PRINTER FRIENDLY PDF

EPUB

One of the unsung stories of the Vietnam War is of the Combined Action Platoon (CAP) program, born of battlefield necessity by the U.S. Marine Corps. It was one of the most effective and least costly initiatives to come of that unhappy war. The CAP program was the brainchild of a Marine battalion commander in 1965 as a way to improve security in villages in the area of tactical responsibility not far from Hue, a former royal capital of central Vietnam. The concept was to combine a 13-person rifle squad of Marines (including a Navy corpsman) with a platoon of South Vietnamese village defense militia, the Popular Forces (PF). These comprised villagers too young (or too old) to be drafted into the Army of the Republic of Vietnam (ARVN). They were poorly armed and poorly trained and as a result were marginally effective. That changed when they teamed up with the Marines.

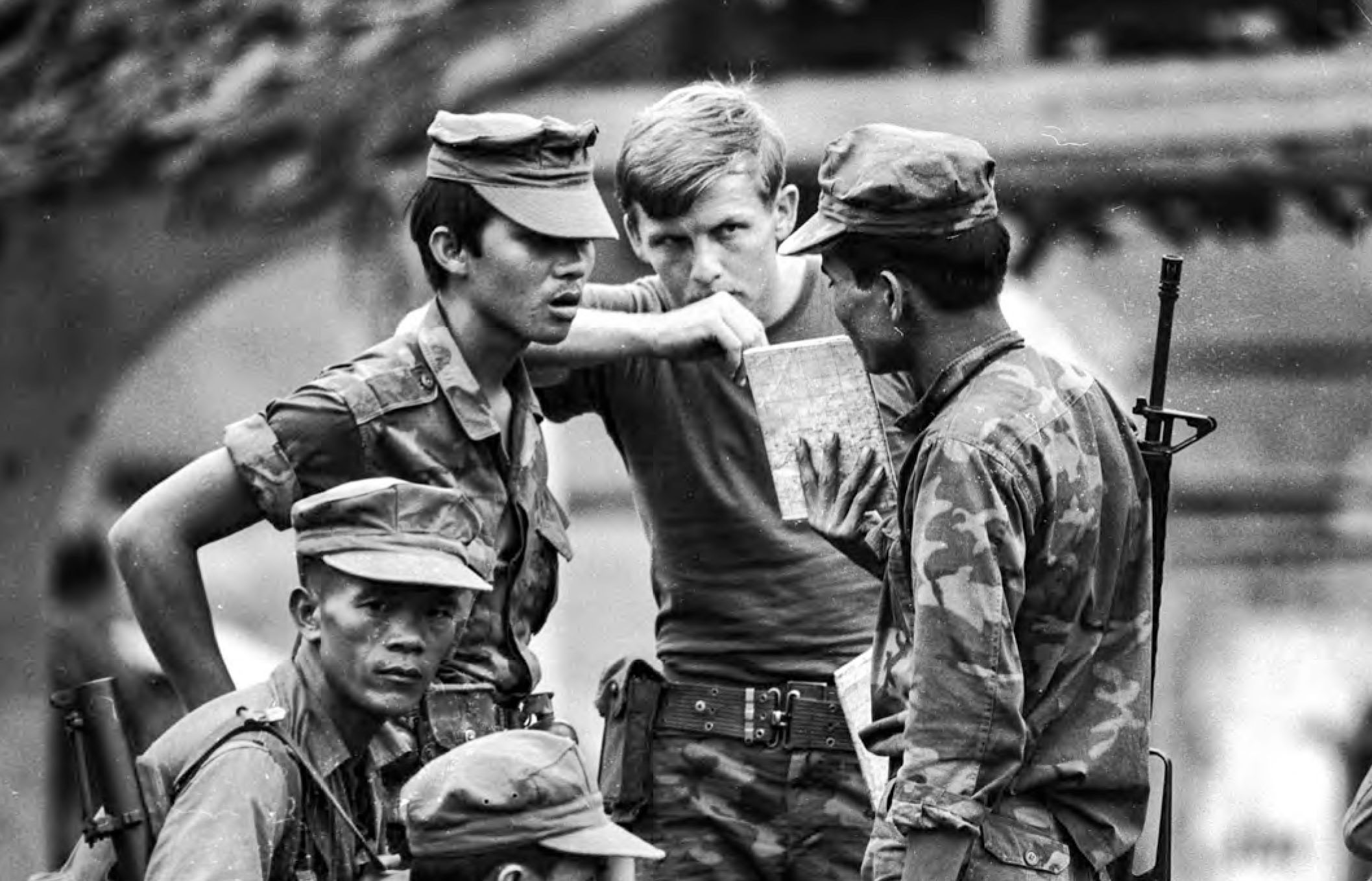

Marine Civil Affairs officer, 1stLt Barry Broman (right) talking with a CAP Marine sergeant in a village near Da Nang, Republic of Vietnam, in 1969. Photo by Maj Barry Broman, USMCR (Ret)

A CAP Marine conducts weapons training with South Vietnamese Popular Forces. Photo by Maj Barry Broman, USMCR (Ret)

A CAP Marine chats with Popular Forces buddies while off duty. Photo by Maj Barry Broman, USMCR (Ret)

While I never served as a CAP Marine, I did work with them when I was a G-5 Civil Affairs officer in 1969 with the 1st Marine Division. Before that, when still in the bush, I was on one operation with PFs when I was the executive officer of Company H, 5th Marine Regiment, on an operation in the Que Son Mountains southwest of Da Nang. Company H helped defend a hilltop manned by a platoon of PFs under the command of an old sergeant who had served in the colonial French Army a generation before. I spoke with him in French. Together, we gave the North Vietnamese Army (NVA) a nasty surprise when they attacked our position and came away with greater respect for the PFs and the impression that when properly led and armed, they could fight.

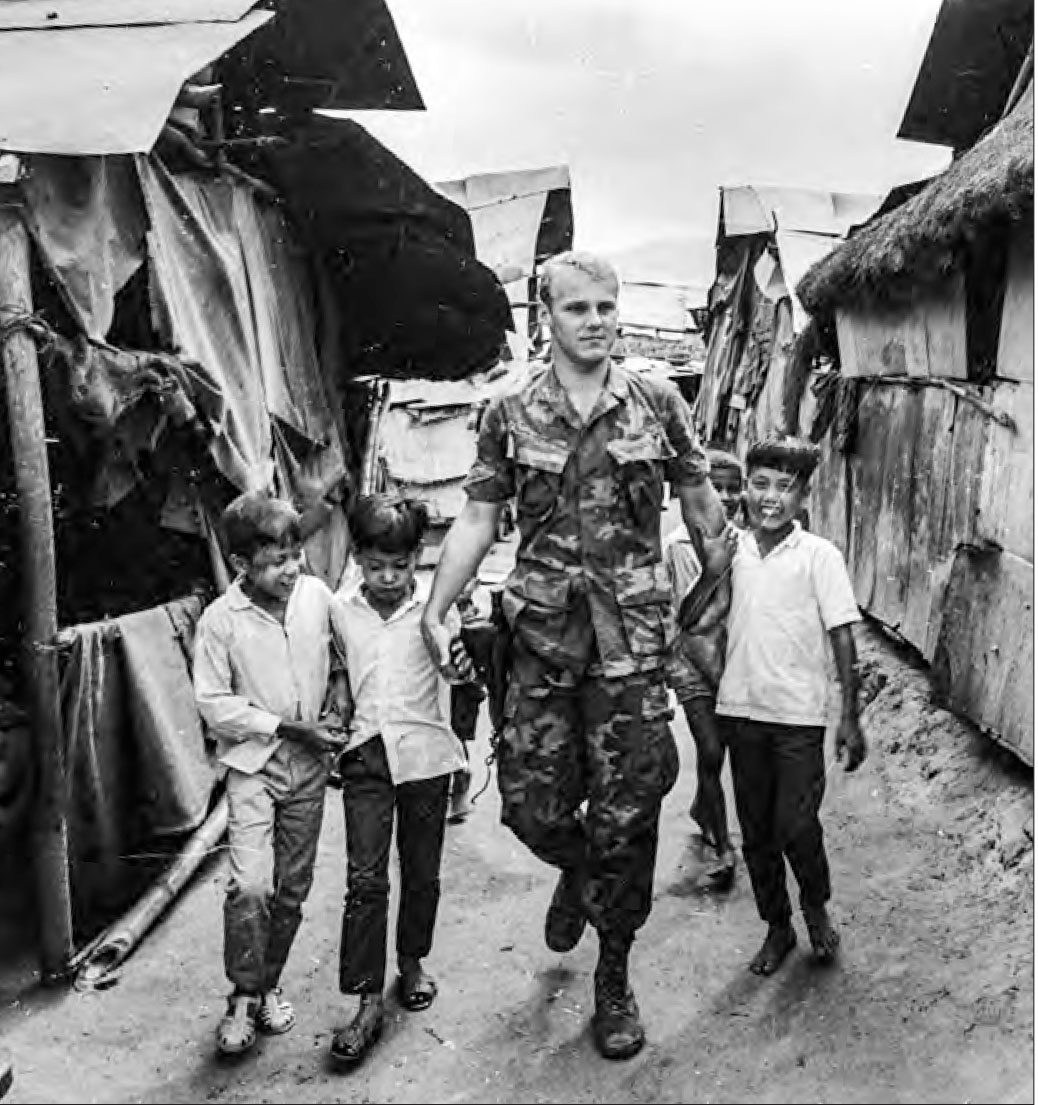

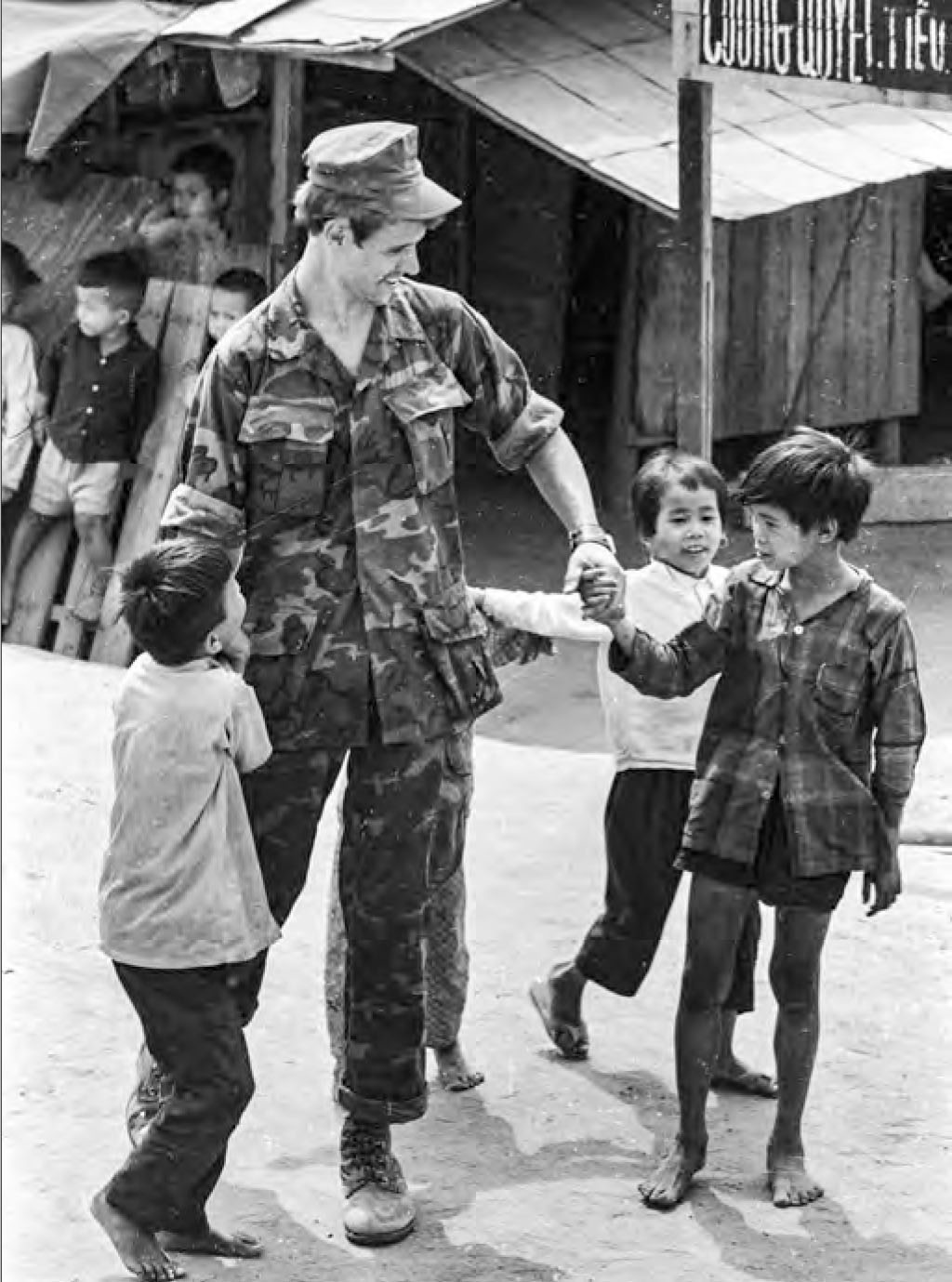

A CAP Marine with village buddies. Photo by Maj Barry Broman, USMCR (Ret)

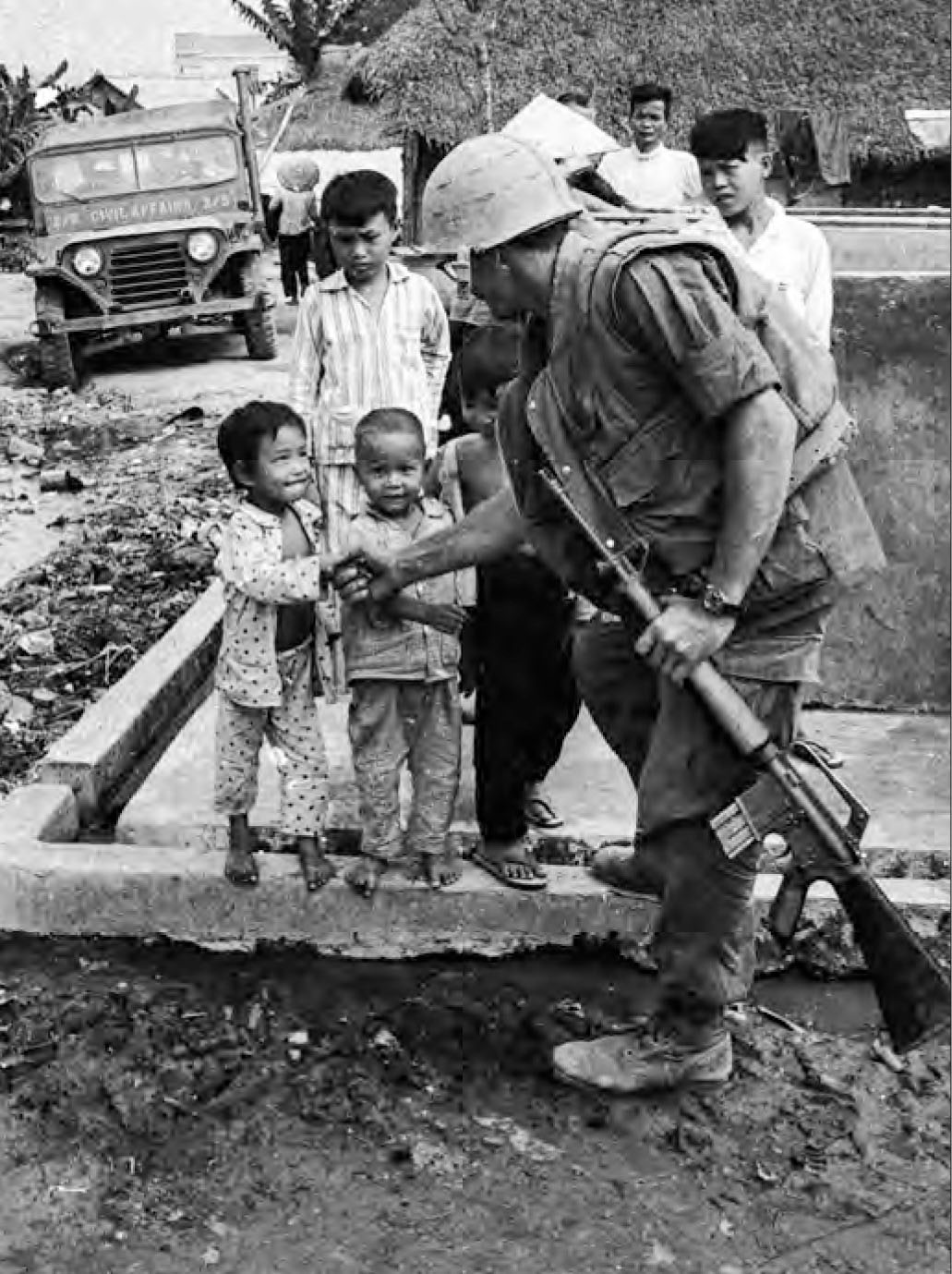

Navy corpsman attached to the CAP unit providing medical attention to village children. Photo by Maj Barry Broman, USMCR (Ret)

A CAP Marine working with Popular Forces militiaman.Photo by Maj Barry Broman, USMCR (Ret)

Early efforts worked well when Lieutenant Colonel William L. Taylor, commanding officer of the 3d Battalion of the 4th Marine Regiment, assigned Marines to work with PFs in six villages around the airfield at Phu Bai, not far from Hue in central Vietnam. The idea gained traction when it came to the attention of Major General Lewis W. Walt, a veteran of the Banana Wars in the Caribbean, where Marines worked effectively with security forces at the lowest levels in Nicaragua, Haiti, and the Dominican Republic. That experience in working closely with local populations was unique to the Marine Corps. General Walt immediately saw the value in putting combat Marines together with PFs, and the program grew in size, mission, and success.

After seven months with the 5th Marines, I was assigned to G-5, civil affairs, at 1st Marine Division Headquarters near Da Nang. Among other duties, I was named the division personal response officer. The mission was to get Marines to get along with our South Vietnamese allies and especially the civilians in areas where Marines were operating. The mission of Marines was to kill NVA soldiers and their Viet Cong allies. Most of our casualties came from booby traps, often placed by civilians sympathetic to the Viet Cong or forced to help them. This bred distrust and dislike of the civilians by Marines. At that time, the division was losing one Marine leg a day to booby traps. The village kid you gave chow to this morning might be setting booby traps tonight.

A CAP sergeant and his little friends. Photo by Maj Barry Broman, USMCR (Ret)

A CAP Marine with Popular Forces during weapons training. Photo by Maj Barry Broman, USMCR (Ret)

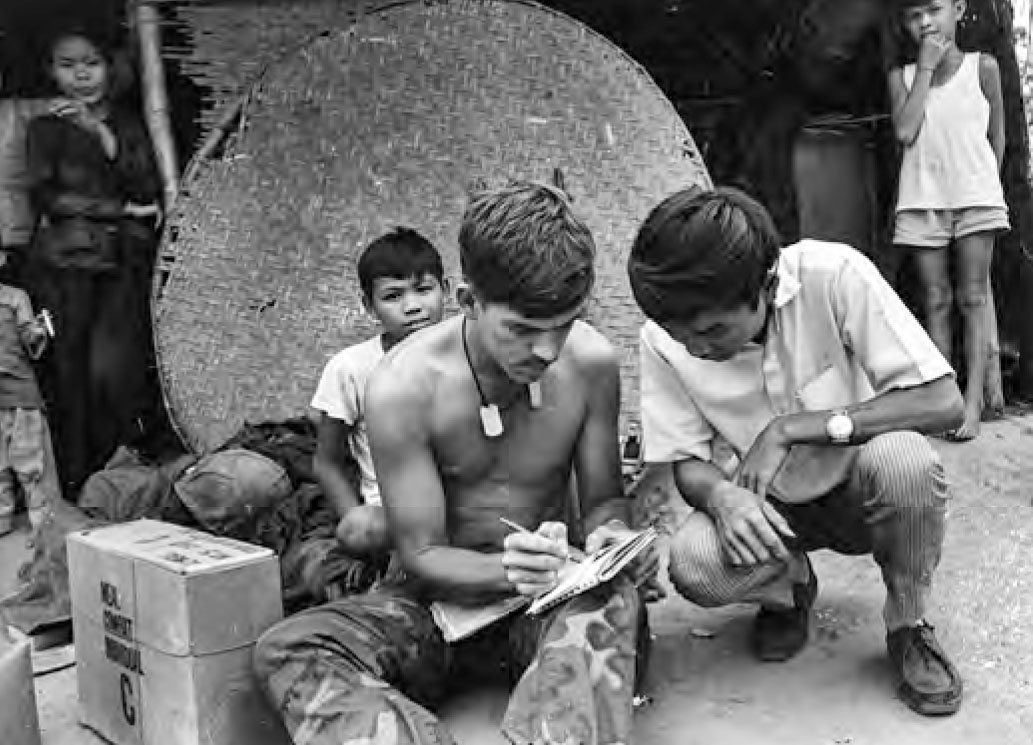

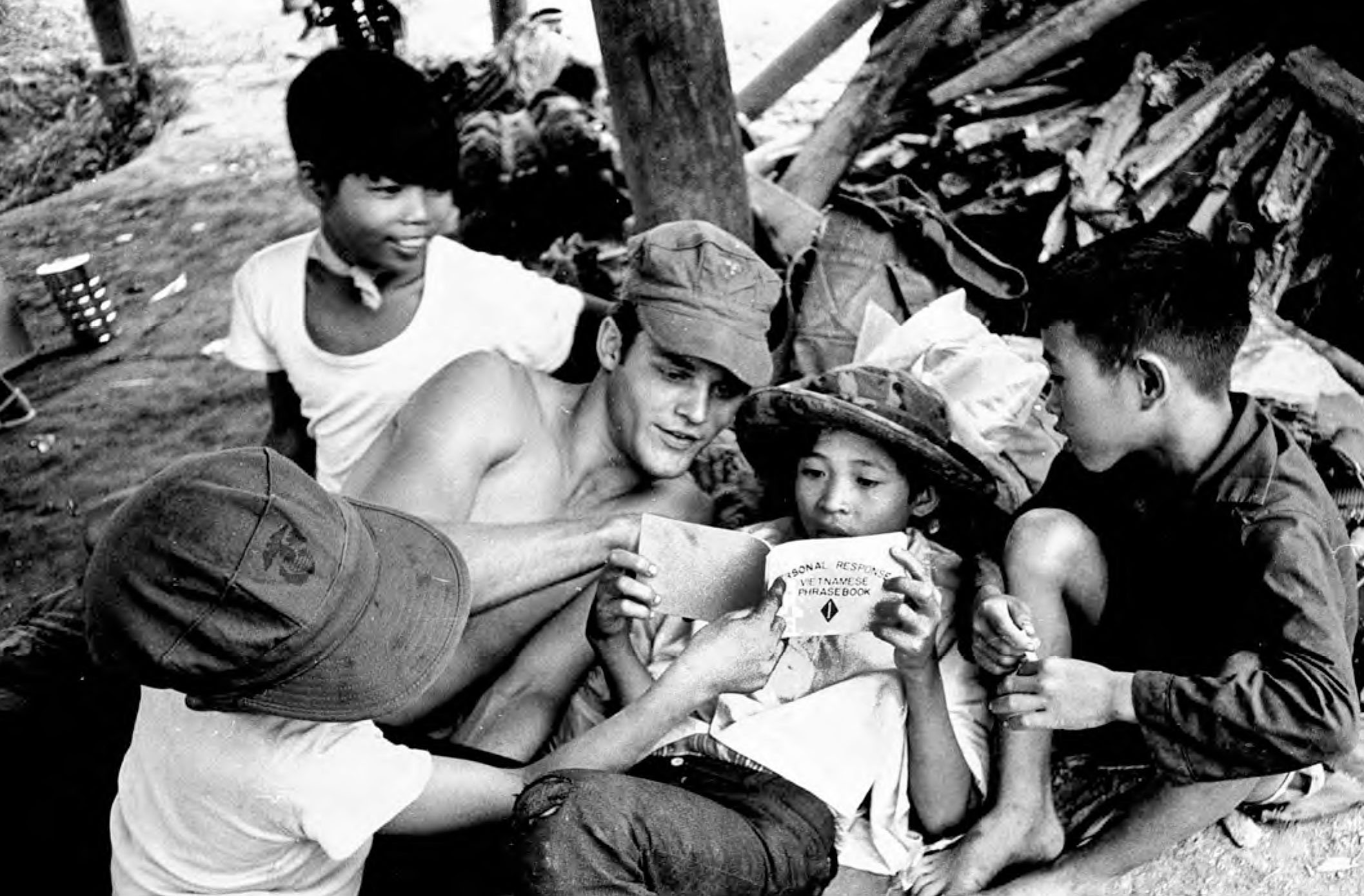

A CAP Marine reading the 1st Marine Division G-5, Personal Response, Vietnamese-English phrase book with village children. Photo by Maj Barry Broman, USMCR (Ret)

Corpsman tending village children. Photo by Maj Barry Broman, USMCR (Ret)

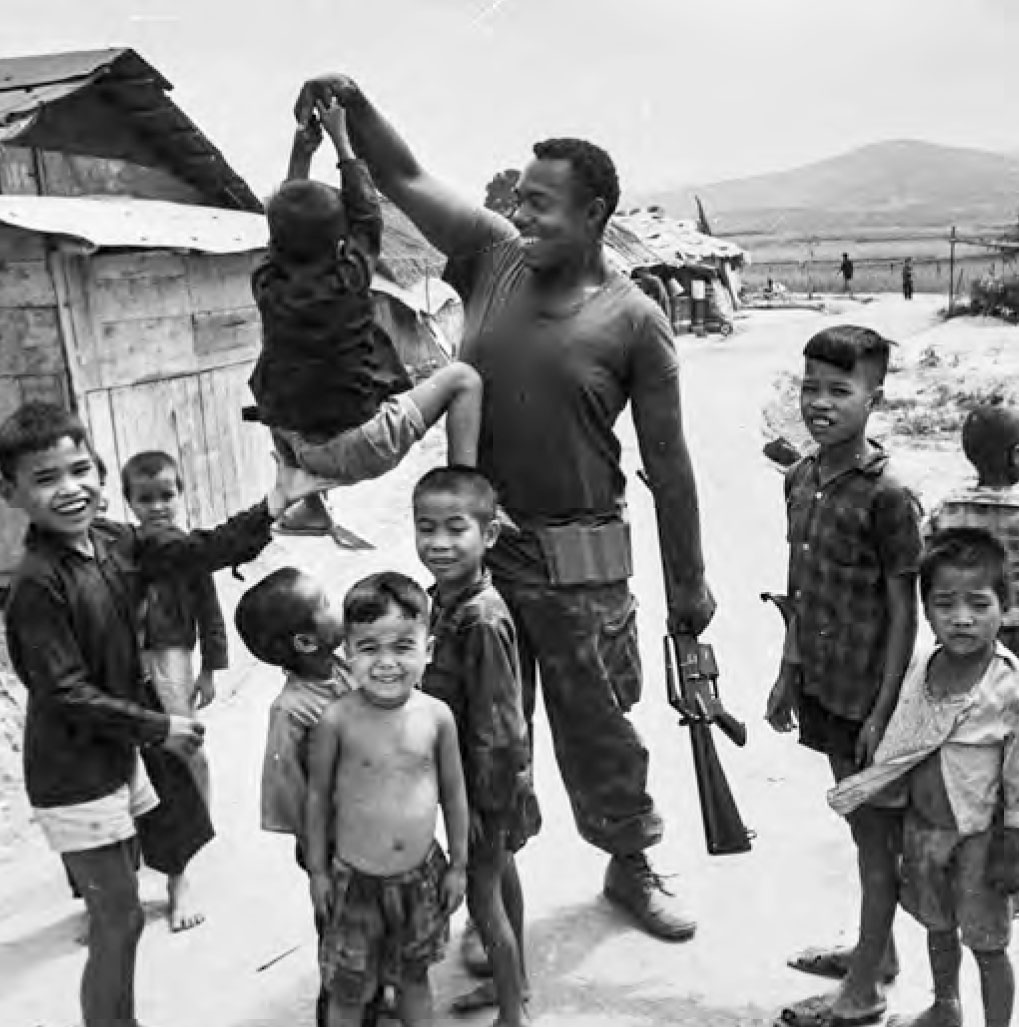

A CAP Marine playing with village kids, his M16 unloaded but ready. Photo by Maj Barry Broman, USMCR (Ret)

The one program that put Marines in direct support of villagers was the CAP program, and I worked in support of them as part of my G-5 duties. The CAP Marines were an inspiration and focus of my efforts to change Marine attitudes. I wished that the CAP program was larger and put more Marines in contact with Vietnamese to improve their security while building the mutual trust that is needed for success.

I visited CAP villages along Highway 1, Vietnam’s main north-south highway in my jeep with Sergeant Ray Bennett at the wheel. The company was commanded by Captain Gary E. Brown, with whom I had served as his executive officer a few months earlier. Brown, later a brigadier general, gave us a tour of the scattered men under his command in villages along the critical highway. In mid-1969 the area was pretty much secure from large enemy units. We saw Marines instructing their young Vietnamese buddies how to care for and operate their small arms weapons. Each CAP had a Navy corpsman (always known as “Doc”) who ran medical civic action programs (MEDCAPs) for civilian Vietnamese from their village, often the only medical professional in the area.

I was particularly taken with the performance of the Marine sergeant in charge of a CAP unit south of Da Nang. With only rudimentary Vietnamese, aided by the use of a Vietnamese-English dictionary I produced as one of my civic action duties, the young man was mature beyond his years and was impressive in his understanding and respect for Vietnamese culture and ways. He worked very closely with the elderly village chief in explaining what he was doing and what he needed. They were an effective team.

A CAP Marine making friends. Photo by Maj Barry Broman, USMCR (Ret)

A CAP Marine going on patrol says goodbye to his little buddies. Photo by Maj Barry Broman, USMCR (Ret)

CAP Marines were not always lucky enough to work in a pacified and friendly area. A friend, former Corporal Cottrell Fox, served as a CAP Marine not far from Hue City. His unit in CAP Company H, 3d Combined Action Group, came under intense attack by a large and heavily armed NVA unit making their way to Hue, the former imperial capital of Vietnam at the onset of the Tet Offensive of 1968. Fox’s small unit was in deep trouble from minute one. As he wrote in a letter home from a hospital bed in Cam Ranh Bay on 3 February, “Briefly, 400 NVA attacked us at [0400] from all sides—maybe 100 penetrated the compound—mostly sappers. . . . we had to fall back to the center of the compound around the radio bunker. . . . Finally, we called the deadliest anti-personnel artillery of all on ourselves. . . . Plus 50 rounds of 155mm high explosives around the compound itself.”1

The Marines and PFs fought off the NVA while guarding a key bridge. Fox reported, “My rifle was so hot that I had to take off my shirt and hold the fore stock with it. . . . We kept praying for dawn to break—and it seemed to take forever. . . . I found 25 bodies that we had killed. I knew there were beaucoup dead—everywhere you shot you hit them. . . . When dawn broke we had 2 dead Marines and 3 dead PFs.”2

A CAP sergeant briefing Popular Forces before a patrol. Photo by Maj Barry Broman, USMCR (Ret)

Well-armed Popular Forces troops about to conduct a patrol with CAP Marines. Photo by Maj Barry Broman, USMCR (Ret)

The Marine Corps’ summary of the action of Company H on the night of 31 January 1968 as stated in the Silver Star recommendation for Fox, has less emotion. It reads, in part, “A multi company of NVA/VC [Viet Cong] opened the assault with a simultaneous mortar and sapper attack. . . . that quickly penetrated the perimeter and led to the hand to hand, life and death struggle of several hours described in this recommendation of award for Corporal Cottrell Fox and Corporal Charles Brown. . . . More than 40 enemy bodies were found in and around the compound which was badly damaged and subsequently abandoned.”

Years later in 2018, Fox, a retired business executive in St. Louis, Missouri, received the Silver Star Medal for the actions by which he was badly wounded. His buddy, Corporal Charles Brown, received the Navy Cross.

A CAP sergeant talking to Popular Forces before a patrol. Photo by Maj Barry Broman, USMCR (Ret)

A CAP sergeant respectfully talking with village elder. Photo by Maj Barry Broman, USMCR (Ret)

Two little girls in the Popular Forces village. Photo by Maj Barry Broman, USMCR (Ret)

I was interested to learn from Fox that his hard-pressed and hard-hit CAP platoon was saved by the intervention of Company H, 2d battalion, 5th Marines, the unit I served with a year later in Vietnam. The story of Company H in the battle for Hue is told in Stanley Kubrick’s film, Full Metal Jacket. I think the story of CAP Marines also merits a film. As Brigadier General Gary E. Brown put it, remembering his time in CAP service, “If the CAP concept had been implemented and fully supported early in the war, the outcome could have been much more positive than the April 1975 TV debacle.”3

Over the years, I have heard comments from Marines suggesting that CAP Marines assigned to Vietnamese villages in pacified areas had easy duty and faced little real danger. Some even compared CAP duty with being on an in-country R&R. But CAP Marines faced real danger. Units conducted combat patrols daily and ambushes frequently with their PF counterparts to protect their villages. The relaxed, easy-going Marines seen here working with PF Vietnamese militia and Vietnamese civilians could, at a moment’s notice, be involved in a life-and-death situation, as happened to Fox’s unit on the eve of the Tet Offensive in 1968. The record shows that during their CAP service, approximately 500–525 Marines were killed in action.4

•1775•

ENDNOTES

-

Cpl Cottrel Fox, letter home, 3 February 1968, provided to author by Cottrel Fox from his personal papers collection, hereafter Fox letter, 3 February 1968.

-

Fox letter, 3 February 1968.

-

BGen Gary Brown, email to author, 16 August 2021.

-

William F. Nimmo with Henry Beaudin, “The Creation of the Marine Corps’ Combined Action Platoons: A Study in Marine Corps Ingenuity,” Marine Corps History 4, no. 2 (Winter 2018): 43