modern era as well.16

Modern Riverine Warfare

Amphibious operations in a riverine environment remain relevant today. But the U.S. military “is not adequately prepared to use rivers as a maneuver space—or prevent adversaries from doing the same—and it has not been for years.”17 This is despite several examples of riverine warfare in America’s past.

The primary examples of American riverine war began as ad hoc operations, adapting existing equipment, just as the English did for the operations around Enniskillen Castle. During the American Civil War, Union forces in the western theater and the Chesapeake basin adapted local warcraft for use as transports and gunfire support vessels to use the rivers as maneuver spaces. In the west, General Ulysses S. Grant used his riverine forces to bypass, outflank, or surround Confederate strongholds. In the east, Union forces used the rivers that penetrate inland from the Chesapeake Bay to rapidly move forces toward Richmond, Virginia, provide fire support to troops battling along the peninsulas, and resupply ground forces. They also used the rivers to evacuate troops, an all-too-frequent occurrence in these peninsular campaigns. Using rivers as a maneuver space proved critical to Union victories in the west. While less conclusive in the east, the rivers provided critical logistical avenues for Union forces, especially in Grant’s final campaign.

A century later, during the Vietnam War, the Navy and Marines again adapted existing equipment to the riverine fight. Riverine operations combined swift patrol boats, plodding fortified landing craft, and fast-moving light attack helicopters to engage the National Liberation Front/People’s Liberation Army in the expansive river deltas of southern Vietnam. While primarily a Navy mission and often conducted from the water alone, Marines provided the land component for the more complex operations when needed to control key terrain along the rivers. While heroic, the riverine operations of the Vietnam War were inconclusive and, like the English seizure of Enniskillen centuries before, ultimately contributed little to the war’s eventual outcome.

The U.S. Navy maintains a limited riverine capability in the Navy Expeditionary Combat Command (NECC). Much of the contemporary iteration of this Navy mission evolved during the Marine Corps’ focus on counterinsurgency operations, throughout which time the Corps abandoned riverine operations. But the Navy’s capability lacks the robust land component required to expand and exploit control of the rivers and lakes by seizing and controlling the adjacent key terrain. Additionally, in the past few years, the Navy has reduced its riverine capability, citing its lack of relevance as the Navy reshapes its force to counter threats from Russia and the People’s Republic of China—the very threats that the Corps’ expeditionary advanced base operations are designed to address.18

The Siege of Enniskillen Castle

Hugh Maguire (d. 1600) led some of the forces in the Irish rebellion and controlled a major avenue (the Erne) in Ulster with the castle Enniskillen, built by his ancestor Hugh the Hospitable. As long as Maguire held this chokepoint on the Erne, he stymied the English ability to subdue Ulster. In the summer of 1593, the lord deputy in Dublin offered Maguire protection for two months if he would disband his forces and lay down his arms. Maguire countered with a request for six months of protection and stipulated the discharge of Sir Richard Bingham’s troops as well, thinking that Bingham’s troops were forming to invade his lands. The lord deputy, doubting Maguire’s motives, dismissed this request, noting “the Council and I dare not give order to discharge the soldiers until we know what will become of this traitor Maguire.”19 Unwilling to deal with Maguire and his “traitorous” band, the English determined that he must be defeated militarily. On 11 October 1593, English forces under Sir Henry Bagenall (ca. 1556–98) scored “a splendid victory over Maguire’s full strength, being 1,000 foot and 160 horse, 300 slain . . . near the Ford of Golune.”20 Maguire’s defeated force retreated to his fortified castle at Enniskillen, where they awaited the English assault.

Ensconced in Enniskillen Castle, Maguire’s men must have felt secure from English attack. Situated as it was, the castle provided commanding views of the approaches in all directions. The castle walls abutted the river on two and a half sides, with a narrow channel of the river forming a moat on the remaining sides, making a land approach relatively confined and easily defended. The land approach to the castle was also an island, providing an additional barrier for attackers to cross. To enhance the defensive barrier provided by the island, the castle builders had placed sconces at the entrances to the section of the river that had to be crossed, blocking river access to the island. Complementing the sconces were stakes planted in the river approaches to the castle designed to foul any boats attempting to pass.21 The castle consisted of an outer wall surrounding a tower keep—a tall, sturdy structure with loopholes for firing on attacking forces. A tower and a narrow bridge that canalized an attacking force protected the single land gate. Atop the wall was a protected catwalk from which defenders could fire down on attacking troops and quickly reposition within the castle’s defenses.22

Enniskillen, 1690, map on vellum. This map shows the motte and bailey mound on the peninsula and the new works about the castle, hills above and below, with Lough Erne to the right. Includes a key to the lower left within a cartouche. Map of Enniskillen, ID 004982433, King’s Topographical Collection, George III, King of Great Britain, former owner. Enniskillen, 1690, British Library Board

Captain John Dowdall’s troops arrived outside Enniskillen Castle in early January 1594. With accounts of Maguire’s strength running from less than 50 to more than 500 troops, Dowdall had to plan his attack carefully to ensure victory. Rather than storm the castle immediately, Dowdall worked to position his force and harass Maguire’s supply lines. In a letter to the lord deputy in Dublin, Dowdall reported that he “took 700 cows from the traitor” on 18 January. Thinking Dowdall’s troops were his own, Maguire came out in a cot to investigate, and the English troops fired on the cot, killing two men. Dowdall followed this with an assault on one of the sconces defending the castle, putting “the defenders to the sword, and burned the same.”23

To ensure sufficient forces to take Enniskillen Castle, Dowdall had requested reinforcements from Bingham. These forces arrived during the next few days and were employed in besieging the castle. By 25 January, the English had “entrenched and placed our shot within one caliver shot of the Castle, and the same night we placed our three [falconets].”24 Drawings of the siege indicate that these entrenchments laid down fire on the castle from two directions. Two positions placed across the River Erne, west of the castle, under the command of Captain Bingham, took the castle under fire with muskets, a falconet cannon, and a robinet cannon.25 None of these weapons could penetrate the castle’s thick walls, but their fire kept the Irish defenders behind their defenses. Additionally, based on their position relative to the castle entrance, the English could fire into the flank of any force that ventured out of the castle against them.

Enniskillen, map. ID 015115593, Robert Cane, The History of the Williamite and Jacobite Wars in Ireland; from Their Origin to the Capture of Athlone. [With Plates and Maps.] (1859), 137, British Library Board

Amphibious operations on 24 January by Dowdall’s forces facilitated the placement of English entrenchments on the island adjacent to the castle. English troops passed the castle in the river and were forced, by sconces and stakes that hindered further passage of their boats, to put men ashore to defeat these defenses. Defeating the sconces allowed the English to advance, using a sowe to shield them from musket fire from the castle, and to place the three falconet cannons mentioned in Dowdall’s report and additional musketeers in entrenchments south of the castle, directly across from the castle gate.26

The castle’s defenders returned musket fire at both entrenchments but likely lacked cannons in the castle for heavier fire against the attackers. Thirty-six men defended the castle, and 30 or 40 women or children were holed up within its walls.27 The defenders had retreated into the castle when Dowdall’s force overran the sconces on the island’s eastern end adjacent to the castle earlier in the assault. Curiously, the defenders left intact the bridge to the castle gate, depending on the gate’s sturdy door for defense against a breach of the barbican.28

The siege of Enniskillen Castle lasted nine days before Dowdall launched his assault from the Erne on 2 February 1594. The assault consisted of three vessels: a “greate boate” carried the breaching force, and two cots provided a scaling party. Twelve oarsmen powered the greate boate, covered with hurdells and hides to protect the 100 men inside.29 The two cots, each rowed by 8 oarsmen, carried 15 troops with a scaling ladder in the stern and were armed with a swivel gun in the bow. The assault force, under cover of the musket and cannon fire of the English entrenchments “assault[ed] the castle by boats, by engines, by sap, and by scaling,” with the greate boate laying alongside the western barbican and the two cots scaling the southern barbican.30 To save himself from hanging, Connor O’Cassidy, Maguire’s messenger whom the English had captured, served as a guide to Dowdall’s assault force and helped the English place their assault craft in the best position to breach the barbican. The men of the greate boate breached the castle wall using “pickaxes and other instruments.”31 Once the wall was breached, Maguire’s defenders retreated into the keep where, according to O’Cassidy, they were forced to surrender under threat of being blown up by powder.32

With Enniskillen Castle now in the hands of the crown, Dowdall garrisoned it with 30 men, 10 from each company present, and set to “ransacking all [Maguire’s] sconces in their loughs and islands wheresoever.”33 While losses during the siege and assault were minimal on both sides, Dowdall’s forces slaughtered the Irish occupants of the castle, and sickness soon reduced the English ranks to one-half their original strength. Thus, despite successfully taking Enniskillen in the siege, Dowdall withdrew the majority of his garrison, leaving only 100 men to maintain a hold on the castle and surrounding areas.

Unfortunately for the English, the capture of Enniskillen did not end the rebellion in Ulster. Within six months, the garrison was besieged by Maguire’s forces, prompting Sir Henry Duke and Sir Edward Herbert to mount a relief expedition to the castle in August 1594. This English expedition was defeated at the Battle of the Ford of the Biscuits, but the garrison at Enniskillen held until relieved by another expedition later that summer.34 Strategically, the capture of Enniskillen may have been of little consequence. Still, its seizure demonstrates how the effective use of inland amphibious warfare can achieve military objectives in riverine and lacustrine environments.

Trim Castle, County Meath, Ireland, provides an example of a medieval castle barbican (right) and keep (center). Photo courtesy of the author

Lessons for the Modern Marine Corps

Considering English riverine operations in the Nine Years’ War, such as the siege of Enniskillen Castle, in addition to the American river warfare experiences in the American Civil War and Vietnam War, can inform Marine planners as they develop the tactics, techniques, and procedures of the Marine Littoral Regiment (MLR). It may be difficult to see lessons for today’s Marine Corps from a sixteenth-century assault on a river-island castle. Technology has clearly advanced from the falconets, cots, greate boates, and scaling ladders employed by the English in their assault on Enniskillen Castle. But lessons abound as the Marine Corps seeks to reinvent itself as a stand-in force for the twenty-first century.

The first thing to note is the pervasiveness of rivers and lakes that crisscross the land of the littorals where the Marine Corps intends to operate, such as the islands of the Philippine archipelago or the littorals of Southeast Asia. Movement of traditional infantry or other ground forces is constrained in riverine, lacustrine, and archipelagic regions as small amounts of land are interspersed with rivers, marshes, lakes, and other water features. If the Marines wish to be a stand-in force in the western Pacific and Southeast Asia littorals, they will need to be able to operate seamlessly across the inland land-water interface.

English operations at Enniskillen demonstrated the value of coordinated waterborne and land-based forces—not on the grand scale of a World War II D-Day style invasion, but at the tactical level. Having the flexibility to envelop—on land and on the water—the castle prevented the defenders from concentrating on one threat vector. Coordinated operations across both land and water after the arrival of the landing force provided the English commander with the flexibility to control the tempo of the assault.

The advent of airpower, including vertical lift and aerial assault capability, may cause some to argue that the inland land-water interface is no longer pertinent. We can put Marines in helicopters or tilt-rotor aircraft, and they can bypass the land-water interface and go straight to the objective. That may be true, but it is not always an option, especially when the MLR operates as a stand-in force in an air-denied environment. The modern Marine commander needs options, so restoring and expanding a riverine capability to the Marine Corps, specifically in the MLR, is essential to providing flexibility to our Marines. As a stand-in force, the MLR must be able to operate across all domains in the littorals—including the land-water interface.

Conclusion

During the Nine Years’ War, English operations in Ireland were the most effective English amphibious operations of the era. This effectiveness resulted from several factors, including the geography of Ireland, the early recognition by the English that amphibious operations were necessary, the Irish tendency to eschew an active defensive position and instead hole up in their fortified keeps, and the English use of mobility and firepower to overwhelm the Irish defenses. Most critical of these were the riverine and lacustrine features of Ireland. Pioneers in Hibernian amphibious operations such as Captain Dowdall recognized the ineffectiveness of land operations in this environment and adopted tactics to take advantage of the mobility provided by the waterways. Dowdall’s combined operations to invest, besiege, and then take Enniskillen Castle by an assault from the river exemplify these operations. Identifying and overcoming the Irish defensive structures like sconces and water obstacles meant to impede boat movement, the English were then able to lay siege and storm the weakened castles and eventually quell the rebellious lords of Ireland.

Dowdall adjusted his tactics to the geography in which he fought, and he adapted the tools at his disposal to take advantage of that geography. Today’s Marine commanders should take their cue from Dowdall in understanding the riverine and lacustrine operating environment and be prepared to adapt their tactics to match the environment. Adapting to the operating environment is not a new idea. But considering examples such as the siege at Enniskillen Castle allows commanders to equip MLRs with the tools to operate in the riverine and lacustrine environments that permeate the western Pacific littorals in advance of need. However, MLR commanders should also be prepared to adapt indigenous tools, often designed over centuries to operate in the local environment, to maximize MLR effectiveness in the riverine and lacustrine settings they can expect to face.

•1775•

Endnotes

- Lacustrine: related to or associated with lakes.

- Mark C. Fissel, “English Amphibious Warfare, 1587–1656: Galleons, Galleys, Longboats and Cots,” in Amphibious Warfare, 1000–1700: Commerce, State Formation and European Expansion, ed. D. J. B. Trim and Mark Fissel (Leiden, NL: Brill, 2006), 218.

- Lough: lake (Ireland).

- D. J. B. Trim, “Medieval and Early-Modern Inshore, Estuarine, Riverine and Lacustrine Warfare,” in Amphibious Warfare, 1000–1700, 360–63.

- Corries: horseshoe-shaped vallies formed through erosion by ice or glaciers; drumlin: a hill made of glacial till deposited by a moving glacier, usually shaped like half an egg.

- Fissel, “English Amphibious Warfare, 1587–1656,” 235.

- John Thomas, “Siege of Enniskillen Castle, 1594,” color illustration, C13343-69, Cotton Augustus I.ii.39, British Library Board; and Paul Logue, “Siege of Enniskillen Castle Map, 1594,” PDF, Fermanagh, A Story in 100 Objects, Fermanagh County Museum, 1, accessed 25 September 2016.

- Thomas, “Siege of Enniskillen Castle, 1594.”

- Thomas, “Siege of Enniskillen Castle, 1594.”

- Theodore L. Gatchel, At the Water’s Edge: Defending Against the Modern Amphibious Assault (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 1996), 2–3.

- Fissel, “English Amphibious Warfare, 1587–1656,” 235.

- Fissel, “English Amphibious Warfare, 1587–1656,” 233.

- Fissel, “English Amphibious Warfare, 1587–1656,” 218, 233–36; and Hans C. Hamilton, ed., Calendar of the State Papers, Relating to Ireland, of the Reigns of Henry VIII, Edward VI, Mary, and Elizabeth, vol. 5, October 1592 to June 1596 (London: Eyre and Spottiswoode, 1890), 210.

- “Traditional Boats and Replicas,” Irish Waterways History, accessed 5 April 2022.

- Fissel, “English Amphibious Warfare, 1587–1656,” 234.

- Fissel, “English Amphibious Warfare, 1587–1656,” 236.

- Walker Mills, “More than ‘Wet Gap Crossings’: Riverine Capabilities Are Needed for Irregular Warfare and Beyond,” Modern War Institute, 9 February 2023.

- Richard R. Burgess, “The Navy’s Shrinking Patrol Boat Force,” Seapower, 2 June 2021.

- Hamilton, Calendar of the State Papers, Relating to Ireland, of the Reigns of Henry VIII, Edward VI, Mary, and Elizabeth, 127–28.

- Hamilton, Calendar of the State Papers, Relating to Ireland, of the Reigns of Henry VIII, Edward VI, Mary, and Elizabeth, 166–67.

- Fissel, “English Amphibious Warfare, 1587–1656,” 235.

- Thomas, “Siege of Enniskillen Castle, 1594.”

- Hamilton, Calendar of the State Papers, Relating to Ireland, of the Reigns of Henry VIII, Edward VI, Mary, and Elizabeth, 199–203, 204.

- The caliver is halfway between a musket and an arquebus and has a higher bore and heavier barrel than the arquebus, but is otherwise identical in design. A falconet was a light cannon that fired a one-pound ball about 5,000 yards. Hamilton, Calendar of the State Papers, Relating to Ireland, of the Reigns of Henry VIII, Edward VI, Mary, and Elizabeth, 204.

- A robinet was a light cannon that fired a three-quarter pound shot with a range of approximately 2,000 yards. Thomas, “Siege of Enniskillen Castle, 1594.”

- A sowe is a siege engine used to protect assaulting forces. Thomas, “Siege of Enniskillen Castle, 1594.”

- Thomas, “Siege of Enniskillen Castle, 1594”; and Hamilton, Calendar of the State Papers, Relating to Ireland, of the Reigns of Henry VIII, Edward VI, Mary, and Elizabeth, 210.

- Logue, “Siege of Enniskillen Castle Map,” 6; and Thomas, “Siege of Enniskillen Castle, 1594.”

- A hurdell (or hurdle) during this period was a light section of fencing used for temporary barriers, for crossing rivers, and, in this case, as light armor against projectile weapons.

- Hamilton, Calendar of the State Papers, Relating to Ireland, of the Reigns of Henry VIII, Edward VI, Mary, and Elizabeth, 204–10; and Thomas, “Siege of Enniskillen Castle, 1594.”

- Hamilton, Calendar of the State Papers, Relating to Ireland, of the Reigns of Henry VIII, Edward VI, Mary, and Elizabeth, 210; and Thomas, “Siege of Enniskillen Castle, 1594.”

- Hamilton, Calendar of the State Papers, Relating to Ireland, of the Reigns of Henry VIII, Edward VI, Mary, and Elizabeth, 210.

- Hamilton, Calendar of the State Papers, Relating to Ireland, of the Reigns of Henry VIII, Edward VI, Mary, and Elizabeth, 208.

- James O’Neill, “Death in the Lakelands: Tyrone’s Proxy War, 1593–4,” History Ireland 23, no. 2 (March/April 2015): 14–17.